Cidade e Narrativa: Discurso e direito à cidade nos espaços opacos

Anna Paula Ferraz Dias Vieira é arquiteta, Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Estuda direito à cidade, cultura marginal, luta por visibilidade.

Milton Esteves Junior é arquiteto, Doutor em História da Arquitetura, História da Cidade. Professor Associado da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. Coordenador dos Grupos de Pesquisa Conexão Vix e [Con]textos Urbanos. Estuda percepção, cognição e produção do território, planejamento urbano e qualidade do ambiente construído, assentamentos humanos e qualidade de vida.

Como citar esse texto: VIEIRA, A. P. F. D.; ESTEVES JÚNIOR, M. Cidade e Narrativa: Discurso e direito à cidade nos espaços opacos.V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 17, 2018. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus17/?sec=4&item=5&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 28 DE AGOSTO DE 2018

Resumo

A cidade fragmentada territorializa desigualdades, legitimada por um discurso hegemônico que serve a ideias e valores dominantes. De seus espaços física e socialmente fracionados escolhe aqueles que ilumina, que aparecem na imagem da cidade do espetáculo, e aqueles que lançará à sombra e invisibilizará. Mitigando subjetividades e rejeitando comportamentos e discursos desviantes, constrói, molda, enquadra a cidade que deseja ser e mostrar. Nos limites onde cessa a visibilidade, a cidade está, porém, em contínua produção. A sombra que acoberta os territórios marginalizados, também os revela por escaparem suas práticas à compreensão do olhar totalizador. Por meio da cultura marginal, a periferia espalha sua sombra sobre as zonas iluminadas da cidade, pintando com sua subjetividade, dando novos sentidos, disputando seus espaços e discursos. Dos territórios periféricos emanam outras narrativas da cidade e despertam sentimentos de colaboração entre parceiros em situações e com opiniões semelhantes objetivando conquistar espaços em prol da participação cidadã. Sob aportes teóricos de Michel de Certeau e Milton Santos, principalmente, deseja-se debater a distribuição desigual do direito à fala e à visibilidade, e evidenciar as “maneiras de fazer” dos espaços opacos, que disputam a cidade e suas narrativas, permitindo que se lancem sobre ela novos olhares, que se contem outras histórias e que, assim, se expanda o direito sobre esta. Cumpre-se aqui apresentar o direito ao discurso como direito à cidade, traduzido em lutas efetivas e desconstrução de estigmas sociais.

Palavras-Chave: Narrativa, Espaço Luminoso, Opaco, Cidade, Marginal

1Introdução

A cidade regida pela lógica econômica e social produtivista está em disputa. Sua configuração urbana vem resultando de processos historicamente marcados pela desigualdade de direitos e pela segregação socioespacial. Entendemos o conceito de configurações territoriais como a materialização das funções, dos usos e das usanças efetivadas no território, uma acepção que inclui tanto o espaço-materialidade quanto as ações dos sujeitos que neste se instalam e que sobre ele se referem. Tratamos, aqui, de fenômenos socioespaciais convertidos em territórios e em territorialidades vivenciais, bem como em narrativas destinadas a expressá-los e que nos fazem refletir sobre eles. Tratamos, portanto, de formulações e de fenômenos polifônicos e plurissígnicos que envolvem e demandam leituras polifônicas e dialógicas1. A quantidade e a complexidade envolvidas no entendimento e expressão dessas questões exigem clivagem, aqui estabelecida na seleção de narrativas que se contrapõem ao discurso hegemônico, o qual se sustenta na distribuição assimétrica do direito à enunciação para ratificar os aparelhos produtores de situações nefastas como as citadas desigualdade e segregação socioespaciais.

Apesar da multiplicidade de formas e meios pelos quais a cidade se expressa e pode ser lida, sentida e interpretada, é perene a tentativa de impor-lhe uma marca por meio de um discurso que contenha, sintetize e uniformize sua identidade. Esta cria uma imagem daquilo que o discurso oficial deseja mostrar; constrói uma ideia de território a partir de um consenso que sombreia e invisibiliza o que diverge de tal imagem, que suprime aquilo que lhe possa pressupor dissenso. Ou seja, essa busca por uma imagem identitária da cidade promove um discurso que preza o harmônico e o consensual e suprime o divergente, o diverso, o conflituoso, o dissonante (PALLOMBINI apud VIEIRA, 2012).

Os modos de ver, vivenciar e narrar a cidade não admitem o consenso, pois fazem parte de processos de subjetivação (individuais ou coletivos) que variam a cada experienciação. A cidade não é um todo homogêneo e indivisível; ela é composta por múltiplos e distintos componentes sociais e culturais; por conseguinte, ela se faz igualmente múltipla e diversa em cada uma de suas partes. A concepção discursiva hegemônica da cidade deriva de um discurso que ecoa e espalha uma imagem da cidade que, na maioria das vezes, vai de encontro a narrativas outras que querem se fazer ver. Narrativas outras compostas por experiências, corpos e vidas que também fazem parte da cidade e que dela falam, mas que, devido à hegemonia do discurso dominante, são obscurecidas e deslegitimadas, seja pelo não reconhecimento de sua cientificidade, seja por fatores socioculturais que marcam seus locutores (gênero, etnia, níveis socioeconômicos etc.), seja pelo território de origem destes. O discurso hegemônico anula aquilo que não consegue controlar, furtando seus movimentos, suas gingas e suas habilidades, limitando suas intensidades, enquadrando suas táticas e pintando de cinza suas cores vivas. Enunciado por locutores previamente definidos, invalida as demais vozes e narrativas para definir o curso da história e os modos como esta deve ser contada. Escolhe suas vozes das quais emana todo o saber e toda a consciência, ainda que de modo ilusório e falso (DEBORD, 1997).

Nos limiares da visibilidade, após as fronteiras duras e luminosas que dividem a cidade –centro-periferia, asfalto-morro, formal-informal–, há uma incessante produção que causa estranheza ao olhar totalizador (CERTEAU, 2014). Das áreas opacas2, entre marginalizados social, econômica, cultural e geograficamente, emanam outros discursos sobre a cidade, que costumam ser obscurecidos ou calados ao serem considerados “irracionais para usos hegemônicos” (SANTOS, 2006, p. 210). As zonas opacas assim o são porque sobre elas não se lança luz, porque não lhes é permitido aparecer, nem que suas manifestações de resistência cheguem à superfície. Sobre esses espaços, o olhar age predominantemente de modo instrumentalizado.

Esses espaços “impossíveis de gerir” (CERTEAU, 2014) são os que mais sofrem a violência do enquadramento na dura tentativa de imprimir-lhes uma identidade. Os movimentos de invisibilização dos espaços opacos se dão não apenas por sua negação, pelo apagamento do que é desvio, mas também pela imposição de um estereótipo. Os espaços opacos, identificados como territórios de pobreza, são usualmente vinculados a situações de violência, de exclusão e de falta (VIEIRA, 2012). A ênfase nesses aspectos negativos, decorrentes de um sistema ancorado na desigualdade, gera um afastamento em relação às áreas opacas da cidade, aprofundando as fronteiras que a divide e nublando o que nela se produz de diverso ao que se espera ali encontrar.

A miséria e escassez fazem parte do cotidiano dos espaços opacos, mas a solidariedade, a lida e a resistência também são marcas desses territórios da criatividade. A cultura é produzida abundantemente nas periferias3, mas são as vozes autorizadoras que partem de fora delas, e não de dentro, que as legitimam ou criminalizam. As tentativas de invisibilização das áreas opacas não ocorrem sem que parta delas movimentos de resistência, não reativo, mas intrínsecos ao processo de espetacularização. É de dentro desse processo que a crítica, em forma de desvios e fissuras, se dá enquanto microrresistências (JACQUES, 2010). Dos territórios periféricos emanam outras narrativas da cidade, que disputam seus espaços e seus discursos, e despertam sentimentos de colaboração entre parceiros em situações e com opiniões semelhantes objetivando conquistar espaços em prol da participação cidadã.

Nas áreas opacas da cidade presenciam-se ações táticas, tanto em suas maneiras de habitar as parcelas periféricas ou marginalizadas da cidade –modos de construir, adaptar, modificar a geografia e o habitat– quanto de circular na cidade, transpondo limites impostos e ocupando espaços e discursos. A cultura periférica, em suas diversas formas de manifestação –literatura marginal, saraus, slams, samba, funk, rap, hip hop, grafite...– atua como microrresistências aos processos de silenciamento impostos à periferia e ocupa rádios, praças, calçadas, escadarias e paredes. Desse modo, revela o dissenso, tensiona o espaço urbano disputando-o e distorcendo as relações de poder nele existentes, tornando novamente político o espaço espetacularizado pelo discurso: “a vida urbana pressupõe encontros, confrontos das diferenças, conhecimentos e reconhecimentos recíprocos (inclusive no confronto ideológico e político) dos modos de viver” (LEFEBVRE, 2001, p. 22).

A narrativa da cultura marginal busca destruir o fundamento que legitima o discurso oficial para circulação das ideias, busca derrubar as hierarquias que definem aqueles que têm competência para falar e ser ouvido. O discurso “[...] não é simplesmente aquilo que traduz lutas ou os sistemas de dominação, mas aquilo por que, pelo que se luta, o poder do qual nos queremos apoderar” (FOUCAULT, 1996, p. 10). A cultura marginal periférica reivindica o seu lugar de narrador, conscientizando os sujeitos marginalizados de que podem, sim, dizer além do que lhes é autorizado; ela o faz questionando a autoridade de quem fala pelo outro, ao qual delega sua voz e acaba por vê-la reduzida e racionalizada. A cultura marginal emerge como ferramenta de empoderamento das áreas periféricas, tratando suas múltiplas versões da história como meio de sobrevivência desses espaços opacizados (BAPTISTA, 2001). Tematizam, em geral, a vida na periferia, reclamando o direito à voz e à construção do conhecimento por aqueles que não habitam os lugares da fala.

Os espaços periféricos, que sob um prisma hegemônico, seriam identificados por estigmas de violência, miséria e falta, em posse de seu lugar de narrador são ressignificados e valorizados: revelando sua intensa produção cultural; expondo a ginga com que seus corpos se movem na cidade formal e nas “quebradas”; enunciando sua capacidade de falar sobre o cotidiano vivenciado nas experiências subjetivas; relatando sobre suas lidas individuais e seus processos, mas também sobre a solidariedade entre seus moradores; denunciando e enfrentando a violência decorrente da desigualdade bem como dos aparelhos de captura, de vigilância e de controle.

A partir do estudo de narrativas marginais, pretende-se debater sobre o direito à cidade e aos instrumentos discursivos sobre a vida nesta. Partindo da hipótese da disputa pela cidade e pelo direito de sobre ela e nela se enunciar, deixou-se ser guiado pelas narrativas que emanam da cultura periférica como forma de compreensão da cidade a partir de um olhar não mais totalizador, mas um olhar outro, que conta uma outra história, e que colabora e amplia a produção de conhecimentos sobre a cidade e seu entendimento.

O discurso da cidade pacífica e harmoniosa tenta invisibilizar tanto porções geográficas do espaço urbano, como sua população, suas produções e lutas. Milton Santos (2007) amplia o conceito de território para mais além do que se resume ao espaço físico, expandindo-o para o lugar onde acontecem as ações, as paixões, os poderes, as forças, as fraquezas, ou seja, corresponde ao espaço onde o homem se manifesta e constrói sua existência. Fala-se, então, de territórios obscurecidos. Da tentativa de ocultação e apagamento de espaços, bem como dos modos de vida que abrigam, suas lutas, seus desafios, suas criações, a violência a que estão submetidos, ou seja, de tudo o que escapa e diverge ao discurso que afirma sobre a cidade e a pobreza tudo saber (VIEIRA, 2012).

Reside nos territórios obscurecidos uma intensa produção de cultura e de narrativas, que apesar de invisibilizadas e silenciadas, atuam desestabilizando o lugar de mero objeto que lhes é imposto, produzindo a própria cidade e também conhecimento sobre esta. A distribuição assimétrica do direito à cidade em espaço e discurso justifica a necessidade de acessar a vida nos territórios opacos a partir da ótica e das narrativas de seus moradores.

2A narrativa a cidade e o direito a esta na ótica dos espaços opacos

A Região Metropolitana da Grande Vitória (RMGV) tem testemunhado um grande crescimento dos movimentos relacionados à cultura marginal. Impulsionado pelo movimento hip hop, vê-se florescer numerosos coletivos que se organizam em torno da produção da literatura, da música, da rima, da dança, do grafite, etc. É crescente, também, o número de encontros gerados por essas manifestações, que todos os dias da semana ocupam os espaços públicos e institucionais com saraus, slams, batalhas de rap e de break, para citar alguns exemplos.

No intento de encontrar narrativas silenciadas sobre a cidade, buscou-se o movimento literário periférico, já conhecido de outros lugares do Brasil, em suas manifestações na RMGV. O encontro com a literatura marginal4, impulsionado pelo incômodo com o silenciamento dos territórios periféricos e com a vida que não se enquadra à imagem imposta pelo discurso oficial da cidade formal, disparou uma série de conexões e entradas em direção às narrativas produzidas pela população desses mesmos territórios. O Coletivo Literatura MarginalES, composto por jovens escritores da Grande Vitória, foi o primeiro acesso aos grupos dedicados à literatura marginal produzida na região. Rapidamente outras várias conexões se estabeleceram, e desse emaranhado formou-se uma rede de movimentos distintos, mas que convergiam tanto em seu conteúdo quanto em seus atores, e davam suporte à vontade de falar dos territórios e vidas silenciados. O encontro com esse primeiro coletivo de literatura marginal abriu caminho para uma série de outros encontros com grupos que praticam a palavra escrita e a oralidade dos saraus, slams e batalhas de hip hop.

Esses grupos não falam de localidades ou bairros específicos, mas se pronunciam, de modo geral, sobre as áreas opacas. A origem dos integrantes desses coletivos e dos participantes dos saraus e das batalhas é múltipla, são moradores de diferentes bairros dos diversos municípios da RMGV, mas o teor principal das falas tende a ser o mesmo: os modos de vida das áreas periféricas, a denúncia da privação dos direitos de participação e o desejo de visibilidade, o desejo da enunciação. Buscou-se acessar, por meio da literatura marginal, dos saraus e do hip hop, narrativas dissonantes advindas de espaços opacos, que revelassem outros modos de ser e viver na cidade, bem como fossem formas de resistência à invisibilidade e ao silêncio. Não apenas relatos descritivos, mas a própria experiência de tentar participar da produção do espaço e da vida urbana. Participou-se de grande número de eventos de cultura marginal e encontros que festejassem a oralidade narrativa, registrando suas falas e suas produções poéticas em tom de luta, desabafo, denúncia e celebração, bem como coletando as produções gráficas (fanzines, livros) de literatura marginal, buscando, desta forma, acessar outras narrativas que vêm sendo construídas e, também, obscurecidas sobre a cidade5.

O lugar de morada dos indivíduos exerce papel determinante para o exercício pleno da cidadania, permitindo ou não o acesso aos serviços públicos e à vida com urbanidade. O modelo desenvolvimentista urbano excluiu as camadas de menor renda da participação nos avanços do país. Trata-se de um modelo de desenvolvimento que institucionalizou a segregação socioespacial, por meio da qual se produz um espaço urbano que não apenas reflete as desigualdades, como também as reafirma e reproduz (MARICATO, 2002). A segregação socioespacial gera e reafirma a exclusão social, reservando à população dos espaços mais pobres uma inserção precária na cidade, mesmo quando espacialmente incluída nela, tal como relatado na poesia:

Aqui é Tão Tão Distante

Em Tão Tão Distante

Havia uma favela chamada Perto Daqui

Em Tão Tão Distante tinha tudo

Saúde, educação, lazer

Arte e cultura pros irmão

Mas em Perto Daqui

Não tinha saúde, não tinha lazer, não tinha educação

Tinha muito enquadro de polícia, tiro e exploração

Faltava arroz, faltava feijão

Aqui é Tão Tão Distante

E Tão Tão Distante é perto daqui

(Slam Botocudos, 27 de abril de 2017)

Essa poesia, recitada em uma batalha poética do Slam Botocudos, evento de cultura marginal da Grande Vitória, evidencia a dimensão do que é viver e sobreviver nos espaços urbanos reservados aos pobres. Os fragmentos de uma cidade múltipla e segregada, capazes de se tocar devido à proximidade espacial, se separam pela fronteira dura da prática do poder, onde realidades tão diversas são confrontadas de tal modo que a desvantagem de um se traduz na vantagem do outro. Na poesia, o “Tão Tão Distante” e o “Perto Daqui” revelam a constituição do espaço geográfico da cidade. A qualidade de vida almejada pela periferia – que inclui acesso à saúde, a educação, o lazer, a cultura, a alimentação, a segurança – está muito distante apesar de ser desfrutada logo ao lado. Essa narrativa retrata o modelo segregacionista das cidades brasileiras, frequentemente denunciado por aqueles que vivem na ilegalidade devido à exclusão socioespacial.

Tal ilegalidade torna-se funcional, pois a partir dela se sustentam relações políticas arcaicas, trocas de favores e clientelismos, com vistas à especulação imobiliária e à aplicação arbitrária da lei (MARICATO, 2002). A narrativa denuncia ainda a violência sofrida cotidianamente nas periferias, pela presença opressora do Estado ou por sua indiferença ante a verdadeira guerra civil que acontece em nossas cidades; revela um inconformismo diante do tratamento desigual direcionado aos diferentes espaços urbanos, tal como nos trechos poéticos abaixo:

Nós somos sentenciados e nem é no judiciário

Esse é o eco dos bueiros que invade o bairro nobre

Infelizmente lá também não sobem as tropas de choque

Só presta pra subir morro

Matar bandido que é pobre

Enquadrando morador

Forjando que vão apreender revolver

“Levanta a mão! Olha pra parede!”

(Gnom, Sarau Emprete-Sendo, 30 de maio de 2017)

Um homem comum

Mete uma ação

E fica na cadeia até virar carcaça

Um engravatado rouba uma nação

E a maior punição é ficar preso dentro da própria casa

(Projeto Boca a Boca, 12 de maio de 2017)

As poesias acima expõem as distintas abordagens relativas e proporcionais à desigualdade socioespacial, seja na forma com que a força de segurança se apresenta, seja nos instrumentos punição que essa pressupõe. A polícia se configura, dessa forma, como um aparelho de manutenção da segregação socioespacial, necessária aos processos de dominação pelo tratamento diferenciado que concede às diferentes camadas sociais (MOASSAB, 2011). Medo para uns, segurança para outros, a polícia representa um instrumento de controle social do Estado contra a classe de “criminosos natos”, entenda-se: favelados, pobres, negros. A revelação do tratamento violento da polícia vem acompanhada de uma crítica ao tipo de urbanização realizada nos territórios obscurecidos. Para essa população resta apenas a defesa por meio das denúncias possíveis.

E eles encheram a favela de pracinha

Apenas pra facilitar o enquadro

E boy nenhum pode falar de favela

Pois ele não convive com a morte do seu lado

(Sarau Emprete-Sendo, 20 de junho 2017)

A presença do Estado nesses territórios é precária e ineficiente. Em muitas ocasiões, menciona-se a falta de saneamento nos territórios de pobreza, destacando a dificuldade de acesso à água tratada e ao esgoto:

E eu tenho sede

Mas não é mais de sangue

Não é mais de sangue

Só da água potável

Que nunca chegou em cima do morro

(Sarau Emprete-Sendo, 30 de maio de 2017)

Aqui não tem a riqueza, mas tem a beleza de ser feliz

Feliz, feliz

Aqui o banquete nos faz das migalhas que o Estado fornece pra ser feliz

Infeliz

Rua de barro

Morro

Esgoto a céu aberto

(Slam Botocudos/Sarau Emprete-Sendo, Casa da Barão, Centro, Vitória, 27 de julho de 2017)

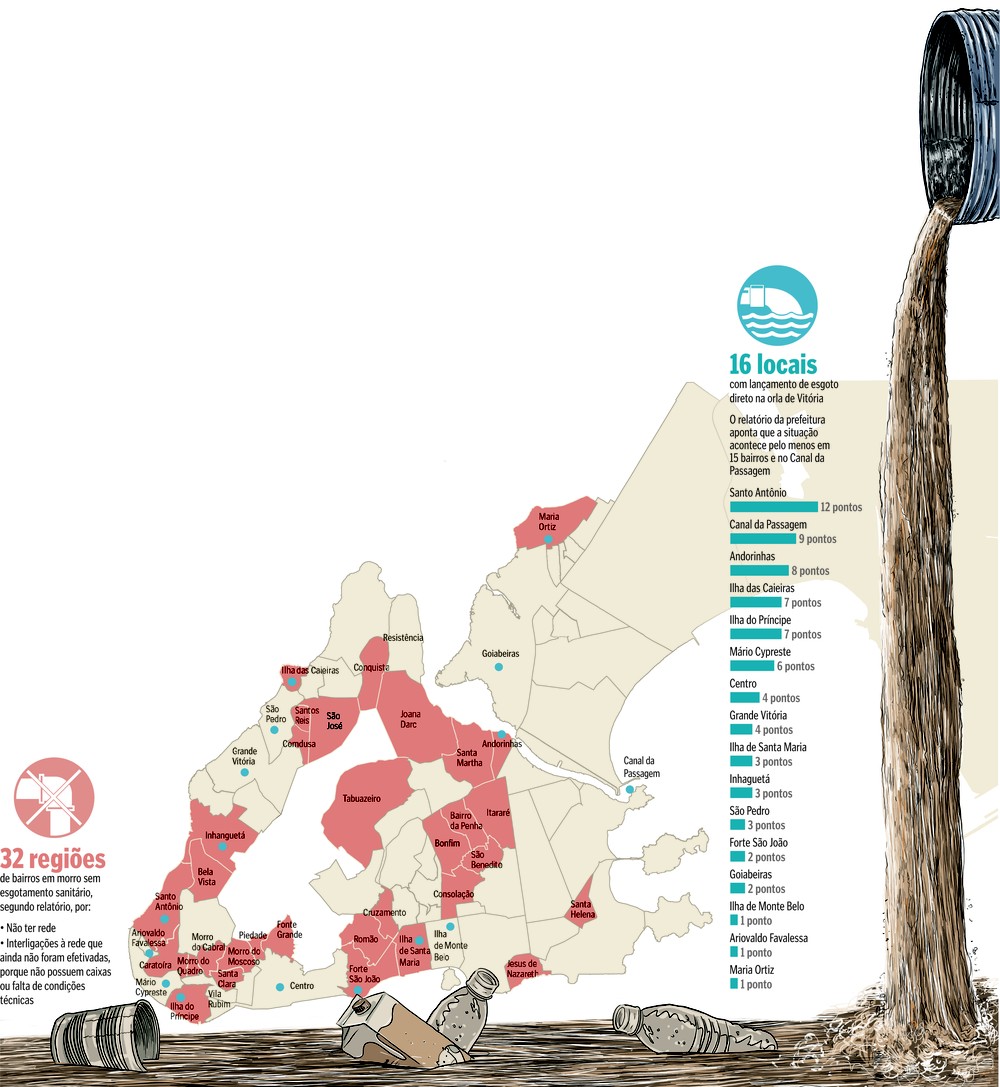

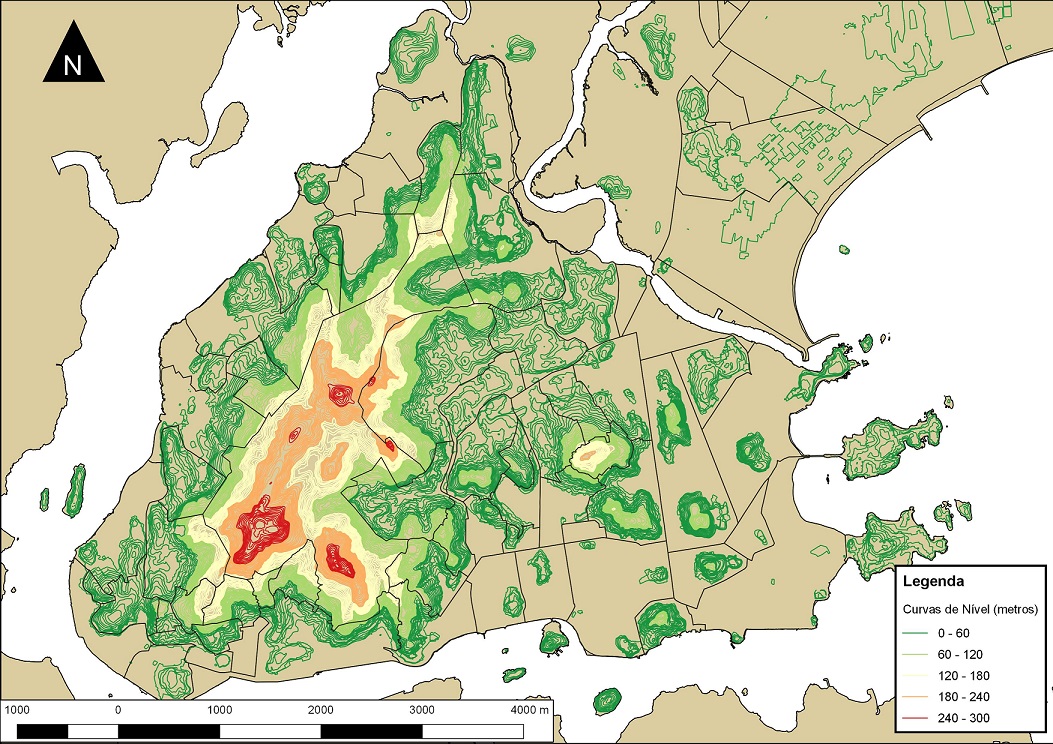

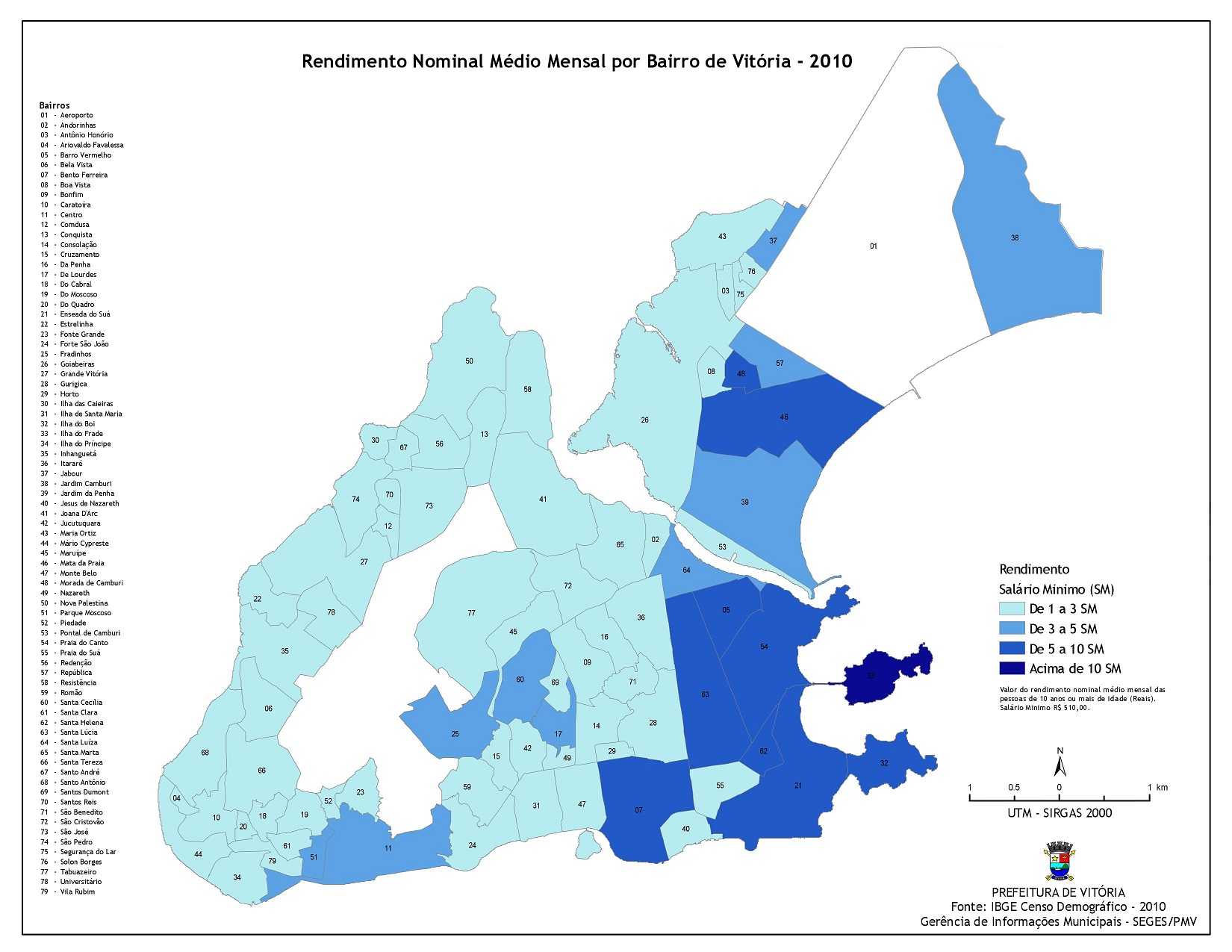

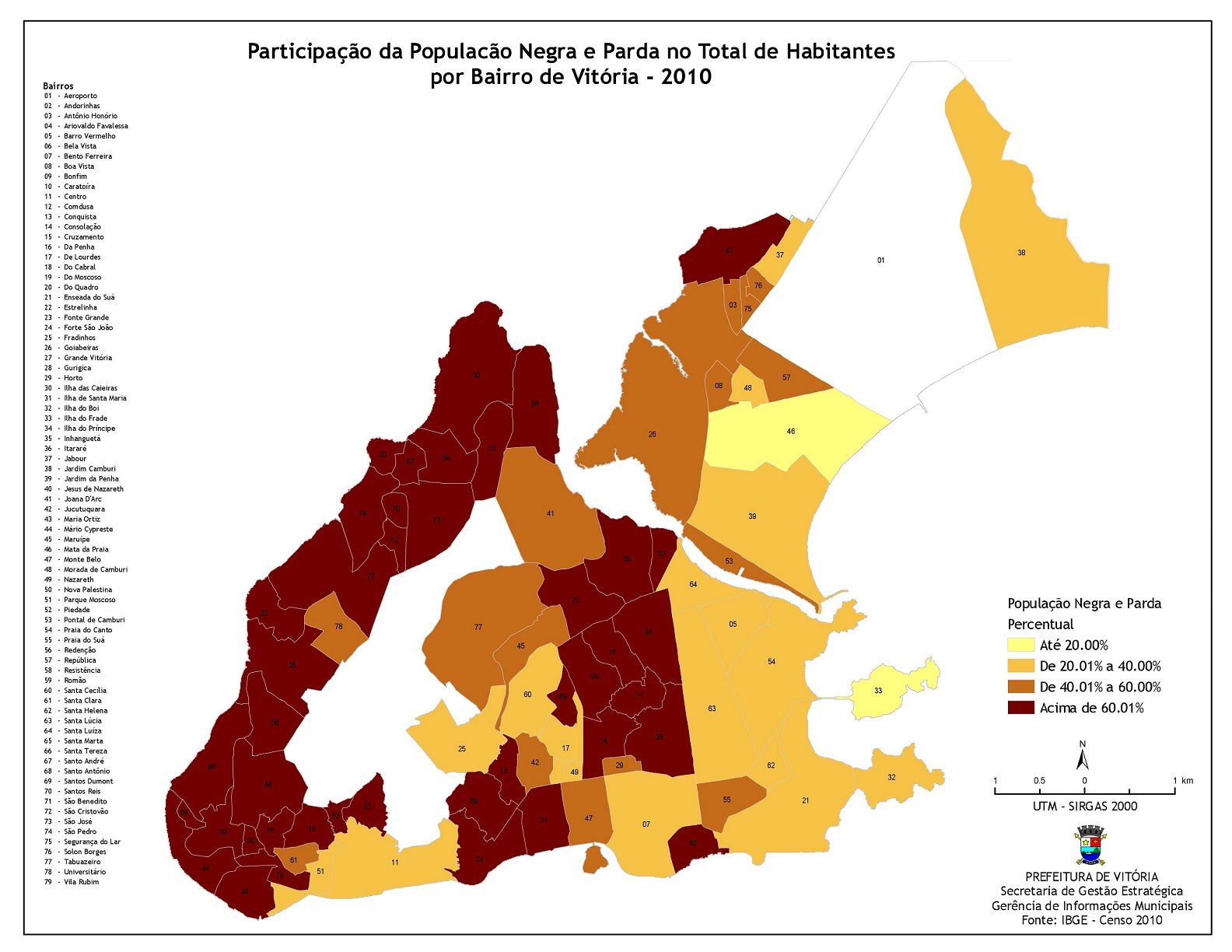

Segundo a Cesan (Companhia Espírito Santense de Saneamento), em 2016 o município de Vitória tinha 88,7% de cobertura da rede de esgoto, sendo aproximadamente 69,6% da população da capital conectada à rede6. Apesar de Vitória apresentar a melhor situação em rede de saneamento entre os municípios da Região Metropolitana, ainda está longe do ideal. As regiões não atendidas pelo sistema de esgotamento sanitário da capital (32 dos 79 bairros) se localizam nos morros e bairros da periferia, principalmente da baía noroeste, como demonstra imagem abaixo, de um levantamento periodístico realizado, e conforme denunciam as narrativas periféricas. O mapa apresentado abaixo (Figura 1), apresenta a cobertura da rede de esgoto e os locais de lançamento das águas servidas no município de Vitória subdivida em bairros; a seguir, na Figura 2, que destaca a topografia do município, nota-se que os bairros não servidos ou servidos precariamente pela citada rede de esgoto, encontram-se principalmente nos morros e bairros periféricos.

Fig. 1: Mapa de Vitória indicando regiões sem cobertura da rede de esgoto e os locais de lançamento desse esgoto na orla da capital capixaba. Fonte: SÁ; VERLI, 2017, s.p.

Fig. 2: Mapa Topográfico Altimétrico de Vitória. Fonte: Acervo Pessoal (desenvolvido a partir de base de dados da Prefeitura Municipal de Vitória, ES).

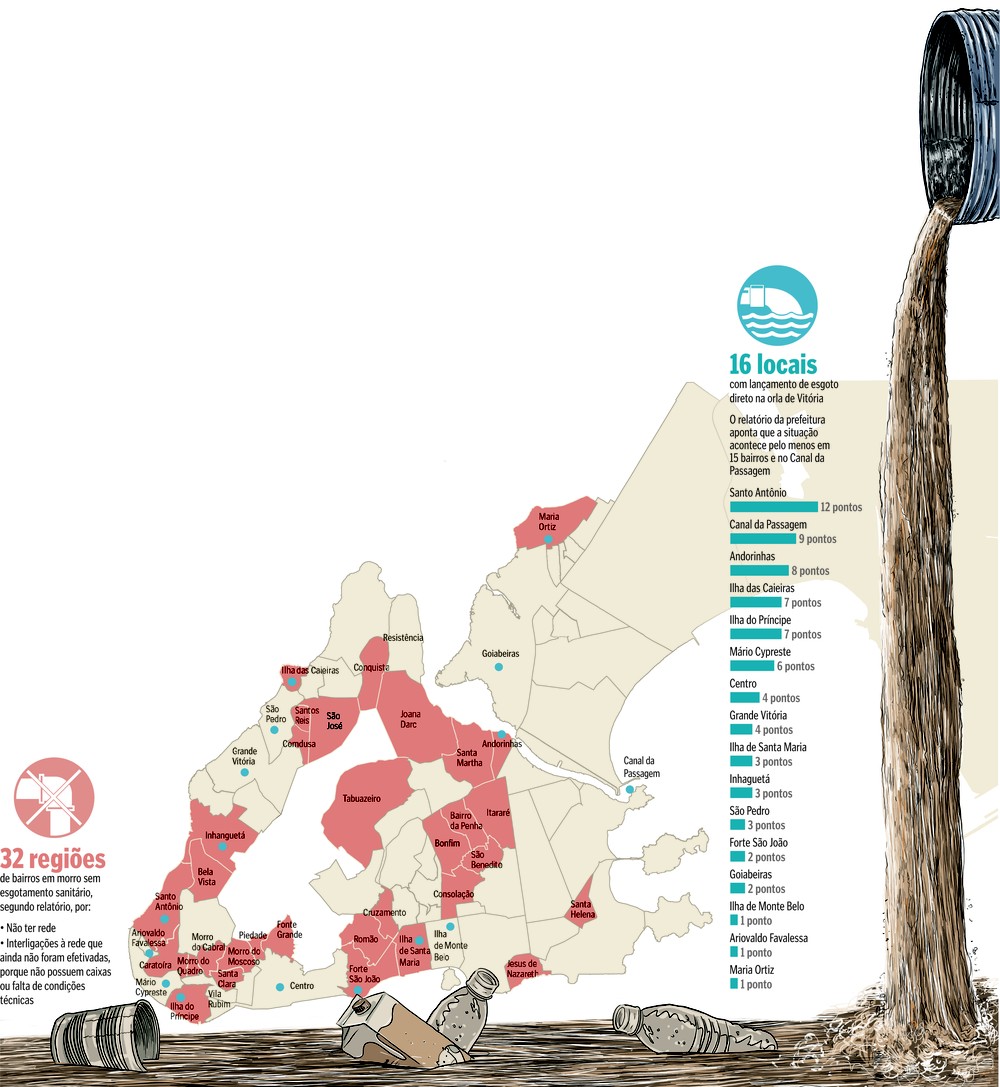

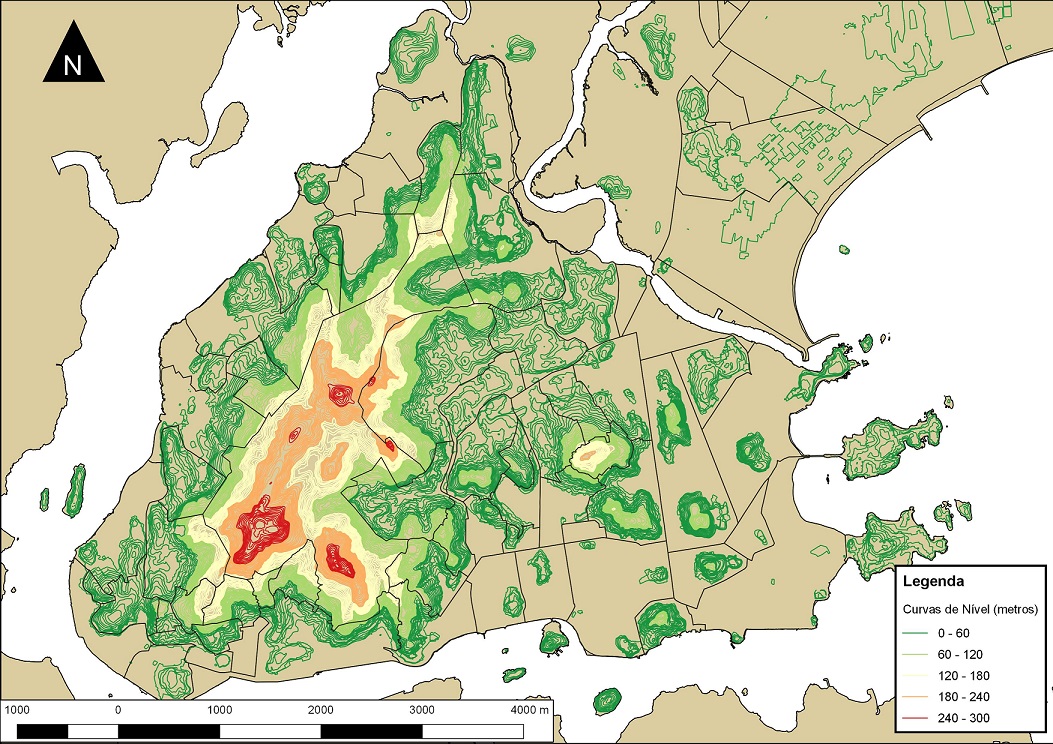

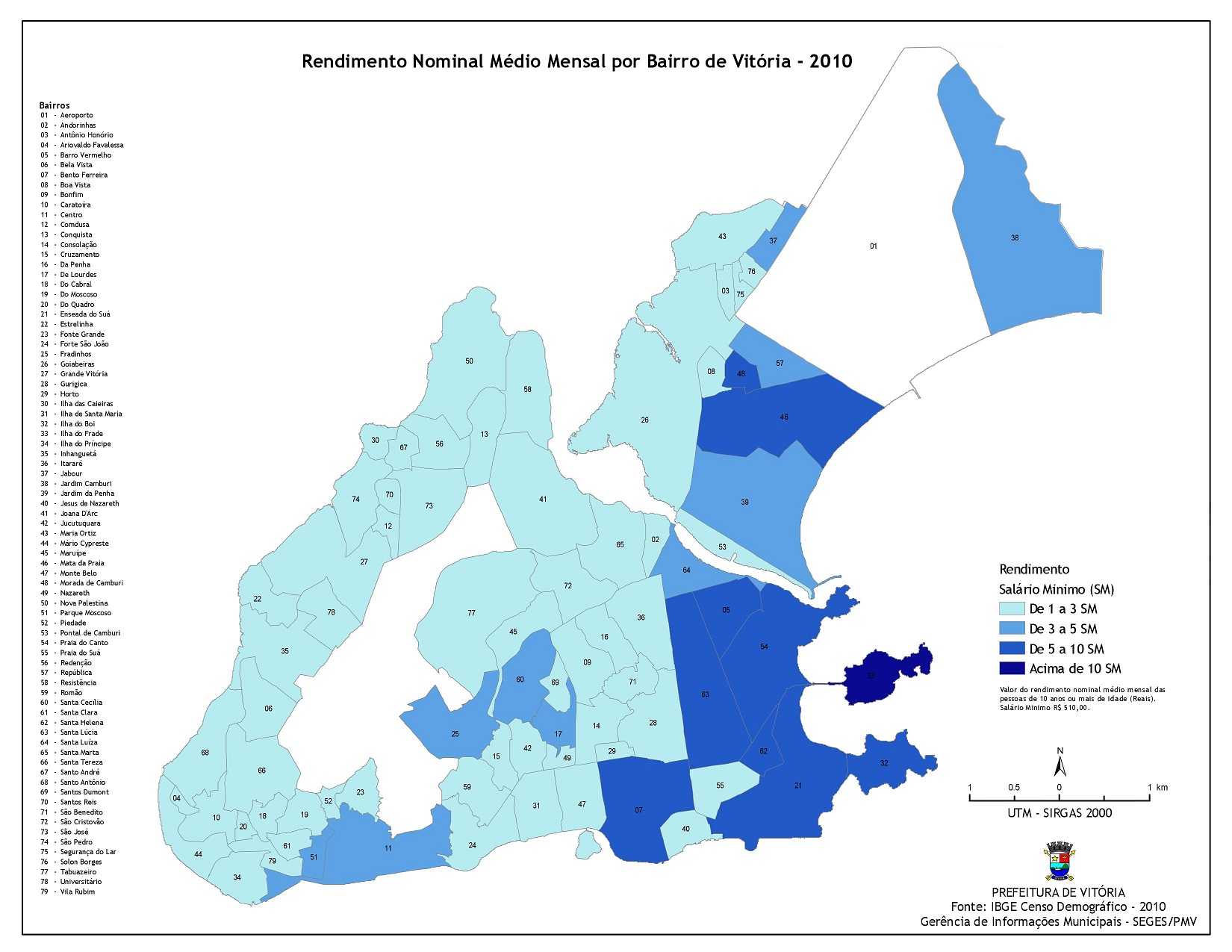

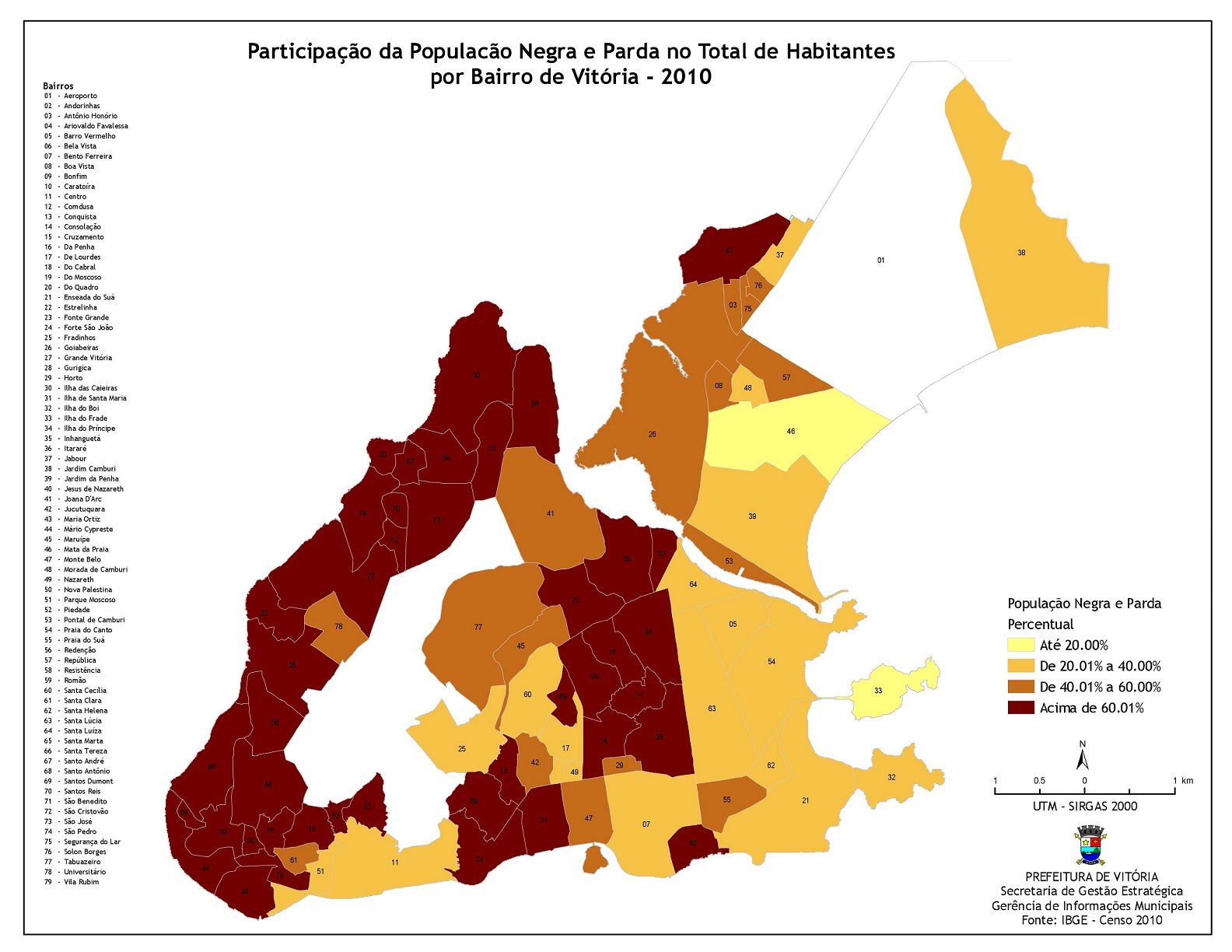

As regiões onde o acesso aos serviços de saneamento básico e água são mais precários, como pode ser observado nos mapas, são também as áreas onde se situa a população com menor renda e onde há a maior concentração da população negra e parda da capital. Os mapas a seguir (Figuras 3 e 4) demonstram a distribuição socioespacial desigual estruturante da cidade de Vitória, baseada na segregação e na concentração de terras das camadas altas da sociedade, reservando aos pobres, negros e excluídos o assentamento em áreas irregulares, de difícil acesso, carentes de infraestrutura e da presença do Estado.

Fig. 3: Rendimento Nominal Médio Mensal por Bairro de Vitória 2010. Fonte: Prefeitura Municipal de Vitória, 2010.

Fig. 4: Participação da População Negra e Parda no Total de Habitantes por Bairro de Vitória 2010. Fonte: Prefeitura Municipal de Vitória, 2010.

A vida nesses espaços é narrada nas poesias marginais e nos raps, que retratam a batalha pela sobrevivência cotidiana, bem como as relações dentro das comunidades. Versam sobre a luta que pressupõe existir na cidade desigual, nos espaços ocultados pelos instrumentos políticos e seus discursos ideológicos, os quais detêm o domínio do espaço urbano.

A construção discursiva e simbólica do que é “cidade” e “periferia” torna a cidadania um privilégio e não um direito, encobrindo a cidade real com a cidade que se quer ver (MARICATO, 2001). Com base no ideário de cidade forjado hegemonicamente, a periferia é tida unicamente como o lugar da violência, da criminalidade, da falta de recursos, de infraestrutura e de cultura, configura, portanto, uma não-cidade dentro da cidade (MOASSAB, 2011).

A imagem da cidade pacífica e democrática oculta os processos segregacionistas e excludentes que constituem o urbano, bem como os conflitos provocados pela desigualdade. A desconstrução dessa imagem tendenciosa é fundamental à busca de um espaço urbano menos desigual. Nesse sentido, as narrativas marginais da literatura, do rap e da arte da periferia têm importante papel na exposição do processo histórico de exclusão, assim como para ressignificação da cidade. As manifestações artísticas fazem emergir um intenso debate sobre as profundas desigualdades sociais e urbanas da periferia, buscando caminhos para reversão desse quadro.

Porque eu escrevo letra que retrata a nossa realidade

Que vai do descaso social à criminalidade

Atuante em lugar onde ninguém, ninguém

Ninguém quer entrar

(Sarau Quebrando o Silêncio, 19 de setembro de 2017)

São travadas, dessa forma, batalhas para a desconstrução da carga simbólica pejorativa que sempre pesou sobre os moradores das regiões pobres; bem como para o reconhecimento de suas manifestações culturais e do saber por essas produzido, a partir de uma legitimação interna. Para enfrentar os desdobramentos da histórica segregação espacial (tais como violência e infraestrutura precária, já citadas), o que se vê nos espaços periféricos é uma intensa relação de cooperatividade e de responsabilidade com o próximo, reforçando a importância das citadas redes de colaboração e participação; o que se vê é uma diversificada e crescente produção cultural acompanhada de iniciativas empreendedoras. Ou seja, trata-se de uma periferia que se diferencia muito da imagem que o discurso hegemônico tenta enquadrar. Como nos trechos narrados em destaque abaixo:

Lá o coletivo é de vizinhos enchendo a laje

E como dizia Gaspar um povo “quem tem cor age”

(Trecho da música #VocêsFizeramDissCriminação de Diego Cavaleiro Andante)

As narrativas marginais operam na contramão dos instrumentos de dominação, reformulando simbolicamente as periferias. Disputam a cidade em seus espaços; ocupam a cidade por meio de seu discurso. Travam-se batalhas contra uma produção de cidade pautada na dominação e no lucro, contra modelo segregacionista legitimado cotidianamente que define o lugar no qual os excluídos devem ficar e reforça o estabelecimento da escassez por meio de discurso amplamente repetido (muitas vezes silenciosamente) por toda a sociedade.

A cultura marginal de periferia denuncia uma cidade distante, apesar de estar “Perto Daqui”. As narrativas marginais colocam-se como instrumento para a democratização do discurso que fala dos espaços opacos, reconfigurando-os simbólica e endogenamente, ressignificando a condição de seus habitantes como cidadãos que, de fato, o são. No grito, reivindicam sua existência para não serem apagados.

E falar de onde eu moro

Dá muita emoção

Pois enquanto eu existir

A favela não vai tá em extinção

(Marquin, Slam Botocudos, 27 de abril de 2017)

3À guisa de conclusão

Este trabalho enfrenta o desafio de ir ao encontro da vida experimentada no interior de uma realidade pouco visível, aproximando-se de manifestações que tentam romper as fronteiras que dividem a cidade e de sujeitos que vivem suas vidas como atos de resistência ao habitá-la e ao narrá-la. As narrativas ocuparam o trabalho convertendo-o num instrumento que versa sobre a vida nos espaços opacos. A voz pouco audível dos sujeitos opacizados, desta forma, ocupa as páginas da produção acadêmica, espaço esse ainda pouco acessível aos territórios periféricos e seus discursos, expondo a lida cotidiana da sua ilegalidade no espaço urbano, participando da construção de uma outra história da cidade, que abarque, também, o ponto de vista dos excluídos, e expanda o conhecimento e o direito sobre a mesma.

Nas fissuras da cidade enquadrada nos limites definidos por políticas socioeconômicas, atuam as táticas daqueles que são impedidos de participar de uma justa partilha de direitos, de serem vistos e de terem suas vozes ouvidas. Com a problematização da cidade a partir da cultura marginal, ou seja, dos territórios invisibilizados e silenciados, busca-se “inverter a bússola para a periferia”, como afirma Sérgio Vaz (BRUM, 2009); colocando o ponto de vista dos vencidos no centro de visibilidade. Escovando a “história a contrapelo” (BENJAMIN, 1985, p. 157), em oposição ao discurso oficial e dominante que oculta aquilo que foge às suas normativas, busca-se discutir o direito sobre a cidade e formular novos contornos na luta por participação e visibilidade. Busca denunciar a marginalização e a exclusão social dos territórios periféricos, defender o direito de uma vida digna na cidade em oposição à segregação socioespacial legitimada por aparelhos legais. Adota-se, portanto, um movimento de inversão da lógica que dita a produção do conhecimento, questionando o lugar dos sujeitos e espaços autorizados, e colocando-se à escuta dos discursos dos marginalizados, criminalizados e condenados à partir de seu território de origem.

O saber acadêmico legitimado, via de regra, se distancia da vida produzida nos territórios obscurecidos. Fala destes sem compreendê-los porque não os experimenta, analisando-os a partir de fora, e desclassificando os saberes produzidos neles, estigmatizando-os sob o signo de “popular”, sem valor científico. O lugar dos territórios marginais no conhecimento científico é, usualmente, o de objeto de estudo; embora nos faltem dados numéricos concretos, podem-se ver multiplicarem as pesquisas que se debruçam sobre esses espaços. A presença da universidade nas periferias é frequente e vem carregada com o peso da instrumentalização do saber, das falas, com pesquisas cujos resultados dificilmente retornam aos sujeitos que as alimentaram.

Do encontro com as narrativas marginalizadas dos territórios opacos desacortinou-se muito mais que um desejo de existência, mas de participação; de ser cidade e fazer parte dela. Em um trabalho de muitas mãos e vozes, pela colaboração buscou-se trazer a superfície um discurso sombreado, que produz conhecimento sobre uma cidade muitas vezes negada a partir de pontos de vistas e experiências outras. Desse encontro reconfiguraram-se arranjos, questionaram-se lugares de poder e fala ocupados e se fez emergirem os saberes produzidos e coparticipados por aqueles impedidos de tomarem parte na partilha de direitos.

A partir do encontro com essas narrativas, falou-se dos territórios obscurecidos na lógica segregacionista estruturante dos espaços urbanos das cidades brasileiras, abordando-se o caso específico da Região Metropolitana da Grande Vitória. Não há conclusão que encerre as questões aqui levantadas ou, muito menos, que esgotem as narrativas encontradas. A narrativa é aberta, permite múltiplas abordagens, traz à tona muitas outras periferias além das que se pode aqui visibilizar.

Referências

BAPTISTA, L. A. S. A fábula do garoto que quanto mais falava sumia sem deixar vestígios: cidade, cotidiano e poder. In: MACIEL, I. M. (Org.). Psicologia e Educação: novos caminhos para a formação. Rio de Janeiro: Ciência Moderna, 2001. p. 195-209.

BENJAMIN, W. Teses sobre filosofia da história. In: KOTHE, F. R. (Org.). Sociologia. São Paulo: Ática, 1985.

BRUM, E. Colecionador de Pedras. Época. 6 Mar. 2009. [online] Disponível em: <http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,ERT63130-15228-63130-3934,00.html>. Acesso em: 18 Out. 2018.

CERTEAU, M. A invenção do cotidiano: 1. Artes de fazer. Trad. Ephraim Ferreira Alves. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014.

DEBORD, G. A sociedade do espetáculo. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 1997.

FERRÉZ. Terrorismo Literário.In: FERRÉZ. A cultura da periferia: Ato II. Revista Caros Amigos, São Paulo, n. 2, p. 2, 2002. Caderno Especial.

FOUCAULT, M. A ordem do discurso. Trad. Laura Fraga de Almeida Sampaio. São Paulo: Loyola, 1996.

JACQUES, P. B. Zonas de tensão: em busca de micro-resistências urbanas. In: JACQUES, P. B.; BRITTO, F. D. (Org.). Corpocidade: debates, ações e articulações.Salvador: EDUFBA, 2010. p. 106-119.

LEFEBVRE, H. O direito à cidade. 5a. ed. São Paulo: Centauro, 2001.

MARICATO, E. As idéias fora do lugar e o lugar fora das idéias. In: ARANTES, O.; VAINER, C.; MARICATO, E. A cidade do pensamento único: desmanchando consensos.Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. (Coleção Zero à Esquerda)

MARICATO, E. Brasil, Cidades. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2001.

MOASSAB, A. Brasil periferia(s): A comunicação insurgente do hip-hop. São Paulo: EDUC, 2011.

PIRES, V. L.; KNOLL, G. F.; CABRAL, É. Dialogismo e polifonia: dos conceitos à análise de um artigo de opinião. In: PIRES, V. L.; KNOLL, G. F.; CABRAL, É. Letras de Hoje, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, v. 51, n. 1, 2016. Disponível em: <http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/fale/article/view/21707>. Acesso em: 23 Out. 2018.

SÁ, C.; VERLI, C. Cerca de 125 mil ainda jogam esgoto no mar de Vitória. G1. 15 mai. 2017. [online] Disponível em: <https://g1.globo.com/espirito-santo/noticia/cerca-de-125-mil-ainda-jogam-esgoto-no-mar-de-vitoria.ghtml>. Acesso em: 23 mai. 2018.

SANTOS, M. A natureza do espaço: técnica e tempo, razão e emoção. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2006.

SANTOS, M. O dinheiro e o território.In: BECKER, B.; SANTOS, M. (Orgs.). Território, Territórios: Ensaios sobre o ordenamento territorial. 3a. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, 2007. p.12-21.

VIEIRA, L. F. D. Vida no Forte São João e a tecedura de políticas: acompanhando a produção de redes. 2012. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia Institucional) – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Vitória, 2012.

1 Conceitos como polifonia e dialogismo podem ser considerados como propriedades constitutivas de todo discurso, estão presentes em qualquer enunciação. Portanto, são basilares para as reflexões sobre relações intersemióticas e formas de expressão intertextuais aqui processadas, que objetivam analisar interações de linguagens e de meios comunicacionais que não se enquadram no monologismo, também entendido como discurso oficial ou hegemônico. Nesse sentido, o pequeno extrato do artigo “Dialogismo e polifonia: dos conceitos à análise de um artigo de opinião” é esclarecedor: “Se o monologismo nos faz perceber que ‘o outro nunca é outra consciência, é mero objeto da consciência de um eu que tudo enforma e comanda’ (BEZERRA, 2007, p. 192); o dialogismo, por sua vez, situa-nos e nos conscientiza que ‘nenhuma significação se instaura, em nenhum evento concreto, sem a presença de, no mínimo, dois centros de valor’ (TEZZA, 2003, p. 232); já a polifonia é a ânsia de um mundo ‘no qual a multiplicidade de vozes plenivalentes e de consciências independentes e não fundíveis tem direito de cidadania – vozes e consciências que circulam e interagem num diálogo infinito’ (FARACO, 2009, p. 77)” (PIRES; KNOLL; CABRAL, 2016).

2 O geógrafo Milton Santos (2006) usa a ideia de áreas opacas em oposição às áreas luminosas da cidade. As áreas luminosas seriam os espaços racionados e racionalizadores, organizados e dotados de densidade técnica e informacional. As áreas opacas, por sua vez, seriam aquelas onde essas características estariam ausentes, mais aproximados com espaços de afetividade, criatividade. Lançamos mão das mesmas adjetivações para, metaforicamente, denominar os discursos como luminosos e opacos, segundo sua proveniência e de seus enunciadores. Cabe destacar, ainda, que utilizamos diversas denominações como zonas, áreas ou espaços para essas adjetivações sem preocupação em diferenciar essas categorias.

3 Falar em periferia neste trabalho é referir-se aos espaços marginalizados, excluídos da cidade, não necessariamente em uma periferia física. A marginalização que os territórios opacos e sua população são submetidos é muitas vezes assumida e ressignificada para a criação do novo, do próprio, de autêntico, sob esse signo.

4 Terminologia apresentada por Ferréz no lançamento de seu livro Capão Pecado (2000) é definida pelo autor como “uma literatura feita pelas minorias, sejam elas raciais ou socioeconômicas. Literatura feita à margem dos núcleos centrais do saber e da grande cultura nacional, ou seja, os de grande poder aquisitivo” (FERRÉZ, 2002, s.p.).

5 Os trechos narrativos transcritos estão identificados pelo evento em que foram enunciados. Não há a identificação dos participantes conforme assegura as normativas da Resolução CNS 510/2016 acerca de pesquisas em Ciências Humanas e Sociais. É garantido, porém, aos autores o direito autoral sobre as rimas e poesias, estando expostas em algumas poesias a pedido dos mesmos.

6 Matéria de 15 de maio de 2017. Disponível em: <https://g1.globo.com/espirito-santo/noticia/cerca-de-125-mil-ainda-jogam-esgoto-no-mar-de-vitoria.ghtml>. Acesso em 23 Mai. 2018.

The city and narratives: speech and the right to the city in opaque spaces

Anna Paula Ferraz Dias Vieira is architect, Master in Architecture and Urbanism. She studies the right to the city, marginal culture, fight for visibility.

Milton Esteves Junior is architect, Doctor in Architecture History, City History. Associate Professor, Federal University of Espírito Santo. Coordinator of the Research Groups Vix Connection and [Con]textos Urbanos. He studies perception, cognition and production of the territory, urban planning and quality of the built environment, human settlements and quality of life.

How to quote this text: Vieira, A. P. F. D. and Esteves Junior, M., 2018. The city and narratives: speech and the right to the city in opaque spaces. V!RUS, Sao Carlos, 17. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus17/?sec=4&item=5&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 28, 2018

Abstract:

The divided city territorializes inequalities, legitimized by a hegemonic discourse that serves the dominant ideas and values. From its physically and socially fragmented spaces it chooses those to illuminate, to show as the image of the city of spectacle, and those which will be cast to the shadows and will be invisible. By mitigating subjectivities and rejecting deviant behavior and discourses, it builds, shapes and frames the city it wants to be and be seen. At the limits where the visibility ceases, the city is, however, in continuous production. The shadow that covers the marginalized territories also reveals them, since their practices escape the comprehension of the totalizing gaze. Through the marginal culture, underprivileged areas spread their shadow over the illuminated areas of the city, painting it with its subjectivity, giving it new meanings, disputing its spaces and speeches. From the peripheral territories emanate other narratives of the city and feelings of collaboration arise between partners in similar situations and opinions, aiming to conquer spaces in favour of the citizen participation. Under theoretical contributions of Michel de Certeau and Milton Santos, mainly, we aim to discuss the unequal distribution of the right to speech and visibility, and highlight the "ways of making" of the "opaque spaces", which dispute the city through its narratives, allowing new gazes over it, and other stories to be told that expand the right to the city. Here we defend the right to speech as a right to the city, translated into effective struggles for the deconstruction of social stigmas.

Keywords: Opaque spaces, Narrative, Marginal culture, Right to the city

1Introduction

The city ruled by the productivist economic and social logic is in dispute. Its urban configuration has resulted from processes historically marked by inequality of rights and by socio-spatial segregation. We understand the concept of territorial configurations as the materialization of functions, uses and usages made in the territory, a meaning that includes both the space-materiality and the actions of the subjects that installs themselves on it and that refers to them. We deal here with socio-spatial phenomena converted into territories and experiential territorialities, as well as narratives designed to express them and make us reflect on them. We are dealing, therefore, with formulations and polyphonic and plurigenic phenomena that involve and demand polyphonic and dialogic readings1. The quantity and complexity involved in the understanding and expression of these questions require a cleavage, here established in the selection of narratives that counterpose to the hegemonic discourse, which is based on the asymmetric distribution of the right to enunciation to ratify the apparatus producing nefarious situations such as the already cited inequality and socio-spatial segregation.

In spite of the multiplicity of ways and means by which the city expresses itself and by which it can be read, felt and interpreted, it is perennial the attempt to impose a brand through a discourse that contains, synthesizes and unifies its identity. It creates an image of what the official discourse wishes to show, constructs an idea of territory from a consensus that shadows and invisibilizes what diverges from such an image, which suppresses what may presuppose dissent. That is, this search for an identity image of the city promotes a discourse that values the harmonic and the consensual and suppresses the divergent, the diverse, the conflictual, the dissonant (Pallombini cited in Vieira, 2012).

The ways of seeing, experiencing and narrating the city do not admit consensus, because they are part of processes of subjectivation (individual or collective) that vary with each experience. The city is not a homogeneous and indivisible whole; it is composed of multiple and distinct social and cultural components; therefore, it becomes equally plural and diverse in each of its parts. The hegemonic discursive conception of the city derives from a discourse that echoes and spreads an image of the city that, in most cases, goes against other narratives that want to be seen. Other narratives composed of experiences, bodies and lives that are also part of the city and that speak of it, but which, due to the hegemony of the dominant discourse, are obscured and de-legitimized, either by the non-recognition of their scientific nature or by the sociocultural factors of their announcers (gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic levels, etc.), or by their territory of origin. The hegemonic discourse cancels out what it cannot control, stealing its movements, its ginga2 and its abilities, limiting its intensities, framing its tactics and painting its bright colors of gray. Enunciated by previously defined speakers, invalidates the other voices and narratives to define the course of history and the ways in which it must be told. It chooses the voices from which emanates all knowledge and all consciousness, albeit in an illusory and false way (Debord, 1997).

At the thresholds of visibility, after the hard and luminous borders that divide the city - center-periphery, asphalt-hill, formal-informal-, there is an incessant production that causes strangeness to the totalizing gaze (Certeau, 2014). From the opaque areas3, among the socially, economically, culturally and geographically marginalized, other discourses about the city emanate, which are often obscured or silenced when considered as "irrational for hegemonic uses" (Santos, 2006, p.210, our translation). The opaque zones are so because there is no light on them, because they are not allowed to appear, nor that their manifestations of resistance reach the surface. Over these spaces, the eye acts predominantly in an instrumentalized way.

These "impossible to manage" spaces (Certeau, 2014) are the ones that suffer the most from the violence of the imposition of limits in the hard attempt to give them an identity. The movements to make the opaque spaces invisible occur not only by their negation, by the erasure of what is deviation, but also by the imposition of a stereotype. Opaque spaces, identified as territories of poverty, are usually linked to situations of violence, exclusion and privation (Vieira, 2012). The emphasis on these negative aspects, resulting from a system anchored in inequality, generates a distance from the opaque areas of the city, deepening the boundaries that divide it and clouding what is produced in it that is different to what one expects to find there.

Misery and scarcity are part of the daily life of opaque spaces, but solidarity, readiness and resistance are also marks of these territories of creativity. Culture is produced abundantly in the peripheries4, but it is the authorizing voices that come from outside them, not from within, that legitimize or criminalize them. Attempts to make opaque areas invisible do not occur without movements of resistance from them, not reactive, but intrinsic to the process of spectacularization. It is within this process that criticism, in the form of deviations and fissures, occurs as microrresistences (Jacques, 2010, p.109). From the peripheral territories emanate other narratives of the city, which dispute their spaces and their speeches, and provoke feelings of collaboration between partners in similar situations and with similar opinions aiming to conquer spaces in favor of citizen participation.

In the opaque areas of the city, tactical actions are witnessed, both in their ways of inhabiting the peripheral or marginalized portions of the city - ways of building, adapting, changing geography and habitat - and of circulating in the city, transposing imposed boundaries and occupying spaces and speeches. The peripheral culture, in its various forms of manifestation - marginal literature, saraus (open mic events), slams, samba, funk, rap, hip hop, graffiti... - acts as microrresistencies to the processes of silencing imposed on the periphery and occupies radios, squares, sidewalks, stairs and walls. In this way, it reveals the dissent, stresses the urban space by disputing it and distorting the existing power relations, making the space spectacularized by the discourse political again: "urban life presupposes encounters, confrontations of differences, knowledge and reciprocal acknowledgments (including ideological and political confrontation) of ways of living" (Lefebvre, 2001, p.22, our translation).

The narrative of marginal culture seeks to destroy the foundation that legitimizes the official discourse for the circulation of ideas, seeks to overthrow the hierarchies that define those who have competence to speak and be heard. The discourse "is not simply what translates struggles or systems of domination, but that by what we struggle, the power we want to seize" (Foucault, 1996, p.10, our translation). Peripheral marginal culture claims its place as a narrator, making the marginalized people aware that they can say beyond what is authorized to them; it does so by questioning the authority of the one who speaks for another, to whom it delegates its voice and ends up seeing itself reduced and rationalized. Marginal culture emerges as a tool for the empowerment of peripheral areas, treating its multiple versions of history as a means of survival of these opacified spaces (Baptista, 2001). In general it thematizes the life in the periphery, claiming the right to a voice and the construction of the knowledge by those who do not inhabit the places of speech.

The peripheral spaces, which, under a hegemonic prism, would be identified by stigmas of violence, misery and privation, in possession of their place as the narrator are re-signified and valued: revealing their intense cultural production; exposing the ginga with which their bodies move in the formal city and in the quebradas5;stating their ability to speak about the daily life through subjective experiences; reporting on their individual struggles and their processes, but also on the solidarity among their residents; denouncing and confronting violence that results from inequality, as well as from devices of capture, surveillance and control.

From the study of marginal narratives, we intend to debate about the right to the city and the discursive instruments about life in it. Starting from the hypothesis of the dispute for the city and the right of speaking about and in it, the study was allowed to be guided by the narratives that emanate of the peripheral culture as a way of understanding the city no longer from a totalizer glaze, but from another point of view, which tells a different story, and which collaborates on and broadens the production of knowledge about the city and its understanding.

The discourse of the peaceful and harmonious city tries to make invisible both geographical portions of urban space, as well as its population, its productions and struggles. Milton Santos (2007) enlarges the concept of territory beyond what is summed up in physical space, expanding it to the place where actions, passions, powers, strengths, weaknesses occur, that is, corresponds to space where man manifests himself and builds his existence. Therefore, we talk of obscure territories. From the attempt to conceal and erase spaces, as well as the ways of life they shelter, their struggles, their challenges, their creations, the violence to which they are subjected, that is, everything that escapes and diverges from the discourse that affirms to know everything about city and poverty (Vieira, 2012).

There is an intense production of culture and narratives in obscured territories that, although invisible and silenced, act by destabilizing the place of mere object imposed on them, producing the city itself and also knowledge about it. The asymmetric distribution of the right to the city in space and speech justifies the need to access life in opaque territories from the optics and narratives of its residents.

2The narrative of the city and the right to it through the opaque spaces point of view

The Greater Vitória Metropolitan Area (GVMA) has witnessed a great growth of the movements related to the marginal culture. Driven by the hip-hop movement, it is possible to see the flourishing of numerous collectives that organize themselves around the production of literature, music, rhyme, dance, graffiti, etc. There is also a growing number of meetings generated by these movements, which occupy the public and institutional spaces every day of the week with saraus, slams, rap and break battles, to name a few.

In the attempt to find silenced narratives about the city, we sought the peripheral literary movement, already known from other places in Brazil, in its manifestations in the GVMA. The encounter with marginal literature6, driven by the discomfort with the silencing of peripheral territories and life that does not fit the image imposed by the official discourse of the formal city, triggered a series of connections and entrances towards the narratives produced by the population of these same territories. Literatura MarginalES, a collective composed by young writers of the Greater Vitória, was the first access to the groups dedicated to the marginal literature produced in the region. Soon several other connections were established, and from this entanglement a network of distinct movements was formed, but which converged both in their content and in their actors, and supported the will to speak of silenced territories and lives. The meeting with this first marginal literature collective paved the way for a series of other meetings with groups practicing the written word and orality of the saraus, slams, and hip hop battles.

These groups do not speak of specific localities or districts, but speak generally about opaque areas. The origin of the members of these groups and the participants in the events and battles are multiple, they are residents of different neighborhoods of the several municipalities of the GVMA, but the main content of the speeches tends to be the same: the ways of life of the peripheral areas, the denunciation of the lack of rights to participation and the desire for visibility, the desire for enunciation. We sought to access, through marginal literature, saraus and hip hop, dissonant narratives from opaque spaces that revealed other ways of being and living in the city, as ways of resistance to invisibility and silence. Not only descriptive accounts, but the very experience of trying to participate in the production of space and urban life. We participated in a large number of marginal culture events and meetings that celebrated narrative orality, recording their speeches and poetic productions in a tone of struggle, outburst, denunciation and celebration, as well as collecting the graphic productions (fanzines, books) of marginal literature, seeking, in this way, to access other narratives that have been constructed and, also, obscured about the city7.

The place of residence of individuals plays a determining role for the full exercise of citizenship, allowing or not access to public services and life with urbanity. The urban developmentalist model excluded the lower income groups from participation in the country's advances. It is a development model that institutionalized socio-spatial segregation, through which an urban space is produced that not only reflects inequalities, but also reaffirms and reproduces them (Maricato, 2002). Socio-spatial segregation generates and reaffirms social exclusion, reserving to the population of the poorest spaces a precarious insertion in the city, even when spatially included in it, as reported in this poem:

Here is Far Far Away

In Far Far Away

There was a slum called Near Here

There was everything in Far Far Away

Health, education, leisure

Art and culture for the brothers

But in Near Here

There was no health, no leisure, no education

There was a lot of Police approach, shooting and exploring

Lack of rice, lack of beans8

Here is Far Far Away

And Far Far Away is near here.

(Slam Botocudos, April 27, 2017)

This poem, recited in a poetic battle of Slam Botocudos, a marginal culture event in Greater Vitória, shows the dimension of what it is to live and survive in the urban spaces reserved for the poor. The fragments of a multiple and segregated city, capable of touching each other due to spatial proximity, are separated by the hard border of the practice of power, where such diverse realities are confronted in such a way that the disadvantage of one translates into the advantage of the other. In the poem, "Far Far Away" and "Near Here" reveal the geographic space of the city. The quality of life sought by the periphery - which includes access to health, education, leisure, culture, food and security - is very distant despite being enjoyed right next to it. This narrative portrays the segregationist model of Brazilian cities, often denounced by those who live illegally due to socio-spatial exclusion.

This illegality becomes functional, since it supports archaic political relations, exchanges of favors and clientelism, aiming real estate speculation and arbitrary application of the law (Maricato, 2002). The narrative also denounces the violence suffered daily in the peripheries, by the oppressive presence of the State or by its indifference to the real civil war that happens in our cities; reveals a nonconformity regarding the unequal treatment directed at the different urban spaces, as in the poetic sections below:

We are sentenced and it isn’t even in the judiciary

This is the echo of the culverts that invades the noble neighborhood

Unfortunately the shock troops don’t go there also

They are only made for going up the hill

Killing bad guys who are poor

Enquadrando9 the residents

Pretending they will seize guns

"Raise your hands! Look at the wall! "

(Gnom, Sarau Emprete-Sendo, May 30, 2017,our translation)

An ordinary man

Comites a small crime

And stays in jail until he becomes a carcass

A suit-and-tied man steals a nation

And the biggest punishment is getting stuck inside his own house

(Project Boca Boca, May 12, 2017, our translation)

The above poems show the different approaches relative and proportional to socio-spatial inequality, either in the way the security force appears or in the punishment instruments that it presupposes. The police are thus configured as a tool for maintaining socio-spatial segregation, which is necessary for the processes of domination through the differential treatment that it grants to the different social strata (Moassab, 2011). Fear for some, security for others, the police represents an instrument of social control of the State against the class of "born criminals", meaning: slums residents, poor, black people. The revelation of the violent treatment of the police comes with a critique of the type of urbanization carried out in obscured territories. For this population only the defense through the possible denunciations remains.

And they filled the slums with squares

Just to make the violent enquadroeasier

And any preppy can’t speak about the slums

Because they don’t live with death by their side

(Sarau Emprete-Sendo, June 20, 2017)

The presence of the State in these territories is precarious and inefficient. On many occasions, the lack of sanitation in the territories of poverty is mentioned, highlighting the difficulty of access to treated water and sewerage:

And I'm thirsty

But not of blood anymore

Not of blood anymore

Only of drinking water

That never got to the top of the hill

(Sarau Emprete-Sendo, May 30, 2017)

Here there is no wealth, but there is the beauty of being happy.

Happy happy

Here we make the banquet from the crumbs that the State provides to be happy

Unhappy

Unpaved street

Hill

Open sewage

(Slam Botocudos / Sarau Emprete-Sendo, Casa da Barão, Centro, Vitoria, July 27, 2017)

According to Cesan (Espírito Santo Sanitation Company), in 2016 the city of Vitória had 88.7% coverage of the sewerage, with approximately 69.6% of the capital's population connected to the system10. Although Vitória presents the best sanitation situation among the municipalities of the Metropolitan Region, it is still far from ideal. Among the regions not served by the sewerage system of the capital, 32 out of 79 are located in the hills and neighborhoods of the periphery, mostly in the northwest bay, as shown in the image below, of a journalistic survey, and as reported by the peripheral narratives. The map presented below (Figures 1), shows the coverage of the sewerage system and the wastewater disposal sites in the city of Vitória subdivided into neighborhoods; In Figure 2, which highlights the topography of the city, it is noted that the districts not served or served precariously by the aforementioned sewerage system, are mainly in the hills and peripheral districts.

Fig. 1: Map of Vitória indicating áreas uncovered by the sewerage system and the disposal sites of this sewage on the seashore of the capital of Espírito Santo. Source: Sá and Verli, 2017, n.p.

Fig. 2: Topographic Altimetric Map of Vitória. Source: Personal Collection (developed from data base of the City Hall of Vitória, ES).

The regions where access to basic sanitation and water services are more precarious, as can be seen in the maps, are also the areas where the population with the lowest income is located and where there is the highest concentration of the black and brown people in the capital. The following maps (Figures 3 and 4) demonstrate the uneven socio-spatial distribution of the city of Vitória, based on the segregation and concentration of theland of the upper-class strata, leaving the poor, black and excluded to settle in irregular areas, with difficult access, in need of infrastructure and the presence of the State.

Fig. 3: Average Monthly Nominal Income by District of Vitória 2010. Source: Vitoria City Hall, 2010.

Fig. 4: Participation of the Black and Brown Population in the Total of Inhabitants by District of Vitória 2010. Source: City Hall of Vitória, 2010.

Life in these spaces is narrated in marginal poetry and in raps, which portray the battle for everyday survival as well as relationships within the communities. They are about the struggle to exist in the unequal city, in the spaces hidden by the political instruments and their ideological speeches, which hold the domain of the urban space.

The discursive and symbolic construction of what is "city" and "periphery" makes citizenship a privilege and not a right, covering the real city with the city that is desired to be seen (Maricato, 2001). Based on the harmonically forged idea of city, the periphery is seen only as the place of violence, crime, lack of resources, infrastructure and culture, and thus constitutes a non-city within the city (Moassab, 2011) .

The image of the peaceful and democratic city hides the segregationist and excluding processes that constitute the urban, as well as the conflicts provoked by inequality. The deconstruction of this biased image is fundamental to the search for a less unequal urban space. In this sense, the marginal narratives of the literature, the rap and the art of the periphery play an important role in exposing the historical process of exclusion, as well as for the re-signification of the city. The artistic manifestations raise an intense debate about the deep social and urban inequalities of the periphery, searching for ways to reverse this picture.

For I write lyrics that portray our reality

From social disregard to criminality

Acting in places where nobody, nobody

Nobody wants to come in

(Sarau Quebrando o Silêncio (Breaking the Silence), September 19, 2017)

In this way, battles are fought for the deconstruction of the pejorative symbolic burden that has always weighed on the inhabitants of the poor regions; as well as for the recognition of their cultural manifestations and the knowledge produced by them, from an internal legitimization. In order to face the consequences of historical spatial segregation (such as violence and precarious infrastructure already mentioned), what is seen in the peripheral areas is an intense relationship of cooperativity and responsibility with each other, reinforcing the importance of such networks of collaboration and participation; what we see is a diversified and growing cultural production accompanied by entrepreneurial initiatives. That is, it is a periphery that is very different from the image that the hegemonic discourse tries to frame. As in the narrated sections below:

There, the collective is of neighbors filling the slab11

And, as Gaspar said, people "who have color acts"

(Extract from the song #VocêsFizeramDissCriminação (#YouHaveDisCriminated) by Diego Cavaleiro Andante, our translation)

The marginal narratives operate against the instruments of domination, symbolically reformulating the peripheries. They quarrel the city in its spaces; occupy the city through their speech. Battle against a production of a city based on domination and profit, against a segregationist model legitimized daily that defines the place in which the excluded should stay and reinforces the establishment of scarcity through a discourse widely repeated (often silently) throughout the society.

The peripheral marginal culture denounces a distant city, although it is "Near Here". The marginal narratives are used as instruments for the democratization of the speech that speaks of the opaque spaces, reconfiguring them symbolically and endogenously, resignifying the condition of its inhabitants as citizens who, in fact, they are. Shouting, they claim their existence so they will not be erased.

Talking about where I live

Stir a lot of emotions

For while I exist

The slum won’t become extinct

(Marquin, Slam Botocudos, April 27, 2017, our translation)

3By the way of conclusion

This work faces the challenge of meeting the life experienced within a barely visible reality, approaching manifestations that try to break the boundaries that divide the city and of subjects who live their lives as acts of resistance by inhabiting and narrating it. The narratives occupied the work by converting it into an instrument that talks about life in opaque spaces. The little audible voice of the opacified subjects thus occupies the pages of academic production, a space still not very accessible to the peripheral territories and their speeches, exposing the daily life of their illegality in the urban space, participating in the construction of another history of the city, which also embraces the point of view of the excluded, and expands the knowledge and the right to it.

In the fissures of the city within the limits defined by socioeconomic policies, takes place the tactics of those who are prevented from participating in a fair sharing of rights, of being seen and having their voices heard. Through the problematization of the city from the marginal culture, that is, from the invisibilized and silenced territories, we try to "turn the compass to the periphery", as Sergio Vaz (Brum, 2009, our translation) states; putting the point of view of the losers in the center of visibility. Brushing "history against the grain" (Benjamin, 1985, p.157, our translation), and in opposition to the official and dominant discourse that hides what is not in line with its norms, we seek to discuss the right to the city and formulate new outlines in the struggle for participation and visibility. It seeks to denounce the marginalization and social exclusion of peripheral territories, to defend the right to a dignified life in the city as opposed to socio-spatial segregation legitimized by legal apparatus. Therefore, a movement of inversion of the logic that dictates the production of knowledge is adopted, questioning the place of the subjects and authorized spaces, and listening to the speeches of the marginalized, criminalized and condemned from their territory of origin.

Legitimized academic knowledge, as a rule, distances itself from the life produced in obscure territories. It speaks of them without understanding them because it does not experiment them, analyzing them from the outside, and disqualifying the knowledge produced in them, stigmatizing them under the sign of "popular", without scientific value. The place of marginal territories in scientific knowledge is usually of object of study; although we lack concrete numerical data, it is possible to see that the researches that investigate these spaces multiply. The presence of the university in the peripheries is frequent and comes loaded with the weight of the instrumentalization of knowledge, of speeches, of researches of which results hardly return to the subjects who supplied them.

From the encounter with the marginalized narratives of the opaque territories, there was discovered much more than a desire for existence, but for participation; to be part of the city. In a work of many hands and voices, through collaboration was sought to bring to the surface a shaded speech, which produces knowledge about a city often denied from other views and experiences. From this encounter new arrangements were formed, places of power and speech were questioned and knowledge produced and shared by those prevented from taking part in the sharing of rights emerged.

In the encounter with those narratives, we spoke of the territories that are obscured in the segregationist logic that structures the urban spaces of Brazilian cities, addressing the specific case of the Metropolitan Region of Greater Vitória. There is no conclusion that closes the questions raised here, or, much less, ends the narratives found. The narrative is open, allows multiple approaches, brings up many other peripheries beyond those that can be seen here.

References

Baptista, L. A. S., 2001. A fábula do garoto que quanto mais falava sumia sem deixar vestígios: cidade, cotidiano e poder. In: I. M. Maciel org., 2001. Psicologia e Educação: novos caminhos para a formação. Rio de Janeiro: Ciência Moderna. pp.195-209.

Benjamin, W., 1985. Teses sobre filosofia da história. In: F. R. Kothe org., 1985. Sociologia. São Paulo: Ática.

Brum, E., 2009. Colecionador de Pedras. Época. 6th March. [online] Available at: <http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,ERT63130-15228-63130-3934,00.htm > [Accessed 18 October 2018].

Certeau, M., 2014. A invenção do cotidiano: 1. Artes de fazer. Translated by Ephraim Ferreira Alves. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Debord, G., 1997. A sociedade do espetáculo. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto.

Ferréz, 2002. Terrorismo Literário. In: A cultura da periferia: Ato II. Revista Caros Amigos, 2, p.2. Caderno Especial.

Foucault, M., 1996. A ordem do discurso.Translated by Laura Fraga de Almeida Sampaio. São Paulo: Loyola.

Jacques, P. B., 2010. Zonas de tensão: em busca de micro-resistências urbanas. In: P. B. Jacques and F. D. Britto org. Corpocidade: debates, ações e articulações. Salvador: EDUFBA, pp.106-119.

Lefebvre, H., 2001. O direito à cidade. 5th ed. São Paulo: Centauro.

Maricato, E., 2002. As idéias fora do lugar e o lugar fora das idéias. In: O. Arantes, O., C. Vainer and E. Maricato, 2002. A cidade do pensamento único: desmanchando consensos. Petrópolis: Vozes. (Coleção Zero à Esquerda)

Maricato, E., 2001. Brasil, Cidades. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Moassab, A., 2011. Brasil periferia(s): a comunicação insurgente do hip-hop. São Paulo: EDUC.

Pires, V. L., Knoll, G. F. and Cabral, É., 2016. Dialogismo e polifonia: dos conceitos à análise de um artigo de opinião. Letras de Hoje, 51(1). Available at: <http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/fale/article/view/21707> [Accessed 23 October 2018].

Sá, C. and Verli, C., 2017. Cerca de 125 mil ainda jogam esgoto no mar de Vitória. G1. 15 May. [online] Available at: <https://g1.globo.com/espirito-santo/noticia/cerca-de-125-mil-ainda-jogam-esgoto-no-mar-de-vitoria.ghtml> [Accessed 23 May 2018].

Santos, M., 2006. A natureza do espaço: técnica e tempo, razão e emoção. São Paulo: Hucitec.

Santos, M., 2007. O dinheiro e o território.In: B. Becker and M. Santos orgs. Território, Territórios: Ensaios sobre o ordenamento territorial. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, pp.12-21.

Vieira, L. F. D., 2012. Vida no Forte São João e a tecedura de políticas: acompanhando a produção de redes.Master’s degree. Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo.

1 Concepts such as polyphony and dialogism can be considered as constitutive properties of all speech, are present in any enunciation. Therefore, they are basic for the reflections on intersemiotic relations and intertextual forms of expression here processed, that aim to analyze interactions of languages and of communication means that do not fit into the monologism, also understood as official or hegemonic discourse. In this sense, the brief extract from the article "Dialogism and polyphony: from concepts to analysis of an article of opinion" is illuminating: "If monologism makes us realize that 'the other is never another consciousness, it is merely an object of self-consciousness that informs and commands everything' (Bezerra, 2007, p.192); the dialogism, on the other hand, situates us and makes us aware that 'no significance is established, in any concrete event, without the presence of at least two centers of value' (Tezza, 2003, p.232); polyphony, tough, is the eagerness of a world 'in which the multiplicity of plenary voices and of independent and unfundible consciousness has the right of citizenship - voices and consciousness that circulate and interact in an infinite dialogue' (Faraco, 2009, p.77) (Pires, Knoll and Cabral, 2016, our translation).

Ginga is the denomination given to the basic movement of capoeira: when fighters protect themselves, diverting from the rival’s attack, creating new counterattack directions. The ginga applied to life is a "creative ability, attention to the lurking of fissures that enable life to go beyond the determinations that imprison their existences" (Vieira, 2012, p.18, our translation).

3 Geographer Milton Santos (2006) uses the idea of opaque areas in opposition to the luminous areas of the city. The luminous areas would be rationed and rationalized spaces, organized and endowed with technical and informational density. The opaque areas, on the other hand, would be those where these characteristics would be absent, closer to spaces of affection, creativity. We use the same adjectives to metaphorically denominate speeches as luminous and opaque according to their origin and their enunciators. It should also be noted that we use different denominations as zones, areas or spaces for these adjectives without concern to differentiate these categories.

4 To speak of periphery in this work is to refer to the marginalized spaces, excluded from the city, not necessarily in a physical periphery. The marginalization that the opaque territories and their population are subjected to is often assumed and re-signified for the creation of what is new, proper, authentic, under that sign.

5 Quebrada is how it is popularly called the peripheral and marginalized districts of the city, i.e., the slums or skid rows.

6 Terminology presented by Ferréz in the launching of his book Capão Pecado (2000) is defined by the author as "a literature made by minorities, be they racial or socioeconomic. It is a literature made at the margin of the central points of knowledge and of the great national culture, that is, those of great purchasing power" (Ferréz, 2002, s.p., our translation).

7 The transcribed narrative passages are identified by the event in which they were uttered. There is no identification of the participants as it ensures the norms of Resolution CNS 510/2016 about researches in Human and Social Sciences in Brazil. However, the authors have guaranteed copyright over the rhymes and poems, so it is being exposed in some poetry at their request.

8 Rice and beans correspond to the daily basic nutrition of the majority of the Brazilian population. The expression used in poetry therefore talks about the lack of food.

9 Slang that means the police’s approach actions, sometimes along with physical or verbal abuse, treating the suspect as a criminal. Verbal inflection of enquadrar verb.Other forms in this paper: enquadro (substantive).

10 Article from May 15, 2017. Available at: <https://g1.globo.com/espirito-santo/noticia/cerca-de-125-mil-ainda-jogam-esgoto-no-mar-de-vitoria .ghtm> [Accessed 23 May 2018].

11 That expression refers to the autoconstruction currently made in the brazilian slums. It is very common to reunite a group of neighbors to construct a new house or refurbish a neighbor’s house.