O Diagrama como Máquina Abstrata

Georges Teyssot é Arquiteto e pesquisador, vive no Canadá. Atualmente, é professor titular na Laval University’s School of Architecture em Quebec. Sua Pesquisa e o seu ensino discutem a invenção de dispositivos espaciais, arquiteturais e tecnológicos, relacionados a habitação de sociedades industriais e pós-industriais ocidentais.

Como citar esse texto: TEYSSOT, G. O Diagrama como Máquina Abstrata. Traduzido do inglês por Paulo Ortega. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 7, jun. 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=3&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

Originalmente publicado em Georges Teyssot, “The Diagram as Abstract Machine”, in Diagram, Odile Decq, with Sony Devabhaktuni, eds., Paris, ESA (École Spéciale d’Architecture), forthcoming. A revista V!RUS agradece pela gentil permissão para re-publicação aqui do artigo

Resumo

Seja em gráfico ou tabela, o diagrama arquitetural é hoje, onipresente. Como a inscrição gráfica de abstração no espaço, desde 1990, a noção de diagrama tem sido tão estendida, que abarca cada aspecto do design. Ao pensar no diagrama como uma arquitetura de ideias, (ou, mais classicamente, a ideia de arquitetura), significa estar, ainda, assentado em algumas espécies de concepções platônicas (GARCIA, 2010). Para evitar esta armadilha, um primeiro passo seria voltar-se para a noção de Gilles Deleuze sobre o diagrama como um mapa abstrato, e expor como o modelo adquire seu significado, especialmente quando confrontado com paradigmas biológicos. Tal entendimento pode levar a uma melhor compreensão da atual natureza algorítmica dos diagramas. Esses procedimentos gravados referem-se à forma, ou, mais precisamente, à processos de morfogênese. Seu objetivo é aprimorar uma modulação entre componentes naturais, elementos físicos e o design arquitetural. Uma variação de práticas (ou protocolos), baseadas em um programa adaptável (customizável), capaz de produzir modalidades de mudança de uma topologia estrutural motivada pela performance, estão atualmente disponíveis (TEYSSOT; BERNIER-LAVIGNE, 2011). Por exemplo, referindo-se a questão do uso do algoritmo genético no design, Manuel de Landa, inspirado pelo trabalho de Deleuze, propôs a introdução de três níveis teóricos de complexidade: pensar em termos de população (não o individuo); pensar em termos de diferença de intensidade (termodinâmica e entrópica); e, por último, pensar em termos de topologia (DE LANDA, 2002). A questão abordada aqui será, portanto, para saber se (e como) o diagrama é capaz de topologizar os vários campos de design1

Palavras-chave: Diagrama, design, meios digitais

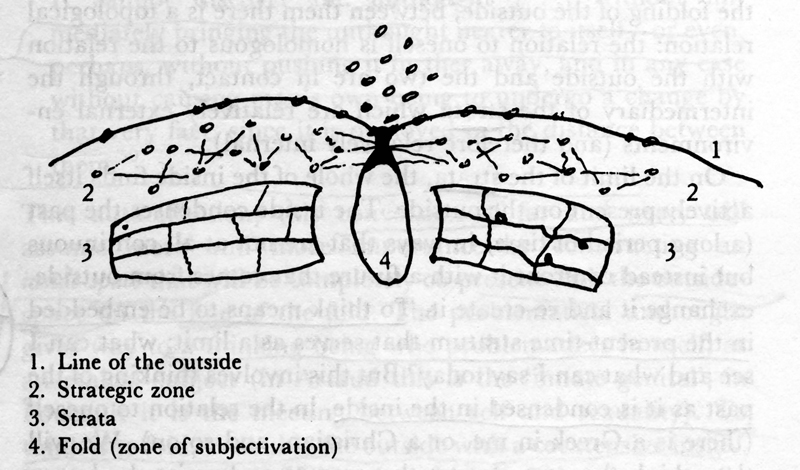

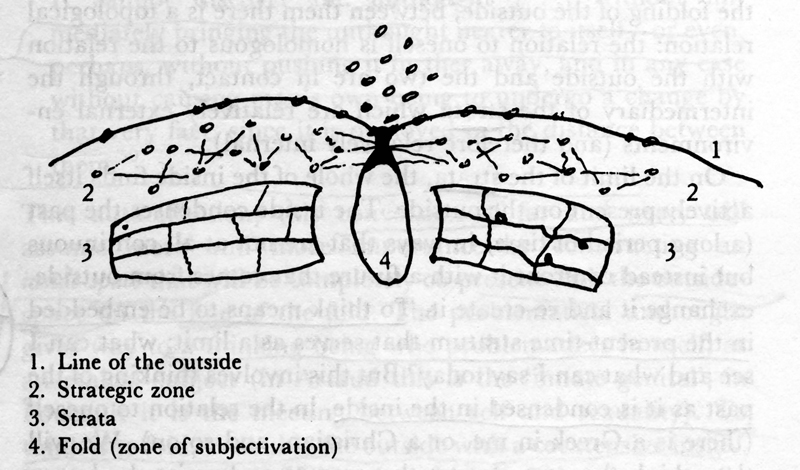

Figura 01: “Diagrama e Topologia da Dobradura de Michael Foucault” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 120, tradução nossa).

Morfogênese

Como Deleuze escreve em Diferença e Repetição (1994 [1968]), nós vivemos em um mundo regido por uma “distribuição completamente diferente que deve se denominada nomádica, um nômade nomos, sem propriedade, fechamento ou medida” (DELEUZE, 2002, p. 36, tradução nossa ). O problema, atualmente, não é mais a distribuição das coisas e a divisão das pessoas em espaços sedentários, “mas sim a divisão entre aqueles que se distribuem em um espaço aberto – um espaço que é ilimitado, ou ao menos sem limites precisos...” Preencher um espaço, ser distribuído dentro deste, é algo muito diferente de distribuir este espaço” (DELEUZE, 2002, p. 36, tradução nossa ). O salto de estruturas sedentárias para a representação da distribuição nomádica, traz dificuldades perturbadoras, transcendendo todos os limites, e implementando “uma errante e até mesmo ‘delirante’ distribuição” (DELEUZE, 2002, p. 37, tradução nossa ). Distribuições sedentárias, em bom sentido e também em sentido comum, são todas baseadas de acordo com uma síntese do tempo, que tem sido determinado como aquele do hábito (DELEUZE, 2002, p. 225). Por outro lado, estruturas nomádicas levam a “repartição insana..., distribuição insana – instantânea, distribuição nomádica, anarquia coroada ou diferença” (DELEUZE, 2002, p. 224, tradução nossa ). Tal é o estado que a física descrita em termodinâmica, de Sadi Carnot a Rudolf Clausius e Ludwig Boltzmann (cuja equação descreveu a difusão de partículas de gás em um método estatístico): ou seja, entropia (DELEUZE, 2002, p.225-229).

Para Deleuze, é necessário reconhecer a prioridade das forças múltiplas sobre a forma. Em Diferença e Repetição, ele identifica essa ligação entre forças e formas como os dois vetores da diferença, utilizado Henri Bergson e Gilbert Simondon como fontes (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 88-89). Para Simondon, a individualização do cristal é a formação física obtida por uma diferença de potencial. Esta diferença é a seta entrópica entre tensão e matéria (como em um cristal) (DELEUZE, 2004, p. 86-89). Deleuze traduz essa diferenciação em termos de oscilação, uma vibração simultânea entre o real e o virtual, que é coexistente. Superando a oposição de Bergson entre matéria e duração, ele transpõe a flecha de intensidade em um modelo de coexistência do virtual e do real (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 208-209). Ambos estados são reais, mas o real caracteriza o individuo completo, tal como o cristal materializado, enquanto o virtual refere-se ao campo problemático do pré-individual, quando a diferenciação intensiva ainda não está efetivada. Para ilustrar isto, Deleuze, de acordo com Simondon, utiliza o modelo de um ovo, o paradigma de um corpo intensivo, literalmente um corpo sem órgãos, porque se trata de um corpo em fases de diferenciação (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 90).

A realização ocorre nas coisas através de um processo de diferenciação. A embriologia mostra que a divisão de um ovo em partes é secundária em relação a movimentos morfogênicos mais significantes. Deleuze descreve a cinemática de um ovo, através de seus vários processos (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 214). A diferenciação de espécies e partes pressupõe todo um estabelecimento de dinâmicas espaço-temporais. “O mundo todo é um ovo” (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 216, tradução nossa ). Entretanto, se o mundo é um ovo, então o ovo em si é um teatro: um palco com atores, espaços, e ideias, e onde um drama espacial é encenado. Para substanciar essa conclusão, Deleuze emprega múltiplas fontes, incluindo a tese de Étienne Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, sobre a cinética da dobradura; e a hipótese de Karl von Baër sobre movimentos morfogênicos, incluindo o alongamento de camadas celulares, invaginação por dobramento, e a orientação e eixo do movimento, tudo para ser encontrado na cinemática do ovo (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 214). Acrescentando a isso, Deleuze menciona a teoria da gradação de Charles Manning Child, que oferece uma estrutura para o pensamento sobre arranjo formal, e o paradigma de gastrulação anfíbia de Paul Weiss, apresentada em 1939 em seu livro Princípios de Desenvolvimento, que elucida como processos morfogênicos são capazes de moldar a forma (DELEUZE, 1994, p.250).

Na filosofia, a fonte principal foi o trabalho de Raymond Ruyer, que, inspirado pela etiologia de Jakob von Uexküll (2010 [1921]), elaborou uma filosofia de diferenciação já em 1939. Para Ruyer (1958, p. 185), em todos os domínios, a forma é dotada de um ritmo próprio. Em seu livro de 1958, A gênese das formas vivas, Ruyer (1958, p. 140) discute o dinamismo espaço-temporal na migração celular e estabelece uma distinção entre morfologia e morfogênese (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 173, p. 185, tradução nossa ): “Morfologia, o estudo das formas e seus arranjos, [...] não apresenta nenhuma dificuldade fundamental”, porque conta com a visão e descrição, enquanto a morfogênese, “apresenta... o máximo de dificuldade e mistério” (JOEOHTHESTARS, 2007, tradução nossa ). Se Deleuze (1994, p. 216, p.330) adquiriu ideias sobre dramatização espacial e o mistério da diferenciação pela obra de Ruyer, não fica claro se os dois filósofos concordaram que o virtual não desapareceu uma vez que a individualização (e a diferenciação) fossem completadas2Para Deleuze, a forma não é o que resta de uma ação física, tampouco o resultado de uma força reduzida: é o resultado de um estado de equilíbrio temporário entre forças (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 222-223, p. 228-229, p. 240-241; SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 90).

Como anteriormente indicado, em Diferença e Repetição, Deleuze tentou, portanto, desenhar uma teoria da diferença, em parte baseada em diferenciação biológica, fornecendo um novo sentido para as mitologias antigas do mundo ovo, com início no ovo cósmico Anaximander, enquanto ele também proveu uma interpretação renovada do ditado biológico de Willian Harvey, (1651): ex ovo omnia (“tudo vem do ovo”, tradução nossa ):

A fim de sondar profundidades intensivas ou o spatium de um ovo, [...] os potenciais e as potencialidades devem ser multiplicados. O mundo é um ovo. ... Nós pensamos que a diferença de intensidade, assim como está implicado no ovo, expressa, primeiramente, as relações diferenciais ou a matéria virtual a ser organizada (DELEUZE, 1994, p. 250-251, tradução nossa ).

Além do mais, perpassando uma ponte entre suas teorias, Deleuze contou também com a morfogênese embriológica do biólogo belga Albert Dalcq (DALCQ, 1941), em adição à teoria de individualização de Simondon. A epigênese de Dalcq oferece um modelo para as diferenciações modus operandi, que estava no centro da tese de Deleuze. A popularidade do trabalho de Dalcq, na década de 1950, entre artistas e arquitetos, era a mesma de D’Arcy W. Thompson Em Crescimento e Forma (1944 [1917]). Mais um tratado em morfologia do que uma teoria morfogênica, a edição de D’Arcy Thompson argumentou que a evolução havia sido superenfatizada como o determinante fundamental das formas de seres vivos, e propõe processos mecânicos de transformação igualmente importantes na modelação da vida. (THOMPSON, 1917).

É digno de nota, que o livro de Albert Dalcq sobre embriologia foi à primeira fonte em epigênese, tanto quanto os designers por trás da exposição, “Em crescimento e forma”, sediado no Instituto de Artes Contemporâneas em Londres em 1951, o título que foi inspirado pela nova edição de D’Arcy Thompson, Em crescimento e forma (1944), assim como Gilles Deleuze3. Lida através das lentes das filosofias de Spinoza, Leibniz e Bergson, a teoria de Simondon sobre a individualização ajudou a identificar o ovo como uma vasta metáfora do mundo. Se a filosofia de Deleuze sobre natureza pôde antecipar a ciência de seu tempo, é porque ele teve sucesso na identificação das metáforas contemporâneas que suportaram suas conceitualizações, as mudanças do paradigma que foram promulgadas, juntamente com as significantes descobertas epistemológicas. Posicionado (como ele era) na oposição as tendências do estruturalismo, e, ao mesmo tempo, contrastando implicitamente os geneticistas obstinados que leem somente em códigos, Deleuze introduziu a metáfora do ovo que ajudou a rearticular a conexão entre o simbólico e o vital. Sem entrar no debate contemporâneo sobre biologia e genética, parece que a teoria de Deleuze não estava longe da posição sustentada pelo americano Stephen Jay Gould’s, Ontogenia e Filogenia, de 1977 (GUALANDI, 2011, p. 59-72).

Deleuze (2003, p. 41, tradução nossa ) geralmente usa o modelo do embrião para expor a vitalidade inorgânica dos tecidos, ainda não estabilizada no formato de um órgão, capaz de múltiplas transformações: “[…] o corpo sem órgãos não tem falta de órgãos, a ele simplesmente falta o organismo, isto é, a organização específica dos órgãos. O corpo sem órgãos é, então, definido por um órgão indeterminado, ao passo que o organismo é definido por determinados órgãos”. Em A lógica do sentido de Deleuze (1969, p. 88-342), tudo irá desmoronar em torno do paradigma de Antonin Artaud, cujo delírio poético e esquizofrênico clamava por um corpo além de sua determinação orgânica. Para Artaud, o organismo completo parecia uma forma que aprisiona o corpo (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 87-88). Durante os anos de 1970, Deleuze e Guattari nunca pediriam que alguém se privasse de seus órgãos, mas para que substituíssem a noção de um órgão totalmente desenvolvido através da concepção metamórfica e polimórfica de um órgão imaturo enquanto ele difere. A bio-filosofia de Deleuze ilustra a virtualidade de forças intensivas, enquanto elas operam anteriormente ao alcance e construção da forma orgânica. O que Deleuze e Guattari propuseram foi considerar os eixos virtuais das forças informais (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 90).

Resistindo ao neo-platonismos de tipos e modelos, Deleuze acredita que o que existe na imanência do mundo não é a cópia de um modelo que constituiria o molde ideal de indivíduos reais; o que é real não é o exclusivo e o único, ou transcendental, mas as singularidades e diferenças. O molde ideal é similar ao tipo ideal na história da arte, na arte ou design. Simondon elaborou uma critica precisa da ideia de um molde ao introduzir o conceito de modulação. Na modulação, Simondon escreve que “nunca há tempo de virar algo, de removê-lo do molde” (SIMONDON, 1964, p. 41-42 citado em DELEUZE, 2003, p. 108, tradução nossa ). Proceder com a tal desmoldagem (Fr., démoulage) é desnecessário, “porque a circulação do suporte de energia é equivalente ao virar permanente; um modulador é contínuo, um molde temporal” (SIMONDON, 1964, p. 41-42 citado em DELEUZE, 2003, p. 165, tradução nossa ). Enquanto a moldagem leva a um permanente estado das coisas, a modulação introduz o fator do tempo: “Moldar trata-se de modular de uma maneira definitiva, modular trata-se de moldar de uma maneira perpetuamente variável e contínua” (SIMONDON, 1964, p. 41-42 citado em DELEUZE, 2003, p. 165, tradução nossa ). Por todo seu trabalho, Deleuze também recomenda alterar a ideia de moldagem pela introdução daquela de modulação. Em 1978, por exemplo, ele afirmou (DELEUZE, 2006 [1978], p. 159, tradução nossa ): “Toda direção nos leva, eu acredito, a parar de pensar em termos de substância-forma”. Levando em consideração a crítica de Simondon sobre o hilemorfismo, opondo a matéria inativa à forma ativa, ele propôs substituí-la com um processo de modulação, em que a operação de dotação de forma seria concebida como a união de forças e materiais. Enquanto esta teoria ajudou Deleuze a escapar da semelhança, opondo-se à ideia de que um modelo necessita ser copiado, ele atingiu uma nova definição de atividades artísticas, como a captura de forças intensivas por novos materiais: “A união do material-força substitui a união do material-forma” (DELEUZE, 2006 [1978], p. 160, tradução nossa ). A ciência contemporânea mostra que o genótipo não é um molde que determina o indivíduo em um modo unívoco. Entre o genótipo e o fenótipo, insere-se um processo de desenvolvimento, onde a variável temporal tem um papel tão importante quanto as variáveis espaciais e topológicas4. A estrutura se atualiza através de um processo de desenvolvimento, introduzindo fatores como a variabilidade temporal e escolástica que singulariza o protótipo de indivíduo. Como deve ser claro, o pensamento de Deleuze não foi baseado em vagas metáforas ou tropos retóricos (GUALANDI, 2011, p. 64-65). Se é possível falar em metáforas, é em seu sentido mais nobre, uma vez que eles foram capazes de compreender questões teóricas mesmo em domínios que ainda não tenham sido claramente percebidos pela própria ciência.

Diagrama Intensivo

O corpo sem órgãos exprime a noção de matéria em um estado ainda não formado, de um corpo ainda não representado, ou um corpo irrepresentável em sua versão esquizofrênica. Superando a forma organizada, introduz-se a matéria como um receptáculo de forças. Além da oposição matéria-forma, além da forma organizada, há a matéria como uma mistura não formal de materiais e forças. Mais do que uma metáfora, o corpo sem órgãos refere-se à noção de máquina e de diagrama, desenvolvido, paralelamente, no trabalho de Michael Foucault, do qual Deleuze é um intérprete entusiasmado. O diagrama é um mapa, que coexiste com toda a sociedade, e forma uma “máquina abstrata” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 34). Lidando com fluxos, fluídos, funções, isto remexe a matéria, forma, energia, redes. Todo diagrama é uma “máquina diferente” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 34). Tal máquina visa a representação da relação de forças, pertencendo a uma formação estratificada, e isto duplica a estratificação (por exemplo, o estrato da história e da sociedade). Este diagrama intensivo não deveria ser concebido como uma estrutura permanente, nem pensado como uma forma pré-existente, e sim como um problema virtual – que é um complexo de forças (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2009, p. 442). Pode-se definir um diagrama pastoral, um grego, um romano, ou um feudal (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 85). Ou até mesmo um diagrama barroco. O diagrama, contudo, não é histórico, mas pertence a um fenômeno de transformação: “ele duplica a história com um senso de transformação contínua (devenir)”5 (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 35). Como observa Deleuze (1988, p. 86, tradução nossa ) em praticamente todos seus livros: “Há ... uma transformação de forças que permanece distinta da história das formas... É um exterior que está mais distante do que qualquer mundo exterior e até mesmo de qualquer forma de exterioridade”. Indissociável de sua atualização, o diagrama é utilizado para injetar um pouco de transformação em cada ponto da realidade estratificada (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2009, p. 423). O conceito do diagrama como uma máquina abstrata nos ajuda a compreender a realidade mecanizada e biológica e de tantos estratos, assim como instituições, tecnologias e aparatos; incluindo heterotopias (DEFERT, 2009, p. 36-61). Além disso, ajuda a caracterizar obras de arte, incluindo Em busca do tempo perdido, de Proust, a esquizofrenia poética de Artaud, ou a exibição da carne de Francis Bacon. O diagrama oferece as ferramentas para mapear o gênero e o filo da arte, sua filogênese assim como sua heterogênese.

Subsequentemente, busca-se o que Deleuze define como “O diagrama de Foucault”, uma espécie de diagrama de um diagrama, se não o diagrama principal, dividido por uma linha entre um exterior e um interior, o último sendo feito de zonas estratégicas e construção de camadas de estrato, na qual textos e imagens do passado são arquivados. No esquema desenhado por Deleuze, há uma dobradura gigante, que indica a posição de si própria na relação da tarefa de produção de novos modos de subjetivação. Deste modo, três agências (ou instâncias) são unificadas por uma dobradura, que age como um operador topológico (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 120). Exterior e interior são invertidos. Longe e perto convergem. De acordo com Deleuze, para Foucault, “Penso, logo existo” de Descartes, deveria ser substituído pela formulação renovada, penso, logo dobro: “A topologia geral de pensamento... termina no dobramento do exterior no interior” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 118, tradução nossa ). O pré-requisito urgente é construir um espaço interior que é completamente co-presente com o espaço exterior, “na linha da dobradura” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 118, tradução nossa ). Independentemente da distância dentro dos limites de qualquer espaço vital, vivenciado, “Todo espaço-interno está topologicamente em contato com o espaço-externo ... e esta topologia carnal ou vital, longe de se revelar no espaço, liberta um sentido de tempo que encaixa o passado no interior, origina o futuro no exterior, e leva os dois a se confrontar no limite do presente vivenciado” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 119, tradução nossa ). Como afirma Deleuze, assim é como Foucault compreende a duplicação, ou a dobradura: “Se o interior é constituído pela dobra do exterior, entre eles há uma relação topológica: a relação de ser homóloga à relação com o exterior e as duas estão em contato, através do intermediário do estrato que são ambientes relativamente externos (e, portanto, relativamente internos)” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 119, tradução nossa ).

É possível imergir em um arquivo feito de formas visíveis e corpos articulados; cruzar superfícies, gráficos, tabelas e curvas; e seguir fissuras a fim de alcançar um interior do mundo. Mas, ao mesmo tempo, também é necessário escalar para além do estrato a fim de alcançar o exterior, um elemento atmosférico (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 121, tradução nossa ): “O exterior informal é uma batalha, uma zona turbulenta e tempestuosa onde pontos específicos e a relação das forças entre estes pontos são jogadas. O estrato meramente coletou e solidificou a poeira visual e o eco sônico da batalha travada acima deles”. Porém, para Deleuze, “bem acima, as características específicas não possuem forma e não são corpos nem pessoas falantes” (DELEUZE, 1988, p. 121, tradução nossa ). Tanto para Focault quanto para Deleuze, o diagrama é uma “micro-física”6(DELEUZE, 1988, p. 121). Entretanto, lido por Deleuze, o diagrama de Foucault é revivido. Elevando-se acima da oposição estática entre forma e matéria, situando-se em uma dimensão energética, se torna possível pensar materialmente em termos de movimento e forças, e introduzir um potencial de deformação ativa no material.

Como Deleuze escreveu para se ter algo elevado “não significa ter um topo e um fundo ou ser ereto” (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 1994, p. 164, tradução nossa ). Pode-se desenhar “um monumento, mas um que poderá estar contido em algumas marcas ou algumas linhas, como um poema de Emily Dickinson” (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 1994, p. 165, tradução nossa ). Seguindo esta observação, seria possível tentar escrever uma breve história da linha, digamos, da “linha de beleza” de William Hogarth (1753) para a linha de Henry van de Velde como uma força, para as linhas flexionadas de Paul Klee (FRANZ et al., 2007), até a topologia de estrias utilizada em modelagens 2D/3D. Já na década de 1950, enquanto opondo-se ao Platonismo de Colin Rowe, Reyner Banham defendeu uma arquitetura topológica (BANHAM, 1955, p. 354-361). De repente, o que formou a base das categorias tradicionais do espaço vê seu significado transformado, pela transmutação, em uma superfície de contato topológica.

Espaços Fluidos

Hoje, uma questão permanece: como tem os conceitos topológicos sido introduzidos na arquitetura? Talvez, uma topologia especialmente refinada seja necessária para descrever a formação de vórtices e espirais, ou de espaços nomádicos, suaves, que são formados por relações táteis. Como Deleuze e Guattari esclareceram, essências são para ser encontradas ao longo de linhas cruzadas (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 1987, p. 263, tradução nossa ): “Clima, vento, estação, hora... Essência, bruma, brilho. Uma essência não tem fim nem início, origem ou destino; está sempre no meio; não é feita de pontos, apenas linhas. É um rizoma”. De lá, a distinção bem conhecida entre um espaço nômade, “liso”, em oposição a uma condição sedentária, “estriada” será desenvolvida por Deleuze e Guattari (1986, p. 53-54 OU 1987, p. 382, tradução nossa ): “... Há uma topologia extraordinariamente fina que conta não com pontos ou objetos, mas com a essência, em conjuntos de relações (ventos, ondulações de neve ou areia, a canção da areia ou o estalido do gelo, as qualidades táteis de ambos); é um espaço palpável, ou razoavelmente ‘tátil’, um espaço muito mais sonoro que visual... A variabilidade, a poli vocalidade de direções, é uma característica essencial de espaços lisos do tipo rizoma... O nômade, o espaço nômade, é localizado e não delimitado. O que é tanto limitado quanto restritivo é o espaço estriado”. Deleuze, inspirado, como sempre, por Simondon, reviveu o conceito de essência desenvolvido na filosofia escolástica de Duns Scott. A essência deriva do Latim, haecceitas, que significa “identidade”, de Haec, “esta coisa”.

Deste modo, a essência, ou individualização, ajudou a explicar a existência de indivíduos específicos. Com Scott, tal concepção opôs-se a teoria aristotélica de hilemorfismo, que sustenta que qualquer ser individual foi a criação da forma dinâmica aplicada sobre matéria indistinta, como se as criações da natureza fossem saídas de um escultor modelando argila. Derivado do grego, hilemorfismo (ou hilomorfismo) refere-se à imposição de uma forma ativa (morfo) em uma matéria passiva (hilo). Scott refutou esta teoria rejeitando a sugestão que determinados seres individuais pudessem ser a emissão de matéria indeterminada. Como previamente mencionado, Simondon criticará o hilemorfismo por sua abordagem estática, universalista e paralisada, e em vez disso, define individualização como um processo contínuo que consiste precisamente de uma modulação entre forma e informação (SIMONDON, 2005, p. 225)7. Tanto para Simondon quanto Deleuze devem-se considerar cuidadosamente os processos específicos de transformação-indivíduo, abrangendo a singularidade em cada ser8 (SIMONDON, 1992, p. 297-319).

Para Deleuze, a essência não é limitada por qualquer questão de escala (grande ou pequena), mas tem uma consistência peculiar que a conecta fisicamente ao fenômeno, tal como vapor, névoa ou nuvem, situações que confundem quaisquer limites ou fronteiras definidos. A essência congrega, formando grupos ou bandos. Inspirados pela teoria da música de Pierre Boulez, Deleuze e Guattari escrevem: “o modelo é do vórtice; ele opera em um espaço aberto em tudo que as coisas-fluxo estão distribuídas, em vez de traçar espaços fechados para coisas sólidas e lineares. É a diferença entre um espaço suave (vetorial, projetivo ou topológico) e um espaço estriado (métrico)”9. (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 1986, p. 18, p. 125, tradução nossa ). No primeiro caso o espaço é ocupado sem ser medido, enquanto o segundo espaço é medido a fim de ser ocupado, uma distinção tirada de Boulez. Como um bando, a arte, suave e “nômade” circula em um espaço aberto e conectado, em oposição a uma arte estriada, geométrica, centrada e autocontida. São na verdade, dois usos diferentes da medida: espaço suave que conta com uma “enumeração de números [que] é rítmica, e não harmônica. E não está relacionado à cadência ou medida [externa]” (DELEUZE; GUATTARI, 1986, p. 67, tradução nossa ), enquanto que o espaço estriado é baseado em uma medida homogênea, marcando a superfície em quadrados e reordenando tudo. Essa observação nos ajuda a diferenciar uma linha abstrata, desvendando seu espaço suave de um conjunto de desvios e torções – ou seja, de um espaço estriado sujeito às normas e ortogonalmente enquadrado por regras (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 232-234).

Deleuze havia lido Abstraçãoe e Empatia de Wilheim Worringer (1963 [1907]). Ele estava convencido que Worringer dera proeminência fundamental a linha abstrata ou primitivista “vendo-a como o princípio da arte e da primeira expressão da vontade artistica. Arte como máquina abstrata” (DELEUZE; GUATARRI, 1987, p. 496, tradução nossa ). Perseguindo a investigação, Worringer publicou Forma em Gótico (1927 [1911]))10, uma investigação psicológica de estilo, apresentada por ele como uma sequência de Abstração e Empatia. Deleuze também leu Forma em Gótico e o citou repetidamente a partir da tradução francesa (WORRINGER, 1967 [1941]): ”Das profundezas do tempo vem para nós o que Worringer chamou de linha abstrata e infinita do norte, a linha do universo que forma laços, tiras, rodas e turbinas, uma total ‘geometria vitalizada’ elevando-se para a intuição das forças mecânicas, constituindo uma poderosa vida inorgânica” (WORRINGER, 127 [1911], p. 41-42, tradução nossa ). O que diferencia a linha nomádica da ornamentação clássica são paradigmas da velocidade, da proliferação e da aceleração da transformação, que são todos característicos do espaço suave. Em tal espaço, a linha é livre de propósitos representacionais, bem como está desassociada das leis da métrica; assim como desvinculada das leis métricas; como tal, ela é liberta da simetria clássica, da repetição do motivo, e das estriações das coordenadas racionais. Todas essas características pertencem a arquitetura renascentista, que compõe a arte estável, clássica e “orgânica”.

1 A topologia, um ramo da matemática, estuda as propriedades dos objetos que são preservadas através de deformação contínua, como dobrar, torcer ou esticar. Ele pode ser usado para estudar a conectividade inerente dos objetos em qualquer espaço dimensional, enquanto ignoram a sua forma detalhada ou formato. A topologia estuda as características de figuras ou superfícies topológicas, tais como a garrafa de Klein, a fita de Möbius, ou o toro.

2 Ver Colonna, 2007.

3 Ver Albert Dalcq Form and Modern Embryology (1951), publicada em colaboração com o Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) para coincidir com a exposição “Growth and Form" (Londres, Verão 1951), cujo título foi inspirado na nova edição do D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form (1944).

4 Ver Prochiantz, 2008.

5 Não “evolution”, mas devenir, “transformar”, no texto original.

6 E não “micro-política”, como foi traduzido.

7 Veja a nova edição da tese de doutorado principal de Gilbert Simondon (1957) que combina L’Individu et sa genèse physico-biologique (publicado em 1964), que Deleuze leu, e LL’Individuation psychique et collective (publicado em 1989).

8 Ver também Simondon, 2012. O presente artigo foi escrito antes que a coleta de tais de ensaios estivesse disponível.

9 Os autorem citam Boulez on Music Today (BOULEZ, 1971, p. 85).

10 Prefácio à primeira edição: “Em suas visões básicas da presente investigação psicológica do estilo é uma sequência do meu livro anterior, Abstraction and empathy.”

Seguindo Worringer, Deleuze revela definitivamente uma inclinação anticlássica, e demonstra uma preferência pela linha do norte que cresce através de iteração infinita. Movido pelo princípio da proliferação infinita, a linha segue modelo dos fluídos, não dos sólidos: “A linha pictural na pintura gótica é completamente diferente, como é sua geometria e figura. Para começar, essa linha é decorativa; ela jaz na superfície, porém é uma decoração material que, no entanto, não define a forma. É uma geometria… ao serviço de problemas ou ‘acidentes’, ablação, adjunção, projeção, intersecção. É então uma linha que nunca cessa de mudar de direção, que está quebrada, dividida, desviada, virada ao seu avesso, enrolada ou estendida além de seus limites naturais, evanescendo em uma “convulsão desordenada” (DELEUZE, 2003, p. 40-41). Potencialmente “inorgânica”, a linha é colocada em movimento pela mobilidade mecânica, cuja vitalidade potente e redundância também são encontradas na arte bárbara até o gótico. O livro de Worringer descreveu assaz precisamente a linha gótica da vida não-orgânica, que a melodia infinita da linha do norte ofereceu uma base precisa para a linha cinética de Deleuze (SAUVAGNARGUES, 2006, p. 234). A partir de A Thousand Plateaus (“Mil Platôs”) e The Logic of Sensation (“Lógica das Sensações”) até What is philosophy? (“O que é Filosofia?”), a linha boreal do norte será usada por Deleuze (e Guattari) para enquadrar problemas, como por exemplo, o orgânico e o não-orgânico e também a mapear questões teóricas tais como as dos espaços lisos e a dos estriados, o nômade e o sedentário, entre outros. No The Fold “A Dobradura (1993, p. 14) de Deleuze, a própria mutação em uma característica barroca, a linha nomádica será definida como a linha-transformatória do ponto, que se revela em uma trajetória. Como resultado, linhas nomádicas ocupam grandes organizações giracionais, sustentam espaços topológicos lisos e tornam possível a velocidade de proliferação que expande para além do quadro. O objetivo da arte é desviar força na matéria. A que diferencia a linha nomádica, sendo da variedade gótica do norte ou do tipo barroca, é que ela personifica velocidade e fluidez, enquanto captura as forças intensas em matérias novas.

Quais são as consequências da arquitetura atual? No momento, através de ferramentas personalizadas de informação, parece ser imperativo incorporar elementos intensivos na construção virtual. Tal abordagem experimental procura definir soluções de design em resposta a uma ampla gama de parâmetros ambientais e estruturais. Durante o processo, elementos da engenharia estrutural, tais como a distribuição de pressão e todos os dados referentes ao suporte de cargas são levados em consideração, de acordo com critérios de adequação, antes de serem selecionados pelo designer em termos de sua aptidão estética. Tecnologias digitais atuais específicas, tais como programa de otimização estocástica, são baseadas em um modelo de custo benefício analisado através de um processo iterativo. Uma vez estabelecida a condição fundamental, o programa executa múltiplas iterações e então as analisa a fim de determinar a melhor solução. O design inicial é baseado em parâmetros fornecidos, e então é computado pela aplicação, permitindo que uma solução otimizada seja determinada (SHEA, 2004, p. 89-101; LEUPPI; SHEA, 2008, p. 28-30). Tal modo oferece a possibilidade de integrar a especialidade de designers e engenheiros em uma única plataforma computacional. Informação que exige a concretização formal da arquitetura está incorporada para negociar entre a forma e a matéria, ou mais precisamente, entre forças e materiais. Tais procedimentos incorporados são parecidos com a “modulação” de Simondon. Se estruturas arquiteturais evoluídas são para desfrutar o mesmo nível de produtividade combinatória quanto às biológicas, elas devem ser inicializadas por um diagrama adequado, como uma construção “abstrata” ou virtual (TEYSSOT, 2011). Neste ponto, o design parte das práticas convencionais, envolvendo um complexo de forças das quais deve-se traçar os diagramas, sejam energéticos, sistêmicos ou topológicos.

Referências

BANHAM, R. The new brutalism. The Architectural Review, n.118, p. 354-361, dez. 1955.

BOULEZ, P. Boulez on music today. Traduzido por Susan Bradshaw e Richard Rodney Bennett. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971.

COLONNA, F. Ruyer. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2007.

DALCQ, A. Form and modern embryology. In: WHYTE, L. L. Aspects of form: a symposium on form in nature and art. Londres: Lund Humphries, 1951.

DALCQ, A. L’œuf et son dynamisme organisateur. Paris: Albin Michel, 1941.

DEFERT, D. ’Hétérotopie’: tribulations d’un concept entre Venise, Berlin et Los Angeles. In: FOUCAULT, M. Le corps utopique: suivi de Les Hétérotopies. Posfácio por Daniel Defert. Paris: Lignes, 2009, p. 36-61.

DE LANDA, M. Deleuze and the Use the Genetic Algorithm in Architecture. Architectural Design, v.72, n.1, p. 9-12, jan. 2002.

DELEUZE, G. Difference and repetition. Traduzido por Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

DELEUZE, G. Foucault. Traduzido por Seán Hand. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

DELEUZE, G. Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation. Traduzido por Daniel W. Smith. Londres/Nova Iorque: Continuum, 2003.

DELEUZE, G. On Gilbert Simondon. In: Desert islands and other texts, 1953–1974. Nova Iorque: Semiotext(e), 2004, p. 86-89.

DELEUZE, G. The logic of sense. Traduzido por Mark Lester. Nova Iorque: Columbia University Press, 1990.

DELEUZE, G. The fold: Leibniz and the baroque. Traduzido por Tom Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

DELEUZE, G. Two regimes of madness: texts and interviews 1975-1995. Traduzido por Ames Hodges e Mike Taormina. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2006. 1a ed. 1978.

DELEUZE, G.; GUATTARI, F. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Traduzido por Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

DELEUZE, G.; GUATTARI, F. Nomadology: the war machine. Traduzido por Brian Massumi. Nova Iorque: Semiotext(e), 1986.

DELEUZE, G.; GUATTARI, F. What is philosophy? Traduzido por Hugh Tomlinson e Graham Burchell. Nova Iorque: Columbia University Press, 1994.

FRANZ, E. et al. (Eds.). Freiheit der Linie: von Obrist und dem Jugendstil zu Marc, Klee und Kirchner. Bönen: Kettler, 2007.

GARCIA, M. (Ed.). The diagrams of architecture: AD reader. Chichester: Wiley, 2010.

GUALANDI, A. La renaissance des philosophies de la nature et la question de l’humain. In: MANIGLIER, P. (Ed.). Le moment philosophique des années 1960 en France. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 2011.

JOEOFTHESTARS. 2 thoughts on “Translation: Raymond Ruyer and the genesis of living forms”. Fractal Ontology, [blog] 29 September 2007. Disponível em: <http://fractalontology.wordpress.com/2007/09/22/raymond-ruyer-and-the-genesis-of-living-forms-knowledge-and-structure/#comments >.

LEUPPI, J.; SHEA, K. The hylomorphic project. The ARUP Journal, jan. 2008, Londres, p. 28-30.

PROCHIANTZ, A. Géométries du vivant. Paris: Fayard, 2008.

RUYER, R. La genèse des formes vivantes. Paris: Flammarion, 1958.

SAUVAGNARGUES, A. Deleuze: l’empirisme transcendantal. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2009.

SAUVAGNARGUES, A. Deleuze et l’art. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 2006.

SHEA, K. Directed randomness. In: LEECH, N.; TURNBULL, D.; WILLIAMS, C. (Eds.). Digital tectonics. Chichester/Hoboken: Wiley-Academy, 2004.

SIMONDON, G. Being and technology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

SIMONDON, G. L’Individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information. Grenoble: Millon, 2005.

SIMONDON, G.. The genesis of the individual. In: CRAY, J.; KWINTER S. (Eds.). Incorporations. Nova Iorque: Zone Books, 1992.

TEYSSOT, G. Diagrammes machiniques. Renversions, Revue transdisciplinaire, sous la responsabilité de Véronique Fabbri et Laura Aubert, revue en ligne, n.1, 2011. Disponível em: <http://renversions.com/?p=51>.

TEYSSOT, G.; BERNIER-LAVIGNE, S. Forme et information: chronique de l’architecture numérique. In: GUIHEUX, A. (Dir.). Action architecture. Paris: Éditions de la Villette, 2011, p. 49-87.

THOMPSON, D. W. On growth and form. Cambridge: The University Press, 1944. 1a ed. 1917.

THOMPSON, D. W. On growth and form. Cambridge/Nova Iorque: University Press/Macmillan, 1942. 1a ed. 1917.

UEXKÜLL, J. A foray into the worlds of animals and humans: with a theory of meaning. Traduzido por Joseph D. O‘Neill. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. 1a ed. 1921.

WORRINGER, W. Abstraction and empathy: a contribution to the psychology of style. Traduzido por Michael Bullock. Nova Iorque: International Universities Press, 1963. 1a ed. 1907.

WORRINGER, W. Form in Gothic. Traduzido por Herbert Read. Londres: Putnam, 1927. 1a ed. 1911.

WORRINGER, W. L'Art gothique. Traduzido por D. Decourdemanche. Paris: Gallimard, 1967.

The Diagram as Abstract Machine

Georges Teyssot is Architect and researcher, lives in Canada. Presently, he is Professor at Laval University’s School of Architecture in Quebec. His research and his teaching discuss the invention of spatial, architectural and technological devices related to habitations in Western industrial and post-industrial societies.

How to quote this text: Teyssot, G., 2012. The Diagram as Abstract Machine. V!RUS, n. 7. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=3&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

Originally published in Georges Teyssot, “The Diagram as Abstract Machine”, in Diagram, Odile Decq, with Sony Devabhaktuni, eds., Paris, ESA (École Spéciale d’Architecture), forthcoming. The V!RUS journal gratefully acknowledges for the permission to republish here this article.

Abstract

Whether graph or chart, the architectural diagram is today an ubiquitous presence. As graphic inscription of abstraction in space, since the 1990s, the notion of diagram has been so much extended that now it nearly encompasses every aspect of design. To think of the diagram as an architecture of ideas (or, more classically, the idea of architecture) means to be still ensconced in some sort of platonic conceptions (Garcia, 2010). To avoid this trap, a first step would be to turn to Gilles Deleuze’s notion of the diagram as an abstract map, and to show how the model acquires its meaning, specifically when confronted with biological paradigms. Such understanding may lead to a better comprehension of the present algorithmic nature of diagrams. These scripted procedures refer to form, or, more precisely, to processes of morphogenesis. Their aim is to enhance a modulation between natural components, physical elements, and architectural design. A range of practices (or protocols) based on adaptable (customable) software, capable of producing changing modalities of a structural topology driven by performance, are currently available (Teyssot and Bernier-Lavigne, 2011). For instance, addressing the issue of the use of genetic algorithm in design, Manuel De Landa, inspired by Deleuze’s work, has proposed to introduce three theoretical levels of complexity: to think in terms of population (not the individual); to think in terms of differences of intensity (thermodynamic and entropic); lastly, to think in terms of topology (De Landa, 2002). The question addressed here will be therefore to know if (and how) the diagram is able to topologise the various fields of design1

Keywords: Diagram, design, digital media

Figure 01: “Michel Foucault’s Diagram and the Topology of the Fold” (Deleuze, 1988, p.120).

Morphogenesis

As Deleuze writes in Difference and Repetition (1994 [1968]), we live in a world dominated, by “a completely other distribution which must be called nomadic, a nomad nomos, without property, enclosure or measure” (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.36). The problem today is no longer the distribution of things and division of persons in sedentary spaces, “but rather a division among those who distribute themselves in an open space – a space which is unlimited, or at least without precise limits. […] To fill a space, to be distributed within it, is very different from distributing the space” (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.36). The leap from sedentary structures of representation to nomadic distribution, brings unsettling difficulties, transcending all limits, and deploying “an errant and even ‘delirious’ distribution” (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.37). Sedentary distributions, good sense, and common sense, are all based upon a synthesis of time, which has been determined as that of habit (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.225). On the other hand, nomadic structures lead to “mad repartitions …, mad distribution – instantaneous, nomadic distribution, crowned anarchy or difference” (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.224). Such is the state that physics described in thermodynamics, from Sadi Carnot to Rudolf Clausius and Ludwig Boltzmann (whose equation described the diffusion of gas particles on a statistical method): that is, entropy (Deleuze, 1994 [1968], p.225-229).

For Deleuze, it is necessary to recognize the primacy of multiple forces upon the form. In Difference and Repetition, he identifies this link between forces and forms as the two vectors of difference, using Henri Bergson and Gilbert Simondon as sources (Sauvagnargues, 2006, pp.88-89). For Simondon, the individuation of the crystal is the physical formation obtained by a difference in potential. This difference is the entropic arrow between tension and matter (as in a crystal) (Deleuze, 2004, pp.86-89). Deleuze translates this differentiation in terms of oscillation, a simultaneous vibration between the actual and the virtual, which are coexistent. Overcoming Bergson’s opposition between matter and duration, he transposes the arrow of intensity into a model of the coexistence of the virtual and the actual (Deleuze, 1994, pp.208-209). Both states are real, but the actual characterizes the completed individual, such as the materialized crystal, while the virtual refers to the problematic field of the pre-individual, when the intensive differentiation is not yet actualized. To illustrate this, Deleuze, following Simondon, uses the model of an egg, the paradigm of an intensive body, literally a body without organs, because it is a body going through phases of differentiation (Sauvagnargues, 2006, p.90).

Actualization occurs in things through a process of differentiation. Embryology shows that the division of an egg into parts is secondary in relation to more significant morphogenetic movements. Deleuze describes the kinematics of an egg, going through its various processes. (Deleuze, 1994, p.214). The differentiation of species and parts presupposes a whole set of spatio-temporal dynamics: “The entire world is an egg” (Deleuze, 1994, p.216). However, if the world is an egg, then the egg itself is a theater: a stage with actors, spaces, and ideas, and where a spatial drama is played. To substantiate this conclusion, Deleuze employs multiple sources, including Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s thesis on the kinetics of the fold; and Karl von Baër’s hypothesis on morphogenetic movements, including the stretching of cellular layers, invagination by folding, and the orientation and axis of movement, all to be found in the kinematics of the egg (Deleuze, 1994, p.214). In addition, Deleuze mentions Charles Manning Child’s gradient theory, which offered a framework for thinking about formal arrangement, and Paul Weiss’s paradigm of amphibian gastrulation, presented in his 1939 book Principles of Development, which elucidates how morphogenetic processes were capable of shaping form (Deleuze, 1994, p.250).

In philosophy, the main source was the work of Raymond Ruyer, who, inspired by Jakob von Uexküll’s etiology (2010 [1921]), had elaborated a philosophy of differentiation already in 1939. For Ruyer, in every domain, form is endowed with a proper rhythm. In his 1958 book, The Genesis of Living Forms, Ruyer (1958, p.140) discusses the spatio-temporal dynamism in cellular migration and makes a distinction between morphology and morphogenesis (Sauvagnargues, 2006, p.173, p.185): “Morphology, the study of forms and their arrangements, […] does not present any fundamental difficulty”, because it relies on vision and description, while morphogenesis, “presents […] the maximum of difficulty and mystery” (Joeofthestars, 2007). If Deleuze (1994, p.216, p.330) acquired ideas about spatial dramatization and the mystery of differentiation from Ruyer’s opus, it is not clear whether the two philosophers agreed that the virtual did not disappear once individuation (and differentiation) were completed2 . For Deleuze, form is not what remains of a physical action, nor is it the result of a depleted force: it is the outcome of a provisional state of equilibrium between forces (Deleuze, 1994, pp.222-223, pp.228-229, pp.240-241; Sauvagnargues, 2006, p.90).

As previously indicated, in Difference and Repetition, Deleuze attempted therefore to draw a theory of difference, in part based on biological differentiation, giving a new meaning to the ancient mythologies of the world egg, beginning with Anaximander’s cosmic egg, while he also provided a renewed interpretation of William Harvey’s 1651 biological dictum ex ovo omnia (“everything comes from the egg”):

‘In order to plumb the intensive depths or the spatium of an egg, […] the potentials and potentialities must be multiplied. The world is an egg. […] We think that difference of intensity, as this is implicated in the egg, expresses first the differential relations or virtual matter to be organized’ (Deleuze, 1994, pp.250-251).

Moreover, spanning a bridge between their theories, Deleuze relied also on Belgian biologist Albert Dalcq’s morphogenetic embryology (Dalcq, 1941), in addition to Simondon’s theory of individuation. Dalcq’s epigenesis offered a model for the differentiation modus operandi, which was at the heart of Deleuze’s thesis. The popularity of Dalcq’s work, in the 1950s among artists and architects, was equal to that of D’Arcy W. Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1944 [1917]). More a treaty on morphology than a morphogenetic theory, D’Arcy Thompson’s volume argued that evolution had been overemphasized as the fundamental determinant of the forms of living beings, and proposed mechanical processes of transformation as equally important in the shaping of life (Thompson, 1917).

It is noteworthy that Albert Dalcq’s book on embryology was the primary source on epigenesis, as much for the designers behind the exhibition, “On Growth and Form,” held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1951, the title of which was inspired by the new edition of D’Arcy Thompson, On Growth and Form (1944), as for Gilles Deleuze3. Read through the glasses of the philosophies of Spinoza, Leibniz and Bergson, Simondon’s theory of individuation helped to identify the egg as a vast metaphor of the world. If Deleuze’s philosophy of nature could anticipate the science of his time, it is because he succeeded in identifying the contemporary metaphors that buttressed his conceptualizations, the paradigmatic shifts that were enacted, together with the significant epistemic breakthroughs. Positioned (as he was) in opposition to the overcoded trends of Structuralism, and, at the same time, implicitly contrasting hard-nosed geneticists that read only in codes, Deleuze introduced the egg’s metaphor that helped rearticulate the connection between the symbolical and the vital. Without entering the contemporary debate on biology and genetics, it seems that Deleuze theory was not far from the position sustained by the American Stephen Jay Gould’s 1977 Ontogeny and Phylogeny (Gualandi, 2011, pp.59-72).

Deleuze (2003, p.41) will often use the embryo’s model to expose the inorganic vitality of tissues, not yet stabilized in the shape of an organ, capable of multiple transformations: “[…] the body without organs does not lack of organs, it simply lacks the organism, that is, the particular organization of organs. The body without organs is thus defined by an indeterminate organ, whereas the organism is defined by determinate organs”. In Deleuze’s The Logic of Sense (1990 [1969], pp.88-342), everything will collapse around the paradigm of Antonin Artaud, whose poetical, schizoid delirium called for a body beyond its organic determination. For Artaud, the completed organism felt like a form that imprisons the body (Sauvagnargues, 2006, pp.87-88). During the 1970s, Deleuze and Guattari will never ask anybody to deprive himself of its organs, but to replace the notion of a full-grown organ by the metamorphic and polymorphic conception of an immature organ while it differentiates. Deleuze’s bio-philosophy illustrates the virtuality of intensive forces, while they operate before the organic form is achieved and constituted. What Deleuze and Guattari proposed was to consider the virtual axes of informal forces (Sauvagnargues, 2006, p.90).

Resisting the Neo-Platonism of types and models, Deleuze believed that what exists in the world’s immanence is not the copy of a model that would constitute the ideal mold of real individuals; that what is real is not the one and unique, or transcendental, but the singularities and the differences. The ideal mold is similar to the ideal type in art history, art, or design. Simondon elaborated a precise criticism of the idea of a mold by introducing the concept of modulation. In modulation, Simondon writes “there is never time to turn something out, to remove it from the mold” (Simondon, 1964, pp.41-42 cited in Deleuze, 2003, p.108). To proceed to such a demolding (Fr., démoulage) is unnecessary, “because the circulation of the support of energy is equivalent to a permanent turning out; a modulator is a continuous, temporal mold” (Simondon, 1964, pp.41-42 cited in Deleuze, 2003, p.165). While molding leads to a permanent state of things, modulation introduces the factor of time: “To mold is to modulate in a definitive manner, to modulate is to mold in a continuous and perpetually variable manner” (Simondon, 1964, pp.41-42 cited in Deleuze, 2003, p.165). Throughout his work, Deleuze also recommends altering the idea of molding by introducing that of modulation. In 1978, for example, he affirmed (Deleuze, 2006 [1978], p.159): “Every direction leads us, I believe, to stop thinking in terms of substance-form”. Taking up Simondon’s criticism of hylemorphism, opposing inert matter to active form, he proposed to substitute it with a process of modulation, in which the form-giving operation would be conceived as the coupling of forces and materials. While this theory helped Deleuze to escape from resemblance, opposing the idea that a model needs to be copied, he reached a new definition of artistic activities, as the capture of intensive forces by new materials: “The material-force couple replaces the matter-form couple” (Deleuze, 2006 [1978], p.160). Contemporary science shows that genotype is not a mold that determines the individual in a univocal mode. Between the genotype and the phenotype, a process of development inserts itself, where the temporal variable plays a role as important as the spatial and topological variables4. The structure actualizes itself through a process of development, introducing factors of stochastic and temporal variability that singularize the individual prototype. As should be clear, Deleuze’s thinking was not based on vague metaphors or rhetorical tropes (Gualandi, 2011, pp.64-65). If one can speak of metaphors, it is in the noblest sense, since they were able to grasp theoretical issues even in domains that had not yet been clearly perceived by science itself.

Intensive Diagram

The body without organs conveys the notion of matter in a not-yet-formed state, of a body not-yet-represented, or an unrepresentable body in its schizophrenic version. Overcoming organized form, one is introduced to matter as a receptacle of forces. Beyond the matter-form opposition, beyond organized form, there is matter as a non-formal mix of forces and materials. More than a metaphor, the body without organs refers to the notion of machine and of diagram, developed, in parallel, in the work of Michel Foucault, of which Deleuze is a keen interpreter. The diagram is a map, which is coexistent with the whole society, and forms an “abstract machine” (Deleuze, 1988, p.34). Dealing with fluxes, fluids, functions, it churns up matter, form, energy, networks. Every diagram is a “different machine” (Deleuze, 1988, p.34). Such a machine is concerned with the representation of relation of forces, belonging to a stratified formation, and it doubles the stratification (for examples, the strata of history and of society). This intensive diagram should not be conceived as a permanent structure, nor thought as a pre-existing form, but rather as a virtual problem -- that is, a complex of forces (Sauvagnargues, 2009, p.422). One could define a Pastoral diagram, a Greek one, a Roman one, or a Feudal one (Deleuze, 1988, p.85). Or even a Baroque diagram. The diagram, however, is not historical, but belongs to a phenomenon of becoming: “it doubles history with a sense of continual becoming (devenir)”5 (Deleuze, 1988, p.35). As Deleuze (1988, p.86) remarks in nearly all of his books: “There is […] a becoming of forces which remains distinct from the history of forms […] It is an outside which is farther away than any external world and even any form of exteriority”6. Indissociable from its actualization, the diagram is used to inject some becoming in every point of the stratified reality (Sauvagnargues, 2009, p.423). The concept of the diagram as an abstract machine helps us to understand the biological and machine-like reality of so many strata, such as institutions, technologies, and apparatuses; including heterotopias (Defert, 2009, pp.36-61). Moreover, it can help characterize works of art, including Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Artaud’s schizo-poetics, or Francis Bacon’s exhibition of the flesh. The diagram offers the tools to map art’s phyla and genus, its phylogenesis as much as its heterogenesis.

Subsequently, one reaches what Deleuze defined as “Foucault’s Diagram”, a sort of diagram of a diagram, if not a master diagram, divided by a line between an outside and an inside, the latter being made of strategic zones and constructed of layers or strata, in which texts and images from the past are archived. In the scheme drawn by Deleuze, there is a gigantic fold, which indicates the position of oneself in relation to the task of producing new modes of subjectification. This way, three agencies (or instances) are being held together by a fold, which acts as topological operator (Deleuze, 1988, p.120). Outside and inside are inverted. Far and near converge. According to Deleuze, for Foucault, Descartes’s, “I think, therefore I am,” should be replaced by the renewed formulation, I think, therefore I fold: “The general topology of thought … ends up in the folding of the outside into the inside” (Deleuze, 1988, p.118). The urgent prerequisite is to construct an inside-space that is completely co-present with the outside-space, “on the line of the fold” (Deleuze, 1988, p.118). Independent of distance and within the limits of any vital, lived space, “Every inside-space is topologically in contact with the outside-space . . . and this carnal or vital topology, far from showing up in space, frees a sense of time that fits the past into the inside, brings about the future in the outside, and brings the two into confrontation at the limit of the living present” (Deleuze, 1988, p.119). As Deleuze states, this is how Foucault grasps the doubling, or the fold: “If the inside is constituted by the folding of the outside, between them there is a topological relation: the relation to oneself is homologous to the relation with the outside and the two are in contact, through the intermediary of the strata which are relatively external environments (and therefore relatively internal)” (Deleuze, 1988, p.119).

It is possible to immerse oneself in an archive made of visible forms and articulate bodies; to cross surfaces, graphs, charts, and curves; and to follow fissures in order to reach an interior of the world. But at the same time it is also necessary to climb above the strata in order to reach an outside, an atmospheric element (Deleuze, 1988, p.121): “The informal outside is a battle, a turbulent, stormy zone where particular points and the relations of forces between these points are tossed about. Strata merely collected and solidified the visual dust and the sonic echo of the battle raging above them”. Nevertheless, for Deleuze, “up above, the particular features have no form and are neither bodies nor speaking persons” (Deleuze, 1988, p.121). For both Foucault and Deleuze, the diagram is a “micro-physics” (Deleuze, 1988, p.121)7. However, read by Deleuze, Foucault’s diagram lives a new life. Rising above the static opposition between form and matter, situating oneself in an energetic dimension, it becomes possible to think materiality in terms of movement and forces, and introduce a potential of deformation active in the material.

As Deleuze wrote, to have something stand up “does not mean having a top and a bottom or being upright” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p.164). One can draw “a monument, but one that may be contained in a few marks or a few lines, like a poem by Emily Dickinson” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p.165). Following this remark, it would be possible to attempt to write a brief history of the line, say, from William Hogarth’s “line of beauty” (1753) to Henry van de Velde’s line as a force, to Paul Klee’s inflected lines (Franz, et al., 2007), and up to the topology of splines used in 2-D/3-D modeling. Already in the 1950s, while opposing the Platonism of Colin Rowe, Reyner Banham advocated a topological architecture (Banham, 1955, pp.354-361). Suddenly, what formed the basis of the traditional categories of space sees its meaning transformed, by transmutation, into a topological contact surface.

Fluid Spaces

Today, a question remains: how have topological concepts been introduced in architecture? Perhaps, a particularly refined topology is needed to describe the formation of spirals and vortices, or nomadic, smooth spaces, which are formed by haptic relations. As Deleuze and Guattari put forward, haecceities are to be found along intersecting lines (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p.263): “Climate, wind, season, hour … Haecceity, fog, glare. A haecceity has neither beginning nor end, origin nor destination; it is always in the middle; it is not made of points, only lines. It is a rhizome”. From there, the well-known distinction between a nomad, “smooth” space, as opposed to a sedentary, “striated” condition will be developed by Deleuze and Guattari (1987, p.382): “… There is an extraordinary fine topology that relies not on points or objects, but on hacceities, on sets of relations (winds, undulations of snow or sand, the song of the sand or the creaking of ice, the tactile qualities of both); it is a tactile space, or rather ‘haptic’, a sonorous much more than a visual space. … The variability, the polyvocality of directions, is an essential feature of smooth spaces of the rhizome type … The nomad, nomad space, is localized and not delimited. What is both limited and limiting is striated space”. Deleuze, inspired as always by Simondon, revived the concept of haecceity developed in Duns Scott’s scholastic philosophy. Haecceity stems from the Latin haecceitas, meaning “this-ness”, from Haec, “this thing”.

As it were, haecceity, or individuation, helped to explain the existence of particular individuals. With Scott, such a conception opposed to the Aristotelian theory of hylemorphism, which held that any individual being was the creation of dynamic form applied on indistinct matter, as if nature’s creations were the outcome of a sculptor molding clay. Derived from the Greek, hylemorphism (or hylomorphism) referred to the imposition of an active form (morphe) onto passive matter (hyle). Scott refuted this theory, rejecting the suggestion that determinate, individual beings could be the output of indeterminate matter. As previously mentioned, Simondon will criticize hylemorphism for its universalistic, static, and frozen approach, and instead define individuation as an ongoing process that consists precisely of a modulation between form and information (Simondon, 2005, p.225)8. For both Simondon and Deleuze, one should consider carefully the specific processes of becoming-individual, encompassing the singularity in each being9 (Simondon, 1992, pp.297–319).

For Deleuze, haecceity is not limited to any question of scale (small or large), but has a peculiar consistency which connects it physically to phenomenon, such as vapor, haze, mist or cloud situations that blur any defined limit or border. Haecceity constellates, forming groups, clusters and flocks. Inspired by Pierre Boulez’s theory of music, Deleuze and Guattari write: “the model is a vortical one; it operates in an open space throughout which things-flows are distributed, rather than plotting out closed space for linear and solid things. It is the difference between a smooth (vectorial, projective or topological) space and a striated (metric) space” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1986, p.18 and p.125)10. In the first case, space is occupied without being measured, while in the second space is measured in order to be occupied, a distinction taken from Boulez. Like a flock, smooth, “nomad” art circulates in an open and connected space, as opposed to a striated, geometrical art, centered and self-contained. It is actually two different usages of measure: smooth space relies on a “numbering number [which] is rhythmic, not harmonic. It is not related to cadence or [an external] measure” (Deleuze and Guatarri, 1986, p.67), while striated space is based on a homogeneous measure, marking out the surface in squares and rearranging everything in order. This observation helps tell apart an abstract line, unfolding its smooth space from a set of twists and torsions -- that is, from a striated space subject to norms and orthogonally squared by rules (Sauvagnargues, 2006, pp.232-234).

Deleuze had read Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy (1963 [1907]). He was convinced that Worringer had given fundamental prominence to the abstract or primitivistic line “seeing it as the very beginning of art or the first expression of artistic will. Art as abstract machine” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p.496). Pursuing the investigation, Worringer published Form in Gothic (1927 [1911])11, a psychological investigation of style, presented by him as a sequel to Abstraction and Empathy. Deleuze read also Form in Gothic (Worringer, 1927 [1911]) and repeatedly quoted it from the French translations (Worringer, 1967 [1941]): “From the depths of time there comes to us what Worringer called the abstract and infinite northern line, the line of the universe that forms ribbons, strips, wheels, and turbines, an entire ‘vitalized geometry’, rising to the intuition of mechanical forces, constituting a powerful nonorganic life” (Worringer, 1927 [1911], pp.41-42 cited in Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p.182). What differentiates the nomadic line from classical ornamentation are the paradigms of speed, of proliferation, and of accelerated transformation, which all are characteristics of smooth space. In such a space, the line is free from representational purposes, as well as untied from the laws of metrics; as such, it is liberated from classical symmetry, from the repetition of the motif, and from the striations of rational coordinates. All these characteristics belong to Renaissance architecture, which make it a stable, classical and “organic” art.

1 Topology, a branch of mathematics, studies the property of objects that are preserved through continuous deformation, such as bending, twisting or stretching. It can be used to study the inherent connectivity of objects in any dimensional space, while ignoring their detailed form or shape. Topology studies the characteristics of figures, or topological surfaces, such as the Klein bottle, the Möbius strip, or the torus.

2See Colonna, 2007.

3 See Albert Dalcq Form and Modern Embryology (1951). Published in collaboration with the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) to coincide with the exhibition “Growth and Form” (London, Summer 1951), the title of which was inspired by the new edition of D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson On Growth and Form (1944).

4 See Prochiantz, 2008.

5 Not “evolution”, but devenir, “becoming”, in the original text.

6 Translation edited by us.

7 And not “micro-politics”, as translated.

8 See the new edition of the main doctoral thesis of Gilbert Simondon (1957) that combines L’Individu et sa genèse physico-biologique (published in 1964), that Deleuze read, and L’Individuation psychique et collective (published in 1989).

9 See also Simondon, 2012. The present paper was written before such collection of essays was available.

10 The authors cite Boulez on Music Today (Boulez, 1971, p.85).

11 Pref. to the 1st edition: “In its basic views the present psychological investigation of style is a sequel to my earlier book, Abstraction and empathy.”

Following Worringer, Deleuze reveals definitively an anticlassical bend, and shows a preference for the northern line that swells by indefinite iteration. Moved by a principle of internal proliferation, the line follows the model of fluids, not solids: “The pictorial line in Gothic painting is completely different, as is its geometry and figure. First of all, this line is decorative; it lies at the surface, but it is a material decoration that does not outline a form. It is a geometry … in the service of ‘problems’ or ‘accidents,’ ablation, adjunction, projection, intersection. It is thus a line that never ceases to change direction, that is broken, split, diverted, turned in on itself, coiled up, or even extended beyond its natural limits, dying away in a ‘disordered convulsion’” (Deleuze, 2003, pp.40-41). Potently “inorganic”, the line is set in motion by a mechanical mobility, whose redundancy and potent vitality is to be found in barbaric arts up to the Gothic. Worringer’s book described so accurately the Gothic line of non-organic life that the infinite melody of the northern line offered a precise basis for Deleuze’s kinetic line (Sauvagnargues, 2006, p.234). From A Thousand Plateaus and The Logic of Sensation, to What is philosophy?, the boreal-northern line will be used by Deleuze (and Guattari) to frame problems, for example, the organic and the non-organic, and also to map theoretical issues such as the smooth and the striated spaces, the nomad and the sedentary, and so forth. In Deleuze’s The Fold (1993, p.14), mutating itself into a baroque feature, the nomadic line will be defined as the becoming-line of the point, which unfolds in a trajectory. As an outcome, nomadic lines take on great vortical organizations, prop up smooth topological spaces, and allow for a speed of proliferation that expands beyond the frame. The aim of art is to divert force into matter. What sets apart the nomadic line, whether from the northern-gothic variety or from the baroque type, is that it embodies speed and fluidity, while it captures intense forces in new materials.

What are the consequences for today’s architecture? At present, through customized informational engines, it seems imperative to incorporate intensive elements into the virtual building. Such an experimental approach aims at defining design solutions in response to a wide range of structural and environmental parameters. During the process, elements of structural engineering, such as distribution of stresses and the entire load bearing data, are taken into account, according to fitness criteria, prior to being selected by the designer in terms of their aesthetic aptness. Current specific digital technologies, such as stochastic optimization software, are based on a cost efficiency model analyzed through an iterative process. Once a base condition is established, the software runs multiple iterations and then analyzes them to determine a best solution. The initial design is based on given parameters, and then is computed by the application, allowing an optimized solution to be determined (Shea, 2004, pp.89-101; Leuppi and Shea, 2008, pp.28-30). Such a mode offers the possibility to integrate the expertise of designers and engineers on a unique computational platform. Information, which determines the formal concretization of architecture, is scripted to negotiate between form and matter, or, more precisely, between forces and materials. Such scripted procedures are akin to Simondon’s “modulation”. If evolved architectural structures are to enjoy the same degree of combinatorial productivity as biological ones, they must be initialized by an adequate diagram, as an “abstract” or virtual building (Teyssot, 2011). At this point, the design departs from the conventional practices, engaging a complex of forces of which one must trace the diagrams, whether energetic, systemic, or topological.

References

Banham, R., 1955. The new brutalism, The Architectural Review 118, December, pp.354-361, quote 361.

Boulez, P., 1971. Boulez on Music Today. Translated by Susan Bradshaw and Richard Rodney Bennett. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Colonna, F., 2007. Ruyer. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Dalcq, A., 1941. L’œuf et son dynamisme organisateur. Paris: Albin Michel.

Dalcq, A., 1951. Form and modern embryology. In: L. L. Whyte. Aspects of form: a symposium on form in nature and art. London: Lund Humphries.

Defert, D., 2009. ’Hétérotopie’: tribulations d’un concept entre Venise, Berlin et Los Angeles. In: M. Foucault. Le corps utopique: suivi de Les Hétérotopies. Postface by Daniel Defert. Paris: Lignes, pp.36-61.

De Landa, M., 2002. Deleuze and the Use the Genetic Algorithm in Architecture, Architectural Design, Jan. 2002, 72(1), pp.9-12.

Deleuze, G., 1988. Foucault. Translated by Seán Hand. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., 1990. The logic of sense. Translated by Mark Lester. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G., 1993. The fold: Leibniz and the baroque. Translated by Tom Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., 1994. Difference and repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G., 2003. Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation. Translated by Daniel W. Smith. London/New York: Continuum.

Deleuze, G., 2004. On Gilbert Simondon. In: Desert islands and other texts, 1953–1974. New York: Semiotext(e), pp.86-89.

Deleuze, G., 2006. Two regimes of madness: texts and interviews 1975-1995. Translated by Ames Hodges and Mike Taormina. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e). 1st ed. 1978.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1986. Nomadology: the war machine. Translated by Brian Massumi. New York: Semiotext(e).

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1987. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1994. What is philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press.

Franz, E. et al. eds., 2007. Freiheit der Linie: von Obrist und dem Jugendstil zu Marc, Klee und Kirchner. Bönen: Kettler.

Garcia, M. ed., 2010. The diagrams of architecture: AD reader. Chichester: Wiley.

Gualandi, A., 2011. La renaissance des philosophies de la nature et la question de l’humain. In: P. Maniglier ed. Le moment philosophique des années 1960 en France. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Joeofthestars, 2007. 2 thoughts on “Translation: Raymond Ruyer and the genesis of living forms”. Fractal Ontology, [blog] 29 September. Available at: <http://fractalontology.wordpress.com/2007/09/22/raymond-ruyer-and-the-genesis-of-living-forms-knowledge-and-structure/#comments >.

Leuppi, J. and Shea, K., 2008. The hylomorphic project. The ARUP Journal, January issue, London, pp. 28-30.

Prochiantz, A., 2008. Géométries du vivant. Paris: Fayard.

Ruyer, R., 1958. La genèse des formes vivantes. Paris: Flammarion.

Sauvagnargues, A., 2006. Deleuze et l’art. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Sauvagnargues, A., 2009. Deleuze: l’empirisme transcendantal. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Shea, K., 2004. Directed randomness. In: N. Leech, D. Turnbull and C. Williams eds. Digital tectonics. Chichester/Hoboken: Wiley-Academy.

Simondon, G., 1992. The genesis of the individual. In: J. Crary and S. Kwinter eds. Incorporations. New York: Zone Books.

Simondon, G., 2005. L’Individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information. Grenoble: Millon.

Simondon, G., 2012. Being and technology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Teyssot, G., 2011. Diagrammes machiniques. Renversions, Revue transdisciplinaire, sous la responsabilité de Véronique Fabbri et Laura Aubert, revue en ligne, 1. Available at: <http://renversions.com/?p=51>.

Teyssot, G. and Bernier-Lavigne, S., 2011. Forme et information: chronique de l’architecture numérique. In: A. Guiheux dir., 2011. Action architecture. Paris: Éditions de la Villette, pp.49-87.

Thompson, D. W., 1944. On growth and form. Cambridge: The University Press. 1st ed. 1917.

Thompson, D. W., 1917. On growth and form. Cambridge/New York: University Press/Macmillan, 1942. 1st ed. 1917.

Thompson, D’Arcy Wentworth, 1917. On growth and form, Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Uexküll, Jakob von., 2010. A foray into the worlds of animals and humans: with a theory of meaning. Translated by Joseph D. O‘Neill. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1st ed. 1921.

Worringer, W., 1963. Abstraction and empathy: a contribution to the psychology of style. Translated by Michael Bullock. New York: International Universities Press. 1st ed. 1907.

Worringer, W., 1927. Form in Gothic. Translated by Herbert Read. London: Putnam. 1st ed. 1911.

Worringer, W., 1967. L'Art gothique. Translated by D. Decourdemanche. Paris: Gallimard.