Vozes de mulheres negras de Parelheiros: Internet, interseccionalidade

Ana Gabriela Godinho Lima é arquiteta e urbanista, Doutora em História da Educação e Filosofia do Conhecimento com Pós-doutorado em Artes. É Professora Adjunta do Programa de Pós-Graduacão da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, onde é co-responsável pelo Projeto de Pesquisa "Cidade, Gênero e Infância". É autora do livro "Arquitetas e arquiteturas na América Latina do século XX" (Altamira Editorial, 2013). Estuda Arquitetura Escolar, Ensino de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, História das Mulheres na Arquitetura, História da Arquitetura na América Latina, História e Teoria da Arquitetura Contemporânea, Processos de Projeto em Arquitetura e Urbanismo e Design. anagabriela.lima@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/2010070403291740

Angélica Aparecida Tanus Benatti Alvim é arquiteta e urbanista, Doutora em Arquitetura e Urbanismo e Professora Titular da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da mesma instituição. É líder do grupo de pesquisa Urbanismo Contemporâneo: redes, sistemas e processos, onde realiza pesquisas sobre projeto urbano, mobilidade e meio ambiente. angelica.alvim@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/3698530751056051

Jaqueline de Araujo Rodolfo é arquiteta e urbanista, Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo e pesquisadora do grupo de pesquisa Urbanismo Contemporâneo: redes, sistemas e processos, da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Estuda intervenções urbanas, programas de urbanização, assentamentos precários, dimensões da sustentabilidade, meio ambiente e mananciais da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo. jaqueline.rodolfo@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/9553533340324968

Como citar esse texto: LIMA, A. G. G.; ALVIM, A. T. B.; RODOLFO, J. A. Vozes de mulheres negras de Parelheiros: Internet, interseccionalidade. V!RUS n. 23, 2021. [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus23/?sec=4&item=6&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 30 Jun. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 15 DE AGOSTO DE 2021

Resumo

Este trabalho analisa os discursos das mulheres negras de Parelheiros — um dos distritos mais pobres e violentos da cidade de São Paulo — veiculados em sítios eletrônicos. Foi adotada a seguinte metodologia: levantamento dos sítios eletrônicos que abordam pautas raciais, periféricas, de gênero e os problemas vividos por mulheres em Parelheiros; construção do quadro teórico para a análise a partir de quatro eixos: o feminismo interseccional, as vozes negras na Internet, o contexto de Parelheiros e o posicionamento da discussão no âmbito das epistemologias do Sul Global. Como resultado, verifica-se que a circulação de diferentes formas de expressão escrita por meio da Internet transformou-se em ferramenta de superação do chamado "silenciamento das periferias", possibilitando a formação de redes de solidariedade, organização de eventos, desenvolvimento de projetos de formação e capacitação. Constatou-se, ainda, que, em conjunto, as vozes de mulheres negras veiculadas pela Internet expressam necessidades e aspirações pessoais e coletivas, que de outra forma seriam dificilmente visíveis. Os relatos de como os espaços urbanos ensejam e convidam — ou dificultam e impedem — as oportunidades dessas mulheres, caracterizam em boa medida os modos como as desigualdades sociais, econômicas, raciais e de gênero são experienciadas e trabalhadas por esses grupos e suas comunidades.

Palavras-chave: Sul Global, Mulheres Negras, Parelheiros, Interseccionalidade, Internet

1 Introdução

As vozes das mulheres negras raramente são ouvidas ou levadas em conta no processo de planejamento, projeto e implantação das intervenções em comunidades urbanas nas cidades do Sul Global, caracterizadas pela diversidade e desigualdade (BROTO, ALVES, 2018; RIGON, BROTO, 2021). Na constituição destas comunidades, um determinado grupo passa a existir a partir do surgimento de programas e técnicas que estimulam e aproveitam práticas ativas de gestão da própria individualidade e construção de identidades, de éticas pessoais e alianças coletivas (Rose, 1999 apud RIGON, BROTO, 2021). Nesse sentido, a escrita das mulheres negras periféricas veiculada em sítios na Internet pode ser entendida como ferramenta de fortalecimento, um modo de dar sentido ao "Eu" dessas mulheres, bem como de constituição de redes de apoio, formação e criatividade. Neste trabalho, analisamos os discursos por escrito das mulheres negras de Parelheiros, distrito localizado na periferia Sul da cidade de São Paulo — cujos índices de pobreza e precariedade estão entre os mais altos do município. A partir da perspectiva interseccional observamos como a vivência nesses espaços urbanos interfere nas oportunidades de vida e experiências destas protagonistas.

Situamos a análise desses discursos no âmbito das propostas epistemológicas do Sul Global, tal como caracterizadas por Santos, Araújo e Baumgarten (2016). Essas abordagens desafiam as "exclusões produzidas por conceitos eurocêntricos" (p. 20) e consideram como central ao debate decolonial a questão "da produção e circulação de conhecimentos e da epistemologia." (p. 14) Hofmann e Duarte (2021) observam ainda que autoras feministas do Sul Global identificam, nas políticas de desenvolvimento, continuações do colonialismo patriarcal. Com suas dinâmicas extrativistas, estas avançam sobre os territórios e sobre os corpos. Nesse sentido, a discussão aqui proposta situa as mulheres negras autoras como sujeitos epistêmicos que "produzem, interagem e compartilham seus conhecimentos" (HOFMANN, DUARTE, 2021, p. 44) sobre os territórios em que habitam.

Os seguintes passos metodológicos foram adotados: em primeiro lugar, o levantamento dos sítios eletrônicos que abordassem pautas raciais, periféricas e de gênero em Parelheiros a partir de narrativas de mulheres negras. Ao longo do levantamento, o foco recaiu sobre as experiências e reflexões que ocorreram em interação com espaços edificados ou espaços urbanos. Exemplos são, por um lado, narrativas de encontros em bibliotecas e salas de aula, atividades realizadas em ruas ou praças públicas. Por outro lado, são testemunhos e reflexões sobre experiências de violência, medo, discriminação ou dificuldades relativas à precariedade de equipamentos ou infraestrutura urbana. Em seguida, foi desenvolvido o quadro teórico para a análise das narrativas levantadas a partir de quatro eixos: o feminismo interseccional, as vozes negras na Internet, o contexto de Parelheiros e o posicionamento desta discussão no âmbito da produção e circulação de conhecimentos no Sul Global.

No primeiro eixo, a discussão fundamenta-se em Allen (2016), Akotirene (2019) e Silva e Ribeiro (2018). Nele, o foco da abordagem do feminismo interseccional é trazer à luz questões específicas vividas pelas mulheres negras no território de Parelheiros, tornando visível o modo como o racismo e o sexismo articulam-se como mecanismos de opressão. No segundo eixo, a partir do trabalho de Silva e Ribeiro (2018) e das discussões promovidas por portais como o Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades (CEERT), Articulação de Mulheres Negras e Brasileiras (AMNB) e Blogueiras Negras, estabelecem-se as bases conceituais de análise. A partir destas constrói-se um entendimento sobre o papel da Internet na veiculação e circulação dos discursos das mulheres negras e periféricas, em geral vetado ou dificultado pelos meios tradicionais de publicação. O terceiro eixo constitui-se na caracterização das condições de vulnerabilidade social e territorial em Parelheiros, em particular no que se refere a aspectos raciais e de gênero. Para tanto, conta com o levantamento em fontes governamentais de dados como o Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Estatística (IBGE), a Plataforma municipal Geosampa e a Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados (SEADE). O quarto eixo posiciona a discussão no contexto das epistemologias do Sul Global, conforme discutem Santos, Araújo e Baumgarten (2016) e Hofmann e Duarte (2021), lançando luz sobre sujeitos epistêmicos invisíveis na perspectiva das chaves conceituais e intelectuais formuladas a partir dos valores do Norte Global. É neste enquadramento que, sob a perspectiva decolonial, torna-se possível compreender como a fala das mulheres negras de Parelheiros pela Internet é essencial não apenas na análise dos aspectos do território que habitam, mas também de seu papel como participantes ativas de uma rede de vozes provenientes de diferentes territórios de vulnerabilidade social e territorial no Sul Global. Considera-se que o conhecimento dessas mulheres é fundamental para a formulação de qualquer intervenção territorial, como colocam Broto e Alves (2018) e Rigon e Broto (2021).

1.1 A abordagem do feminismo interseccional

A perspectiva interseccional torna visíveis mecanismos de opressão que não são perceptíveis sob outras lentes. Nas dinâmicas de coprodução das cidades, parte-se do reconhecimento de que o uso e controle das infraestruturas e recursos em áreas urbanas refletem as estruturas hegemônicas de poder (ALLEN, 2016). Tais dinâmicas transformam-se em formas de violência variadas, derivadas da falta de reconhecimento dos modos específicos de vida e dos problemas experimentados em escala individual (BROTO, ALVES, 2018). A interseccionalidade situa-se no âmbito do feminismo negro, cujos fundamentos vêm sendo construídos por autoras negras desde o século XIX. Maria W. Stewart, Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper e Sojourner Truth já distinguiam o racismo e o sexismo como mecanismos distintos de opressão. Ao articularem-se e reforçarem-se mutuamente, estes mecanismos geram problemas peculiares às mulheres negras, que os vivem de uma forma que nem mulheres brancas nem homens negros experimentam (ALLEN, 2016).

O termo "interseccionalidade", cunhado pela intelectual afro-estadunidense Kimberlé Crenshaw, surge em dois trabalhos publicados em 1991: Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics e Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color (ALLEN, 2016). A popularidade acadêmica desses textos aconteceria após a Conferência Mundial contra o Racismo, Discriminação Racial, Xenofobia e Formas Conexas de Intolerância (2001), ocorrida em Durban, na África do Sul, ainda que correndo o risco de passar “do significado originalmente proposto aos perigos do esvaziamento” (AKOTIRENE, 2019, p. 13-14). No âmbito brasileiro, no final dos anos 1970, a intelectual Lélia Gonzalez, já articulava questões ligadas à opressão de gênero, raça e classe, alertando sobre a interseccionalidade (sem usar a expressão) dessas violências. Enquanto isso, a socióloga afro-estadunidense Patricia Hill Collins substantivava o trabalho de ativistas e pesquisadoras negras no Brasil e na América Latina. No entanto, para Silva e Ribeiro (2018), o pensamento de Gonzalez não alcançou o reconhecimento e impacto que merecia, possivelmente por ter se originado em uma década com recursos muito mais limitados de divulgação e comunicação. Isso explicaria por que uma grande proporção de feministas negras jovens atribuiu a Crenshaw a criação do conceito de feminismo interseccional.

O debate aberto pela perspectiva interseccional inspirou protagonistas como a filósofa e ativista brasileira Sueli Carneiro a fundar o Portal Geledés— Instituto da Mulher Negra1. Considerado a organização negra mais relevante nas décadas de 1990 e 2000 (SILVA, 2018, p. 254), o sítio eletrônico é tido como "espaço de expressão pública de suas realizações no passado e no presente [...]" (PORTAL GELEDÉS, c1997 – 2021, n. p). Como veículo de informação, o Geledés foi visionário ao detectar a importância desta via de comunicação como modo de fazer frente às narrativas dominantes, motivando o surgimento de outras organizações de mulheres negras no Brasil que se comunicam por meio da Internet. É o caso de portais como o Criola e o Blogueiras Negras (SILVA, RIBEIRO, 2018). A Internet e as redes sociais foram progressivamente favorecendo a popularização do feminismo negro, em grande parte porque suas protagonistas podiam ir a público sem passar pelas barreiras da aprovação acadêmica ou das grandes editoras. Por meio dessas vias, as narrativas das mulheres que são mães e donas de casa, nordestinas, transexuais e jovens que não completaram o ensino médio vêm à tona (SILVA, RIBEIRO, 2018), oferecendo vislumbres de mundos, até então, quase invisíveis.

1.2 Vozes negras brasileiras na Internet

Vimos nas últimas décadas a ampliação da presença de jovens feministas negras nos meios de comunicação. Telejornais e portais de notícias tradicionais e de ampla circulação passaram a contar com protagonistas que se beneficiaram dos caminhos abertos pela luta das organizações de mulheres negras desde 1980. Antes disso, registram-se importantes contribuições dessas protagonistas nas áreas educacionais e culturais, na formulação de políticas públicas, e outras áreas do saber (SILVA, RIBEIRO, 2018). Este foi um importante substrato sobre o qual se organizaram, além do Geledés, portais referenciais como o Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades (CEERT), o Articulação de Mulheres Negras Brasileiras (AMNB) e o próprio Blogueiras Negras.

O CEERT2, com sede na cidade de São Paulo, foi fundado em 1992 por Hédio Silva Jr., Ivair Augusto Alves dos Santos e Maria Aparecida Silva Bento. Como organização não-governamental, "produz conhecimento, desenvolve e executa projetos voltados para a promoção da igualdade de raça e gênero" (CEERT, c2002 – 2021, n. p.). Atua nas áreas de educação e raça, com presença em congressos e fóruns, ações escolares e intercâmbio de estudantes por meio de instituições como o British Council. Valorizando a perspectiva de gênero, o CEERT mantém projetos como o Enfrentamento da Violência Contra as Mulheres, com Recorte de Raça, em parceria com o Instituto Avon e o programa de Assessoria para a Equidade de Raça e Gênero, em parceria com a Fundação Itaú Social.

O portal Articulação de Mulheres Negras Brasileiras3 conecta vinte e nove organizações em todo o território nacional. Tem como missão: "promover a ação política articulada de grupos e organizações não governamentais de mulheres negras brasileiras" (AMNB, c2021, n. p.), buscando combater o racismo, o sexismo e a opressão de classe. Mantém um mapa de localização das organizações participantes no qual é possível obter os dados de contato, bem como informações sobre seu escopo de atuação (AMNB c2021). Atualmente é coordenado pelo Centro de Estudo e Defesa do Negro no Pará (CEDENPA), pelo Instituto de Mulheres Negras de Mato Grosso (IMUNE), pelo N'Zinga — Coletivo de Mulheres Negras de Belo Horizonte, pelo Odara — Instituto da Mulher Negra e pela Rede de Mulheres Negras do Paraná (RMNPR). Por sua vez, criado para fortalecer e dar visibilidade à produção de cultura, a plataforma digital Blogueiras Negras4, fundada em 2012, originou-se do projeto Blogagem Coletiva da Mulher Negra com o objetivo de dar visibilidade a um conjunto significativo de produção literária de mulheres negras. Comunidade composta por mais de mil e trezentas mulheres, a plataforma conta com produções escritas de duzentas autoras negras direcionadas a combater o racismo, a lesbofobia, a transfobia, a homofobia e a gordofobia. Dentre as formas de produção cultural visadas pelo site estão os blogs, vídeos, livros e áudios que também promovem e celebram a cultura afrodescendente (BLOGUEIRAS NEGRAS, c2020).

Os quatro sítios evidenciam o fortalecimento das organizações de comunidades negras ao longo de décadas em que, apenas no Brasil, ainda seria possível mencionar um número significativo de eventos que forneceram bases para a construção dessas iniciativas. Um dos mais significativos foi a Marcha das Mulheres Negras 2015 contra o Racismo e a Violência e Pelo Bem Viver, um movimento brasileiro que levou a Brasília quase cinquenta mil mulheres. A Carta das Mulheres Negras de 2015 foi publicada no Portal Geledés por ocasião deste evento. Dentre suas reivindicações, consta o acolhimento, por parte do Estado e da sociedade, do direito à vida e à liberdade; a promoção da igualdade racial; o direito ao trabalho, emprego e proteção das trabalhadoras negras em todas as atividades; o direito à Terra, ao Território e à Moradia; e o Direito à Cidade bem como o direito à seguridade social, à educação e à justiça, à cultura, à informação e comunicação e à segurança pública (PORTAL GELEDÉS, 2015).

2 Condições de vulnerabilidade social e territorial em Parelheiros: raça e gênero

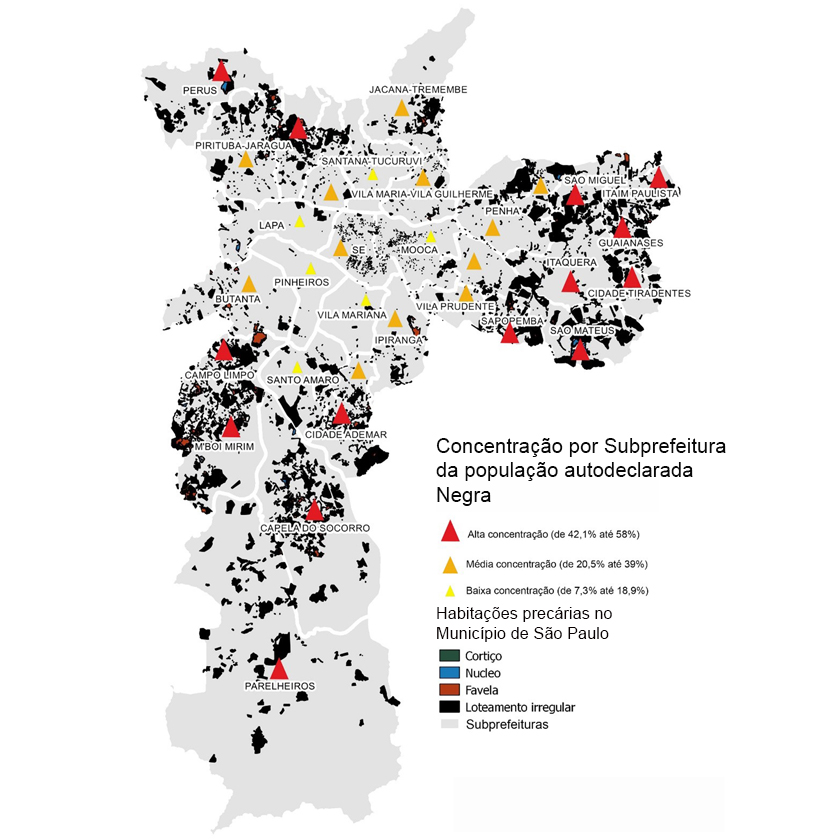

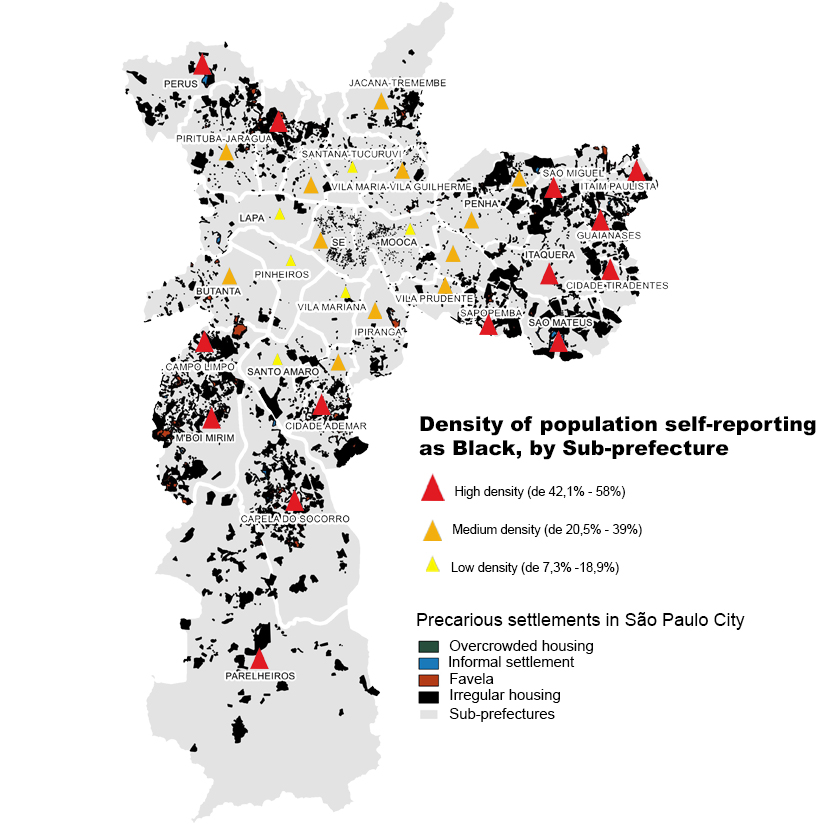

Conforme o último Censo do IBGE (2010), 37% da população recenseada — dentre 11.253.503 habitantes do município de São Paulo — é autodeclarada negra (parda e preta). Esses dados, conforme recorte de gênero, apontam que as mulheres negras são maioria, contabilizando 2.130.240 habitantes — número que representa 51% da população autodeclarada negra. Embora a população negra do município não seja a maioria entre as autodeclarações (61% população branca, 37% negra e 2% amarela), nota-se, por meio da espacialização da população ilustrada na Figura 1, abaixo, a concentração de determinados grupos nas subprefeituras do município. Os três principais distritos com maior concentração de pessoas pretas e pardas são: Parelheiros (57,1%), M’Boi Mirim (56%) e Cidade Tiradentes (55,4%) (SÃO PAULO, 2015). As três regiões com o maior número de pessoas brancas e que não chegam a 15% do número de pessoas negras são os distritos de Pinheiros, Vila Mariana e Santo Amaro (SÃO PAULO, 2015).

Fig. 1: Mapa da concentração de pessoas negras por Subprefeitura e condições das habitações no município de São Paulo Fonte: Elaborado pelas autoras, 2021, com base no CENSO IBGE, na Plataforma GeoSampa e em levantamento realizado pela Secretaria Municipal de Promoção da Igualdade Racial da prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo (2015).

Tal espacialização da população no município, junto à localização dos assentamentos precários (cortiços, favelas, núcleos e loteamento irregular), revela uma forte desigualdade socioespacial. Por meio desse mapeamento, é possível identificar que, quanto maior a porcentagem de pessoas negras, maior a recorrência de situações de habitação precária. Esse é o cenário da Subprefeitura de Parelheiros — composta pelos distritos Marsilac e Parelheiros —, que concentra 57,1% da população autodeclarada negra em um contexto de conflitos entre a desigualdade urbana e a proteção ambiental. Trata-se da maior subprefeitura em extensão territorial da capital paulista, com uma área de 353,5 Km2 — o que corresponde a 23,68% do município —, ocupada por 150 mil habitantes.

Situada no extremo sul do município, com forte característica rural reforçada por meio do último Plano Diretor Estratégico de São Paulo de 2014 (Lei Municipal 16.054/2014), a Subprefeitura de Parelheiros localiza-se entre as represas Guarapiranga e Billings, a 10 km da Serra do Mar. Possui em seu território importantes Áreas de Proteção Ambientação (APA), como as unidades de conservação APA Capivari-Monos e APA Bororé-Colônia, além das aldeias indígenas guarani do Krukutu e da Barragem. Seus distritos possuem baixa densidade populacional — Parelheiros, com 825 hab/km² e Marsilac, com 41 hab/km² — em comparação com distritos mais densos, como por exemplo os situados na subprefeitura da Sé, como Bela Vista, com 26.715 hab/km2. Por ser uma área de preservação ambiental, destaca-se a concentração de situações de precariedade, em específico no distrito de Parelheiros, que apresenta nível de vulnerabilidade social de médio a alto segundo o Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social (IPVS) realizado pela Fundação Seade (SÃO PAULO, 2010). Esses dados demonstram, a partir da combinação de condições demográfica e socioeconômica, os fatores específicos que produzem a deterioração das condições de vida como baixos índices de renda média, escolaridade, ciclo de vida familiar, possibilidade de inserção no mercado de trabalho e acesso a bens e serviços públicos.

No âmbito da mobilidade, o distrito apresenta tempo de viagem acima da média do município — mais de uma hora —, e tem como principal modo de transporte o público coletivo, seguido pelo individual ou a pé (SÃO PAULO, 2016). De acordo com Nunes (2019), em 2018, somente seis linhas de ônibus serviam ao distrito e, dessas, apenas três transportavam até o centro da cidade — em tempos de viagem que levavam até três horas. A precariedade nos serviços públicos também se reflete nos índices com recorte de gênero. De acordo com estes, o distrito está entre as principais posições com casos de gravidez na adolescência — no distrito, 17% dos bebês nascidos vivos é filha ou filho de uma mãe de 19 anos ou menos (SEADE, 2014) —, além das poucas ofertas de hospitais ou leitos, e está entre os quarenta piores no que se refere ao acompanhamento pré-natal considerado insuficiente (REDE NOSSA SÃO PAULO, 2018).

3 Vozes e vivências das mulheres e meninas negras de Parelheiros: o dado essencial para a formulação de políticas urbanas

As vozes e vivências das mulheres e meninas negras de Parelheiros encontram nos sites de coletivos um meio de obter visibilidade, ampliar redes de apoio e colaboração e alcançar reconhecimento e credibilidade. Neste trabalho, foram identificados os seguintes coletivos atuantes em Parelheiros por meio de suas redes sociais: os coletivos Escritureiros e Sementeiras de direitos; o coletivo Abayomi Aba, uma iniciativa que congrega vários outros coletivos negros da região Sul de São Paulo, promovendo ações em colaboração e parcerias; e o coletivo Rusha Montsho, que reúne protagonistas que já mantinham ações individuais ou pertenciam a outros coletivos e, portanto, já possuem experiência nas pautas raciais e de gênero. Longe de alcançar a diversidade de iniciativas temáticas abordadas por esses coletivos, a intenção aqui foi estabelecer uma amostra que permitisse identificar pautas recorrentes que surgem a partir dos discursos, narrativas e vivências das mulheres e meninas negras de Parelheiros. Subjazem às análises dessas narrativas o reconhecimento de sua relevância para a formulação de políticas urbanas.

Os dois primeiros sítios eletrônicos analisados foram, respectivamente, os dos coletivos Escritureiros5 e Sementeiras de Direitos6. Ambos sediados na plataforma eletrônica do Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos e Apoio Comunitário (IBEAC), organização não governamental que atua na promoção dos direitos humanos por meio de projetos comunitários de fortalecimento da cidadania. Suas ações são baseadas em princípios de sustentabilidade e replicabilidade (IBEAC, c2021). Neste contexto, a página do coletivo Escritureiros é dedicada à divulgação das atividades de um grupo, formado em 2008, de adolescentes e jovens que se dedicam à formação em direitos humanos e troca de saberes. Desenvolvem projetos literários e atividades que promovem a cultura local. São responsáveis pela gestão, mediação e articulação da Biblioteca Comunitária Caminhos da Leitura, promovendo atividades de mediação de leitura em escolas, creches e eventos literários. As atividades do coletivo são divulgadas por meio da página no Facebook chamada “Escritureiros: Escrita, Aventureiros de Parelheiros”. Tem como foco o incentivo à escrita e à leitura enquanto as temáticas de gênero, raça e periferia são abordadas como tema subjacente às atividades realizadas.

Já o coletivo Sementeiras de Direitos é um grupo voltado para a conscientização e acolhimento de mulheres vítimas de violência de gênero. Tem como foco narrativo a desconstrução de estereótipos e preconceitos de gênero e dedica-se à formação de mulheres para o empreendedorismo social em Parelheiros (IBEAC, c2021). Suas ações são divulgadas na página homônima no Facebook, em frequente colaboração com o coletivo Escritureiros, em que também são reproduzidas notícias de interesse local acerca das temáticas de gênero, raça e periferia. Anualmente, o coletivo organiza edições do Seminário Sementeiras de Direitos, formado por rodas de conversa e oficinas acerca de temáticas de direitos e segurança da mulher.

O coletivo Abayomi Aba Pela Juventude Negra Viva7 focaliza o fortalecimento da articulação política entre os coletivos voltados para a cultura e para a promoção da igualdade racial em Parelheiros, incluindo o coletivo Escritureiros. Mantém uma página homônima no Facebook8 onde são divulgadas notícias sobre os eventos realizados e de interesse local acerca das temáticas de gênero, raça e periferia, de modo semelhante aos sites anteriormente mencionados. Caracteriza-se como um grupo que valoriza a ancestralidade africana: o termo "Abayomi Aba" significa "encontro agradável nascido numa quinta-feira" na língua nigeriana Iorubá. Também congrega a Biblioteca Carolina de Jesus do CEU Parelheiros, grupo Militantes Negros, o Centro de Defesa dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente (CEDECA) de Interlagos, o grupo Juventude Politizada de Parelheiros e o Coletivo Rusha Montsho. O Coletivo Rusha Montsho9, por sua vez, conta com participantes que atuam em outros coletivos, dedicando-se a temas voltados à sexualidade, gênero e valorização da cultura e identidade afro-brasileira. Seus projetos abrangem desde ações de conscientização sobre raça e sexualidade em escolas a eventos esportivos nas ruas de Parelheiros. Mantém uma página homônima no Facebook10 na qual divulgam os eventos que organizam e notícias locais. Também realizam eventos na Casa de Cultura de Parelheiros e na Biblioteca Comunitária Caminhos da Leitura.

4 Análise do escopo das narrativas de coletivos negros na Internet sob a perspectiva interseccional

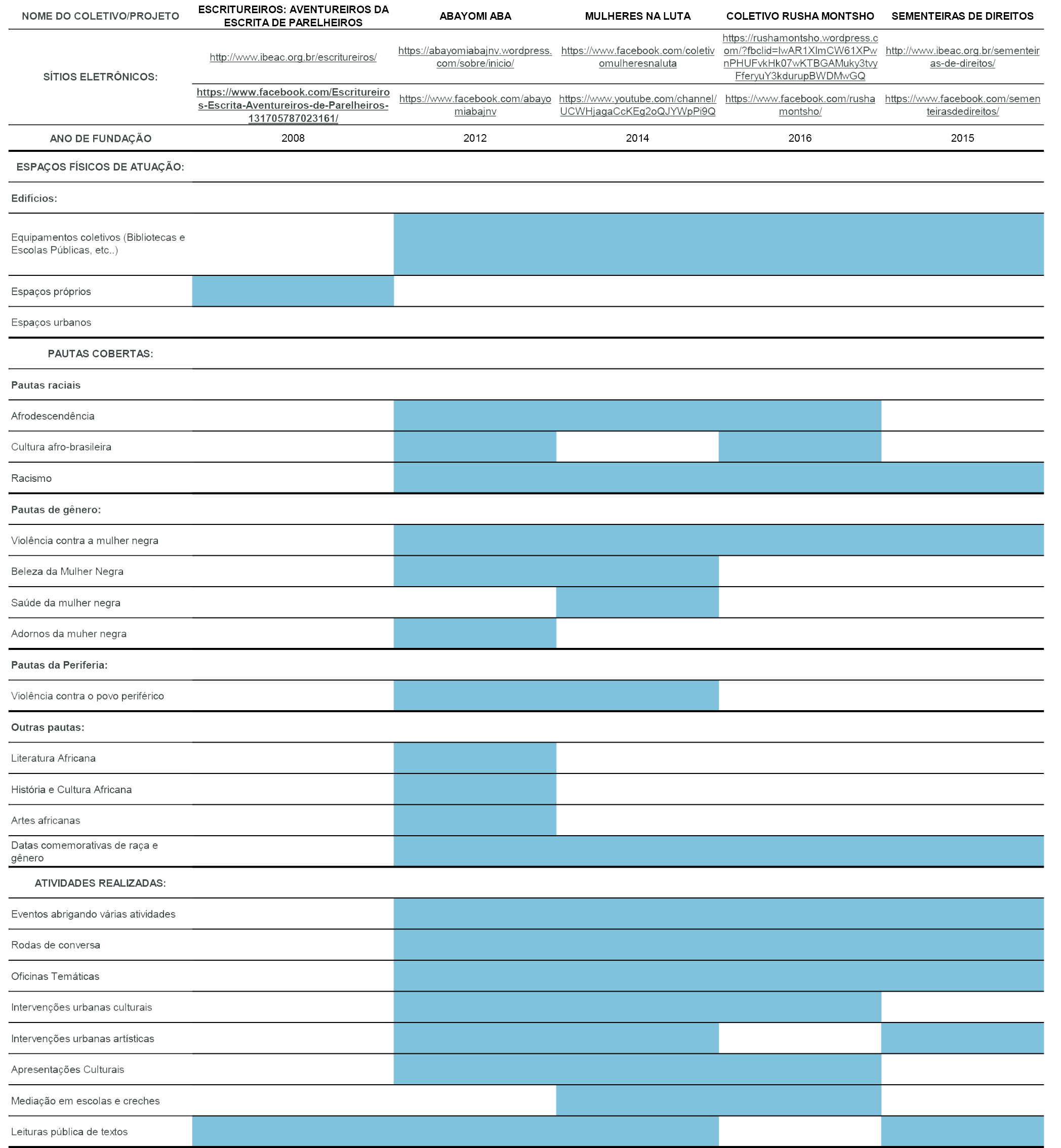

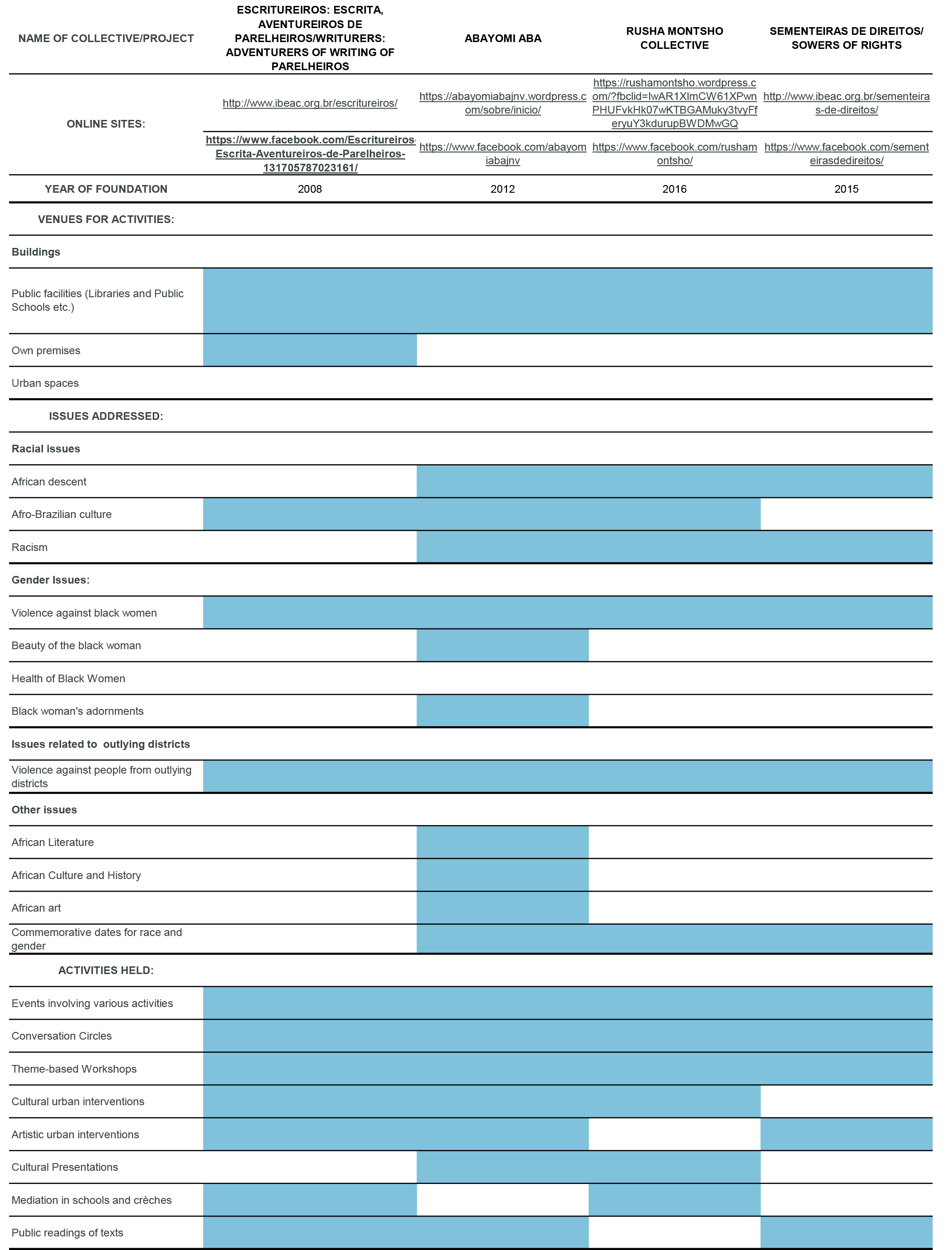

O escopo das atividades e vivências descritas nas narrativas e discursos dos sites e páginas eletrônicas dos coletivos escolhidos como objeto deste estudo foram agrupados em categorias de análise, como é possível observar no Quadro 1 (abaixo), desdobrando-se em três grupos de abordagens: Espaços Físicos de Atuação; Pautas Cobertas e Atividades Realizadas. As pautas abordadas foram organizadas em quatro conjuntos: a) pautas raciais que, por sua vez, desdobram-se em temas ligados à afrodescendência, à cultura afro-brasileira e ao racismo; b) pautas de gênero, que abordam a violência contra a mulher negra e a beleza, a saúde e adornos da mulher negra; c) pautas da periferia: Violência contra o povo periférico; equipamentos e infraestrutura na periferia; d) outras pautas relacionadas à educação e cultura, compreendendo: Literatura Africana; História e Cultura Africana; Artes africanas; Datas comemorativas de raça e gênero. Em relação às atividades realizadas, verificaram-se alguns dos formatos de eventos organizados pelos coletivos para disseminar suas práticas: Rodas de conversa; Oficinas Temáticas; Intervenções urbanas culturais; Intervenções urbanas artísticas; Apresentações Culturais; Mediação em escolas e creches; Leituras públicas de textos.

Quadro 1: Uso dos espaços urbanos, edifícios x atividades realizadas pelos coletivos negros em Parelheiros. Fonte: Elaborado pelas autoras, 2021.

Destacam-se três aspectos significativos, no que se refere às interfaces entre a presença e ação das mulheres negras na Internet e os territórios que ocupam em Parelheiros. São eles: o uso dos espaços urbanos; o uso dos equipamentos coletivos de educação e cultura; as pautas — divulgadas pelas páginas eletrônicas —, promovendo projetos educativos, culturais e artísticos associadas à reivindicação por serviços e infraestrutura pública de educação, saúde e segurança. É possível notar que os espaços urbanos e equipamentos coletivos que abrigam essas atividades não se localizam, necessariamente, em Parelheiros ou em outras regiões periféricas. Existem também equipamentos culturais de uso público como Instituições e Centros Culturais localizados em diversas regiões da cidade, ainda que predominantemente na região Sul de São Paulo, como o SESC e o CEDEC, ambos em Interlagos, e o Centro Cultural Santo Amaro.

Uma proporção significativa do conteúdo dos sítios e páginas eletrônicas dos coletivos analisados aponta para problemas derivados do "silenciamento das periferias", reflexo da ausência de estudos e reconhecimento governamental dos números específicos e das formas de violência que afetam as pessoas negras de modo mais intenso. As pautas são promovidas também nos espaços digitais por meio de campanhas de doação e conscientização em clubes de trocas, bem como por meio da divulgação de eventos, de projetos culturais, artísticos e educacionais, e demais notícias ligadas às pautas aqui descritas. A potência da escrita, seja pela expressão literária, poética, artística, seja pela expressão em postagens nas redes sociais, aparece de modo recorrente como um importante recurso de presença, de reivindicação de atenção, engajamento e credibilidade. Como é possível ler na página do Facebook das Sementeiras de Direitos ao divulgar o projeto "Vozes Daqui: de Parelheiros para o Mundo":

Vozes Daqui é sobre dar luz à comunicação como direito! Direito esse que transpõe a narrativa limitada ao acesso à informação! Trata-se de amplificar a voz pela expressão escrita, fazendo ecoar a palavra no território e fora dele pelo uso deste meio de comunicação. É vociferar o território-abundância que é Parelheiros pela escrevivência da gente-potência daqui! (SEMENTEIRAS DE DIREITOS, 2020, n. p.)

As pautas subjacentes residem nos contextos periféricos de exiguidade e inadequação de espaços públicos ao ar livre, equipamentos coletivos de educação, cultura e saúde. Cabe enfatizar que as páginas digitais analisadas permitem notar o importante papel desempenhado pelos eventos realizados dentro e fora de Parelheiros, a maioria localizada na Zona Sul paulistana. Com efeito, um dos tópicos abordados de forma recorrente consiste na exclusão das habitantes da periferia dos serviços e infraestruturas, que servem melhor a habitantes de regiões centrais. Em especial no caso de Parelheiros, a insuficiência da rede de transportes públicos torna o trajeto para outras regiões da cidade difícil, demorado e caro, consistindo em uma barreira significativa ao acesso dessas comunidades a áreas mais centrais.

5 Considerações finais

A espacialização dos dados relativos à população negra em São Paulo apresentada neste artigo expressa a intensa desigualdade socioespacial no território urbano, ilustrando como a precariedade habitacional é maior em locais majoritariamente habitados por pessoas autodeclaradas negras. Em Parelheiros, esta precariedade afeta particularmente as mulheres e meninas: o distrito é recordista em casos de gravidez na adolescência e de violência contra a mulher. Nesse contexto, o registro das vozes das mulheres e meninas negras de Parelheiros na Internet constitui-se em fonte de conhecimento sobre como as condições, tanto sociais como territoriais, articulam-se e afetam suas vidas e seus destinos cotidianamente.

Alguns tópicos recorrentes nos quatro sítios eletrônicos analisados — dos coletivos Escritureiros, Sementeiras de Direitos, Abayomi Aba e Rusha Montsho — apontam para a relevância da perspectiva interseccional estabelecida a partir do feminismo negro: as discussões sobre raça, afrodescendência e a cultura afro-brasileira; as particularidades da saúde da mulher negra e as diferentes violências sofridas por elas; a beleza e os adornos das mulheres negras; e a cultura, arte e história africanas. O pano de fundo dessas narrativas é sempre o território, por isso a condição periférica tem papel de destaque, quase protagonismo. A violência contra o povo periférico e a precariedade e insuficiência dos equipamentos e infraestrutura urbanos são tópicos permanentemente presentes nestas narrativas. Trataria-se de um aspecto local que sinaliza um sintoma geral? Possivelmente. Como Santos, Araújo e Baumgarten ponderaram, as narrativas do Sul Global parecem estar sempre sujeitas "à extenuante posição de reação" (2016, p. 18): a periferia em relação ao centro, a alternativa em relação à tradição.

Os circuitos hegemônicos das publicações universitárias, editoras e periódicos tradicionais adotam formas discursivas estruturadas aos moldes das recentes exigências de internacionalização da ciência. Estas exigem que os estudos apresentem resultados que possam ser embalados para apresentação em língua inglesa (SANTOS, ARAUJO, BAUMGARTEN, 2016). Este é, entretanto, um universo muitas vezes estranho à experiência das mulheres periféricas, cujos saberes, memórias, culturas e narrativas acontecem e são narrados em outras dimensões. Sob as perspectivas epistemológicas do Sul Global, torna-se possível compreender, por meio dos relatos veiculados em sítios na Internet, seus valores individuais e comunitários. Isso porque essas mulheres oferecem informações sobre seu território por meio de perspectivas e narrativas que são visíveis e perceptíveis apenas a partir de suas próprias experiências. O conhecimento que produzem origina-se das circunstâncias que lhes são próprias: dos obstáculos e oportunidades que dão sentido às suas vidas e às suas vivências, e que apontam para e criação dos caminhos de transformação dos territórios em que vivem.

Agradecimentos

Este trabalho foi desenvolvido com apoio da CAPES por meio do Programa de Excelência PROEX e do Programa Institucional de Internacionalização PRINT, pelo qual as autoras expressam aqui seus agradecimentos. As autoras são igualmente gratas a Leticia Becker Savastano, pela revisão dos textos em português e inglês.

Referências

ABAYOMI ABA. Abayomi Aba: pela Juventude Negra Viva. Abayomi Aba Wordpress. Disponível em: https://abayomiabajnv.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR3_Ek1gJXWhq_QWG-3P_Ua8LtzlsgpVkaPxfBzOTeM121KZhTzPr371Zxk. Acesso em: 21 Nov. 2020.

AKOTIRENE, C. Interseccionalidade. São Paulo, SP: Sueli Carneiro; Pólen, 2019.

ALLEN, A. Feminist Perspectives on Power. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Disponível em: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminist-power/. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

AMNB. Articulação das Mulheres Negras Brasileiras. AMB.org. Disponível em: https://amnb.org.br/. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2020.

BLOGUEIRAS NEGRAS. Blogueiras Negras: Informação para fazer a cabeça. Blogueiras Negras.org Disponível em: http://blogueirasnegras.org. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

BROTO, V.C.; ALVES, S.N. Intersectionality challenges for the co-production of urban services: notes for a theoretical and methodological agenda. Environment & Urbanization, 2018, Vol. 30 (2): 367-386. Disponível em: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956247818790208. Acesso em: 13 Nov. 2020.

CARTA das Mulheres Negras 2015. Marcha das Mulheres Negras 2015 contra o Racismo, a Violência e pelo Bem viver. Portal Geledés 18/11/2015. Disponível em: https://www.geledes.org.br/carta-das-mulheres-negras-2015/. Acesso em: 25 Nov. 2020.

CARNEIRO, F. F.; RIGOTTO, R. M.; PIGNATI, W. Frutas, cereais e carne do sul: agrotóxicos e conflitos ambientais no agronegócio no Brasil. In: FERNANDES, L.; BARCA, S. E-cadernos - Desigualdades Ambientais: Conflitos, Discursos e Movimentos. Universidade de Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Sociais, n. 17, p. 10-29, julho-agosto-setembro. 2012. Disponível em: https://journals.openedition.org/eces/1101. Acesso em: 23 Mai. 2020.

CEERT. Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades. Ceert.org. Disponível em: https://ceert.org.br. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

CRENSHAW, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. In: BARTLETT, K. T. Barlett; KENNEDY, R.(eds.), Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender, Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1991a.

CRENSHAW, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, Stanford Law Review, Vol.43, N.6. 1991, p. 1241-1299. 1991b.

CRIOLA. C. Criola.org. Disponível em: https://criola.org.br/onepage/quem-somos/.Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

ESCRITUREIROS. Escritureiros. Ibeac.org. Disponível em: http://www.ibeac.org.br/escritureiros/. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

PORTAL GELEDÉS. Portal Geledés: Instituto da Mulher Negra. Geledés.org. Disponível em: https://www.geledes.org.br. Acesso em: 21 Nov. 2021.

HOFMANN, S; DUARTE, M. C. Gender and natural resource extraction in Latin America. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, January-June, 2021, N. 111. P. 39-63. Disponível em: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/48621865.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fbasic_expensive_solr_cloud%252Fcontrol&refreqid=excelsior%3A4fc674da5293eee8f1e0b0f64a74c424. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

IBEAC. Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos e Apoio Comunitário. Ibeac.org. Disponível em: http://www.ibeac.org.br/sobre-o-ibeac/missao/. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

IBGE. Censo Demográfico. Tabela 3175 - População residente, por cor ou raça, segundo a situação do domicílio, o sexo e a idade. Sidra-Ibge, 2010. Disponível em: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/3175. Acesso em: 01 Out. 2021.

LIMA, E. F. O Fazer-interseccional no trabalho de educação em sexualidade. Revista do Centro de Pesquisa e Formação No. 8, Julho, 2019. P. 95-102 Disponível em: https://www.sescsp.org.br/files/artigo/ce71e77c/e409/4c9f/b5df/07fd66a58bf8.pdf. Acesso em: 10 Nov. 2020.

MULHERES NA LUTA. Post de 12 de fevereiro de 2019. Facebook. Disponível em: < https://www.facebook.com/coletivomulheresnaluta. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

NUNES, L. Nos últimos pontos de ônibus de São Paulo. Agência Mural. São Paulo, 30 de maio de 2019. Disponível em: https://www.agenciamural.org.br/parelheiros-onibus-zona-sul-de-sao-paulo/. Acesso em: 15 Set. 2019.

REDE NOSSA SÃO PAULO. Mapa Da Desigualdade Da Primeira Infância. São Paulo, 2020. 51 p. Disponível em: https://www.nossasaopaulo.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Mapa_PrimeiraInfancia-2020-completo.pdf. Acesso em: 10 Nov. 2020.

RIBEIRO, D. O que é lugar de fala. Belo Horizonte: Letramento: Justificando, 2017.

RIGON, A.; BROTO, V. C. Inclusive Urban Development in the Global South. s.l.: Routledge, 2021.

RUSHA MONTSHO. Coletivo Rusha Montsho. Rusha Montsho Wordpress Disponível em: https://rushamontsho.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR2tdgWVcV_MKYnrPxQmy02ehEC7UYKVMMdfgQXAVpOg6XaGDWkcU1Q9XJg. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados - SEADE. Secretaria de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento Regional (org.). ÍNDICE PAULISTA DE VULNERABILIDADE SOCIAL: IPVS versão 2010, 2010. 20 p. Disponível em: http://ipvs.seade.gov.br/view/pdf/ipvs/principais_resultados.pdf. Acesso em: 20 Nov. 2020.

SÃO PAULO (MUNICÍPIO). Plano Diretor Estratégico do Município de São Paulo: lei municipal n° 16.050, de 31 de julho de 2014. Texto da lei ilustrado. São Paulo: Prefeitura Municipal, 2015. Disponível em: http://gestaourbana.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/wp-content/ uploads/2015/01/Plano-Diretor-Estrat%C3%A9gico- Lei-n%C2%BA-16.050-de-31-de-julho-de-2014-Texto- da-lei-ilustrado.pdf. Acesso em: 21 Dez. 2020.

SÃO PAULO (MUNICÍPIO). Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo. Secretaria Municipal de Promoção da Igualdade Racial - SMPIR. Igualdade Racial em São Paulo: Avanços e Desafios: relatório final. São Paulo, 2015. 16 p. Disponível em: https://ceapg.fgv.br/sites/ceapg.fgv.br/files/2017_sp_diverso_igualdade_racial_em_sao_paulo.pdf. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

SÃO PAULO (MUNICÍPIO). Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo. Caderno de Propostas dos Planos Regionais das Subprefeituras: Quadro Analítico - Parelheiros. Dezembro, 2016. Disponível em: https://gestaourbana.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/QA-PA.pdf. Acesso em: 22 Mai. 2020.

SÃO PAULO (MUNICÍPIO). Sistema de consulta do Mapa digital da Cidade de São Paulo. Geosampa. Disponível em: http://geosampa.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/PaginasPublicas/_SBC.aspx. Acesso em: 05 Out. 2021.

SANTOS, B. S.; ARAÚJO, S.; BAUMGARTEN, M.. As Epistemologias do Sul num mundo fora do mapa. Sociologias, Porto Alegre, ano 18, n. 43, set/dez 2016. p. 14-23. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3HMBZGO. Acesso em: 20 Out. 2021.

SEADE. Perspectivas demográficas dos distritos do Município de São Paulo: o rápido e diferenciado processo de envelhecimento. SP Demográfico - Resenha de Estatísticas Vitais do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, ano 14, n. 1, janeiro de 2014. Disponível em: https://www.seade.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/spdemog_jan2014.pdf. Acesso em: 05 Out. 2021.

SEMENTEIRAS DE DIREITOS. Sementeiras de Direitos. Ibeac.org, c.2021. Disponível em: http://www.ibeac.org.br/sementeiras-de-direitos/. Acesso em: 21 Out. 2021.

SEMENTEIRAS DE DIREITOS. Sementeiras de Direitos. Facebook, 4 de abril. c. 2021. Disponível online em: https://www.facebook.com/sementeirasdedireitos/. Acesso em: 01 Out. 2021.

SILVA, C.; RIBEIRO, S. Feminismo Negro. De onde viemos: aproximações de uma memória. In: HOLLANDA, H. B.. Explosão Feminista: Arte, Cultura, Política e Universidade. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018.

1 Portal Geledés: Instituto da Mulher Negra. Disponível em: https://www.geledes.org.br. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

2 O Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades (CEERT). Disponível em: https://ceert.org.br/. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

3 Articulação de Mulheres Negras Brasileiras. Disponível em: https://amnb.org.br. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

4 Blogueiras Negras. Disponível em: blogueirasnegras.org. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

5 Portal IBEAC. Disponível onlineem em: http://www.ibeac.org.br/escritureiros/. Acesso em: 01 Nov.2020 e Página Escritureiros Escrita Aventureiros de Parelheiros no Facebook. Disponível em: https://www.facebook.com/Escritureiros-Escrita-Aventureiros-de-Parelheiros-131705787023161/. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

6 Portal IBEAC. Disponível online em: http://www.ibeac.org.br/sementeiras-de-direitos/ Acesso em: 01/11/2020 e Página Sementeiras de Direitos no Facebook. Disponível em:https://www.facebook.com/sementeirasdedireitos/. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

7 Portal Abayomi Aba. Disponível online em:https://abayomiabajnv.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR27sGptg-kxjphQKl49ZwCbrQx38YWVAUmoLs1DVIO-OpAYdRxi63BnSog. Acesso em: 01/11/2020

8 Página do coletivo Abayomi Aba no Facebook. Disponível em:https://www.facebook.com/abayomiabajnv/. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2020.

9 Portal Coletivo Rusha Montsho. Disponível em:https://rushamontsho.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR1aGFBs7g4oKlZDzuicoPq71Fn3gMrcEMpW_i9oswrE8o6RtVsLcDaf7zQ. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2021.

10 Página do Coletivo Rusha Montsho no Facebook. Disponível online em:https://www.facebook.com/rushamontsho/about/?ref=page_internal. Acesso em: 01 Nov. 2021.

The voices of Afro-Brazilian women from Parelheiros: the Internet and intersectionality

Ana Gabriela Godinho Lima is an Architect and Urbanist, and Doctor in History of Education and Philosophy of Knowledge, with a Post-doctoral stage in Arts. She is an Associate Professor of the Graduate Program of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Brazil, where she is co-responsible for the Research Project "City, Gender and Childhood". She is the author of the book "Arquitetas e arquiteturas na América Latina do século XX" (Altamira Editorial, 2013). She studies Architecture of schools, Architecture and Urbanism Teaching, History of Women in Architecture, History of Architecture in Latin America, History and Theory of Contemporary Architecture, Design Processes in Architecture, and Urbanism and Design. anagabriela.lima@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/2010070403291740

Angélica Aparecida Tanus Benatti Alvim is an Architect and Urbanist, Doctor in Architecture and Urbanism. She is a Full Professor of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Brazil, and the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism of the same institution. She is the leader of the research group Contemporary Urbanism: networks, systems and processes, where she conducts research on urban design, mobility, and environment. angelica.alvim@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/3698530751056051

Jaqueline de Araujo Rodolfo is an Architect and Urbanist and holds a Master's degree in Architecture and Urbanism. She is a research group Contemporary Urbanism: networks, systems and processes of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Brazil. She studies urban interventions, urbanization programs, precarious settlements, dimensions of sustainability, environment and springs in the Metropolitan Region of Sao Paulo, Brazil. jaqueline.rodolfo@mackenzie.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/9553533340324968

How to quote this text: Lima, A. G. G; Alvim, A. T. B.; Rodolfo, J.A., 2021.The voices of Afro-Brazilian women from Parelheiros: the Internet and intersectionality. Translated from Portuguese by Andrew Davis. V!RUS, 23, December. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus23/?sec=4&item=6&lang=en>. [Accessed: 30 June 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST, 15, 2021

Abstract

This study explores the discourses of the Afro-Brazilian women of Parelheiros — one of Sao Paulo city´s most impoverished and violent neighborhoods — disseminated via Internet websites. The methodology entailed surveying websites addressing issues related to race, underserved outlying districts, gender, and problems faced by women in Parelheiros. Then we built a theoretical framework for analysis involving four main themes: intersectional feminism, Afro-Brazilian women´s voices on the Internet, the context of Parelheiros, and positioning the discussion within the framework of the Global South epistemologies. The results revealed that the dissemination of different forms of written expression via the Internet has become a tool for overcoming the so-called “silencing of the underserved outlying districts”, enabling the development of networks for solidarity, organizing of events, and the running of training and empowerment projects. Also, Afro-Brazilian women´s voices disseminated over the Internet expressed needs and aspirations, both personal and collective, which would be difficult to convey by other means. The accounts describing the way urban spaces can provide and promote – yet also hamper and impede – opportunities for these women serve to portray the ways social, economic, racial, and gender inequalities are experienced and tackled by these groups and their communities.

Keywords: Global South, Afro-Brazilian women, Parelheiros, Intersectionality, Internet

1 Introduction

The voice of black women is rarely heard or taken into account in the processes of planning, designing, and implementing interventions in urban communities in the cities of the Global South, characterized by diversity and inequality (Broto and Alves, 2018; Rigon and Broto, 2021). As these communities develop, specific groups emerge through programs and techniques stimulating and exploiting active practices of management of individuality and building of identities, personal ethics, and collective alliances (Rose, 1999 cited in Rigon and Broto, 2021). In this sense, the writings of black women from underserved outlying districts disseminated on Internet sites can be seen as a strengthening tool, a means of conferring meaning to the sense of self of these women, and also for aiding the development of networks for support, training, and creativity. The present study analyzes the written discourses of the Afro-Brazilian women of Parelheiros, a neighborhood located on the Southern outskirts of São Paulo city, that has one of the highest levels of poverty and violence in the region. From an intersectional perspective, we observe how the living experiences in these urban spaces impact the life opportunities and experiences of these protagonists.

The analysis of these discourses draws on the epistemological framework of the Global South, as defined by Santos, Araújo, and Baumgarten (2016). These approaches challenge the “exclusions produced by Eurocentric concepts” (p. 20, our translation) and regard the question “of production and circulation of knowledge and epistemology” (p.14, our translation) as central to the decolonial debate. Hofmann and Duarte (2021) also observe that feminist authors from the Global South identify, in development policies, a continuation of patriarchal colonialism. With their extractivist dynamics, these policies trample territories and bodies. In this respect, the current discussion places black female authors as epistemic subjects that “produce, interact and share their knowledge” (Hofmann and Duarte, 2021, p. 44, our translation) on the territories in which they live.

The methodological steps followed were: firstly, a survey of online sites addressing issues related to race, underserved outlying districts, and gender in Parelheiros was conducted based on the narratives of Afro-Brazilian women. The survey centered on the experiences and reflections which arise through interaction with built or urban environments. Examples include, on the one hand, narratives of meetings in libraries and classrooms, activities performed in the street or public squares, and, on the other hand, accounts and reflection on the experiences of violence, fear, discrimination, or difficulties involving the lack of urban infrastructure and facilities. Subsequently, a theoretical framework comprising four themes was devised to analyze the resultant narratives: intersectional feminism, the voice of Afro-Brazilian women on the Internet, the context of Parelheiros, and the positioning of the discussion within the context of the production and circulation of knowledge in the Global South.

On the first theme, the discussion addressing intersectional feminism is underpinned by the theories of Allen (2016), Akotirene (2019), and Silva and Ribeiro (2018). The focus of this analysis, from the intersectional feminism perspective, centers on specific issues experienced by Afro-Brazilian women in the district of Parelheiros, bringing to the fore the way in which racism and sexism interact as a mechanism of oppression. On the second theme, the analysis of the voice of Afro-Brazilian women on the Internet draws on both the concepts of the work of Silva and Ribeiro (2018) and on the discussions promoted by sites including the Centro de Estudos das Relações de Trabalho e Desigualdades (CEERT - Center for the Study of Labor Relations and Inequalities), Articulação de Mulheres Negras Brasileiras (AMNB - Articulation of Brazilian and Afro-Brazilian Women) and Blogueiras Negras (Afro-Brazilian Bloggers). Based on this analysis, the role of the Internet in the dissemination and circulation of discourses of Afro-Brazilian women from underserved outlying suburbs, generally blocked by the mainstream channels of publication, will be elucidated. The third theme entails characterizing the situation of social and territorial vulnerability in Parelheiros, particularly with regard to racial and gender aspects. To this end, a search of government sources of data was carried out, including the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Estatística (IBGE - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), the Plataforma Municipal Geosampa (Geosampa São Paulo City Platform) and the Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados (SEADE - Foundation State Data Analysis System). The fourth theme of investigation places the discussion in the context of the epistemologies of the Global South, as outlined by Santos, Araújo, and Baumgarten (2016) and by Hofmann and Duarte (2021), shedding light on the epistemic subjects invisible in the perspective of the key conceptual and intellectual principles based on the values of the Global North. Within this framework, from the decolonial perspective, it is possible to acknowledge the importance of the voices of Afro-Brazilian women of Parelheiros over the Internet not only for the analysis of the aspects of the territory they live in but also in terms of their role as active participants of a network of voices derived from different areas of social and territorial vulnerability in the Global South. It is considered that these women knowledge is pivotal to devising effective territorial interventions in these areas, as emphasized by Broto and Alves (2018) and Rigon and Broto (2021).

1.1 Addressing intersectional feminism

The intersectional perspective lays bare mechanisms of oppression that cannot be perceived through other lenses. The dynamic of coproduction of cities reveals that the use and control of infrastructures and resources in urban areas reflect the hegemonic structures of power (Allen, 2016). These dynamics give rise to different forms of violence, stemming from a failure to recognize specific ways of life and problems experienced on an individual level (Broto and Alves, 2018). Intersectionality is situated in the ambit of black feminism, whose foundations have been built by black female authors since the 19th century. Maria W. Stewart, Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, and Sojourner Truth distinguished racism and sexism as different mechanisms of oppression. By mutually articulating and strengthening each other, these mechanisms give rise to problems that are specific to black women and who experience them in a way white women and black men do not (Allen, 2016).

The term “intersectionality”, coined by the Afro-American intellectual Kimberlé Crenshaw, appeared in two papers published in 1991: Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics and Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color (Allen, 2016). The academic popularity of these texts grew following the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (2001) held in Durban, South Africa, albeit running the risk of being changed “from the originally intended meaning to the point of becoming devoid of it” (Akotirene, 2019, p. 13-14, our translation). In the Brazilian milieu, back in the late 1970s, the intellectual Lélia Gonzalez was dealing with issues involving class, race, and gender oppression, alerting to the intersectionality (without using the term) of these forms of violence. In parallel, Afro-American sociologist Patricia Hill Collins used the concept to denote the work of black female activists and researchers in Brazil and Latin America. However, according to Silva and Ribeiro (2018), the ideas of Gonzalez did not enjoy the recognition and impact they deserved, perhaps because they emerged during a decade with scant means of dissemination and communication. This would explain why a large contingent of young black feminists credits Crenshaw with creating the concept of intersectional feminism.

The debate broadened by intersectional perspective inspired protagonists such as the Brazilian philosopher and activist Sueli Carneiro to set up the Portal Geledés – Instituto da Mulher Negra (Geledés Platform - Institute of Afro-Brazilian Women)1. Regarded as the most prominent black organization in the 1990s and 2000s (Silva and Ribeiro, 2018, p. 254), the website is considered a “forum for public expression of their achievements past and present [...]" (Portal Geledés, 1997 – 2021). As a vehicle for disseminating information, the Geledés platform was visionary in recognizing the importance of this channel of communication as a way of countering the dominant narratives, paving the way for other black women´s organizations that employ the Internet to communicate. This is exemplified by the Criola2 and Blogueiras Negras (Black Bloggers)3 websites (Silva and Ribeiro, 2018). The Internet and social media platforms served to consolidate the popularization of black feminism, largely because their protagonists were able to reach the public without having to overcome the barriers of academic approval or major publishing houses. Via these communication channels, the narratives of these women, albeit mothers and homemakers, vulnerable women from the northeastern region of the country, transsexuals, and youths who never completed high-school education can be voiced (Silva and Ribeiro, 2018), providing a glimpse of worlds that were hitherto invisible.

1.2 Voices of Afro-Brazilian women on the Internet

The last few decades have seen a growing presence of young black feminists on channels of communication. Traditional broadcast TV and news portals now feature protagonists who have benefited from the channels opened up by the fight of organizations representing black women since the 1980s. Prior to this shift, these protagonists had made important inroads in the areas of education and culture, public policy-making, and other areas of knowledge (Silva and Ribeiro, 2018). This provided the bedrock for the development of the Geledés site, in addition to the key websites of the CEERT, the AMNB, and Blogueiras Negras.

The São Paulo-based CEERT4 was set up in 1992 by Hédio Silva Jr., Ivair Augusto Alves dos Santos and Maria Aparecida Silva Bento. As a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), it “produces knowledge, and develops and executes projects aimed at promoting race and gender equality” (CEERT, 2002 – 2021, our translation). It is involved in the areas of education and race, as well as in congresses and forums, school actions, and student exchange programs through institutions, such as the British Council. With an emphasis on gender issues, the CEERT runs projects such as Enfrentamento da Violência Contra as Mulheres (Tackling Violence Against Women), with specific focus on race, in collaboration with the Avon Institute and the Assessoria para a Equidade de Raça e Gênero (Advisory on Race and Gender Equity) program, together with the Fundação Itaú Social (Itaú Social Foundation).

The portal AMNB website5 brings together 29 organizations from all over Brazil. Their mission is: “to promote coordinated political action of groups and NGOs representing Afro-Brazilian women” (AMNB, 2021), seeking to combat racism, sexism, and class oppression. The site maintains a map of the location of its member organizations, together with contact details and information on their respective fields of action (AMNB, 2021). The organization is currently run by the Centro de Estudos e Defesa do Negro no Pará (CEDENPA – Center for Study and Defense of Black People in Pará State), by the Instituto de Mulheres Negras de Mato Grosso (IMUNE – the Institute of Afro-Brazilian women of Mato Grosso State), by N'Zinga – Coletivo de Mulheres Negras de Belo Horizonte (Collective of Afro-Brazilian Women of Belo Horizonte), by Odara - Instituto da Mulher Negra (the Institute of Afro-Brazilian Women) and by the Rede de Mulheres Negras do Paraná (RMNPR – Network of Afro-Brazilian Women of Paraná State). Created to strengthen and amplify the visibility of culture production, the online platform Blogueiras Negras, founded in 2012, originated from the Blogagem Coletiva da Mulher Negra (Collective Blog of Afro-Brazilian women) with the goal of increasing the visibility of a large body of literature by black authors. Comprising a 1300-strong community of women, the platform gathers the writings of 200 black authors aimed at combating racism, lesbophobia, transphobia, homophobia, and fatphobia. Forms of cultural output covered by the site include blogs, videos, books, and audio tracks which also promote and celebrate the culture of African descendants (Blogueiras Negras, 2020).

The four sites demonstrate the strengthening of the organization of black communities over the past few decades during which, in Brazil alone, a large number of events took place supporting these initiatives. One of the most notable was the Marcha das Mulheres Negras 2015 contra o Racismo e a Violência e Pelo Bem Viver (2015 March of Afro-Brazilian Women against Racism and Violence and For Well Being), a Brazilian movement which mobilized 50,000 women to march on Brasilia. A Carta das Mulheres Negras (The Letter from Afro-Brazilian Women) from 2015, was published on the Portal Geledés to mark the event. Its demands included securing by the State and society of the right to life and freedom; promotion of racial equality; the right to work, employment, and protection of black workers across all sectors; the right to the Land, Territory, and Housing; and the Right to the City, in addition to rights to social security, education, justice, culture, information and communication, and public safety (Portal Geledés, 2015).

2Territorial and social vulnerability situation in Parelheiros: race and gender

According to the last Census by the IBGE (2010), 37% of the 11,253,503 population of São Paulo city self-reported as black (brown and black). These data, according to gender stratification, revealed a predominance of black women, totaling 2,130,240 subjects, or 51’% of the total population self-reporting as black. Although the city´s black population does not represent the majority in terms of self-reported race (61% white, 37% black, and 2% yellow), the spatial map of the population depicted in Figure 1 below shows the density of specific groups in sub-prefectures of the city. The three main districts with the greatest density of black and brown individuals are Parelheiros (57.1%), M’Boi Mirim (56%), and Cidade Tiradentes (55.4%) (São Paulo, 2015). The three regions with the highest number of white individuals and with fewer than 15% black individuals are the districts of Pinheiros, Vila Mariana, and Santo Amaro (São Paulo, 2015).

Fig. 1: Map of the density of black people by Sub-prefecture and housing conditions in São Paulo city. Source: Produced by the authors, 2021, based on CENSO IBGE census 2010, the GeoSampa Platform, and a survey carried out by the Municipal Secretariat for the Promotion of Racial Equality of São Paulo City Hall (2015)

This spatial distribution of the city population, together with the location of precarious settlements (overcrowded housing, informal settlements, and irregular housing), reveals major socio-spatial inequality. This mapping process shows that the greater the percentage of black people, the greater the number of precarious settlements. This scenario is mirrored by the Sub-prefecture of Parelheiros, comprising the districts of Marsilac and Parelheiros with a density of 57.1% self-reported black population in a context of conflicts between urban inequality and environmental protection. This sub-prefecture constitutes the largest in terms of land area in São Paulo city, with an area measuring 353.5 Km2, or 23.68% of the city, and a local population numbering 150,000 inhabitants.

Situated in the Southern tip of the city and predominantly rural in nature, as consolidated by the last Strategic Master Plan for São Paulo of 2014 (Municipal Law 16.054/2014), the sub-prefecture of Parelheiros nestles between Guarapiranga and Billings reservoirs,10 km away from the Serra do Mar mountain chain. The land contains important Areas of Environmental Protection (APA), such as the Capivari-Monos APA and Bororé–Colônia APA conservation zones, in addition to the indigenous Guarani villages of Krukutu and Barragem. The population density of its constituent districts is low, at 825 inhabitants/km² for Parelheiros and 41 inhabitants/km² for Marsilac, relative to high-density districts, e.g. those situated in the Sé sub-prefecture such as Bela Vista with 26,715 inhabitants/km2. Given its status as an area of environmental protection, the region has a marked concentration of precarious sites, particularly in the district of Parelheiros, which has a medium-high level of social vulnerability according to the Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social (IPVS - São Paulo City Social Vulnerability Index) produced by the Fundação Seade (Seade Foundation) (São Paulo, 2010). These data illustrate, through the mix of demographic and socioeconomic conditions, the specific factors which lead to a deterioration in living conditions, such as low levels of average income, education, family life cycle, ability to join the job market, and access to goods and public services.

In terms of mobility, the district has a longer than average commuting time to the city of over 1 hour, with the most commonly used mode of travel being public transport, followed by private vehicle or on foot (São Paulo, 2016). According to Nunes (2019), in 2018, only six bus lines served the district and, of these, only three traveled as far as the city center, involving a journey time of up to three hours. The substandard public services also have repercussions on gender-based statistics. The district ranks amongst the highest in cases of teenage pregnancy — 17% of live births were to mothers aged 19 years or younger (SEADE, 2014) —, has a shortage of hospitals and beds; and numbers among the forty worst for poor prenatal care (Rede Nossa São Paulo, 2018).

3 Voices and experiences of the Afro-Brazilian women and girls of Parelheiros: the essential data for urban policy-making

The voices and experiences of the Afro-Brazilian women and girls of Parelheiros find in the collective websites a means of gaining visibility, expanding support and collaboration networks, and attaining recognition and credibility. In the present study, the following groups in Parelheiros were found via their social media networks: the collectives Escritureiros and Sementeiras de Direitos; the Abayomi Aba collective, an initiative which brings together a number of other black collectives from the São Paulo's Southern region, promoting actions through collaborations and partnerships; and the Rusha Montsho collective, which brings together protagonists who were previously engaged in individual actions or belonged to other collectives and, thus, already have experience in racial and gender issues. Rather than examining the array of thematic initiatives dealt with by these collectives, the goal was to select a sample that allowed identification of recurrent issues from the discourses, narratives, and experiences of the Afro-Brazilian women and girls from Parelheiros. The analysis of these narratives is underpinned by the recognition of their relevance in informing urban policies.

The first two websites analyzed were the Escritureiros6 and Sementeiras de Direitos7 collectives, respectively. Both these sites are hosted on the digital platform of the Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos e Apoio Comunitário (IBEAC – Brazilian Institute of Community Studies and Support), an NGO engaged in promoting human rights through community projects that strengthen citizenship. Their actions are guided by the principles of sustainability and replicability (IBEAC, 2021). In this respect, the page of the Escritureiros collective is dedicated to outlining the activities of the group, set up in 2008, and comprising adolescents and youths dedicated to education in human rights and exchange of knowledge. The collective runs literary projects and activities promoting local culture. The collective is also responsible for the management, mediation, and coordination of the Caminhos da Leitura (Reading Paths) Community Library, promoting activities of reading mediation in schools, crèches, and literary events. The group's activities are disseminated via the Facebook page called “Escritureiros: Escrita, Aventureiros de Parelheiros”. The main aim is to encourage writing and reading on the issues of gender, race, and life in the underserved outlying districts as a theme underlying the activities run.

The Sementeiras de Direitos collective is a group centered on raising awareness and providing support for women who are victims of gender-based violence. The main focus is the narrative and deconstruction of gender stereotypes and prejudice, with effort dedicated to educating women for social entrepreneurship in Parelheiros (IBEAC, 2021). The group´s actions are disseminated on the Facebook page of the same name, often in partnership with the Escritureiros collective, which also carries news of local interest on the themes of gender, race, and life in the poor outlying districts. Annually, the collective holds editions of the Sementeiras de Direitos Week, conducting conversation circles and workshops on the issues of women´s rights and safety.

The collective Abayomi Aba Pela Juventude Negra Viva8 (Abayomi Aba for the Alive Black Youth) works towards strengthening political coordination between collectives aimed at culture and promoting racial equality in Parelheiros, including the Escritureiros collective. It has a Facebook page with the same name9 which carried news on the events run and of local interest on the issues related to gender, race, and life in the underserved outlying suburbs, similar to the sites outlined above. The group celebrates African ancestry: The term "Abayomi Aba" stands for “pleasant meeting arising on a Thursday” in the Nigerian language Yoruba. The collective also includes the Carolina de Jesus Library, in CEU Parelheiros, the Militantes Negros (Black Militants) collective, the Centro de Defesa dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente (CEDECA - Center for the Defense of Children's and Adolescents' Rights) of Interlagos, the Juventude Politizada de Parelheiros (Politicized Youth of Parelheiros) group and the Rusha Montsho Collective. The Rusha Montsho Collective10 is made up of members from other collectives and is centered on issues related to sexuality, gender, and celebrating Afro-Brazilian identity and culture. The group´s projects range from awareness actions on race and sexuality in schools to sports events on the streets of Parelheiros. The collective has a Facebook11 page with the same name, where it announces events organized and publishes local news. It also holds events at the Casa de Cultura (Cultural Center) of Parelheiros and at the Caminhos da Leitura (Community Library).

4 Analysis of the scope of narratives of black collectives on the Internet from an intersectional perspective

The scope of activities and experiences described in the narratives and discourses from the sites and online pages of the collectives selected as the focus of this study were grouped into three categories for analysis, as depicted in Chart 1 (below): Infrastructure for Activities; Issues Addressed and Activities Run. The issues addressed were subdivided into four groups: a) racial issues, further broken down into topics related to African descent, Afro-Brazilian culture, and racism; b) gender issues, encompassing violence against black women, and health and beauty of black women; c) issues involving life in the underserved suburbs: Violence against dwellers of underserved outlying districts; equipment and infrastructure in the outlying districts; and d) other issues related to education and culture, including African Literature; African History and Culture; African arts; and Commemorative dates for race and gender. With regard to the activities run, some of the event types organized by the collective to disseminate their activities include Conversation circles; Theme-based Workshops; Cultural urban interventions; Urban art interventions; Cultural presentations; Mediation in schools and crèches; Public readings of texts.

Table 1: Use of urban spaces, buildings x activities run by black collectives in Parelheiros. Source: The authors, 2021.

Three main aspects stand out with regard to the interfaces between the presence and action of Afro-Brazilian women on the Internet and the territories they occupy in Parelheiros, namely: the use of urban spaces; use of public education and culture facilities; the issues addressed — disseminated via pages online —, promoting educational, cultural and art projects associated with the call for public services and infrastructure for education, health, and safety. It is evident that the public urban spaces and equipment supporting these activities are not always located in Parelheiros itself or in other outlying districts. There are also cultural facilities for use by the public, such as Cultural Institutions and Centers situated in different places throughout the city, mainly in its Southern region, such as the SESC and CEDEC, both in Interlagos, and the Santo Amaro Cultural Center.

A large proportion of content on the sites and online pages of the collectives analyzed cite the problems stemming from the “silencing of the underserved outlying suburbs”, the result of a lack of studies and government recognition of the specific figures on and forms of violence faced by black people to a disproportionate degree. The issues are also promoted online through donation and awareness campaigns in swap meets, and also via announcements of upcoming events, cultural, art, and educational projects, plus other news related to the agenda outlined. The power of writing, whether in the form of literary, poetic, artistic expression, or posts on social networks, featured consistently as an important tool to confirm a presence, call for attention, engagement and credibility. To exemplify, the following text can be found on the Facebook page of the Sementeiras de Direitos collective, promoting the Vozes Daqui: de Parelheiros para o Mundo project (Voices From Here: from Parelheiros to the World):

Vozes Daqui is about making communication a right! A right that goes beyond the limited narrative on access to information! This involves amplifying the voice through written expression, making the word reverberate within the territory and beyond it, via this means of communication. It is to vociferate the territorial abundance that is Parelheiros by the living writing of the empowered from here! (Sementeiras de Direitos, 2020, our translation).

The underlying issues involve the contexts of the underserved urban outskirts with a lack of adequate outdoor public spaces, public facilities for education, culture, and health. The results of the analysis of the online pages illustrate the pivotal role played by the events run within and outside Parelheiros, particularly in São Paulo city´s Southern region. Consequently, one of the topics most commonly addressed is the limited access to services and infrastructure by dwellers of the outlying districts, while residents of the central regions are better served. More specifically in the case of Parelheiros, the inadequate public transport services render travel to other regions of the city difficult, slow and expensive, representing a major barrier for the local populace to accessing more central areas.

5Final considerations

The spatial distribution of data on São Paulo's Afro-Brazilian population presented in this article highlights the major socio-spatial inequality in the urban land area, illustrating that the standards of housing are worse in regions occupied predominantly by individuals who self-report as black. In Parelheiros, these poor conditions have the greatest repercussions on women and young girls: the district has the highest rates of teenage pregnancy and violence against women. In this context, registering the voices of Afro-Brazilian women and girls from Parelheiros on the Internet constitutes a valuable source of knowledge on how the conditions, both social and territorial, interact and impact their daily lives and destinies.

Some recurrent topics evident on the four online sites surveyed — the Escritureiros, Sementeiras de Direitos, Abayomi Aba, and Rusha Montsho — show the importance of the intersectional perspective established from black feminism: discussions on race, African descent, and Afro-Brazilian culture; the particularities of the health of black women and the various forms of violence they suffer; the beauty and embellishment of black women; and African culture, art, and history. The backdrop of these narratives is always territorial, and hence the stigma of residing in the underserved outskirts remains front and center, almost protagonist. Violence against residents of the underserved outlying districts and the poor state and the lack of urban infrastructure and facilities are recurrent topics in these narratives. Could this be a local problem signaling a broader malaise? Perhaps. As Santos, Araújo, and Baumgarten pondered, the narrative of the Global South always appears to be subject to “the extenuating position of reaction” (2016, p. 18): the outskirts relative to the center, the alternative as opposed to the traditional.

The hegemonic circuits of University publications, publishing houses, and traditional journals adopt structured discursive forms in conformance with the recent requirements for internationalizing science. These standards require studies to report results that can be packaged for a presentation in English (Santos, Araujo and Baumgarten, 2016). This universe, however, is often far removed from the reality of women from the underserved outlying districts, whose knowledge, memories, cultures, and narratives take place, and are narrated, in other dimensions. From the epistemological perspective of the Global South, it is possible to gain a clearer picture, through the accounts disseminated on Internet sites, regarding the individual and community values of these women. This is because they provide information on their territory via perspectives and narratives which are visible and perceived only from their personal experiences. The knowledge they produce derives from the circumstances which are inherent to them: barriers and opportunities which confer meaning to their lives and experiences, and which call for the creation of ways of transforming the territories in which they live.

Acknowledgment

This work was developed thanks to the support of CAPES, through the PROEX Excellence Program and the PRINT Institutional Internationalization Program, to which the authors express their gratitude. The authors are equally grateful to Leticia Becker Savastano, for proofreading the texts in Portuguese and English.

References

Abayom Aba, 2020. Abayomi Aba: pela Juventude Negra Viva. Abayomi Aba Wordpress, [online] Available at: https://abayomiabajnv.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR3_Ek1gJXWhq_QWG-3P_Ua8LtzlsgpVkaPxfBzOTeM121KZhTzPr371Zxk. [Accessed 21 Nov. 2020].

Akotirene, C., 2019. Interseccionalidade. São Paulo, SP: Sueli Carneiro; Pólen.

Allen, A., 2016. Feminist Perspectives on Power. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 Edition), [online]. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminist-power/. [Accessed 01 Nov. 2020].

AMNB, 2021. Articulação das Mulheres Negras Brasileiras. AMB.org. [online] Available at: https://amnb.org.br. [Accessed 21 Oct. 2020].

Blogueiras Negras, 2020. Blogueiras Negras: Informação para fazer a cabeça. Blogueiras Negras.org [online] Available at: http://blogueirasnegras.org. [Accessed 21 Oct. 2020].