Quão cibernética é a parametrização?

Anja Pratschke é Arquiteta e Doutora em Ciências da Computação, professora e pesquisadora do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo e Co-coordenadora do Nomads.usp - Núcleo de Estudos sobre Habitares Interativos, onde desenvolve e orienta pesquisas nas áreas de Processos de Design e Comunicação em Arquitetura.

Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi é Arquiteta e Urbanista. Pesquisa aspectos cibernéticos dos processos de projeto arquitetônicos no Nomads.usp - Núcleo de Estudos sobre Habitares Interativos, da Universidade de São Paulo.

Como citar esse texto: PRATSCHKE, A.; DI STASI, M.G. Quão cibernética é a parametrização? V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 11, 2015. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus11/?sec=6&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 01 Jul. 2025.

"And what takes the place of philosophy now?

HEIDEGGER: Cybernetics. Entrevista para a revista Der Spiegel, Alemanha, 1966.

A parametrização está sendo introduzida há anos na formação e em projetos arquitetônicos ao redor do mundo. Para ser usado no seu potencial pleno, demanda uma revisão no foco atual quanto a busca por forma, ainda muitas vezes parte central da prática e educação projetual. Segundo Hugh Dubberly, a mudança deve concentrar-se no planejamento do processo como um todo, estabelecendo as relações entre objeto e ambiente, e o ator que os ocupa (DUBBERLY, 2008, p. 9).

A parametrização não é nova, nasceu inicialmente com o desenvolvimento do Sketchpad por Ivan Sutherland em 1963, “um mecanismo baseado em propagação e ao mesmo tempo um solucionador simultâneo.” (WOODBURY, 2010). O Design Paramétrico deriva da Teoria de Grafos e, dentro dessa, do sistema baseado em propagação, que parte do princípio de que o usuário organiza o grafo, para que ele possa ser resolvido diretamente. Segundo Robert Woodbury, este é o tipo mais simples de sistema paramétrico, organizando objetos para que a informação conhecida seja base para a informação não conhecida. Conhecer as teorias por trás do design paramétrico, os princípios, as vantagens e campos de conhecimento necessários para dominar o modo de fazer, ou seja, projetar com código, focando no gerenciamento da informação e da sua visibilidade em áreas como Modelação da Informação da Construção (BIM) e Arquivo para Fabrica (file to factory), torna-se estratégia de sobrevivência profissional em um mercado competitivo e internacional baseado em competências (WOODBURY, 2010).

Ultrapassando o modo convencional de adicionar e apagar decisões projetuais, a parametrização acrescenta a possibilidade de relacionar e modificar partes do projeto dentro do conjunto coordenado, partindo da compreensão de que mudanças fundamentais trazem alterações nos sistemas e na forma de execução. A comparação da parametrização com a música nos permite vislumbrar a diferença na produção, já que o “musico é comprometido com o ensaio da performance”, sendo isso uma característica essencial da parametrização (WOODBURY, 2010, p. 24). Como exemplo conceitual é muito interessante, já que deixa evidente a diferença do papel da performance no processo de projeto como um norteador de decisões a serem tomados. As referências conceituais da produção arquitetônica moderna eram muitas vezes buscadas em artes plásticas, observando a ordem da composição que permitiram entender a forma, de maneira estática. A música como conceito para a parametrização, por sua vez trata a relação do ator com seu objeto e com o ambiente, sendo a performance o aspecto da temporalização da interação entre essas partes. Como a produção de música, a produção paramétrica trabalha com a ideia de encontros e caminhos, chamados nódulos e vetores, estabelece relações, no sentido de permitir comportamentos interativos de componentes de construção e sistemas (WOODBURY, 2010, p. 24).

Sendo o centro da parametrização a performance, focando no comportamento do que pretende ser projetado, são necessárias revisões nas referências e métodos, o que o ciberneticista Heinz von Foester previu já nos anos 1960 - ao invés de focar no projeto de um objeto mecânico, propor um sistema orgânico. Hugh Dubberly e Paul Pangaro destacam a relação entre métodos de projeto e cibernética, propostos por Horst Rittel e Heinz von Foerster, ambos nos anos 1960. Foerster descreve “a mudança de foco na Cibernética do mecanismo para linguagem e de sistemas observados (do exterior) para sistemas que observam (observando sistemas)” (DUBBERLY, 2008, p. 8).

Horst Rittel diferenciava duas ordens no processo de projeto: a Primeira Ordem enxerga o Processo de Projeto como optimização, resolução de problemas de forma linear. Decisões são baseadas em fatos. A Segunda Ordem define o processo de projeto com argumento, estruturado em objetivos, recebendo retornos múltiplos, as decisões sendo instrumentais. A atuação temporal da Primeira Ordem se encontra no presente e da Segunda, com seu caráter mais especulativo, no futuro (DUBBERLY, 2008, Idem). Ao comparar as duas ordens cibernéticas, vê-se que a Primeira Ordem entende o processo de projeto como um círculo único de ação, controlados ao longo do processo e regulados no ambiente. Trata-se de um sistema observado externamente, as decisões tentam ser objetivas. Já a Segunda Ordem trata o processo com um círculo duplo de oportunidades de aprendizagem e possibilidades de participação através da conversação. O sistema se observa, sendo os atores parte do sistema, permitindo a criação conjunta de objetivos. Decisões permitem subjetividade. (DUBBERLY, 2008, Idem).

Estabelecendo um paralelo entre os objetivos da revisão de ambos, da Primeira Ordem para a Segunda Ordem, percebemos uma clara relação dos objetivos da parametrização com os aspectos da Segunda Ordem, tanto do método de projeto como da cibernética, no que deverá levá-la além da procura da forma, reforçando a crítica da ideia reducionista de projeto de um objeto mecânico, cedendo lugar ao planejamento de um sistema orgânico, que responderá melhor aos anseios de um arquiteto que pensa no futuro.

No intuito de querer contribuir para uma maior compreensão do papel da cibernética para a implantação da parametrização como estratégia projetual, convida-se a observar três conceitos chaves da cibernética. Para entender os pilares fundantes do que estimula o desenvolvimento da parametrização e sua necessária inclusão plena na formação e prática profissional, se introduz primeiramente a cibernética formulada por Ross Ashby, como uma ciência formalizada de máquina ideal. Para incluir o aspecto sistêmico do objeto, é preciso conhecer a teoria viável de sistema proposto por Stafford Beer, que completa a compreensão entre objeto e ambiente. A cibernética, que tem no seu centro o Timoneiro como metáfora do indivíduo, deve ainda contribuir para reflexões sobre seu papel no processo e a interação entre partes, através da teoria da conversação, desenvolvido por Gilbert Simondon.

Ciência formalizada de Máquina Ideal

Um dos pilares fundantes da parametrização, que estabelece o início do desenvolvimento dos conceitos que a precedem, são as teorias de Ross Ashby expressas em seu livro "Design for a brain", publicado em 1952. Pela primeira vez, Ross Ashby descreveu o organismo como uma máquina. Considerando "[...] a técnica de aplicação deste pressuposto para as complexidades de sistemas biológicos [...]" (ASHBY, 1960, p. 30), ele se referiu à suposição de que o organismo vivo em sua própria natureza e processo não é diferente de nenhum outro assunto. Ashby identificou que o comportamento de um organismo é especificado pela sua variável assim que, "todos os movimentos corporais possam ser especificados por coordenadas" (ASHBY, 1960, p. 30).

Ashby estudou as ligações que envolvem o organismo e o meio ambiente, assim como a relação entre eles. A sua definição da homeostase é essencial para o mecanismo, e mostra claramente que ele pode proporcionar uma base ideal dividido em três itens:

(1) Cada mecanismo é adaptado ao seu fim. (2) O seu fim é a manutenção dos valores de algumas variáveis essenciais dentro dos limites fisiológicos. (3) Quase todo o funcionamento fisiológico de um animal é movido por esses mecanismos. (ASHBY, 1960, p. 58).

Para Ashby, a característica que define a "adaptação" é a relação de equilíbrio dinâmico com o mundo. O equilíbrio dinâmico é a característica fundamental da vida. Após esta hipótese, verificou-se que muitos organismos possuíam este mecanismo para interagir com o ambiente, baseando a formulação da teoria da máquina ideal em vista desses princípios. O exemplo do homeostato, elemento da máquina ideal, é um dispositivo eletromecânico, com quatro homeostases idênticos, todos interligados. Cada unidade homeostática é um dispositivo que converte impulsos elétricos em saídas elétricas. Ashby entendeu estas correntes como as variedades essenciais do homeostato. Com esta máquina, ele tentou conservar o sistema em um limite que fosse possível entender as variedades mais claramente. A definição de Homeostático é a relação entre a entrada e a saída, no qual as unidades podem operar sobre estas duas formas de acordo com a configuração (PICKERING, 2010, p. 101). Assim, Ashby conseguiu montar uma máquina ideal, que pode compreender o sistema operativo do cérebro humano. Esta máquina ideal é o resultado de vinte anos de trabalho e pesquisa de Ashby, e seu esforço transformou a Cibernética em uma ciência formal (PICKERING, 2010, p. 105).

Segundo o biólogo James Lovelock, a homeostase reúne a sabedoria do corpo em que ele mantém o estado constante, mesmo ocorrendo mudanças ambientais externas ou internas. Segundo ele, nos organismos vivos, a homeostase não é a constância permanente, mas o estágio de constância dinâmico. Um organismo vivo pode evitar o colapso e se mudar para um novo estágio de constância e começar com um novo limite sem falhar (LOVELOCK, 2006, p. 140).

Lovelock apropria-se da primeira definição de Cibernética ao exemplificar a homeostase, citando o timoneiro do navio em uma situação com tempestades e pedras no percurso, ajustando o navio para um novo caminho estável. Mesmo com a mudança da Cibernética de Primeira Ordem para a Segunda Ordem, o interesse continua a ser a compreensão do processo adaptativo.

Um exemplo de arquitetura que tem como objetivo a máquina ideal de Asbhy é a capsula que foi desenvolvida para ir à lua. Sua concepção foi um esforço conjunto de especialistas, imaginando um programa e funcionalidade sem nenhuma referência de projeto. Quando se procura inovação na área da arquitetura, não se parte de formas ou programas predefinidos, mas sim da tentativa de compreender comportamento e performance entre objeto, ambiente e o seu usuário. Podemos afirmar que o conceito da máquina ideal permitindo auto regulamento, adaptabilidade e revisão através de variáveis que surgem, são partes intrínsecas ao processo paramétrico, incluído em programas de simulação e verificação, acoplados aos programas.

Modelo do Sistema Viável

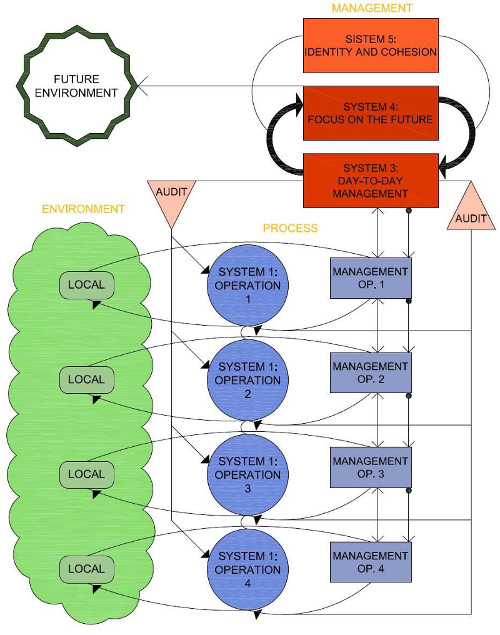

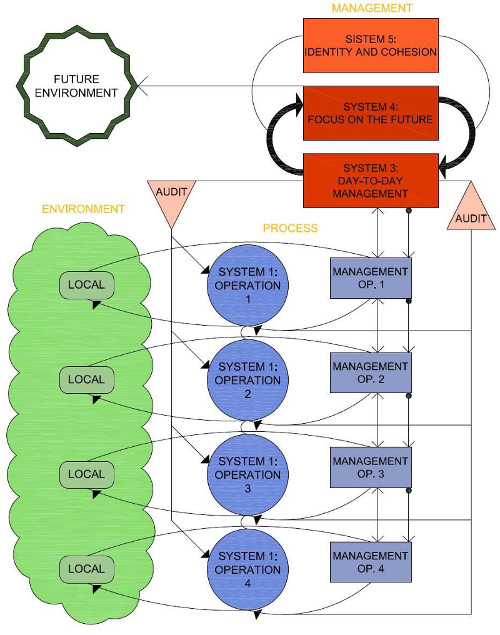

No intuito de complementar a relação do objeto e do ambiente, com caráter mais sistêmico e orgânico, tem um segundo aspecto cibernético, o Modelo do Sistema Viável (VSM, apresentado em 1972, no livro Brain of the Firm) do ciberneticista e administrador Stafford Beer. Parte da referência de um sistema nervoso para explicar os objetivos de um sistema viável, uma vez que é o sistema mais complexo do ponto de vista da engenharia de controle. A natureza trouxe o início do delineamento de seu projeto sobre a organização replicando os organismos biológicos como a estrutura para um sistema viável (PICKERING, 2010, p. 244). Para Beer, todos os sistemas viáveis contêm e estão contidos em um sistema viável. Para que o sistema seja viável, ele precisa ser dinâmico e complexo, e isso significa que o sistema muda constantemente. Ele amadurece as suas ideias e a sua explicação sobre o Modelo de Sistema Viável, tornando-o um método aplicável para empresas. Seu sistema foi estruturado através de cinco subsistemas, e que pode ser aplicada em todos os sistemas (Figura 1):

O Sistema Um é o sistema com as operações, significa que é o elemento de processo. O sistema possui, de forma direta, ligações com os seus usuários do ambiente. Além disso, o Sistema Um tem a sua própria gestão, que é responsável pela distribuição dos recursos internos (LEONARD; BEER, 1994, p. 47); Sistema Dois tem a função de harmonizar as atividades das operações no Sistema Um, ou em termos cibernéticos, reduz as oscilações da ligação de diferentes operações (LEONARD; BEER, 1994, p. 48); Sistema Três é responsável pela gerência do Sistema Um, de modo a coordenar para que as unidades não fiquem umas sobre as outras e para trazer mais eficácia para o sistema. O Sistema Três tem uma função de auditoria especial, podendo ser um procedimento interno ou externo, como um consultor externo (LEONARD; BEER, 1994, p. 48); Sistema Quatro está diretamente ligado com o meio ambiente, assim como o Sistema Um, olhando para o futuro hipotético de "próximo, médio e longo prazo" (LEONARD; BEER, 1994, p. 49); Sistema Cinco é a identidade de todo o sistema, e uma unidade de todos os sonhos dos membros que compõem o sistema (LEONARD; BEER, 1994, p. 50).

Figura 1. Modelo de Sistema Viável com os subsistemas 1-5 de Beer de 1994. Autor da imagem: Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi.

Beer define a cibernética como a ciência da organização efetiva. Cinco princípios organizadores norteiam o sistema viável, incluindo autonomia máxima individual combinado com a solidariedade e a subsidiariedade, cooperação e coordenação, incluindo não oscilação e amortecimento, execução e organização para sinergia, transparente e confiável; inteligência coletiva e planejamento estratégico; planejamento baseado na identificação com o propósito, à procura de valores em comum, princípios e visão.

Em relação à parametrização, desta vez visto como um modelo de organização de informação, um modelo único alimentado em tempo real, por diversos contribuintes da proposta, o VSM nos oferece princípios para observar, que avaliam e corrigem durante o ciclo de vida da intervenção, seja no caso da arquitetura de um edifício ou um planejamento urbano a partir de variáveis e inesperados desenvolvimentos, chamados ruídos, que podem surgir.

Adaptação e Inovação

O arquiteto inglês Cedric Price tinha o interessante hábito de predefinir a validade dos seus projetos, não somente pela durabilidade do material a ser usado e as questões econômicas, mas também pela funcionalidade da proposta dentro do sistema do ambiente. Ele dizia que não poderia garantir o bom funcionamento do prédio depois da sua data de vencimento, devendo portanto ser demolido. Para evitar permanentes demolições de edifícios e sistemas do habitat que se tornam obsoletos, a estratégia é defini-los como um objeto arquitetônico, não como um recipiente estático condenado a permanecer além do seu tempo útil. Acrescenta-se o conceito da máquina aberta que permite alterações para se adaptar ao ambiente em permanente mudança. Segundo o filósofo Gilbert Simondon:

A máquina que é dotada de uma alta tecnicidade é uma máquina aberta, o conjunto de máquinas abertas supõe o homem como organizador permanente, como intérprete vivo das máquinas umas em relação às outras. [...] É ainda por intermédio dessa margem de indeterminação e não por automatismos que as máquinas podem ser agrupadas em conjuntos coerentes, trocar informações umas com as outras por intermédio do coordenador que é o intérprete humano (SIMONDON, 1989, p. 11, tradução nossa).

Incluir o desafio de estruturar uma máquina ideal (ASHBY, 1960) de forma a ser parte da geografia onde se encontra (SIMONDON, 1989) dentro de um sistema viável (BEER, 1994), potencializa, na nossa opinião, a parametrização que assim penetra todo o ciclo de vida.

Falta ainda uma compreensão melhor do impacto da parametrização no modo de construir o habitat. Em 2009, o ciberneticista e arquiteto Ranulph Glanville, em uma conversa discordava sobre a relação da cibernética com parametrização. Ele tinha razão de não reconhecer essa relação naquele momento, no qual inúmeros exemplos iniciais de parametrização eram objetos estéticos, usando ferramentas computacionais, sem, portanto entender as mudanças estruturais e conceituais necessárias para desenvolver outra forma de organizar o habitat.

Agradecemos a Ranulph Glanville pelas conversas que estimularam este artigo. Agradecemos ao CNPq pelo apoio financeiro.

Referências

ASHBY, W. R. Design for a Brain: The origin of adaptive behaviuor. 2a ed. rev. London: Chapmann and Hall, 1960.

DUBBERLY, H. Design in the age of Biology. ACM, Interactions, v. XV.5, Set./Out.2008.

LEONARD, A., BEER, S. The systems perspective: methods and models for the future. AC/UNU Millennium Project, 1994.

LOVELOCK, J. Gaia: Cura para um planeta doente. Trad. Aleph Teruya Eichemberg, Newton Roberval Eichemberg. São Paulo: Cultrix, 2006.

PICKERING, The cybernetic brain: sketches of another future. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010.

SIMONDON, G. Du mode d’existence des objects techniques. Paris: Editions Aubier, 1989.

WOODBURY, R. Elements of Parametric Design. New York: Routledge, 2010.

How cybernetic is parametrization?

Anja Pratschke is Architect and PhD in Computer Science, Professor and researcher at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. She is Co-coordinator of Nomads.usp - Center of Interactive Living Studies, where she develops and supervises researches in Design Process and Communication in Architecture subjects.

Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi is Architect and Urbanist. She studies cyber aspects of architectural design processes at Nomads.usp - Center of Interactive Living Studies, of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

How to quote this text: Pratschke, A. and Di Stasi, M. G., 2015. How cybernetic is parametrization? V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 11. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus11/?sec=6&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 01 July 2025].

"And what takes the place of philosophy now?"

HEIDEGGER: Cybernetics. Interview for the magazine Der Spiegel, Germany, 1966.

Parametrization is being introduced for years in education and in architectural designs around the world. To be used in its full potential, it demands a revision from the actual focus in design of the form giving, still a central part of architectural design practice and education. According to Hugh Dubberly, the shift should be to concentrate on the process’ planning as a whole, establishing relations between object and environment, and actor who occupies both (Dubberly, 2008, p.9).

Parametrization isn’t new. Originally, it was born with the Sketchpad development, in 1963 by Ivan Sutherland, which was "a mechanism based on propagation and, at the same time, a simultaneous solver." (Woodbury, 2010). Parametric Design derives from the Graph Theory and, within that, from the propagation-based system, which assumes that the user organizes the graph, so that it can be directly solved. According to Robert Woodbury, this is the simplest type of parametric system, organizing objects so that the known information is based on unknown information. Knowing the theories behind the parametric design, the principles, advantages and fields of knowledge needed to master how to do it, which means, design with code, focusing on information management and its visibility in areas such as Building Information Modeling [BIM] and File to Factory, becomes a professional survival strategy in a competitive and international market based on expertise (Woodbury, 2010).

Going beyond the conventional way of adding and deleting design decisions, parametrization adds the ability to relate and modify parts of the project within the coordinated set, assuming that fundamental changes bring changes in the systems and in execution form. The comparison of parametrization with music allows us to glimpse the difference in the production, since the "musician is dedicated to rehearsing for performance", this being an essential feature also of parametrization (Woodbury, 2010, p.24). As a conceptual example, it is very interesting as it highlights the difference of the focus on the role of performance within the design process as a guideline for decision making. The conceptual references of modern architectural production were often sought in fine arts, observing the composition order that allowed the understanding of the form, in a static way. Music as a concept for parametrization is, in turn, the actor's relation to its object and the environment, and the performance is the aspect of temporality of interaction in between its parts. As music production, parametric production works with the idea of meetings and paths, called nodes and vectors, establishing relations, allowing an interactive behavior of building components and systems (Woodbury, 2010, p.24).

Being performance the center of parametrization, focusing on the behavior of what is intended to be projected, it includes necessary revisions of references and method, which the cybernetic Heinz von Foester had already predicted in the 1960s, proposing an organic system, instead of focusing on a mechanical object design. Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro highlight the relation between design and cybernetic methods, proposed by Horst Rittel and Heinz von Foerster, both in the 1960s. Foerster describes "the shift of focus in cybernetics from mechanism to language and from systems observed (from the outside) to systems-that observe (observing-systems)." (Dubberly, 2008, p.8).

Horst Rittel differentiated two orders in the design process: the First Order sees the design process as optimization, troubleshooting, linearly. Decisions are based on facts. The Second Order defines the design process with argument, structured in goals, receiving multiple returns, the decisions are instrumental. The temporal performance of the First Order is in the present; while the second, which is more speculative, is in the future (Dubberly, 2008, p.8). When comparing the two cybernetic orders, it is seen that the First Order understands the design process as a single circle of action, controls throughout the process and regulation in the environment. It is a system observed externally, decisions try to be objective. However, the Second Order is the process with a double circle of learning opportunities and the possibility of participating through conversation. The system observes itself, being the actors parts of the system, enabling the joint creation of goals. Decisions allow subjectivity (Dubberly, 2008, p.8).

Establishing a parallel between both the review’s goals, the First Order to the Second Order, we see a clear link between the parametric goals and the Second Order aspects of both the design method and cybernetics, which understanding should allow to go beyond the form search, reinforcing the criticism towards the reductionist idea of a mechanical object design, giving way to planning an organic system that will respond better to the yearnings of an architect who thinks in the future.

In order to contribute to a greater understanding of the cybernetic role on the implementation of parametrization as design strategy, you’re invited to observe three cybernetic key concepts. To understand the foundation pillars of what stimulates the parametrization development and the necessity of its full inclusion in education and professional practice, primarily the cybernetics formulated by Ross Ashby will be introduced, the formal science of an ideal machine. To include the object’s systemic aspect, the viable system theory proposed by Stafford Beer is of fundamental importance, which complements the understanding between object and environment. Cybernetics, which has at its center the Steerman as a metaphor for the individual, should also contribute to reflections on its role in the process and the interaction among parts, developed by Gilbert Simondon.

Formal Science of an Ideal Machine

One of the founding pillars of parametrization, that establish a start on the development of preceding concepts, are the theories of Ross Ashby expressed in his book "Design for a brain," published in 1952. For the first time, Ross Ashby described an organism as a machine. Considering the "[...] technique of applying this assumption to the complexities of biological systems [...]” (Ashby, 1960, p.30), he referred to the assumption that the living organism, in its own nature and process, is no different from no other subjects. Ashby identified that an organism behavior is specified by its variable, thus "all bodily movements can be specified by coordinates" (Ashby, 1960, p.30).

Ashby studied the connections involving the organism and the environment, such as the relation between them. His definition of the homeostasis is essential for the mechanism, and clearly shows the reason why it can provide an ideal base divided in three items:

(1) Each mechanism is ‘adapted ' to its end. (2) Its end is the maintenance of the values of some essential variables within physiological limits. (3) Almost all the behavior of an animal's vegetative system is due to such mechanisms. (Ashby, 1960, p.58).

For Ashby, the characteristic that defines the “adaptation” is the relation of dynamic balance with the world. The dynamic balance is the fundamental characteristic of life. After this hypothesis, it was found that many organisms possess this mechanism in order to interact with the environment, formulating his theory of the ideal machine based on this principles.The exemple of the Homeostat, an ideal machine element, is an electro mechanic device, with four identical homeostates, all of them interconnected. Each homeostat unit is a device that converts electrical inputs in electrical outputs. Ashby understood these currents as the essential varieties of the homeostat. With this machine, he tried to conserve the system in a limit in which he could clearly understand the varieties. The definition of homeostatic is the relation between the inputs and the outputs, in which the units can operate on these two forms according to the configuration (Pickering, 2010, p.101). Therefore, Ashby managed to assemble an ideal machine, which can comprehend the operating system of the human brain. This ideal machine was the result of twenty years of work and research by Ashby, which transformed Cybernetics to be a formal Science (Pickering, 2010, p.105).

According to the biologist James Lovelock the homeostasis gathers the body’s wisdom in which it maintains the constant state, even with external or internal environmental changes occurring. According to him, in the living organisms, the homeostasis isn’t the permanent constancy, but the dynamic constancy stage. A living organism can avoid the collapse and move to a new constancy stage and begin a new limit without fail (Lovelock, 2006, p.140).

Lovelock appropriates of one of the first definitions of cybernetic when he exemplifies the homeostasis, citing the steerman of the ship in a storm situation with rocks in its course adjusting the ship for a new stable path. Even with the change in the First Order Cybernetics to the Second Order, the interest continues to be the understanding of the adaptive process.

An example of architecture that has as its goal Ashby’s ideal machine is the capsule that was developed to go the moon. Its design was an effort of a group of experts, imagining a program and functionalities without any design reference. When looking for innovation in the field of architecture, you don’t start from form nor from predefined programs, but from the attempt of understanding behavior and performance between object and environment and its user. We can affirm that the ideal machine concept, allowing self-regulation, adaptability and review through variables that come up, is an intact part of the parametric process, including in simulation and verification programs, coupled to the programs.

Viable System Model

Aiming to supplement the relation between the object and the environment, with a more systemic and organic character, there is a second cybernetic aspect, the Viable System Model (VSM, shown in 1972, in the book “Brain of the Firm”) by the cybernetic and manager Stafford Beer. He starts with a reference to a nervous system to explain the viable system’s goals, once it is the most complex system in the universe and the most wonderful in control engineering’s point of view. Nature brought the beginning of the project’s design on organization, replicating the biological organisms as the viable system structure (Pickering, 2010, p.244). For Beer, all the viable systems contain and are contained in a viable system. For the system to be viable, it needs to be dynamic and complex, and that means the system changes constantly. Beer matures his ideas and his explanation about the Viable System Model, making it an applicable method for business companies. His system was structured through five subsystems, which can be applicable in all other systems (Figure 1).

The First System is the operation; it means that it is the process element. The system has, directly, links to its environment users. Besides that, the First System has its own management, which is responsible for internal resources distribution (Leonard and Beer, 1994, p.47); System Two has the function to harmonize the activities in the First System operations, or in cybernetic terms, it reduces the oscillation of different operations’ links (Leonard and Beer, 1994, p.48); System Three is responsible for the First System’s management, as to coordinate the units so they don’t fall over each other and to bring more effectiveness to the system. System Three has a special audit function which can be an internal or external procedure, such as an external consultant (Leonard and Beer, 1994, p.48); System Four is directly connected to the environment, as well as the First System, looking at the hypothetic future of “near, mid and long term” (Leonard and Beer, 1994, p.49); System Five is the identity of the entire system, and a unit of all the dreams of the members that compose the system (Leonard and Beer, 1994, p.50).

Figure 1. Viable System Model with the subsystems 1-5 from Beer, 1994. Author of the image: Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi.

Beer defines cybernetics as the science of effective organization. Five organizing principles guide the viable system, including maximum individual autonomy tempered by solidarity and subsidiarity, cooperation and coordination, including non-oscillation and damping, execution and organization for synergy, transparent and reliable; collective intelligence and strategic planning; planning based on identification with the purpose, looking for common values, principles and vision.

In relation to parametrization, this time seen as a model of information organization, a single model, fed in real time by various contributors to the proposal, the VSM offers us principles for observing, that evaluate and correct during the intervention’s lifecycle, either in the case of a building architecture or in urban planning starting from variables and unexpected outcomes, called as noises that can arise. Adaptation and Innovation

Adaptation and Innovation

The English architect Cedric Price had the interesting habit of presetting the expiration date of his projects, not only by the durability of the material to be used, the economic issues, but by the functionality of the proposal within the environment system. He said he could not guarantee the proper functioning of the building after its due date and it should be demolished. To prevent permanent demolition of buildings and habitat systems that become obsolete, the strategy is to define the architectural object, not as a static container doomed to remain beyond its useful time. Enters the concept of the open machine that allows changes, in order to adapt to the environment in permanent change. According to the philosopher Gilbert Simondon:

The machine that is equipped with a high tenacity is an open machine, the set of open machines presupposes the man as the permanent organizer, as a living interpreter of a machinery in respect of others. [...] It is also through this margin of uncertainty and not by automations that the machines can be grouped into coherent sets, exchange information with each other via the coordinator that is the human interpreter" (Simondon, 1989, p.11, our translation).

Including the challenge of designing an ideal machine (Ashby, 1960) in order to be part of the geography (Simondon, 1989), within a viable system (Beer, 1994), enhances, in our opinion, the parametrization that permeates the entire life cycle.

A better understanding of the parametrization impact so as to build the habitat is still lacking. In 2009, the cyberneticist and architect Ranulph Glanville, disagreed with me in a conversation about the relation of cybernetics with parametrization. He was right not to recognize this relation at this time in which numerous examples of initial parametrization were aesthetic objects by using computational tools without, therefore, understanding the structural and conceptual changes needed to develop another way of organizing the habitat.

Thanks to Ranulph Glanville for the conversations that stimulated this paper. Thanks to CNPq for financial support.

References

Ashby, W.R., 1960. Design for a Brain: The origin of adaptive behaviuor. London: Chapmann and Hall, Second Edition Revised.

Dubberly, H., 2008. Design in the age of Biology. ACM- Interactions, v. XV.5.

Leonard, A. and Beer, S., 1994. The systems perspective: methods and models for the future. AC/UNU Millennium Project.

Lovelock, J., 2006. Gaia: Cura para um planeta doente. São Paulo: Cultrix.

Pickering, A., 2010. The cybernetic brain: sketches of another future. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Simondon, G., 1989. Du mode d’existence des objects techniques. Paris: Editions Aubier.

Woodbury, R., 2010. Elements of Parametric Design. New York: Routledge.