Design colaborativo de comportamentos para ambientes interativos

Gabriela Carneiro é Arquiteta e Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Desenvolve projetos e ministra cursos e oficinas que exploram a incorporação da tecnologia digital no design de objetos e ambientes. Pesquisadora na FAU-USP no qual trata dos processos de design de espaços e edifícios interativos.

Gil Barros é Arquiteto e Mestre em Engenharia Elétrica. Tem experiência na área de Design de Interfaces, Arquitetura de Informação e Usabilidade. Pesquisador na FAU-USP, onde propõe uma técnica de esboços para o design de interação.

Carlos Zibel é Arquiteto, Designer, Artista e Doutor em Estruturas Ambientais Urbanas. Professor Associado na FAU-USP junto aos Cursos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo e de Design. Pesquisador e vice-coordenador científico do Núcleo de Pesquisa em Tecnologia da Arquitetura e Urbanismo (NUTAU) da Universidade de São Paulo (USP).

Como citar esse texto: CARNEIRO, G.; BARROS, G.; ZIBEL, C. Design colaborativo de comportamentos para ambientes interativos. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 6, dezembro 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus06/?sec=4&item=8&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 15 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Este artigo aborda características do processo de design de ambientes interativos. Especificamente analisa um workshop participativo cujo resultado forneceu insumos para a criação do ambiente interativo projetado para a sede de uma produtora digital. O caráter inovador do espaço demandou um processo diferenciado no qual os clientes e funcionários da empresa foram elementos chave no fornecimento de informações para o projeto. Para facilitar a conversação durante o workshop foram aplicados os i|o cards, um conjunto de cartões que representam elementos estruturais e conceituais fundamentais para este tipo de espaço. O artigo apresenta os fundamentos teóricos do projeto, a metodologia utilizada, descreve o workshop e analisa os resultados alcançados.

Introdução

Inúmeras possibilidades se abrem quando o design de ambientes e edifícios incorpora sistemas computacionais em sua estrutura. Segundo os pesquisadores Anna Vallgarda e Johan Redstrom (2007, p. 513, tradução nossa), “recentemente, inovações tecnológicas, tais como os materiais inteligentes e os recursos computacionais embarcados começaram a influenciar o design em áreas emergentes tais como os tecidos inteligentes e a arquitetura interativa”1. Deste modo, a tecnologia digital vem sendo incorporada a ambientes e edifícios, de forma a efetivar a inclusão de aspectos interativos e dinâmicos na forma e percepção do espaço. Como resultado, a programação digital de características efêmeras do ambiente construído, tais como movimento, som e luz, passa a ser também objeto de design.

A arquitetura interativa explora conceitos relacionados à ubiquidade e onipresença da tecnologia digital na sociedade contemporânea. Uma prática resultante de um contexto no qual “estas duas tendências – o acréscimo massivo de poder computacional e a expansão do contexto no qual colocamos esse poder em uso – sugerem que precisamos de novas formas de interação com os computadores; formas que sejam melhor conectadas com nossas necessidades e habilidades”2 (DOURISH, 2004, p. 02, tradução nossa). Isto, somado ao barateamento de componentes e o desenvolvimento de sintaxes de programação mais simples e acessíveis, faz com que, cada dia mais, arquitetos e designers se apropriem desta linguagem e explorem as possibilidades oferecidas pela mídia digital. Bill Moggridge (2007, p. 639, tradução nossa) completa esta constatação ao afirmar que “tudo isto se combina para indicar uma maneira futura que conecte o físico e o digital, e que nos ofereça a chance de projetar interações cheias de riquezas de forma e movimento, libertando-nos do sentimento de estarmos limitados por nossos dispositivos computacionais”3 .

Este campo interdisciplinar é ainda recente e cheio de possibilidades, sendo que a forma mais conhecida de aplicação da tecnologia digital no espaço ainda é aquela na qual controle e economia de recursos são as questões centrais. Michael Fox e Miles Kemp (2009, p. 18, tradução nossa), autores do primeiro livro dedicado a delinear a arquitetura interativa como uma área específica de atuação, comentam que “até recentemente (...) a noção de inteligência no contexto dos ambiente interativos orbitava em torno de um sistema de controle para tudo” e que “ ambientes interativos são definidos como espaços nos quais a computação é continuamente utilizada para melhorar atividades corriqueiras”4 . Porém, para vários arquitetos e designers preocupados em explorar o rebatimento das características do universo digital no espaço físico, esse impacto vai muito além.

Em entrevista recente, o designer de mídias Joachim Sauter (2011), fundador e diretor do ART+COM, descreve a inovação trazida pelos espaços interativos a partir de duas perspectivas: a possibilidade de interação direta com o espaço e de adição de qualidades comportamentais simbólicas ao contexto. Em relação à primeira, a disseminação de sensores e atuadores no espaço permite que este altere suas propriedades físicas e estruturais a partir do comportamento habitual das pessoas, ou seja, as pessoas podem interferir nestas características mesmo sem terem a intenção, simplesmente por estarem presentes, conversar umas com as outras ou se deslocarem no espaço. A segunda perspectiva diz respeito a conteúdos que podem estar presentes nos comportamentos projetados, ou seja, à camadas simbólicas dinâmicas que podem ser adicionadas ao espaço. A tecnologia digital adicionada ao espaço físico permite variadas possibilidades de associações, o que possibilita a criação de metáforas abertas a interações em tempo real, que nos façam refletir sobre o mundo contemporâneo. Assim, no contexto deste artigo, o termo arquitetura interativa refere-se aos espaços que possuem estas duas características: a interação direta e a camada simbólica, implementadas por meio da computação digital.

Neste contexto, Conceber um espaço cujas características incluam a possibilidade de interação com as pessoas que ali desenvolvem suas atividades cotidianas, coloca ainda duas questões importantes. A primeira é a falta de referência sobre projetos de ambientes interativos. Por exemplo, ao projetar o espaço físico de um escritório, existem vários exemplos e estudos feitos, basta folhear uma revista ou um livro específico sobre o assunto, mas isto não ocorre com os aspectos interativos do ambiente. A outra questão relaciona-se com a ideia de participação no processo de design. Por ser um aspecto do projeto no qual as possibilidades ainda são muito abertas, as pessoas têm dificuldade de enxergar o que é possível fazer. Dada a indefinição deste tipo de projeto, tornou-se importante envolver o usuário final ao longo do seu desenvolvimento.

Tendo em vista a otimização desta participação, a elaboração de workshops criativos torna-se ferramenta importante para extrair dos clientes e usuários informações que eles não seriam capazes de elaborar sem a introdução de suportes específicos. Logo, ao preparar um workshop, o designer imagina diversas possibilidades para estimular os participantes a organizar suas ideias e, assim, obter insumos para ir além e conseguir idealizar outras possibilidades a partir daquilo que é colocado na atividade. Brian Lawson (2005, p. 201, tradução nossa) evidencia esta postura ao afirmar que “ainda outra maneira de desafiar a direção de nosso pensamento é interagir diretamente com outras pessoas. Técnicas, tais como brainstorming e synectics, contam com o pressuposto que um grupo de pessoas não tendem a ver um problema da mesma maneira, e que se a variedade natural de indivíduos puder ser controlada o grupo provavelmente será mais produtivo”5 . Deste modo, um workshop pode ser pensado para agilizar a discussão e o refinamento de problemas.

Elaborar um workshop significa montar um contexto para estimular a conversação e troca de informações, de maneira direcionada, entre diferentes grupos. Os grupos, segundo Lawson (2005, p. 242, tradução nossa), “atuam não apenas como uma coleção de indivíduos, mas também, de certa forma, vão além dos talentos individuais do coletivo”6 . Para otimizar este processo, além da reunião de diferentes participantes, é importante pensar em ferramentas que estimulem a conversação entre eles, levando em consideração suas diferentes vivências pessoais e formação profissional.

Um exemplo interessante de ferramenta utilizada em sessões criativas são os Method Cards (IDEO, 2002), desenvolvidos pelo escritório IDEO, uma renomada empresa americana que fornece consultoria voltada para o desenvolvimento de produtos inovadores. Trata-se de um conjunto de cartões nos quais estão descritos os principais métodos de pesquisa utilizados pela empresa em seus projetos.

Segundo Bill Moggridge (2007, p. 669, tradução nossa)

A ideia dos Method Cards é fazer um grande número de diferentes técnicas serem acessíveis a todos os membros do time de design e encorajar uma aproximação criativa à busca de informações e intuições na medida em que seus projetos evoluem. A intenção é fornecer uma ferramenta que pode ser utilizada flexivelmente para ordenar, navegar, procurar, espalhar e empilhar7 .

Logo, esse é um exemplo que deixa claro a dinâmica trazida pela utilização de cartas como suporte de discussões em workshops criativos.

Neste sentido, por ter um componente digital, o design de ambientes interativos possui um aspecto particular deste tipo de objeto: a imaterialidade de grande parte de seu sistema.

Dan Saffer (2007, p. 170, tradução nossa), descreve estes objetos e diz que:

Produtos digitais se parecem um pouco com icebergs. A parte que pode ser vista (a interface) é realmente apenas a ponta; o que está embaixo da superfície, o que não pode ser visto, é onde a parte principal do design de interação se encontra: as decisões de design que o designer fez e as estruturas de suporte técnico que tornam a interface uma realidade.”8

Como grande parte do projeto destes produtos diz respeito ao seu comportamento e funcionalidade, o desenvolvimento de ferramentas que representem elementos não-tangíveis deste sistema podem servir como apoio para conversações entre diferentes participantes de uma dinâmica em grupo.

Diante do contexto delineado, sugere-se que a elaboração de workshops em conjunto com ferramentas específicas para facilitar a conversação durante as atividades podem apresentar-se como meio eficiente de projetar espaços interativos expressivos. Esta hipótese relaciona-se, sobretudo, com projetos cujo foco é o desenvolvimento de comportamentos dinâmicos e simbólicos entre o espaço e as pessoas. A partir deste ponto de vista, este artigo apresenta o estudo de caso de uma dinâmica participativa utilizada no desenvolvimento de um projeto de ambiente interativo para a sede de uma empresa.

Ambiente interativo D3

O ambiente interativo explorado neste artigo foi projetado para ser sede de uma produtora digital, empresa que trabalha em conjunto com agências de publicidade para produzir aplicativos e web sites (Figura 1). O fato da empresa trabalhar com diferentes mídias estimulou a concepção de um espaço que refletisse ao máximo as atividades e processos criativos que ali ocorrem. Deste modo, a presença da interação e o desenvolvimento de seu sistema justapôs-se ao desenho das formas, à escolha das cores e dos materiais que compõem o espaço.

Figura 1. Foto do ambiente final, resultado do processo de criação descrito neste artigo (Foto: Fran Parente).

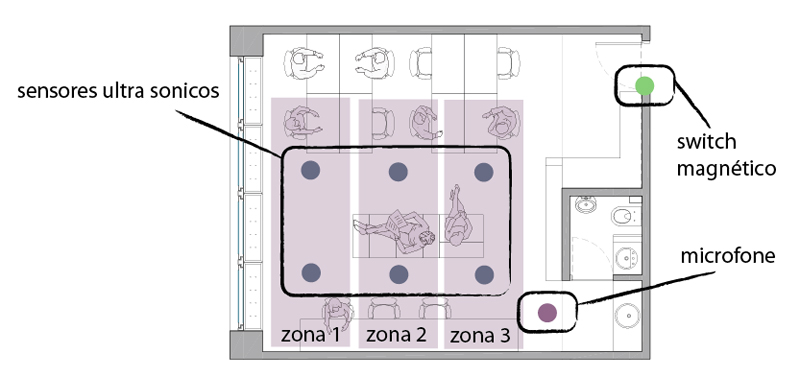

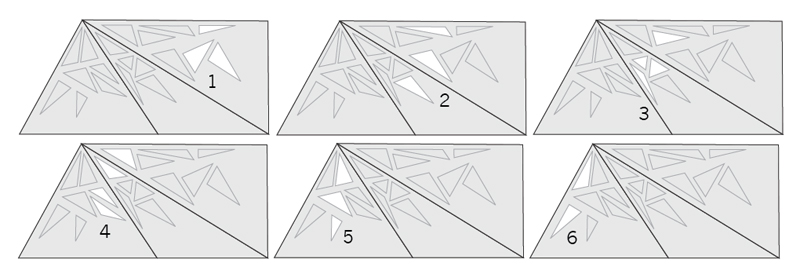

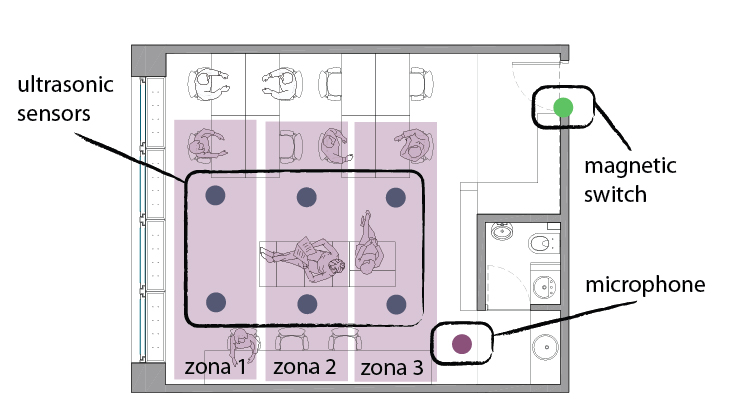

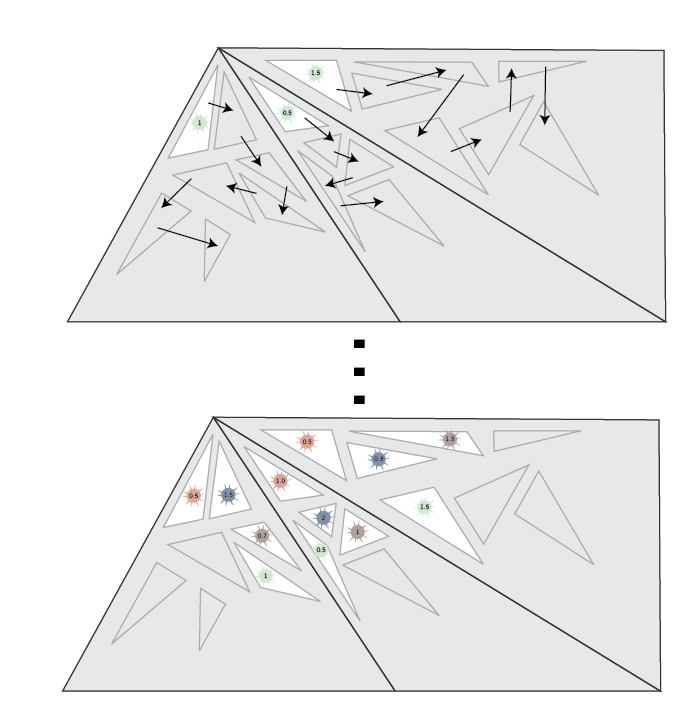

A intenção do projeto foi elaborar uma aproximação holística na qual a mídia digital esteve presente desde os primeiros rascunhos. Nestes esboços já foram previstos padrões luminosos em uma das laterais, sendo que seu desenho seguia a linguagem adotada para toda a marcenaria do projeto, baseada em triangulações irregulares. Os padrões são compostos por 25 triângulos luminosos, visíveis apenas quando acesos. Em parte do espaço optou-se por deixar aparente a estrutura original do espaço, fazendo com que os sistemas elétrico e hidráulico mostrem sua presença. Nesta estrutura também foram conectados os sensores que captam informações sobre as atividades que ali ocorrem (Figura 2).

Este ambiente explora as duas camadas de interação descritas por Sauter (2011). Da mesma maneira que as pessoas alteram propriedades físicas do espaço por meio de sua movimentação, elas passam também a entender um pouco mais dos hábitos e atividades que ali ocorrem. Além disso, trata-se de um comportamento que pode ser aberto e redesenhado, pois foi disponibilizado via internet uma forma de acesso para todo o sistema (triângulos luminosos e sensores) permitindo assim que outras possibilidades interativas sejam futuramente desenvolvidas pelos usuários.

Figura 2. Pessoas trabalhando no espaço com o painel luminoso funcionando ao fundo (esq) e detalhe de um dos sensores ultra sônicos acoplados na estrutura aparente do teto (dir). (Fotos: Fran Parente).

Desde o início deste projeto, a intenção era que o processo criativo acontecesse de forma horizontal, com envolvimento e troca constante entre as diferentes partes envolvidas. Portanto, além de reuniões periódicas para apresentação do andamento do projeto, foi elaborado um workshop criativo específico para a finalização conceitual do projeto. O objetivo do workshop foi levantar informações relevantes sobre as atividades da empresa e expectativa de clientes e usuários sobre a apropriação do espaço, que serviram como insumos para a escolha dos sensores e para o design do comportamento a ser implementado no ambiente.

O Workshop

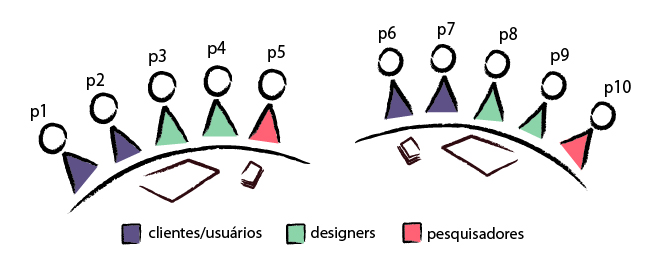

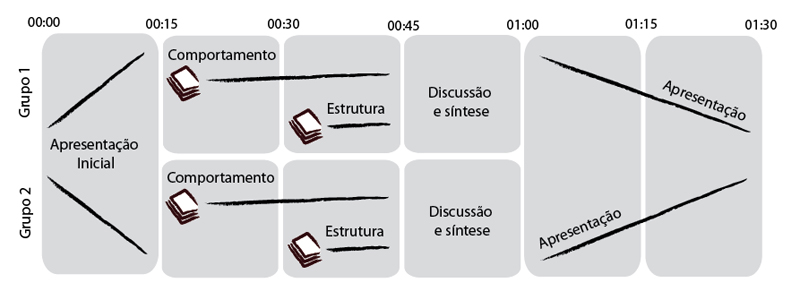

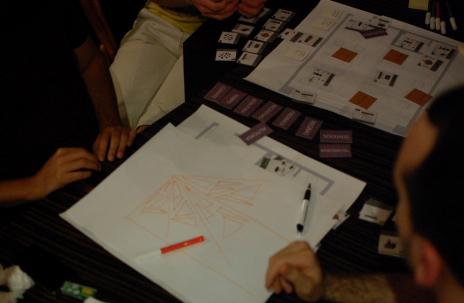

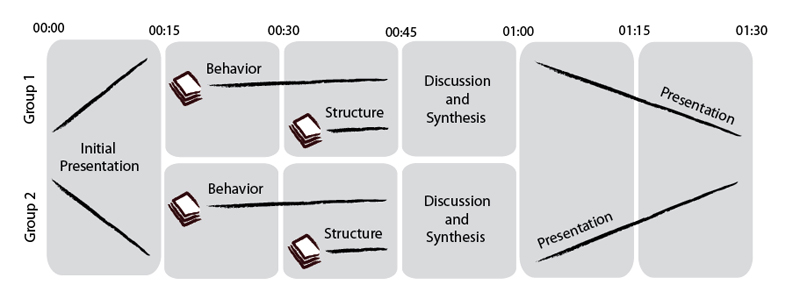

O workshop foi uma atividade única, controlada, e com a duração de uma hora e meia, elaborado e mediado por um dos arquitetos responsáveis pela concepção do projeto. Ele encarregou-se da cronometragem e direcionamento das atividades e discussões, sem o intuito de intervir diretamente no conteúdo abordado pelos participantes. Além do mediador, o workshop contou com a presença de dois representantes dos clientes (usuários), dois funcionários da empresa (usuários), três arquitetos, um engenheiro elétrico e dois pesquisadores convidados, num total de 10 participantes distribuídos em dois grupos conforme apresentado na Figura 3. O dois grupos foram formados com o objetivo de equilibrar as funções que os participantes exercem no projeto como um todo.

Figura 3. Distribuição dos dez participantes nos dois grupos formados para o workshop.

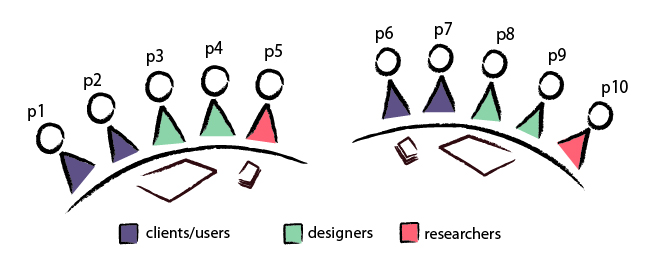

Com a parede de triângulos (output) já instalada, o objeto de discussão foram os sensores que seriam utilizados para captar as informações (input) e os comportamentos possíveis, ou seja, como os dados afetariam os triângulos luminosos. Os dois grupos debateram sobre o espaço e os hábitos e comportamentos das pessoas, relacionando-os com possíveis sensores e com as interações que poderiam acontecer no ambiente. Como material de suporte foram utilizadas plantas do espaço na escala 1:50 e os i|o cards (CARNEIRO, 2010), um conjunto de cartões desenvolvido para estimular a conversação e troca de ideias durante a concepção de sistemas interativos.

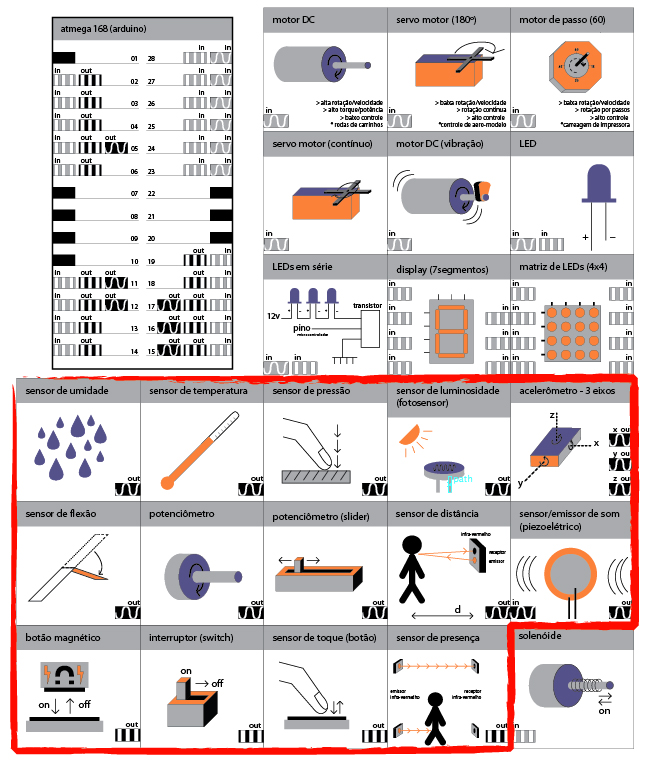

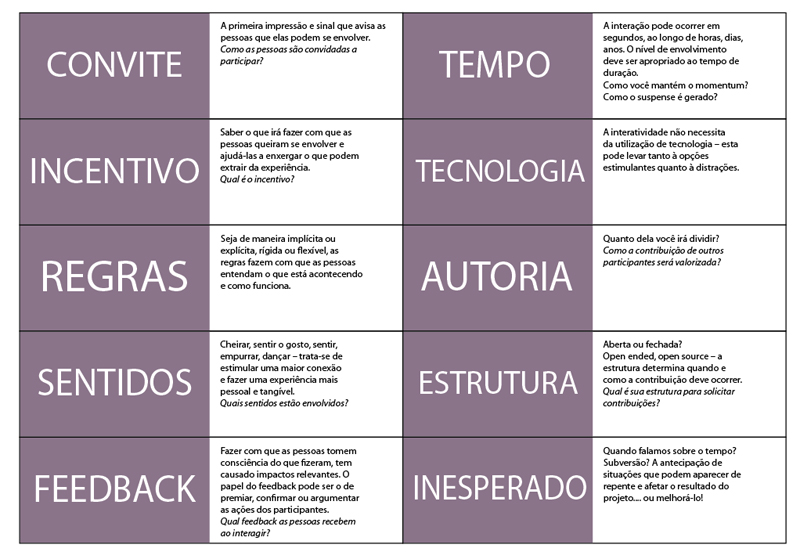

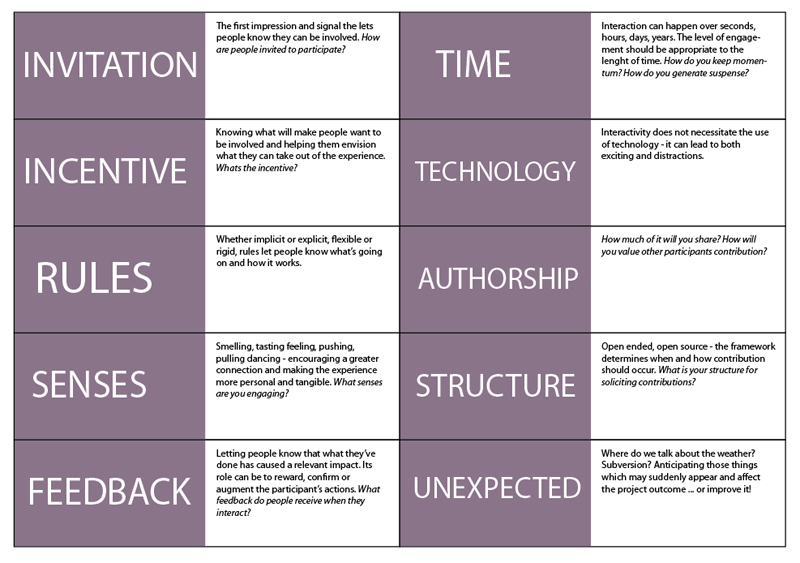

Os i|o cards são divididos em dois grupos: um trabalha questões estruturais do sistema interativo e o outro aborda preocupações conceituais para a criação de experiências interativas. O primeiro grupo contém representações gráficas do microcontrolador e dos principais sensores-atuadores que um iniciante em computação física tem que conhecer, com a indicação do tipo de informação que fornecem (analógica ou digital), conforme apresentado na figura 4. O segundo grupo possui em uma de suas faces os conceitos importantes para o desenvolvimento de comportamentos interativos focados na experiência das pessoas e, na outra face, breves explicações destes conceitos (Figura 5). Para este workshop, o grupo conceitual foi adotado na totalidade, enquanto das cartas estruturais apenas os sensores foram utilizados, de forma que as representações dos atuadores e o microcontrolador não foram utilizadas.

Figura 4. Cartões estruturais dos i|o cards. Os cartões utilizados neste workshop (os sensores) estão contornados em vermelho.

Figura 5. Cartões conceituais dos i|o cards.

Quanto à dinâmica do workshop, ambos os grupos iniciaram a dinâmica com as plantas do ambiente em mãos. As cartas foram então distribuídas de maneira alternada sendo que o Grupo 1 começou a atividade com os elementos estruturais (no caso, apenas sensores) e o Grupo 2 com os conceituais. Depois de 15 minutos o restante das cartas foram distribuídas para os dois grupos. Desta maneira, um grupo foi forçado a começar a discussão pela questão técnica e o outro pela experiência. Após 30 minutos de discussão, os grupos tiveram um tempo para organizar as ideias para finalizar a atividade com a apresentação das mesmas, seguida de uma discussão coletiva. Na Figura 6 é apresentada a distribuição das atividades no tempo. No final da sessão, com o intuito de avaliar a atividade, foi requisitado aos participantes que redigissem e enviassem por e-mail sua impressão individual sobre o workshop.

Figura 6. Distribuição das atividades do workshop ao longo do período de uma hora e meia. Detalhe para a sequência alternada de distribuição dos i|o cards entre 00:15 e 00:45.

Em relação à utilização do material de suporte, houve um consenso entre os dois grupos de que é mais significativo iniciar a discussão pelos conceitos antes de falar sobre a tecnologia. Ao relatar suas ideias, o Grupo 2, que recebeu primeiro as cartas estruturais, deixou claro logo no início que preferiria ter começado a discussão pelos conceitos (“o que queremos com o espaço”) para depois passar para a parte técnica (“como realizar os conceitos escolhidos”). Eles relataram que mesmo tendo os sensores em mãos, foi mais natural começarem a discussão pelos conceitos e motivações. Para este grupo, no momento em que os conceitos foram entregues, eles apenas checaram se faltava alguma coisa.

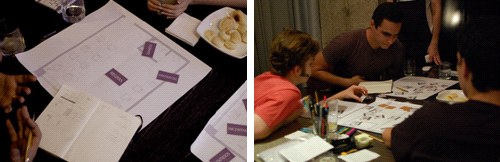

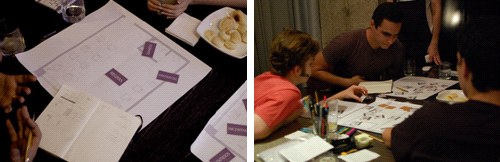

Para o Grupo 1, receber os conceitos logo no início ajudou a direcionar a conversa (Figura 8). As palavras criaram um recorte interessante para as discussões, porém não foram utilizadas como uma lista obrigatória de questões a serem resolvidas uma a uma, de maneira que auxiliavam especialmente em momentos específicos, quando o ritmo da conversa diminuía. Segundo relato do Participante 5 “quando o segundo grupo de cartões apareceu, o grupo deu uma manuseada, falou um pouco sobre sensores mas não se ateve muito sobre o assunto e voltou para a discussão anterior (…). Os sensores entraram na discussão, mas na minha interpretação subordinados ao ponto de vista inicial da discussão”9 .

Figura 7. Grupo 1 discutindo os conceitos (esquerda) e no momento que receberam os cartões estruturais (direita).

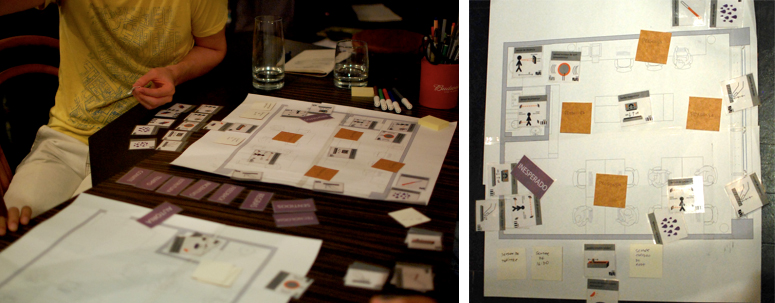

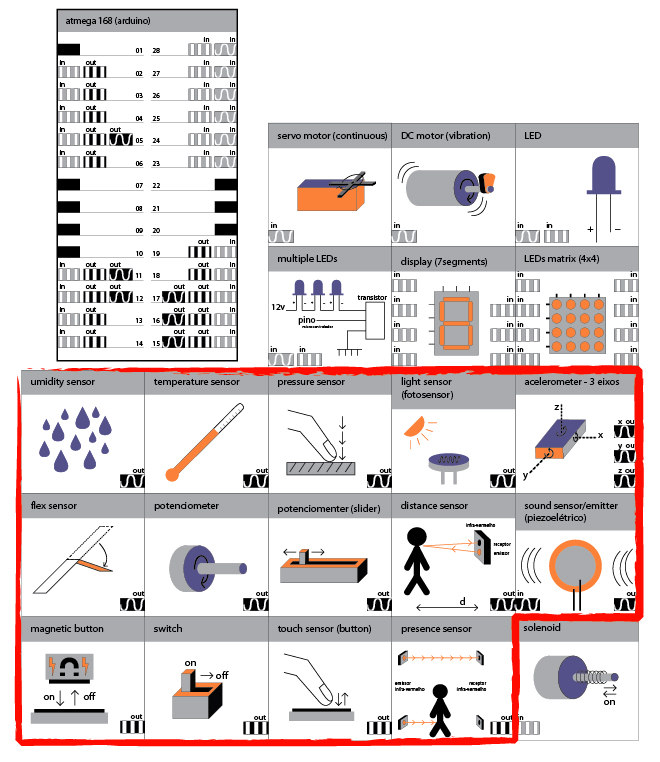

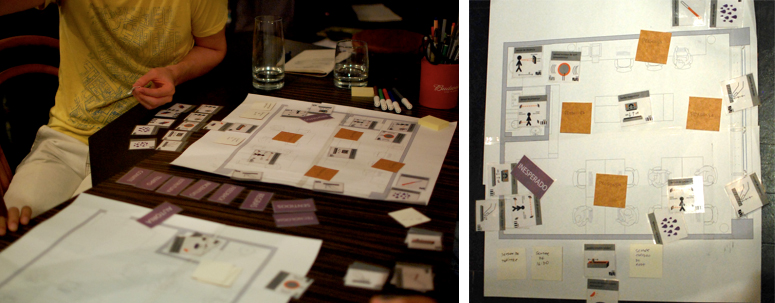

Ainda sobre o material de suporte, observou-se que apenas o Grupo 2 utilizou os cartões estruturais em conjunto com a planta do espaço, sendo que o Grupo 1 se ateve a olhar os cartões e fazer anotações sem incorporar as plantas como suporte de informações. Além das representações disponíveis, o Grupo 2 utilizou também alguns cartões em branco, distribuídos para serem apropriados livremente de acordo com as necessidades inesperadas (Figura 8).

Figura 8. Grupo 2 organizando as cartas na planta (esquerda) e planta pronta para a apresentação final (direita).

Neste caso, o Grupo 2 os utilizou para representar, tanto sensores cuja quantidade de cartões não eram suficientes, quanto para incluir outros tipos de sensores, além daqueles disponíveis nos i|o cards. No geral, a planta do espaço acrescida dos sensores mostrou-se bastante útil para auxiliar na organização e apresentação final das ideias.

Resultados

Como resultado, a dinâmica adotada para o workshop possibilitou uma discussão aprofundada, em um tempo relativamente curto, de diferentes possibilidades para o ambiente. As principais ideias foram sintetizadas pelos próprios participantes e apresentadas no momento final. Para servir de input para o projeto, esta apresentação foi gravada e, em seguida, integralmente transcrita. As ideias foram então sintetizadas e utilizadas para a definição do comportamento padrão do sistema.

A apresentação final o Grupo 2, primeiro a comentar suas ideias, baseou seu discurso em três tipos de interação: eventos, comportamentos e controle. No grupo de eventos destacaram a importância de sinalizar a chegada de pessoas no espaço, de forma que os visitantes percebessem rapidamente que algo diferente aconteceu no espaço com sua chegada. Os eventos incorporariam também jogos acionados no mobiliário. Os comportamentos tratam da reação do sistema, de acordo com o tráfego de dados na rede e movimentação das pessoas no espaço, como se fossem “pegadas” de suas ações. Enfatizaram a importância destes comportamentos terem um componente de aleatoriedade para não ficarem muito repetitivos. Para completar, o controle compreende a possibilidade de ligar, desligar e alterar intencionalmente os padrões luminosos.

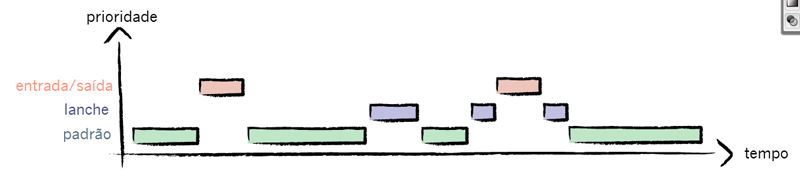

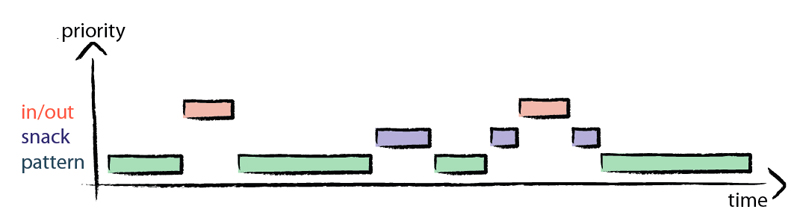

O Grupo 1 enfatizou a questão do cruzamento das interações no tempo, incluindo, tanto reações imediatas, quanto mudanças comportamentais de mais longo prazo. A partir de uma análise direta do comportamento dos funcionários da empresa, colocaram a grande alternância entre os momentos de concentração nos quais estão todos sentados e calados, e os momentos nos quais fica nítida uma agitação geral. No final realçaram a importância de pensar nos níveis de prioridade dos diferentes comportamentos.

Design do comportamento

Após a análise das informações obtidas no workshop, foram definidos os sensores a serem instalados no espaço e sua localização, assim como o comportamento padrão a ser implementado. Além dos 25 triângulos luminosos, o sistema interativo contou também com seis sensores ultrassônicos instalados na estrutura do teto, um microfone na proximidade da cozinha e um sensor para captar a abertura e fechamento da porta de entrada (Figura 9). O comportamento foi implementada em linguagem PHP e pode ser alterado e expandido por outros comportamentos desenvolvidos pelos próprios usuários.

Figura 9. A escolha e distribuição dos sensores no espaço foi realizada a partir das discussões realizadas no workshop.

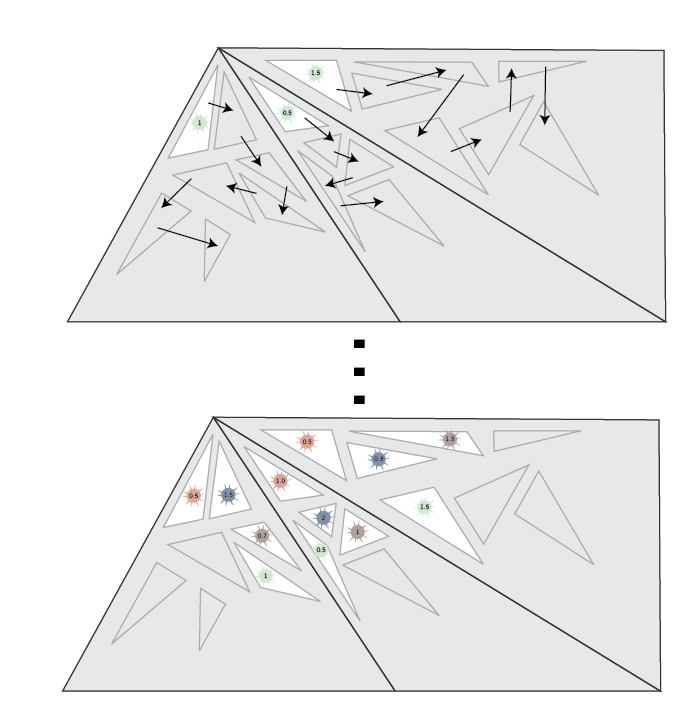

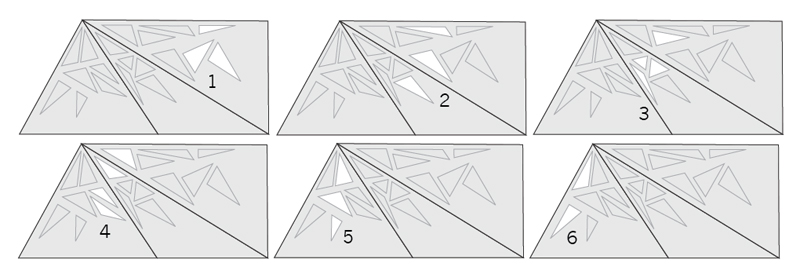

Foram definidas três interações distribuídas no tempo de acordo com seu nível de importância. As interações mais prioritárias se sobrepõem às outras, conforme mostrado na Figura 10. No nível mais baixo encontra-se a interação padrão, que acontece ao longo do dia e é baseada nos valores obtidos pelos seis sensores de distância ultrassônicos espalhados na estrutura aparente do teto. Para esta interação, o espaço e os triângulos luminosos foram subdivididos em três zonas, sendo que a média dos valores dos dois sensores presentes em cada zona determina a velocidade na qual o primeiro triângulo de cada grupo de triângulos piscará. A cada intervalo de 10 segundos este valor é reverberados para o próximo triângulo e o primeiro passa a piscar a partir do valor atual dos sensores. O objetivo é que, com o tempo, cada conjunto de triângulos reflita a ocupação de sua respectiva zona e que o conjunto de todos os padrões reflita de maneira abstrata a movimentação dos seus ocupantes ao longo do tempo (Figura 11).

Figura 10. Representação gráfica da relação entre prioridade da interação e seu acontecimento no tempo.

Figura 11. Interação padrão. A figura superior mostra o primeiro passo, no qual o primeiro triângulo de cada grupo pisca em intensidade diferente (a estrela mostra o intervalo em segundos das piscadas). A imagem inferior mostra a parede após quatro passos. Os valores iniciais vão se propagando pelos triângulos de cada grupo.

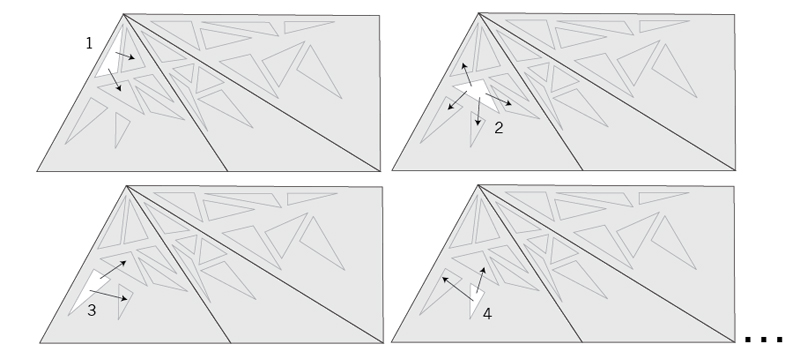

Esta interação padrão pode ser interrompida a qualquer momento pelas duas outras: a hora do lanche e a entrada ou saída de pessoas no espaço, sendo que esta última tem prioridade, ou seja, sobrepõe todas as outras quando acionada. A hora do lanche foi apontada, durante o workshop, como o principal momento de conversa e descontração da empresa, de tal modo que optou-se pela instalação de um microfone na área da copa. Quando o microfone recebe um estímulo pontual grande, ou seja, quando o valor atinge um determinado pico, a interação é acionada. Esta é caracterizada pela brincadeira: apenas um triângulo é aceso e a atualização do valor do microfone determina qual será o próximo a ser acendido. Assim, diferentes desafios podem ser criados pelas próprias pessoas, como por exemplo, uma competição de quem consegue fazer a luz atravessar de um lado a outro em menor tempo (Figura 12).

Figura 12. Interação da hora do lanche. O primeiro triângulo é ligado e o próximo é determinado pelo valor captado pelo microfone.

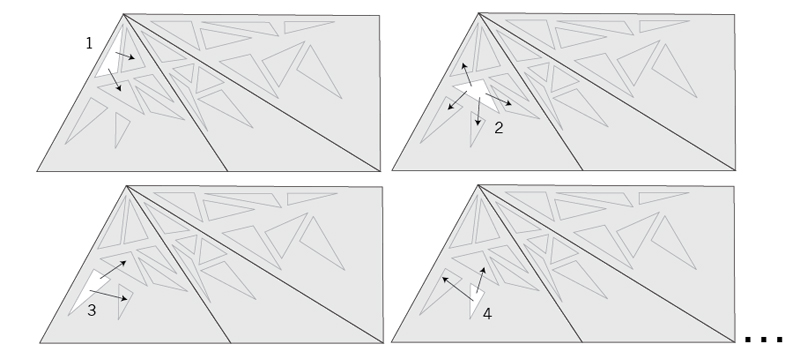

A terceira interação do comportamento padrão é baseada na vontade expressa durante o workshop, de sinalizar quando eventos importantes acontecem, tal como a chegada de visitantes no espaço. Por este motivo, foi instalado um sensor magnético que capta a abertura/fechamento da porta. Quando acionado, um padrão de onda se perpetua em um movimento de vai e vem, que dura até cinco segundos depois que a porta foi novamente fechada (Figura 13).

Figura 13. Interação entrada ou saída de pessoas. Uma vez que a porta é aberta, grupos de triângulos são acionados em um movimento de vai e vem até que a porta seja novamente fechada.

O workshop contribuiu significativamente para o projeto. O envolvimento dos usuários auxiliou no desenvolvimento de um comportamento dotado de significado para os seus usuários quotidianos. Além do alcance do objetivo esperado, vários outros pontos merecem destaque e são discutidos na parte final deste artigo.

Conclusões

O workshop compreendeu questões que vão muito além dos insumos para a criação de um comportamento padrão previsto como parte do espaço na proposta inicial do projeto. Entre outras constatações é importante ressaltar seu papel de gerador de insumos para a definição de um comportamento calcado no uso efetivo do espaço. Neste sentido, convidar usuários para participar do processo criativo não significa dizer que eles irão definir questões, e sim que eles gerarão dados a serem posteriormente considerados pelos designers responsáveis. Como Lawson (2005, p. 90) aponta, é muito importante compreender as demandas reais dos usuários de um sistema ou ambiente.

No caso deste projeto, o workshop teve ainda um papel fundamental em relação ao futuro deste ambiente. Como uma das características do sistema interativo desenvolvido é a possibilidade de intervenções futuras por meio de sua reprogramação, o workshop gerou insumos, tanto para os arquitetos quanto para os próprios usuários. Ideias específicas que não foram inicialmente implementadas podem estimular futuras intervenções. É importante ressaltar que a o desenvolvimento de um sistema interativo aberto – que prevê a possibilidade de alteração – foi uma resposta elaborada pelos arquitetos ao perfil dos clientes e usuários, cujas habilidades incluem a programação de web sites e notável abertura para experimentações com a tecnologia digital. Aqui a arquitetura vai além de seu papel de invólucro e o próprio espaço atua como estimulador de atividades criativas e trocas entre seus usuários.

A participação dos clientes e usuários no processo de design através do workshop, promoveu também o sentimento de apropriação do espaço pelos mesmos. O participante 2 relata que “no final, minha própria percepção do projeto geral amadureceu bastante e agora estou mais empolgada do que antes”10 . Dado o caráter inovador da proposta, a dinâmica auxiliou no processo de entendimento e aumentou a consciência e conhecimento das pessoas que irão usufruir desta espacialidade, no que diz respeito às possibilidades ali presentes.

Um outro aspecto a ser considerado é o subsídio da dinâmica para ampliar o repertório conceitual e prático dos participantes em geral. A mistura de clientes, usuários, arquitetos e pesquisadores forneceu uma base ampla e mista que contribuiu nitidamente para o enriquecimento das discussões colocadas. Segundo o relato do participante 6 “acredito que tudo isto produziu um número incrível de ideias e de ideias para outras ideias.”11

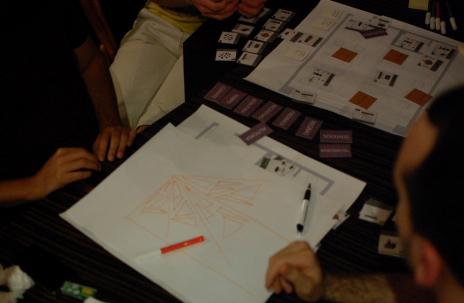

A utilização de material de suporte foi um aspecto essencial para o resultado positivo do workshop. As cartas e plantas permitiram a experimentação prática do processo de design de um espaço interativo, assim como abriram a oportunidade para diversos outros questionamentos e ações. Também teria sido interessante a utilização de suportes materiais para exploração dos padrões luminosos do conjunto de triângulos. Em um dado momento, o Grupo 2 chegou a esboçar estes padrões em um papel, o que constata que pensar em maneiras de facilitar e tornar tangível também este suporte teria contribuído ainda com o resultado final (Figura 14).

Figura 14. Detalhe do Grupo 2 e dos esboços da triangulação da parede que fizeram para auxiliar a discussão.

O projeto para a sede desta produtora digital é fruto de uma nova geração de designers e clientes que almejam um modo alternativo de trabalhar, caracterizado pela experimentação, abertura e colaboração dos processos. Neste caso, o processo de desenvolvimento do sistema interativo justapôs-se ao desenho das formas, à escolha das cores e dos materiais que compõem o espaço, e transpõe nele, os valores cultivados pelas pessoas que o habitam. O resultado é a integração das instâncias física e virtual em um único projeto, de maneira que extrapola o discurso funcionalista que normalmente é associado à tecnologia.

Em um mundo no qual objetos, carros, roupas e ambientes trocam informações com as pessoas e detectam suas ações e atividades, é preciso refletir sobre como ampliar e adicionar novas relações entre o homem e seu habitat. Acreditamos que faz parte da responsabilidade dos arquitetos e designers manipular esta tecnologia de forma a criar ambientes e objetos que inspirem a criatividade e imaginação no cotidiano das pessoas.

Agradecimentos

Agradecemos à Produtora Digital D3 pela oportunidade de desenvolver o projeto. Ao Estúdio Guto Requena e ao i|o Design pelas informações sobre o processo. À FAPESP pelo financiamento da pesquisa que contribuiu com questões conceituais para o projeto.

Referências

CARNEIRO, G. i|o Cards. 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.objetosinterativos.com.br/290/iocards/>. Acesso em: 05 out. 2011.

DOURISH, P. Where the action is: the foundations of embodied interaction. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

FOX, M.; KEMP, M. Interactive architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

IDEO. Method cards: 51 ways to inspire design. San Francisco: William South Architectural Books, 2002.

LAWSON, B. How designers think. Oxford: Architectural Press, 2005.

MOGGRIDGE, B. Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2007.

SAFFER, D. Designing for interaction: creating smart applications and clever devices. Berkeley, CA: AIGA Design Press, 2007.

SAUTER, J. Depoimento concedido em entrevista a Gabriela Carneiro. Berlin: Univeristät der Künste Berlin (UDK), 30 mai. 2011.

VALLGARDA, A.; REDSTROM, J. Computational composites. In: SIGCHI CONFERENCE ON HUMAN FACTOR IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS. Proceedings... San Jose, CA: ACM, 2007.

Collaborative design of interactive environments’ behaviors

Gabriela Carneiro is Architect and Master in Theory and History of Architecture and Urbanism. She develops projects and gives courses and workshops that explore the digital technology appropriation on the design of objects and environments. Researcher at FAU-USP, where she deals with the design process of interactive buildings and spaces.

Gil Barros is Architect and Master in Electrical Engineering . Have experience in the areas of Interface Design, Information Architecture and Usability. Researcher at FAU-USP, where he proposes a sketching technique for interaction design.

Carlos Zibel is Architect, Designer, Artist and Doctor in Urban Environmental Structures. Associate Professor at FAU-USP at the Architecture, Urban Planning and Design courses. Senior researcher and vice scientific coordinator of the Center of Research in Architecture and Urbanism Technology (NUTAU) at Universidade de São Paulo (USP).

How to quote this text: Carneiro, G., Barros, G. and Zibel, C., 2011. Collaborative design of interactive environments' behaviors, Translated from Portuguese by Paulo Ortega. V!RUS, [online] n. 6 [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus06/?sec=4&item=8&lang=en>. [Accessed: 15 July 2025].

Abstract

This article addresses some characteristics of the design process from interactive environments. Specifically, it analyzes a collaborative workshop whose results supplied inputs for the creation of an interactive environment projected for a digital producer central office. The innovative character of the space created the need for a differentiated process in which the clients and the company employees were key elements to provide information for the project. A card set named i|o cards was applied to ease the communication during the workshop. The cards represent the structural and conceptual elements we regard as essential for the design of this kind of space. The article presents the theoretical blueprints of the project, used methodology; it describes the workshop and analyzes the achieved results.

Introduction

Numerous possibilities are opened up when environmental and building design incorporate computational system in their structure According to the researchers Anna Vallgarda and Johan Redstrom (2007, p.513), “More recently, technological innovations such as smart materials and embedded computational resources have begun to influence design, in emerging areas such as smart textiles and interactive architecture”. Therefore, digital technology has been integrated to environment and buildings, in a way to accomplish the inclusion of dynamic and interactive aspects within space shape and perception. As a result, the digital programming of the ephemeral characteristics of the built environment, such as movement, sound and lights, also become an object of design.

Interactive architecture explores concepts related to the ubiquity and omnipresence of digital technology in the contemporary society. A resulting practice from a context in which “These two trends – the massive increase in computational power and the expanding context in which we put that power to use –both suggest that we need new ways of interacting with computers, ways that are better tuned to our need and abilities” (Dourish, 2004, p.02). This added to the cheapening of components and the development of simpler and more accessible programming syntaxes makes, day after day, architects and designers take possession of this language and explore the possibilities offered by digital media. Bill Moggridge (2007, p.639) adds to this statement when he says that “This all combines to indicate a way forward that connects the physical and digital, and offers us the chance to design interactions that are full of the richness of form and movement, freeing us from the feeling of being constrained by our computing devices”.

This interdisciplinary field is still recent and full of possibilities, in a way that the most well-known form of application of the digital technology in space is still the one in which control and resources economy are the central issues. Michael Fox and Miles Kemp (2009, p.18), authors of the first book to outline interactive architecture as a specific actuation area, comment that, “Until recently (…) the notion of intelligence in the context of interactive environments revolved around a central control system for everything” and that “intelligent environments are defined as spaces in which computation is seamlessly used to enhance ordinary activity”. However, for several architects and designers worried about exploring the impact of the digital media in the physical space, this impact goes much further.

In a recent interview, the media designer Joachim Sauter (2011), ART+COM’s founder and director, describes the innovations brought by interactive spaces from two perspectives: the possibility of direct interaction with the space, and the addition of symbolic behavioral characteristics to the context. Regarding the first one, the dissemination of sensors and actuators in the space allows it to change its physical properties according people’s usual behavior, that is, people can interfere in these characteristics even when they do not intend to, simply because they are present, talk to each other or move in space. The second perspective is about the designed behavior content, that is, the symbolic layers that can be added to space. Digital technology associated to the physical space allows several association possibilities, which makes possible the creation of open metaphors and real time interactions that makes us reflect about the contemporary world. Therefore, in the context of this article, the term interactive architecture refers to the contemporary spaces that include these two characteristics: direct interaction and symbolic layer, implemented through digital technology.

In this context, conceiving a space whose characteristics include the possibility of interaction with the people who develop their daily activities there, still sets two important issues. The first one is the lack of references about interactive environment projects. For instance, when designing the physical space of an office there are several examples of studies made, it is all about flicking through a magazine or specific book on the subject. But this doesn’t happen with the digital interactive aspects of the environment. The other issue is related to the collaborative initiative in the design process. Since one of the project’s aspects regard its openness, the possibilities are very open and people still have difficulty to see what can be achieved. Given the lack of definition of this type of project, it was important to involve the final user alongside its development.

Having in mind this collaboration optimization, creative workshops become an important tool to extract from the clients and users information they would not be able to elaborate without the introduction of specific support. Therefore, when preparing a workshop, the designer imagines diverse possibilities to stimulate the participants to organize their ideas and, as a result, he’s able to go beyond his own ideas and use these inputs to imagine other possibilities. Brian Lawson (2005, p.201) highlights this posture when he says, “Yet another way to challenge the direction of our thought is to interact directly with other people. Techniques such as brainstorming and synectics rely on the assumption that a group of people are not likely all to approach a problem in the same way, and that if the natural variety of the individuals can be harnessed the group may be more productive”. Hence, a workshop can be thought to stimulate the discussion and the refine the design issues.

Elaborating a workshop means to set up a context to stimulate conversation and information exchange, in a directed way, among different groups. The groups, according to Lawson (2005, p.242), “act not just as a collection of individuals, but also in a manner somehow beyond the abilities of the collective individual talents”. To optimize this process, besides the gathering of different participants, it is important to think about tools to stimulate the conversation among them, taking into consideration their different personal experience and professional background.

An interesting example of a tool used in creative sessions is the Method Cards (IDEO, 2002), developed by the IDEO office, a renowned American company that provides consultancy for the development of innovative products. They comprise a set of cards in which the main research methods used by the company are described. According to Bill Moggridge (2007, p.669)

The idea of the methods cards is to make a large number of different techniques accessible to all members of a design team and to encourage a creative approach to the search for information and insights as their projects evolve. The intention is to provide a tool that can be used flexibly to sort, browse, search, spread out, or pin up.

Thus, this is an example that elucidates the kind of dynamic activity that can be achieved when cards are used as a discussion support in creative workshops.

In this way, by having a digital component, the design of interactive environments has a very particular aspect: the biggest part of its system’s immateriality. Dan Saffer (2007, p.170), describes interactive objects and says that

Digital products are a bit like icebergs. The part that can be seen (the interface) is really just the tip; what’s below the surface, what isn’t seen, is where the main part of the interaction design lies: the design decisions that the designer has made and the technical underpinnings that make the interface a reality.

As big part of these products’ design is about its behavior and functionality, the development of tools that represent intangible elements of this system may serve as conversations support among different participants within a group activity.

Within the described context, it is suggested that the elaboration of workshops along with specific tools to make conversation easier during the activities, may turn out as an efficient way to design more meaningful interactive spaces. This hypothesis relates especially with projects that are focused in the dynamic and symbolic behaviors’ development between people and space. From this point of view, this article presents the study of a collaborative dynamic case used in the development of an interactive environment project designed to be a company’s main office.

Interactive Environment D3

The interactive environment explored in this article was designed to be the head office of a digital producer, a company that works together with publicity agencies to produce apps and web sites. (Figure 1). The fact that the company works with different media stimulated the conception of a space that reflects, as much as possible, the creative processes and activities that occurs there. That way, the introduction of an interactive layer and its system development was part of the design process, alongside with the choice of colors and materials that compose the space.

Figure 1. Picture of the final environment, result of the creation process described in this article (Photo: Fran Parente).

The project’s purpose was to elaborate a holistic approximation in which digital media was present since the first sketches. In these sketches luminous patterns in one of the sidewalls were already been predicted, considering that it’s design, based on irregular triangulations, followed the language adopted for the whole carpentry of the project. The patterns are composed of 25 luminous triangles, only visible when lit. Concerning space, it was opted to leave apparent the original space structure, making the hydraulics and electrical systems visible. In this structure were also connected the sensors that collect information about the activities which occur in the space (Figure 2).

This environment explores the two layers of interaction described by Sauter (2001). The same way people alter physical properties of space through their movement, they get to know a little bit more about the habits and activities which occur there. Besides, the project has a behavior that can be open and redesigned. In order to make this possible, an access for the whole system (luminous triangles, sensors) was provided on the Internet, making possible the users develop other interactive possibilities in the future.

Figure 2. People working in space with the luminous panel working in the background (left) and detail of one of the ultrasonic sensors coupled to the apparent structure in the ceiling (right) (Photo: Fran Parente).

Since the beginning of this project, the intention was to achieve a horizontal creative process, with constant involvement and exchange among the different stakeholders. Therefore, besides the periodical meetings to evaluate the project pace, a specific creative workshop was elaborated for the project’s conceptual finalization. The workshop goal was to raise relevant information about the company’s activities and the clients and users’ expectations and space appropriation. The workshop results were used to ground the sensor’s choice, and the design of the behavior implemented in the environment.

The Workshop

The workshop was a unique activity, controlled, that lasted one and a half hour, elaborated and mediated by one of the architects responsible for the project main concepts. It’s role included the time management and to carry out the discussions, without the intention to directly intervene on the contents approached by the participants. Besides the mediator, the workshop was attended by two clients (users), two employees of the company (users), three architects, an electrical engineer and two invited researchers, totalizing 10 participants distributed in two groups, as presented in Figure 3. The groups were formed with the worry to balance the functions that the participants have in the project as a whole.

Figure 3. Distribution of the ten participants in the two groups set for the workshop.

With the triangle wall (output) already installed, the point of the discussion were the sensors which could be used to collect information (inputs) and the possible behaviors, that is, how the data affects the luminous triangle. Both groups debated on the space and the people’s habits and behaviors, relating these ones with possible sensors and their interactions, which could happen in the environment. As support material, were adopted floor plans in scale 1:50 and the i|o cards (Carneiro, 2010), a set of cards developed to stimulate conversation and exchange of ideas during the design of interactive systems.

The i|o cards are divided in two groups: one deals with the interactive system’s structural issues and the other one approaches some conceptual matters important for the creation of interactive experiences. The first group contains graphical representations of the microcontroller and of the main sensors-actuators that a beginner in the physical computing field usually gets to know, with the indication of the kind of information they supply (analogical or digital), as presented in Figure 4. The second group has in one of the surfaces, important concepts for the development on interactive behaviors focused on people’s experiences, and in the other face brief explanations of these concepts (Figure 5). For this workshop, the conceptual group was adopted in its totality, while from the structural cards only the sensors were used, in such way that actuators and microcontroller were left aside.

Figure 4. Structural cards of the i|o cards outlined in red are the cards used in this workshop (the sensors).

Figure 5. Conceptual cards of the i|o cards.

Concerning the workshop dynamics, both groups started with the plans in hands. The cards were then distributed alternatively: .Group 1 started the activity with the structural elements (in this case, only sensors) and Group 2 with the conceptual ones. After 15 minutes the rest of the cards were distributed for both groups. This way, one group was forced to begin the discussion by the technical issues and the other one by the experience. After 30 minutes of discussion, the groups had some time to organize the ideas and then present them, followed by a collective discussion. In Figure 6 we present the distribution of activities in time. At the end of the session, aiming to evaluate the activity, it was requested an e-mail from the participants with individual impressions about the workshop.

Figure 6. A distribution of the workshop activities during the period of one hour and a half. Detail for the alternate sequence of the distribution of the i|o cards between 00:15 and 00:45.

Regarding the adoption of the support material, there was a consensus between the two groups that it is more meaningful to start the discussion by the concepts before talking about technology. When reporting their ideas, Group 2, which received the structural cards first, made clear since the beginning that they would rather start the discussion by the concepts (what we want with space) then go to the technical part (how to carry out the chosen concepts). They reported that even with the sensors in hand, it was more natural to begin the discussion by the concepts and motivations. For this group, in the moment the concepts were delivered, they only checked if something was missing.

For Group 1, receiving the concepts already in the beginning helped them to manage the conversation (Picture 8). The words created an interesting scope for the discussion but were not used as a mandatory set of questions to be solved one by one. As a result, they specifically helped in special moments, such as when the rhythm of the conversation decreased. According to the participant 5’s report “when the second group of cards appeared, the group handled it, talked a little about the sensors, but they did not stick to the subject for a long time and came back to the former discussion (…). The sensors came into discussion but, in my interpretation, subordinated to the initial point of the discussion” (our translation).

Figure 7. Group 1 discussing the concepts (left) and in the moment they received the structural cards (right). (Photo: Gabriela Carneiro)

Describing further the employment of the support material, it was observed that only Group 2 used the structural cards together with the space plans. Group 1 only looked at the cards and took notes on a paper without incorporating the space plans as support for the information. Besides the cards with content, Group 2 used some blank cards distributed to be freely adopted according to unexpected needs (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Group 2 organizing the plant cards (left) and plant ready for the final presentation (right). (Photo: Gabriela Carneiro)

In this case, Group 2 adopted the blank cards to represent sensors whose cards amount was not enough, as well as to include other types of sensors, besides the ones available in the i|o cards. In general the combination of space plan and cards demonstrated to be very useful to support the organization and final presentation of ideas.

Results

As a result, the adopted workshop dynamic made possible a deep discussion of different possibilities for the environment in a relatively short time. The main ideas were synthesized by the participants themselves and presented in the final moment. To serve as input for the project, this presentation was recorded and then integrally transcribed. Next, the ideas were synthesized and used as inspiration for the design of the system behavior.

In Group 2 final presentation, the first one to comment its ideas, organized its talk on three types of interaction: events, behavior and control. Within the ‘events’, the group highlighted the importance of signaling people’s arrival, in such a way that the visitors could realize quickly that something happened with the space with their presence. As an event, the group also mentioned the idea of games activated by the furniture. They categorized as ‘behaviors’ interactions such as the system’s reaction according to the data network traffic or to the people’s movement in space, as “footprints” of their actions. They emphasized the importance of these behaviors have a random component not to be boring. To complete it, the ‘control’ interaction comprehends the possibility of turning on, off and altering the luminous patterns.

Group 1 highlighted the issue of the interactions and time, how they relate to each other, including immediate reactions as well as long-termed behavioral changes. Besides that, from a close analysis of the company’s employees, they mentioned the great variation between the concentration moments, where everybody is sitting still, and the moments on which is clear a general enthusiasm. In the end, they also talked about the importance of thinking about the priority levels of the different behaviors.

Behavior Design

After reviewing the information gathered at the workshop, the sensors were set to be installed in space and its location, as well as the pattern behavior to be implemented. Besides the 25 luminous triangles the interactive system had also six ultrasonic sensors installed at the ceiling’s structure, a microphone next to the kitchen and a sensor to capture the front door’s opening and closing (Figure 9). The behavior was implemented in PHP language and can be altered and expanded by the own users and other developed behavior.

Figure 9. The choice and distribution of sensors in space was performed from the discussions at the workshop.

Three types of interaction were defined and distributed in time according to the level of importance. The most overriding interactions superposes over the others below, according to Figure 10. At the lowest level it’s the standard interaction, that happens over the day and it’s based on obtained values by the six ultrasonic distance sensors scattered in the apparent roof structure. For this interaction, the space and the luminous triangles were subdivided in three zones considering that the average of values the two present sensors in each zone determines the speed in which the first triangle of each group will blink. To every 10 seconds break, this value is reverberated to the next triangle and the first starts to blink from the sensors ‘current value. The goal is to, with time, each set of triangles reflect the occupation of the respective zone and that the set of all pattern reflect in an abstract way their moving of their occupants over time (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Graphic representation of the relation between interaction priority and their occurrence in time.

Figure 11. Standard interaction. The superior image shows the first step, which is, first triangle of each group blinks in different intensity (the star shows the blinking break in seconds). The image below shows the wall after four steps. The initial values will spread through the triangles of each group.

This standard interaction can be interrupted anytime by two others: the snack time or input and output of people in the space, and the last one having the last option maximum priority, in other words, comes before all the others when triggered. The snack time was pointed, during the workshop, as the main moment of conversation and relaxing of the company, so was decided to install a microphone in the canteen area. When the microphone receives a large precise stimulus, that is, when the value reaches a determined peak the interaction takes action. This is characterized by joking: only one triangle is lit and updates the value of the microphone which determines what will be the next one to be lit. Thus, other challenges can be created by people themselves, such as a contest of who can make light cross from one side to the other in less time (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Interaction of lunch. The first triangle is turned on and the next is determined by the value captured by the microphone

The standard behavior of the third interaction is based on the will expressed during the workshop, to sign when important events happen, such as the arrival of visitors in space. For this reason, we installed a magnetic sensor that captures the opening / closing of the door. When triggered, a wave pattern is perpetuated in a movement of coming and going, which lasts up to five seconds after the door was closed again (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Interaction entry or exit of people. Once the door is opened, groups of triangles are set in a movement back and forth until the door is finally closed.

It was clear that the workshop contributed significantly to the project. The involvement of users assisted in the development of a behavior endowed with meaning for its users every day. Beyond the reach of the expected goal, several other points should be highlighted and discussed at the end of this article.

Conclusions

The workshop included questions that go far beyond the inputs to create a standard behavior provided as part of the space in the initial proposal of the project. Among other findings it is important to emphasize its role of providing input for the definition of an effective behavior based on the use of space. In this sense, it is clear that inviting users to participate in the creative process does not mean that they will define questions, but they will generate data to be subsequently considered by the responsible designers. As Lawson (2005, p.90) points, is very important to understand the real demands of users of a system or environment.

For this project, the workshop also had a major role in the future of this environment. Once one of this interactive features of the system, developed for this space, is the possibility of future interventions through its reprogramming, the workshop generated inputs as for the users themselves. Specific ideas were not initially implemented may stimulate future interventions. It is important to highlight the development of interactive system, which foresees altering possibilities, was an elaborate answer given by the architects to the profile of clients and users, whose abilities include the programming of websites and notable opening for experimentations with digital technology. The architecture here goes beyond its role of involucre and the space itself acts as stimulator of creative activities and exchanges among its users.

The participation of clients and users in the design process through the workshop, also promoted the sense of ownership of space themselves. The participant 2 reports that "at the end, my own perception of the overall project has matured and now I'm more excited than before." Given the innovative nature of the proposal, assisted in the dynamic process of understanding and increased awareness and knowledge of people who will enjoy this spatiality, with regard to the opportunities present there’s the possibility of future interventions through reprogramming, the workshop generated inputs for both architects and for their users. Specific ideas that were not initially implemented may encourage future interventions. Importantly, the development of an open interactive system - which provides the possibility of change - a response was drafted by the architects to the profile of customers and users, whose skills include programming websites and remarkable opening to experimenting with digital technology. Here the architecture goes beyond its role of dwelling and space itself acts as a stimulator of creative activities and exchanges among its users.

Another aspect to consider is the dynamic subside to expand the conceptual and practical repertoire of the participants in general. The mix of customers, users, architects and researchers provided a broad and mixed basis and clearly contributed to the enrichment of the discussions raised. According to the of the participant 6, "I believe that all this has produced an incredible number of ideas and ideas to other ideas" (our translation).

The use of support material was an essential element for the successful outcome of the workshop. The letters and plants allowed the experimentation of the design of an interactive space, and opened the opportunity for questions and several other actions. It would also have been interesting to use media materials for the exploration of light patterns of the set of triangles. At one point, the second group came to sketch these standards in a paper, which states that thoughts about ways to facilitate and make it tangible also this support t would have further contributed to the final result (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Detail of the Group 2 and the triangulation of the sketches that made the wall to aid discussion.

The design for the head office for the digital producer is the result of a new generation of designers and customers who want an alternative way to work, characterized by experimentation, opening and collaboration of the processes. In this case, the process of development of the interactive system juxtaposed to the design of shapes, to the choice of colors and materials that make up the space, and transposes in it, the values cultivated by the people who dwell it. The result is the integration of physical and virtual instances on a single project in a way that goes beyond the functionalist discourse which is usually associated with technology.

In a world in which objects, cars, clothes and environments exchange information with people and detect their actions and activities, is necessary to think about how to expand and add new relations between men and their habitat. We believe that part of the responsibility of architects and designers to manipulate the technology to create objects and environments that inspire creativity and imagination in people’s everyday lives.

Thanks

We thank the D3 Digital Productions for the opportunity to develop the project. By Guto Requena and Studio i|o Design by information about the process. To FAPESP for granding the research that contributed to the project conceptual issues.

References

Carneiro, G., [n.d.]. i|o Cards. 2010. Available at: <http://www.objetosinterativos.com.br/290/iocards/> [Accessed 05 October 2011].

Dourish, P., 2004. Where the action is: the foundations of embodied interaction. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Fox, M. and Kemp, M., 2009. Interactive architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

IDEO, 2002. Method cards: 51 ways to inspire design. San Francisco: William South Architectural Books.

Lawson, B., 2005. How designers think. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Moggridge, B., 2007. Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Saffer, D., 2007. Designing for interaction: creating smart applications and clever devices. Berkeley, CA: AIGA Design Press.

Sauter, J., 2011. Interviewed by Gabriela Carneiro. Berlin: Univeristät der Künste Berlin (UDK), 30 May.

Vallgarda, A. and Redstrom, J., 2007. Computational composites. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factor in Computing Systems. 2007. San Jose, CA: ACM.