A narrativa do Museu da Cidade: Brasília inscrita na pedra

Eduardo Oliveira Soares é arquiteto e urbanista. Pesquisador na Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, da Universidade de Brasília (UnB). Estuda narrativas fotográficas sobre o Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro.

Como citar esse texto: SOARES, E. A narrativa do Museu da Cidade: Brasília inscrita na pedra. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 15, 2017. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=4&item=7&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 02 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

A Praça dos Três Poderes, em Brasília, abriga o Museu da Cidade, edificação tombada local e nacionalmente. O museu-monumento foi projetado por Oscar Niemeyer em 1958 e inaugurado em 1960 com a finalidade de ser um Lugar da Memória. Seu acervo é composto de textos em escrita cuneiforme que apresentam uma narrativa sobre o processo que originou a cidade e os personagens que a viabilizaram. Por meio do contato com o seu acervo, o visitante tem acesso a uma narrativa que influencia a avaliação da sua existência enquanto indivíduo e integrante da sociedade. Assim, esse registro do passado também contribui na constituição de uma memória individual e coletiva. Objetivando a avaliação do acervo do museu – que é indissociável da sua arquitetura – o artigo está estruturado em três partes: o resgate do percurso de projetação do edifício, a reflexão sobre conceitos de narrativas e, por fim, a leitura e análise dos textos gravados nas paredes. Os painéis do Museu privilegiam a identificação do Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek como o principal nome responsável pela mudança da Capital e a inserção de Brasília em uma longa cronologia que apresenta a sua construção como fruto de um anseio da nação.

Palavras-chave: Brasília, Narrativa, Patrimônio

1 Introdução

A inauguração de uma cidade planejada marca o fim de um ciclo de idealização, planejamento, projeto e construção. Em Brasília, nova capital inaugurada em 1960, houve extenso registro documental da sua concepção, por meio de reportagens, livros, fotografias, filmagens. Alguns discursos destacam o desenvolvimento e empreendedorismo daquele momento, outros as condições precárias de trabalho e moradia dos trabalhadores pioneiros ou os impactos do custo de construção para o país. Esses relatos contextualizam, sob diferentes abordagens, a criação dessa cidade que conseguiu materializar o pensamento da arquitetura e urbanismo daquela época.

O Relatório do Plano Piloto elaborado por Lucio Costa (1957, p. 18) inicia com reticências, para em seguida sintetizar elegantemente os antecedentes da cidade: "[...] José Bonifácio, em 1823, propõe a transferência da Capital para Goiás e sugere o nome de BRASÍLIA". Já a publicação Por que construí Brasília, de Juscelino Kubitschek (2000), registra os antecedentes, a construção, a inauguração e os desdobramentos do processo de implantação da cidade em volumosa obra de quase 500 páginas. São visões singulares, pois um foi o autor do plano urbanístico da cidade e o outro o Presidente da República em cujo mandato a cidade foi construída. Porém, todos os registros os são. As maneiras de perceber, vivenciar e relatar fazem-se únicas, originando diversas narrativas.

Em se tratando da narrativa de um evento ou fato histórico, o conteúdo nunca será óbvio ou único. Para cada versão apresentada existem outras infinitas possibilidades, inclusive a de se ocultar determinadas passagens. Análoga à pequena frase de Lucio Costa que introduz o Relatório do Plano Piloto há em Brasília um pequeno museu-monumento (Fig. 1) inaugurado por Juscelino Kubitschek no mesmo dia da transferência da Capital (Fig. 2). O desejo dos governantes em comunicar e registrar suas conquistas e feitos comumente gera artefatos que sobrevivem ao tempo. Jacques Le Goff (1990, p. 535) entende que

[...] o que sobrevive não é o conjunto daquilo que existiu no passado, mas uma escolha efetuada quer pelas forças que operam no desenvolvimento temporal do mundo e da humanidade, quer pelos que se dedicam à ciência do passado e do tempo que passa, os historiadores.

Estes materiais da memória podem apresentar-se sob duas formas principais: os monumentos, herança do passado, e os documentos, escolha do historiador.

Localizado na Praça dos Três Poderes, o Museu da Cidade projetado por Oscar Niemeyer serve de relicário de uma narrativa dos responsáveis pela materialização da cidade que em 1987 teve o seu Conjunto Urbanístico inscrito na Lista do Patrimônio Mundial da Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura (UNESCO). Nas suas paredes externas e internas estão esculpidos 19 textos relacionados com a criação de Brasília.

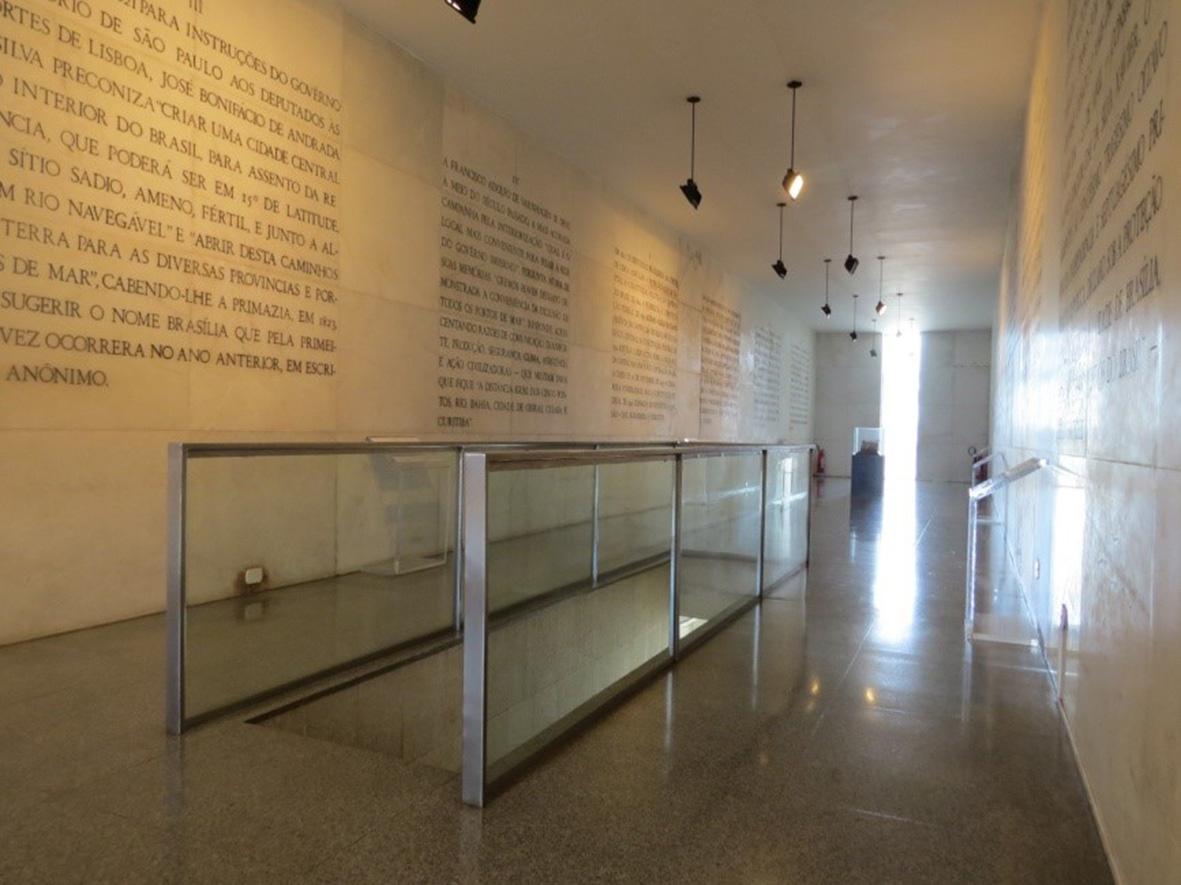

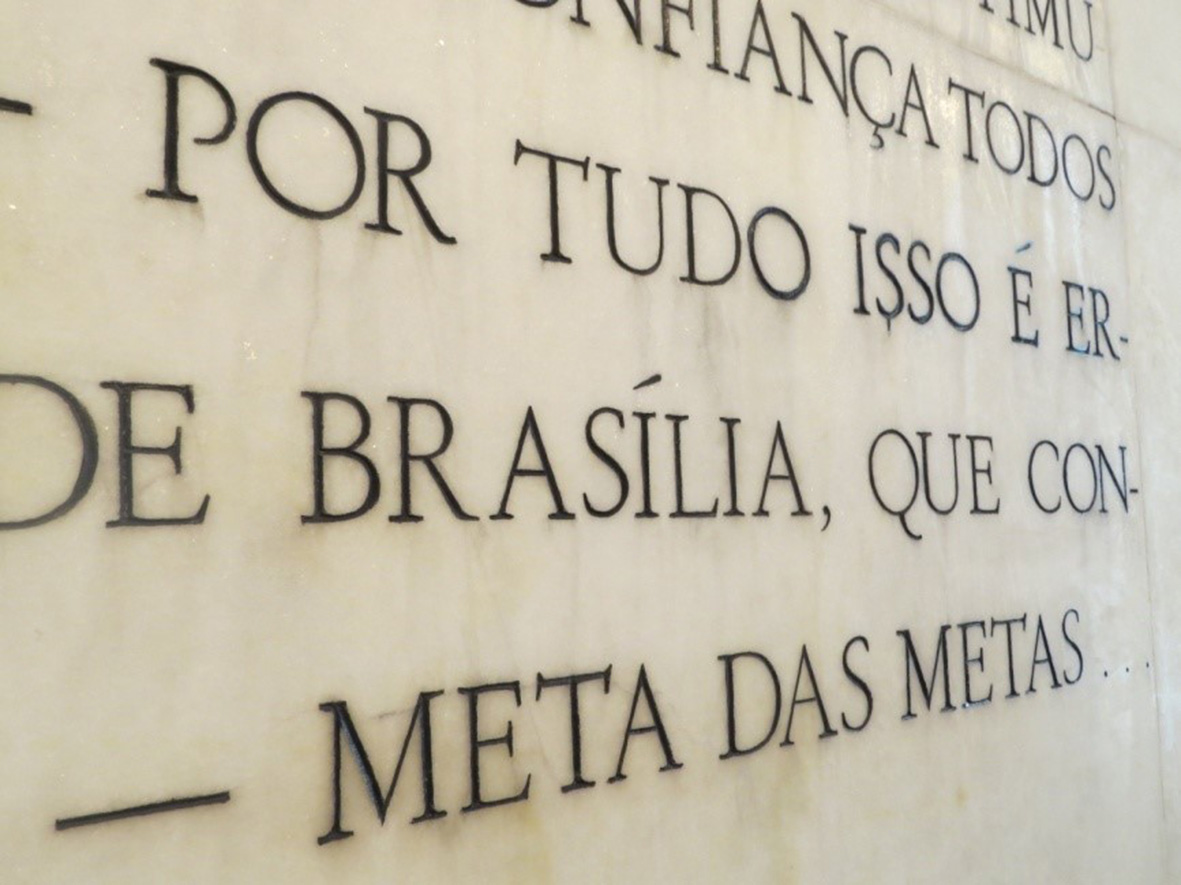

Fig. 2: Museu da Cidade, detalhe da inscrição do texto na área interna. Fonte: Eduardo Oliveira Soares, 2017.

O Museu da Cidade tem arquitetura singular: um pequeno monumento que contém um ambiente penetrável em cujos planos de vedação há textos gravados. O edifício, tombado pelo Governo do Distrito Federal (GDF) em 1982 e pelo Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (IPHAN) em 2007, serve de suporte de uma narrativa que intercala dados históricos, culturais e urbanísticos. O mote desta pesquisa é a avaliação do seu acervo museológico: os textos inscritos em suas paredes, que são indissociáveis da arquitetura do museu-monumento. Registrar e avaliar essa narrativa pode ampliar o conjunto de reflexões sobre o período de construção desta cidade que incorpora as diretrizes da arquitetura e do urbanismo modernos. Identificar novas fontes e refletir sobre elas subsidia o processo de educação patrimonial, registra a memória de uma época e contribui para a preservação dos bens culturais. Afinal, por meio do contato com o seu acervo o visitante tem acesso a uma narrativa sobre a cidade que influencia a avaliação da sua existência enquanto indivíduo e integrante da sociedade. Esse registro do passado contribui na constituição de uma memória individual e coletiva. E “a memória, como propriedade de conservar certas informações, remete-nos em primeiro lugar a um conjunto de funções psíquicas, graças às quais o homem pode atualizar impressões ou informações passadas, ou que ele representa como passadas” (LE GOFF, 1990, p. 423).

A metodologia utilizada para análise das narrativas foi a procura de mensagens e de nomes de personagens recorrentes nos diversos textos com o objetivo de identificar a lógica da narrativa existente nos painéis. A pesquisa1 está subdividida em tópicos que abordam (1) a arquitetura do Museu, (2) o conceito de narrativas e (3) as narrativas presentes no Museu da Cidade.

2 Algumas palavras sobre o museu da cidade

Monumentos arquitetônicos têm a intenção de perpetuar uma narrativa acerca de feitos considerados relevantes por seus construtores. Por meio da materialização – ou da criação – de um Lugar da Memória as conquistas, vitórias ou sacrifícios são inscritos na cidade e, por consequência, na memória social. José Guilherme Abreu entende que um Lugar da Memória pode se cristalizar em objetos, instrumentos ou instituições, sendo que ele começa “onde o mero registro acaba. Um lugar de memória é então o registro, mais aquilo que o transcende: o sentido simbólico ou emblemático inscrito no próprio registro” (ABREU, 2005, p. 219). Desde a antiguidade, obeliscos, esculturas, arcos do triunfo e monumentos cumprem esse papel.

O equipamento cultural que assume a função de guardião do Lugar da Memória é o museu. A Lei nº 11.904, de 14/01/1998, que institui o Estatuto de Museus, em seu Art. 1º considera museus como

[...] as instituições sem fins lucrativos que conservam, investigam, comunicam, interpretam e expõem, para fins de preservação, estudo, pesquisa, educação, contemplação e turismo, conjuntos e coleções de valor histórico, artístico, científico, técnico ou de qualquer outra natureza cultural, abertas ao público, a serviço da sociedade e de seu desenvolvimento (BRASIL, 1998, art. 1º).

Para registrar a construção de Brasília, Oscar Niemeyer criou um museu-monumento localizado na principal praça da cidade. O projeto do Museu da Cidade data de 1958, mesmo ano dos projetos do Palácio do Planalto, Congresso Nacional, Supremo Tribunal Federal, Ministérios (projeto padrão), Capela Nossa Senhora de Fátima, Casas Geminadas, Catedral e Teatro Nacional. O projeto de Museu já nesse momento inicial de propostas para a Nova Capital indica a relevância que foi dada à existência de um local que abrigaria acervo sobre a construção da cidade. Na grande velocidade de criação de novos edifícios em Brasília, nem todos os prédios originaram projetos executivos completos. Segundo publicação do Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional,

[...] muitos projetos de edifícios construídos na época da inauguração de Brasília não existem mais, foram perdidos; muitos edifícios não foram construídos exatamente como projetados, visto o curto tempo em que foram edificados; alguns edifícios, os menores, nem possuem projetos, mas apenas desenhos (como o Museu da Cidade) (IPHAN, 2009, p. 14).

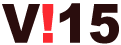

É por textos em periódicos e por imagens fotográficas da época da construção que é possível resgatar o processo de construção do Museu. Em artigo na revista Módulo nº 12, são apresentados croquis, texto e imagem da maquete do então denominado Museu de Brasília. É relatado que a construção se destinava a preservar trabalhos referentes à transferência da Nova Capital. Niemeyer afirma que "a forma plástica desse monumento, exprimindo por seu arrojo as possibilidades do concreto armado, atende, também, as características procuradas de sobriedade e beleza" (NIEMEYER, 1959, p. 36).

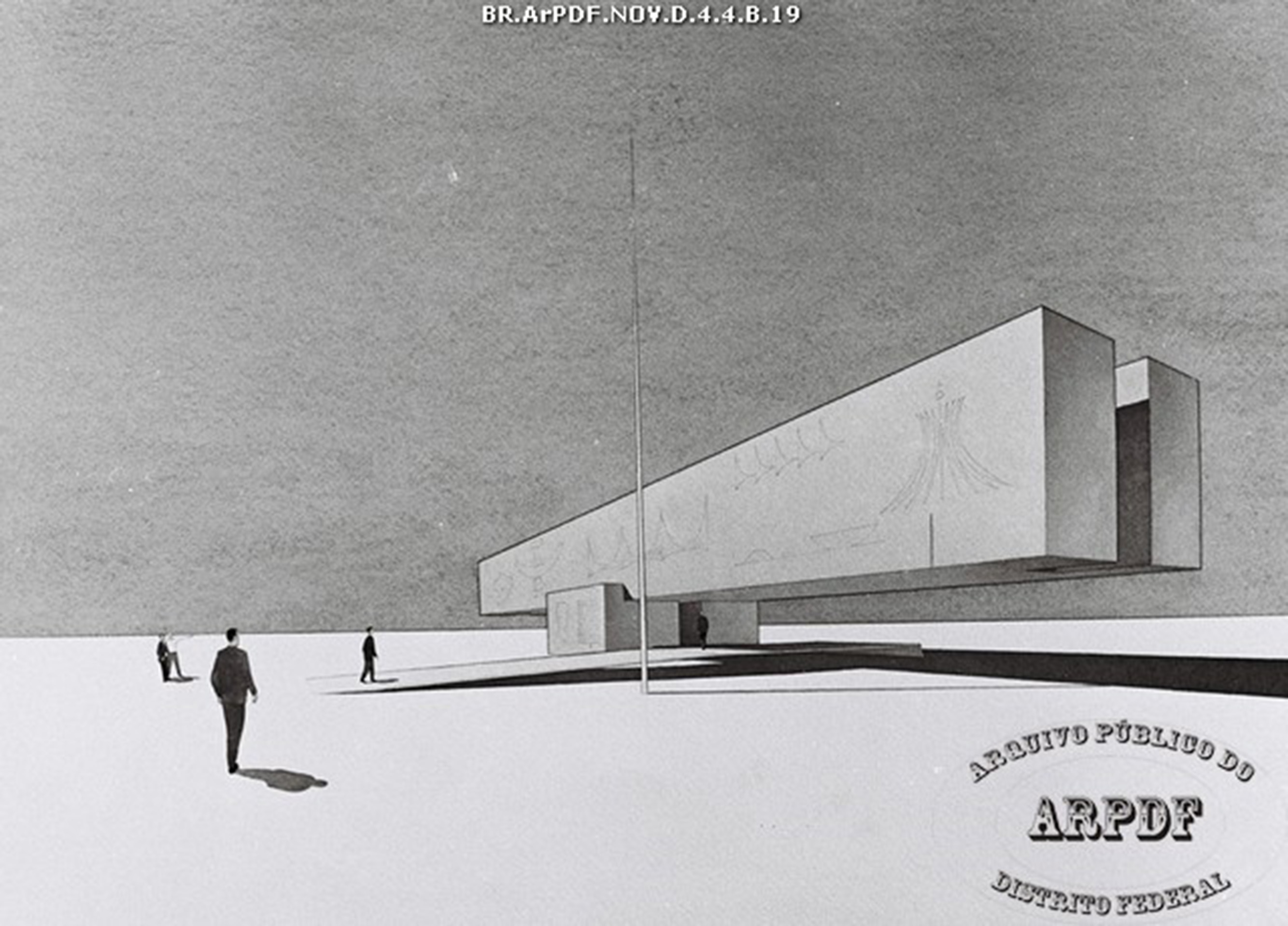

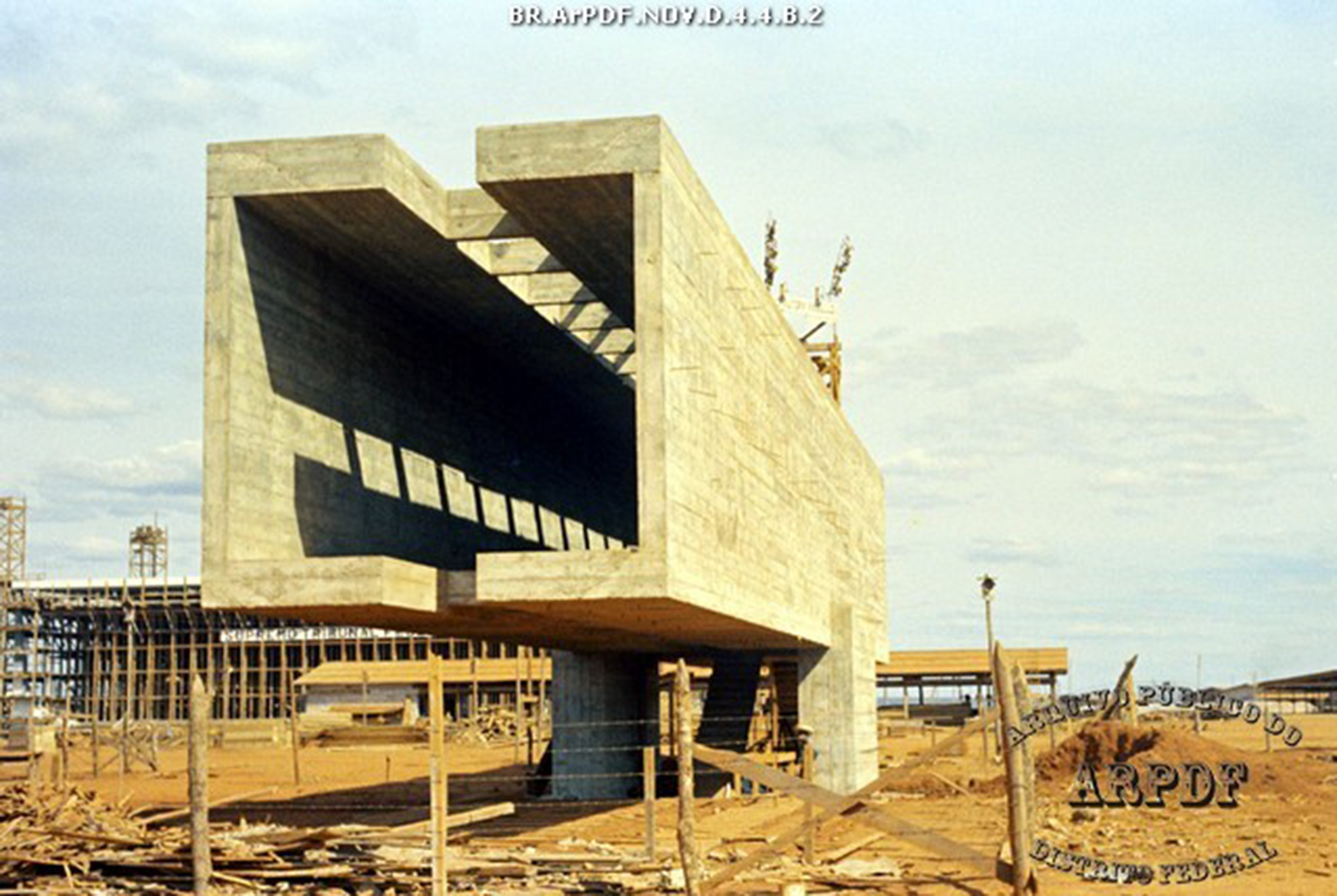

O edifício é constituído por um par de vigas que forma um bloco longitudinal de concreto armado com 5,00 m x 35,00 m de dimensões apoiado em um cubo que abriga a escada. Internamente o vão, situado entre duas vigas apoiadas em colunas-parede, receberia iluminação adequada devido à abertura no teto. Na revista Brasília nº 17 (1958) são apresentadas fotografias da maquete, com a fachada do museu coberta por croquis inspirados na arquitetura da cidade. Essas imagens (Fig. 3 e Fig. 4) também se encontram no acervo do Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal (ArPDF).

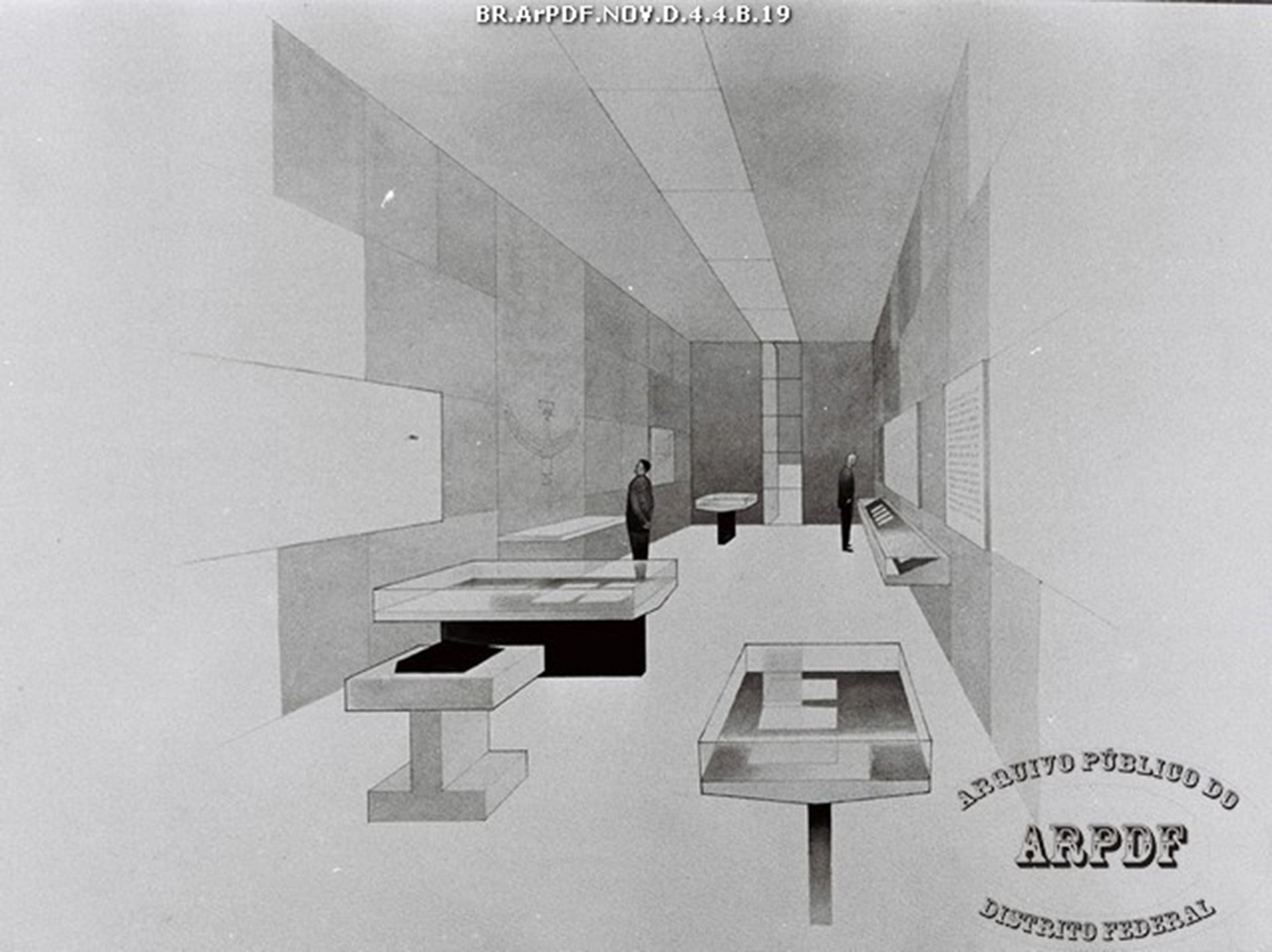

As obras do Museu da Cidade de Brasília (Fig. 5 e Fig. 6), sob a responsabilidade da Construtora Rabello S.A., foram realizadas de agosto de 1959 a abril de 1960. Sobre a inauguração do edifício, ocorrida em 21 de abril de 1960, Kubitschek relata:

À uma hora da tarde, encerrei o programa das solenidades daquela histórica manhã, inaugurando o marco que assinalava o nascimento de Brasília como capital da República. Tratava-se de um bloco de concreto, vestido de mármore, tendo em seu interior um modelo, da cidade, assim como um repositório de opiniões, emitidas pelas mais diversas personalidades, sobre Brasília. Ao monumento se incorporou, por iniciativa da generosidade de meus amigos, uma escultura, em granito, da minha cabeça e, ao lado, foi gravada uma inscrição (KUBITSCHEK, 2000, p. 383).

O Museu da Cidade foi objeto de reforma no ano de 1986, quando, conforme nota do periódico Correio Braziliense (07/09/86, p. 9), “foi totalmente reformado, principalmente no tocante às infiltrações". Nos anos de 1991 e 1997 também foram realizadas reformas no edifício.

O Museu abriga em sua base pequeno depósito e sanitário de acesso restrito aos funcionários. Estreita escada leva à sala no pavimento superior onde está o acervo. Diferente da proposta original, a sala de exposições não conta mais com iluminação zenital. Por meio do decreto nº 6.718 de 28 de abril de 1982 do Governo do Distrito Federal (1982) foi realizado o tombamento local. Em 2007, por ocasião do centenário de Niemeyer, ocorreu o início do processo de tombamento pelo IPHAN do Conjunto da Obra do arquiteto. O Processo 1550-T-07 foi concluído em 2017 e inclui o Museu da Cidade.

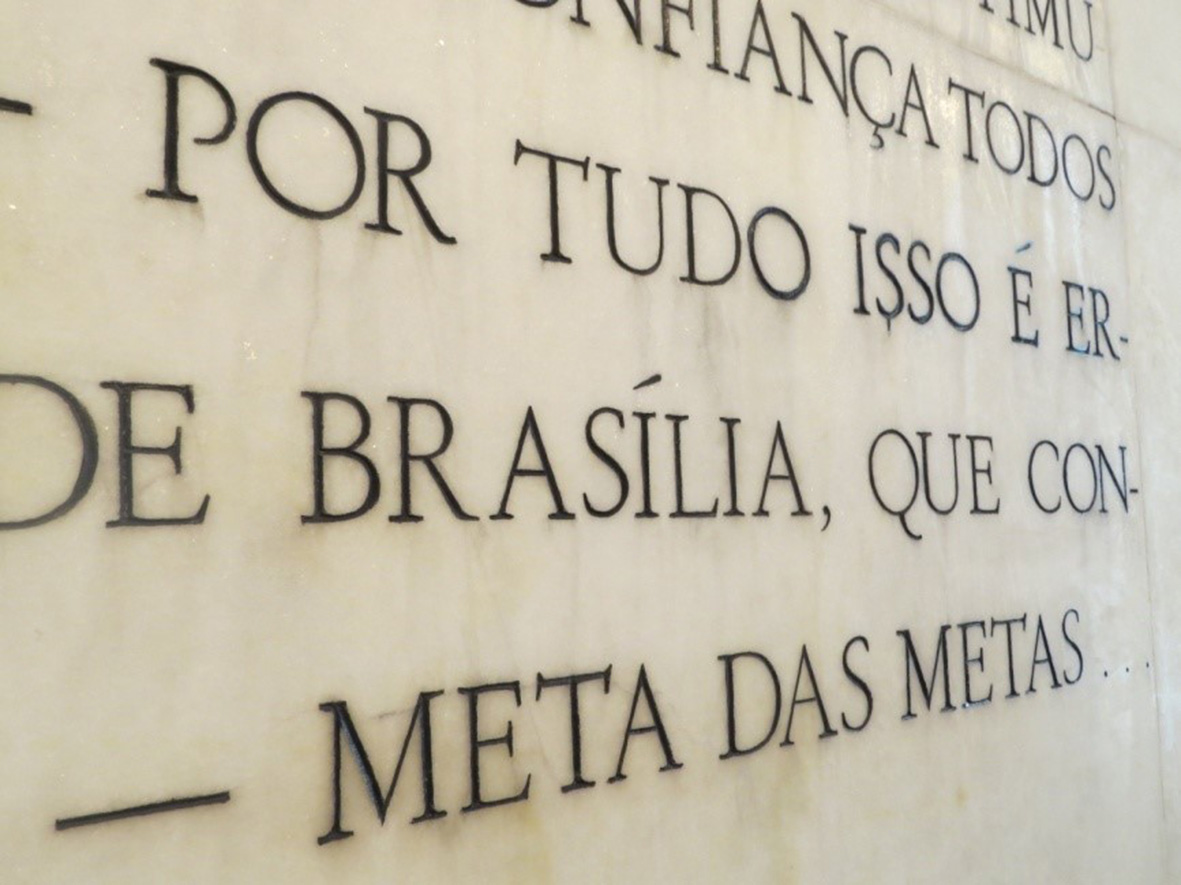

O elegante museu-monumento tem estrutura de concreto armado e revestimento em mármore branco de Cachoeiro do Itapemerim. Seu principal acervo é a efígie de Juscelino Kubitschek em pedra sabão de autoria de José Alves Pedrosa, os três textos esculpidos nas fachadas e os 16 esculpidos na sala interna. Não há registro da autoria da seleção dos textos que compõe a narrativa do museu. Registra-se que, diferente de versões preliminares (Fig. 3), não foram executados croquis nas paredes do edifício. Na Fachada Leste, visível do centro da Praça e direcionada para a alvorada há a célebre frase:

Deste Planalto Central, desta solidão que em breve se transformará em cérebro das altas decisões nacionais, lanço os olhos mais uma vez sobre o amanhã do meu país e antevejo esta alvorada com fé inquebrantável em seu grande destino.

Sobre a frase, Kubitschek relata que lhe ocorreu em sua primeira visita ao local de construção da Nova Capital. Na ocasião, em meio à mata do Gama e ao lado de um olho d’água, “[...] alguém trouxe-me um caderno, pomposamente denominado Livro de Ouro de Brasília, e me pediu que deixasse consignada na sua primeira página minha impressão da região” (KUBITSCHEK, 2000, p. 53). A frase também está gravada no hall de entrada do Palácio da Alvorada, inaugurado em 30 de junho de 1958.

Em catálogo lançado pela Presidência da República (circa 2006) após a reforma do edifício em 2006 o texto, também disponível no site da Presidência, é creditado ao poeta Augusto Frederico Schmidt. Ele teria sido o ponto alto do discurso que Juscelino Kubitschek proferiu no lançamento da pedra fundamental da Nova Capital da República em 2 de outubro de 1956. As diferentes versões do episódio revelam o quanto pode ser difícil verificar a autoria – e o processo de elaboração – de um acervo como o do Museu da Cidade.

Segundo nota do periódico carioca Última Hora (16/03/1960), ao ser perguntado por que resolveu repetir a frase que já constava no Palácio da Alvorada, ao invés de redigir uma nova, Kubitschek respondeu que “vou repetir a frase porque a que está gravada no Palácio da Alvorada poderá ser retirada no futuro... Aqui, entretanto, em Praça Pública, eles não poderão tirar. Porque o povo fiscaliza...". Desejoso de registrar em um monumento a sua versão da construção de Brasília, entalhada no mármore branco, Kubitschek revela o motivo da escolha daquele local – uma praça pública – para abrigar textos que sintetizam o processo de construção da cidade.

Esses relatos expressam a versão oficial que a Presidência da República queria passar para a posteridade. Ou seja, constituem narrativas para serem inseridas na historiografia da cidade e na memória de seus visitantes.

3 Algumas palavras sobre narrativas

Narrar é uma atividade intrínseca ao ser humano. A troca de informações por meio de relatos, descrições e reformulações, seja por meio oral, iconográfico ou escrito, está presente em todos os povos e culturas. Luiz Gonzaga Motta entende que “construímos nossa biografia e nossa identidade pessoal narrando. Nossas vidas são acontecimentos narrativos. O acontecer humano é uma sucessão temporal e casual. Vivemos as nossas relações conosco mesmos e com os outros narrando” (MOTTA, 2013, p. 17). Essa capacidade humana de expressão por meio de uma narrativa ou discurso levou à necessidade de elaboração de uma técnica que transcendesse o imediatismo da comunicação oral. Segundo Rita de Cássia Ribeiro de Queiroz, "a escrita é a contrapartida gráfica do discurso, é a fixação da linguagem falada numa forma permanente ou semipermanente. [...] O cuneiforme (do latim cuneus 'cunha', e forma 'forma') é o sistema mais antigo de escrita até hoje conhecido" (QUEIROZ, 2005, s.p.). Por volta de 3.500 a.C. essa escrita em pedra era utilizada pelos sumérios. Textos e desenhos eram encravados em elementos da arquitetura nos povos da antiguidade, como os assírios e egípcios.

Também data da antiguidade, do século IV a.C., a obra Poética de Aristóteles que é considerada a precursora no registro de uma sistematização das narrativas de então: a epopeia, o poema trágico, a comédia, o ditirambo. Para o desenvolvimento de fábulas, por exemplo, ele recomendava um único personagem que deve realizar uma ação com início, meio e fim, para que “não sejam os arranjos como das narrativas históricas, onde necessariamente se mostra, não uma ação única, senão um espaço de tempo, contando tudo quanto nele ocorreu a uma ou mais pessoas, ligado cada fato aos demais por um nexo apenas fortuito” (ARISTÓTELES, 1996 [330 a.C.], p. 54). A construção de um nexo entre uma simultaneidade de fatos e eventos com desfechos em aberto é, até hoje, característica de quem escreve uma narrativa histórica. Para Paul Veyne (1998, p. 18),

a história é uma narrativa de eventos: todo o resto resulta disso. Já que é, de fato, uma narrativa, ela não faz reviver esses eventos, assim como tampouco o faz o romance; o vivido, tal como ressai das mãos do historiador, não é o dos atores; é a narração, o que permite evitar alguns falsos problemas. Como o romance, a história seleciona, simplifica, organiza, faz com que um século caiba numa página, e essa síntese da narrativa é tão espontânea quanto a da nossa memória, quando evocamos os dez últimos anos que vivemos.

Veyne complementa que a narração pode ser realizada em primeira ou terceira pessoa e que enseja diferentes percepções de valor. Sucesso ou insucessos, fatos relevantes ou irrelevantes, são escolhas do narrador. Daí haver espaços para várias narrativas de um mesmo fato – como a explosão de um vulcão – ou evento – como uma batalha. Ao historiador cabe jogar luz sobre alguns acontecimentos do passado, interpretá-los e apresentá-los à sociedade atual e futura. Faz parte do seu ofício destacar alguns fatos considerados significativos e silenciar sobre tantos outros, relegando-os ao esquecimento. E também explorar fatos e eventos que, por algum motivo, não receberam atenção por parte de pesquisadores de outras gerações. Porém, o modo de redigir pode se assemelhar às obras de ficção.

Paul Ricoeur se dedicou a um percurso filosófico sobre a função narrativa e a experiência humana tanto na história como na ficção, analisando-as em separado. Mas também vê convergências nessas duas vertentes. Para ele, “o frágil rebento oriundo da união da história e da ficção é a atribuição a um Indivíduo ou a uma comunidade de uma identidade específica que podemos chamar de Identidade narrativa” (RICOEUR, 1997, p. 424). Ao narrarmos, elementos da vivência pessoal, da cultura, da história e da ficção naturalmente se mesclam. Com isso a afinidade de pessoas, grupos ou sociedade podem gerar narrativas semelhantes.

Na pesquisa histórica, fatos e eventos interessantes são descobertos e reinterpretados permanentemente. Porém, ao redor desses achados, muitas vezes há um vazio de informações que, para construção de narrativa coerente, requerem a criação de uma hipotética contextualização cuja comprovação nem sempre é possível. Seria então a criação de uma ficção? Avançando um pouco nessa lógica Ricoeur (1997, p. 428) afirma:

[...] poder-se-ia dizer que, na troca de papéis entre a história e a ficção, a componente histórica da narrativa sobre si mesmo puxa esta última para o lado de uma crônica submetida às mesmas verificações documentárias que qualquer outra narração histórica, ao passo que a componente ficcional a puxa para os lados das variações imaginativas que desestabilizam a identidade narrativa. Nesse sentido, a identidade narrativa não cessa de se fazer e de se desfazer [...].

mersa em narrativas ficcionais, a humanidade ao narrar seus acontecimentos assume papéis que na ficção cabem a personagens de diferentes vertentes. A ficção influencia o modo como cada um se vê e se expressa no mundo. Sobre as narrativas triviais da literatura, que envolve gêneros como dramas, tragédias e novelas, Flávio René Kothe entende que “sob a aparência de milhões de variantes em nível de estrutura e superfície, a narrativa trivial encena, em sua estrutura profunda, o ritual de eterna vitória do bem sobre o mal, definidos a priori, maniqueisticamente, sem maior discussão” (KOTHE, 1994, p. 7). Na comunicação entre interlocutores – onde cada um se apoia em uma identidade construída sobre narrativas próprias – a narrativa é uma constante criação e reinterpretação da realidade. Muitas vezes a percepção do que é baseado em fatos ou em ficção não é um consenso, pois essa distinção pode não ser tão evidente. Tratando-se da construção de uma nova cidade no então pouco habitado Centro Oeste brasileiro, a quantidade de versões sobre as conquistas e infortúnios da transferência foi grandiosa.

Brasília foi construída sob a empolgação e extenuante trabalho de seus apoiadores, mas também sob críticas de quem desconfiava de sua exequibilidade. Naquele fim da década de 1950 havia curiosidade sobre o desbravamento do cerrado e a materialização de um urbanismo e arquitetura inovadores. A construção foi amplamente registrada por reportagens, livros, fotografias e filmagens. Oscar Niemeyer, funcionário da Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (NOVACAP) e principal arquiteto, além de projetar e acompanhar as obras também respondia aos questionamentos, vindos principalmente da então capital, Rio de Janeiro, sobre o partido adotado nos edifícios. Em um relato do arquiteto publicado 11/03/1960 no periódico carioca Última Hora, intitulado Niemeyer responde às críticas sobre arquitetura de Brasília, há o seguinte depoimento do arquiteto:

Para uma coisa certas críticas são úteis. Construímos na Praça dos Três Poderes um monumento que vai documentar todos os obstáculos e incompreensões surgidos durante a construção de Brasília. Esses obstáculos e incompreensões ajudam melhor a compreender, na medida precisa, o valor da obra realizada pelo Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek. Ali, no momumento-museu, essas críticas vão ser conservadas. E o tempo nos dirá depois se são justas ou se são o que eu penso delas (ÚLTIMA HORA, 1960).

Ao recordar a intensa agenda de eventos do dia da inauguração da cidade, Kubitschek cita que o Museu da Cidade “destinava-se a guardar todos os documentos referentes à epopeia de Brasília. Tudo quanto se escrevera a favor ou contra a nova capital já ali estava depositado, aguardando o julgamento frio da História” (KUBITSCHEK, 2000, p. 388). Alvos de dúvidas sobre a pertinência e capacidade operacional da mudança da capital, os responsáveis pela criação da cidade acharam por bem, desde o momento de sua inauguração, registrar uma narrativa histórica sobre os eventos – e supostas incompreensões – que a cercaram. Esses relatos estão gravados em pedra no Museu da Cidade.

4 As palavras inscritas na pedra

Os textos que compõem a narrativa do Museu da Cidade estão esculpidos, em letras de caixa alta, no mármore branco das fachadas e das paredes internas do edifício. Na documentação historiográfica não foi localizado o nome do responsável pela seleção do acervo. A análise dessas narrativas foi realizada a partir da procura de recorrências nas mensagens dos diversos textos, da identificação da repetição de nomes de alguns personagens, e da verificação se elas contêm o registro das oposições e resistências à construção da cidade, como frisaram Kubitschek e Niemeyer. Com isso foi possível avaliar a mensagem que o conjunto museológico transmite. O acervo se divide em dois grupos: o da área externa (Fig. 7) e o da área interna à edificação.

Na área externa, a Fachada Leste está direcionada para a Praça dos Três Poderes, podendo ser considerada a face principal, pois, inclusive, é nela que está inserida a efígie de Juscelino Kubitschek. Nesta fachada, junto à escultura, há texto, creditado aos pioneiros, que homenageia o presidente. Ao lado há a repetição da frase inscrita no hall de entrada do Palácio da Alvorada. Na Fachada Oeste, encontra-se uma cronologia indicando seis datas. A primeira se refere a 1789, citando os Inconfidentes, e a última é sobre o dia de inauguração de Brasília e do próprio Museu.

A frase em homenagem a Kubitschek, junto à escultura, é de mensagem dúbia, pois não esclarece se está relacionada à efígie ou ao edifício como um todo. Pode ser interpretada que a efígie é uma homenagem dos pioneiros ao Presidente, ou o próprio museu. Esse conjunto com três textos destaca a importância do então Presidente, cujo nome é repetido cinco vezes. Além dele o único nome citado é o do Deputado Israel Pinheiro da Silva. A menção à Inconfidência Mineira situa Brasília como desdobramento do pensamento de interiorização da capital registrado ainda no Século XVIII. Nas fachadas externas não há referência aos opositores do projeto de mudança da capital, nem das dificuldades enfrentadas para a construção de Brasília. As três mensagens são distintas: homenagem à Kubitschek, frase do Presidente e cronologia.

Na área interna (Fig. 8) do edifício há 16 textos numerados, que constituem o acervo museológico permanente. Desde a reforma de 1986 também estão transcritos para braille. Além deles, há somente pequena vitrine utilizada para a exposição temporária de objetos.

O Texto I inicia com “ANTE O PERIGO EXTERNO E PARA PRESERVAR A INTEGRIDADE DA CAPITANIA NA UNIDADE DO PAÍS [...]”. A primeira data mencionada é de 1761, ano em que o Marquês de Pombal idealiza erguer uma nova capital. O Texto II trata da Inconfidência Mineira e evoca frase atribuída a Tiradentes, desejoso de que houvesse a mudança da capital e que nela houvesse locais para estudos, como em Coimbra. No Texto III há resgate das notas de José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva sobre a interiorização da Capital e de sua primazia de sugerir o nome “Brasília”. O Texto IV registra o desejo de mudança do Governo Imperial para um local longe dos portos de mar. No Texto V há a continuação da cronologia da defesa da interiorização da Capital, que se encerra com a Constituição Federal de 1946, que “CONSAGRA EM DEFINITIVO A DECISÃO QUE AGUARDARIA O EXECUTOR”.

A campanha eleitoral à presidência de 1955, quando o então candidato Kubitschek trava “VIVO DIÁLOGO COM O POVO” é o tema do Texto VI. Nele há o registro da intenção do candidato em cumprir a Carta Magna integralmente, inclusive no seu propósito de mudança da Capital. O Texto VII registra a mensagem do presidente Kubitschek ao Congresso Nacional iniciando os trâmites legais para a construção da Nova Capital. A constituição da NOVACAP e o Edital para o Concurso do Plano Piloto da cidade é o tema do Texto VIII.

No Texto IX há trechos do plano de Lucio Costa, que concebeu uma cidade "NÃO APENAS COMO URBS, MAS COMO CIVITAS". O Texto X reproduz mensagem ao povo brasileiro enviada pelo Papa Pio XII. O Texto XI destaca a lei que fixa a data de mudança da Capital. No Texto XII há relato de Niemeyer que cita a luta “CONTRA A OPOSIÇÃO OBSTINADA”. O Texto XIII apresenta uma exaltação de Kubitschek aos candangos – os trabalhadores imigrantes que construíram a capital. O Texto XIV, também com a assinatura do Presidente, registra trecho do discurso de inauguração de Brasília. Nos Textos XV e XVI, por fim, há mensagem enaltecendo Kubitschek “PORQUE SUPEROU COM VIGOR INDOMÁVEL TODAS AS CRÍTICAS ICONOCLASTAS”. O conjunto dos textos finda com o apelo que seja explicado aos filhos o motivo da existência dessa “[...] CIDADE SÍNTESE, PRENÚNCIO DE UMA REVOLUÇÃO FECUNDA EM PROSPERIDADE. ELES É QUE NOS HÃO DE JULGAR AMANHÔ.

O conjunto dos 16 textos da parte interna do Museu da Cidade repete o nome de Kubitschek cinco vezes. Além dele, são nomeados mais 19 personagens, sendo que dentre eles somente o de Niemeyer é repetido duas vezes. Classificando os textos por conteúdo verifica-se que seis citam realizações e discursos do Presidente, cinco relatam os antecedentes da Nova Capital, e dois são de homenagens à Kubitschek. Completa o conjunto a apresentação de trecho do plano piloto de Lucio Costa, a síntese da experiência em Brasília por Oscar Niemeyer e a mensagem do Papa Pio XII.

Considerando todo o conjunto dos 19 textos, localizados nas fachadas e paredes do interior do Museu, percebe-se que a categoria que reúne maior número de textos é a que enaltece e registra os êxitos do Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek. A segunda categoria, em termos quantitativos, é a que reúne o registro dos antecedentes de Brasília. Somente em dois trechos há referências às dificuldades impostas pela oposição política à realização da mudança da Capital.

Como é característico nos relatos históricos, os textos – tantos internos quantos externos – inscritos no Museu da Cidade resumem um longo trecho da história de Brasília, e do Brasil, em uma narrativa criada a partir de quem o concebeu: no caso a Presidência da República. Os textos do Museu privilegiam a identificação de Kubitschek como o principal nome responsável pela mudança da Capital e a inserção de Brasília em uma longa cronologia, respaldada por várias Constituições, que trata a sua construção como fruto de um anseio da nação.

Depois da inauguração da cidade vários presidentes ocuparam o Palácio do Planalto, uns com mais, outros com menos cumplicidade com o povo. Os descendentes da geração que testemunhou o surgimento da cidade contam com inúmeras versões, em diferentes formatos, para a construção de Brasília. Porém a narrativa que permanece acessível a quem visita a Praça dos Três Poderes é a do Museu da Cidade. Afinal, como afirma Aleida Assmann, locais desse tipo podem “tornar-se sujeitos, portadores de recordação e possivelmente dotados de uma memória que ultrapassa amplamente a memória dos seres humanos” (ASSMANN, 2011, p. 317). Com isso, conforme pretendia Kubitschek, essa narrativa vai sobrevivendo ao esquecimento.

5 Considerações finais

O Museu da Cidade tem a característica peculiar de ser um museu-monumento – tipo de edificação escassa na contemporaneidade. Os artigos em periódicos e os registros iconográficos gerados no momento de sua projetação e construção foram imprescindíveis para a criação de um conjunto documental que possibilita o resgate do seu processo de criação e contribui para a transmissão da memória sobre os primórdios da cidade.

A elaboração do projeto do Museu no mesmo ano que outros edifícios-chave da cidade revela a preocupação dos construtores de Brasília em criar um Lugar da Memória que registrasse o processo de mudança da Capital. É interessante observar que a opção pelo modo de apresentação de seu acervo museológico siga o modo mais antigo de escrita: a cuneiforme. Esses textos esculpidos em suas paredes, como nos monumentos e obeliscos milenares, registram a grande saga que foi a construção de Brasília na praça que é ponto de encontro e de manifestações da metrópole e também local de maior simbolismo político do país. Narrativa – à vista do povo – sobre a criação de uma cidade que é Urbs, Civitas e Patrimônio Mundial da Humanidade.

Referências

ABREU, J. G. Arte pública e lugares de memória. Revista da Faculdade de Letras Ciências e Técnicas do Património, Porto, v. 4, p. 215-234, 2005.

ARISTÓTELES. Poética. São Paulo: Nova Cultural, 1996. Escrito em cerca de 330 a.C.

ASSMANN, A. Espaços de recordação: formas e transformações da memória cultural. São Paulo: Unicamp, 2011.

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.904, de 14/01/1998. Institui o Estatuto de Museus e dá outras providências. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l11904.htm>. Acesso em: 05 Out.2017.

CORREIO BRAZILIENSE. Museu da Cidade reabre mudado. Brasília, p. 9, 1986.

COSTA, L. Relatório do Plano Piloto de Brasília. 1957. In: Governo do Distrito Federal. Relatório do Plano Piloto de Brasília. Brasília: GDF, 1991. p. 18-34.

IPHAN. Patrimônio no DF: bens tombados. Brasília: Superintendência do Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional no Distrito Federal, 2009.

KOTHE, F. A narrativa trivial. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília, 1994.

KUBITSCHEK, J. Por que construí Brasília. Brasília: Senado Federal/Conselho Editorial, 2000.

LE GOFF, J. História e memória. Campinas: Unicamp, 1990.

MOTTA, L. G. Análise crítica da narrativa. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília, 2013.

NIEMEYER, O. Museu de Brasília. Revista Módulo, v. 2, n. 12, p. 36-37, Fev. 1959.

PRESIDÊNCIA da República. Catálogo do Palácio da Alvorada. Brasília: Coordenação de Relações Públicas, circa 2006.

PRESIDÊNCIA da República. Palácios e Residências Oficiais. 22 Set. 2011. [Site] Disponível em: <http://www2.planalto.gov.br/presidencia/palacios-e-residencias-oficiais/palacio-da-alvorada/galeria-de-imagens/palacio-da-alvorada-12.jpg/view>. Acesso em: 05 Out. 2017.

QUEIROZ, R. C. R. A informação escrita: do manuscrito ao texto virtual. In: CINFORM - ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE CIÊNCIA DA INFORMAÇÃO, 6., Salvador, 2005. Anais...

RICOEUR, P. Tempo e narrativa 3: O tempo narrado. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 1997.

ÚLTIMA HORA. Na hora H José Mauro, a frase do Alvorada. Rio de Janeiro, 16 Mar. 1960.

ÚLTIMA HORA. Niemeyer responde às críticas sobre arquitetura de Brasília, Moacir Werneck de Castro. Rio de Janeiro,1960.

REVISTA BRASÍLIA, v. 2, n. 17, Mai. 1958.

VEYNE, P. Como se escreve a história e Foucault revoluciona a história. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília, 1998.

1 Artigo desenvolvido como parte de pesquisa de doutorado no Programa de Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo (PPG/FAU) da Universidade de Brasília (UnB). Versão deste texto foi apresentado no 12º Seminário DOCOMOMO Brasil.

The narrative of the city museum: Brasília inscribed on stone

Eduardo Oliveira Soares is architect and urban planner. He is researcher at Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, at Brasília University (UnB). He studies photographic narratives on the University Campus Darcy Ribeiro.

How to quote this text: Soares, E., 2017. The narrative of the City Museum: Brasília inscribed on stone V!RUS, 15. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=4&item=7&lang=en>. [Accessed: 02 July 2025].

Abstract

The Three Powers Square, in Brasília, houses the City Museum, a building that is listed monument both locally and nationally. The monument-museum was designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1958 and inaugurated in 1960 with the purpose of being a Place of Memory. Its collection is composed of cuneiform texts that present a narrative about the process that originated the city and the persons who made it viable. In visiting the museum, one accesses a narrative that influences the evaluation of one's own experience as an individual and participant of the society. Thus, this record of the past also contributes to the construction of an individual and collective memory. In order to evaluating the museum's collection - which is inseparable from its architecture - the article is structured in three parts: rescuing the trajectory of the building´s design, reflecting on concepts of narratives and, finally, reading and analyzing the texts recorded on the walls. The Museum's panels favor the identification of President Juscelino Kubitschek as the main person responsible for changing the Capital and the insertion of Brasília in a long chronology that presents its construction as resulting from a yearning of the nation.

Keywords: Brasilia, Narrative, Heritage

1 Introduction

The inauguration of a planned city marks the end of a cycle of idealization, planning, design and construction. In Brasilia, a new capital inaugurated in 1960, there was extensive records of its conception, through reports, books, photographs and filming. Some discourses highlight the development and entrepreneurship of that moment, others the precarious working and housing conditions of the labor force that built the city or the impacts of the cost of construction for the country. These stories contextualize, under different approaches, the creation of this city that was able to materialize the architecture and urbanism thinking of that time.

Relatório do Plano Piloto by Lucio Costa (1957, p.18, our translation) begins with ellipses, and then elegantly synthesizes the antecedents of the city: "[...] José Bonifácio proposes in 1823 to transfer the Capital to Goiás and suggests the name of BRASÍLIA". Juscelino Kubitschek's (2000) publication, Why I built Brasilia, records the history, construction, inauguration and unfolding of the city's implantation process in a massive work of almost 500 pages. They are singular visions, since the former authored the urban plan of the city and the latter was the President of the Republic in whose mandate the city was built. However, all records are ways of perceiving, experiencing and reporting become unique, giving rise to the various narratives.

When it comes to the narrative of an event or historical fact, the content will never be obvious or unique. For each version presented there are other infinite possibilities, including one hiding certain passages. Similar to Lucio Costa's short phrase mentioned above, there is in Brasilia a small museum-monument (Fig. 1) inaugurated by Juscelino Kubitschek on the same day the Capital was transferred (Fig. 2). The administration's desire to communicate and record their achievements and deeds commonly produces artifacts that survive time. Jacques Le Goff (1990, p.535, our translation) understands that

‘[...] what survives is not the whole of what has existed in the past, but a choice made either by the forces operating in the temporal development of the world and humanity, or by those who devote themselves to the science of the past and the time that passes, historians.

These materials of memory can present themselves in two main forms: monuments, heritage of the past, and documents, historian's choice’.

Located in the the Three Powers Square, the City Museum designed by Oscar Niemeyer serves as reliquary of a narrative of those responsible for the materialization of the city which was inscribed, in 1987, in the List of World Heritage of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), in 1987. On its external and internal walls are carved 19 texts related Brasilia´s creation.

Fig. 2: City Museum, detail of inscription in the internal area. Source: Eduardo Oliveira Soares, 2017.

The City Museum has singular architecture: a small monument that contains a penetrable environment in which walls are recorded texts. The building, registered by the Government of the Federal District (GDF) in 1982 and by the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN) in 2007, supports a narrative that intertwines historical, cultural and urban information. The motto of this research is the evaluation of its museological collection: the texts inscribed on its walls, which are inseparable from the museum-monument architecture. Recording and evaluating this narrative can broaden the set of reflections on the period of construction of this city that incorporates the guidelines of modern architecture and urbanism. Identifying new sources and reflecting on them subsidizes the patrimonial education process, records the memory of an era, and contributes to the preservation of its cultural assets. After all, in visiting the Museum one has access to a narrative about the city that influences the evaluation of its experience as an individual and member of of society. This record of the past contributes to the constitution of an individual and collective memory. And "memory, as the property of preserving certain information, refers us first to a set of psychic functions, by which man can actualize past impressions or information, or whatever he represents as past” (Le Goff, 1990, p.423, our translation).

The methodology used to analyze the narratives was the search for messages and names of recurring persons in the various texts in order to identify the logic of the narrative in the panels. The research1 is subdivided into topics that address (1) the architecture of the Museum, (2) the concept of narratives and (3) the narratives present in the City Museum.

2 Some words about the city museum

Architectural Monuments intends to perpetuate a narrative about deeds considered relevant by their builders. Through the materialization - or creation - of a Place of Memory, the achievements, victories or sacrifices are inscribed in the city and, consequently, in the social memory. According to José Guilherme Abreu a Place of Memory can crystallize itself in objects, instruments or institutions, and it begins "where the mere record ends. Therefore a place of memory is the register, plus whatever transcends it: the symbolic or emblematic meaning inscribed in the register itself" (Abreu, 2005, p.219, our translation). From ancient times, obelisks, sculptures, triumphal arches and monuments fulfill this role.

The cultural equipment that assumes the role of guardian of the Place of Memory is the museum. Law 11,904, dated 01/14/1998, which establishes the Statute of Museums, in its Article 1 defines museums as

‘non-profit institutions that preserve, investigate, communicate, interpret and display, for the purpose of preservation, study, research, education, contemplation and tourism, settings and collections of historical, artistic, scientific, technical or other cultural, open to the public, at the service of society and its development’ (BRASIL, 1998, art. 1, our translation).

In order to register the construction of Brasília, Oscar Niemeyer created a museum-monument located in the main square of the city. The City Museum project dates back to 1958, the same year as the Planalto Palace, National Congress, Federal Supreme Court, Ministries (standard project), Our Lady of Fatima Chapel, Twin Houses, Catholic Cathedral and National Theater. The Museum project already in that initial moment of proposals for the New Capital indicates the relevance that was given to the existence of a place that would house collection on the construction of the city. In the great speed of construction of new buildings in Brasilia, not all of them had complete executive projects. According to a publication of the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute,

[...] many projects of buildings constructed at the time of the inauguration of Brasilia no longer exist, were lost; many buildings were not built exactly as designed, given the short time they were built; some buildings, the smaller ones, do not have projects, but only drawings (such as the City Museum) (IPHAN, 2009, p.14, our translation).

Texts in periodicals and photographic images of the time of the construction make possible to rescue the process of construction of the Museum. An an article in the magazine Módulo 12 presented sketches, text, and image of the model of the then called Museum of Brasília. It is reported that the construction was intended to preserve works relating to the transfer of the New Capital. Niemeyer states that "the plastic form of this monument, expressing by its boldness the possibilities of reinforced concrete, also responds to the characteristics sought for sobriety and beauty" (Niemeyer, 1959, p.36, our translation).

The building consists of a pair of beams that forms a longitudinal block of reinforced concrete with 5.00 m x 35.00 m of dimensions supported on a cube that houses the staircase. Internally the span, set between two beams supported on wall-columns, would receive adequate lighting due to the opening in the ceiling. In the magazine Brasilia 17 (1958) presented photographs of the model, with the facade of the museum covered by sketches inspired by the architecture of the city. These images (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) are also found in the archives of the Public Archive of the Federal District (ArPDF).

The construction of the City Museum of Brasília (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6), under the responsibility of Construtora Rabello SA, were carried out from August 1959 to April 1960. On the inauguration of the building, on April 21, 1960, Kubitschek states:

‘At one o'clock in the afternoon, I closed the program of the solemnities of that historic morning, inaugurating the landmark that marked the birth of Brasilia as the capital of the Republic. It was a concrete block, dressed in marble, with a model of the city, as well as a repository of opinions, emitted by the most diverse personalities, about Brasilia. To the monument, on the initiative of the generosity of my friends, a granite sculpture was added to my head and, next to it, an inscription was engraved’ (KUBITSCHEK, 2000:383, our translation).

The City Museum was reformed in 1986, when, according to the newspaper Correio Braziliense (07/09/86, p.9, our translation), "it has been totally reformed, especially with regard to infiltration". In 1991 and 1997 renovations were carried out in the building.

The Museum houses in its base small deposit and restroom to which only employees have access. Narrow staircase leads to the living room on the upper floor where the collection is. Unlike the original proposal, the exhibition room no longer has zenith lighting. The Decree 6.718 of April 28, 1982 of the Government of the Federal District (1982) listed the building as a preserved monument in 2007, on the occasion of the centenary of Niemeyer, the IPHAN initiated proceedings (Process 155-T-07) to include the whole architect work as national preserved monument, whith was completed in 2017, including in it the City Museum.

The elegant monument-museum features reinforced concrete structure and white marble from Cachoeiro do Itapemerim. The effigy of Juscelino Kubitschek sculped in soapstone by Jose Alves Pedrosa, the three texts carved in the facades and the 16 sculpted in the inner room are its main collection. There is no record of the authorship of the selection of texts that compose the narrative of the museum. It is noted that, unlike preliminary versions (Fig. 3), no sketches were executed on the walls of the building. In the East Facade, visible from the center of the Square and directed towards the dawn, there is the celebrated phrase:

‘From this central plateau, of this solitude that soon will become the brain of the high national decisions, I cast my eyes once again upon the tomorrow of my country and I foresee this dawn with unbreakable faith in its great destiny’.

About the phrase, Kubitschek reports that it occurred to him on his first visit to the construction site of the New Capital. At the time, in the midst of the Gama forest and next to a watercourse, "[...] someone brought me a notebook, pompously called the Golden Book of Brasilia, and asked me to leave it on the front page my impression of the region" (Kubitschek, 2000, p.53, our translation). The phrase is also recorded in the entrance hall of the Alvorada Palace, inaugurated on June 30, 1958.

In a catalog launched by the Presidency of the Republic (circa 2006) after the 2006 renovation of the building, the text, also available on the Presidency website, is credited to the poet Augusto Frederico Schmidt. It would have been the high point of the speech that Juscelino Kubitschek delivered at the foundation stone of the New Capital of the Republic on October 2, 1956. The different versions of the episode reveal how difficult it can be to verify authorship - and the process of elaboration - of a work such as the City Museum.

According to a note from the Última Hora (03/16/1960, our translation), a Rio de Janeiro newspaper, when asked why he decided to repeat the phrase that was already in the Alvorada Palace, instead of writing a new one, Kubitschek replied that "I will repeat the phrase because the one engraved in the Alvorada Palace may be withdrawn in the future ... Here, however, in Public Square, it can not be deleted, they can not take it. Because the people will keep it on watch..." Aiming to register in a monument his version of the Brasilia construction, carved in white marble, Kubitschek reveals the reason for choosing that place - a public square - to house texts that synthesize the construction process of the city.

These reports express the official version that the Presidency of the Republic wanted to pass on to posterity. That is, they constitute narratives to be inserted in the historiography of the city and in the memory of its visitors.

3 Some words about narratives

Narrating is a human being intrinsic activity. The exchange of information through reports, descriptions and reformulations, whether oral, iconographic or written, is present in all peoples and cultures. For Luiz Gonzaga Motta "we build our biography and our personal identity by narrating. Our lives are narrative events. Human happening is a temporal and casual succession. We live our relationships with ourselves and with others narrating" (Motta, 2013, p.17, our translation). This human capacity for expression through a narrative or discourse led to the need to elaborate a technique that transcended the immediacy of oral communication. According to Rita de Cássia Ribeiro de Queiroz, "writing is the graphical counterpart of discourse, it is the fixation of spoken language in a permanent or semi-permanent form [...] The cuneiform (from the Latin cuneus 'wedge', and forma 'form') is the earliest known writing system to date" (Queiroz, 2005, s.d., our translation). Around 3,500 BC this stone writing was used by the Sumerians. Texts and drawings were embedded in elements of architecture in ancient peoples, such as the Assyrians and Egyptians.

Also dateing from antiquity, from the fourth century BC, the Poetic work of Aristotle is considered the precursor in the record of a systematization of the narratives of the time: the epic, the tragic poem, the comedy, the dithyramb. For the development of fables, for example, he recommended a single character who must perform an action with beginning, middle and end, so that "it is not the arrangements as of historical narratives, where necessarily it is shown, not a single action, but a time, counting all that took place in it to one or more persons, connected each fact to the others by a fortuitous nexus" (Aristóteles, 1996 [330b.C.], p.54, our translation). Elaborating a nexus between a simultaneity of facts and events with open endings is, to this day, characteristic of whoever writes a historical narrative. For Paul Veyne (1998, p.18, our translation)

history is a narrative of events: everything else comes out of it. Since it is, in fact, a narrative, it does not revive these events, nor does the novel; the lived, as it survives from the hands of the historian, is not that of the actors; is the narration, which allows to avoid some false problems. Like romance, history selects, simplifies, organizes, makes a century fit on a page, and this synthesis of the narrative is as spontaneous as that of our memory, as we recall the last ten years we live.

Veyne complements that the narration can be realized in first or third person and that it brings about different perceptions of value. Success or failures, relevant or irrelevant facts, are choices of the narrator. Hence there are spaces for various narratives of the same fact - like the explosion of a volcano - or event - as a battle. It is the historian's job to shed light on some past events, to interpret them and present them to present and future society. It is part of his office to highlight some facts considered significant and to silence about so many others, relegating them to oblivion. And also explore facts and events that, for some reason, have not received attention from researchers of other generations. However, the manner of writing may resemble works of fiction.

Paul Ricoeur devoted himself to a philosophical course on narrative function and human experience in both history and fiction, analyzing them separately. But it also sees convergences in these two strands. For him, "the fragile offspring from the union of history and fiction is the attribution to an Individual or a community of a specific identity that we can call the narrative Identity" (Ricoeur, 1997, p.424, our translation). As we narrate, elements of personal experience, culture, history and fiction naturally blend. With this the affinity of people, groups or society can generate similar narratives.

In historical research, interesting facts and events are discovered and reinterpreted permanently. However, around these findings, there is often a lack of information that, in order to construct a coherent narrative, requires the creation of a hypothetical contextualization whose proof is not always possible. Was it then the creation of a fiction? Advancing this logic a little Ricoeur (1997, p.24, our translation) says:

[...] one could say that in the exchange of roles between history and fiction the historical component of the narrative about itself pulls the latter to the side of a chronicle subjected to the same documentary checks as any other narration historical, while the fictional component pulls it sideways from the imaginative variations that destabilize narrative identity. In this sense, narrative identity does not cease to be done and discarded [...].

Immersed in fictional narratives, humanity in narrating its events assumes roles that in fiction fit characters from different strands. Fiction influences the way one sees and expresses himself in the world. On the trivial narratives of literature, which involve genres such as dramas, tragedies and novels, Flávio René Kothe understands that "in the appearance of millions of variants at the level of structure and surface, the trivial narrative enacts, in its deep structure, the ritual of eternal victory of good over evil, defined a priori, maniqueistically, without further discussion" (Kothe, 1994, p.7, our translation). In the communication between interlocutors - where each one is based on an identity built on own narratives - the narrative is a constant creation and reinterpretation of the reality. Often the perception of what is based on fact or fiction is not a consensus, as this distinction may not be so obvious. As for the construction of a new city in the then little-inhabited Central West of Brazil, the number of versions on the achievements and misfortunes of the transfer was great.

Brasília was built under the excitement and strenuous work of its supporters, but also under the criticism of those who suspected its feasibility. At the end of the 1950s there was curiosity about the savannah's exploration and the materialization of an innovative urbanism and architecture. The construction was largely recorded by reports, books, photographs and filming. Oscar Niemeyer, an employee of the Urbanization Company of the New Capital of Brazil (NOVACAP) and principal architect, besides designing and monitoring the works, also responded to the questions, mainly coming from the then capital, Rio de Janeiro, about the approach adopted in the buildings. In an architect's account published 03/11/1960 in the Última Hora, a Rio de Janeiro periodical, titled Niemeyer responds to the criticisms about architecture of Brasília, there is the following testimony of the architect:

For one thing some criticisms are helpful. We built in the Three Powers Square a monument that will document all the obstacles and misunderstandings that arose during the construction of Brasilia. These obstacles and misunderstandings help us better understand, to the extent necessary, the value of the work carried out by President Juscelino Kubitschek. There, in the monument-museum, these criticisms will be preserved. And time will tell us later whether they are fair or whether they are what I think of them (ÚLTIMA HORA, 1960, s.p., our translation).

In recalling the intense agenda of events on the day of the inauguration of the city, Kubitschek cites that the City Museum "was intended to keep all documents referring to the epic of Brasília. All that had been written for or against the new capital was already deposited there, awaiting the cold judgment of history" (Kubitschek, 2000, p.388, our translation). Targets of doubts about the pertinence and operational capacity of the capital's change, those responsible for the creation of the city considered, from the moment of its inauguration, to record a historical narrative about the events - and supposed misunderstandings - that surrounded it. These accounts are engraved in stone at the City Museum.

4 The words inscribed on stone

The texts that compose the narrative of the City Museum are carved in upper case letters on the white marble of the facades and the internal walls of the building. The name of the person responsible for selecting the collection was not found in the historiographical documentation. The analysis of these narratives was based on the search for recurrences in the messages of the various texts, the identification of the repetition of names of some characters, and the verification if they contain the record of oppositions and resistance to the construction of the city, as Kubitschek and Niemeyer had pointed out. Thus, it was possible to evaluate the message that the museological set conveys. The collection is divided into two groups: that of the external area (Fig. 7) and that of the internal area to the building.

In the external area, the East Facade is directed to the Three Powers Square, and can be considered the main face, since in it is inserted the effigy of Juscelino Kubitschek. In this façade, next to the sculpture, there is text, credited to the pioneers, that honors the president. Next to it is the repetition of the phrase inscribed in the entrance hall of the Alvorada Palace. In the West Facade, there is a chronology indicating six dates. The first refers to 1789, citing the Inconfidentes, and the last one is about the inauguration day of Brasilia and the Museum itself.

The phrase in honor of Kubitschek, next to the sculpture, is of dubious message, because it does not clarify if it is related to the effigy or to the building as a whole. It can be interpreted that the effigy is a homage of the pioneers to the President, or to the museum itself. This set of three texts highlights the importance of the then President, whose name is repeated five times. In addition, Representative Israel Pinheiro da Silva is the only other name mentioned. The mention of the Inconfidência Mineira places Brasília as an extension of the thought of interiorization of the capital registered in the 18th century. In the exterior façades there is no reference to opponents of the capital's change project, nor to the difficulties faced for the construction of Brasília. The three messages are distinct: homage to Kubitschek, President's phrase and chronology.

In the inner area (Fig. 8) of the building there are 16 numbered texts, which constitute the permanent museological collection. Since the reform of 1986 they have been translated also into Braille. Besides them, there is only a small window used for the temporary exhibition of objects.

Text I begins with "FACING OUTWARD HAZARD AND IN ORDER TO PRESERVE THE INTEGRITY OF THE CAPITANIA IN THE COUNTRY UNIT [...]". The first mentioned date is 1761, year in which Marquês de Pombal idealizes to built a new capital. Text II is related to the Inconfidência Mineira and evokes phrase attributed to Tiradentes, whom wished that there should be a change of capital in which there should be places for study, as in Coimbra. In Text III there is a recollection of the notes of José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva on the interiorization of the Capital, and his primacy to suggesting the name "Brasília". Text IV records the Imperial Government's desire for change to a place far from the seaports. In Text V there is a continuation of the chronology of the defense of the internalization of the Capital, which ends with the Federal Constitution of 1946, which "AFFIRMS IN DEFINITIVE THE DECISION THAT WILL WAIT ITS EXECUTOR."

The election campaign for the 1955 presidency, when then-candidate Kubitschek holds "LIVE DIALOGUE WITH THE PEOPLE" is the theme of Text VI. It contains the record of the candidate's intention to comply fully with the Constitution, including its purpose of changing the Capital. Text VII records the message of President Kubitschek to the National Congress initiating the legal procedures for the construction of the New Capital. The formation of NOVACAP and the Call for Bid for the Pilot Plan of the city is the theme of Text VIII.

In Text IX there are excerpts from the plan by Lucio Costa, who conceived a city "NOT ONLY AS URBS, BUT AS CIVITAS". Text X reproduces a message to the Brazilian people sent by Pope Pius XII. Text XI highlights the law that sets the date of change of the Capital. In Text XII there is Niemeyer's account that cites the struggle "AGAINST OBSTINATED OPPOSITION". Text XIII presents an exaltation of Kubitschek to the candangos - the immigrant workers who built the capital. The Text XIV, also with the signature of the President, records an excerpt from the speech of inauguration of Brasília. In Texts XV and XVI, finally, there is a message extolling Kubitschek "BECAUSE IT EXCEEDED WITH INDOMABLE VIGOR ALL ICONOCLASTAS CRITICS". The whole of the texts ends with the appeal that explains to the children the reason for the existence of this "[...] CITY SYNTHESIS, PRONUNCIATION OF A REVOLUTION FOUND IN PROSPERITY. THEY THAT ARE US TO JUDGE TOMORROW ".

The set of 16 texts from the inner part of the City Museum repeats the name of Kubitschek five times. Besides him, 19 more characters are named, and among them only Niemeyer's is repeated twice. Classifying the texts by content, it is verified that six cites achievements and speeches of the President, five report the antecedents of the New Capital, and two are tributes to the Kubitschek. Complete the set the presentation of excerpt from the pilot plan of Lucio Costa, the synthesis of experience in Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer and the message from Pope Pius XII.

Considering the whole set of 19 texts, located on the facades and walls of the interior of the Museum, it can be seen that the category that brings together the greatest number of texts is the one that praises and records the successes of President Juscelino Kubitschek. The second category, in quantitative terms, is the one that gathers the history record of Brasília. Only in two passages are there any references to the difficulties imposed by the political opposition to the Capital's moving.

As it is characteristic in historical accounts, the texts - both internal and external - inscribed in the City Museum summarize a long passage in the history of Brasilia, and of Brazil, in a narrative created from the one who conceived it: in this case, the Presidency of the Republic . The texts of the Museum privilege the identification of Kubitschek as the main name responsible for the change of the Capital and the insertion of Brasilia in a long chronology, backed by several Constitutions, which treats its construction as the fruit of a yearning of the nation.

After the inauguration of the city several presidents occupied the Palace of the Planalto, some with more, others with less complicity with the town. The descendants of the generation that witnessed the emergence of the city count on innumerable versions, in different formats, for the construction of Brasilia. But the narrative that remains accessible to those who visit the Three Powers Square is that of the City Museum. After all, as Aleida Assmann asserts, such sites can "become subjects, bearers of memory and possibly endowed with a memory that goes far beyond the memory of human beings" (Assman, 2011, p.317, our translation). With this, as Kubitschek intended, this narrative survives oblivion.

5 Final Considerations

The Museum of the City has the peculiar characteristic of being a museum-monument - type of building scarce in the contemporaneity. The articles in periodicals and the iconographic registers generated at the time of its design and construction were essential for the creation of a documentation that allows the rescue of its creation process and contributes to the transmission of memory about the beginnings of the city.

The elaboration of the Museum project in the same year as other key buildings in the city reveals the concern of the builders of Brasília in creating a Place of Memory that registers the process of change of the Capital. It is interesting to note that the option for the presentation mode of its museum collection follows the oldest mode of writing: the cuneiform. The texts carved on its walls, as in the monuments and millennial obelisks, record the great saga that was the construction of Brasília in the square that is a meeting point and manifestations of the metropolis and also place of greater political symbolism of the country. Narrative - in the sight of the people - about the creation of a city that is Urbs, Civitas and World Heritage.

References

Abreu, J. G., 2005. Arte pública e lugares de memória. Revista da Faculdade de Letras CIÊNCIAS E TÉCNICAS DO PATRIMÓNIO, (4), pp.215-234.

Aristóteles, 1996. Poética. São Paulo: Nova Cultural. Written around 330 a.C.

Assman, A., 2011. Espaços de recordação: formas e transformações da memória cultural. São Paulo: Unicamp.

Brasil, 1998. Lei nº 11.904, de 14/01/1998. Institui o Estatuto de Museus e dá outras providências. Available at: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l11904.htm> [Accessed 05 October 2017].

Correio Braziliense, 1986. Museu da Cidade reabre mudado. Brasília, p.9.

Costa, L., 1957. Relatório do Plano Piloto de Brasília. In: Governo do Distrito Federal, ed. 1991. Relatório do Plano Piloto de Brasília. Brasília: GDF, 1991. pp.18-34.

IPHAN, 2009. Patrimônio no DF: bens tombados. Brasília: Superintendência do Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional no Distrito Federal.

Kothe, F., 1994. A narrativa trivial. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília.

Kubitschek, J., 2000. Por que construí Brasília. Brasília: Senado Federal/Conselho Editorial.

Le Goff, J., 1990. História e memória. Campinas: Unicamp.

Motta, L. G., 2013. Análise crítica da narrativa. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília.

Niemeyer, O., 1959. Museu de Brasília. Revista Módulo, (2)12, pp.36-37.

Presidência da República, circa 2006. Catálogo do Palácio da Alvorada. Brasília: Coordenação de Relações Públicas.

Presidência da República, 2011. Palácios e Residências Oficiais. 22nd September. [Site] Available at: <http://www2.planalto.gov.br/presidencia/palacios-e-residencias-oficiais/palacio-da-alvorada/galeria-de-imagens/palacio-da-alvorada-12.jpg/view> [Accessed 05 October 2017].

Queiroz, R. C. R., 2005. A informação escrita: do manuscrito ao texto virtual. In: 6th CINFORM - Encontro Nacional de Ciência da Informação, Salvador, 2005. Proceedings...

Ricoeur, P., 1997. Tempo e narrativa 3: O tempo narrado. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes.

Última Hora, 1960. Na hora H José Mauro, a frase do Alvorada. Rio de Janeiro, 16th March.

Última Hora, 1960. Niemeyer responde às críticas sobre arquitetura de Brasília, Moacir Werneck de Castro. Rio de Janeiro.

Revista Brasília, 1958. (2)17, May.

Veyne, P., 1998. Como se escreve a história e Foucault revoluciona a história. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília.

1This paper is part of a doctoral research for the Graduate Program of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism (PPG/FAU) of the University of Brasília (UnB). A version of this paper was presented at the 12th Seminar DOCOMOMO Brazil.