Educação e memória: métodos e experiências digitais

Jessica Aline Tardivo é arte educadora, pedagoga e arquiteta, Mestre em Educação e pesquisadora de doutorado do Nomads.usp. Estuda a aplicação da metodologia de Educação Patrimonial associada às novas tecnologias com o propósito de facilitar a identificação da herança cultural de uma cidade.

Anja Pratschke é arquiteta e Doutora em Ciências da Computação, professora e pesquisadora do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo e Co-coordenadora do Nomads.usp. Desenvolve e orienta pesquisas nas áreas de processos de design e comunicação em arquitetura.

Como citar esse texto: TARDIVO, J; PRATSCHKE, A.. Educação e memória: métodos e experiências digitais.V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 15, 2017. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=6&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 03 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Este artigo apresenta possibilidades educativas mediadas por meios digitais que facilitam a aproximação entre os indivíduos e os bens culturais, trazendo à tona o resgate da memória e novas interpretações sobre a cidade. Com esse objetivo, inicialmente foi abordado o lugar da memória na cidade atual. Em seguida, apresentam-se as ações de Educação Patrimonial associadas às novas tecnologias de comunicação como recurso na construção da memória. Por fim, avalia-se o uso de interfaces interativas, acessadas a partir da leitura de QR Codes, e a produção de Fotocolagens que vem sendo empregadas em pesquisas sobre o patrimônio cultural pelo grupo de pesquisa Nomads.usp.1

Palavras-chave: Cidade, Educação patrimonial, Memória, Mídias digitais

1A memória na cidade atual

Antes de conjecturar o lugar da memória na cidade atual, faz-se necessário refletir sobre o porquê da memória e qual o seu papel social. É possível verificar em diversas escritas a memória da cidade tomando o papel da identidade do lugar, por isso é importante esclarecer que no estudo do presente artigo, adotando como referência a pesquisa do sociólogo francês Joel Candau, publicada na obra “Memória e Identidade”2 no ano de 1998, compreende-se a memória como um conjunto de narrativas que reportam as lembranças afetivas e históricas. Conectando o passado ao presente e possibilitando projeções futuras de um povo ou lugar, enquanto a identidade é composta pelas escolhas que se faz a partir dos conhecimentos adquiridos.

A identidade cultural de um lugar e o modo de vida de um povo, se constitui a partir dos bens culturais, histórias e manifestações que um grupo escolhe preservar e vai se modificando de acordo com os hábitos de diferentes gerações, enquanto a memória é um aporte para que tudo o que foi construído, produzido e aprendido é possível de resgatar ao longo do tempo.

Voltando-se especificamente para memória na antiguidade, por exemplo, a imagem real junto com a imagem mnemônica da cidade auxiliava o indivíduo a se localizar entre o passado e o presente. De acordo com o historiador americano Antony Vidler (1992, p. 177):

Na cidade tradicional, antiga, medieval ou renascentista, a memória urbana era fácil de definir. Foi essa imagem da cidade que permitiu ao cidadão identificar seu passado e presente como uma entidade política, cultural e social (nem a "realidade" da cidade nem uma "utopia" puramente imaginária, mas em vez disso um mapa mental complexo de significado; daí o lugar privilegiado dos monumentos como marcadores no tecido da cidade3 (Tradução nossa).

A historiadora inglesa Frances Yates descreveu, em sua obra a “Arte da Memória”4 (1976), diferentes e elaboradas técnicas de memorização utilizadas durante todo o período da idade média e renascimento, que auxiliavam o indivíduo a lembrar de contextos históricos e literários, a se localizarem no espaço tempo. Muitas dessas técnicas se davam pela memorização de lugares físicos e imaginários, cujas partes de cada espaço deveriam ser compostas ou preenchidas mentalmente, pelas informações que cada pessoa desejava lembrar. A memória se dava não apenas como lembrança da tradição, mas como techné5 ou mnemotécnica, processos que passam a ser reconhecidos como a Arte da Memória (FLUSSER, 1983 p. 83).

Na cidade de hoje, fazer a leitura de lugares, construir mapas mnemônicos ou reconhecer uma identidade local, torna-se muito mais complexo, uma vez que os indivíduos têm acesso a redes de comunicação e informação, conseguindo de forma rápida pesquisar contextos históricos, mapas de localização, entre outros, o que diminui a necessidade de memorizar. Tais redes, possibilitam, ainda, o contato com diversas manifestações culturais, religiosas e políticas, de tal modo cada pessoa pode escolher entre os hábitos e costumes aqueles que melhor atendem suas expectativas e objetivos. Esse é um dos fatores que torna o mapa mnemônico da cidade atual uma sobreposição de identidades culturais.

A arquiteta israelense e especialista em história da cidade contemporânea Tali Hatuka, apresenta uma visão ainda mais complexa, refletindo que:

Múltiplos mapas sincrônicos sobrepostos uns sobre os outros estão sendo criados na cidade de hoje, em um processo interminável. De fato, alguns desses mapas de memória não durarão por muito tempo. Não há muitos agentes ativos para mantê-los ou conservá-los nas mentes das pessoas nem capital significativo para manter sua existência no espaço físico (HATUKA, 2017, p. 51).

Hatuka (2017, p. 51) questiona o que será esquecido e o que será preservado em relação a cultura da cidade de hoje? Uma possível resposta seria pensar que ao se abordar uma época em que o povo vivência histórias múltiplas e consciências sociais diferentes, deve-se perceber que a memória não é estática, ela se transforma com o tempo, assim como a identidade.

Hatuka (2017, p. 51) apresenta uma visão crítica em relação a bens e manifestações culturais como produto de mercado, quando a arquiteta reforça a inexistência do “capital” para preservação da memória. Sobre essa visão, conclui-se que se em tese as estruturas reconhecidas como bens culturais são preservadas apenas a partir de registros e tombamentos, administrados por políticas de preservação, e esses bens se tornam atrativo turístico local, sim, pode-se concordar que não há recursos viáveis para a preservação de diferentes manifestações no espaço físico.

No entanto, entende-se aqui que os diferentes manifestos se modificam e fazem parte do conjunto cultural de uma cidade de tal modo, acredita-se que ações formais e informais, atividades educativas e leituras diferenciadas da cidade, registradas pelas artes, disposta em obras literárias, fotografias, filmes e documentários, permitem o registro, leitura e a interpretação da memória na cidade hoje.

De fato, as primeiras iniciativas de aproximação entre a população e os bens culturais aconteceram de forma efetiva em espaços formais, sobretudo na Europa quando os espaços expositivos de museus e galerias passam a ser vistos como lugar de aprendizagem e adotam métodos didáticos para apresentar o conteúdo aos visitantes, conforme cita a educadora inglesa Eilean Greenhill Hooper (2001, p. 52):

Na década de 1960, museus tornarem-se lugares de aprendizagem ativa. Já não é mais suficiente colecionar, conservar e investigar, mas tais operações converteram-se em meios para alcançar outro fim que são pessoas e suas relações com os objetos. Por outras palavras, o centro da atenção deixa de ser a coleção para ser a comunicação, na qual a aprendizagem e o lazer são integrados6 (Tradução nossa).

Para facilitar o processo educativo e reflexivo criou-se, primeiramente na Inglaterra, uma categoria de profissionais, os educadores de museus, que vão atuar como interlocutores entre o público visitante e os bens expostos (HOOPER, 2001, p. 40-54).

É também nesse período, que surge na França uma abordagem historiográfica conhecida por Nova História ou Nova História Cultural. Inserida no ensino formal de toda Europa, como Educação Patrimonial, a mesma tinha como objetivo propiciar um aprendizado ‘[...] centrado no objeto cultural, na evidência material da cultura[...]”, e baseava-se em “[...] um processo educacional que considera o objeto como fonte primária de ensino” (ALENCAR, 1987, p. 26).

Essa prática de ensino permitia que os estudantes tivessem um contato inicial com os bens culturais para que depois pudessem aferir os dados históricos com maior autonomia e criticidade. Contudo, as vivências ao longo da década de 1990 não se restringem apenas aos espaços expositivos, mas começam a permear os monumentos e lugares da cidade. Concomitantemente, manifestações artísticas, como exemplo as Neo-vanguardas7, passaram a interpretar e experimentar de maneira diferenciada os espaços da cidade.

2 Educação Patrimonial: recursos e tecnologias da memória

No Brasil, a Educação Patrimonial foi inserida nas práticas educativas do museu Imperial do Rio de Janeiro pela museóloga Maria de Lourdes Horta no ano de 1985, e depois sistematizada pela mesma em quatro etapas de aplicação, a saber: (1) observação, (2) registro, (3) exploração e (4) apropriação8, as quais foram dispostas em um guia publicado pelo IPHAN no ano de 1999.

O objetivo do IPHAN, era utilizar a metodologia como instrumento de formação cultural, visando aproximar a sociedade do patrimônio material, sobretudo nas práticas de ensino formal. Na atualidade, o método se tornou base para as ações educativas, formais e informais do IPHAN, que envolvem o patrimônio cultural como um todo. (IPHAN, 2014 p. 13).

No final da década 1990, também se inicia o processo de popularização do uso das redes de comunicação e informação, viabilizados pelo acesso à rede de internet. Esse avanço veio facilitar a projeção e inserção de atividades em plataformas interativas, como os museus virtuais, jogos e acervos coletivos, dando início a outros espaços de registro da memória cultural, inseridos no ciberespaço.

De acordo com o filósofo Pierre Levy (1993, p. 28), a configuração do “saber e das práticas educativas e socioculturais se dão a partir da estrutura da linguagem e das tecnologias de inteligência” que se destacam em um processo de retroalimentação, e se modificam conforme são utilizadas. Sobre essa ótica, os pesquisadores brasileiros, especialistas em comunicação e memória social, João Nunes e Paola Oliveira relatam (2016, p. 96):

Ao mesmo tempo em que a era da informática inaugurou um potencial ainda maior para nossa inteligência, ela também causou uma revolução nos processos de seleção, armazenamento e disponibilização dos suportes de memória, que, funcionando como extensões artificiais da cognição, tornam possível a transmissão memorial. A dinâmica da memória e do esquecimento fica cada vez mais evidente no universo virtual, uma vez que a gestão da memória e do conhecimento é compartilhada na web e seu acesso depende, quase que exclusivamente, da atualização de hardwares e softwares.

A partir desta observação entende-se que os meios digitais abrigam diferentes possibilidades de divulgação do conhecimento, da memória e da história, e o ciberespaço promoveu a ruptura das barreiras e limites impostos pelo espaço/tempo. Conquanto, sua sustentação depende do compartilhamento constante de informações. Para Nunes e Oliveira (2016, p .99):

Se antes os lugares das pinturas parietais, na Caverna de Chauve, os afrescos na Capela Sistina, as esculturas e pinturas renascentistas nos museus e galerias e os textos dos arquivos e bibliotecas eram considerados por excelência, a cada época, os “lugares de memória” destinados ao armazenamento, circulação e fruição dos nossos referenciais visuais, suportes simbólicos de memória, hoje esse lugar, no ciberespaço, é “todo o lugar”.

As primeiras experiências em torno do uso do ciberespaço e de recursos tecnológicos como meio e suporte da memória cultural, avançaram em meados dos anos 2010 devido ao refinamento da programação computacional, que tornou possível o acesso em 360º a bens e objetos culturais (NUNES; OLIVEIRA, 2016). Na atualidade, a facilidade do uso de dispositivos móveis, como celulares e tablets, que permitem a conexão com a rede de internet, instalação de aplicativos, entre outros, abriu espaço para o uso da Realidade Virtual e Aumentada (uma simulação em tempo real de modificação do espaço) e dos QR Codes (códigos que permitem a conexão dos dispositivos móveis com interfaces diversas).

Algumas instituições, espaços de museus e organizações privadas vêm utilizando esses recursos com sucesso em suas ações educativas, como exemplo o projeto Videoguía: Realidade Aumentada e Virtual, implantando desde o ano de 2012 na Casa Batló em Barcelona, Espanha, pelo grupo de pesquisa Artec9, do Instituto de Robótica e Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação de Valência.

O projeto Videoguía: Realidade Aumentada e Virtual foi desenvolvido com o objetivo de proporcionar a interatividade entre o visitante e o ambiente físico. O sistema consiste em um dispositivo móvel no qual está instalado um aplicativo que exibe os objetos e as configurações espaciais originais das salas de exposições, incluindo elementos audiovisuais e objetos virtuais 3D com os quais o público pode interagir. As salas da edificação são identificadas no aplicativo por números, e ao acessar o número correspondente, basta o usuário posicionar o dispositivo em direção à sala real para visualizar o lugar e os objetos em tempos e situações diferenciadas, como exposto pela Fig. 1.

Este sistema possibilitou ao museu a construção de um novo processo educativo, uma vez que o vídeo-guia dispõe de informações sobre patrimônio, história, geografia e cultura. Para Gimeno et al. (2012, p. 8)

Este sistema tem melhorado a assimilação do conhecimento dos visitantes de uma maneira divertida, incentivando a prática de exploração de pontos de interesse e a colaboração e discussão entre os participantes. Em suma, se tem criado uma ferramenta de comunicação e de aprendizagem com um alto grau de imersão (tradução nossa).10

Por esse exemplo, o uso da tecnologia tem facilitado as dinâmicas e práticas educativas em torno da memória, porém custos como rede de internet, manutenção e compra de equipamentos, produção de aplicativos, entre outros, dificultam o acesso a essas diferentes dinâmicas. Desse modo, os atrativos interativos têm sido utilizados geralmente em instituições privadas como museus, grandes eventos e exposições.

3 Ações interativas para leitura e interpretações da memória da cidade

Tentando viabilizar as ações educativas, as temáticas de projetos do grupo de pesquisa Nomads.usp têm abarcado diferentes estudos com caráter transdisciplinar que buscam uma abertura para que grupos e comunidades possam conhecer, refletir e desenvolver discussões críticas sobre a cidade. No que se refere a memória, investigam-se possibilidades de uso de meios digitais e recursos audiovisuais para a observação, divulgação, preservação e gestão do patrimônio cultural na contemporaneidade. A fim de ilustrar esse processo, debruçasse aqui sobre dois projetos em fase de implementação: (1) Percursos Virtuais: Colaborações em Narrativas do patrimônio Cultural de São Carlos, que tem como suporte interfaces interativas acessadas por meio de QR Codes, e (2) Educação Patrimonial: Desafios e Estratégias na Cultura Digital, que experimenta o uso de Foto colagens digitais na construção de novas paisagens urbanas.

O (1) projeto Percursos Virtuais: Colaborações em Narrativas do patrimônio Cultural de São Carlos, surgiu a partir de uma parceria, no ano de 2017, entre a Fundação Pró-Memória da cidade de São Carlos e o grupo de pesquisa com objetivo de desenvolver atividades educativas e interativas, propondo como recurso a utilização de dispositivos móveis (celulares e tablets), direcionada para o conhecimento e divulgação da história do patrimônio arquitetônico da cidade.

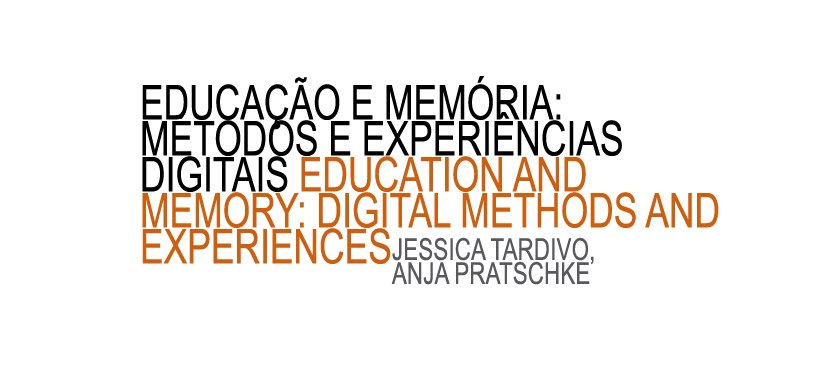

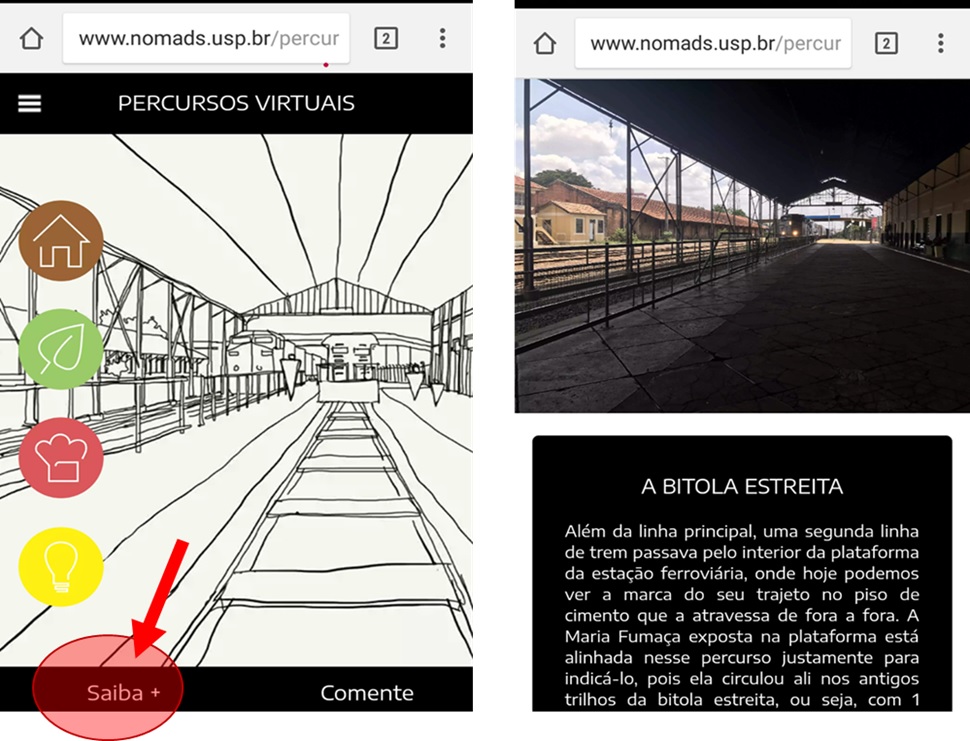

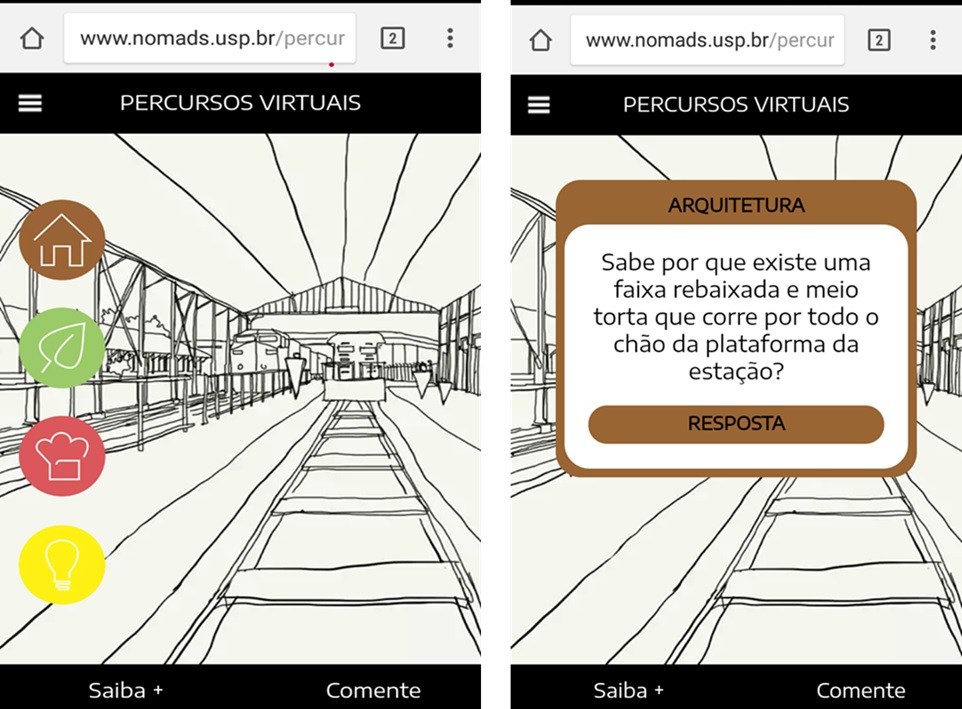

Analisando os dois recursos tecnológicos disponíveis, o projeto empenhou-se em criar um roteiro de aprendizagem mediado pelo uso de QR Codes que serão fixados nas edificações de relevância histórica da cidade, inicialmente, locados como piloto nos espaços da Estação Ferroviária11 de São Carlos. O sistema prevê a interatividade entre o prédio e o usuário, que ao posicionar o dispositivo móvel sobre o QR Code será direcionado para uma interface interativa12 que disponibilizará informações e curiosidades sobre o lugar por intermédio de perguntas e respostas, como exposto pela Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Interface do projeto Percursos Virtuais. Desenho da Interface: Sandra Schmitt Soster; Sketches: Maria Clara Cardoso; Desenvolvimento de Web: Maria Vitória do Nascimento Inocencio. Fonte: Arquivo do Projeto, 2017.

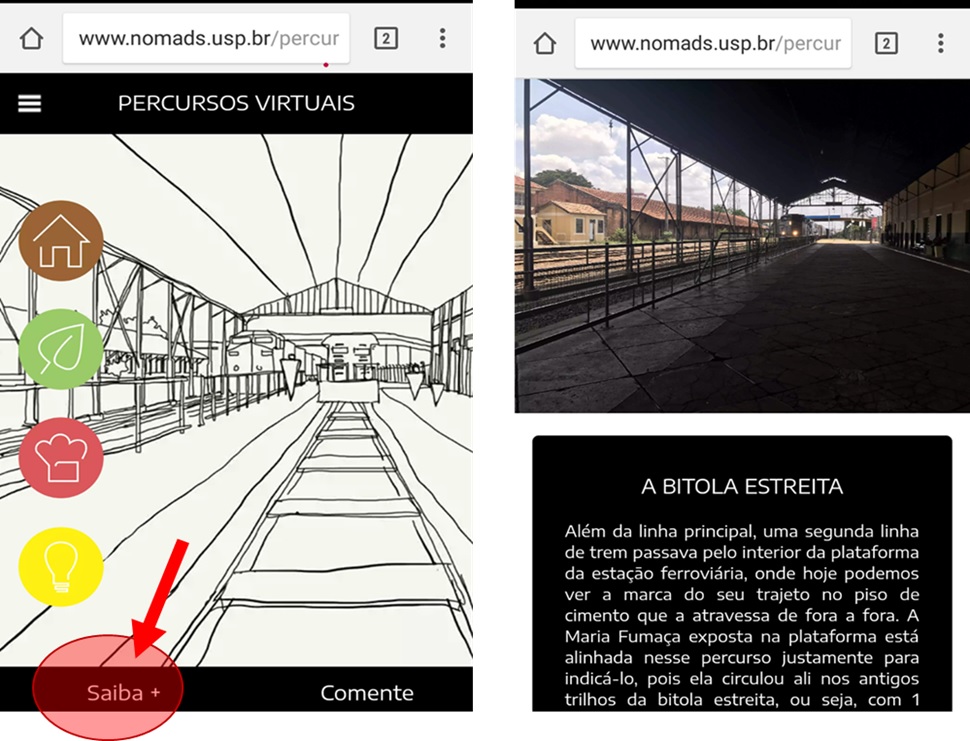

A interface ainda disponibiliza o ícone “Saiba +”, que leva o usuário a uma página na qual está inserida a história detalhada do lugar ou objeto observado, acrescida de uma imagem atualizada, conforme exposto pela Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Interface do projeto Percursos Virtuais. Desenho da Interface: Sandra Schmitt Soster; Sketches: Maria Clara Cardoso; Foto: Jessica Aline Tardivo; Desenvolvimento de Web: Maria Vitória do Nascimento Inocêncio. Fonte: Arquivo do Projeto, 2017.

O próximo avanço prevê a criação de um repositório aberto, onde a comunidade poderá adicionar novas informações sobre os lugares e objetos expostos na interface e inserir no sistema outros bens culturais que considerarem importantes para a memória da cidade, formando assim um mapeamento coletivo do patrimônio cultural. A finalização e implementação da estrutura piloto do projeto está prevista para o mês de agosto do ano de 2018.

O projeto (2) Educação Patrimonial: Desafios e Estratégias na Cultura Digital, faz parte da tese de doutorado, em desenvolvimento, da autora13 desse artigo. O trabalho, motivado pelo anseio de propiciar atividades educativas que possam contribuir para valorização e reconhecimento do patrimônio cultural de uma cidade, emprega como aporte metodológico as etapas de observação, registro, exploração e apropriação, propostas pela metodologia de Educação Patrimonial (HORTA, 1999). De tal modo, propõe mapeamentos cognitivos compostos pela leitura visual dos diversos aspectos que compõem a arquitetura do lugar, registrados por meio da Fotocolagem Digital.

Optou-se como suporte de intervenção o registro, manipulação e edição fotográfica, seguindo as observações do fotógrafo e historiador brasileiro Boris Kossoy, que compreende o autor da imagem como um “filtro cultural” cuja seleção do que se registra, resulta de sua sensibilidade e bagagem cultural (KOSSOY, 2012, p. 44). Nessa perspectiva, ao escolher o que registrar, o indivíduo aponta os objetos e espaços que considera importantes para memória e identidade do lugar.

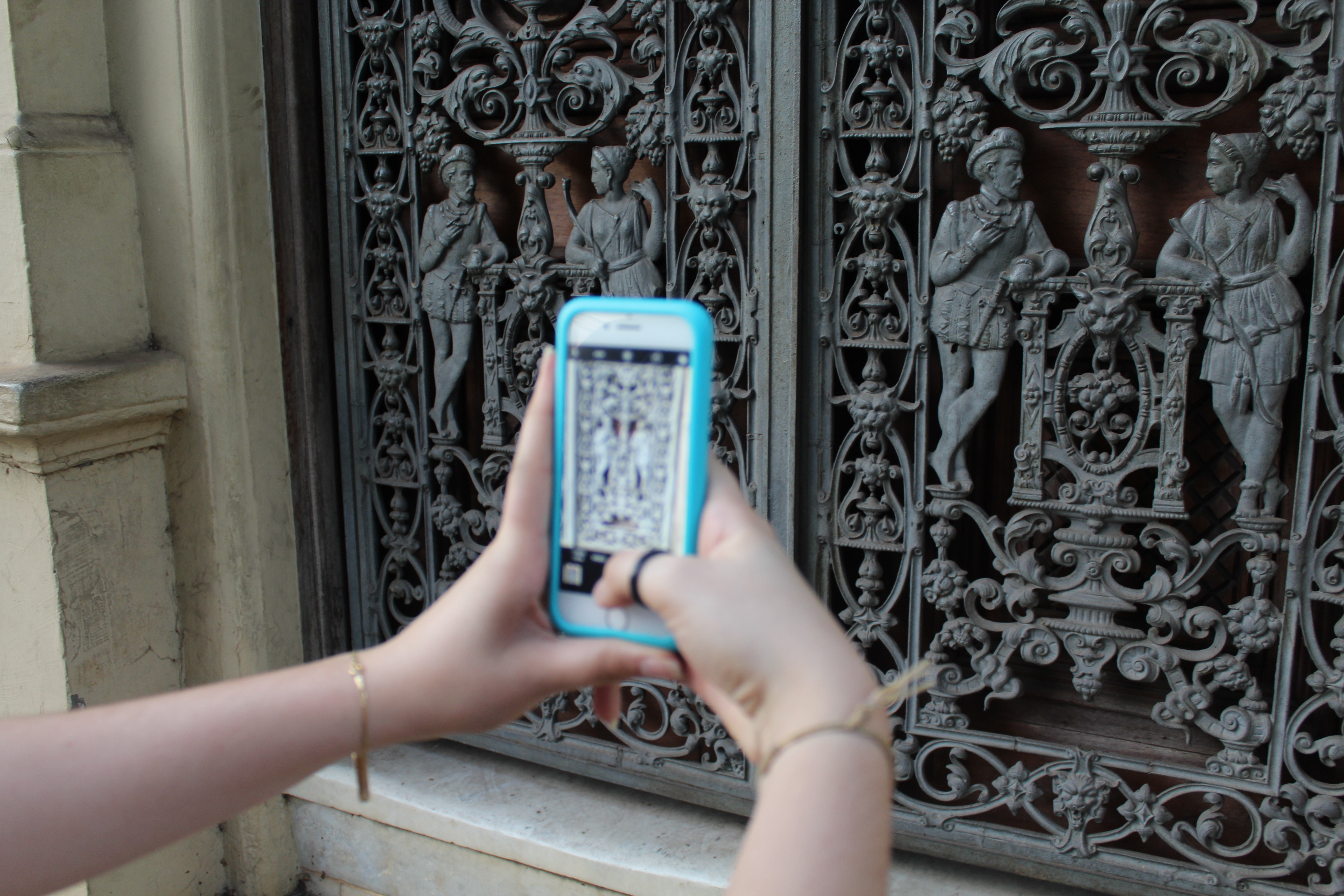

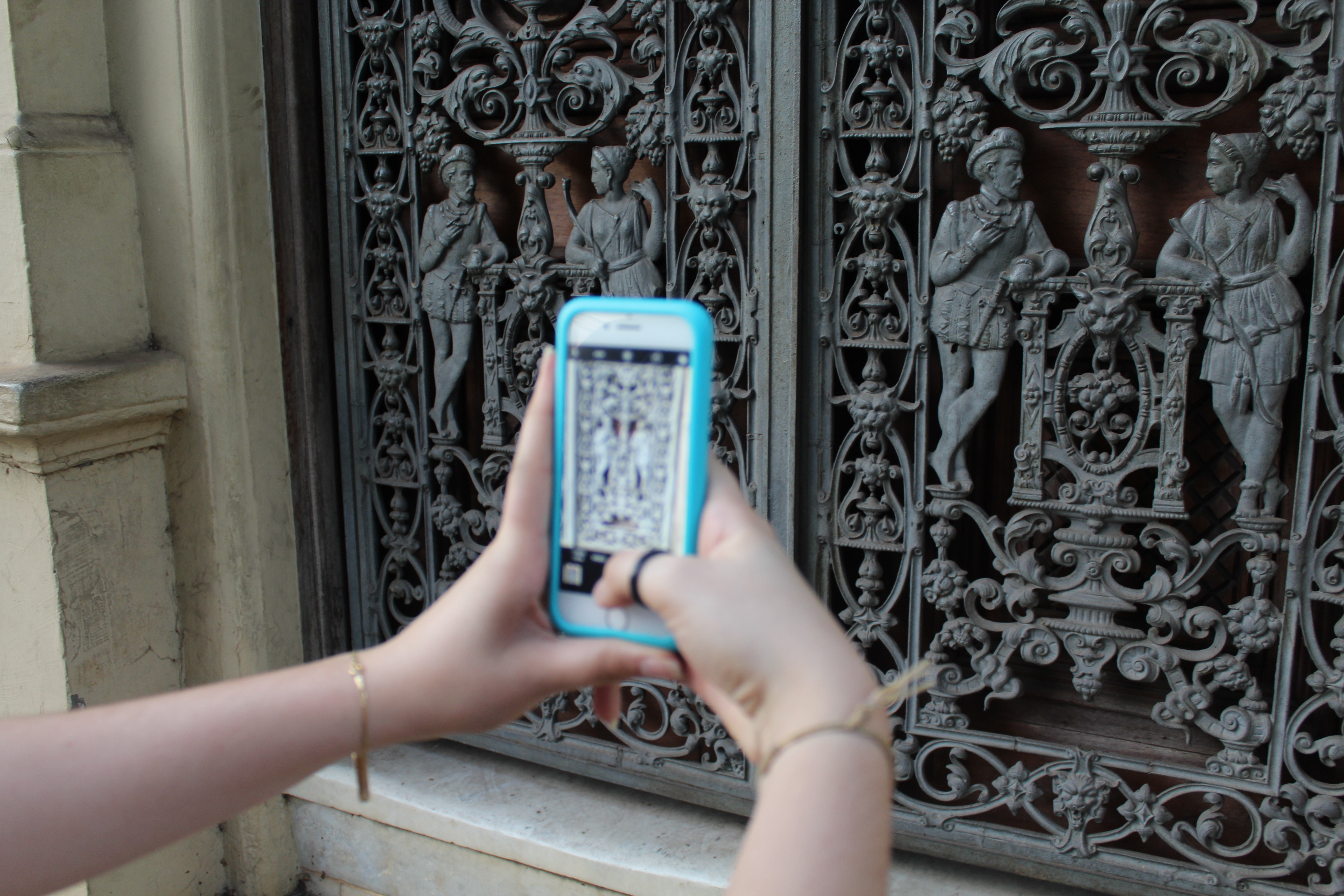

Assim, em um primeiro momento, seguindo as etapas de observação e registro, propõe-se a vivência de um grupo de pessoas por um eixo central da cidade a fim de que cada indivíduo observe e registre, através de dispositivos móveis, especificidades do local previamente escolhidas, como apresentado pela Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Experimento teste para ação Educativa. Foto: Jessica Aline Tardivo. Fonte: Arquivo da Pesquisa, 2017.

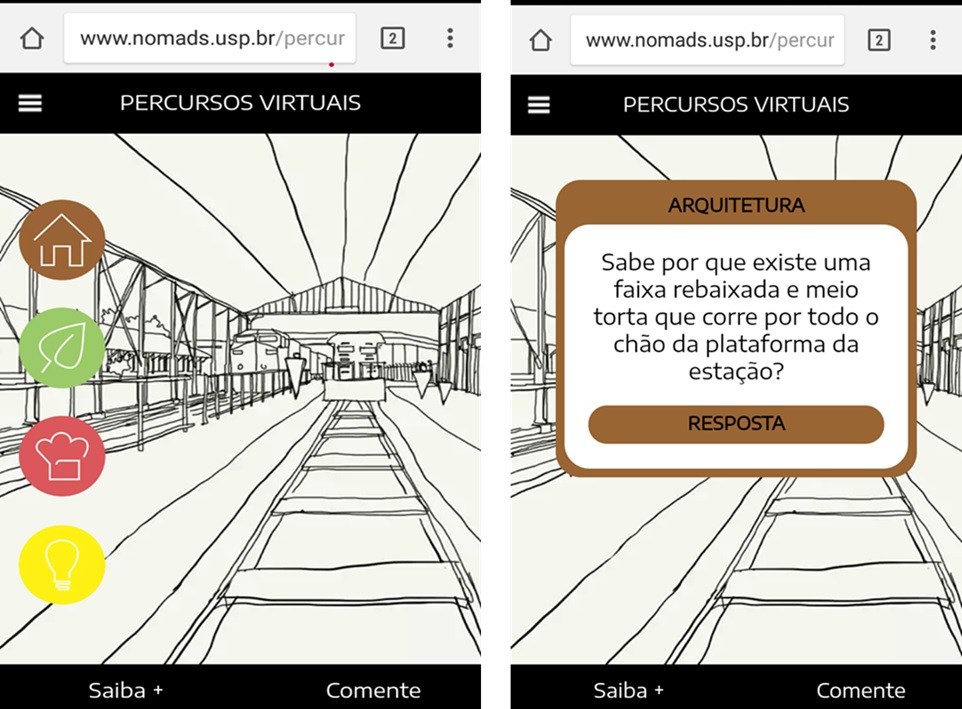

Para abranger as etapas de exploração e apropriação, escolheu-se trabalhar com a sobreposição de imagens em um processo de Fotocolagem Digital. Retomando a reflexão de Hatuka (2017, p.51) entende-se que analisar a cidade contemporânea é gerar “uma sobreposição de mapas de memórias”, e nesse sentido cada pessoa construirá um mapa visual dos objetos e bens que identificou e registrou. A manipulação das imagens será realizada com o uso de softwares, como Gimp e Power Point, conforme ilustra a Fig. 5, sobrepondo além das fotos, recortes de jornais, desenhos e textos, que serão pesquisados por cada pessoa e disponibilizados em um repositório digital aberto, a fim de que qualquer usuário possa usufruir dos dados do acervo.

Acredita-se que o trabalho de colagem, além de impulsionar a criatividade, permite que o indivíduo se aproprie do objeto registrado e construa interpretações e leituras subjetivas do lugar. Tal pensamento advém das obras da artista norte americana Hilary Williams14, que utiliza como recurso em seu trabalho a colagem e a gravura, a fim de configurar novas paisagens urbanas imaginárias. Aqui optou-se pela fotografia do real, misturada as memórias construídas em cada indivíduo a partir da vivência no espaço urbano, para composição dessa outra paisagem visual, como ilustra a Fig. 6.

O projeto será implementado nos meses de março e abril do ano de 2018 visando atingir o ensino formal e a comunidade local de uma cidade, tendo como campo de experimentação a cidade de Brotas, no interior do estado de São Paulo.

Ambos os trabalhos em andamentos permitem, a partir de ações educativas, a difusão do conhecimento sobre a história do lugar e a aproximação de grupos e comunidades com o patrimônio, oferecendo abertura para a participação dos indivíduos na construção de narrativas sobre a cidade, utilizando dispositivos móveis, softwares de acessíveis e repositórios abertos com a finalidade de que essas ações possam se perpetuar. Com a implantação do projeto (1) espera-se dar voz a população, a fim de que possam apontar novos espaços que considerem importantes para a memória da cidade e a contar suas histórias pessoais sobre os bens já expostos na interface, enquanto com o projeto (2) busca-se a construção de novas leituras e interpretações visuais sobre o patrimônio cultural existente na cidade.

4 Considerações finais

A partir do exposto depreende-se que a memória na cidade contemporânea é composta por diversas referências culturais, de tal modo o registro e a preservação da memória hoje não cabem apenas em suportes do passado, como livros, monumentos, entre outros. Nas reflexões apresentadas, abordou-se as ações educativas como facilitadoras da leitura e interpretação da cidade de hoje, resgatando os bens culturais do passado ainda preservados e tramados às dinâmicas e relações culturais, políticas e arquitetônicas do presente.

Acredita-se ainda que a facilidade do uso de recursos e meios tecnológicos, sobretudo o acesso a rede de internet através de dispositivos móveis, tem contribuído para que grupos de pessoas e comunidades possam se aproximar do patrimônio cultural e construir novas reflexões sobre a cidade. Nessa ótica, os projetos em andamento do grupo de pesquisa Nomads.ups, procuram contribuir com ações inspiradoras para construção colaborativa de narrativas mnemônicas da cidade.

Agradecimentos

Agradecemos à Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), agência de fomento financiadora desta investigação.

Equipe do Projeto Percursos Virtuais: Coordenadora Profa. Dra. Anja Pratschke. Doutorandas: Jessica Aline Tardivo ; Sandra Schmitt Soster. Alunos de Iniciação Científica: Maria Clara Cardoso; Maurício José da Silva Filho. Desenvolvedora Web: Maria Vitoria do Nascimento Inocencio. Fundação Pró-Memória de São Carlos: Cláudia Regina Danella, Débora de Almeida Nogueira, Fábio Fontana de Souza, Mariana Lucchino.

Referências Bibliográficas

ALENCAR, Vera Maria Abreu de. Museus-educação: se faz caminho ao andar. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Rio de Janeiro: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, 1987.

CANDAU, Joel. Memória e Identidad. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Del Sol, 2008, 208 p. (Título Original “Mémoire e Identité”, Traducción Eduardo Rinesi) Wilton C. L. Silva.

FLUSSER, Vilem. Arte viva. In: Ficções filosóficas. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1983.

GIMENO, Jesús; OLANDA, Ricardo; MARTINEZ, Bibiana; SANCHES, Fernando M. Observar, sistema de realidad aumentada multiusuario para exposiciones in XII Congresso Internacional de Interacción Persona-Ordenador: Lisboa, 2011.

HATUKA, Tali. A obsessão com a memória: O que faz conosco e com as nossas cidades (Pág. 47-60). In: Patrimônio Cultural Memória e intervenções urbanas. Org(s). CYMBALISTA, Renato; FELDMAN, Sarah e KUHL, Beatriz. [1ºEd]. São Paulo: Núcleo de Apoio e pesquisa de São Paulo, 2017.

HOOPER-GREENHILL, Eilean – Museum and Gallery Education.Leicester: Leicester Museum Studies, 2001.

HORTA, Maria de Lourdes Parreira: GRUNBERG, Evelina: MONTEIRO, Adriane Queiroz. Guia básico de Educação Patrimonial. Brasília: IPHAN: Museu Imperial, 1999.

IPHAN. Educação Patrimonial: histórico, conceitos e processos. Brasília: Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional Superintendência em Brasília, 2014.

KOSSOY, Boris. Fotografia & História. Cotia, SP: Ateliê Editorial, 2012.

LÉVY, Pierre. As Tecnologias da Inteligência. O futuro do pensamento na era da informática. (Tradução Carlos Irineu da Costa). Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34, 1993

NUNES, João Fernando. OLIVEIRA, Priscila Chagas. Cultura Digital e as Interfaces da Memória Social: estudo sobre o compartilhamento de imagens digitais na Fanpage “Acervo Digital Bar Ocidente” no Facebook. (Pag. 93-107) In: Revista Comunitária Midiática (online) V.11, Bauru: Unesp, 2016.

SANTOS, Fábio Lopes de Souza. As Neo-Vanguardas e a Cidade. II Encontro de História da Arte UNICAMP: Campinas, 2006. Disponível em <http://www.unicamp.br/chaa/eha/atas/2006/SANTOS,%20Fabio%20Lopes%20de%20Souza%20-%20IIEHA.pdf>. Acesso em 20. nov. 2017.

VIDLER, Antony. The Architectural Uncanny: Essay in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, Mass: MIT PRESS, 1992.

WILLIAMS, Hilary. Disponível em :<http://www.hilaryatthecircus.com/urban-landscapes/Acesso>. Acesso em 28. nov. 2017.

YATES, Frances A. The Arte of Memory. Chicago.The Universit of Chicago. Press, 1976. Tradução BANCHER, Flávia. A arte da memória. Campinas: Unicamp, 2007.

Site da pesquisa: http://www.nomads.usp.br/pesquisas/preservacaocomosistema/

1 O grupo de pesquisa Nomads.usp (Núcleo de Estudos de Habitares Interativos da Universidade de São Paulo), é parte do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo no campus de São Carlos.

2 Do original: Mémoire et identité, são ideias centrais nas teorias clássicas das ciências humanas e sociais, presentes em reflexões de diferentes áreas e orientações teóricas como nas análises da memória e/ou da identidade por autores tão diferentes quanto Henri Bérgson, Pierre Nora, Michel Maffesoli, Jacques Le Goff, Maurice Halbwachs, Gerard Namer, e Philippe Áries, Norbert Elias, Paul Connerton, Erving Goffman, Stuart Hall, Paolo Montersperelli, Paul Ricoeur, entre outros (SILVA, 2010).

3 Do original: In the traditional city, antique, medieval, or Renaissance, urban memory was easy enough to define; it was that image of the city that enabled the citizen to identify with its past and present as a political, cultural, and social entity (neither the ‘reality’ of the city nor a purely imaginary ‘utopia’, but rather a complex mental map of significance; thence the privileged place of monuments as markers in the city fabric).

4 Do original: The Arte of Memory.

5 Antes da idade moderna, técnica era sinônimo de arte: “criação e aplicação de formas vivenciadas, conhecidas e valorizadas” (FLUSSER, 1983, p. 83).

6 Do original: In the 1960s, museums became places of active learning. It is no longer enough to collect, preserve, and investigate, but such operations have become means for achieving another end that are people and their relation to objects. In other words, the centre of attention ceases to be the collection to be communication, In which learning and leisure are integrated.

7 Ver em: SANTOS. Fabio Lopes de Souza As Neo-Vanguardas e a Cidade. II Encontro de História da Arte UNICAMP: Campinas, 2006.

8 Ver em: Guia básico de Educação Patrimonial. Brasília: IPHAN: Museu Imperial, p.11,1999.

9 Artec Group é uma equipe da Universidade IRTIC, de Valência, fundada em 1992, que se dedica a gráficos interativos 3D, Realidade Virtual, Realidade Aumentada e Simulação Civil.

10 Do original em español: “Con este sistema se ha mejorado la asimilación de conocimientos de los visitantes de una manera amena y divertida, incentivando la práctica de exploración de puntos interés y la colaboración y discusión entre los participantes. En definitiva, se ha creado una herramienta de comunicación y aprendizaje con un alto grado de inmersión”.

11 O Prédio é sede da Fundação Pró-Memória.

12 A interface foi desenvolvida pelo grupo de pesquisa Nomads.usp, o acesso se dá preferencialmente por meio de celulares e tablets, e está disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/percursos/index.html> Acesso em 28.nov 2017.

13 A tese de doutorado da educadora e arquiteta Jessica Aline Tardivo está em andamento no Núcleo de Estudos de Habitares Interativos – Nomads.usp do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo, no campus de São Carlos, sob a orientação da Profª Dr.ª Anja Pratschke. Ambas autoras desse artigo.

14 Trabalho disponível em: <http://www.hilaryatthecircus.com/urban-landscapes/Acesso>15.out.2017.

Education and memory: digital methods and experiences

Jessica Aline Tardivo is an art teacher, pedagogue and architect, Master of Education and researcher at Nomads.usp. It studies the application of the methodology of Heritage Education, associated to the new technologies, with the purpose of facilitating the identification of the cultural inheritance of a city.

Anja Pratschke is architect and Doctor in Computer Science. Professor and researcher at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo, Brazil, and a co-coordinator of Nomads.usp. She develops and guides research in the areas of design and communication processes in architecture.

How to quote this text: TARDIVO, J; PRATSCHKE, A.. Education and memory: digital methods and experiences.V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 15, 2017. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus15/?sec=6&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 03 July 2025].

Resumo

This article presents educational possibilities mediated by digital means that facilitate the approximation between individuals and cultural assets, bringing to the fore the rescue of memory and new interpretations about the city. With this aim, the memory location in the present city is initially introduced. Then Heritage Education actions associated to the new communication technologies as a resource in the construction of memory will be presented. Finally, we evaluate the use of interactive interfaces, accessed by the reading of QR Codes, and the production of photo collagens that have been used in research on cultural heritage by the research group Nomads.usp.1

Keywords: City, Heritage education, Memory, Digital media

1 Memory in the current city

Before conjecturating the place of memory in the present city, it is necessary to reflect on the reason for memory and its social role. It is possible to verify in several writings the memory of the city taking the role of the identity of the place, so it is important to clarify that in the study of this article, adopting as a reference the research of the French sociologist Joel Candau, published in the work "Memory and Identity"2 in the year of 1998, memory is understood as a set of narratives that report the affective and historical remembrances. By connecting the past to the present and making possible future projections of a society or place, the identity is composed by the choices that are made from the acquired knowledge.

Cultural identity of a place and the way of life of a society, is constituted by cultural goods, histories and manifestations that a group chooses to preserve and is changing according to the habits of different generations, while the memory is a contribution so that everything that was constructed, produced and learned can be rescued over time.

Turning specifically to memory in Antiquity, for example, the real together with the mnemonic image of the city helped the individual to locate between the past and the present. According to the American historian Antony Vidler (1992: 177):

In the traditional city, antique, medieval, or Renaissance, urban memory was easy enough to define; it was that image of the city that enabled the citizen to identify with its past and present as a political, cultural, and social entity (neither the ‘reality’ of the city nor a purely imaginary ‘utopia’, but rather a complex mental map of significance; thence the privileged place of monuments as markers in the city fabric).

The English historian Frances Yates described in her work the "Art of Memory" (1976), different and elaborate techniques of memorization used throughout the middle ages and rebirth, which helped the individual to remember historical and literary contexts, to be located in space time. Many of these techniques were given by the memorization of physical and imaginary places, whose parts of each space should be composed or filled mentally by the information that each person wanted to remember. Memory was given not only as a reminder of tradition, but as techné3 or mnemotechnics, processes that are now recognized as the Art of Memory (FLUSSER 1983: 83).

In today's city, reading places, constructing mnemonic maps, or recognizing a local identity becomes much more complex as individuals have access to communication and information networks and are able to quickly search historical contexts, maps of location, among others, which decreases the need to memorize. These networks also enable contact with diverse cultural, religious and political manifestations, so that each person can choose between habits and customs those that best meet their expectations and goals. This is one of the factors that makes the mnemonic map of the present city an overlap of cultural identities.

Israeli architect and an expert on contemporary city history Tali Hatuka presents an even more complex view, reflecting that

Multiple synchronous maps superimposed over one another are being created in today's city in an endless process. In fact, some of these memory maps will not last for long. There are not many active agents to keep them or keep them in the minds of the people nor significant capital to maintain their existence in physical space (HATUKA, 2017, 51).

Hatuka (2017: 51) asks what will be forgotten and what will be preserved in relation to the culture of today's city? One possible answer would be to think that when approaching a time when people experience multiple histories and different social consciences, one must realize that memory is not static, it transforms with time, as well as identity.

She (2017, p. 51) notes a critical view of cultural goods and manifestations as market product, when the architect reinforces the lack of "capital" for the preservation of memory. On this view, it is concluded that if in theory the structures recognized as cultural goods are preserved only from records and registers, administered by preservation policies, and these assets become local tourist attraction, yes, it can be agreed that there are no viable resources for the preservation of different manifestations in physical space.

However, it is understood here that the different manifestos change and form part of the cultural complex of a city in such a way that it is believed that formal and informal actions, educational activities and differentiated readings of the city, registered by the arts disposed in literary works, photographs, films and documentaries, allow the recording, reading and interpretation of memory in the city today.

In fact, the first initiatives to bring people and cultural objects together took place in formal spaces, especially in Europe, when museum and galleries exhibition spaces were seen as places of learning and adopted teaching methods to present the content to visitors, as quoted by the English educator Eilean Greenhill Hooper (2001: 52):

In the 1960s, museums became places of active learning. It is no longer enough to collect, preserve, and investigate, but such operations have become means for achieving another end that are people and their relation to objects. In other words, the centre of attention ceases to be the collection to be communication, In which learning and leisure are integrated.

In order to facilitate the educational and reflective process, a category of professionals was created, initially in England, the museum educators, who will act as interlocutors between the visiting public and the exhibited goods (HOOPER, 2001, pp. 40-54).

It is also during this period that a historiographical approach known as New History or New Cultural History arises in France. Part of the formal education of the whole of Europe, as Heritage Education, the objective was to provide a learning 'centered on the cultural object, on the material evidence of the culture [...]', and was based in "[...] an educational process that considers the object as a primary source of education" (ALENCAR, 1987, p.26).

This teaching practice allowed the students to have an initial contact with the cultural assets so that later they could gauge the historical data with greater autonomy and criticality. However, the experiences throughout the 1990s are not only restricted to the exhibition spaces, but begin to permeate the monuments and places of the city. Concomitantly, artistic manifestations, such as the Neo-vanguards4, began to interpret and experiment in a different way the spaces of the city.

2 Heritage education: memory resources and technologies

In Brazil, Heritage Education was inserted in the educational practices of the Imperial museum of Rio de Janeiro by the museologist Maria de Lourdes Horta in 1985 and then systematized in four stages of application: (1) observation, (2) registration, (3) exploration and (4) appropriation5, which were set out in a guide published by IPHAN in the year 1999.

The goal of IPHAN was to use the methodology as an instrument of cultural training, aiming to bring society closer to material heritage, especially in formal teaching practices. At the present time, the method has become the basis for IPHAN's educational, formal and informal actions, which involve cultural heritage as a whole. (IPHAN, 2014 page 13).

At the end of the 1990s, the process of popularization of the use of communication and information networks was made possible by access to the internet network. This advance facilitated the projection and insertion of activities in interactive platforms, such as virtual museums, games and collective collections, creating other spaces of cultural memory registration, inserted in cyberspace.

According to the philosopher Pierre Levy (1993, p. 28), the configuration of "educational and socio-cultural knowledge and practices comes from the structure of language and intelligence technologies" that stand out in a feedback process, and change as they are used. On this point of view, the Brazilian researchers, specialists in communication and social memory, João Nunes and Paola Oliveira report (2016: 96):

At the same time that the computer age ushered in an even greater potential for our intelligence, it also caused a revolution in the processes of selection, storage, and availability of memory supports, which, acting as artificial extensions of cognition. The dynamics of memory and forgetting are increasingly evident in the virtual universe, since the management of memory and knowledge is shared on the web and its access depends almost exclusively on the updating of hardware and software.

From this observation it is understood that the digital media harbor different possibilities of dissemination of knowledge, memory and history, and cyberspace promotes the breaking of barriers and limits imposed by space/time. However, their support depends on the constant sharing of information. Still for Nunes and Oliveira (2016: 99):

If in the past the places of the parietal paintings, in the Cave of Chauve, the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, the Renaissance sculptures and paintings in the museums and galleries, and the texts of the archives and libraries were designated to the storage, circulation and enjoyment of our visual references, symbolic supports of memory. Today this place, in cyberspace, is "the whole place".

The first experiences around the use of cyberspace and technological resources as a medium and support of cultural memory, advanced in mid-2010 due to the refinement of computer programming, which made possible 360º access to cultural objects and objects (Nunes, Oliveira , 2016). Nowadays, the ease of use of mobile devices, such as mobile phones and tablets, which allow connection to the internet network, installation of applications, among others, has made room for the use of Virtual and Augmented Reality (a real-time simulation of modification of the space) and the QR Codes (codes that allow the connection of mobile devices with different interfaces).

Some institutions, museum spaces and private organizations have been using these resources successfully in their educational actions, such as the project Videoguía: Virtual and Augmented Reality, accessible since 2012 at Casa Batló in Barcelona, Spain, by the research group Artec6 , of the Institute of Robotics and Technologies of Information and Communication of Valencia.

The project Videoguía: Virtual and Augmented Reality was developed with the objective of providing interactivity between the visitor and the physical environment. The system consists of a mobile device in which an application is installed that displays the objects and the original spatial configurations of the exhibition rooms, including audiovisual elements and 3D virtual objects with which the public can interact. The rooms of the building are identified in the application by numbers, and upon accessing the corresponding number, the user positions the device towards the actual room to visualize the place and objects in different times and situations, as shown by Fig.1.

This system enabled the museum to build a new educational process, since the video guide has information about heritage, history, geography and culture. For Gimeno et al. (2012, page 8)

This system has improved the assimilation of visitors' knowledge in a fun way, encouraging the practice of exploring points of interest and collaboration and discussion among participants. In short, we have created a communication and learning tool with a high degree of immersion (our translation)7.

For this example, the use of technology has facilitated the educational dynamics and practices around memory, but costs such as internet network, maintenance and purchase of equipment, production of applications, among others, make it difficult to access these different dynamics. In this way, interactivity has generally been used in private institutions such as museums and in large events and exhibitions.

3 Interactive actions for reading and interpreting the memory of the city

Trying to make educational actions feasible, the research themes of the Nomads.usp research group have included different studies with a transdisciplinary character that seek an openness so that groups and communities can know, reflect and develop critical discussions about the city. Regarding memory, we investigate the possibilities of using digital media and audiovisual resources for the observation, dissemination, preservation and management of cultural heritage in contemporary times. To illustrate this process, I will refer to two projects in the implementation phase: (1) Virtual Paths: Collaborations in Narratives of the Cultural Heritage of São Carlos, supported by interactive interfaces accessed through QR Codes, and (2) Heritage Education: Challenges and Strategies in Digital Culture, which experiences the use of digital photo collagens in the construction of new urban landscapes.

The (1) Virtual Tours project: Collaborations in Narratives of the Cultural Heritage of São Carlos, emerged from a partnership in 2017 between the Pró-Memória Foundation of the city of São Carlos and the research group aiming to develop educational and interactive activities, proposing as a resource the use of mobile devices (cell phones and tablets), directed to the knowledge and dissemination of the history of the city's architectural heritage.

Analyzing the two available technological resources, the project was committed to creating a mediated learning routine using QR Codes, that will be fixed in buildings of historical relevance of the city. Initially, it is located as pilot in the spaces of the Sao Carlos' Railway Station8 The system targets interactivity between the building and the user, which when positioning the mobile device over the QR Code will be directed to an interactive interface.9 that will make available information and curiosities about the place through questions and answers, as shown by Fig.2.

Fig. 2. Interface of the Virtual Paths project. Interface Design: Sandra Schmitt Soster; Sketches: Maria Clara Cardoso, Web Development: Maria Vitória do Nascimento Inocencio. Source: Project Archive, 2017.

The interface also provides the icon "Learn +", which takes the user to a page in which is inserted the detailed history of the place or object observed, plus an updated image, as shown by Fig.3.

Fig. 3. Interface of the Virtual Paths project. Interface Design: Sandra Schmitt Soster; Sketches: Maria Clara Cardoso; Photo: Jessica Aline Tardivo; Web Development: Maria Vitória do Nascimento Inocencio. Source: Project Archive, 2017

The next breakthrough in the system provides the creation of an open repository where the community can add other information about the places and objects exposed in the interface and insert into the system other cultural assets that they consider important for the memory of the city, thus forming a collective mapping of the cultural heritage. The completion and implementation of the pilot project structure is scheduled for August 2018.

The project (2) Heritage Education: Challenges and Strategies in Digital Culture, is part of the doctoral thesis in development, of one of the authors10 of this article. The work, motivated by the desire to provide educational activities that can contribute to the valorization and recognition of the cultural heritage of a city, employs as a methodological contribution the stages of observation, registration, exploration and appropriation, proposed by the methodology of Heritage Education (HORTA, 1999). In this way, it proposes cognitive mappings composed by the visual reading of the several aspects that compose the architecture of the place, registered through Digital Photo Collages.

Recording, manipulation and photographic editing were used as intervention support, following the observations of the Brazilian photographer and historian Boris Kossoy, who understands the author of the image as a "cultural filter" whose selection of what is recorded results from his sensitivity and cultural luggage (KOSSOY, 2012, page 44). In this perspective, in choosing what to record, the individual points out the objects and spaces, he considers important for memory and identity of the place.

Thus, at first, following the observation and recording stages, it is proposed to get together a group of people along a central axis of the city in order to allow through mobile devices, individual observation and register specificities of the place previously chosen, as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Experiment Test for Educational action. Photo: Jessica Aline Tardivo. Source: Research Archive, 2017.

To cover the exploration and appropriation steps, it was chosen to work with the overlapping of images in a Digital Photo-Collage process. Returning to Hatuka's reflection (2017, p. 51), it is understood that analysing the contemporary city is to generate "overlapping memory maps," and in this sense each person will construct a visual map of the objects and goods that he has identified and recorded. The manipulation of the images will be carried out with the use of software, such as Image Editing software and presentation software, as shown in Fig. 5, overlapping photos, newspaper clippings, drawings and texts that will be searched by each person and be available in an open access digital repository, so that any user can take advantage of the collection data.

We believe that collage work, in addition to boosting creativity, allows the individual to appropriate the registered object and construct interpretations and subjective readings of the place. Such thinking comes from the works of the North American artist Hilary Williams11, who uses collage and engraving as a resource in her work to configure new imaginary urban landscapes. Here we chose the photograph of the real, mixed with the memories constructed individually based at the experience in the urban space, for the composition of this other visual landscape, as shown in Fig.6.

The project will be implemented in the months of March and April of the year 2018 to reach the formal education and the local community of a city, having as field of experimentation the city of Brotas, in the interior of the state of São Paulo.

Both works in progress allow for the dissemination of knowledge about the history of the place and the approximation of groups and communities with heritage, offering openness for the participation of individuals in the construction of narratives about their city, using mobile devices, accessible software and open repositories in order that these actions can be perpetuated. With the implementation of the project (1), it is expected that the population will be given a voice so that they can identify new spaces that they consider important for the memory of the city and tell their personal stories about the heritage already exposed in the interface, while the project (2) we seek the construction of new readings and visual interpretations of the cultural heritage in the city.

4 Final considerations

The memory in the contemporary city is composed of several cultural references, such that the recording and preservation of memory today cannot be accommodated only in the past, such as books, monuments, among others. In the reflections presented, the educational actions were used as facilitators of the reading and interpretation of the city of today, rescuing the cultural assets of the past still preserved and plotted to the dynamics and cultural, political and architectural relations of the present. We also believe that the ease of use of resources and technological means, especially access to internet network through mobile devices, has contributed for groups of people and communities can approach cultural heritage and build new reflections on the city. From this point of view, the ongoing projects of the Nomads.ups research group seek to contribute with inspiring actions for collaborative construction of mnemonic narratives of the city.

Aknowledgement

We thank the Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for funding this research work.

Project Tours Virtual Paths: Coordinator Profa. Dr. Anja Pratschke. Doctoral Students: Jessica Aline Tardivo; Sandra Schmitt Soster. Students of Scientific Initiation: Maria Clara Cardoso; Maurício José da Silva Filho. Web Developer: Maria Vitoria do Nascimento Inocêncio. Pro-Memory Foundation of São Carlos: Cláudia Regina Danella, Débora de Almeida Nogueira, Fábio Fontana de Souza, Mariana Lucchino.

References

ALENCAR, V. M. A. 1987. Museus-educação: se faz caminho ao andar. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Rio de Janeiro: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro.

CANDAU, J. 2008. Memória e Identidad. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Del Sol, 208 p. (Original title: “Mémoire et Identité”. Translated to Spanish by Eduardo Rinesi and Wilton C. L. Silva.

FLUSSER, V.1983. Arte viva. In: Ficções filosóficas. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo.

GIMENO, J.; OLANDA, R.; MARTINEZ, B.; SANCHES, F. M. 2011. Observar: sistema de realidad aumentada multiusuario para exposiciones. In: Lisboa: XII Congresso Internacional de Interacción Persona-Ordenador.

HATUKA, T. 2017. A obsessão com a memória: O que faz conosco e com as nossas cidades (Pág. 47-60). In: Patrimônio Cultural Memória e intervenções urbanas. CYMBALISTA, Renato; FELDMAN, Sarah e KUHL, Beatriz. (Orgs.)[1ºEd]. São Paulo: Núcleo de Apoio e Pesquisa de São Paulo.

HOOPER-GREENHILL, E. 2001. Museum and Gallery Education. Leicester: Leicester Museum Studies.

HORTA, M. L. P.: GRUNBERG, E.: MONTEIRO, A. Q. 1999. Guia básico de Educação Patrimonial. Brasília: IPHAN: Museu Imperial.

IPHAN. 2014. Educação Patrimonial: histórico, conceitos e processos. Brasília: Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional Superintendência em Brasília.

KOSSOY, B. 2012. Fotografia & História. Cotia, SP: Ateliê Editorial.

LÉVY, P. 1993. As Tecnologias da Inteligência: o futuro do pensamento na era da informática. (Tradução Carlos Irineu da Costa). Rio de Janeiro: Editora 34.

NUNES, J. F.. OLIVEIRA, P. C. 2016. Cultura Digital e as Interfaces da Memória Social: estudo sobre o compartilhamento de imagens digitais na Fanpage “Acervo Digital Bar Ocidente” no Facebook. (Pag. 93-107) In: Revista Comunitária Midiática (online) V.11, Bauru: Unesp.

SANTOS. F. L.S. 2006. As Neo-Vanguardas e a Cidade. II Encontro de História da Artes. Campinas: UNICAMP. Disponível em <http://www.unicamp.br/chaa/eha/atas/2006/SANTOS,%20Fabio%20Lopes%20de%20Souza%20-%20IIEHA.pdf>. Acesso em 20. nov. 2017.

VIDLER, A. 1992. The Architectural Uncanny: Essay in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, Mass: MIT PRESS.

WILLIAMS, Hilary. Disponível em : <http://www.hilaryatthecircus.com/urban-landscapes/Acesso>. Acesso em 28. nov. 2017.

YATES, Frances A. 1976. The Art of Memory. Chicago.The Universit of Chicago. Press, 1976. Translation to Portuguese by BANCHER, F. 2007. A arte da memória. Campinas: Unicamp.

Research website: http://www.nomads.usp.br/pesquisas/preservacaocomosistema/

1 The research group Nomads.usp (Center for Interactive Living Research, University of São Paulo) is part of the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, at the São Carlos campus.

2 From the original: Mémoire et identité are central ideas in the classical theories of human and social sciences, present in reflections of different areas and theoretical orientations as in the analyzes of memory and/or identity by authors as different as Henri Bérgson, Pierre Nora, Michel Maffesoli, Jacques Le Goff, Maurice Halbwachs, Gerard Namer, and Phillippe Aries, Norbert Elias, Paul Connerton, Erving Goffman, Stuart Hall, Paolo Montersperelli, Paul Ricoeur, among others.

3 Before the Modern Age, technique was synonymous with art: "creation and application of lived, known and valued forms" (FLUSSER, 1983, p. 83).

4 See: SANTOS. Fabio Lopes de Souza As Neo-Vanguardas e a Cidade. II Encontro de História da Arte UNICAMP: Campinas, 2006.

5 See: Guia básico de Educação Patrimonial. Brasília: IPHAN: Museu Imperial, p.11, 1999.

6 The Artec Group is a team from the IRTIC University of Valencia, founded in 1992,working on Interactive 3D graphics, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Civil Simulation.

7 From the Spanish: “Con este sistema se ha mejorado la asimilación de conocimientos de los visitantes de una manera amena y divertida, incentivando la práctica de exploración de puntos interés y la colaboración y discusión entre los participantes. En definitiva, se ha creado una herramienta de comunicación y aprendizaje con un alto grado de inmersión”.

8 The building hosts the Pró-Memoria Foundation.

9 The interface was developed by Nomads.usp. Access is preferably given through cell phones and tablets. Available at: http://www.nomads.usp.br/percursos/index.html. 28.nov 2017.

10 The doctoral thesis of educator and architect Jessica Aline Tardivo is underway at Nomads.usp, at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo, on the São Carlos campus, under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Anja Pratschke. They are both authors of this article.

11 The work is available at: <http://www.hilaryatthecircus.com/urban-landscapes/Acesso>15.out.2017.