Topoheterocronías: modelos analógicos para la visualización del tiempo

Rodrigo Martin Iglesias es arquitecto y Doctor en Diseño. Profesor Titular de Historia de la Arquitectura (UBA) y de Historia y Crítica de la Arquitectura (UNLaM). Director de la Maestría binacional Open Design (UBA - Universidad Humboldt de Berlín). Coordinador del Laboratorio de Investigación en Diseño (FADU). Studia fabricación digital, procesos productivos y morfogenéticos, Semiotics of sketching.

Marcelo Javier Robles es arquitecto. Profesor de Historia de la Arquitectura (UBA) y Jefe de Trabajos Prácticos de Historia y Crítica (UNLaM). Director del proyecto de investigación "Topoheterocronías: Modelos analógicos para la visualización del tiempo" (FADU-UBA). Socio fundador del estudio ÁGORA Arquitectura.

Como citar esse texto: MARTIN IGLESIAS, R.; ROBLES, M. Topoheterocronías: modelos analógicos para la visualización del tiempo. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 15, 2017. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=4&item=2&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 10 Jul. 2025.

Resumen

Presentamos los fundamentos de un proyecto de investigación que se encuentra actualmente en desarrollo. Este proyecto busca explorar nuevas dimensiones y configuraciones de un Tiempo tradicionalmente unidimensional. Inicialmente hemos sistematizado el material producido desde 2005 con los estudiantes de Historia de la Arquitectura en relación con los Mapas de Tiempo analógicos (multidimensionales), mientras buscamos herramientas teóricas que permitan su interpretación. Hemos caracterizado diferentes tiempos y duraciones, desde aspectos fenomenológicos de la construcción y percepción temporal, hasta fenómenos históricos y naturales de larga duración. Finalmente, exploramos las herramientas de visualización analógicas y digitales para comprender la complejidad intrínseca del Tiempo y sus modelos.

Palavras Clave: Visualización, Tiempo, Mapas de tiempo, Modelos analógicos, Topoheterochronías

1 Introducción

Presentamos aquí las bases y resultados parciales de un proyecto de investigación que se encuentra en desarrollo actualmente. El referido proyecto pretende explorar nuevas dimensiones y configuraciones de un tiempo tradicionalmente unidimensional y lineal. En la etapa inicial se ha pretendido sistematizar el material producido durante más de ocho años con los alumnos de Historia de la Arquitectura en relación a los Mapas de tiempo multidimensionales y encontrar o diseñar instrumentos teóricos para interpretarlos. A tal fin se ha propuesto, por un lado, la investigación y caracterización de los diferentes Tiempos y Duraciones, desde los aspectos fenoménicos de la percepción y construcción temporal, a los fenómenos históricos y naturales de larga duración. Por otro lado, se ha buscado encontrar y diseñar herramientas de representación y visualización que ayuden a la comprensión de los fenómenos anteriormente citados en su intrínseca complejidad. Asimismo, se encuadra el trabajo en una línea de exploración de nuevos instrumentos pedagógicos en la enseñanza dentro del marco de la didáctica constructivista, además de una intrínseca reflexión crítica sobre las herramientas tradicionales y sus conceptualizaciones, tema sobre el que ya hemos hablado en eventos científicos anteriores (Martin Iglesias, 2008, 2010, 2012, Robles, 2014, 2016). Cabe citar como ejemplo ilustrativo la problemática inicial que se plantea en el momento de enfrentarse con la práctica del taller: la evaluación y el adecuado uso de los conocimientos previos del alumno, momento crucial del proceso educativo, al que no se le presta la debida atención. Decimos crucial porque se sitúa como instancia anterior a la propia práctica desde el punto de vista del diagnóstico del estado en el que se encuentran los alumnos respecto de tales conocimientos. La conciencia en el uso de estos preconceptos y aprendizajes previos, por parte del docente, es lo que propicia que el aprendizaje sea una actividad significativa, en particular cuando se trata de la relación entre el conocimiento nuevo y el que el alumno ya posee como precondición de la comprensión.

2 Topoheterocronías

Se toma como punto de partida la trasgresión crítica de la clásica línea de tiempo, como representación gráfica de una secuencia de eventos, que obviamente contiene en sí una idea/concepto de cronología directamente relacionada con un paradigma cultural que nos lleva a asociar la antecedencia a la causalidad y que oculta una metafísica teleológica del tiempo histórico. Esto aparece evidentemente tanto en nuestras agendas o calendarios, como en los discursos más elaborados sobre fenómenos históricos y los relatos que generalmente son construidos a su alrededor. Al mismo tiempo, las representaciones tradicionales no incluyen todos los eventos, sino solamente aquellos que se consideran relevantes desde determinado punto de vista, en general en relación a los cambios o repercusiones que estos supuestamente generan a posteriori. Lo cual confirma la existencia de una lógica causalista y demuestra hasta que punto este tipo de construcciones son producto de una subjetividad cultural e ideológica que finalmente establece las conexiones de eventos y consecuencias de manera tautológica.

Más allá de que la existencia de esta concepción del tiempo también pertenece a la historia y puede realizarse una arqueología de su constitución como dispositivo cultural, también es interesante resaltar que al interior del paradigma se han producido múltiples exploraciones alternativas que van desde la representación de las digresiones narrativas como caminos no lineales en el Tristram Shandy de Laurence Sterne alrededor de 1760, pasando por las Ucronías contrafactuales de Charles Renouvier, a los argumentos de Henri Bergson a fines del siglo XIX por una distinción entre la concepción matemática y homogénea del tiempo y la experiencia heterogénea de la duración, la cual obviamente resulta imposible de representar en el modelo lineal.

3 Temporalidades: Tiempos Hegemónicos y Alternativos

“¿Qué es, entonces, el tiempo? Si nadie me lo pregunta, lo sé; si quiero explicárselo a quien me lo pregunta, no lo sé. Sin embargo, con toda seguridad afirmo saber que, si nada pasase, no habría tiempo pasado, y que si nada sobreviniese, no habría tiempo futuro, y que si nada hubiese, no habría tiempo presente”. Esta frase, extraída de las Confesiones de San Agustín (2010), nos muestra de qué modo el tiempo es algo doble, intensamente ambiguo, algo que no podemos explicar, pero que sin embargo existe como una certeza para nuestra conciencia.

Existen múltiples representaciones mentales del tiempo, relacionadas profundamente con las percepciones que tenemos de él y con las conceptualizaciones que hacemos a partir de las mismas, estas representaciones están imbricadas con patrones culturales que configuramos y nos configuran. Desde que nacemos nuestras experiencias con el tiempo aparecen mediadas por una serie de convenciones sociales, pautas culturales y patrones de actuación, que tienen por función regular su uso y que el mismo sea común a un colectivo determinado. En palabras de Jeremy Rifkin: “Cada cultura posee su propio y único conjunto de huellas digitales temporales. Conocer a un pueblo equivale a conocer los valores del tiempo que han adoptado para vivir. Para conocernos a nosotros mismos, la razón por la que influimos unos sobre otros y sobre el mundo de la manera en que lo hacemos, debemos comprender en primer lugar la dinámica temporal que rige el tránsito humano en la historia” (Rifkin, 2004). Estas prácticas, dispositivos y procedimientos, que regulan culturalmente nuestras temporalidades, no son innatas, normales, ni consustanciales de la naturaleza humana como algunos quieren hacernos creer. Existen desde siempre toda una serie de conflictos y disputas de poder por imponer una visión cultural por sobre otras, un paradigma espacio temporal por sobre otros, luchas que establecen jerarquías, dominios, predominancia de algunos modos de sentir y pensar el tiempo. Como consecuencia de esto, existen tiempo “hegemónicos” y tiempos “contrahegemónicos” o alternativos, tiempos que se proponen como universales y tiempos que plantean modelos opuestos o simplemente diferentes para nuestras temporalidades. Dice Roger Caillois en Temps circulaire, temps rectiligne (1975, traducción de los autores): “…desde su nacimiento, uno está tan acostumbrado a la concepción del tiempo aceptada por quienes lo rodean, que no sería capaz de imaginar que existe otra que a otros les parezca tan natural y lógica como a él le parece la propia. No sospecha que haya aceptado inconscientemente sus implicaciones inexorables. Ignora que cada cultura posee una representación particular de la sucesión histórica y que su propia concepción del mundo, su universo moral, quizás incluso las normas prácticas de su conducta cotidiana aparecen insidiosamente modificadas en ella”.

Nuestra concepción del tiempo, la concepción hegemónica en el occidente de raíz judeo-cristiana y greco-romana, es la de un tiempo uniforme, unívoco, universal, uno. Un tiempo, El Tiempo, que aparece fuertemente ligado a la cosmovisión griega clásica y sobre todo a las explicaciones del movimiento. Ya Aristóteles en su Física (1995 [350a.C.]) nos adelanta: “El tiempo es, pues, el mismo, ya que el número es igual y simultáneo para la alteración y el deslazamiento. Y por esta razón, aunque los movimientos sean distintos y separados, el tiempo es en todas partes el mismo, porque el número de los movimientos iguales y simultáneos es en todas partes uno y el mismo”. Un tiempo que es en todas partes (y para todos) el mismo, igual, simultaneo, y que no casualmente será tomado por la ciencia desde sus etapas formativas para imponer un paradigma por sobre otros, el único tiempo Verdadero. Un tiempo que tiene dirección, pero que es reversible, porque en teoría todos los fenómenos físicos son reversibles. En The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, Isaac Newton (1993) confirma nuestras apreciaciones: “El tiempo absoluto, verdadero y matemático, por sí mismo, y por su propia naturaleza fluye uniformemente, sin consideración por nada externo. De otro modo se nombra la duración: el tiempo relativo, aparente y corriente, es una medida de la duración sensible y externa (ya sea exacta o irregular) por medio del movimiento, la cual es corrientemente usada en lugar del tiempo verdadero”. Es muy interesante notar que en esta cita ya aparece otro tiempo, la duración, el tiempo Bergsoniano, pero asoma denostado frente a un tiempo “verdadero”, es ese otro tiempo “aparente” y “corriente”, es aquel fundado en la percepción, en la experiencia, el del ciudadano común, que claramente no sirve a la ciencia por ser subjetivo, fundamentalmente cuando se persigue lo “absoluto”.

Luego la filosofía se encargará de dudar, de repensar, de poner en crisis al paradigma, que vale la pena aclarar, sigue regulando nuestro comportamiento y nuestras prácticas sociales, a pesar de que la propia ciencia ya se ha ocupado de demostrar que no es absoluto ni verdadero. “El tiempo que trato de determinar es siempre ‘tiempo para’, tiempo para hacer esto o aquello, el tiempo que puedo permitirme para, el tiempo que me puedo tomar para realizar esto o aquello, el tiempo que me tengo que tomar para llevar a término esto o aquello. El mirar-el-reloj se funda en un tomarse-tiempo y surge de él. Para poder tomarme tiempo, tengo que tenerlo en alguna parte”, esta cita de Los problemas fundamentales de la fenomenología, de Martin Heidegger (2000 [1975]), nos coloca frente a una visión muy relevante del tiempo de la modernidad, un tiempo que se tiene, que se posee y que por lo tanto, se puede vender o alquilar, un tiempo del reloj de la fábrica, de la productividad de la industria, un bien del mercado capitalista. Simultáneamente, se sitúa de manera intrínseca como un tiempo de uso, un tiempo en función de algo, funcional, “tiempo para” en palabras de Heidegger. Una perspectiva que para los arquitectos es evidentemente coherente con la misma concepción aplicada al espacio y a las formas, que pretende regular los modos de habitar, predeterminarlos, uniformarlos, y de este modo fugar hacia una utopía del bien común, que paradójicamente confunde el bien con los bienes. Por otro lado, los empiristas hacen vacilar la idea del tiempo absoluto, exterior a nosotros mismos, y se fijará en las sucesiones, las series, los procesos, los ritmos, las continuidades y las discontinuidades. Un tiempo más humano, pero también más relativo, que aparece a partir de la observación y que vuelve a los orígenes del nacimiento del paradigma en el movimiento y el cambio, podríamos decir que rescata el legado de Heráclito frente al triunfo de los seguidores de Parménides: “Siempre que no tenemos percepciones sucesivas, no poseemos la noción del tiempo, aunque exista una sucesión real en los objetos. De este fenómeno, lo mismo que de muchos otros, podemos concluir que el tiempo no puede hacer su aparición en el espíritu solo o acompañado de un objeto fijo e inmutable, sino que se descubre siempre por alguna sucesión perceptible de objetos mudables” (Hume, 2002). Sería interesante pensar que consecuencias podría haber tenido pensar la arquitectura desde esta noción que opone la aparición de la experiencia de lo temporal a los objetos fijos e inmutables. A una arquitectura que incluso hoy en día se concibe como objetual y terminada, metáfora material de la trascendencia.

Una de las discusiones más sugestivas es aquella que, a partir de nuestra experiencia de la sucesión, de lo que ya no es y de lo que todavía no fue, plantea las diferentes versiones de la subdivisión del transcurrir en lo pasado, lo presente y lo futuro. En su Lógica del sentido (1989), Gilles Deleuze nos presenta inicialmente un presente continuo, aunque luego se ocupará de relativizar esta concepción, e incluso contradecirla: “únicamente el pasado y el futuro insisten o subsisten en el tiempo. En lugar de un presente que reabsorbe el pasado y el futuro, un futuro y un pasado que dividen el presente en cada instante, que lo subdividen hasta el infinito en pasado y futuro, en los dos sentidos a la vez”. Un presente infinitesimal frente a un presente eterno. Una discusión filosófica que se hunde en la noche de los tiempos. Quizás como anverso de esta dialéctica aparecen esos otros tiempos, esos tiempos alternativos de otras culturas, uno de los cuales sin duda nos enriquece de sólo pensarlo, el tiempo de la cultura china, una forma de concebir la temporalidad más compleja y dinámica, un tiempo tejido al espacio y al evento, una serie de eventualidades imbricadas en momentos y lugares: “el tiempo chino es un tiempo propio, interior a las cosas, o mejor, a los procesos y a las situaciones. Más que tiempo, hay tiempos. Tan entreverado está el tiempo con el acontecimiento que no sólo es más bien el tiempo del acontecimiento (un tiempo creado por ese concreto acontecer) sino que se anuda también con el espacio; un espacio que, igualmente, tampoco es el espacio sino su espacio, el lugar que el propio acontecer determina y carga con sus propiedades” (Lizcano, 1992). Y es significativo trazar aquí la diferencia que antes mencionábamos, estos otros tiempos son distintos, simplemente inconmensurables, no se pueden comparar con los nuestros, no son contra hegemónicos, no vienen a ponen en crisis nada, ni a oponerse a nada, son otros tiempos.

Por último, el tiempo histórico, ese que nos atrae particularmente por nuestras experiencias docentes. La historia es en sí misma una forma de temporalidad, una forma conectada con los tiempos absolutos o relativos, universales o humanos, de los que hablamos anteriormente. Por ejemplo, en el siguiente texto de Benjamin vemos aparecer de nuevo esta dialéctica del tiempo absoluto de la ciencia, del presente infinitesimal, frente al presente continuo de la simultaneidad: “La historia es objeto de una construcción cuyo lugar no está constituido por el tiempo homogéneo y vacío, sino por un tiempo pleno, ‘tiempo-ahora’. Así la antigua Roma fue para Robespierre un pasado cargado de ‘tiempo-ahora’ que él hacía saltar del continuum de la historia” (Benjamin, 1982). Sin embargo, el punto fundamental de esta cita es la idea de la historia como construcción, es lo que da sentido a la continuidad, todo pasa simultáneamente en la mente del historiador, o dicho de otro modo, todo existe al mismo tiempo. No obstante, la condición narrativa de la historia tal y como la conocemos va acompañada de una temporalidad lineal, de lectura, de relato, que obviamente admite complejidades, ramificaciones, bucles y paralelismos, pero que como dice Paul Ricoeur en El tiempo relatado (1992): “es correlativo del tiempo implicado en la narración de los hechos. Relatar, en efecto, toma tiempo, y sobre todo organiza el tiempo. El relato es un acto configurante que, de una simple sucesión, obtiene formas temporales organizadas en totalidades cerradas. Ese tiempo configurado está estructurado en tramas que combinan intenciones, causas y azares”. De todos modos, aquí llegamos a un punto donde simplemente se abren nuevas discusiones y polémicas, el rol de las intenciones en la historia, así como el concepto de causalidad, son sólo algunas de las cuestiones pendientes, por no hablar del problema del relato en sí y de las características estructurales que traslada la narración a la construcción histórica.

4 Visualizaciones: Representación y Cognición

Podemos decir que todas las anteriores reflexiones sobre el tiempo tienen sentido para nuestro trabajo en función de un objetivo, establecer alternativas al relato historicista a partir de modelos espaciales alternativos. Las representaciones de los acontecimientos, sus relaciones lógicas y topológicas, nos permiten investigar sobre nuevos instrumentos cognitivos para pensar la historia. Las representaciones gráficas y espaciales del tiempo abren nuevas perspectivas sobre la temporalidad a través de analogías y metáforas visuales. La manera en la cual nuestra mente construye nociones de tiempo a través de analogías y la importancia que esto tiene en el resto de nuestro pensamiento ya aparece con claridad en la Crítica de la razón pura (1978) de Immanuel Kant: “el tiempo no puede ser una determinación de fenómenos externos; ni pertenece a una figura ni a una posición, etc., y en cambio, determina la relación de las representaciones en nuestro estado interno. Y, precisamente, porque esa intuición interna no da figura alguna, tratamos de suplir este defecto por medio de analogías y representamos la sucesión del tiempo por una línea que va al infinito, en la cual lo múltiple constituye una serie, que es sólo de una dimensión; y de las propiedades de esa línea concluimos las propiedades todas del tiempo, con excepción de una sola, que es que las partes de aquella línea son a la vez, mientras que las del tiempo van siempre una después de la otra”. Aquí observando las restricciones que impone la analogía espacial del tiempo lineal, pero que evidentemente resulta trasladable a cualquier representación mental o corporal del tiempo. Una cuestión sobre la cual la psicología también ha trabajado desde sus inicios: “Nuestra representación abstracta del tiempo parece más bien estar enteramente tomada del modo de trabajo del sistema P-Cc [Percepción-Conciencia], y corresponder a una autopercepción de éste” (Freud, 1997). Estamos convencidos de que estas restricciones intrínsecas a todo modelo, a toda metáfora, a toda representación, no deben impedir aprovechar la riqueza que nos ofrecen como herramientas del pensamiento, suerte de asistentes cognitivos, y de la potencia que tienen en la investigación, la enseñanza y el aprendizaje, frente a lo establecido, institucionalizado o hegemónico.

Muestras de estos modelos alternativos hay muchas (cfr. Rosenberg, 2010), desde las líneas genealógicas (Línea genealógica de Maximiliano I, Albrecht Dürer, 1516) o las representaciones de la historia (Historia universal, Johannes Bruno, 1672), hasta las exploraciones artísticas de Ward Shelley (Who Invented the Avant Garde? o Frank Zappa), pasando por los modelos híbridos, radiales (Spiegazione della Carta Istorica dell'Italia, Girolamo Andrea Martignoni, 1721), cíclicos (La rueda de la moda, J J Grandville, 1844), de flujos (Strom der Zeiten, Friedrich Strass, 1849 o The Histomap, John Sparks, 1931), o incluso variaciones de las representaciones lineales como la famosa Línea de tiempo de Dubourg. De cualquier manera, estos ejemplos sólo los utilizamos como antecedentes en la investigación o disparadores en el aprendizaje, dentro de una propuesta mayor que apunta a las exploraciones individuales de posibles cartografías del tiempo y la historia que fomenten nuevas construcciones narrativas o incluso nuevos tipos de historicidad.

5 Prácticas: Crítica y Exploración

El trabajo, que es el material (y su sumatoria), serían los casos o muestra a analizar, consiste entonces en tomar como punto de partida la “trasgresión crítica” de la clásica línea de tiempo (como mencionamos anteriormente), como representación gráfica, que contiene en sí una idea/concepto de cronología relacionada con un paradigma que nos lleva a asociar la antecedencia a la causalidad y oculta una metafísica teleológica del tiempo histórico (suceso-sucesión-sucede= realidad= verdad). Esto aparece incluso en cualquier libro clásico de historia básica, la lectura del mismo se vuelve intensamente ambiguo, algo que no podemos explicar, pero que sin embargo existe como una certeza para nuestra conciencia. Este pequeño interrogante es el que utilizamos como disparador para el inicio del trabajo de construcción del Mapa de Tiempo; a veces la posible respuesta la intentamos asociar al concepto de analogía; más que nada porque, bien sabemos, nos sirve de soporte explicativo de un fenómeno un poco menos complejo de explicar que el de tiempo, ya que se incurre regularmente en el error de explicar los fenómenos desde el fenómeno mismo, como el sentido común de incluir parte de la definición que queremos dar de alguna cuestión que intentamos definir, y por ende caemos en una falsedad (tautológica) al definir desde la definición misma aún no explicada; que para nuestro caso no es la de interpretar el tiempo desde la representación lineal.

¿Qué pasa si se parte de la siguiente hipótesis?: el tiempo puede ser visto como una magnitud física que permite secuenciar hechos y determinar momentos. Es necesario conocer los procesos de construcción de las representaciones, debido a que las “representaciones mentales” (estado previo a la representación visual pretendida) se organizan en y bajo estructuras conceptuales, siguiendo procedimientos, volcando ciertas actitudes que le dan sentido, que no son estáticas y que no poseen una única manera de ser abordadas, sino que se anclan en una explicativa psicología cognitiva. En la observación de las coyunturas se sabe que existen desde siempre toda una serie de conflictos y disputas de poder por imponer una visión cultural por sobre otras, un paradigma espacio temporal por sobre otros, luchas que establecen jerarquías, dominios, predominancia de algunos modos de sentir y pensar el tiempo. Las maneras de acceder al conocimiento de éstas es rebasar lo inmediato aumentando las dimensiones en el espacio y en el tiempo del campo de la adaptación, o sea evocar lo que sobrepasa al terreno perceptivo y motor, por tanto hablar de representación es hablar de “reunión de un significador que permite la evocación de un significado procurado por el pensamiento" (Piaget citado en Carretero, 2006).

Como consecuencia de esto, existen tiempos que se proponen como universales y tiempos que plantean modelos opuestos o simplemente diferentes para nuestras temporalidades. Hasta aquí no hemos dejado de hablar de representación, de tiempo y en cierta forma de lo que simboliza el tiempo; y de cómo se llega o se arribaría a un resultado de representación posible del pensamiento del mismo. Y a pesar de que una posibilidad de interpretación del tiempo es la física (piénsese que una línea es una manifestación física de una secuencia de puntos), lo que interesa para este estudio es el aspecto simbólico de la interpretación (parafraseando sería la intención del significado de cada punto). Cassirer señala que más que en un mundo físico, el hombre vive envuelto en un mundo simbólico, en una red construida por el lenguaje, el arte, el mito y la religión; fenómenos todos estos vinculados a la abstracción simbólica, todos estos capaces de generar una manipulación de símbolos abstractos vinculados con la realidad objetiva. De ahí la posibilidad de poder comprender porque los seres humanos podrían construir representaciones diferentes sobre un mismo fenómeno: el tiempo.

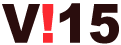

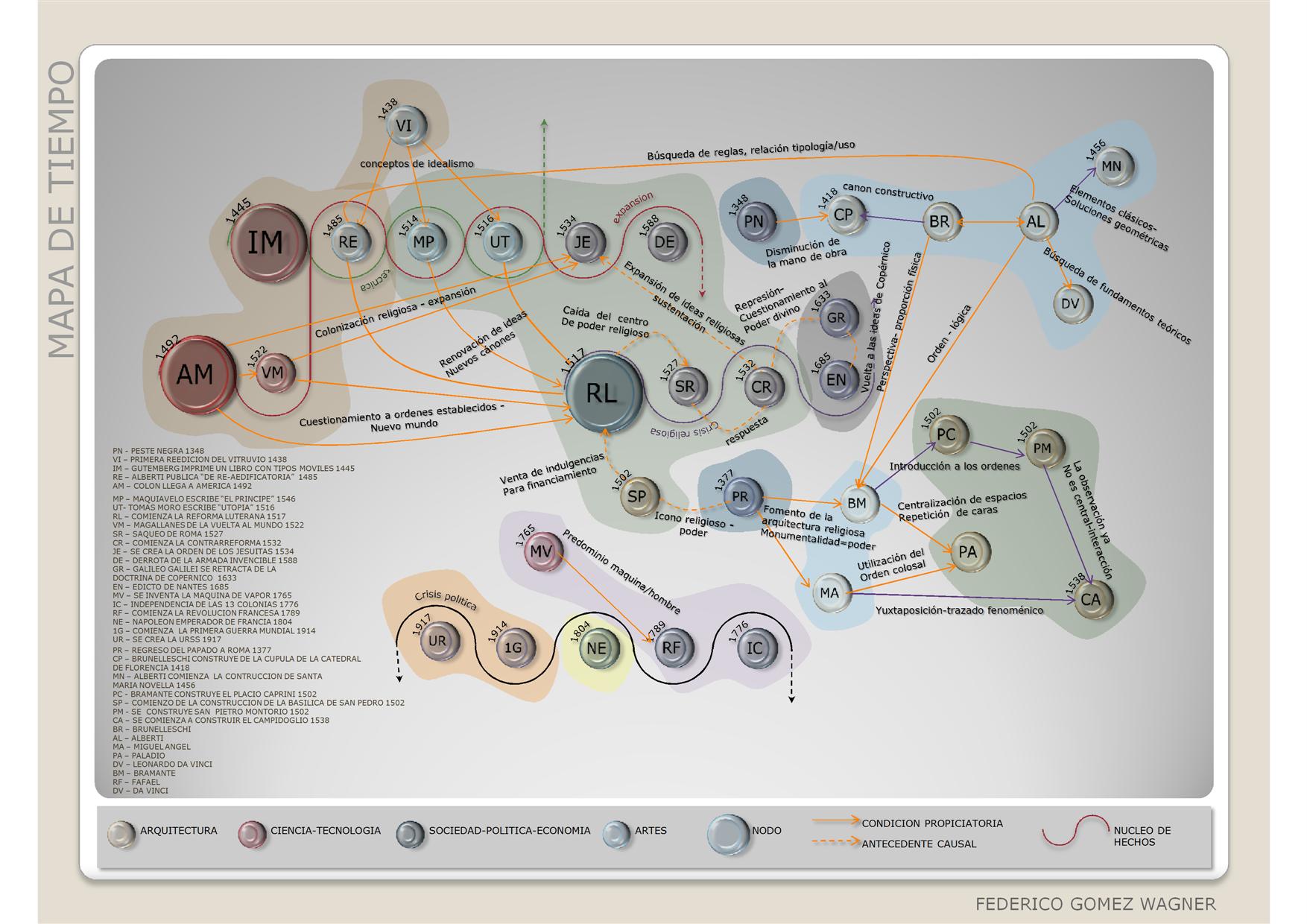

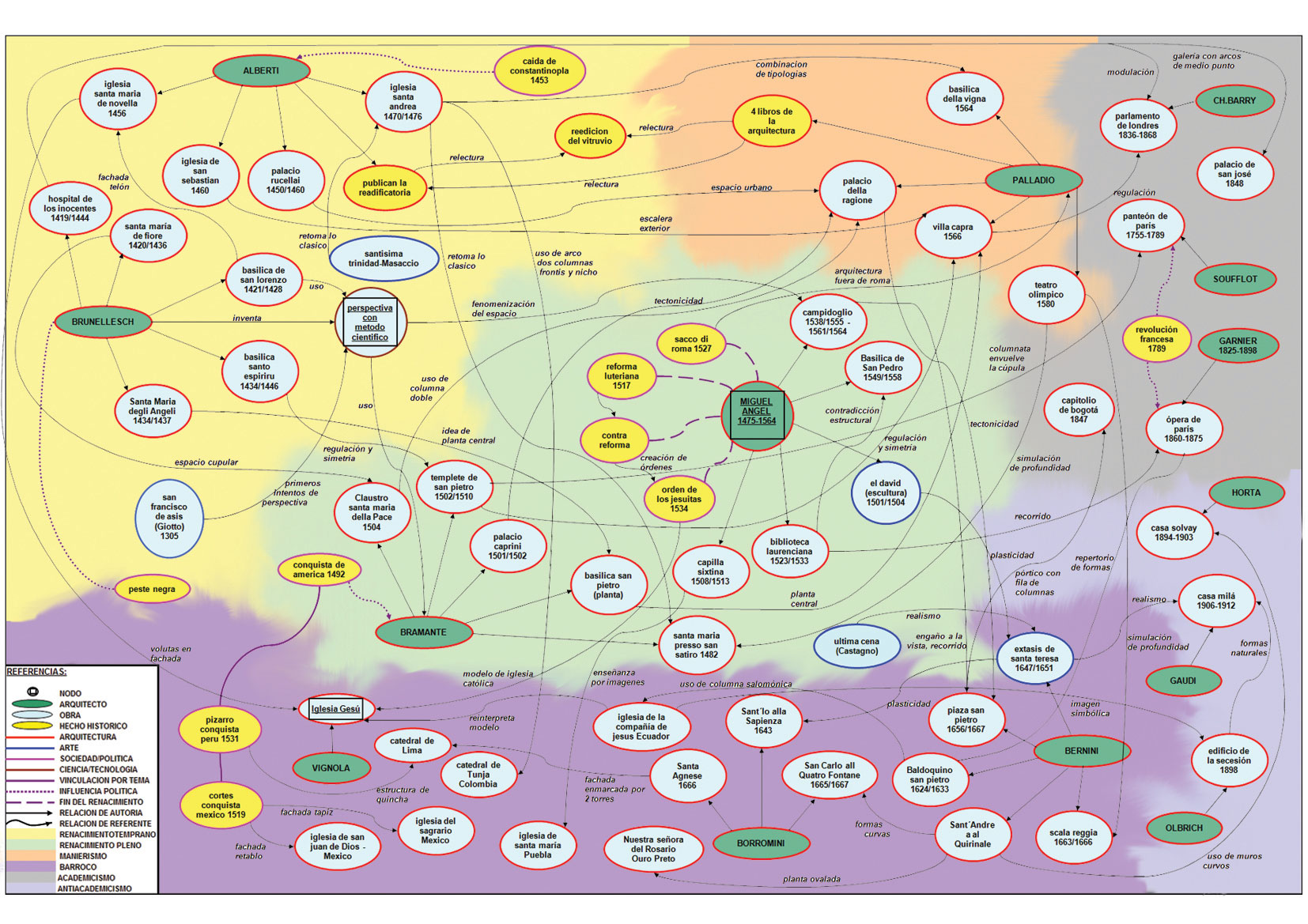

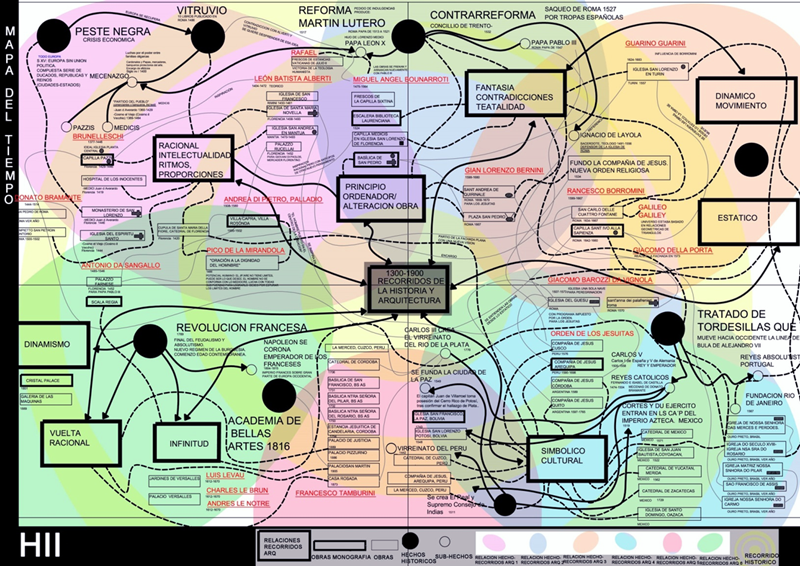

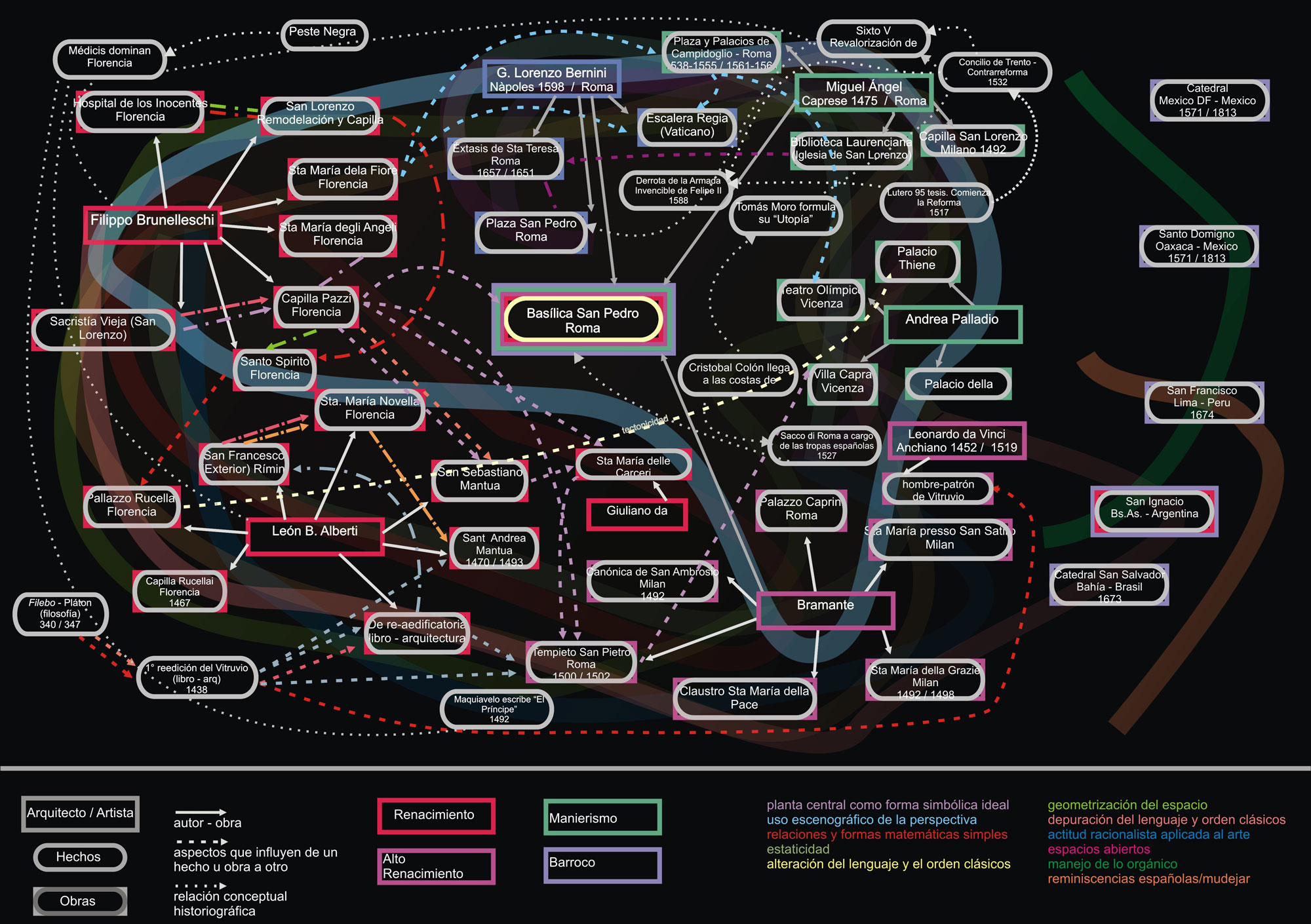

Mostraremos entonces las imágenes representacionales de las posibles interpretaciones del tiempo según las versiones de los alumnos (Fig.1, 2, 3 y 4), donde será factible identificar desde las clásicas secuencia de sucesos (de parecidos formales, de parecidos en las conformaciones conectivas, en los lineamientos de los relatos alternativos, en la elección de hechos circunstanciales absolutos, etc.) a las alternativas interpretativas (de parecidos formales, pero de variación en las conformaciones conectivas), y hasta las identidades particulares de relación general (con valoraciones graficas de conectividad con los tipos de conformaciones conectivas, relatos alternativos y elección de hechos absolutos), y comentar los resultados en la observación de estos casos; que se basan en la comprobación de los resultados de metodologías aplicadas al difundir los sucesos, significando en qué orden de importancia y bajo qué asociación coyuntural fueron dados; (difusión de conocimientos) y de cómo fueron traducidos para ser incluidos en los modelos gráficos; además de que se da cuenta de cómo se ratifica en sí han sido eficaces las herramientas de asociación ejemplificadas mediante el trabajo de cuestiones análogas a las propuestas (esquicios, teóricas, trabajos previos, debates, como búsquedas del tipo y de otras con características de interpretación analítica posterior, de donde se debe extraer mediante la síntesis los elementos a asociar a las conformaciones de las representaciones del tiempo. Este último aspecto tiene se anclaje en la particularidad ya comentada, que el trabajo es anual y que su característica más destacable es que va incrementando su densidad, en cuanto a sus elementos y relaciones, por cuanto se van registrando más datos.

Podemos decir que todas las anteriores reflexiones sobre el tiempo tienen sentido para nuestro trabajo en función de un objetivo, establecer alternativas al relato historicista a partir de modelos espaciales alternativos. Las representaciones de los acontecimientos, sus relaciones lógicas y topológicas, nos permiten investigar sobre nuevos instrumentos cognitivos para pensar la historia. Las representaciones gráficas y espaciales del tiempo abren nuevas perspectivas sobre la temporalidad a través de analogías y metáforas visuales. La manera en la cual nuestra mente construye nociones de tiempo a través de analogías impone restricciones, pero estamos convencidos de que estas restricciones intrínsecas a todo modelo, a toda metáfora, a toda representación, no deben impedir aprovechar la riqueza que nos ofrecen como herramientas del pensamiento, suerte de asistentes cognitivos, y de la potencia que tienen en la investigación, la enseñanza y el aprendizaje, frente a lo establecido, institucionalizado o hegemónico.

“Y el fin de toda exploración será llegar a donde empezamos / Y conocer el lugar por primera vez…” T. S. Eliot, Cuatro cuartetos.

Referencias

Aristóteles, 1995. Física. Trad. de Guillermo R. de Echandía. Madrid: Gredos. 1st ed. 350a.C.

Benjamin, W. 1982. Tesis de filosofía de la historia. Discursos interrumpidos. Madrid: Taurus.

Brunner, J. J. 1989. Globalización cultural y posmodernidad. Santiago de Chile: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Callois, R. 1975. Obliques. Précédé de Images, images. Paris: Stock.

Carretero, M. 2006. Constructivismo y educación. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Chartier, R. 1996. El mundo como representación. Historia cultural: entre práctica y representación. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Deleuze, G. 1989. Lógica del sentido. Trad. Miguel Morey y Víctor Molina. Barcelona: Paidós.

Freud, S. 1997. Obras Completas, Tomo XVIII: Más Allá del principio de placer, Psicología de las masas y Análisis del yo y otras obras. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Halbwachs, M. 2004. La Memoria Colectiva. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Heidegger, M. 2000. Los problemas fundamentales de la fenomenología. Madrid: Trotta. Trad. y prólogo de Juan José García Norro. Original title: Die Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie, V. Klostermann, Frankfurt a. M., 1975. Edición de F.-W. von Herrmann.

Hume, D. 2002. Tratado de la naturaleza humana. Trad. Félix Duque. Original title: A treatise of human nature. Madrid: RBA.

Kant, I., 1978. Crítica de la razón pura. Original title: Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Prólogo. Trad. Pedro Ribas. Madrid: Alfaguara.

Le Goff, J., 1991. El orden de la memoria: el tiempo como imaginario. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

Lizcano, E., 1992. El tiempo en el imaginario social chino. Archipiélago, 10/11, pp.59-67.

Martin Iglesias, R., 2008. Hacia una arquitectura de la historia, un enfoque constructivista. In: Actas del III Encuentro Taller de Docentes de Historia de la Arquitectura, el Diseño y la Ciudad. Buenos Aires; Junio 2008, Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Urbanismo, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Martin I. R., 2010. La enseñanza de la historia frente a la amnesia proyectual. In: Actas del IV Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. Montevideo, Noviembre 2010, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad de la República.

Martin I. R., Robles, M. and Fagilde, S., 2012. El viajero del tiempo necesita mapas. In: Actas del V Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. San Juan, Septiembre 2012, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de San Juan.

Martin I. R., et al. 2014. Topoheterocronías II: Avances en la sistematización de un instrumento de visualización del tiempo histórico. In: Actas del VI Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. La Plata, Mayo 2014, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Middelton, D. and Edwards, D. 1992. Memoria compartida. La naturaleza social del recuerdo y del olvido. Barcelona: Paidós.

Newton, I.1993. Principios matemáticos de la Filosofía natural. Trad. Antonio Escohotado. Barcelona: Altaya. Original Title: Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

Ricoeur, P. 1992. La función narrativa y el tiempo. Buenos Aires: Almagesto.

Rifkin, J. 2004. Las Guerras del Tiempo, El Siglo de la Biotecnología y El sueño europeo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Robles, M., et al.2016. Topoheterocronías III: Avances en la sistematización de un instrumento de visualización del tiempo histórico. Estudio y búsqueda de modelos de representación del tiempo mediante el empleo de mapas multidimensionales. En: Actas del VII Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. Rosario, Mayo 2016, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Rosenberg, D. and Grafton, A. 2010. Cartographies of Time: a history of the timeline. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

Sant A.2010. Confesiones. Madrid: Gredos.

Topoheterocronies: analogical models for time visualization

Rodrigo Martin Iglesias is architect and Doctor in Design. Professor of History of Architecture (UBA) and History and Critique of Architecture (UNLaM). Director of binational Master's Degree Open Design (UBA - Humboldt University of Berlin). Coordinator of research in the Design Centre (FADU). He studies digital manufacturing, productive and morphogenetic processes, semiotics of sketching.

Marcelo Javier Robles is architect. Professor of History of Architecture (UBA) and Head of Practical Works of History and Criticism (UNLaM). Director of the research project "Topoheterocronías: Analog models for the visualization of time" (FADU-UBA). Founding partner of the ÁGORA Arquitectura studio.

How to quote this text: Martin Iglesias, R. and Robles, M., 2017. Topoheterocronies: analogical models for time visualization. V!RUS, 15. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=4&item=2&lang=en>. [Accessed: 10 July 2025].

Abstract

We present the foundations of a research project which is currently in development. This project aims to explore new dimensions and configurations of a traditionally one-dimensional Time. Initially we have systematized the material produced since 2005 with students of History of Architecture in relation to analogical (multidimensional) Timemaps, while we sought for theoretical tools that allows its interpretation. We have characterized different times and durations, from phenomenological aspects of temporal construction and perception, to historical and natural phenomena of long duration. Finally, we explored analogical and digital visualization tools to understand the intrinsic complexity of Time and its models.

Keywords: Visualization, Time, Timemaps, Analogical models, Topoheterochronies

Introduction

We present here the bases and partial results of a research project that is currently under development. The aforementioned project aims to explore new dimensions and configurations of a traditionally one-dimensional and linear time. In the initial stage it has been tried to systematize the material produced during more than eight years with the History of Architecture students in relation to the multidimensional Time Maps and to find or to design theoretical instruments to interpret them. To this end, it has been proposed, on the one hand, the research and characterization of the different Times and Durations, from the phenomenal aspects of perception and temporal construction, to the long-term historical and natural phenomena. On the other hand, it has been sought to find and design representation and visualization tools that help the understanding of the aforementioned phenomena in their intrinsic complexity. Likewise, the work is framed in a line of exploration of new pedagogical instruments in teaching within the framework of constructivist didactics, as well as an intrinsic critical reflection on traditional tools and their conceptualizations, a subject on which we have already spoken in scientific events previous (Martin Iglesias, 2008, 2010, 2012, Robles, 2014, 2016). It is worth mentioning as an illustrative example the initial problems that arise in the moment of facing the practice of the class: the evaluation and the adequate use of the previous knowledge of the student, crucial moment of the educational process, to which is not given due attention. We say crucial because it is situated as an instance prior to the practice itself from the point of view of the diagnosis of the state in which the students are with respect to such knowledge. The awareness in the use of these preconcepts and previous learning, by the teacher, is what makes learning a significant activity, particularly when it comes to the relationship between new knowledge and the one that the student already has as a precondition of understanding.

2 Topoheterocronies

The starting point is the critical transgression of the classic timeline, as a graphic representation of a sequence of events, which obviously contains in it an idea / concept of chronology directly related to a cultural paradigm that leads us to associate the antecedent to the causality and that conceals a teleological metaphysics of historical time. This obviously appears both in our agendas or calendars, and in the most elaborate discourses on historical phenomena and the stories that are generally constructed around them. At the same time, traditional representations do not include all events, but only those that are considered relevant from a certain point of view, in general in relation to the changes or repercussions that these supposedly generate a posteriori. This confirms the existence of causalist logic and shows to what extent these types of constructions are the product of a cultural and ideological subjectivity that finally establishes the connections of events and consequences in a tautological way.

Beyond the fact that the existence of this conception of time also belongs to history and an archeology of its constitution can be realized as a cultural device, it is also interesting to note that within the paradigm there have been multiple alternative explorations that range from the representation of narrative digressions as non-linear paths in the Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne around 1760, going through the counterfactual Ucronies of Charles Renouvier, to the arguments of Henri Bergson in the late nineteenth century for a distinction between the mathematical and homogeneous conception of time and heterogeneous experience of duration, which obviously is impossible to represent in the linear model.

3 Temporalities: Hegemonic and Alternative Times

"What, then, is the time?" If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to whoever asks me, I do not know. However, I certainly affirm that if nothing happened, there would be no past time, and if nothing happened, there would be no future time, and if there was nothing, there would be no present time". This phrase, taken from the Confessions of St. Augustine (2010, our translation), shows us how time is something double, intensely ambiguous, something that we cannot explain, but that nevertheless exists as a certainty for our conscience.

There are multiple mental representations of time, deeply related to the perceptions we have of him and the conceptualizations we make from them, these representations are imbricated with cultural patterns that configure and configure us. Since we are born our experiences with time are mediated by a series of social conventions, cultural patterns and patterns of action, whose function is to regulate their use and which is common to a given group. In the words of Jeremy Rifkin: "Each culture has its own unique set of temporary fingerprints. Knowing a town is equivalent to knowing the values of the time they have adopted to live. In order to know ourselves, the reason why we influence one another and the world in the way we do, we must first understand the temporal dynamics that govern human transit in history" (Rifkin, 2004, our translation). These practices, devices and procedures, which culturally regulate our temporalities, are not innate, normal, nor consubstantial of human nature as some would have us believe. There have always been a series of conflicts and power disputes over imposing a cultural vision over others, a temporal space paradigm over others, struggles that establish hierarchies, dominions, predominance of some ways of feeling and thinking about time. As a consequence of this, there are "hegemonic" times and "counterhegemonic" or alternative times, times that are proposed as universal and times that pose opposite or simply different models for our temporalities. Says Roger Caillois in Temps circulaire, temps rectiligne (1975, our translation): "... since his birth, one is so accustomed to the conception of time accepted by those around him, that he would not be able to imagine that there is another that others think is so natural and logic as he thinks of his own. He does not suspect that he has unconsciously accepted his inexorable implications. He ignores that each culture has a particular representation of the historical succession and that its own conception of the world, its moral universe, perhaps even the practical norms of its daily behavior appear insidiously modified in it".

Our conception of time, the hegemonic conception in the West of Jew-Christian and Greek-Roman roots, is that of a uniform, univocal, universal time, one. One time, El Tiempo, which appears strongly linked to the classical Greek worldview and above all to the explanations of the movement. Already Aristotle in his Physics (1995 [350a.C.], our translation) advances us: "The time is, then, the same, since the number is equal and simultaneous for the alteration and the dislocation. And for this reason, although the movements are distinct and separate, time is everywhere the same, because the number of equal and simultaneous movements is everywhere one and the same". A time that is everywhere (and for all) the same, equal, simultaneous, and not coincidentally taken by science from its formative stages to impose a paradigm on others, the only True time. A time that has direction, but that is reversible, because in theory all physical phenomena are reversible. In The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, Isaac Newton (1993, our translation) confirms our insights: "Absolute, true and mathematical time, by itself, and by its very nature flows uniformly, without regard to anything external. Otherwise the duration is named: the relative, apparent and current time, is a measure of the sensible and external duration (either exact or irregular) by means of movement, which is commonly used instead of true time". It is very interesting to note that in this appointment there is another time, duration, the Bergsonian time, but it appears reviled in front of a "real" time, it is that other "apparent" and "ordinary" time, it is based on perception, in experience, that of the common citizen, which clearly does not serve science because it is subjective, fundamentally when pursuing the "absolute".

Then philosophy will be responsible for doubting, rethinking, putting the paradigm in crisis, which is worth clarifying, it continues to regulate our behavior and our social practices, despite the fact that science itself has already tried to show that it is not absolute not true. "The time I try to determine is always 'time for', time to do this or that, the time I can afford for, the time I can take to accomplish this or that, the time that I have to take to carry term this or that. The watch-the-clock is based on a taking-time and emerges from it. In order to take time, I have to have it somewhere", this quote from The Fundamental Problems of Phenomenology, by Martin Heidegger (2000 [1975], our translation), puts us in front of a very relevant vision of the time of modernity, a time that we have, that is owned and that therefore, it can be sold or rented, a time of the factory clock, of the productivity of the industry, a good of the capitalist market. Simultaneously, it is placed intrinsically as a time of use; a time based on something, functional, "time for" in Heidegger's words. A perspective that for architects is clearly consistent with the same concept applied to space and forms, which aims to regulate the ways of inhabiting, predetermine, standardize, and thus escape to a utopia of the common good, which paradoxically confuses the good with the goods. On the other hand, the empiricists make the idea of absolute time, outside ourselves, hesitate, and will look at the successions, the series, the processes, the rhythms, the continuities and the discontinuities. A more human, but also more relative time, that appears from the observation and that returns to the origins of the birth of the paradigm in the movement and the change, we could say that rescues the legacy of Heraclitus against the triumph of the followers of Parmenides: "Whenever we do not have successive perceptions, we do not have the notion of time, although there is a real succession in the objects. Of this phenomenon, as well as of many others, we can conclude that time cannot appear in the spirit alone or accompanied by a fixed and immutable object, but is always discovered by some perceptible succession of changeable objects" (Hume, 2002, our translation). It would be interesting to think what consequences architecture might have had from the notion that opposes the appearance of the experience of the temporal to fixed and immutable objects. To an architecture that even today is conceived as objectual and finished, material metaphor of transcendence.

One of the most suggestive discussions is that which, from our experience of the succession, of what is no longer and of what was not yet, raises the different versions of the subdivision of the past, the present and the future. In his Logic of meaning (1989), Gilles Deleuze presents us initially with a continuous present, although later he will deal with relativizing this conception, and even contradicting it: "only the past and the future insist or subsist in time. Instead of a present that reabsorbs the past and the future, a future and a past that divide the present in each instant, which subdivide it to infinity in past and future, in both senses at the same time" (our translation). An infinitesimal present in front of an eternal present. A philosophical discussion that sinks into the night of time. Perhaps as an obverse of this dialectic those other times appear, those alternative times of other cultures, one of which undoubtedly enriches us just by thinking about it, the time of Chinese culture, a way of conceiving the most complex and dynamic temporality, a time woven into space and the event, a series of eventualities imbricated in times and places: "Chinese time is a time of its own, internal to things, or better, to processes and situations. More than time, there are times. So intertwined is the time with the event that it is not only the time of the event (a time created by that concrete happening) but also knots with the space; a space that, equally, is not the space but its space, the place that the own event determines and loads with its properties" (Lizcano, 1992, our translation). And it is significant to draw here the difference that we mentioned before, these other times are different, simply incommensurable, they cannot be compared with ours, they are not counterhegemonic, they do not come to put anything in crisis, nor to oppose anything, they are other times.

Finally, the historical time, that which attracts us particularly for our teaching experiences. History is in itself a form of temporality, a form connected with absolute or relative times, universal or human, of which we spoke earlier. For example, in the following text of Benjamin we see again this dialectic of the absolute time of science, of the infinitesimal present, in front of the continuous present of simultaneity: "History is the object of a construction whose place is not constituted by time homogeneous and empty, but for a full time, 'time-now'. Thus, ancient Rome was for Robespierre a past loaded with 'time-now' that he made jump out of the continuum of history" (Benjamin, 1982, our translation). However, the fundamental point of this quote is the idea of history as a construction, it is what gives continuity meaning, everything happens simultaneously in the mind of the historian, or in other words, everything exists at the same time. However, the narrative condition of history as we know it is accompanied by a linear temporality, of reading, of story, which obviously admits complexities, ramifications, loops and parallels, but as Paul Ricoeur says in The Time Related (1992, our translation): "Is correlative of the time involved in the narration of the facts. Reporting, in effect, takes time, and above all, organizes time. The story is a configuring act that, from a simple succession, obtains temporal forms organized in closed totalities. This configured time is structured in frames that combine intentions, causes and hazards”. Anyway, here we come to a point where new discussions and polemics are simply opened, the role of intentions in history, as well as the concept of causality, are just some of the pending issues, not to mention the problem of the narrative itself and the structural characteristics that translates the narrative to the historical construction.

4 Visualizations: Representation and Cognition

We can say that all the previous reflections on time make sense for our work in terms of an objective, establishing alternatives to the historicist story from alternative spatial models. The representations of events, their logical and topological relationships, allow us to investigate new cognitive tools to think about history. The graphic and spatial representations of time open new perspectives on temporality through analogies and visual metaphors. The way in which our mind constructs notions of time through analogies and the importance that this has in the rest of our thought already appears clearly in Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1978, our translation): "Time cannot be a determination of external phenomena; neither belongs to a figure or a position, etc., and instead, determines the relationship of the representations in our internal state. And, precisely, because that internal intuition does not give any figure, we try to supply this defect by means of analogies and we represent the succession of time by a line that goes to infinity, in which the multiple constitutes a series, which is only one dimension; and from the properties of that line we conclude the properties all of the time, with the exception of one, which is that the parts of that line are at the same time, while those of time are always one after the other". Here observing the restrictions imposed by the spatial analogy of linear time, but which is evidently transferable to any mental or bodily representation of time. A question on which psychology has also worked since its inception: "Our abstract representation of time seems rather to be entirely taken from the working mode of the P-Cc system [Perception-Consciousness], and correspond to a self-perception of it" (Freud, 1997). We are convinced that these restrictions intrinsic to any model, to every metaphor, to any representation, should not prevent us from taking advantage of the wealth they offer us as tools of thought, as a kind of cognitive assistants, and of the power they have in research, teaching and learning, as opposed to established, institutionalized or hegemonic.

There are many examples of these alternative models (see Rosenberg, 2010), from the genealogical lines (Maximilian I genealogical line, Albrecht Dürer, 1516) or the representations of history (Universal History, Johannes Bruno, 1672), to the explorations by Ward Shelley (Who invented the Avant Garde? or Frank Zappa), going through the hybrid, radial models (Spiegazione della Carta Istorica dell'Italia, Girolamo Andrea Martignoni, 1721), cyclicals (The wheel of fashion, JJ Grandville, 1844), of flows (Strom der Zeiten, Friedrich Strass, 1849 or The Histomap, John Sparks, 1931), or even variations of linear representations such as the famous Dubourg Timeline. Anyway, these examples are only used as background in the research or triggers in learning, within a larger proposal that points to individual explorations of possible cartographies of time and history that encourage new narrative constructions or even new types of historicity.

5 Practices: Criticism and Exploration

The work, which comes from the material and its summation (the cases or sample to be analyzed), then consists of taking as a starting point the "critical transgression" of the classic timeline (as mentioned above), as a graphic representation, which contains in itself an idea / concept of chronology related to a paradigm that leads us to associate antecedence with causality and conceals a teleological metaphysics of historical time (event-succession-happens = reality = truth). This appears even in any classic book of basic history, the reading of it becomes intensely ambiguous, something that we cannot explain, but that nevertheless exists as a certainty for our conscience. This little question is what we use as a trigger for the beginning of the construction work of the Time Map; sometimes the possible answer we try to associate with the concept of analogy; more than anything because, well we know, it serves as an explanatory support for a phenomenon that is a little less complex to explain than that of time, since the error is regularly incurred in explaining the phenomena from the phenomenon itself, as the common sense of including part of the definition we want to give of some issue that we try to define, and therefore we fall into a falsehood (tautological) to define from the definition itself not yet explained; that for our case is not to interpret the time from the linear representation.

What happens if we start from the following hypothesis? Time can be seen as a physical quantity that allows us to sequence facts and determine moments. It is necessary to know the processes of construction of the representations, because the "mental representations" (state prior to the intended visual representation) are organized in and under conceptual structures, following procedures, overturning certain attitudes that give meaning, which are not static and that do not have a unique way of being addressed, but are anchored in an explanatory cognitive psychology. In the observation of the conjunctures it is known that there have always been a whole series of conflicts and power disputes over imposing a cultural vision over others, a temporal space paradigm over others, struggles that establish hierarchies, dominions, predominance of some modes of feel and think the time. The ways to access the knowledge of these is to go beyond the immediate increasing dimensions in space and time in the field of adaptation, or evoke what exceeds the perceptual and motor field, therefore speaking of representation is to speak of "meeting of a significator that allows the evocation of a meaning procured by thought" (Piaget cited in Carretero, 2006, our translation).

As a consequence of this, there are times that are proposed as universal and times that pose opposite or simply different models for our temporalities. So far we have not stopped talking about representation, time and in a certain way what symbolizes time; and how one arrives or arrives at a result of possible representation of the thought of it. And although a possibility of interpretation of time is physics (think that a line is a physical manifestation of a sequence of points), what is interesting for this study is the symbolic aspect of the interpretation (paraphrasing would be the intention of the meaning of each point). Cassirer points out that more than in a physical world, man lives wrapped in a symbolic world, in a network constructed by language, art, myth and religion; all these phenomena linked to symbolic abstraction, all these capable of generating a manipulation of abstract symbols linked to objective reality. Hence the possibility of being able to understand why human beings could construct different representations about the same phenomenon: time.

We will then show the representational images of the possible interpretations of time according to the students' versions (Fig.1, 2, 3 and 4), where it will be possible to identify from the classic sequence of events (of formal similarities, of similarities in the connective conformations, in the guidelines of the alternative accounts, in the choice of absolute circumstantial facts, etc.) to the interpretative alternatives (of formal similarities, but of variation in the connective conformations), and even to the particular identities of the general relationship (with graphic assessments of connectivity with the types of connective conformations, alternative stories and choice of absolute facts), and comment on the results in the observation of these cases; that are based on the verification of the results of methodologies applied to disseminate the events, meaning in what order of importance and under what conjunctural association they were given; (dissemination of knowledge) and how they were translated to be included in the graphic models; In addition to realizing how it is ratified in itself, the tools of association exemplified by the work of analogous issues to the proposals (schizophrenics, theoretical, previous works, debates, as searches of the type and of others with characteristics of interpretation) have been effective. Subsequent analysis, from which the elements to be associated to the conformations of the representations of time must be extracted through the synthesis. This last aspect is anchored in the particularity already mentioned, that the work is annual and that its most outstanding characteristic is that increasing its density, in terms of its elements and relationships, as more data is recorded.

The hybrid dynamic time map (Fig.1) starts from a destructuring of a traditional timeline based on a logic of flows. From certain categories, it finds sequences or causal links that generate discontinuities in the line and clusters of facts. The process started with an analog approach and CorelDraw then used for the final configurations. In the case of the topological cartographic time map (Fig.2), the metaphor of the territory is used to generate regions, sectors and connections, as well as to establish distance and proximity relationships. In this case we started working with VUE (Visual Understanding Environment) to then move on to other graphic editing programs. The circular or conical time map (Fig. 3) is particularly interesting for its structural proposal, which directly impacts the logic of its historical discourse, and which is located as the second great spatial-temporal analogy, just after the line. In this case we worked exclusively by hand with traditional drawing methods. In another sense, the categorial relational map (Fig. 4) seeks to weave the networks of events from certain types of relationships that construct units of meaning where the factual appears subordinated to the conceptual. Here digitality appeared from the first drafts, using Illustrator primarily as a tool. Finally, in the cybernetic diagrammatic time map (Fig.5), the use of software (AutoCAD) and its configuration are complemented in a coherent way, highlighting the metaphor of the electronic circuit and the creation of reading levels from the systematization type of the nodes and their interconnection from an infrastructure of narrative paths.

We can say that all the previous reflections on time have meaning for our work in terms of an objective, to establish alternatives to the historicist story from alternative graphic-spatial models. The representations of events, their logical and topological relationships, allow us to investigate new cognitive tools to think about history. The graphic and spatial representations of time open new perspectives on temporality through analogies and visual metaphors. The way in which our mind constructs notions of time through analogies imposes restrictions, but we are convinced that these restrictions intrinsic to every model, to every metaphor, to every representation, should not prevent us from taking advantage of the wealth they offer us as tools of the thinking, luck of cognitive assistants, and the power they have in research, teaching and learning, compared to the established, institutionalized or hegemonic.

One of the most powerful manifestations of the role that history can play in education is the reflection on the construction of the individual identity in front of the collective identity in a culturally globalized world. We have verified that this point generates a positive response from the students and collaborates in the always difficult motivational task. The crisis in the models imposed in the construction of identities, the surprising uniformity that hides the apparent diversity of individual identities in front of the identity collective as a place of refuge and resistance of the local in the current context of cultural globalization (Brünner, 1989). On the other hand, Memory appears to be essential when presenting History and making it dialogue with stories and memories (Middelton and Edwards, 1992). The conservation and the record of what happened, who registers what and how, who has been left out of the registry and how it is possible to trace their tracks. And again the importance of memory in the construction of individual identity, tell one's own history and inscribe it in major historical processes, contributing to give meaning to what seemed distant, abstract and impersonal, and at the same time building networks of increasing complexity of one's own individuality. Here History acts as a fundamental element in the articulation of a collective memory (Halbwachs, 2004) and a personal history, thus favoring the feeling of belonging to the autonomy of the inoperative individualism, as well as the acquisition of a historical dimension of the acts themselves (Le Goff, 1991). Transcendence versus immanence.

References

Aristóteles, 1995. Física. Trad. de Guillermo R. de Echandía. Madrid: Gredos. 1st ed. 350a.C.

Benjamin, W. 1982. Tesis de filosofía de la historia. Discursos interrumpidos. Madrid: Taurus.

Brunner, J. J. 1989. Globalización cultural y posmodernidad. Santiago de Chile: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Callois, R. 1975. Obliques. Précédé de Images, images. Paris: Stock.

Carretero, M. 2006. Constructivismo y educación. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Chartier, R. 1996. El mundo como representación. Historia cultural: entre práctica y representación. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Deleuze, G. 1989. Lógica del sentido. Trad. Miguel Morey y Víctor Molina. Barcelona: Paidós.

Freud, S. 1997. Obras Completas, Tomo XVIII: Más Allá del principio de placer, Psicología de las masas y Análisis del yo y otras obras. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Halbwachs, M. 2004. La Memoria Colectiva. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Heidegger, M. 2000. Los problemas fundamentales de la fenomenología. Madrid: Trotta. Trad. y prólogo de Juan José García Norro. Original title: Die Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie, V. Klostermann, Frankfurt a. M., 1975. Edición de F.-W. von Herrmann.

Hume, D. 2002. Tratado de la naturaleza humana. Trad. Félix Duque. Original title: A treatise of human nature. Madrid: RBA.

Kant, I., 1978. Crítica de la razón pura. Original title: Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Prólogo. Trad. Pedro Ribas. Madrid: Alfaguara.

Le Goff, J., 1991. El orden de la memoria: el tiempo como imaginario. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

Lizcano, E., 1992. El tiempo en el imaginario social chino. Archipiélago, 10/11, pp.59-67.

Martin Iglesias, R., 2008. Hacia una arquitectura de la historia, un enfoque constructivista. In: Actas del III Encuentro Taller de Docentes de Historia de la Arquitectura, el Diseño y la Ciudad. Buenos Aires; Junio 2008, Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Urbanismo, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Martin I. R., 2010. La enseñanza de la historia frente a la amnesia proyectual. In: Actas del IV Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. Montevideo, Noviembre 2010, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad de la República.

Martin I. R., Robles, M. and Fagilde, S., 2012. El viajero del tiempo necesita mapas. In: Actas del V Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. San Juan, Septiembre 2012, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de San Juan.

Martin I. R., et al. 2014. Topoheterocronías II: Avances en la sistematización de un instrumento de visualización del tiempo histórico. In: Actas del VI Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. La Plata, Mayo 2014, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Middelton, D. and Edwards, D. 1992. Memoria compartida. La naturaleza social del recuerdo y del olvido. Barcelona: Paidós.

Newton, I.1993. Principios matemáticos de la Filosofía natural. Trad. Antonio Escohotado. Barcelona: Altaya. Original Title: Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

Ricoeur, P. 1992. La función narrativa y el tiempo. Buenos Aires: Almagesto.

Rifkin, J. 2004. Las Guerras del Tiempo, El Siglo de la Biotecnología y El sueño europeo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Robles, M., et al.2016. Topoheterocronías III: Avances en la sistematización de un instrumento de visualización del tiempo histórico. Estudio y búsqueda de modelos de representación del tiempo mediante el empleo de mapas multidimensionales. En: Actas del VII Encuentro-Talleres de Docentes e investigadores en Historia del Diseño, Arquitectura y Ciudad. Rosario, Mayo 2016, Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Rosenberg, D. and Grafton, A. 2010. Cartographies of Time: a history of the timeline. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

Sant A.2010. Confesiones. Madrid: Gredos.