Arquitetura e urbanismo participativos: uma gênese

Sylvia Adriana Dobry é Arquiteta, Doutora em Arquitetura. Pesquisadora do Laboratório Paisagem, Arte e Cultura (LabParc) da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo. Foi professora no Taller Total da Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo da Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. Estuda a relação desenho-percepção-criação, educação, projeto participativo, e história da Arquitetura e Urbanismo.

Como citar esse texto: DOBRY, S. A. Arquitetura e urbanismo participativos: uma gênese. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 18, 2019. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=4&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 15 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 28 DE AGOSTO DE 2018

Resumo

Neste artigo, de caráter prioritariamente memorialista, estuda-se o projeto participativo de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, metodologia e valor, como processo e arte, criação coletiva e interdisciplinar. Nos casos analisados, que relacionaram poder público, comunidades, ensino e ambiente, realizados entre as décadas de 1970 e 1990, em São Paulo-Brasil e Córdoba-Argentina, conectam-se duas ideias fortes – participar e colaborar –, carregadas de sentido dialógico, visando a nortear a discussão sobre cada uma delas, sobre o tema, e sobre aquilo que as conecta, ou pode conectar. A produção de lugares e paisagens, produto e processo da ação dos homens e da atividade criadora, contém a condição de alienação a que está sujeita a produção de todo objeto no interior da propriedade privada. O dilema do valor de uso - valor de troca - revela a contradição arte-mercadoria, que, como todo produto no sistema capitalista de produção, se separa do artista que cria, transformando-se em mercadoria. Procura-se encontrar brechas para superar essa contradição, entendendo-se que da relação arte-economia-política pode surgir a possibilidade de superar a alienação. Isto permitiria, junto aos habitantes dos lugares, a abertura para a atividade criadora, abrindo portas à discussão democrática de projetos urbano-paisagísticos nesses lugares, revelando potencialidades.

Palavras-Chave: Participação, Gênese, Arquitetura e urbanismo

1 Arquitetura e urbanismo: participação

A palavra participar (lat. part+cipere) é composta pelas noções de “parte, ser parte de” (lat. part), e “agarrar, tomar” (lat. cipere), indicando uma ação voluntária e decidida. A palavra colaborar une o sentido do latim laborare,“trabalhar, sentir dor, cansar-se”, à condição coletiva dada pelo prefixo co, “juntos, com”. Maria da Gloria Gohn (1991) diferencia a participação formal da real: a primeira possui um projeto institucionalizador e a segunda contém uma concepção transformadora, na qual a gestão popular revela conflitos existentes, descobrindo caminhos para câmbios desejados, desde a raiz dos problemas.

Há convergência entre educação com objetivo participativo e urbanismo participativo, ao buscar metodologias permitindo a inserção nos lugares e sua apropriação, desenvolvendo criatividade, imaginário cognitivo e discussão democrática, construindo um sentido de pertencimento entrelaçado com a construção de cidadania.

Os casos analisados, realizados entre as décadas de 1970 e 1990, em São Paulo-Brasil e Córdoba-Argentina, relacionaram poder público, comunidades, ensino e ambiente. Permitiram perceber que o processo participativo, permeado de afeto pelo lugar, é ligado às lutas pelos direitos cidadãos, contribuindo, muitas vezes a partir da resistência e insurgência, com um desenvolvimento urbano que prioriza o sentido de pertencimento.

Ao conhecer o projeto “Uma Fruta no Quintal”, em 1996, surpreendeu-me a simplicidade da proposta: arborizar a cidade por meio de plantio realizado pelos habitantes, principalmente nas escolas. O desenvolvimento da proposta estava na corrente sanguínea da organização escolar existente, abrindo espaço de discussão para o tema cidade, cada vez mais longe da natureza, insensível, violenta e selva de pedra. A palestra pronunciada pelo coordenador geral, Raul I. Pereira, apresentou o projeto em um momento em que me interrogava sobre o significado do ser arquiteto, porque no meu percurso profissional, muitas vezes, ouvi frases tais como: “não se preocupe, arquiteta, com a fachada desse prédio, é para os pobres” ou “não importa se a cama não couber no dormitório, é só para os pobres”.

Por outro lado, de forma simplista, acreditava que o desenhar desenvolve a percepção e aguça o olhar, e que dar oportunidade às pessoas para desenvolver o seu desenho, possibilitaria uma melhor percepção dos seus lugares de convívio, das vantagens de preservar as árvores, os rios etc. Eu confiava mais na eficiência de fazer desenhos do que nos discursos para despertar a sensibilidade e a humanidade.

Assim, a resposta ao problema de como resolver a educação ambiental de jovens e crianças: “a saída encontrada foi a arte” (PEREIRA, 1996, p. 1) sintetiza a ideia central que permeia esta reflexão: no projeto participativo se constrói, num processo dialético, a relação entre economia, política e arte, criando um instrumento para a ação contra a alienação (ANDERSON, 1999).

Percebi, no contexto desse projeto, que fazer arte nas escolas, desencadeando e incentivando reflexões sobre a cidade e identidade dos envolvidos, contribui para desenvolver a apropriação de seus lugares. Plantar árvores em um ato realizado pelos moradores, após um processo de discussão e reflexão através da arte, possibilitou sua transformação numa dimensão maior: fazer parte da construção do sentimento de pertencer.

Assisti a um dos eventos numa escola em Diadema, localizada num bairro de tijolos “baianos” sem acabamento, abarrotado de construções, cimento e terra vermelha, sem áreas verdes. Notavam-se muitas edificações de quatro andares em lotes estreitos, de não mais de cinco metros de largura. Lembrei da imagem do filme “Pixote”, a fealdade da periferia, a pobreza, lugares quase sem árvores. Como reminiscência de um passado rural, muito raro, podia-se contemplar um rancho de pau-a-pique, em um extenso terreno, com cavalos, patos e algumas árvores. A escola, com muitas grades, pisos de cimento, terra vermelha, grama rara, taludes erodidos pela chuva e poucas árvores, plantadas há pouco tempo, por ocasião do projeto. Notei a alegria da escola que estava em festa: crianças e adolescentes, os alunos sorridentes, exaltados e deslumbrados. Os docentes, a maior parte mulheres, se esforçando, preocupados, mas contentes. Nos pátios, em frente ao palco, ao ar livre, detrás das grades, em pé, uma multidão de pais, tios e avós risonhos e orgulhosos de ver seus filhos, jovens e crianças da periferia, convertidos em “astros” no palco escolar. O evento, culminação do período de reflexão e estudo sobre o meio ambiente, era o momento em que cada classe apresentava a questão por meio da arte.

Inicialmente, o coordenador perguntou: “Quem gosta de futebol? Para qual time torce?” A partir de questões simples, entrava-se no assunto central: “A cada dia, uma área de florestas correspondente a dois campos de futebol é destruída no Brasil”. Depois, principiaram as apresentações dos alunos e docentes, até a ocasião da entrega de mudas de árvores frutíferas.

Nessa festa, tomava parte também uma dupla de palhaços, esperados com expectativa. Uma garotinha teimava em dizer que palhaços eram de papel e que não existiam, porém, desafiada, tocou-os com todo cuidado e, surpresa, falou: “são de verdade! São de carne, como nós!” O sentimento dessa menina acordou-me para inquietações intensas, fazendo-me pensar sobre a grande distância que afasta a periferia das expressões artísticas, ainda que sejam populares, como o circo ou o teatro. Pensei em quanto esse contato fica restringido a uma pequena tela de televisão, na qual atores longínquos, fictícios, “de papel”, tomam o lugar da arte no dia a dia.

Observei que, muitas vezes, professores assumiam o lugar dos alunos, desenhando por eles, como idealizavam o desenho das crianças, porém aprimorando mais. Perguntava-me por que: quiçá eles tivessem o sentimento de serem pressionados para que sua turma aparecesse melhor. Mas, ao tomar o espaço do aluno, incluíam-se no círculo multiplicador da baixa auto-estima, já que, desconfiando de sua própria competência como educadores, geravam nos alunos, inconscientemente, o sentimento de não serem capacitados para fazer algo bem feito. Diversos educadores, no processo, se depararam com estudantes que desenvolveram habilidades que não suspeitavam ter, nesses casos, manifestando euforia e entusiasmo. Professores de matemática participavam de corais, de peças de teatro, docentes de biologia faziam maquetes: o projeto “Uma Fruta no Quintal” abriu a possibilidade de sair das caixinhas isoladas para participar de um todo integrado, readquirindo capacidades e potenciais.

Percebi, nesse projeto, a possibilidade de acender caminhos para que as pessoas conseguissem reconquistar em si próprias questões intrínsecas ao ser humano, como, por exemplo, dançar, cantar, desenhar. Atividades que lhes tinham sido arrebatadas pela diminuição da carga horária reservada ao ensino da arte e também pela transformação da arte em mercadoria.

Perguntei-me sobre a força que teria essa arte truncada para desvendar as contradições do mundo. A evidência de, na rede escolar, reunir pessoas de diversas idades, classes sociais e o ecoar amplificador das reflexões ali formadas, oferecia ao projeto a possibilidade de difundir contribuições sobre a cidade de modo participativo, com efeitos multiplicadores, submerso no cotidiano.

Ingressei no projeto, desenvolvendo o tema “Percepção do espaço através do desenho”. Inicialmente, as oficinas realizadas se dirigiam a adolescentes, devido à experiência como professora da FAU, da Universidade Nacional de Córdoba. Depois desenvolvi oficinas com docentes. Este processo me remeteu a experiências de que participei anteriormente: o Taller Total, na FAU-UNC; a formação da Associação de Docentes de Arquitetura e Urbanismo (ADAU), incluída na Federação de Associações dos docentes Universitários (FADU), Argentina, nos anos 1970; e o desempenho desses organismos, unindo docentes de primeiro e segundo graus, nas ações por melhores condições de trabalho e de ensino. Também as escolinhas de política que faziam parte da resistência à ditadura argentina, após o golpe militar de 1976, vinculando docentes de todos os níveis de ensino.

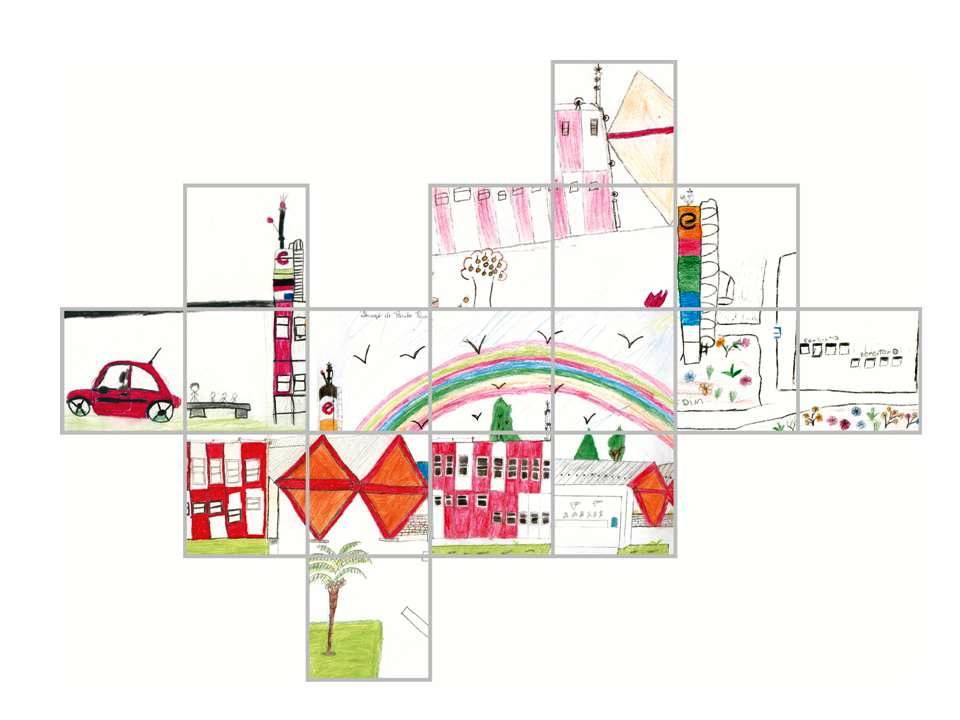

A lembrança dessas experiências me deu confiança para iniciar, nesse projeto, mais de vinte anos depois, um trabalho com professores da rede de ensino municipal e estadual. Aceitei o desafio de trabalhar com crianças, considerando que a equipe me ofereceria respaldo. Foi enriquecedora a experiência de ampliar nessa faixa etária a percepção dos lugares, por meio da realização de percursos, brincadeiras, desenhos e outras formas de arte (Fig. 1). “Uma fruta no Quintal” atuava como espinha dorsal, agregando projetos de diferentes secretarias e possibilitando a interdisciplinaridade e interação entre elas. Nas reuniões, o trabalho da equipe garantia que não se compusesse uma “colcha de retalhos”, mas que todos os projetos das diversas secretarias, fluíssem para o tema geral, que os incluía: a questão ambiental. De tal forma, aparecendo, inicialmente, como um projeto simples para plantio de árvores, integrava e enraizava questões como poluição, lixo, violência, trânsito, sexualidade, nutrição etc. e compreendia, como eixo central, a possibilidade de, por meio da arte, abrir os olhos para o lugar.

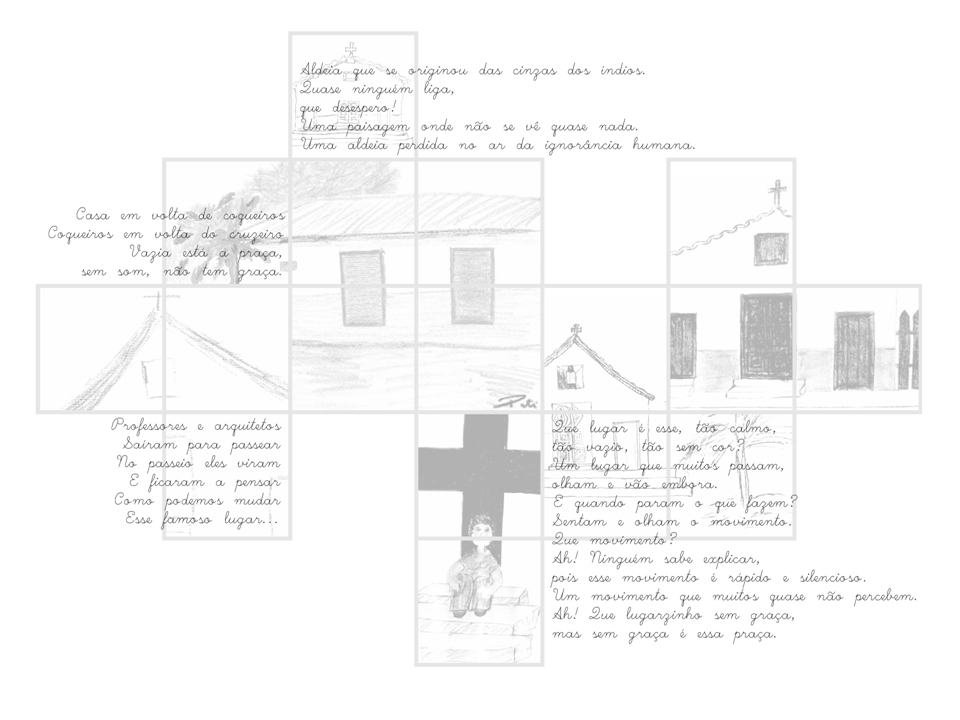

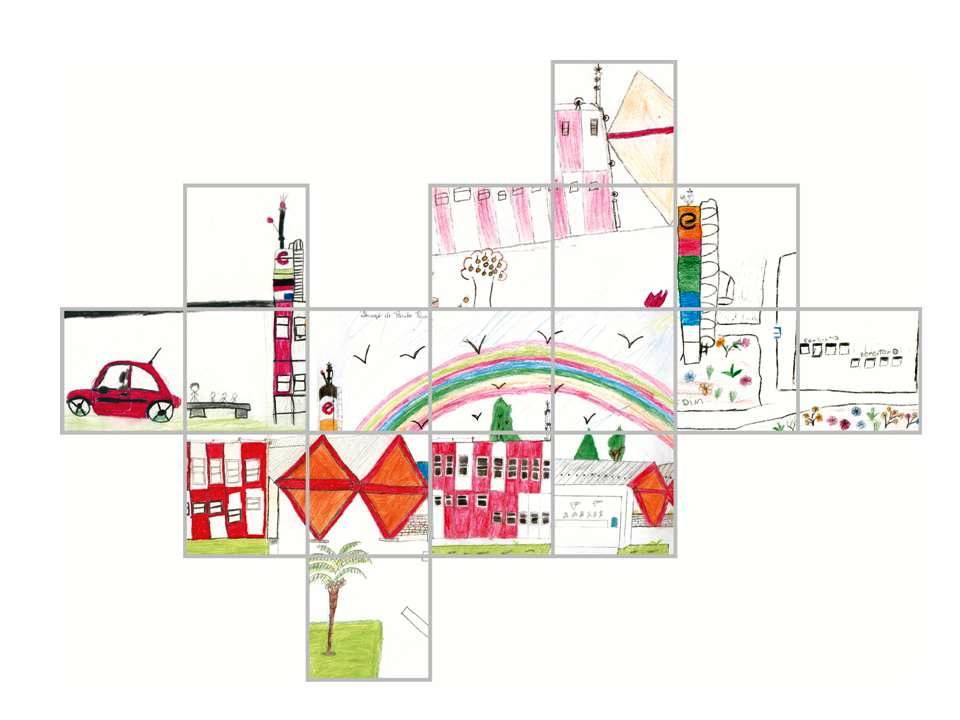

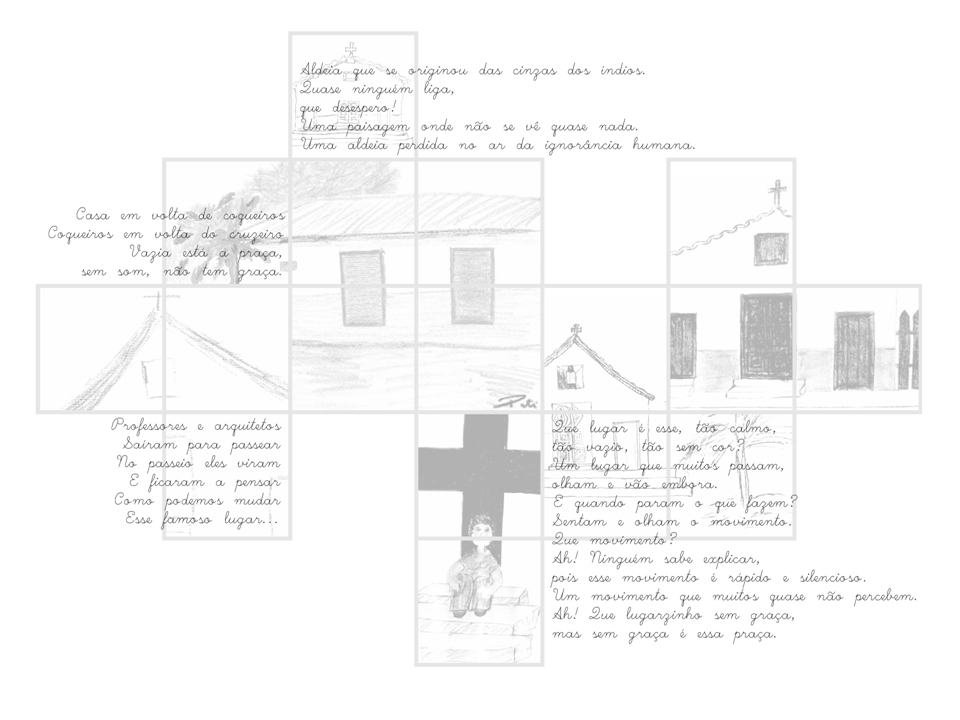

Fig. 1: Desenhos produzidos nas oficinas com crianças em Diadema, no contexto do projeto. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal da autora.

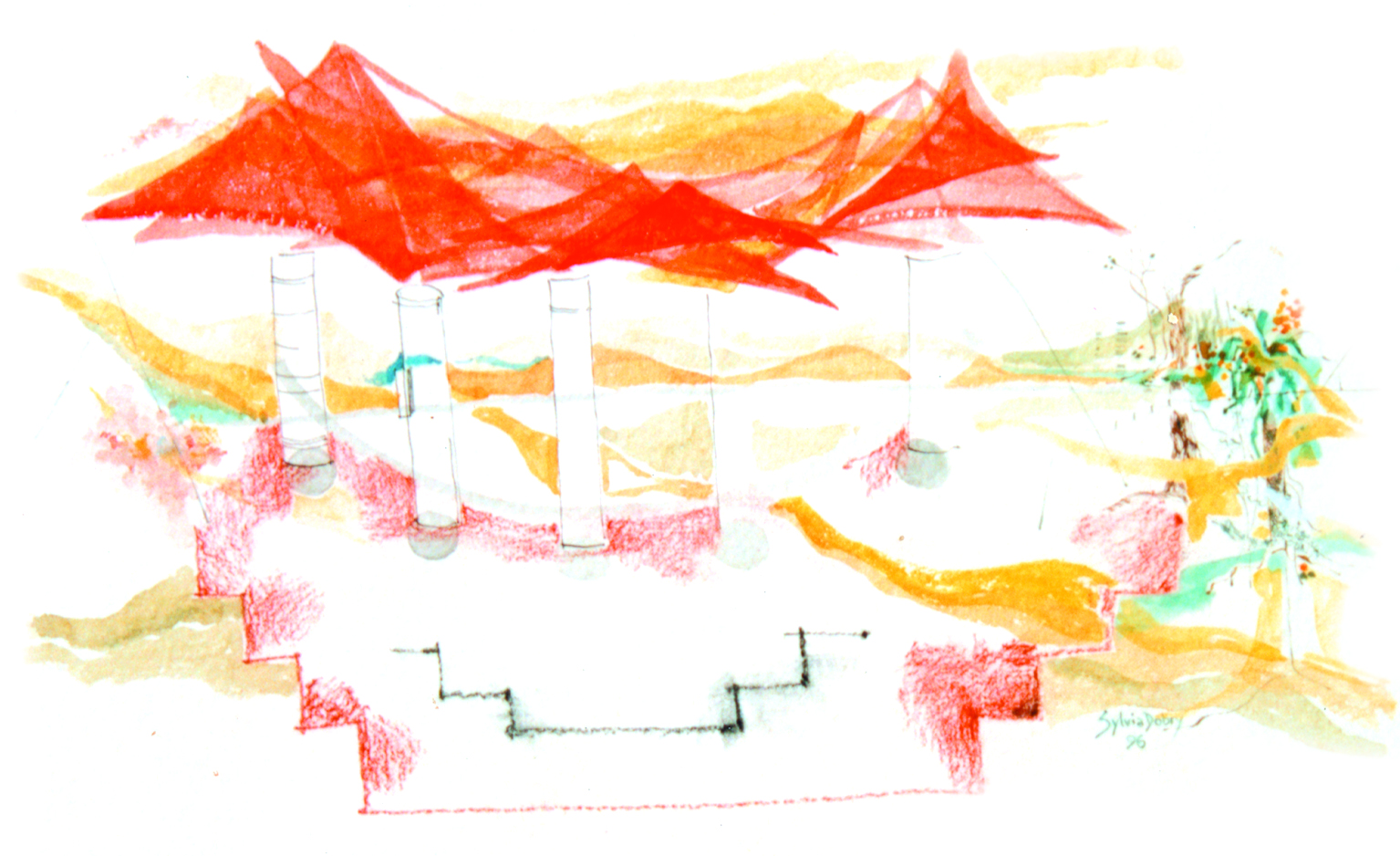

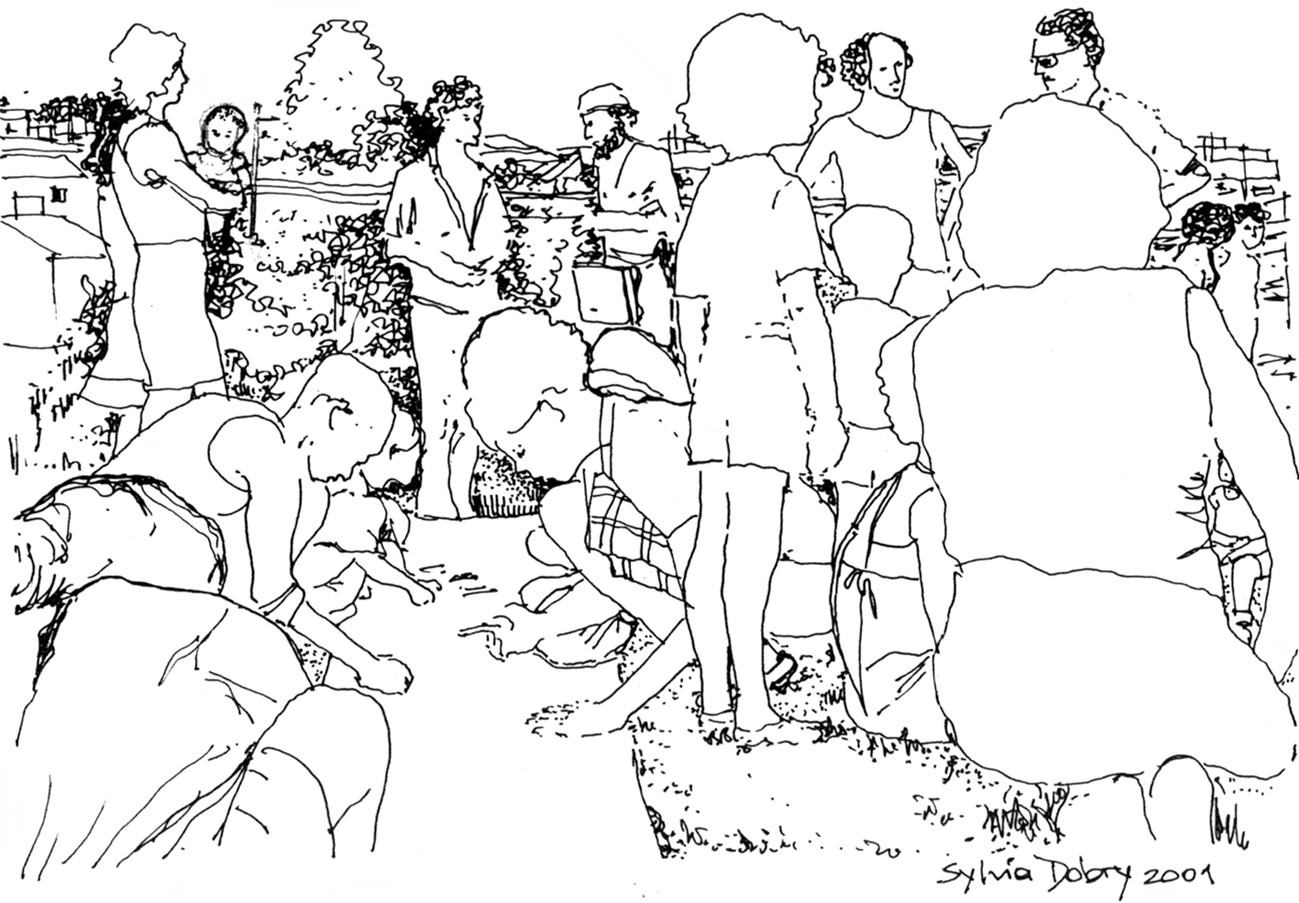

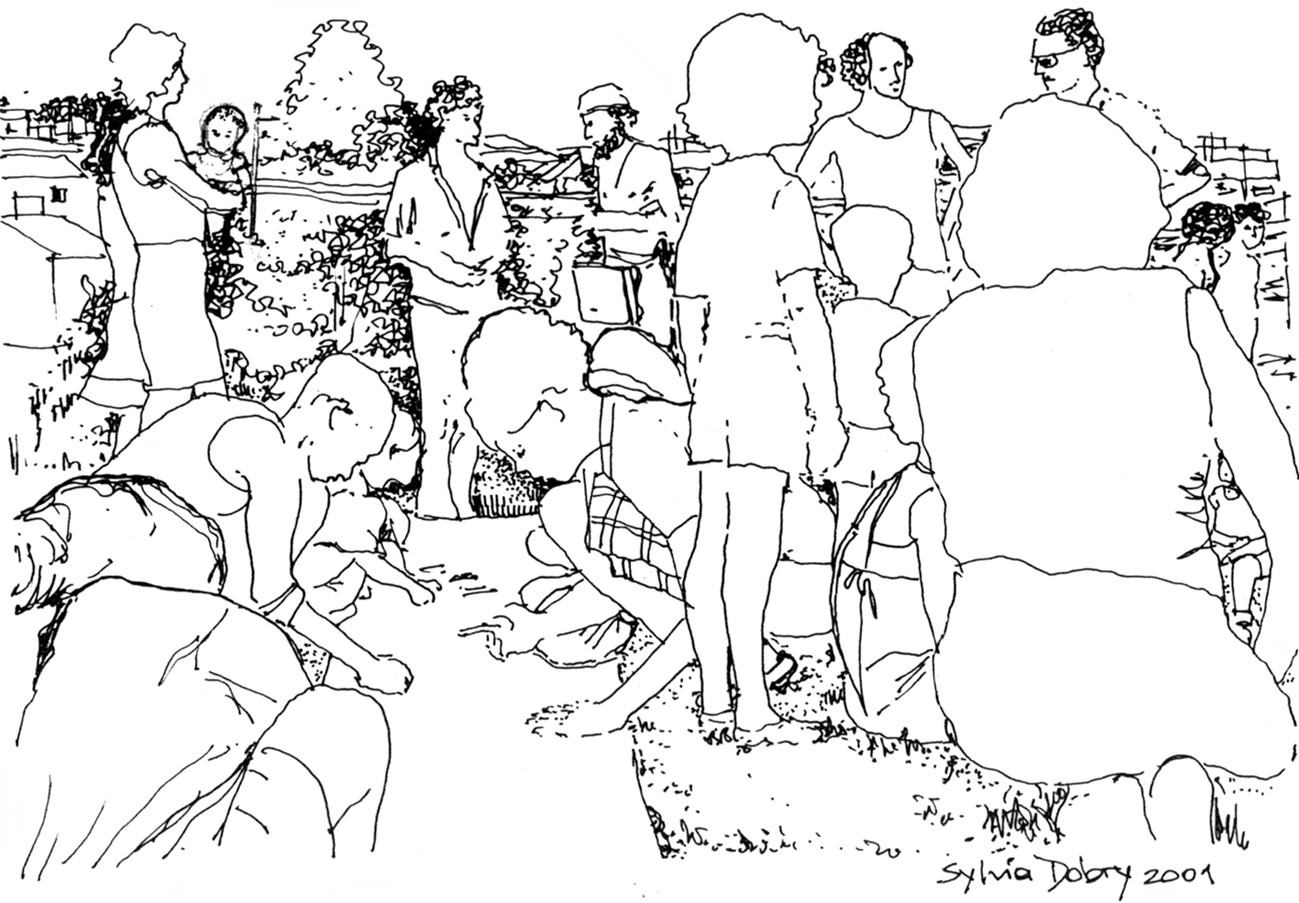

No decorrer do projeto “Uma Fruta no quintal”, como resultado da interação com crianças, adolescentes e professores das escolas de Diadema, também minha própria linguagem artística foi modificada (Fig. 2).

Iniciado na Rede Municipal de Ensino de Diadema, acumulando experiências e com efetivação de parcerias entre Prefeitura e Estado, o projeto desenvolveu-se muito e as escolas municipais e particulares solicitaram sua inclusão, no segundo semestre de 1996, para o que contribuiu a divulgação realizada pela TV e jornais. O prazo era curto para atendê-las e resolveu-se realizar oficinas em conjunto com os professores.

Perdia-se o contato direto com os alunos, mas, por outro lado, o intercâmbio com os docentes – aos quais se somavam funcionários e pais de alunos – foi enriquecedor, possibilitando apreender melhor seu ponto de vista e a estrutura escolar no seu cotidiano. Apresentando-se como desvantagem, a situação deu abertura a possibilidades para experiências futuras, como por exemplo, o Estudo do Meio na Aldeia de Carapicuíba, associado à elaboração do projeto de um parque, concretizado no ano 2004. Além desse, outros projetos de teor participativo, tais como o Parque Pinheirinho d’água e o projeto “Tudo em Volta”, em Santo André, desenvolvidos junto à equipe interdisciplinar do Laboratório de Pesquisa e Ensino em Ciências Humanas, da Faculdade de Educação, da USP (LAPECH-FE USP). Professores participantes das oficinas em Diadema, no projeto “Uma fruta no Quintal”, indicaram essa equipe que “coincidia com as mesmas ideias” e que desenvolvia, em especial, Estudos do Meio em forma interdisciplinar, dando apoio a professores da Rede Municipal e Estadual, coordenado pela Profa. Dra. Nidia Nacib Pontushka, o que permitiu essa conexão.

Em 1997, participei do estudo projetual para a implantação de projeto de revitalização urbana na Aldeia de Carapicuíba, em São Paulo. Acadêmico, no começo, alongou-se para fora desses limites, incluindo um projeto de urbanização e intervenção paisagística no lugar. Na reunião inicial, a Profa. Dra. Nidia Nacib Pontushka sintetizou o histórico do Estudo do Meio, metodologia que institui uma forma de ensino em que todos participam (alunos, professores, diretores, funcionários, moradores, pais, familiares) e a escola não é vista como ambiente isolado. Nascida no início do século XX da rebeldia anarquista, a metodologia recusa a sala de aula como hegemônica e enfatiza a observação direta da realidade como fonte primordial de conhecimento (Fig. 3). Outro aspecto importante: esse método, interativo, pode criar expectativas que sugerem pensar sobre o retorno do projeto para o grupo comunitário.

Fig. 3: Desenho e poesias de crianças - Escola da Aldeia de Carapicuíba. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal da autora.

A interação com outras formas de representação do mundo, através das oficinas com professores da escola da Aldeia de Carapicuíba resultou em formas novas de representação no processo criativo da autora (Fig. 4). Estas experiências ratificaram que um dos mananciais mais importantes para a construção do conhecimento se fundamenta na apropriação dos lugares de vida. Esta relação é balizada em múltiplos textos de Paulo Freire, referência forte para a Profa. Dra. Nidia Nacib Pontushka e para a equipe do LAPECH – FEUSP, bem como para Maria Saleme de Burnichon, que dirigia a equipe de psicopedagogia do Taller Total, nos anos 1970-1975, em Córdoba, na Argentina. Pode-se realçar a participação ativa dos alunos como resultado da ligação entre vida e escola. Só dessa forma é possível uma pedagogia libertadora, especialmente ao considerar que a relação educativa se dá sempre entre pessoas que representam o complexo social e não só entre indivíduos isoladamente, assinalando a existência de uma conexão entre o desenvolvimento individual e social.

Existe um modo coincidente de ver o mundo entre a construção de conhecimentos e a construção de lugares e paisagens, o que permitiu detectar algumas analogias importantes para o aprofundamento desta reflexão. Entre elas, a relação entre a comunidade e seu ambiente entendida como processo dinâmico permeado de afeto pelo lugar e ligado às lutas pelos direitos de cidadania. Há uma inter-relação entre a prática do pedagogo, tal como formulada por Freire, e a do arquiteto, urbanista e paisagista no projeto participativo: ambas são dialógicas e interativas.

2 Diálogo de conhecimentos

Projetos participativos revelam fortes preocupações com a conquista coletiva dos direitos de cidadania e são profundamente permeados pela relação afetiva com o lugar.

A falta de afetividade pelos lugares e pelo que representam é um caminho reto para a pobreza cultural. As pessoas ficam desorientadas quando não conseguem mais entender a linguagem espacial que vivem no cotidiano e que lhes diz que neste presente particular, há passados respeitáveis e futuros esperançosos (SANTOS, 1984, p. 61).

Arquitetura e Urbanismo e seu ensino estão tradicionalmente baseados no positivismo racionalista, que, para Merleau-Ponty (1964), é uma visão de sobrevôo do que se pensa da realidade e não a realidade em si mesma, ignorando sua complexidade. Visão onde o outro é objeto e não outro sujeito com quem dialogar, em relação de alteridade, e com quem pode-se aprender no intercâmbio. Fechados nos escritórios de arquitetura, o que se pensa, muitas vezes, não é conferido com os usuários reais e o seu quotidiano. Repensar as relações arquiteto-usuário e professor-aluno é possível se a atitude de sobrevôo, de autoritarismo, se transformar numa ação de reciprocidade, construindo de forma coletiva os conhecimentos, assim como os lugares. Porém, essa relação se insere numa sociedade dominada pela lógica do mercado e pelos jogos de poder, tornando difícil a procura de caminhos. Para isto, refletir sobre ideias filosóficas e referências que experimentam práticas alternativas precursoras possibilitou compreender e aprofundar processos de criação na arte, arquitetura, educação e paisagismo, desenvolvendo relações de reciprocidade.

Existem muitas visões de mundo: um usuário pode ver, no ambiente, significados que um arquiteto não vê e vice-versa, o que também sucede na relação professor-aluno. A consciência do outro e das transformações mútuas que podem ser geradas no diálogo abre possibilidades de mudanças de atitude interativas.

Freire inspira uma articulação entre prática pedagógica interativa e dinâmica, entrelaçada com uma forma de agir do arquiteto na sociedade, dialógica, interativa, procurando construir um projeto participativo dos lugares, vendo o homem como um ser de relação “não apenas no mundo, mas com o mundo” (FREIRE, 1999, p. 43). Da mesma forma, ele iluminou os espaços da educação, considerando-os como relações interativas que transcendem o espaço formal e alcançam o informal “na cidade que se alonga como educativa” (FREIRE, 1997, p. 16). O autor destaca-as:

[...] relações entre educação, enquanto processo permanente, e a vida das cidades, enquanto contextos que não apenas acolhem a prática educativa como prática social, mas também se constituem, através de suas múltiplas atividades, em contextos educativos em si mesmos. (FREIRE, 1997, p. 16).

Assim, a percepção da cidade, necessária à ação do arquiteto e do estudante de arquitetura, revela o olhar que:

[...] destrincha ou esmiúça a sua significação mais íntima, expressa ou explicita a compreensão do mundo, [...] a inteligência da vida na cidade, o sonho em torno desta vida, tudo isso grávido de preferências políticas, éticas, estéticas e urbanísticas de quem o faz (FREIRE, 1997, p. 16).

A ação como docentes com os estudantes, no espaço formal universitário, na relação de diálogo que compõe a educação, incluirá a cidade como objeto de estudo e de proposta projetual, o que, ao se converter numa ação com a cidade, substitui a simples observação distante do objeto-cidade. Esta ação como educadores converge com a dos arquitetos ao “surpreender a cidade como educadora, também, e não só como o contexto em que a educação se pode dar, formal e informalmente” (FREIRE, 1997, p. 18). Ideias que coincidem com as de Maria Saleme de Burnichon e de Nidia Nacib Pontushcka.

Na arquitetura e urbanismo e no paisagismo, apresentam-se abundantes exemplos admiráveis no papel, que deixam de sê-lo ao serem vivenciados pelos usuários reais. A ausência de diálogo com os habitantes que residem nos lugares, em concordância com o pensamento de sobrevôo do arquiteto racionalista-positivista, que confere à arquitetura o poder de resolver os problemas da sociedade, se exemplifica na Carta de Atenas, acreditando poder controlar tudo, prever tudo. Se colocando acima dos reais moradores, esse arquiteto ou outro profissional racionalista-positivista exerce a tirania do desenho e do espaço (LIMA, 1989). Comprova-se que, ao abordar habitações coletivas, escolas populares, por exemplo, ou quando o destinatário é um trabalhador anônimo, urbano ou rural, a efeito da concepção do espaço projetado, esse usuário não tem voz nem vontade. Seus desejos e necessidades atravessam pela peneira interpretativa daqueles que muitas vezes o dominam (LIMA, 1989). O que coincide com a atitude do educador que considera seus alunos passivos receptores do saber absoluto, inquestionável e objetivo, afasta as emoções, friamente deixadas de lado para não interferir no raciocínio lógico, e se nega a dialogar com eles. Entretanto, Damásio afirma que “ao contrário da opinião científica tradicional, os sentimentos são tão cognitivos como qualquer outra percepção” (DAMÁSIO, 1996, p. 45), e, ao vincular a emoção ao processo de construção do conhecimento, este se enriquece.

Ao não analisar as pessoas com suas diversidades, suas maneiras diversas de sentir e perceber os espaços, planejamento de lugares, cidades, bairros, podem ser malsucedidos. As múltiplas e entrelaçadas vivências são demonstradas por Paulo Freire, ao dizer que:

A cidade se faz educativa pela necessidade de educar, de aprender...de criar, de sonhar, de imaginar que todos nós, mulheres e homens, impregnamos seus campos, suas montanhas, seus vales, seus rios, suas ruas, suas praças, suas fontes, seus edifícios... A cidade é cultura, criação, não só pelo que fazemos nela e dela, pelo que criamos nela e com ela, mas também é cultura pela própria mirada estética ou de espanto, gratuita, que lhe damos. A cidade somos nós e nós somos a cidade... Enquanto educadora, a cidade é também educanda (FREIRE, 1997, p. 23-24).

3 Participação, arte e percepção

O antigo provérbio chinês “Eu escuto... eu esqueço; eu vejo... eu lembro; eu faço... eu entendo” orientou o projeto “Uma Fruta no Quintal”. Lembra o ambiente do ateliê de Sergio Ferro, Rodrigo Lefevre e Flavio Império, que “além de ateliê era núcleo político, onde a produção artística - crítica acontecia ao mesmo tempo [...] produzindo à viva força as marcas do fazer”, nos anos 1960(ARANTES, 2002, p. 22).

No Teatro de Arena, onde o Império criava cenários, procurando “fazer com as próprias mãos o que pensava e ao fazer, instruir o pensar [...], e para Sergio Ferro, o momento de fazer, tanto na pintura quanto no teatro, é o momento mais rico e produtivo” (ARANTES, 2002, p. 22-23). O pensar do arquiteto, desconectado do fazer das mãos do operário, que, para Ferro, é castrado de sua competência criativa dentro do capitalismo, manifesta a divisão intelectual e manual do trabalho. Na produção do espaço na cidade, existe separação entre fazer e pensar e entre estes e o fruir. Este autor coloca a arquitetura, o urbanismo e o paisagismo no interior do processo de produção capitalista1, no espaço e tempo, deslocando-os do lugar ideal e abstrato que tradicionalmente lhes é designado, considerando que a produção da arquitetura, cidade e paisagem podem resumir-se à produção de mercadorias.

Esse é um dos temas mais complexos da contradição que caracteriza a alienação no interior da sociedade. A partir dessa contradição tentarei demonstrar uma ideia central: o casamento entre arte e economia-política como arma contra a alienação, que também inclui o sentimento de não pertencimento aos lugares. Relacionar essas afirmações com o projeto “Uma Fruta no Quintal” permite visualizar sua filiação ou marco referencial. Isto porque Ferro, Império e Lefreve foram referências marcantes para esse projeto, principalmente para o autor e coordenador geral, Raul I. Pereira, aluno desses arquitetos na FAU-USP. Para ele, era insuficiente a simples implantação física de praças e outros equipamentos de lazer, isolados do processo onde os moradores compreendessem e se reconhecessem nesses lugares. Experiências anteriores, por exemplo, em Osasco (1982 a 1986), e as que se fazem referência adiante, corroboraram a ideia de que ambientes são melhor mantidos quando moradores têm inclusão no processo de resolução e/ou execução desses lugares.

4 Escola: conexão entre moradores e seus lugares

Raul I. Pereira procurando a conexão entre habitantes e seus lugares, conclui que as escolas a possibilitariam

[...] por serem espaços potencialmente ricos de fluxos, encontros, energias e disponibilidades.Eles condensam, em um microcosmo, todas as contradições inerentes à sociedade brasileira porque são palcos, também, do conflito, do curto-circuito seco entre o pensamento e a dura concretude do dia-a-dia, entre a carência e a solidariedade. Não são só espaços de representação e de reflexão sobre a realidade, mas uma extensão, sem ruptura com o mundo extra-muros. Mesmo com as deficiências físicas e pedagógicas, reflexo do abandono a que foi relegado o ensino público no Brasil, as escolas possuem possibilidades infinitas de se transformarem em locais de mudanças e em pólos de irradiação de ações coletivas e transformadoras (PEREIRA, entrevista concedida à autora citada em DOBRY- PRONSATO, 2005, p. 53).

A ideia de que a escola é importante na abordagem participativa de projetos de espaços públicos é comum a vários arquitetos, em diversos lugares e momentos. Mayumi Souza Lima (1989, p. 74) realizou experiências no Jardim Guedala e Vila Sonia (São Paulo), em 1975, com crianças que desenvolveram “projetos falados”, passando ao projeto desenhado e a maquetes de papelão. Destes trabalhos participativos com crianças, a autora concluiu que: “[...] o projeto e a construção do espaço constituem uma atividade que necessariamente relaciona e articula contínua e dinamicamente o pensar e o fazer, mostrando que um interfere e modifica o outro” (LIMA, 1989, p. 75). Experiências de conteúdo similar são realizadas em diversos países, nem sempre conhecidas entre si e, não necessariamente, no mesmo período. Em “A Cidade e a Criança”, Lima cita as experiências de Boris e Hirschler na década de 1960 (BORIS; HIRSCHLER,1971 apud LIMA, 1989, p. 74).

O belo trabalho da EEPG João Kopke (1967-1978), efetivado por Mayumi Souza Lima e outros arquitetos (LIMA, 1989, p. 78), mostra possibilidades de envolver alunos no planejamento da construção escolar. A participação foi permeada por jogos de percepção de espaços e, nesse processo, foi-se construindo a consciência de que “a toda construção nova está ligada uma destruição” (LIMA, 1989, p. 80), que foi rapidamente percebida pelas crianças e adolescentes participantes. A afinidade com o Projeto Mutirão, realizado no Jardim Mutinga (Osasco), é manifesta ainda que, em 1983, Raul I. Pereira, seu coordenador, não conhecesse o trabalho dessa arquiteta.

Numa escola do bairro Parque Continental, em 1979-80, realizou-se um Estudo do Meio e os partícipes trabalharam com fotos de São Paulo em diversos períodos históricos, reconhecendo edifícios, bairros, e a rua e a casa onde residiam, para discutir e entender as transformações de espaço-tempo. Os docentes contaram com a participação de Paulo Freire e organizaram debates com outros grupos interessados, objetivando desenvolver uma reflexão coletiva. Estas atividades foram similares às desenvolvidas, por exemplo, no Ateliê 11 do Taller Total,na Escola de Colonia Lola (Córdoba), de que se falará adiante, e indicam que os caminhos percorridos por diversas pessoas, em diferentes lugares, em períodos próximos, porém não simultâneos, se relacionam com condicionantes da época e referenciais anteriores.

Entretanto, experiências participativas não se estabelecem exclusivamente nos trabalhos com crianças. Entrevistas e pesquisa bibliográfica demonstram que elas se desenvolveram vinculadas às lutas populares e à resistência à ditadura militar. Indicações importantes provêm de Osasco, onde o movimento operário foi um dos primeiros a sofrer repressão do regime de 1964. Trabalhando com alfabetização para adultos, no bairro Helena Maria, Paulo Freire desenvolveu importantes teorias que o fizeram conhecido internacionalmente. Nesse bairro, nos anos 1980, se desenvolveu o projeto Mutirão, entre outros. Simultaneamente, ao assumir o cargo de Secretário de Obras do município, Caio Boucinhas mencionou, em discurso, a abordagem participativa, citando Bertold Brecht:

Não devo esquecer nunca de um poeta muito ligado às lutas populares e que, numa poesia, perguntava: ‘Quem construiu a Tebas de setes portas? Nos livros estão nomes de reis. Arrastaram eles os blocos de pedras? Para onde foram os pedreiros, na noite em que a Muralha Da China ficou pronta? ’Porque não dá para esquecer o funcionário que tem como tarefa diária limpar uma boca-de-lobo ou a margem de um córrego cheio de ratos; não dá para esquecer o carinho do Seu Albano, um jardineiro de 70 anos que, sozinho, mantém a enorme área de lazer de Mutinga; do Munhoz e o seu orgulho no final do dia ao ver o gramado cheio de sol e de crianças; não dá para esquecer o rigor do apontador na fiscalização do material gasto, da hora de máquina trabalhada, zelando pelos nossos custos; não dá para esquecer o empenho dos engenheiros e arquitetos nos projetos da galeria, da canalização do córrego, da viela, da praça, do muro de arrimo; não é possível esquecer o trabalho paciente do braçal que fura manualmente, uma rocha de 3 metros de altura abrindo caminho para guia e sarjeta ou alguma moradia; não é possível esquecer ainda a dedicação dos funcionários do nosso plano de pavimentação e da equipe de moradia econômica, dos fiscais de obras particulares, do emplacamento, da topografia, de compras, de recursos humanos, das secretárias e datilógrafos. Enfim, não é possível esquecê-los porque sem eles nada acontece. Meu trabalho simplesmente vai se resumir em gerenciar, organizando e mobilizando essa grande equipe, dentro das nossas metas e recursos disponíveis (BOUCINHAS citado por DOBRY-PRONSATO, 2005, p. 56).

O “Projeto Mutirão” (1980) incluía o paisagismo participativo “Terrenos de Aventuras”, no Jardim Mutinga (Fig. 5), “especificamente dirigida às crianças e jovens do bairro, convidando-os para que, brincando, através do desenho, etc., imaginem, projetem seu sonho e se apropriem realmente desse espaço” (PEREIRA, 1983, p. 48), abrindo possibilidades de interação comunidade-profissionais, no projeto e na execução do lugar. A participação dos usuários desses espaços ajudou na sua manutenção, consolidando o espírito do lugar e desenvolvendo a conquista dos direitos cidadãos.

Fig. 5: “Terrenos de aventuras: Jardin Mutinga”: oficina com crianças, projeto participativo de praça. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal da autora.

O “Estudo do Meio na Aldeia de Carapicuíba”, por um lado, surge integrando-se à equipe coordenada pela Prof. Nidia Nacib Pontuschska, consolidada a partir de trabalhos realizados por ela e outros professores na escola do bairro Parque Continental, e, por outro lado, originou-se do projeto “Uma Fruta no Quintal”, posterior ao “Projeto Mutirão”.

5 Anos de ditadura

Nos anos 1960-1970, Rodrigo Lefevre procurava referências em Freire. Para ele, perguntas pertinentes para iniciar um processo projetual eram: “para quem”, “o quê”, “quando”, “como”. (ARANTES, 2002, p. 18). Nesses anos, na Argentina, na Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, da Universidade Nacional de Córdoba, também se desenvolvia uma proposta político-educativa estreitamente articulada a projetos apoiados por diversos grupos que o impulsionaram e definiram. Por outro lado, no campo disciplinar, se insere no debate sobre ensino de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, que permeou as décadas de 1960-70 e que revalorizava o pensamento da Bauhaus. No Brasil, se desenvolviam: a Fau-São José dos Campos, onde participaram como docentes, entre outros, Rodrigo Lefevre, Mayumi Souza Lima e o sociólogo Francisco de Oliveira; a Fau-UnB, com direção de Miguel Alves Pereira; e depois de 1976, se cria no México, o “Autogobierno”, na FAU-UNAM, com premissas semelhantes.

Estas referências indicam semelhança entre ideias expressadas em vários países com as do Taller Total , no que se desenvolveram temas como:

[…] a problemática social do déficit habitacional, e se deram como tarefa acadêmica pensar o modo e os meios para oferecer uma alternativa para superar esse estancamento deficitário. Por esse motivo tentaram se vincular às cooperativas de base em organizações de bairros que até então existiam, para elaborar um trabalho que serviria para a organização operativa dos mesmos e poder cumprir seus objetivos. Buscávamos a maneira de encontrar uma forma que as mesmas pessoas, mediante a cooperação comunitária, obtivessem suas moradias, gerando trabalho ao mesmo tempo. Assim, um grupo nutrido de alunos e docentes realizou um projeto relacionado com a cooperativa “El Huanquero”2, de coletores e recicladores de resíduos urbanos da Villa “Sangre y Sol” de San Vicente, Córdoba. Na tarefa de realizar uma experiência acadêmica realmente superadora, na busca de um ideal de todos compartilhando esforços e tratando de apontar soluções, se deu forma a uma Faculdade distinta, quase auto gestada, mas ideologicamente ampla. Nesse exercício acadêmico sobre o real, se perseguia o objetivo de uma sólida formação profissional […] Juan Antonio Romano e Inés Gauna […] e um grupo de pessoas […] com Camel Rubén Layún e Inés Graffigna, trouxeram o tema para a mesa inicial de nosso Taller e a todos nós – docentes e alunos sem distinção de possíveis bandeiras partidárias – nos pareceu aceitável tomar como tema […] (CIÁMPOLI, 2015, p. 1).

Entre os docentes, Elsa Larrauri, ao se exilar no México, participou na formação do “Autogobierno” a partir de sua experiência no Taller Total. Em sua homenagem, foi nomeado um auditório da universidade. Também se exilaram no México, Maria Saleme de Burnichon e Martha Casarini, membros da equipe de pedagogia do Taller Total, assim como graduados, entre eles, Cristina Salvarezza, que havia participado da experiência do Huanquero.

No ateliê 11, o arquiteto Osvaldo Bidinost, como docente, marcou o processo de ensino e aprendizagem, assim como Miguel Angel Cuenca, Pedro Rojo (mais conhecido como “Gallego”), Erik R. King, entre outros. Nesse ateliê, se realizaram práticas concretas de arquitetura participativa, em Colonia Lola, que:

[…] significou um aprofundamento da prática da arquitetura no Taller Total, tomando os fundamentos básicos do mesmo, aprofundando e levando a práticas concretas nesse marco de modificação da relação estudante-docente - usuário e sociedade. […] nos propomos a transmissão e elaboração de conhecimento coletivamente, onde intervieram os docentes, alunos da faculdade e os vizinhos do bairro. [..] se pensava em que os projetos […] deviam surgir não somente das necessidades do ateliê, se não também da relação do ateliê com as pessoas na rua (LASTRA, 2015, p.1 e 4).

A Equipe de Pedagogia incorporada ao corpo docente da FAU-UNC teve rol fundamental na construção do novo currículo.

6 Equipe de Pedagogia

A equipe de pedagogia formada por professores com diferentes trajetórias, unidos pela ideia de uma pedagogia crítica, contribuiu significativamente para o desenvolvimento dessa experiência.

A partir da intervenção desse grupo na elaboração da proposta teórico-metodológica do Taller Total se resumiu o que existia de mais avançado em matéria de teoria pedagógica em esses anos (LAMFRI, 2007, p. 131).

Colocou-se em prática o pensamento crítico pedagógico expressado numa proposta que apresentou desafios e exigiu criatividade, já que não existia outra referência (testemunho de um membro da equipe de Pedagogia concedido a LAMFRI, 2007, p. 131).

Maria Saleme de Burnichon foi um dos pilares pedagógicos do Taller Total da FAU-UNC, coordenando a Equipe de Pedagogia e, simultaneamente, desenvolveu trabalhos de alfabetização em Salta (Argentina), em cuja Universidade dirigiu o Ano Básico Comum (ABC) para ingressantes. Foi uma das máximas referências de educação na Argentina: demitida da Universidade Nacional de Córdoba, pelo golpe de Organía, em 1966. Exilou-se no México, onde foi pesquisadora da Universidade de Veracruz, em Xalapa, e realizou importante trabalho de alfabetização de adultos em comunidades indígenas e escolas rurais. Nessa mesma universidade, organizou a pós-graduação e participou da criação do “Centro de Investigações Educativas” (CIE). Em 1976, Burnichon teve que exilar-se novamente no México e só retornou à Argentina onze anos depois, reassumindo seu cargo na UNC. A Equipe de pedagogia contou com a participação, entre outros, de Alicia Carranza, Justa Ezpeleta, Lilians Fandiño, Marta Casarini, Lucia Garay, Guillermo Villanueva, Lucy Jachewasky, Susana del Barco e Neolid Ceballos, e também com o assessoramento de Delich, convidado para desenvolver temas no Taller Total, escutado com atenção pelos estudantes e docentes.

Para Maria Saleme de Burnichon (Fig. 6), “ensinar é aprender a escutar, é estar atento ao gesto do outro”. A autora também refletiu: “O valor do silêncio no ensino o recuperei a partir do México. Temos que escutar muito. Porque há coisas que não se diz, há linguagens que nós, com a nossa oralidade, tiramos o peso vital que elas têm, o peso comunicacional” (BURNICHON, 2005, s.p.).

É inegável a filiação do Taller Total à Bauhaus, que influenciou de maneira expressa a FAU-UNC. Também é impossível isolar o Taller Total das experiências pioneiras citadas que ocorreram no Brasil e no México. O contexto vivenciado na América Latina, nos anos 1960-70, exerceu forte impacto. No ano de 1968, as guerras prolongadas na China e no Vietnam são também momentos fundantes, que contribuíram para criar o clima de esperança e efervescência intelectual e de grandes debates, e, no campo específico, se desenvolveu o paradigma do artista comprometido com sua realidade, superando a divisão arquiteto social-arquiteto artista- técnico.

7 Arte e Participação

A opção sintetizada na frase “A saída encontrada foi a arte” (PEREIRA, 1996, p. 1), junta sentidos e inteligência, pensamento e emoção. Apóia-se na ideia de que o homem apropria-se dos objetos em cada uma de suas relações com o mundo: no ouvir, cheirar, ver, sentir, saborear, pensar, perceber, observar, querer, amar, sentidos que se formaram no decorrer da história. O ser humano se afirma no mundo ao pensar e com todos os sentidos. Mas, muitas vezes, se imagina que um artefato só é nosso quando o temos ou quando ele é utilizado por nós, e, assim, o sentido de ter aliena todos os outros sentidos. A arte possibilita brechas para vencer a alienação: a criação artística participa da relação de forças alienação-não alienação, fortalecendo a última.

A arte e a ciência, modos particulares da produção, estão submetidas à lei geraldo capitalismo e, inclusas no interior da alienação, não fogem a ela. Um sistema econômico social que gera a alienação do homem de sua própria produção, ao convertê-la em mercadoria, em objeto que se separa do ato criativo e se torna independente, não poderia gerar uma arte diferente. Também a arte, enquanto produto, ao ser finalizada, se separa do homem que a produziu, transformando-se em mercadoria e participando da lógica do sistema. Por outro lado, enquanto processo, a arte possibilita um “insight” que recupera o homem em seu fazer e pensar. Possibilidade menos alienada, pois, enquanto o homem se apropria dos objetos através dos sentidos, não precisa tê-los para usufruí-los.

Ainda sendo mercadoria, a arte é trabalho livre, diz Ferro, sintetizando a contradição arte-mercadoria:

[...] a arte se transformou num tesouro excepcional, [...] porque o trabalho livre é a coisa mais rara, [...] a contradição está dentro da arte, [...] penetrada pelo capital,[...], mas é, ao mesmo tempo, o último lugarzinho onde resta uma sombra de alguma coisa que escapa ainda ao capital, uma sombrinha de liberdade e de autonomia [...].Adorno fala, muitas vezes, que essa liberdade ainda possível dentro da arte [...], há que se resguardar, mesmo sabendo que ela é mercadoria.[...] (FERRO citado por ARANTES, 2006, p. 30 e 31).

Assim, Ferro retoma uma problemática antecipada pela Bauhaus: o respeito ao processo de arquitetura e urbanismo, entendido como produto e processo da ação dos homens, tais como a relação arte-técnica e cultura. Questões que também aproximam a Bauhaus das ideias desenvolvidas, entre outros, por Merleau-Ponty, Beuys e da pedagogia de Paulo Freire, Nidia Nacib Pontushka e Maria Saleme de Burnichon.

8 Considerações finais

A procura da própria identidade através da arte se relaciona com as possibilidades de organização da comunidade, com o objetivo de fruir seus lugares de vida, construindo, sutilmente, a dinâmica de uma relação delicada: a relação entre arte e política, que conflui numa permanente luta contra a alienação a que estamos submetidos. Os casos citados contemplaram três premissas: arquitetura é um campo de caráter prioritariamente social; seu ensino deve partir da análise da sociedade; sua gestão deve ser democrática e participativa. Conectam-se, nos casos analisados, duas ideias fortes – participar e colaborar –, carregadas de sentido dialógico, visando nortear a discussão sobre cada uma delas, sobre o tema, e sobre aquilo que as conecta, ou pode conectar. As experiências atuais, que respondem a estas premissas, em geral estão relacionadas à extensão universitária ou dentro do currículo formal em disciplinas isoladas ou com poucas inter-relações.

Referências

ANDERSON, P. As origens da pós-modernidade. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1999.

ARANTES, P. F. Arquitetura Nova: Sergio Ferro, Flavio Imperio e Rodrigo Lefevre, de Artigas aos Multirões. São Paulo: Ed. 34, 2002.

ARANTES, P. F. Sérgio Ferro: arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006.

BEUYS, J. Polentrasnport 1981: entrevista debate conduzida por Ryszard Syanislawisk. In: Et tous ils changet le monde. Lion: [s.n.], 1993. Catálogo da 2ª Bienal de Arte Contemporânea de Lion.

CIÁMPOLI, J. H. El Huanquero: Relato de una experiencia. In: TARTER, J., et al. (ed.). 1° Encontro Internacional ‘La formación Universitaria y La Dimensión social del profesional”. Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2015.

DAMÁSIO, A. O Erro de Descartes: emoção, razão e o cérebro humano. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996.

DOBRY-PRONSATO, S. A. Arquitetura e Paisagem: projeto participativo e criação coletiva. São Paulo: FUPAM / ANNABLUME / FAPESP, 2005.

FERRO, S. O Canteiro e o Desenho. São Paulo: Projeto / IAB, 1979.

FREIRE, P. Política e educação. São Paulo: Cortez, 1997.

FREIRE, P. A educação na cidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 1999

GOHN, M. G. Movimentos sociais e lutas pela moradia. São Paulo: Loyola, 1991.

LAMFRI, N. Z. Urdimimbres. El Taller Total: Um estúdio de caso. UNC. Córdoba: Centro de Estúdios Avanzados, 2007.

LASTRA, E. O. Taller 11-Colonia Lola. In: TARTER, J. et all. (Ed.s). 1° Encontro Internacional ‘La formación Universitaria y La Dimensión social del profesional”. Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2015.

LIMA, M. W. S. A cidade e a criança. São Paulo: Nobel, 1989.

MERLEAU-PONTY, M. L’oeil et L’espirit. Paris: Gallimard, 1964.

PEREIRA, R. I. Projeto “Mutirão”. São Paulo: Ed. Adm. Parro / Prefeitura Municipal de Osasco, 1983.

PEREIRA, R. I. Uma fruta no quintal: projeto de arte educ. ambiental. In: Vegetação aplicada ao projeto paisagístico. São Paulo: ABAP, 1996.

SANTOS, C. N. F. Preservar não é tombar, renovar não é por tudo embaixo. Revista Projeto, n. 86, 1984.

SALEME DE BURNICHON, M. S. Entrevista realizada em junho de 1996. La Educación en nuestras manos. Unificado de Trabajadores de la Educación de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, n. 23, Set. 2005.

SALEME DE BURNICHON, M. Decires. Córdoba: Narvaja, 1997.

Referências

Participatory architecture and urbanism: a genesis

Sylvia Adriana Dobry is an Architect, and Doctor in Architecture. She is a researcher at the Laboratory Landscape, Art and Culture (LabParc) of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. She was a teacher at the Taller Total of the Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo of the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. She studies the relationship between drawing, perception, and creation, education, participatory design, and history of Architecture and Urbanism.

How to quote this text: Dobry, S. A., 2019. Participatory architecture and urbanism: a genesis. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 18. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=4&lang=en>. [Accessed: 15 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 28, 2018

Abstract

This article, primarily memorialist, explores participatory project for Architecture and Urban Planning, methodology and value as process and art, collective and interdisciplinary creation. In the studied cases, made between the 1970s and the 1990s in São Paulo, Brazil and Cordoba, Argentina and in which authorities, communities, education and environment were associated, two strong ideas are connected - participation and collaboration -, filled with dialogical sense, aiming to guide the discussion of each of them on the subject, and on what connects, or can connect them. The production of places and landscapes, product and process of men’s action and creative activity, contains the alienation condition in which the production of every object within private property is subordinated. The dilemma “use value-exchange value” reveals the contradiction between art and commodity, as any product in the capitalist system of production, is separated from the artist who creates, becoming a commodity. Aiming to find gaps to overcome this contradiction, we understand that the relationship between art-politics-economy may create a possibility to overcome alienation. This would allow a creative activity, together with the inhabitants of places, opening doors to a democratic discussion about urban-landscape projects of these places, revealing potentialities.

Keywords: Participation, Genesis, Architecture and urbanism

1 Architecture and urban planning: participation

The word participation (lat. part+cipere) consists of the notions “part of, being part of” (lat. part) and “grab, take” (lat. cipere), indicating a voluntary and determined action. The word collaborate connects the latin meaning laborare - “to work, to feel pain, to be tired” - to the collective condition given by the co prefix - “together, with”. Maria da Gloria Gohn (1991) differentiates formal participation and real participation: the first carries a institutionalizing project and the second contains a transformative design, in which the popular management reveals conflicts, finding ways to desired changes from the root of its problems.

There is a convergence between education with participatory goals and participatory urbanism in the search of methodologies that allow insertion in place and its appropriation, developing creativity, cognitive imagination and democratic discussions, building a sense of belonging intertwined with citizenship construction.

The examined cases, carried out between the decades of 1970 and 1990, in São Paulo, Brazil and Cordoba, Argentina, connected authorities, communities, education and environment. It allows us to recognize that participatory process, permeated by affection for a place, is connected to the struggle for civil rights, contributing, often with resistance and insurgency, to an urban development that gives priority to the sense of belonging.

The simplicity of the "Uma fruta no Quintal" project proposal in 1996 was surprising for me: foresting the city through a planting made by its inhabitants, especially in schools. The proposal’s development was in the veins of the existing school organization, opening a place for discussion about the city as a subject, each time more distant from nature as an insensitive and violent concrete jungle. In a speech made by the general coordinator Raul I. Pereira, he questioned me about the meaning of being an architect, because in my career I have often heard phrases such as: "do not worry, architect, with this building’s facade, it is for the poor" or, "it does not matter if the bed does not fit in the room, it is just for the poor."

On the other hand, I simplically believed that drawing develops perception and sharpens the sight. Thus, to give people the opportunity to develop their drawing skills would enable a better understanding of their places of socialization, the advantages of preserving trees, rivers, etc. I relied more on the efficiency of making drawings than on making speeches to arouse sensitivity and humanity.

So the answer to the problem of how to solve the environmental education of children and teenagers: “the exit found was art” (Pereira, 1996, p.1) summarizes the central idea that permeates this reflection: through participatory project it builds, in a dialectical process, the relationship between politics, economy and art, creating an instrument for action against alienation (Anderson, 1999).

I realized, in the context of this project, that making art in schools, triggering and stimulating reflections on the city and the identity of those involved, contributes to the development of the appropriation of their places. To plant of trees, in an action carried out by the residents, after a process of discussion and reflection through art, enabled its transformation into a higher dimension: to be part of the construction of a sense of belonging.

I attended one of the events in a school in Diadema, located in a neighborhood of unfinished buildings made of perforated clay bricks, cramped buildings, cement and red earth, and no green areas. It was possible to see several four-storey buildings on narrow lots, no more than five meters wide. I have remembered of the image of the film "Pixote", the ugliness of the suburbs, poverty, places with almost no trees. As a rare reminiscent of a rural past, one could contemplate a wattle and daub ranch in an extensive land with horses, ducks and some trees. The school, enclosured by bars and with cement floors, red earth, rare patches of grass, embankments eroded by rain and a few recently planted trees on the occasion of the project. I noticed the school was in a celebration: children and adolescents, students smiling, elated and dazzled. The teachers, mostly women, making some efforts; worried, but happy. In the courtyards, in front of the outdoor stage, behind the bars, a standing crowd of parents, uncles and grandparents, cheering, proud to see their children - teenagers and children from the periphery - as "rockstars" in the school stage. The event, the culmination of the period of reflection and study about the environment, was the time when each class presented the issue through art.

Initially, the coordinator asked, "Who likes soccer? Which team do you root for?” From these simple questions the central issue came on: "Every day, a forested area corresponding to two soccer fields is destroyed in Brazil". After that, it was time for students and teachers present themselves, until moment of distribute fruit tree saplings.

A couple of anxiously expected clowns also took part in this party. A little girl insisted on saying that clowns were made of paper and did not exist, however, when challenged, she touched them carefully and, with surprise, she said: "they’re for real! They’re made of meat, like us!”. This girl’s feelings aroused intense questions in me, making myself to think about the great distance that separates periphery from artistic expressions, as popular as they are, such as circus or theater. I thought about how this contact is restricted to the small screen of television, in which distant actors, fictitious and “paper-like”, take the place of art in everyday life.

I noticed that often teachers took the students place, drawing for them, as they idealized a children's drawing but better. I wondered why: perhaps they had the feeling of being pressed to make their classes appear better. But in taking the place of the student, they included themselves in the multiplier circle of low self-esteem, since they, mistrusting of their own competence as educators, generated unconsciously on their students the feeling of not being able to do something well. Several educators in the process faced students that developed skills that they did not suspect to have, expressing euphoria and enthusiasm in these cases. Mathematics teachers were part of choirs, theater plays; biology teachers made models: the "Uma fruta no quintal" project opened the possibility of leaving their isolated boxes to join an integrated whole, regaining abilities and potentialities.

I realized in this project the possibility of lighting paths so that people could regain by themselves intrinsic issues to human beings, such as dancing, singing and drawing; activities that had been taken away by the decrease of hours reserved for art education and also by the transformation of art into commodity.

I wondered about the power that this truncated art would have to unravel the contradictions of the world. The evidence of, in the school network, bringing together people of different ages, social classes and the amplifier echo of the reflections formed there, offered the project the possibility of disseminating contributions about the city from participatory means, with multiplier effects, embbebed by everyday life.

I joined the project developing the subject "Perception of space through design”. Initially, the workshops were addressed to teenagers because of my experience as a professor at FAU, National University of Cordoba. Then, I developed workshops with teachers. This process reminded me of experiences I attended earlier in my career: the Taller Total, at FAU-UNC; the formation of ADAU (Architecture and Urbanism Teachers Association) part of FADU (University Teachers Associations Federation), Argentina, in the 1970s; and the performance of these organizations, bringing first and second degree teachers together, in actions for better working and educational conditions. Also, small schools of politics that were part of the resistance to the argentine dictatorship, after the military coup of 1976, joining teachers of all educational levels.

The memory of these experiences gave me confidence to start, over twenty years later, working on this project with teachers from municipal and state schools. I accepted the challenge of working with children, considering that the team would offer me support. It was an enriching experience to expand the perception of people in this age group, through the conception of paths, games, drawings and other art forms (Figure 1). "Uma fruta no Quintal" acted as the backbone, assembling projects from different departments and enabling interdisciplinary and interaction between them. At the meetings, team work guaranteed the non-conception of a "patchwork quilt" but a great flow, through all projects from different departments, to the general subject they were all included: the environmental issue. So, initially, appearing as a simple project for tree planting, it integrated and embedded issues such as pollution, trash, violence, traffic, sexuality, nutrition, etc., and included, as the centerpiece, the possibility of open people’s eyes to the place through art.

Fig. 1. Drawings produced in workshops with children in Diadema, in the project context.Source: Personal archive of the author.

During the "Uma fruta no Quintal" project, as a result of interaction with children, teenagers and teachers from schools in Diadema, my own artistic language has also been modified (Figure 2).

The project created in the Municipal Educational System of Diadema has developed a lot, accumulating experiences and effective partnerships between City Hall and the State. From that, municipal and private schools requested their inclusion, in the second semester of 1996, contributing to the divulgation on TV and newspapers. The deadline was too short to attend their requests, so it was decided to hold workshops together with teachers.

The direct contact with the students was lost but, on the other side, the exchange with the teachers - to which staff and parents were added - was enriching, enabling a better understanding of their point of view and the school structure in their daily lives. Presenting itself as a disadvantage, the situation has opened the possibilities for future experiments, such as the Environmental Studies in Carapicuíba village, related to the elaboration of a park project, implemented in 2004. Besides this, other participatory content projects such as “Pinheirinho water park” and the project "Tudo em Volta" in Santo André, developed by the interdisciplinary team from Laboratory for Research and Education in Human Sciences - School of Education - USP, LAPECH-FEUSP. Teachers involved in the “Uma Fruta no Quintal” workshops in Diadema, indicated that team which "coincided with the same ideas," and developed particularly environmental studies in an interdisciplinary way, supporting teachers of Municipal and State System, coordinated by Prof. Dr. Nidia Nacib Pontushka, allowing this connection.

In 1997, I took part in the architectural design study for the implementation of an urban revitalization project in Carapicuíba village in São Paulo. Beginning from an academic perspective, its limits were extended, including an urban design and landscape intervention in the place. At the initial meeting, Prof. Dr. Nidia Nacib Pontushka synthetized the history of Environmental Studies, a methodology that establishes an educational form in which all people participate: students, teachers, directors, employees, residents, parents, family and the school are not seen as an isolated environment. Born in the early twentieth century from the anarchist rebellion, it refuses classroom as hegemonic and emphasizes the direct observation of reality as a primary knowledge source (Figure 3). Another important aspect is that this interactive method can create expectations that suggest the reflection on the retribution of this design conception to the community group.

Fig. 3. Design and poetry of child School Carapicuíba village. Source: Personal archive of the author.

Fig.4. The Church Village of the Jesuits, Sylvia Dobry, watercolor. Source: Personal archive of the author.

The interaction with other forms of representation of the world, through workshops with Carapicuíba village school teachers has resulted in new representational forms of the author’s creative process (Figure 4). These experiences have confirmed that one of the most important knowledge construction sources is based on the appropriation of living places. This relationship is marked out in multiple writings of Paulo Freire, a strong reference to Prof. Dr. Nidia Nacib Pontushka and the LAPECH - FEUSP staff, but also for Maria Saleme de Burnichon, who ran Taller Total’s Psychopedagogy team in the years 1970-1975 in Córdoba, Argentina. It is possible to enhance the active participation of the students as a result of the link between life and school. The presence of a liberating pedagogy is possible only through this way, especially when considering that the educational relationship always occurs between people who represent the social complex, not only between individuals alone, indicating the existence of a connection between individuals and social development.

There is a coincident way of seeing the world between knowledge construction and places and landscapes construction, which allowed the detection of some important analogies to deepen this reflection. Among them, the relationship between community and its environment, understood as a dynamic process permeated with affection for the place and connected to struggles for citizenship rights. There is an interrelationship between the teaching practice, as formulated by Freire, and the architect, urban planner and landscape architect in participatory projects: both are dialogical and interactive.

2 Dialogue of knowledge

Participatory projects reveal strong concerns about the collective achievement of citizenship rights and are deeply permeatedby the affectionate relationship with the place.

The lack of affection for the place and for what they represent is a straight path to the cultural poverty. People get disoriented when they can no longer understand the spatial language in their everyday living and that tells them that in this particular present, there are reputable past and hopeful future (Santos, 1984, p.61).

Architecture and Urbanism and its teaching have traditionally been based on rational positivism which, for Merleau Ponty (1964), is a flyby view of what one thinks of reality and not reality in itself, ignoring its complexity. It is a view in which the other is an object and not an individual with whom establishes dialogues, in a relation of alterity, and someone one can learn in an interchange process. Closed in architectural offices, the logic often is not given together with its actual users and their everyday lives. The act of rethink the relation between architect-user and teacher-student is possible if the flyby attitude of authoritarianism, become a reciprocal action, building knowledge collectively, as well as places. However, this relationship is part of a society dominated by the market logic and power games, making it difficult to search for paths. For this, the observation of philosophical ideas and references that experience precursor alternative practices made the understanding and deepening of processes of creation in art, architecture, education and landscaping possible, developing relations of reciprocity.

There are many world views: an user can see meanings in the environment that an architect does not see and “vice versa”, which also happens in the teacher-student relationship. The awareness of the other and mutual transformations that can be generated in dialogues open possibilities for interactive attitude changes.

Freire inspires a connection between interactive and dynamic teaching practices, intertwined with forms for the architect operate in society, dialogical, interactive, seeking to build participatory project for places, recognizing men as a relations being “not only in the world but with the world" (Freire, 1999, p.43). Likewise, he lit educational spaces, considering them as interactive relationships that go beyond formal space and reach the informal "in the city that extends itself as educational" (Freire, 1997, p.16). The author highlights:

[...] relationship between education as a permanent process, and the life of cities as contexts that not only hold educational practice as a social practice, but also constitute, through its multiple activities, in educational settings in themselves” (Freire, 1997, p.16).

Therefore, the perception on the city required to the architect and architecture student’s action, reveals the view that:

[...] breaks down or dissects its innermost meaning, expresses or explicits the understanding of the world, [...] the intelligence of life in the city, the dream around this life, all this pregnant of political, ethical, aesthetical and urban planning preferences of who does it" (Freire, 1997, p.16).

The action as of teachers with students, in the formal academic space, in the dialogical relation that composes education, will include the city as a study object and design proposal, in which converting into an action with the city, replaces the simple remote object-city observation. This action as educators, converges with the architects’ one when "surprising the city as an educator, too, and not only as the context in which education can be given, formally and informally" (Freire, 1997, p.18). These are ideas that coincide with the ones from Maria Saleme of Bournichón and Nidia Nacib Pontushcka.

In architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture, there are present some abundant admirable examples on paper that stop being so when they are experienced by real users. The absence of dialogue with the people who live in those places, in accordance to the flyby logic of the positivist-rationalist architect, gives architecture the power to solve the problems of society as, for example, in the Charter of Athens, one believing to have the ability to control everything, to predict everything. When the architect or other racionalist-positivist professionals put themselves up to the actual residents, they exercise design and space tyrannies (Lima, 1989). This is proved when collective housing or public schools addressing, for example, when its clients are anonymous urban or rural workers, do not have voice or will. Their wants and needs go through the interpretative sieve of those who often dominate (Lima, 1989). This coincides with the attitude of the educator who considers its students passive recipients of absolute, indisputable and objective knowledge, away from emotions, coldly swept aside not to interfere in their logical reasonings, refusing to talk with them. However, Damasio states that "unlike traditional scientific opinion, feelings are just as cognitive as any other perception" (Damásio, 1996, p.45), and by linking emotion to the process of knowledge construction, this becomes richer.

By failing to examine people and their diversity, their various ways to feel and perceive, the spaces, the planning of places, cities and neighborhoods may be unsuccessful. The multiple and intertwined livings are demonstrated by Paulo Freire when he says:

The city makes itself educational by the need of educating, of learning ... of creating, of dreaming, of imagining that all of us, women and men impregnate their fields, their mountains, their valleys, their rivers, their streets, their squares, their sources, their buildings ... The city is culture, creation, not only by what we do in it and of it, by what we create on it and with it, but also it is culture by its own aesthetic glance or astonishment, free, we give to it. The city is us and we are the city ... As an educator, the city is also a pupil" (Freire, 1997, pp.23-24).

3 Participation, art and perception

An old Chinese proverb "I hear ... I forget; I see ... I remember; I do ... I understand" guided the Project "Uma Fruta no Quintal" - it recalls the atmosphere of Sergio Ferro, Rodrigo Lefevre and Flavio Império studio that, "besides studio was a political core, where the artistic - critical production happened while [...] producing by living force the marks of doing" in the 60s (Arantes, 2000, p.22).

In the Teatro da Arena, where Império created scenarios, trying “to do with his own hands what he thought and, while doing, instruct its thoughts [...] and for Sergio Ferro, the time of doing, both in painting and in the theater, is the richest and most productive moment.” (Arantes, 2000, pp.22-23). The architect’s thinking, disconnected from the worksman’s making, for Ferro, neutered their creative powers within capitalism and shows the intellectual division of labor and manual. The production of space in the city separate doing and thinking, and between those and fruition. This author puts the architecture, urban planning and landscaping within the capitalist production process1, in space and time, moving them from the ideal and abstract place that these are traditionally appointed, considering that architectural, urban and landscape productions, can be summarized as the production of goods.

This is one of the most complex issues of contradiction that characterizes alienation within society. From this contradiction I try to show a central idea: the link between art and political economy as a weapon against the alienation, which also includes the feeling of not belonging to places. Relating these statements to the "Uma Fruta no Quintal" project allows people to see its origins or referencial point. This is because Ferro, Imperio and Lefevre were important references to this project, especially for the author and the project’s General Coordinator, Raul I. Pereira, who was their student at FAU-USP. For him, it was insufficient to simply deploy squares and other leisure facilities, isolated from the process in which the locals could understand and recognize those places. Previous experiences, for example, in Osasco (1982 to 1986), and those referred therefore, corroborated the idea that environments are best sustained when their residents are included in the resolution process and/or execution of these places.

4 The school: a connection between residents and their places

When Raul I. Pereira looks at the the connection between inhabitants and their places, concludes that schools would enable that

[...] because they are potentially rich spaces for fluxes, meetings, energy and disponibilities. They condense, in a microcosm, all the contradictions inherent to Brazilian society because they are stages, also, of the conflict, the dry short-circuit between thought and hard concrete daily routine, between deprivation and solidarity. They are not only representational and reflectional spaces of reality, but an extension without breaking with the extramural world. Even with physical and pedagogical disabilities, an echo of the abandonment that was relegated to the public education in Brazil, schools have endless opportunities to become spaces of changes and irradiation poles of collective and transformative actions (Pereira, interview given to the author cited in Dobry-Pronsato, 2005, p.53).

The idea that school is important in the participatory approach of public space projects is common to a number of architects in various places and times. Mayumi Souza Lima (1989, p. 74) conducted experiments in Jardim Guedala and Vila Sonia (São Paulo) in 1975, with children who developed "spoken projects" and going to the drawing designs and cardboard models. In this participatory work with children, she concludes: "[...] the spacial design and construction constitute an activity that necessarily relates and articulates continuously and dynamically thinking and doing, showing that one interferes and modifies the other” (Lima, 1989, p.75). Experiences of similar content are held in many countries, not always known by each other and not necessarily in the same period. Mayumi S. Lima, quoted in "A cidade e a criança”, the experience of Boris and Hirschler in the 1960s (Boris and Hirschler, 1971 cited in Lima, 1989, p.74).

The beautiful work of EEPG João Kopke (1967-1978), effectivated by Mayumi Souza Lima and other architects (Lima, 1989, p.78), shows possibilities to involve students in the school construction planning. Its participation was permeated by space perception games and, through this process, has built the awareness that "every new construction is linked to a destruction" (Lima, 1989, p. 80) which was quickly perceived by children and teenage participants. The affinity with the Projeto Mutirão held at Mutinga Garden (Osasco) is present, although in 1983, Raul I. Pereira, its coordinator, did not know the work of this architect.

In a school at Parque Continental neighborhood, in 1979-80, there was an Environmental Study in which its participants worked with pictures of São Paulo in different historical periods, recognizing buildings, neighborhoods and the street and the house where they had been living to discuss and understand the transformations of space-time. Teachers had the participation of Paulo Freire and organized discussions with other interested groups, aiming to develop a collective reflection. These activities were similar to those developed, for example, in the Taller Total’s Studio 11, in Colonia Lola School, of which we will speak further on and that indicate that the paths taken by different people in different places, in upcoming periods, but not simultaneous, are related to the constraints of their time and earlier references.

However, participatory experiences are not settled only by working with children. Interviews and bibliographic searches demonstrate they were developed close to popular struggles and resistance to military dictatorship. Some important indications are from Osasco, where the labor movement was one of the first to suffer repression from the 1964 regime. When working with adult literacy in the neighborhood Helena Maria, Paulo Freire developed important theories that made him internationally known. In this neighborhood, in the 80s, he developed, among many, the Mutirão project. Simultaneously, Caio Boucinhas, who assumed the position of Secretary of Municipal Works, mentioned participatory approach in a speech quoting Bertolt Brecht:

I must not ever forget a poet very connected to popular struggles that, in poetry, asked: 'Who built the Seven-Gated Thebes? There are kings’ names in the books. Did they dragged the stone blocks? Where did the masons go in the night the Wall Of China was concluded? 'Because you can not forget the employee whose daily task is to clean a manhole or the bank of a stream full of rats; can not forget the affection of Seu Albano, a 70-year old gardener who keeps the huge Mutinga recreation area by himself; of Munhoz and his pride of seeing the lawn full of sunshine and children at the end of the day; one can not forget the accuracy of the pointer in the supervision of spent material,of woked times by the machine, caring for our costs; it is not possible to forget the commitment of engineers and architects in the projects of underground galleries, stream pipelines, alleys, squares, retaining walls; can not forget the patient manual work that carves a three meters tall rock, giving way to a guide, gutter or some house; It is not possible to forget the dedication of the staff of our paving plan and the staff of affordable housing, of the private construction, license plate, topography, purchasing and human resources supervisors, secretaries and typists. Anyway, you can not forget them because without them nothing happens. My job will simply be summarized by managing, organizing and mobilizing this great team, within our goals and available resources (Boucinhas, cited in Dobry-Pronsato, 2005, p.56).

The Mutirão project (1980) included the participatory landscaping "Adventures of land" in Jardim Mutinga (Figure 5), "specifically aimed at children and young people from the neighborhood, inviting them to imagine, to design their dreams and really take ownership of this space through playing and drawing" (Pereira, 1983, p.48), opening up possibilities of a professional-community interaction and the consequent design and execution of spaces. The participation of the users of these spaces helped to keep its maintenance, of which assisted to the consolidation of the spirit of the place and the development of citizens rights conquests.

Fig.5. "Adventures of land: Jardim Mutinga": workshop with children, participatory design court. Source: Personal archive of the author.

The "Environmental Studies in Carapicuíba village" on one hand, came up by integrating itself to the team led by prof. Nidia Nacib Pontuschska, reinforced by some other works done by her and other teachers in Parque Continental neighborhood school. On the other hand, it came up from “Uma Fruta no Quintal”, later to the Mutirão project.

5 Years of dictatorship

In the 1960s and 1970s, Rodrigo Lefevre sought references in Freire. For him, there were some pertinent questions to initiate a design process: "what", "when", "how" and "for whom" (Arantes, 2002, p.18). In those years, the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning of the National University of Cordoba, in Argentina, also developed a political-educational proposal articulated closely to projects supported by several groups that have boosted and defined it. In the disciplinary field, on the other hand, it was inserted in the debate about Architecture and Urban Planning teaching, that permeated the decades of 1960-70 and that revalorized the thought of the Bauhaus. In Brazil there were: Fau-São José dos Campos, where Rodrigo Lefevre, Mayumi Souza Lima and sociologist Francisco de Oliveira participated as teachers; Fau-UnB, directed by Miguel Alves Pereira; and after 1976, "Self-government" was created in Mexico at FAU-UNAM, with similar premises.

These references indicate similarity between ideas expressed in several countries with the ones from Taller Total, in which some themes were developed, such as:

[...] the social problem of housing shortage, and were given as an academic task on thinking about ways and means to offer an alternative to overcome this stagnation deficit. Therefore, they tried to link themselves to base unions in neighborhood organizations that until then have existed, to prepare a work that would suit their operational organization and fulfill their goals. We sought a mode of finding a way that the same people, through community cooperation, could obtain their houses, creating jobs at the same time. Thus, a large group of students and teachers held a project related to the "El Huanquero"2 cooperative, of waste collectors and recyclers from the Villa "Sangre y Sol", from San Vicente, Córdoba. In order to carry out a really surpassing academic experience, in the search for an ideal of all sharing efforts and trying to point out solutions, a distinct College was formed, almost self gestated, but ideologically wide. In this academic exercise on the real, the goal of a solid professional training was pursuit [...] Juan Antonio Roman and Inés Gauna [...] and a group of people [...] with Camel Rubén Layún and Inés Graffigna, brought the issue to the initial table of our Taller and to all of us - teachers and students without distinction of possible party flags - it seemed acceptable to take it as its theme [...] (Ciámpoli, 2015, p.1).

Among the teachers, Elsa Larrauri, while exiled in Mexico, participated in the "autogobierno" formation from her experience in the Taller Total. In her honor, an university auditorium was named after her. Maria Saleme of Burnichon and Martha Casarini, members of the Taller Total teaching staff, also got exiled in Mexico, as well as some graduates, among whom Cristina Salvarezza, who participated in the Huanquero experience.

In studio 11, architect and teacher Osvaldo Bidinost marked the teaching and learning processes, as well as Miguel Angel Cuenca, Pedro Rojo, better known as "Gallego", Erik R. King, among others. In this workshop, concrete practices of participatory architecture took place in Colonia Lola, which