Autoria compartilhada: cinema, ocupação, cidade

Pedro Severien é jornalista, Mestre em Produção de Cinema e Televisão. É roteirista, produtor, editor e diretor de documentários, videoclipes, curtas e longas-metragens. Tem experiência na área de Comunicação, com ênfase na produção audiovisual e ativismo audiovisual.

Como citar esse texto: SEVERIEN, P. Autoria compartilhada: cinema, ocupação, cidade. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 17, 2018. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus17/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 28 DE AGOSTO DE 2018

Resumo

Parto da análise dos filmes [projetotorresgemeas] (2011) e Novo Apocalipse Recife (2015) para abordar formas participativas e colaborativas na autoria audiovisual. Estes trabalhos emergem de um engajamento de seus realizadores na luta pelo direito à cidade. Uma disposição social que, no Recife, se utiliza do cinema como ferramenta de produção de um conhecimento partilhado e compartilhado. Associando gestos da militância às formas de organização e expressões estético-narrativas dos filmes, mobilizo o conceito de multidão (HARDT; NEGRI, 2014) e direito à cidade (HARVEY, 2014) para construir uma reflexão entre cinema militante e comuns urbanos temporários, a exemplo das intervenções políticas do Movimento Ocupe Estelita e suas ações pela democratização do planejamento urbano.

Palavras-Chave: Ativismo audiovisual, Direito à cidade, Multidão, Cinema de ocupação

1Introdução

O cinema nasce como um dispositivo que agencia múltiplos contatos. Seja o contato de quem opera a câmera com quem está diante dela, seja o contato entre as pessoas que são reunidas para formar uma equipe de produção, ou mesmo o contato dos espectadores com as imagens projetadas numa tela situada, tradicionalmente, num espaço coletivizado. O espaço da sala de cinema produz, portanto, contato também entre os corpos reunidos para uma sessão. Como aparato tecnológico que permite a captura e a projeção de imagens que surge na virada industrial, rapidamente a forma de produzir esses contatos foi impactada pelo modelo industrial fordista1.

Esses contatos ou, se preferirmos, as relações entre os sujeitos implicados nas diferentes instâncias da cadeia produtiva do cinema, então, passam a ser mediados pela dinâmica da produtividade em escala e pela compartimentação das funções. A lógica da linha de produção é aplicada de forma que a equipe de cinema se organiza por uma hierarquia entre funções, dividida num organograma que determina os agentes criativos, técnicos e financeiros. Há uma variedade de possibilidades e permeabilidades entre essas instâncias desde os primórdios do cinema até os dias de hoje.

Mas, na perspectiva do cinema industrial, os detentores do capital e dos aparatos técnicos organizam-se como operadores de um sistema, disputando não só o controle sobre os modos de produção, mas também sobre os efeitos cognitivos e sociais de recepção dos filmes. Os espectadores passam a ser regulados por uma tentativa de predeterminação na qual não são vistos apenas como indivíduos ou sujeitos, mas, sim, consumidores. As narrativas dominantes visam, portanto, uma disseminação massiva desses produtos aos consumidores, ao mesmo tempo que ensejam produzi-los enquanto tais. Uma das linhas de força por trás dessa operação é evidente: fazer cinema para fazer dinheiro, buscando uma fórmula eficaz de produção para esse objetivo.

[...] a indústria trabalha dentro de paradigmas claros para que transformação da matéria em produto funcione de forma ideal. É necessário colocar os sujeitos em uma linha de montagem em que suas capacidades subjetivas e criativas sejam deixadas de lado — o que não significa dizer que na indústria não haja criatividade [...] É preciso que, no limite, entre projeto e produto não haja alteração e que tudo funcione em absoluta previsibilidade. Para a indústria, é necessária uma política de escassez, em que as cópias são reguladas; um novo produto significa mais matéria-prima e tempo de linha de montagem em operação; logo, custo (MIGLIORIN, 2011, p. 1).

Como apontam Shohat e Stam (2006), o início do cinema coincide com o auge do imperialismo. O cinema dominante expressou a voz dos vencedores da história e uma parte significativa dessa filmografia idealizava a empresa colonial como “missão civilizatória”. As imagens caminham junto, portanto, às intensas disputas coloniais dos países ricos por territórios em nações e regiões mais vulneráveis. Assim, “as representações programaticamente negativas das colônias ajudavam a racionalizar os custos humanos do empreendimento imperialista” (STAM, 2006, p. 34).

O cinema industrial ou dominante, demonstrava-se um eficaz operador das relações sociais, das imagens políticas do mundo moderno e dos novos costumes. No entanto, como linguagem, meio e suporte, o cinema esteve também no centro das disputas encampada por grupos sociais revolucionários, transgressores e libertários. Além de se contrapor aos discursos dominantes, esses grupos produziram arquivos das lutas para si e gerações futuras.

Essa contraposição estabelece uma das bases para a discussão de um aspecto específico dessa trajetória histórica e política: a autoria. Na virada para o século XXI, há o declínio da hegemonia industrial na economia. E consequentemente uma emergência do capitalismo imaterial, das operações financeiras, do capital especulativo e do mercado virtualizado da Internet.

Se no mundo contemporâneo o valor e os sujeitos não têm mais a indústria como paradigma, tal passagem, ou sobreposição, de uma forma de criação de valor a outra faz com que o cinema contemporâneo estabeleça fortes diálogos com essa configuração — que nem é tão nova assim, mas que não deixa de nos surpreender em seus desdobramentos, exigindo ainda que os agentes sociais recoloquem os problemas de fomento, produção e distribuição sob novas composições (MIGLIORIN, 2011, p. 1).

No cinema contemporâneo pós-industrial, não raro a divisão técnica do trabalho, que se separava em funções específicas, é abolida ou subvertida. A difusão online a partir de matrizes digitais adiciona mais uma camada de complexidade à disputa da distribuição: o controle corporativo das redes virtuais. Ao mesmo tempo, a virada pós-industrial abre possibilidades para reconfiguração tanto do cinema de autor2 como dos cinemas militantes e insurrecionais. A dimensão política da autoria atravessa a história do cinema, mas aqui esta trajetória será investigada na perspectiva de um acontecimento contemporâneo específico: o Movimento Ocupe Estelita e a luta pelo direito à cidade no Recife.

O cais José Estelita é uma área de mais de 110 mil metros quadrados, situada no centro histórico do Recife. O terreno fica nas bordas da bacia do Pina, ecossistema que impacta na reprodução de diversas espécies de vegetação, aves, peixes e crustáceos. Dezenas de pescadores urbanos sobrevivem dessa atividade na região. O cais é também um dos principais cartões postais da cidade. Em 2008, o terreno foi vendido num leilão irregular e arrematado pelo consórcio Novo Recife. Composto pelas empresas Moura Dubeaux, Queiroz Galvão, Ara e GL Empreendimentos, o consórcio propõe a construção de até treze torres, boa parte delas com mais de 40 andares, divididas entre estabelecimentos comerciais e moradia de alto padrão econômico.

Escrevo sobre o Ocupe Estelita enquanto pesquisador e realizador audiovisual, mas também como ativista engajado no movimento social. Participei da produção coletiva e colaborativa de uma série de curtas-metragens militantes, além de transmissões ao vivo de atos, produção de manifestos e ocupações temporárias, entre outras ações. Uma das características estratégicas dessa mobilização que luta pelo direito à cidade no Recife é justamente a articulação entre diferentes dimensões sociais, promovendo atividades culturais, assembleias políticas e disputa institucional.

Nesse texto, proponho um caminho reflexivo com os filmes produzidos nesse embate. Observo-os com o processo histórico e antropológico que os emana, como gestos, ações. Também caminho próximo, porque sou meio sujeito, meio objeto na acepção de Guattari (2012). Fui um, entre os tantos autores Novo Apocalipse Recife3 (2015), filme realizado pelo Movimento Ocupe Estelita e pela Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista, e que fará parte da análise deste texto. O outro filme a ser abordado é [projetotorresgemeas]4 (2011), uma realização coletiva, que nasce a partir de uma convocatória para produção de imagens e narrativas sobre as relações de poder na cidade. Ambos trabalhos voltam-se para a produção de cidade e coletivizam a autoria como estratégia de realização. O foco da reflexão que proponho é: como os modos de partilha da autoria podem produzir comunalidade e, com isso, colaborar na democratização do espaço urbano?

2Cine-multidão

Em abril de 2010, é publicada nas redes sociais por um grupo de ativistas, identificado apenas como [projetotorresgemeas], uma convocatória para reunir interessados em discutir as relações de poder no território urbano através da produção de um filme coletivo. A chamada evidencia um desejo de misturar olhares, quase como uma transposição para o campo audiovisual do conceito de cidade enquanto mecanismo misturador de gente, como atesta o trecho abaixo:

Qualquer pessoa — de Recife ou não — poderá contribuir com a obra produzindo material que dialogue com a discussão proposta, com total liberdade de abordagem. Não há restrição de formato do material (filme, vídeo, fotografia, ilustração, música, texto escrito, etc.) nem na tecnologia de captação ou gênero (ficção, documentário, videoarte, entrevistas, trechos soltos de vídeo, charge, tira, desenho, ensaio, poesia, canção, declamação etc.). Apesar do ponto de partida serem as Torres Gêmeas, o material poderá e deverá expandir-se para territórios e temas diversos, que de alguma forma dialoguem com a discussão inicial ([PROJETOTORRESGEMEAS], 2010, s.d.).

O [projetotorresgemeas] ganhou forma final em um curta-metragem de 20 minutos reunindo registros que ora utilizam-se de relatos subjetivos, irônicos ou poéticos, ora inscrevem-se no real para estabelecerem suas articulações narrativas com o tema. A narrativa geral desenha-se justamente como um encontro desses olhares, experimentações díspares na cidade. As imagens caminham juntas na tela, sendo o filme como uma amálgama de singularidades expressas nas imagens. Ao todo, participaram da ação 57 realizadores coautores, dos quais a maioria já tinha vínculo com a produção audiovisual. Mas uma parte significativa se somou à iniciativa a partir de outros campos, como a arquitetura e o urbanismo, a luta por moradia, a produção cultural e a universidade. Vejamos como essa mobilização se expressa na tela a partir de algumas cenas selecionadas para análise.

Uma boneca de plástico submersa numa piscina; a perspectiva da janela de um avião que sobrevoa a cidade voltando-se para a faixa d’água ocupada por espigões; as sombras das “Torres Gêmeas”5 projetadas nas águas esverdeadas do Rio Capibaribe enquanto o quadro é atravessado por uma lancha; ou uma mulher vestida com os trajes de uma simbólica justiça cega na qual as balanças carregam maquetes das torres residenciais.

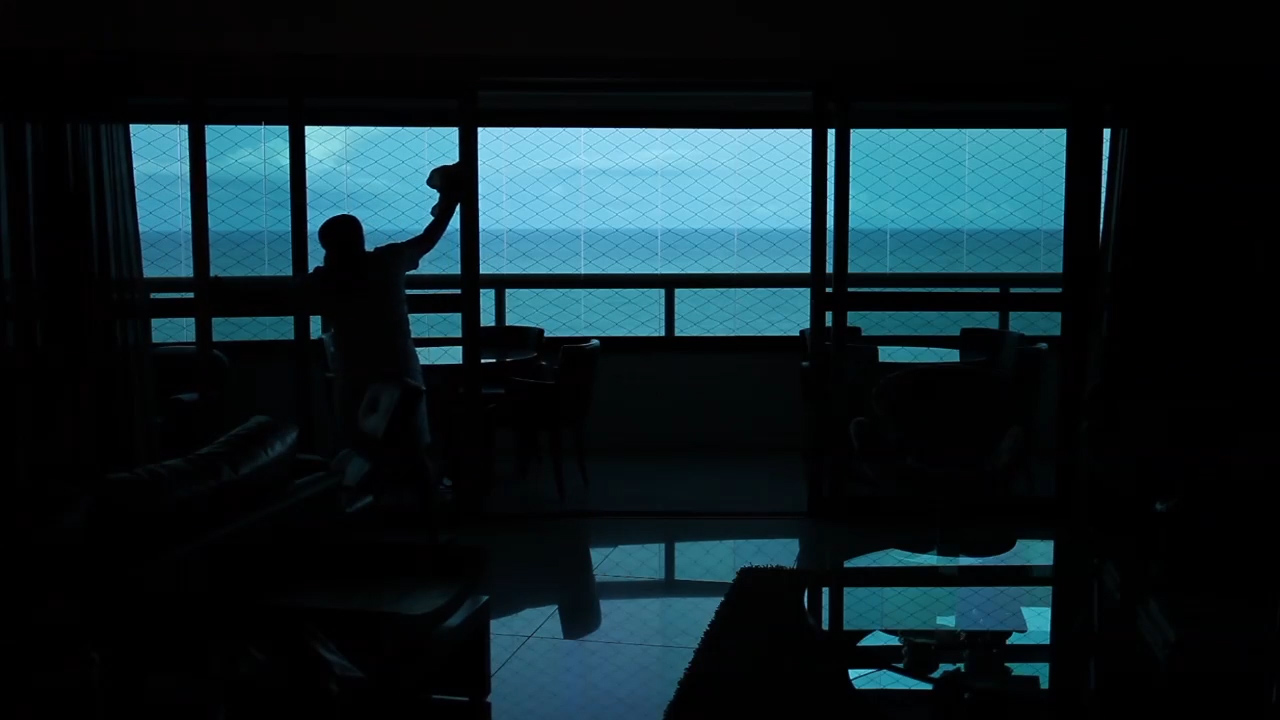

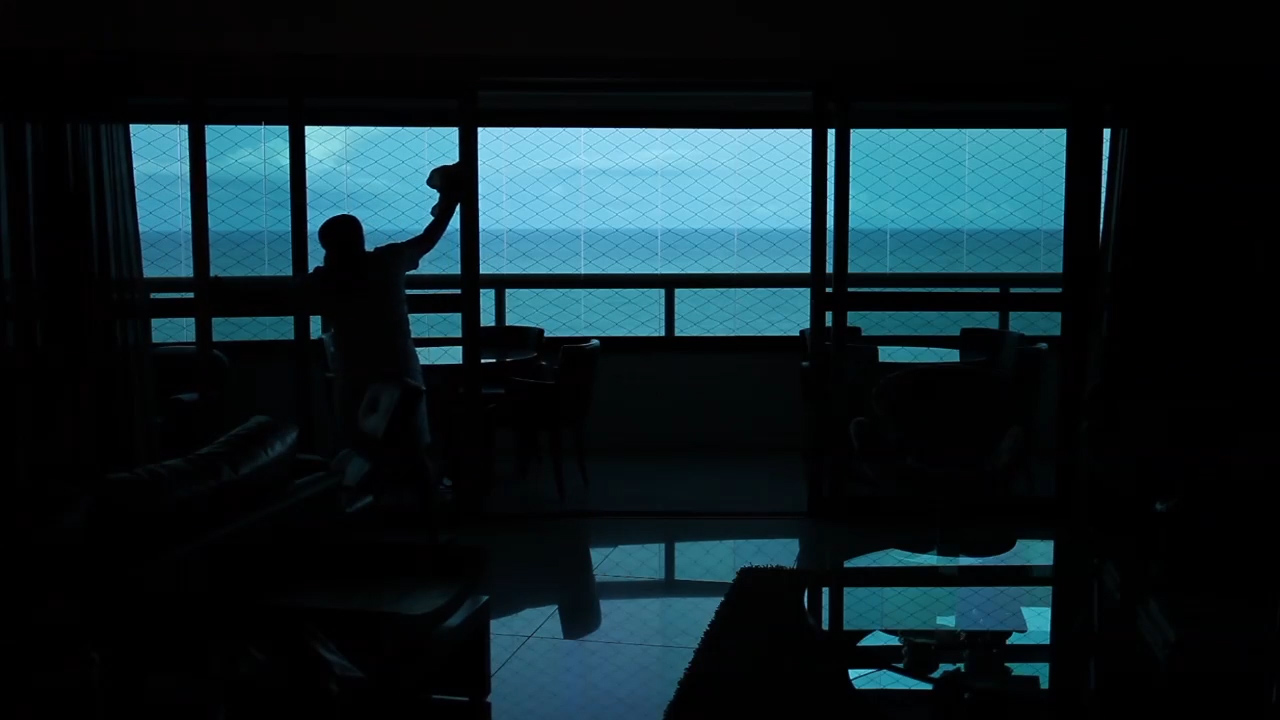

Uma crítica à cidade desigual está presente em sequências como a de uma empregada doméstica que aproveita por alguns instantes a brisa marítima e a vista do horizonte esverdeado na varanda de um dos apartamentos das “Torres Gêmeas” para, em seguida, continuar sua rotina de limpeza das janelas que emolduram essa perspectiva. Ao final do expediente, a trabalhadora deixa esse lugar de paz privativa, tão recorrentemente reafirmado na publicidade dos empreendimentos imobiliários do Recife, para adentrar o universo caótico e superpopulado por carros da rua, como demonstram as Figuras 1, 2 e 3.

Fig. 1: Fotograma de [projetotorresgemeas]. Fonte: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

Fig. 2: Fotograma de [projetotorresgemeas]. Fonte: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

Fig. 3: Fotograma de [projetotorresgemeas]. Fonte: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

Acionando o seu mecanismo de mistura, a montagem parece dispersar ao longo da duração do filme uma outra ação que se conecta tanto esteticamente quanto espacialmente à trajetória da trabalhadora doméstica. Refiro-me a um plano que mostra uma torre de papelão em escala humana que caminha pela faixa de pedestres e se coloca em frente aos carros como uma publicidade temporária durante os sinais vermelhos. O recurso de uso dos sinais de trânsito como ponto de sedução de consumidores é recorrente no mercado imobiliário do Recife. Durante os anos 2000, houve um boom de crescimento econômico do País, e do Estado de Pernambuco, que em alguns anos cresceu mais do que a média nacional. Nesse período, era comum encontrar jovens uniformizados nos sinais de trânsito a distribuir panfletos sobre os próximos empreendimentos. A Figura 4 permite a visualização desse procedimento de maneira encenada.

Fig. 4: Fotograma de [projetotorresgemeas]. Fonte: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

A relação entre os corpos é dividida, portanto, por aqueles que permanecem na rua, à espera dos sinais vermelhos, para transitar por entre os carros, acessando os potenciais consumidores que estão dentro dos automóveis. O contato se dá por uma brecha nas janelas, que podem se abrir ou não. A posse de um automóvel, neste caso, é um fator decisivo na busca do público-alvo de consumidores. Os pedestres que transitam nas calçadas não atendem ao mercado imobiliário; os possuidores de carros, sim.

Numa revelação imagética dessa dinâmica, o filme mostra, num contraplano da torre de papelão parada na faixa de pedestres, um jovem encolhido como suporte humano daquela superfície, como mostra a Figura 5. Mais uma vez o filme traz o debate imagético para os corpos e sua relação com a materialidade do espaço e seus regimes de visibilidade. A torre de papelão emoldura um corpo espremido. De um lado, os motoristas e passageiros dos carros, com suas janelas próprias para o mundo exterior, veem uma face da imagem — a superfície de consumo. No contracampo, no qual só as pessoas que atravessam a faixa de pedestres poderão ver, está o impacto num corpo — o resultado intencionalmente ocultado dessa dinâmica.

Fig. 5: Fotograma de [projetotorresgemeas]. Fonte: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

Em outra sequência, o filme entra num prédio público em ruínas, situado a poucos metros dos edifícios Píer Maurício de Nassau e Píer Duarte Coelho. Enquanto a câmera transita por esse espaço ocupado por famílias de sem-teto, incide sobre a banda sonora um jingle publicitário de um empreendimento imobiliário. Crianças correndo descalças nas escadarias, brinquedos espalhados pelo chão, a ocupação do espaço para moradia de diversas famílias sem-teto. Dialogicamente, imagem e som constroem uma projeção do futuro iminente. As pessoas que ocupam aquele prédio público não permanecerão ali por muito tempo, estão todas sendo sujeitas a um processo de expulsão por conta do círculo de riqueza projetado para “reformular” o centro da cidade.

Essa nova paisagem não prevê as pessoas que hoje ocupam o centro para moradia, mas, sim, aquelas que poderão desfrutá-la na perspectiva do consumo. Constrói-se assim uma respectiva visualidade estabelecida para a demarcação dos espaços e a organização dos sujeitos. A última cena do filme parece confirmar essa dinâmica. Dois corpos masculinos brancos entram em quadro, posicionando-se com a pélvis em primeiro plano. No recorte do quadro, as genitálias masculinas centralizadas, enquanto os homens começam a acariciar a si mesmos. Aos poucos, os órgãos sexuais assumem posição vertical. Quando atingem ereção total, o primeiro e o último plano do quadro são interpostos com maquetes da paisagem do entorno das “Torres Gêmeas”. A rima visual faz uma alusão à dimensão fálica dessa imagem da cidade associada a centralização de poder de uma sociedade ainda patriarcal. Uma das deixas parece ser: quais os sujeitos que terão garantidos protagonismos por esse “novo” espaço urbano em construção?

Novamente, a narrativa visual remete a uma distribuição das visibilidades na cidade neoliberal, que organiza uma divisão precisa entre os que veem de cima a linha do horizonte e dão as costas para a cidade histórica e o espaço público. Do plano das ruas, a perspectiva é marcada pela onipresença dos prédios. Subvertendo temporariamente essa imposição, como na cena da empregada doméstica observando o horizonte da varanda, o filme afirma que uma determinada visibilidade implica a invisibilidade de uma parte expressiva da população que tem, recorrentemente, negado o direito de se apresentar, de estar visível em suas singularidades.

A construção dos edifícios Píer Maurício de Nassau e Píer Duarte Coelho confrontam a legislação urbana para uma área histórica, e os prédios da construtora Moura Dubeux são erguidos no Cais de Santa Rita, nas proximidades do centro histórico, mesmo sob ordem judicial de demolição. O atual projeto de transformação do centro que está em curso tem as “Torres Gêmeas” como uma etapa apenas de uma ação bem mais ampla que ocorre segundo a lógica da gentrificação. Ou seja, essas “renovações” servem ao deslocamento de um contingente populacional de baixa renda, que está sendo retirado e afastado do centro, para o favorecimento de um outro grupo com poder aquisitivo mais elevado.

Lees, Slater e Wyly (2008) sugerem que a gentrificação contemporânea — baseada em grandes desigualdades de riqueza e poder — se assemelha a ondas anteriores de expansão colonial e mercantil que exploraram diferenças nacionais e continentais no desenvolvimento econômico. Foi exportada das metrópoles da América do Norte, Europa Ocidental, Austrália e alguns países asiáticos para novos territórios em antigas possessões coloniais em todo o mundo.

Esse processo privilegia a riqueza e a branquitude e reafirma a apropriação anglo branca do espaço urbano e da memória histórica [...] E universaliza os princípios neoliberais de governar as cidades que forçam os residentes pobres e vulneráveis a suportar a gentrificação como um processo de colonização por classes mais privilegiadas (LEES; SLATER; WYLY, 2008, p. 167,tradução nossa).

A cidade e o processo urbano que a produz são, portanto, importantes esferas de luta política, social e de classe, uma vez que, como sustenta Harvey (2014), a urbanização do capital está vinculada não só a sua capacidade de “dominar o processo urbano” na perspectiva de controle dos aparelhos de Estado. A urbanização no viés de consumo utiliza estrategicamente processos de subjetivação como forma de exercício de um poder também sobre estilos de vida da população, “[...] sua capacidade de trabalho, seus valores culturais e políticos, suas visões de mundo” (HARVEY, 2014, p. 133). De tal forma que a dimensão do visível ou de um direito dos sujeitos de apresentarem-se com suas singularidades, é centralizada pela lógica excludente do privatismo e do patriarcado. Esse processo de concentração e assimetria, está intimamente ligado a um outro direito igualmente vilipendiado: o direito à cidade.

O direito à cidade é [...] muito mais do que um direito de acesso individual ou grupal aos recursos que a cidade incorpora: é um direito de mudar e reinventar a cidade mais de acordo com nossos mais profundos desejos. Além disso, é um direito mais coletivo do que individual, uma vez que reinventar a cidade depende inevitavelmente do exercício de um poder coletivo sobre o processo de urbanização. A liberdade de fazer e refazer a nós mesmos e a nossas cidades [...] é um dos nossos direitos humanos mais preciosos, ainda que um dos mais menosprezados (HARVEY, 2014, p. 28).

O projeto Novo Recife é uma etapa subsequente desse plano de ocupação de uma extensa faixa d'água que vai do litoral sul, nas proximidades do Porto de Suape, no Cabo de Santo Agostinho, até a Vila Naval, em Olinda, como atesta o urbanista Cristiano Borba em depoimento para o curta-metragem Recife, cidade roubada (2014)6. O que os movimentos pelos direitos urbanos reivindicam é justamente a abertura desse planejamento para a participação social. Essa demanda por participação conflita diretamente com os interesses de grandes empresas que protagonizam o mercado imobiliário, em franca adesão a uma perspectiva de produção de uma cidade de consumo.

Confrontando processos de atomização da cidade neoliberal, o filme produz uma coletividade. Requer meses de trabalho coletivo, com reuniões presenciais periódicas e uma lista de e-mails para debates. O processo de realização exige organização, pactuação e também uma certa disposição para o dissenso, uma vez que a versão final só utiliza parte do material filmado. Nessa perspectiva, a colaboração e a participação não apontam para uma coletividade reduzida a uma unidade, mas justamente o contrário – uma coletividade que pressupõe a diferença e suas singularidades articuladas.

O que [projetotorresgemeas] faz com seu gesto é uma coletivização da tela entre diferentes sujeitos que se justapõem, e é nessa justaposição que o filme aponta para uma outra cidade possível. A crítica social, a ironia, o simbólico, tudo isso opera também em contato com os corpos mobilizados para a realização do filme. De maneira iniciática, o curta-metragem sugere procedimentos colaborativos que serão evocados durante disputas narrativas e midiáticas relacionadas à destinação do cais José Estelita. Com a ocupação do cais, que durou cerca de 50 dias em suas diferentes fases, há uma intensificação dos processos de cooperação para produção narrativa, não só no audiovisual, como no design, na fotografia, na escrita de manifestos e na realização de atividades públicas.

A organização dessa produção e a partilha do lugar da autoria surgem em uma variedade de arranjos. A maneira de comunalizar a realização está diretamente ligada a uma estratégia coletiva que vai se reelaborando ao longo da luta do Ocupe Estelita. Como veremos a seguir, a autoria compartilhada pode apontar para uma polifonia, como em [projetotorresgemeas], mas não só.

3Carnavalizando a imagem institucional

Se em [projetotorresgemeas] há uma mistura nas texturas dos diferentes registros imagéticos e sonoros, mas também nas diferentes abordagens narrativas imanentes aos diferentes sujeitos-autores, em Novo Apocalipse Recife há uma centralização do regime estético do filme. Enquanto no primeiro filme se fala de uma cidade múltipla, articulada pelas diferentes naturezas da imagem e das singularidades incluídas numa narrativa polifônica, no segundo há um ataque frontal e unificado. Elege-se um alvo: a relação do prefeito da cidade do Recife, Geraldo Julio, do PSB, eleito em 2012 para o seu primeiro mandato e reeleito em 2016, com as empreiteiras que compõem o Consórcio Novo Recife.

Em 2011, a saturação do projeto de verticalização da cidade começava a ganhar um contraponto através da mobilização social, mesmo que ainda dispersa e pontual, com grupos de articulação pelos direitos urbanos e as "Torres Gêmeas" como ponto de inflexão. Em 2014, a ocupação do Cais José Estelita7 tinha funcionado como um catalisador dos debates pela democratização do planejamento urbano. Como é ironicamente proferido pelo cineasta Kleber Mendonça Filho em depoimento para Recife, cidade roubada (2014)8, as "Torres Gêmeas" eram apenas um trailer do que viria a se apresentar como Novo Recife.

A vivência coletiva da ocupação, as tentativas de negociação com o executivo municipal e a violenta reintegração de posse no dia 17 de junho de 2014, tinham marcado os corpos e a memória do movimento. Não acabariam por aí as tentativas de pressão social e negociação com a prefeitura. No dia 30 de junho de 2014, foi organizada pelo Movimento Ocupe Estelita uma ocupação do piso térreo do prédio da Prefeitura da Cidade do Recife. Numa ação que obteve repercussão através das redes digitais e mobilizou toda a imprensa local, os ativistas montaram acampamento com uma pauta específica: que o projeto Novo Recife fosse cancelado.

O piso térreo foi ocupado logo no início da manhã, como apresentado na Figura 6. Imediatamente, o aparato municipal de segurança foi acionado, e em poucas horas o prédio foi fechado e o expediente encerrado. Ao longo dos dois dias de permanência da ocupação, houve uma série de reuniões entre ocupantes e representantes da prefeitura. No entanto, ao final, a saída dos ocupantes foi colocada como uma imposição e a prefeitura conseguiu no Judiciário uma ordem de reintegração de posse. O documento estabelecia a saída até as 14h do dia 1º de julho, com a condicionante de que, caso os ocupantes não deixassem o prédio, entraria em ação o Batalhão de Choque da Polícia Militar9.

Fig. 6: Fotograma de Ocupar, resistir, avançar, que mostra a ocupação do piso térreo do prédio da Prefeitura da Cidade do Recife. Fonte: MOVIMENTO Ocupe Estelita, 2015.

O desfecho da ocupação da prefeitura gera frustração. De uma forma geral, a reverberação midiática nacional e até internacional da ocupação do cais tinha surtido um efeito empático relevante na opinião pública, trazendo o apoio de uma diversidade de atores sociais, mas do ponto de vista prático o projeto Novo Recife continuava seu rumo no âmbito do executivo municipal. Por isso, a tentativa de uma intervenção direta na prefeitura. Mas a mobilização dos corpos estava passando por um hiato pós-ocupação do cais, e a ocupação da prefeitura tinha exigido um grande esforço político de articulação sem resultados práticos. Além desses fatores, o consórcio Novo Recife contra-atacava com a exibição de peças publicitárias nos principais canais de televisão e uma pesquisa de opinião que afirmava que 80% da população do Recife era a favor do empreendimento10.

Diante desse contexto, surge o argumento para Novo Apocalipse Recife. O gesto do filme coaduna com o gesto do coletivo performático Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista11. Utilizando-se de um tom carnavalesco e provocativo, a narrativa se assemelha a uma peça publicitária paródica na qual o prefeito do Recife, Geraldo Julio — reencarnado com uma máscara de papel —, faz uma ode ao projeto Novo Recife. Mirando nos afetos e no riso, o filme faz uma paródia da música de Reginaldo Rossi intitulada Recife, minha cidade.

Em uma série de situações lúdicas, o personagem-prefeito age em louvação às “qualidades” do projeto Novo Recife, seja dançando de sunga com a insígnia da bandeira de Pernambuco em frente aos espigões espelhados da beira-mar do bairro de Boa Viagem (Figura 7) ou sendo conduzido como um cachorrinho por uma das torres-fantasia da Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista (Figura 8).

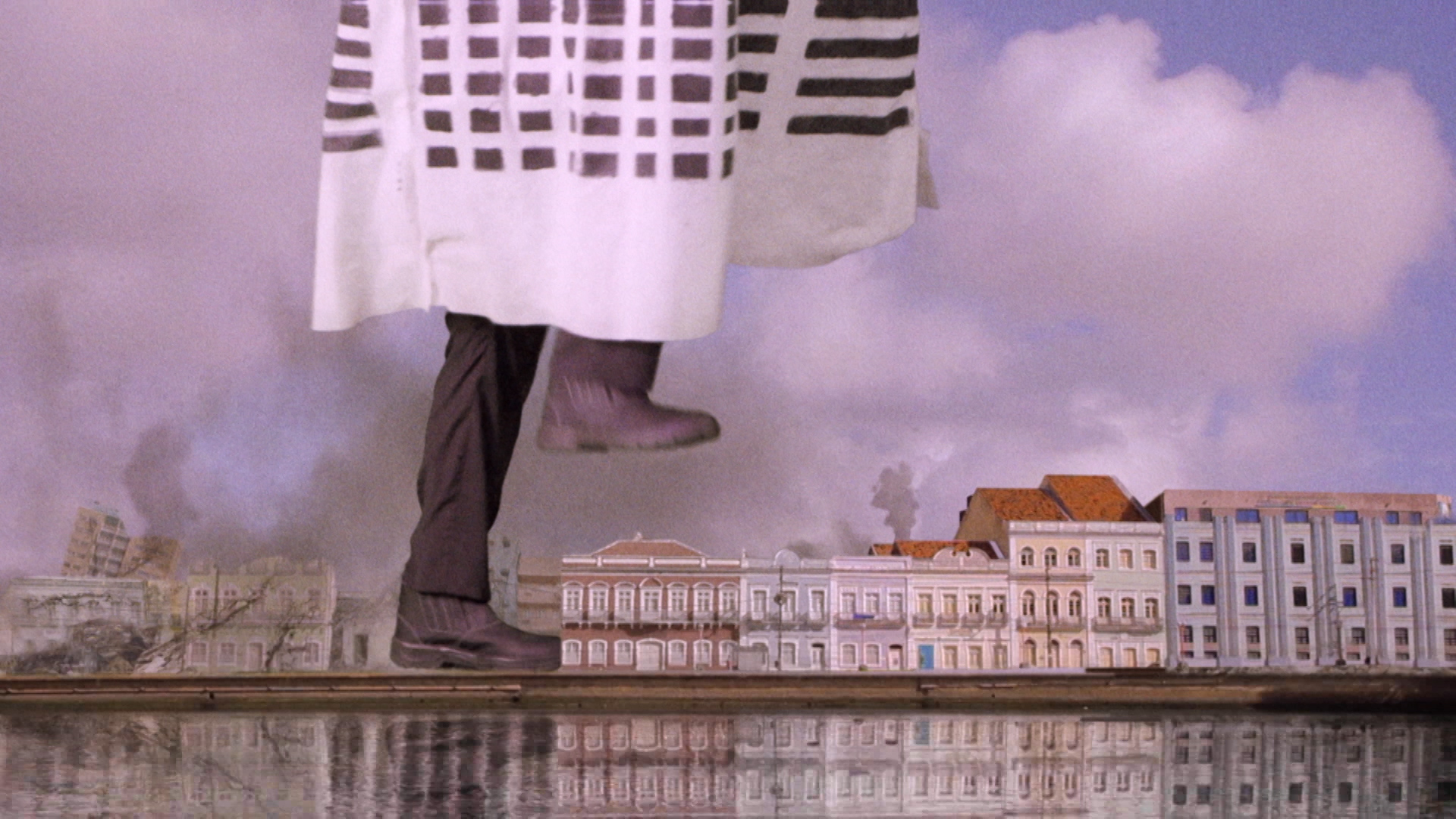

Em um momento de clímax do filme, as torres-personagens crescem vertiginosamente, como Godzillas, esmagam trechos históricos e vulneráveis da cidade (Figuras 9 e 10) e catapultam o prefeito pelos ares como um super-herói (Figura 11).

O gesto de produzir a imagem de um “novo” prefeito para uma “nova” cidade propõe desmascarar uma face nem sempre visível das relações de poder: a íntima associação de interesses privados na agenda de representantes do poder público. Na Figura 12, o novo-prefeito comemora o exitoso negócio com personagens que trazem nas cabeças sacos de papelão estampados com as marcas das empresas que compõem o consórcio Novo Recife.

No caso de Novo Apocalipse Recife, a assimetria perante o poder institucional, demonstrada com o favorecimento ao capital imobiliário e o desprezo à participação popular, é averiguada ao longo de toda uma série de tentativas de negociação no âmbito institucional. Sendo assim, não se deve olhar para o gesto do filme fora do histórico recente dos novíssimos movimentos sociais de produção de uma crítica ao sistema representativo, ou à sua recorrente captura pelo capital. Olhando especificamente para o contexto local, um dos projetos inconclusos dos ativistas e realizadores de [projetotorresgemeas] é outra produção de convocatória coletiva intitulada Eleições: Crise de Representação12.

Novo Apocalipse Recife expressa a insistência do Movimento Ocupe Estelita na denúncia dos desmandos relativos ao cais. Vale pontuar que essa insistência foi contestada tanto pelo executivo municipal quanto por grupos organizados da sociedade que formulavam uma outra narrativa: a de que o Novo Recife representaria a modernização da cidade. O gesto de carnavalização da imagem do prefeito mantém-se associado ao gesto do movimento social para uma outra produção discursiva: esse suposto progresso coletivo associado a uma “modernização” tenta acobertar o fato de que projetos como o Novo Recife favorecem a poucos13.

O cais José Estelita, enquanto um espaço de natureza pública, tem potencial para agregar diferentes sujeitos que podem, à sua maneira, reconfigurar o espaço, transformando-o em um lugar de comunalidade. Essa potência está na matriz do direito à cidade, enquanto dispositivo social essencialmente coletivo e que oferece uma perspectiva partilhada na autoria dos processos de produção de cidade.

À sua maneira, a diluição da autoria audiovisual em um plural que roteiriza e encena uma peça que tem coesão estética não funciona para o apagamento das singularidades das pessoas envolvidas, mas para expressão de seus afetos agenciados. O germe do filme é igualmente materializado de forma descentralizada, seja através das intervenções performáticas da Troça Empatando Tua Vista, seja na série de encontros que ocorreram para roteirização e debates para tomada de decisões estratégicas que ocorreram em assembleias e eventos organizados pelo movimento Ocupe Estelita.

Talvez aqui valha a pena voltar o olhar para um breve histórico da Troça Empatando Tua Vista e sua busca pelo constrangimento mais direto à política institucional. Durante o Carnaval, a troça realiza aparições durante o tradicional café da manhã no camarote do bloco Galo da Madrugada, local de encontro de políticos da cidade. Essas ações do Empatando têm recebido recorrentes reações restritivas do poder público.

No carnaval de 2016, funcionários da Diretoria de Controle Urbano impediram a saída dos manifestantes com as fantasias de prédio. E, no ano seguinte, policiais militares apreenderam as fantasias. Em 2018, os manifestantes conseguiram um habeas corpus cautelar para garantir a saída com as fantasias. O filme enquanto gesto crítico coletivo desdobra essa performatividade perante o poder hierárquico institucionalizado. Com isso, não desejo forçar uma positividade do gesto do filme, ou mesmo uma pretensa eficácia. Há uma ambivalência nos processos de carnavalização, seja no plano discursivo, seja no performativo. Stam (2006) irá colocar também as diferentes linhas de força que estão em ação a depender de quem carnavaliza quem.

Historicamente, os carnavais sempre foram eventos politicamente ambíguos; às vezes constituíam rebeliões simbólicas dos excluídos, outras vezes encorajavam a transformação festiva dos fracos em bodes expiatórios dos ricos (ou dos menos fracos). O carnaval e as práticas carnavalescas não são essencialmente progressivos ou regressivos: tudo depende de quem está carnavalizando quem, em qual situação histórica, com que propósitos e de que maneira. O carnaval forma uma configuração mutável de práticas simbólicas, um diálogo complexo entre manipulação ideológica e desejo utópico cuja a valência política muda a cada novo contexto. O poder oficial às vezes utiliza o carnaval para carnavalizar energias que poderiam de outro modo encorajar revoltas populares, assim como o carnaval também pode provocar inquietação nas elites e, por isso, ser objeto de repressão oficial (SHOHAT; STAM, 2006, p. 423).

Na fase final de montagem, o movimento Ocupe Estelita decide ocupar a calçada em frente ao prédio onde mora o prefeito. A ocupação permitiu inclusive que uma cena dessa intervenção fosse incluída no filme, estreitando os laços entre a narrativa carnavalizada e a ação presencial do coletivo.

O que esses procedimentos da produção narrativa a uma performatividade do gesto de ocupação indicam, a meu ver, é uma produtiva imbricação entre essas dimensões. O cinema militante que coletiviza a autoria permanece aberto à experimentação estética e formal, sem eximir-se da presença que ativa uma força da ação direta. Assim, a produção política e conceitual da ocupação opera como força vital da produção audiovisual e vice-versa. Ao mesmo tempo, esses vetores friccionam o processo institucional de planejamento urbano, pois reconfiguram uma imagem do poder dominante e consequentemente oferecem uma outra imagem da cidade.

4A imagem presente

Deleuze (1985) afirma que o cinema político moderno difere do cinema político clássico não por expressar-se de forma emancipatória “pela presença do povo”, mas justamente pelo contrário, por “[...] mostrar como o povo é o que está faltando, o que não está presente” (DELEUZE, 1985, p. 257). Essa análise autoral serve para produzir uma conclusão mais geral, tanto no cinema americano quanto no cinema soviético, nas suas formas clássicas: “[...] o povo está dado em sua presença, real antes de ser atual, ideal sem ser abstrato” (DELEUZE, 1985, p. 258) e a diferença essencial de uma abordagem clássica para a sua face moderna é que “[...] o povo já não existe, ou ainda não existe… o povo está faltando” (DELEUZE, 1985, p. 258-259).

Esse povo ainda falta? Ou faltava? Ou, talvez, apenas falte de outra forma? Para Hardt e Negri (2014), uma mudança ontológica ocorreu no mundo contemporâneo, e por isso propõem um deslocamento do conceito de povo, introduzindo uma outra abordagem conceitual, a multidão. A principal crítica dos autores ao conceito de povo é que o termo carrega uma unificação. “O povo é uno. A população, naturalmente, é composta de numerosos indivíduos e classes diferentes, mas o povo sintetiza ou reduz essas diferenças sociais a uma identidade” (HARDT; NEGRI, 2014, p. 139).

A multidão, em contraste, não poderia ser unificada, mantendo-se plural e múltipla. Os autores argumentam que, segundo a tradição dominante da filosofia política, “[...] o povo pode governar como poder soberano; e a multidão, não” (HARDT; NEGRI, 2014, p. 139). O que na perspectiva deles é uma falsa proposição. A multidão concebida por Hardt e Negri é composta de um conjunto de singularidades, na perspectiva de um sujeito social “[...] cuja diferença não pode ser reduzida à uniformidade, uma diferença que se mantém diferente. [...] As singularidades plurais da multidão contrastam, assim, com a unidade indiferenciada do povo” (HARDT; NEGRI, 2014, p. 139).

É importante destacar que há uma disputa entre conceitos quanto à concepção de sujeitos políticos coletivos contemporâneos tanto por uma diferente leitura das realidades sociais quanto por um exercício de reflexão filosófica que abre caminhos distintos através de diferentes genealogias teóricas. Por exemplo, o conceito de multidão como desenhado por Hardt e Negri tem sido recorrentemente questionado tanto por pesquisadores quanto por ativistas que apontam uma certa idealização de sua natureza revolucionária.

Dito isso, utilizo o conceito de multidão porque oferece um produtivo espectro de possibilidades para operacionalizar uma leitura da autoria nesse cinema que se faz na dinâmica dos movimentos sociais urbanos contemporâneos no Recife. Com isso, não quero excluir outros conceitos, como o de povo, em suas diversas acepções, para me aproximar de sujeitos políticos coletivos. A noção de povo mobilizada, por exemplo, por Butler (2015) indica potências ligadas a uma performatividade coletiva.

Então, peço que o leitor possa usar o conceito de multidão para os fins da análise dos filmes, neste caso específico [projetotorresgemeas] e Novo Apocalipse Recife, e não para um debate mais geral sobre qual mecanismo conceitual poderá abarcar de forma mais precisa as forças políticas de emancipação global. Em síntese, Hardt e Negri nos dizem que a multidão se trata "[...] de um ator ativo da auto-organização” (2004, p. 17).

Parto dessa perspectiva, para uma reflexão política dos gestos, como apontada pelo Comitê Invisível:

Quando se diz que “o povo” está na rua, não se trata de um povo que existia previamente, pelo contrário, trata-se do povo que previamente faltava. Não é “o povo” que produz o levante, é o levante que produz seu povo, suscitando a experiência e a inteligência comuns, o tecido humano e a linguagem da vida real, que haviam desaparecido (COMITÊ INVISÍVEL, 2016, p. 51).

É o levante que produz seu povo. Nessa perspectiva, sugiro também que não são os autores que produzem os filmes num cinema de ocupação, mas os filmes é que produzem os autores. Nesse viés, o processo de produção não se volta apenas para um suposto exterior numa disputa narrativa ou discursiva, mas para os gestos dos grupos que se mobilizam nessas ações audiovisuais. As relações que se estabelecem com a organização e a realização são tão importantes quanto o impacto do produto final. Partindo dessa reflexividade, reconheço práticas das ocupações urbanas como gestos produtores de comunalidade, que atravessam o plano comunicacional, transformando os modos de produção, sem fórmulas prontas. Ao lidarem com suas próprias demandas para acontecer, os filmes produzem coletividades.

Com isso, não deixo de considerar a dimensão simbólica articulada nesse processo, como foi reafirmado o tempo todo neste texto. Disputar politicamente a produção de cidade é também disputar uma outra imagem de cidade. Se o direito à cidade em sua essência partilhada projeta esse movimento coletivo, o cinema militante realizado em associação com o movimento social oferece uma ferramenta não só de disputa narrativa-midiática, mas uma mediação. Após esse breve trajeto entre os processos de produção e uma análise estético-formal dos filmes aqui abordados, gostaria de sustentar que um cinema de ocupação, em seus gestos, afirma singularidades e preserva diferenças, que servem para ativar a participação coletiva e uma potência de transformação e democratização da cidade.

Referências

[PROJETOTORRESGEMEAS]. Projeto. 2011. [online] Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/projeto/>. Acesso em: 29 out. 2018.

BUTLER, J. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge/Londres: Harvard University Press, 2015.

COMITÊ INVISÍVEL. Aos nossos amigos: crise e insurreição. São Paulo: N-1, 2016.

COMOLLI, J.-L. Ver e poder: a inocência perdida: cinema, televisão, ficção, documentário. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2008.

DELEUZE, G. A Imagem-tempo. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1985.

DIREITOS URBANOS. #OcupeEstelita +1. 2013. [online] Disponível em: <https://www.facebook.com/events/133583003493544/>. Acesso em: 1 mar. 2018.

GUATTARI, F. Caosmose. 2a. ed. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2012.

HARDT, M.; NEGRI, A. Multidão: guerra e democracia na era do Império. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2014.

HARVEY, D. Cidades rebeldes: do direito à cidade à revolução urbana. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2014.

LEES, L.; SLATER, T.; WYLY, E. Gentrification. Nova York: Routledge, 2008.

MIGLIORIN, Cesar. Por um cinema pós-industrial. Revista Cinética, 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.revistacinetica.com.br/cinemaposindustrial.htm>. Acesso em: 1 mar. 2018.

MOVIMENTO Ocupe Estelita. Ocupar Resistir Avançar. Realização: Ernesto de Carvalho, Luis Henrique Leal, Marcelo Pedroso, Pedro Severien. Recife: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Youtube (6 min 31 seg), son., color. Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KX6rirSw7c>. Acesso em: 29 out. 2018.

SHOHAT, E.; STAM, R.Crítica à imagem eurocêntrica. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006.

STAM, R. Introdução à teoria do cinema. Campinas: Papirus, 2006.

Conteúdo composto com o editor HTML online. Compre um código de licença para parar de adicionar anúncios semelhantes aos documentos editados.

1 Fordismo é um termo que se refere ao modelo de produção em massa de um produto, ou seja, ao sistema das linhas de produção.

2 O termo cinema de autor advém, principalmente, das discussões produzidas a partir do feixe de ideias denominado teoria do autor ou política dos autores, que emergiu durante as décadas de 50 e 60 na Europa e foram disseminadas para todo o mundo.

3 Realizado pelo Movimento Ocupe Estelita. Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk>.

4 Realizado por Allan Christian, Ana Lira, André Antônio, André George Medeiros, Auxiliadora Martins, Caio Zatti, Camilo Soares, Chico Lacerda, Chico Mulatinho, Cristina Gouvêa, Diana Gebrim, Eduarda Ribeiro, Eli Maria, Felipe Araújo, Felipe Peres Calheiros, Fernando Chiappetta, Geraldo Filho, Grilo, Guga S. Rocha, Guma Farias, Iomana Rocha, Isabela Stampanoni, João Maria, João Vigo, Jonathas de Andrade, Larissa Brainer, Leo Falcão, Leo Leite, Leonardo Lacca, Lúcia Veras, Luciana Rabello, Luis Fernando Moura, Luís Henrique Leal, Luiz Joaquim, Marcelle Lima, Marcelo Lordello, Marcelo Pedroso, Mariana Porto, Matheus Veras Batista, Mayra Meira, Michelle Rodrigues, Milene Migliano, Nara Normande, Nara Oliveira, Nicolau Domingues, Paulo Sano, Pedro Ernesto Barreira, Priscilla Andrade, Profiterolis, Rafael Cabral, Rafael Travassos, Rodrigo Almeida, Tamires Cruz, Tião, Tomaz Alves Souza, Ubirajara Machado e Wilson Freire. Disponível em: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/>.

5 O apelido dado aos Edifícios Píer Maurício de Nassau e Píer Duarte Coelho faz referência às torres do World Trade Center, em Nova York, destruídas pelo ataque terrorista de 11 de setembro de 2001.

6 Recife, cidade roubada é uma peça que deseja disputar a narrativa sobre a produção de cidade, do qual sou também coautor, realizada em associação com o Movimento Ocupe Estelita. É recorrente no Recife contemporâneo essa modalidade de produção que ocorre na urgência das disputas, produzida de forma autônoma, coletiva e colaborativa, e que tem a questão urbana como tema transversal. A partir de uma convocatória do Ocupe Estelita, em 2015, para a produção de uma antologia em DVD, foram mapeadas mais de 80 produções realizadas nessa perspectiva entre o início dos anos 2000 até os dias de hoje. Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJY1XE2S9Pk>.

7 Na noite de 21 de maio de 2014, quando o consórcio Novo Recife iniciou a demolição dos antigos armazéns de açúcar situados no cais, um grupo de ativistas ocupou o local, impedindo que as construções fossem colocadas abaixo. Ao se deparar com a ação das máquinas, um dos ativistas do grupo Direitos Urbanos postou no Facebook um chamado. Em poucos minutos, outros ativistas chegaram ao local e entraram no terreno. No dia seguinte, as informações sobre a ocupação já haviam corrido as redes digitais e mais pessoas chegaram até o terreno do cais. Rapidamente, uma força-tarefa para organização de doações e também de amparo jurídico foi montada a partir tanto do circuito de cooperação construído ao longo dos anos quanto por movimentos sociais parceiros e novos ativistas que se uniam à ocupação para a sua construção e manutenção. Instaura-se uma nova etapa de articulação política, o terreno do Cais José Estelita passa a funcionar temporariamente como ponto de convergência das lutas urbanas no Recife. A ocupação durou cerca de 50 dias contando suas diferentes etapas – primeiro na área interna do cais e depois de uma violenta reintegração de posse os ocupantes estabeleceram acampamento debaixo do viaduto Capitão Temudo, ao lado do terreno.

8 Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJY1XE2S9Pk>.

9 Um resumo desse processo pode ser visto no filme Ocupar, Resistir, Avançar: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KX6rirSw7c>.

10 No dia 04 de julho, recebi uma ligação do Ipespe, instituto contratado pelo projeto Novo Recife para uma pesquisa de opinião. Este vídeo mostra a entrevista na íntegra, revelando a forma tendenciosa com a qual a pesquisa era realizada. O material foi usado em uma ação do Ministério Público Estadual contra o Ipespe. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35vhQheS1pA>.

11 Descrição da Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista contida em sua página no Facebook: “A Troça Carnavalesca Mista Público-Privada Empatando Tua Vista é um ato político-folião crítico à verticalização excessiva, que negligencia o planejamento urbano, a história do lugar, privatiza o descortinar das águas, a paisagem e a vista dos monumentos”. Disponível em: <https://pt-br.facebook.com/empatandoatuavista>.

12 Um resumo do projeto pode ser acessado neste link: <http://crisederepresentacao.blogspot.com.br/>.

13 Ao mesmo tempo, o discurso da modernização é evocado para esconder ou mesmo tentar justificar as irregularidades dos processos administrativos que envolvem, em geral, empreendimentos de grande porte, como afirma a promotora Belize Câmara em Desconstrução Civil (2011). Disponível em: <https://vurto.com.br/2012/03/17/desconstrucao-civil/>.

Shared authorship: cinema, occupation, and the city

Pedro Severien is a journalist, he has a Master's degree in Film and Television Production. He is a screenwriter, producer, editor and director of documentaries, music videos, short films and feature films. He has experience in the area of Communication, with emphasis on audiovisual production and audiovisual activism.

How to quote this text: Severien, P., 2108. Shared authorship: cinema, occupation, and the city. V!RUS, Sao Carlos, 17. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus17/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 28, 2018

Abstract:

The starting point of my approach to participatory and collaborative forms in audiovisual authorship is the analysis of the films [projetotorresgemeas] (2011) and Novo Apocalipse Recife (2015). These works emerge from an engagement of their authors in the struggle for the right to the city. Such social disposition uses, in the city of Recife, cinema as a tool for the production of collective knowledge. By associating militant gestures of social movements with the films' forms of organization and aesthetic-narrative expressions, I use the concepts of multitude (Hardt and Negri, 2014) and right to the city (Harvey, 2012) to build a reflection on activist cinema and temporary urban communes, taking as an example the political interventions of the Occupy Estelita Movement and its initiatives for the democratization of urban planning.

Keywords: Audiovisual activism, Right to the city, Multitude, Occupation cinema

1Introduction

Cinema is born as a device that manages multiple contacts. Either the contact between the one who operates the camera and the subject which is in front of it, or the contact between people in a production team, or even the contact between spectators and the images traditionally screened within a collectivized space. The space of the movie theater also produces, therefore, a contact between the bodies brought together for a screening. As a technological apparatus for the capture and projection of images that was born in the industrial age at the turn of the century, the way these contacts were produced were soon influenced by the Fordist industrial model1.

These contacts, or rather, the relations between the subjects involved in the different stages of the productive chain of cinema, are then mediated by the dynamics of productivity in scale and by the compartmentalization of tasks. The logic of the production line is applied so that the film crew is organized by a hierarchy of roles, divided into an organization chart that determines creative, technical and financial agents. There has been a variety of possibilities and permeabilities between these instances from the beginnings of cinema to the present day.

But from the perspective of industrial cinema, the holders of capital and of the technical apparatus organize themselves as operators of a system, disputing not only control over modes of production, but also the cognitive and social effects of film reception. Viewers become regulated by an attempt of predetermination in which they are not seen as individuals or subjects, but rather as consumers. Therefore, the dominant narratives aim at a massive dissemination of these products to the consumers, while simultaneously aiming at producing them as such. One of the forces behind this operation is obvious: making movies to make money by seeking an effective production formula for that purpose.

[...] the industry works within clear paradigms for the transformation of matter into product to work ideally. It is necessary to put the subjects on an assembly line in which their subjective and creative capacities are left out – which is not to say that in the industry there is no creativity [...] It is necessary, in the limit, between design and product there be no change so that everything works in absolute predictability. For the industry, a policy of scarcity is needed, where copies are regulated; a new product means more raw material and assembly line time in operation; and therefore, cost (Migliorin, 2011, p.1, our translation).

As Shohat and Stam (2006) point out, the beginning of cinema coincides with the rise of imperialism. The dominant cinema expressed the voice of the winners of history and a significant part of this filmography idealized the colonial enterprise as a "civilizing mission." The images accompany the intense colonial disputes of rich countries for territories in the most vulnerable nations and regions. Thus, "the programmatically negative representations of the colonies helped to rationalize the human costs of the imperialist enterprise" (Stam, 2006, p.34, our translation).

Industrial or dominant cinema proved to be an effective operator of social relations, of the political images of the modern world and of new customs. However, as a language and a medium, cinema was also at the center of the struggles faced by revolutionary social groups, transgressors and libertarians. In addition to opposing dominant discourses, these groups produced archives of the political struggles for themselves and future generations.

This opposition/counterpoint establishes one of the bases for the discussion of a specific aspect of this historical and political trajectory: authorship. At the turn of the 21st century, there was a decline of industrial hegemony in the economy. And consequently, what emerged was immaterial capitalism, financial operations, speculative capital and the virtual Internet market.

If in the contemporary world value and subjects no longer have industry as a paradigm, such a passage, or overlap, from one form of value creation to another makes contemporary cinema establish strong dialogues with this configuration – which is not something all that new, but nonetheless it is still surprising in its consequences, in that it demands that social agents rethink problems of incentive, production and distribution under new compositions (Migliorin, 2011, p.1, our translation).

In post-industrial contemporary cinema, the technical division of labor, which separated specific roles, is often abolished or subverted. Online broadcasting from digital arrays adds yet another layer of complexity to the distribution dispute: corporate control of digital networks. At the same time, the post-industrial turnaround opens possibilities for reconfiguration of both auteurcinema2 and militant and insurrectionary cinemas. The political dimension of authorship traverses the history of cinema, but here this trajectory will be investigated from the perspective of a specific contemporary event: the Occupy Estelita Movement and the struggle for the right to the city in Recife.

The José Estelita pier is an area of ••more than 110 thousand square meters, located in the historic center of Recife. The land is on the edge of the Pina basin, an ecosystem that is crucial to the reproduction of several species of vegetation, birds, fish and crustaceans. Dozens of urban fishermen in the region make their living from this activity. The pier is also one of the major postcard landmarks of the city. In 2008, this public land was auctioned off illegally, and it was bought by the Novo Recife consortium. Made up of the companies Moura Dubeaux, Queiroz Galvão, Ara and GL Empreendimentos, the consortium intends to build up to thirteen towers, many of them more than 40 storeys high, divided between commercial establishments and luxury apartments.

I write about Ocupe Estelita as an audiovisual researcher and director, but also as an activist engaged in the social movement. I participated in the collective and collaborative production of a series of militant short films, as well as live broadcasts of protests, production of manifestos and temporary occupations, among other actions. One of the strategic characteristics of this mobilization that fights for the right to the city in Recife is precisely the articulation between different social dimensions, with the promotion of cultural activities, political assemblies and institutional disputes.

In this text, I propose a reflective path with the films produced in this encounter. I observe them together with the historical and anthropological processes that produce them, such as gestures and actions. I’m positioned nearby, therefore I’m half subject, half object in the sense indicated by Guattari (2012). I was one of the authors of Novo Apocalipse Recife3 (2015), a film made by the Ocupe Estelita Movement and the Carnival troupe Empatando Tua Vista, which will be part of the analysis of this text. The other film to be approached is [projetotorresgemeas]4 (2011), a collective production, which was born from a call for the production of images and narratives about power relations in the city. Both works turn to the production of city and collectivize the authorship as a political and aesthetic strategy. The focus of the reflection that I propose is: how can authorship-sharing modes produce commonality and thereby collaborate in the democratization of urban space?

2Cine-multitude

In April 2010, a post was made in social networks by a group of activists, identified only as [projetotorresgemeas], which was an invitation to gather interested parties to discuss power relations in urban territory through the production of a collective film. The call exposes a desire to mix perspectives, almost as a transposition to the audiovisual field of the concept of city as a mechanism to mix people together, as the following excerpt testifies:

Anyone – whether from Recife or not – can contribute to the work by producing material that will engage with the proposed discussion, with total freedom in the approach. There is no restriction in terms of the format of the material (film, video, photography, illustration, music, written text, etc.) or capture technology or genre (fiction, documentary, video art, interviews, essay, poetry, song, declamation, etc.). Although the starting point is the “Twin Towers”5, the material can and should expand to different territories and themes, which somehow interact with the initial discussion ([ProjetoTorresGemeas], 2010, n.p., our translation).

The [projetotorresgemeas] took the final form of a short film of 20 minutes, bringing together records that are used in subjective, ironic or poetic modes, or that take part in the “Real” to establish their narrative connections with the theme. The general narrative is designed precisely as an encounter of these gazes and different experiences of the city. The images go together on the screen, and the film is an amalgam of singularities expressed in the images. Altogether, 57 co-author directors took part in this project, of which the majority already had a connection with audiovisual production. But a significant part joined the initiative from other fields, including architecture and urbanism, the fight for housing, cultural production and the university. Let’s look at how this mobilization is expressed on the screen by focusing on certain scenes selected for analysis.

A plastic doll submerged in a pool; the perspective from the window of an airplane that flies over the city, turning to the stretch of waterfront occupied by skyscrapers; the shadows of the "Twin Towers" projected on the green waters of the Capibaribe River while the frame is crossed by a motor boat; or a woman dressed in the costume of a symbolic blind justice holding scales that carry models of upper class residential towers.

A criticism of the unequal city is present in sequences such as that of a maid who briefly enjoys the sea breeze and the view of the greenish horizon from the balcony of one of the ”Twin Towers” apartments and then continues her routine cleaning of the windows that frame this perspective. At the end of the day, the worker leaves this place of private peace, so recurrently reaffirmed in the ads for real estate in Recife, to then enter the chaotic and overpopulated universe of cars on the street, as shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

Fig. 1: Frame of [projetotorresgemeas]. Source: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Available at: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

Fig. 2: Frame of [projetotorresgemeas]. Source: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Available at: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

Fig. 1: Frame of [projetotorresgemeas]. Source: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Available at: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

By triggering its mixing mechanism, the assembly of images seems to disperse throughout the duration of the film another action that connects both aesthetically and spatially to the trajectory of the domestic worker. I am referring to a scene that shows a human-scale cardboard tower that walks the pedestrian strip and stands in front of the cars as a temporary advertisement at the red light. The use of traffic signals as a point of seduction of consumers is recurrent in the Recife real estate market. During the 2000s, there was a boom of economic growth in the entire country and in the state of Pernambuco, which over a few years grew more than the national average. During this period, it was common to find young people wearing uniforms at street lights distributing flyers for upcoming real estate developments. Figure 4 allows for the visualization of this procedure in a staged manner.

Fig. 4: Frame of [projetotorresgemeas]. Source: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Available at: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

The relationship between bodies is therefore divided by those who remain on the street, waiting for the red lights, to circulate among the cars, engaging with potential consumers who sit inside the cars. The contact occurs through a gap in the windows, which may or may not open. The ownership of a car, in this case, is a decisive factor in the pursuit of the target audience of consumers. Pedestrians on the sidewalks do not serve the real estate market; the owners of cars do.

In a visual revelation of this dynamic, the film shows, in an opposite shot of the cardboard tower standing in the pedestrian range, a young man, all shrunk up, serving as a human support for that façade, as shown in Figure 5. Once again, the film brings the image debate close to the bodies and their relationship with the materiality of space and its regimes of visibility. The cardboard tower frames a squeezed body. On the one hand, the car drivers and passengers, with their own windows to the outside world, see a surface of the image – the surface of consumption. On the opposite side, where only people crossing the pedestrian lane can see, is the impact on a body – the intentionally hidden result of this dynamic.

Fig. 5: Frame of [projetotorresgemeas]. Source: [projetotorresgemeas], 2011. Available at: <https://projetotorresgemeas.wordpress.com/assistir/> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

In another sequence, the film enters a ruined public building, located a few meters from the Pier Maurício de Nassau and Pier Duarte Coelho buildings. As the camera moves through this space occupied by families of homeless people, the soundtrack uses a jingle, an ad for a real estate project. There are children running barefoot on the stairs, toys scattered on the floor, several families occupying the space. Dialogically, image and sound construct a projection of the imminent future. The people occupying this public building will not stay there for long, they are all being subject to being removed due to the circle of wealth designed to "reshape" the city center.

This new landscape does not foresee the people who today occupy the housing center, but, rather, those who can enjoy it from the perspective of a consumer. Thus, a respective visuality is established for the demarcation of the spaces and organization of subjects. The last scene of the film appears to confirm this dynamic. Two white male bodies appear in the frame, positioning themselves with their pelvis in the foreground. In the center of the frame is the male genitalia, as the men begin to caress themselves. Gradually, the sexual organs become erect. When they reach full erection, the first and the last fields of the frame are interposed with mock-ups of the landscape surrounding the “Twin Towers”. The visual rhyme alludes to the phallic dimension of this image of the city associated with the centralization of power in a still patriarchal society. One of the cues seems to be: which subjects will be guaranteed an active role in this "new" urban space in construction?

Once again, the visual narrative refers to a distribution of visibilities in the neoliberal city, which organizes a precise division among those who see the horizon from above and turn their backs on the historic city and public space. From the street, the perspective is marked by the omnipresence of the two high buildings. By temporarily subverting this imposition, as in the maid scene observing the horizon from a terrace, the film states that a certain visibility implies the invisibility of an significant part of the population that has repeatedly been denied the right to present itself, to be visible in its singularities.

The construction of the Pier Maurício de Nassau and Pier Duarte Coelho buildings is confronted with urban legislation for a historic area, and the buildings by Moura Dubeux are erected on the Santa Rita Pier, near the historic center, even with a demolition order. The current project of transformation of the center that is underway includes the "Twin Towers" as a step of a much broader action that takes place according to the logic of gentrification. That is, these "renovations" serve to displace a low-income population contingent, which is withdrawn and removed from the center, in order to favor another group with higher purchasing power.

Lees, Slater and Wyly (2008) suggest that contemporary gentrification – based on large inequalities of wealth and power – resembles earlier waves of colonial and mercantile expansion that exploited national and continental differences in economic development. It was exported from the metropolises of North America, Western Europe, Australia and some Asian countries to new territories in former colonial possessions around the world.

This process privileges wealth and whiteness and reasserts the white Anglo appropriation of urban space and historical memory (W. Shaw 2000, 2005). And it universalizes the neoliberal principles of governing cities that force poor and vulnerable residents to endure gentrification as a process of colonization by more privileged classes (Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2008, p.167).

The city and the urban process that produces it are, therefore, important spheres of political, social and class struggle, since, as Harvey (2012) sustains, the urbanization of capital is linked not only to its capacity to "dominate urban process" in the perspective of control of state apparatus. Urbanization from the market perspective strategically uses processes of subjectivation as a form of exercise of power also over the lifestyles of the population, their capacity for work, their cultural and political values, their worldviews. In such a way that the dimension of the visible or of a right of the subjects to present themselves with their singularities, is centralized by the exclusionary logic of privatism and patriarchy. This process of concentration and asymmetry is closely linked to another equally vilified right: the right to the city.

The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individual or group access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change and reinvent the city more after our hearts' desire. It is, moreover, a collective rather than an individual right, since reinventing the city inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power over the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights (Harvey, 2012, p.4).

The Novo Recife project is a subsequent step in this plan to reshape an extensive stretch of waterfront that runs from the south coast, near the Port of Suape, on Cabo de São Agostinho, to the Naval Village in Olinda, as stated by urban planner Cristiano Borba in a testimony for the short film Recife, stolen city6 (2014). What the urban rights movements want is precisely the opening of this planning to social participation. This demand for participation conflicts directly with the interests of large companies that are the key players in the real estate market, in open adhesion to a production perspective of a city of consumption.

By confronting the processes of atomization of the neoliberal city, the film produces collectivity. It requires months of collective work, with regular face-to-face meetings and a mailing list for discussion. The filmmaking process requires organization, compromise and also a certain disposition for dissent, since the final version only uses part of the footage. In this perspective, collaboration and participation do not point to a community reduced to unity, but just the opposite – a collective that presupposes difference and its articulated singularities.

What [projetotorresgemeas] does with its gesture is a collectivization of the screen between different subjects that are juxtaposed, and it is in this juxtaposition that the film points to another possible city. Social criticism, irony, the symbolic, all this also operates in contact with the bodies mobilized for the making of the film. Initially, the short film suggests collaborative procedures that will be evoked during narrative and media disputes related to the destination of José Estelita quay. With the occupation of the wharf, which lasted about 50 days in its different phases, there is an intensification of cooperation processes for narrative production, not only in the audiovisual sector, but also in design, photography, manifesto writing and public activities.

The organization of this production and the sharing of the place of authorship arise in a variety of arrangements. The way to communalize the audiovisual production is directly linked to a collective strategy that is being reworked throughout the struggle of Occupy Estelita. As we will see later, shared authorship may point to a polyphony, as in [projetotorresgemeas], but not only this.

3Carnivalizing the institutional image

If in [projetotorresgemeas] there is a mixture in the textures of the different image and sound records, but also in the different narrative approaches immanent to the different subject-authors, in Novo Apocalipse Recife there is a centralization of the aesthetic regime of the film. While the first film points to a multiple city, articulated by the different natures of the image and the singularities included in a polyphonic narrative, in the second there is a frontal and unified attack. There is a target: the relationship of the mayor of the city of Recife, Geraldo Julio, PSB, elected in 2012 for his first term and re-elected in 2016, with the contractors that make up the Novo Recife Consortium.

In 2011, the saturation of the city's verticalization project began to gain a counterpoint through social mobilization, even if still dispersed and occasional, with articulation groups for urban rights and the "Twin Towers" as an inflection point. By 2014, the occupation of the Jose Estelita quay7 had acted as a catalyst for debates over the democratization of urban planning. As is ironically rendered by filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho in testimony to Recife, a stolen city8 (2014), the "Twin Towers" were just a trailer of what would come to be presented as Novo Recife.

The collective experience of the occupation, the attempts to negotiate with the municipal executive body and the violent repossession on June 17, 2014, had marked the bodies and the memory of the movement. There would be no end to attempts at social pressure and negotiation with the city executive. On June 30, 2014, the Ocupe Estelita Movement organized an occupation of the ground floor of the building of the City Hall of Recife. In an action that had repercussion through the digital networks and mobilized all the local press, the activists set up camp with a specific agenda: that the Novo Recife project be canceled.

The ground floor was occupied early in the morning, as shown in Figure 6. Immediately, the municipal security apparatus was activated, and in a few hours the building was closed, and municipal workers sent home. During the two days of occupation, there were a series of meetings between occupants and representatives of the city hall. However, in the end, the exit of the occupants was placed as an imposition and the city hall obtained in the Judiciary an order of reintegration of possession. The document established the departure by 2:00 p.m. on July 1, with the proviso that, if the occupants did not leave the building, the Military Police Shock Battalion would be called into action9.

Fig. 6: Frame of Ocupar, resistir, avançar, which shows the occupation of the ground floor of the building of the City Hall of Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KX6rirSw7c> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

The outcome of the city hall's occupation generates frustration. In general, the national and even international media repercussions of the occupation of the quay had an important empathetic effect on public opinion, bringing the support of a number of social actors, but from a practical point of view the Novo Recife project continued its course in the scope of the municipal executive. For this reason, there was the attempt of a direct intervention in the city hall. But the mobilization of the bodies was undergoing a post-occupancy hiatus, and the occupation of the city hall had required a great political effort of articulation without practical results. In addition to these factors, the consortium Novo Recife counter-attacked with a number of ads on the main television channels and an opinion poll that claimed that 80% of the population of Recife was in favor of the venture10.

Given this context, the argument for Novo Apocalipse Recife arises. The gesture of the film is in line with the gesture of the performance collective Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista11. Using a carnivalesque and provocative tone, the narrative resembles a parody advertising piece in which the mayor of Recife, Geraldo Julio – reincarnated with a paper mask –, makes an ode to the Novo Recife project. Aiming at provoking emotions and laughter, the movie parodies the music by Reginaldo Rossi entitled Recife, minha cidade.

In a series of playful situations, the character that represents the mayor acts in praise of the "qualities" of the Novo Recife project, whether dancing in swimming trunks with the insignia of the Pernambuco flag in front of the glass skyscrapers of the Boa Viagem neighborhood (Figure 7) or being led as a puppy by one of the fancy towers of the Troça Carnavalesca Empatando Tua Vista (Figure 8).

Fig. 7: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

Fig. 8: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

In a climactic moment of the film, the character-towers grow dizzyingly, like Godzillas, squash historical and vulnerable parts of the city (Figures 9 and 10) and catapult the mayor in the air like a superhero (Figure 11).

Fig. 9: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

Fig. 10: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

Fig. 11: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

The gesture of producing the image of a "new" mayor for a "new" city intends to unmask a face that is not always visible in power relations: the intimate association of private interests in the agenda of representatives of public power. In Figure 12, the new mayor celebrates the successful business with characters who carry in their heads paper bags stamped with the brands of the companies that make up the Novo Recife consortium.

Fig. 12: Frame of Novo Apocalipse Recife. Source: Movimento Ocupe Estelita, 2015. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uE0wJi6xNBk> [Accessed 29 October 2018].

In the case of Novo Apocalipse Recife, the asymmetry of institutional power, demonstrated by favoring real estate capital and contempt for popular participation, is investigated through a series of institutional negotiations. Thus, one should not look at the gesture of the film outside the recent history of the newest social movements producing a critique of the representative system, or its recurrent capture by capital. Looking specifically at the local context, one of the unfinished projects of activists and filmmakers involved in Novo Apocalipse Recife is another production of a collective call entitled Elections: Crisis of Representation12.

New Apocalypse Recife expresses the insistence of the Occupy Estelita Movement in denouncing the illegalities related to the wharf. It is worth pointing out that this insistence was challenged both by the municipal executive and by organized groups of society that formulated another narrative: that Novo Recife would represent the modernization of the city. The gesture of carnivalization of the image of the mayor remains associated with the gesture of the social movement for another discursive production: this supposed collective progress associated with a "modernization" tries to cover up the fact that projects like Novo Recife favor only the few13.

The José Estelita quay, as a space of a public nature, has the potential to bring together different individuals who can, in their own way, reconfigure the space, transforming it into a place of commonality. This power is in the matrix of the right to the city, as an essentially collective social device that offers a shared perspective in terms of the authorship of the processes of city production.

In its own way, the dilution of audiovisual authorship into a plurality that guides and enacts a narrative that has aesthetic cohesion does not erase the singularities of the people involved, but rather permits an expression that agencies collective affections. The germ of the film is equally materialized in a decentralized way, either through the performance interventions of the Troça Empatando Tua Vista, or in the series of meetings that took place for scriptwriting and debates for strategic decision making at assemblies and events organized by the Ocupe Estelita Movement.

Perhaps here it is worth looking back at a brief history of the Troça Empatando Tua Vista and its search for a more direct constraint of institutional politics. During Carnival, the group makes appearances during the traditional breakfast in the cabin of the Galo da Madrugada, the meeting place of politicians in the city. These actions have received recurrent restrictive reactions from the public power.

In the 2016 carnival, officials of the Urban Control Board prevented demonstrators from parading with the tower costumes. And the following year, military police officers seized the costumes. In 2018, the protesters obtained a precautionary habeas corpus to guarantee transit with the costumes. The film as a critical collective gesture unfolds this performativity before the institutionalized hierarchical power. With this, I don’t want to force a positivity of the film’s gesture, or even a presumed effectiveness. There is an ambivalence in the processes of carnivalization, whether on the discursive or the performative dimension. Shohat and Stam (2006) will also put forth the different lines of force that are in action depending on who carnivalizes who.

Historically, carnivals have always been politically ambiguous events; sometimes they constituted symbolic rebellions of the excluded, sometimes encouraged the festive transformation of the weak into scapegoats of the rich (or the less weak). Carnival and carnival practices are not essentially progressive or regressive: it all depends on who is carnivalizing who, in what historical situation, for what purposes and in what way. Carnival forms a changing configuration of symbolic practices, a complex dialogue between ideological manipulation and utopian desire whose political valence changes with each new context. Official power sometimes uses Carnival to carnivalize energies that could otherwise encourage popular revolts, just as carnival can also provoke disquiet among the elites and thus be the object of official repression (Shohat and Stam, 2006, p.23, our translation).

In the final editing phase of the film, the Occupy Estelita Movement decides to occupy the sidewalk in front of the building where the mayor lives. The occupation even allowed for a scene of this intervention to be included in the film, strengthening the bonds between the carnivalized narrative and the direct action of the collective.