Espécies de espaços: notas sobre um exercício potencial

Marcelo Tramontano é Arquiteto e Livre-docente em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Professor Associado e pesquisador do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo (IAU-USP), onde coordena o Nomads.usp, Núcleo de Estudos de Habitares Interativos, e é editor-chefe da revista V!RUS..

Como citar esse texto: TRAMONTANO, M. Espécies de espaços: notas sobre um exercício potencial. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 12, 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=6&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 24 Abr. 2024.

Resumo:

Esse artigo discute o documentário "Espécies de espaços" (12'35"), realizado no Nomads.usp em 2015, relacionando-o ao romance homônimo do escritor francês Georges Perec e aos princípios que norteiam as ações do OuLiPo, Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle. Perec e os membros do OuLiPo referenciam-se no pensamento surgido, na França, no início da Renascença e consolidado nas primeiras décadas do século XX que questiona as formas clássicas da literatura e propõe a construção de escritos à maneira de jogos de palavras, explorando diversos dispositivos lingüísticos para expressar conteúdos muitas vezes banais ou propositalmente equívocos. A realização do vídeo inscreve-se no interesse do Núcleo pela investigação das possibilidades de uso do filme documentário como meio de leitura e expressão de realidades urbanas.

Palavras-chave:: Documentário, Espaço público, OuLiPo, Literatura, Moderno

Vídeo "Espécies de espaços". TRAMONTANO, 2015.

01

Nos últimos anos, o Nomads.usp, Núcleo de Estudos de Habitares Interativos, da Universidade de São Paulo, tem incluído em suas preocupações de pesquisa a utilização do filme documentário como meio de leitura e de expressão de realidades urbanas. Através de diversas ações, o Núcleo tem procurado explorar linguagens e narrativas audiovisuais com o objetivo de ampliar os procedimentos metodológicos habitualmente empregados por pesquisadores do espaço público. Se, por um lado, o gênero Documentário é, na pesquisa em Ciências Humanas, um método amplamente estudado, validado e aplicado, nos campos disciplinares da Arquitetura e do Urbanismo ele é, praticamente, um desconhecido.

O documentário "Espécies de Espaços" foi realizado em uma das ações do Nomads.usp que visavam aprofundar sua familiaridade com o gênero. Na tarde de 9 de outubro de 2015, nove pesquisadores, divididos em quatro grupos, gravaram imagens e sons em onze espaços públicos da cidade de São Carlos, cinco deles situados na região central e os demais em bairros periféricos. Um acordo inicial definiu que a captação de imagens priorizaria tomadas com a câmera estática ou movendo-se em panorâmicas horizontais, procurando registrar, de forma tão desierarquizada quanto possível, elementos constitutivos do espaço físico, por um lado, e dinâmicas da ocupação humana, por outro.

O vídeo apresentado nesse artigo representa uma das muitas possibilidades de montagem do material audiovisual então produzido coletivamente. A escolha narrativa da edição referencia-se no livro Espèces d'espaces (1974), do escritor francês Georges Perec, que discute a relação do autor com os espaços onde vive. No livro, eles são categorizados segundo uma escala de grandeza e de tangibilidade, na seguinte ordem: o espaço da página, da cama, do quarto, do apartamento, do edifício, da rua, do bairro, da cidade, do campo, do país, da Europa e do mundo. A condução da edição do vídeo baseou-se no capítulo La ville [A cidade].

02

Georges Perec nasceu em Paris, em 1936, de pais judeus poloneses, ambos mortos na Segunda Guerra Mundial: o pai, no campo de batalha, em 1940, e a mãe no campo de concentração de Auschwitz, em 1942. Colocado por sua mãe em um trem da Cruz Vermelha que levou dezenas de crianças para lugares seguros nos Alpes, Perec passa a infância em vilarejos do maciço do Vercors. Ele escreverá, mais tarde, diversos livros nos quais os temas da memória, da infância e da ausência são centrais.

Sua produção literária, diversas vezes reconhecida por importantes premiações nacionais francesas, será marcada por uma dupla formação: os estudos universitários em Letras, em Paris e em Túnis, e os dezesseis anos em que trabalhou como documentalista em neurofisiologia no Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa Científica, CNRS. O olhar que Perec propõe lançar sobre a cidade tem a poética e a imagética da literatura e o rigor, muitas vezes matemático, da documentação. Mas é no seio da associação de escritores OuLiPo que ele construirá sua carreira, precocemente interrompida com sua morte, em 1982, aos 45 anos de idade.

03

OuLiPo, ou Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle [Atelier de costura de Literatura Potencial], é uma associação fundada em 1960, conjuntamente pelo matemático François Le Lionnais e pelo escritor Raymond Queneau. Foi o primeiro de muitos ouvroirs criados em diferentes campos disciplinares, a partir da formulação de Queneau e Le Lionnais de um ouvroir genérico, o OuXPo, onde o X é substituído por letras referentes à área de conhecimento na qual os membros querem produzir pesquisas: OuMuPo (música), OuGraPo (grafismo), OuBaPo (histórias em quadrinhos), OuPeinPo (pintura), e mesmo um OuArchPo (arquitetura), criado em 2001, entre outros (FATRAZIE, s.d.). A base comum dos OuXPo é o interesse em explorar, especialmente do ponto de vista formal, os processos criativos em diversos campos, sempre utilizando-se do que chamam de contrainte artistique volontaire, ou restrição artística voluntária. Essa restrição constitui uma regra ou um conjunto de regras definido a priori para estimular e enquadrar o trabalho artístico, e deve ser rigorosamente respeitado. Sua natureza pode ser formal, teórica, plástica, temática, entre outros.

No OuLiPo, busca-se recombinar continuamente matemática e literatura. O objetivo é formular, através de exercícios, pontos de partida para obras literárias, e não necessariamente as obras em si (JAMES, 2006). É essa a ideia que o conceito de literatura potencial busca expressar. O conteúdo da obra importa menos do que a forma como ela é escrita e, especialmente, do que a aplicação das restrições artísticas definidas a priori. Ainda assim, diversos de seus membros, entre eles Italo Calvino, Raymond Queneau e o próprio Perec, produziram livros que ocupam lugar importante na literatura francesa recente. Um exemplo belíssimo e extremamente popular é Exercices de style, escrito por Queneau em 1947, que descreve brevemente uma mesma cena urbana parisiense, de 99 maneiras diferentes. Outro exemplo é o texto Un peu moins de vingt mille incipits inédits de Georges Perec [Um pouco menos de vinte mil inícios inéditos de Georges Perec] (PEREC, 1990), que oferece uma matriz combinatória de ordem 9X3, composta de 27 trechos para o início de um romance, totalizando 19.683 possibilidades de recombinação oferecidas ao leitor (esse número é informado pelo próprio autor em uma anotação na margem do manuscrito). Além de "Espécies de espaços", Perec escreveu obras importantíssimas que exploram os princípios oulipianos, como La disparition [O desaparecimento], que enfatiza a ideia de ausência com a supressão da letra 'e' ao longo de todo o texto. A decisão de não se utilizar a letra 'e' constitui, nesse caso, o que os membros do grupo chamam de restrição artística voluntária.

04

Uma das principais referências do OuLiPo são os grands rhétoriqueurs, poetas e escritores do início da Renascença que trabalhavam e eram sustentados por nobres e poderosos para celebrar sua grandeza. Esses literatos já exercitavam a construção de escritos à maneira de jogos de palavras, explorando diversos dispositivos lingüísticos para expressar conteúdos muitas vezes banais ou propositalmente equívocos. Pierre Badel (1984), citando o famoso estudo de Paul Zumthor, Le Masque et la lumière: la poétique des grands rhétoriqueurs, de 1978, escreve que

[...] os rhétoriqueurs são de uma espantosa modernidade. Eles não foram teóricos; contudo, sua prática coloca questões profundas relativas à linguagem, aos processos da significação e da compreensão, ao texto, à escrita. [...] As rimas complexas, todos os procedimentos que Zumthor chama de malabarismos, têm por efeito tornar o discurso e seu sentido óbvio fundalmentalmente ambíguos. As rimas raras, os malabarismos espetaculares, as ambiguidades, liberam o significante, pulverizam o sentido, estouram a máscara da representação e questionam, a partir do interior, os valores estabelecidos (BADEL, 1984, p. 4-5).1

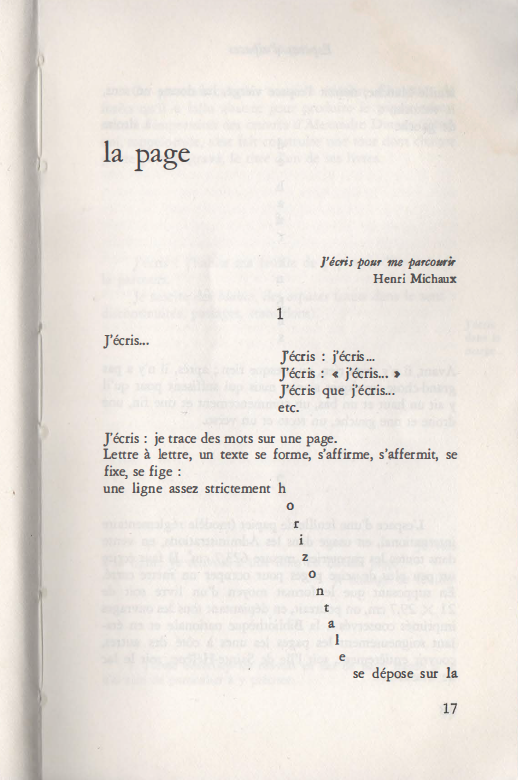

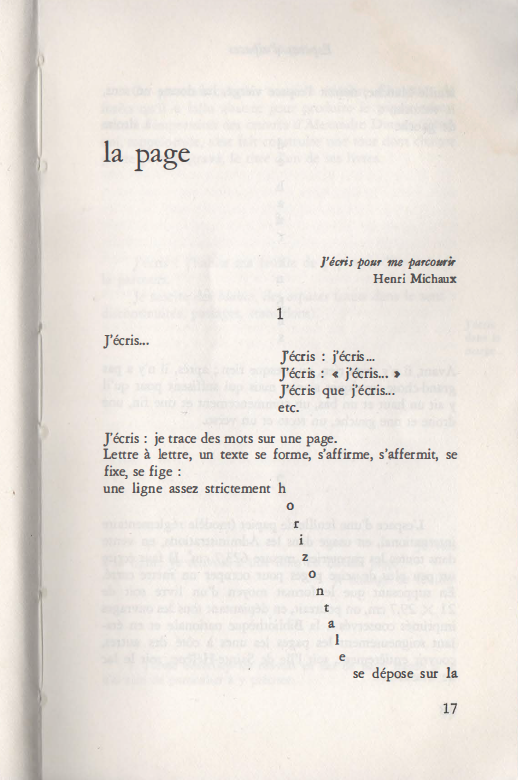

De fato, mais do que dos dispositivos lingüísticos, OuLiPo e Perec apropriam-se da postura literária dos rhétoriqueurs de oferecer um conjunto de elementos e figuras ao leitor, que dispõe, por sua vez, de inúmeras maneiras de recombiná-los e interpretá-los, de forma a produzir sentidos variados sobre a mensagem que se quer transmitir. Veremos essa mesma postura na obra de escritores e poetas modernos do início do século XX, ligados a movimentos como o Futurismo, Dadaísmo, Surrealismo - dentre eles, Paul Éluard, Mario Carli, Jean Cocteau e Guillaume Apollinaire - que consistiram em um elo importante entre os grands rhétoriqueurs e OuLiPo, como sugere Camille Bloomfield (2013). Parece, efetivamente, haver uma correlação clara entre as experimentações pictóricas e gráficas características dessa época, que exploram a ideia emergente de abstração, e a escrita que considera a página do livro como campo visual, que abre mão da estrutura tradicional das frases, prenunciando o que será a poesia concreta dos anos 1950. Um exemplo é a primeira página do capítulo La page [A página], primeira escala espacial tratada por Perec em Espèces d'espaces (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: La page. Página inicial do capítulo. Fonte: PEREC, 1974.

05

A estrutura do capítulo La ville [A cidade] assemelha-se mais a um conjunto de notas esparsas sobre como observá-la do que propriamente a um texto que busca dissertar sobre o tema. O primeiro parágrafo já soa como um alerta: "Não tentar rápido demais encontrar uma definição da cidade; isso é demasiado grande, tem-se todas as chances de se enganar"2. Seguem diversas instruções para quem deseja aproximar o objeto urbano. Perec insta o leitor a evitar atribuir sentidos ao que vê, permitindo-se apreender o visível com uma atitude quase documentalista: "Primeiro, fazer o inventário do que se vê. Recensear aquilo de que se tem certeza. Estabelecer distinções elementares: por exemplo, entre o que é a cidade e o que não é a cidade"3.

Está implícita em seu discurso uma compreensão da cidade a partir da dicotomia centro-periferia, ainda que ele duvide de sua perenidade, frente aos processos históricos de expansão da malha urbana. Ele recorda como Paris se expandiu incluindo em seu território vilarejos que se situavam no exterior de suas muralhas, lembra que esses limites físicos não existem mais, mas que existem outros, de diferentes naturezas: "Interessar-se ao que separa a cidade do que não é a cidade. Olhar o que acontece quando a cidade termina. [...] Reconhecer que as periferias têm forte tendência a não permanecer periferias"4.

Finalmente, Perec sugere um brevíssimo método, como ele próprio chama o seguinte parágrafo:

Seria necessário, ou renunciar a falar da cidade, a falar sobre a cidade, ou então obrigar-se a falar da maneira mais simples do mundo, falar dela de maneira evidente, familiar. Afugentar qualquer ideia pré-concebida. Parar de pensar em termos pré-preparados, esquecer o que disseram os urbanistas e os sociólogos5

06

O vídeo "Espécies de espaços", do Nomads.usp, corrobora, ilustra e desenvolve, em meio audiovisual, algumas das questões enunciadas nos parágrafos acima.

1. A ação acordada entre os pesquisadores foi formulada como um exercício capaz de produzir ideias para o desenvolvimento de documentários sobre a cidade, e não como um filme em si. O vídeo reúne, portanto, algumas possibilidades, imaginadas na edição, de emprego do audiovisual para a construção de leituras urbanas.

2. Em praticamente todas as tomadas, a câmera foi mantida fixa ou em movimento panorâmico, o panning, no jargão cinematográfico, em que a câmera é girada lenta e horizontalmente em torno de seu próprio eixo vertical. Essas escolhas visaram enfatizar a busca de uma certa neutralidade do olhar em relação aos espaços observados, um olhar que não se atém a particularidades da cena que observa, mas obedece a movimentos pré-definidos.

3. As imagens em panning encadeiam-se, sem interrupções, sempre levando o olhar da esquerda para a direita do observador, de forma contínua. Ainda que os locais registrados distem, às vezes, de alguns quilômetros entre si, a sequência verifica a possibilidade de se dar a entender a cidade como um ente uno, como um grande espaço público aberto ao uso de seus habitantes, periferia e centro confundidos.

4. As cores das imagens captadas foram substituídas por escalas de cinza ou escalas combinando tons de cinza e de vermelho. Parte-se aqui da hipótese de que muitas das atribuições de valor, de função e de importância na paisagem são assinaladas através do uso de cores nos edifícios e nos vários elementos que compõem o espaço físico. Dessa perspectiva, também os tons de verde das massas vegetais e as cores variadas das roupas das pessoas atrairiam a atenção do observador de maneira desigual, em função do seu interesse e dos valores que ele próprio atribui a cada cor. Quis-se, portanto, testar a capacidade dessa estratégia de levar a enxergar os espaços e os objetos urbanos principalmente como planos, massas e volumes, de realçar seus movimentos e deslocamentos, em diferentes situações de iluminação, dificultando apreensões usuais e quotidianas.

5. Com a mesma intenção, o som captado diretamente foi substituído, na maioria das cenas, por uma trilha contínua composta de uma única peça musical, de autoria de Iánnis Xenákis. O uso da música experimental de Xenákis buscou acrescentar à experiência de observação uma ambiência sonora completamente diferente da usual, visando a minimização de referências sonoras locais e reforçando um esgarçamento das relações de familiaridade do observador com seus espaços quotidianos.

6. As cenas do vídeo ora oferecem uma observação que priorizam o espaço físico e seus elementos constitutivos, ora convidam a observar a ocupação humana deste espaço. Essa categorização remete a uma postura próxima da documentação do que se vê, quase descritiva, de identificação e reconhecimento, sugerindo um procedimento para a leitura que desmembra a complexidade dos espaços observados em layers assim simplificados.

7. As atividades humanas são exibidas em telas quadripartidas, em imagens tratadas em escalas de vermelho e cinza, evocando a observação através de câmeras de vigilância. Esse recurso lembra ao observador a atitude panóptica do ver-sem-ser-visto da vigilância urbana, sugerindo que essa é também uma característica da atitude de quem filma anonimamente cenas de convívio em lugares públicos. O observador não faz parte dos jogos, nem das atividades esportivas ou comerciais, mas ainda assim, parado nesse lugar com sua câmera, faz parte desse sistema.

8. No processo de montagem e edição, a fala do único entrevistado do vídeo foi recortada em frases, e algumas de suas expressões foram isoladas do seu discurso. As diversas partes foram recombinadas sugerindo novas compreensões de sua fala, experimentando, assim, possibilidades de se reforçar certas ideias expressas na entrevista. O uso desse recurso tem também a intenção de salientar que, em um filme documentário, a produção de conhecimento registrada em uma entrevista é uma construção a várias mãos, envolvendo aquele que fala, quem escuta, quem registra, e aquele que edita os registros imagéticos e sonoros a partir de suas próprias convicções e entendimento do assunto abordado na entrevista.

07

Finalizaremos essas breves notas lembrando que a escolha da música de Iánnis Xenákis para a trilha sonora do vídeo contém algumas citações modernas. Nascido em 1922, na Romênia, de pais gregos, Xenákis viveu em Paris de 1945 a 2001, ano de sua morte. Foi músico, engenheiro e arquiteto, trabalhou no escritório de Le Corbusier como chefe de projeto do Convento de La Tourette, de 1957, e do Pavilhão Philips, de 1958. Suas inquietações sobre possíveis relações entre música e arquitetura, mediadas pela matemática, produziram inúmeras peças musicais cujas sonoridades completamente novas constituem, até hoje, referências maiores na música eletrônica.

La Légende d'Eer, peça escolhida para o vídeo "Espécies de espaços", foi executada pela primeira vez publicamente em 1977, na inauguração do Centro Georges Pompidou, em Paris, na piazza em frente ao Centro, um dos espaços públicos mais célebres do planeta.

AGRADECIMENTO

Aos oito pesquisadores do Nomads.usp que, junto comigo, se interessaram em lançar esse olhar coletivo sobre o espaço público, em uma tarde de primavera tropical: Anibal Pereira Junior, Dyego Digiandomenico, Flavia Dias, Gabriele Landim, Guilherme Mayrinck, Jessica Tardivo, Maria Julia Martins e Nayara Benatti.

REFERÊNCIAS

BADEL, P. Y. La Rhétorique des grands rhétoriqueurs. Bulletin de l'Association d'Étude sur l'Humanisme, la Réforme et la Renaissance, v. 18, n. 1, p. 3-11, 1984.

BLOOMFIELD, C. L’Oulipo dans l'histoire des groupes et mouvements littéraires. In: BISENIUS-PENIN, C.; PETITJEAN, A. (Org.) 50 ans d’Oulipo. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013. p. 29-44.

ESPÉCIES de espaços. Diretor: Marcelo Tramontano. [vídeo] 12'35'. São Carlos: Nomads.usp, 2015. Disponível em https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68LXf6kGuUs

FATRAZIE. OuXPo. [s.d.] [Blog] Disponível em:

JAMES, A. Pour un modèle diagrammatique de la contrainte: l'écriture oulipienne de Georges Perec. Cahiers de l'Association internationale des études francaises, n. 58, p. 379-404, 2006.

PEREC, G. Espèces d'espaces. Paris: Galilée, 1974.

PEREC, G. Un peu moins de vingt mille incipit inédits de Georges Perec. Études littéraires, v. 23, n. 1-2, p. 205-207, verão-outono 1990. Disponível em:

1 Todas as citações em francês constantes desse artigo foram traduzidas pelo autor. Do original em francês: "[...] les rhétoriqueurs sont d'une étonnante modernité. Ils n'ont pas été des théoriciens; néanmoins leur pratique pose de profondes questions relatives au langage, aux processus de la signification et de la compréhension, au texte, à l'écriture. [...] Les rimes complexes, tous les procédés que Zumthor nomme jongleries, ont pour effet de rendre le discours tenu et son sens obvie fondamentalement équivoques. Les rimes rares, les jongleries spectaculaires, les équivoques, libèrent le signifiant, pulvérisent le sens, crèvent le masque de la représentation et remettent en cause de l'intérieur les valeurs établies".

2 Todas as citações de Georges Perec foram extraídas de seu livro Espèces d'espaces, 1974. Do original em francês: "Ne pas essayer trop vite de trouver une définition de la ville; c'est beaucoup trop gros, on a toutes les chances de se tromper".

3 Do original em francês: "D'abord, faire l'inventaire de ce que l'on voit. Recenser ce dont l'on est sûr. Etablir des distinctions élémentaires: par exemple entre ce qui est la ville et ce qui n'est pas la ville".

4 Do original em francês: "S'intéresser à ce qui sépare la ville de ce qui n'est pas la ville. Regarder ce qui se passe quand la ville s'arrête. (...) Reconnaître que les banlieues ont fortement tendance à ne pas rester banlieues".

5 Do original em francês: "Il faudrait, ou bien renoncer à parler de la ville, à parler sur la ville, ou bien s'obliger à parler le plus simplement du monde, en parler évidemment, familièrement. Chasser toute idée préconçue. Cesser de penser en termes tout préparés, oublier ce qu'ont dit les urbanistes et les sociologues".

SPECIES OF SPACES: NOTES ON A POTENTIAL EXERCISE

Marcelo Tramontano is Architect and Livre Docente in Architecture and Urbanism, and Associate Professor and researcher at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, IAU-USP, of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. He directs the Nomads.usp, Center for Interactive Living Studies, and is the Editor-in-Chief of V!RUS journal..

How to quote this text: Tramontano, M., 2016. Species of spaces: notes on a potential exercise. V!RUS, [e-journal] 12. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=6&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 24 April 2024].

Abstract:

This article discusses the documentary 'Species of spaces', produced at Nomads.usp, the Center of Interactive Living Studies, in 2015, relating it to the homonymous novel by French writer Georges Perec and the principles that guide the actions of OuLiPo, the Ouvroir of Littérature Potentielle. Perec and the members of OuLiPo refer on the ideas developed in France in the early Renaissance and consolidated in the first decades of the twentieth century that question the classical forms of literature and propose the construction of writings in the manner of a wordplay, exploring different linguistic devices to express contents often trivial or deliberately misunderstanding. The video production falls within the Center interest for investigating possibilities of using documentary film as a means of reading and expressing urban realities.

Keywords:: Documentary, Public space, OuLiPo, Literature, Modern

Video 'Species of spaces'. Tramontano, 2015.

01

In recent years, Nomads.usp, the Center for Interactive Living Studies of the University of São Paulo, Brazil, has included in its research concerns the use of documentary film as a means of reading and expressing urban realities. Through several initiatives, the Center has sought to explore audiovisual languages and narratives aiming at expanding methodological procedures commonly used by researchers on public space. If, on the one hand, documentary genre is, within the Human Sciences research, a widely studied method, validated and applied, in the academic fields of Architecture and Urbanism it is virtually a stranger.

The documentary 'Species of spaces' was produced in one of Nomads.usp actions aimed at deepening the familiarity of the group with this film genre. On the afternoon of October 9, 2015, nine researchers, divided into four groups, recorded images and sounds in eleven public spaces of the city of Sao Carlos, five of them located in the central region and the other in peripheral neighborhoods. An initial agreement defined that capture would prioritize images taken with the camera in a static position or moving in horizontal panning, searching to record, with minimal hierarchy, components of the physical space, on the one hand, and the dynamics of human occupation, on the other hand.

The video presented in this article represents one of many cutting possibilities of the audiovisual material then produced collectively. The edition narrative choice refers on the book Espèces d'espaces (1974), by French writer Georges Perec, which discusses the author's relationship with the spaces in which he lives. In the book, they are categorized on a scale of size and tangibility, in the following order: the space of the page, the space of the bed, of the room, of the apartment, of the building, of the street, of the neighborhood, of the city, of the countryside, of the nation, of Europe and of the world. Video editing ideas were based on the chapter La ville [The city].

02

Georges Perec was born in Paris in 1936 from Polish Jewish parents, both killed in World War II: the father on the battlefield in 1940, and the mother in the concentration camp of Auschwitz in 1942. Placed by his mother in a train of the Red Cross that took dozens of children to safe places in the Alps, Perec spent his childhood in villages within the Vercors massif. He will write later several books in which the themes of memory, childhood and absence are central.

His literary production, repeatedly recognized by major French national awards, was marked by a double education: his universitary studies in literature in Paris and Tunis, and the sixteen years period he worked as a documentalist in neurophysiology at the National Council for Scientific Research, CNRS. The glance Perec proposes on the city has both poetics and imagistic from the literature, as well as rigor, often mathematical, from documentation. It is however as a member of the OuLiPo writers association that he will build his career prematurely interrupted by his death in 1982, at 45 years old.

03

OuLiPo, or the Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle [Sewing Atelier of Potential Literature], is an association founded in 1960 jointly by mathematician François Le Lionnais and writer Raymond Queneau. It was the first of many ouvroirs created in different disciplines, from the Queneau and Le Lionnais formulation of a generic ouvroir, the OuXPo, where X can be replaced by letters referring to the knowledge area in which members want to produce research: OuMuPo (music), OuGraPo (graphics), OuBaPo (comics), OuPeinPo (painting), and even a OuArchPo (architecture), established in 2001, among others (Fatrazie, n.d.). The common basis of all OuXPo is the desire to explore, especially from a formal point of view, creative processes in various fields, always using what they call contrainte artistique volontaire, or voluntary artistic restriction. Such restriction is a rule or set of rules defined a priori to stimulate and frame the artwork, and must be strictly respected. His nature can be formal, theoretical, plastic, thematic, among others.

At OuLiPo, one seeks to recombine continuously mathematics and literature. The aim is to formulate, through exercises, starting points for literary works, and not necessarily the works themselves (James, 2006). This is the idea that the potential literature concept seeks to express. The content of the work matters less than the way it is written, and especially than the application of artistic restrictions previously defined. Still, several of its members, including Italo Calvino, Raymond Queneau and Perec himself, produced books that occupy a major place in recent French literature. A stunningly beautiful and extremely popular example is Exercices de style, written by Queneau in 1947, which briefly describes a single Parisian urban scene in 99 different ways. Another example is the text Un peu moins de vingt mille incipits inédits de Georges Perec [A little less than twenty thousand unpublished begginings of Georges Perec] (Perec, 1990), which offers a combinatorial matrix 9 x 3, composed of 27 snippets for the beginning of a romance, totaling 19,683 recombination possibilities offered to the reader (this number is informed by the author in a note on the manuscript margin). Besides Espèces d'espace, Perec wrote very important works that explore oulipian principles such as La disparition [literally, The disappearance], which emphasizes the idea of absence with the suppression of the letter 'e' throughout the text. The decision not to use the letter 'e' is, in this case, what the group members call a voluntary artistic restriction.

04

One of the main OuLiPo references are the grands rhétoriqueurs, who were poets and writers of the early Renaissance who worked to and were supported by nobles and lords to celebrate their greatness. These writers already exercised the construction of writings in the manner of wordplays, exploring various linguistic devices to express contents often trivial or deliberately misunderstanding. Pierre Badel (1984), quoting the famous study of Paul Zumthor, Le Masque et la lumière: la poétique des grands rhétoriqueurs, from 1978, writes that

‘[...] the rhétoriqueurs are surprisingly modern. They were not theorists; nevertheless their practice raises profound questions relating to language, to the processes of meaning and understanding, to the text, to writing. [...] The complex rhymes, all procedures that Zumthor calls juggling, have the effect of making the given speech and its obvious meaning fundamentally ambiguous. Rare rhymes, spectacular juggling, ambiguities, release the meaning, pulverize the sense, burst the mask of representation and question from inside established values’ (Badel, 1984, pp.4-5). 1

In fact, more than linguistic devices, OuLiPo and Perec appropriated the rhétoriqueurs literary approach of offering a set of elements and figures to the reader. This latter has, in turn, countless ways to recombine them and interpret them, to produce different meanings about the message they want to convey. We will see the same approach in the work of writers and modern poets of the early twentieth century, connected to artistic movements such as Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism - among them, Paul Eluard, Mario Carli, Jean Cocteau and Guillaume Apollinaire - who remain an important link between the grands rhétoriqueurs and OuLiPo, as suggested by Camille Bloomfield (2013). It seems, indeed, there is a clear correlation between pictorial and graphic experiments, typical of that time, which explore the emerging idea of abstraction, and writings that consider the book page as visual field, giving up the traditional structure of sentences, foreshadowing what will be concrete poetry in the 1950s. An example is the first page of the chapter La page [The page], the first space scale treated by Perec in Espèces d'espaces (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: La page. First chapter page. Source: PEREC, 1974.

05

The structure of the chapter La ville [The city] is more like a set of sparse notes on how to observe cities than actually a text which seeks to elaborate on the subject. The first paragraph already sounds like a warning: 'Do not try too quickly to find a definition of the city; it's too big, one has every chance of being wrong'2. Follow new instructions for those who want to approach the urban object. Perec urges the reader to avoid assign meanings to what he or she sees, allowing oneself to grasp the visible with an almost documentalist attitude: 'First, take inventory of what you see. Identify what you are sure. Establish basic distinctions: for example, between what is city and what is not the city'3. Implicit in his speech is an understanding of the city based on the center-periphery dichotomy, even though he doubts its durability, given the historical expansion processes of the urban network. He recalls how Paris has expanded including in its territory villages that were located outside its walls. He points out that these physical boundaries no longer exist, but there are others, of different natures: 'Be interested in what separates the city of what is not the city. Watch what happens when the city stops. [...] Recognize that suburbs have a strong tendency not to remain suburbs'4.

Finally, Perec suggests a briefest method, as he himself calls the following paragraph:

'It should, either give up to speaking on the city, to speaking about the city, or to force oneself to speak the simplest of the world, to speak obviously, familiarly. Drive off all preconceived ideas. Stop thinking in all prepared words, forget what was said by urban planners and sociologists.'5

06

The Nomads.usp video 'Species of spaces' corroborates, illustrates and develops in audiovisual medium some of the issues set out in the paragraphs above.

1. The action agreed by researchers was formulated as an exercise expected to produce ideas for the development of documentaries about the city, and not as a film itself. The video brings some possibilities, imagined in the editing process for audiovisual works on the construction of urban readings.

2. In almost every shot, the camera was maintained steady or in panning, which means, in film jargon, moving the camera slowly and horizontally around its own vertical axis. These choices were aimed at emphasizing the search for a certain neutrality of the look to the observed places. That is, a look which does not hold particularities of the observed scene, but obeys predefined restrictions.

3. The images in panning chain together without interruption, always taking the look from the left to the right hand of the observer, continuously. Although the shot locations are distant sometimes a few kilometers from each other, the sequence checks the possibility to visualize a way of understanding the city as a whole entity, as a large public space open to the use of its inhabitants, periphery and center merged.

4. The colors of the images captured were replaced by a gray scale or scales combining shades of gray and red. This raises the assumption that many of the assigned value, function and significance in the landscape are highlighted through the use of colors, on buildings as on the various elements composing physical space. From this perspective, also the green tones of vegetation and the varied colors of the individuals clothes attract the observer's attention unequally, depending on his or her own interest and the values he or she gives to each color. It was wanted, therefore, to test the relevance of using this strategy to see urban areas and objects as mainly plans, masses and volumes, to emphasize their movements and displacements under different lighting conditions, avoiding the usual daily understandings.

5. With the same intention, directly recorded sound was replaced in most scenes by a continuous soundtrack composed of a single musical piece, written by Iánnis Xenákis. The use of Xenákis's experimental music sought to add to the watching experience a sound ambience completely different from usual, targeting at minimizing local sound references and reinforcing a stretching of the observer's familiarity relationships with his or her everyday spaces.

6. Video scenes offer either an observation prioritizing physical space and its constituent elements, or invite one to observe human occupation of this space. This categorization leads into a nearly documentation attitude of what can be seen, almost descriptive, of identification and recognition, suggesting a procedure for readings that dismember the complexity of observed places in layers thus simplified.

7. Human activities are displayed in quadripartite screens, into images treated in red and gray scales, evoking the observation through surveillance cameras. This feature reminds the observer the panoptic attitude of the seeing-without-being-seen urban surveillance, suggesting that this is also a characteristic of the attitude of someone who films anonymously convivial scenes in public places. The observer is not part of the games nor of sporting or commercial activities but still, standing in that place with the camera, is part of this system.

8. In the process of cutting and editing, the speech of the single person interviewed on the video was cut in sentences, and some of his expressions were isolated from the speech. The various parts were recombined suggesting new understandings of his speech, thus testing possibilities to reinforce certain ideas expressed in the interview. The use of this feature also intends to point out that, in a documentary film, the production of knowledge recorded in an interview is a construction by several hands, involving the one who speaks, the listener, the one who registers, and the one who edits the records in image and sound from his or her own beliefs and understanding of the subject addressed in the interview.

07

We finalize these brief notes remarking that the choice of Iánnis Xenákis' song to the video soundtrack contains some modern quotations. Born in 1922 in Romania, from Greek parents, Xenákis lived in Paris from 1945 to 2001, the year of his death. He was a musician, engineer and architect, and worked at Le Corbusier's office as the head of La Tourette Convent (1957) and the Philips Pavilion (1958) projects. His concerns about possible links between music and architecture, mediated by mathematics, resulted in numerous musical pieces whose completely new sonorities are, to this day, major references in electronic music.

La Légende d'Eer, the musical piece chosen for the video 'Species of spaces' was first performed publicly in 1977, at the opening of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, in the piazza in front of the Center, which is one of the most celebrated public places on the planet.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the eight Nomads.usp researchers who had been interested to launch with me this collective glance on public space, in a tropical spring afternoon: Anibal Pereira Junior, Dyego Digiandomenico, Flavia Dias, Gabriele Landim, Guilherme Mayrinck, Jessica Tardivo, Maria Julia Martins and Nayara Benatti.

REFERENCES

Badel, P. Y., 1984. La Rhétorique des grands rhétoriqueurs. Bulletin de l'Association d'Étude sur l'Humanisme, la Réforme et la Renaissance, 18 (1), pp. 3-11. Available at:

Bloomfield, C., 2013. L’Oulipo dans l'histoire des groupes et mouvements littéraires. In: Bisenius-Penin, Carole & Petitjean, André. (Org.) 50 ans d’Oulipo. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 29-44. Available at:

Fatrazie, n.d. OuXPo. Available at:

James, A., 2006. Pour un modèle diagrammatique de la contrainte: l'écriture oulipienne de Georges Perec. Cahiers de l'Association internationale des études francaises, 58. pp.379-404. Available at:

PEREC, G. Espèces d'espaces. Paris: Galilée, 1974.

PEREC, G., 1990. Un peu moins de vingt mille incipit inédits de Georges Perec. Études littéraires, 23 (1-2), summer-autumn, pp.205-207. Available at:

Tramontano, M., 2015. Species of spaces. [video online] 12'35'. São Carlos: Nomads.usp. Available at:

1 All quotes in French have been translated by the author. From original in French: ‘[...] les rhétoriqueurs sont d'une étonnante modernité. Ils n'ont pas été des théoriciens; néanmoins leur pratique pose de profondes questions relatives au langage, aux processus de la signification et de la compréhension, au texte, à l'écriture. [...] Les rimes complexes, tous les procédés que Zumthor nomme jongleries, ont pour effet de rendre le discours tenu et son sens obvie fondamentalement équivoques. Les rimes rares, les jongleries spectaculaires, les équivoques, libèrent le signifiant, pulvérisent le sens, crèvent le masque de la représentation et remettent en cause de l'intérieur les valeurs établies.'

2 All quotings of Georges Perec refer to his book Espèces d'espaces, 1974. From original in French: 'Ne pas essayer trop vite de trouver une définition de la ville; c'est beaucoup trop gros, on a toutes les chances de se tromper'.

3 From original in French: 'D'abord, faire l'inventaire de ce que l'on voit. Recenser ce dont l'on est sûr. Etablir des distinctions élémentaires: par exemple entre ce qui est la ville et ce qui n'est pas la ville'.

4 From original in French: 'S'intéresser à ce qui sépare la ville de ce qui n'est pas la ville. Regarder ce qui se passe quand la ville s'arrête. (...) Reconnaître que les banlieues ont fortement tendance à ne pas rester banlieues'.

5 From original in French: 'Il faudrait, ou bien renoncer à parler de la ville, à parler sur la ville, ou bien s'obliger à parler le plus simplement du monde, en parler évidemment, familièrement. Chasser toute idée préconçue. Cesser de penser en termes tout préparés, oublier ce qu'ont dit les urbanistes et les sociologues'.