Sinergia em ação: processo de projeto colaborativo

Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi é Arquiteta e Urbanista. Pesquisa aspectos cibernéticos dos processos de projeto arquitetônicos no Nomads.usp, da Universidade de São Paulo.

Anja Pratschke é Arquiteta, Doutora em Ciência da Computação e Livre-docente em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. É Professora Associada e pesquisadora do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo, e co-coordenadora do Nomads.usp. Desenvolve e orienta pesquisas sobre processos de projeto, cibernética e organização da informação.

Como citar esse texto: DI STASI, M. G. ;PRATSCHKE, A. Sinergia em ação: processo de projeto colaborativo. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 18, 2019. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=6&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

Resumo:

O presente artigo é resultado da pesquisa de mestrado no Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo. A investigação nos levou por subteorias cibernéticas que corroboram com processo de projeto arquitetônico colaborativo. Para o entendimento das bases conceituais foi estudado o Modelo de Sistema Viável, bem como o Team Syntegrity, do ciberneticista Stafford Beer. As estratégias para gerenciamento frente aos meios cibernéticos nos mostrou outra forma de observar os processos culminando em indicadores possíveis para a colaboração na Arquitetura.

Palavras-chave: Projeto arquitetônico, Colaboração, Cibernética, Sinergia

1Introdução

Atualmente, o processo de projeto arquitetônico vem sendo revisado de forma a se discutir a importância dos fatores e agentes participantes no decurso projetual. Com o avanço de conceitos colaborativos como BIM (Building Information Modeling – Modelagem da Informação da Construção) para o processo de projeto arquitetônico, a relevância em entender meios de observação e organização do meio nos levou à Cibernética. A Cibernética surge na década de 1940 com as primeiras investigações sobre processamento de informações ligadas ao cérebro humano, desenvolvida por William Ross Ashby1 (1960) em seu livro “Design for a Brain”, configurando-se como a Cibernética de Primeira Ordem. Em 1960, com o surgimento da Teoria Geral de Sistemas de Ludwig von Bertalanffy2 (1969), a Cibernética entra na Segunda Ordem, ampliando o campo de observação dos processos, para uma extensão mais holística. Na Cibernética de Segunda Ordem houve avanços no pensamento crítico e propostas de organizações sociais, como foi o caso das estratégias traçadas por Anthony Stafford Beer3, repercutindo na investigação deste artigo.

A Cibernética foi construída de forma interdisciplinar, com desenvolvimento de teorias e conceitos provenientes de diversas áreas. A complementariedade transdisciplinar trouxe aspectos para a Cibernética que nos permite retransmitir ideais para o processo de projeto arquitetônico, com enfoques dos quais carecemos, como processamento de informações e organizações colaborativas.

Baseado nessa imposição, voltamos nossa investigação para estratégias cibernéticas tanto organizacionais como colaborativos, desenvolvidos por Stafford Beer. Beer estudou ao longo da sua vida padrões matemáticos e biológicos, inicialmente através de análises do cérebro e do sistema nervoso humano. O VSM (Viable System Model - Modelo de Sistema Viável), elaborado entre 1972 e 1985, é um sistema organizacional realizado através do Sistema Nervoso Humano.

Através da publicação de três livros a respeito do VSM, Brain of the firm (BEER, 1972, 1981), The Heart of enterprise (BEER, 1979), e Diagnosing the system for organizations (BEER, 1985), Beer construiu um pensamento sistêmico para a estruturação de coordenações sociais auto organizadas. O recurso VSM foi concebido para estruturar empresas, tanto no funcionamento como na organização, através de cinco subsistemas interligados.

No entanto, Beer denotou que a conexão entre o subsistema 3 e 4 apresentava-se como insuficiente para o avanço de todo o sistema. O subsistema 3 é responsável pelo gerenciamento do processo em execução, enquanto que o subsistema 4 é responsável pela projeção de todo sistema em um âmbito futuro.

2Sinergia no Modelo de Sistema Viável

Beer percebeu que o Modelo de Sistema Viável necessitava integrar outros aspectos para responder aos desafios crescentes de organizações complexas, pois o VSM mostrou-se limitado na construção de um grupo com consciência coletiva e com participantes colaborativos. Ele partiu de uma forma geométrica tridimensional para resolver o que ele considerou a alma do VSM:

A cibernética expressa pelo VSM está disponível para ajudar. E se, como foi argumentado, o principal problema é o bom funcionamento do homeostato Três-Quatro, então esse seria um bom ponto de partida. Precisamos metabolizar os recursos criativos e sinérgicos da empresa. A equipe de gerenciamento diretivo de uma empresa talvez seja o exemplo mais energético de um infoset com o qual a sociedade está familiarizada (BEER, 1994, p. 159, tradução nossa).

Nesse caso, Beer considerou que a relação entre os subsistemas 3 e 4 era relevante para o funcionamento de toda a empresa e decidiu que essa questão precisava ser resolvida de outra forma (RÍOS, 2011, p. 201, tradução nossa):

A necessidade de uma ferramenta para facilitar a comunicação entre o Sistema 4 e Sistema 3 em uma organização foi esclarecida pelo próprio Beer quando o VSM foi apresentado. Sua última inovação, denominada Team Syntegrity (TS) (Beer, 1994), foi devidamente desenvolvida para ajudar esses dois sistemas a se comunicarem adequadamente e, como resultado, contribuir para o bom funcionamento do homeostato Sistema 4 - Sistema 3, que, como sabemos, é fundamental para garantir a adaptação e a viabilidade da organização.

A importância de um meio de comunicação que facilitasse a interação entre o Sistema 3 e 4 se fez essencial para manter o VSM viável, refletindo assim a interconectividade entre o VSM e o Team Syntegrity. Dessa forma, em 1994 Beer propôs o Team Syntegrity para proporcionar a colaboração entre os dois sistemas. Assim, os objetivos de um meio comunicativo para tal deveria ter as seguintes premissas:

- Gerar um alto nível de participação entre os indivíduos envolvidos; - Fornecer uma estrutura e um sistema de comunicação que garantam a natureza não-hierárquica do processo [...]; - Beneficiar-se da variedade e riqueza de conhecimentos fornecidos por cada indivíduo dentro do grupo, colocando em prática as sinergias derivadas da interação entre todos os seus membros; - Criar uma consciência coletiva, se possível compartilhada entre todos os membros do grupo, em relação à questão central que está sendo considerada e analisada (RÍOS, 2011, p. 205, tradução nossa).

Com isso, Beer acreditou construir um sistema de equipe colaborativa em que houvesse uma sinergia entre todos os participantes do processo, gerando uma alta variedade devida à diversidade de pessoas e à colaboração a partir de uma consciência coletiva não hierárquica. Para a idealização dessa estrutura, Beer recorreu aos estudos do arquiteto norte americano Richard Buckminster Fuller4, quando disse que:

Então eu tropecei em um velho presente de Buckminster Fuller - um mapa do tempo inscrito de sua própria vida - e comecei a pensar mais sobre suas geodésicas [...] e eu ouvi novamente em minha própria cabeça o ditado de Bucky: todos os sistemas são poliedros. É uma percepção incrível (BEER, 1994, p. 12, tradução nossa).

Definida por Fuller como o “[...] comportamento de sistemas integrais, agregados, inteiros e imprevisíveis através dos comportamentos de qualquer um de seus componentes ou subconjuntos de seus componentes tomados separadamente do todo” (FULLER, 1975-79, p. 102.00, tradução nossa). Ou seja, as partes conjuntamente compõem um sistema podendo determinar as características do todo, entretanto, separadas, podem não exibir o mesmo comportamento.

Beer se apoia nos princípios da máquina homeostática, aplicados à interação e conexão entre as pessoas e estabelece uma estrutura de relações chamada SYNTEGRITY5:

A estrutura que buscamos deve refletir a noção de uma democracia perfeita, como foi argumentado antes. Certamente significa que nenhum indivíduo, e inicialmente nenhuma causa, deve ter ascendência sobre qualquer outro. Então, em busca de poliedros sobre os quais construir modelos de tensegrity democrática, devemos considerar apenas os poliedros regulares: figuras sem topo, sem fundo, sem lados - de fato, sem características pelas quais possam ser especialmente orientadas (BEER, 1994, p. 14, tradução nossa).

Beer propôs uma estrutura não-hierárquica e democraticamente perfeita para enfrentar os desafios (BEER, 1994, p. 12), adotando a forma da geodésica.

A palavra tensegrity usada por Beer provém da explicação de Fuller sobre as formas de tensão e compressão, além de seu comportamento. Portanto:

[...] o todo, a INTEGRIDADE, da estrutura é garantida não pelas tensões de compressão locais onde os elementos estruturais são unidos, mas pelas tensões de tração totais de todo o sistema. Daí veio o termo da junção para a Integridade e Tensão: TENSEGRIDADE (BEER, 1994, p. 13, tradução nossa).

Assim, Beer se pautou nas da integridade da tensão de um sistema como um todo, em que se observou uma unidade da organização social. Além disso, Beer também entendeu que essas forças de compressão e tensão promoviam outras questões estruturais, quando disse que:

Fuller formulou a ideia de que a natureza existe em uma ponderação equilibrada entre as forças de compressão e tensão. Obviamente, a existência de ambas as forças já era conhecida, mas sua coexistência colaborativa em todos os sistemas físicos não havia sido enfatizada (BEER, 1994, p. 12, tradução nossa).

Portanto, Beer entendeu o icosaedro, a base geométrica da geodésica, como uma forma baseada em forças equilibradas de compressão e tensão utilizando-a para a reformulação do modelo de organização, quando disse:

Eu decidi basear meus principais experimentos no icosaedro e considerar as bordas como representações dos membros do Infoset (ou seja, 30) e os vértices como representações dos tópicos ou questões-chave (ou seja, 12), com o resultado de que as arestas que se unem em cada vértice (ou seja, 5) seriam protagonistas de cada tópico (BEER, 1994, p. 14-15, tradução nossa).

A partir de então, Beer passou a considerar a forma geométrica do icosaedro para compor a sua organização social. Um icosaedro possui 12 vértices, dos quais saem 5 arestas, totalizando 30 arestas. Beer considerou os vértices como sendo tópicos de discussão e as arestas como as pessoas envolvidas, dessa forma, 30 pessoas discutiriam 12 tópicos. Beer levou em conta o icosaedro como um todo e chamou-o de Infoset, por tanto, o seu Infoset seriacomposto por um grupo de 30 indivíduos e 12 tópicos, em que cinco pessoas discutiriam diretamente um tópico.

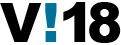

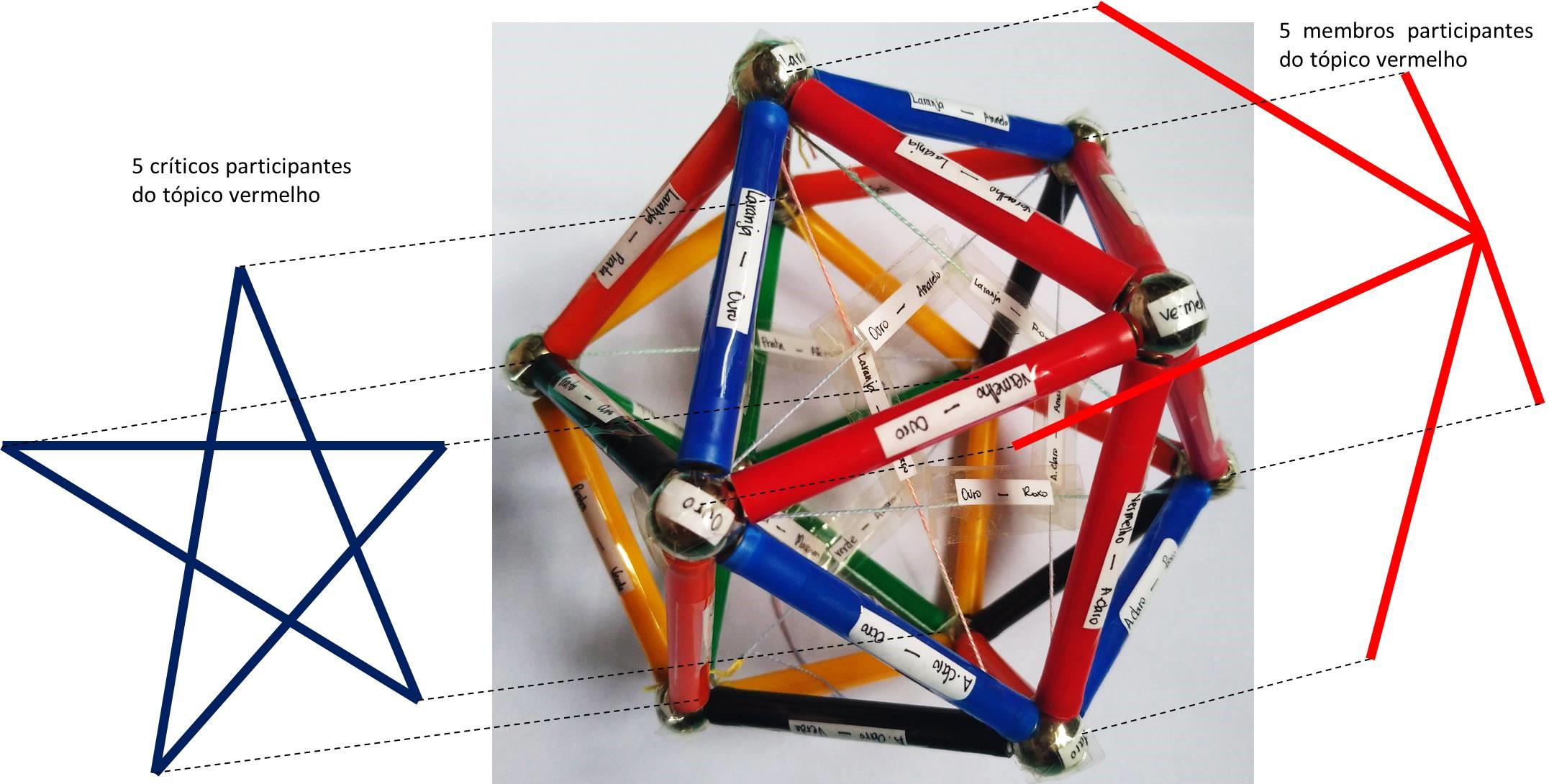

A seguir, Figura 1, encontram-se todas as ligações possíveis dentro de um Team Syntegrity, o qual é composto por ligações diretas, aquelas que são estruturadas pelos membros de equipes que discutem um tópico, e por ligações indiretas, compostas pelos críticos dos tópicos, geradas pela face oposta ao vértice discutido.

Legenda: Montagem das equipes por seleção de cores em tópicos, os membros e críticos em Syntegration Episódio 4.

Fig. 1: Rede de Interações do Team Syntegrity. Fonte: BEER, 1994, p. 138-139, tradução nossa.

Com essa rede de interações é possível construir o icosaedro e estipular as conexões diretas, indiretas e opostas, para a construção da estrutura sinérgica.

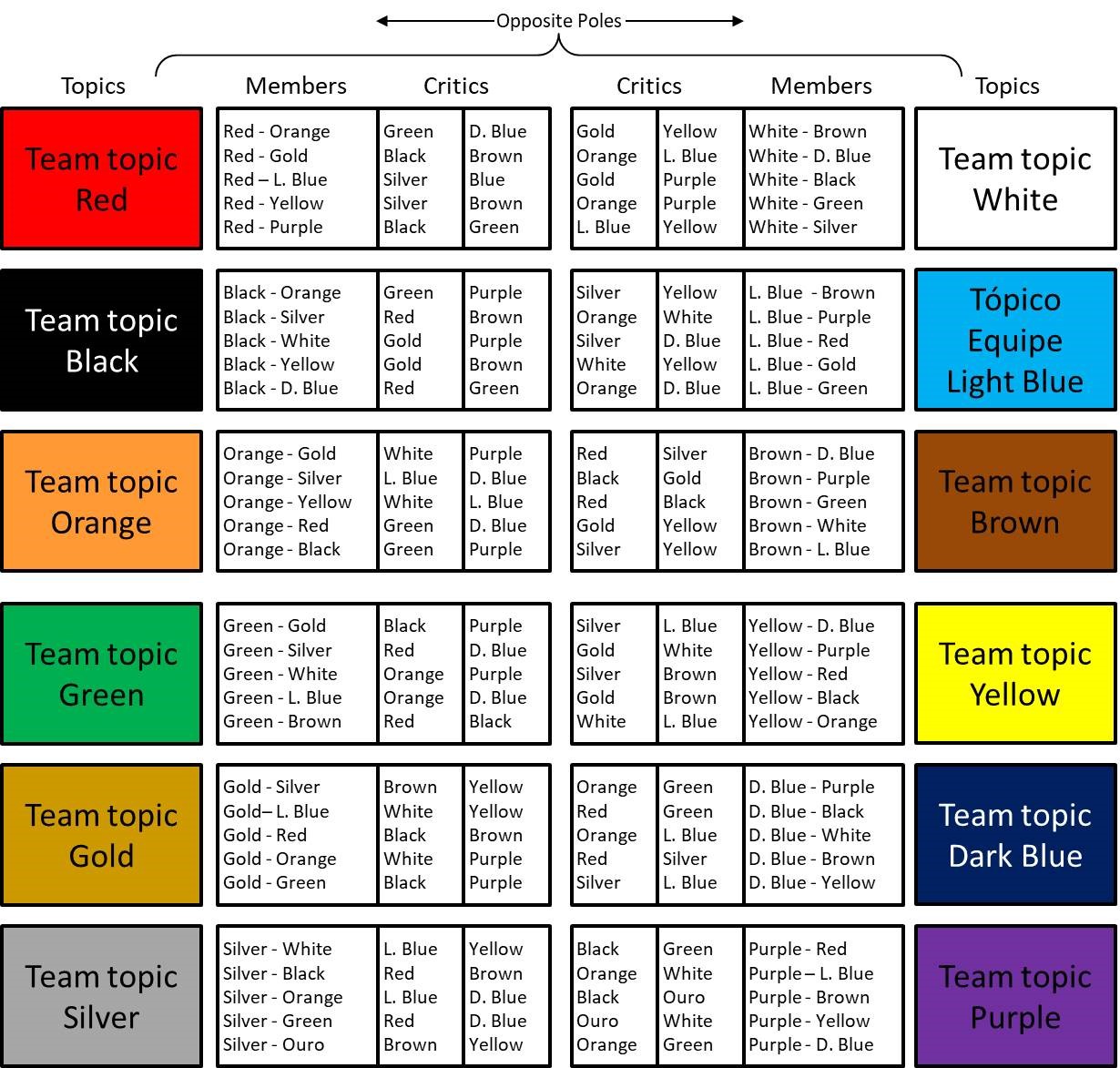

O icosaedro possui uma simetria única, em que há semelhança em qualquer posição em que ele esteja sendo dividido, ou seja, quaisquer quadrantes irão sempre possuir a mesma simetria que a outra parte. Sendo assim, podemos considerar que seus vértices possuem sempre um polo oposto e por tanto, temos 6 conjuntos de dois vértices que se contrapõem. Na imagem a seguir podemos observar um icosaedro em que, vemos e consideramos seus polos como os vértices vermelho e branco, sendo: o vértice vermelho, com suas arestas representadas por vermelho tanto no modelo como na projeção, possui os nomes das arestas com cores duplas, posto que o membro participe de dois tópicos ao mesmo tempo. Dessa forma, no tópico vermelho, temos os participantes vermelho-roxo, vermelho-amarelo, vermelho-laranja, vermelho-ouro e vermelho-azul claro. Esses cinco participantes contribuem para a discussão do tópico vermelho e dos respectivos tópicos que interligam os participantes (Figura 2), como explicado por Ríos (2011, p. 208-209).

Legenda: À direita, projeção em vermelho dos membros participantes do tópico vermelho; à esquerda, projeção azul dos críticos participantes do tópico vermelho.

Fig. 2: Icosaedro: membros e críticos. Fonte: As autoras.

Em seu polo oposto, sendo o branco na Figura 1 da tabela de Beer e desenhado em azul na Figura 2, os tópicos de discussão circundantes ao tópico branco formam uma estrela com os membros que interligam essa face do icosaedro, no modelo estes são representados por fios com os respectivos nomes e a projeção encontra-se em azul, em que os cinco participantes são preto-verde, prata-azul escuro, preto-marrom, verde-azul escuro e prata-marrom, no qual esses membros estão ligados de forma indireta ao tópico vermelho, atuando como críticos externos das contribuições e evoluções que ocorrem no tópico. O mesmo ocorre na posição oposta, a estrela circundante ao tópico vermelho atua como crítico do tópico branco e isso acontece em todas as faces, como demonstrou Ríos (2011, p. 208-209).

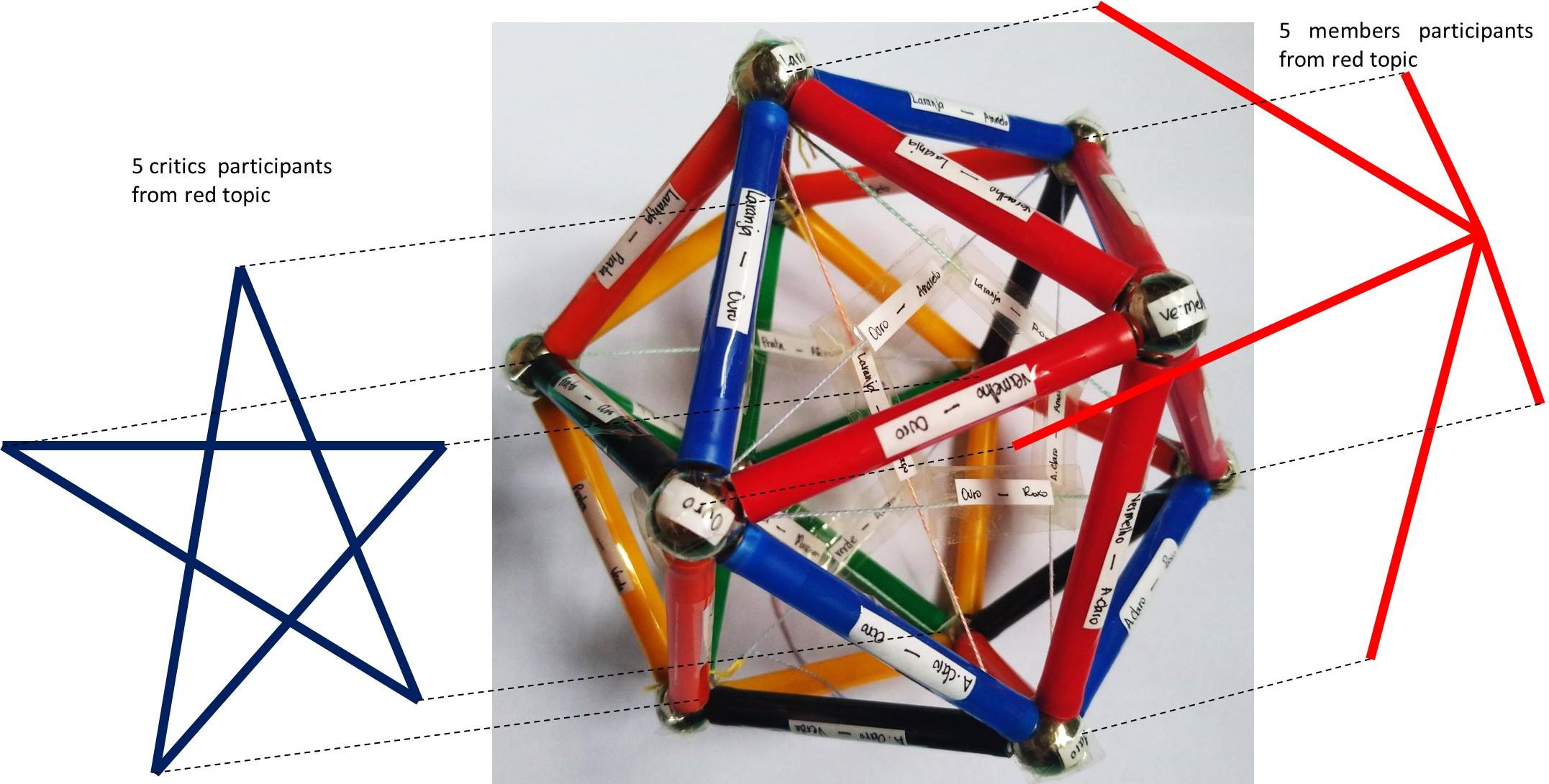

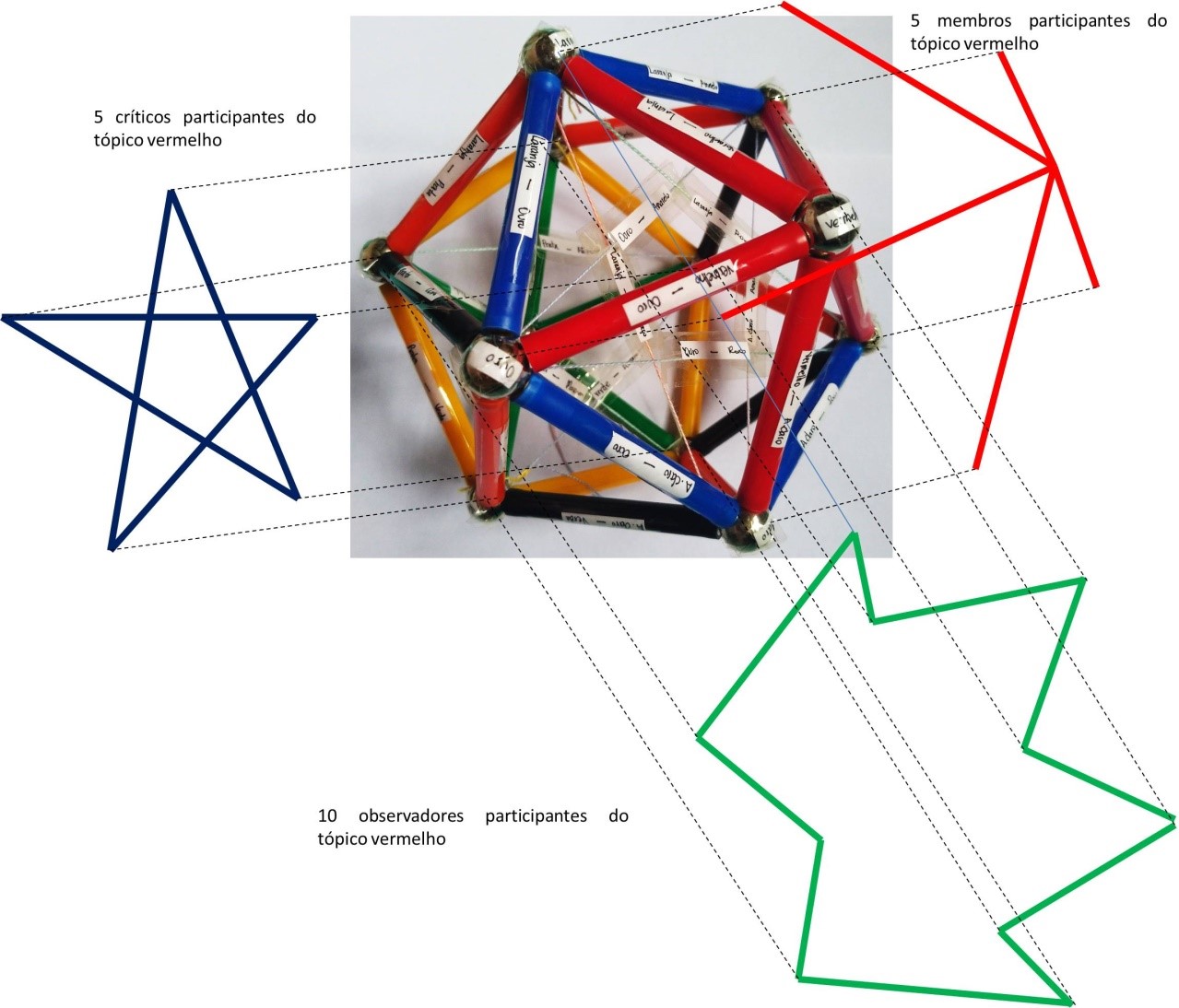

Segundo Ríos (2011, p. 210), no ato da discussão do tópico vermelho, os cinco membros participam de forma direta e os críticos de forma indireta, e dessa forma temos um grupo de 10 pessoas envolvidas no processo, adicionadas a 10 observadores. Estes são membros que conectam os membros do tópico vermelho com os críticos opostos, configurando assim um grupo de 20 pessoas, representado no modelo pelas arestas de cor laranja e preto e na projeção pela cor verde da Figura 3. Os observadores participantes na tabela de Beer são ouro-verde, verde-azul claro, azul claro-marrom, marrom-roxo, roxo-azul escuro, azul escuro-amarelo, amarelo-preto, preto-laranja, laranja-prata e prata-ouro.

Legenda: Icosaedro com discussão do tópico vermelho: à direita, membros - vermelho; à esquerda, críticos – azul; em baixo, observadores – verde.

Fig. 3: Icosaedro: observadores. Fonte: As autoras.

Beer estruturou o Infoset e definiu esse ‘conjunto de informações’ de acordo com sua percepção das limitações do VSM:

Eu propus que o que levava as pessoas a grupos coesos era a informação compartilhada que as transformara em indivíduos com uma meta. Os dados em si não fornecem essa coesão: é a interpretação dos dados que adquire propósito, e é a interpretação compartilhada entre os indivíduos que obtêm a coesão do grupo. Assim grupos deste tipo foram nomeados como infosets (BEER, 1994, p. 10, tradução nossa).

Para assegurar a coesão de grupos, estes deveriam compartilhar as informações, formando indivíduos com propósitos para garantir o funcionamento de grupos com uma consciência coletiva. Para tal, Beer compreendeu o icosaedro como um meio capaz de promover a discussão e tornar a coesão almejada viável. Assim, Beer absorveu e retransmitiu as propriedades estruturais da forma para atingir suas propostas. O ciclo homeostático entre o Subsistema 3 e 4 foi desenvolvido para remediar as questões de diálogo interpessoais, e funciona de maneira que:

[...] algum nó dentro do sistema propaga uma ideia, que então salta para outros nós - e retorna (um pouco modificada) para atingir seus progenitores [...]. Esse conceito de Reverberação passou a significar para mim a instrumentalidade da tensegridade dentro do Infoset: ele gera sinergia. [...] Boris Freesman sugeriu que minha própria ênfase na sinergia atribuível à reverberação deveria ser reconhecida. Ele cunhou a palavra Syntegrity, que reúne a tensegridade sinérgica, e Team Syntegrity tem sido o nome dessa técnica desde então (BEER, 1994, p. 13-14, tradução nossa).

O uso do icosaedro como modelo estrutural organizacional trouxe para Beer a possibilidade de estabelecer uma rede de interações sinergéticas. Como a rede se constrói através do modelo geométrico, em que 12 tópicos são discutidos simultaneamente por 5 indivíduos, sendo que cada indivíduo discute dois tópicos ao mesmo tempo e fazem parte de outro grupo de maneira indireta, o Infoset como um todo, se estrutura com 30 conexões diretas, somadas a 30 conexões indiretas, totalizando uma teia com 60 conexões. A conectividade entre os indivíduos e as discussões sobre o tema não trazem soluções repetidas, abrindo-se oportunidades para vários pontos de vista sobre um mesmo tema (BEER, 1994, p. 15), permitindo um alto nível de variedade e assim garantindo tomadas de decisão mais coerentes.

A estrutura do icosaedro, em termos organizacionais, é concebida por meio de protocolos, nos quais são definidos os participantes, os tópicos que serão abordados, as posições tanto dos tópicos como das pessoas dentro do icosaedro e as funções atribuídas a cada um.

3Considerações

O detalhamento sobre a organização humana no Syntegrity é importante para enfatizar a forma como essa estratégia evidencia as conexões entre os membros que participam do processo, criando uma rede sinérgica que torna o processo colaborativo, promovendo solução de conflitos interpessoais e discussão de temas sem sobreposição de energias dentro do sistema.

A implantação de sistemas colaborativos para o processo de projeto arquitetônico pode atualizar a forma como pensamos o mesmo. Com outro olhar para o desenvolvimento projetual, a Cibernética permite a reestruturação de forma a garantir uma coesão do sistema como um todo, bem como a sinergia entre as partes que o compõe, ou seja, a colaboração em função de uma evolução do sistema organizacional.

Por tanto, o processo de projeto pode se utilizar de teorias e conceitos cibernéticos para a promoção de processos colaborativos e a relevância de outros meios com avanços frente a implantação do conceito BIM.

Referências

ASHBY, W. R. Design for a brain: the origin of adaptative behaviour. 2a ed. Revi. Londres: Chapman and Hall, 1960.

BEER, A. S. The heart of enterprise: the managerial cybernetics of organization. Nova Iorque: Wiley, 1979.

BEER, A. S. Brain of the firm. 2a. ed. [s.l.]: Wiley, 1981.

BEER, A. S. Diagnosing the system for organization. [s.l.]: Wiley, 1985.

BEER, A. S. Beyond dispute. Chichester, Nova Iorque, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapura: John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

BERTALANFFY, L. V. General System Theory: foundations, development, applications. Nova Iorque: George Braziller, 1969.

FULLER, B. Synergetics: explorations in the geometry of thinking. [s.l.]: Macmillan Publishing, 1975-79.

RÍOS, P. Chapter 5: Team Syntegrity. In: RÍOS, P. Design and diagnosis for sustainable organizations. Berlim, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011. p. 201–216.

1 William Ross Ashby (1903-1972): Nascido em Londres, Inglaterra, se graduou em Zoologia e se especializa mais tarde em psiquiatria, passa 40 anos da sua vida em um processo de entender o cérebro e tentar reproduzi-lo como uma máquina. Faz parte Cibernética de Primeira Ordem (1940 a 1960) no qual o objetivo é observar o processo.

2 Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972): Nascido em Viena, na Áustria, estudou os organismos e publicou o livro sobre Teoria Geral de Sistemas na década de 1960, que revolucionou a forma de pensar, dando abertura para a evolução das teorias que emergiram antes deste período, inclusive a Cibernética. A Cibernética de Segunda Ordem (1960-1990) surge através de novas propostas de comunicação, na qual o observador é incluído no processo.

3 Anthony Stafford Beer (1926-2002): Nascido na Inglaterra, ele estudou filosofia, mas teve de interromper para incorporar o exército britânico na Segunda Guerra Mundial, foi contratado pelo governo do Chile em 1972 para desenvolver um sistema computadorizado em tempo real para gerir a economia social, mas abandonou o projeto em 1973. Faz parte da Cibernética de Segunda Ordem (1960-1990).

4 Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983): Nascido nos Estados Unidos, ele estudou arquitetura, mas pode ser considerado um inventor visionário. Fez serviço militar no período da Primeira Guerra Mundial, em 1932 teve um momento de introspecção que mudou sua forma de enxergar a vida e começa a propor novas formas de viver através do uso de tecnologias inovadoras. Faz parte do período anterior à Cibernética de Primeira Ordem (1940-1960) e Segunda Ordem (1960-1990).

5 Syntegrity: SYNERGY (sinergia) + TENSEGRITY (integridade de tensão).

Synergy in action: collaborative design process

Mariah Guimarães Di Stasi is an Architect and Urbanist. She studies cybernetic aspects of architectural design processes at Nomads.usp, University of São Paulo.

Anja Pratschke is an Architect, Doctor in Computer Science and Livre-docente in Architecture and Urbanism. She is an Associate Professor and researcher at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo. She co-coordinates Nomads.usp, by developing and guiding research on digital design processes in architecture, cybernetics, and information organization.

How to quote this text: Di Stasi, M. G. and Pratschke, A., 2019. Synergy in action: collaborative design process. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 18. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus18/?sec=6&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

Abstract:

This article is the result of the master's research in the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo. The investigation led us through cybernetic subtheories that corroborate with collaborative architectural design process. For the understanding of the conceptual bases, we studied the Viable System Model, as well as Team Syntegrity, by the cyberneticist Stafford Beer. The strategies for management against cybernetic resources showed us another way of observing the processes culminating in possible indicators for collaboration in Architecture.

Keywords: Architectural design, Collaboration, Cybernetics, Synergy

1Introduction

Currently, the architectural design process has been revised in order to discuss the importance of factors and agents involved in the design course. With the advancement of collaborative concepts like BIM (Building Information Modeling) for architectural design process, the relevance of understanding observation and organization of progress has led us to Cybernetics. Cybernetics emerged in the 1940s with the first investigations of information processing related to the human brain, developed by William Ross Ashby1 (1960) in his book Design for a Brain, becoming the First Order Cybernetics. In 1960, with the emergence of the General Systems Theory by Ludwig von Bertalanffy2 (1969), Cybernetics enters the Second Order, covering the field of process observation to a more holistic extent. In Second Order Cybernetics there were advances in critical thinking and proposals of social organizations, as was the strategies outlined by Anthony Stafford Beer3, reverberating in the investigation of this article.

Cybernetics was built in an interdisciplinary way, with the development of theories and concepts from different areas. The transdisciplinary complementarity has brought aspects to Cybernetics that allows us to retransmit ideals for the architectural design process, with approaches that we need, such as information processing and collaborative organizations.

Based on this imposition, we return our investigation to both organizational and collaborative cybernetic strategies, developed by Stafford Beer. Beer studied throughout his life mathematical and biological patterns, initially through analyzes of the brain and the human nervous system. The VSM (Viable System Model), elaborated between 1972 and 1985, is an organizational system realized through the human nervous system.

Through the publication of three main books on VSM, Brain of the Firm (Beer, 1972, 1981), The Heart of Enterprise (Beer, 1979) and Diagnosing the system for organizations (Beer, 1985), Beer raised a systemic thought for the structuring of self-organized social coordination. The VSM feature was designed to structure companies, both in operation and in organization, through five interconnected subsystems.

However, Beer denoted that the connection between subsystem 3 and 4 was insufficient for the advance of the whole system. The subsystem 3 is responsible for managing the running process, while subsystem 4 is responsible for the projection of any system in a future scope.

2Synergy in the Viable System Model

Beer realized that the Viable System Model needed to integrate other aspects to respond to increasing challenges of complex organizations, since VSM was limited in building a group with collective consciousness and with collaborative participants. He set out from a three-dimensional geometric form to solve what he considered the soul of the VSM:

The cybernetics expressed by the VSM is available to help.And if, as has been argued, the primary problem is the proper functioning of the Three-Four homeostat, then that would be a good place to start. We need to metabolize the creative and the synergetic resources of the enterprise. The directive management team of an enterprise is perhaps the most virile example of an infoset with which society is familiar (Beer, 1994, p.159).

In this case, Beer considered that the relationship between subsystems 3 and 4 was relevant for the operation of the whole company and decided that this issue needed to be solved differently (Ríos, 2011, p.201):

The need of a tool for facilitating communication between System 4 and System 3 in an organisation was made clear by Beer himself when the VSM was introduced. Its last innovation, termed Team Syntegrity (TS) (Beer, 1994), was duly developed in order to help these two systems to communicate adequately and, as a result, to contribute to the smooth running of the System 4-System 3 homeostat, which, as we know, is critical for ensuring the organisation’s adaptation and viability (Ríos, 2011, p.201).

A communication way was important to facilitate the interaction between System 3 and 4 becoming essential to keep VSM viable, thus reflecting the interconnectivity between VSM and Team Syntegrity. Therefore, in 1994 Beer proposed the Team Syntegrity to provide the collaboration between the two subsystems. So, the objectives of a communicative way should have the following premises:

– To generate a high level of participation among the individuals concerned; – To provide a structure and a system of communication that guarantee the nonhierarchical nature of the process; – To benefit from the variety and wealth of knowledge supplied by each individual within the group, putting into practice the synergies derived from the interaction among all its members; – To create a collective awareness, if possible shared among all the members of the group, regarding the central issue being considered and analysed (Ríos, 2011, p.205).

Concerning this, Beer believed to build a collaborative team system in which there was a synergy between all the participants of the process, generating a high variety due to diversity of people and collaboration from a non-hierarchical collective consciousness. For the idealization of this structure, Beer resorted to the North American architect Richard Buckminster Fuller4, when he said that:

Then I stumbled on an old gift from Buckminster Fuller - an inscribed time map of his own life - and started to think more about his geodesics. [...]. And I heard again in my own head Bucky's dictum: all systems are polyhedra. It is an amazing insight (Beer, 1994, p.12).

Defined by Fuller as the "[...] behavior of integral, aggregate, whole systems unpredicted by behaviors of any of their components or subassemblies of their components taken separately from the whole" (Fuller, 1975-79, p.102.00). Which means, the parts jointly make up a system that can determine the characteristics of the whole, however, separated, may not exhibit the same behavior.

Beer relies on the principles of the homeostatic machine, applied to the interaction and connection between people. He establishes a structure of relationships called SYNTEGRITY5:

The structure that we seek must reflect the notion of a perfect democracy, as was argued before. It surely means that no individual, and initially no cause, should have ascendance over any other. Then in looking for polyhedra on which to construct democratic tensegrity models, we must consider only regular polyhedra: figures which have no top, no bottom, no sides - indeed no features by which they may be specially oriented at all (Beer, 1994, p.14).

Beer proposed a non-hierarchical and democratically perfect structure to face the challenges (Beer, 1994, p.12), adopting the form of geodesic domes.

The word tensegrity used by Beer comes from Fuller's explanation about tension and compression forms, as well as the geodesic behavior. Therefore:

[…] the wholeness, the INTEGRITY, of the structure is guaranteed not by local compressive stresses where structural members are joined together, but by the overall tensile stresses of the entire system. Hence came the portmanteau for Tensile Integrity: TENSEGRITY (Beer, 1994, p.13).

Therefore, Beer was based on the integrity of the tension of a system as a whole, in which a unity of social organization was observed. In addition, Beer also understood that these forces of compression and tension promoted other structural questions, when he said that:

Fuller formulated the idea that nature exists in an equilibrial balance between the forces of compression and tension. Obviously the existence of both forces was already known, but their collaborative coexistence in all physical systems had not been emphasized (Beer, 1994, p.12).

Hence, Beer understood the icosahedron, the geometric basis of the geodesic, as a form founded on balanced forces of compression and tension and he used to reformulate the model of organization, when he said:

I decided to base my major experiments on the icosahedron, and to consider the edges as representing infosets members (namely 30) and the vertices as representing topics or key issues (namely 12), with the result that the edges conjoining at each vertex (namely 5) would be protagonists for each topic (Beer, 1994, pp.14-15).

From then on, Beer began to consider the geometric form of the icosahedron to compose his social organization. An icosahedron has 12 vertices, out of which 5 edges, totaling 30 edges. Beer regarded the vertices as discussion topics and the edges as the people involved, so 30 people would discuss 12 topics. Beer took into account the icosahedron as a whole and called it Infoset. Therefore, his Infoset would consist of a group of 30 individuals and 12 topics, in which five people would directly discuss a topic.

Figure 1 can show to us all possible connections within a Team Syntegrity, which is composed by direct links, those structured by team members who discuss a topic, and indirect links, composed by the critics of the topics generated by opposite face of the discussed vertices.

With this integrated network it is possible to construct the icosahedron and stipulate the direct, indirect and opposite connections for the construction of the synergic structure.

The icosahedron has a unique symmetry, in which there is similarity in any position in which it is being divided, that is, any quadrants will always have the same symmetry that other parts. Thus, we can consider that its vertices always have an opposite pole and therefore we have 6 sets of two vertices that oppose each other. In the following image we can see an icosahedron in which we see and consider its poles as the red and white vertices, being: the red vertex, with its edges represented by red in both the model and the projection. It has the names of the edges with double colors, since the member participates in two topics at the same time. Thus, in the red topic we have the following participants: red-purple, red-yellow, red-orange, red-gold, and red-light blue. These five participants contribute to the discussion of the red topic and the respective topics that interconnect the participants (Figure 2), as explained by Ríos (Ríos, 2011, pp.208-209).

At its opposite pole, being the white in Figure 1 of Beer’s table, and drawn in blue in Figure 2, the discussion topics surrounding the white topic form a star with the members that interconnect this face of the icosahedron. In the model these are represented by wires with their names and the projection is in blue. The five participants are black-green, silver-dark blue, black-brown, dark-blue green and silver-brown. These members are connected in a way indirectly to the red topic, acting as external critics of the contributions and evolutions that occur in the topic. The same occurs in the opposite position, the star surrounding the red topic acts as a critic of the white topic and this happens on all faces, as demonstrated by Ríos (2011, pp.208-209).

According to Ríos (2011, p.210), in the red topic discussing act, the five participants contribute directly as members and indirect way as critics. Thus, we have a 10 people group involved in the process, added to 10 observers. The observers are members that connect the red topic direct participants with opposing critics, configuring a 20 people group.They are represented in the model by the orange and black color edges and by the green color projection of Figure 3. In Beer’s table, the observers are gold-green, light blue green, light blue-brown, purple-brown, purple-blue, dark-blue, yellow-black, black-orange, silver-orange, and silver-gold.

Beer structured the Infoset and defined this 'information set' according to his perception of the VSM limitations:

I proposed that what brought people into cohesive groups was the shared information that had changed them into purposive individuals. Data themselves do not supply this cohesion: it is the interpretation of data that procures purpose, and it is the shared interpretation between individuals that procures group cohesion. Thus groups of this kind were nominated as infosets (Beer, 1994, p.10).

To ensure the groups cohesion, people should share information, forming individuals with purposes to ensure the functioning of groups with a collective conscience. Therefore, Beer understood the icosahedron as a means capable of promoting discussion and making the intended cohesion viable. Thus, Beer absorbed and retransmitted the structural properties of the form to reach his proposals. The homeostatic cycle between Subsystem 3 and 4 has been developed to address interpersonal dialogue issues, and works in a way that:

[…] some node within the system propagates an idea, which then bounces round other nodes - and returns (somewhat modified) to hit its progenitors […]. This concept of Reverberation came to mean to me the instrumentality of tensegrity within the Infoset: it generates synergy. […] Boris Freesman suggested that my own emphasis on the synergy attributable to reverberation should be acknowledged. He coined the word syntegrity, which draws together synergetic tensegrity, and Team Syntegrity has been the name for this technique ever since (Beer, 1994, pp.13-14).

The icosahedron use as an organizational structural model has brought to Beer the possibility of establishing a network of synergistic interactions. As the network is constructed through the geometric model, in which 12 topics are discussed simultaneously by 5 individuals. Each individual discusses two topics at the same time and acts also indirectly in another group.The Infoset as a whole is structured with 30 direct connections, added to 30 indirect connections, totalizing a web with 60 connections. Connectivity between individuals and discussions on the subject does not bring about repeated solutions, opening up opportunities for several points of view on the same theme (Beer, 1994, p.15), allowing a high level of variety and thus ensuring decision-making.

The icosahedron structure, in organizational terms, is conceived through protocols, in which the participants are defined, the topics to be addressed, the positions of both topics and people within the icosahedron and the functions assigned to each one.

3Considerations

The detailing about human organization in Syntegrity is important to emphasize how this strategy evidences the connections between members participating in the process. This enables a synergistic network that makes the process collaborative and promote solution of interpersonal conflicts and discussion of topics without overlapping energies within the system.

The implementation of collaborative systems for the architectural design process can update the way we think. With another look at the design process, Cybernetics allows the restructuring in order to ensure cohesion for the whole system. Also promotes synergy between the parts that compose it, that is, collaboration in function of an evolution of the organizational system.

Therefore, the design process can used cybernetic theories and concepts to encourage collaborative processes and the relevance of other means with advances towards BIM concept implementation.

References

Ashby, W. R., 1960. Design for a brain: the origin of adaptative behaviour. Second Edition Revised ed. London: Chapman and Hall.

Beer, A. S., 1979. The heart of enterprise: the managerial cybernetics of organization. New York: Wiley.

Beer, A. S., 1981. Brain of the firm. 2nd ed. [s.l.]: Wiley.

Beer, A. S., 1985. Diagnosing the System for Organization. [s.l.]: Wiley.

Beer, A. S., 1994. Beyond dispute. Chichester, New York, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons.

Bertalanffy, L. v., 1969. General System Theory: foundations, development, applications. New York: George Braziller.

Fuller, B., 1975-79. Synergetics: explorations in the geometry of thinking. [s.l.]: Macmillan Publishing.

Ríos, P., 2011. Chapter 5: Team Syntegrity. In: Design and diagnosis for sustainable organizations. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp.201–216.

1 William Ross Ashby (1903-1972): Born in London, England, graduated in zoology and later specialized in psychiatry, he spent 40 years of his life in a process of understanding the brain and trying to reproduce it as a machine. It is part Cybernetics of First Order (1940 to 1960) in which the objective is to observe the process.

2 Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972): Born in Vienna, Austria, he studied the organisms and published the book on General Systems Theory in the 1960s, which revolutionized the way of thinking, opening up the evolution of the theories that emerged before of this period, including Cybernetics. Cybernetics of the Second Order (1960-1990) arises through new communication proposals, in which the observer is included in the process.

3 Anthony Stafford Beer (1926-2002): Born in England, he studied philosophy but had to discontinue incorporating the British Army into World War II, was hired by the government of Chile in 1972 to develop a real-time computerized system to manage the social economy, but abandoned the project in 1973. It is part of the Second Order Cybernetics (1960-1990).

4 Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983): Born in the United States, he studied architecture, but can be considered a visionary inventor. He did military service in the period of World War I, in 1932 he had a moment of introspection that changed his way of seeing life and began to propose new ways of living through the use of innovative technologies. It is part of the period prior to the Cybernetics of First Order (1940-1960) and Second Order (1960-1990).

5 Syntegrity: SYNERGY + TENSEGRITY (integrity of tension).