A estética de dados e o papel da narração em artefatos generativos

Luiz Gustavo Ferreira Zanotello é Designer e pesquisador em Meios Digitais na Hochschule für Künste Bremen. Suas pesquisas abordam temas como artemídia, transdisciplinaridade e processos experimentais em linguagens contemporâneas digitais.

Como citar esse texto: ZANOTELLO, L. G. F. Data aesthetics: a estéticas de dados e o papel da narração em artefatos generativos. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 11, 2015. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus11/index.php?sec=4&item=3&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 18 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Artefatos generativos baseados em dados são objetos que, através de algoritmos generativos, contém um ou mais aspectos formais parametrizados por dados. Apesar de definidos pelos métodos dos quais dados são traduzidos em estética, dentro de suas caixas-pretas, tais artefatos incorporam diferentes actantes numa rede de diferentes translações que em conjunto, constituem uma narrativa. Conduzido por conceitos da teoria ator-rede de Bruno Latour, bem como a ontologia orientada aos objetos como proposta por Graham Harman, este ensaio discute os diferentes aspectos narrativos inerentes aos artefatos generativos, e explora o papel de tais aspectos como evidências de uma especulação ontológica característica destes artefatos.

Palavras-chave: parametrização, dados, narração, generativo, especulação.

1. Introdução

Tecnologias amplamente difundidas e acessíveis são atualmente capazes de extrair dados científicos de objetos de sistemas tanto naturais quanto artificiais. Enquanto isso, a crescente intersecção entre a Arte, Ciência, e Tecnologia, tem dado espaço para novas formas de admiração, como a arte generativa. Apesar da prática de geração de obras de arte através do uso de de sistemas computacionais autônomos existir há mais de cinquenta anos1, a atividade artística de análise de dados, para dar forma a obras de arte, tem somente nos últimos dez anos ganhado corpo e prominência em ambos mundos, da Mídia Arte e Design Contemporâneo, incitando, assim, atenção à seus métodos e discursos.

É através da manobra de parametrização, o processo de atribuir parâmetros variáveis que alteram o comportamento de um sistema, que artefatos generativos são capazes de incorporar em sua composição dados coletados por dispositivos tecnológicos. Em seu início, os parâmetros contidos em algoritmos de obras de arte generativa funcionavam através do princípio da randomização, ao conter variáveis que incorporavam esquemas estatísticos que influenciavam a arte final gerada pelo sistema. Hoje, algoritmos paramétricos frequentemente recebem a entrada de dados vindos de um sistema terceiro que traduz dados analógicos para dados digitais.

Em certos momentos correndo o risco de mera estetização, ao passo que em outros uma "visualização" de conjuntos de dados em formas perceptíveis, obras de arte geradas por algoritmos com a entrada de dados são comumente concebidos como uma mera interação entre o objeto de onde os dados são coletados, o artista que desenvolve o algoritmo generativo, e a obra final gerada que toma os dados coletados para construir sua forma. Porém, dentro da caixa-preta2 de tais artefatos, uma miríade de diferentes actantes entram em jogo para compôr a obra final. Há o artista que escolhe associar um objeto em questão com uma forma específica, há o dispositivo computacional que processa o algoritmo escrito pelo artista, há o dispositivo tecnológico que extrai dados analógicos do objeto inicial, há a máquina de impressão ou visualização da obra gerada, e há os próprios dados digitais. Este coletivo formado por tantos diferentes atores entram num jogo narrativo, onde a obra de arte é menos concebida por sua forma ou até os dados analógicos em que foi baseada, do que é pela estória de associações da qual é constituída. Poderia a narrativa inscrita entre estes actantes ser o próprio material central de artefatos generativos baseados em dados?

1.1 Um primeiro exemplo

Em Cosmos, a dupla de artistas Semiconductor criou uma escultura de madeira a partir de medições dos níveis de dióxido de carbono da Alice Holt Forest no Reino Unido, e colocou esta mesma escultura posteriormente na mesma floresta onde tais dados foram colados, como se retornando os "dados" para seu habitat original. A descrição da obra, retirada da página online dos artistas segue:

Cosmos é uma escultura esférica de dois metros que foi formada por dados científicos tornados tangíveis. Interessados na divisão entre como a Ciência representa o mundo físico e como nós o experienciamos, Semiconductor tomou dados científicos como sendo uma representação da natureza e estão explorando como nós podemos fisicamente nos relacionar a eles. Localizado em Forestry Commissions Alice Holt Forest, Reino Unido, a escultura é feita de um ano de medições do ganho e perda de dióxido de carbono das árvores da floresta, coletadas do topo de uma torre de alto fluxo de vinte e oito metros localizada nas proximidades em Alice Holt Research Forest. Para revelar os padrões visuais e formas inerentes nos dados, Semiconductor desenvolveu técnicas digitais personalizadas para traduzir os dados de linhas de números em formas tridimensionais. O resultado é uma interferência complexa de padrões produzidos pelas formas de onda e padrões presentes nos dados. Através deste processo de recontextualização dos dados, ela se torna abstrata em forma e significado, adquirindo propriedades esculturais. Estas formas esculturais tornam-se ilegíveis dentro do contexto da Ciência, porém se tornam uma forma física que podemos ver, tocar, experienciar e ler numa nova maneira. Aqui, humanizar os dados oferece uma nova perspectiva do mundo natural que eles documentam. A definição de Cosmos é um completo, ordenado, e harmonioso sistema e aqui se refere às fontes dos dados combinados que trabalham em armonia para tornar a floresta o que ela é.3 (SEMICONDUCTOR, 2012)

Cosmos não questiona nem os dados científicos nem o fenômeno que a escultura representa. Pelo contrário, a escultura toma dados científicos como uma representação da natureza, e explora as possibilidades estéticas que a representação científica de fenômenos naturais carrega: como retirar as linhas de números coletados por aparatos tecnológicos para longe do discurso científico, em direção à um discurso palpável, estético, escultural? Cosmos se refere a dados científicios e possibilidades estéticas inscritas nos dados coletados, porém, a escultura não transforma dados científicos em conhecimento científico tampouco num entendimento científico do fenômeno que a escultura representa. Como um material cru, destacado do conhecimento científico original de que fez parte, os dados atuam somente numa dimensão estética na escultura, vagamente relacionados às variações do fenômeno em si.

Contudo, a escultura não incorpora somente dados: incorpora também a narrativa, uma estória de simulação. O aspecto narrativo da escultura-artefato está apenas vagamente associada à micro-forma que seu algoritmo generativo traduz dos dados captados. Este aspecto se levanta pelo estória embutida: uma esfera negra feita de um ano de dados de dióxido de carbono, que senta na mesma floresta em que foi retirada. Ele se levanta pelo vídeo que documenta e narra a história destes dados, bem como todos os atores que fazem parte dela. Ela se levanta pela tradução do fenômeno "dióxido de carbono" em dados analógicos pela torre de alto fluxo de vinte e oito metros de altura localizada numa floresta vizinha, pela tradução dos dados analógicos para dados digitais por um dispositivo tecnológico, pelo algoritmo digital que traduz estes dados numa forma tridimensional, pela tradução do arquivo digital em objeto tangível, e por último, pela tradução do objeto-escultura numa obra de arte.

Dados, em Cosmos, é um elemento de encenação dentro de um enredo de tradução. Cosmos traz aos sentidos menos a visualização de cada ponto de dado, e mais o próprio fato de que este dado existiu - ou a estória de que pode ter existido. O conhecimento que Cosmos produz não carrega um entendimento profundo do fenômeno que representa. Porém a obra pode criar a idéia de um terceiro, um novo objeto, uma escultura nascida menos pelos dados científicos e fenômenos naturais, e mais por sua estória especulativa: a estória dos dados científicos de dióxido de carbono que formam uma esfera negra dentro da floresta, tornando a floresta mais próxima de si mesma.

Como Bruno Latour escreve sobre os significados da mediação técnica: “as técnicas modificam a matéria de nossa expressão, não apenas sua forma” (LATOUR, 1999, p.185)4. Como a tradução técnica de objetos modifica a própria matéria da obra gerada? Poderia esta distância entre o fenômeno natural e o design da escultura, um com uma narração indivisível de actantes consecutivos de tradução, ser uma evidência da natureza especulativa deste artefato? Seria a coleta de dados de dióxido de carbono já uma forma de especulação performada pela antena?

2. Abrindo a caixa-preta de artefatos generativos

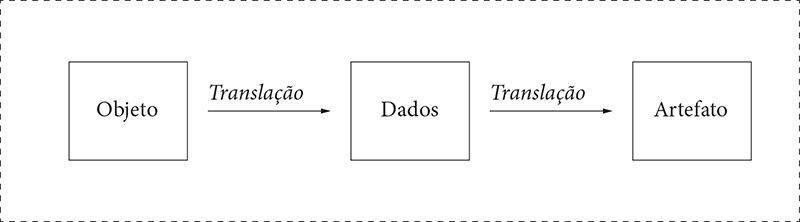

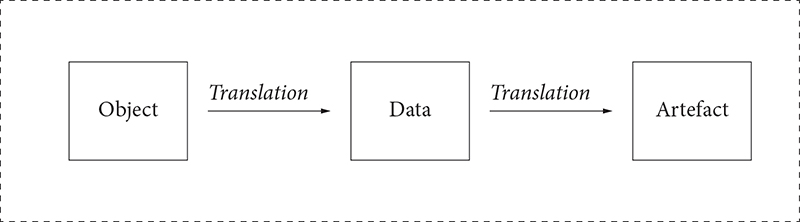

Obscurecimento ("Caixa-Preta"), como Latour concebe, é “a maneira em que trabalho científico e técnico é feito invisível por seu próprio sucesso” (LATOUR, 1999, p. 304)5. Ele continua e afirma que “quando uma máquina funciona eficientemente, quando uma matéria de fato é liquidada, é preciso focar somente nas entradas e saídas, e não em sua complexidade interna” (LATOUR, 1999, p. 304)6. Em uma maneira análoga linear, o seguinte gráfico aponta para três caixas-pretas que constituem os sistemas dos artefatos generativos:

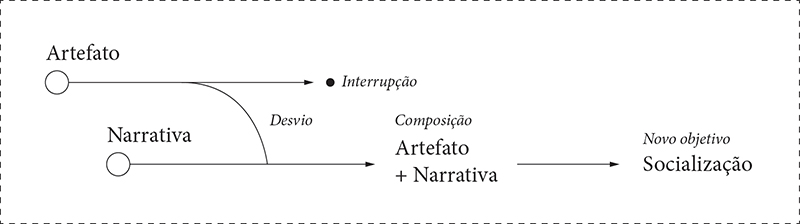

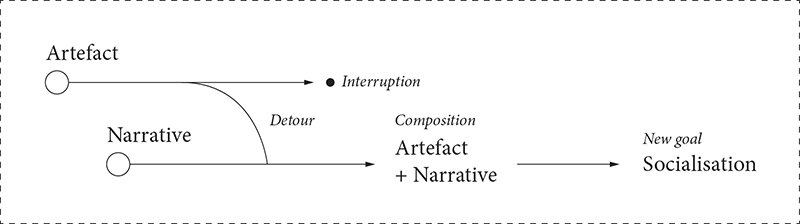

Figura 1. Primeiro nível de abertura da caixa-preta de um artefato generativo.

Em comparação ao termo "tradução", Latour concebe o termo "translação" como segue: "translação não significa passagem de um vocabulário a outro, de uma palavra francesa a urna palavra inglesa (como se, por exemplo, as duas línguas existirem independentemente). Empreguei translação para indicar deslocamento, tendência, invenção, mediação, criação de um vínculo que não existia e que, até certo ponto, modifica os dois originais." (LATOUR, 2001, p. 206).

Além de apontar as três principais caixas-pretas, esta primeira camada de compreensão já aponta à duas importantes translações que ocorrem durante o processo de emergência do Artefato. Um Objeto escolhido (luz, tráfego, temperatura, árvore) possui um certo aspecto que se desloca num conjunto de números discretos (Dados). Em segunda etapa, os Dados se deslocam numa nova mídia (uma escultura, um som, um vídeo, uma mesa). Este gráfico expõe a narração linear destes artefatos, um conto de seu desenvolvimento técnico que também serve como uma descrição geral da obra. Para se entender os actantes em translação dentro da caixa-preta destes artefatos e sua ação recíproca com os aspectos narrativos da obra, mais caixas-preta devem ser abertas numa cadeia mais complexa de translações.

2.1 A rede do artefato

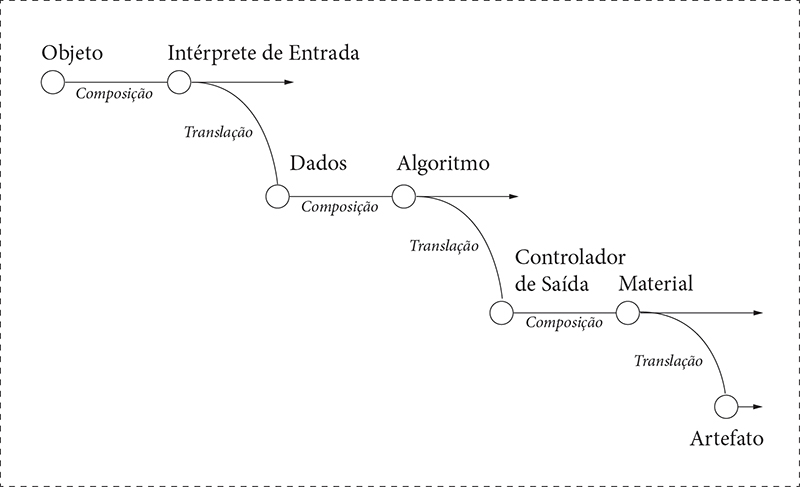

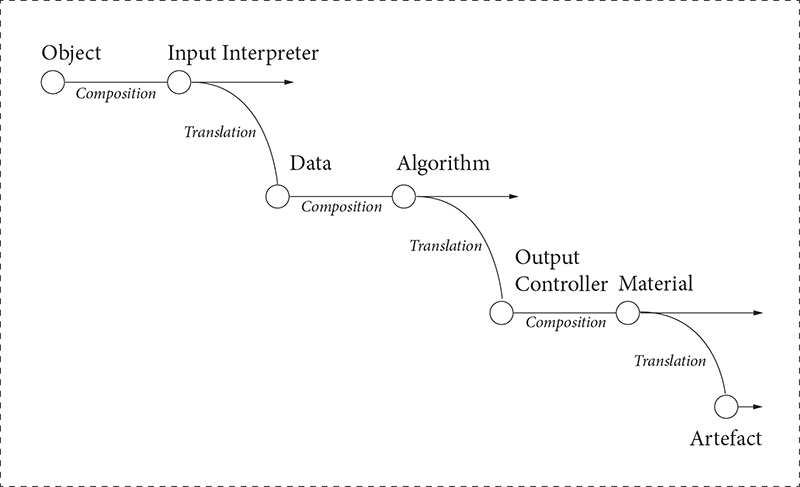

Figura 2. A rede de translações dos artefatos generativos.

O diagrama acima (Fig. 2.2) retrata a rede-chave de translações necessárias para que os artefatos generativos sejam materializados. Esta abertura quebra a relação anteriormente analisada entre o objeto, os dados e o artefato, em uma mediação técnica entre ainda mais atuantes que efetuam principalmente uma translação sucessiva do objeto inicial para o artefato final. O ponto chave dessa rede é, no entanto, os processos de translação que estão acontecendo no meio. Não seriam as propriedades materiais de tal artefato menos informadas por seus dados do que é pelo sensor (intérprete de entrada) que os coletaram?

O diagrama dismistifica a ficção potencial de que obras generativas são somente informadas por dados e algoritmos. Ainda mais, todo e qualquer actante acima descrito pode ter novamente sua caixa-preta aberta, revelando assim sucessivas correntes de translação, que não são menos constitutivas do artefato final, apesar de possivelmente exercerem uma influência menor em sua forma. Está claro, que a matéria que informa o arfetato é a própria mediação técnica entre os actantes da corrente acima.

Nesta corrente intrincada de eventos, uma mudança substancial aos actantes influenciaria toda a corrente em diversas maneiras, até em seus objetivos. O objetivo do Objeto não é o mesmo quando este é associado ao Intérprete de Entrada. Cada associação entre um ou mais actantes em um movimento de translação é sempre simétrico: o Objeto, o Intérprete de Entrada, os Dados, o Algoritmo, o Controlador de Saída, e o Artefato são todos simetricamente co-modificados durante o processo. Qual poderiam ser seus novos objetivos? Um momento de especulação é então desdobrado, um que é acessível através dos aspectos narrativos do Artefato.

2.2 Narrativa como actante

Todo artefato tem o seu script, seu potencial para agarrar os passantes e obrigá-los a desempenhar um papel em sua história (LATOUR, 2001, p. 204).

A narrativa é o objeto do ato de narração. Como a memória humana é invariavelmente histórica, narrativas são tropos de comunicação, objetos que servem como um meio de socialização. Novamente como Latour afirma, "ciência e tecnologia são aquilo que socializa não-humanos para que travem relações humanas" (LATOUR, 2001, p. 222). São pelos aspectos narrativos do Artefato, um objeto constituinte de actantes técnico-científicos, que humanos e não-humanos são conectados em corrente. O Artefato é resultado comum de uma série de translações, mas um que expõe seus próprios actantes constituintes para a socialização humana. Os aspectos narrativos são os "fantamas" durante o processo de criação do Artefato, mas também são as "conchas" que mantém seus actantes precedentes acessíveis a humanos. Mas não seriam estes mesmos aspectos inscritos no Artefato, um novo actante na corrente precedente?

Figura 3. Composição da socialização de artefatos generativos.

As propriedades do Artefato, suas qualidades materiais, sua forma, sua cor, textura, cheiro, movimento, som, configuração espacial, em si só, não são suficientes para abrir a caixa-preta e expôr a rede anterior aos humanos: as propriedades podem somente aludir a uma narração. Uma narração de sua própria montagem. Portanto a Narrativa, seja ela comunicada através de alusões formais ou palavras, é o elemento chave que faz a socialização de seus actantes possível. É a Narrativa que conta a história das manobras tecnológicas necessárias para o desenvolvimento do Artefato, uma narrativa que conta os procedimentos de delegação que levam à sua própria constituição. É a Narrativa que conta que uma particular curva do Artefato é associada com os movimentos de onda de um tsunami localizado no Pacífico, ou que o mar tem sua rede o Artefato como um modo de socializar-se com humanos. É a Narrativa o actante que torna possível a obra generativa tornar-se mais do que uma mera aestetização de dados, nem tampouco um arranjo randômico de entradas e saídas de objetos processados por um algoritmo invisível7.

A Narrativa é portanto o actante que modifica todos os actantes precedentes a trabalhar, em coerência, em direção à um novo objetivo. Como já descrito anteriormente na análise da escultura Cosmos, o artefato gerado é percebido menos por seus actantes constituintes, do que o é pela Narrativa que os envolve num único, coerente, terceiro objeto. É este objeto que é aberto ao acesso exterior, aquele que é aberto a um realismo especulativo.

3. O momento especulativo

A artista, em sua tentativa de alcançar e visualizar a realidade de um objeto, maravilha-se com sua forma pelas evidências de existência que pode encontrar. Um interpretador externo, um dispositivo técnico de captura de dados, captura detalhes e quantidades de um objeto, próximo a ele, qualidades invisíveis à artista por outros modos. O coletivo formado pela artista em adição à seus delegados técnicos, maravilha-se com as formas das quantidades recuperadas: uma possível forma de um terceiro objeto, um que é mais do que os dados coletados, e mais do que as qualidades percebidas. Shaviro diz sobre a ontologia dos objetos de Graham Harman: “precisamente porque nós não podemos conhecer as coisas em si mesmas, a única coisa que nos resta é especular. Nós não pegar objetos cognitivamente; mas podemos aludir a objetos através de metáforas e outras práticas estéticas”8.

A especulação em artefatos generativos baseados em dados ocorre na tentativa de alcançar a realidade interior de um objeto através de uma associação entre um encanto científico e estético. A especulação é extendida a delegados técnicos que coletam e processam dados retirados de um objeto. A rede de translações inerentes ao desenvolvimento do artefato evidencia ainda mais sua natureza especulativa. Um esforço carregado por um grau de incerteza e distância ao objeto a cada manobra de translação, especificamente aquela performada pelo algoritmo: o actante que torna em forma as quantidades extraídas do objeto. A forma emergida portanto não é uma forma que “é”: mas sim uma forma que “poderia ser”.

3.1 Dados como evidência

Nossa terceira mesa emerge como algo distinto de seus próprios componentes e que também se retira para trás de seus efeitos externos. Nossa mesa é um ser intermediário não encontrando na física subatômica, tampouco na psicologia humana, mas num zona autônoma permanente onde objetos são simplesmente si mesmos9. (HARMAN, 2012, p. 10)

Numa trama onde o objeto sempre se retira para atrás de seus efeitos externos, o papel que os dados têm precisa ser analisado. Por vezes descrito como dados científicos, dados coletados através de dispositivos técnicos realizam procedimentos científicos de medição, como numa tentativa de alcançar um aspecto invisível de um objeto. Escapando de ser uma representação 1:1 de um objeto, os dados em si são resultado de uma translação de mídias, uma que é performada sobre um aspecto tecnicamente sensível de um objeto. Seu potencial se encontra no rastreio do tempo entre quantidades mensuráveis, um conjunto de dados plotados com uma trama: a narração de um efeito exterior de um objeto no tempo.

Como traços externos quantificados de um objeto, os Dados assumem um papel de evidência na narrativa inscrita no artefato. Quando até os efeitos externos de um objeto são inacessíveis a humanos, os dados são a evidência-chave da existência de um objeto, uma evidência que é narrada por sua influência na forma do Artefato. O intérprete de entrada assume nesta trama o papel de uma "sonda" (BOGOST, 2012), um explorador de uma "realidade estrangeira" plotando efeitos apreensíveis para a forma de números. O intérprete determina as qualidades estéticas chave dos dados, qualidades não diretamente ligadas aos efeitos do objeto sentido (resolução, ruído, escala). Neste sentido, a evidência contida nos dados é sempre mediada e sempre sujeita à uma forma de translação. Portanto dados são evidências não somente da existência de um objeto no tempo, mas do sempre oblíquo e parcial acesso a um objeto: uma evidência da especulação realizada em conjunto pela artista e pelo algoritmo para gerar o artefato.

3.2 Manobra estética

O trabalho da artista Nathalie Miebach explora o papel da estética visual na translação de dados científicos. Ela questiona a tradicional visualização de dados realizada pela ciência, ao assumir os dados como matéria crua para raciocínio estético. Ao reunir dados do meio-ambiente por meio de dispositivos técnicos caseiros simples, Miebach traduz os números em estruturas tecidas meticulosamente sem computadores, porém ainda de maneira algoritmica. Em "Artic Sun - Solar Exploration Device for the Artic" (MIEBACH, 2006), a artista registrou com dispositivos técnicos a influência gravitacional de ambos sol e lua no Ártico por dois dias, em conjunto com as mudanças de maré, fases da lua, e caminho do sol durante o período. Cada tipo de elemento na escultura gerada é informada por uma das camadas de dados, que em conjunto compõem uma narrativa sobre dois dias dentro do meio-ambiente do Ártico.

Tomando dados como evidência, a artista é confrontada com a tarefa de elaborar um processo de translação de dados em formas capazes de contar uma estória de existência de um objeto. É um esforço especulativo, contanto que haja uma tentativa de estabelecer um artefato que "alude à um objeto que não pode exatamente ser feito presente"10. (HARMAN, 2012, p. 14). É também um esforço especulativo a formação de estórias através dos dados, bem como a de translação das narrativas emergentes em formas de significado. O artefato generativo, em si mesmo, envolve todos os actantes generativos numa sinfonia de metáforas: metáforas da existência de um objeto no tempo, uma que não pode ser completamente tocada por outros meios. O artefato neste sentido é um protótipo narrativo de dados.

Como Shaviro (2014, p. 44)11 afirma: "a realidade é muito mais estranha do que somos capazes de imaginar". O artefato generativo tenta, com sua associação de mídias técnicas, abrir as portas para a estranheza da realidade dos objetos. Ao ser transparente aos dados que informa e ao objeto do qual os dados foram coletados, o artefato é capaz de narrar a existência do objeto ao qual alude. Porém sempre como um terceiro, um objeto diferente daquele humanamente tocável, ou cientificamente evidenciado. Portanto, o artefato generativo propõe um raciocínio ontológico acerca do que o objeto pode ser, ao tornar perceptíveis seus efeitos humanamente imperceptíveis, e por escapar de uma direta translação de sua existência física. Ele propõe narrativas significativas de um objeto imperceptível, comunicado pela estória de seu próprio desenvolvimento inscrita em sua estética generativa.

4. Conclusão

Realismo Especulativo insiste sobre a independência do mundo, e das coisas no mundo, de nossas próprias conceitualizações sobre elas12 (SHAVIRO, 2014, p. 44).

Arte generativa baseada em dados, apesar de não comumente ligada à virada contemporânea filosófica do Realismo Especulativo, pode ser uma prática diretamente ligada às suas racionalizações. A delegação a actantes não-humanos, a translação de um efeito de um objeto a dados científicos e posteriormente a uma forma perceptível, e por último, a narração dos passos realizados de translação, são as maiores evidências do ato especulativo inerente à este tipo de prática artística. Artefatos gerados de forma algorítmica pela entrada de dados científicos são independentes de nossas próprias conceitualizações, bem como da fisicalidade do objeto de onde se coletam dados. Artistas e dispositivos técnicos especulam em conjunto em direção à formação de um terceiro objeto, nascido de procedimentos técnico-científicos e os efeitos externos de um objeto.

É somente através da narração que estes tipos de artefatos cumprem a tarefa de raciocínio ontológico. Os aspectos narrativos destes artefatos são os fatores chave que envolvem o artefato em ambas intrínsecas e extrínsicas composições. É primeiro, uma narração de sua própria constituição, uma estória técnica da série de translações e actantes que levaram à emergência do artefato. É esta narrativa a que inscreve o artefato num processo de socialização para ambos atores humanos e não-humanos, bem como é a evidência da associação do artefato aos objetos que ele prescreve. E é segundo, uma narrativa de dados. É esta segunda narrativa que serve como evidência da existência de um objeto, promovendo assim a manobra especulativa de uma definição ontológica do que o objeto poderia ser, pela translação de dados em forma.

Ambas narrativas combinadas podem estar inscritas na forma do artefato, ou anexado à ele por outras maneiras. Ambas formam, porém, um material necessário para a especulação ontológica que os artefatos generativos são capazes. É preciso precisão nas manobras de translação no ofício de tal especulação, pois os artefatos beiram o risco de estetização formulaica e vagueza de significado. A tarefa do artista é portanto criar de maneira coerente os algoritmos de translação, e escolher precisamente os actantes de translação que podem, no final, desempenhar seus papéis na trama especulativa de um artefato capaz de suspender a descrença de um terceiro objeto que não pode exatamente ser feito presente.

Referências

BOGOST, I. Alien Phenomenology, Or, What It’s Like to be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

CAMPBELL, J. Delusions of Dialogue: Control and Choice in Interactive Art. Leonardo, v. 33, n. 2, p.133-136, 2000.

HARMAN, G. The third table. Documenta (13): 100 Notes - 100 Thoughts / 100 Notizen - 100 Gedanken, v.85. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012.

LATOUR, B. Pandora’s Hope. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

LATOUR, B. A esperança de Pandora: ensaios sobre a realidade dos estudos científicos. Trad. Gilson César Cardoso de Sousa. Bauru, SP: EDUSC, 2001.

MIEBACH, N. Arctic Sun: Solar Exploration Device for the Arctic. Disponível em: SEMICONDUCTOR. Cosmos. 2012. Disponível em: SHAVIRO, S. Speculative Realism: A Primer. In: SHAVIRO, S. Spekulation, Text zur Kunst. [s.l.]: [s.n.], 2014, p. 40-52. 1 A primeira exposição de arte generativa, entitulada "Generative Computergrafik", que contou com obras de Georg Nees, ocorreu na Alemanha em 1965. 2 O termo "dentro da caixa-preta" tem como objetivo ilustrar o contrário do processo “blackboxing", como concebido por Bruno Latour (1999). 3 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'Cosmos is a two metre spherical wooden sculpture that has been formed from scientific data made tangible. Interested in the divide between how science represents the physical world and how we experience it, Semiconductor have taken scientific data as being a representation of nature and are exploring how we can physically relate to it. Located in the Forestry Commissions Alice Holt Forest, U.K., the sculpture is made from one year’s worth of measurements of the take up and loss of carbon dioxide from the forest trees, collected from the top of a 28m high flux tower located nearby in Alice Holt Research Forest. To reveal the visual patterns and shapes inherent in the data, Semiconductor developed custom digital techniques to translate the data from strings of numbers into three-dimensional forms. The result is complex interference patterns produced by the waveforms and patterns in the data. Through this process of re-contextualising the data it has becomes abstract in form and meaning, taking on sculptural properties. These sculptural forms become unreadable within the context of science, yet become a physical form we can see, touch, experience and readable in a new way. Here, humanising the data offers a new perspective of the natural world it is documenting. The definition of cosmos is a complete, orderly, harmonious system and here refers to the sources of the combined data which work in harmony to make the forest what it is.' (SEMICONDUCTOR, 2012) 4 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'techniques modify the matter of our expression, not only its form' (LATOUR, 1999, p.185) 5 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'the way scientific and technical work is made invisible by its own success' (LATOUR, 1999, p. 304) 6 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'when a machine runs efficiently, when a matter of fact is settled, one need focus only on its inputs and outputs and not on its internal complexity' (LATOUR, 1999, p. 304) 7 Referência à fórmula para arte computacional de Jim Campbell (2000). Campbell constitui uma crítica a arte computacional, expondo o risco desta arte se tornar uma formulaica aestetização de dados. A fórmula não leva em conta, porém, os aspectos narrativos de obras computacionais generativas, aspectos que se bem trabalhados, são capazes de abrir a caixa-preta deste tipo de arte e retirar a invisibilidade dos processos das quais é desenvolvida. 8 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: '(…) precisely because we cannot know things in themselves, the only thing that is left to us is to speculate. We cannot grasp objects cognitively; but we can allude to objects through metaphor and other aesthetic practices.' (SHAVIRO, 2014, p. 48) 9 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'Our third table emerges as something distinct from its own components and also withdraws behind all its external effects. Our table is an intermediate being found neither in subatomic physics nor in human psychology, but in a permanent autonomous zone where objects are simply themselves.' (HARMAN, 2012, p. 10) 10 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'alludes to an object that cannot quite be made present' (HARMAN, 2012, p. 14) 11 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'reality is far weirder than we are able to imagine' (SHAVIRO, 2014, p. 44). 12 Tradução livre do autor. Versão original: 'Speculative Realism insists upon the independence of the world, and of things in the world, from our own conceptualisations of them.' (SHAVIRO, 2014, p. 44).

Data aesthetics and the role of narration in generative artefacts

Luiz Gustavo Ferreira Zanotello is a Designer and researcher at the Digital Media program in the Hochschule für Künste Bremen. His research covers topics such as media art, speculative design, transdisciplinarity and experimental processes in digital contemporary languages.

How to quote this text: Zanotello, L.G.F., 2015. Data aesthetics and the role of narration in generative artefacts. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 11. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus11/index.php?sec=4&item=3&lang=en>. [Accessed: 18 July 2025].

Abstract

Data-based generative artefacts are objects that, by the means of generative algorithms, have one or more formal aspects parameterized by data. Although defined by the methods from which data is translated into aesthetics, inside their black-boxes, these artefacts incorporate different actants in a network of different translations that altogether, constitute a narrative. Driven by concepts taken from the actor-network theory of Bruno Latour, as well as the object-oriented-ontology as proposed by Graham Harman, this essay explores the different narrative aspects inherent to generative artefacts, and further explores the role of these narrational aspects as evidences of an ontological speculation inherent to such objects.

Keywords: parametrization, data, narration, generative, speculation.

1. Introduction

Widespread easily accessible technologies are currently able to extract scientific data from objects of both natural and artificial systems. Meanwhile, the growing intersection between the arts, the sciences, and technology, has been giving space to new forms of wonder, generative art being among them. Although the practice of generating artworks by the use of autonomous computer systems has already existed for more than fifty years1, its artistic endeavor of parsing data to give shape to artworks has only for the past ten years acquired prominence in both media art and contemporary design worlds, thus urging attention to its methods and reasonings.

It is by the maneuver of parametrization, the process of assigning variable parameters that either influence or change the behavior and output of a system, those generative artefacts are able to incorporate data gathered by technological devices into their composition. The parameters within the algorithms of early generative art worked mainly under the generative principle of randomness, by containing variables that incorporated statistical schemes that influenced the output of the system. Today, the parametric algorithms often take the input of data from a third system that translates analog data into digital data. Where in the past, digitally produced randomness played the central role, today, the serendipity of the analog world have its input through data turned digital.

At times facing the danger of being a mere aestheticization, whereas too a “visualisation” of datasets in perceivable forms, artworks generated by algorithms with the input of data are usually conceived as a mere interplay between the object from which the data is gathered, the artist who developed the algorithm, and the generated artwork that took such data to build its form from. However, inside the black-box2 of such artefacts, a myriad of other different actants come into play to compose the final artwork. There is the artist who chooses to associate the object of question with a specific form, there is the computer that processes the algorithm programmed by the artist, there is the technological device used to extract analog data from the object, there is the printing or viewing machine of the generated artwork, and there is the digital data itself. This collective formed by such different actors come into a narrational play, where the artwork may be less perceived by its generated form or even to the analog data it is based on, than it is to the story of associations it is constituted of. Could the narrative inscribed between these actants be the very central material of data-based generative artefacts?

1.1 A first example

In Cosmos, the artist duo Semiconductor created a wooden sculpture made from carbon dioxide measurements from the Forestry Commissions Alice Holt Forest in the United Kingdom, and placed the sculpture afterwards on the same forest from where the data was gathered from, as if returning the “data” to its original habitat. The official project’s description from the artist’s website goes as follows:

Cosmos is a two metre spherical wooden sculpture that has been formed from scientific data made tangible. Interested in the divide between how science represents the physical world and how we experience it, Semiconductor have taken scientific data as being a representation of nature and are exploring how we can physically relate to it. Located in the Forestry Commissions Alice Holt Forest, U.K., the sculpture is made from one year’s worth of measurements of the take up and loss of carbon dioxide from the forest trees, collected from the top of a 28m high flux tower located nearby in Alice Holt Research Forest. To reveal the visual patterns and shapes inherent in the data, Semiconductor developed custom digital techniques to translate the data from strings of numbers into three-dimensional forms. The result is complex interference patterns produced by the waveforms and patterns in the data. Through this process of re-contextualising the data it has becomes abstract in form and meaning, taking on sculptural properties. These sculptural forms become unreadable within the context of science, yet become a physical form we can see, touch, experience and readable in a new way. Here, humanising the data offers a new perspective of the natural world it is documenting. The definition of cosmos is a complete, orderly, harmonious system and here refers to the sources of the combined data which work in harmony to make the forest what it is. (Semiconductor, 2012)

Cosmos questions neither scientific data nor the phenomenon it represents. Instead, the sculpture embraces scientific data as a representation of nature, and explores the aesthetic possibilities that the scientific representation of natural phenomena carries: how to turn strings of numbers taken from technological devices away from the context of scientific discourse, towards a humanized, graspable, sculptural one? Cosmos refers to scientific data and the aesthetic possibilities inscribed in such data, however, the sculpture does not turn scientific data into scientific knowledge nor a scientific understanding of the phenomenon it represents. It takes scientific data as a raw material for artistic maneuver, that through a parametric algorithm is turned into a sculpture. As the raw material, detached from the scientific knowledge it originally was part of, the data plays only an aesthetic role in the sculpture, vaguely related to variances of the phenomenon itself.

However, the sculpture does not incorporate only data: it incorporates a narration, a story of "make-believe". The narrational aspect of such artefact stands only loosely by the microform that its generative algorithm translates from. Rather, it stands for the sole point, as a black sphere made out of 1-year data of carbon dioxide, sitting in the same forest it was taken from. It stands by its supporting video that narrates the story of such data, and all its translating maneuvers and actants that are part of it. It stands by the translation of the “carbon dioxide” phenomenon to analog scientific data gathered from the 28m high flux tower located nearby the forest, the translation of the analog data to digital data by a technological device, the digital algorithm that translates the data to a three-dimensional form, the translation of a digital file to a tangible object, and at last, the translation of the object into a work of art.

Data, in Cosmos, is a staged element within a plot of translation. Cosmos brings to the senses less the visualization of each data point, but more the very fact that this data existed - or may have existed. The knowledge that Cosmos produces does not carry a deeper understanding of the phenomenon it represents. However it may create the idea of a third, a new object, a sculpture born less from scientific data and the natural phenomenon, and more from its speculative story: the story of the carbon dioxide's scientific data that formed a black sphere inside the forest, making the forest closer to what it is.

As Bruno Latour writes about one of the meanings of technical mediation: “techniques modify the matter of our expression, not only its form” (Latour, 1999, p.185). How does the technical translation of objects modify the matter of the generated artwork? Would this distance between the natural phenomenon and the sculpture’s design, one with an indivisible narration of consecutive translating actants, be an evidence of the speculative nature of such artefact? Is the gathering of data from carbon dioxide already a form of speculation performed by the antenna?

2. Unboxing generative artefacts

Blackboxing, as Latour conceives, is "the way scientific and technical work is made invisible by its own success" (Latour, 1999, p.304). He continues and states that "when a machine runs efficiently, when a matter of fact is settled, one need focus only on its inputs and outputs and not on its internal complexity" (Latour, 1999, p.304). In an analog linear manner, the following graph points out the three blackboxes that constitute the systems of generative artefacts:

Figure 1. First level of unboxing of a generative artefact.

Beyond pointing out the three main blackboxes, this first comprehension layer already points to the two key translations that occur during the process of creation of the Artefact. A chosen Object (light, traffic, temperature) has a certain aspect of it translated into a dataset of discrete numbers. Either at the same time or at a further moment, the dataset is translated into a new medium (a sculpture, a sound, a video), an Artefact. This graph exposes the linear narration of these artefacts, a tale of its technical development which also serves as a general description of the artwork itself. In order to understand the translating actants inside the blackbox of these artefacts and their interplay with the narrative aspects of the artwork, more black-boxes must be opened in a more complex chain of translations.

2.1 The artefact’s network

Figure 2. The generative artefact's chain of translations.

The above diagram (Fig. 2.2) depicts the key chain of translations necessary for the generative artefact to be materialised. As Latour conceives, translation means “displacement, drift, invention, mediation, the creation of a link that did not exist before and that to some degree modifies the original two” (Latour, 1999, p.179). This unboxing breaks down the previously analysed relation between the Object, the Data, and the Artefact, in a technical mediation between even more actants which mainly perform a successive translation from the initial Object to the Artefact in the end. The key point of this chain is, however, the translational processes that are happening in-between. Would the material properties of such artefact be less informed by its Data than it is by the sensor (Input Interpreter) that retrieved it?

The diagram demystifies the potential fiction that generative artworks are solely informed by a certain object’s data and algorithm. Even more, each and every actant depicted above can also be unboxed to reveal a whole other chain of translational actants, of which are no less constituent of the final Artefact, although they exercise a smaller influence in its form. It is clear, that the matter that informs the artefact is the very technical mediation between all the actants of the above chain.

In this intricate chain of events, one substantial change to the actants would influence the whole chain in diverse ways, even their goals. The Object’s goal is not the same when associated to the Interpreter. As Latour (1999) conceives, each association between two or more actants in a translational movement is always symmetrical: the Object, the Input Interpreter, the Data, the Algorithm, the Output Controller, and the Artefact are all symmetrically co-modified throughout the process. What could their new goals be? A moment of speculation is thus unfolded, one that is accessible through the narrative aspects of the Artefact.

2.2 Narrative as actant

Each artifact has its script, its potential to take hold of passerby and force them to play roles in its story (Latour, 1999, p.177)

The Narration is the process of narrating a story. The narrative is the object of the act of narration. As human memory is invariably historical, narratives are tropes of communication, objects that serve as a means of socialization. Once again as Latour states, “science and technology are what socialise nonhumans to bear upon human relations” (Latour, 1999, p.194). It is the narrative aspects of the Artefact, an object constituent of scientific and technical actants, the door to humans from the nonhumans entangled in its chain. The Artefact, with its narrational aspects, is the common result of a series of transformations, but one that exposes its very constituent actants to human socialisation. The narrational aspects are the ones who are the "ghost" throughout the process of the Artefact's development, and they are also the "shell" that keeps all its preceding actants openly accessible to humans. But would these very aspects inscribed in the Artefact, not be a new actant in the preceding chain?

Figure 3.Composition of the socialization of generative artefacts.

The properties of the Artefact, its material qualities, its form, its color, its texture, its smell, its movement, its spatial configuration, by themselves, do not suffice to open the blackbox and expose its preceding network to humans: the properties can only allude to a narration, a narration of its own assembly. Thus the Narrative, whether communicated through words or through allusions in the Artefact, is the key element that makes the socialisation of its preceding actants possible. It is the Narrative that tells the story of the technological manoeuvres necessary for the development of the Artefact, a narrative that tells the procedures of delegation leading to its own constitution. It is the Narrative that tells that this particular curve of the Artefact is associated with the tidal wave movements of a tsunami in the Pacific, or that the sea has in its mess the Artefact as a means to socialise with humans. It is the Narrative the actant that makes it possible for a generative artwork to be not a mere aestheticization of data, nor a random arrangement of input and output objects processed by invisible algorithms3.

The Narrative is thus the one actant that modifies all the preceding actants to work, coherently, towards a new goal. As already described earlier in the analysis of the sculpture Cosmos, the generated artefact is less about its constituent actants, as it is about the Narration that wraps them into a single, coherent, third object. It is this object that is open to the interpretation of the viewer, the one that is open to speculative wondering.

3. The speculative moment

The artist, in hers/his attempt to grasp and visualize an object’s reality, wonder about its form by the means of the evidence she/he can find. An external interpreter, a technical device of sensing, grasps details and quantities of the object, closer to it, and invisible by other means to the artist. The collective formed by the artist in addition to hers/his technical delegates, wonder about the form from the retrieved quantities: a possible form of a third object, one that is more than the data, and more than the qualities perceived. Shaviro, when writing about Graham Harman’s idea of the ontology of objects, says: “(…) precisely because we cannot know things in themselves, the only thing that is left to us is to speculate. We cannot grasp objects cognitively; but we can allude to objects through metaphor and other aesthetic practices.” (Shaviro, 2014, p.48)

The speculation in data-based generative artefacts occurs in the attempt of grasping an object’s inner reality by means of an association between aesthetic and scientific wondering. This speculation is also extended to the technical delegates that gather and process the data taken from the object. The already explained chain of translations inherent to the artefact’s development is a further evidence of the speculative nature it consists of. An endeavour carried by the degree of uncertainty and distance to the object upon each translation manoeuvre, especially the one performed by the algorithm: the actant that turns the graspable quantities from an object into a form. The emerged form is not a form that “is”: it is a form that “could be”.

3.1 Data as evidence

Our third table emerges as something distinct from its own components and also withdraws behind all its external effects. Our table is an intermediate being found neither in subatomic physics nor in human psychology, but in a permanent autonomous zone where objects are simply themselves. (Harman, 2012, p.10).

In a plot where the object always withdraws behind its external effects, the role that data plays need to be further discussed. At times described as scientific, data gathered through technical devices perform scientific procedures of measuring as an attempt to grasp an object. Escaping from being a 1:1 representation of an object, data is itself the result of a translation of mediums, one that is performed upon a particular technically perceivable aspect of an object. Its potential lies in the tracing in time of measurable quantities, a dataset plotted with a plot: the narration of an exterior effect from an object in time.

As quantified external traces of an object, data thus assumes a role of evidence in the narrative inscribed in the artefact. When even the object’s external effects are unreachable to humans, Data is the key evidence of the object’s existence, an evidence that is narrated by its influence in the artefact’s form. The input interpreter assumes in this plot the role of a "probe" (Bogost, 2012), the explorer of an "alien reality" plotting graspable effects it encounters into numbers. The interpreter determines key aesthetic qualities of the data which are not directly linked to the object’s effect (resolution, noise, scale). In that sense, the evidence that data represents is never unmediated and is always subject to a form of translation. Thus data is evidence not only to the object’s existence in time, but of the always oblique and partial grasping of an object: an evidence of the speculation that the artist and the algorithm perform together to generate the artefact.

3.2 Aesthetic manoeuvre

The work of the artist Nathalie Miebach explores the role of visual aesthetics in the translation of scientific data. She questions the traditional data visualisation performed by science, by assuming data as raw material for aesthetic reasoning. By gathering data from the environment by means of simple home-made devices, Miebach translates the numbers into meticulously woven structures without computers, however yet in an algorithmic manner. In “Arctic Sun - Solar Exploration Device for the Arctic” (Miebach, 2006), the artist recorded with technical devices the gravitational influence of both Sun and Moon on the Arctic for two days, and also the tidal changes, moon phases, and solar path during the period. Each type of element in the sculpture is informed by one of the data layers, which together composes a whole narrative about two days inside the Arctic’s environment.

Taking data as evidence, the artist is confronted with the task of crafting a process that translates the data into forms able to tell a story of the object’s existence. It is a speculative endeavour, insofar it is an attempt to establish an artefact that “alludes to an object that cannot quite be made present” (Harman, 2012, p.14). It is also an aesthetic endeavour to form stories out of data, as well as to translate the emergent narratives into meaningful forms. The generative artefact, in itself, wraps all its generative actants into a symphony of metaphors: metaphors of an object’s existence in time, one that cannot be fully grasped by other means. The artefact in this sense is a narrative prototype of data.

As Shaviro states: “reality is far weirder than we are able to imagine” (Shaviro, 2014, p.44). The generative artefact attempts, with its association to technical mediums, to open the doors to the weirdness of the reality of objects. By being transparent to the data it informs and to the object from which the data was gathered from, the artefact is capable of narrating the existence of the object it alludes to. However always as a third, an object different than the one humanly grasped, or scientifically evidenced. Thus, the generative artefact proposes an ontological reasoning on what the translated object could be, by turning perceivable humanly imperceivable effects of it, and by also escaping the direct translation of its physical existence. It provides meaningful narratives of an imperceivable object, communicated by the story of its own development, and the generative aesthetics of its form.

4. Conclusion

Speculative Realism insists upon the independence of the world, and of things in the world, from our own conceptualisations of them. (Shaviro, 2014, p.44).

Data-based generative art, although not traditionally linked to the contemporary philosophical turn of Speculative Realism, can be a practice directly linked to its reasonings. The delegation to nonhuman actants, the translation of an object’s effect to scientific data and posteriorly to a perceivable form, and lastly, the narration of the performed steps of translation, are the main evidences of the speculative act inherent to this type of artistic practice. Artefacts generated algorithmically by the input of scientific data are independent of our own conceptualisations of them, as well as from the physicality of the object from which they have taken data from. Artists and technical devices speculate together towards the formation of a third object, born from technical-scientific procedures and an object’s external effects.

It is only through narration that these types of artefacts fulfil the task of ontological reasoning. The narrative aspects of such artefacts are the key factors that wrap the artefact both in its intrinsic and extrinsic compositions. It is first, a narration of its own constitution, a technical story of the series of translations and actants that led to the emergence of the artefact. It is this narrative the one that inscribes the artefact in a socialisation process to both humans and nonhumans, as it is evidence of the artefact’s association to the objects that it prescribe. And it is in second, a narrative of data. It is this second narrative that serves as evidence of an object’s existence, thus fostering the speculative manoeuvre of ontologically defining what the object could be, by translating its data into a form.

Such combined narration may be inscribed in the artefact’s form, or attached to it by other means. Both form, however, a necessary material for the ontological speculation that data-based generative artefacts are capable of. The craft of such speculation needs to be precise in its translating manoeuvres, for the artefacts bare the risk of formulaic aestheticization and vagueness of meaning. The task of the artist is thus crafting the coherent translational algorithms, and choosing the precise translating actants that can, in the end, play their roles on the speculative plot, an artefact that is able to suspend the disbelief of a third object that cannot quite be made present.

References

Bogost, I., 2012. Alien Phenomenology, Or, What It’s Like to be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Campbell, J., 2000. Delusions of Dialogue: Control and Choice in Interactive Art. Leonardo, 33(2), pp.133-136.

Harman, G., 2012. The third table. Documenta (13): 100 Notes - 100 Thoughts / 100 Notizen - 100 Gedanken, Volume 85. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Latour, B., 1999. Pandora’s Hope. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Miebach, N., 2006. Arctic Sun: Solar Exploration Device for the Arctic [Online] Available at:

Semiconductor, 2012. Cosmos. [Online] Available at:

Shaviro, S., 2014. Speculative Realism: A Primer. Spekulation, Text zur Kunst, 93, pp.40-52.

1 The first generative art exhibition, "Generative Computergrafik", which featured artworks by Georg Nees, occurred in Germany in 1965.

2 The term "inside the blackbox" aims to illustrate the opposite of the process of "blackboxing", as conceived by Bruno Latour (1999).

3 See Jim Campbell’s Formula for Computer Art (Campbell, 2000). Campbell constitutes a critic towards computer art, exposing the risk of it becoming a formulaic aestheticization of data. The formula does not account, however, the narrational aspects of generated computer artworks, aspects that if well crafted (as described above), are able to unbox and take off from invisibility the processes from which such works were developed.