Participação ou representação: escolhas patrimoniais no Rio Grande do Sul

Ana Lúcia Goelzer Meira é Arquiteta, Doutora em Planejamento Urbano e Regional. Professora da Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, nos cursos de graduação, Mestrado Profissional em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, e Especialização em Cidades: Gestão Estratégica do Território Urbano. Estuda a preservação de áreas urbanas, restauração de edificações de interesse cultural, e a participação popular em ações de preservação.

Como citar esse texto: MEIRA, A. L. G. Participação ou representação: escolhas patrimoniais no Rio Grande do Sul. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 18, 2019. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=5&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 28 DE AGOSTO DE 2018

Resumo

O campo da preservação do patrimônio cultural é construído pelas escolhas sobre o que ser protegido para a fruição das atuais e futuras gerações. Discute-se a necessidade de participação da sociedade civil nessas escolhas, seja de forma direta ou por meio de representantes. Foram revisados processos de tombamento em nível nacional referentes ao Rio Grande do Sul, o estado mais meridional do Brasil, e solicitações de tombamentos municipais na capital, Porto Alegre. A ênfase da pesquisa oscilou entre o final do século XX e o início do século XXI. Nos dois âmbitos, percebe-se que muitas manifestações pela preservação do patrimônio foram encaminhadas por meio de processos participativos aos órgãos públicos. Porém, sugere-se que há um descompasso entre as escolhas dos técnicos e as dos grupos sociais, sendo que as primeiras são mais facilmente legitimadas pelos instrumentos de preservação institucionais; e as demais, quase nunca. Os resultados dos processos nos âmbitos nacional e municipal são relevantes e colaboram para a reflexão sobre a preservação do patrimônio cultural. Pretendeu-se verificar se a sociedade e seus representantes participam ou colaboram para construir a ideia da preservação patrimonial.

Palavras-Chave: Patrimônio arquitetônico, Participação social, Preservação patrimonial, Orçamento participativo

1 Considerações iniciais sobre o tema

A preservação do patrimônio cultural, constituído pelos bens materiais e imateriais conforme previsto na Constituição Federal (BRASIL, 1988), é permeada pelas escolhas sobre o que será efetivamente protegido para as futuras gerações brasileiras. Essas escolhas se apoiam em valores que variam com o tempo e com o lugar. A necessidade de participação direta da sociedade civil ou por meio de seus representantes nesse processo é um assunto discutido há décadas. Uma das frases mais difundidas de Aloísio Magalhães, durante o período em que dirigiu o sistema SPHAN/Pró-Memória1, nos anos 1980, já explicitava que a comunidade é a melhor guardiã do seu patrimônio (IPHAN, 2015). Mas esse slogan, que passou a ser repetido com variações ao longo de décadas, na prática, não conseguiu permear as ações de preservação. Os técnicos e os políticos continuam detendo a hegemonia sobre as escolhas do que vai se tornar patrimônio, ou seja, sobre os bens que serão reconhecidos e preservados pelo Estado. Trata-se da nomeação oficial a que se referia Bourdieu (1989)2. Consequentemente, por exclusão, eles também determinam os bens que não serão reconhecidos, que, portanto, ficam liberados para a desaparição. Expor essas contradições pode auxiliar no processo de democratização das escolhas, ao permitir uma seleção mais diversificada de bens patrimoniais.

Os apontamentos aqui apresentados foram estabelecidos a partir de duas pesquisas realizadas pela autora: uma sobre as políticas públicas e a participação da sociedade na preservação do patrimônio cultural de Porto Alegre (MEIRA, 2004) e a outra que versa sobre a ação federal de proteção do patrimônio histórico e artístico no Rio Grande do Sul (MEIRA, 2008), ambas concentradas no século XX. O cruzamento dos dados pode fornecer indícios para a compreensão do que se estabeleceu como norma em relação à participação da sociedade civil nas políticas públicas patrimoniais. A comparação entre os processos nas duas instâncias de governo, mesmo que não esgote o tema, pode servir como contribuição às reflexões sobre a trajetória da preservação e suas interfaces com a mobilização da sociedade.

Em geral, a preservação do patrimônio cultural deriva de olhares técnicos e de interesses políticos, desconsiderando e desqualificando a participação dos cidadãos. A esses, muitas vezes, são atribuídos o desconhecimento e o descaso em relação à importância dos bens culturais. Nesse sentido, uma das grandes questões relacionadas à preservação do patrimônio cultural brasileiro é a busca de participação nas decisões sobre o que, como e para quem preservar. Assim como proceder à escuta ativa da população, não no sentido da simples divulgação, mas sim no diálogo para conjuntamente entender quais são as referências culturais de importância local, regional, estadual ou nacional.

2 Participação ou representação nas escolhas dos bens patrimoniais

Sobre o início das políticas públicas de preservação do patrimônio, no Brasil, há que se mencionar que, entre os anos de 1934 e 1937, funcionou a Inspetoria de Monumentos Nacionais como um departamento do Museu Histórico Nacional (MHN). Gustavo Barroso foi o primeiro diretor do Museu e acompanhou a execução de algumas obras no conjunto histórico de Ouro Preto pela Inspetoria (BARROSO, 1944).

Em 1937, foi implantado oficialmente o Serviço do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional – atual IPHAN, e assinado o Decreto-Lei nº 25/37 – a Lei de tombamento federal (BRASIL, 1937). A nova instituição, responsável pela identificação, documentação, proteção e promoção do patrimônio cultural brasileiro, foi construída pela vanguarda intelectual moderna. Nos primeiros anos, contribuíram para os trabalhos, alguns escritores e poetas (como Mário de Andrade, Manuel Bandeira e Carlos Drummond de Andrade), historiadores (como Sérgio Buarque de Holanda; antropólogos como Gilberto Freyre) e arquitetos (como Lucio Costa), dentre outros. No Rio Grande do Sul, o primeiro representante regional foi o escritor modernista Augusto Meyer.

As escolhas dos bens que constituem o Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional, por meio do tombamento3, foram estratégicas para a construção de uma identidade nacional que se pretendia unívoca no Estado Novo. Após algumas décadas, a enormidade do trabalho a ser realizado fez com que as atribuições para preservar o legado cultural brasileiro fossem compartilhadas com os estados e municípios. Foram criadas leis e instituições nos âmbitos municipal e estadual à semelhança das estruturas em nível federal. Ocasionalmente, resultaram em ações conjuntas de trabalho: como o Programa de Cidades Históricas, nos anos 1970; o Programa Monumenta, no final da década de 1990; e o Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (PAC) das Cidades Históricas, no início do século XXI. Mas, em geral, não se pode falar em um trabalho coletivo entre as instituições de preservação nos três âmbitos de governo. Muitas são as diferenças de ordem política, técnica, financeira e outras que dificultam uma colaboração em condições equilibradas.

No âmbito estadual sul-rio-grandense, as atribuições relativas à preservação passaram a ser desenvolvidas pelo Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico do Estado – IPHAE –, órgão subordinado à Secretaria da Cultura, Turismo, Esporte e Lazer – Sedactel. Em nível municipal, foi criada a Equipe do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural – EPAHC –, vinculada à Secretaria Municipal da Cultura de Porto Alegre. Na comparação aqui proposta, serão verificadas as ações federais do IPHAN em relação ao RS e as ações da EPAHC em relação a Porto Alegre. Em ambos os casos, a ênfase será a participação de segmentos da sociedade civil nos processos de preservação do patrimônio cultural arquitetônico.4

Normalmente, as ações municipais relativas à preservação do patrimônio cultural, no Brasil, restringem-se ao acervo arquitetônico e urbanístico. Aplicam-se leis específicas (tais como o tombamento e o inventário) e instrumentos de planejamento urbano (tais como planos diretores, leis de uso do solo e outros). Em Porto Alegre, a lei de tombamento municipal e o planejamento urbano são aplicadas desde os anos 1970.

Em geral, o poder público considera a participação da sociedade civil por meio de representantes nos conselhos de patrimônio, aos quais cabe avaliar a relevância dos bens propostos para proteção, dentre outras finalidades. Nesse particular, os conselhos atuam no final do processo, numa etapa em que os bens já foram escolhidos, estudados e analisados, os valores já foram ajustados a cada caso e estão aptos a serem legitimados como patrimônio por meio de votação entre os conselheiros. A participação do conselho, na etapa final de um tombamento, seria suficiente para garantir a preservação da diversidade dos bens culturais materiais?

Pesci (1999) considera três tipos de participação cidadã com agentes sociais: direta, indireta e experimental. O primeiro compreende as assembleias e reuniões públicas, as oficinas (atividades grupais com maior duração que as anteriores) e as pesquisas de opinião. O segundo utiliza basicamente técnicas de percepção ambiental e de reconhecimento das linguagens de padrões do ambiente. A participação experimental procura simular o modelo a ser construído. A representação, por outro lado, baseia-se nas manifestações de representantes de segmento ou organização, cuja fala possibilita a visibilidade de suas posições. Podem ser políticos eleitos ou conselheiros em políticas públicas e são escolhidos por seus pares (RAMOS, 2018).

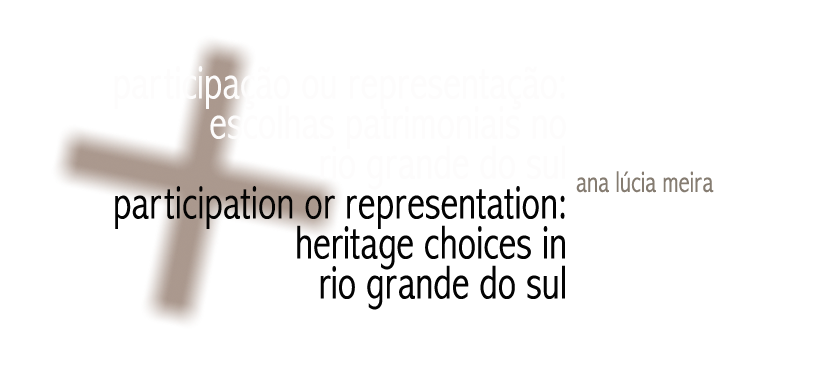

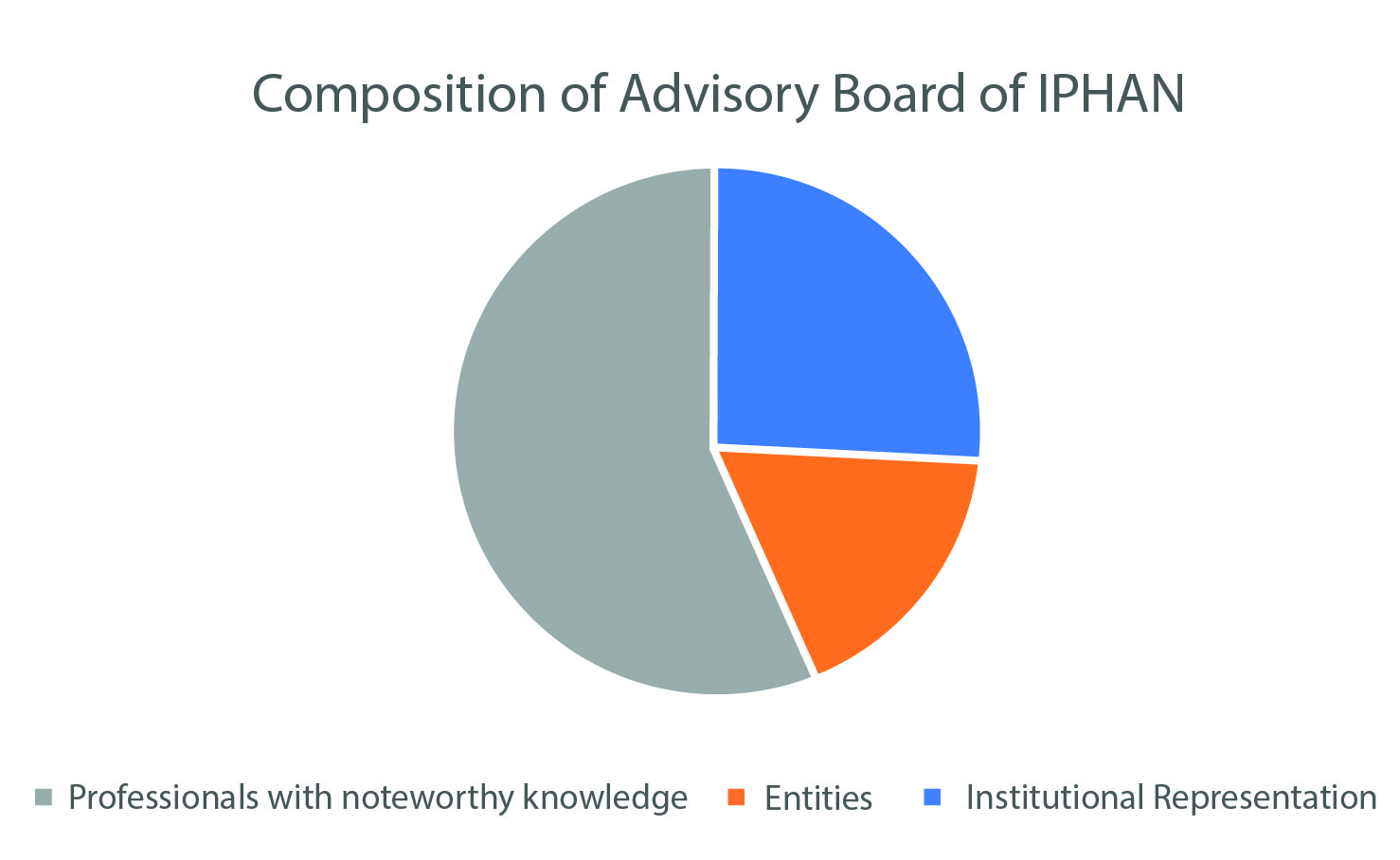

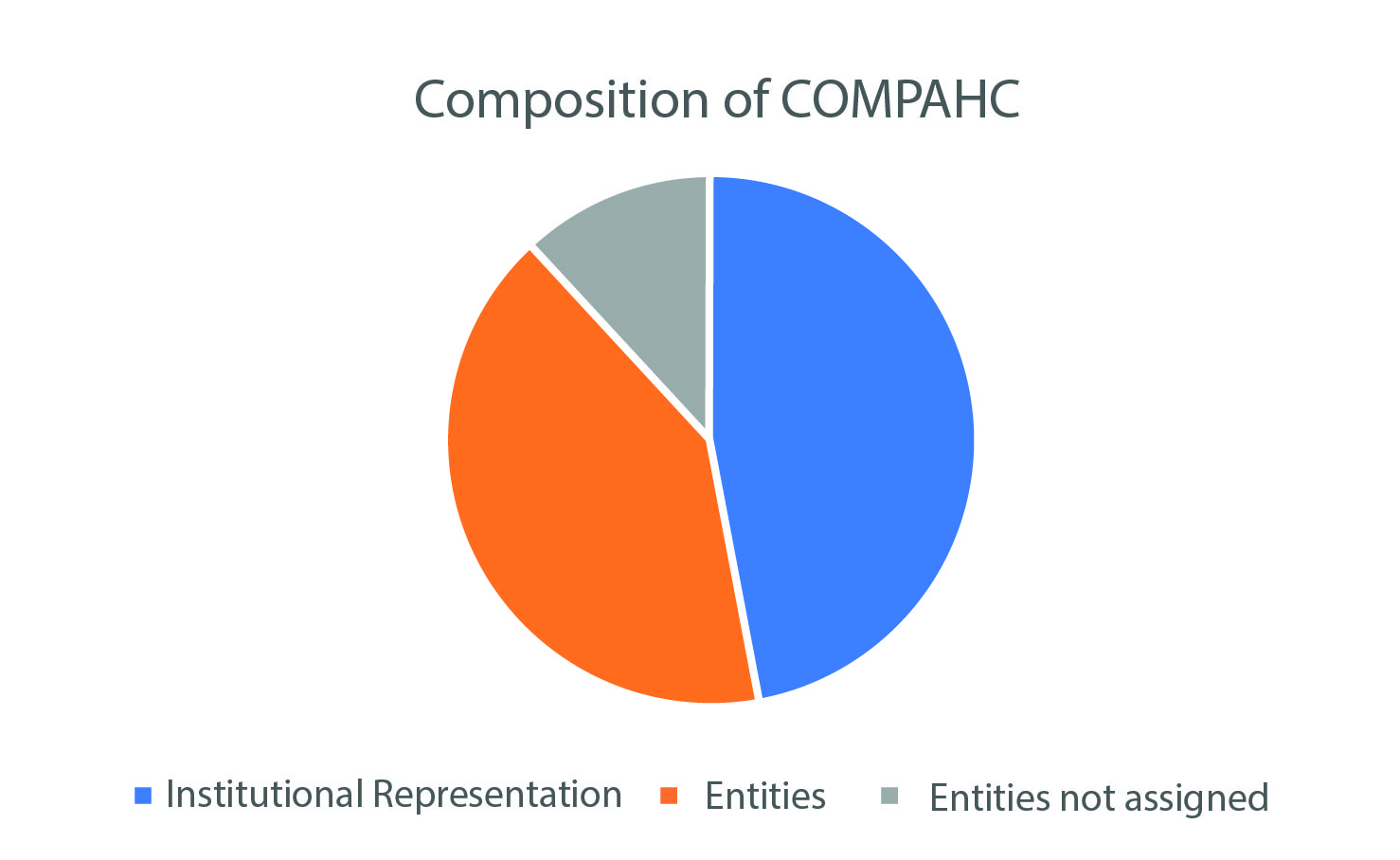

Em nível nacional, junto ao IPHAN, desde a sua criação, há o Conselho Consultivo, hoje formado por vinte e três membros, sendo o Presidente do Instituto considerado membro nato (BRASIL, 2017). A proporção entre os representantes institucionais e aqueles da sociedade civil pode ser verificada na Figura 1. Há nove representantes de órgãos e associações federais (Ministérios da Educação, do Turismo, das Cidades, do Meio Ambiente, Instituto Nacional dos Museus, Instituto de Arquitetos do Brasil, Conselho Internacional de Monumentos e Sítios, Sociedade de Arqueologia Brasileira, e Associação Brasileira de Antropologia), além de treze profissionais de notório saber nas áreas relacionadas ao patrimônio cultural, os quais são indicados pelo Presidente do IPHAN.5

Fig. 1: Distribuição atual dos membros do Conselho Consultivo do IPHAN. Fonte: Elaborado pela autora, 2018.

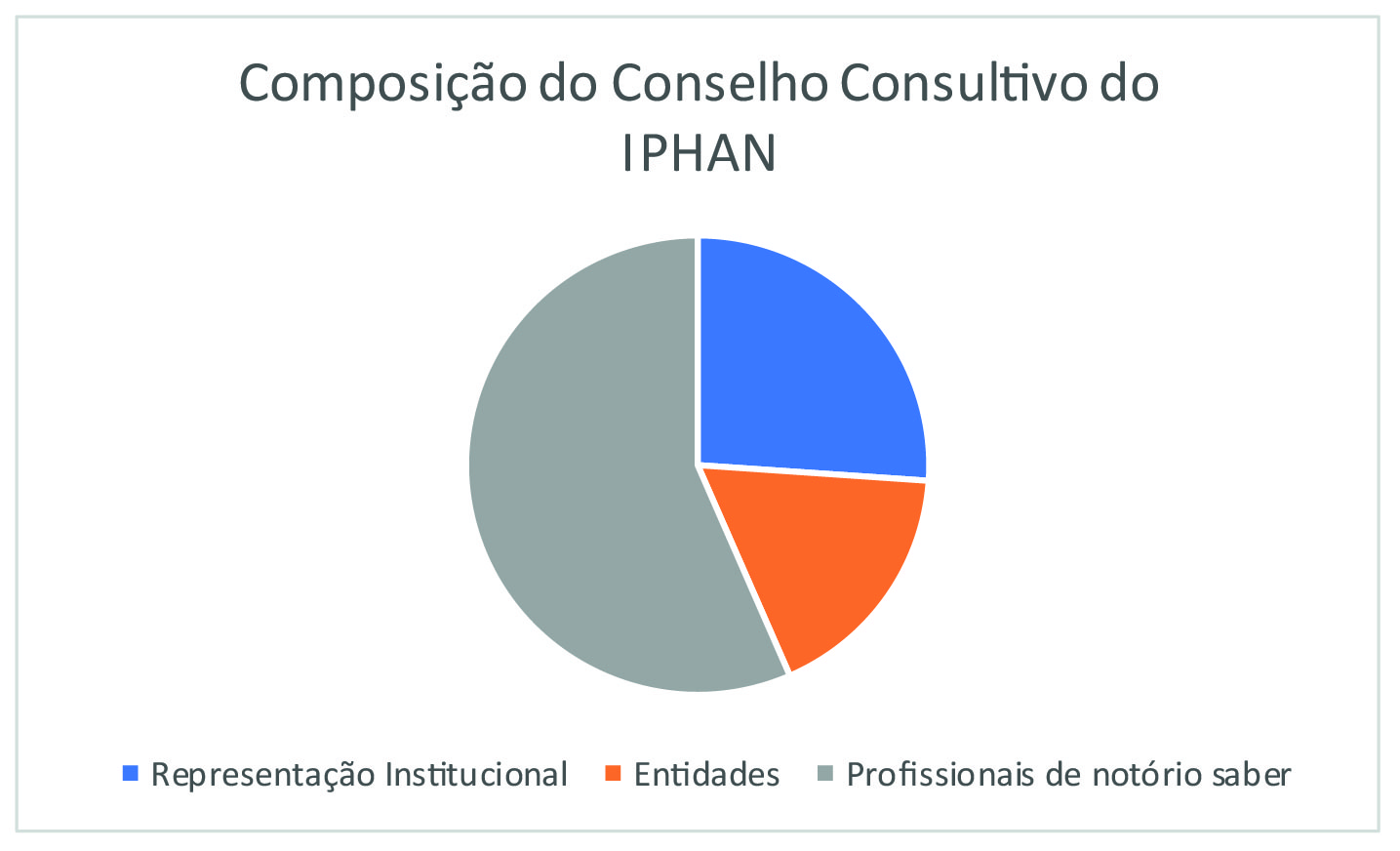

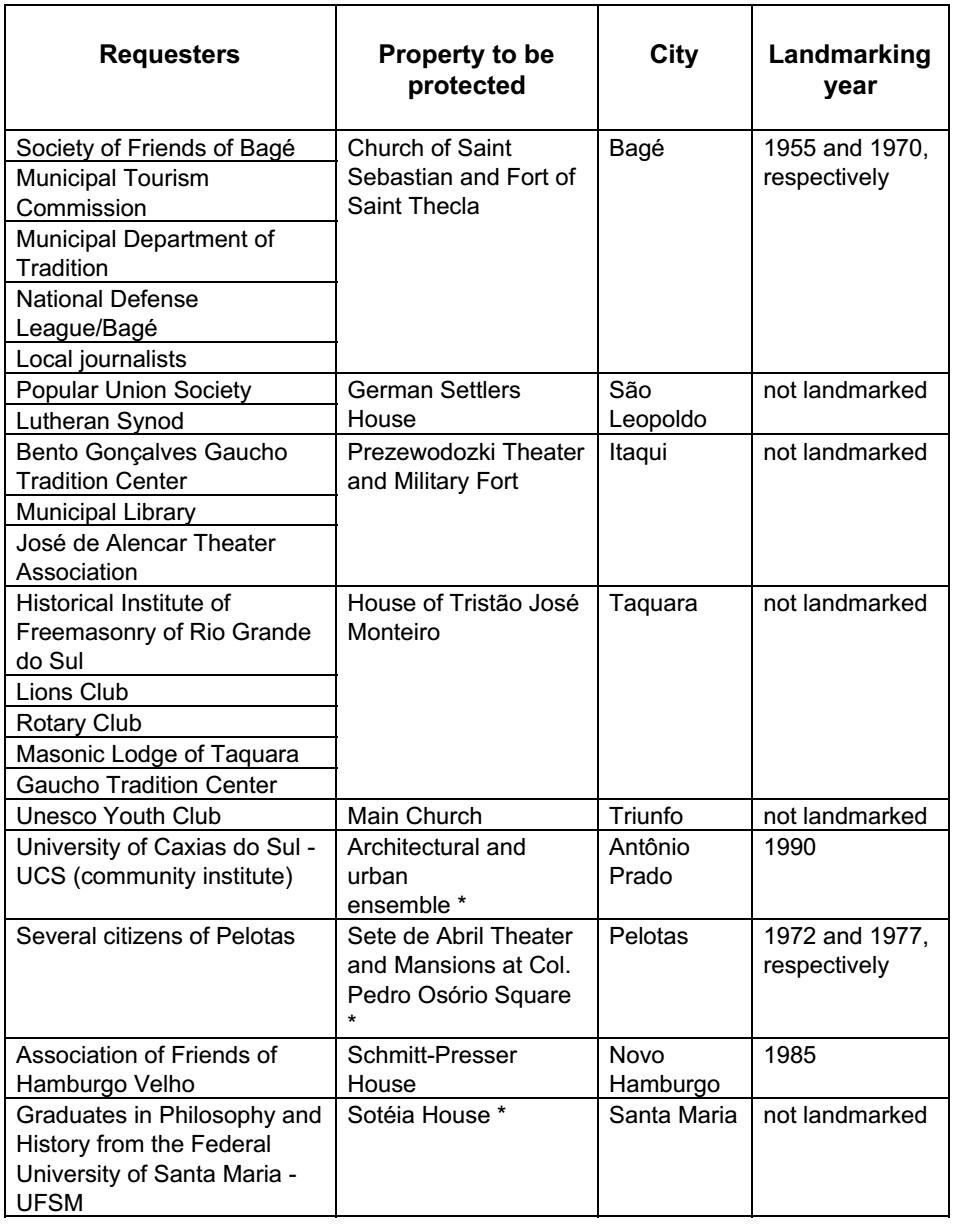

Em nível municipal, articulado com a Secretaria de Municipal de Cultura de Porto Alegre, há o Conselho do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural – COMPAHC –, composto na prática por quinze membros: oito representantes da Prefeitura Municipal e sete de entidades (Instituto Histórico e Geográfico/RS, Instituto de Arquitetos do Brasil/RS, Sociedade de Engenharia do Rio Grande do Sul, Associação Rio-grandense de Imprensa, IPHAN/RS, IPHAE e Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil/RS). Há anos, a composição do COMPAHC ignora a Lei que regulamenta os conselhos municipais do Município, que instituiu a representação das entidades comunitárias (PORTO ALEGRE, 1992). E contradiz a própria Lei Complementar específica, que, em 2010, estabeleceu a sua composição com dezessete membros. Até hoje, não foram convocados os dois novos representantes indicados na Lei: a Associação Brasileira dos Escritórios de Arquitetura – ASBEA – e a União das Associações de Moradores de Porto Alegre – UAMPA (PORTO ALEGRE, 2010). A proporção entre os representantes institucionais e da sociedade civil pode ser verificada na Figura 2.

Fig. 2: Distribuição atual dos membros do COMPAHC de Porto Alegre. Fonte: Elaborado pela autora, 2018.

Quanto à composição dos dois conselhos, há duas instituições que atuam nos níveis nacional e municipal: o IAB e o próprio IPHAN. Há também coincidência nos representantes institucionais das áreas da educação e do meio ambiente, nos dois níveis. Fazem parte do COMPAHC: duas representações de arquitetos (embora uma não tenha sido ainda efetivada) e nenhuma representação de áreas como arqueologia ou antropologia. A ênfase incide no patrimônio edificado, justamente onde se estabeleceu um campo de disputa entre os membros da Prefeitura e das demais entidades, que estão em minoria no Conselho. Em casos polêmicos, como nos projetos referentes ao Jóquei Clube e ao Cais Mauá, a posição dos representantes é unificada e garante as votações de interesse da Prefeitura. Mesmo se os interesses da municipalidade fossem vetados no Conselho, essas decisões não teriam efeito prático, pois se trata de um conselho de caráter consultivo e não deliberativo, ou seja, o Prefeito pode simplesmente não acatar às decisões.

3 Participação e representação nas escolhas do patrimônio nacional

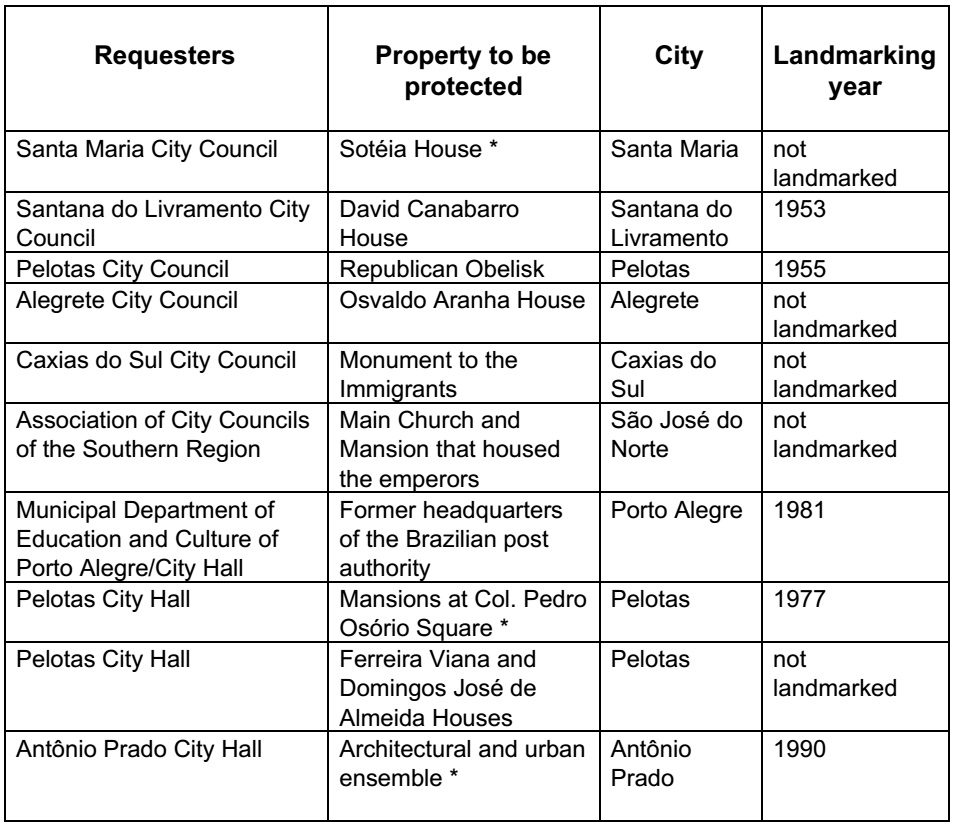

No Rio Grande do Sul, identificam-se as mudanças de políticas e de atores relacionados ao tema da preservação desde o início da atuação do IPHAN, em 1938. Como foi referido na pesquisa sobre o Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico no estado (MEIRA, 2008), a maioria dos bens tombados em nível federal, no século XX, situa-se na Região Metropolitana de Porto Alegre e na chamada “Serra Gaúcha”, que tem forte influência da colonização italiana. Aos bens tombados nas regiões de imigração não foram atribuídos valores artísticos ou históricos de forma isolada, mas sim associados aos etnográficos ou paisagísticos. No caso do Conjunto Arquitetônico e Urbano de Antônio Prado, na Figura 3, os valores atribuídos foram histórico, etnográfico e paisagístico.

Fig. 3: Conjunto arquitetônico e urbanístico de Antônio Prado, tombado em 1990. Fonte: Arquivo IPHAN-RS, 1984.

Alguns tombamentos também incidiram sobre bens situados nas regiões da fronteira sul do país. A maioria desses foi protegida pelo valor histórico, especialmente relacionado a dois episódios referenciais na trajetória sul-rio-grandense: as Missões Jesuítico-Guaraní e a Guerra dos Farrapos. Em relação ao valor histórico,

[...] parece ter havido uma disputa entre vários municípios para ver quem mais defendeu as fronteiras meridionais do Brasil, quem foi mais merecedor de reconhecimento por ter rechaçado os castelhanos, definido a nacionalidade, garantido a República, instituído as características da brasilidade, defendido o caráter moral e cívico. Trata-se sempre de discursos de reafirmação da inclusão no território brasileiro. Daí se conclui que o patrimônio como estratégia do Estado Novo para construir a nacionalidade teve muita repercussão no Rio Grande do Sul e que cumpriu essa finalidade em território gaúcho (MEIRA, 2008, p. 446).

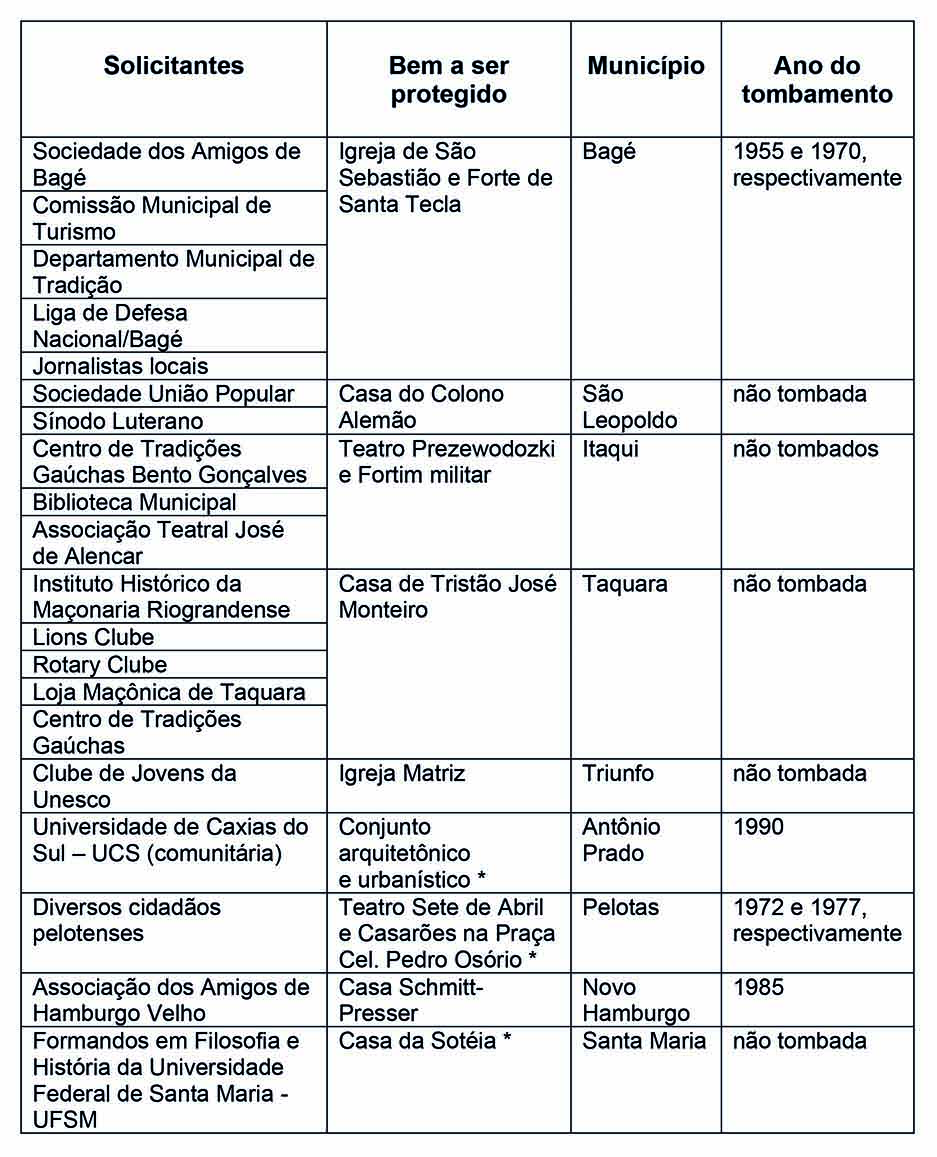

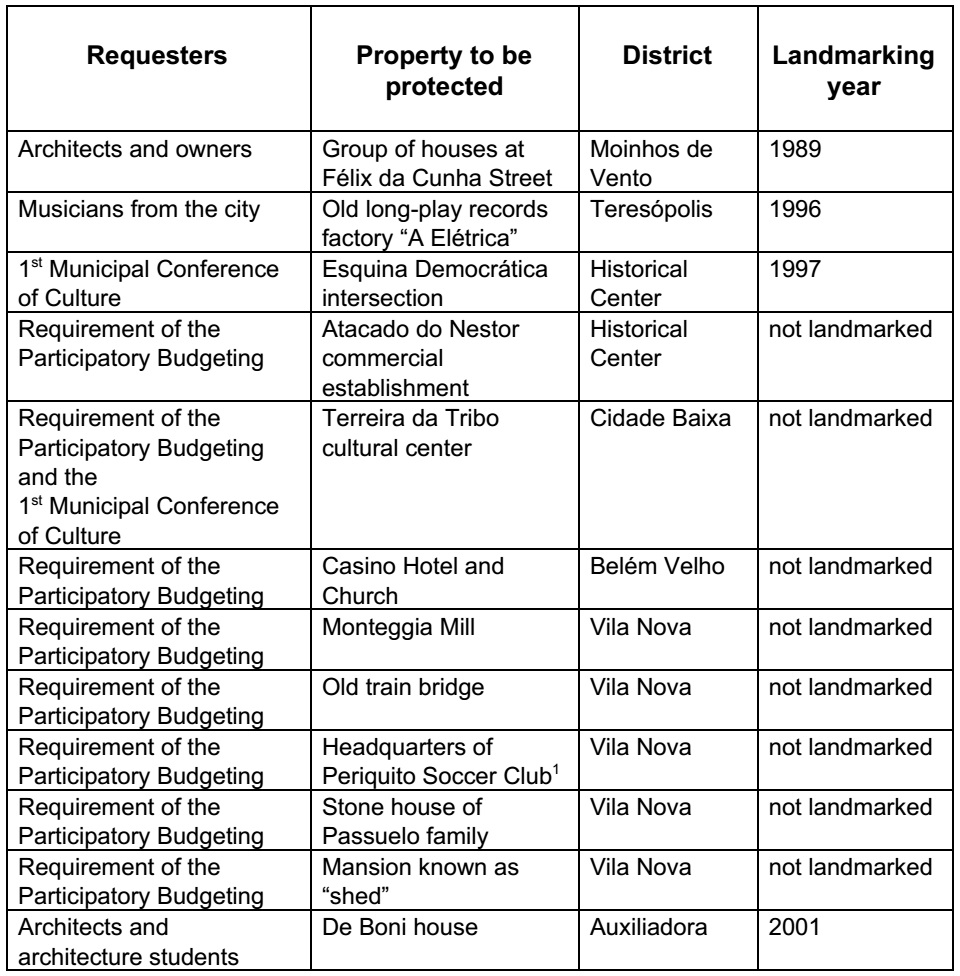

As solicitações que sugerem essas disputas foram iniciadas a partir de pedidos da sociedade civil ou de seus representantes. Foram investigados os processos de tombamento abrigados no Arquivo Noronha Santos do IPHAN, no Rio de Janeiro, que ajudaram a elucidar os trâmites dos tombamentos e verificar o resultado final do processo. Muitos processos iniciados a partir das manifestações de entidades, agremiações ou instituições enquadram-se no conceito de representação. Em outros casos, como os diversos cidadãos pelotenses, os jornalistas locais bageenses e os formandos da UFSM, que se manifestaram por meio de abaixo-assinados, a participação foi direta, conforme conceito anteriormente apresentado. Ambos os casos podem ser considerados formas de colaboração com a Instituição, uma vez que apresentavam os valores atribuídos, as justificativas e, muitas vezes, a documentação para auxiliar na instrução dos processos. A relação desses processos encontra-se no Quadro 1, a seguir:

* solicitações de tombamento que foram também encaminhadas pelos prefeitos municipais (ver Quadro 2).

Quadro 1: Solicitações diretas e de representantes da sociedade civil relativas a tombamentos federais no RS. Fonte: Elaborado pela autora com base em Meira (2008).

No Quadro 1, percebe-se que a metade dos bens cuja solicitação de tombamento foi encaminhada diretamente ou por meio de representantes não foi efetivada6. Num recorte desse universo, os abaixo-assinados dos jornalistas de Bagé, dos diversos cidadãos pelotenses e dos formandos da UFSM, que se enquadram como solicitações diretas, tiveram a maioria das solicitações atendidas. Assim, resultaram em tombamento da Igreja e do Forte, em Bagé, e do Teatro e dos casarões, em Pelotas. No caso específico de Bagé, algumas agremiações civis, representando grupos específicos da sociedade local, também reforçaram a campanha pelo tombamento da Igreja de São Sebastião e do Forte de Santa Tecla. Em Novo Hamburgo, a Associação dos Amigos de Hamburgo Velho solicitou o tombamento da Casa Schmitt-Presser, que teve prosseguimento após a interveniência da Secretaria de Cultura do MEC (SCHEFFEL, 2013)7. Esse processo mostra que pressões políticas externas também tiveram influência nas escolhas.

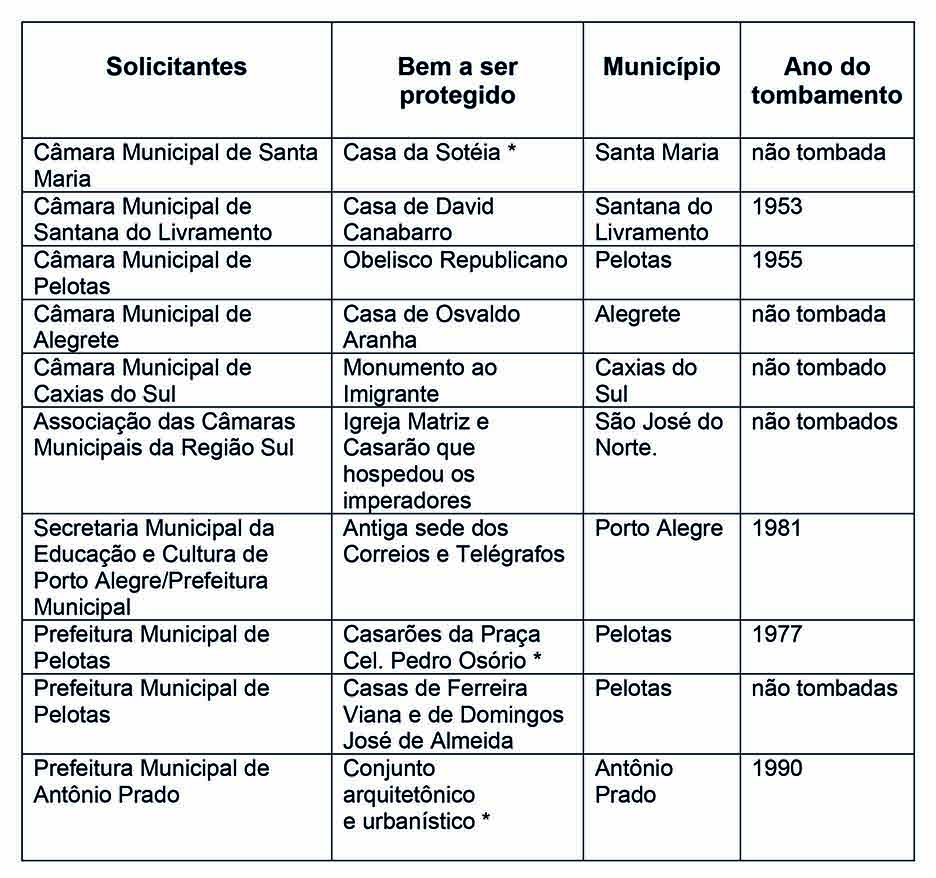

Algumas iniciativas da sociedade civil tiveram reforço das Prefeituras e das Câmaras Municipais, que, em várias regiões do estado, também encaminharam solicitações de tombamento, como pode ser constatado no Quadro 2. Nesses casos, trata-se de representantes designados por meio de processo eleitoral.

* solicitações que foram também encaminhadas por representantes da sociedade civil (ver Quadro 1).

Quadro 2: Solicitações de representantes institucionais relativas a tombamentos federais no RS. Fonte: Elaborado pela autora com base em Meira (2008).

No Quadro 2, nota-se uma participação maior das Câmaras de Vereadores do que das Prefeituras Municipais pela preservação do patrimônio em seus territórios. Hoje, praticamente inexistem iniciativas do Poder Legislativo. Constata-se que a maioria das solicitações dos representantes institucionais não resultaram em tombamentos e que poucas vieram ao encontro dos pedidos da sociedade civil mencionados anteriormente. Em dois casos, as solicitações conjuntas da sociedade civil e das Prefeituras Municipais foram atendidas: os casarões em Pelotas e o conjunto de Antônio Prado. Mas a Casa da Sotéia não foi protegida e há poucos anos deixou de existir, mesmo tendo apresentado as justificativas da Câmara de Vereadores de Santa Maria e dos formandos da UFSM (aos quais, com o passar do tempo, se somaram outros grupos). Esse caso ilustra a importância das escolhas, pois o que não é selecionado está sendo liberado para a destruição.

Não é possível generalizar, apenas com esses três casos, que seria mais efetiva uma colaboração da sociedade civil e dos poderes públicos para os tombamentos. Mas as solicitações conjuntas, inegavelmente, conferem mais tranquilidade à instituição que vai realizar o tombamento, pois fica evidenciado um apoio mais amplo no local onde vai ser efetivado o ato de proteção. As solicitações apresentadas, tanto por parte da sociedade civil quanto dos representantes institucionais, abrangeram diversas regiões geográficas do RS. Porém, foram ignorados os remanescentes das Missões Jesuítico-Guaraní (uma das fases mais importantes na história do estado), tanto do ponto de vista da formação do território quanto do ponto de vista simbólico. Merece um estudo para verificar por que a sociedade civil e os poderes públicos não se manifestaram em relação à proteção dos remanescentes missioneiros, cuja patrimonialização já era objeto de atenção desde os anos 1920.

4 Participação e representação nas escolhas do patrimônio municipal

Na primeira Lei de tombamento municipal de Porto Alegre, promulgada em 1979, inspirada no Decreto-Lei nº 25/37, foi suprimido o termo “excepcional” que consta no primeiro artigo da Lei federal. A partir desse pressuposto, a trajetória da preservação em nível municipal foi pesquisada. Os relatórios sobre as comissões municipais que serão referidas a seguir e sobre o COMPAHC estão abrigados no Arquivo Histórico Municipal Moysés Velhinho. Os processos de tombamento foram localizados na EPAHC e também foram revisitadas entrevistas com representantes do Orçamento Participativo, realizadas pela autora (MEIRA, 2004).

As ações de preservação no município ocorreram a partir de 1970, quando a Câmara de Vereadores, por meio da Lei Orgânica, determinou ao poder executivo municipal a tarefa de realizar levantamento dos bens edificados de valor histórico e cultural (PORTO ALEGRE, 1971). Essa iniciativa se alinha com a tradição das Câmaras Municipais participarem nos processos de preservação em suas cidades, como foi mostrado no Quadro 2.

Inicialmente, uma comissão formada por funcionários municipais fez a primeira listagem de elementos e bens arquitetônicos, que, em 1974, foi revisada por outra comissão. A consolidação das listagens destacou, dentre outros exemplares, casas modestas e simples que representavam as edificações locais, como a Travessa Venezianos, ilustrada na Figura 4. Os itens selecionados representavam grupos sociais distintos por meio de suas casas, lojas, clubes etc. Segundo Meira (2004, p. 79), comparando a “[...] importância do patrimônio histórico e artístico nacional para a construção da memória nacional, na década de 30, pode-se dizer que o trabalho das comissões municipais buscou a construção de uma memória local [nos anos 1970, em Porto Alegre]”. Cabe esclarecer que não houve participação da sociedade civil nas comissões que escolheram os primeiros bens patrimoniais da cidade.

Fig. 4: Modestas casas de porta e janela da Travessa Venezianos, listadas em 1974 e tombadas em 1983 em nível municipal. Fonte: Autora, 2018.

Sucederam-se leis e decretos após as listagens das comissões e a criação das estruturas administrativas de preservação do patrimônio: o COMPAHC, o Fundo do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural - FUMPAHC - e a Equipe do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural - EPAHC -, dentre outras iniciativas. Entre os bens tombados a partir de então, encontram-se desde "uma casinha" e "um cortiço" até a imponente sede da Prefeitura Municipal (MEIRA, 2004).

No planejamento urbano do município, a preservação do patrimônio edificado foi assimilada no Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Urbano - PDDU - de 1979. As edificações listadas anteriormente foram incorporadas ao Plano e outras novas foram acrescentadas, sendo-lhes atribuídos valores arquitetônico, tradicional e/ou evocativo, ambiental (no sentido de paisagístico), de uso atual, de acessibilidade, de conservação, de recorrência regional, raridade formal, raridade funcional, risco de desaparecimento, antiguidade e valor de compatibilização com a estrutura urbana (CURTIS, 1979).

Vinte anos depois, no detalhamento do Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Urbano e Ambiental - PDDUA -, a amplitude dos valores se diversificou segundo as instâncias cultural, morfológica, paisagística e funcional, valorizando as práticas sociais, relações de vizinhança, significado social, referência histórica e a existência de reconhecimento oficial prévio. O estudo implicou uma grande ampliação geográfica das áreas a serem preservadas e, também, uma ampliação de conceitos ao incorporar as práticas e significados ligados à memória coletiva (GRAEFF et al., 2003). Contudo, a regulamentação desse detalhamento, até hoje, ainda não foi aprovada na Câmara Municipal.

As reivindicações diretas pela preservação foram, aos poucos, construindo-se no âmbito municipal. As manifestações dos cidadãos começaram a reverberar nos anos 1960, segundo Giovanaz (1999). Intelectuais manifestavam-se, na imprensa, pela preservação de diversas edificações significativas, como a antiga Farmácia Carvalho, o Cine Guarany, a Capela do Bom Fim, o Solar Lopo Gonçalves, o Mercado Público e outras. As edificações eram adjetivadas como simples ou humildes.

Nos anos 1980, a participação direta da sociedade teve um acontecimento marcante com o abraço à Usina do Gasômetro, que corria o risco de ser demolida e hoje aparece junto à orla requalificada, na Figura 5. Nessa época, houve um abaixo-assinado pioneiro, por parte de arquitetos e proprietários do conjunto arquitetônico na Rua Félix da Cunha, para que fosse protegido por meio de tombamento. E, aos poucos, surgiram outras solicitações formais de tombamento por meio de abaixo-assinados.

Fig. 5: Usina do Gasômetro preservada devido ao abraço da população - listada em 1971, tombada pelo município em 1982 e pelo estado em 1983. Fonte: Autora, 2018.

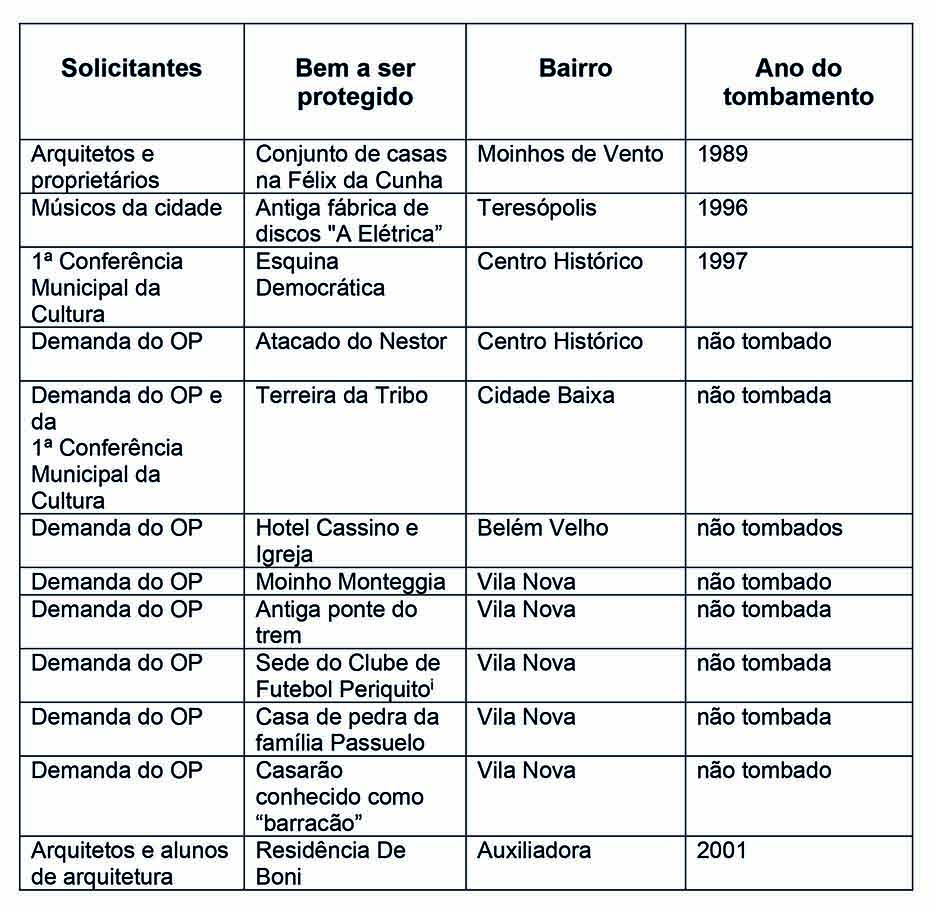

Porto Alegre é uma das poucas cidades cuja trajetória permite aprofundar os estudos em relação à participação popular direta em favor do patrimônio cultural coletivo. A partir de 19898, quando o Município começou a ampliar os espaços de participação na gestão municipal por meio do Orçamento Participativo - OP -, percebe-se que surgiram demandas sobre a preservação do patrimônio cultural em diversos bairros. Essas demandas abrangeram solicitações de tombamentos indicadas no Quadro 3, bem como restauração de edificações. Houve também dezenas de pedidos para registro da história oral das comunidades, desenvolvidos por meio do projeto denominado Memória dos Bairros.

Quadro 3: Solicitações diretas e de representantes delegados relativas a tombamentos municipais em Porto Alegre. Fonte: Elaborado pela autora, 2018.

Antes de analisar as demandas relacionadas ao tema aqui proposto, cabe esclarecer o tipo de participação que ocorreu nesse período em Porto Alegre. O OP pode ser caracterizado como um sistema de cogestão, que envolvia a administração municipal e a população. Esta tinha participação direta nas assembleias abertas, onde as demandas eram discutidas e votadas por cada indivíduo presente. Nessa etapa inicial, o número de delegados e conselheiros para as instâncias dos fóruns e conselhos era definido proporcionalmente ao número de participantes. Ficou caracterizado um modelo delegativo de representação, no qual os representantes não tinham liberdade de decisão e deviam apenas defender a vontade expressa dos representados (FEDOZZI; MARTINS, 2015). Em relação aos conceitos estabelecidos, no início, identifica-se tanto a existência da participação direta quanto da representação, neste caso, especificamente sob a forma delegativa.

Os espaços de participação passaram a apresentar temas relacionados ao patrimônio cultural material e imaterial, sendo que, nas políticas públicas municipais, a preocupação maior sempre foi com o patrimônio edificado. Para as entrevistas, foram selecionados dois representantes do OP que atuavam como delegados de bairros (MEIRA, 2004). Esses bairros, Partenon e Vila Nova, destacaram-se na apresentação das demandas relacionadas à preservação do patrimônio edificado. O depoimento de Mazzo (MEIRA, 2004, p. 124-125) ressalta o conhecimento que foi difundido entre os participantes do processo à medida que as demandas sobre o tema foram apresentadas e discutidas:

Num primeiro momento, nós, enquanto Associação [dos Moradores da Vila Nova] apresentamos as demandas – tombamento, tombamento, tombamento e aquisição [...]. Quando levamos para o fórum de delegados eles diziam: Capaz que nós vamos aprovar essas demandas da Associação [...]. Por que vocês têm que ficar derrubando esses prédios? O próprio nome tombamento dá a entender que é uma coisa para derrubar [...]. Isso levou a uma discussão onde as pessoas se apropriaram de alguma coisa que a maioria não sabia o que era. No ano seguinte, já tinham demandas dessa área, de outras comunidades. Quer dizer, acho que isso abriu espaço para as pessoas se apropriarem do patrimônio público, dos tombamentos e que aquilo se preserve para a humanidade, para a cultura toda do dia a dia.

O depoimento do delegado do Partenon apresenta a mesma percepção sobre o tema patrimonial, ressaltando que, nas discussões do OP, a população passou a conhecer mais a cidade e a sua história. Dessa forma, no entender de Marques (MEIRA, 2004, p. 120), as plenárias desempenhavam um papel educativo que oxigenava o processo:

Essa oxigenação foi bastante importante porque ela acabou devolvendo às pessoas aquele conhecimento que elas deveriam ter absorvido antes. Então esse interesse pela questão histórico-cultural da cidade, ele tranquilamente é graças à participação da população no processo. [...] Existe uma convergência de pensamento de que a questão do interesse histórico-cultural deve ser preservada e resgatada, em geral.

A representante se refere de uma maneira abrangente à demanda pela preservação dos desconhecidos marcos da imigração italiana no sul da capital, como a Casa de Pedra da Família Passuelo, apresentada na Figura 6, e o Moinho Monteggia, construído pelo imigrante que implantou a então colônia Vila Nova.

Fig. 6: Casa de pedra dos Passuelo – singelo marco que o bairro queria reconhecer por meio de tombamento. Fonte: Autora, 2018.

Mazzo explica que, nesse moinho, a intenção era implantar um centro de atividades múltiplas, como forma de devolvê-lo à comunidade:

Patrimônio para nós é uma questão importante porque nós somos uma comunidade antiga, uma comunidade centenária [...] Mas esses produtores e as pessoas que vieram com eles [os imigrantes] construíram prédios belíssimos e também tem toda uma história - por exemplo, o moinho de produção de cereais e que nós gostaríamos de preservar [...] A nossa intenção não era só tombar – era tombar, restaurar e desenvolver um centro de atividades culturais, educativas e de lazer [...] Porque é para garantir a memória, é para deixar viva toda essa história (MEIRA, 2004, p. 124).

Segundo esses depoimentos, os fóruns de participação possibilitavam que as demandas populares sobre preservação fossem socializadas. “Se não houvesse o OP, não teria como encaminhar com certeza. Nós iríamos buscar na Secretaria de Cultura? Quem nos atenderia? Que espaço nos daria?”, diz Mazzo (MEIRA, 2004, p. 125). O depoimento de Marques (MEIRA, 2004, p. 118) esclarece que: “E esse é um trabalho novo, que nós temos que fazer no OP – que cada região faça a indicação do que quer preservar, do que quer tombar para a cidade. O governo vai ter que acatar isso.” Nota-se, nesta fala, que o governo não é encarado como um ente colaborativo, pelo menos nas questões relativas à preservação dos patrimônios locais.

O tema do patrimônio cultural também foi tratado, durante a Administração Popular, nas Conferências Municipais de Cultura, criadas com o objetivo de democratizar a formulação de políticas públicas na área. Nesses fóruns, houve demandas para tombamentos da Esquina Democrática e da Terreira da Tribo. A Esquina Democrática, no cruzamento de duas vias comerciais da maior relevância para a cidade: a Rua dos Andradas e a Avenida Borges de Medeiros, situadas no centro da cidade. Salienta-se que foi a única demanda de tombamento efetivada até o momento, cuja origem foi um fórum de participação popular. Interessante que o tombamento ocorreu por meio de decreto do Prefeito Municipal, o que não é usual quando há uma lei municipal disponível para o mesmo fim. A razão desse procedimento merece uma verificação.

As discussões nos fóruns de participação incentivaram o sentimento de pertencimento à cidade, conforme o depoimento dos entrevistados, e propiciaram a emergência de demandas relacionadas às referências patrimoniais das comunidades dos bairros. Essas demandas não foram dirigidas ou fomentadas por meio de campanhas publicitárias ou programas de educação patrimonial. Surgiram espontaneamente, mas, para serem conhecidas e legitimadas, dependeram de um processo participativo (MEIRA, 2004).

No Quadro 3, aparecem também duas demandas ligadas a abaixo-assinados: a fábrica de discos “A Elétrica” e a residência De Boni. O documento relativo à primeira solicitação foi encaminhado por um grupo de músicos e de cidadãos interessados na preservação da fábrica. O segundo, assinado por arquitetos e estudantes de arquitetura. Ambas foram tombadas. Cabe perguntar por que as demandas desses grupos foram atendidas e aquelas destinadas à proteção do patrimônio arquitetônico dos bairros não tiveram sucesso, com exceção da Esquina Democrática.

Talvez as mesmas razões do que sucedeu em nível federal: algumas podem não ter correspondido aos parâmetros estabelecidos pelas instâncias técnicas do Município, outras não atenderam aos critérios de representatividade municipal ou talvez não tenham sido gerados processos que pudessem tramitar administrativamente. Pode-se considerar, então, que um processo democrático participativo é essencial para possibilitar o surgimento de demandas relacionadas à preservação do patrimônio cultural. Mas deve ser estendido às demais etapas do processo, ou seja, no encaminhamento dos trâmites burocráticos do processo até o tombamento final dos bens propostos pelas comunidades.

É inquestionável que não só os bens tombados constituem o patrimônio cultural de um lugar. Mesmo sem a nomeação oficial, retomando a referência de Bourdieu (1989), a Casa de Pedra dos Passuelo, o Moinho Monteggia, a Terreira da Tribo, o Hotel Cassino e a Igreja de Belém Velho, o Atacado do Nestor, a antiga ponte do trem e a Sede do Clube Periquito na zona sul continuam sendo referências culturais para as suas comunidades, ou seja, continuam sendo patrimônio cultural. Mas, na verdade, nem todos continuam. O Moinho Monteggia está desaparecendo, a ponte do trem foi demolida e a Sede do Clube onde despontou Ronaldinho Gaúcho não existe mais. Talvez se tivessem sido tombados, sua preservação para as gerações futuras dos bairros estaria garantida.

Também cabe referir que para além das solicitações de tombamento tratadas aqui, há diversas entidades como o IAB e o ICOMOS, cujas representações regionais colaboram intensamente para a preservação do patrimônio cultural no RS. Associações de bairros como Petrópolis Vive, Moinhos Vive e movimentos como o que busca a democratização do Cais do Porto manifestam-se pela preservação dos espaços urbanos representativos da cidade. Passeatas, abaixo-assinados e as redes sociais são meios de participação presentes hoje em dia.

Para finalizar, deve-se esclarecer que tampouco o tombamento garante, por si só, a preservação de um bem. Há dezenas de exemplos no Brasil, no Rio Grande do Sul e em Porto Alegre que mostram o contrário. A antiga fábrica de discos mencionada acima está em acelerado processo de desmoronamento e, mesmo tombada em nível municipal, não permanecerá na cidade no futuro como símbolo de sua trajetória.

5 Considerações Finais

Os exemplos de participação, de representação e de colaboração referidos no texto não esgotam o assunto. Na esfera pública, todos os âmbitos da administração – do federal ao municipal – consideram suficiente a participação da sociedade civil, em relação às políticas públicas de preservação do patrimônio cultural, por meio dos seus representantes nos conselhos específicos. Nos conselhos são avaliados, dentre outros assuntos, processos sobre tombamentos de bens culturais materiais cujas escolhas já foram realizadas. Se fossem estudados os processos de tombamento que tiveram início pelas mãos dos técnicos das instituições de preservação (no caso deste texto, o IPHAN e a EPAHC), poder-se-ia propor a hipótese de que todos, ou a maioria, foram acatados e resultaram em tombamentos. Tratam-se de imposições com as quais os cidadãos têm de concordar pois, se não concordarem, é porque não possuiriam “consciência” sobre o patrimônio.

No geral, percebe-se que quase a metade das manifestações no sentido de proteger os bens arquitetônicos em seus municípios, apresentadas nos Quadros 1 e 2 (as diretas e aquelas a partir de representantes institucionais e de representantes da sociedade civil), não foi atendida pelo IPHAN. Em Porto Alegre, por sua vez, as solicitações por meio de abaixo-assinados para tombamentos em nível municipal, ou seja, de participação direta, foram mais efetivas do que aquelas encaminhadas como demandas populares pelos participantes nas assembleias e pelos delegados através do OP ou das Conferências de Cultura, das quais apenas uma resultou em tombamento, conforme analisado no Quadro 3. Curiosamente, foi um tombamento efetivado por decreto do Prefeito Municipal e não subordinado aos trâmites da lei de tombamento vigente no município.

Pode-se dizer que os bens patrimoniais escolhidos pelos técnicos, em nome da administração, são acolhidos por todos; os bens patrimoniais escolhidos pelas comunidades populares não são acolhidos por ninguém mais além delas mesmas. Porém, ambos os olhares deveriam coexistir. É evidente, então, a importância de criar e garantir canais de participação democráticos para que demandas locais possam ser encaminhadas e tenham um trâmite garantido. Marques (MEIRA, 2004, p. 122) diz com propriedade que os conhecimentos técnico e científico e a sabedoria popular devem ser aliados, pois "Só dessa forma nós vamos conseguir enriquecer o processo".

Referências

BARROSO, G. Documentário da ação do Museu Histórico Nacional na defesa do patrimônio tradicional do Brasil. Anais do MHN, v. 5, p. 5-43, 1944.

BOURDIEU, P. O poder simbólico. Lisboa: DIFEL, 1989.

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm>. Acesso em: 31 jul. 2018.

BRASIL. Decreto nº 9238, de 15 de dezembro de 2017. Aprova a Estrutura Regimental e o Quadro Demonstrativo dos Cargos em Comissão e das Funções de Confiança do Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/decreto/D9238.htm>. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2018.

BRASIL. Decreto-lei nº 25, de 30 de novembro de 1937. Organiza a proteção do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/CCIVil_03/Decreto-Lei/Del0025.htm>. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2018.

CURTIS, J. N. B. Patrimônio ambiental urbano de Porto Alegre. In: CICLO DE PALESTRAS SOBRE PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL, 1., 1979, Porto Alegre. Anais... Porto Alegre: Prefeitura Municipal, Secretaria Municipal de Educação e Cultura, Conselho Municipal do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural, 1979. p. 37-80.

FEDOZZI, L. J.; MARTINS, A. L. B. Trajetória do orçamento participativo de Porto Alegre: representação e elitização política. Lua Nova, São Paulo, n. 95, p. 181-223, 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ln/n95/0102-6445-ln-95-00181.pdf>. Acesso em: 26 ago. 2018.

GIOVANAZ, M. Lugares de história: a preservação patrimonial na cidade de Porto Alegre (1960-1979). 1999. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Faculdade de História, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 1999.

GRAEFF, E.; BELLO, H. E.; KIEFER, F.; VARGAS, J. C.; CARUCCIO, M. Áreas especiais de interesse cultural do plano diretor de desenvolvimento urbano ambiental de Porto Alegre. In: SEMINARIO DE ARQUITECTURA LATINOAMERICANA, 10., 2003, Montevidéu. Anais… Disponível em: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317095364_Areas_Especiais_de_Interesse_Cultural_do_Plano_Diretor_de_Desenvolvimento_Urbano_Ambiental_de_Porto_Alegre>. Acesso em: 20 ago. 2018.

IPHAN. Aloísio Magalhães, o nome que inovou as políticas do patrimônio. Brasília: IPHAN, 2015. [online] Disponível em: <http://portal.iphan.gov.br/noticias/detalhes/3216>. Acesso em: 20 ago. 2018.

MEIRA, A. L. G. O patrimônio histórico e artístico nacional no Rio Grande do Sul no século XX: atribuição de valores e critérios de intervenção. 2008. Tese (Doutorado em Planejamento Urbano e Regional) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento Urbano e Regional, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2008.

MEIRA, A. L. O passado no futuro da cidade: políticas públicas e participação popular na preservação do patrimônio cultural de Porto Alegre. Porto Alegre: Ed. UFRGS, 2004.

PESCI, R. La ciudad de la urbanidad. Buenos Aires / La Plata: ASPPAN / Fundación CEPA, 1999.

PORTO ALEGRE. Lei Complementar nº 267, de 16 de janeiro de 1992. Regulamenta os Conselhos Municipais criados pelo Artigo 101 da Lei Orgânica do Município de Porto Alegre. Disponível em: <http://www2.portoalegre.rs.gov.br/cgi-bin/nph-brs?s1=000022349.DOCN.&l=20&u=/netahtml/sirel/simples.html&p=1&r=1&f=G&d=atos&SECT1=TEXT>. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2018.

PORTO ALEGRE. Lei Complementar nº 658, de 7 de dezembro de 2010. Dispõe sobre o Conselho Municipal do Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural (COMPAHC). Disponível em: <http://www2.portoalegre.rs.gov.br/cgi-bin/nph-brs?s1=000031397.DOCN.&l=20&u=/netahtml/sirel/simples.html&p=1&r=1&f=G&d=atos&SECT1=TEXT>. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2018.

PORTO ALEGRE. Lei orgânica do Município de Porto Alegre. Porto Alegre: Oficinas Gráficas do Departamento de Imprensa Oficial, 1971.

RAMOS, P. Os conceitos de participação e representatividade feminina. 2018. [online] Disponível em: <https://www.megajuridico.com/os-conceitos-de-participacao-e-representatividade-feminina/>. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2018.

SCHEFFEL, E. F. Scheffel por ele mesmo. Novo Hamburgo: Um Cultural, 2013.

1 Entre 1979 e 1982, Aloísio Magalhães foi Secretário da Secretaria do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional – SPHAN – e Presidente da Fundação Nacional Pró-Memória - braços político e executivo, respectivamente, das políticas de preservação do patrimônio. À sua gestão é atribuída a ampliação institucional do conceito de patrimônio cultural, com ênfase na diversidade cultural brasileira.

2 O reconhecimento de um bem cultural material pelo Estado, por meio do tombamento ou de outro instrumento legal, não garante totalmente a sua preservação (há centenas de bens tombados que foram mutilados ou destruídos no Brasil). Mas não os nomear oficialmente é condená-los à destruição, pois ficam à mercê dos interesses privados que se sobressaem sobre os interesses coletivos.

3 O tombamento é o ato de proteção legal de um bem patrimonial que, após passar pelas instâncias técnicas do IPHAN, é julgado pelo Conselho Consultivo e deve ser homologado pelo Ministro da Cultura antes de ser inscrito definitivamente nos Livros-tombo. No caso da Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre, após tramitar pela EPAHC, a solicitação de tombamento deve ser avaliada pelo COMPAHC e encaminhada ao Prefeito Municipal para sanção e posterior inscrição no Livro-tombo.

4 Optou-se por não inserir o IPHAE na comparação aqui apresentada (apesar da importante atuação que representa hoje no Estado), porque suas ações de proteção iniciaram apenas no final do século XX (anos 1980), recaíram majoritariamente sobre bens de propriedade pública nas primeiras décadas de atuação e até hoje não possui conselho consultivo específico na área do patrimônio cultural.

5 O Conselho Consultivo do IPHAN é uma instância muito respeitada em nível nacional pela consistência de suas posições e, particularmente, pela postura corajosa que assumiu em defesa do IPHAN, em 1990, quando a então Secretaria do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional e a Fundação Nacional Pró-Memória – conhecidas pela sigla SPHAN/Pró-Memória, foram extintas pelo Governo Collor. Após terem sido transformadas em Instituto Brasileiro do Patrimônio Cultural – IBPC, reassumiram a denominação de IPHAN a partir de 1994.

6 Não vem ao caso, aqui, aprofundar as razões dos bens que não foram tombados pelo IPHAN. Talvez alguns não correspondessem aos parâmetros artísticos da Instituição, outros não atendessem aos critérios de excepcionalidade ou de relevância nacional etc.

7 A solicitação de tombamento da Casa Schmitt-Presser foi efetivada por interveniência pessoal do Prof. Marcos Vinícios Vilaça, que, na época da solicitação de tombamento, ocupava o cargo de Secretário de Cultura do MEC. Por meio de um amigo comum, o pintor Ernesto Frederico Scheffel, líder do movimento pela preservação da Casa, encaminhou a documentação que havia reunido sobre o local diretamente ao Secretário, em Brasília. Consta que havia resistência por parte da representação do IPHAN-RS, pois o diretor regional, arquiteto Júlio N. B. de Curtis, não era favorável ao tombamento. A Secretaria de Cultura do MEC era hierarquicamente superior ao IPHAN-RS.

8 De 1989 a 2004, ocorreu a gestão da Frente Popular, na Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre, liderada pelo Partido dos Trabalhadores. A implantação do Orçamento Participativo - OP -, foi o mais conhecido fórum de participação dos cidadãos na cogestão da cidade. Inicialmente, baseava-se na divisão geográfica em regiões e era voltado principalmente à definição orçamentária do Município. Depois foram introduzidas plenárias temáticas - Educação, Cultura e outras -, bem como realizados Congressos da Cidade e encontros específicos em diversas áreas, como as Conferências da Cultura, possibilitando o desenvolvimento de várias interfaces entre a população e a administração municipal.

Participation or representation: heritage choices in Rio Grande do Sul

Ana Lúcia Goelzer Meira is an Architect and Doctor in Urban and Regional Planning. She teaches at the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brazil, in undergraduate courses, Professional Master's in Architecture and Urbanism, and Specialization in Cities: Strategic Management of the Urban Territory. She studies the preservation of urban areas, the restoration of buildings of cultural interest, and popular participation in conservation actions.

How to quote this text: Meira, A. L. G., 2019. Participation or representation: heritage choices in Rio Grande do Sul. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 18. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=5&lang=en>. [Accessed: 30 June 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 28, 2018

Abstract

The field of cultural heritage preservation is built by choices about what will be protected for the enjoyment of current and future generations. It is discussed the need for participation of civil society in these choices, either directly or by means of representatives. It was revised landmarking processes at the national level regarding Rio Grande do Sul, the southernmost state in Brazil, and requests for municipal landmarking in the capital city, Porto Alegre. The research emphasis covered the end of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st century. In both scopes, it is noticed that many manifestations for preservation of heritage were sent through participatory processes to public entities. However, it is suggested that there is a mismatch between the choices of technicians and those of social groups; the former is more easily legitimized by institutional preservation instruments and the latter, almost never. The results of the processes at the national and municipal levels are relevant and contribute to the reflection on the preservation of cultural heritage. The intention was to verify if society and its representatives participate or collaborate to build the idea of heritage preservation.

Keywords: Architectural heritage, Social participation, Heritage preservation, Participatory budgeting

1 Initial considerations on the subject

The cultural heritage preservation, which comprises material and immaterial assets as provided for in the Brazilian Constitution (Brasil, 1988), is permeated by the choices about what will be effectively protected for future Brazilian generations. These choices are based on values that vary according to the time and place. The need for direct participation of civil society or its representatives in this process has been a subject discussed for decades. One of the most known phrases from Aloísio Magalhães, during the period in which he directed the SPHAN/Pró-Memória system1, in the 1980s, already stated that community is the best keeper of its heritage (IPHAN, 2015). Despite being repeated with variations over decades, this slogan failed to permeate the preservation actions in practice. The technicians and politicians continue to control the hegemony over the choices about what will become heritage, that is, over the assets that will be acknowledged and preserved by the state. This is the official designation referred to by Bourdieu (1989)2. As a consequence, by exclusion, they also determine which assets will not be acknowledged and, therefore, are subject to disappearance. Exposing these contradictions assist in the process of democratizing choices by allowing a more diversified selection of heritage assets.

The notes presented here were based on two researches carried out by the author: one on public policies and society participation in the preservation of the cultural heritage of Porto Alegre (Meira, 2004) and the other on federal actions to protect the historical and artistic heritage in Rio Grande do Sul (Meira, 2008), both aiming at the 20th century. Cross-referencing of data can provide indications to understand what has been established as a standard to the civil society participation in public heritage policies. The comparison between the processes in the two levels of government, even if it does not exhaust the subject, can serve as a contribution to reflections on the preservation background and its interfaces with the society mobilization.

In general, the cultural heritage preservation results from technical perspectives and political interests, disregarding and disqualifying the participation of citizens. These are often attributed to ignorance of and disregard for the importance of cultural assets. In this sense, one of the great issues related to the preservation of Brazilian cultural heritage is the search for participation in decisions about what, how and for whom to preserve. As well as actively listening to the population, not in the sense of simple dissemination, but rather as a dialog to jointly understand what are the cultural references of local, regional, state or national importance.

2 Participation or representation in the choices of heritage assets

Regarding the beginning of public policies for preservation of heritage in Brazil, it is worth mentioning that the Inspection of National Monuments operated as a National Historical Museum (MHN) department between 1934 and 1937. Gustavo Barroso was the first director of the Museum and monitored the execution of some works in the historical ensemble of Ouro Preto for the Inspection (Barroso, 1944).

In 1937, the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Service – currently IPHAN – was officially implemented and Decree-Law no. 25/37 – the federal landmarking law – was signed (Brasil, 1937). The new institute, responsible for the identification, documentation, protection and promotion of Brazilian cultural heritage, was built by the modern intellectual avant-garde movement. In the early years, writers and poets (such as Mário de Andrade, Manuel Bandeira and Carlos Drummond de Andrade), historians (such as Sérgio Buarque de Holanda), anthropologists (such as Gilberto Freyre), architects (such as Lucio Costa) and others contributed to the works. In Rio Grande do Sul, the first regional representative was the modernist writer Augusto Meyer.

The choices of assets that constitute the National Historical and Artistic Heritage, by means of landmarking3, were strategic for the construction of a national identity that was univocal in the Estado Novo (New State) political regime. After a few decades, the responsibilities to preserve the Brazilian cultural legacy were shared with states and cities due to the great extension of works to be performed. Laws and institutes were created at the municipal and state levels similar to the federal level structures. Occasionally, they resulted in joint work actions, such as the Historic Cities Program in the 1970s, the Monumenta Program in the late 1990s and the Growth Acceleration Program in Historic Cities (PAC) at the beginning of the 21st century. But in general, a collective work cannot be deemed to have been performed among preservation institutes in the three levels of government. There are many political, technical, financial and other differences that hamper collaboration in balanced conditions.

At the state level of Rio Grande do Sul, the responsibilities for preservation began to be exercised by the State Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAE), an entity subordinated to the Department of Culture, Tourism, Sport and Leisure (Sedactel). At the municipal level, the Historical and Cultural Heritage Staff (EPAHC) was created and bonded to the Municipal Department of Culture of Porto Alegre. The comparison proposed in this document will analyze the federal actions of IPHAN in relation to Rio Grande do Sul and the actions of EPAHC in relation to Porto Alegre. In both cases, the emphasis will be on the participation of segments of civil society in the processes of architectural cultural heritage preservation.4

Usually, municipal actions related to the cultural heritage preservation in Brazil are restricted to the architectural and urban collections. Specific laws (such as landmarking and inventory) and urban planning instruments (such as master plans, land use laws and others) are applied. In Porto Alegre, municipal landmarking laws and urban planning have been applied since the 1970s.

In general, the public authorities allow the civil society participation by representatives in asset boards, which assess the relevance of the proposed assets for protection and have other responsibilities. In this regard, the boards operate at the end of the process, at a stage when the assets have already been chosen, studied and analyzed and the values have already been adjusted for each case and are ready to be legitimized as heritage by the vote of its board members. Is the board participation at the final stage of landmarking sufficient to ensure the preservation of the diversity of material cultural assets?

Pesci (1999) addresses three types of citizen participation with social agents: direct, indirect and experimental. The first comprises public meetings, workshops (group activities lasting longer than the previous ones) and opinion surveys. The second basically uses techniques of environmental perception and recognition of environmental pattern languages. Experimental participation seeks to simulate the model to be constructed. Representation, on the other hand, is based on the manifestations of representatives of a segment or organization, whose opinions promote the visibility of their positions. They can be elected politicians or public policy advisors and are chosen by their peers (Ramos, 2018).

The Advisory Board operates at the national level and works with IPHAN since its establishment. It currently comprises twenty-three members and the President of the Institute is deemed a permanent member (Brasil, 2017). The proportion of institutional representatives and civil society representatives is shown in Figure 1. There are nine representatives of federal entities and associations (Ministries of Education, Tourism, Cities, Environment; National Institute of Museums; Institute of Architects of Brazil; International Council on Monuments and Sites; Brazilian Archeology Society; and Brazilian Association of Anthropology), as well as thirteen professionals of noteworthy knowledge in cultural heritage related areas, whose are assigned by the President of IPHAN.

Fig. 1: Current distribution of members of the Advisory Board of IPHAN. Source: Prepared by the author, 2018.

The Council of Historical and Cultural Heritage (COMPAHC) operates at the municipal level and is articulated with the Municipal Department of Culture of Porto Alegre. It comprises fifteen members: eight representatives of the City Hall and seven representatives of entities (the Historical and Geographic Institute/Rio Grande do Sul, the Institute of Architects of Brazil/Rio Grande do Sul, the Engineering Society of Rio Grande do Sul, the Press Association of Rio Grande do Sul, IPHAN/Rio Grande do Sul, IPHAE and the Brazilian Bar Association/Rio Grande do Sul). For years, the composition of COMPAHC ignores the law that regulates the municipal boards of the city, which instituted the representation of community entities (Porto Alegre, 1992). And it contradicts the specific complementary law, which established its composition with seventeen members in 2010. To date, the two new representatives indicated in the law have not been convened: the Brazilian Association of Architecture Offices – ASBEA – and the Neighborhood Association of Porto Alegre – UAMPA (Porto Alegre, 2010). The proportion of institutional representatives and civil society representatives is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: Current distribution of members of COMPAHC of Porto Alegre. Source: Prepared by the author, 2018.

Regarding the composition of the two boards, there are two institutes that operate at the national and municipal levels: IAB and IPHAN itself. There is also a coincidence concerning the institutional representatives of the education and environmental areas at both levels. COMPAHC comprises: two representations of architects (although one position has not yet been filled) and no representation of areas such as archeology or anthropology. The emphasis is on built heritage, precisely where a field of dispute has been established between the members of the City Hall and other entities, which are outnumbered in the Board. In controversial cases, as in the projects related to the Jockey Club and Mauá Wharf, the position of the representatives is unified and ensures the votes of interest of the City Hall. Even if the interests of the city were vetoed in the Board, these decisions would have no practical effect since it is a non-deliberative advisory council, that is, the Mayor may simply not abide by decisions.

3 Participation and representation in the choices of national heritage

In Rio Grande do Sul, there were changes in policies and players related to the preservation issue since the beginning of IPHAN activities in 1938. As mentioned in the research on Historical and Artistic Heritage in the state (Meira, 2008), most of the assets landmarked at the federal level in the 20th century is located in the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre and at the so-called “Gaucho Highlands”, which has a strong influence from Italian colonization. The assets in the regions of immigration were not attributed with artistic or historical values in isolated manner, but rather associated with ethnographic or landscape values. Regarding the Architectural and Urban Ensemble of Antônio Prado, in Figure 3, the values attributed were historical, ethnographic and landscape.

Fig. 3: Architectural and urban ensemble of Antônio Prado, landmarked in 1990. Source: IPHAN-RS archives, 1984.

Some landmarking cases also covered assets located in regions at the southern border of the country. Most of them were protected due to historical value, especially two referential episodes in the history of Rio Grande do Sul: the Jesuit-Guaraní Missions and the Ragamuffin War. Regarding the historical value,

[...] there seems to have been a dispute between several cities over who most defended the southern borders of Brazil, who was most deserving of recognition for pushing the Castilians back, defining the nationality, establishing the Republic, instituting the characteristics of the “brasility”, defending the moral and civic character. They are always statements of reaffirmation of inclusion in Brazilian territory. Hence, it can be concluded that the heritage, as a strategy of the Estado Novo to build the nationality, had much repercussion in Rio Grande do Sul and it fulfilled this purpose in the Gaucho territory (Meira, 2008, p.446, our translation).

Requests that suggest these disputes have been made by civil society or its representatives. The landmarking processes filed in the Noronha Santos Archive of IPHAN, in Rio de Janeiro, were investigated. They helped to elucidate the stages of these processes and verify their final results. Many processes initiated from the manifestations of entities, associations or institutes fit in the concept of representation. In other cases, such as the several citizens of Pelotas, the local journalists of Bagé and the students of UFSM, who made their manifestations by means of petitions, the participation was direct, according to the previous concept. Both cases can be deemed as manners of collaboration with the Institution, since they had the attributed values, the justifications and, often, the documentation to assist in the instruction of the processes. A list of these processes is shown in Table 1 below:

* requests for landmarking that were also submitted by mayors (refer to Table 2).

Table 1: Direct requests and requests from representatives of civil society related to federal landmarking in Rio Grande do Sul. Source: Prepared by the author based on Meira (2008).

In Table 1, half of the assets which request for landmarking were sent directly or through representatives was not carried out5. In a given perspective of this universe, the petitions of the journalists of Bagé, the several citizens of Pelotas and the students of UFSM, which are direct requests, had the majority of requests accepted. Thus, they resulted in the landmarking of the Church and the Fort in Bagé and the Theater and the mansions in Pelotas. In the specific case of Bagé, some civil associations, representing specific groups of local society, also reinforced the campaign for the Church of Saint Sebastian and the Fort of Saint Thecla landmarking. In Novo Hamburgo, the Association of Friends of Hamburgo Velho requested the landmarking of the Schmitt-Presser House, which was made after the intervention of the Department of Culture of MEC (Scheffel, 2013)6. This process shows that external political pressures have also influenced the choices.

Some civil society initiatives have been reinforced by City Halls and City Councils which, in several regions of the state, have also submitted requests for landmarking, as shown in Table 2. In both cases, these representatives are appointed by electoral process.

* requests that were also submitted by representatives of civil society (refer to Table 1).

Table 2: Requests from institutional representatives related to federal landmarking in Rio Grande do Sul. Source: Prepared by the author based on Meira (2008).

Table 2 shows a greater participation of the City Councils compared to City Halls for the heritage preservation in their territories. Today, there are virtually no initiatives from the Legislative Branch. It is noted that most of the requests made by the institutional representatives did not result in landmarking and that few met the civil society requests mentioned above. In two cases, joint requests from civil society and City Halls were accepted: the mansions in Pelotas and the ensemble of Antônio Prado. But the Sotéia House was not protected and a few years ago it ceased to exist, even though there were justifications from the City Council of Santa Maria and the students of UFSM (to which, over time, other groups joined). This case illustrates the importance of choices, because what is not selected is released for destruction.

One cannot generalize, with only these three cases, that collaboration between civil society and the public authorities would be more effective for landmarking. However, without doubt, joint requests give more peace of mind to the institution that will carry out the landmarking process, since there is evidence of broader support in the place where the protection act will be performed. The requests from civil society and institutional representatives covered several geographic regions of Rio Grande do Sul. But the remaining elements of the Jesuit-Guarani Missions (one of the most important phases in the history of the state) were ignored, both from the points of view of territory formation and symbolic meaning. It deserves a study to verify why civil society and the public authorities did not manifest themselves towards the protection of the remaining elements from these missions, which preservation had been object of attention since the 1920s.

4 Participation and representation in the choices of municipal heritage

The term “exceptional”, which is found in article one of the federal law, was not include in the first municipal landmarking law of Porto Alegre, promulgated in 1979 and inspired by Decree-Law no. 25/37. The preservation background at municipal level was researched from this assumption. The reports on the municipal commissions that will be referred to below and about COMPAHC are situated in the Municipal Historical Archive Moysés Velhinho. The landmarking processes were located in EPAHC and interviews with representatives of the Participatory Budgeting were revisited by the author (Meira, 2004).

The preservation actions in the city occurred from 1970, when the City Council, by means of the Organic Law, assigned to the municipal executive branch the task of surveying the constructed assets of historical and cultural value (Porto Alegre, 1971). This initiative is aligned to the tradition of the City Councils of participating in the preservation processes in their cities, as shown in Table 2.

Initially, a commission comprising municipal employees made the first listing of architectural elements and assets, which was revised by another commission in 1974. The consolidation of listings emphasized, among other examples, modest and simple houses that represented the local buildings, such as the Venezianos Lane, shown in Figure 4. The selected items represented distinct social groups by means of their houses, shops, clubs, etc. According to Meira (2004, p.79, our translation), by comparing “the importance of the national historical and artistic heritage for the construction of national memory in the 1930s, one can say that the work of the municipal commissions sought to construct a local memory [in the 1970s in Porto Alegre]”. It is worth emphasizing that there was no participation of civil society in the commissions that chose the first heritage assets of the city.

Fig. 4: Modest door-and-window houses at Venezianos Lane, listed in 1974 and landmarked in 1983 at the municipal level. Source: Author, 2018.

Laws and decrees followed the listings of the commissions and the creation of administrative structures for heritage preservation: COMPAHC, the Historical and Cultural Heritage Fund (FUMPAHC), the Historical and Cultural Heritage Staff (EPAHC), and other initiatives. The assets that have been landmarked since then include elements from “a little house” and “a tenement” to the imposing headquarters of the City Hall (Meira, 2004).

The urban planning of the city assimilates the built heritage preservation in the Master Plan of Urban Development (PDDU) of 1979. The buildings previously listed were incorporated into the Plan and new ones were added. They received values in terms of architecture, traditional and/or evocative meaning, environment (in the sense of landscape), current use, accessibility, conservation, regional recurrence, formal rarity, functional rarity, risk of disappearance, time of existence and compatibility value with the urban structure (Curtis, 1979).

Twenty years later, in the detailing of the Master Plan of Urban and Environmental Development (PDDUA), the scope of values was diversified according to cultural, morphological, landscape and functional instances, valuing social practices, neighborhood relations, social meaning, historical reference and the existence of previous official acknowledgment. The study implied a great geographical extension of the areas to be preserved and, also, an amplification of concepts when incorporating the practices and meanings related to collective memory (Graeff, et al., 2003). However, the regulation of this detailing process has not yet been approved by the City Council to date.

Direct claims for preservation were gradually built at the municipal level. Citizen manifestations began to reverberate in the 1960s, according to Giovanaz (1999). Intellectuals expressed their opinions in the press for the preservation of several significant buildings, such as the old Carvalho Pharmacy, the Guarany Cinema, the Bom Fim Chapel, the Lopo Gonçalves Manor House, the Public Market and others. The buildings were depicted as simple or humble.

In the 1980s, the direct participation of society promoted a historic event: the embrace to the Gas Holder Plant, which was at risk of being demolished and today remains next to the requalified waterfront, as shown in Figure 5. At that time, a pioneer petition was promoted by architects and owners of the architectural ensemble at Félix da Cunha Street in order to protect it by landmarking. Gradually, other formal requests for landmarking were made by means of petitions.

Fig. 5: The Gas Holder Plant, preserved due to the embrace of the population. It was listed in 1971, landmarked by the city in 1982 and by the state in 1983. Source: Author, 2018.

Porto Alegre is one of the few cities which history allows to deepen the studies on the direct popular participation in favor of the collective cultural heritage. From 19897, when the city began to expand the spaces of participation in municipal management by means of Participatory Budgeting (OP), it is noticed that there have been demands on the preservation of cultural heritage in several neighborhoods. These demands included requests for landmarking indicated in Table 3, as well as restoration of buildings. There were also dozens of requests to record the oral history of the communities, developed through a project named Memória dos Bairros (Memories from the Neighborhoods).

Table 3: Direct requests and requests from assigned representatives related to municipal landmarking in Porto Alegre. Source: Prepared by the author, 2018.

Before analyzing the demands related to the proposed subject in this document, it is worth clarifying the type of participation that occurred in this period in Porto Alegre. The OP can be characterized as a co-management system, which involved the municipal administration and the population. The latter had direct participation in the open meetings, where the demands were discussed and voted by each person. At this early stage, the number of representatives and advisors for the instances of forums and councils was defined in proportion to the number of participants. It was characterized a delegative model of representation, in which the representatives had no freedom of decision and should only defend the expressed will of the parties represented (Fedozzi and Martins, 2015). Regarding the concepts established in the beginning, both the existence of direct participation and representation are identified, specifically in the delegative form in this case.

The spaces of participation began to present subjects related to material and immaterial cultural heritage. In the municipal public policies, the greatest concern has always been the built heritage. Two representatives of the OP, that operated as representatives of neighborhoods, were selected for the interviews (Meira, 2004). These neighborhoods, Parthenon and Vila Nova, stood out in the presentation of demands related to the preservation of the built heritage. Mazzo’s statement (Meira, 2004, p.124-125, our translation) emphasizes the knowledge that was disseminated among the participants of the process as the demands on the subject were presented and discussed:

At first, we, as the [Neighborhood] Association [of Vila Nova], presented the demands – landmarking, landmarking, landmarking and acquisition [...]. When we submitted them to the forum of representatives, they said: We will not approve these demands of the Association [...]. Why do you want to landmark these buildings? The word landmark itself implies that they will go down [...]. This led to a discussion where people became aware of something that most did not know. In the following year, there were demands from this area, from other communities. I mean, I think this allowed people to be aware of public heritage, landmarking and that it must be preserved for humanity, for the whole everyday culture.

The statement of the Parthenon representative presents the same perception on the heritage subject, emphasizing that the population became more aware of the city and its history in the discussions of the OP. Thus, according to Marques (Meira, 2004, p.120, our translation), the meetings played an educational role that oxygenated the process:

This oxygenation was very important because it gave back to people the knowledge they should have absorbed earlier. So this interest in the historical-cultural issue of the city is due to the participation of the population in the process. [...] There is a convergence of thought that the issue of historical-cultural interest must be preserved and redeemed in general.

The representative referred in a comprehensive manner to the demand for preservation of the unknown milestones of Italian immigration in the south region of the capital city, such as the Stone House of Passuelo Family, shown in Figure 6, and the Monteggia Mill, built by the immigrant man who implemented the then Vila Nova colony.

Fig. 6: Stone house of Passuelo family – simple milestone that the neighborhood wanted to acknowledge by landmarking. Source: Author, 2018.

Mazzo explains that the intention was to implement a center of multiple activities in this mill, as a way to return it to the community:

Heritage is an important issue because we are an old community, a centennial community [...]. But these producers and the people who came with them [the immigrants] have built beautiful buildings that also have a whole story – for example, the grain mil – that we would like to preserve [...]. Our intention was not only landmarking it – it was landmarking, restoring and developing a center of cultural, educational and leisure activities [...]. This is to ensure the memory, is to make this whole story alive (Meira, 2004, p.124, our translation).

According to these statements, the participation forums made it possible for popular demands on preservation to be socialized. “If there was no OP, it would not be possible to submit them with certainty. Should we consult the Department of Culture? Who would talk to us? What space would them give us?”, says Mazzo (Meira, 2004, p.125, our translation). The statement of Marques (Meira, 2004, p.118, our translation) says that: “And this is a new work that we have to do in the OP – that each region indicates what it wants to preserve, what it wants to landmark for the city. The government will have to accept it”. It is noted in this sentence that the government is not seen as a collaborative entity, at least in matters relating to the preservation of local heritage.

The cultural heritage subject was also discussed during the People Administration in the Municipal Cultural Conferences, created in order to democratize the formulation of public policies in the area. In these forums, there were demands for landmarking of the Esquina Democrática intersection and the Terreiro da Tribo cultural center. The Esquina Democrática intersection is located at the crossroad of two commercial routes of great importance to the city: Andradas street and Borges de Medeiros avenue in the center of the city. It is worth emphasizing that this was the only demand for landmarking that was carried out up to date. It was originated in a popular participation forum. An interesting fact is that the landmarking process occurred by decree of the Mayor, which is not usual when there is a municipal law available for the same purpose. It is worth analyzing the reason for this procedure.

The discussions in the participation forums encouraged the feeling of belonging to the city, according to the interviewees’ statements, and led to demands related to the heritage references of the communities in the neighborhoods. These demands were not directed or fomented by publicity campaigns or heritage education programs. They emerged spontaneously, but depended on a participatory process to be known and legitimized (Meira, 2004).

Table 3 also shows two demands related to petitions: the long-play records factory “A Elétrica” and the De Boni house. The document concerning the first request was sent by a group of musicians and citizens interested in preserving the factory. The other document was signed by architects and architecture students. Both were landmarked. It is worth asking why the demands of these groups were met and those intended to the protection of the architectural heritage of the districts were not successful, with the exception of the Esquina Democrática intersection.

Perhaps the same reasons of what happened at the federal level: some may not have met the established parameters by the technical instances of the city, others did not meet the criteria of municipal representativeness or perhaps processes that could be administratively processed have not been generated. Therefore, a participatory democratic process is essential to allow the occurrence of demands related to the preservation of cultural heritage. But it must be extended to the other stages of the process, that is, in the submission of the bureaucratic procedures of the process until the final landmarking of the assets proposed by the communities.

There is no doubt that not only the landmarked assets comprise the cultural heritage of a place. Even without the official designation, returning to the reference of Bourdieu (1989), the stone house of Passuelo Family, the Monteggia mill, the Terreiro da Tribo cultural center, the Casino Hotel and the Church of Belém Velho, the Atacado do Nestor commercial establishment, the old train bridge and the headquarters of Periquito Soccer Club in the south zone continue to be cultural references for their communities, that is, they continue to be cultural heritage. However, others do not continue to be. The Monteggia mill is disappearing, the train bridge has been demolished and the headquarters of the club where Ronaldinho Gaúcho made his name no longer exists. If they had been landmarked, perhaps their preservation for future generations of the neighborhoods would be ensured.

It is also worth mentioning that, in addition to the landmarking requests addressed in this document, there are several entities such as IAB and ICOMOS which regional representations collaborate intensely for the preservation of cultural heritage in Rio Grande do Sul. Neighborhood associations such as Petrópolis Vive and Moinhos Vive and movements such as the one that seeks the democratization of the Port Wharf are manifested by the preservation of the representative urban spaces of the city. Rallies, petitions, and social networks are current means of participation.

Finally, it is worth clarifying that landmarking alone does not ensure the preservation of an asset. There are dozens of opposite cases in Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul and Porto Alegre. The aforementioned old long-play records factory is in severe process of collapse and, despite being landmarked at the municipal level, it will not remain in the city in the future as a symbol of its history.

5 Final Considerations