Conversas entre arquitetos e engenheiros no ensino de projeto

Marina Ferreira Borges é Arquiteta e Engenheira Civil, Mestre em Engenharia de Estruturas. Pesquisadora da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Estuda ensino de projeto, concepção estrutural, possibilidades de uso das ferramentas digitais emergentes.

Como citar esse texto: BORGES, M. F. Conversas entre arquitetos e engenheiros no ensino de projeto. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 18, 2019. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=9&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 15 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 28 DE AGOSTO DE 2018

Resumo

Os planos de ensino das disciplinas de estruturas nos cursos de arquitetura enfatizam que o diálogo entre os profissionais é o que deve ser suscitado como o ponto de conexão entre a concepção da morfologia estrutural a ser realizada pelo arquiteto e sua validação e construção pelo engenheiro civil. No entanto, estaria esse diálogo ocorrendo de fato? A proposta deste trabalho é investigar através do modelo conversacional proposto por Paul Pangaro (2009), baseado na Teoria da Conversação de Gordon Pask (1976a), se de fato ocorre um processo dialógico entre disciplinas de projeto e estruturas nos cursos de arquitetura, ou se haveria possibilidade de proposição de um novo modelo conversacional, promovendo procedimentos de participação e colaboração transdisciplinar.

Palavras-Chave: Ensino de Arquitetura, Ensino de projeto, Ensino de estrutura, Modelo conversacional, Teoria da Conversação, Cibernética

1 Introdução

O ensino de estruturas é uma peça chave para que os estudantes de arquitetura pensem as relações entre forma, materialidade e tectônica, já que auxilia no raciocínio do processo de projeto físico e processual, levando a um ponto de convergência entre as disciplinas de projeto e estruturas, cuja falta de organicidade só acentua a fragmentação entre projeto e construção. O ensino de estruturas na arquitetura não é um fim em si, como nos cursos de engenharia que formam profissionais que desenvolvem cálculos estruturais. Ele deve ser um meio para que o estudante pense na tectônica1 da forma. A fragmentação entre as disciplinas de projeto e estruturas corroboram para um pensamento projetual atectônico2, favorecendo a aplicação simplista da técnica e a geração de imagens da moda (FRAMPTON, 1995).

Ao longo de décadas, o ensino de estruturas ocupou, na formação dos arquitetos, um treinamento para a rotina de projetistas e calculistas, em que não existe um conhecimento crítico, reflexivo e dialógico (SANTOS; KAPP, 2014). Com disciplinas focadas majoritariamente em aspectos quantitativos, estas são demasiadamente abstratas, e não instrumentam os estudantes de arquitetura com ferramentas adequadas para se apropriarem da relação entre o comportamento do material e o sistema estrutural desenvolvido. Sendo assim, eles não conseguem desenvolver um raciocínio estrutural a partir de uma compreensão analítica das diversas soluções possíveis diante de um determinado problema de projeto.

No entanto, os planos de ensino das disciplinas de estruturas ofertadas nos cursos de arquitetura enfatizam que o diálogo entre os profissionais é o que deve ser suscitado como o ponto de conexão entre a concepção da forma estrutural, a ser realizada pelo arquiteto, e sua validação e construção, pelo engenheiro civil. Porém, na prática de ensino, estaria ocorrendo efetivamente este diálogo pretendido entre as disciplinas de projeto e estruturas?

Para realizar esta análise, propomos como metodologia o modelo conversacional de Pangaro (2009) baseado nos conceitos desenvolvidos pela Teoria da Conversação de Gordon Pask (1976a). Dessa maneira, será organizado um modelo conversacional adaptado para analisar a relação entre o ensino de projeto e o ensino de estruturas, com o objetivo de identificar os problemas existentes no modelo vigente. Com isto, poderá ser proposto um modelo conversacional entre estas disciplinas que efetivamente permita uma prática dialógica de projetação, instrumentando os arquitetos para elaborarem novos sistemas de projeto que propiciem uma prática de construção coletiva do conhecimento através de processos participativos3 e colaborativos4, em que a arquitetura se torne um saber, e não uma disciplina autônoma (MONTANER, 2017).

2 Teoria da Conversação

A Teoria da Conversação foi desenvolvida por Gordon Pask (1976a) e se originou de uma estrutura cibernética5, em que a idéia fundamental é que o aprendizado ocorre por meio de conversações sobre a matéria da disciplina, tornando o conhecimento explícito. Pask define conversação como “intersecção entre dois sistemas de segunda-ordem6, nos quais humanos, máquinas e ambientes podem estar engajados em trocas de informação colaborativas.” A cibernética de segunda-ordem aplicada ao projeto o coloca como uma conversação em que os participantes devem aprender juntos. Segundo Pask (1980), a Teoria da Conversação é utilizada para ilustrar um argumento em favor das teorias reflexivas e relativistas na cibernética e nos estudos dos sistemas. A linguagem na Teoria da Conversação é fundamental, em que, através de um meio de processamento, tem como propriedade a habilidade de questionar, comandar, responder, obedecer e explicar um determinado objetivo.

Dubberly e Pangaro (2009) utilizam os modelos cibernéticos da teoria da conversação de Gordon Pask porque eles são baseados em um estudo profundo da interação entre humanos-humanos e humanos-máquinas. Nele, acredita-se que somente na conversa é possível aprender novos conceitos, compartilhar e evoluir conhecimentos, e confirmar concordância. Na conversação, a saída (output) de um sistema de aprendizagem torna-se a entrada (input) para outro.

Nos sistemas de conversação, baseados na teoria cibernética, humanos, máquinas e ambientes podem estar engajados em trocas de informações colaborativas. Para Dubberly e Pangaro (2009), o processo de conversação ocorre quando seus participantes executam as seguintes tarefas:

1. Abrem um canal de conversa enviando uma mensagem inicial que seja de interesse comum;

2. Comprometem-se a se envolverem com um comprometimento simétrico entre participantes;

3. Constroem significado, em que a base da conversação deve ser o compartilhamento de contextos, com linguagem e normas sociais comuns;

4. Evoluem, já que a conversa afeta ambos os participantes, em que as mudanças trazidas pelas conversas têm valor duradouro;

5. Converge para um acordo através de objetivos comuns;

6. Desenvolvem relações de cooperação.

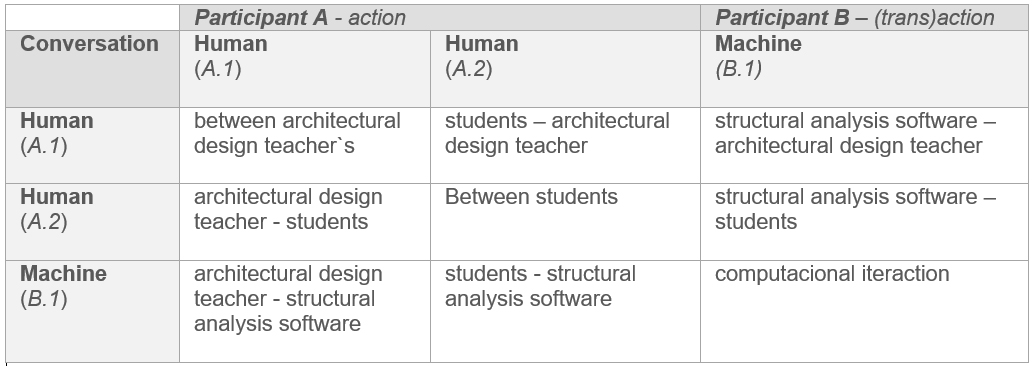

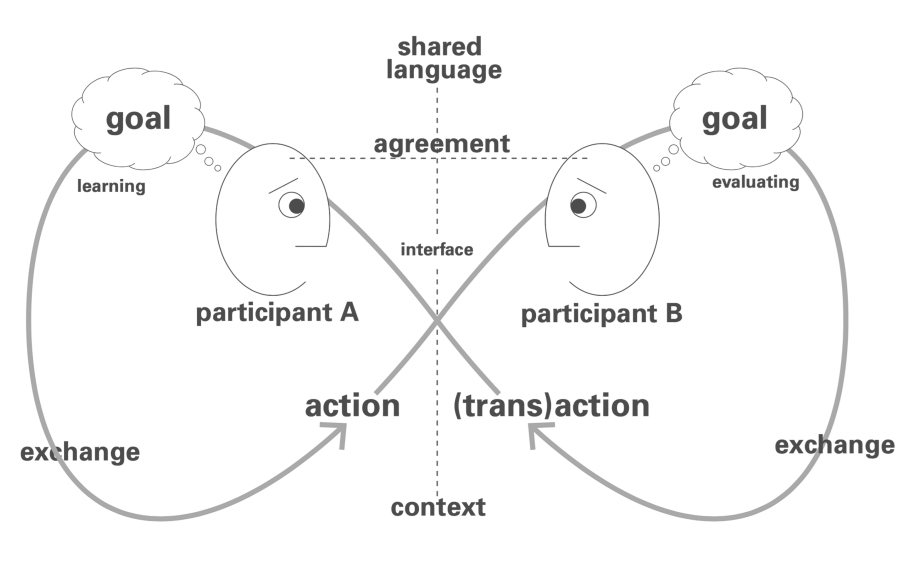

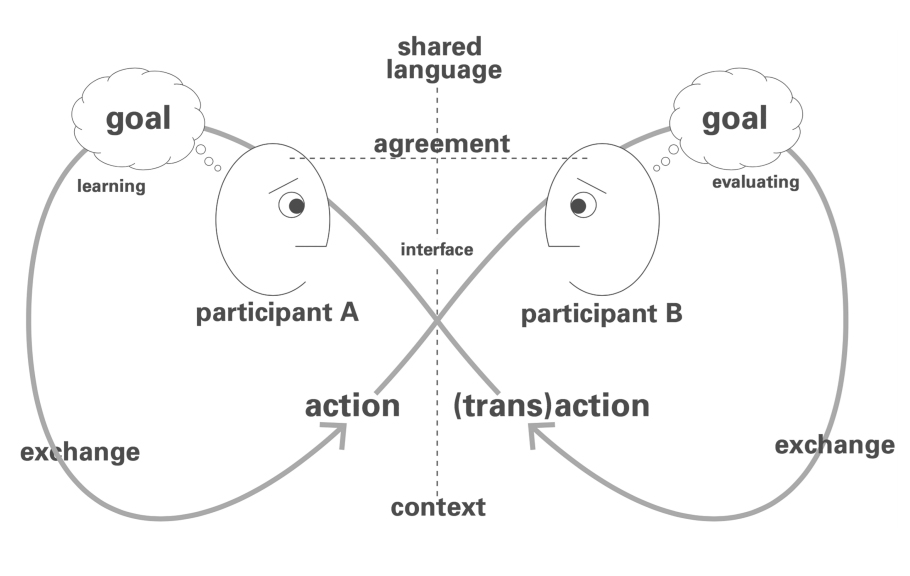

A Teoria da Conversação aplicada à prática de ensino exige que a estrutura desenvolvida deva ter uma ciclicidade que permite ao aluno reconstruir um conceito e ter consistência, permitindo que todos os tópicos abordados possam ser identificados separadamente (PASK, 1976b), abrindo novos processos de conversação. No modelo de conversação proposto por Pangaro (2009), apresentado na Figura 1, o Participante A é o que inicia o processo de colaboração através da conversação, estabelecendo os objetivos iniciais de acordo com o seu ponto de vista, articulando a lógica de condução da conversa, considerando que novos objetivos e novas oportunidades podem surgir durante o processo. O Participante A tem acesso à estrutura de aprendizagem, mas é ignorante com relação a alguns tópicos. O Participante B deve dar respostas às perguntas do Participante A fornecendo as demonstrações adequadas (PASK,1976b). A conversação inicia-se somente quando um dos participantes tem algum tipo de objetivo, específico ou geral, estando este articulado ou sem forma.

Fig. 1: Diagrama dos fundamentos da conversação. Fonte: Pangaro, 2017. Disponível em: <http://www.pangaro.com/published/Pangaro%E2%80%93Questions-for-Conversation_Theory_In_One_Hour-Kybernetes_2017.pdf>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

Sendo assim, Pangaro (2009) sistematiza o que seria um modelo conversacional e estabelece alguns requisitos para sua organização:

Contexto: momento, situação, lugar ou história compartilhada;

Linguagem: meio compartilhado inicial para transmitir significado;

Acordo: entendimento compartilhado dos conceitos, intenções, valores que levam a uma ação;

Engajamento: disponibilidade para a interação, resultado de uma linguagem compartilhada e um contexto propício para a interação que pode construir um acordo;

Ação e (Trans) ação: fluxo da conversação cooperativa, sendo esta circular e recursiva.

3 Análise da prática de ensino atual

No ensino de estruturas atualmente ofertado no curso de arquitetura7, o que existe é uma comunicação técnica. Para Pask (apud PANGARO, 2017), a diferença entre comunicação e conversação é que, para o diálogo ocorrer, algo deve ser transformado para um ou mais participantes, seja a compreensão do assunto, conceitos, intenções ou valores. Se esta transformação não ocorre, o que aconteceu foi uma mera troca de mensagens.

O modelo atual de ensino de estruturas é fragmentado em disciplinas que seguem um percurso similar ao do ensino de engenharia, tendo disciplinas de fundamentação teórica (introdução aos sistemas estruturais), conhecimento intermediário (análise estrutural e resistência dos materiais) e conhecimento avançado específico (concreto, aço e madeira). Todas as disciplinas possuem, como viés, a análise estrutural pelo método analítico, ou seja, através do uso de equações matemáticas. Os métodos experimentais, focados no desenvolvimento de modelos físicos, e os métodos computacionais, que permitem uma melhor visualização do comportamento físico dos modelos, não são utilizados. Dessa maneira, os alunos são instrumentalizados apenas com uma linguagem matemática abstrata e de difícil aplicação. Dessa forma, estaria a linguagem matemática e abstrata utilizada para o ensino de estruturas na arquitetura sendo suficiente para o estabelecimento de uma prática conversacional?

No ensino de arquitetura, as disciplinas de projeto desejam aprender sobre estruturas para definições de espacialidade, morfologia e materialidade da construção. O papel do ensino de estruturas é o da ação cooperativa com o diálogo a ser estabelecido. Desta forma, neste diálogo, o ensino de projetos é o Participante A (o que inicia a conversa com uma ação) e o ensino de estruturas é o Participante B (o que reage a esta ação com uma transação).

O objetivo deste diálogo deveria ser o de propiciar ao arquiteto conhecimento estrutural que permita flexibilizar parâmetros estruturais em consonância com a articulação espacial. A estrutura em uma concepção tectônica do processo de projeto não é um objeto autônomo que deve se adequar ao espaço ou vice-versa. O ensino de projetos é (ou deveria ser) o condutor da conversação entre agentes, promovendo a abertura de canais comuns de conversação. No modelo de ensino atual, não existe um ambiente formalizado para que se efetive a conversação com o ensino de estruturas.

Dessa maneira, primeiramente analisaremos a prática de ensino atual pelo viés do modelo conversacional, verificando se existe conversação entre o ensino de projetos e ensino de estruturas dentro do contexto de cada disciplina:

Participante A: Ensino de Projetos

Contexto: disciplinas de projetos;

Linguagem: métodos de representação manuais ou digitais do projeto arquitetônico;

Acordo: lançamento da estrutura seguindo critérios de pré-dimensionamento;

Engajamento: quando ocorre, se dá através da análise de exemplos e contra-exemplos de soluções estruturais de obras análogas. Também pode ocorrer consulta a bibliografia específica de conhecimentos estruturais direcionada para a aprendizagem de arquitetos;

Ação: praticamente não ocorre. Depende de uma vontade individual de professores de projetos e alunos para buscarem algum contato com os professores de estruturas.

Participante B: Ensino de Estruturas

Contexto: disciplinas de estruturas;

Linguagem: matemática através de método analítico;

Acordo: conforme as ementas das disciplinas são oferecidas apenas noções básicas dos conteúdos de tal maneira que os arquitetos consigam realizar um pré-dimensionamento estrutural e dialogarem com engenheiros de estruturas na prática profissional;

Engajamento: a inadequação da aplicação da linguagem ao desenvolvimento de projetos não possibilita o engajamento;

(Trans)ação: praticamente inexistente, já que não ocorre engajamento, dificultado pela linguagem utilizada.

No modelo atual, não há possibilidades de feedbacks, sendo criado um processo de causalidade linear. De acordo com Dubberly e Pangaro (2015a), este processo linear não permite a iteração, que seria a correção do erro, e a convergência de objetivos entre os agentes participantes, limitando o projeto a feedbacks simplificados. Dessa maneira, para a proposição de um modelo conversacional entre o ensino de projetos e estruturas, é importante que haja um contexto que propicie a possibilidade de múltiplos feedbacks, promovendo circularidade e recursividade. Para isso, é fundamental que haja a interação do Participante B no contexto do Participante A, desenvolvendo uma linguagem comum, com objetivos explícitos, em um contexto que facilite as trocas, em que estes servirão como base para uma ação conjunta e para criação de novos valores.

4 Proposta de Modelo Conversacional

A cibernética estuda como os sistemas se organizam, tratando de como estes se comunicam internamente e com outros sistemas, o que propicia um pensamento transdisciplinar colaborativo, sendo este inclusive, estimulado. Para Von Foerster (apud DUBBERLY; PANGARO, 2015b, p.5), “alguém pode e deve tentar comunicar cruzando as fronteiras, e muitas vezes os abismos, que separam as várias ciências”.

Algumas tentativas de promover esta integração vêm sendo desenvolvidas para a melhoria do diálogo entre ensino de projetos e ensino de estruturas. Conforme pôde ser visto no III Eneeea8, algumas universidades brasileiras enfocam na mudança de linguagem (métodos experimentais com o uso de modelos físicos ou experiências em canteiros experimentais), outras no envolvimento de novos participantes (professores da engenharia presentes nas disciplinas de projeto), ou ainda, na proposição de um novo modelo conversacional.

No entanto, estas proposições têm como enfoque a comunicação técnica, não apresentando maiores reflexões com relação acerca das mudanças da própria arquitetura e da sua condição contemporânea. Para Montaner (2016), a arquitetura contemporânea possui um caráter de síntese contextualista e complexo, em que emerge um novo pragmatismo reformulado por meio de ferramentas práticas de conhecimento, análise e projeto. Para Montaner, as práticas diagramáticas e as ferramentas digitais propiciam o desenvolvimento de uma teoria arquitetônica relacionada a um pragmatismo interativo. Pangaro (2011) acredita que o desenvolvimento do projeto deva se preocupar mais com a estrutura do sistema do que com a forma dos objetos, e que, sem a criação de uma nova linguagem, a inovação é limitada a melhorias nos processos existentes. Mas como desenvolver uma nova linguagem?

A proposta de um novo modelo conversacional entre o ensino de projetos e estruturas busca a promoção de uma linguagem comum entre os participantes, para que assim seja possível que as trocas sejam efetivamente realizadas. Para tanto, é fundamental que o Participante B promova sua (trans)ação dentro do mesmo ambiente do ensino de projetos (Participante A). O Participante B pode ser máquina (uso de softwares de análise estrutural) ou homem (professor de estruturas). Dessa forma, as conversas propostas tratam de promover a interação homem-máquina, ou, ainda, homem-máquina-homem.

5 Conversa homem-máquina

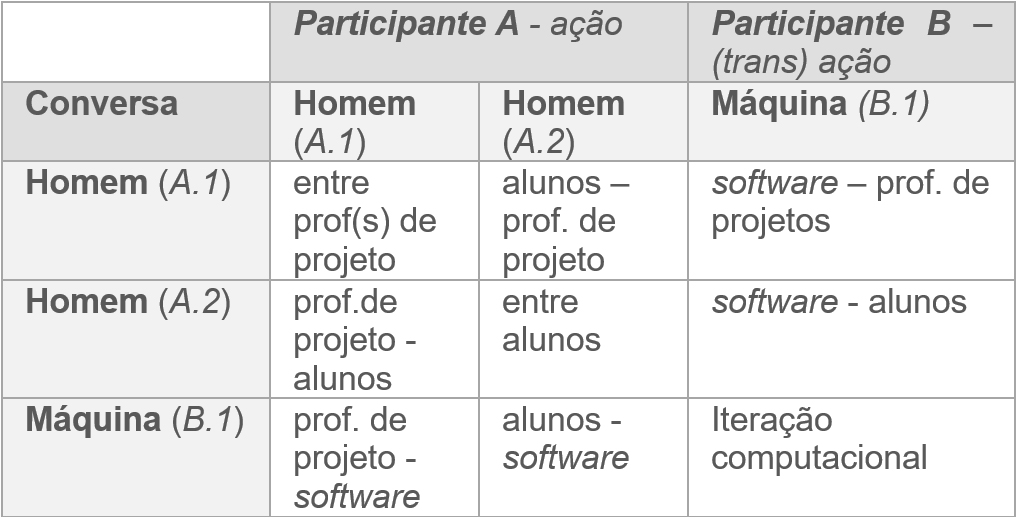

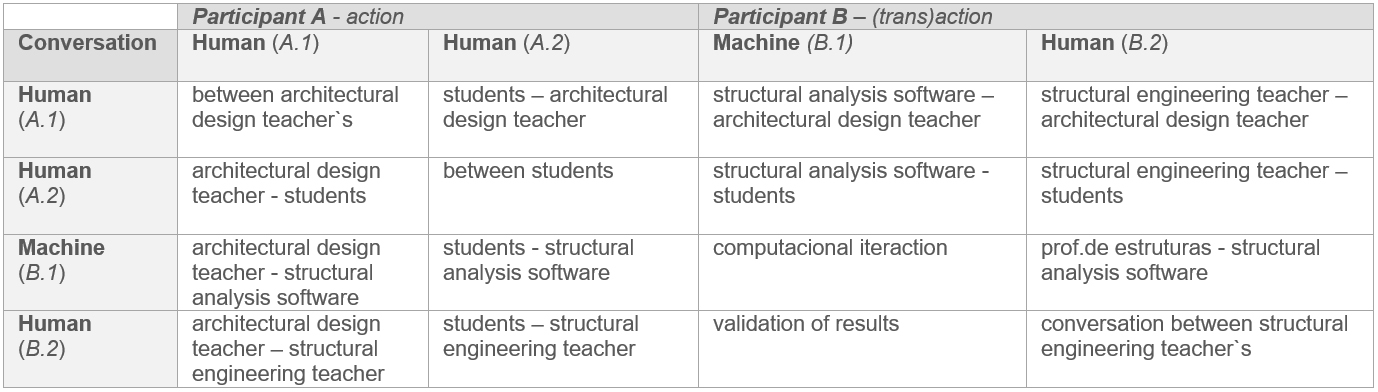

Na primeira hipótese, que chamaremos de Modelo Conversacional do Tipo 1 (com enfoque na conversa homem-máquina), a proposta é desenvolver um modelo de ensino em que os alunos utilizem softwares de análise estrutural para o desenvolvimento de projetos baseados em performance (utilizando conceitos de otimização, geração ou form-finding computacional) nas disciplinas de projeto existente. Este modelo, conforme elucidado no Quadro 1, consiste em envolver o Participante B na conversa (software de análise estrutural) por meio da interação homem-máquina. Este modelo conversacional produz a seguintes interações:

Neste modelo, o Participante A é o professor de projetos (A.1) e os alunos (A.2), e o Participante B, é o software de análise estrutural (B.1). O professor de projeto estabelece o diálogo com o software em dois momentos: no primeiro, na seleção e verificação da possibilidade de feedbacks de acordo com o objetivo; e, no segundo, orientando os alunos a interagirem com o software no processo desenvolvido. A conversação ocorre entre professores de projetos, alunos e software de análise estrutural. O objetivo da conversa homem-máquina é ampliar as possibilidades de conversação.

A interação com os computadores serve para cooperar nas tomadas de decisões em situações complexas. Nos ambientes avançados de projeto, o que para Oxman (2008) seria o projeto baseado em performance, utilizando interação e iteração homem-máquina e entre múltiplos agentes, é possível criar um processo de conversação com múltiplos feedbacks e recursividade. Este processo teria o potencial de transformar as relações entre arquitetos e engenheiros, em que através de uma linguagem comum propiciada pelo meio digital, os valores seriam explicitados e ambos compartilhariam do mesmo objetivo.

Oxman (2012) define performance como a habilidade de agir diretamente nas propriedades físicas do design, podendo ser ampliada para incluir aspectos qualitativos como fatores espaciais em simulações técnicas. Para Kolarevic (2005), o conceito de performance vai muito além de aspectos estéticos, funcionais e técnicos, podendo ser ampliada para uma dimensão financeira, cultural, espacial e social. A compreensão de performance9 como um processo, demanda uma revisão do entendimento do “corpo edificado” como um “corpo estático”, sugerindo a ideia etimológica da formação do objeto arquitetônico através do movimento.

Para além do diálogo entre projetos e estruturas, o projeto digital baseado em performance inclui o computador como parte do processo, um terceiro participante envolvido na conversação. Incorporar a tecnologia como ferramenta de interface da conversação propicia aos participantes uma linguagem compartilhada para um processo dialógico cooperativo, facilitando o desenvolvimento de um processo interativo e iterativo, circular e recursivo. Para Oxman e Oxman (2010), o processo cooperativo digital dilui as questões de autoria da forma, através de processos investigativos e experimentais, revertendo a maneira de pensar forma, força e estrutura.

Dessa maneira, baseado na conversa homem-máquina aplicada ao ensino, foi proposto o uso de softwares de análise estrutural em disciplinas de projeto. Sendo assim, temos a seguinte estrutura para o desenvolvimento do Modelo Conversacional Tipo1:

Contexto: disciplinas de projetos;

Linguagem: uso de softwares de análise estrutural simplificados para form-finding estrutural integrado a aulas teóricas de propriedades dos materiais;

Acordo: aprendizagem de software de análise estrutural para auxiliar no pré-dimensionamento da forma proposta;

Engajamento: o software propicia um pré-dimensionamento através da quantidade de material necessária;

Ação e (Trans)ação: recursividade no pré-dimensionamento e na escolha de materiais durante o desenvolvimento do projeto arquitetônico.

Neste modelo, o que se observa é que os alunos que já possuem conhecimentos intermediários e avançados (tanto de projetos quanto de estruturas) conseguem se engajar no modelo de conversação. Isto ocorre porque estes conseguem compreender os objetivos, a linguagem proposta e desta maneira utilizam a transação do software para aplicação no processo de projeto. No entanto, o que se percebe neste modelo, é que a simplificação da linguagem utilizada não permite o engajamento para a recursividade e não propicia o engajamento com outras conversas, sendo somente uma ferramenta eficiente para que os alunos explorem a materialidade do objeto.

6 Conversa homem-máquina-homem

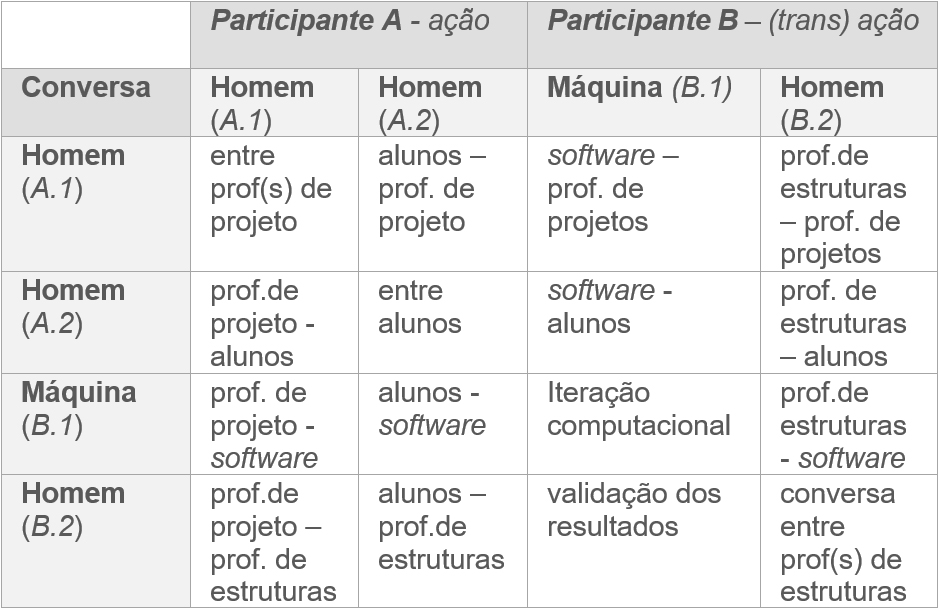

Numa segunda hipótese para a construção do modelo, devido as suas limitações identificadas no Tipo 1, as demandas de conhecimento extrapolam a conversa homem-máquina e é necessário incluir um novo Participante B, que seria um professor de estruturas. Este pode ser introduzido como um novo elemento, ampliando a conversa homem-máquina para uma conversa homem-máquina-homem, abrindo novos canais de conversas que precisam ser trabalhadas. Neste modelo, que será identicado como Modelo Conversacional Tipo 2, várias conversas podem ocorrer simultaneamente conforme demonstrado no Quadro 2, o que desta forma exigiria do professor de projetos explicitar a todos os participantes o objetivo e os valores envolvidos, havendo um acordo e um engajamento de todos afim de evitar ruídos, e por consequência, conflitos de interesses entre os participantes.

Segundo Pask (1980), uma pessoa pode simultaneamente ter a perspectiva de mais de um participante, unificando a conversação interna. Ao adotar diferentes papéis, este participante deve ponderar os méritos das diversas hipóteses que podem surgir dos outros participantes. Neste modelo, o Participante A, na figura do professor de projetos (A.1), seria o participante que exerce esta função. Caso não haja acordo e engajamento com o Participante B na figura do professor de estruturas (B.2), todo o processo pode levar a uma transação conflituosa, ou até mesmo inviabilizar que esta ocorra. Nesta proposição podem ocorrer várias conversas:

A proposta de criação do Modelo Conversacional do Tipo 2, considerando toda a complexidade envolvida e as múltiplas interações propiciadas, não é criar um modelo fechado, mas criar um sistema com subjetividades, valores e responsabilidades explícitas, possibilitando que todos os participantes possam criar. A conversação é necessária para convergir em objetivos compartilhados, e assim reordenar a situação a fim de agir conjuntamente. Dessa forma, a conversa entre homens é fundamental para a compreensão dos princípios de dualidade, complementaridade e conservação. Dessa forma, não pode haver a perda de conceitos no desenvolvimento de um ambiente único para as duas disciplinas (projeto e estruturas). Para Pask (1980), o princípio da conservação da informação a ser transferida na conversação através da linguagem e dos meios é o que mantém a coerência do sistema. Dessa maneira, a proposição de um Modelo Conversacional do Tipo 2 para a síntese de todas as conversas que ocorreriam internamente, abarca as seguintes definições:

Contexto: disciplinas híbridas projeto e estruturas;

Linguagem: aprendizagem de softwares de análise estrutural integrada a aulas teóricas de concepção estrutural10 em suas dimensões quantitativas e qualitativas;

Acordo: aprendizagem dos conceitos e aplicação no software para iteração com o modelo computacional;

Engajamento: desenvolvimento de processo iterativo em que os participantes possuem as avaliações do software como interface para o diálogo;

Ação e (Trans)ação: recursividade no desenvolvimento do projeto arquitetônico. A participação do professor de estruturas é demandada para a sofisticação da iteração. Arquitetos e engenheiros desenvolvem uma relação de cooperação em substituição a uma relação de colaboração;

Para promover um processo circular e recursivo num modelo complexo como o Tipo 2, a estrutura pedagógica das disciplinas propostas pode ser dividida em 4 momentos baseados em Pangaro (2011), sendo todos estes momentos iterativos e recursivos:

Conversation to Agree on Goals: momento em que os objetivos devem ser explicitados e acordados até serem levados ao engajamento;

Conversation to Design the Designing: momento de identificação de conhecimentos insubstituíveis para o projeto de um novo espaço de possibilidades;

Conversation to Create New Language: à medida que um novo espaço de possibilidades evolui, uma nova linguagem se molda e se define;

Conversation to Agree on Means: acordo sobre o plano de ações para o desenvolvimento de produtos utilizando o modelo conversacional proposto.

As disciplinas híbridas têm como proposta possibilitar a abertura para diálogos, não eliminando, dessa maneira, a possibilidade de se manter as disciplinas de estruturas atuais. Ao contrário, estimulam os alunos a buscar nestas ferramentas teóricas para compreenderem melhor como utilizar os recursos de análise e interação propiciados pelos softwares de análise estrutural. Os recursos visuais dos softwares permitem a visualização do comportamento das estruturas, levando a um reconhecimento dos conceitos apreendidos através de modelos matemáticos analíticos, que por serem demasiadamente abstratos, geralmente não são bem compreendidos.

O que foi notado no desenvolvimento do Modelo Conversacional Tipo 2 é que a diferença entre alunos com conhecimentos básicos de estruturas e alunos com conhecimentos intermediários e avançados não é percebida, sendo que todos se engajam no desenvolvimento do processo iterativo e demandam a participação do engenheiro de estruturas no processo. Esta conversa pode, inclusive, extrapolar as bordas da própria disciplina, possibilitando e encorajando os alunos a buscarem novos conhecimentos com outros professores de estruturas ou até mesmo com outros agentes da construção civil (projetistas, indústria e profissionais do canteiro).

Os alunos com conhecimentos avançados, tanto de projetos quanto de estruturas, se engajam no diálogo que transborda a disciplina. Estes alunos buscam o conhecimento teórico oferecido nas disciplinas tradicionais de estruturas (alguns retornam a assistir aulas de disciplinas tais como resistência dos materiais e análise estrutural), procuram o diálogo com outros professores de estruturas, buscam outros softwares, profissionais da área e até mesmo se engajam em um diálogo crítico com o setor da construção civil.

7 Conclusões

A divisão moderna do trabalho levou arquitetos e engenheiros a desenvolverem uma relação colaborativa, em que colaborar significa desenvolver um trabalho comum, através de ajuda ou auxílio. Ou seja, o arquiteto desenvolve um projeto e o engenheiro o ajuda, ou o auxilia, com seu trabalho, não atuando de maneira conjunta no seu desenvolvimento. A mudança de relação no sentido de se desenvolver um trabalho cooperativo redefine as posturas dos profissionais e reaproxima o trabalho de ambos, onde a atuação ocorre conjuntamente para um mesmo fim.

A proposta pedagógica de se desenvolver modelos conversacionais para o ensino de projetos e estruturas vai ao encontro do que coloca Montaner (2017) sobre uma prática rumo a uma arquitetura de ação. Para Dubberly e Pangaro (2015a), a conversação para a ação promove entre os participantes uma relação ética (acordo com os objetivos), cooperativa (acordo com os meios), inovadora (criação de uma nova linguagem) e responsável (criação de um novo processo).

De acordo com Dubberly e Pangaro (2015a), o conhecimento do vocabulário e da gramática não é um pré-requisito, mas propicia um terreno mais fértil para o surgimento da poesia, e, do deleite. Ao projetar ambientes interativos como extensões computacionais da agência humana ou novos discursos sociais para governar a mudança social, o projeto de segunda ordem facilita a emergência de condições em que outros podem projetar, criando condições nas quais as conversas possam emergir, aumentando assim o número de opções abertas a todos.

Para que o ensino de estruturas faça parte de uma conversação dentro das disciplinas de projeto, é necessário que o ensino de projetos também seja aberto à substituição de um modelo tipológico, com um acerto da forma linear, para um modelo de performance topológico, em que o arquiteto não tenha o controle do objeto projetado, mas sim do processo, permitindo que a arquitetura surja da participação e da emergência entre uma série de agentes. As ferramentas digitais de análise estrutural propiciam um jogo de iteratividade entre os parâmetros utilizados para conceber o espaço e suas possibilidades de materialização através de processos de otimização, geração, ou de um form-finding estrutural. Neste caso, o computador atua como um instrumento cibernético que responde aos parâmetros estabelecidos pelos estudantes para a concepção do sistema estrutural, instruindo-o e sendo instruído por ele, em um processo recursivo que pode agregar quantos agentes forem necessários. Neste processo, podem emergir resultados inesperados, não previstos inicialmente, criando novidade para ambos os participantes.

A criação de processos colaborativos de projeto em que se constrói coletivamente o conhecimento através de participação de outros agentes, leva a uma mudança de paradigma. As conversas estabelecidas podem transformar indivíduos e organizações mudando valores e modos de arranjo, sendo que a conversa iniciada no ensino pode ser replicada na prática profissional. Para Pangaro (2017), quando uma conversação se inicia, ela nunca termina. Desta maneira, acreditamos que a conversação iniciada no ambiente de ensino tem a capacidade de transformar a prática profissional, modificando, desta forma, as relações entre os agentes da construção civil (arquitetos, engenheiros, trabalhadores e usuários) e suas formas de participação através da emergência de práticas dialógicas, em que se norteia a discussão sobre o objeto que as conecta, ou pode conectar.

Referências

DUBBERLY, H.; PANGARO, P. What is Conversation? How can we design for effective conversation? Interactions Magazine, v. 16, p. 22, jul-ago. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.dubberly.com/articles/what-is-conversation.html>.. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

DUBBERLY, H.; PANGARO, P. Cybernetics and Design: Conversations for Action. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, v. 22, n. 2-3, p. 73-82, 2015a. Disponível em <http://www.dubberly.com/articles/cybernetics-and-design.html>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

DUBBERLY, H.; PANGARO, P. How cybernetics connects computing, counterculture, and design. In: BLAUVELT, A.; CASTILLO, G.; CHOI, E. (Ed.) Hippie modernism: The struggle for utopia.Minneapolis, 2015b. p. 126-141. Disponível em: <http://www.dubberly.com/articles/cybernetics-and-counterculture.html>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

FRAMPTON, K. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture.Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995.

KOLAREVIC, B. Performative Architecture Beyond Instrumentality. New York: Spon, 2005.

MONTANER, J. M. A condição contemporânea da arquitetura. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili, 2016.

MONTANER, J. M. Do diagrama às experiências, rumo à uma arquitetura de ação. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili, 2017.

OXMAN, R. Performance-based design:current practices and research issues. International Journal of Architectural Computing, v. 6, n. 1, p. 1-17, 2008.

OXMAN, R.; OXMAN, R. (Ed.). The New Structuralism: design, engineering, and architectural technologies. Architectural Design, Special Issue, Londres, v. 80, n. 4, Mar./Abr. 2010.

OXMAN, R. Informed Tectonics in Material based Design. Design Studies, v. 33, n. 5, p. 427-455, 2012.

PANGARO, P. How Can I Put That? Applying Cybernetics to “Conversational Media”. American Society for Cybernetics, Washington, 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.pangaro.com/published/Applying-Cybernetics-to-Conversational-Media-Pangaro.pdf>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

PANGARO, P. Design for Conversations & Conversations for Design. In: coThinkTank, Berlin, 2011. Disponível em: <http://pangaro.com/conversations-for-innovation.html>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

PANGARO, P. Questions for Conversation Theory or Conversation Theory in One Hour. Kybernetes, v. 46, n. 9, p.1578-1587, 2017. Disponível em: <http://www.pangaro.com/published/Pangaro%E2%80%93Questions-for-Conversation_Theory_In_One_Hour-Kybernetes_2017.pdf>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

PASK, G. Conversation Theory: applications in education and epistemology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1976a.

PASK, G. Conversational techniques in the study and practice of education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, v. 46, n.1, 1976, p. 12-25, 1976b.

PASK, G. Developments in Conversation Theory:actual and potential applications. In: INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON APPLIED SYSTEMS RESEARCH AND CYBERNETICS, Dez. 1980, Acapulco-México. Anais… Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus16/?sec=11&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2018.

SANTOS, R; KAPP, S. Articulação como Resistência.In: ENANPARQ - ENCONTRO DA ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO, 3., 2014, São Paulo. Anais… São Paulo / Campinas: Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie/ PUC Campinas, 2014.

ZUMTHOR, P. Performance, recepção, leitura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2007.

1 Para Framptom (1995) o significado de tectônica variou muito ao longo do séc. XX devido às mudanças culturais e ecológicas, e ao desenvolvimento industrial e pós-industrial, além do surgimento de uma sociedade majoritariamente urbana, o que transformou o valor da tectônica. Na etimologia grega, o termo tectônico deriva da palavra tekton que significa carpinteiro ou construtor. O termo se referia a um artesão que trabalhava com materiais pesados, como pedra e madeira, exceto o metal. O termo tekton também tinha uma conotação poética, em que o artesão explora o potencial de expressão da técnica construtiva. Sendo assim, para Framptom (1995), a tectônica refere se à poética da construção, em que a arte e o ofício estão intricadamente conectados.

2 Seker introduz o conceito de atectônica como “uma maneira pela qual a interação expressiva de carga e suporte na arquitetura é visualmente negligenciada ou obscura” (apud FRAMPTON, 1995, p.19)

3 Participar: palavra composta pelas noções de parte, ser parte de, e agarrar, tomar, indicando uma ação voluntária e decidida.

4 Colaborar: o verbo une o sentido do latim laborare - trabalhar, sentir dor, cansar-se - à condição coletiva dada pelo prefixo co - juntos.

5 A cibernética é uma forma de enquadrar o processo de design e os produtos do design, sendo ambos meios e fins. A estrutura cibernética envolve objetivos, recursividade e aprendizagem (DUBBERLY; PANGARO, 2015a).

6 A cibernética de primeira-ordem traz uma compreensão de causalidade circular para a compreensão de sistemas interativos que envolvem recursão, aprendizagem e co-evolução. Já a cibernética de segunda-ordem enquadra o design como uma conversação, e desta forma, requer tornar os valores e os pontos-de-vista explícitos, incorporando assim subjetividade e epistemologia, criando condições para que os participantes aprendam juntos (DUBBERLY; PANGARO, 2015a).

7 Para a realização desta análise foram utilizados os planos de ensino das disciplinas do Curso de Arquitetura e Urbanismo Diurno da UFMG versão curricular 2014/1 e do Curso de Engenharia Civil da UFMG versão curricular 1998/1.

8 III Encontro Nacional de Ensino de Estruturas em Escolas de Arquitetura, realizado em 2017, que buscou retomar a discussão iniciada em 1974 e 1985, respectivas datas do primeiro e do segundo evento. A proposta do III ENEEEA foi atualizar a discussão e ampliá-la, debatendo as possibilidades de articulação dos conteúdos do ensino de estruturas com o ensino de projetos.

9 Para a ampliação do conceito de performance no sentido de se desenvolver uma teoria para arquitetura digital, essa não pode ser reduzida a aspectos quantitativos. Alguns apontamentos de Zumthor (2007) nos levam a uma reflexão das possibilidades de apropriação do termo para além de uma análise quantitativa de aspectos técnicos, mas para uma assimilação que também abarque o processo de projeto enquanto um fenômeno.

10 Concepção estrutural envolve conceber a geometria, estabelecer os carregamentos e as condições de contorno da estrutura, conhecer as propriedades dos materiais e selecionar as seções transversais dos elementos da estrutura.

Conversation between architects and engineers in architectural design teaching

Marina Ferreira Borges is an Architect and Civil Engineer, Master in Structural Engineering. She is a researcher at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, and studies project teaching, structural design, and the possibilities of using emerging digital tools.

How to quote this text: Borges, M. F., 2019. Conversation between architects and engineers in architectural design teaching. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 18. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=4&item=9&lang=en>. [Accessed: 15 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 28, 2018

Abstract

The structural education in architecture schools emphasize that the dialogue between professionals should be the connecting point between the conception of the structural morphology, to be carried out by the architect, and its validation and construction by the structural engineer. However, is this dialogue actually happening? The aim of this work is to study the conversational model proposed by Paul Pangaro (2009), based on Gordon Pask's Conversation Theory (1976a), and investigate if a dialogic process between architectural design and structural education in architectural schools in fact occurs, or if it is possible to propose a new conversational model, promoting transdisciplinary participation and collaboration practices.

Keywords: Architectural design teaching, Structural education, Conversation Theory, Cybernetics

1 Introduction

Structural education is a key element for stimulating architecture students to think about the relations between form, materiality and tectonics, since it assists in the reasoning of physical design processes, leading to a point of convergence between the disciplines of architectural design and structural engineering, whose lack of organicity only accentuates the fragmentation between design and construction. Structural education in architecture should not be an end in itself as in civil engineering courses that form professionals who develop structural calculations but a means for students to think about the tectonics1 of the form. The fragmentation between the disciplines of architectural design and structural engineering corroborates to an atectonic2 design thinking, favoring the simplistic application of technique and the generation of fashion images (Frampton, 1995). .

For decades, structural education in architecture schools has trained architects to the same routine of structural engineers, in which there is no critical, reflexive and dialogical knowledge (Santos and Kapp, 2014). With disciplines focused mainly on quantitative aspects, they are too abstract and do not offer architectural students adequate tools to take ownership of the relationship between material behavior and structural systems design. Thus, they fail to develop a structural logic from an analytical understanding of the various possible solutions to a design problem.

However, the education plans of structural disciplines offered in the architectural schools emphasize that the dialogue between professionals should be the connecting point between the conception of the structural form (to be carried out by the architect) and its validation and construction by the structural engineer. But in teaching practice, is this desirable dialogue between architectural design disciplines and structural education effectively taking place?

To analyze this, we propose a methodology that employs the conversational model of Pangaro (2009) based on the concepts developed by Gordon Pask's Theory of Conversation (1976a). Thus, an adapted conversational model will be used to analyze the relationship between architectural design teaching and structural education in order to identify the existing problems in the current model. With this, it will be possible to propose a conversational model among these disciplines that allows an effective dialogic practice of design, enabling architecture students to elaborate new project systems that encourage the construction of a collective practice of knowledge through participatory3 and collaborative4 processes, in which architecture becomes an understanding, rather than an autonomous discipline (Montaner, 2017).

2 Conversation Theory

The Conversational Theory was developed by Gordon Pask (1976a) and originated from a cybernetic assembly5, in which the fundamental idea is that learning occurs through conversations about the subject matter of the discipline, making knowledge explicit. Pask defines conversation as "an intersection between two second order systems in which humans, machines and environments may be engaged in a collaborative exchange of information". When applied to the design process, second-order6, cybernetics redefines it as a conversation in which participants must learn together. According to Pask (1980), the Theory of Conversation is used to illustrate an argument in favor of reflexive and relativistic theories in cybernetics and systems studies. Language is fundamental, in which, through a means of processing, has as its property the ability to question, command, respond, obey and explain a certain goal.

Dubberly and Pangaro (2009) use Gordon Pask's cybernetic models of conversation theory because they are based on an in-depth study of the interactions between human-human and human-machine, believing that only through conversation it is only possible to learn new concepts, share and evolve knowledge, and confirm agreement. In conversation the output of one learning system becomes the input to another.

In conversation systems, based on cybernetic theory, humans, machines and environments can be engaged in collaborative information exchange. For Dubberly and Pangaro (2009), the conversation process occurs when its participants perform the following tasks:

1. Open a channel by sending an initial message of common interest;

2. Commit to engage with a symmetrical relationship between participants;

3. Construct meaning, in which the basis of the conversation must be the sharing of contexts, with common language and same social norms;

4. Evolve, since the conversation affects both participants, in which changes brought about by the conversations have lasting value;

5. Converge on agreement through common goals;

6. Act or transact, developing cooperative relationships;

The Conversion Theory applied to teaching practices requires the developed methodology to have a cyclicality that allows the student to reconstruct a concept and a consistency, allowing all the approached topics to be identified separately (Pask, 1976b), creating new conversation processes. In the autonomous conversation model by Pangaro (2009), as shown in Figure 1, the Participant A is the one who initiates the process of collaboration through conversation, defining the initial goals according to their point of view, articulating the logic of conducting the conversation considering that new goals or new opportunities can emerge during the process. Participant A has access to a learning structure but is unaware of some topics. Participant B should have the answers to the questions of Participant A providing appropriated demonstrations (Pask, 1976b). The conversation begins only if one of the participants have a goal, specific or general, articulated or without form.

Fig. 1: Simplified view of Pask’s view of conversation. Source: Pangaro, 2017. Available at:http://www.pangaro.com/published/Pangaro%E2%80%93Questions-for-Conversation_Theory_In_One_Hour-Kybernetes_2017.pdf>. [Accessed 30 June 2018].

Thus, Pangaro (2009) systematizes what would be a conversational model and establishes some requirements for its organization:

Context: moment, situation, place and/or shared history;

Language: initial shared means for conveying meaning;

Agreement: shared understanding of concepts, intent, values that may lead to an action;

Exchange: availability for interaction, result of a shared language and a context conducive to interaction that can build an agreement;

Action and (Trans) action: cooperative conversation, circular and recursive.

3 Analysis of current teaching practice

In structure disciplines currently offered in architectural courses7, what exists is a technical communication. For Pask (apud Pangaro, 2017), the difference between communication and conversation is that for the dialogue to occur something must be transformed for one or more participants, be it the understanding of the subject, concepts, intentions or values. If this transformation does not occur, what happened was a mere exchange of messages.

The current model of structural education is fragmented into disciplines that follow a similar civil engineering education, having disciplines of theoretical foundation (introduction to structural systems), intermediate knowledge (structural analysis and materials’ resistance) and specific advanced knowledge (concrete, steel and wood). All disciplines have as bias the structural analysis by the analytical method that is using mathematical equations. Experimental methods, focused on the development of physical models, and computational methods that allow a better visualization of the physical behavior of the models are not used. In this way, students are only instrumented with an abstract mathematical language that is difficult to apply to architectural design. In this way, is the mathematical and abstract language used for teaching structures in architectural schools enough for the establishment of a conversational practice?

In architectural teaching, design disciplines wish to learn about structures for definitions of spatiality, morphology, and construction materiality. The role of teaching structures is a cooperative action with the dialogue to be established. Thus, in this dialogue, architectural design teaching is Participant A (which initiates the conversation with an action) and structural education is Participant B (which reacts to this action with a transaction).

The objective of this dialogue should be to provide the architect with structural knowledge that allows flexibility in structural parameters in harmony with spatial articulation. The structure in a tectonic design conception is not an autonomous object that must suit the space or vice versa. The architectural design teaching is (or should be) the driver of the conversation between agents, promoting the opening of common channels of conversation. In the current teaching model there is no formalized environment for the conversation with teaching of structures to take place.

In this way, we will first analyze the current teaching practice through the bias of the conversational model, verifying if there is a conversation between architectural design teaching and structural education within the context of each discipline:

Participant A: Architectural Design Teaching

Context: architectural design disciplines;

Language: manual or digital representation methods of architectural design;

Agreement: launch of the structure according to pre-dimensioning criteria;

Exchange: when it occurs, it happens through the analysis of examples and counter-examples of structural solutions of analogous works. It may also occur consulting the specific bibliography of structural knowledge directed to the learning of architects;

Action and (Trans) action: practically does not occur. It depends on the individual willingness of design teachers and students to seek some contact with the teachers of structures disciplines.

Participant B: Structural Education

Context: disciplines of structures;

Language: mathematics through analytical method;

Agreement: according to the subjects of the disciplines, only the basic concepts of the contents are offered in such a way that the architects can carry out a structural pre-dimensioning and dialogue with structural engineers in professional practice;

Exchange: the inadequacy of the application of language to design development does not allow the exchange;

Action and (Trans) action: practically nonexistent since the exchanges are made difficult by the language used;

In the current model, there is no possibility of feedback, and a process of linear causality is created. According to Dubberly and Pangaro (2015a), this linear process does not allow the iteration, which would be the correction of the error, and the convergence of objectives among the participating agents, limiting design to simplified feedbacks. In this way, for the proposition of a conversational model between the architectural design teaching and structural education, it is important that there is a context that allows the possibility of multiple feedbacks, promoting circularity and recursion. For this, it is fundamental that Participant B interacts in the context of Participant A, developing a common language, with explicit goals, in a context that facilitates the exchanges, in which these will serve as the basis for a joint action and for the creation of new values.

4 Proposal of a Conversational Model

Cybernetics studies how systems organize themselves, dealing with how they communicate internally and with other systems, which stimulates collaborative transdisciplinary thinking. For Von Foerster (apud Dubberly and Pangaro, 2015b, p.5, our translation), "one can and should try to communicate beyond the boundaries, and often the abysses, that separate the various sciences".

Some attempts to promote this integration have been developed to improve the dialogue between architectural design teaching and structural education. As can be seen in III Eneeea8, some Brazilian universities focus on a language modification (experimental methods with the use of physical models or investigations in experimental building sites), others involve new participants (engineering professors present in the design disciplines) and some even propose a new conversational model.

However, these propositions are focused on technical communication and do not present meaningful reflections regarding changes in architecture itself and its contemporary condition. For Montaner (2016), contemporary architecture has a contextualist and complex synthesis character, in which a new pragmatism is reformulated through practical tools of knowledge, analysis and design. According to him, the diagrammatic practices and the digital tools facilitate the development of an architectural theory related to an interactive pragmatism. Pangaro (2011) believes that design development should be more concerned with the design process than with the shape of objects, and that without the creation of a new language, innovation is limited to improvements in existing processes. But how do we develop a new language?

The proposal of a new conversational model between the architectural design teaching and structural education seeks to promote a common language among the participants, so that it is possible for the exchanges to be effectively carried out. For this, it is fundamental that Participant B promotes its (trans) action within the same environment of design teaching (Participant A). Participant B can be a machine (use of structural analysis software) or a human (teacher of structures disciplines). In this way, the proposed conversations are about promoting human-machine interaction or human-machine-human interaction.

5 Human-machine conversation

In the first hypothesis, which we will call the Conversational Model Type 1 (focusing on human-machine conversation), the proposal is to develop a teaching model in which students use structural analysis software to develop performance-based design methodologies (with focus on optimization, generation or computational form-finding) in the existing design disciplines. This model, as elucidated in Table 1, consists of involving Participant B in the conversation (structural analysis software) through human-machine interaction. This conversational model produces the following interactions:

In this model, Participant A are the architectural design teacher (A.1) and students (A.2), and Participant B is the structural analysis software (B.1). The design teacher establishes the dialogue with the software in two moments: first, in the selection and verification of the possibility of feedbacks according to the objective; and second, directing the students to interact with the software in the developed process. The conversation takes place between design teachers, students, and structural analysis software. The purpose of the human-machine dialogue is to broaden the possibilities for conversation.

Interacting with computers serves to assist in making decisions in complex situations. In advanced design environments, which for Oxman (2008) is considered to be performance-based design, through the use of interaction and iteration between human-machine and multiple agents it is possible to create a conversation process with multiple feedbacks and recursion. This process could have the potential to transform the relationships between architects and engineers through a common language provided by the digital medium in which values would be explicit and both would share the same goal.

Oxman (2012) defines performance as the ability to act directly on the physical properties of design and it can be extended to include qualitative aspects such as spatial factors in technical simulations. For Kolarevic (2005), the concept of performance goes far beyond aesthetic, functional and technical aspects, and can be extended to a financial, cultural, spatial and social dimension. The understanding of performance9 as a process demands a revision of the understanding of the "built body" as a "static body", suggesting the etymological idea of the formation of the architectural object through movement.

In addition to the dialogue between architectural design and structures, the performance-based digital design includes the computer as part of the process, a third participant involved in the conversation. Incorporating technology as a conversation interface tool provides participants with a shared language for a cooperative dialogic process, facilitating the development of an interactive, iterative, circular, and recursive process. For Oxman and Oxman (2010), the digital cooperative process dilutes the matter of authorship of form, through investigative and experimental processes, reversing the way of thinking form, force and structure.

In this way, based on the human-machine conversation applied to teaching, the use of structural analysis software was proposed in design disciplines. Thus, we have the following structure for the development of the Conversational Model Type1:

Context: architectural design disciplines;

Language: use of simplified structural analysis software for structural form-finding integrated to theoretical classes of material properties;

Agreement: learning of structural analysis software to aid in the preliminary structural sizing of the proposed structural typology;

Exchange:the software provides the preliminary structural sizing through the amount of material required;

Action and (Trans) action: recursion in the preliminary sizing and in the choice of materials during the development of the architectural design;

In this model, what is observed is that students who already have intermediate and advanced knowledge (of both design and structures) can engage in the conversation model. This is because they can understand the objectives, the proposed language and in this way use the software transaction for application in the design process. However, what is perceived in this model is that the simplification of the used language does not allow the engagement for recursion and the engagement with other conversations, being only an efficient tool for the students to explore the materiality of the object.

6 Human-machine-human conversation

In a second hypothesis for the construction of the model, due to its limitations identified in Type 1, the demands of knowledge go beyond the human-machine conversation and it is necessary to include a new Participant B, who would be a structural engineering teacher. This can be introduced as a new element, extending the human-machine conversation to a human-machine-human conversation, opening new channels of conversations that need to be worked on. In this model, which will be identified as Conversational Model Type 2, several conversations can occur simultaneously as shown in Table 2, which would require the design teacher to explain to all participants the goals and values involved, with an agreement and an engagement of all in order to avoid disturbance, and consequently, conflicts of interest between the participants.

According to Pask (1980), a person can have the perspective of more than one participant simultaneously, unifying the internal conversation. When adopting different roles, this participant should consider the merits of the various hypotheses that may arise from the other participants. In this model, the Participant A in the figure of the design teacher (A.1) would be the participant that performs this function. If there is no agreement and engagement with Participant B in the figure of the structural engineering teacher (B.2), the entire process may lead to a conflicting transaction, or even make it infeasible. In this proposition, several conversations may occur:

The proposal to create the Conversational Model Type 2, considering all the complexity involved and the multiple interactions provided, is not to create a closed model but to create a system with explicit subjectivities, values and responsibilities allowing all participants to create. Conversation is necessary to converge on shared goals and therefore rearrange the situation in order to act together. In this way, the conversation between people is fundamental for understanding the principles of duality, complementarity and conservation. Like so, there can be no loss of concepts in the development of a unique environment for the two disciplines (design and structures). For Pask (1980), the principle of preserving the information to be transferred in the conversation through language and through other means is what maintains the coherence of the system. In this way, the proposition of a Conversational Model Type 2 for the synthesis of all conversations that would occur internally, encompasses the following definitions:

Context: hybrid disciplines of architectural and structural design;

Language: learning of structural analysis software integrated to theoretical modules of structural design10 in its quantitative and qualitative dimensions;

Agreement: learning of concepts and application in the software for iteration with the computational model;

Exchange:development of an iterative process in which the participants take the software evaluations as an interface for the dialogue;

Action and (Trans) action: recursion in the development of architectural design. The participation of the structural engineering teacher is required for the sophistication of the iteration. Architects and engineers develop a collaborative relationship;

In order to promote a circular and recursive process in a complex model like Type 2, the pedagogical structure of the proposed disciplines can be divided into four moments based on Pangaro (2011), being all iterative and recursive:

Conversation to Agree on Goals: moment that the objectives must be explained and agreed upon until they are brought to engagement;

Conversation to Design the Designing: moment of identification of irreplaceable knowledge for the design of a new space of possibilities;

Conversation to Create New Language: as a new space of possibilities evolves, a new language is shaped and defined;

Conversation to Agree on Means: agreement on the action plan for the development of products using the proposed conversational model.

Hybrid disciplines have the purpose to open dialogues without eliminating the possibility of maintaining the current disciplines of structures. On the contrary, to stimulate students to look for these theoretical tools to better understand how to use the resources of analysis and iteration provided by structural analysis software. The software’s visual resources allow the visualization of the behavior of the structures, leading to recognition of the concepts learned through analytical mathematical models which, because they are too abstract, are generally not well understood.

What was noticed in the development of Conversational Model Type 2 is that the difference between students with basic knowledge of structures and students with intermediate and advanced knowledge is not perceived, being that all of them engage in the development of the iterative process and require the participation of a structural engineering teacher in the process. This conversation can even extrapolate the edges of the discipline itself, enabling and encouraging students to seek new knowledge with other structural engineering teachers or even with other agents of construction industry (designers, industries and construction workers).

Students with advanced knowledge of both design and structures engage in a dialogue that overflows the discipline. These students seek the theoretical knowledge offered in the traditional disciplines of structures (some return to attend classes in disciplines such as materials’ resistance and structural analysis), seek dialogue with other structural engineer teachers, seek other structural analysis softwares, other professionals in the field and even engage in a critical dialogue with the construction industry.

7 Conclusion

The modern division of labor has led architects and engineers to develop a collaborative relationship through help or support. That is, the architect develops a project and the engineer helps or assists them with their work, not acting jointly in its development. The change of relationship in the sense of developing a cooperative work redefines the positions of professionals and re-approximate the work of both, where the action takes place jointly for the same purpose.

The pedagogical proposal to develop conversational models for teaching design and structures goes through what Montaner (2017) proposes for a practice towards an architecture of action. For Dubberly and Pangaro (2015a), the conversation for action promotes an ethical (in agreement with goals), cooperative (in agreement with means), innovative (creating a new language) and responsible (creating a new process) relation.

According to Dubberly and Pangaro (2015a), knowledge of vocabulary and grammar is not a prerequisite but provides a more fertile ground for the emergence of poetry, and of delight. By designing interactive environments as computational extensions of human agency or new social discourses to govern social change, second-order design facilitates the emergence of conditions in which others can design, creating conditions in which conversations can emerge, thereby increasing the number of options open to all.

In order for structural education to be part of a conversation within the design disciplines it is necessary that the architectural design teaching be also open to the substitution of a typological model (with an adjustment of the linear form) for a topological performance model, in which the architect does not have control of the designed object but rather of the process, allowing architecture to emerge from participation and emergence between a variety of agents. The digital tools of structural analysis provide a set of iterativity between the parameters used to conceive the space and its possibilities of materialization through processes of optimization, generation or structural form-finding. In this case, the computer acts as a cybernetic instrument that responds to the parameters established by the students for the design of the structural system instructing and being instructed by it, in a recursive process that can add as many agents as necessary. In this process unexpected results can emerge, not foreseen initially, creating novelty for both participants.

The creation of collaborative design processes in which knowledge is built collectively through the participation of other agents leads to a paradigm shift. Established conversations can transform individuals and organizations by changing values and modes of arrangement, and conversation initiated in teaching can be replicated in professional practice. For Pangaro (2017), when a conversation begins, it never ends. In this way, we believe that the conversation initiated in the teaching environment has the capacity to transform professional practice, thus modifying the relationships between civil construction agents (architects, engineers, workers and users) and their forms of participation through the emergence of dialogical practices, in which the discussion is oriented by the object that connects or might connect them.

References

Dubberly, H. and Pangaro, P., 2009. What is Conversation? How can we design for effective conversation? Interactions Magazine, 16, p.22. Available at:

Dubberly, H. and Pangaro, P., 2015a. Cybernetics and Design: Conversations for Action. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 22(2-3), pp.73-82. Available at:

Dubberly, H. and Pangaro, P., 2015b. How cybernetics connects computing, counterculture, and design. In: A. Blauvelt, A., G. Castillo and E. Choi, ed., 2015. Hippie modernism: The struggle for utopia. Minneapolis, pp.126-141. Available at:

Frampton, K., 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kolarevic, B., 2005. Performative Architecture Beyond Instrumentality. New York: Spon.

Montaner, J. M., 2016. A condição contemporânea da arquitetura. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili.

Montaner, J. M., 2017. Do diagrama às experiências, rumo à uma arquitetura de ação. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili.

Oxman, R., 2008. Performance-based design: current practices and research issues. International Journal of Architectural Computing, 6(1), pp.1-17.

Oxman, R., 2012. Informed Tectonics in Material based Design. Design Studies, 33(5), pp.427-455.

Oxman, R. and Oxman, R., ed., 2010. The New Structuralism: design, engineering, and architectural technologies. Architectural Design, Special Issue, London, 80(4).

Pangaro, P., 2009. How Can I Put That? Applying Cybernetics to “Conversational Media”. In: American Society for Cybernetics Annual Conference, Washington, 2009. Available at:

Pangaro, P., 2011. Design for Conversations & Conversations for Design. In: coThinkTank, Berlin. Available at:

Pangaro, P., 2017. Questions for Conversation Theory or Conversation Theory in One Hour. Kybernetes, 46(9), pp.1578-1587. Available at:

Pask, G., 1976a. Conversation Theory: applications in education and epistemology. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Pask, G., 1976b. Conversational techniques in the study and practice of education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(1), pp.12-25.

Pask, G., 1980. Developments in Conversation Theory: actual and potential applications. In: International Congress on Applied Systems Research and Cybernetics, Acapulco-México, 1980. Available at:

Santos, R. and Kapp, S., 2014. Articulação como Resistência. In: III ENANPARQ - Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. São Paulo, 2014. São Paulo / Campinas: Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie / PUC Campinas.

Zumthor, P., 2007. Performance, recepção, leitura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

1 To Framptom (1995) the meaning of tectonics varied greatly throughout the century. Due to cultural and ecological changes, and industrial and post-industrial development, as well as the emergence of a largely urban society, which has transformed the value of tectonics. In Greek etymology, the term tectonic derives from the word tekton meaning carpenter or builder. The term referred to a craftsman who worked with heavy materials, such as stone and wood, except metal. The term tekton also had a poetic connotation, in which the artisan explores the expression potential of the constructive technique. Thus, for Framptom (1995), tectonics refers to the poetics of construction, in which art and craft are intricately connected.

2 Seker used the concept of atectonic as “a manner in which the expressive interaction of load and support in architecture is visually neglected or obscured” (apud Frampton, 1995, p.19, our translation)

3 Participate: word composed by the notions of part, be part of, and grasp, take, indicating a voluntary and determined action.

4 Collaborate: the verb joins meaning in Latin (laborare) - work, feel pain, fatigue - to the collective condition given by the prefix co-set, with.

5 Cybernetics is a way to focus the design process and new design products, both being means and ends. The cybernetic structure involves objectives, recursivity and learning" (Dubberly and Pangaro, 2015a).

6 First-order cybernetics brings an understanding of circular causality to the understanding of interactive systems involving recursion, learning, and coevolution. Second-order cybernetics frames design as a conversation, and thus requires making values and viewpoints explicit, incorporating subjectivity and epistemology, creating conditions for participants to learn together (Dubberly, Pangaro, 2015a).

7 For the accomplishment of this analysis the teaching plans were used the disciplines of the Architecture and Urbanism Course of UFMG curriculum version 2014/1 and of the Civil Engineering Course of UFMG 1998/1 curricular version.

8 Third edition of a Brazilian national meeting of structural teaching in architecture schools, held in 2017, which sought to resume the discussion started in 1974 and 1985, respective dates of the first event and the second event. The proposal of the III ENEEEA was to update the discussion and expand it, discussing the possibilities of articulating the contents of structural teaching and architectural design teaching.

9 For the expansion of the concept of performance in the sense of developing a theory for digital architecture, this cannot be reduced to quantitative aspects. Some notes by Zumthor (2007) lead us to a reflection of the possibilities of appropriation of the term beyond a quantitative analysis of technical aspects, but for an assimilation that also encompasses the design process as a phenomenon.

10 Structural design involves designing the geometry, establishing the loadings and boundary conditions of the structure, knowing the properties of the materials and selecting the cross-sections of the elements of the structure.