Além da representação: possibilidades das novas mídias na arquitetura

Ana Paula Baltazar é Doutora em Arquitetura e Ambientes Virtuais, Professora Adjunta da Escola de Arquitetura da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais e pesquisadora do grupo Morar de Outras Maneiras (MOM_UFMG) e do Laboratório Gráfico para Experimentação Arquitetônica (Lagear_UFMG).

Como citar esse texto: BALTAZAR, A. P. Além da representação: possibilidades das novas mídias na arquitetura. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 8, dezembro 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus08/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Este artigo começa por uma leitura da representação no contexto da arquitetura distinguindo entre representação na arquitetura (arquitetura que representa significados) e representação da arquitetura (concepção do projeto separado do trabalho de construção e do uso). Em seguida mostra como o paradigma perspectívico, fundado no Renascimento, foi sendo consolidado na era moderna, consolidando também a prevalência do espaço concebido sobre o espaço vivido. Com a cultura informacional espera-se a superação do paradigma perspectívico, que não acontece por não haver mudança no modo de produção capitalista do espaço. Ou seja, ainda que fosse possível reverter a perda de dimensões advinda com a representação, a mudança de paradigma só aconteceria se houvesse uma mudança radical no modo de produção. Assim, a promessa de superação do paradigma perspectívico com o paradigma informacional é discutida a partir de três tendências atuais do uso de computadores na arquitetura, enfocando a predominância da lógica da representação em detrimento de um real desenvolvimento do processo de produção da arquitetura que enfatize o espaço vivido sobre o concebido. O artigo conclui apontando a possibilidade da arquitetura como interface superar o paradigma perspectívico, mudando o foco da representação para a interatividade.

Palavras-chave: representação; arquitetura; novas mídias; interatividade; interface.

Introdução

Re:pre:sentar, tema desta V!RUS 8, tem uma definição bastante ampla, conforme proposto na chamada de trabalhos do periódico:

A palavra vem do latim repraesentare e contém dois prefixos. O primeiro é re-, que significa 'para trás', sugerindo a reiteração de algo, e o segundo é prae-, que significa adiante, antes de, e remete a algo que ainda estaria por vir. Os dois prefixos encontram-se ligados ao verbo sedere, cujo significado de assentar, sentar, designa o que se estabelece, o que se define. Desse ponto de vista, RE:PRE:SENTAR envolve, ao mesmo tempo, um gesto relacionado à pré-existência, ao que já havia ou que já foi (re-), associa-o a um olhar sobre o que ainda não é, ao que pode vir a ser (pre-), e transforma o ato de definição, de estabelecimento, de permanência (sentar) (V!RUS, 2012, s.p.).

No processo de produção da arquitetura convencional podemos dizer que re:pre:sentar reitera algo concebido antes (projeto), remete a algo que estaria por vir (espaço construído), e estabelece um estado de permanência (a arquitetura pronta, acabada). Contudo, tal processo deve ser questionado, uma vez que podemos imaginar uma arquitetura que não se fixe em estado permanente e cuja produção não seja pautada pela reiteração do espaço concebido com sua separação clara da construção e do uso. A ênfase no espaço vivido escapa à representação. As novas mídias, principalmente a computação física (analógico-digital), apontam para a possibilidade de superação da representação no processo de produção da arquitetura. Contudo, tal superação não é tarefa fácil. O histórico da relação entre representação e arquitetura não pode ser simplesmente desprezado, mas entendido para que seja possível superar suas limitações e vislumbrar a possibilidade de apropriação das novas mídias além da reprodução do processo convencional de projeto baseado na representação perspectívica. A partir do entendimento da representação na e da arquitetura é possível questionar o que vem sendo tomado como mudança de paradigma na era informacional e apontar uma possibilidade real de mudança de paradigma no processo de produção da arquitetura. Trilhando esse caminho crítico da representação e das novas mídias, a interatividade passa a ser valorizada por meio da possibilidade de se pensar arquitetura como interface, um processo que tem continuidade durante o uso, e não mais arquitetura como representação, espaço concebido, pronto, acabado.

Sobre a representação na e da arquitetura

Para Roland Barthes (1991, p. 228), a palavra representação teria dois significados. “Representação designa uma cópia, uma ilusão, uma figura análoga, um produto-semelhança; mas no sentido etimológico, representação é meramente o retorno do que já foi apresentado”. Representação pode ser lida assim, em seu sentido misto, como o que presenta o objeto novamente através de seu produto-semelhança, não apenas presentando o próprio objeto de novo, mas presentando-o através de outro meio. Assim, tem-se a representação na arquitetura e a representação da arquitetura.

No caso da representação na arquitetura, é a arquitetura que deve representar. Numa analogia com a linguagem, a arquitetura seria o discurso, o habitar que depende da representação. Para Alberto Pérez-Gómez e Louise Pelletier (1992, s.p.),

uma arquitetura simbólica é aquela que representa, aquela que pode ser reconhecida como parte de nossos sonhos coletivos, como um lugar de pleno habitar. [...] Assim, a criação enquanto representação deve ser o objetivo fim do trabalho arquitetônico se é que a nossa profissão tem algum significado social.

Na visão desses autores, os elementos da arquitetura devem expressar o simbolismo que representam. A arquitetura é carregada de significação por representar uma intenção, um caráter, além das referências sócio culturais. A arquitetura é então o meio através do qual diversas relações são representadas simbolicamente. “A arquitetura tradicional constrói a representação” (PEIXOTO, 1993, p. 362).

Na passagem do Medievo para o Renascimento, com o advento da imprensa de Gutenberg, foi pela primeira vez questionado o papel da arquitetura como meio para representar significado. Victor Hugo escreveu que o livro mataria o edifício (HUGO, 1993 [1831], p. 148). Contudo, o questionamento provou-se vão, pois o livro não só não matou o edifício, como o edifício vem reinventando, ao longo da idade moderna, diferentes formas de representar significado. No pós-modernismo, por exemplo, Robert Venturi chegou ao limite de exaltar edifícios comerciais que representavam literalmente os produtos que vendiam, como o quiosque de cachorro quente que reproduz inclusive a mostarda em sua aparência (Figura 1).

Figura 1. Tail o’ the Pup, quiosque de cachorro quente construído originalmente em 1945, no Beverly Boulevard, em Hollywood. Projeto do arquiteto Milton Black em 1938. Fonte: blog do Los Angeles Times.

Contudo, prevalece na discussão sobre representação e arquitetura a representação da arquitetura, ou seja, a maneira como o objeto arquitetônico é reduzido em sua dimensão perceptiva e dado à leitura. Os desenhos da arquitetura serão considerados sua representação, como também o serão a fotografia, o vídeo, os modelos, enfim, tudo que guarde uma relação de aparência com o objeto, mas que não faça ver o objeto enquanto fenômeno, senão representação do fenômeno (HEIDEGGER, 1990).

Numa analogia da arquitetura com a linguagem, a representação da arquitetura é sua escrita, e sua língua, seu código, funda-se no paradigma perspectívico, como apontado por José dos Santos Cabral Filho (1996, p. 26):

A perspectiva não influenciou apenas a arquitetura e as disciplinas artísticas, mas também deu origem ao pensamento científico moderno. A técnica perspectívica foi um instrumento conceitual para abordar o mundo. O aparato perspectívico estrutura o mundo e torna-o um ambiente passivo, de uma descrição precisa, uma representação verdadeira e portanto aberta à análise científica. A perspectiva torna-se um paradigma para a certeza, racionalidade e conhecimento objetivo.

Podemos encarar a perspectiva como o paradigma da representação desde o Renascimento, quando do começo de sua utilização. A perspectiva surge historicamente no Renascimento, embora diversos autores defendam que Vitruvius já apresentava os princípios da perspectiva em seu tratado sobre arquitetura (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992, 1997).1 Mas é no Renascimento que começa a ser discutida a questão da representação da arquitetura, e também levantadas questões relacionadas “às dificuldades envolvidas na concepção da arquitetura em termos de um conjunto de projeções bidimensionais” (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992, s.p.). A alteração do processo de produção da arquitetura tem início com a possibilidade de representação e a criação da profissão do arquiteto para isso. Assim, a prática arquitetônica começa a sofrer modificação a partir do estabelecimento do paradigma perspectívico, no Renascimento.

A arquitetura medieval não lidava com desenhos da forma como fazemos hoje, e os construtores não concebiam o edifício como um todo, era um processo coletivo in loco que geralmente durava mais que uma geração, ou seja, quem começava a obra não estava mais vivo quando de seu término. Antes do Renascimento, a arquitetura desconhecia a escala gráfica, que só ganhou importância quando da possibilidade de representação, devido à necessidade de precisão na redução, para a projetação da arquitetura.

Ainda que o Renascimento seja o grande marco histórico da alteração do modo de produção da arquitetura, caracteriza-se como transição entre as soluções arquitetônicas pré-renascentistas e a arquitetura a partir do modernismo. A arquitetura renascentista em si não expressa grande parte das vantagens da representação arquitetônica sobre o modo de produção in loco. A perspectiva era ainda entendida como a ciência ótica, como transmissão de raios de luz.

A pirâmide de visão, noção na qual se baseava a ideia renascentista da imagem como uma janela no mundo, foi herdada da noção euclidiana do cone de visão. [...] Era impossível para o arquiteto renascentista conceber que a verdade do mundo pudesse ser reduzida a sua representação visual, uma seção bidimensional da pirâmide de visão (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992, s.p.).

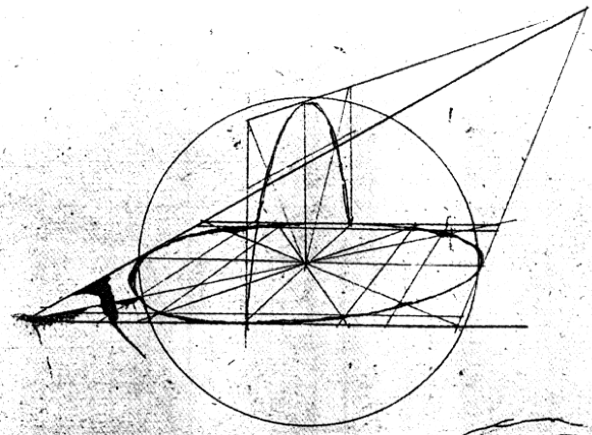

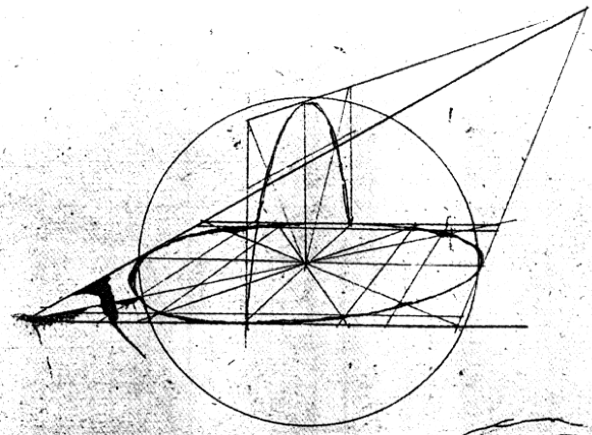

Na verdade, a representação perspectívica da arquitetura encontrou maior divulgação nas pinturas do século XV, que procuravam representar o ambiente com maior precisão. Embora os pintores fizessem uso da perspectiva (Figura 2), ainda não havia nenhuma sistematização geométrica. Leon Battista Alberti introduziu em seu tratado Della Pictura a perspectiva como fundamento para o desenho artístico. O método perspectívico começou então a ser delimitado, reduzindo-se a visão binocular a um ponto de vista apenas, que por analogia, seria o vértice do cone de visão. Um plano interceptava o cone, e tinha-se assim uma projeção do cone num plano, mas ainda não havia consideração sistemática da profundidade, como mostra a ilustração de Albrecth Dürer retratando o método descrito por Alberti (Figura 3).

Figura 2. Parte do mural “A Santíssima Trindade, a Virgem, São João e os doadores”, Masaccio, Santa Maria Novella, Florença, pintado por volta de 1427. Fonte: arquivo pessoal.

Figura 3. Ilustração de Albrecht Dürer retratando o método de projeção cônica descrito por Alberti em De La Pictura. Fonte: PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992.

Apenas no século XVI é que os tratados sobre perspectiva começaram a sistematizar o método empírico. Vignola fundou o método do ponto de distância, introduzindo como que na linha do horizonte um segundo observador com a mesma distância do ponto central, permitindo a representação da profundidade (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1997); Dürer fez uso de equipamentos perspectívicos que permitiam um método rigoroso para representar os objetos; Desargues estabeleceu o ponto no infinito como encontro de duas retas paralelas, ao contrário de seus antepassados, que acreditavam que o vértice do cone de visão era o ponto de convergência de duas retas paralelas, tornando possível a sistematização do método perspectívico enquanto um sistema geométrico análogo ao de retas concorrentes, fundando em sua teoria, as bases da geometria descritiva desenvolvida no fim do século XVIII por Gaspar Monge. Assim, a representação perspectívica foi sendo sistematizada e lentamente foi se estabelecendo a possibilidade da utilização da geometria, da bidimensionalidade e das projeções ortogonais na concepção da arquitetura.

1 Pérez-Gómez e Pelletier (1997) apontaram a polêmica em torno das traduções de Vitruvius, concluindo que ele não se referia à perspectiva em seu tratado.

Por muito tempo, podemos dizer até o Modernismo, a representação arquitetônica não foi levada ao limite, não foi amplamente utilizada em seu potencial.

Os desenhos renascentistas não são simplesmente o mesmo que os desenhos modernos em sua relação com o lugar construído. Planos e elevações não eram ainda sistematicamente coordenados dentro dos padrões da geometria descritiva. Estes desenhos não eram instrumentais, e mantinham muito mais autonomia com relação ao edifício do que os que resultam da prática contemporânea. (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992).

O Movimento Moderno, pregando racionalização e objetividade, levou ao limite a utilização da representação arquitetônica, racionalizando os espaços, resolvendo em projeto as possibilidades de otimização da arquitetura, muitas vezes negligenciando conhecimentos construtivos. Como apontaram Pérez-Gómez e Pelletier (1997, p. 220–221) a separação entre projeto e construção é consagrada no século 18, tendo como referência o arquiteto Jean-Laurent Legeay (1710-1786), que “preconizava a virtuosidade de uma ideia sobre seu potencial construtivo” (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1997, p. 220). A tradição iniciada nessa época foi a da predominância da imagem global do edifício para sua visualização, permitida com a perspectiva, “implicitamente sugerindo que o conhecimento de construção não seria responsabilidade do arquiteto” (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1997, p.221). O Modernismo, de certa forma, coroou o modo de produção da arquitetura via representação e deu continuidade a esse processo de separação entre projeto e construção que já se encontrava incorporado na prática arquitetônica.

A grande contribuição do estabelecimento do paradigma perspectívico para a arquitetura foi a instituição da representação, alterando completamente o processo de produção. A representação possibilitou a previsão na arquitetura, por permitir a redução do objeto arquitetônico à bidimensionalidade do meio onde é trabalhado. Assim como a perspectiva, outras formas de representar o objeto foram surgindo — como a fotografia, que foi inventada em 1839, e posteriormente o vídeo — baseadas no mesmo princípio de um ponto de vista, no mesmo paradigma. “Quando um artista emprega a perspectiva geométrica ele não desenha o que ele vê — ele representa sua imagem da retina” (GREGORY, 1990, p. 174). A imagem que se forma na retina não é a imagem interpretada pelo cérebro. A retina seria o meio bidimensional onde a imagem vista é representada; e o cérebro interpreta as duas imagens das retinas, fundindo-as numa nova dimensão. A representação perspectívica faz com que se perca a dimensão da profundidade, que é presente na imagem do mundo, conforme a percebemos.

Pérez-Gómez (1994) argumentou que a profundidade era a primeira dimensão antes do domínio do paradigma perspectívico. Posteriormente as outras duas dimensões — comprimento e largura — fizeram com que a profundidade se tornasse meramente uma dentre as três dimensões. A redução da importância da profundidade afetou a relação espaço/tempo por causar a perda do valor da imagem — a imagem que vemos, como percebemos o mundo. Tanto a fotografia quanto o vídeo, considerados representação perspectívica2, assim como a própria perspectiva, não são suficientes para a experiência da arquitetura, pois abandonam a profundidade, apenas representando-a, e com isso contribui para que se perca a relação espaço/tempo.

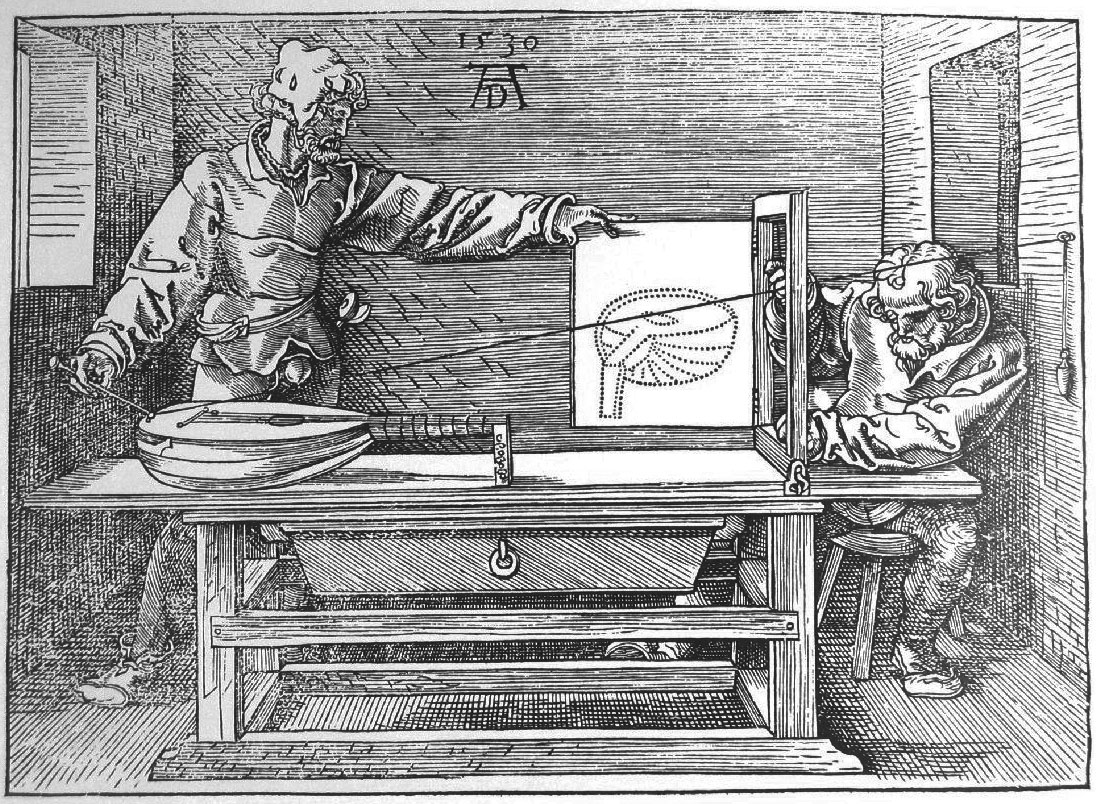

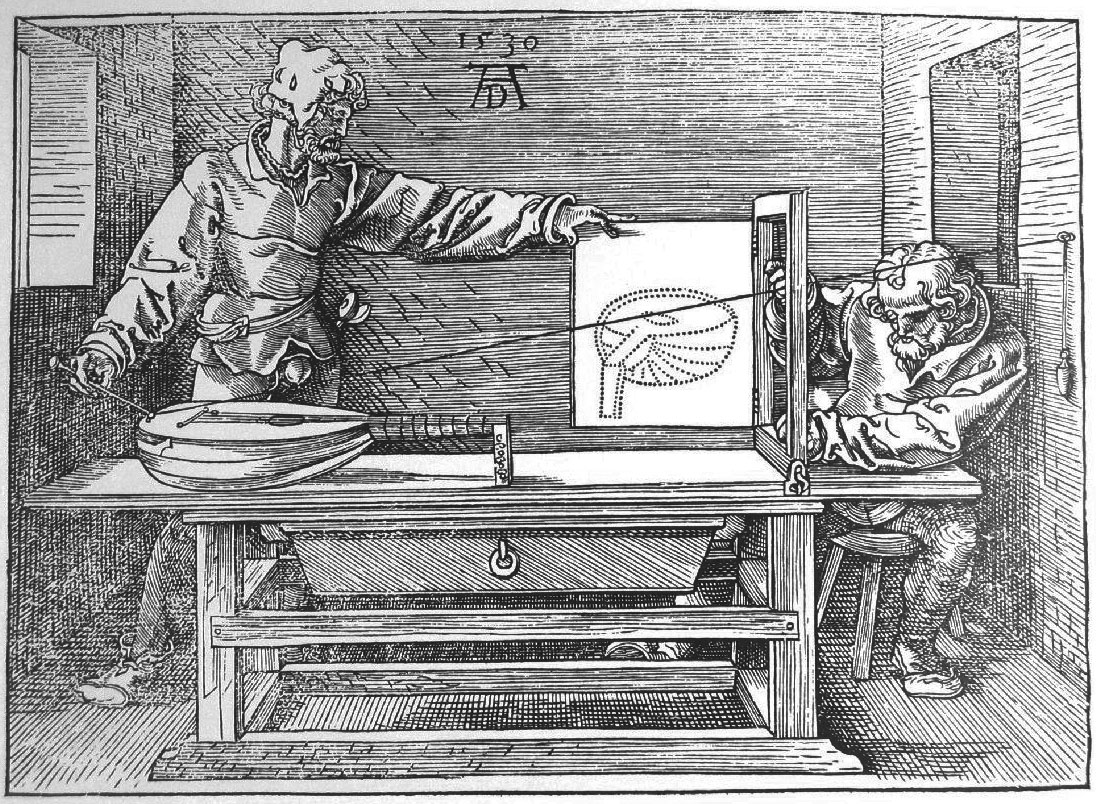

Quando nos colocamos diante de uma representação perspectívica, não somos nós que vemos o mundo, mas os olhos de um outro. A imagem que nos chega é a imagem de um dos olhos deste outro. Já não temos mais referência do momento enquanto possibilidade de apreensão espacial e temporal, nem mesmo somos capazes de dizer da duração, enquanto espaço e tempo vividos. O que temos é uma imagem, absoluta, que se encerra numa janela fora de seu contexto espaço-temporal. Tal janela não mais se abre para o mundo, apenas representa um instante do mundo para o qual se abriu. Uma gravura de Dürer, “O pintor estudando as leis do esboço por meio de fios e uma moldura” (GOMBRICH, 1988, p. 276) (Figura 4), revela a simplificação que a perspectiva impõe ao objeto. Todas as linhas de profundidade do objeto são reduzidas a um esquema de pontos planificado numa janela, numa moldura.

Figura 4. O pintor estudando as leis do esboço por meio de fios e uma moldura, Dürer, 1525, xilogravura. Fonte: DÜRER, 1532.

A perspectiva tem sido encarada como a “possibilidade de representar precisamente um ambiente tridimensional em um plano bidimensional” (CABRAL FILHO, 1996, p. 26). Observando a gravura de Dürer pode-se levantar dúvida acerca desta dita precisão. A gravura ilustra as diversas concessões perceptivas que são feitas para ajustar a cena à sua representação. O observador é reduzido a um olho, além de sua posição ser fixa e o objeto ser estático. A precisão perspectívica é a precisão da ciência, da matemática, que transforma a realidade em modelos para que possa ser analisada. Assim, podemos considerar uma possível precisão da perspectiva e da geometria descritiva cientificamente, já que permite uma avaliação do objeto representado e as limitações do método são conhecidas pelos cientistas. Contudo, da mesma maneira que os modelos matemáticos não são entendidos por quem não conhece o método envolvido, a representação perspectívica ou geométrica também não é entendida por quem não conhece o método perspectívico. Assim, a precisão da perspectiva só é válida à luz da capacidade de imaginar a hipotética profundidade, que se encontra desenhada em comprimentos e distâncias.

O processo de representação resume-se à redução do objeto tridimensional a um meio bidimensional para tornar possível sua re-presentação. No caso da representação da arquitetura, não se trata apenas de tornar a presentar um objeto tridimensional num meio bidimensional. A defasagem entre a arquitetura e sua representação bidimensional não é apenas de uma dimensão. Não podemos considerar a arquitetura um objeto tridimensional, temos a certeza de pelo menos mais duas dimensões — tempo e comportamento — e, portanto, a representação perspectívica está três dimensões aquém da arquitetura.

A primeira dimensão que se perde na representação perspectívica é a profundidade. A maneira como percebemos o mundo, estereoscopicamente, é reduzida à bidimensionalidade do comprimento e da largura. A segunda dimensão perdida é a do tempo. Assim como a escrita, a perspectiva é uma busca de inscrição do discurso, permanecendo como um fragmento de um instante do evento (acontecimento) inscrito fora do tempo. A representação é uma imagem absoluta que pode ser lida em qualquer tempo e não traz a temporalidade do objeto. Demanda um tempo para ser lida, embora não guarde nenhuma relação temporal com o discurso. A terceira dimensão que se perde é a comportamental, que permite a interação. A perspectiva, por ser inscrição, já não é mais um evento, e a significação da arquitetura não se revela no ato de habitar (fruir), mas está restrita à possibilidade de interpretação do fragmento — imagem absoluta — que foi inscrito. Não há interação, o espaço e o tempo não são vividos.

Visando superar a defasagem entre o fenômeno e a representação do fenômeno, devemos entender a limitação do paradigma perspectívico e vislumbrar a possibilidade de novas alternativas.

Embora mesmo que a maioria dos arquitetos mais bem informados reconheçam as limitações dos instrumentos de projeção, tais como plantas, seções e elevações e planejamento prévio com relação ao significado corrente do projeto (obra), nenhuma alternativa é seriamente considerada fora do domínio do perspectivismo moderno, que tem influenciado profundamente nossos conhecimento e percepção (PÉREZ-GÓMEZ; PELLETIER, 1992, s.p.).

Atualmente, em plena cultura informacional, a perspectiva ainda é o paradigma para a arquitetura e sua representação. Para que se altere o paradigma não basta recuperar as dimensões perdidas ou empreender qualquer outro tipo de estratégia reformista no processo de projeto. Além dos problemas apontados acima, o paradigma perspectívico é fundamentalmente perverso por promover o modo de produção capitalista do espaço, que implica a reprodução das relações sociais de produção, a separação entre trabalho intelectual e manual, a consequente separação entre projeto, construção e uso, e a transformação do espaço em mercadoria com ênfase no valor de troca em detrimento do valor de uso. É preciso que se altere o modo de produção, pois, como afirmado por Sérgio Ferro, processo de projeto baseado na representação via desenhos existe e nos chega pronto, porque na lógica capitalista o canteiro de obras deve ser heterônomo. O desenho arquitetônico acaba sendo a forma obrigatória para a extração de mais-valia, sendo assim um instrumento de dominação que visa a produção de mercadorias (FERRO, 2006, p. 108). O uso de computadores na arquitetura ainda não escapou do paradigma perspectívico, em vez de promover o valor de uso com ênfase no espaço vivido, os computadores contribuem para reforçar a produção de mercadorias com ênfase no espaço concebido.

Sobre as novas mídias na arquitetura e a falsa mudança de paradigma

Faz-se necessário entender como a informática entra na arquitetura, pela porta dos fundos, para então entender o motivo de seu atrelamento quase inquestionado ao paradigma perspectívico. Segundo Robert Bruegmann (1989, p. 139), nos anos 50 alguns escritórios de arquitetura nos Estados Unidos já usavam computadores para fazer planilhas e auxiliar nos cálculos estruturais. Contudo, só a partir de meados dos anos 60 surgiu uma interface gráfica interativa permitindo o desenho. No início dos anos 70 o computador parecia promissor, mas a limitação de software e a perspectiva de geração de produtos extremamente racionais acabaram dando origem a uma crítica ferrenha à racionalização, proposta pelo próprio modernismo e que poderia ser levada ao extremo com o uso do computador. Só no fim dos anos 80, já com CAD (projeto auxiliado pelo computador), é que a arquitetura finalmente deu as boas vindas ao computador, que se consolidou nos anos 90 como ferramenta indispensável no processo de projeto convencional. Ainda nos anos 90, com a informatização quase que global dos escritórios e escolas de Arquitetura, principalmente na Europa e na América do Norte, começaram a surgir várias discussões acerca da instauração de um novo paradigma na arquitetura. Tal paradigma seria o informacional e, embora seja realmente uma promessa, ainda não se tornou realidade. Mesmo com Building Information Modelling (BIM) e as possibilidades de parametrização do projeto no século 21, o paradigma representacional continua prevalecendo. O processo de produção da arquitetura ainda é fortemente baseado no espaço concebido, com as tecnologias da informação ainda a serviço da representação e não voltadas para o espaço vivido, para a continuidade do projeto e da construção durante o uso. É interessante notar que o título do artigo de Bruegmann — The pencil and the electronic sketchboard — escrito no fim dos anos 80 já apontava para a reprodução do mesmo processo de projeto representacionista usando o meio eletrônico.

Podemos identificar três tendências da informática no campo da arquitetura: o uso dos tradicionais programas de CAD (predominantemente AUTOCAD para representação e REVIT para parametrização dos elementos representados e compatibilização das representações dos projetos ditos complementares); a investigação e uso de inteligência artificial para geração de desenhos bi e tridimensionais (Shape Grammar e Genetic Algorithms) e a parametrização para fabricação digital; e uma terceira, que pode ser chamada de cibernética, pró-ativa, responsiva ou arquitetura interativa, na qual a informática é parte do espaço e não apenas ferramenta de projeto (facilitada pela computação física).

Na maioria dos casos prevalece o que Pérez-Gómez e Pelletier (1997) chamaram de paradigma perspectívico, e não há de fato uma mudança nem do processo de projeto convencional, nem dos produtos. Ainda que os produtos sejam formalmente (ou volumetricamente) distintos das arquiteturas de outros tempos, a finalidade do processo de projeto continua sendo, predominantemente, a produção de outros produtos acabados, ou como disse Lebbeus Woods (1996, p. 279), “um meio de controlar o comportamento humano e de manter esse controle no futuro”.

Este processo de projeto convencional adotado pelos arquitetos e ensinado nas escolas é, como já dito, fundado no paradigma perspectívico estabelecido no Renascimento e pressupõe a separação entre sujeito e espaço (considerado um objeto a ser representado visualmente). Segundo Pérez-Gómez (1983), a representação que se instaurou no Renascimento foi bastante distinta da que era usada nos canteiros medievais. Ainda que no medievo os desenhos também fossem usados, jamais tinham a pretensão de representar a totalidade do edifício, apenas serviam para comunicar informações relevantes do processo construtivo entre seus diversos participantes e para a elaboração de soluções construtivas.

A diferença fundamental dos dois processos de produção do espaço pode ser resumida pela distinção entre um processo medieval, baseado no que Henri Lefebvre (1991) chamou de espaço vivido, e o Renascentista, baseado no que o autor chamou de espaço concebido (ou representação do espaço). Tal distinção leva ao questionamento do processo de produção instaurado no Renascimento. Segundo Sérgio Ferro (2006, p. 194–195), Brunelleschi mudou radicalmente as relações de produção no canteiro de obras, instaurando uma prática hierarquizada, sistematizando a separação entre trabalho intelectual (projeto via desenhos codificados) e manual (construção via trabalho alienado), e explorando o trabalho para extração de mais-valia. Alberti teorizou tal prática em seu tratado. Obviamente que desde o Renascimento até os dias de hoje os processos de projeto e construção não se mantiveram inalterados, como mostrado por Pérez-Gómez e Pelletier (1997). Contudo, os fundamentos se mantêm preservados: processo de projeto baseado na representação e separação entre projeto, construção e uso.

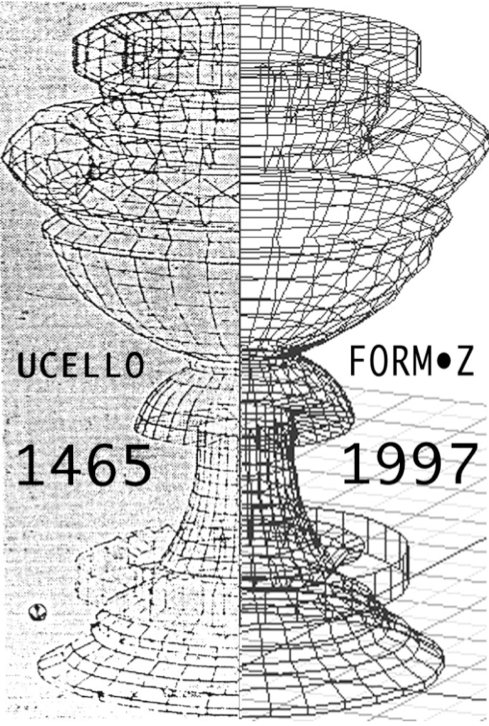

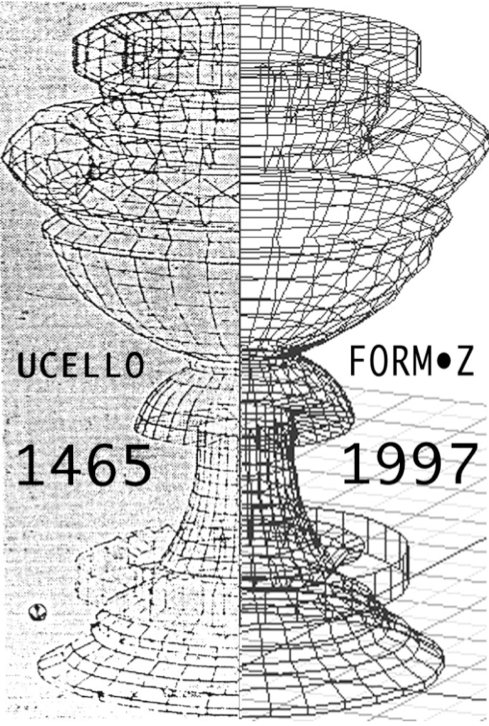

Tal paradigma perspectívico é também a base das três tendências da informática na arquitetura apontadas acima. Os programas de CAD reproduzem em sua lógica estrutural o processo de construção perspectívica Renascentista (Figura 5). Ainda que o façam de forma muito mais rápida e permitam a manipulação em tempo real (como pode ser facilmente feito no Sketch Up, por exemplo), não há nenhuma mudança na lógica de representação. Os programas acabam sendo mais de auxílio à representação (CAR - Computer Aided Representation) do que de auxílio ao projeto (CAD - Computer Aided Design). O projeto, em termos genéricos, continua o mesmo, obedecendo a lógica renascentista de um processo fragmentado que tem como objetivo um produto acabado que será integralmente construído à imagem e semelhança da representação, para então ser usado.

Figura 5. Perspectiva de um cálice, Paolo Uccello, 1450-1465, contraposta a modelamento do mesmo cálice usando Form.Z ,1997. Fonte: arquivo do Lagear.

Ainda que aplicativos como o REVIT permitam a parametrização e apontem possibilidades além da reprodução da lógica convencional de projeto, seu uso ainda restringe-se a auxiliar a representação convencional. Ampliam-se as possibilidades de compatibilização de projetos complementares, por exemplo, mas não se altera em nada a separação renascentista entre projeto, construção e uso. No caso da parametrização para fabricação digital, há certamente um avanço na direção de estreitar a relação entre projeto e construção, principalmente no que diz respeito às propriedades dos materiais e possibilidades formais. Contudo, o foco na representação formal acaba mantendo a separação entre projeto, construção e uso, ainda que de maneira distinta dos processos convencionais. Na maioria das vezes tira-se partido da parametrização para precisar o potencial do material numa forma predeterminada, mas a sua construção acaba sendo um processo industrializado talvez ainda mais alienado que o da construção convencional. Quem trabalha na construção (ou montagem) tem ainda menos possibilidade de intervir criativamente no processo do que em uma obra convencional. Ainda que haja um grande potencial para produção de estruturas móveis, flexíveis e adaptáveis usando parametrização, isso é muito pouco explorado e o uso continua apartado do processo de projeto e construção. A lógica da estruturação perspectívica prevalece.

Os aplicativos que usam inteligência artificial (Shape Grammar e Genectic Algorythms, dentre outros) ainda que não trabalhem literalmente com a estruturação perspectívica, pois usam regras forasteiras para a geração de forma, acabam também levando a produtos que reproduzem a mesma lógica do processo convencional, já que seu principal desenvolvimento tem sido exatamente reproduzir o processo de composição formal dos arquitetos e fazê-lo mais rápido e fornecendo uma gama maior de opções para tomada de decisão, tanto para arquitetos quanto para clientes. A separação entre projeto, construção e uso também prevalece indiscutivelmente nesses processos.

A arquitetura interativa começa a propor algumas alterações, ainda que modestas, no processo convencional. A principal delas sendo o uso da informática — ou novas mídias, como a computação física — não mais para representar o projeto, mas como parte integrante do espaço. Isso aponta para uma possível mudança no processo de projeto, que não é mais voltado para um produto final prescritivo e acabado, mas para um processo aberto que depende da interação do usuário para se completar temporariamente. A esse processo aberto chamo “interface”, e defendo que o ensino de arquitetura e urbanismo seja voltado para a produção de interfaces e não de espaços acabados. Vale ressaltar que nem toda a produção atual de arquiteturas interativas segue a lógica da produção de interfaces. Muitas vezes espaços convencionais são produzidos (com processos convencionais) e sobrepõem-se a eles aparatos interativos para manipulação de imagens ou sons, ou mesmo sensores e atuadores, que prescrevem as ações dos usuários.

Interfaces como possibilidade além do paradigma representacional

2 Gregory (1990) argumentou que a câmera reproduz o objeto como uma perspectiva geométrica, porém nós não vemos o mundo como a imagem perspectívica, o que faz com que a fotografia ou o desenho perspectívico pareçam errados. Para algumas culturas que não tem conhecimento da perspectiva, como os Zulus, uma perspectiva é entendida como uma composição bidimensional.

Ainda que a produção de interfaces possa soar como uma abordagem em substituição ao processo convencional, há que se ter cuidado com tal simplificação. Por serem duas lógicas distintas, não são análogas. Enquanto o processo de projeto convencional é baseado em delimitação e solução de problemas, a abordagem da arquitetura como interface tem como objetivo a problematização de situações, deixando-as abertas para que os usuários deem continuidade. Não há uma clara separação entre projeto, construção e uso, mas a proposição de um repertório interativo, que pode tanto ser uma combinação de peças físicas, interfaces digitais ou híbridas, ou um conjunto de regras. O processo de produção das interfaces obviamente usa desenhos, mas há um deslocamento da representação de seu papel central, paradigmático, e uma ênfase na interatividade. Todavia, representação e interatividade não pertencem à mesma categoria, sendo, portanto, impossível imaginar a substituição de uma pela outra.

Álvaro Siza Vieira resumiu o papel dos arquitetos como o de representar os interesses de seus clientes usando para isso outra representação, que é a arquitetura (BANDEIRINHA, 2010, p. 75). Nesse caso a representação da arquitetura estaria a serviço da representação na arquitetura, explicitando a tradição de projeto contemporânea. Retomando a discussão inicial, pode-se vislumbrar interfaces como possibilidade de superação dos dois processos de representação. Do ponto de vista da representação na arquitetura, tal superação significa o que Cedric Price (1996, p. 483) chama de arquitetura “value-free”, ou seja, uma arquitetura suficientemente abertura para que os usuários deem significado a ela enquanto a completam temporariamente. Do ponto de vista da representação da arquitetura, tal superação significa a perda da ênfase renascentista, ou seja, a representação deixa de ser instrumento de dominação, divisão do trabalho e separação entre projeto, construção e uso. Em ambos os casos não se pode esquecer que a representação é uma ferramenta preciosa e não deve ser excluída da produção da arquitetura como interface, mas deve ser vista como ferramenta que é, e não como paradigma.

Atualmente a computação física (microcontroladores, sensores, atuadores, etc.) aponta para a possibilidade de um processo de produção do espaço cibernético, no qual há continuidade e feedback entre projeto, construção e uso. Diferentemente do papel representacionista que Siza Vieira atribui ao arquiteto, podemos vislumbrar o arquiteto como produtor de interfaces que abram possibilidades para que os usuários configurem seus espaços. A produção de arquitetura como interface indica uma possível mudança de paradigma, do perspectívico (ou representacional) para o informacional, potencializando não só o processo de produção baseado no espaço vivido (e não no concebido) quanto o próprio desenvolvimento da informática que, segundo John Thackara (2000), é atualmente mais voltada para seu próprio desenvolvimento do que para acrescentar valor à vida das pessoas.

Agradecimentos

Gostaria de agradecer às agências de fomento FINEP, CNPq, CAPES e Fapemig por financiar minhas pesquisas, passadas e recentes, que informam esse artigo.

Referências bibliográficas

BANDEIRINHA, J. A. “Verfremdung” vs. “Mimicry”: o SAAL e alguns dos seus reflexos na contemporaneidade. In: SARDO, D. (Ed.). Falemos de Casas: Entre o Norte e o Sul. Lisboa: Athena/Babel, 2010, p. 59–79.

BARTHES, R. The responsibility of forms: critical essays on music, art, and representation. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

BLOG DO LOS ANGELES TIMES. [online] Disponível em: <http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2010/04/tail-o-the-pup-the-landmark-la-hot-dog-stand-still-homeless-.html>. Acesso em: 02 set. 2012.

BRUEGMANN, R. The pencil and the electronic sketchboard: architectural representation and the computer. In: BLAU, E.; KAUFMAN, E. (Ed.). Architecture and its image. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989. p. 139–155.

CABRAL FILHO, J. S. Formal games and interactive design, Tese (PhD), Sheffield University, Inglaterra, 1996.

DÜRER, A. Institutiones geometricae. Trad. Joachim Camerarius. Paris: Christian Wechel, 1532.

FERRO, S. Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006.

GOMBRICH, E. H. A História da arte. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara, 1988.

GREGORY, R. L. Eye and brain: the psychology of seeing. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

HEIDEGGER, M. Being and time. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990.

HUGO, V. The hunchback of Notre-Dame. Ware: Wordsworth, 1993. 1a ed. 1831.

LEFEBVRE, H. The production of space. London: Blackwell, 1991.

PEIXOTO, N. B. O olhar do estrangeiro. In: NOVAES, A. (Org.). O olhar. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1993.

PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, A. The Space of architecture: meaning as presence and representation. In: HOLL, S.; PALLASMA, J.; PÉREZ-GOMEZ, A. Questions of perception: phenomenology of architecture. Architectural and Urbanism, Tóquio, n. 7, jul. 1994. Edição especial.

PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, A. Architecture and the crisis of modern science. Cambridge/Londres: MIT Press, 1983.

PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, A.; PELLETIER, L. Architectural representation beyond perspectivism. Perspecta, Nova Iorque, n. 27, 1992.

PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, A.; PELLETIER, L. Architectural representation and the perspective hinge. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997.

PRICE, C. Life-conditioning. Architectural Design, Londres, v. 36, p. 483, out. 1966.

THACKARA, J. The design challenge of pervasive computing. In: CHI—COMPUTER HUMAN INTERACTION CONGRESS, 2000, The Hague. Disponível em: <http://www.doorsofperception.com/archives/2000/04/the_design_chal.php>. Acesso em: 02 set. 2012.

V!RUS. Chamada de trabalhos. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 7, 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=11&item=1>. Acesso em: 03 set. 2012.

WOODS, L. The question of space. In: ARONOWITZ, S. et al (Ed.). Technoscience and cyberculture. Nova Iorque: Routledge, 1996, p. 279–92.

Beyond representation: possible uses of new media in architecture

Ana Paula Baltazar is PhD in Architecture and Virtual Environments, Associate Professor at the School of Architecture of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, and researcher at the MOM group - Living in Other Waysl and Lagear - Graphics Laboratory for Architectural Experience.

How to quote this text: Baltazar, A. P. Beyond representation: possible uses of new media in architecture. V!RUS, [online] December, 8. Translated from Portuguese by Luis Ribeiro. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus08/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

Abstract

This article begins reviewing representation in the context of architecture, distinguishing between representation in architecture (architecture that represents meanings) and representation of architecture (design separated from construction work and use). Then it shows how the perspectivist paradigm, originated in the Renaissance, was consolidated in the modern era, thus establishing the prevalence of conceived space over lived space. The perspectivist paradigm was expected to be surpassed with the advent of the informational culture, which has not happened because the capitalist mode of production of space has not changed. That is, even if it were possible to reverse the loss of dimensions caused by representation, the paradigm change would only shift if there were a radical change in the mode of production. Thus, the promise of replacing the perspectivist paradigm by the informational paradigm is discussed in the light of three current trends in using computers in architecture, focusing on the prevalence of the logic of representation at the expense of a real development of the process of production of architecture that promotes lived space over conceived space. The article concludes by pointing out the possibility of architecture as an interface to overcome the perspectivist paradigm, shifting the focus from representation to interactivity.

Keywords: representation; new media; interactivity; interface.

Introduction

Re:pre:sent, the theme of V!RUS 8, has a very broad definition, as proposed in the journal’s call for contributions:

The word comes from the Latin repraesentare and contains two prefixes. The first is re-, which means 'backwards', suggesting a reiteration of something, and the second is prae-, which means 'ahead', 'before then', and refers to something that would still be to come. The two prefixes are linked to the verb sedere, meaning 'to seat', 'to sit', designating what is established, defined. From this standpoint, RE:PRE:SENT involves at the same time a gesture related to a pre-existence, to what had or to what has already been (re-), associates it with a look at what is not yet, to what might be (pre-), and transforms the act of definition, of settlement, of permanence (sedere) (V!RUS, 2012, n.p.).

In the context of conventional architecture production, it can be said that re:pre:sentar reiterates something conceived previously (design), refers to something that has yet to come into being (built space), and establishes a state of permanence (ready, finished architecture). However, this process must be questioned, since it is possible to imagine a type of architecture that does not remain the same and whose production is not ruled by reiteration of conceived space with it's clear separation from construction and use. The emphasis on lived space escapes representation. New media – especially physical computing (analogic-digital) – indicate the possibility of overcoming representation in the process of production of architecture. However, to surpass representation is no easy task. The history of the relationship between representation and architecture shall not be ignored, but understood in order to enable us to overcome its limitations and envisage possibilities of appropriation of new media beyond the reproduction of the conventional design process based on the perspectivic representation. By understanding the representation in and of architecture it is possible to question what has been seen as a paradigm shift in the information era and to point to real opportunities for a paradigm shift in the production of architecture. Embarking on this critical path of representation and new media, interactivity becomes important due to the possibility of thinking about architecture as an interface, a process that goes on during use, and not architecture as representation or conceived, ready, finished space.

On the representation inand ofarchitecture

According to Roland Barthes (1991, p.228), the term representation has two meanings: "Representation designates a copy, an ilusion, an analogical figure, a resemblance-product; but in the etimologycal meaning, representation is merely the return of what has been presented". Hence, representation can be understood, in a combined sense, as something that presents the object again via its product-likeness, not just presenting the very object again, but presenting it in other medium. Thus follow representation in architecture and representation of architecture.

In the case of representation in architecture, it is architecture that should represent. In an analogy to language, architecture would be the discourse, dwelling that depends on representation. For Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier (1992, n.p.),

'A symbolic architecture is one that represents, one that can be recognized as part of our collective dreams, as a place of full inhabitation. (...)Thus, creation as representation must be the ultimate objective of architectural work if our profession is to have any social meaning at all.'

According to these authors, architecture elements must express the symbolism they represent. Architecture is laden with meaning because it represents an intention, a character, beyond socio-cultural references. Architecture is, therefore, the means by which several relationships are represented symbolically. “Traditional architecture constructs representation” (Peixoto, 1993, p.362).

In the passage from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, with the advent of the Gutenberg press, the role of architecture was first disputed as a means to represent meaning. Victor Hugo wrote that printing would kill architecture (Hugo, 1993 [1831], p.148). However, his fear proved to be unfounded, for not only has printing not killed architecture, but architecture has reinvented different ways to represent meaning throughout the modern age. In postmodernism, for example, Robert Venturi reached the limit by exalting commercial buildings as literally representing the products they sell, such as the hot dog kiosk that reproduces everything including the mustard on its façade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tail o’ the Pup, hot dog kiosk originally built in 1945, on Beverly Boulevard, in Hollywood. Designed by the architect Milton Black in 1938. Source: Los Angeles Times blog.

However, representation of architecture prevails in the discussion about representation and architecture, that is, the perceptive dimension of architectural objects is reduced for it be given to reading. Architectural drawings are considered to be architecture's representation, as also photographs, videos, models, in short, everything that has an appearance relationship with the object, but that make it be seen as a representation of a phenomenon and not as the phenomenon itself. (Heidegger, 1990)

In an analogy between architecture and language, representation of architecture is writing, and its language, its code; it is grounded on the perspectivist paradigm, as pointed out by José dos Santos Cabral Filho (1996, p.26):

‘Perspective not only influenced architecture and the artistic disciplines, but also gave rise to modern scientific thinking. The perspective technique was a conceptual tool to approach the world. The perspective apparatus frames the world and renders it as an environment passive, of an acurate description, a truthful representation and therefore open to scientific analysis. Perspective becomes a paradigm for certainty, rationality and objective knowledge.’

Medieval architecture did not manage drawings the way we do today, and builders did not conceive buildings in their entirety; it was an in loco collective process that usually lasted more than a generation, i.e., those who started the work were no longer alive when it was finally completed. Before the Renaissance, architecture was unaware of graphic scale, which only gained importance when representation became possible, because of the need for accuracy in reduction, for designing architecture before building it.

Despite the Renaissance being the major milestone of change in the mode of production of architecture, it may be characterized as a transition between pre-Renaissance architectural solutions and architecture from modernism onward. Renaissance architecture itself does not express many of the advantages of architectural representation over in loco production. Perspective was still understood as optical science, as transmission of light rays.

‘The pyramid of vision, the notion on which the Renaissance idea of the image as a window on the world was based, was inherited from the euclidean notion of the visual cone. (...)It was impossible for the Renaissance architect to conceive that the truth of the world could be reduced to its visual representation, a two-dimensionall diaphanous section of the pyramid of vision' (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1992, n.p.)

In fact, the perpectivist representation of architecture was more often found in the fifteenth century paintings, which sought to represent the environment more accurately. In spite of the painters making use of perspective (Figure 2), there was no geometric systematization. Leon Battista Alberti introduced, in his treatise Della Pictura, perspective as the basis for artistic drawing. The perspectivist method began to be delimited, reducing the binocular vision to a single viewpoint, which by analogy would be the apex of the cone of vision. A plane intercepted the cone and, as a result, there was a cone projection on a plane. However, there was still no systematic consideration of depth, as illustrated by Albrecth Dürer depicting the method described by Alberti (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Section of the fresco “The Trinity, the Virgin, St. John and donors,” Masaccio, Santa Maria Novella, Florence, painted around 1427. Source: personal archive.

Figure 3. Illustration by Albrecht Dürer depicting the cone projection method described by in Della Pictura. Source: Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1992.

Only in the 16th century did treatises on perspective begin to systematize the empirical method. Vignola established the distance point method by introducing a second observer in the horizon line at the same distance from the focal point, enabling the representation of depth (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1997). Dürer made use of perspectivist equipments that entailed a rigorous method for representing objects; Desargues established the point at infinity as the meeting of two parallel lines, unlike his ancestors, who believed that the vertex of the cone of vision was the convergence point of two parallel lines. This made possible to systematize the perspectivist method as a geometric system analogous to that of competing lines, thus establishing his theory, the basis for descriptive geometry developed in the late eighteenth century by Gaspar Monge. So was the perspectivist representation systematized, gradually establishing the possibility of using geometry, two-dimensionality, and orthogonal projections in architecture conception.

For a long time, perhaps until modernism, architectural representation was not taken to its limit; it has not taken full advantage of its potential:

'Renaissance drawings are not simply the same as modern drawings in their relationship to the built place. Plans and elevations were not yet systematically coordinated within the framework of descriptive geometry. These drawings were not instrumental and remained much more autonomous from the building than those that result from typical contemporary practise' (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1992, n.p.).

The Modern Movement, which promoted objectivity and rationalization, maximized the use of architectural representation by rationalizing spaces, designing optimal solutions for architectural possibilities, often neglecting construction knowledge. As pointed by Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier (1997, pp.220-221), the separation between design and construction is enshrined in the 18th century, its emblematic architect being Jean-Laurent Legeay (1710-1786), who “advocated the virtuosity of an idea over its buildable potential” (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1997, p.220). The tradition beginning at that point in time was that of predominance of the whole image of the building for its visualization, made possible by perspective. "It suggested implicitly that knowledge of construction was not the responsibility of the architect" (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1997, p.221). Modernism, in a way, crowned the production of architecture via representation and perpetuated this process of separation between design and construction that had already been incorporated into architectural practice.

The greatest contribution of the perspectivist paradigm to architecture was the establishment of representation, which completely altered its process of production. Representation enabled prediction in architecture by allowing the reduction of architectural objects to the two-dimensionality of the medium used to depict them. Akin to perspective, other ways to represent the object arose – e.g., photography, invented in 1839, and video, invented more recently – based on the same principle of a single viewpoint within the same paradigm. "When an artist employs geometrical perspective he does not draw what he sees - he represents his retinal image" (Gregory, 1990, p.174). The image formed in the retina is the one ultimately interpreted by the brain. The retina is a two-dimensional medium through which the apprehended image is represented, and the brain interprets the images provided by both retinas, blending them into a sole new dimension. Perspectivist representation promotes the loss of the dimensional depth that exists in images of the world, as we perceive them.

Pérez-Gómez (1994) argued that depth was the first dimension before the prevalence of the perspectivist paradigm. Later the other two dimensions – length and width – made depth become merely one among the three dimensions. Reducing the importance of depth affected the space/time relation by causing the image – the image we see, the way we perceive the world – to lose value. Both photography and video, considered to be equivalent to perspectivist representation2, as well as perspective itself, are not enough to experience architecture, since they ignore depth; they just represent it, thereby contributing to the loss of space/time relationship.

When we stand before perspectivist representations, we are not the ones who see the world, but the eyes of others. The image that reaches us is the image from another person’s eyes. We no longer have a reference point of the moment as a possibility of spatial and temporal apprehension; we cannot even speak of duration as lived space and time. What we have is an image, an absolute image, cloistered in a window out of its space-time context. This window no longer opens to the world; it just represents a moment of the world to which it has oppened. An engraving by Dürer, “The painter studying draft laws through wires and a frame” (Gombrich, 1988, p.276) (Figure 4), shows the simplification imposed on the object by perspective. All of the object’s depth lines are reduced to a planned scheme of points in a framed window.

Figure 4. The painter studying draft laws through wires and a frame, Dürer, 1525, woodcut. Source: Dürer, 1532.

Perspective has been viewed as the "possibility of accurately representing a 3 dimensional environment into a 2 dimensional plan" (Cabral Filho, 1996, p.26). By observing Dürer’s engraving, one can raise doubts about this purported accuracy. The picture illustrates several perceptual concessions that are made to adjust the scene to its representation. The observer is reduced to a single eye, his position is fixed, and the object is static. Perspectivist accuracy is the precision of science, of mathematics, which transforms reality into models that can be analyzed. Thus, it is possible to scientifically envisage an achievable accuracy of perspective and descriptive geometry, as they make possible to assess the represented object and the method limitations are known to scientists. Nonetheless, in the same way that mathematical models are not grasped by those who do not know their inherent method, perspectivist or geometric representation is not understood by those who do not know the perspectivist method. Hence, the accuracy of perspective is only valid in light of one’s capability to imagine hypothetical depth, which is represented by lengths and distances.

The process of representation boils down to reducing the three-dimensional object to a two-dimensional medium that allows its re-presentation. In the case of representation of architecture, it is not just about presenting a three-dimensional object by means of a two-dimensional medium. The gap between architecture and its two-dimensional representation is not just of one dimension. We cannot take architecture as a three-dimensional object; we can be certain of at least two more dimensions – time and behavior – and, therefore, perspectivist representation is three dimensions behind architecture.

Depth is the first dimension lost in perspectivist representation. The way we perceive the world, stereoscopically, is reduced to two dimensions: length and width. The second lost dimension is time. Like writing, perspective is the search to register a discourse, remaining as a fragment of the event (occurrence) registered outside of time. Representation is an absolute image that can be read at any time and does not carry the object temporality. It requires some time to be read, in spite of not having any temporal relationship with the discourse. The third lost dimension is the behavior that allows interaction. Perspective, as inscription, is no longer an event, and the significance of architecture is not revealed in the act of inhabiting (enjoyment), but is restricted to the possibility of interpreting the fragment – an absolute image – that has been registered. There is no interaction; space and time are not experienced.

Aimed at overcoming the gap between the phenomenon and the representation of the phenomenon, we must understand the limitation of the perspectivist paradigm and envision the possibility of new alternatives.

'Even though most enlightened architects would recognize the limitations of tools of projection such as plans, sections, and elevations and predictive planning in relation to the actual meaning of their building work, no alternatives are seriously considered outside the domain of modern perspectivism, which has deeply conditioned our knowledge and perception' (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1992, n.p.)

Currently, in the context of informational culture, perspective is still the paradigm for architecture and its representation. In order to change the paradigm it is not enough to recover the lost dimensions or undertake any other kind of reformist strategy concerning the design process. In addition to the abovementioned problems, the perspectivist paradigm is fundamentally perverse as it promotes the capitalist mode of production of space, which implies the reproduction of the social relations of production, the separation between intellectual and manual labor, the resulting separation between design, construction, and use, and the transformation of space into commodity emphasizing its exchange value over its use value. It is necessary to change the mode of production because, as stated by Sergio Ferro, the design process based on representation via drawings exists and reaches us as ready-to-use, because according to the capitalist logic the construction site must be heteronomous. The architectural drawing becomes the obligatory form for the extraction of surplus value, thereby being an instrument of domination that aims at the production of goods (Ferro, 2006, p.108). The use of computers in architecture has not escaped the perspectivist paradigm; instead of promoting the use value with emphasis on lived space, computers contribute to enhance the production of goods with emphasis on conceived space.

On the use of new media in architecture and the false paradigm shift

It is necessary to understand how computers enter architecture – through its back door – in order to understand its almost unchallenged nexus with the perspectivist paradigm. According to Robert Bruegmann (1989, p.139), some architectural offices in the United States in the 1950s were already using computers to produce spreadsheets to assist in structural calculations. However, an interactive graphic interface to aid in design only appeared in the mid-1960s. In the early 1970s, computers seemed promising, but software limitations and the prospect of generating extremely rational products eventually gave rise to fierce critique of rationalization as proposed by modernism itself, which could be taken to extremes with the help of computers. Only in the late 1980s, with CAD (computer-aided design), did architecture finally welcome computers, which was consolidated in the 90s as an indispensable tool in the conventional design process. It is in the 1990s, with the almost worldwide computerization of architecture offices and schools, mainly in Europe and North America, that began to emerge several discussions about the introduction of a new paradigm in architecture. This paradigm would be informational, but in spite of being a real promise, it has not yet come true. Even with BIM (Building Information Modeling) and the potential of parametric design in the 21st century, the representational paradigm still prevails. The process of production of architecture is still heavily based on conceived space, with information technology still in service of representation and not directed toward lived space, for continuity of design and construction during use. Interestingly, the title of Bruegmann’s article – The pencil and the electronic sketchboard – written in the late 1980s already indicated the reproduction of the same representationalist process via electronic medium.

Three computer trends can be identified in the field of architecture: the use of traditional CAD programs (predominantly AUTOCAD for representation and REVIT for parameterization of elements represented and compatibilization of representations of so-called complementary projects); research and use of artificial intelligence to generate two- and three-dimensional drawings (Shape Grammar and Genetic Algorithms) and parameterization for digital manufacturing; and a third trend that might be called cybernetics, proactive, responsive or interactive architecture, in which the computer is part of the space and not just a design tool (facilitated by physical computing).

In most cases there prevails what Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier (1997) called perspectival paradigm, in which there is indeed no change in the conventional design process or product. Although its products are formally (or volumetrically) different from those of architectures of yesteryears, the purpose of the design process is still predominantly the production of other finished products, or as Lebbeus Woods (1996, p.279) put it, "a means of controlling human behaviour, and of maintaining this control into the future."

This conventional design process adopted by architects and taught in schools is, again, based on the perspectivist paradigm established in the Renaissance and presupposes the separation between subject and space (regarded as an object to be represented visually). According to Pérez-Gómez (1983), the representation that was introduced in the Renaissance was quite distinct from that which was used in medieval construction sites. Despite the fact that drawings were also used in the Middle Ages, they were never intended for representing the entire building; they only served as a means of communicating relevant information about the construction process to its diverse participants and of developing constructive solutions.

The basic difference between the two processes of production of space can be summarized by the distinction between a medieval process, based on what Henri Lefebvre (1991) called the lived space, and the Renaissance process, based on what the author called conceived space (or representation of space). This distinction leads to questioning the process of production initiated in the Renaissance. According to Sérgio Ferro (2006, p.194-195), Brunelleschi radically changed the relations of production in building sites by introducing a hierarchical practice, systematizing the separation between intellectual work (design via coded drawings) and manual work (construction via alienated labor), and exploiting work to extract surplus value. Alberti theorized that practice in his treatise. Obviously, from the Renaissance to the present day, design and construction processes have not remained unchanged, as shown by Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier (1997). However, the fundamentals remain the same: design process based on representation and separation between design, construction, and use.

This perspectivist paradigm also serves as the basis for the three computer trends in architecture outlined above. The structural logic of CAD programs reproduces the Renaissance perspectivist construction process (Figure 5). Although they do so much more quickly and make real-time manipulation possible (as can easily be done in SketchUp, for instance), there is no change in the logic of representation. The programs end up being more likely to aid representation (CAR – Computer Aided Representation) than design (CAD – Computer Aided Design). The project, generally speaking, remains the same, following the Renaissance logic of a fragmented process that aims at a finished product that will be fully built in the image and likeness of representation, to then be used.

Figure 5. Perspective of a chalice, Paolo Uccello, 1450-1465, as opposed to the modeling of the same chalice by means of Form.Z, 1997. Source: Lagear archive.

Although applications like REVIT allow parameterization and point to possibilities beyond the reproduction of the conventional design logic, their use is still restricted to aiding conventional representation. Even if possibilities of compatibility of complementary projects, for example, are maximized, nothing is changed as regards the Renaissance separation between design, construction, and use. In the case of parameterization for digital manufacturing, there is indeed a movement in the direction of strengthening the relationship between design and construction, particularly with respect to the properties of materials and formal possibilities.

Notwithstanding, the focus on formal representation maintains the separation between design, construction, and use, albeit differently from conventional processes. Most of the time parameterization is used to determine the potential of the material in a predetermined shape, but construction remains an industrialized process maybe more alienated than that of conventional construction. Those who work in construction (or assembly) have even fewer opportunities to intervene creatively in the process than those doing conventional work. While there is great potential for production of mobile, flexible, and adaptable structures through parameterization, this is little explored and its use remains estranged from the design and construction process. The logic of perspectivist structuration prevails.

Although applications that make use of artificial intelligence (Shape Grammar and Genetic Algorithms, among others) do not exactly work with perspectivist structuring because they use outside rules to generate form, they also lead to products that reproduce the same logic as that of the conventional process, since their main use has been precisely to reproduce architects’ process of formal composition and do it faster and provide both customers and architects with a greater range of options for decision-making. The separation between design, construction, and use is also indisputably present in these processes.

Interactive architecture has begun to propose some changes, albeit modest, in the conventional process. The main one being the use of computers – or new media such as physical computing – no longer to represent the project, but integrated in the space. This suggests a possible change in the design process, no longer directed to a final, prescriptive, and finished product, but to an open process that relies on user interaction for temporary completion. I call this open process “interface”, and argue that one of the goals of architecture and urbanism education should be to produce interfaces, not finished spaces. It is noteworthy that not all the current production of interactive architectures follows the logic of interface production. Conventional spaces are often produced (by means of conventional processes) and appended with apparatuses for interactive manipulation of images or sounds, or even sensors and actuators, which prescribe user actions.

Interfaces as possibilities beyond the representational paradigm

Although interface production may sound like an approach to replace the conventional process, we must be careful with such simplification. As they follow two distinct types of logic, they are not analogous. While the conventional design process is based on defining and solving problems, the architecture-as-interface approach aims at problematizing situations, leaving it open for users to give continuity. There is no clear separation between design, construction, and use, but the proposition of an interactive repertoire, which can either be a combination of physical parts, digital or hybrid interfaces, or a set of rules. The process of production of interfaces obviously uses drawings, but there is a shift in representation of its central, paradigmatic role and an emphasis on interactivity. However, representation and interactivity do not belong to the same category; it is, therefore, impossible to imagine one being replaced by the other.

Álvaro Siza Vieira summarized the role of architects as representing the interests of their customers by resorting to another representation, which is architecture (Bandeirinha, 2010, p.75). In this case representation of architecture would be in service of representation in architecture, explaining the contemporary design tradition. Returning to the initial discussion, it is possible to envision interfaces as the possibility for overcoming both representation processes. From the standpoint of representation in architecture, this leads to what Cedric Price (1996, p.483) calls “value-free architecture”, i.e., a type of architecture open enough for users to give meaning to it while completing it temporarily. On the other hand, from the standpoint of representation of architecture, this means letting go of the Renaissance emphasis, i.e., representation ceases to be an instrument of domination, division of labor, and separation between design, construction, and use. In both cases one cannot forget that representation is a valuable tool and should not be excluded from the production of architecture as interface, but it should be seen as a tool, not as a paradigm.

Currently physical computing (microcontrollers, sensors, actuators, etc.) points to the possibility of a cybernetic process of production of space, in which there is continuity and feedback between design, construction, and use. Unlike the representational role that Siza Vieira attributes to architects, it is possible to envision the architect as a producer of interfaces that provide users with opportunities to configure their spaces. The production of architecture as interface suggests a possible paradigm shift, from the perspectivist (or representational) paradigm to the informational paradigm, maximizing both the process of production based on lived space (not conceived space) and the actual development of information technology, which is, according to John Thackara (2000), currently more focused on its own development than on adding value to people’s lives.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank FINEP, CNPq, CAPES, and Fapemig for funding my past and present research, which informs this article.

References

Bandeirina, J. A., 2010. ’Verfremdung’ vs. ‘Mimicry’ The SAAL and some of its reflections in the current day”. In: D. Sardo (Ed.). Let’s talk about houses: between north and south. Lisbon: Athena/Babel, pp.59–79.

Barthes, R., 1991. The responsibility of forms: critical essays on music, art, and representation. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Los Angeles Times Blog. [ONLINE] Available at: <http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2010/04/tail-o-the-pup-the-landmark-la-hot-dog-stand-still-homeless-.html> [Accessed 02 September 2012].

Bruegmann, R., 1989. The pencil and the electronic sketchboard: architectural representation and the computer. In: E. Blau and E. Kaufman (Ed.). Architecture and its image. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp.139–55.

Cabral Filho, J. S., 1996. Formal games and interactive design. Ph.D. Sheffield University.

Dürer, A., 1532. Institutiones geometricae. Translated by Joachim Camerarius. Paris: Christian Wechel.

Ferro, S., 2006. Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

Gombrich, E. H., 1988. A História da arte. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara.

Gregory, R. L., 1990. Eye and brain: the psychology of seeing. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M., 1990. Being and time. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Hugo, V., 1993. The hunchback of Notre-Dame. Ware: Wordsworth. 1st ed. 1831.

Lefebvre, H., 1991. The production of space. London: Blackwell.

Peixoto, N. B., 1993. O olhar do estrangeiro. In: A. Novaes (Org.). O olhar. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Pérez-Gómez, A., 1994. The Space of architecture: meaning as presence and representation. In: S. Holl, J. Pallasma and A. Pérez-Gómez. Questions of perception: phenomenology of architecture. Architectural and Urbanism, July, 7. Special Issue.

Pérez-Gómez, A., 1983. Architecture and the crisis of modern science. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

Pérez-Gómez, A.; Pelletier, L., 1992. Architectural representation beyond perspectivism. Perspecta, 27.

Pérez-Gómez, A.; Pelletier, L., 1997. Architectural representation and the perspective hinge. Cambridge: MIT Pres.

Price, C., 1966. Life-conditioning. Architectural Design, October, 36, p.483.

THACKARA, J., 2000. The design challenge of pervasive computing. In: CHI (Computer Human Interaction Congress), 2000, The Hague. Keynote lecture. Available at: <http://www.doorsofperception.com/archives/2000/04/the_design_chal.php> [Accessed 02 September 2012].

V!RUS, 2012. Call for contributions. V!RUS, 7. Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus07/?sec=11&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed 03 September 2012].

Woods, L., 1996. The question of space. In: S. Aronowitz, et al. (Ed.).Technoscience and cyberculture. New York: Routledge, pp. 279–92.

2 Gregory (1990) argued that the camera reproduces the object as a geometric perspective, but we do not see the world as a perspectivist image, which makes perspectivist photographs and drawings seem wrong. Some cultures that have no knowledge of perspective, e.g., the Zulus, understand a perspective as a two-dimensional composition.

Perspective has been considered the paradigm of representation since the Renaissance, when its use began. Perspective emerges historically in the Renaissance, although several authors claim that Vitruvius had already presented the principles of perspective in his treatise on architecture (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier 1992, 1997)1. However, it is during the Renaissance that representation of architecture started to be debated, which also prompted discussion on "the difficulties involved in conceiving a work of architecture in terms of a two-dimensional set of projections" (Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier, 1992, n.p.). The process of production of architecture began to change with the possibility of representation and the creation of the architect profession to do so. Hence, architectural practice has begun to undergo change from the advent of the perspectivist paradigm during the Renaissance.