Cuerpo y Performance en la era de las comunicaciones virtuales: El espacio del Cuerpo en el espacio del cuerpo

Santiago Cao es Lic. en Artes Visuales y complementó con estudios en la carrera de Psicología. Es profesor de Lenguaje Visual en el IUNA (Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte) en Buenos Aires.*

Como citar esse texto: Cao, S., 2012. Cuerpo y Performance en la era de las comunicaciones virtuales - El espacio del Cuerpo e el espacio del cuerpo.V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 7 [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2025.

Resumen

El “Ver” es un acto mucho más complejo que lo puramente fisiológico. Entran allí en juego, entre otras cuestiones, los saberes adquiridos y los heredados, que a modo de herramientas nos servirán para decodificar lo visto a fin de comprenderlo y asimilarlo. Y cuando hago esta distinción entre lo adquirido y lo heredado lo pienso en relación a que lo primero es fruto de la propia vivencia del sujeto que genera experiencia y por ende un personal modo de “Ver al mundo”, a diferencia de los saberes heredados (“Ver el mundo”) que son impuestos por la cultura que lo crió (¿o sería mejor decir que lo co-creó?). Pero “Ver el mundo” no es lo mismo que “Ver al mundo”. Para establecer esta distinción, hemos de desarrollar en este texto la premisa “Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer”, la cual nos será de utilidad para pensar luego que, si aquello que vemos no es lo que es sino lo que creemos que es, ¿qué sucede entonces con los dispositivos de representación visual de la “realidad” y con quienes ostentan el poder de difundirlos?. Pero las nuevas tecnologías como Internet y las telefonías celulares han generado un quiebre en este concepto, atravesando las nociones de contexto y paratexto, ampliando el acto creativo de “Ver” y generándose por ende nuevas realidades a partir de un mismo acontecimiento observado. Y el cuerpo en todo esto no quedará por fuera. Pensaremos que sucede en la Performance como disciplina artística, donde el cuerpo que tradicionalmente fue soporte de obra, ahora se enfrenta con estos nuevos modos de verlo y crearlo.

Palabras Claves: Cuerpo; performance; dispositivos de representación; comunicaciones virtuales; producción de realidad.

nota del título1

Una aproximación al Cuerpo

Si vamos a considerar el cuerpo como soporte de obra, primero deberíamos definir que es el “Cuerpo”; encontrar un punto en común, plantear una base desde donde pensar juntos. Pero aquello que llamamos cuerpo, ¿existe como tal?

Según la Gran Enciclopedia Rialp de Humanidades y Ciencia (1991):

‘El cuerpo es el conjunto de estructuras armónicamente integradas en una unidad morfológica y funcional que constituye el soporte físico de nuestra persona durante la vida, específicamente diferenciado en dos únicos tipos, masculino y femenino, según el carácter de nuestro propio sexo.’

206 huesos (sin contar las piezas dentarias), ligamentos, tendones, músculos y cartílagos. Venas, arterias y vasos capilares. Órganos como el riñón, hígado, pulmones, páncreas entre otros. Una cabeza, un tronco, dos brazos y dos piernas. Dos ojos, una nariz, una boca. Manos (dos), dedos (veinte). Piel. Uñas, cabellos. ¿Rubios, morochos, castaños, cobrizos, pelirrojos? ¿Orina? ¿Materia fecal?. Sangre. ¿Menstruación?. ¿Semen, Flujo vaginal? Pene o vagina según sea masculino o femenino. Un “cuerpo de hombre”. Un “cuerpo de mujer”. ¿Una mujer “atrapada” en un “cuerpo de hombre”? ¿Un hombre “atrapado” en un “cuerpo de mujer”?.

Un cuerpo vivo. Un cuerpo muerto. Un cuerpo en Buenos Aires. Un cuerpo en Francia. Un cuerpo en la India. Un cuerpo en la calle. Un cuerpo en el piso, en una avenida. Un cuerpo en una cama.

¿Qué es el “Cuerpo”? ¿Cuál es su espacio? ¿Cuáles sus límites?

Entonces, cuando hablamos de “Cuerpo”… ¿a qué nos estamos refiriendo?

Partamos de nuestro propio cuerpo. No tenemos conciencia de él si no es a través de nuestros sentidos y de la lectura o interpretación que hacemos de la información captada por ellos. Matlin y Foley (1996, p.554) estipulan que:

‘La sensación se refiere a experiencias inmediatas básicas, generadas por estímulos aislados simples, (en cambio) la percepción incluye la interpretación de esas sensaciones, dándoles significado y organización.’

Siendo que los sentidos son vías de incorporación de información, ¿podríamos pensar que nuestro cuerpo es una percepción?

Interoceptores, propioceptores y exteroceptores son los encargados de captar la información necesaria para dar cuenta de nuestro cuerpo. De manera tal que bastaría alguna lesión en alguno de los órganos receptores para que nuestra sensación, y por ende nuestra percepción del cuerpo, cambie, cambiando así nuestro esquema corporal.

‘El esquema corporal es entonces, la representación que el ser humano se forma mentalmente de su cuerpo, a través de una secuencia de percepciones y respuestas vivenciadas en la relación con el otro.’ (Fuentes-Martínez, 2006, p.2).

Pero nuestra conciencia de cuerpo, nuestro esquema corporal, no es siempre el mismo ni está presente desde nuestros primeros momentos de vida. Según la teoría psicoanalítica planteada por Freud (1979), la constitución del Yo es un proceso gradual que parte del No Yo al Yo. Un mal desarrollo del Yo derivaría en una distorsión del Esquema Corporal y por ende, de la noción del propio cuerpo.

Por su parte, el médico psiquiatra René Spitz (1996) dividió en 3 etapas el primer año de vida del niño, observando que en la primera de ellas, denominada “Pre-objetal o sin objeto” y que va de los 0 a 3 meses de edad, el recién nacido no logra diferenciar una cosa externa de su propio cuerpo. No puede experimentar algo separado de él. De esta manera, el pecho materno que provee su alimento sería percibido como una parte de sí mismo y no como un otro que lo alimenta.

Cuerpo - No cuerpo

Puedo definirlo más fácilmente por lo que no es que por lo que es. No es un sorete, aunque también podría llamar de Materia Fecal a la sustancia en la taza del inodoro que minutos antes estaba alojada en mi intestino grueso. Aunque prefiero el primer término ya que Materia Fecal aun conserva una reminiscencia con su origen.

¿Y la orina? ¿Y la sangre? ¿Son parte de mi cuerpo o solo están dentro de él? ¿Y si es algo que puedo perder o eliminar, aun así es mi cuerpo?

Y esta mano, que por (de)finición, (de)limitación, tiene cinco dedos, si perdiera alguno de ellos en un accidente, ¿seguiría siendo una mano?

Y ese dedo, ese pequeño despojo de carne y huesos yaciendo cercenado en el suelo o atrapado dentro de una máquina, ¿sería también mi cuerpo? ¿la parte por el todo?

Y si la mano no precisa de dedos para ser mano, ¿el todo por las partes?

*Para ver registros de sus trabajos pueden visitar <www.artistanoartista.com.ar/inicio.php> and <www.facebook.com/cao.santiago>.

1 Hemos de diferenciar al cuerpo, en tanto organismo biológico, del “Cuerpo” con mayúscula, entendiendo este último como un constructo aún más complejo que lo orgánico. El Cuerpo, que aloja la cultura donde está inmerso. Que aloja las expectativas de los demás. Que es moldeado por la mirada de los otros que, introyectados, se vuelven “Otro”. Este cuerpo que expandiéndose hacia los objetos que lo rodean se convierte en un Cuerpo aún más complejo. Y que en tanto Cuerpo, puede virtualizarse, recorrer grandes distancias sin moverse del lugar y -paradójicamente- perder su corporalidad sin perder su presencia.

Esa mano sin dedos, ese muñón al extremo de mi brazo, es cuerpo.

¿Y esos dedos sin mano?

Pareciera que las personas tuviéramos una relación esquizoide con nuestro propio cuerpo. Bastaría que una parte del mismo sea separada del resto para que ya no fuera más cuerpo. Y sin embargo, muchos de los objetos que nos rodean, lo exterior-no cuerpo es percibido como anexo corporal. Pongamos como ejemplo burdo a una persona conduciendo su automóvil por una avenida. Imaginémosla estacionándolo a un lado de la acera. Bajando del mismo. Cerrando con llave la puerta. Activando la alarma. Imaginemos que camina dos metros y recuerda que olvidó tomar su libro. Veámoslo girar su cuerpo en el preciso instante en que el auto estacionado delante embiste su propio carro quebrándole los vidrios de los faros. Imaginemos a este hombre frunciendo el ceño, entrecerrando los ojos, alzando los brazos al tiempo que se toma la cabeza con una mano. Imaginémoslo con gesto dolorido, gritarle al otro chofer ¡Me chocaste!

Preguntémonos ahora, lógicamente, como pudo haberlo chocado si él se encontraba a dos metros de distancia. Si el chocado fue su automóvil y no su cuerpo. ¿O habrá sido su cuerpo el chocado? Su cara de dolor y la frase gritada me hacen dudar de cualquier afirmación. Hay una relación de continuidad con algunos objetos contiguos a nosotros. Pareciera ser que la etapa “Pre-objetal o sin objeto” a la que hicimos referencia, continuara presente aun luego de los 3 meses de haber nacido. Parecería ser que aun de adultos nos costara diferenciar una cosa externa, de nuestro propio cuerpo. Como si el automóvil, en este ejemplo, fuera una analogía con el pecho materno descrito por Spitz (1996), un pecho que en tanto proveedor de alimento, es percibido por el niño como una parte de sí mismo y no como un otro que lo alimenta. Como un anexo corporal. Extrañamente… un cuerpo de metal, plástico y caucho, que al igual que nuestras heces, sus gases contaminantes no nos pertenecen.

¿Y si el Cuerpo no fuera un cuerpo sino nuestra percepción del propio cuerpo?

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1992, p.16), en su libro póstumo “Lo visible y lo invisible” planteaba que “Es verdad que el mundo es lo que vemos y que, con todo, precisamos aprender a verlo”.

El cuerpo es, según este filósofo, constituyente tanto de la apertura perceptiva al mundo como de la creación de ese mundo. Una condición permanente de la existencia.

Sin intención de profundizar en su planteo, utilicemos esta frase a modo de trampolín para “saltar” hacia otros conceptos que, “hilvanados”, nos permitan fundamentar la premisa inicial Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer.

‘El cuerpo —el “propio cuerpo”— no es un objeto. El cuerpo como objeto es, a lo sumo, el resultado de la inserción del organismo en el mundo del “en sí” (en el sentido de Sartre)’ (Ferrater-Mora, 1965, p.389).

¿Y si el mundo del “en sí”, el mundo de las cosas, fuera a su vez la resultante de la percepción de este organismo?

Espacio

A lo largo de la historia de Occidente, el debate sobre la cuestión del Espacio fue cambiando a medida que los paradigmas iban “cayendo” y dejando paso a los siguientes modos de pensar el mundo. De manera tal, podríamos plantear a grandes rasgos que la problemática del espacio se debatió en dos posiciones teóricas: quienes estudiaban el espacio en relación con un sujeto o una conciencia, y quienes consideraban el espacio en sí mismo. Hemos de adherir en este texto a la primera de estas posiciones.

Sin embargo no solo se ha tratado de pensar el espacio; también se ha buscado representarlo gráficamente de distintas manera a lo largo de dicha historia. Múltiples sistemas de representación se han empleado, entre ellos, la Perspectiva.

Esta palabra, de origen latín, que etimológicamente remite al verbo Perspicere, significa ver a través de (Mirar -spicere- a través de, o atentamente -per-). Interesante observar que una de sus derivaciones sea la palabra Perspicacia que, según la Real Academia Española (2001) significa:

1. f. Agudeza y penetración de la vista.

2. f. Penetración de ingenio o entendimiento

Seamos pues, perspicaces, y tratemos no solo de ver “a través de” la perspectiva sino también más allá de ella.

Hagamos primero una distinción al respecto del ver y el mirar. Ver es una función electromagnética donde -según la capacidad de cada órgano visual de captar y reaccionar ante la incidencia de las ondas luminosas sobre la retina- se proyectará a través del nervio óptico información al cerebro, el cual decodificará el estímulo construyendo una imagen mental del mismo. Los seres humanos, al igual que otros animales, poseemos la capacidad de enfocar los dos ojos sobre un mismo objeto permitiendo lo que se llama visión estereoscópica. Ese tipo de visión permite, entre otras cosas, captar la profundidad del campo visual. Pero no todos los órganos sensoriales son iguales en cada persona ni cada persona ve lo mismo dos veces. La incidencia de la luz sobre los objetos marcará una variación en la percepción de los mismos. Una lata de tomates observada en las primeras horas de la mañana de un día soleado no se verá igual que al mediodía. La luz en la segunda situación, será más clara que en la primera, y si tomamos en cuenta que la posición cenital del sol no proyectará sombras de la lata, podemos pensar en una más fácil captación de la misma. Y mucho más aun que si intentáramos verla en la obscuridad de la noche. Pero en el acto de “mirar”2, no solo entra en juego lo fisiológico, sino también lo psicológico y lo afectivo, dos factores que modificarán intensamente lo percibido.

A esta dupla psico-fisiológica debemos de agregarle la interpretación simbólica de lo observado para conformar así la compleja tríada que posibilitará el “Ver”, es decir, la comprensión de aquello que estamos viendo, dotándolo de sentido. Y este sentido estará dado por los “saberes acumulados”3, tanto adquiridos como heredados.

Y si el “Ver” no solo se encuentra condicionado por estos “saberes acumulados”, sino también influido por lo emocional circunstancial del momento y por lo psico-fisiológico propio de cada organismo, parafraseando a Heráclito de Éfeso cuando se le atribuye que dijo ‘En el mismo río entramos y no entramos, pues somos y no somos (los mismos)’ (Diels y Kranz, 1952), podríamos animarnos a plantear la idea de que No es posible ver dos veces la misma cosa, y por ende, si cada vez que viéramos fuera como “Ver” por primera vez, esa primera vez podría ser considerada como creadora, en tanto origen fundacional, punto de inicio de lo que hasta ese instante no existía. La existencia no precede a la experiencia. En tanto presente, olvidamos en el acto de “Ver” aquello que podría ser pasado, resignificándolo desde una mirada actualizadora y tornando inútil toda proyección hacia el futuro de lo visto. Casi como Winston Smith, el célebre personaje del libro “1984” de George Orwell (2006), quien cumplía - dentro del Ministerio de la Verdad - la función de reescribir una y otra vez los artículos periodísticos pasados, a medida que los “nuevos presentes” exigían “nuevos pasados” que los avalen.

Planteada esta cuestión y cómo desde el “Ver” se resignifica el espacio -y los objetos en él- incorporemos en este texto dos conceptos que nos permitirán seguir incursionando en la idea de “Ver el mundo”4 y no “al mundo”. Estos conceptos son los de asimilación y acomodación desarrollados por Jean Piaget5 (1991).

La asimilación se refiere al modo en que un organismo se enfrenta a un estímulo del entorno, modificándolo para adaptarlo a su organización actual.

Por su parte, la acomodación implica una modificación de la organización actual, en respuesta a las demandas del medio. Es el proceso mediante el cual, el sujeto se adapta a las condiciones externas, a la demanda del medio.

¿Si para asimilar el entorno lo modificamos, al tiempo que para adaptarnos a ese medio somos nosotros mismos quienes nos modificamos, cuanto del entorno inicial perdurará luego de ese contacto? ¿Y cuánto habremos asimilado de ese medio al punto tal de preguntarnos cuánto de nuestra percepción inicial del espacio perdura luego de esa experiencia?

Veamos un texto de Juan Muñoz-Rengel (1999) que quizá nos sea de utilidad para pensar cuanto de lo innato y cuanto de lo adquirido se pone en juego a la hora de percibir el espacio.

2 Ya que el mirar es un acto mucho más complejo que el ver, de aquí en adelante, cada vez que hagamos referencia al término “Ver”, lo haremos en este sentido y lo escribiremos con mayúscula y entre comillas, para diferenciarlo del ver, entendido como proceso fisiológico.

3 Entendamos estos Saberes Acumulados como el conjunto de constructos y conocimientos, tanto heredados por el contexto, como los adquiridos, fruto de las propias experiencias y sus resignificaciones, en un continuo ir y venir de lo social-colectivo a lo individual-particular y viceversa.

4 Entendamos este “Ver el mundo” en el sentido que le hemos dado al término “Ver”. Es decir, creando el mundo en el acto mismo de verlo. A diferencia del concepto “ver al mundo”, que estaría en relación a observar lo que nos es enseñado a ver.

5 Jean Piaget (1896-1980), epistemólogo, psicólogo y biólogo suizo, creador de la Teoría Constructivista del Aprendizaje y famoso por sus aportes en el campo de la psicología genética y su teoría del desarrollo cognitivo. Según este psicólogo, la capacidad cognitiva y la inteligencia se encuentran estrechamente ligadas al medio social y físico de la persona, siendo la asimilación y acomodación los dos procesos que caracterizan la evolución y la adaptación del psiquismo humano.

‘Otro experimento esclarecedor a este respecto es el ya clásico de Blakemore y Cooper Los investigadores criaron unos gatitos de 3 a 13 semanas de edad en un entorno visual que les restringía la experiencia a rayas verticales en unos casos, horizontales en otros. Cuando se les devolvió a un entorno normal la conducta de los gatos demostró que éstos eran insensibles a los objetos orientados en la dirección en la que habían sufrido la privación: aquellos que habían sido sometidos a la privación de rayas verticales chocaban, por ejemplo, con las patas de las sillas, pero no tenían problemas en utilizar los tableros como asiento. [...]

En conclusión, las experiencias de privación sensorial nos llevan a pensar que dichas carencias en los primeros estadios de desarrollo se traducen en grandes déficits perceptivos, por lo tanto: no es del todo cierto que la percepción del espacio sea una forma pura de nuestra sensibilidad totalmente independiente de la experiencia.’ (Muñoz-Rengel, 1999, p.152)

Por su parte, Erwin Panofsky (1985, pp.8-14) planteaba que:

‘La perspectiva central presupone dos hipótesis fundamentales: primero, que miramos con un único ojo inmóvil y, segundo, que la intersección plana de la pirámide visual debe considerarse como una reproducción adecuada de nuestra imagen visual. […] Estos dos presupuestos implican verdaderamente una audaz abstracción de la realidad.

[…] La construcción perspectiva plana […] solo se hace comprensible, en verdad, desde una concepción (particularísima y específicamente contemporánea) del espacio, o si se prefiere, del mundo.’

Desde una concepción particular y específicamente contemporánea del mundo… Detengámonos un poco en esta afirmación. Si unimos esto a lo ya dicho, en relación a que Ver es Crear, y si creemos en lo que vemos, entonces podríamos decir que Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer. Y desde este planteo, ¿sería posible pensar -en camino inverso- que creemos en lo que creamos ya que creamos lo que vemos? ¿Y si el discurso dominante de la época fuera quien creara lo que tenemos que “Ver” y las formas de verlo para que luego nosotros creamos en ello y desde el creer le demos validez, o sea, lo re-creemos? ¿Serían las imágenes reproducidas –tales como la pintura, la fotografía, el cine- las encargadas de enseñarnos a “Ver”?

Analicemos un poco algunos de los distintos sistemas de representación empleados a lo largo de la historia del arte de occidente y veamos si podemos profundizar en esto mismo.

La Perspectiva Caballera fue un modo de representar los objetos en un plano como si se los viera desde lo alto, es decir, considerando al observador ubicado por encima de los mismos. El término Caballera data del siglo XVI y su origen es militar. Una torre caballera es una construcción defensiva que forma parte de un castillo y se encuentra bastante más elevada que otras torres poseyendo un gran campo de visión. Pero esta posibilidad de ver por encima del resto también la tenían los Caballeros, quienes montados sobre sus caballos gozaban de un campo de visión mayor que los soldados a pie. Y si pensamos que quienes vivían en las alturas de los castillos tendrían también acceso diario a este tipo de visión, ¿sería malicioso pensar que aquellos que financiaron la producción pictórica de la época, a fin de cuentas financiaron la representación de su propio punto de vista de la “realidad”? ¿O acaso la mayoría del pueblo tenía acceso a ese punto de vista?

Concentrémonos ahora en otro tipo de perspectiva: La Inversa. Este tipo de perspectiva, también llamada Invertida, era utilizada en la pintura gótica o prerrenacentista, y consistía en representar los objetos o personas de modo más pequeño en el primer plano, y los más grandes, en el último. O dicho de otro modo, se agrandan a medida que se “alejan” del espectador. Pensemos que desde una concepción teológica del mundo, donde lo mediato, lo terrenal, es considerado un paso para alcanzar el verdadero objetivo que es la vida después de la muerte, el paraíso se torna una idea grandilocuente en comparación con los placeres terrenales. Y siendo “Dios” y la vida en “el más allá” lo que posee mayor importancia para la época, no sería ilógico pensar que una representación visual que acompañe al paradigma imperante muestre justamente, en un tamaño mayor a las figuras colocadas en el plano pictórico-compositivo más “alejado” del espectador y, por ende, lo más “próximo”, en analogía con lo terrenal, lo sensible, sea representado a escala más pequeña que lo anterior.

Siguiendo esta lógica hipotética, el Renacimiento, fruto de la difusión de las ideas del Humanismo, marca un giro en la concepción del Hombre y el Mundo. El Antropocentrismo reemplazará al Teocentrismo. El hombre, ahora, es medida de todas las cosas, adquiriendo la razón humana un valor supremo. En pintura se desarrolla un sistema de representación acorde a la época: la Perspectiva Central y el concepto de cuadro como “ventana al mundo”. Una nueva manera de “Ver”. Desde “dentro” y “a través” (Perspicere), claro está.

Esta nueva visión del mundo tomando al hombre, y sobre todo a la razón, como centro, ameritaba un cambio radical en el sistema compositivo utilizado en el Medioevo. Y este cambio radical invierte las proporciones de las figuras dentro del plano compositivo. Ahora, lo más próximo se torna de mayor importancia. ¿Y si a causa de esto fuera que se representa de mayor tamaño a las figuras ubicadas en el “más acá” del plano compositivo, y en contraposición, el “más allá” sea representado a escala menor? Figura y fondo seguirán compitiendo, solo que con los roles invertidos.

Y si cada época generó un sistema para representar su “realidad” podríamos pensar que dicho sistema no solo expuso dicha “realidad” sino que también enseñó a verla. Y si Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer podríamos, continuando en esta línea de pensamiento, inferir que quienes tuvieron el control de los medios de producción visual han tenido a fin de cuentas el control de los medios de “Producción de Realidad”.

¿Pero qué sucede cuando, hoy en día, dichas imágenes se reproducen y difunden –vía Internet- más allá de sus contextos contenedores originales? ¿Enseñan a “Ver” o son (re)leídas?

Y en el caso puntual de la Performance como disciplina artística, donde el cuerpo es presencia y lo que se difunde a posteriori son los registros de lo acontecido en dicha acción, ¿podríamos pensar que dichas imágenes cobrarían presencia en sí mismas desplazando al cuerpo que les sirvió de origen? ¿Y qué sucede cuando la imagen que había reemplazado al cuerpo es ahora reemplazada por una nueva imagen que a su vez es imago de otra y de otra, etc.?

Las nuevas tecnologías, los nuevos espacios virtuales como Internet, lo posibilitaron. Lo impusieron. Ya sin un cuerpo –o al menos sin el cuerpo tal y como se lo pensaba hasta hace pocos años- una nueva materia sin materia, un nuevo Cuerpo, el virtual, comenzó a hacerse presente en escena. Un espacio virtual regido por leyes distintas a las del espacio en que nos encontramos. Donde los objetos no dependen de las leyes físicas para su composición ni su percepción, ni tampoco de los paratextos que los “contienen”. Donde sus características están dadas por los conceptos de “Ubicuidad” y “Presencia a distancia”. Donde se habla con términos como “acceder”, “entrar”, “conectarse”, “estar On Line". Términos que remiten a la sensación de ingresar a ese espacio virtual cada vez que se está frente a una computadora conectada a Internet. Ya sin Dioses ni cuerpos, porque todos y todas somos Dios. Porque que el término Ubicuo que procede del latín ubīque, significa “en todas partes”. Mismo término que se utilizó como un adjetivo atribuible al Dios judeocristiano en tanto que señalaba su capacidad para estar presente en todas partes al mismo tiempo. Omnipresencia de ese Dios de antaño, que ya sin cuerpo, compite a diario con miles de personas que abandonan su corporalidad, o en todo caso, la expanden, en un nuevo y más amplio concepto de Cuerpo y Espacio.

‘Aunque el cyberespacio suele representarse espacialmente, no es un lugar ni una cosa. Consiste en una suma de sinapsis electrónicas que intercambian millones de bits de información a través de líneas telefónicas o fibras ópticas conectadas por redes de computadoras. No está dentro de las máquinas, ni en el tejido o red que se construye por sus interconexiones: es un territorio intangible al que se accede por medios tangibles.’ (Bonder, 2002, p.29)

¿Y si el Espacio no fuera lo que vemos sino que lo que vemos es el Espacio? ...

Performance

‘Toda comunicación tiene un aspecto de contenido y un aspecto relacional tales que el segundo clasifica al primero y es, por ende, una metacomunicación.’ (Watzlawick, Beavin y Jackson, 1981, p.56)

‘No es posible no comunicarse.’ (Watzlawick, Beavin y Jackson, 1981, p.52)

¿Es posible no representar?

El cuerpo en la Performance

En la Performance, el artista en tanto sujeto se convierte en objeto, y su cuerpo - territorio de significaciones - en un mapa desplegable que lo trascenderá, “tocando” a las personas que lo observan e integrándolos a la acción. Este cuerpo individual se vuelve Cuerpo, es decir, trasciende los límites de la propia historia abarcando la historia personal de cada uno de los presentes tornándose por ende en un Cuerpo colectivo. Desde un inicio, el organismo con el que nacemos se pondrá en contacto con los Otros y de las experiencias surgidas de esos encuentros, se formará Cuerpo. Es decir, implicará la suma de los órganos, más la suma de todas las experiencias producto del contacto con los otros Cuerpos. Será ante todo, relación, y es en la Performance donde se tiene la oportunidad de activar este potencial de relación por medio de la empatía, que no será otra cosa que una actualización de la memoria del propio organismo devenido en Cuerpo.

El espacio en la Performance

Cuerpo que afecta un espacio que afecta un cuerpo

Espacio ≠ Lugar

Un espacio se conoce. Un lugar se re-conoce

Un lugar es un espacio que se ha transitado y vivenciado con anterioridad. Cargado de afectos, un lugar está más próximo de ser un “espacio conceptual” que uno físico. Nada vuelve a ser igual luego de que la subjetividad lo atraviesa.

Los lugares están atravesados por las acciones que allí se realizan. Y es en este punto donde surge una interrogante. ¿Es el lugar atravesado por la acción o la acción atravesada por el lugar?

Pensemos en una casa. Cualquiera que sea. El espacio físico en ella está delimitado, es cierto, pero no solo por paredes divisorias. También está delimitado por las funciones que cumplen cada espacio, es decir, por las acciones que en ellos se realizan. Y cada espacio a su vez determina lo que está permitido o no hacer allí. Por ejemplo, puedo ir a la casa de un amigo y orinar en la cocina pero de seguro recibiré una queja al respecto. Hay un dicho que dice “Cada cosa en su lugar y un lugar para cada cosa”. ¿Será así de cierto como dicen? ¿O será que algunas acciones pueden habilitar que determinados lugares muden de espacio?

El patio de una casa podría ser el lugar de esparcimiento para sus habitantes, pero si decido asar unas verduras allí, dicho patio se convertirá –temporalmente- en el lugar de cocina.

¿Podríamos deducir entonces que una de las características de los lugares es su capacidad de mudar de espacio?

La Performance, en tanto articuladora de subjetividades y productora de realidades tiene la capacidad de crear6 lugares. Una acción define o da origen a un lugar, transformando temporalmente lo que antes era un espacio. Y en el caso de la Performance, dicho espacio puede convertirse en un lugar de arte, un lugar de intimidad o un lugar de reflexión entre tantas otras posibilidades.

¿Y qué sucede cuando en la Performance, el cuerpo que es soporte de obra se encuentra mediado y distanciado de los demás cuerpos, tornándose Cuerpo y prescindiendo de su materialidad? ¿Qué sucede con el cuerpo cuando la tecnología posibilita el paso de la presencia a la Telepresencia?

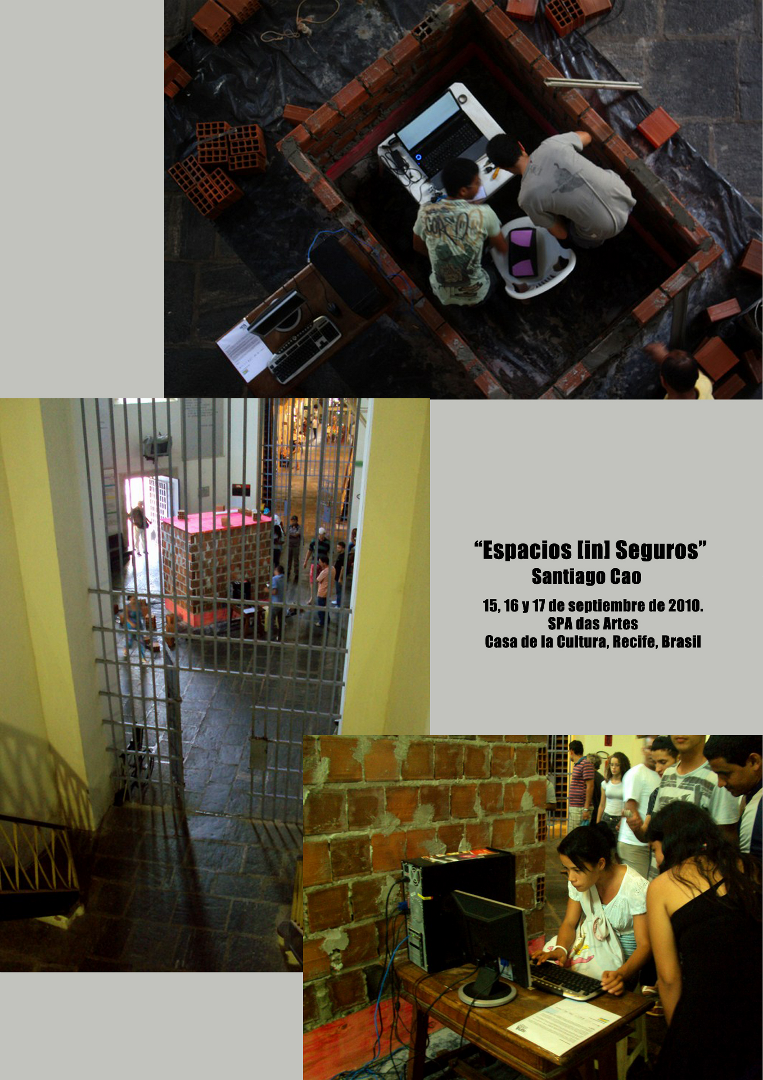

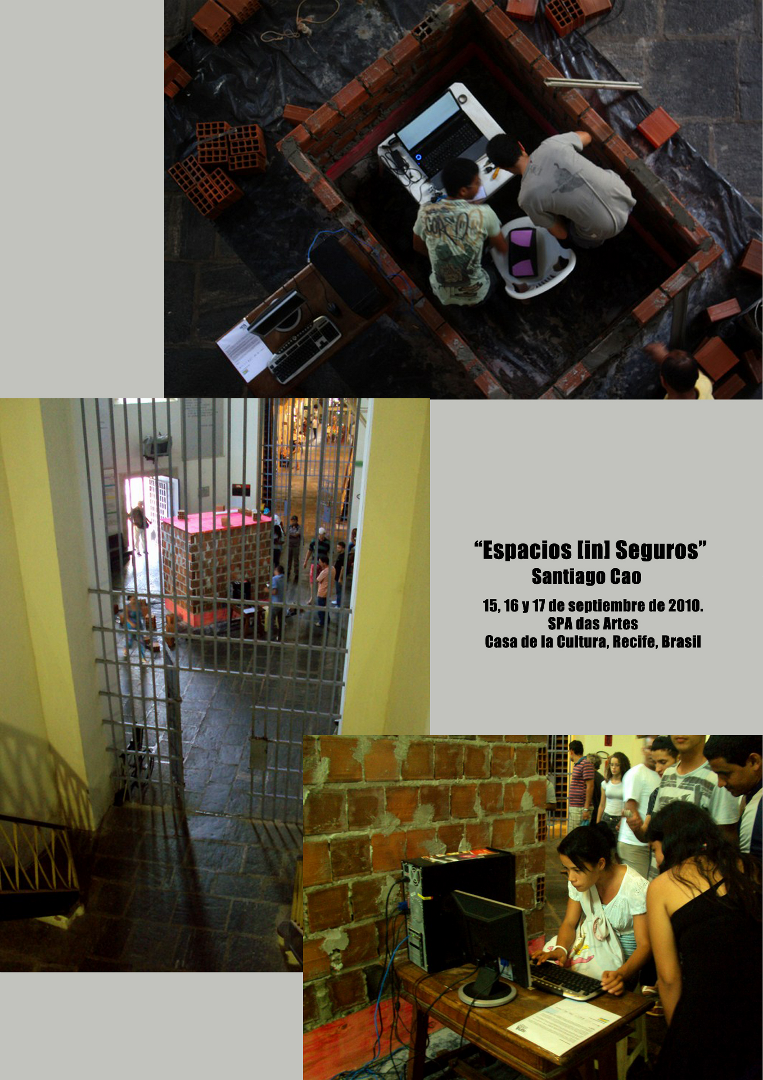

Mencionemos, a modo de ejemplo, una Instalación Performática que he realizado en septiembre de 2010 en la ciudad de Recife, Brasil, en el contexto del festival de artes visuales “SPA das Artes” y que titulé “Espacios [in] Seguros”. En aquella oportunidad, y trabajando junto a Rayr Dos Santos Silva en el rol de “apoyo de tecnología de la informática”, y Luis Cavalcanti como albañil, reflexionaba en relación a la inseguridad manifiesta por los medios masivos de comunicación. Inseguridad convertida por dichos medios en “sensación de inseguridad” ante la cual la sociedad responde aislando y encerrando lo “amenazante” en cárceles y manicomios, al tiempo que se distancia construyendo espacios cerrados y exclusivos donde sólo unos pocos pueden entrar. La jaula de cemento y la jaula de oro. Dos variantes del encierro, dos caras de una misma moneda.

Reflexionaba en aquella obra que de manera cada vez más frecuente, las personas estamos perdiendo las relaciones inter-personales. La situación en sí es preocupante. Nos estamos distanciando y el “Otro” es un desconocido con quien mejor no entrar en “contacto”.

De igual manera las telecomunicaciones han ayudado a desplazar la comunicación personal. Teléfonos, mensajes de texto, correos electrónicos. Cada vez menos personas hablan “cara a cara”. Lo corporal es desplazado por lo virtual. Un muro invisible nos separa. En la obra “Espacios [in] Seguros” ese muro se torna visible y la metáfora resulta un encierro efectivo.

Dentro de la “Casa de la Cultura” de Recife, antigua cárcel convertida en centro comercial para turistas, Cavalcanti construyó con ladrillos y cemento cuatro paredes, encerrándome en un espacio de 1,30 x 1,80 mts. Permanecí dentro de ese espacio reducido por el lapso de tres días.

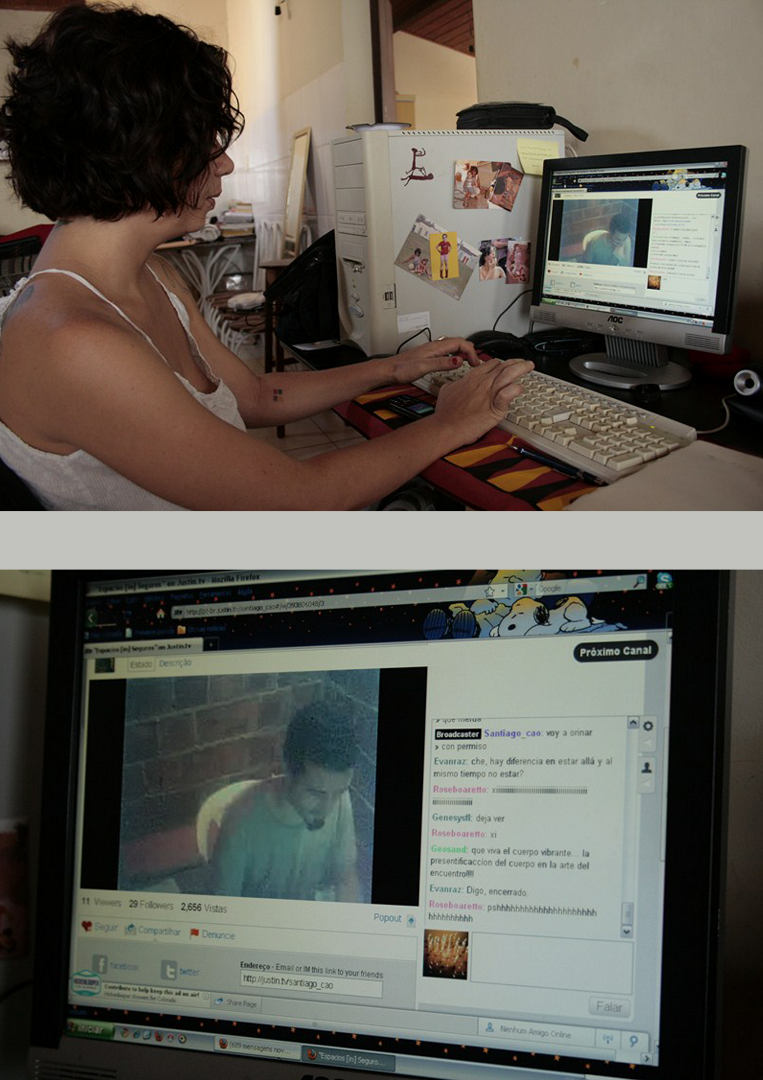

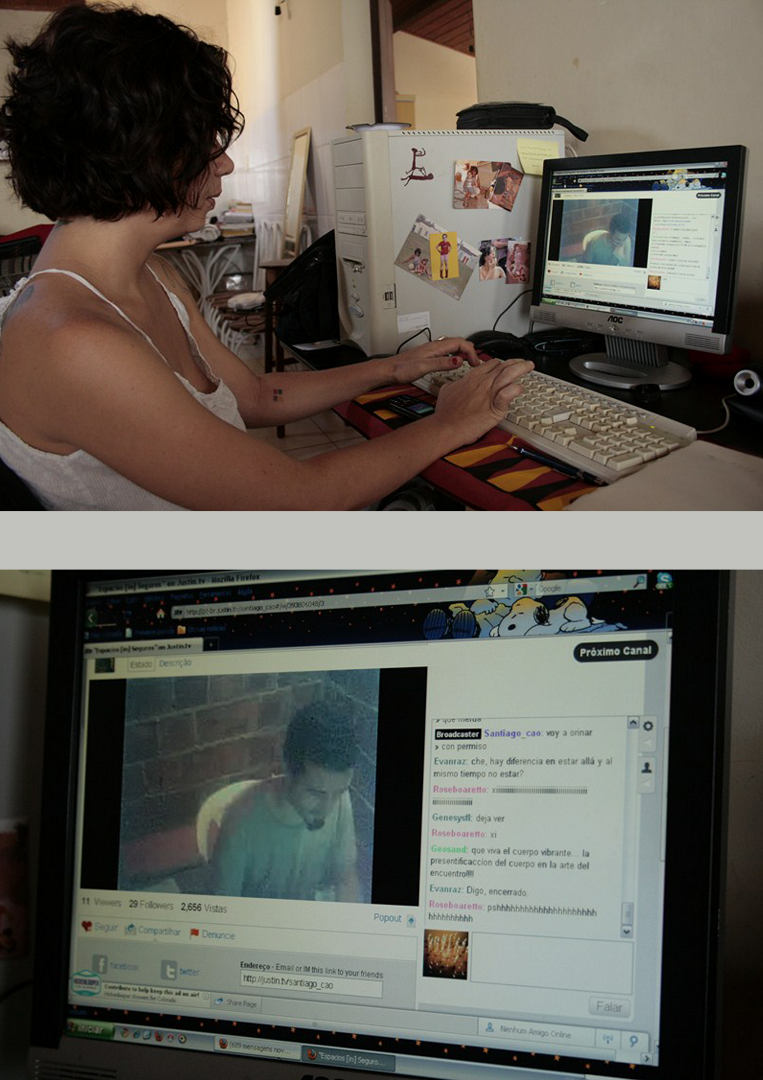

Sin ventanas ni puertas, la única comunicación posible fue a través de una computadora conectada las 24 horas a Internet. Tres días transmitiendo en directo mediante un Streaming7, utilizando una cámara web y relacionándome con las personas por medio de un chat. Tres días interactuando virtualmente hasta ser liberado, paradójicamente, por la misma persona que me encerró; por ese “Otro” del cual me distanciaba.

Por fuera, en uno de los lados de la construcción, estaba instalada una segunda computadora configurada para conectarse únicamente al Streaming. De esta manera las personas que por allí pasaban podían elegir ver el “Espacio [in] Seguro” desde fuera o sentarse frente a la computadora y, por medio de la transmisión, ver el interior e interactuar conmigo a través de un chat.

Durante los tres días no utilicé la palabra hablada, comunicándome únicamente por ese chat. La mayoría de la gran cantidad de personas que por allí interactuaron conmigo, solo querían saber el por qué estaba haciendo eso. Preguntaban también cuestiones relacionadas a las necesidades básicas como ser la alimentación y donde iría a orinar o defecar. Fueron realmente pocas las personas que se quedaron a conversar, entre ellas y conmigo, en relación a la temática propuesta de las comunicaciones virtuales y el distanciamiento de los cuerpos. Pero lo notable fue la gran diferencia que se produjo entre quienes interactuaban desde el computador ubicado al lado del “Espacio [in] Seguro” y quienes lo hacían a la distancia, es decir, desde otras ciudades o países. Mientras que estos últimos aguardaban con paciencia el ser respondidos dada la gran cantidad de personas preguntando y mi incapacidad de responderles a todos al mismo tiempo, los primeros, es decir, los que se encontraban de cuerpo presente en el mismo lugar de la instalación, en su mayoría reclamaban ser contestados argumentando en algunos casos “respondé, hemos venido hasta aquí para verte y nos ignorás”. Incluso sucedió que algunas veces, cuando ya no podía con el cansancio y la fatiga que producía el estar frente al computador durante tantas horas manteniendo múltiples conversaciones simultáneas, y quería recostarme en el suelo a descansar un poco, algunas de estas personas comenzaban a golpear violentamente los muros y sucedió que una de ellas escribió en el chat “¡Levantate vago, hemos venido hasta aquí para verte y estás acostado!”. En esos momentos, no tenía otra opción que reincorporarme y volver a sentarme frente al computador para responder sus preguntas. Pareciera ser que tras esa pantalla de computadora, quien era observado no fuera una persona sino un programa de entretenimientos.

Fueron precisamente los momentos más tensos y agotadores de la experiencia los que correspondían al horario de apertura de la Casa de la Cultura. De tal manera, como si fuese un trabajo, de 9 a 19 hs mi vida se tornaba un espectáculo, a veces sádico, en el cual debía cumplir con las exigencias de los visitantes, mientras que luego del cierre y por las noches, el nivel de comunicación se tornaba agradable, y junto con esos Otros las distancias físicas parecían atravesarse, compartiéndose la soledad de tantos encierros.

Momentos previos a la liberación, cambié la cámara que estaba en el ángulo de la construcción por la que estaba en mi computadora. La primera, con un campo de visión mayor, permitía captar el espacio desde un ángulo superior más amplio, generando la sensación de ser una cámara de vigilancia mostrando a una persona, de la cual solo se veía su cabeza. Una imagen cuasi anónima… un rostro casi borroso. Pero para la liberación, la cámara de la computadora (que captaba un plano frontal de la pared) permitía no solo ver “de cerca” el instante en que el albañil rompiera con cincel y martillo los ladrillos abriendo un boquete por donde liberarme, sino que luego, por ese mismo boquete, transmitiría en directo el afuera… para los que desde fuera vieran por medio de su monitor ese “adentro”.

Un amigo, presente físicamente en ese momento, me contaría luego que le llamó la atención el darse cuenta que muchas de las personas allí reunidas, optaron por seguir todo el proceso de liberación observándolo desde el computador ubicado al lado del muro en vez de ver al albañil de cuerpo presente romper con cincel y martillo los ladrillos. Sólo al aparecer mi cuerpo en el exterior, dejaron de prestar atención a la transmisión.

Ya liberado, la cámara siguió transmitiendo durante un día más, de manera tal que cuando algún curioso o curiosa se asomaba por el boquete, era a su vez retransmitido por la cámara web y visto, entre otros monitores, por el que estaba conectado a la segunda computadora, a tan solo medio metro de distancia de la construcción. De esta manera mientras las personas asomaban la cabeza e ingresaban parcialmente al “Espacio [in] Seguro”, se iban “virtualizando”, creándose la paradoja de un tercer lugar o espacio. El actual (la persona y la construcción de ladrillos y cemento), el virtual (la transmisión vía cámara web) y el cruce de ambas, donde simultáneamente el espectador o espectadora presente en el lugar podía ver “un cuerpo sin cabeza” y “una cabeza sin cuerpo” según se la observara de cuerpo presente o a través del monitor.

Al día siguiente de haber sido liberado, cuando fui a iniciar el desmontaje me encontré con dos niñas pequeñas que, jugando con la instalación, me permitieron comprender una cuestión que no había siquiera imaginado. La temporalidad y sus posibles desdoblamientos. Su juego consistía en asomarse por el hueco en la pared y bailar frente a la cámara para luego correr hacia la segunda computadora distante 2 metros de ellas y, producto del delay, verse a sí mismas, en tanto otras, asomar la cabeza dentro del hueco, bailar y luego desparecer de la pantalla. En un solo acto, eran motores de acción y espectadoras de sí mismas. “Ellas” y “Otras” al mismo tiempo. El retardo de la transmisión creaba así una paradoja témporo-espacial. Ellas, que 5 segundos antes estaban saltando frente a la cámara en un tiempo y espacio presente, ahora se encontraban duplicadas en un tiempo y espacio virtual. Y prefiero designar con el nombre de “virtual” y no de “representado”, ya que en el caso de la imagen transmitida -en tanto no era una reproducción grabada previamente, re-presentada, sino una transmisión “en vivo y en directo”- era el retardo el que permitía la coexistencia, en un mismo tiempo presente, de esos dos tiempos y espacios. Y si lo que caracteriza y diferencia a lo presente-actual de lo representado-actualizado es justamente su carácter de transitoriedad, de efímero, entonces estaba frente a un tercer tiempo y espacio: el Virtual.

¿El espacio del cuerpo en el espacio del Cuerpo?

Si el “Cuerpo”, liberado de la materia a la que estaba remitido en tanto cuerpo, fue nuevamente atrapado en modos de “Verlo” condicionados por quienes ostentaban los dispositivos de reproducción de imágenes, es decir, quienes –desde la premisa Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer- tenían la posibilidad de “producir Realidad”, con el arribo de las nuevas tecnologías este “Cuerpo” es nuevamente liberado, pero ahora, de la construcción unívoca de un Tiempo y Espacio propios de un mismo contexto y paratexto. Ahora, con el uso entre otras herramientas del Streaming, distintos observadores en distintos contextos tienen la posibilidad de (re)crear lo visto según sus propios modos de “Ver”.

Figura 1, 2, 3 – Evento Espacios [in] Seguros. Fotes: Arquivo pessoal, 2010. (autores: Enaile Lima, Zmário Peixoto, Juan Montelpare, Santiago Cao)

Y si quien hace los recortes, las ediciones (las representaciones) es considerado autor de lo representado, ¿que acontece cuando las nuevas tecnologías colocan a esos otros observadores como co-creadores de lo visto? Podríamos pensar aquí que estas nuevas tecnologías favorecerían a generar una dilución de la autoría, mismo sin que se lo pretenda o se lo intente evitar.

6 Escojo la palabra “crear” en vez de otras tales como “generar” o “producir” siguiendo lo planteado en relación a que “Ver es Crear y Crear es Creer”.

7 Un Streaming es un flujo de datos en tiempo real. Es decir que quien transmita vía Internet podrá hacerlo “en vivo” y para un gran número de espectadores quienes a su vez verán dicha transmisión sin ser vistos. Es decir, la transmisión de imagen y audio se da de manera unidireccional, similar a la tradicional TV, con la innovación y agregado de un chat que permite a dichos espectadores interactuar (tanto entre ellos como con quien transmite) por medio de comentarios escritos en el mismo.

Sin ánimos de emitir un juicio valorativo sobre los usos de las nuevas tecnologías aplicadas al arte y el nuevo lugar que ocupa el “Cuerpo” en esta “Producción de Realidad”, me pregunto qué sucederá si algún día la materialidad fisiológica del cuerpo es finalmente desplazada hacia otras materialidades, que en tanto soporte de imagen, se adapten mejor a los nuevos modos de “Ver”.

Bibliografía

Bonder, G., 2002. Las nuevas tecnologías de información y las mujeres: reflexiones necesarias. Santiago de Chile: United Nations Publications.

Diels, H. y Kranz, W., 1952. Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker. Berlim: Weidmann.

Ferrater-Mora, J., 1965. Diccionario de Filosofía. 5ª ed. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana.

Fuentes-Martínez, M. E., 2006. El Esquema y la Imagen Corporal. Sociedad de Psicoterapia y Psicoanálisis del Centro A C [online]. Disponible en <http://www.sopac-leon.com/soppac/articulos/elesquemacorporal.pdf> [Consultado 22.07.2012].

Freud, S., 1979. El Yo y el Ello y otras obras, Tomo XIX. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores.

Gran Enciclopedia Rialp, 1991. Cuerpo Humano II [online]. Madrid: Ediciones Rialp. Disponible en <http://www.canalsocial.net/Ger/ficha_GER.asp?id=9644&cat=medicina> [Consultado 22.07.2012].

Matlin, M. y Foley, H., 1996. Sensación y Percepción. México: Prentice Hall.

Merleau-Ponty, M., 1992. O Visível e o Invisível . São Paulo: Perspectiva.

Muñoz-Rengel, J, 1999. Los ‘apriorismos’ kantianos bajo juicio cognitivo. Revista de Filosofía de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid [online] Volumen 22. Disponible en: < http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=19715> [Consultado 22.07.2012]

Orwel, G., 2006. 1984. Buenos Aires: Booket.

Panofsky, E., 1985. La perspectiva como forma simbólica. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Piaget, J., 1991. Seis estudios de psicología. Barcelona: Labor.

Real Academia Española, 2001. Diccionario Online de la Lengua española [online]. 22º ed. Disponible en < http://www.rae.es/dpd/> [Consultado 22.07.2012]

Spitz, R., 1996. El primer año de vida del niño. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Watzlawick, P. Beavin, J. y Jackson, D., 1981. Teoría de la comunicación humana. Barcelona: Herder.

Body and Performance in the Era of Virtual Communication: The space of the Body in space of the body

Santiago Caoholds a BA degree in Visual Arts and followed up with studies in Psychology. He teaches Visual Language at IUNA (Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte) in Buenos Aires.*

How to quote this text: Cao, S. 2012. Body and Performance in the Era of Virtual Communication: The space of the Body in space of the body. Translated from spanish by Paulo Ortega. V!RUS, n. 7. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 30 June 2025].

Abstract

“Seeing” is a much more complex than a purely physiological act. It involves, among other things, acquired and inherited knowledge that, as tools, will serve us for decoding what is seen, to understand it and to assimilate it. And when I make this distinction between acquired and inherited, I do it regarding the former as a result of subject’s own existence which generates experience and therefore a personal way of "Seeing to the world", unlike the inherited knowledge ("Seeing the world") which is imposed by the culture that creates raises the subject (or should I say that co-raises it?). But "seeing the world" is not the same as "seeing to the world." To make this distinction, we must develop in this text the premise of "Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing", which will then be useful to think that: if what we see is not what it is but what we believe it is, what happens then to the devices of visual representation of "reality" and to those with the power to disseminate those devices? But new technologies such as the Internet and cellular telephony have led to a break in this concept, traversing the notions of context and paratext, expanding the creative act of "seeing" and thus generating new realities from a same observed event. And the body in all this will not be left out. We will think on what happens in Performance as an artistic discipline, where the body, which was traditionally support for the work, now faces these new ways of seeing and creating it.

Keywords: Body; performance; display devices; representation devices, virtual communications; production of reality.

title note1

An approach to the Body

If we are going to consider the body as a support for work, we should first define what is the "Body", find a common point, propose a base from which to think together. But what we call body, does it exist as such?

According to Gran Enciclopedia Rialp de Humanidades y Ciencia (1991):

The body is the set of structures harmoniously integrated into a morphological and functional unit that constitutes the physical support of our person during life, specifically differentiated in only two types, male and female, depending on the nature of our own sex.

206 bones (excluding teeth), ligaments, tendons, muscles and cartilage. Veins, arteries and capillaries. Organs such as kidneys,liver, lungs, pancreas and others. One head, one torso, two arms and two legs. Two eyes, one nose, one mouth. Hands (two), fingers (twenty). Skin. Nails, hair. Blond, dark-haired, brown, red headed? Urine? Fecal Matter? Blood. Menstruation? Semen, vaginal fluid? Penis or vagina according being male or female. A "man’s body". A "woman's body". A woman "trapped" in a "man’s body"? A man "trapped" in a "woman's body”?

A living body. A dead body. A body in Buenos Aires. A body in France. A body in India. A body in the street. A body on the floor, on a avenue. A body in a bed.

What is the "Body"? Which is its space? Which are its limits?

So when we talk about "Body"... what are we referring to?

Let us start with our own body. We are not aware of it if not through our senses and the reading or interpretation we make of the information captured by them. Matlin and Foley (1996, p.554) state that:

The sensation refers to basic immediate experiences generated by single isolated stimuli; (instead) the perception includes the interpretation of those sensations, giving them meaning and organization.

Since the senses are ways of incorporating information, could we think of our body as a perception?

Interoceptors, propioceptors and exteroceptors are responsible to capture the information needed for perceiving our bodies. In such a way that an injury to any of the sense receptors would be enough for our sensation, and therefore our bodily perception, to change, thereby changing our body schema.

The body schema is, then, the representation that the human being forms mentally of his body, through a sequence of perceptions and responses experienced in the relation one another (Fuentes-Martinez, 2006, p.2).

But our awareness of body, our body schema, is not always the same nor is present since our first moments of life. According to psychoanalytic theory proposed by Freud (1979), the constitution of the Self is a gradual process that leads from the Non-Self to the Self. A poor development of the Self would result in a distortion of Body Schema and, therefore, of the notion of body itself.

Meanwhile, the psychiatrist René Spitz (1996) divided the first year of the baby into 3 stages, noting that during the first one, called "Pre-objectal or objectless" and that goes from 0 to 3 months of age, the newborn cannot distinguish an external thing from his own body. He cannot experience something separate from himself. Thus, the maternal breast that provides his food would be perceived as a part of him and not as another person that feeds him.

Body - Non-body

I can define it more easily by what it is not than by what it is. It is not a turd; although I could also call Fecal Matter the substance in the toilet bowl that minutes before was lodged in my large intestine. However, I prefer the first term because Fecal Matter still retains a reminder of its origin.

What about urine? What about blood? Are they part of my body or just within it? What if it's something I can lose or remove; is it still my body?

And this hand that by (de)finition, (de)limitation, has five fingers; if I lose any of them in an accident, would it still be a hand?

And that finger, that little strip of flesh and bones lying severed on the ground or trapped inside a machine; is it also my body? Is it part of the whole?

And if the hand does not need fingers to be a hand, is the whole composed of its parts?

*For more about his work visit <www.artistanoartista.com.ar/inicio.php> and <www.facebook.com/cao.santiago>.

1We must differentiate the body, as a biological organism, from the "Body" with capital letter, understanding the latter as a construct even more complex than the organic. The Body, which houses the culture in which it is immersed. That hosts the expectations of others. That is shaped by the gaze of others which, introjected, become "Other." This body which, expanding itself toward the surrounding objects, becomes an even more complex Body. And as a Body, it can become virtualized, travel long distances without moving from place and, paradoxically, can lose its corporality without losing its presence.

That hand without fingers, the knuckle at the end of my arm, it is body.

And those fingers without hands?

It would seem that we have a schizoid relationship with our own body. It would be enough separating a part of it from the rest to no longer consider that part as body. And however many of the objects that surround us, the external-non-body, are perceived as attachments to the body. Let us take, as a rough example, a person driving his car on a street. Imagine him parking next to the sidewalk. Getting out. Locking the door. Activating the alarm. Imagine he walks two meters and remembers he forgot taking his book. Let's watch him turn his body at the precise instant the car parked in front of his rams his own car, smashing the glass of the headlights. Imagine this man frowning, squinting, raising his arms and one hand to his head. Imagine him with a gesture of pain, yelling at the other driver, You hit me!

Let us now ask, of course, how it could have crashed into him if he was two meters away. If his car was hit and not his body? Or was his body hit? His face in pain and the shouted phrase make me suspicious of any claim. There is a continuum with some objects adjacent to us. It seems that the "Pre-Objectal or objectless" stage to which we referred, remains present even beyond 3 months of age. It seems that, even as adults, it is difficult for us distinguish an external thing from our own body. As if the car, in this example, was an analogy for the breast described by Spitz (1996). A breast that, as provider of food, is perceived by the child as a part of himself and not as part of another person who feeds him. As an attachment to the body. Strangely... a body of metal, plastic and rubber, that as well as our feces, whose contaminant gases do not belong to us.

What if the body was not a body but our perception of our own body?

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1992, p.16), in his posthumous book The Visible and the Invisible, argued that "It is true that the world is what we see and that, however, we need to learn to see it".

The body is, according to this philosopher, a component of both the perceptual openness to the world and of the creation of that world. A permanent condition of existence.

Without intension to deeper into his statement, let’s use this phrase as a springboard to "jump" to other concepts which, "linked", allow us to support the initial premise of Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing.

The body – the "body itself" – is not an object. The body as object is, at best, the result of insertion of the organism in the world of "in itself" (in the sense of Sartre) (Ferrater-Mora, 1965, p.389).

What if the world of "in itself", the world of things, was the resulting from perception of this organism?

Space

Throughout Western history, the debate on the issue of Space has changed as paradigms have "fallen" and been replaced by the following ways of thinking about the world. In such a way, we could roughly argue that the issue of space was debated from two theoretical positions: those who studied space in relation to a subject or a consciousness, and those who considered the space itself. We should adhere in this text to the first of these positions.

However, not only thinking space but also representing it graphically in different ways has been sought throughout that history. Multiple representation systems have been used, including the Perspective.

This word, of Latin origin, which etymologically arises from the verb perspicere, means to see through (to see -spicere- through, or carefully -per-). It is interesting to note that one of its derivations is the word Perspicacity (Perspicacia) which, according to the Royal Spanish Academy (2001) means:

1. Acuity and penetration of the sight.

2. Penetration of wit or knowledge.

Let us be, then, perspicacious, and try not only to see "through" perspective but also beyond it.

Let us first make a distinction over seeing and looking. To see is an electromagnetic function where – according to the capacity of each visual organ to capture and react to the incidence of light waves on the retina – information will be projected through the optic nerve to the brain, which will decode the stimulus to build a mental picture of thereof. The humans, like other animals, possess the ability to focus both eyes on the same object allowing what is called stereoscopic vision. This type of vision allows, among other things, to grasp the depth of visual field. But not all the sense organs are the same in each person nor does each person see the same thing twice. The incidence of light on an object will cause variation in the perception thereof. A can of tomatoes observed in the early hours of the morning on a sunny day will not look the same at noon. The light in the second situation will be clearer than in the first, and if we take into account that the sun in zenith position will not cast shadows of the can, we can more easily grasp it. And much more than if we tried to see it in the dark of night. But in the act of "Seeing"2 come into play not only the physiological but also psychological and emotional, two factors which will strongly modify what is perceived.

To this psycho-physiological duo we must add the symbolic interpretation of what is observed to thereby form the complex triad that will enable "Seeing", namely, the understanding of what we are seeing, giving it meaning. And this meaning will be given by "accumulated knowledge"3, both acquired and inherited.

And if "Seeing" is not only conditioned by this "accumulated knowledge" but also influenced by the moment’s circumstantial emotional and by the psycho-physiological characteristic of each organism, to paraphrase Heraclitus of Ephesus when he is credited with saying “We step and do not step in the same rivers as we are and are not (the same)" (Diels and Kranz, 1952), we could be encouraged to propose the idea that one cannot see the same thing twice. And therefore, if every time we have seen were as "Seeing" for the first time, this first time could be considered creative, as a foundational origin, a starting point for what until that moment did not exist. Existence does not precede experience. As present, we forget in the act of "Seeing" what could have been past, resignifying it from on a actualizing glance and making useless any projection into the future of what is seen. Almost like Winston Smith, the famous character from the book 1984 by George Orwell (2006), those who had – within the Ministry of Truth – the function of rewriting over and over past newspaper articles, as the "new presents" demanded "new pasts" that supported them.

Having this question raised, and since from "Seeing" space is resignified – as the objects in it – let us incorporate in this text two concepts that will allow us to follow venturing into the idea of "Seeing the world"4 and not "to the world". These concepts are assimilation and accommodation developed by Jean Piaget5 (1991).

Assimilation refers to how an organism faces an environmental stimulus, modifying it to suit its current organization.

In its turn, accommodation implies in a modification to the current organization in response to the environmental demands. It is the process by which the subject adapts to external conditions, to environmental demands.

If in order to assimilate the environment we modify it, while for adapting to this environment we modify ourselves, how much of the initial surroundings will survive after this contact? And how much of the environment we will have assimilated to the point of wondering how much of our initial perception of space remains after that experience?

Let us take a text by Juan Muñoz Rengel (1999) that may be useful for thinking on how much of the innate and how much of the acquired comes into play at the time of perceiving space.

2Since “Seeing” is a much more complex act than “to see”, from now on, whenever we refer to the term "to See", we will be using this meaning and write it with a capital letter and quotation marks to distinguish it from to see, understood as a physiological process.

3Let us understand this Accumulated Knowledge as a set of constructs and knowledge, both those inherited from the context and those acquired, product from one’s own experiences and the new meanings endowed to them, in a continuous coming and going from the social-collective to the individual-particular and vice versa.

4Let us understand this "Seeing the world" in the sense we have given the term "Seeing". That is, creating the world through the very act of seeing. Unlike the concept "seeing to the world", which would be related to observing what we are taught to see.

5Jean Piaget (1896-1980), epistemologist, Swiss psychologist and biologist, creator of the Constructivist Learning Theory and famous for his contributions in the field of genetic psychology and his theory of cognitive development. According to this psychologist, cognitive ability and intelligence are closely linked to the social and physical environment of the person, with assimilation and accommodation being the two processes that characterize the evolution and adaptation of the human psyche.

Another enlightening experiment in this regard is the already classic by Blakemore and Cooper. The researchers bred kittens from 3 to 13 weeks of age in a visual environment that restricted their experience to vertical lines in some cases, or horizontal in others. When they returned to a normal environment the cats’ behavior showed they were insensitive to objects oriented in the direction they had suffered privation: those who had been subjected to privation of vertical lines, for example, collided with the chair legs, but had no problems in using boards as a seat. [...]

In conclusion, sensorial privation experiences lead us to believe that these lacks in the early stages of development translate into large perceptive deficits, therefore: it is not quite true that the perception of space is a pure form of sensibility fully independent of experience. (Muñoz-Rengel, 1999, p.152)

Meanwhile, Erwin Panofsky (1985, pp.8-14) argued that:

‘The central perspective presupposes two fundamental assumptions: first, that we see with a single and immobile eye, and second, that the planar cross section of the visual pyramid should be considered an adequate reproduction of our visual image. [...] These two assumptions truly imply in a bold abstraction of reality.

[...] The flat perspective construction [...] only becomes comprehensible, indeed, from a conception (very particular and specifically contemporary) of space, or if preferred, of world.’

From a particular and specifically contemporary conception of world... Let us pause a while with this statement. If we join this with what has been said in relation to Seeing is Creating, and if we believe what we see, then we could say that Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing. And from this standpoint, would it be possible thinking – in reverse – that we believe in what we create since we create what we see? What if the dominant discourse of a time created what we have to "See" and the ways for seeing it, so we would then believe it, and since we believe it we validate it, that is, we re-believe it? Would the reproduced images – such as painting, photography, and cinema – be the responsible for teaching us to "See"?

Let us analyze some of the different representation systems used throughout the Western art history and see if we can deepen in this idea.

The Cavalier Perspective was a way of representing objects in a plane as if seeing them from above, that is, considering the observer located above them. The term Cavalier dates from the sixteenth century and its origin is military. A cavalier tower is a defensive structure of a castle and is considerably higher than other towers having a large field of vision. But this possibility of seeing from above is something that cavaliers also had. Mounted on their horses, they had a field of vision larger than foot soldiers. And if we think that those living in the heights of castles also had daily access to this kind of vision, would it be malicious thinking that those who financed the pictorial production of that time ultimately financed the representation of their own viewpoint of "reality"? Or did most people have access to that point of view?

Let us now focus on another kind of perspective: the Reverse. This kind of perspective, also called Inverted, was used in Gothic or pre-Renaissance paintings, and consisted in representing objects or people in smaller way in the foreground, and the largest in the background. Or said in another way, objects become larger as they “move away" from the viewer. Consider that from a theological conception of world, where the mediate, the earthly, is considered a step towards life after death as real purpose, paradise becomes a grandiose idea compared to worldly pleasures. And being "God" and life in "the beyond" what had greater importance at the time, it would not be illogical thinking that a visual representation which follows the dominant paradigm show, precisely, with larger size in pictorial-composition plan the figures placed more “way” from the viewer. And hence, the “closest”, in analogy to the earthly, the sensible, are represented on a smaller scale than the former ones.

Following this hypothetical logic, the Renaissance, product of Humanism dissemination, marked a shift in the conception of the Man and the World. Anthropocentrism replaces Theocentrism, the Man is now the measure of all things and the human reason acquires a supreme value. In painting, a representation system develops according to that time: the Central Perspective and the concept of painting as a "window to the world." A new way to "Seeing". From "inside" and "through" (Perspicere), obviously.

This new world view, taking man and especially reason as center warranted a radical change in the compositional system used in the Middle Ages. And this radical change reverts the proportions of figures within the composition plan. Now, what is closer becomes more important. What if it was because figures located "closer" in the composition plan are represented as larger, and in contrast the "more way" is represented on a smaller scale? Figure and background continue competing, only with reversed roles.

And if every time generated a system to represent its "reality", we might think that such system not only exposed such "reality" but also taught how to see it. And if Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing we could, by following with this reasoning, infer that those who controlled the means of visual production ultimately controlled the means of " Reality Production".

But what happens when, nowadays, these images are reproduced and disseminated – via the Internet – beyond their original containing contexts? Do they teach "Seeing" or are they (re)read?

In the punctual case of Performance as an artistic discipline, where the body is presence and what spreads afterward are records of what happened in such action, can we think such images would charge presence in themselves, displacing the body that served them as a source? And what happens when the image that replaced the body is now replaced by a new image that, in turn, is imago of another and another etc.?

New technologies, new virtual spaces as the Internet, made it possible. They imposed it. And without a body – or at least without the body as it was considered until recent years – a new matter without matter, a new Body, virtual, began making itself present on the scene. A virtual space ruled by laws different of those for the space in which we are. Where objects do not depend on physical laws for their composition or perception, nor the paratexts that "contain" them. Where their characteristics are given by the concept of "Ubiquity" and "Remote Presence". Where the speaking uses terms as "access", "enter", "connect", "being Online". Terms that refer to the feeling of entering this virtual space each time one is in front of a computer connected to the Internet. Now without Gods or bodies, because everybody is God. Because the term Ubiquitous, which comes from the Latin ubīque, means "everywhere". The same term used as an adjective attributable to the Judeo-Christian God, pointing to its ability to be present everywhere at the same time. The omnipresence of this past God, who without body, competes daily with thousands of people that leave their corporeality, or in any case, expand it in a new and broader concept of Body and Space.

‘Although cyberspace is usually represented spatially, it is not a place or a thing. It consists of a set of electronic synapses exchanging millions of bits of information over telephone lines or optical fibers connected by computer networks. It is not within the machines or in the fabric or network formed by their interconnections: it is an intangible territory accessed through tangible means.’ (BONDER, 2002, p.29)

What if Space was not what we see, but what we see is Space? ...

Performance

‘All communication has a content aspect and a relational aspect such that the second classifies the former and is therefore a metacommunication.’ (Watzlawick, Beavin y Jackson, 1981, p.56)

‘It is not possible not to communicate.’ (Watzlawick, Beavin y Jackson, 1981, p.52)

Is it possible not to represent?

The Body in Performance

In Performance, the artist as subject becomes object, and his body – territory of meanings – on a deployable map that will transcend it, "touching" people who observe it and integrating them to the action. The individual body becomes Body, that is, transcends the limits of its history by embracing the personal history of each one of those present, thus becoming a collective Body. From a beginning, the body we are born with will be in contact with Others and, from the experiences arising from these meetings, it will form Body. That is, it will involve the sum of the organs plus the sum of all the experiences arising from contact with other Bodies. It will be, first of all, relation, and in Performance is the opportunity to activate this potential of relation through empathy, which is nothing but an update of the organism-turned-into-Body’s memory.

Space in Performance

Body that affects a space that affects a body

Space ≠ Place

A space is known. A place is recognized.

A place is a space previously explored and experienced. Loaded with emotions, a place is closer to being a "conceptual space" than a physical one. Nothing will ever be the same since subjectivity crosses it.

The places are crossed by the actions that take place on it. And at this point a question arises. Is the place crossed by action or the action crossed by place?

Let us think of a house. Any house. Its physical space is delimited, obviously, but not only by walls. It is also delimited by the functions of by each space, or by the actions performed in them. And each space in turn determines what is or not allowed to do there. For example, I can go to a friend’s house and urinate at the kitchen but I will surely receive a complaint about it. There is a saying "A place for everything and everything in its place." Is it as sure as it is said? Or can some actions enable certain places to change of space?

The patio of a house could be the place of recreation for its residents, but if I decide roasting some vegetables there, this patio will turn – temporarily – into the place of kitchen.

Can we conclude then that one of the characteristics of places is their ability to change of space?

Performance as articulator of subjectivities and producer of realities, has the ability to create6 places. An action defines or originates a place, temporarily transforming what was before a space. And in the case of Performance, such space can become a place of art, place of privacy or place of reflection among many other possibilities.

And what happens when in Performance, the body which is support for work, is mediated and distanced from other bodies, becoming Body and renouncing its materiality? What happens to the body when technology enables the step from presence to Telepresence?

Let us mention, as example, an Performática Installation I carried out in September 2010 in the city of Recife, Brazil, in the context of visual arts festival "SPA das Artes" and that I titled "[In] Secure Spaces". At that time, and working with Rayr Dos Santos Silva as "informatics and technology support", and Luis Cavalcanti as a mason, I reflected on the insecurity expressed by the mass media. Insecurity converted by such media into "sensation of insecurity" against which society responds by isolating and enclosing the "menacing" in prisons and asylums, while distancing itself by building closed and exclusive spaces where only few can enter. The cement cage and the gold cage. Two variants of enclosure, two sides of a same coin.

In that work I reflected that, in an increasingly frequent way, we are losing our interpersonal relations. The situation itself is disturbing. We are distancing ourselves and the "Other" is a stranger with whom it is better not having "contact".

Similarly, telecommunications have helped displacing personal communication. Phones, text messages, e-mails. Less and less people speak "face to face". Bodily is displaced by virtual. An invisible wall separates us. In "[In] Secure Spaces" this wall becomes visible and the metaphor results an effective enclosure.

Within the "House of Culture" in Recife, a former prison turned into shopping center for tourists, Cavalcanti built with bricks and cement four walls, locking me in a space of 1.30 x 1.80 meters. I stayed inside that small space for a period of three days.

No windows or doors, the only possible communication was through a computer connected the whole time to the Internet. Three days broadcasting live through streaming7, using a webcam and communicating with people through chat. Three days interacting virtually until being released, paradoxically, by the same person who locked me up; by the "Other" from which I was distancing myself.

On the outside, on one side of the construction, a second computer was installed and configured to connect only to the Streaming. Thus people who passed by could choose to see the "[In] Secure Space" from the outside or sit at the computer and, through the transmission, look inside and interact with me via chat.

During the three days I did not use spoken word, communicating only by chat. Most of the large number of people who interacted with me there just wanted to know why I was doing that. They also questioned me on basic needs such as food and where to urinate or defecate. Really few kept conversing, between them and with me, about the proposed theme of virtual communications and distance of bodies. But the remarkable thing was the big difference between those who interacted from the computer located next to the "[In] Secure Space" and who did it by distance, that is, from other cities or countries. While the these latter ones patiently waited to be answered, given the large number of people asking and my inability to answer them all at the same time, the former ones, those whose bodies were present at the same location as the installation, mostly complained about not being answered, in some cases arguing "answer us, we came all the way here to see you and you ignore us." It even happened that sometimes, when I could not handle the tiredness and fatigue of being in front of the computer for so many hours in multiple simultaneous conversations, and I wanted to lie down on the ground to get some rest, some of these people started beating violently the walls. And one of them even wrote in the chat "Get up you lazy, we came here to see you and you are lying down". In those moments I had no choice but rejoining and returning to the computer to answer their questions. It seemed that behind the computer screen, what was observed was not a person but entertainment software.

The moments corresponding to the opening hours of the House of Culture were precisely the most tense and stressful of the experience. Thus, as if it were a job, from 9 am to 19 pm my life turned into a spectacle sometimes sadistic in which I had to meet the visitors demands, while after closure and at night the communication level became pleasant, and along with those Others the physical distances seemed crossed, sharing the solitude of so many cages.

Moments before the release, I changed the camera in the corner of the construction for that in my computer. The first, with a larger field of vision, allowed grasping the space from a wider upper angle, creating the feel of surveillance camera showing a person, of whom one could only see the head. A quasi-anonymous image... an almost blurry face. But for the release, the camera from the computer (which captured a frontal plane of the wall) allowed not only viewing "up close" the moment when the mason’s chisel and hammer broke the bricks opening a gap to free me through. By the same gap, it would transmit live the outside... to those who, from outside, through their monitors, were seeing that “inside”.

A friend, physically present at that moment, would tell me later he was struck when realized that many people there chose to watch the whole releasing process observing from the computer located next to the wall instead of seeing the mason in real life breaking the bricks with chisel and hammer. Only when my body was shown on the outside they stopped paying attention to the transmission.

Already released, the camera followed transmitting for one day, so that when someone curious peered through the hole, he or she was in turn relayed by the webcam and seen, among other monitors, through the one connected to the second computer, just half a meter away from the construction. Thus while people stuck their heads and partially entered "[In] Secure Space" they were been "virtualized", creating the paradox of a third place or space. The actual (the person and the building of bricks and cement), the virtual (transmission via webcam) and the crossing of both, where the viewer or spectator present at the scene could simultaneously see "a body without a head" and "a head without a body” depending on observing the present body or through the monitor.

The day after of been released, when I came to start disassembling the installation, I found two little girls playing with it, which let me understanding an issue I had not even imagined. The temporality and its possible ramifications. Their game was to peek through the hole in the wall, dance in front of the camera and then run to the second computer, 2 meters distant from them, and as a result of the delay, watch themselves, while others, stucking their heads in the hole, dancing, and then disappearing from the screen. In a single act they were engines of action and spectators of themselves. "They" and "Others" at the same time. The delay in transmission thus created a temporal-spatial paradox. They, who 5 seconds before were jumping in front the camera in a present time and space, were now duplicated in a virtual space and time. And I prefer designating it with the name of "virtual" and not "represented", since in the case of the transmitted image – while reproduction was not previously recorded, re-presented, but "live and direct" transmission – it was the delay that allowed the coexistence, in the same present time, of these two times and spaces. And if what characterizes and differentiates the present-actual from the represented-updated is just the character of transitory, ephemeral, then it was facing a third time and space: the Virtual.

The space of body in the space of Body?

The "Body", released from the matter to which it was referred as a body, was again trapped in the ways of "Seeing" it, conditioned by those controlling the image reproduction devices; that is, those who – based on the premise that Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing – were able to "produce Reality". With the arrival of new technologies this "Body" is once again released, but now from the unambiguous construction of a time and space proper to a same context and paratext. Now, with the use, among other tools, of Streaming, different observers in different contexts have the potential to (re)create what is seen according to their own ways of "Seeing".

Figure 1, 2, 3 – Event Espacios [in] Seguros. Source: Personal Archive, 2010. (authors: Enaile Lima, Zmário Peixoto, Juan Montelpare, Santiago Cao)

And if who makes the cuts, editions (the representations) is considered author of what is represented, what happens when new technologies put those other observers as co-creators of what is seen? We might think here that these new technologies favor the invention of authorship dilution, even without the intention or attempt to avoid it.

6I choose the word "create" instead of others such as "generate" or "produce" following the argument made in relation to "Seeing is Creating and Creating is Believing."

7Streaming is a data flow in real time. It means that whoever transmits via the Internet will be able to do it "live" and to a large number of spectators who in turn will watch such transmission without being seen. That is, the image and audio transmission occurs unidirectionally, in a way similar to traditional TV, with the innovation and added feature of a chat that allows such viewers to interact (both among themselves and with who is transmitting) through written comments.

Not expecting to address a judgment on the uses of new technologies applied to art and on the new place the "Body" occupies in this "Production of Reality", I wonder what would happen if one day the physiological materiality of the body was finally displaced in favor of other materialities which, as support for image, adapt better to the new ways of "Seeing".

Bibliography