Entrelaçados, hibridizados, múltiplos

Clarissa Ribeiro é Arquiteta e Doutora em Artes Visuais. Pesquisadora do Grupo de Pesquisa Poéticas Digitais da Escola de Comunicação e Artes (ECA) da Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Seus interesses de pesquisa percorrem os Diálogos e Interseções Seminais entre Arte, Tecnologia e as Ciências da Complexidade. (Brasil)

Como citar esse texto: Como citar este texto: RIBEIRO, C. Entrelaçados, hibridizados, múltiplos. V!RUS, Carlos, n. 6, dezembro 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus06/?sec=8&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Procurando discutir algumas questões centrais relativas ao processo criativo coletivo em artes digitais, nos apoiamos na construção de um metapontodevista, no contexto de uma abordagem sistêmica, complexista, a partir do qual é possível dar visibilidade à estrutura sistêmica e multidimensional dessa prática. Poéticas emergentes; Arte realizada em rede, coletivamente, envolvendo o conhecimento e domínio de uma miríade de técnicas, tecnologias, a articulação de saberes, referências, práticas, múltiplas dimensões de realidades, artistas múltiplos também.

Palavras-chave: processo criativo coletivo; artes digitais; sistemas complexos adaptativos; metapontodevista.

O pensamento cibernético, sistêmico, informacional, complexo, permitiu, nas últimas décadas, explorar as dimensões micro e macro da assim chamada realidade, do mundo dos fenômenos. Permitiu construir máquinas ratiocinatrix em escala nano, entender os processos de comunicação e controle no animal e na máquina, duplicar o indivíduo, alterar sua estrutura em sua gênese, simular, entender os processos criativos como processos sistêmicos, emergentes, trazendo a possibilidade de perceber e estudar dinâmicas organizacionais a partir de metodologias bottom-up.

Em um movimento simultâneo, ampliando-se exponencialmente com cada vez mais velocidade, os sistemas telemáticos [1] permitem conexões em vários níveis, expandindo a consciência ao nível global, e permitindo ao Eu ser vários, múltiplos e sobrepostos, entrelaçados em tempo e espaço independentes de geografia. Pode-se estar simultaneamente presente em várias realidades, acessando diversos níveis de realidade em cada uma destas. Como coloca Roy Ascott no artigo The Ambiquity of Self: living in a variable reality, o eu encontra “[…] presença física no ecoespaço, presença de aparição no espaço espiritual, telepresença no ciberespaço, e presença vibracional no nanoespaço”[2](ASCOTT, 2008, p. 25, tradução nossa, grifo nosso). Para o professor Ascott, nesse cenário, a nova arte digital é "[...] imaterial e úmida, numinosa e aterrada, enquanto a mente tecnoética simultaneamente habita o corpo e é distribuída ao longo do tempo e do espaço”[3](ASCOTT, 2008, p. 25, tradução nossa).

Assim, uma realidade sincrética emerge do que Ascott chama uma coerência cultural de intensa interconectividade, da coerência quântica como base da realidade, e da coerência espiritual da nossa consciência multinível. A arte digital nesse contexto é tão múltipla, híbrida, entrelaçada como os multiple selves(ASCOTT, 2008) em seu reino telemático multidimensional.

É nesse reino telemático que floresce a criação coletiva em artes digitais, emergindo em processos com características sistêmicas – fluxo de dados em estruturas em rede, tessituras informacionais significantes, abertos à transformação e mudança, complexos organizados adaptativos. Complexos que, para além das metodologias bottom-up, necessitam de um novo método para que sejam compreendidos. Um método, no sentido da construção de um olhar, de uma moldura para pensar, num sentido que se aproxima da noção de método em Edgar Morin.

Esse método da complexidade, “[...] se opõe à conceituação dita ‘metodológica’ em que ela é reduzida a receitas técnicas. Como o método cartesiano, ele deve inspirar-se em um princípio fundamental ou paradigma” (MORIN, 2003, p. 37). Para Morin, a diferença é justamente o paradigma, não se tratando de obedecer a um princípio de ordem através da eliminação da desordem, de claridade, eliminando o obscuro,

[...] de distinção (eliminando as aderências, as participações e as comunicações), de disjunção (excluindo o sujeito, a antinomia, a complexidade). [...] trata-se, ao contrário, de ligar o que estava separado através de um princípio de complexidade (MORIN, 2003, p. 37).

Abordagens como as do pesquisador Tim Ingold, da University of Aberdeen, na Escócia, no artigo Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials, propõem pensar e discutir, de que forma as conexões entre elementos em um sistema – que pode ser ele mesmo nosso espaço de interações na sociedade - constroem esse mesmo sistema. Essas conexões são mais que conexões, são, para o pesquisador, entrelaçamentos. Segundo Ingold, quando ele trata de entrelaçamento de coisas, se refere precisa e literalmente "[...] não uma rede de conexões, mas a uma trama de linhas entrelaçadas de crescimento e de movimento”[4](INGOLD, 2010, p. 3, tradução nossa). A proposta é não se ater na observação do sistema e seu processo dinâmico de organização, à materialidade, mas sim, aos fluxos.

A visão de Ingold retoma a questão da geração da forma, não simplesmente da rede de conexões que constituem um complexo, mas a partir de uma malha de linhas de movimento e crescimento, entrelaçadas. Morin, em O Método 1: a natureza da natureza, na parte em que trata sobre genealogia e generatividade da informação, relaciona geração de forma – da forma do próprio sistema -, a partir de processos informacionais. Morin relaciona, em última instância, informação e generatividade. Apesar de tratar da organização viva, dos organismos como complexos generativos, a visão construída pelo pensador ajuda a entender as relações entre informação, organização, e morfogênese sistêmica. Para Morin, a informação emerge ao mesmo tempo em que emerge um complexo generativo e uma organização comunicacional. Quando isola-se e liga-se essa informação generativa, podemos considerar que esta “é a configuração improvável e estabilizada, de caráter engramático (signo) e arquival, que, no interior do protoaparelho generativo, é necessária à repetição ou reprodução exata ao infinito dos processos de regeneração e de re-generação”(MORIN, 2003, p.394, grifo nosso).

Dentro da lógica dessa compreensão, um complexo informacional (complexo, pois a informação supõe comunicação, circulação, aparelho, entre outros) deve ser concebido não na origem, mas ao longo de um processo. Processo esse em que uma organização produtora de si, uma organização autopoiética na compreensão de Maturana e Varela (2007), se autoproduz. Essa organização, sistema complexo adaptativo, deve ser considerada em relação ao seu ambiente em um processo organizacional, circuito tetralógico que não é um círculo vicioso, mas um circuito através do qual se operam transformações irreversíveis, gênesis.

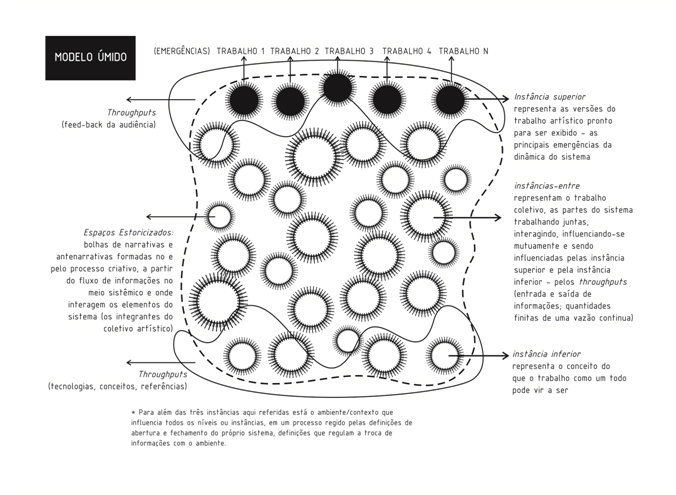

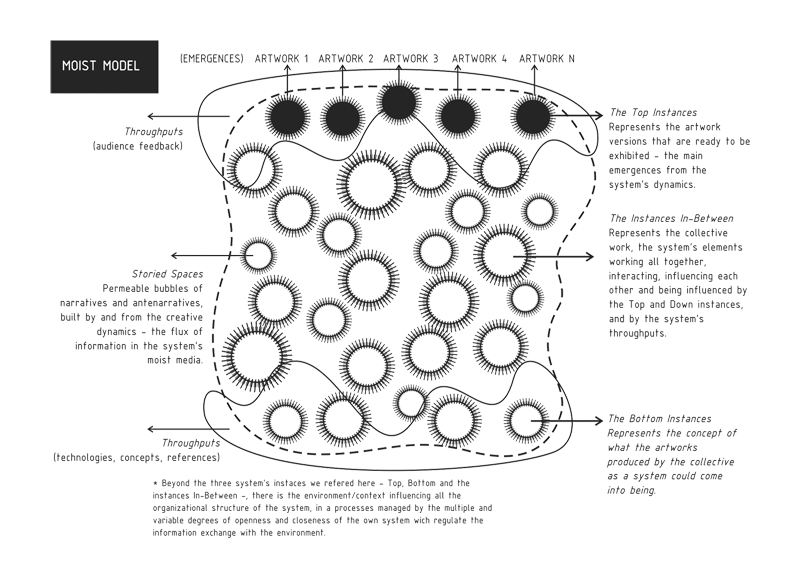

Considerando o processo criativo coletivo em artes digitais a partir dessa perspectiva, pode-se observar de que forma cada instância do sistema é resultado da rede dinâmica de influências que se configura entre todos os elementos do sistema e deles e do todo com o ambiente. Alcançar o objetivo do sistema de produzir trabalhos artísticos influencia fortemente a instância superior, assim como as referências e conhecimentos técnicos e teóricos influenciam a instância inferior.

É nas instâncias-entre que a dinâmica de produzir um trabalho artístico, permite ao artista atualizar a organização, interferindo na instância inferior da estrutura sistêmica. Esse movimento é parte do próprio processo auto-organizacional. É importante compreender que, enquanto elementos do sistema, os artistas envolvidos trabalham, atuam, em todas as instâncias do sistema. No entanto, eles passam a maior parte do tempo trabalhando nas instâncias-entre.

Na construção de um modelo que desse visibilidade à essas dinâmicas organizacionais, ao qual chamamos Modelo Úmido, a metáfora basilar é a de um meio úmido – moist media( ASCOTT, 2003) – no qual a informação circula como em um fluido de dados, e não através de conexões lineares. As conexões são multidimensionais e podem acontecer em diversos níveis de realidade (NICOLESCU, 2002).

Figura 1. O Modelo Úmido.

Apesar de ser observável na prática em artes digitais desde os primórdios, na década de 1980, é cada vez mais comum ver obras criadas coletivamente denominadas como partes de uma série - 001, 002, versão 1, versão 2, etc.. Um exemplo pioneiro é a série Points of View de Jeffrey Shaw, produzida entre 1983 e 1984. Os três trabalhos da série constituíam uma espécie de teatro de signos (SHAW, [s.d.]a, s.p.) em que o palco e os protagonistas eram gerados por computação gráfica e projetados sobre uma grande tela em frente à audiência. Na ação controlada utilizando joysticks especiais, um membro qualquer da audiência poderia mover-se interativamente no ambiente virtual projetado – 360° (trezentos e sessenta graus) ao redor do palco, 90° (noventa graus) para cima e para baixo, indo do térreo à vista aérea. No primeiro trabalho da série, Points of View I: Computergraphic installation, de 1983, a representação dos atores no palco foi derivada do antigo alfabeto Egípcio, onde cada figura era um caractere hieróglifo. Como explica Shaw, “essa constelação de signos foi utilizada para articular um modelo de mundo com uma subjacente relação de relacionamentos físico e conceitual”[5](SHAW, [s.d.]a, s.p., tradução nossa).

O segundo trabalho da série, Points of View II – Babel, também desenvolvido em 1983, incorpora questões relacionadas à Guerra das Malvinas – conflito entre Argentina e Reino Unido, no ano de 1982. Como explica Shaw, o trabalho “[...] implementou estruturas funcionais e iconográficas que eram similares a Points of View I. Os hieróglifos egípcios foram usados para articular ambas, uma arquitetura visual e psicológica – um edifício hierárquico definido para identificar a patologia essencial do poder e sua inevitável predisposição para opressão e guerra”[6](SHAW, [s.d.]b, s.p., tradução nossa).

Nessa segunda emergência da série, o som constituía um aspecto integral da instalação. Um total de 13 (treze) textos falados, extraídos do Congresso de Psicologia Militar, realizado em Viena no ano de 1983, foram ligados interativamente à imagem através do mesmo joystick que controlava o movimento virtual do usuário. Funcionando com um misturador de áudio, esse joystick modulava as várias vozes, em função de diferentes posições espaciais do usuário, em relação ao ambiente virtual. Dessa forma, cada pessoa que interagia, tinha a oportunidade de criar uma jornada audiovisual pessoal. Nas considerações de Shaw, a mudança das faixas de som, gerando um confronto espontâneo de informação falada, “[...] em conjunção com o movimento visual em torno da imagem, expôs as relações significantes dessa zigurate hieroglífica"[7](SHAW, [s.d.]b, s.p., tradução nossa)

O terceiro trabalho da série, Points of View III - A Three Dimensional Story, explorava a ideia de uma obra capaz de estimular a audiência a participar ativamente na construção final do trabalho artístico, convidando 16 pessoas a fazer contribuições narrativas. Essas contribuições eram interativamente ligadas à cenografia visual na qual essa audiência poderia navegar entre estórias paralelas. Participaram do processo coletivo de desenvolvimento dos três trabalhos da série Points of View, Larry Abel, responsável pelos desenvolvimentos relativos a software, e Tat Van Vark e Charly Jungbauer, responsáveis pelas questões relacionadas a hardware. Em uma reconstrução de Points of View I, em 1999, Torsten Ziegler foi o responsável pelos desenvolvimentos relativos a software e Armin Steinke a hardware.

A consideração de trabalhos de arte digital, realizados coletivamente como parte de uma série, evidencia a intenção de assumir a prática como um processo. De um modo geral, as séries mostram de que forma o dominar uma tecnologia específica, combinado à adoção de uma moldura conceitual particular, evolui em um processo de trabalho de base coletiva. Esse processo se estrutura a partir de uma intensa troca de informações, que liga os diversos níveis organizacionais de um todo que pode ter características complexas. Um exemplo contemporâneo que pode ser referido é a série de Camille Utterback, External Measures (2003). A série começou a partir da tentativa de criar pinturas interativas, e evoluiu na medida em que a artista, trabalhando coletivamente, “[...] experimenta com as possibilidades de articular sistemas computacionais com movimentos humanos”[8] (UTTERBACK, [s.d.], s.p., tradução nossa).

Outro exemplo é o trabalho Intimate Transactions do coletivo Transmute. O Coletivo, que se estabeleceu em 1998, começou a desenvolver Intimate Transactions em 2001. Existem dois projetos-piloto iniciais que fixaram as bases para futuros desenvolvimentos relacionados diretamente a essa obra – Liquid Gold (2001) e Transact (Flesh/Skin/Bone) (2002). De acordo com o diretor artístico Keith Armstrong, o coletivo

[...] decidiu que o núcleo de seu projeto interativo, computacional, seria inspirado pelos fluxos energéticos dentro de ecologias descritas cientificamente (por exemplo, os fluxos de energia que se originam do sol/fotossíntese e que são intercambiados via consumo e decomposição)[9] (ARMSTRONG, 2006, p. 16, tradução nossa).

Na proposta do coletivo, emergindo do conceito de uma imagem relacional de campo total, a colaboração e a ação coletiva se tornam elementos chave de uma práxis ecosófica. Com esse objetivo, foram adotadas abordagens capazes de dar à audiência a oportunidade de uma experiência compartilhada, interação social e discussão em torno de questões ecológicas prementes.

Ao longo de quatro anos de trabalho coletivo, Intimate Transactions evoluiu a partir de uma instalação local e não baseada em rede, para um trabalho artístico multi-local, articulado por um servidor, projetado para dois ou mais participantes em rede. Foi dessa forma que, segundo o diretor artístico Keith Armstrong (ARMSTRONG, 2006), a interatividade da audiência, o engajamento ecológico e a colaboração, foram estendidos para produzir uma complexa experiência relacional.

1 O termo Sistemas Telemáticos refere-se a todo uso integrado de telecomunicação e informatica, é também relacionado as TIC (Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação).

2 Do original em inglês: “[...] phisical presence in ecospace, apparitional presence in spiritual space, telepresence on the cyberspace, and vibrational presence in nanospace” (ASCOTT, 2008, p. 25).

3 Do original em inglês: “[...] immaterial and moist, numinous and grounded, while the technoetic mind both inhabits the body and is distributed across time and space” (ASCOTT, 2008, p. 25).

4 Do original em inglês: “[...] not a network of connections but a meshwork of interwoven lines of growth and movement” (INGOLD, 2010, p. 3, tradução nossa).

5 Do original em inglês: “This constellation of signs was used to articulate a world model with an underlying set of physical and conceptual relationships” (SHAW, [s.d.]a, s.p.).

6 Do original em inglês: “[…] It implemented functional and iconographic structures that were similar to Points of View I. Egyptian hieroglyphs were used to articulate both a visual and psychological architecture - a hierarchical edifice that set out to identify the essential pathology of power and its inevitable predisposition to oppression and warfare” (SHAW, [s.d.]b, s.p.).

7 Do original em inglês: “[…] in conjunction with the visual movement around the image exposed the signifying relationships of this hieroglyphic ziggurat” (SHAW, [s.d.]b, s.p.).

8 Do original em inglês: “[…] experiments with the possibilities for hinging computational systems to human movement” (UTTERBACK, [s.d.], s.p.).

9 Do original em inglês: “[…] decided that the core of their interactive, computational design would be inspired by the energetic flows within scientifically described ecologies (for example the flows of energy that originate from the sun/photosynthesis and are subsequently exchanged via consumption and decomposition)” (ARMSTRONG, 2006, p. 16).

Utilizando o Modelo Úmido como moldura para um estudo da complexidade do processo do coletivo Transmute, podemos considerar que esse coletivo se estrutura como processo e que, esse processo, pode ser estudado como um sistema complexo adaptativo na medida em que é evidente a inter-relação entre os integrantes do coletivo, sendo o sistema constituído por esses elementos em inter-relação. Mesmo em trabalhos realizados além dos limites do coletivo, tanto a performer Lisa O’Neill, quanto o diretor de som Guy Webster, continuam a dialogar com o diretor artístico Keith Armstrong, construindo uma trama de relações que é a base da arquitetura sistêmica, se articulando a partir de uma base conceitual e da exploração de tecnologias.

Os diversos trabalhos produzidos pelo coletivo podem ser lidos como emergências, na medida em que constituem resultados imprevisíveis da dinâmica sistêmica do Transmute. Enquanto emergência, cada um dos trabalhos artísticos da série, não resulta diretamente das ligações entre os integrantes do coletivo, mas do vislumbre da possibilidade de alcançar novos níveis organizacionais pelo coletivo.

Podemos considerar que o processo criativo do coletivo Transmute é um complexo organizado e adaptativo, na medida em que não responde passivamente aos eventos, se reorganizando em função de mudanças ambientais, contextuais. Isso fica evidente, por exemplo, quando o coletivo começa a trabalhar com a Australasian CRC for Interaction Design (ACID), como parte de um projeto de pesquisa do Australian Creative Industries Network (ACIN), e se reorganiza em função das mudanças, produzindo uma ampliação da instalação Intimate Transactions para uma versão multiusuário e em rede.

Para que se torne viável uma abordagem dessa natureza no estudo dos processos criativos coletivos, seja no domínio mais específico das artes digitais, ou em artes visuais, numa perspectiva mais ampla, é essencial o envolvimento com a prática artística. É esse envolvimento a base para a construção do olhar a partir da complexidade, para a construção de um metapontodevista – é meio para integrar o sistema que se pretende observar. A noção de sistema em que não há objeto totalmente independente do sujeito, em que não há physis isolável do entendimento humano, de sua lógica, de sua cultura e de sua sociedade, conduz o sujeito, “[...] não apenas a verificar a observação, mas a integrar a auto-observação ao sistema” (MORIN, 2003, p. 179). O objeto, seja ele real ou ideal, é um objeto que depende do sujeito.

Como diretora artística do coletivo O Duplo, com um envolvimento visceral no desenvolvimento dos trabalhos da série Instantes de Metamorfose – em todo o percurso poético, na realização das performances – é que tem sido possível compreender os aspectos de totalidade e o aspecto relacional, que poderiam fazer desse processo um sistema complexo. Somente assumindo a posição de observador-elemento do sistema, é que se pode vivenciar e compreender que a construção do complexo auto-organizado, que pode ter características generativas, se dá nas e pelas inter-relações entre seus integrantes. É essa perspectiva, a de um metapontodevista, que permite compreender o processo criativo coletivo como processo e esse processo como sistema.

Referências

ARMSTRONG, K. Towards a connective and ecosophical new media art practice. In: JILLIAN, H. (Ed.) Intimate transactions: art, exhibition and interaction within distributed network environments. Brisbane, Austrália: ACID Press, 2006, p. 12-35.

ASCOTT, R. The ambiguity of self: living in a variable reality. In: IX Consciousness Reframed Conference. Vienna, 3-5 jul. 2008. Vienna - Nova Iorque: University of Applied Ars - Springer, 2008, p. 22-25.

ASCOTT, R. Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness. Edited and with an essay by Edward A. Shanken. London: University of California Press, 2003.

INGOLD, T. Bringing things to life: creative entanglements in a world of materials. University of Aberdeen. Julho de 2010. Disponível em: <http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/1306/1/0510_creative_entanglements.pdf>. Acesso em: 04 jan. 2011.

MATURANA, H.; VARELA, F. A árvore do conhecimento: as bases biológicas da compreensão humana. São Paulo: Palas Athena, 2007.

MORIN, E. O método 1. A natureza da natureza. Trad. Ilana Heineberg. Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina, 2003.

NICOLESCU, B. Manifest of transdisciplinarity. New York: Suny Series, 2002.

SHAW, J. Points of view I: computergraphic installation, 1983. [s.d.]a. Disponível em: <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=67>. Acesso em: 20 fev. 2011.

SHAW, J. Points of view II – Babel: computergraphic installation, 1983. [s.d.]b. Disponível em: <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=68>. Acesso em: 20 fev. 2011.

SHAW, J. Points of view III - a three-dimensional story: computergraphic installation, 1984. [s.d.]c. Disponível em: <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=69>. Acesso em: 20 fev. 2011.

SHAW, J. Reconstructed points of view (1999). [s.d.]d. Disponível em: <http://www.virtualart.at/database/general/work/-667ae3a68e.html>. Acesso em: 13 dez. 2010.

UTTERBACK, C. Untitled 6: 2005. [s.d.] Disponível em: <http://www.camilleutterback.com/untitled6.html>. Acesso em: 15 abr. 2010.

Entangled, hybridized, multiple

Clarissa Ribeiro is Architect and Ph.D. in Visual Arts. Researcher at Poéticas Digitais Research Group at Escola de Comunicação e Artes (ECA) at Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Her research interests traverse the Seminal Dialogue and Intersections among Art, Technology and Complexity Sciences. (Brazil)

How to quote this text: How to quote this text: Ribeiro, C., 2011. Entangled, hybridized, multiple. Translated from Portuguese by Natalia Cortez Thomsem. V!RUS, [online] n. 6. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus06/?sec=8&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

Abstract

Attempting to discuss some central issues in relation to the creative process in digital arts, we rely in building a metapointofview, in the context of a systemic approach, complexist, from which is possible to get visibility to the systemic structure and multidimensional of this use. Emerging poetics; An art that is held in net, collectively, involving knowledge and domain of a myriad of technics, technologies, the articulation of knowledge, references, experiences, multiple dimensions of reality, and also multiple artists.

Key-words: collective creation process; digital arts; complex adaptive systems; metapointofview.

The cybernetic thought, systemic, informational, complex, allowed us in the last decades, to explore the micro and macro dimensions of the so called reality of the world of phenomena. It allowed to build ratiocinatrix machines in nano scale, to understand the communication and control processes in animals and machines, to duplicate the individual, to change the structure on its genesis, simulate, understand the creative process as systemic processes, emergents, bringing up the possibility of apprehend and study organizational dynamics from bottom-up methodologies.

In a simultaneous move, broadening up exponentially faster, the telematic systems[1] allow various levels of connections, expanding the consciousness to a global level, and allowing the self to be various, multiples and overlapping, interlaced in time and space despite of geography. Being possible to be simultaneously present in various realities, accessing different levels of reality in each one of them. As Roy Ascott says in his article The Ambiquity of Self: living in a variable reality, the self finds “[...]physical presence in ecospace, apparitional presence in spiritual space, telepresence on the cyberspace, and vibrational presence in nanospace” (Ascott, 2008, p.25). For Ascott, in this scene, the new digital art is “[...] immaterial and moist, numinous and grounded, while the technoetic mind both inhabits the body and is distributed across time and space” (Ascott, 2008, p.25).

And so, a syncretic reality emerges from what Ascott calls a cultural coherence of intense interconnectivity, of quantic coherence as reality basis, and of spiritual coherence of our multilevel conscience. The digital art in this context is so multiple, hybrid, interlaced as the multiple selves (Ascott, 2008) in its multidimensional telematic kingdom.

É nesse reino telemático que floresce a criação coletiva em artes digitais, emergindo em processos com características sistêmicas – fluxo de dados em estruturas em rede, tessituras informacionais significantes, abertos à transformação e mudança, complexos organizados adaptativos. Complexos que, para além das metodologias bottom-up, necessitam de um novo método para que sejam compreendidos. Um método, no sentido da construção de um olhar, de uma moldura para pensar, num sentido que se aproxima da noção de método em Edgar Morin.

It is in this telematic realm that blooms the collectively creation in digital arts, emerging in processes with systemical characteristics - dataflow in net structures, significant informational tissues, open to changing and transformation, organized adapted complexes. Complexes that, beyond bottom-up technologies, need a new method for being understood. A method, in sense of building a view, of a thinking frame, in a sense that approaches of Edgar Morin’s concept of method.

This complexity method, “[...] opposes itself to the so said conceptualization ‘methodological’ wherein it is reduced to technical recipes. Like the Cartesian method, it must inspire itself in a central principle or paradigm” (Morin, 2003, p.37, our translation). To Morin, the difference is precisely the paradigm, not obeying a principle of order through a disorder elimination, of clarity, eliminating the obscure,

“[...] of distinction (eliminating the adhesions, the participations and communications), of disjunction (excluding the subject, the antinomy, the complexity) [...] it is, instead, about linking what was separated by a principle of complexity” (Morin, 2003, p.37, our translation).

Approaches as of the researcher Tim Ingold, of Aberdeen University, in Scotland, in the article Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials, proposes to think and discuss in which way the connections between elements in a system - it can be itself our interaction space in society - build this same system. These connections are more than connections, to the researcher they are interwoven. According to Ingold, when he speaks of interwoven of stuff, he refers precisely and literally “[...] not a network of connections but a meshwork of interwoven lines of growth and movement” (Ingold, 2010, p.3). The proposal does not stick on the observation of the system and its dynamic process of organization, on the materiality, but on the flows.

Ingold’s point of view, resumes the issue of the shape generation not only from the net connections that are a complex, but from moving mesh and growth lines, that are interwoven. Morin, in “The first method: the nature of nature, when says about genealogy and generativity of information, relates shape generation - from own system’s shape - from the informational processes. Morin in “The first Method: the nature of the nature, where it says about genealogy and information generativity, relates shape generation - from own system’s shape - from informational processes. Morin relates, in last instance, information and generativity. Despite it’s being about the live organization, about the complex generative organisms, the point of view built by the thinker helps to understand the relations between information, organization and systemic morphogenesis. According Morin, information emerges at the same time a generative complex and a communicational organization emerge. When isolated and connected, that generative information can be considered as “the unlikely and stabilized configuration, with engrammatic (sign) and archival disposition, inner the generative proto unit, it is necessary the repetition or exact reproduction to the end of regeneration and re-regeneration processes” (Morin, 2003, p.394, our translation).

Inside this logic, the informational complex (complex because information assumes communication, circulation, apparatus, and so on) should be designed not in its conception, but during the process. In this process a own productive organization, a autopoietic organization on the comprehension of Maturana and Varela (2007), produces itself. Still, this organization, complex adaptive system, should be considered relating to its environment in an organizational process, tetralogic circuit that is not a vicious circle, but a circuit where irreversible transformations are worked out, genesis.

Considering the collective creative process in digital arts from this outlook, we can observe in which way each instance of the system is result of the influences dynamic net that is configured among all elements of the system, and of them and the whole with the environment. To reach the aim of the artistic works production system strongly influenciates the superior instance, such as the references and theoretical and technical knowledges that influenciates de inferior instance.

It is between the instances that the production dynamics of artistic works, allows the artist to update the organization, interfering on the inferior instance of the systemic structure. This move is parcel of the auto-organizational process. It is important to comprehend that, as elements of the system, the evolved artists work, act, in all instances of the system. However, they work mostly on between instances.

On the construction of a model that provides visibility to these organizational dynamics - called Moist Model - the basic metaphor is of a moist mean - moist media (ASCOTT, 2003) - in which information circulates as in a data fluid and not through linear connections. The connections are multidimensional and might happen in different reality levels (NICOLESCU, 2002).

Figure 1. The Moist Model.

Despite being found on digital arts practices since the beginning, on the 80’s, it has been more common to find collectively created pieces called as part of a series - 001, 002, first version, second version, and so on. A pioneer example is the series Points of View by Jeffrey Shaw, developed between 1983 and 1984. The three works of the series constituted a kind of signals theater (Shaw, n.d.a, n.p.) where the stage and protagonists were developed with computer graphics and projected over a big screen in front of the audience. On the action controlled by special joysticks, any member of the audience could interactively move himself on the virtual environment projected - 360 degrees around the stage, 90 degrees up and down, going from ground to aerial view. On the first work of the series, Point of View I: Computergraphic installation, from 1983, the actors’ representation on stage was derived from the antique Egyptian alphabet where each figure was a hieroglyphic character. As Shaw says, “this signals constellations was used to articulate a model of the world with an underlying relation of physical and conceptual relationships” (Shaw, n.d.a, n.p.).

The second work of the series, Point of View II - Babel, also developed on 1983; it incorporates issues related to the Malvinas War - a conflict between Argentina and United Kingdom, in 1982. As Shaw explains, the work “[...] implemented functional and iconographical structures similar to Point of View I. The Egyptian hieroglyphs were used to articulate both, a visual and psychological architecture - a hierarchical building defined to identify the essential pathology of power and its inevitable predisposition for oppression and war” (Shaw, n.d.b, n.p.).

On this second emergency of the series, the sound constituted a whole aspect of the installation. 13 spoken texts, extracted from the Military Psychology Congress, that happened in Vienna in 1983, were linked to the image through the same joystick that controlled the virtual movement of the user. Working with an audio mixer, this joystick modulated the various voices, according with different spatial positions of the user, comparing to the virtual environment. This way, each person that interacted, had the opportunity to create a personal audiovisual journey. According with Shaw, the changes on the soundtracks generating a spontaneous confrontation of spoken information, “[...] in conjunction with the visual movement around the image exposed the signifying relationships of this hieroglyphic ziggurat” (Shaw, n.d.b, n.p.).

The third work of the series, Points of View III - A Three Dimensional Story, explored the idea of a piece capable to stimulate the audience to participate actively on the final construction of the artistic work, inviting 16 people to make narrative contributions. These contributions were interactively linked to the visual scenography in which this audience was able to navigate through parallel histories. Larry Abel - responsible for development of software, Tat Van Vark and Charly Jungbauer - responsible to the subjects related with hardware participated to the collective development of the three works of Point of View series. In a reconstruction of Points of View I, in 1999, Torsten Ziegler was responsible for the developments related to software, and Armin Steinke to hardware.

The consideration of digital arts works, collectively built as part of a series, shows the intention to assume practice as a process. In a broader sense, the series shows how the domain of a specific technology, joined with the adoption of a unique conceptual framework, evolves in a collectively based working process. This process is structured from an intense information exchange, which links the different organizational levels of a whole that might have complex characteristics. A contemporary example is Camille Utterback’s series, External Measures (2003). The series started from the attemption to create interactive paintings, and evolved as the artist, working collectively, “[...] experiments with the possibilities for hinging computational systems to human movement” (Utterback, n.d., n.p.).

Another example is the work Intimate Transactions of the Transmute collective. The Collective, established in 1998, began to develop Intimate Transactions in 2001. There are two initial pilot-projects that set basis for the future developments related to this piece - Liquid Gold (2001) and Transact (Flesh/Skin/Bone) (2002). According to the art director Keith Armstrong, the collective

‘[...] decided that the core of their interactive, computational design would be inspired by energetic flows within scientifically described ecologies (for example the flows of energy that originate from the sun/photosynthesis and are subsequently exchanged via consumption and decomposition)’ (Armstrong, 2006, p.16).

At the collective proposal, emerging from the concept of relational image of whole field, the collaboration and collective action turn into key elements of an ecosophy praxis. With this aim, there were adopted approaches capable to give audience to the opportunity of a shared experience, social interaction and discussions about actual ecologic matters.

1 The term Telematic Sistems refers to all integrated use of telecomunication and informatic, is also refered to CIT’s (Comunication and Information Technologies).

During four years of collective works, Intimate Transactions evolved from a local installation and not based in network, for a multi-local artistic work, articulated by a server, projected for two or more participants in network. That way, according to Keith Armstrong (Armstrong, 2006, p.33), the interactivity of the audience, the ecological engagement and the collaboration, were extended to produce a complex relational experience.

Using the Moist Model as a frame for a complexity study of the collective Transmute, we can consider that this collective is structured as a process and that, this process, can be studied as a complex adaptive system, as it is evident the inter-relation between the members of the collective, being the system constituted by these elements in inter-relation. Even in works performed beyond the collective frontiers, performer Lisa O’Neill, and sound director Guy Webster, continue to dialogue with the artistic director Keith Armstrong, building a plot of relations that is the basis of systemic architecture, articulating itself from de conceptual basis and the exploration of technologies.

The several works produced by the collective can be read as emergences, as they constitute unpredictable results on the systemic dynamic of Transmute. As emergency, each one of the series artistic works don’t turn directly of the connections of the members of the collective, but to the glimpse with the possibility to reach new organization levels by the collective.

We may consider that the creative process of the collective Transmute is an organized and adaptive complex, as it doesn’t respond passively to events, reorganizing itself according to environmental changes, in context. That is clear when the collective starts to work with the Australasian CRC for Interaction Design (ACID), as part of a research project of the Australian Creative Industries Network (ACIN), and reorganizes according with the changes, producing an extension of the installation Intimate Transactions for a multi user version in network.

For a approach of this nature on the study of the creative collective processes to be possible, in visual arts or in a more specific domain on digital arts, to be possible, is essential the involvement with the artistic practice. That involvement is the basis for the construction of the view from the complexity, for the construction of a metapointofview - it is kind of to integrate the system that is meant to be watched. The notion of system that has no totally independent object of the subject, were there is no isolated physis of the human understanding, of its logic, culture and society, leads the subject, “[...] not only to verify the observation, but to integrate the auto observation to the system” (Morin, 2003, p.179, our translation). The object, being it real or ideal, it’s an object that depends on the subject.

As artistic director from the collective O Duplo (the double), with a visceral involvement on the development of the works of the series Instantes de Metamorfose - through the whole poetic route, in the realization of performances - is being possible to comprehend the aspects of totality and relational aspect, that could make this process a complex system. It is assuming the status of watcher-element of the system that might have generative characteristics, it’s given on the inter relationships between their members. In that perspective, from a metapointofview, that comes the understanding of the collective creating process as a process and that process as a system.

References

Armstrong, K., 2006. Towards a connective and ecosophical new media art practice. In: H. Jillian (Ed.), 2006. Intimate transactions: art, exhibition and interaction within distributed network environments. Brisbane, Australia: ACID Press, pp.12-35.

Ascott, R., 2008. The ambiguity of self: living in a variable reality. In: IX Consciousness Reframed Conference. Vienna, 3-5 July, 2008. Vienna - New York: University of Applied Ars - Springer, 2008, pp.22-25.

ASCOTT, R., 2003. Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness. Edited and with an essay by Edward A. Shanken. London: University of California Press.

Ingold, T., 2010. Bringing things to life: creative entanglements in a world of materials. University of Aberdeen. July. Available at: <http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/1306/1/0510_creative_entanglements.pdf>[Accessed 04 January 2011].

Maturana, H. and Varela, F., 2007. A árvore do conhecimento: as bases biológicas da compreensão humana. São Paulo: Palas Athena.

Morin, E., 2003. O método 1. A natureza da natureza. Trans. Ilana Heineberg. Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina.

Nicolescu, B., 2002. Manifest of transdisciplinarity. New York: Suny Series.

Shaw, J., n.d.a. Points of view I: computergraphic installation, 1983. Available at: <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=67>[Accessed 20 February 2011].

Shaw, J., n.d.b. Points of view II – Babel: computergraphic installation, 1983. Available at: <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=68>[Accessed 20 February 2011].

Shaw, J., n.d.c. Points of view III - a three-dimensional story: computergraphic installation, 1984. <http://jeffrey-shaw.net/html_main/show_work.php?record_id=69>[Accessed 20 February 2011].

Shaw, J., 1999. Reconstructed points of view. Available at: <http://www.virtualart.at/database/general/work/-667ae3a68e.html>[Accessed 13 December 2010].

Utterback, C. Untitled 6: 2005. [s.d.] Available at: <http://www.camilleutterback.com/untitled6.html>[Accessed 15 April 2010].