Hackerspaces: espaços colaborativos de criação e aprendizagem

Diego Fagundes da Silva é arquiteto e urbanista. Mestre em Urbanismo, História e Arquitetura da Cidade. É um dos fundadores do hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Clube. Estuda arquitetura, design, ilustração e projetos artísticos envolvendo exposições e intervenções de arte pública.

Erica Azevedo da Costa e Mattos é arquiteta e urbanista. Mestre em Urbanismo, História e Arquitetura da Cidade. Co-fundadora do hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Clube. Estuda interfaces da Arquitetura e do Urbanismo com tecnologias emergentes e em processos colaborativos de criação e aprendizagem.

José Ripper Kós é arquiteto e urbanista. Doutor em Tecnologia da Informação e História da Cidade. Professor da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) e do Departamento de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), onde coordena o Curso de Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Estuda computação gráfica e arquitetura, representação urbana através de modelos 3D, bancos de dados e sustentabilidade.

Como citar esse texto: MATTOS, E. A. C.; SILVA, D. F.; KÓS, J. R. Hackerspaces: espaços colaborativos de criação e aprendizagem.V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 10, 2014. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus10/?sec=4&item=6&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 18 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Esse artigo procura compreender e apresentar os hackerspaces como uma manifestação contemporânea e expandida de um hacker ethos, que traz consigo modos de criação, colaboração e aprendizagem associados à ação direta e ao exercício constante de olhar, repensar e reinventar em relação ao mundo cada vez mais tecnologicamente mediado. A presente investigação se apoia em aportes discursivos e teóricos associados à nossa experiência empírica de observação participante com o hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Clube, em Florianópolis, Santa Catarina. Nesse sentido, apontamos a importância em se entender esse movimento de um ponto de vista histórico, social e ético. Visto dessa maneira, essas questões deixam de ser meramente técnicas e passam a ser tomadas como oportunidades para novas formas de nos relacionarmos com o mundo.

Palavras-chave: hackerspaces, hacker ethos, hacking, apropriação social da tecnologia, coletivos tecnológicos.

Introdução

Uma ênfase renovada em formas participativas de produção e aprendizado está transformando nossa paisagem social. O Do it yourself (DIY) amplificado tecnologicamente do simples ato de fazer exercido por artistas, artesãos e hobistas tornou-se a metáfora dominante para uma variedade de práticas sociais e econômicas que exigem amplas modificações culturais para as quais são concebidos novos espaços de ação.

Hackerspaces são, de forma simplificada, lugares físicos operados comunitariamente, na figura de laboratórios ou oficinas com ferramentas e recursos compartilhados, onde pessoas podem se reunir e trabalhar em projetos, frequentemente vinculados à tecnologia. Eles se apresentam como uma entre diversas organizações espontâneas - grassroots - (SCHROCK, 2014) geradas na sociedade vinculadas às rápidas transformações no contexto da sociedade da informação. Essas transformações apontam para novas formas de nos relacionarmos com o mundo, a partir das quais surge a figura do hacker, que condensa no imaginário contemporâneo diferentes discursos, anseios e expectativas frente a essa realidade cada vez mais tecnologicamente mediada.

O ethos hacker, que remonta à década de 1960 no contexto universitário do Massachusetts Institute of Technology - MIT (LEVY, 1994), reinstancia ideais de liberdade e autonomia do indivíduo (COLEMAN; GOLUB, 2008) em uma época marcada pela transitoriedade, pela emergência de novos paradigmas produtivos e modelos de construção de conhecimento. O hacking, como articulação desse ethos, pode ser visto assim como uma abordagem intervencionista direta e crítico-criativa (BUSCH, 2008), uma maneira de agir capaz de se estender a vários níveis do campo social e diferentes áreas do conhecimento (BUSCH; PALMÅS, 2006).

Esse artigo procura apresentar os hackerspaces como uma manifestação contemporânea e expandida de um ethos hacker, que traz consigo modos de criação, colaboração e aprendizagem associados à ação direta e ao exercício constante de olhar, repensar e reinventar. Nossa investigação se apoia em aportes discursivos e teóricos associados à nossa experiência empírica de observação participante com o hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Clube (Tarrafa HC), em Florianópolis, Santa Catarina.

Começamos essa exploração por estabelecer um contexto histórico apontando desde seus antecedentes e origens ao posterior desenvolvimento em escala global do fenômeno dos hackerspaces. Em seguida descreveremos o processo que levou a formação do hackerspace Tarrafa HC em Florianópolis, para então analisar suas práticas e atividades dentro do contexto geral do movimento que define esses espaços.

Naturalmente, como arquitetos, nosso interesse recai sobre determinados aspectos levantados pelos hackerspaces, entendendo-os como base referencial de extrema importância em inúmeros níveis que atravessam a formação e a prática profissional, bem como nossa própria postura frente ao mundo contemporâneo. Nossa perspectiva parcial - em certo ponto contagiada por nossa experiência como arquitetos e membros de um hackerspace - é o filtro através do qual procuramos entender esse movimento.

Hackerspaces: a emergência de um movimento

Os hackerspaces, em configurações semelhantes às que conhecemos hoje, surgiram na Alemanha em meados da década de 1990 sob a influência do Chaos Computer Club (CCC), associação de hackers entre as mais antigas e maiores do mundo, fundada em 1981. Entre os primeiros, estão a divisão local da associação, CCC Berlin, juntamente com o clube c-base, ambos sediados na capital. Em 2006, seguindo as inspirações alemãs, o hackerspace Metalab foi fundado em Viena na Áustria, dando início à disseminação desses espaços na Europa, sob os mesmos princípios, ou seja, com um enfoque na construção de uma infraestrutura espacial aberta para o encontro social e o desenvolvimento de projetos.

Fig. 1 - Metalab, 2012. Fonte: Mitch Altman (CC BY-SA 2.0) - https://www.flickr.com/photos/maltman23/8260407658/. Acessado em 5/07/2014.

No ano de 2007 a experiência desses hackerspaces europeus foi compartilhada com um grupo de hackers americanos que realizavam uma viagem ao encontro internacional Chaos Communication Camp sediado na Alemanha. Após as visitas organizadas a diversos espaços alemães e austríacos, membros do hackerspace C4, da cidade de Colonia, apresentaram o documento Hacker Space Design Patterns (OHLIG; WEILER; HAAS, 2007). Esse documento continha um conjunto de orientações gerais para a criação e organização de um hackerspace, desenvolvidas a partir do aprendizado empírico dos europeus.De volta aos Estados Unidos, estimulados com o que viram na viagem que ficou conhecida como Hackers On A Plane (TWENEY, 2009), diversos integrantes daquele grupo decidiram fundar hackerspaces em suas cidades. Destaque para o NYC Resistor em Nova York, o HacDC em Washington e o Noisebridge em São Francisco (PETTIS; SCHNEEWEISZ; OHLIG, 2011).

No final de 2008, ano seguinte ao Hackers On A Plane, foi realizado durante o 25th Chaos Communication Congress (25C3) o painel Building an international movement: hackerspaces.org, com vários representantes de novos hackerspaces relatando o crescimento desses espaços, que agora passam a ser encarados com parte de um movimento internacional, e também apresentando a ideia da plataforma online hackerspaces.org, composta por uma página wiki, blog e lista de discussão, com o lema build! unite! multiply! (“Building an international movement: hackerspaces.org”, 2008). Desde 2008 a wiki hackerspaces.org mantém um cadastro de hackerspaces espalhados pelo mundo e atualmente (julho de 2014) possui cerca de 1000 espaços ativos listados - espaços esses que se consideram parte do movimento, já que o registro é livre e feito pelos próprios grupos.

O primeiro hackerspace do Brasil, o Garoa Hacker Clube, surgiu em 2010 na cidade de São Paulo após aproximadamente um ano de discussões. As primeiras conversas começaram em junho de 2009 e no final de agosto de 2010 foi inaugurado o espaço físico permanente de 12m² na Casa da Cultura Digital de São Paulo. Desde fevereiro de 2013, o Garoa HC está localizado em sua sede própria, uma casa no bairro de Pinheiros (GAROA.NET.BR WIKI, 2013). O Garoa HC abriu caminho para a criação de diversos outros hackerspaces no Brasil, incluindo o Tarrafa Hacker Clube em Florianópolis.

Embora o desenvolvimento que apresentamos possa parecer claro e objetivo, essa linha é uma perspectiva que inevitavelmente deixa de lado desenvolvimentos paralelos e anteriores significativos. Podemos, assim, apontar uma série de antecedentes, de espaços e grupos com conformações semelhantes, que embora não correspondam em sua plenitude a esse modelo, certamente influenciaram de maneira determinante e em vários aspectos o que viria a ser esse movimento global. Aspectos relacionados ao DIY “tecnológico” da cultura hacker remontam ao rádio amadorismo da década de 1920 (GALLOWAY et al., 2004), atravessando os anos 50 com os entusiastas do ferromodelismo do TMRC (Tech Model Railroad Club) no MIT que por fim transportaram o conceito para o contexto da computação (LEVY, 1994). Coleman (2013) relata que o crescimento desse movimento retoma em novo contexto a prática do hardware hacking, já notavelmente presente nas atividades do Homebrew Computer Club na Califórnia em meados de 1970. Já Grenzfurthner e Schneider (2009) defendem que os primeiros hackerspaces ligam-se diretamente a manifestações contraculturais dos anos 1970 pós movimento hippie, se aliando a táticas micropolíticas, ou seja na construção de “novos mundos” dentro de um mundo antigo, buscando criar novas relações e apropriações espaciais.

Podemos exemplificar que, paralelamente ao surgimento dos hackerspaces na Alemanha, surgiam também os hacklabs, relacionados à tradição das ocupações, chamadas de squats, e do ativismo de mídia (MAXIGAS, 2012). Como notável diferença ideológica, Maxigas (2012) ainda aponta que a maioria dos hacklabs faziam parte de uma cena explicitamente politizada. Na Itália os hacklabs surgiram sob a influência do movimento autonomista (BAZZICHELLI, 2008) enquanto na Espanha, na Alemanha e na Holanda, os hacklabs estiveram relacionados principalmente a movimentos anarquistas (YUILL, 2008). Desse período, foram especialmente relevantes, enquanto ativos, os hacklabs holandeses ASCII (Amsterdam Subversive Center for Information Interchange) e PUSCII (Progressive Utrecht Subversive Centre for Information Interchange). Por outro lado, os hackerspaces - que se desenvolveram sob a influência da esfera libertária do grupo Chaos Computer Club - não necessariamente se posicionavam de forma aberta em relação à política. Enquanto os envolvidos em ambas as cenas considerariam suas próprias atividades como orientadas para a libertação do conhecimento tecnológico, as interpretações dessa “liberdade” são divergentes. Nesse sentido a genealogia dos hackerspaces também poderia ser vista sob o ponto de vista dos hacklabs.

Recentemente, a denominação makerspace tem ganhado força - especialmente nos Estados Unidos - e embora também seja muitas vezes vista como um sinônimo para hackerspace, a mudança de nome é um indicativo de uma inclinação maior a associações com o emergente movimento maker (ANDERSON, 2012) em detrimento de uma cultura estritamente hacker. O movimentomaker a que Anderson (2012) faz referência é a junção entre o espírito DIY, a cultura de compartilhamento web e ferramentas digitais, atingindo uma nova e surpreendente escala global. Discussões sobre diferenças entre hackerspaces e makerspaces já foram iniciadas, em alguns casos incluindo também comparações com outros espaços comunitários como FabLabs e TechShops que também oferecem acesso público e compartilhado a equipamentos e ferramentas (CAVALCANTI, 2013). Apesar da eventual associação do termo makerspace com a revista estadunidense MAKE Magazine - já criticada por promover a sanitização do movimento maker (HERTZ, 2012) - diferenças entre hackerspaces e makerspaces não são claras ou consensuais, e muitos envolvidos não fazem nenhuma distinção. Entretanto, FabLabs e TechShops possuem origens e motivações bem específicas, remetendo respectivamente ao ambiente acadêmico e ao profissional/comercial. De características igualmente diferentes, são os medialabs e laboratórios cidadãos, dedicados ao fomento da digitalização a partir do acesso e formação do público, geralmente com apoio de administrações públicas. (SANGUESA, 2013)

De modo geral, sob diferentes formatos e denominações, origens e objetivos, estamos acompanhando o crescimento de uma tendência global de espaços colaborativos de criação, trabalho, aprendizagem e ativismos relacionados à democratização da cultura digital.

Por outro lado, ressaltamos que, em meio a essa tendência, os hackerspaces possuem especificidades que devem ser exploradas, as quais associamos a relação com um ethos hacker que nos últimos anos passa a alcançar um número cada vez maior de pessoas de diversas áreas, deixando de ser restrito apenas a subculturas undergrounds. Percebemos, em suas práticas e operações, um posicionamento exploratório, crítico e criativo em relação à tecnologia e sua relação com a sociedade.

Panorâma Analítico

Um entendimento preciso do que é um “hackerspace” não existe mesmo entre as pessoas envolvidas com o movimento, o que é reforçado por Mitch Altman, um dos fundadores do Noisebridge em São Francisco. Segundo Altman (OH, 2011), é possível reconhecer quando se está dentro de um, porém todos são únicos, assim como as pessoas que constroem esses espaços. Schrock (2011) concorda que os indivíduos que frequentam os hackerspaces não podem ser uniformemente classificados, sendo bastante heterogêneos em suas motivações para o uso do espaço. Segundo esse autor, uma identidade coletiva define as especificidades de cada hackerspace e é gerada pelos interesses momentâneos de seus membros, suas atividades e eventos em comum.

Apesar de um consenso não ter sido alcançado, as discussões sobre a questão no interior da própria comunidade tornaram possível para Moilanen (2012) elencar cinco critérios gerais do que ser um hackerspace significa: (a) é pertencente e administrado por seus membros em espírito de igualdade; (b) não possui fins lucrativos e é aberto para o mundo exterior; (c) é um espaço onde pessoas compartilham ferramentas, equipamentos e ideias sem discriminação; (d) possui forte ênfase em tecnologia e invenção e, (e) possui um espaço compartilhado (ou está em processo de aquisição de um) como centro da comunidade.

Por outro lado, membros e acadêmicos parecem concordar que hackerspaces podem ser compreendidos como um “terceiro lugar” (“Building Hackerspaces Everywhere”, 2009) (MOILANEN, 2012) (SCHROCK, 2014). Tal conceito definido por Oldenburg (1999) faz referência aos espaços de encontro e ligações informais, fora de casa (primeiro lugar) e do trabalho (segundo lugar), que facilitam e promovem interações comunitárias mais amplas e criativas.

Esther Schneeweisz “Astera”, membro do hackerspace vienense Metalab, destaca que, como um “terceiro lugar”, os hackerspaces podem se manifestar de formas bastante diversas de acordo com os interesses dos envolvidos, com foco maior ou menor em áreas como: hacking de hardware e engenharia reversa relacionados a eletrônica e microcontroladores; programação e segurança computacional; tecnologia e arte; etc. Por outro lado, Schneeweisz ressalta que as atividades não são limitadas a esses exemplos, já que o hacking pode ser direcionado a qualquer tema - se trata de olhar de uma forma diference, repensando e reinventando determinado tópico. (“Building Hackerspaces Everywhere”, 2009).

Eriksson (2011) identifica e categoriza algumas das atividades produtivas encontradas em hackerspaces em três grupos. O primeiro grupo por ele identificado como “modificação de sistemas fechados” engloba o significado de hacking mais tradicional, e basicamente se refere à compreensão, modificação e ampliação de funcionalidades de um dado sistema. Já o segundo grupo “composição através de meios simples”, diz respeito ao processo de criação fazendo o uso de componentes e elementos básicos (ex: sensores e atuadores) frequentemente obtidos através de sucata e outros objetos. Como terceiro grupo de atividades, a “experimentação com hardwares e softwares de código aberto” reflete o uso crescente de dispositivos de código aberto como o Arduino e os kits de impressoras 3d para a elaboração de novos projetos.

Porém, hackerspaces são espaços comunitários onde diversas atividades acontecem simultaneamente, muitas das quais não poderiam ser consideradas produtivas no sentido usual da palavra. Pessoas frequentam o espaço para interagir, estabelecer conversas casuais ou simplesmente se reunir sem nenhum propósito específico. Ao invés de serem vistos como um meio para cumprir objetivos claros previamente definidos, hackerspaces devem ser vistos como lugares onde metas, motivações e desejos podem ser explorados, descobertos e construídos (ERIKSSON, 2011).

Para Blankwater (2011), os hackerspaces funcionam como lugares de aprendizagem. Sem uma hierarquia formal mas com uma estrutura horizontal flexível toda pessoa é um potencial receptor e emissor de informação: “Hackerspaces oferecem diferentes modos de aprendizagem que envolvem a criatividade, a procura por fontes próprias, o pensamento ‘fora-da-caixa’, descentralização, colaboração e a mistura de disciplinas” (Blankwater, 2011, p. 115, tradução nossa)1

O Tarrafa Hacker Clube

O Tarrafa Hacker Clube (Figura 2) constitui-se hoje no único hackerspace ativo da cidade de Florianópolis, abrigando em sua sede eventos, oficinas e encontros regulares abertos. Sua estrutura segue a tendência iniciada por espaços como c-base e Metalab, incorporando fortemente as referências dos espaços dos Estados Unidos como Noisebridge e NYC Resistor e ainda com grande influência do Garoa HC. Em seu processo de formação podemos identificar, além de elementos específicos, muitos fatos comuns ao desenvolvimento de outros hackerspaces pelo mundo, entre os quais podemos citar a conformação de uma comunidade, esta ávida por um espaço para estabelecer colaborações, a intensa atividade através de listas de discussão e um forte interesse em se integrar à comunidade local.

Fig. 2 - Panorama do Tarrafa Hacker Clube, 2014. Fonte: Autores.

Histórico

O Tarrafa HC deu seus primeiros passos com a formalização de um pequeno grupo através da criação de uma lista de discussão no final de novembro de 2011. No início de 2012 a lista de discussão passou a ter uma maior movimentação, com o ingresso de novos interessados e o início pela busca de um espaço físico e divulgação do projeto para a comunidade geral. Uma primeira palestra foi realizada em março de 2012 na Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina abordando o conceito dos hackerspaces e com o objetivo de apresentar a proposta de criação de um espaço desse tipo em Florianópolis.

O oferecimento de palestras, oficinas e cursos no primeiro semestre de 2012, foi bastante importante no processo de consolidação do Tarrafa HC como um grupo. A participação de alguns membros no Fórum Internacional do Software Livre (FISL) em Porto Alegre no final do julho de 2012 possibilitou o encontro com participantes de outros hackerspaces do Brasil, como o Garoa HC de São Paulo e o então recém-formado MateHackers de Porto Alegre. Esse encontro fez com que o grupo priorizasse ainda mais a realização de atividades e projetos, paralelamente a busca por uma sede própria, em detrimento dos aspectos burocráticos de oficialização da associação.

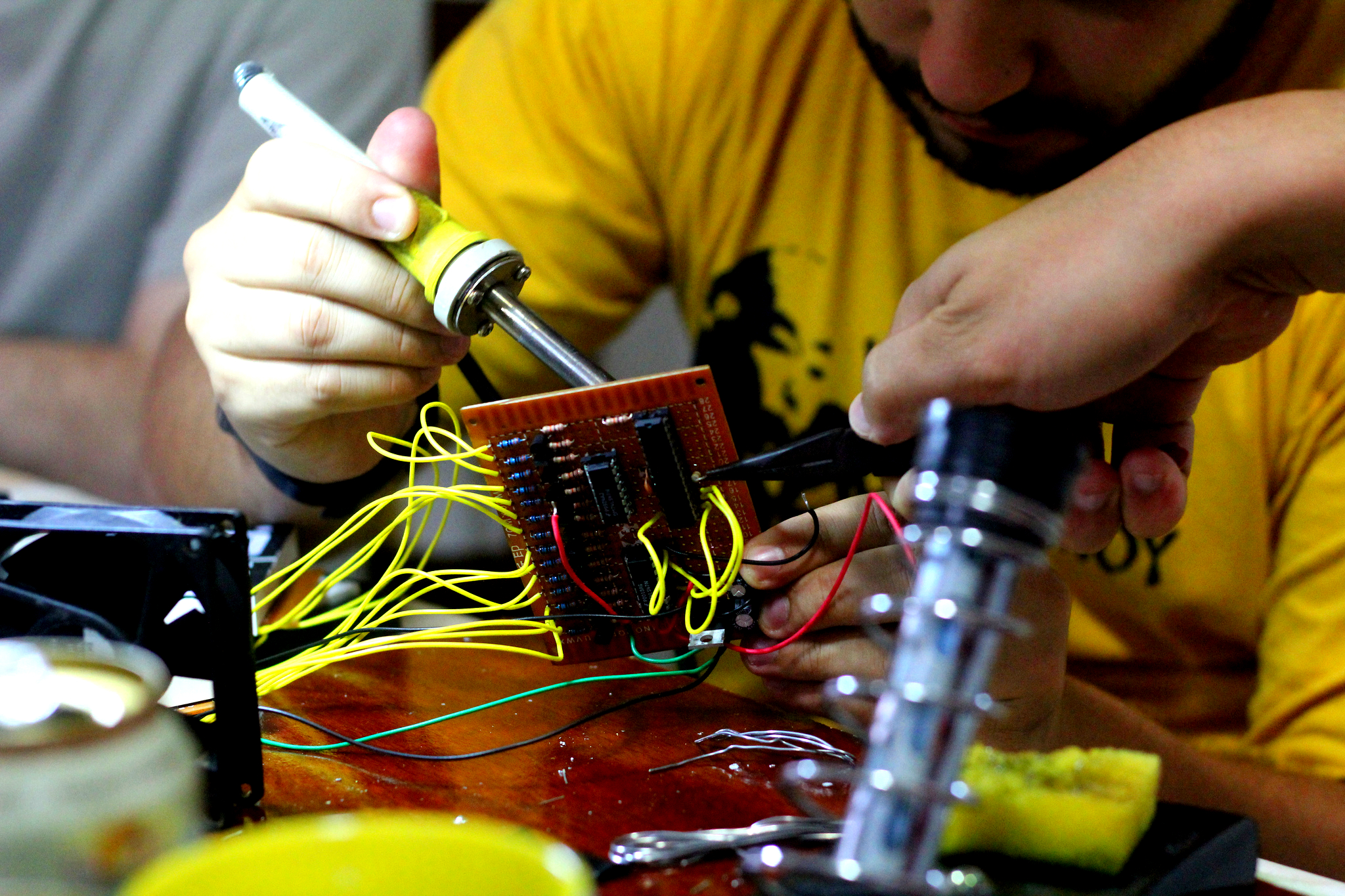

Assim, em agosto de 2012 foi iniciado o primeiro projeto coletivo do Tarrafa HC, denominado Beer Counter (Figura 3), que consistia na criação de um contador digital incrementado pelo acionamento de um botão que mantém o valor final gravado na sua memória. Alguns encontros foram realizados semanalmente na casa de um dos membros para o desenvolvimento desse mesmo projeto e também para criação de instrumentos eletroacústicos, que culminaram no surgimento do primeiro evento regular no mesmo mês, a Noite da Engenharia Reversa e Desconstrução (N.E.R.D.).

Fig. 3 - Encontro para a construção do projeto Beer Counter, 2012. Fonte: Autores.

No mês de setembro o Tarrafa HC ofereceu palestras e oficinas como parte da programação do Ateliê Livre Tecnologias Interativas e Processos de Criação, uma disciplina optativa criada na grade curricular do Curso de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina com o objetivo de discutir e realizar projetos de intervenção utilizando tecnologias acessíveis de computação física. Em meados de outubro de 2012, a disciplina passou a ser ministrada em uma sala disponível no antigo bloco do Departamento de Arquitetura para possibilitar um espaço para um trabalho continuado para os estudantes. Em troca do apoio constante à disciplina, que teve uma segunda edição no semestre seguinte, o Tarrafa HC passou também a usufruir desse mesmo espaço para outras atividades, como reuniões e eventos, estabelecendo ali uma sede temporária. Essa colaboração com a disciplina de projeto já foi tratada com maior detalhe em um trabalho anterior (MATTOS; SILVA; KÓS, 2013).

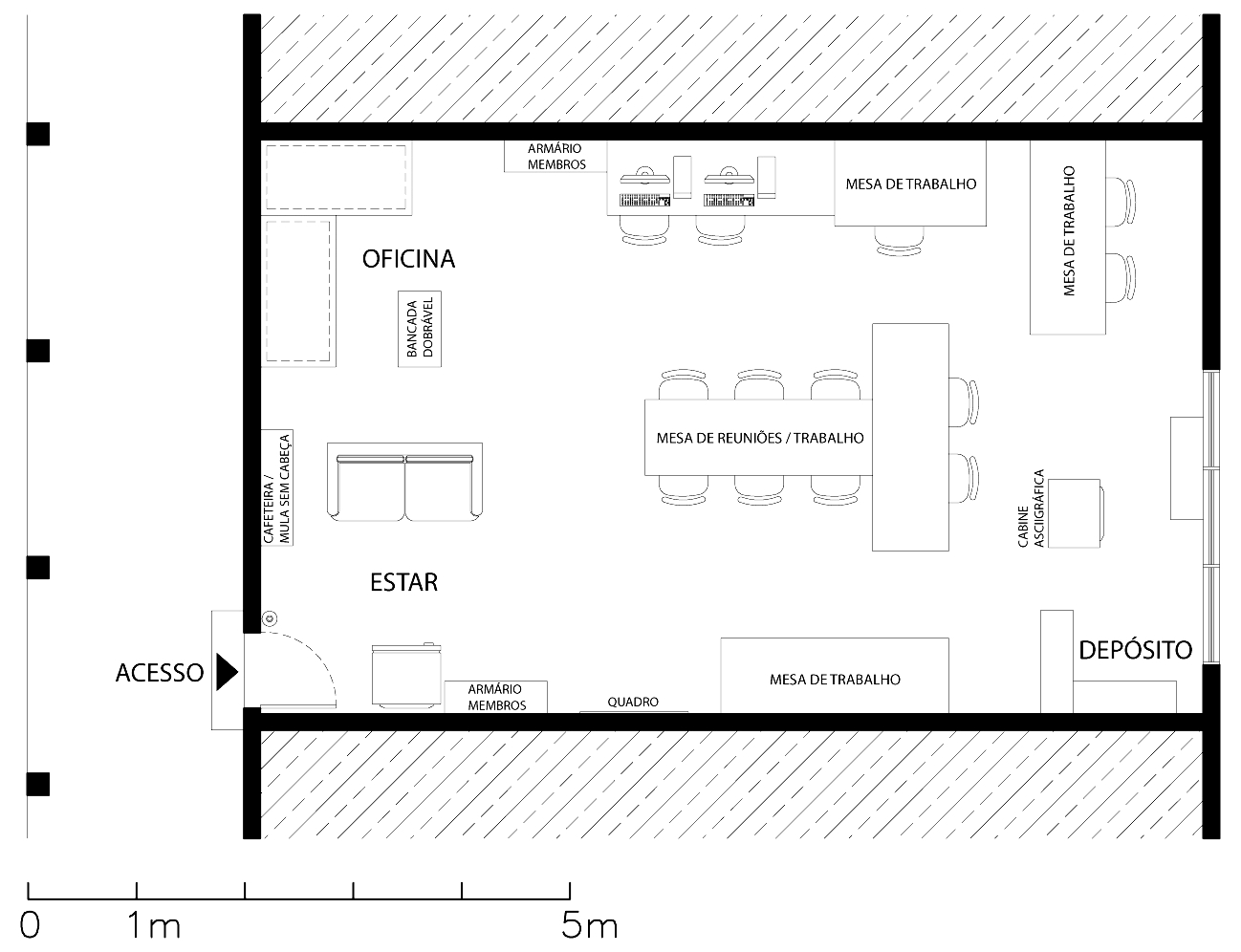

Atualmente o Tarrafa HC permanece no local, em associação com o projeto de extensão acadêmica Laboratório em Tecnologias Emergentes, Inovação e Projeto. A sala conta com 46 m², divididos entre espaço para reuniões e trabalho, uma oficina de marcenaria, área para impressão 3d, depósito para materiais e sucata e um pequeno estar (Figura 4). Ressaltamos que esta configuração está sempre sofrendo alterações para acomodar melhor as atividades ali desenvolvidas, o que confere dinamismo ao espaço.

Fig. 4 - Planta-baixa da sede do Tarrafa Hacker Clube, 2014. Fonte: Autores.

Devemos salientar também que a presença online do Tarrafa HC acompanhou o seu crescimento. Atualmente sua lista de discussão conta com 285 assinantes (julho de 2014) e engloba participantes de outros hackerspaces e indivíduos interessados nas discussões propostas, mesmo que não diretamente envolvidos com as atividades que acontecem no espaço. O hackerspace está também presente na wiki hackerspaces.org, e muitos de seus membros mais ativos participam da lista de discussão da plataforma e das listas de outros espaços, o que promove um importante intercâmbio de experiências e ideias.

Atividades e Práticas

Suas atividades, inicialmente centradas em eletrônica por influência de alguns membros, buscavam a experiência prática em oposição ao alto nível teórico do ambiente acadêmico. A programação de software também esteve presente desde as primeiras atividades, porém bastante vinculada à eletrônica através da relação com microcontroladores e a computação física. Essas práticas estão em conjunção também com a popularização da plataforma Arduino e do movimento open hardware e se alinham com as desenvolvidas em outros espaços, como o NYC Resistor, que iniciou suas atividades com um grupo de estudos em microeletrônica (PETTIS; SCHNEEWEISZ; OHLIG, 2011).

Desses interesses nascem as oficinas já citadas e o primeiro evento regular e mais frequente, a N.E.R.D., baseada no método da engenharia reversa, que busca o entendimento de um sistema a partir da abertura e análise de seus elementos e conexões. Nas N.E.R.D.s, um objeto fechado é escolhido para desmontar e procurar entender suas partes, seu funcionamento e seu processo de criação, a partir da troca de ideias e conhecimentos entre os participantes. Eventualmente tal atividade pode levar à modificação desse objeto ou sistema, alterando-o para outras finalidades.

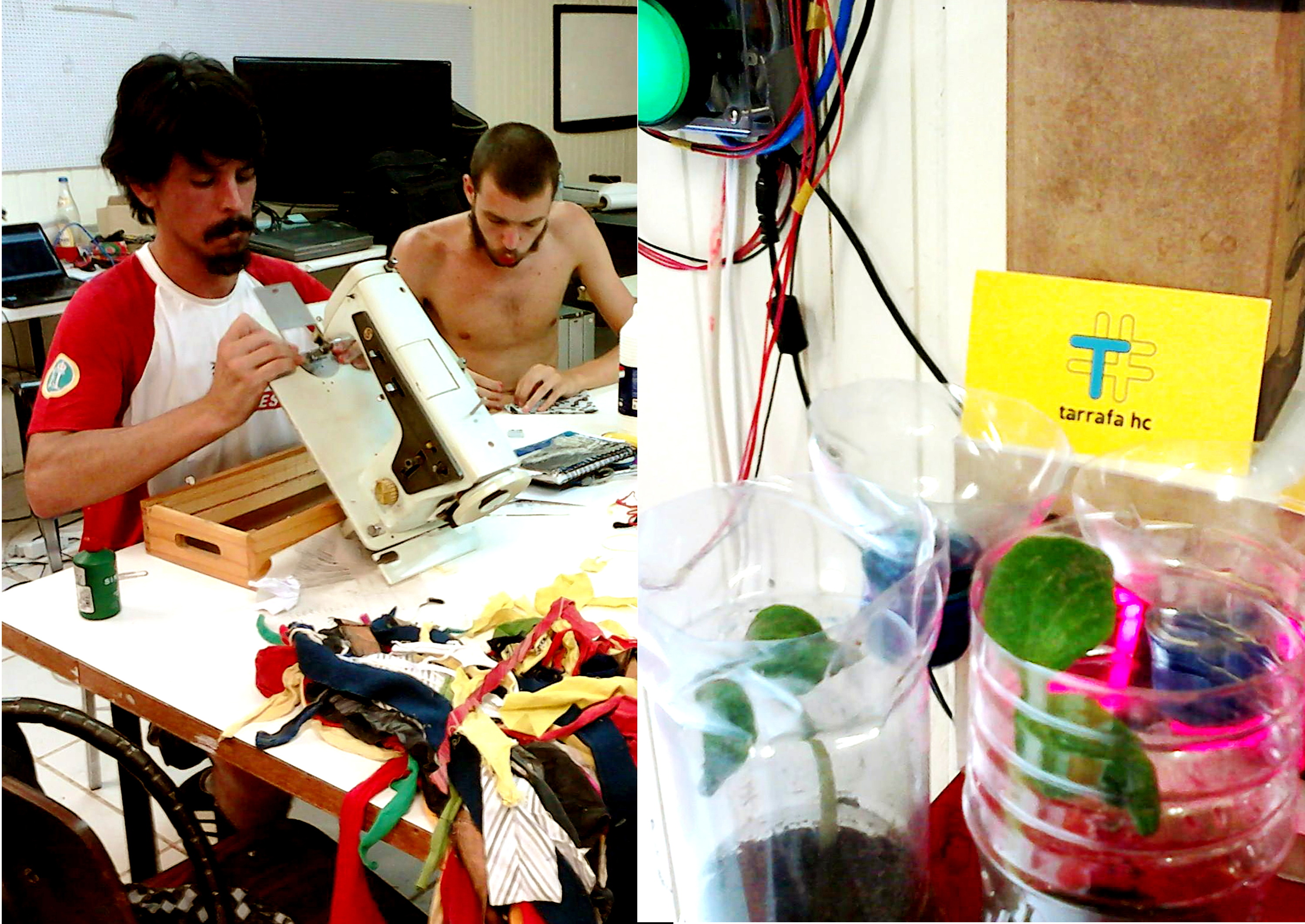

Essa atitude orientada à intervenção direta associada ao hacking (BUSCH, 2008) foi aos poucos se expandindo para outras áreas como costura, agricultura urbana (Figura 5) e arte e tecnologia. Não se trata de uma característica exclusiva desse hackerspace, mas sim uma condição geral relacionada ao que Blankwater (2011) aponta como sendo a mentalidade (mindset)associada ao hacking praticado nesses espaços. Atualmente o Tarrafa HC conta com máquinas de costura, impressoras 3d e muitas ferramentas e materiais obtidos através de doações.

Fig. 5 - Atividades de costura e agricultura urbana, 2014. Fonte: Tarrafa Hacker Clube.

Uma outra atividade que podemos mencionar é a Make: Electronics (Figura 6), uma série regular de encontros que procura promover o aprendizado de eletrônica. Os encontros acompanham o livro homônimo de Charles Platt (2009), em que conhecimentos a respeito de eletrônica são desenvolvidos pelos participantes de forma exploratória através de experimentos. Cada encontro apresenta “tarefas” ou desafios utilizando recursos simples e acessíveis. De caráter semelhante é o grupo de estudos alinhado ao software livre que desenvolve seus encontros seguindo o método Linux From Scratch (L.F.S.), uma série de passos guiados para ao fim compilar um sistema Linux por conta própria. Durante o processo que ocorre também de forma exploratória os participantes procuram aprender sobre o funcionamento dos sistemas operacionais computacionais.

Fig. 6 - Encontro Make: Electronics, 2013. Fonte: Tarrafa Hacker Clube.

Entre os diversos projetos desenvolvidos no Tarrafa HC podemos destacar a Revolta da Antena, realizado durante o período de mobilizações populares que tomaram as ruas de todo o Brasil entre junho e julho de 2013. Inserindo-se no contexto da mídia livre e das transmissões independentes ao vivo nas manifestações, o projeto pretendeu fazer uma contribuição no sentido de criar e oferecer uma estrutura de internet livre em rede. A disponibilização do acesso à internet sem fio aos manifestantes se deu através da criação de pontos de acesso conectados em rede mesh. A estrutura do sistema nada mais era que roteadores alimentados a baterias e instalados em capacetes, por sua vez transportados por manifestantes voluntários denominados “anteneiros”, conectados entre si e a pontos de acesso disponíveis no trajeto. O projeto foi construído com a participação de diversas pessoas em um curto período de tempo, articuladas pela criação de um grupo no Facebook. Contribuições foram feitas nos aspectos técnicos de programação do software utilizado, na montagem dos equipamentos, no desenvolvimento de cartazes físicos e digitais, na campanha na internet para a abertura de redes, na documentação do projeto, entre outros. Esse projeto teve grande repercussão na mídia online e redes sociais tanto locais como nacionais.

A Revolta da Antena foi um projeto essencialmente colaborativo, comunitário e libertário, tanto no seu processo de desenvolvimento como na forma como se inseriu no espaço público da cidade, propondo e modificando relações territoriais. O que podemos identificar, em casos específicos como o do projeto Revolta da Antena, é uma sinergia, que conjugou entre diversos aspectos, um contexto social e político, indivíduos interessados e engajados e uma infraestrutura técnica e espacial, nesse caso, o próprio hackerspace. Não são todos os projetos que alcançam tamanha abrangência, porém destacamos que iniciativas desse caráter reforçam o potencial transformador dos hackerspaces.

Discussão

Alguns aspectos a respeito do funcionamento do Tarrafa HC demonstram-se especialmente relevantes no contexto da presente discussão. Percebemos que a nossa experiência tornou possível encontrar elementos comuns a outros hackerspaces, contribuindo para o entendimento desses como um fenômeno social contemporâneo de caráter espontâneo ligado ao acesso e popularização da tecnologia. Assumimos, assim, os hackerspaces como manifestações expandidas do ethos hacker, que traz consigo valores e práticas de criação, colaboração e aprendizagem priorizando processos e ações exploratórias, livres e horizontais em oposição a formas sistemáticas e hierarquizadas típicas de instituições formais.

Além da autonomia e da valorização da liberdade, os hackerspaces reforçam aspectos como a colaboração, troca de experiências e o compartilhamento de recursos, ao passo que incorporam também outras influências como a da cultura maker e DIY e do movimento open source. Nesse processo, esses espaços comunitários associam e transpassam as mais diversas áreas - como engenharias, computação, ciências naturais, arte, design, arquitetura, entre outras - através dos interesses, conhecimentos e experiências anteriores trazidos pelas pessoas envolvidas. Entretanto, mais do que reafirmar papéis, tais indivíduos estão imbuídos de um espírito questionador que frequentemente expande os limites de suas próprias áreas de origem.

No nosso entendimento, hackerspaces também se enquadram no que Thomas e Brown (2011) se referem como uma nova cultura da aprendizagem (new culture of learning). De acordo com os autores, para cultivar tal forma de aprendizagem, precisamos da combinação de dois elementos: o primeiro é o acesso à rede de informações e recursos praticamente infinitos, e o segundo se trata da existência de um ambiente delimitado que promove total liberdade dentro dos seus limites catalisando a criação e a experimentação.

É importante ressaltar também que mesmo essas estruturas se apoiando em comunidades locais, fortemente vinculadas a espaços físicos providos de recursos materiais, elas necessitam igualmente de uma rede global virtual que as fortalece como movimento e permite a troca de experiências e informações, tanto na forma de projetos e atividades comuns como em recomendações de boas práticas de gestão desses espaços. São assim estruturas trans-locais (ERIKSSON, 2011). Vemos que essas estruturas não seriam possíveis sem a onipresença da internet, que possibilitou a formação de modelos colaborativos de empoderamento e inovação. Situando-se entre o físico e o digital podemos reconhecer nos hackerspaces um caráter essencialmente híbrido desses espaços (CALDWELL; BILANDZIC; FOTH, 2012).

Considerações

Os desafios da sociedade da informação exigem posicionamento crítico assim como novos processos de criação, colaboração e aprendizagem. A forma de organização e as práticas associadas aos hackerspaces possuem um grande potencial para gerar impacto nas mais diferentes áreas do conhecimento. Tais espaços questionam valores defendidos por estruturas profissionais e acadêmicas consolidadas, que têm demonstrado não possuir flexibilidade necessária para se adaptar à complexa realidade social. Assim, eles nos dão indícios relevantes no sentido de redirecionar os processos de produção e ensino contemporâneos.

Por outro lado, entendemos também que os hackerspaces, espaços de apropriação crítica da tecnologia, atualmente passam por um processo de assimilação por uma cultura mainstream. Nesse processo há a possibilidade de sanitização e desideologização para torná-lo acessível e palatável. Isso é natural, visto que é um modo de operação típico dentro dessa lógica de assimilação: transformar processos em produtos, serviços e mercadorias. Nesse processo exclui-se qualquer caráter crítico e subversivo, a exemplo da assimilação superficial e meramente imagética dos movimentos contraculturais dos anos 60 ou do movimento punk dos anos 80 pela indústria cultural. O desafio, e por isso nosso especial interesse, é o de identificar e eventualmente conseguir transpor para outras estruturas aspectos dos hackerspaces que de fato são transformadores e revolucionários.

Algumas práticas e elementos interessantes encontrados nos hackerspaces começam a surgir também através de outros caminhos, no que diz respeito ao compartilhamento de espaços e recursos de trabalho e produção, a exemplo dos FabLabs, TechShops e coworkings, ou mesmo em modelos colaborativos de financiamento e propriedade, como o crowdfunding e o open source. Esses modelos já vêm afetando a prática da arquitetura e da construção de relações espaciais de maneira visível e até mesmo incontestável. Entretanto, mesmo compartilhando essas práticas e elementos, identificamos que um dos aspectos fundamentais dos hackerspaces é justamente o de mais difícil assimilação. Acreditamos que tal fator, entendido aqui como o ethos hacker, é o elemento que dá sentido, questiona e transforma nossa relação com o mundo.

Nesse ponto, nossa posição como arquitetos, partícipes de um ecossistema social bastante específico como o do hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Clube, nos leva a questionar: o que arquitetos - como também designers, artistas, engenheiros e outros profissionais - podem apreender desse tipo de manifestação, ou; quais são as contribuições efetivas de cada campo do conhecimento nesse cenário contemporâneo. Perguntas ainda sem respostas claramente delineadas, mas que nos impelem a ir mais a fundo nesse processo de desconstrução das nossas imagens e consequente relevância.

Hackerspaces são sistemas desestruturadores de certezas onde, a exemplo do hackerspace CCC Berlin, “as coisas estão sempre sob exame minucioso, em discussão, sob ataque. Nada é dado como certo e tudo precisa ser revisitado, desmontado, olhado mais de perto.” (PETTIS; SCHNEEWEISZ; OHLIG, 2011, p. 7, tradução nossa)2

Agradecimentos

À CAPES (Ministério da Educação) e ao CNPq (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação) pelo apoio aos pesquisadores. Ao Tarrafa Hacker Clube e seus membros, por oferecer o apoio necessário à realização desse estudo.

Referências

ANDERSON, C. Makers: the new industrial revolution. Nova Iorque: Crown Business, 2012.

BAZZICHELLI, T. Networking: the Net as artwork. Arhus: Digital Aesthetics Research Center, 2008.

BLANKWATER, E. Hacking the field: An ethnographic and historical study of the Dutch hacker field. Sociology Master’s Thesis—Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2011.

BUILDING an international movement: hackerspaces.org. Mesa redonda com Jens Ohlig, Bre Pettis, Nick Farr, Esther Schneeweisz “Astera”, Philippe Langlois, Jacob Appelbaum e Paul Böhm “Enki” em 25th Chaos Communication Congress (25C3). 60’, 27 dez. 2008. Disponível em: <http://ftp.ccc.de/congress/25c3/video_h264_720x576/25c3-2806-en-building_an_international_movement_hackerspacesorg.mp4>. Acesso em: 30 maio. 2013.

BUILDING Hackerspaces Everywhere. Palestra com Esther Schneeweisz “Astera” em BruCON 2009. 59’45’’, 5 out. 2009. Disponível em: <http://vimeo.com/6911866>. Acesso em: 19 maio. 2013

BUSCH, O. VON; PALMÅS, K. Abstract hacktivism: the making of a hacker culture. Londres; Istambul: Open Mute, 2006.

BUSCH, O. VON. Fashion-able: hacktivism and engaged fashion design. Göteborg: School of Design and Crafts (HDK), Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, University of Gothenburg, 2008.

CALDWELL, G.; BILANDZIC, M.; FOTH, M. Towards visualising people’s ecology of hybrid personal learning environments. ACM Press, 2012. Disponível em: <http://eprints.qut.edu.au/54006/>. Acesso em: 15 out. 2014

CAVALCANTI, G. Is it a Hackerspace, Makerspace, TechShop, or FabLab?MAKE, 22 maio 2013. Disponível em: <http://blog.makezine.com/2013/05/22/the-difference-between-hackerspaces-makerspaces-techshops-and-fablabs/>. Acesso em: 24 maio. 2013.

COLEMAN, E. G.; GOLUB, A. Hacker practice: Moral genres and the cultural articulation of liberalism. Anthropological Theory, v. 8, n. 3, p. 255–277, 1 set. 2008.

COLEMAN, E. G. Hacker (Forthcoming, The Johns Hopkins Encyclopedia of Digital Textuality, 2014), 2013. Disponível em: <http://gabriellacoleman.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Coleman-Hacker-John-Hopkins-2013-Final.pdf>. Acesso em: 5 fev. 2014

ERIKSSON, M. Labbet utan egenskaper, 2011. Disponível em: <http://blay.se/papers/labbet.pdf>. Acesso em: 17 maio. 2013.

GALLOWAY, A. et al. Panel: Design for Hackability. In: 5TH CONFERENCE ON DESIGNING INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS: PROCESSES, PRACTICES, METHODS, AND TECHNIQUES. Proceedings… Cambridge, MA: ACM Press, 2004.

GAROA.NET.BR WIKI. História: Garoa Hacker Clube. Maio de 2013. Disponível em: <https://garoa.net.br/wiki/História>. Acesso em: 16 mar. 2014

GRENZFURTHNER, J.; SCHNEIDER, F. A. Hacking the Spaces. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.monochrom.at/hacking-the-spaces/>. Acesso em: 28 abr. 2012.

HERTZ, G. Interview with Matt Ratto. In: HERTZ, G. (Ed.). Critical Making: Conversations. Critical Making. Hollywood. California USA: Telharmonium Press, 2012, p. 1–10.

LEVY, S. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Nova Iorque, N.Y.: Dell Pub., 1994.

MATTOS, E. A. C.; SILVA, D. F. da; KÓS, J. R. Tecnologias Interativas e Processos de Criação: Experiências de Aprendizagem Transdisciplinares Associadas a um Hackerspace. pp. 572-576. In: XVII Congreso de la Sociedad Iberoamericana de Gráfica Digital, SIGRADI: Knowledge-based Design. Valparaíso - Chile, 2013.

MAXIGAS. Hacklabs and Hackerspaces: Tracing Two Genealogies. The Journal of Peer Production, n.2. Bio/Hardware Hacking, jul. 2012.

MOILANEN, J. Emerging Hackerspaces–Peer-Production Generation. In: Open Source Systems: Long-Term Sustainability. [s.l.]: Springer, 2012, p. 94–111.

OHLIG, J.; WEILER, L.; HAAS, T. Hackerspace Design Patterns. 17 ago. 2007. Disponível em: <http://hackerspaces.org/images/8/8e/Hacker-Space-Design-Patterns.pdf>.

OH, J. Science on the SPOT: Open Source Creativity – Hackerspaces. 26 jan. 2011. Disponível em: <http://science.kqed.org/quest/video/science-on-the-spot-open-source-creativity-hackerspaces/>. Acesso em: 3 abr. 2014

OLDENBURG, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. 3a ed. [s.l.]: Marlowe & Company, 1999.

PETTIS, B.; SCHNEEWEISZ, A. E.; OHLIG, J. (Eds.). Hackerspaces @ the_beginning (the book), 2011. Disponível em: <http://hackerspaces.org/static/The_Beginning.zip>.

PLATT, C. Make: Electronics. 1a ed. Sebastopol, Calif.: Make, 2009.

SANGUESA, R. La tecnocultura y su democratizacion: ruido, limites y oportunidades de los Labs.(DOSSIER). Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnologia y Sociedad, v. 23, n. 8, p. 259, 2013.

SCHROCK, A. R. Hackers, Makers and Teachers: A Hackerspace Primer (Part 1), 2011. Disponível em: <http://andrewrschrock.wordpress.com/2011/07/27/hackers-makers-and-teachers-a-hackerspace-primer-part-1-of-2/>. Acesso em: 20 set. 2013

SCHROCK, A. R. Education in Disguise: Culture of a Hacker and Maker Space. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, v. 10, n. 1, 1 jan. 2014.

THOMAS, D.; BROWN, J. S. A new culture of learning: cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. Lexington, Ky.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011.

TWENEY, D. DIY Freaks Flock to “Hacker Spaces” Worldwide | Gadget Lab | Wired.com. 29 mar. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.wired.com/gadgetlab/2009/03/hackerspaces/>. Acesso em: 17 maio. 2013.

YUILL, S. All Problems of Notation Will Be Solved By the Masses. Disponível em: <http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/all-problems-notation-will-be-solved-masses>. Acesso em: 28 jul. 2014.

1 “Hackerspaces offer different modes of learning that involve being creative, searching for own sources, out-of-the-box thinking, decentralization, collaboration and mixing of disciplines.” (Blankwater, 2011, p. 115)

2 “things are always under scrutiny, under discussion, under attack. Nothing is taken for granted and everything needs to be revisited, taken apart, looked closer at.”(PETTIS; SCHNEEWEISZ; OHLIG, 2011, p. 7)

Hackerspaces: collaborative spaces of creation and learning

Diego Fagundes da Silva is architect and urban planner. Master in Urban Planning, History and Architecture of the City. He is one of the founders of the hackerspace called “Tarrafa Hacker Clube”. He researches architecture, design, illustration and artistic projects involving public exhibitions and interventions.

Erica Azevedo da Costa e Mattos is architect and urban planner. Master in Urban Planning, History and Architecture of the City. She is one of the founders of the hackerspace called “Tarrafa Hacker Clube”. She researches relations between Architecture, Urban Planning, emerging technologies, and creation and learning collaborative processes.

José Ripper Kós is architect and urban planner. PhD in Information Technology and City History. Professor at Architecture and Urban Planning College, at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ); and also at Architecture and Urban Planning Department, at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), where he coordinates Architecture and Urban Planning Degree. He studies computer graphics and architecture, urban representation through 3D models, databases and sustainability.

How to quote this text: MATTOS, E. A. C.; SILVA, D. F.; KÓS, J. R., 2014. Hackerspaces: collaborative spaces of creation and learning. V!RUS, 10. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus10/?sec=4&item=6&lang=en>. [Accessed: 18 July 2025].

Abstract

This paper aims to understand and present the hackerspaces as a contemporary and expanded manifestation of a ethos hacker, revealing specific ways of creation, collaboration and learning. This approach is related to the constant exercise of observing rethinking and reinventing through the direct action upon our more and more technology-mediated world. The investigation relies on discursive and theoretical contributions and on the empirical experience of participant observation with the Tarrafa Hacker Clube hackerspace, which is located in the Brazilian city of Florianopolis. We point out the importance in understanding the hackerspace movement through a historical, social and ethical standpoint. In this way, these issues are no longer purely technical and are being taken as opportunities for new ways of relating to the world.

Keywords: hackerspaces, ethos hacker, hacking, social appropriation of technology, technological collectives.

Introduction

An updated emphasis in participatory patterns of production and learning is changing our social realm. From the simple act of making developed by artists, artisans and hobbyists, the technologic augmented DIY became the prevailing metaphor for a variety of social and economic practices. These practices require extensive cultural transformations for which new spaces for action are conceived.

Hackerspaces are, in a simplified manner, community-operated physical places that afford sharing of tools, resources and knowledge. In these spaces, people can meet and work on their projects, often related to technology. They present themselves as one of several grassroots organizations (Schrock, 2014) associated to rapid changes in the context of information society. These transformations points towards new ways of relating with the world. Facing this increasingly technologically mediated reality the image of the hacker condenses different discourses, desires and expectations in contemporary imaginary.

The hacker ethos, which dates back to the 1960s in the university context of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology - MIT (Levy, 1994), relocates ideals of freedom and autonomy of the individual (Coleman and Golub 2008) in an era marked by transience and the emergence of new productive paradigms and models of knowledge construction. The hacking articulating this ethos can be seen as a direct and critical-creative approach (Busch 2008). It is a form of acting capable to be extended to multiple levels of the social field and different areas of knowledge (Busch and Palmås, 2006).

This paper aims to present hackerspaces as a contemporary manifestation that expands a hacker ethos, revealing specific ways of creation, collaboration and learning. This approach is associated with the constant exercise of rethinking and reinventing through the direct action. Our investigation relies on discursive and theoretical contributions and on the empirical experience of participant observation with the Tarrafa Hacker Clube hackerspace, in Florianopolis, Brazil.

We begin this exploration by establishing a historical context and pointing from its early origins into the further development of the global hackerspaces' phenomenon. Hereafter, we describe the process that led to the formation of the Tarrafa HC hackerspace in Florianopolis. Then, we analyze their practices and activities within the overall context of the movement that defines these spaces.

Accordingly, as architects, our interest rely in specific aspects raised by hackerspaces. We understand them as an extremely relevant reference in many levels that cross training and professional practice as well as our own attitude towards the contemporary world. Our partial perspective - contaminated in some degree by our experience as architects and members of a hackerspace - is the filter through which we seek to understand this movement.

Hackerspaces – A Movement Emergence

Hackerspaces, in similar settings to what we know today, emerged in Germany in the mid-1990s under the Chaos Computer Club’s (CCC) influence, an association of hackers among the oldest and largest in the world, founded in 1981. Among the first hackerspaces are the CCC’s local division, CCC Berlin, along with the c-base, both based in the capital. In 2006, following the German inspirations, the Metalab hackerspace was founded in Vienna, beginning the spread of these spaces in Europe. Those spaces followed the same principles, with a focus on building an open space infrastructure for social gathering and project development.

Fig. 1 - Metalab, 2012. Source: Mitch Altman (CC BY-SA 2.0) - Available at: <https://www.flickr.com/photos/maltman23/8260407658/>.

In 2007, those European hackerspaces shared their experience with a group of American hackers who carried out a trip to the international meeting Chaos Communication Camp in Germany. After the organized visits to various German and Austrian spaces, members of C4 hackerspace, from Cologne, presented the document Hacker Space Design Patterns (Ohlig et al, 2007). The document contained a set of general guidelines for the creation and organization of a hackerspace, developed by the Europeans from empirical learning. Back to the United States and stimulated by what they saw on the trip that became known as Hackers On A Plane (Tweney, 2009), several members of that group decided to found hackerspaces in their own cities. We can emphasize the NYC Resistor in New York, the HacDC in Washington and Noisebridge in San Francisco (Pettis et al, 2011).

In late 2008, the year that followed the Hackers On A Plane trip, the 25th Chaos Communication Congress (25C3) took place in Germany, with a panel Building an international movement: hackerspaces.org (2008). Several people representing different new hackerspaces reported the growth of these places, now seen as parts of an international movement. They also introduced the online platform of hackerspaces.org consisting of a wiki page, blog and mailing list, with the motto “build! unite! multiply!”. Since 2008 hackerspaces.org wiki keeps a register of hackerspaces around the world and currently (July 2014) has about 1000 listed spaces - spaces that consider themselves part of the movement, since the registration is free and done by the groups themselves.

The first hackerspace in Brazil, the Garoa Hacker Clube, appeared in 2010 in São Paulo after about a year of planning and discussions. Early discussions began in June 2009 and in the end of August 2010 a permanent physical space of 12m² in the Casa da Cultura Digital in São Paulo was inaugurated. Since February 2013, the Garoa HC is located in its new headquarters, a house in the Pinheiros neighborhood (Garoa.net wiki, 2013). The Garoa HC paved the way for the creation of several other hackerspaces in Brazil, including the Tarrafa Hacker Clube in Florianópolis.

Although the history presented may seem clear and objective, this line of events is a point of view that inevitably leaves out significant parallels and other past developments. Thus, we can identify a number of precedents of spaces and groups with similar conformations. Although they do not fully match this model, they certainly influenced in a decisive way and in many respects what would be this global movement. Aspects related to the hacker culture "technological" DIY, date back to amateur radio from the 1920’s (Galloway et al. 2004), through the '50s with the TMRC (Tech Model Railroad Club) model railroading enthusiasts at MIT. This group eventually transported the concept to the computing context (Levy, 1994). Coleman (2013) reports that the growth of this movement takes to a new context the practice of hardware hacking, already remarkably present in the Homebrew Computer Club activities in California in the mid-1970s. However, Grenzfurthner and Schneider (2009) argue that the first hackerspaces are directly connected to the countercultural protests of the 1970s post-hippie movement. They combined micro-political tactics or, in other words, the construction of tiny "new worlds" within the old world, seeking to create new relationships and spatial appropriations.

We can exemplify that, alongside the emergence of hackerspaces in Germany, the hacklabs also emerged more related to the tradition of squatting and media activism (Maxigas, 2012). With a remarkable ideological difference, Maxigas (2012) also points out that most hacklabs were part of an explicitly politicized scene. In Italy, the hacklabs emerged under the influence of the autonomist movement (Bazzichelli, 2008) while in Spain, Germany and the Netherlands, they were related mainly to anarchists movements (Yuill, 2008). From that period, while active, the Dutch hacklabs ASCII (Amsterdam Subversive Center for Information Interchange) and PUSCII (Progressive Utrecht Subversive Centre for Information Interchange) were especially relevant. In contrast, hackerspaces that have developed under the libertarian influence of the Chaos Computer Club did not necessarily positioned themselves openly about politics. People involved in both scenes probably consider their own activities as oriented towards the liberation of technological knowledge, but the interpretations of this "freedom" are divergent. In this sense, the genealogy of hackerspaces could also be seen from the point of view of hacklabs.

Recently, the designation makerspace has gained strength - especially in America. Although it is also often seen as a synonym for hackerspace, this change in denomination is actually a indicative of a greater association with the emerging maker movement (Anderson, 2012) rather than to a strictly hacker culture. The maker movement that Anderson (2012) refers is the junction between the DIY spirit, the sharing culture of the web and digital tools, reaching a surprising new global scale. Discussions on differences between hackerspaces and makerspaces have been initiated and in some cases include comparisons with other community spaces such as FabLabs and TechShops that also offer public access to shared equipment and tools (Cavalcanti, 2013). Despite the possible association of the term makerspace with the MAKE Magazine - already criticized for promoting the sanitization of the maker movement (Hertz, 2012) - differences between hackerspaces and makerspaces are not clear or consensual, and many of the involved make no distinction. However, FabLabs and TechShops have very specific origins and motivations, referring respectively to the academic and professional/commercial environments. Also with different characteristics, are medialabs and citizen laboratories, both dedicated to promoting digital inclusion from the access and training to the public, usually with the support of government (Sanguesa, 2013).

In general, under different patterns and denominations, backgrounds and goals, we are following the growth of a global trend of collaborative spaces for creating, working, learning and activism related to the democratization of digital culture.

However, we emphasize that, in the midst of this trend, hackerspaces have specificities associated with a hacker ethos that should be explored. In recent years this ethos begins to reach an increasing number of people from different areas, no longer restricted to undergrounds subcultures. We perceive an exploratory, creative and critical position in relation to technology and its relationship with society in practices and operations found in hackerspaces.

Analytical Overview

A precise understanding of what is a "hackerspace" does not exist even among people directly involved with the movement, which is reinforced by Mitch Altman, founder of Noisebridge in San Francisco. According to Altman (Oh, 2011), it is possible to recognize when you are inside one, but all are unique, as are unique the people who build these spaces. Schrock (2011) agree that individuals who attend hackerspaces cannot be uniformly classified, being quite heterogeneous in their motivations to use the space. According to this author, a collective identity defines the specificities of every hackerspace and is generated by its members’ momentary interests, their activities and common events.

Although consensus has not been reached, discussions on the issue within the community have made possible for Moilanen (2012) to list five general criteria on what to be a hackerspace means: (a) is owned and managed by its members in a spirit of equality; (b) non-profit organization and open to the outside world; (c) is a space where people share tools, equipment and ideas without discrimination; (d) has a strong emphasis on technology and invention, and (e) has a shared space (or is in the process of acquiring one) as the core of the community.

On the other hand, members and scholars seem to agree that hackerspaces can be understood as a "third place" (Building hackerspaces Everywhere 2009) (Moilanen, 2012) (Schrock, 2014). This concept defined by Oldenburg (1999) refers to the informal meeting spaces and informal connections outside home (first place) and work (second place), that facilitate and foster broader and more creative interaction.

Esther Schneeweisz “Astera”, member of the Viennese hackerspace Metalab, reminds that as “third places”, hackerspaces can manifest themselves in very different ways according to the interests of those involved. They have greater or lesser focus on areas such as hardware hacking; reverse engineering; electronics and microcontrollers; programming and computer security; technology and art; etc. On the other hand, Schneeweisz emphasizes that the activities are not limited to these examples, since hacking can be directed to any area. It is about a looking from a different perspective, rethinking and reinventing a particular topic. (Building hackerspaces Everywhere, 2009)

Eriksson (2011) identifies and categorizes some of the productive activities found in hackerspaces into three groups. The first group that he identified as "modification of closed systems” comprehends the traditional meaning of hacking, and basically refers to the understanding, modification and extension of a given system functionality. The second group "composition by simple means", refers to the creative process that makes use of basic components and elements (eg. sensors and actuators) often obtained from scrap and from other objects. As a third group of activities, "experimenting with open hardware and software" reflects the growing use of open source devices like Arduino and 3d printer kits for the developing of new projects.

However, hackerspaces are community spaces where different activities occur simultaneously, many of which could not be considered productive in the usual sense of the word. People share the space to interact, establish casual conversations or simply meet without any specific purpose. Rather than be seen as a means to accomplish previously defined goals, hackerspaces should be seen as places where goals, motivations and desires can be explored, discovered and built (Eriksson, 2011).

For Blankwater (2011), hackerspaces function as places of learning. Without a formal hierarchy but with a flexible horizontal structure every person is a potential sender and receiver of information: “Hackerspaces offer different modes of learning that involve being creative, searching for own sources, out-of-the-box thinking, decentralization, collaboration and mixing of disciplines.” (Blankwater, 2011, p.115)

The Tarrafa Hacker Clube

The Tarrafa Hacker Clube (Figure 2) constitutes today the only active hackerspace in Florianópolis, housing in its space events, workshops and regular open meetings. Its structure follows the trend initiated by spaces like c-base and Metalab, strongly incorporating references of american hackerspaces like Noisebridge and NYC Resistor and with great influence from the Brazilian Garoa HC. In its formation process, we can identify many common elements to other hackerspaces around the world. Among these elements, we can mention the conformation of a community, this eager for a space to establish collaborations, intense activity through mailing lists and a strong interest in joining the local community.

Fig. 2 - Overview of Tarrafa Hacker Club, 2014. Source: by the authors.

History

Tarrafa HC started out with the formalization of a small group through the creation of a mailing list in late November 2011. At the beginning of 2012 the mailing list raised a greater participation, with the entry of new interested people and the beginning of the search of a physical space and the dissemination of the project to the general community. A first lecture was held in March 2012 at the Federal University of Santa Catarina addressing the concept of hackerspaces and aiming to present the proposal to create such a space in Florianópolis.

The offer of lectures, workshops and courses in the first semester of 2012, was very important for the Tarrafa HC consolidation process as a group. The participation of some members in the International Free Software Forum (FISL) in Porto Alegre at the end of July 2012 allowed the meeting with participants from other hackerspaces in Brazil, as the Garoa HC of São Paulo and the then recently formed MateHackers from Porto Alegre. That event pushed the group to prioritize even more the realization of projects and activities, alongside the search for a proper headquarters, at the expense of association’s bureaucratic formalization aspects.

Therefore, in August 2012 the first collective project of Tarrafa HC called Beer Counter (Figure 3) was started, which involved the creation of a digital counter incremented by the touch of a button that holds the final value stored in its memory. To continue with the project and also to study and develop electroacoustic instruments, some meetings occurred weekly at the house of one of the members. From these meetings the first regular event of the group was created in the same month, the "Night of Reverse Engineering and Deconstruction" (N.E.R.D. - Noite da Engenharia Reversa e Desconstrução).

Fig. 3 - Beer Counter development meeting, 2012. Source: by the authors.

In the next September, the Tarrafa HC offered talks and workshops as part of the program of a university course called Ateliê Livre Tecnologias Interativas e Processos de Criação. This elective course was a design studio created in the curriculum of the Architecture and Urbanism undergraduate program of the Federal University of Santa Catarina with the goal to plan and construct projects of urban interventions using accessible technologies of physical computing. In mid-October 2012, the course took place in an available room in the old building at the Department of Architecture in order to allow a space for continued work for the students. In exchange for the permanent support to the discipline, which had a second edition in the following semester, the Tarrafa HC started to use that same space for other activities, like meetings and events, establishing a temporary base there. This collaboration with the design studio has been described in greater detail in a previous work (Mattos et al, 2013).

Currently the Tarrafa HC remains in that space, sharing it with the academic project Laboratory in Emerging Technologies and Innovation. The room has 46 square meters, divided between work and meeting space, a wood workshop, a 3d printing area, deposit for materials and scrap and a small entrance hall (Figure 4). We note that this setting is always going through changes to better accommodate the activities developed, which gives dynamism to the space.

Fig. 4 - Floor plan of the Tarrafa HC, 2014. Source: by the authors.

We should also point out that the Tarrafa HC online activities accompanied its growth. Currently the mailing list has 285 subscribers (July 2014) and includes participants from other hackerspaces and individuals interested in discussions, even if not directly involved with activities that take place in the space. The hackerspace is also present in hackerspaces.org wiki, and many of its most active members have participated in the mailing list of the platform and on lists of other spaces, which promotes an important exchange of experiences and ideas.

Activities e Practices

The activities, initially centered in electronics by the influence of some members, were seeking practical experience as opposed to the high theoretical level of the academic environment. Programming was also present from the early activities, but rather linked to electronics through the relationship with microcontrollers and physical computing. These practices are also in conjunction with the popularization of the Arduino platform and the open hardware movement. They are also in line with those developed in other spaces like the NYC Resistor, which started its activities with study group in microelectronics (Pettis et al, 2011).

From those interests have arisen the aforementioned workshops and the first regular and frequent event, N.E.R.D., based on the reverse engineering method that seeks to understand systems from the opening and analysis of its elements and connections. During the N.E.R.D.s, a closed object is chosen to be dismount and investigated from its parts, its operation and its creation process, as well as from the exchange of ideas and knowledge among the participants. Eventually such activity can lead to the modification of the object or system, changing it for other purposes.

This attitude oriented to direct intervention associated with hacking (Busch, 2008) was gradually expanding to other areas as sewing, urban agriculture (Figure 5) and art & technology. This is not an exclusive feature of this hackerspace, but a general condition related to what Blankwater (2011) points out as the mindset associated with hacking practiced in these spaces. Tarrafa HC currently has sewing machines, 3D printers, and many tools and materials obtained through donations.

Fig. 5 - Sewing and urban agriculture activities, 2014. Source: Tarrafa Hacker Clube.

Another worth mentioning activity is Make: Electronics (Figure 6), a regular series of meetings that aims to promote the easy learning of electronics. The meetings follow the book of same name by Charles Platt (2009), in which knowledge about electronics are developed by participants in an exploratory way through experiments. Each meeting features "tasks" or challenges using simple and accessible resources. Of a similar character is the study group aligned with free software that develops their meetings following the Linux From Scratch (LFS) method, a series of step-by-step instructions for building a Linux system on their own, entirely from source code. During the process that also occurs in an exploratory mode, participants seek to learn about the workings of computer operating systems.

Fig. 6 - Make: Eletronics Meeting, 2013. Source: Tarrafa Hacker Clube.

Among the projects developed at the Tarrafa HC we can highlight the Revolta da Antena (Revolt of the Antenna), carried out during the popular mobilizations that took the streets across Brazil between June and July 2013. Inserting itself in the context of free media and live independent broadcasting, the project intended to make a contribution towards creating and offering a framework of free internet network. The availability of wireless internet access for the protesters occurred through the creation of access points connected in a mesh network. The system structure was nothing more than battery powered routers installed in helmets that were transported by volunteers protesters called "anteneiros" connected to each other and to available access points on the path. The project was built with the participation of many people in a short period of time, articulated by the creation of a Facebook group. Contributions were made in the technical aspects like the development of the software used and the assembly of the equipment, the development of physical and digital posters, the internet campaign for opening up private networks, the project documentation, among others. This project received considerable attention in online media and social networks both local and national.

Revolta da Antena was essentially a collaborative, community oriented and libertarian project, both in its process of development as in the way it entered the public space of the city, proposing and modifying territorial relations. What we can identify, in specific cases such as the project Revolta da Antena, is a synergy that combined different aspects of a social and political context, individuals interested and engaged with a technical spatial infrastructure, in this case, the hackerspace Tarrafa HC. Not all projects have achieved such range, but we emphasize that initiatives of this nature reinforce the transformative potential of hackerspaces.

Discussion

Some aspects regarding the operation of the Tarrafa HC shown to be particularly relevant in the context of this discussion. We realize that our experience made possible to find common elements with the other hackerspaces, contributing to the understanding of these as a grassroots contemporary social phenomenon linked to access and popularization of technology. Therefore, we assumed hackerspaces as expanded manifestations of a hacker ethos. The ethos brings about values and practices of creation, collaboration and learning, prioritizing exploratory, free and horizontal processes and actions, as opposed to the systematic and hierarchical model, typical of formal institutions.

Beyond autonomy and appreciation of freedom, the hackerspaces reinforce aspects such as collaboration, exchange of experiences and sharing of resources, while also incorporating other influences such as the maker and DIY culture and the open source movement. In the process, these community spaces combine and trespass several areas - such as engineering, computer science, natural sciences, art, design, and architecture, among others - through the interests, prior knowledge and experience brought by the people involved. However, rather than reaffirming roles, such individuals are imbued with a questioning spirit that often expands the boundaries of their own areas of origin.

In our view, hackerspaces also fit into what Thomas and Brown (2011) refers as a new culture of learning. According to the authors, to cultivate such learning form, we need the combination of two elements: the first is access to the information network and virtually infinite resources, and the second one deals with the existence of a delimited environment that promotes complete freedom within its limits catalyzing the creation and experimentation.

It is also important to note that these structures rely on local communities and are strongly bound to physical spaces provided with material resources. On the other side, they also need a virtual global network that strengthens themselves as a movement and allows the information and experience exchanges, both in the form of common projects and activities as good practice recommendations for managing these spaces. Hackerspaces are trans-local structures (Eriksson 2011). We see that these structures would not be possible without the ubiquity of the Internet, which enabled the formation of collaborative models of empowerment and innovation. Standing between the physical and the digital we can recognize in hackerspaces an essentially hybrid nature of these spaces (Caldwell et al, 2012).

Conclusion

The challenges of the information society requires critical positioning as well as new processes for creation, collaboration and learning. The form of organization and practices associated with hackerspaces have great potential to affect many different areas of knowledge. Such spaces have challenged values defended by consolidated professional and academic structures, with revealed resistance to adapt to the complex social reality. Thus, they have provided us important clues towards redirecting the production processes and contemporary education.

On the other hand, we also understand that hackerspaces, as critical appropriation spaces, currently go through a mainstream assimilation process. In this process, there is the possibility of sanitizing and de-ideologization to make it accessible and palatable. This is natural, considering a typical mode of operation within this assimilation logic: transforming processes into products, services and goods. This procedure excludes any critical and subversive agenda, like the superficial and merely imagery cultural assimilation of countercultural movements of the 60s or 80s' punk movement. The challenge, where rests our particular interest, is to identify and eventually to be able to transport to other areas, some aspects of hackerspaces that actually are transformative and revolutionary.

Some practical and interesting elements found in hackerspaces begin to emerge also through other ways, as regards to sharing of spaces and resources for working and production, like the FabLabs, TechShops and coworkings, or even collaborative models of financing and ownership such as crowdfunding and open source. These models have already visible and even irrefutably affected architecture practice and the building of spatial relationships. However, even by sharing these practices and elements, we identified that one of the fundamental aspects of hackerspaces is precisely the most difficult to assimilate. We believe that this factor, understood here as the hacker ethos, is the key element that gives meaning, questions and transforms our relationship with the world.

At this point, our position as architects, participants in a very specific social ecosystem as the hackerspace Tarrafa Hacker Club, have leaded us to ask: what the architects - as well as designers, artists, engineers and other professionals - can apprehend from this type of manifestation, or; what are the effective contributions of each field of knowledge in this contemporary scenario. Questions still without clearly delineated answers, but that push us to go deeper in that process of deconstruction of our images and consequent relevance.

Hackerspaces are systems that de-structure certainties where, as in the CCC Berlin hackerspace, “things are always under scrutiny, under discussion, under attack. Nothing is taken for granted and everything needs to be revisited, taken apart, looked closer at.” (Pettis et al. 2011, p. 7).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge CAPES (Ministry of Education) and CNPq (Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation) for their support to this research. The authors are also grateful to the Tarrafa Hacker Clube members, for providing the necessary support for this study.

References

Anderson, C. 2012. Makers: the new industrial revolution. New York: Crown Business.

Bazzichelli, T., 2008. Networking: the Net as artwork. Arhus: Digital Aesthetics Research Center.

Blankwater, E., 2011. Hacking the field: An ethnographic and historical study of the Dutch hacker field. Sociology Master’s Thesis. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Building an international movement: hackerspaces.org. 2008. [Online] 25th Chaos Communication Congress. Available at: <http://ftp.ccc.de/congress/25c3/video_h264_720x576/25c3-2806-en-building_an_international_movement_hackerspacesorg.mp4> [Accessed 30 May 2013].

Building Hackerspaces Everywhere. 2009. [Online] BruCON 2009. Available at: <http://vimeo.com/6911866> [Accessed 23 May 2013].

Busch, O. von and Palmås, K., 2006. Abstract hacktivism: the making of a hacker culture. London; Istanbul: Open Mute.

Busch, O. von, 2008. Fashion-able: hacktivism and engaged fashion design. Göteborg: School of Design and Crafts (HDK), Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, University of Gothenburg.

Caldwell, G. et al., 2012. Towards Visualising People’s Ecology of Hybrid Personal Learning Environments. In: Proceedings of the 4th Media Architecture Biennale Conference: Participation. MAB ’12. New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp.13–22.

Cavalcanti, G., 2013. Is it a Hackerspace, Makerspace, TechShop, or FabLab? MAKE[Online]. Available at: <http://blog.makezine.com/2013/05/22/the-difference-between-hackerspaces-makerspaces-techshops-and-fablabs/> [Accessed 24 May 2013].

Coleman, E.G. and Golub, A., 2008. Hacker practice: Moral genres and the cultural articulation of liberalism. Anthropological Theory 8(3), pp.255–277.

Coleman, E.G., 2013. Hacker (Forthcoming, The Johns Hopkins Encyclopedia of Digital Textuality, 2014) [Online]. Available at: <http://gabriellacoleman.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Coleman-Hacker-John-Hopkins-2013-Final.pdf> [Accessed 5 February 2014].

Eriksson, M., 2011. Labbet utan egenskaper [Online]. Available at: <http://blay.se/papers/labbet.pdf> [Accessed 17 May 2013].

Galloway, A. et al., 2004. Panel: Design for Hackability. In: 5th conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques. Cambridge, MA: ACM Press.

Garoa.net.br Wiki, 2013. História: Garoa Hacker Clube. [Online]. Available at: <https://garoa.net.br/wiki/História> [Accessed 16 March 2014].

Grenzfurthner, J. and Schneider, F.A., 2009. Hacking the Spaces [Online]. Available at: <http://www.monochrom.at/hacking-the-spaces/> [Accessed 28 April 2012].

Hertz, G., 2012. Interview with Matt Ratto. In: Critical Making: Conversations. Critical Making. Hollywood. California USA: Telharmonium Press, pp.1–10.

Levy, S., 1994. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. New York, N.Y.: Dell Pub.

Mattos, E.A.C. et al., 2013. Tecnologias Interativas e Processos de Criação: Experiências de Aprendizagem Transdisciplinares Associadas a um Hackerspace. In: Knowledge-based Design - Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the Iberoamerican Society of Digital Graphics. Valparaíso, Chile, pp.572–576.

Maxigas, 2012. Hacklabs and Hackerspaces: Tracing Two Genealogies. The Journal of Peer Production (Issue #2: Bio/Hardware Hacking). Available at: <http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/peer-reviewed-papers/hacklabs-and-hackerspaces/>.

Moilanen, J., 2012. Emerging Hackerspaces–Peer-Production Generation. In: Open Source Systems: Long-Term Sustainability. Springer, pp.94–111.

Ohlig, J. et al., 2007. Hackerspace Design Patterns [Online]. Available at: <http://hackerspaces.org/images/8/8e/Hacker-Space-Design-Patterns.pdf> [Accessed 30 May 2014].

Oh, J., 2011. Science on the SPOT: Open Source Creativity – Hackerspaces [Online]. Available at: <http://science.kqed.org/quest/video/science-on-the-spot-open-source-creativity-hackerspaces/> [Accessed 3 April 2014].

Oldenburg, R., 1999. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. 3rd ed. Marlowe & Company.

Pettis, B. et al., 2011. Hackerspaces @ the_beginning (the book) [Online]. Available at: <http://hackerspaces.org/static/The_Beginning.zip> [Accessed 17 May 2014].

Platt, C., 2009. Make: Electronics. 1st edition. Sebastopol, Calif.: Make.

Sanguesa, R., 2013. La tecnocultura y su democratizacion: ruido, limites y oportunidades de los Labs. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnologia y Sociedad 23(8), p.259.

Schrock, A.R., 2011. Hackers, Makers and Teachers: A Hackerspace Primer (Part 1). Available at: <http://andrewrschrock.wordpress.com/2011/07/27/hackers-makers-and-teachers-a-hackerspace-primer-part-1-of-2/> [Accessed 20 September 2013].

Schrock, A.R., 2014. Education in Disguise: Culture of a Hacker and Maker Space. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies 10(1). Available at: <http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0js1n1qg#page-8> [Accessed 1 March 2014].

Thomas, D. and Brown, J.S., 2011. A new culture of learning: cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. Lexington, Ky.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Tweney, D., 2009. DIY Freaks Flock to ‘Hacker Spaces’ Worldwide | Gadget Lab | Wired.com [Online]. Available at: <http://www.wired.com/gadgetlab/2009/03/hackerspaces/> [Accessed 17 May 2013].

Yuill, S., 2008. All Problems of Notation Will Be Solved By the Masses [Online]. Available at: <http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/all-problems-notation-will-be-solved-masses> [Accessed 28 July 2014].