UM SONHO QUE NASCE NA METRÓPOLE: CONSIDERAÇÕES SOBRE A CIDADE MODERNA EM LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND

Tânia Alexandra Cardoso é Mestra em Urbanismo. Estuda histórias em quadrinhos como uma mais-valia para métodos científicos de investigação, representação e crítica da cidade.

Como citar esse texto: CARDOSO, T.A. Um sonho que nasce na metrópole: considerações sobre a cidade moderna em Little Nemo in Slumberland. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 12, 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 24 Abr. 2024.

Resumo:

A Era moderna, de cariz revolucionário e progressista foi um grande catalisador não só a nível industrial, mas em termos de comunicação e de rotura de paradigmas passados. A representação da cidade foi particularmente intensa neste período: estudos e projetos ambiciosos surgiram enquanto reformuladores de questões associadas aos problemas urbanos da época. É possível verificar que é também neste momento que as Histórias em Quadrinhos ganham importância e destaque na Sociedade e principalmente na Cidade. A representação da cidade ganha uma nova dimensão, passa a ser um elemento de inspiração. Windsor McCay foi um artista à frente do seu tempo. Será também ele um Moderno Radical ao questionar o espírito da época e o desenvolvimento das cidades modernas através das experiências gráficas e reflexões presentes na sua obra Little Nemo in Slumberland?

Palavras-chave:: urbanismo; utopia; metáfora; histórias em quadrinhos; Little Nemo in Slumberland.

INTRODUÇÃO: A EMERGÊNCIA DA CIDADE MODERNA1

A vida moderna derivou de uma Era revolucionária com grandes mudanças econômicas, políticas e sociais no mundo ocidental. O grande catalisador para tal Era foi a Revolução Industrial no século XVIII a qual moldou uma sociedade tipicamente burguesa e capitalista enfatizando a produção industrial e voltada para uma sociedade de massa em detrimento da produção artesanal.

Após a Revolução Industrial, surge um impressionante crescimento demográfico das cidades. A cidade tornou-se o elemento dominante na sua relação com o campo e a população urbana cresceu de forma assustadora e desregulada. De 1820 a 1870, a cidade encontra-se cheia de motores, canais e ferrovias num padrão descentrado e sem limite definido. Até 1920, a metrópole industrial floresce num espírito de reforma que ganha força à medida que as cidades se tornavam mais complexas (WARNER, 1972).

A população imigrante aumentava a olhos vistos em cidades industriais como Chicago ou Nova Iorque. Os sentimentos humanitários, principalmente de médicos e higienistas, denunciam o estado de deterioração física e moral em que vivem os operários. No centro e nos arrabaldes, viviam em habitats insalubres, frequentemente afastados do local de trabalho ou em cortiços amontoados com lixeiras, com uma forte incidência de doença e mortalidade, e sem espaços verdes (CHOAY, 1992 [1965], p .5). A apropriação desenfreada do espaço aumentou a sua insalubridade, o deficit habitacional, a insegurança pública e as infraestruturas precárias. Bairros de lata e slums começaram a multiplicar-se (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 6-7).

Há preocupação com a melhoria das condições sanitárias das cidades, da educação e na criação de uma consciência política e social na população. Era urgente estudar a situação em questão2 e propor um planeamento urbano que ordenasse a estrutura urbana e social da cidade. Os city-planners reformam e desenvolvem cidades e áreas metropolitanas num planeamento em larga escala (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 1-7; SANTOS, 1999; BORGES, 2012, p. 22). Com o desenvolvimento dos meios de transporte e sistemas de comunicação, as distâncias tornaram-se mais curtas e multiplicaram-se as formas de conexão destruindo as barreiras espaciais. As indústrias implantaram-se no subúrbio provocando deslocações pendulares diárias e consequentemente uma explosão urbanística dispersa e fragmentada. A vida acelerou-se e a vida quotidiana foi consequentemente alterada.

Abriram-se grandes avenidas arborizadas, boulevards, praças, parques e jardins públicos transformando áreas por desenvolver em polos de vida urbana. Os teatros, a ópera, os cabarets, os cafés e os cafés-concerto e o vaudeville eram cada vez mais frequentados. Este modus vivendi refletiu-se não só na forma de cada pessoa estar e vivenciar a cidade, mas também na forma como os artistas passam a ver, a sentir e representar a cidade (CHOAY, 1992 [1965], p. 1-5; BORGES, 2012, p. 21).

O homem urbano era diferentes homens. Sua vida era diferentes vidas. […] Os acontecimentos, os fatos, as coisas, multiplicavam-se, ocorriam desordenadamente […] O mundo desse homem é, massificante, no entanto, cada vez mais ele é cônscio da sua individualidade (MOYA, 1972, p. 104).

No século XX, em resposta ao caos da grande cidade, o espaço urbano foi forçado às rédeas da funcionalidade, visto como uma totalidade em torno de uma racionalidade utilitária. Segundo Françoise Choay (1992 [1965]), os vários estudiosos da cidade aperfeiçoaram projeções de cidades futuras como antítese da desordem, mas muitos por não poderem dar uma forma prática ao questionamento da sociedade ficaram na dimensão da utopia.

A cidade de Chicago tornou-se um exemplo. A cidade expandiu-se anexando áreas vizinhas, efetuando grandes obras infraestruturais e prometendo melhores condições na esperança de albergar a grande exposição do quadricentenário da descoberta da América, a World’s Columbian Expositon (1893). No entanto, ao invés de se maravilharem com as indústrias locais em exposição, os visitantes ficaram especialmente encantados com a beleza e esplendor do conjunto edificado da exposição (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 31-33). Segundo Mel Scott (1971 [1969], p. 45) a feira apenas deu forma tangível a um desejo que brotou de uma maior riqueza na cidade, da banalização da viagem e na procura de uma imagem que projetasse o orgulho nacional de um país poderoso.

As sociedades municipais de Arte, inspiradas na exposição de 1893 organizada por Daniel Burnham, começaram a reunir-se para discutir o desenvolvimento artístico das cidades. O ponto principal a considerar nestas reuniões era o plano da cidade como ponto de partida, utilizando como modelo a cidade de Paris “Haussmanniana”. Obras europeias clássicas e renascentistas como o Parthenon ou a Basílica de São Pedro eram as preferidas para edifícios do Estado, engrandecendo a cidade (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 44-60).

O Estado e a lógica de mercado apontavam para uma dominância crescente da sociedade de consumo e com ela um enaltecimento dos meios de comunicação para a difusão das ideologias e políticas. A instrumentalização dos meios técnicos pela máquina estatal e a indústria cultural foram utilizados como um processo feito para atingir a muitos, vistos não como multidão, mas sim como massa (BENJAMIN, 1994).

A cidade despontou em tais meios de comunicação em massa, não somente laureando os grandes centros urbanos como lugar do progresso, ascensão social, oportunidades e grandes avanços tecnológicos, mas também difundindo as propostas urbanas modernas em imagens “espetáculo” da cidade.

SONHANDO COM A CIDADE PERFEITA

É possível considerar que o momento de criação de Urbanismo3, com base nas roturas epistemológicas, na importância da divulgação das ideias e desenvolvimento do ensino, situa-se no mesmo recorte histórico do nascimento das Histórias em Quadrinhos.

Tanto os desenhos de Rodolphe Töpffer4 como o desenvolvimento dos folhetins culminaram na criação de HQs semanais nos jornais americanos na virada do século XIX para o XX. Os grandes jornais procuravam fornecer informação e entreter as massas com tiras cómicas representando, na sua maioria, a vida dos imigrantes e a vida na grande cidade americana.

A vida e o desenvolvimento urbano eram impulsionados pelas impressões e conteúdos dos folhetos e jornais e, nesse sentido, é possível considerar um paralelo. Neste recorte, destaca-se Little Nemo in Slumberland de Winsor McCay.

Começando por desenhar posters de circo em estilo Art Nouveaux, Winsor McCay5 rapidamente extravasou os seus conhecimentos. As suas experiências e roturas com a tradição fazem dele uma das figuras mais importantes da História das Artes Gráficas e da Animação (CANEMAKER, 1987; SENDAK, 1987; MCCAY, 1989). Quiçá pelo seu espírito empreendedor e intrépido, fruto das inovações e do ritmo frenético da época, ou pelas características gráficas do seu trabalho, é um autor pertinente ao tema Modernos Radicais.

Little Nemo in Slumberland começou por ser publicado em 15 de outubro de 1905, no jornal New York Herald, até 1911, quando migrou para o New York American até 1913. Não era uma HQ muito popular quando comparada com outras de carácter mais cómico e satírico, como Krazy Kat, de George Herriman, ou The Yellow Kid, de Richard F. Outcault (DORIGATTI, 2011).

Na história, o pequeno Nemo é abordado por um comissário do Rei Morpheus que quer-lhe mostrar o caminho certo para chegar ao Reino dos Sonhos. McCay não só descreve os sonhos mas cria também mundos incrivelmente ricos em detalhes belos e diversos. A sua sensibilidade para a linha, cor e espaço é uma expansão da sua vida rodeada pelo vaudeville e pelas atrações de Coney Island. Os sonhos de Nemo são preenchidos com palhaços, acrobatas, bailarinos, animais fantásticos ou grotescos, mágicos e salas de espelhos (WINSOR, 1989; SENDAK, 1987).

Utópicas e maravilhosas estas cidades funcionam como um universo alternativo. Os signos visuais existentes em Little Nemo dão informações ao leitor e transportam-no na memória para cidades reais como Nova Iorque ou Chicago.

Para Adriana de Caúla e Silva (2002, p. 18-20), na dissertação de mestrado “Cidades Imaginárias: Utopia, Urbanismo e Quadrinhos”, a obra de Thomas More, A Utopia, aparece como paródia crítica e antagónica à sociedade Inglesa do século XVI e o termo utopia tornou-se característico de todo um conjunto de projetos e civilizações ideais, fantásticas e imaginárias. Segundo Quiring (2010, p. 201, tradução nossa6) a “[...] cidade imaginária da memória não é mais que uma metáfora enorme na qual informação complexa é conjugada, condensada e alegoricamente estruturada […]” na qual a passagem do tempo é espacial e onde o espaço é carregado de fluxos de experiências e significados provindos da memória da experiência real.

LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND, DE WINSOR MCCAY

Em 1893 ergue-se em Chicago a promessa de uma White City, “um sonho que nasce sobre os pântanos” (SMOLDEREN, 2010, p. 26): o movimento City Beautiful. Impulsionado pelos planos de Daniel Burnham e pelas sociedades municipais de arte, pretendia criar uma cidade funcional e humana, mas principalmente restaurar a sua beleza (HINES, 2000). Tais ideais marcaram fortemente a imaginação de Winsor McCay.

Little Nemo in Slumberland é ainda hoje uma das mais influentes HQs em todo o mundo. McCay foi um homem voltado para o espetáculo e, em conjunto com a melhor equipa de tipógrafos do New York Herald, reuniu as condições ideais para criar Little Nemo. A sua imaginação onírica repousa na figura de um rapazinho que entretém o leitor ao passear por mundos audaciosos e de arquiteturas grandiosas procurando por uma princesa.

A linguagem, segundo Foucault (2002), não é a representação do real, mas identifica-se com ele. É semelhante e diferente no mesmo espaço, mas não é a sua cópia. Esta representação funciona como uma espécie de ponte entre o real e a mimese, não sendo nem uma coisa, nem a outra. Nas representações de Little Nemo in Slumberland, os sonhos misturam-se muitas vezes com a realidade, o menino não parece ter noção de que os seus sonhos não são reais, mas uma outra dimensão, que representa a visão metamorfoseada7 de McCay acerca da realidade.

Estas representações exploram a reorganização e a justaposição dos elementos arquitetônicos criando novos espaços, com uma imagem fantástica, de forte carácter e grandeza (FRANCO, 2012, p. 8). Podem quase ser comparados aos desenhos das ruínas romanas de Giovanni Battista Piranesi apresentadas de forma onírica, às quais chamou Carceri, que resultaram em um conjunto de “imagens mágicas e ilusórias” (CAÚLA E SILVA, 2002, p. 18). A aproximação da criação imaginária em relação à cidade experimentada pelos autores, no caso de Piranesi a cidade de Roma e, de McCay, a cidade Chicago/Nova Iorque, situa-os numa posição de utopia gráfica, pela posição crítica dos autores face às cidades reais através da criação das suas facetas imaginárias.

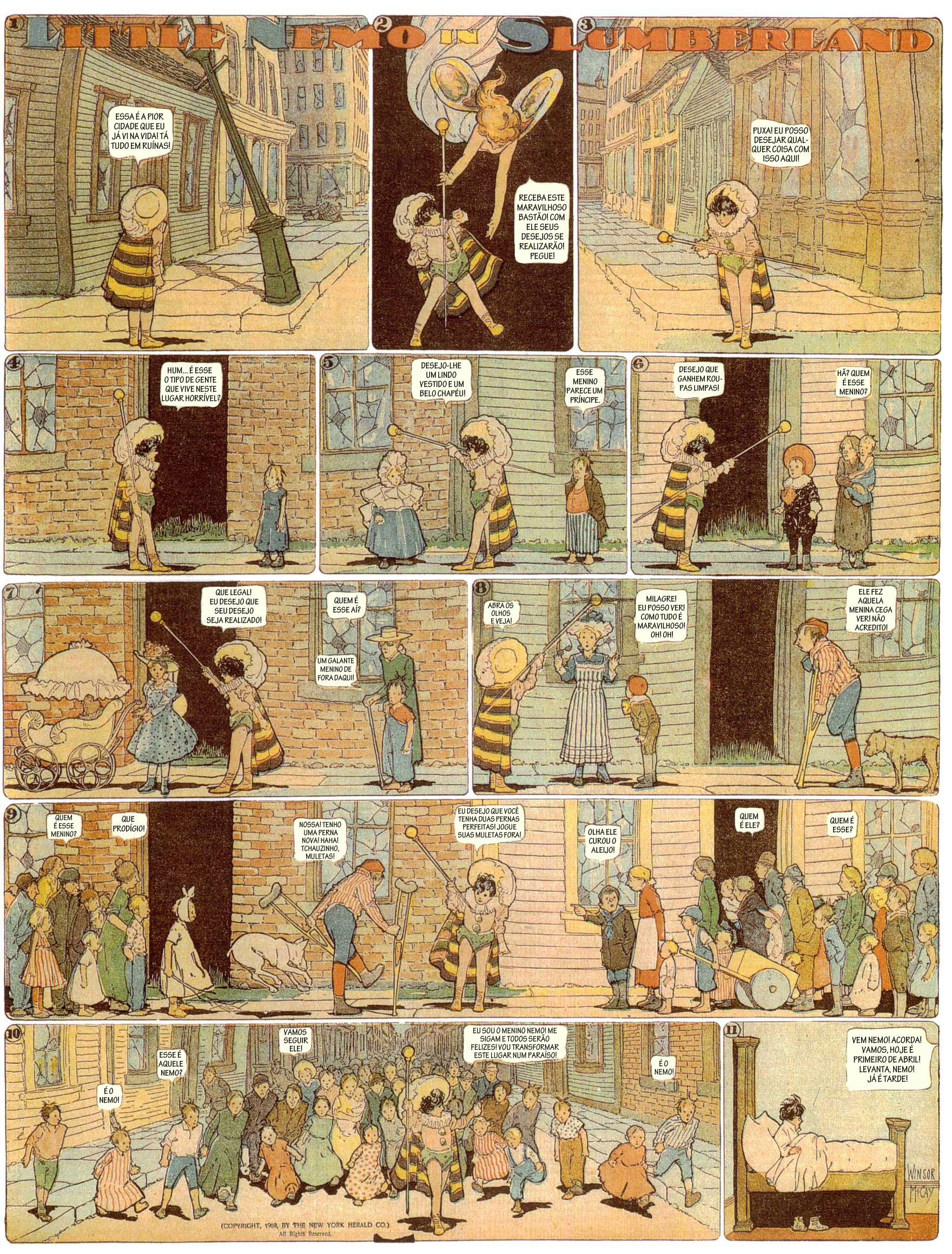

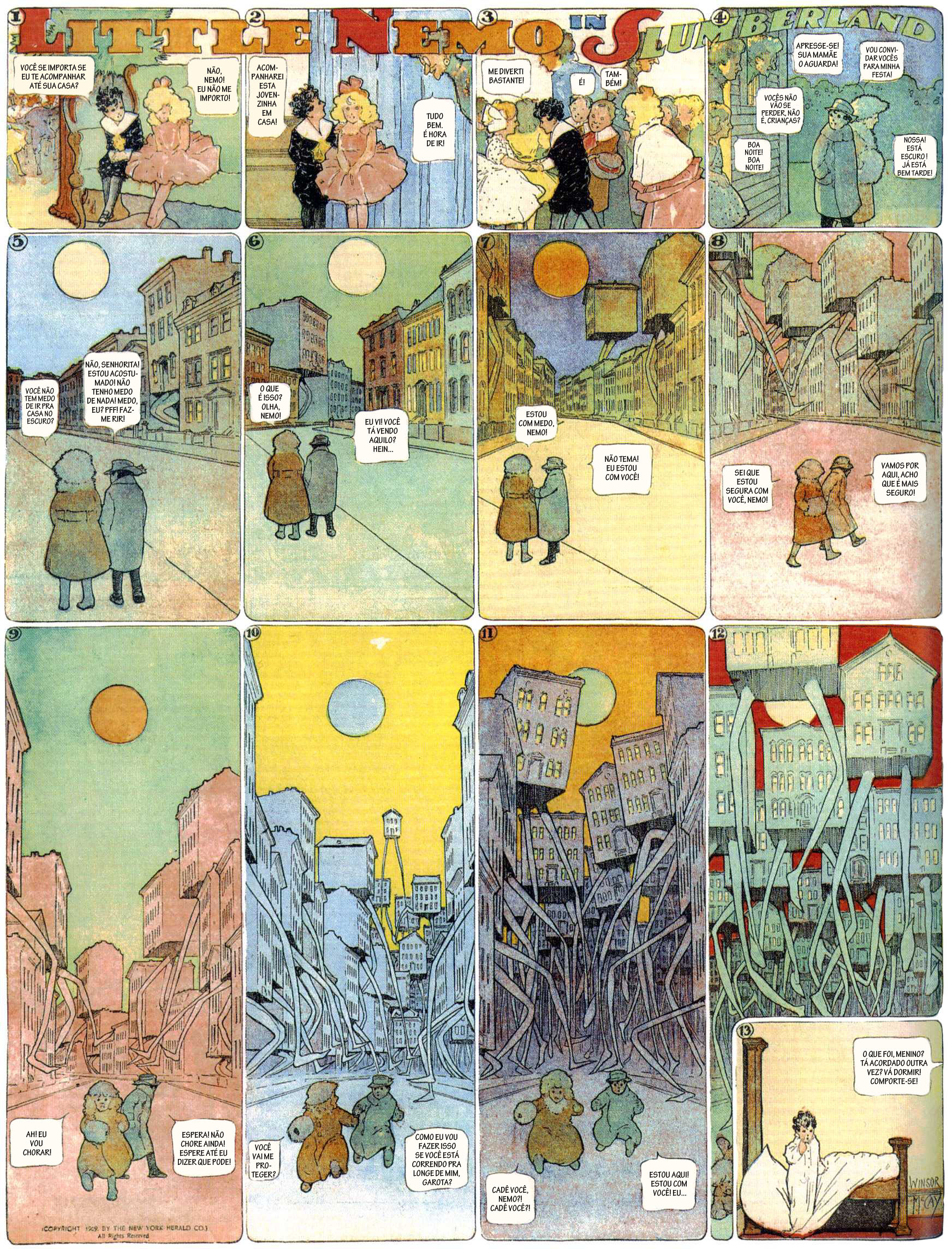

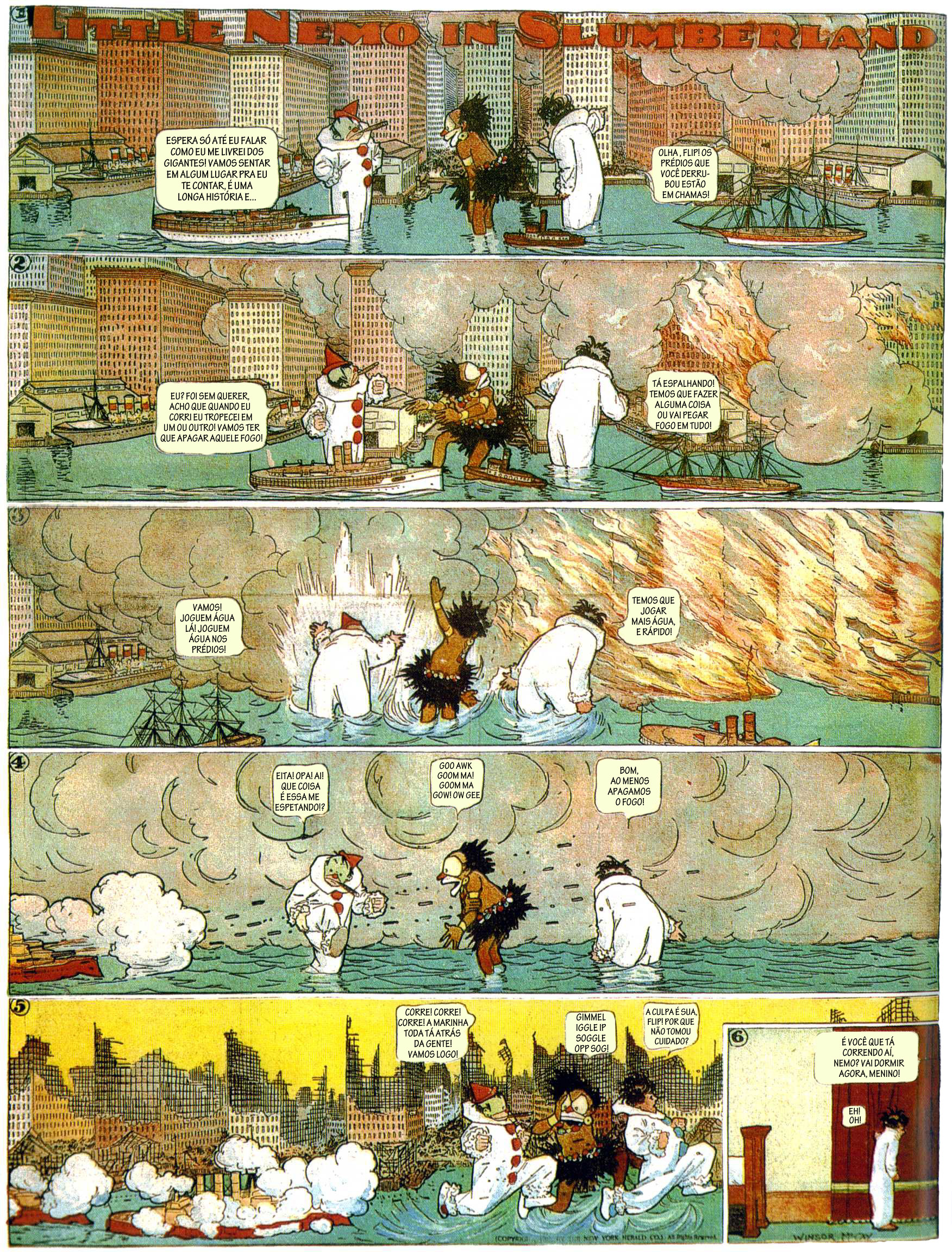

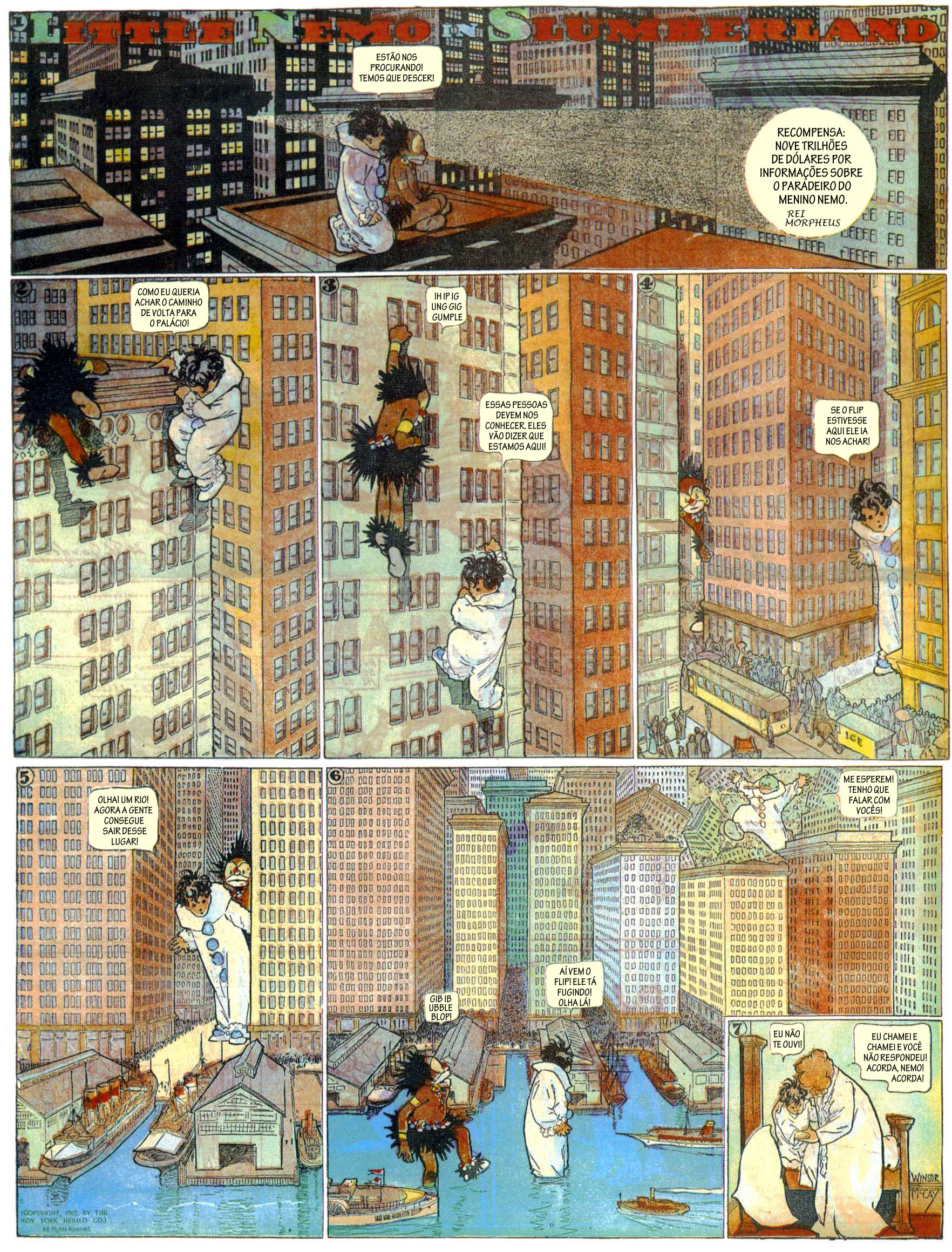

Nas pranchas publicadas nos dias 29 de março e 5 de abril de 1908, Nemo chega a uma cidade devastada e recebe um bastão de desejos para resolver o problema dos pobres e oprimidos, de acordo com o espírito higienista da época.

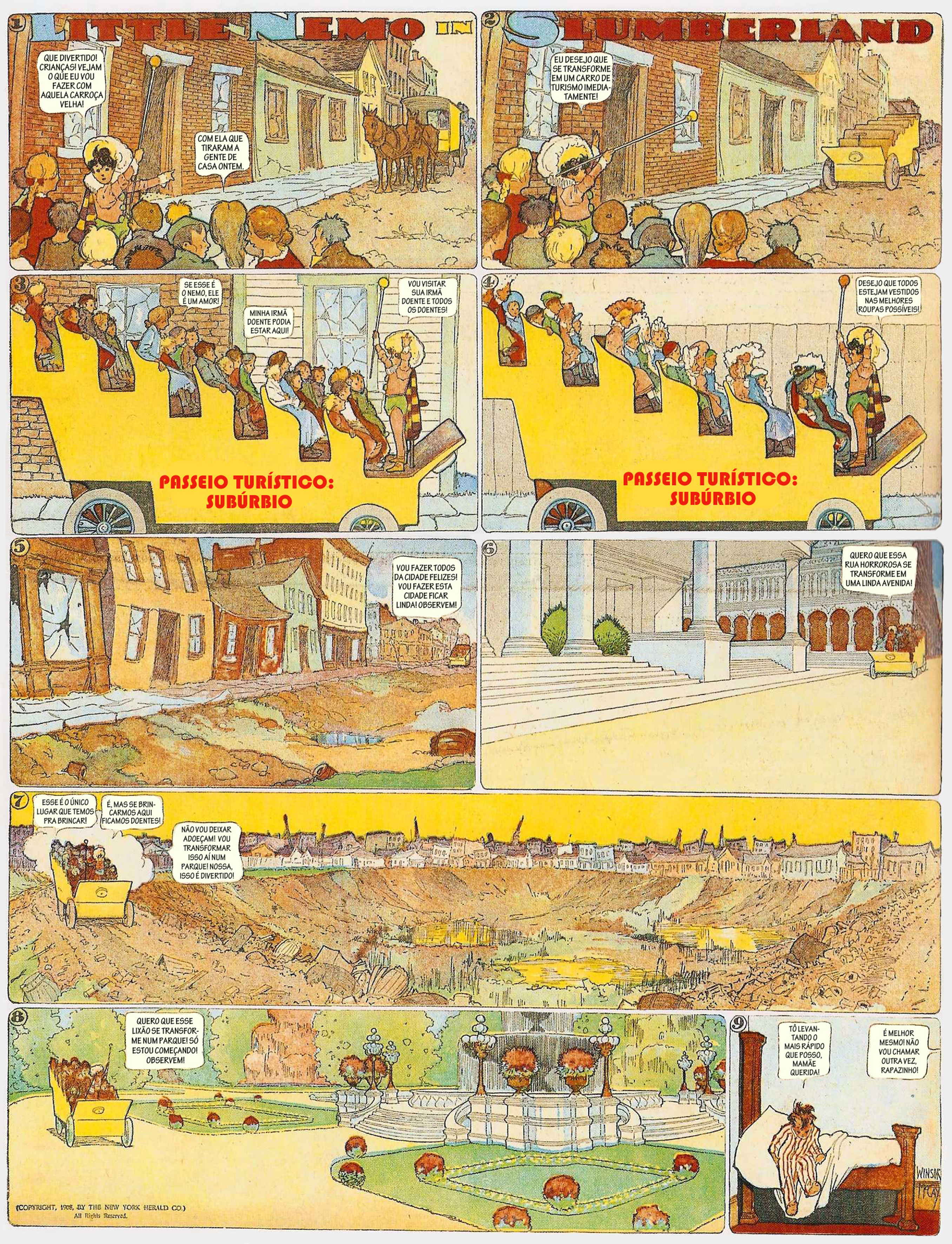

De forma mágica, Nemo começa a mudar os subúrbios dos bairros dos sonhos, lugares feios, pobres, sujos e deprimentes. As ruas são representadas como construções sem harmonia, os edifícios são todos diferentes e dispostos de forma desordenada. Com um acenar do bastão mágico, o menino cria luxuosas e largas avenidas em estilo Neoclássico, remanescentes dos pavilhões da exposição de 1893, e também grandes espaços abertos com jardins verdejantes “combatendo” os lugares doentes da cidade.

O autor adota a posição da City Beautiful ao deixar transparecer a sua predileção pela ordem cívica e pela beleza, em um racionalismo crítico que vislumbra a perfeição renegando para segundo plano as questões sociais, económicas e de mobilidade (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 76-78). É possível comparar com a obra de Richard F. Outcault, Yellow Kid, onde o autor mostrava o estado miserável em que viviam os imigrantes na passagem do século XIX para o XX descrevendo de forma muito verosímil o estado de segregação social nas cidades (os guetos e bairros de lata) no centro das grandes cidades. Apesar de terem abordagens muito diferentes ambos autores pretendiam através do humor abordar temas e questões sociais importantes.

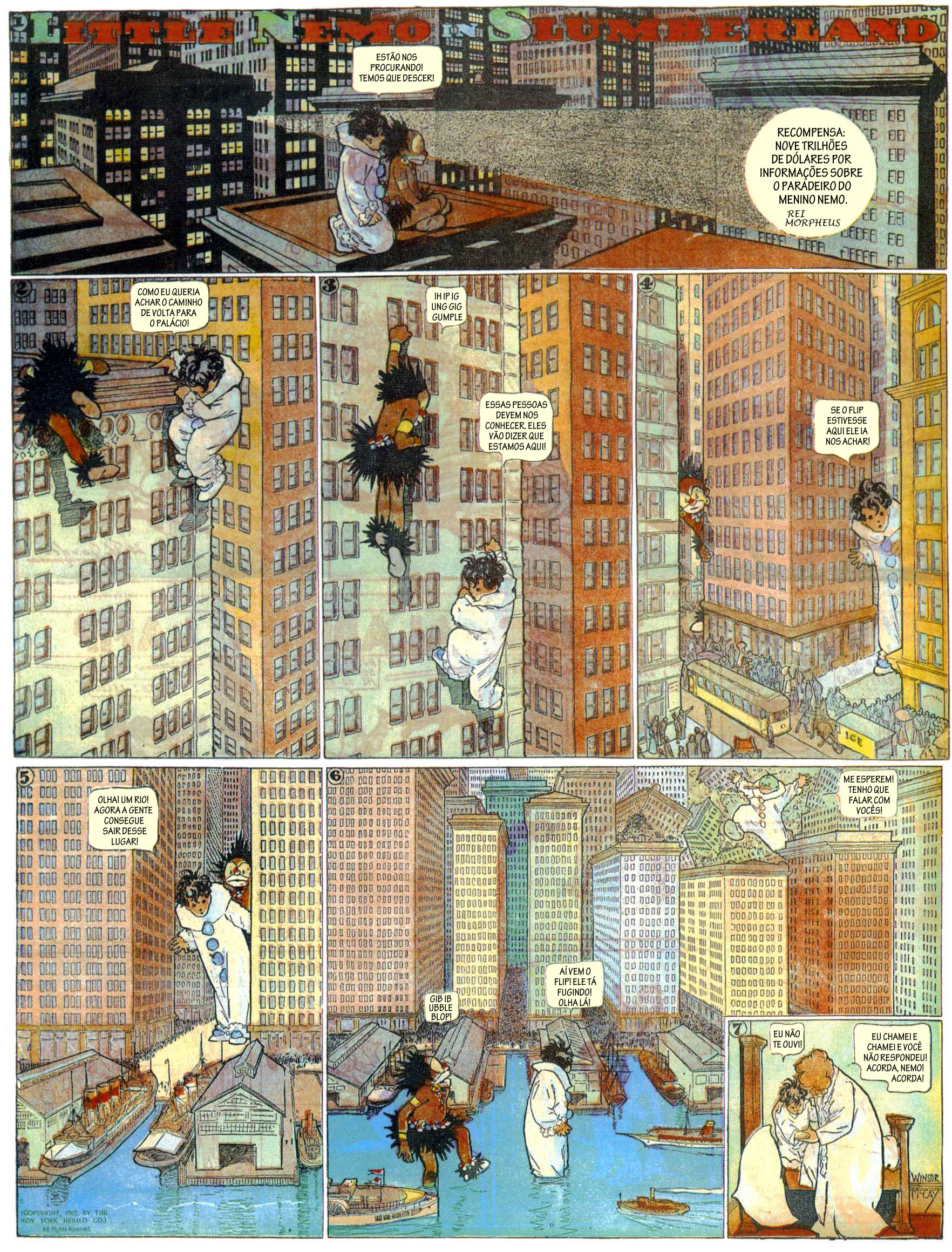

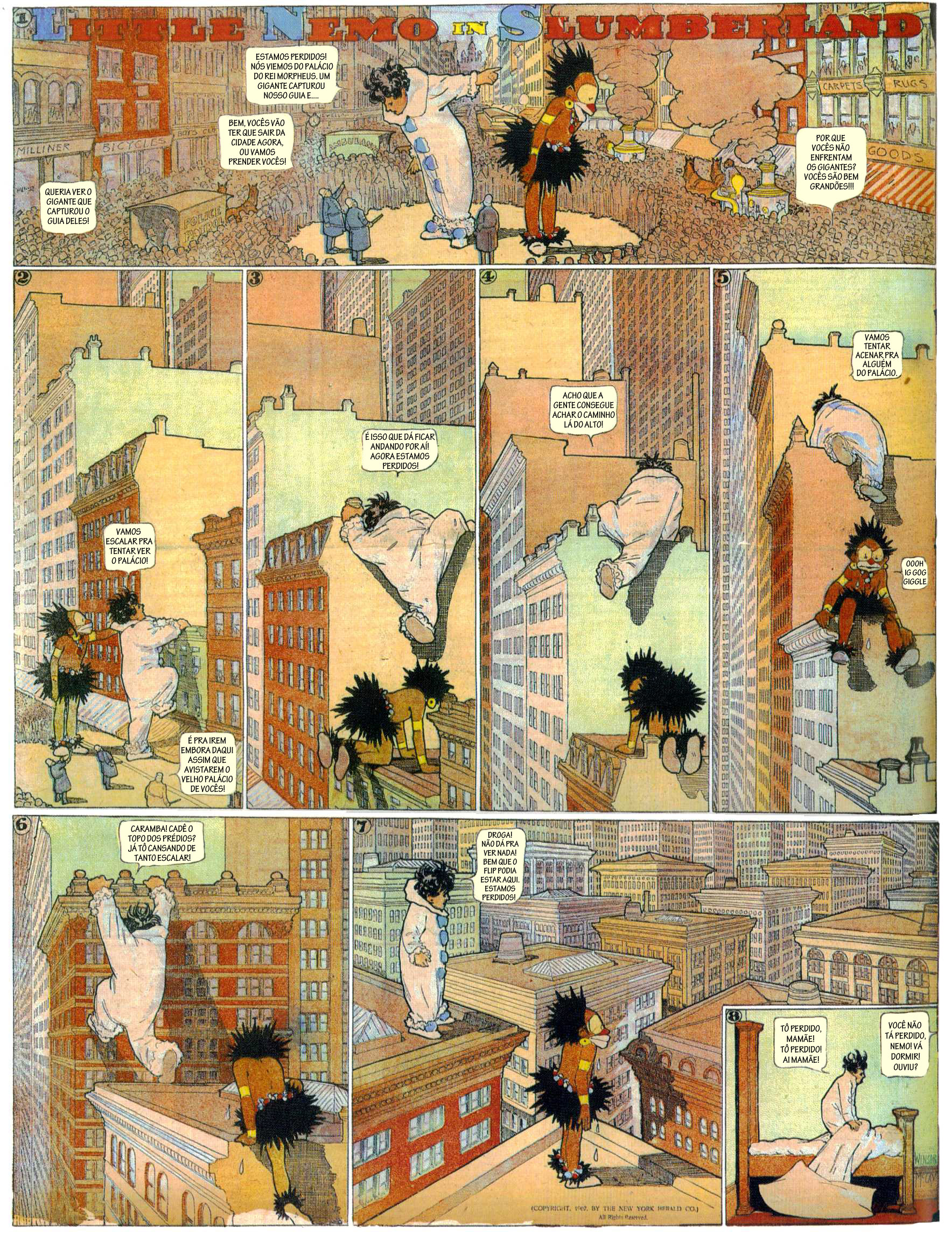

Na prancha publicada no dia 21 de março de 1909 é visível o aspecto desorientador e assustador que McCay pretende passar ao representar velhos bairros da cidade. Ao contrário da cidade do rei Morpheus, do mundo dos sonhos, esta cidade muda, cresce rapidamente e move-se tornando o ambiente ameaçador e claustrofóbico em uma metáfora à necessidade de espaço devido ao rápido crescimento e transformação incontroláveis das cidades (WARNER, 1972).

Fig. 1: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; tira publicada originalmente no dia 29 de março de 1908 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 2: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 5 de abril de 1908 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 3: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 21 de março de 1909 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

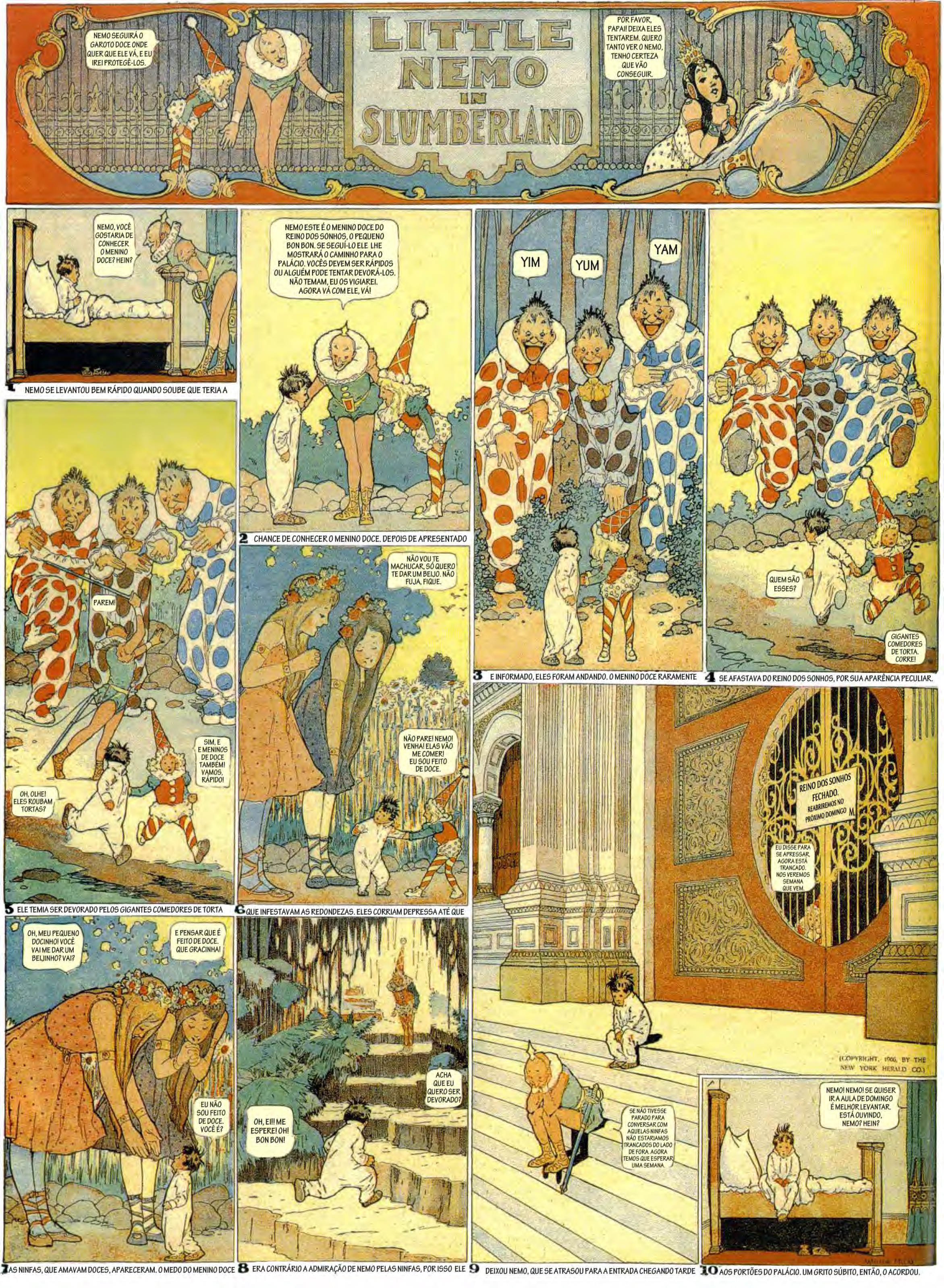

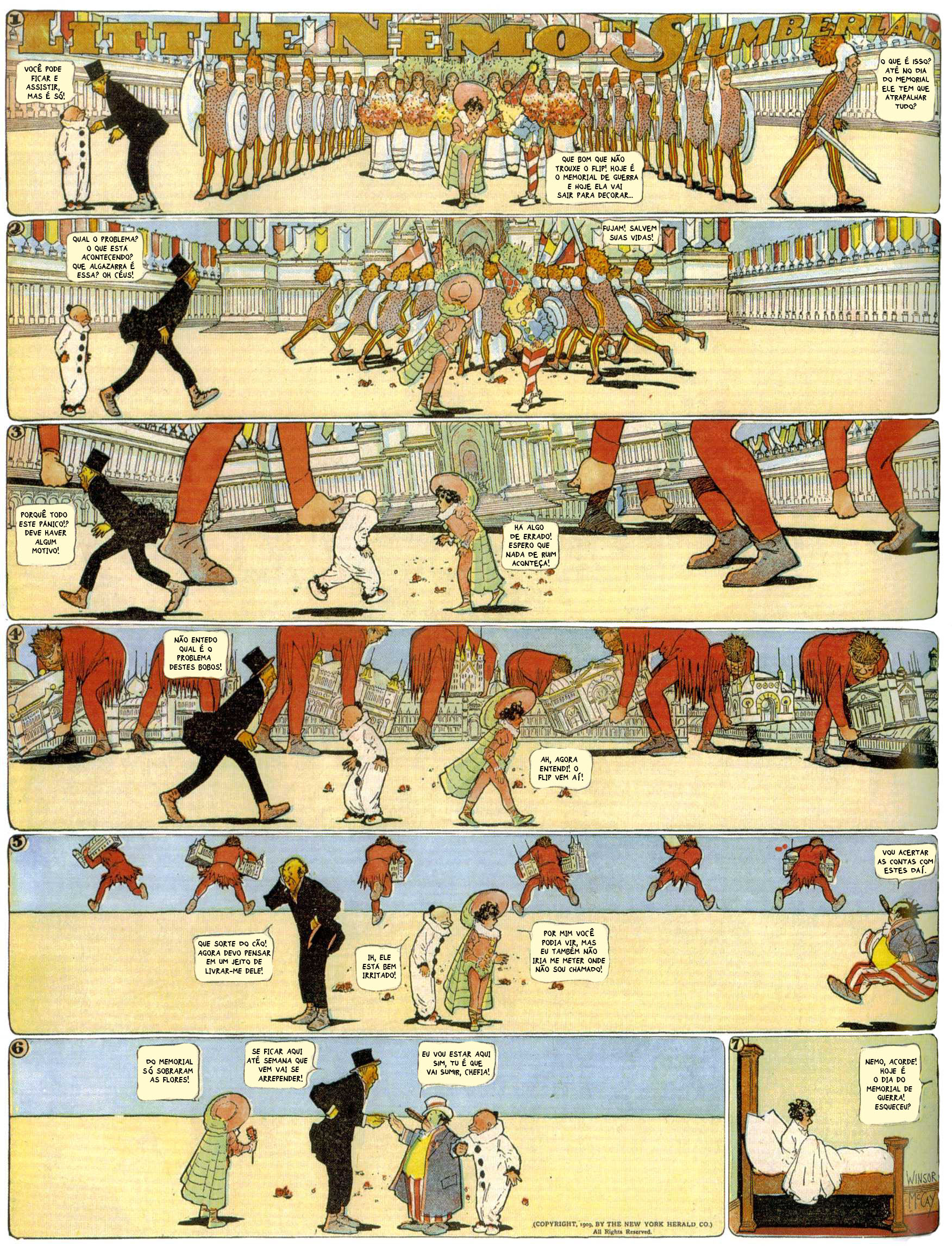

Em 25 de Fevereiro de 1906, Nemo chega ao Palácio Slumberland com os seus arcos concêntricos e rendilhados em folha d’Ouro. O pórtico que o leva à capital dos sonhos assemelha-se à porta de ouro do Palácio dos Transportes da exposição de 1893, em Chicago, construído por Louis Sullivan8. Também Coney Island, com as suas atrações e diversões, é uma referência sugerindo mundos de divertimento nobre equilibrando forças entre as diversões desenfreadas das feiras e os valores de beleza, unidade e de ordem. McCay usa a perspectiva linear de forma prodigiosa e ousada criando visões particularmente detalhadas especialmente na representação da arquitetura e paisagens urbanas.

Fig. 4: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 25 de fevereiro de 1906 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

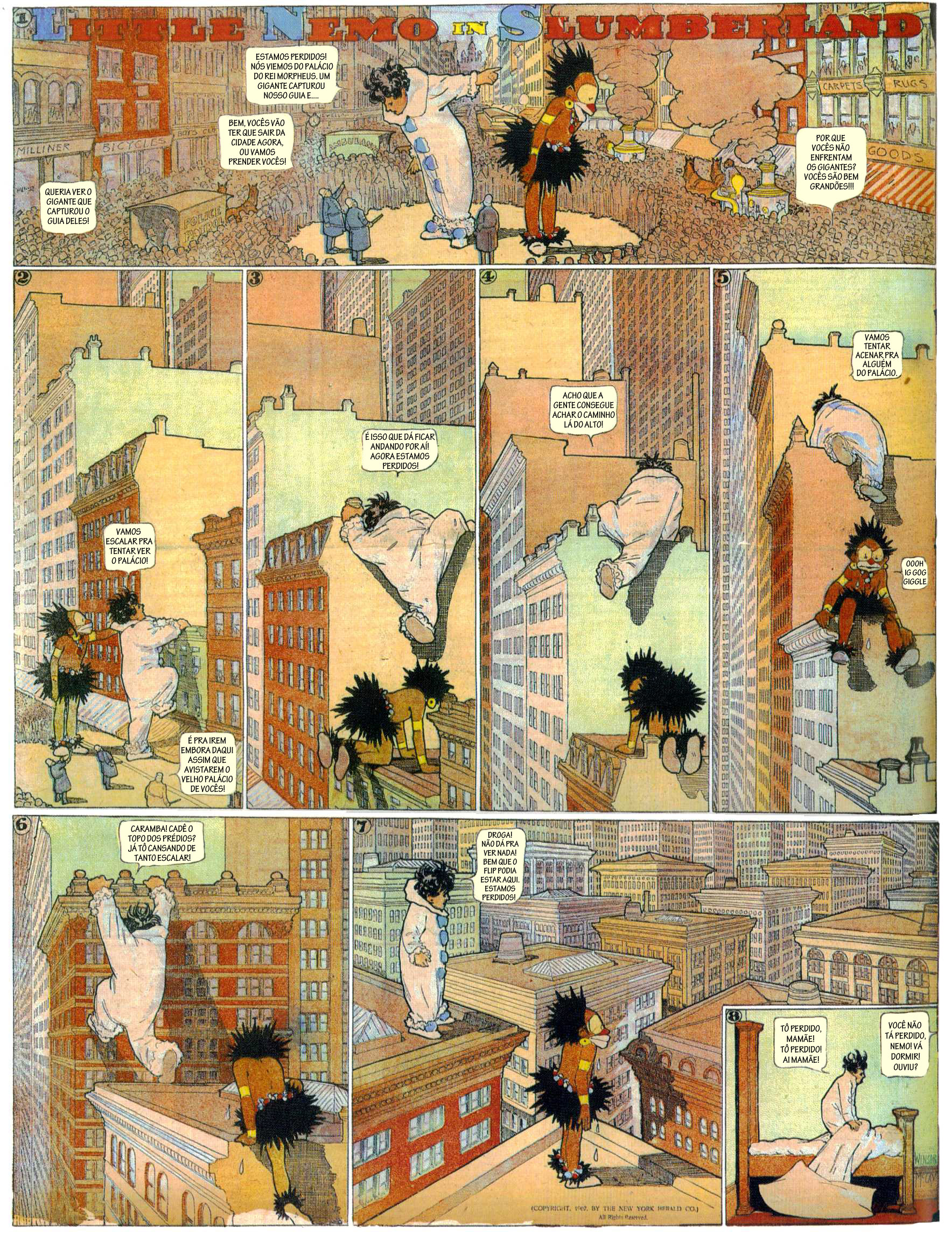

Porém Little Nemo não reflete apenas o caráter onírico da cidade. Em algumas das suas páginas McCay mostra também o conflito existente entre a vista panótica e o caminhar pela cidade. Nas pranchas de setembro de 1907, Little Nemo, gigante no meio de uma cidade de edifícios altos remanescente de Nova Iorque. O menino sente-se perdido e tenta subir a um ponto mais alto de forma a encontrar a vista total ou panótica da cidade. No entanto, o seu olhar é limitado pelos edifícios de fachadas cegas e de janelas opacas levando Nemo a dizer que não vê nada, mesmo estando a olhar para vários edifícios.

A criação de avenidas de comunicação direta e de uma vista desimpedida eram intensões claras do City Beautiful. Há uma intenção de controlo desproporcionado sobre a cidade e sobre as vidas dos seus residentes (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 48; WARNER, 1972, p. 2). Para Frahm (2010, p. 40, tradução nossa9) “[…] Little Nemo sonha uma cidade que é legível pelo olhar panótico, uma cidade onde é necessário caminhar […]”. Ao não conseguir encontrar essa vista totalizante, Nemo vê-se completamente perdido e “os seus sonhos expressam o medo da cidade” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 40, tradução nossa10).

Fig. 5: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 15 de setembro de 1907 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 6: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 22 de setembro de 1907 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 7: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 29 de setembro de 1907 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 8: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 6 de outubro de 1907 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

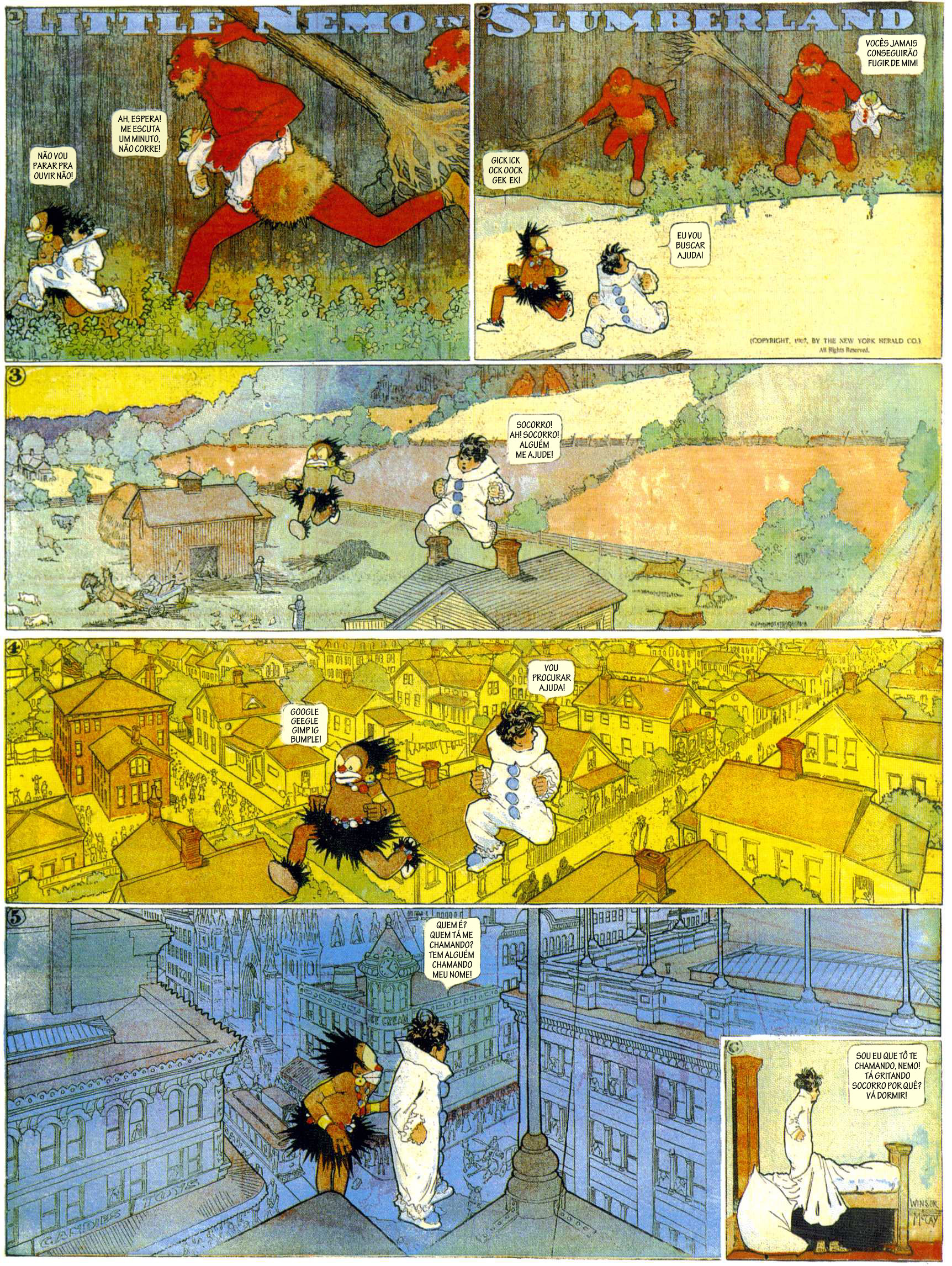

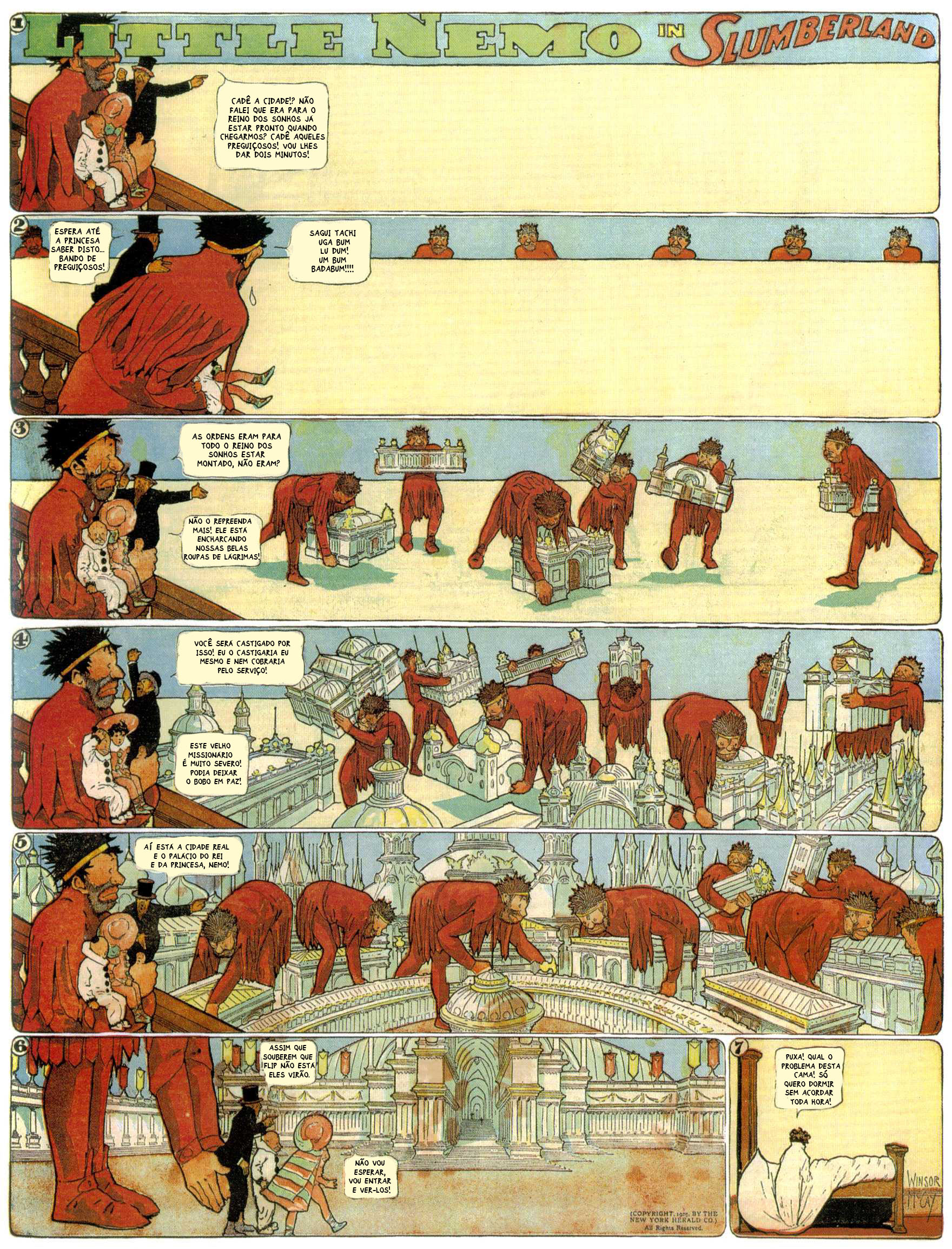

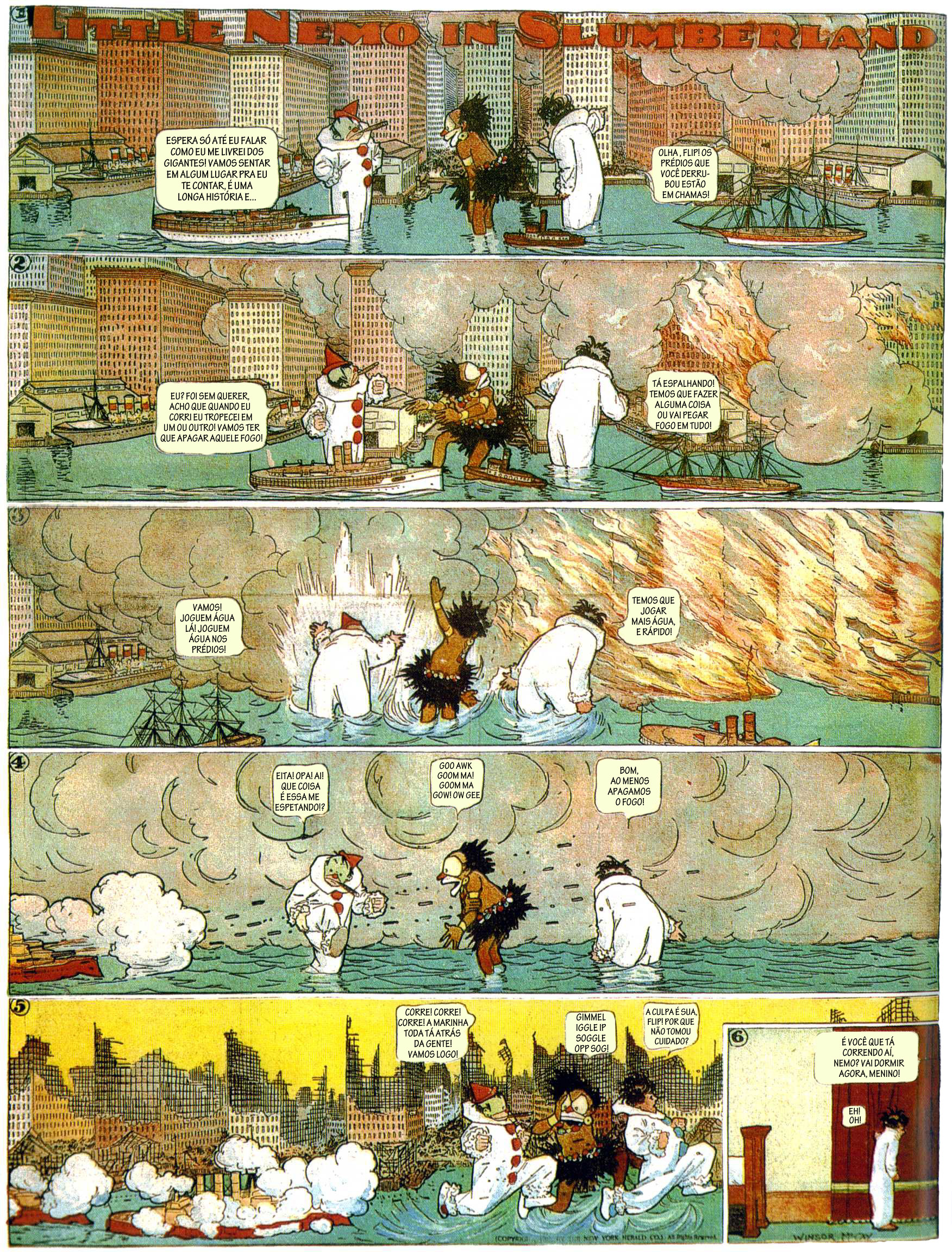

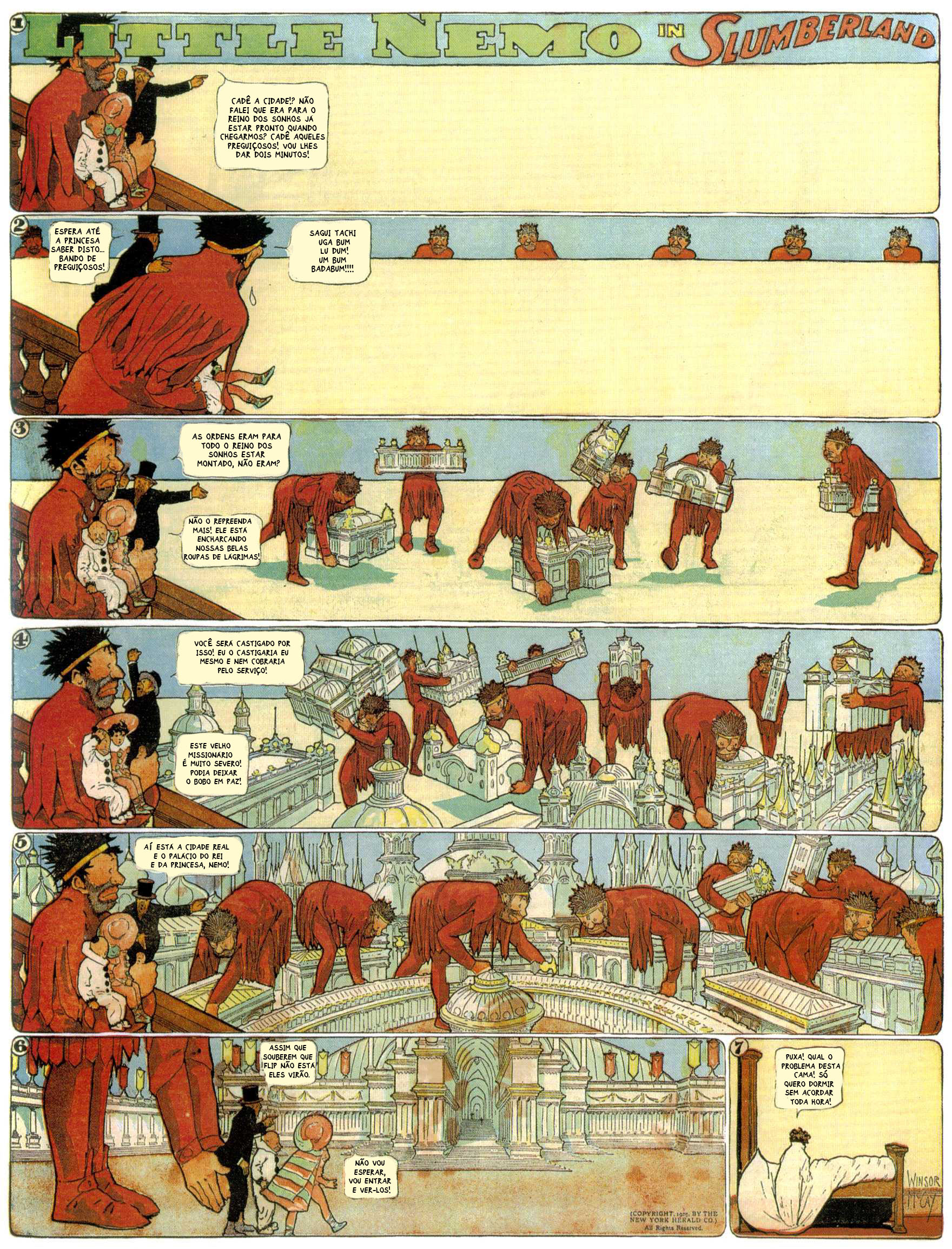

O fluxo da história é dado pelos balões de diálogo que guiam o leitor porque a representação da cidade, que cresceu de forma descontrolada, está marcada por um sentimento de claustrofobia e de labirinto causando medo e alienação no personagem: “a cidade é demasiado grande” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 41). Nos episódios de maio de 1909, um lacaio do reino de Morpheus pretende construir o país Slumberland em um terreno vago. Ele comanda um exército de Bobos que montam e desmontam a cidade dos sonhos a seu bel-prazer e pode até fazer a cidade brotar do chão.

Fig. 9: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 23 de maio de 1909 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 10: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 30 de maio de 1909 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 11: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 6 de junho de 1909 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Parece ser uma resposta a uma sequência anterior que mostra a erosão do estilo Art Nouveau em rabiscos infantis por um sabotador. Qual a diferença entre a imaginação do personagem Flip, uma criança pertencente ao Povo do Amanhecer, com seus rabiscos, e do mágico que, como um city-planner, planeia e resolve todos os problemas da cidade comandando um exército de gigantes capazes de instalar em um piscar de olhos a Cidade Branca. A cidade deixa de ser um simples cenário e torna-se a promessa de um mundo novo: um símbolo do sonho americano (THÉVÈNET; RAMBERT, 2010, p.2 4; SMOLDEREN, 2010, p. 29).

McCay criou as imagens mais surreais como cidades nas quais às casas crescem pernas e que vão caminhando ao longo da rua, cidades que encolhem e nas quais Nemo se torna um gigante, jardins repletos de cogumelos gigantes, animais falantes e outras situações oníricas (DORIGATTI, 2011). O autor utiliza a linguagem própria da HQ para intensificar estas imagens surreais e as ações na narrativa.

Na prancha de 22 de Outubro de 1905, em que Nemo caminha por uma floresta de cogumelos gigantes, a altura dos quadros vai aumentando até ao momento em que o menino derruba um, tido como o momento do clímax da narrativa. A partir daí a altura dos quadros começa a diminuir à medida que a floresta desaba passando uma sensação de claustrofobia e agonia; o mesmo estilo gráfico repete-se noutras pranchas, como a de 26 de Julho de 1908, na qual a sua cama ganha pernas cada vez maiores e, à medida que a narrativa se desenrola, o grafismo acompanha esse crescimento.

Fig. 12: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 22 de outubro de 1905 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 13: Little Nemo in Slumberland, criado por Winsor McCay; Tira publicada originalmente no dia 26 de julho de 1908 no New York Herald. Créditos: Domínio público. Trad. Muraktama Lemos e Yuri Riccaldone.

Winsor McCay foi um pioneiro ao experimentar com os elementos formais da página das HQs, através do arranjo criativo e do dimensionamento dos quadros por forma a aumentar o impacto da história e a expectativa ao longo da narrativa. Há uma conexão direta entre a utilização da linguagem própria das HQs com a mensagem a ser transmitida ao público, numa tentativa de metalinguagem. A sua abordagem inovadora à concepção e layout da prancha mostrou o potencial das HQs ao experimentar com a escala, transformação, perspectiva e com a transmissão do seu ponto de vista (GRAVETT, 2006).

CONCLUSÃO

As grandes transformações urbanas nas cidades modernas na passagem do século XIX para o século XX foram particularmente inspiradoras para os autores das mais variadas áreas. Há uma constante procura pela cidade ideal, longe dos problemas e das graves questões das cidades modernas como a superpopulação, a pobreza, o crescimento informal, a confusão, a sujeira ou o barulho.

Em Little Nemo, é notório o desejo e a necessidade de controlo sobre o seu crescimento na representação da cidade. O autor procura representar principalmente o medo da complexidade e da falta de controlo do ritmo urbano. “O desejo de controlar é maior que o desejo de se perder11” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 40) e neste sentido o olhar panótico é aquilo que limpa a cidade de todas as suas contradições tornando-a um elemento intemporal e controlável (FRAHM, 2010, p. 43).

[…] nos sonhos de Little Nemo, este olhar [disperso] não ganha controlo sobre a cidade. O mesmo é verdade em relação à página de HQ. O olhar é forçado a mover-se e desenvolve a sua própria retórica ambivalente entre controlo e perda dele. Esta é a luta entre poderes na cidade moderna que as HQs revelam (FRAHM, 2010, p. 44, grifo nosso, tradução nossa12).

McCay procura a beleza, o controle e a harmonia nas suas cidades e os seus personagens refletem os pensamentos autocratas dos planeadores da época. O autor acreditava em um ideal de cidade baseado no movimento City Beautiful e pretendia transmitir através das viagens de Nemo a maravilhosa imaginação da época refletindo esse espírito na representação das cidades oníricas, da terra dos sonhos. Ao mesmo tempo e através da utilização de signos visuais, da forma dos edifícios e da sua escala em relação ao menino, queria mostrar o cenário terrível que é perder-se na confusão citadina das cidades não ordenadas e não harmoniosas.

Para Josep-Maria Montaner (1999, p. 148) o componente essencial de qualquer ficção é o fator tempo considerando que o “autor toma como premissa critica certos fenômenos da sociedade contemporânea […] e extrapola essa situação até uma data concreta […]” onde a cidade e a sociedade são descritas partindo destas premissas, representando-as de forma muito verosímil. Para o autor, as arquiteturas desenhadas são vínculos comuns entre as várias ficções utópicas, sejam literárias, cinematográficas ou em HQ, baseando-se na “faculdade de representar através do desenho uma realidade espacial e narrativa” (MONTANER, 1999, p.152).

Os artistas utilizam a HQ como um elemento de entretenimento no qual podem representar e criticar de forma ativa a vida urbana ou as questões citadinas relacionadas com o crescimento da metrópole, procurando transmitir uma mensagem através de metáforas e comparações com as cidades profetizadas nos textos e nos projetos dos vários artistas, arquitetos e estudiosos desta época.

A obra de McCay não poderia ter sido criada separadamente dos tempos vibrantes da viragem do século XIX para o XX. O seu trabalho alude à crescente introspeção e consciência cívica da época refletindo as questões, as transformações citadinas e o seu próprio comentário. A intrusão da realidade no mundo dos sonhos de Little Nemo mostra que McCay é verdadeiramente um moderno radical ao estimular a experimentação no meio gráfico e ao promover uma reflexão crítica através dessa linguagem (CANEMAKER, 1987, p. 259; O’SULLIVAN, 1990, p. 38).

Little Nemo foi a grande criação de McCay e revolucionou toda uma indústria não só pela qualidade gráfica e experimentação visual mas também pelo comentário social que não era típico nas HQs da época. Ainda hoje, artistas como Moebius, Peeters & Schuiten na sua série de HQs, as "Cidades Obscuras", Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Jean Philippe Bramanti; arquitetos como Archigram e os Superstudio, nos anos 1960, e, mais recentemente, Jimenez Lai, Rem Koolhaas ou Jean Nouvel, formulam questões pertinentes relacionadas com o presente e com o futuro através de metáforas baseadas em premissas e projetos das cidades modernas, numa mistura de questionamento e admiração.

Através do olhar crítico do autor e da sua interpretação da realidade é possível criar novos mundos fantásticos. Esta realidade é metamorfoseada e expandida por via da manipulação da linguagem gráfica da HQ e da sua capacidade narrativa. Desta forma constrói significados reais de locais imaginários que são posteriormente decodificados pelo leitor.

É notório o potencial da HQ como modo de representação da cidade e dos seus significados capaz de propor um olhar crítico em relação aos modos e ideais da vida moderna. A City Beautiful teve a capacidade de mostrar cidades “de um passado que a América nunca conheceu” (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 108) e através da HQ essas cidades eram plenamente vividas e experimentadas pelos leitores.

REFERÊNCIAS

BENJAMIN, W. A obra de arte na era de sua reprodutibilidade técnica. In: BENJAMIN, W. Obras escolhidas, vol. I: Magia e técnica, arte e política: ensaios sobre a literatura e história da cultura. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994.

BORGES, M. Comunicando a cidade em quadradinhos: do narrar ao fabular nos romances gráficos de Will Eisner. 2012. 217 p.Tese (Doutorado em Comunicação) - Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Semiótica, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2012.

CANEMAKER, J. Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. Nova Iorque: Abbeville, 1987.

CAÚLA E SILVA, A. Cidades Imaginárias: Utopia, urbanismo e quadrinhos. 2002. Dissertação (Mestrado em Urbanismo) - Programa de Pós-graduação em Urbanismo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2002.

CHOAY, F. O Urbanismo. 3. ed. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 1992. 1a ed. em 1965.

DA SILVA, R. Da Cidade ao Urbanismo: Do Urbanismo à Cidade. Penélope: Fazer e desfazer a História, Lisboa, n. 7, p. 71-81, 1992. Disponível em: <http://www.penelope.ics.ul.pt/indices/penelope_07/07_08_RSilva.pdf> Acesso em: 16 nov. 2013.

DORIGATTI, B. Little Nemo em português, 2011. Blog. Disponível em: <http://www.riocomicon.com.br/little-nemo-em-portugues/> Acesso em: 24 jan. 2014.

ECO, U. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1984.

FRAHM, O. Every window tells a story: remarks on the urbanity of early comic strips. In: AHRENS, J.; METELING, A. (Eds.). Comics and the city. Londres: The Continuum International, 2010. p. 32-44.

FRANCO, E. História em Quadrinhos e Arquitetura. 2. ed. João Pessoa: Marca de Fantasia, 2012.

FOUCAULT, M., As palavras e as coisas, trad. S. T. Muchail, São Paulo: Martins fontes, 2002.

GRAVETT, P. Winsor McCay. 2006. Disponível em: <http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/winsor_mccay1> Acesso em: 17 maio. 2016.

HINES, T. S. Architecture: The city beautiful movement. In: GROSSMAN, J.; KEATING, A. D.; REIFF, J. (Eds.). The encyclopedia of Chicago. Londres: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

MONTANER, J.-M. Ciudades imaginárias: utopias e distopias en el cinema y en los cómics. In: FUÃO, F. (Ed.). Arquiteturas Fantásticas. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 1999. p. 147-163.

MOYA, Á. DE. SHAZAM! 2. ed. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 1972.

O’SULLIVAN, J. The Great American Comic Strip: One Hundred Years of Cartoon Art. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1990.

QUIRING, B. A fiction that we must inhabit: Sense production in urban spaces according to Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell. In: AHRENS, J.; METELING, A. (Eds.). Comics and the city. Londres: The Continuum International, 2010. p. 199-213.

SANTOS, M. A natureza do espaço: espaço e tempo, razão e emoção. 3. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1999.

SCOTT, M. American City Planning Since 1890. Berkeley; Los Angeles; Londres: University of California Press, 1971. 1a ed. em 1969.

SENDAK, M. Foreword. In: CANEMAKER, J. Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. Nova Iorque: Abbeville, 1987.

SMOLDEREN, T. Winsor McCay et ses héritiers. In: THÉVENET, J.; RAMBERT, F. (Eds.). Archi&BD: La ville dessinée. Paris: Monografik éditions, 2010. p. 26-35.

SØRENSEN, B. The concept of metaphor according to the philosophers C. S. Peirce and U. Eco: a tentative comparison. Signs, v. 5, p. 29, 2011.

THÉVENET, J.; RAMBERT, F. Archi&BD: La ville dessinée. Paris: monografik éditions, 2010.

WARNER JR., S. B. The Urban Wilderness: A History of the American City. Nova Iorque: Harper & Row, 1972.

1 O presente artigo tem por base a pesquisa de Mestrado em Urbanismo “Crónicas Urbanas: Representação e crítica da cidade através de Histórias em Quadrinhos”, de Tânia A. Cardoso, pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Urbanismo da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

2 Estudiosos da Escola de Sociologia de Chicago, como Robert E. Park, foram fundamentais para descobrir quem, porquê e como se vivia nestes locais. Ao mesmo tempo empreendedores caridosos como William Kent ou Jane Adams procuravam, através dos seus projetos, dar melhores condições à classe mais pobre e consequentemente às cidades (SCOTT, 1971 [1969], p. 10-11)

3 Apareceu pela primeira vez na Teoria general de la urbanización de Ildefonso Cerdá (1816-1876) em 1867 designando “’uma matéria nova, intacta e virgem’ que iria ter o estatuto de ‘uma verdadeira Ciência’” (DA SILVA, 1992, p. 71).

4 Töpffer (1799-1846) é considerado o pai das HQs. Foi dos primeiros autores a utilizar a arte sequencial de forma a contar uma narrativa misturado imagem e texto.

5 Nascido em 1867 McCay era artista gráfico, cartoonista político, pequeno editor, artista de Vaudeville e animador. Foi fortemente influenciado por Grandville, Frost e principalmente pela Art Nouveaux de Mucha (SENDAK, 1987).

6 Do original em inglês: It is easily noticed that this imaginary city of memory is nothing but an enormous metaphor by which complex information is drawn together, condensed, and allegorically structured (QUIRING, 2010, p. 201).

7 De acordo com os estudos de Charles S. Pierce (1839-1914) e Umberto Eco (1936-2016) a metáfora realça o processo de representação, invenção e interpretação; desempenha também um papel importante na geração de sentido e conhecimento (SØRENSEN, 2011). Segundo Eco (1984, p. 127), metáfora é a função do formato sociocultural da interpretação do sujeito produzida unicamente na base de um enquadramento cultural rico.

8 Sullivan criou o único edifício da exposição fora da tradição neoclássica, de formas intricadas e coloridas decorações nas paredes, à revelia da organização.

9 Do original em inglês: “[…] Little Nemo dreams of a city that is not to be read by the panoptic gaze, a city where you have to walk […]” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 40).

10 Do original em inglês: “at the same time his dreams express the fear of the city […]” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 40).

11 Do original em inglês: “The desire for control is stronger than the lust to get lost” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 40).

12 Do original em inglês: “[…] in the dreams of Little Nemo, this gaze gains no control over the city. The same is true for the comic page. The gaze is forced to move and develops its own rhetoric of ambivalence between control and the loss of control. This is the struggle of power in the modern city that comics reveal. […]” (FRAHM, 2010, p. 44).

A DREAM BORN IN THE METROPOLIS: CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT THE MODERN CITY IN LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND

Tânia Alexandra Cardoso is Master in Urban Planning. She studies comics as an added value to scientific methods of city investigation, representation and criticism..

How to quote this text: Cardoso, T.A., 2016. A dream born in the metropolis: considerations about the modern city in Little Nemo in Slumberland. V!RUS, [e-journal] 12. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 24 April 2024].

Abstract:

The modern Era, of revolutionary and progressist nature, was a great catalyst, not only at an industrial level, but in terms of communication and rupture of past paradigms. In this period the representation of the city was particularly intense: studies and ambitious projects emerged as reformers of issues associated with urban problems of that time. It is also at this moment that Comics gain importance and prominence in Society and especially in the City. The representation of the city gains a new dimension; it becomes an element of inspiration. Windsor McCay was an artist ahead of his time. Is he himself a Radical Modern to question the zeitgeist and the development of modern cities through his graphic experiences and reflections present on his work Little Nemo in Slumberland?

Keywords:: urbanism; utopia; metaphor; comics.

Introduction

INTRODUCTION: THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN CITY1

Modern life derived from a revolutionary Era with great economic, political and social changes in the Western world. The major catalyst for this Era was the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century which shaped a typically bourgeois and capitalist society emphasizing industrial production and geared to a mass society at the expense of artisanal production.

After the Industrial Revolution, comes an impressive demographic growth of cities. The city became the dominant element in its relationship with the countryside and the urban population grew in a frightening and unregulated manner. From 1820 to 1870 the city is full of engines, canals and railways in a decentered pattern without a set limit. Until 1920 the industrial metropolis flourishes in a spirit of reform that gains strength as the cities became more complex (Warner, 1972).

The immigrant population grew visibly in industrial cities like Chicago or New York. Humanitarian thoughts, especially doctors and hygienists, denounce the state of physical and moral deterioration in which the laborers live. In the center and in the suburbs, they lived in unhealthy habitats, often away from the workplace or in slums crammed with dumpsters, with a high incidence of disease and mortality, and no green spaces (Choay, 1965, p.5). The unrestrained appropriation of space increased its unhealthiness, the housing deficit, public insecurity and poor infrastructure. Shantytowns and slums began to multiply (Scott, 1969, pp.6-7).

There is concern for the improvement of sanitary conditions of cities, education and the creation of a political and social awareness in the population. It was urgent to study the situation2 and propose an urban planning that would order the urban and social structure of the city. City-planners reform and develop cities and metropolitan areas through a large-scale planning (Scott, 1969, pp.1-7; Santos, 1988; Borges, 2012, p.22). With the development of transportation systems and communication means, the distances became shorter and connections multiplied destroying spatial barriers. The industries have established themselves in the suburbs causing daily commuting and therefore a dispersed and fragmented urban explosion. Life has accelerated and everyday life was changed accordingly.

Large tree-lined avenues were created, as well as boulevards, squares, parks and public gardens transforming underdeveloped areas into centers of urban life. Theaters, opera, cabarets, cafes, concert-cafes and vaudeville were increasingly being attended. This modus vivendi was reflected not only in the way of being and experience the city, but also in the way artists see, feel and represent the city (Choay, 1965, pp.1-5; Borges, 2012, p.21).

The urban man was different men. His life was different lives. [...] The events, facts, things were multiplying, and took place inordinately [...] The world of that man is massifying, however, he is increasingly aware of their individuality (Moya, 1972, p.04).

In the twentieth century, in response to the chaos of the big city, urban space was forced to the reins of functionality, seen as a whole around a utilitarian rationality. According to Françoise Choay (1965), various scholars of the city perfected projections of the future as an antithesis of the disorder, but many could not give a practical form to society issues thus staying in the field of utopia.

The city of Chicago became an example. The city expanded by attaching surrounding areas, making large infrastructural works and promising better conditions hoping to host the major exhibition of the quater-centenary of America's discovery, World's Columbian Exposition (1893). However, rather than marvel at the local industries on display, visitors were particularly delighted with the beauty and splendor of the exhibition buildings set (Scott, 1969, pp.31-33). According to Mel Scott (1969, p.45) the fair just gave a tangible shape to a desire that sprouted from a greater wealth in the city, from the vulgarization of travel and the search for an image that projected the national pride of a powerful country.

The Municipal Societies of Art, inspired by the 1893 exhibition organized by Daniel Burnham, began to gather to discuss the artistic development of cities. The key point to consider in these meetings was the city plan as the starting point, using as a model the city of ‘Haussmannian’ Paris. Classical and Renaissance works like the Parthenon or the Basilica of St. Peter were preferred for State buildings, extolling the city (Scott, 1969, pp.44-60).

The State and the logic of the market pointed to an increasing dominance of the consumer society and with it an enhancement of media for the dissemination of ideologies and policies. The instrumentalization of technical resources by the State machine and the Cultural industry were used as a process to reach many, seen not as people but as mass (Benjamin, 1994).

The city emerged in such mass media resources, not only honoring the great urban centers as a place of progress, social advancement, opportunities and major technological advances, but also spreading modern urban proposals in ‘spectacle’ images of the city.

DREAMING WITH THE PERFECT CITY

It is possible to consider that at the moment of Urbanism’s3 creation, based on epistemological ruptures, the importance of dissemination of ideas and development of education, is located at the same historical period of the birth of Comics. Both the drawings of Rodolphe Töpffer4 as the development of leaflets culminated in the creation of weekly comics in American newspapers in the turn of the nineteenth century to the twentieth. The big newspapers sought to provide information and entertain the masses with comic strips representing, mostly, the lives of immigrants and life in the big American city.

Life and urban development were driven by the printouts and content of the leaflets and newspapers and, accordingly, it is possible to consider a parallel. In this period the story Little Nemo in Slumberland of Winsor McCay stands out.

Starting by drawing circus posters in Art Nouveaux, Winsor McCay5 quickly exceeded his knowledge. His experiences and ruptures with tradition make him one of the most important figures of the History of Graphic Arts and Animation (Canemaker, 1987; Sendak, 1987; McCay, 1989).

Perhaps it is due to his entrepreneurial and intrepid spirit, the result of the innovation and the hectic pace of the period, or to the graphic features of his work that makes him relevant to the Modern Radicals theme. Little Nemo in Slumberland started to be published on October 15, 1905, in the New York Herald, until 1911, when it moved to the New York American until 1913. It was not a very popular comic compared to others, with a more humorous and satirical character like Krazy Kat by George Herriman or The Yellow Kid by Richard F. Outcault (Dorigatti, 2014).

In the story, Little Nemo is approached by a commissioner of King Morpheus who wants to show him the right way to get to the Kingdom of Dreams. McCay describes not only the child’s dreams but also creates incredibly rich worlds in beautiful and diverse details. His sensitivity to line, color and space is an expansion of his life surrounded by Vaudeville and the attractions of Coney Island. Nemo’s dreams are filled with clowns, acrobats, dancers, fantastic or grotesque animals, magicians and mirror halls (Winsor, 1989; Sendak, 1987).

Utopian and wonderful these cities act as an alternate universe. The existing visual signs in Little Nemo give information to the reader and carry him in his memory to real cities like New York or Chicago. To Adriana de Caúla and Silva (2002, pp.18-20), in her Master's thesis Imaginary Cities: Utopia, Urbanism and Comics, the work of Thomas More, Utopia, appears as a critical and antagonistic parody about English society of the sixteenth century, and the term Utopia has become characteristic of a range of projects and ideal, fantastic and imaginary civilizations. According to Quiring (2010, p.201) the ‘[...] imaginary city of memory is nothing but an enormous metaphor by which complex information is drawn together, condensed, and allegorically structured [...]’ in which the passage of time is spatial and where space is loaded with flows of experiences and meanings which come from real experience memory.

LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND BY WINSOR MCCAY

In 1893 rises in Chicago the promise of a White City, ‘a dream born over the swamps’ (Smoldener, 2010, p.26): the City Beautiful movement. Driven by Daniel Burnham city plans and by the Municipal Art Societies the movement intended to create a functional and human city, but mostly to restore its beauty (Hines, 2000). These ideals strongly shaped the imagination of Winsor McCay. Little Nemo in Slumberland is still one of the most influential comics worldwide. McCay was a man aimed at spectacle and together with the best typographers of the New York Herald met the ideal conditions to create Little Nemo. His dreamlike imagination lies in the figure of a boy who entertains and encourages the reader to wander through audacious worlds and magnificent architecture looking for a princess.

Language, according to Foucault (2002), is not the real representation, but it identifies with it. It is similar and different in the same space, but it is not its copy. This representation serves as a kind of bridge between the real and mimesis being neither one thing nor the other. In the representations of Little Nemo in Slumberland dreams often blend with reality, the boy does not seem to be aware that his dreams are not real, but another dimension, which represents the metamorphosed6 vision of McCay about reality.

These representations exploit the reorganization and the juxtaposition of architectural elements creating new spaces, with a fantastic image, of strong character and grandeur (Franco, 2012, p.8). They can almost be compared to the drawings of the Roman ruins of Giovanni Battista Piranesi presented in dream form, which he called Carceri, which resulted in a set of ‘magical and illusory images’ (Caúla e Silva, 2002, p.18). The approach of the imaginary creation in relation to the city experienced by the authors, in the case of Piranesi the city of Rome and McCay the city of Chicago/New York, puts them in the position of a graphic utopia, by the critical position of the authors facing real cities through the creation of their imaginary aspects.

In the pages published on March 29 and April 5 of 1908, Nemo comes to a devastated city and receives a baton of wishes to solve all the problems of the poor and oppressed, accordingly to the hygienist ideals of the time.

Magically, Nemo begins to change the dreams suburban neighborhoods, ugly, poor, dirty and depressing places. The streets are represented as constructions without harmony, the buildings are all different and arranged in a disorderly manner.

With a wave of the magic wand, the boy creates luxurious and wide boulevards in a Neoclassical style, reminiscent of the 1893 exhibition pavilions, and also creates large open spaces with lush gardens ‘fighting’ the sick spaces of the city.

The author adopts the position of the City Beautiful showing his predilection for civic order and beauty in a critical rationalism that envisions perfection relegating to the background social, economic and mobility issues (Scott, 1969, p.76-78). It is possible to compare the work of Richard F. Outcault, Yellow Kid, where the author showed the miserable state in which immigrants lived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, describing very plausibly the state of social segregation in cities (ghettos and shantytowns) in the center of large cities. Although they have very different approaches both authors sought to address issues and important social issues through humor.

In the page published on March 21 of 1909, the disorienting and frightening aspect of old neighborhoods is visible through McCay’s representations. Unlike King Morpheus city of the world of dreams, this city changes, grows rapidly and moves creating a threatening and claustrophobic atmosphere in a metaphor for the need for space due to rapid growth and uncontrolled transformation of cities (Warner, 1972).

Fig. 1: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 29 of March of 1908 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 2: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 5 of April of 1908 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 3: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 21 of march of 1909 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

On the 25 of February of 1906, Nemo comes to Slumberland Palace formed by concentric arches and decorated with lacy golden leaf. The porch that leads to the capital of dreams resembles the golden door of the Palace of Transports in the 1893 exhibition in Chicago, built by Louis Sullivan7. Coney Island, with its attractions and entertainment, is also a reference suggesting noble fun worlds and balancing forces between the unbridled amusements of fairs and the values of beauty, unity and order. McCay uses linear perspective prodigiously and boldly creating particularly detailed views especially in the representation of architecture and urban landscapes.

Fig. 4: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 25 of February of 1906 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

However, Little Nemo not only reflects the dream character of the city. In some of its pages McCay also shows the conflict between the panoptical view and the wandering through the city. At the pages of September of 1907, Nemo, is a giant in the middle of a city composed by tall buildings reminiscent of New York. The boy feels lost and tries to climb to a higher point in order to find a complete or panoptical view of the city. However, his gaze is limited by buildings of blind facades and opaque windows causing Nemo to say that he sees nothing even while looking at various buildings.

The creation of avenues with direct communication and unobstructed views were clear intensions of the City Beautiful movement. There is an intention for disproportionate control over the city and the lives of its residents (Scott, 1969, p.48, Warner, 1972, p.2). To Frahm (2010, p.40) ‘[…] Little Nemo dreams of a city that is not to be read by the panoptic gaze, a city where you have to walk […]’. Not able to find that totalizing view, Nemo finds himself completely lost and ‘[…] his dreams express the fear of the city […]’ (Frahm, 2010, p.40).

Fig. 5: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 15 of September of 1907 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 6: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 22 of September of 1907 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 7: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 29 of September of 1907 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 8: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 6 of October of 1907 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

The flow of the story is given by speech bubbles that guide the reader because the representation of the city, which grew out of control, is marked by a sense of claustrophobia and of labyrinth causing fear and alienation in the character: ‘the city is too big’ (Frahm, 2010, p.41). In the episodes of May of 1909, one lackey of the kingdom of Morpheus plans to build the Slumberland country in a vacant lot. He commands an army of Bobos to assemble and disassemble the city of dreams to his pleasure and can even make the city grow from the ground.

Fig. 9: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 23 of May of 1909 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 10: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 30 of May of 1909 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 11: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 6 of June of 1909 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

It seems to be a response to a previous sequence that shows the erosion of Art Nouveaux style in children's scribbles by a saboteur. What is the difference between the imagination of the character Flip, a child belonging to the People of Sunrise, with his scribbles, and the magician, who, like a city-planner, plans and solves the entire city's problems commanding an army of giants able to install the White City in a glance. The city is no longer a simple scenario and becomes the promise of a new world: a symbol of the American dream (Thévènet and Rambert, 2010, p.24; Smolderen, 2010, p.29).

McCay created the most surreal images: like cities where the houses grow legs and go walking along the street, shrinking cities and where Nemo becomes a giant, gardens full of giant mushrooms, talking animals and other dreamlike situations (Dorigatti, 2012). The author uses the own language of comics to intensify these surreal images and actions in the narrative.

In the page on the 22 of October of 1905, Nemo walks through a forest of giant mushrooms, the height of the frames is increased until the boy drops one of them, considered the narrative climax. From there the height of the frame starts to decrease as the forest falls creating a sense of claustrophobia and agony. The same graphic style is repeated in other boards, like in the one of 26 of July of 1908, in which his bed gets bigger and bigger legs, and as the story unfolds, the graphics accompany this growth.

Fig. 12: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 22 of October of 1905 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Fig. 13: Little Nemo in Slumberland, created by Winsor McCay; page originally published on the 26 of July of 1908 in the New York Herald.

Credits: Public domain; translation by Muraktama Lemos and Yuri Riccaldone.

Winsor McCay was a pioneer in experimenting with the formal elements of the pages of comics through its creative arrangement and through the design of the frames in order to increase the impact of the story and the expectation throughout the narrative. There is a direct connection between the use of the language of comics with the message to be transmitted to the public in an attempt to metalanguage. His innovative approach to the design and layout of the page has shown the potential of comics through experiments with scale, transformation, perspective and with the expression of his own point of view (Gravett, 2006).

Conclusion

Large urban transformations in modern cities in the late nineteenth century to the twentieth century were particularly inspiring for authors from different fields. There is a constant search for the ideal city, away from the problems and serious issues of modern cities such as overpopulation, poverty, informal growth, confusion, dirt or noise.

In Little Nemo, it is clear the desire and the need for control over the growth of the city in its representation. The author seeks mainly to represent the fear of complexity and lack of control of urban rhythm. ‘The desire for control is stronger than the lust to get lost’ (Frahm, 2010, p.40) and in that sense the panoptical gaze is what cleans the city of all its contradictions making it a timeless and controlled element (Frahm, 2010, p.43).

‘[…] in the dreams of Little Nemo, this gaze gains no control over the city. The same is true for the comic page. The gaze is forced to move and develops its own rhetoric of ambivalence between control and the loss of control. This is the struggle of power in the modern city that comics reveal. […]’ (Frahm, 2010, p.44)

McCay seeks beauty, control and harmony in his cities and his characters reflect the autocrat thoughts of the city-planners of the time. The author believed in an ideal city based on the City Beautiful movement and intended to convey the wonderful imagination of the time through Nemo’s travels reflecting the zeitgeist in the representation of the cities of the land of dreams. At the same time and through the use of visual signs, the shape of the buildings and their scale in relation to the boy, he wanted to show the terrible scenario that is being lost in the hurly burly of the unordered and unbalanced cities.

To Josep-Maria Montaner (1999, p.148) the essential component of any fiction is the time factor considering that the ‘author takes as its critical premise certain phenomenon of contemporary society [...] and extrapolates this situation until a specific date [...]’ where the city and society are described based on these premises, representing them in a very plausible way. For the author, the drawn architectures are common links between the various utopian fictions, whether literary, cinematic or comics, based on the ‘ability to represent through drawing a spatial and narrative reality’ (Montaner, 1999, p.152).

The artists use comics as an entertainment element in which they can represent and actively criticize urban life and issues related to the city's growth, seeking to convey a message through metaphors and comparisons with the prophesized cities in texts and projects of various artists, architects and scholars of this time.

The work of McCay could not have been created separately from the vibrant times of its creation (the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century). His work alludes to the growing introspection and civic awareness of the period reflecting the issues, urban transformations and his own commentary. The intrusion of reality in the world of dreams of Little Nemo shows that McCay is truly a Radical Modern due to his encouragement to experimentation in the graphical medium and promoting critical reflection through this language (Canemaker, 1987, p.259; O’Sullivan,1990, p.38).

Little Nemo was the great creation of McCay and revolutionized an entire industry not only for its graphical quality and visual experimentation but also for the social commentary that was not typical in comics of the time.

Even today, artists like Moebius, Schuiten & Peeters in their series of comic books, the ‘Obscure Cities’, Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Jean Philippe Bramanti; architects like Archigram and Superstudio in the 1960s, and more recently, Jimenez Lai, Rem Koolhaas and Jean Nouvel, raise relevant issues related to the present and the future through metaphors based on the modern cities’ premises and projects, in a mixture of questioning and wonder. Through the critical look of the author and its interpretation of reality it is possible to create fantastic new worlds. This reality is metamorphosed and expanded through the manipulation of the graphic language of comics and its narrative capacity. In this way it builds real meaning for imaginary places which are then decoded by the reader.

The potential of comics as a medium for representation and its meanings is well-known and is able to propose a critical look at the ways and ideals of modern life. The City Beautiful had the ability to show cities ‘of a past that America has never known’ (Scott, 1969, p.108) and through the use of comics these cities were fully lived and experienced by its readers.

REFERENCES

Benjamin, W., 1994. A obra de arte na era de sua reprodutibilidade técnica. In: Obras escolhidas, vol. I: Magia e técnica, arte e política: ensaios sobre a literatura e história da cultura. São Paulo: Brasiliense.

Borges, M., 2012. Comunicando a cidade em quadradinhos: do narrar ao fabular nos romances gráficos de Will Eisner. Doctorate degree. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo.

Canemaker, J., 1987. Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. New Yor: Abbeville.

Caúla e Silva, A., 2002. Cidades Imaginárias: Utopia, urbanismo e quadrinhos. Master degree. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Choay, F., 1992. O Urbanismo. 3rd ed. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. 1st ed. in 1965.

Da Silva, R., 1992. Da Cidade ao Urbanismo: Do Urbanismo à Cidade. Penélope: Fazer e desfazer a História, Lisboa, 7, pp.71-81. Available at: <http://www.penelope.ics.ul.pt/indices/penelope_07/07_08_RSilva.pdf> [Accessed 16 November 2013].

Dorigatti, B., 2011. Little Nemo em português. [Blog]. Available at: <http://www.riocomicon.com.br/little-nemo-em-portugues/> [Accessed 24 January 2014].

Eco, U., 1984. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Frahm, O., 2010. Every window tells a story: remarks on the urbanity of early comic strips. In: J. Ahrens & A. Meteling, eds. 2010. Comics and the city. London: The Continuum International, pp.32-44.

Franco, E., 2012. História em Quadrinhos e Arquitetura. 2nd ed. João Pessoa: Marca de Fantasia.

FOUCAULT, M., 2002. As palavras e as coisas, trad. S. T. Muchail, São Paulo: Martins fontes.

Gravett, P., 2006. Winsor McCay. Available at: <http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/winsor_mccay1> [Accessed 17 May 2016].

Hines, T. S., 2000. Architecture: The city beautiful movement. In: J. Grossman, A. D. Keating and J. Reiff, eds. 2000. The encyclopedia of Chicago. London: University of Chicago Press.

Montaner, J.-M., 1999. Ciudades imaginárias: utopias e distopias en el cinema y en los cómics. In: F, Fuão, ed. 1999. Arquiteturas Fantásticas. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, pp.147-163.

Moya, Á. De, 1972. SHAZAM! 2nd ed. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva.

O’Sullivan, J., 1990. The Great American Comic Strip: One Hundred Years of Cartoon Art. Boston: Bulfinch Press.

Quiring, B., 2010. A fiction that we must inhabit: Sense production in urban spaces according to Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell.J. Ahrens & A. Meteling, eds. 2010. Comics and the city. London: The Continuum International, pp.199-213.

Santos, M., 1999. A natureza do espaço: espaço e tempo, razão e emoção. 3rd ed. São Paulo: Hucitec.

Scott, M., 1971. American City Planning Since 1890. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. 1st ed. in 1969.

Sendak, M., 1987. Foreword. In: J. Canemaker, 1987. Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. New York: Abbeville.

Smolderen, T., 2010. Winsor McCay et ses héritiers. In: J. Thévènet & F. Rambert, eds. 2010. Archi&BD: La ville dessinée. Paris: Monografik éditions, pp.26-35.

Sorensen, B., 2011. The concept of metaphor according to the philosophers C. S. Peirce and U. Eco: a tentative comparison. Signs, 5, pp.29.

J. Thévènet and F. Rambert., 2010. Archi&BD: La ville dessinée. Paris: monografik éditions.

Waenwe Jr., S. B., 1972. The Urban Wilderness: A History of the American City. New York: Harper & Row.

1 This article is based on the Master's research in Urbanism ‘Urban Chronicles: Representation and Criticism of the city through Comics’ by Tânia A. Cardoso for the Program of Postgraduate Studies in Urbanism of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

2 Scholars of the Chicago School of Sociology, like Robert E. Park, were essential to find out who, why and how those places were inhabited. At the same time charitable entrepreneurs like William Kent and Jane Adams sought, through their own projects, to provide better conditions to the poorest class and consequently to the cities (Scott, 1969, pp.10-11).

3 It has appeared for the first time in Teoria general de la urbanización by Ildefonso Cerdá (1816-1876) in 1867 appointing ‘a new subject, intact and virgin 'that would have the status of' a real Science’ (da Silva, 1992, p.71).

4 Töpffer (1799-1846) is considered the father of comics. It was one of the first authors to use the sequential Art form to tell a narrative mixing image and text.

5 Born in 1867, McCAy was a graphic artist, a political cartoonist, a small editor, a vaudeville artist and an animator. He was strongly influenced by Grandville, Frost and mostly by Mucha’s Art Nouveaux style (Semdak, 1987).

6 According to the studies of Charles S. Pierce (1839-1914) and Umberto Eco (1936-2016) the metaphor highlights the process of representation, invention and interpretation; it also plays an important role in the generation of sense and knowledge (Sørensen, 2011). According to Eco (1984, p.127) ‘[...] metaphor is the role of socio-cultural format interpretation of the subject [...] only produced on the basis of a rich cultural environment [...]’.

7 Sullivan created the only building of the exhibition outside the neoclassical tradition; it had intricate shapes and colorful decorations on the walls, without the consent of the organization.