Memórias do Terreiro da Gomeia: entre a sacralidade e a dessacralização

Rodrigo Pereira é graduado em Ciências Sociais, Mestre em Ciências Sociais e Mestre em Arqueologia. Membro do Laboratório de História das Experiências Religiosas e professor colaborador na Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, estuda e orienta pesquisas sobre religiões e religiosidades, em especial as afro-brasileiras. Em Antropologia pesquisa o Candomblé, debatendo micro política em terreiros, eventos de sucessão e temas relacionados à liminaridade.

Como citar esse texto: PEREIRA, R. Memórias do Terreiro da Goméia: entre a sacralidade e a dessacralização. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 16, 2018. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus16/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 05 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

A memória pode ser conceituada como sendo aquela capacidade humana de conservar certas informações, sentimentos e vivência que permitem ao indivíduo atualizar impressões ou informações passadas ou ainda as reinterpretar como passadas. Contudo, esta ação dá-se sempre no presente e não é eivada de posições sobre os fatos rememorados. A partir das escavações arqueológicas empreendidas nos remanescentes do Terreiro da Gomeia (Duque de Caxias/RJ) e das memórias recolhidas acerca de seu funcionamento e crise sucessória, o presente artigo visa debater a função da memória na construção de narrativas sobre o local, seu funcionamento, crise sucessória e destruição. A Gomeia foi um dos grandes candomblés fluminenses, tendo funcionado de 1951 até 1971, quando seu dirigente faleceu e iniciou-se uma crise sucessória. A formação de três vertentes sobre estes fatos demonstra como a memória é política e visa justificar determinados pontos de vista e posições. As memórias recolhidas em pesquisa serão utilizadas como um dos suportes para a construção da interpretação arqueológica sobre o término do terreiro de candomblé fluminense.

Palavras-Chave: Memória, Arqueologia, Candomblé, Terreiro da Gomeia

1 Introdução1

Na década de 1940, um babalorixá baiano migrou para o Rio de Janeiro. João Alves Torres Filho, com a alcunha de Joãozinho da Gomeia, saiu de Salvador e dirigiu-se para a então Capital Federal. Tata Londirá, seu nome religioso, é identificado como pertencente a tradição religiosa dos Candomblés Angola e de Caboclo soteropolitanos (CHEVITARESE; PEREIRA, 2016). Consideramos esta situação um dos motivos para a transferência do dirigente para o Rio de Janeiro. Como Capone (1996) defende, ele estava incluído em uma “marcha religiosa” de pais/mãe de santo que deixavam a Bahia e se instalavam em solo fluminense em busca de um mercado religioso não dominado pelas yalorixás de Salvador. Outro motivo para a marcha residia no preconceito que o babalorixá sofria por ser homossexual, dançarino e músico, o que pode ter sido decisivo para que o Rio de Janeiro fosse visto como um local que permitisse uma nova trajetória (CHEVITARESE; PEREIRA, 2016).

Em 1951, Joãozinho da Gomeia inaugurava seu terreiro em meio a uma ampla cobertura dos jornais, pois o dirigente não era apenas um pai de santo, mas já atuava no carnaval carioca (Jornal Correio da Manhã, 9 de dezembro de 1951). Nos carnavais da década de 1950 e 1970 apresentou-se em festas em clubes da Zona Sul, desfilou nas escolas de samba e atuou ainda como um dos coreógrafos do Cassino da Urca e Teatro João Caetano, todos na então capital do Brasil (CHEVITARESE; PEREIRA, 2016). O Manso Bantuqueno Ngomenssa Kat'espero Gomeia ou Terreiro da Gomeia iniciou suas atividades instalando-se na cidade de Duque de Caxias – região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. A casa tornou-se ponto referencial para artistas e políticos que buscavam mais que conselhos religiosos, a amizade com Joãozinho da Gomeia rendia recomendações a estes e trabalhos para facilitar situações políticas e econômicas (CHEVITARESE; PEREIRA, 2016).

Contudo, em 1971, a descoberta de um tumor cerebral, seguido de uma operação para sua extração, levou o dirigente a falecer. A sua morte colocou os seus filhos de santo frente às questões sucessórias do terreiro e, como consequência, não houve um consenso quanto a quem deveria ser o/a novo/a regente do local. Mesmo após a escolha, por meio de consulta ao jogo de búzios, de uma criança de 10 anos (Seci de Angorô)2, instalou-se um conflito sobre a legitimidade desta nova liderança, o que desembocou na formação de grupos que questionaram a escolha e desejavam que o local tivesse outras lideranças (PEREIRA, 2015). Uma das fontes orais apresenta da seguinte forma a nova liderança escolhida:

Seci era filha de Kitala, uma das filhas de santo que se mudou de Salvador para o Rio com Pai João. Kitala era a filha de santo mais velha dele e a gente a respeitava por isso. Ela tinha axé e força de comando.... Seci?? Seci não tinha isso, nunca teve. Ela [Kitala] era mãe de sangue de Seci, mas que fez a menina foi Joãozinho. Sabe, mãe carnal não pode iniciar a própria filha. A Seci nasceu dentro da Gomeia. Quem fez o parto não foi médico, mas sim o Caboclo de Pai João. Depois que ela nasceu Iansã desceu em Pai João e indicou que a menina seria a sucessora dele, mas nós nunca demos bola para isso, a gente não esperava que ele morresse como morreu. A Seci foi feita pro [sic] santo ainda bebê porque era uma criança muito doente, fraquinha... Seci foi criada fora do terreiro, lá em Copacabana. Ela foi criada por uma madrinha que deu estudo, botou ela no francês, na dança. Mas tudo era pago por Pai João. Ela [Seci] teve do bom e do melhor, mas não foi criada com a gente lá dentro da Gomeia. Ela aparecia lá só pra [sic] festas. Quando ela foi escolhida para a Gomeia a gente sabia que ela era fraca para a coisa, não teria pulso para comandar a Gomeia. Ela era uma criança. Como uma criança poderia ficar na frente das coisas? Não podia e a gente não podia deixar aquilo tudo morrer (ENTREVISTADO (A) E 12).

A sucessão foi acirrada quando a mãe biológica do dirigente falecido optou por vender o terreno onde situava-se a Gomeia e mudar-se para Salvador (BA). Como foi verificado entre as fontes orais, este ato levou a um determinado grupo de filhos de santo a conseguir a posse legal do terreiro, o que influenciou a continuidade do local. As querelas sucessórias foram exponenciada devido a uma acusação de “roubo” por parte de grupos de oposição ao que adquiriu o terreiro e suas dependências.

O Terreiro da Gomeia entrou em desuso ou abandono total apenas no final da década de 1980, a data aproximada para isso foi o período compreendido entre os anos de 1985 até 19883, pois as fontes orais não têm certeza e unanimidade quanto ao fato. Contudo, os dados orais indicam que o local continuou a iniciar filhos de santo por meio de Mametu Kitala e outros que permaneceram no local neste interim da década de 1980. Porém, a grave crise e o fechamento do local impediram esta continuidade.

Até a década de 2000 o terreno foi utilizado pela população do entorno como um espaço para que crianças brincassem e para a realização de festas juninas. Na década seguinte foi erguido uma pequena mureta para a acomodação do “Gomeia Sport Clube” – um time de futebol dos moradores da rua – o que não durou muito tempo, pois o local passou a ser usado como estacionamento de caminhões (PEREIRA et al, 2012). O destino da área da Gomeia foi definido em 2003, quando a Prefeitura de Duque de Caxias desapropriou o local para a construção de uma creche (GAMA, 2014). Contudo, o projeto não foi executado pela municipalidade, ficando o terreno sem uso até a atualidade.

Destaca-se que os eventos de sucessão foram decisivos para a instauração de um processo que levou a desagregação dos espaços erigidos do terreiro4. O conflito, ou mesmo o descaso, pode ter sido um dos fatores que desencadearam o processo de destruição do local, seja pela subtração de elementos ou mesmo pela inexistência de manutenção. Neste artigo averiguaremos neste como se procedeu no local uma série de ações que desembocaram na desagregação e/ou destruição dos espaços erguidos por Joãozinho da Gomeia.

Após o conflito instaurado, em tempo cronológico não consensual entre as fontes orais, já que a Justiça havia impedido que a criança escolhida pelos búzios assumisse o comando total do terreiro, um filho de santo da casa, por meio de consulta ao grupo, incumbiu-se da tarefa da compra do terreno onde situava-se a Gomeia, pois a mãe carnal de Joãozinho optara por retornar para a Bahia após a morte de seu filho. A oralidade é unânime em afirmar que os filhos de santo, cada um à sua maneira, contribuíram para a aquisição do local, sempre expressando a ideia de que ele permanecesse aberto. Ao que tudo indica, este fato ocorreu, mas neste ponto as consequências variam conforme o entrevistado/a. Formaram-se, assim, três memórias sobre a destruição e fechamento do local.

Para um grupo (entrevistados E2, E3, E5 e E11) a compra foi seguida de uma expulsão do grupo litigante que via em Sandra a sucessão. Esta ação teria se dado com o auxílio de forças policiais que fecharam o acesso à rua onde localiza-se a Gomeia para que os objetos pessoais e religiosos deste grupo fossem retirados do terreiro e colocados na rua. Quando os litigantes conseguiram chegar em frente a este, só puderam recolher seus assentamentos, roupas e demais objetos rituais e não foram mais permitidos de adentrar o espaço. Com o fechamento, parte da cultura material da Gomeia foi transferida para outro terreiro fora do Rio de Janeiro. Para lá teriam sido transferidos, conforme a oralidade, os assentamentos da casa5, o trono do dirigente6 e objeto pessoais deste7.

Para outro grupo (entrevistados E1, E4, E8 e E10), a instabilidade da sucessão foi a responsável pelo fato de que, após a compra, os filhos de santo não chegassem a um acordo quanto a quem deveria governar. Assim, o trio indicado pela justiça para tal fim – Ogã Valentim, Mametu Kitala e Mametu Ileci – não tiveram comando político e religioso para manter o terreiro aberto. Este funcionou por mais alguns anos, inclusive com iniciações posteriores a morte do dirigente, sendo fechado por falta de recursos e membros entre os anos de 1985 e 1988.

Por fim, uma terceira leitura versa que a casa se manteve aberta, mas passará por um processo de subtração de telhas, de portas e louças do banheiro, o que foi dilapidando a casa até impossibilitar seu funcionamento (entrevistados E6, E7, E9 e E12). Aventamos que possa ter ocorrido um incentivo ao roubo da cultura material por parte do grupo possuidor do terreno, como forma de acelerar a destruição do local. Ou, de forma concomitante, que a população do entorno, a partir da necessidade de construir suas residências, tenha atuado nesta subtração. Em ambos os casos o resultado foi o mesmo: a retirada de material do local e sua dilapidação. É bom ressaltar que as escavações arqueológicas empreendidas não identificaram, por exemplo, portas ou janelas no registro arqueológico, o que é indiciático de que eles já não compusessem a casa no momento de seu fechamento e destruição. Não contando com verbas para as reformas, a casa teria sido abandonada ao seu novo dono, o que nesta versão não impediu seu funcionamento.

É sobre estas três vertentes que este artigo se centrará na elucidação do processo de arruinamento do local, ou seja, como o terreiro foi destruído, abandonado ou transferido. Cruzaremos os dados das escavações às memórias recolhidas e nessa interlocução observaremos como desenvolveu-se uma memória do processo de destruição que indica a permanência e a perda do teor sacro do local.

2 Coleta de dados na Gomeia

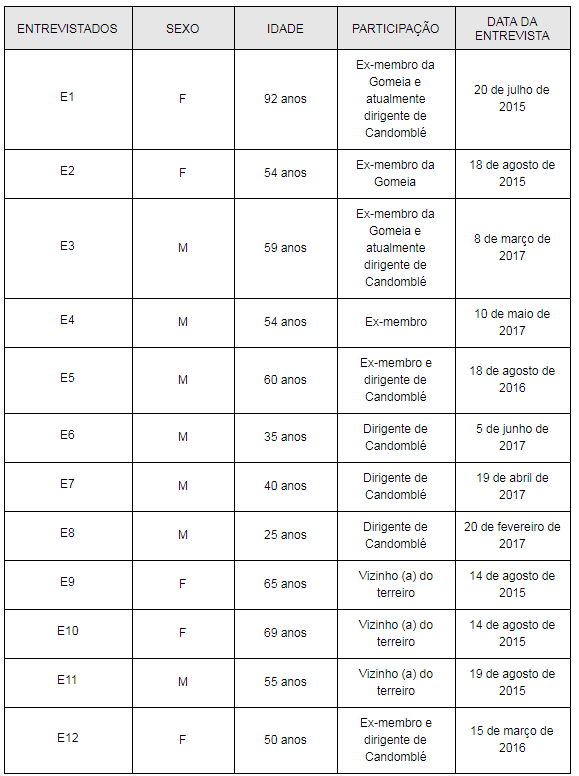

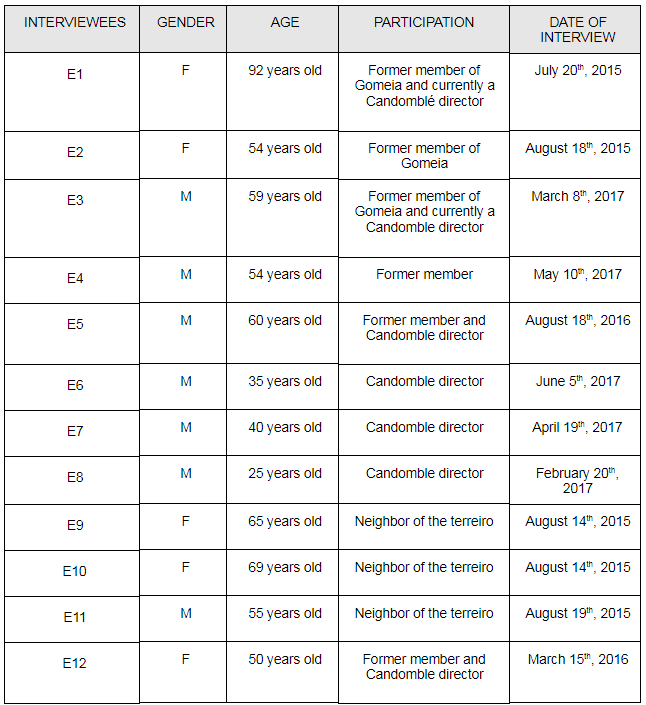

A pesquisa optou por ouvir o máximo possível de “vozes” de como era a Gomeia (fisicamente) e de como foram as suas experiências religiosas8 no local. Assim, selecionamos doze pessoas a serem entrevistadas para este fim antes do início das escavações do local. Inicialmente, selecionou-se alguns ex-membros da Gomeia ainda vivos (cinco pessoas ao todo, sendo três mulheres e dois homens), com idade entre 65 a 85 anos, em média. A escolha deu-se pela constatação de que a idade cronológica mantinha referências com o funcionamento do terreiro, além de averiguar-se com outros dirigentes quanto a participação dos entrevistados na trajetória do terreiro. Estes primeiros entrevistados são, na atualidade, dirigentes e ogãs de terreiros de candomblé. Destaca-se que destes apenas duas mulheres e um homem mantém-se em locais que se identificam como pertencente a tradição Angola de Candomblé de Joãozinho da Gomeia.

Ainda na amostra, dois outros dirigentes homens foram entrevistados e, apesar de se auto identificarem como Angola e da descendência da Gomeia, seus terreiros caracterizam-se pelo uso de termos e ritos da tradição nagô para as divindades e por se utilizaram ainda de festas para Pomba-gira e Exus Catiços da Umbanda. A idade destes varia entre 65 a 80 anos.

Realizamos ainda a entrevista com descendentes de casas que se auto identificam como pertencentes a tradição da Gomeia, sendo dois homens entrevistados. As idades médias estão entre 25 a 35 anos. Estes não residem no Rio de Janeiro, sendo um morador do Recife (PE) e outro do estado de São Paulo. Devido à distância, estas entrevistas se deram por meio de videoconferência com o envio prévio de um roteiro de assuntos. A filmagem foi transcrita em momento posterior à sua realização e, como as demais, seguidas de liberação de utilização por meio de termo de cessão de imagem e áudio.

A pesquisa ouviu ainda moradores do entorno do terreno onde situa-se a Gomeia (ao todo, três pessoas), sendo duas mulheres e um homem, todos com mais de 60 anos de idade e que residem no local desde a década de 1960, tendo possuído contato com Joãozinho da Gomeia e com o terreiro em funcionamento.

As entrevistas realizadas não seguiram planejamento prévio. Solicitou-se que falassem de sua correlação com a Gomeia e o que achavam importante sobre o tema. Quando um assunto, tal como a edificação do terreno, necessitava de mais aprofundamento, a pesquisa intervinha na fala solicitando um aprofundamento no tema. Cada entrevista durou, em média, 60 minutos e foram transcritas posteriormente a sua realização. Previamente foram produzidos termos de consentimento para a realização da entrevista, sendo estes assinados autorizando a sua publicação, mas condicionando a não veiculação do nome do participante e a obrigatoriedade de supressão da identificação de pessoas e lugares que pudessem indicar quem seria o/a entrevistada. A especificação dos entrevistados segue na Tabela 1.

A pesquisa arqueológica na Gomeia deu-se entre os anos de 2015 e 2016 em um total de 30 dias de escavação. Estas ocorreram em dois campos, de quinze dias, com a participação de arqueólogos, estudantes de arqueologia da UFRJ, estudantes e pós-graduandos de história da mesma universidade, voluntários e afro-religiosos que se prontificaram a contribuir com a ação. A escavação teve o apoio logístico da Prefeitura Municipal de Duque de Caxias e da Secretaria de Cultura e Turismo do mesmo município. Com este apoio pudemos não apenas limpar o terreno para as escavações, mas também nos utilizarmos de maquinário para a implementação das atividades de verificação do solo.

Após as atividades de escavação, a pesquisa arqueológica na Gomeia obteve uma cultura material que pode ser classificada em três grandes eixos: objetos de uso religioso (referentes ao Candomblé), de usos seculares (aplicados às práticas do cotidiano não religioso) e os mistos (classificados assim pela dubiedade de estarem ou em contextos religiosos ou nas práticas do dia-a-dia). Esta clivagem permitiu a pesquisa observar que um terreiro é também espaço de moradia, de alimentação e de outros elementos que, apesar de conhecidos na atualidade, não se sabia se deixariam vestígios no registro arqueológico.

Esta cultura material foi classificada nas seguintes categorias de materiais constituintes: objetos metálicos, vítreos, orgânicos, cerâmicos (faianças e barrarias), tecidos, plásticos e rochosos. Isso permitiu inferir formas de utilização, ritos, práticas do cotidiano, além de averiguar a profundidade histórica da utilização de alguns elementos, como o plástico, por exemplo, dentro de terreiro de candomblé.

Pelo obtido, fica claro que as práticas religiosas do Candomblé deixaram vestígios no registro arqueológico. Nossa amostra obteve 278 peças de matérias identificados como seculares (42,7% da amostra), 177 referentes aos religiosos (27,2%), 166 considerados como mistos (26%) e 30 peças sem identificação (4,1%). Se somarmos os valores mistos aos religiosos obteremos um valor de 455 peças que indicam práticas religiosas (53,2% do escavado). Ou seja, pela soma realizada, mais de 50% de nossa cultura material escavada representa práticas, ritos e objetos de cunho religiosos no registro arqueológico do Sítio Arqueológico Histórico do Terreiro da Gomeia.

3 Memórias sobre a Gomeia

Antes de versamos sobre as memórias da destruição, é interessante nos atentarmos às nominações que o Terreiro da Gomeia possuiu em dialeto kimbundo9 recolhido entre as fontes orais: Bantuqueno Ngomenssa Kat'espero Gomeia ou Atim Mossó Candengó Ingomessa Catispero. A primeira forma é passível de tradução – Manso: Aldeia; Bantuqueno: Antigo e correlato aos Bantos na África; Ngomenssa: tambores; Kataspero: Casa de origem de Joãozinho na Bahia e Gomeia refere-se à localização do terreiro em Salvador. Ou seja, poderíamos traduzir como “Aldeia Antiga dos bantos [dos] tambores de Kataspero da Gomeia”. O segundo nome não se encontrou tradução, pois esta não fazia sentido nas tentativas de tradução pelos ex-membros do local10.

A presença de dois nomes, antes de ser um problema relacionado às fontes, é tido neste artigo como um dado a ser trabalhado pelo conceito de memória coletiva (POLLAK, 1989; HALBWACHS, 2006). Para Halbwachs (2006) toda memória possui em sua existência um caráter psicológico: para que algo seja narrado e lembrado, torna-se necessário que haja um indivíduo e a ocorrência de um fato a ser descrito. Nasce assim o que o autor defende ser a memória individual (HALBWACHS, 2006). Contudo, para o autor, mesmo que aparentemente particular, a memória remete a um grupo; o indivíduo carrega em si a lembrança, mas está sempre interagindo na sociedade, já que “nossas lembranças permanecem coletivas e não são lembradas por outros, ainda que se trate de eventos em que somente nós estivemos envolvidos e objetos que somente nós vimos” (HALBWACHS, 2006, p. 30). Desta maneira, temos o conceito e a correlação entre a memória coletiva e a memória individual – uma não existindo sem a outra.

Para o caso da Gomeia é interessante refletirmos como as lembranças emergem dos contatos dos membros e entre as vertentes de memória já descritas. Outro fator a ser considerado foi a constatação de que as memórias da destruição foram “truncadas” e tenderam a uma apropriação e significação dos fatos ocorridos. Assim, o episódio de lembrar ou esquecer de um evento relaciona-se aos lugares que os indivíduos ocupam ou deixam de ocupar como membros de um determinado grupo. Halbwachs (2006) relaciona a memória à participação em um grupo social ou em uma comunidade afetiva. Neste sentido, a simples constatação de que existem duas nominações ao local nos informa como cada pessoa tendeu a desenvolver um processo subjetivo, mas que também é social: lembrar ou esquecer do nome do local ou apenas nominá-la de Terreiro da Gomeia.

Nesse sentido, a memória sobre o nome da Gomeia pode ser compreendida como seletiva: depende dos valores do indivíduo, do momento histórico e dos interesses do grupo social, que sempre se remetem a conflitos de definição das identidades (POLLAK, 1989). Uma ausência de unicidade quanto a nominação do local pode relacionar-se ao estabelecimento de várias vertentes de uma memória coletiva onde cada grupo, ou mesmo indivíduo, tendeu a desenvolver no contexto de filho de santo ou no momento da crise sucessória e posterior arruinamento da casa. Lembrar ou omitir o nome da Gomeia relaciona-se a processos que visam “lembrar”, no sentido de valorizar o passado do local ou de “esquecer” um dirigente e espaço visto como espúrio. Em outra leitura acerca da memória, conforme defende Schwarzstein (2001), “esquecer” também pode se relacionar a sofrimento/dor que as memórias acessadas causam. Não “lembrar” é uma forma de não acessar o trauma.

Assim, dois processos distintos quanto às memórias da Gomeia podem ser observados: o esquecimento do local (e uma consequente dessacralização) e a manutenção de uma memória positiva, que se liga a permanência do sagrado naquele espaço. Neste artigo este axioma nos interessa: na atualidade o terreno onde repousam os restos edificados da Gomeia e a cultura material presente em seu solo, advinda das atividades humanas ali ocorridas, são vistos como sacro aos descendentes do terreiro ou ele não possui nada além de elementos seculares? Estes pólos permitem debater a questão da presença ou ausência da sacralidade nos remanescentes do terreiro. Analisar estas memórias não nos lançam ao passado, mas sim ao presente, pois, “a elaboração da memória se dá no presente e para responder a solicitações do presente” (MENESES, 1992, p. 11). Ou seja, aos atores que ali transitaram, enquanto filhos de santo, o local ainda possui sacralidade ou ela já não existe devido a destruição?

Para a Gomeia, então, as memórias irão se relacionar, primeiramente, com a categoria Tempo: o tempo em que o terreiro funcionou e o tempo em que ele já não funciona. Contudo, a separação é mais um instrumental que visa dar conta de dois momentos da trajetória do local do que, de fato, uma separação de períodos – seja ele o presente ou o passado das querelas religiosas. A partir de nossas entrevistas, observamos que “lembrar” ou “esquecer” desenvolveu um mecanismo de construção de um tempo: no presente se significa ou ressignifica o passado – para alguns o terreiro não possui sacralidade alguma, já para outros, sim. Assim, questões como “quem herdou a Gomeia” e “quem agiu de forma errônea que gerasse o seu fim” suscitaram um aprofundamento nesta correlação entre a memória e a arqueologia. Quem, portanto, é atualmente responsável pelo o que ocorreu? Para as fontes orais consultadas, estar, observar ou transitar nos remanescentes do terreiro, na atualidade, pode significar “reviver” o trauma ou a memória do trauma (SELIGMANN-SILVA, 2005), mas também denota atualizar o debate/querela sobre as ações empreendidas.

Neste ínterim é que a categoria Espaço passa a ter sentido nas elaborações das memórias sobre a Gomeia:

O lugar transcende sua realidade objetiva e é interpretado como um conjunto de significados. Nesse sentido, os monumentos, as obras de arte, assim como cidades são lugares porque são um conjunto de significados. Por outro lado, quando o lugar já não se coloca como um conjunto de significados, na maioria das vezes por causa da tecnologia que transforma todos os lugares em espaços homogêneos, em verdadeiros ‘clones paisagísticos’, os lugares passam a ser não-lugares (LENCIONI, 2009, p. 154).

Para algumas vozes a Gomeia mantém-se terreiro, sacro e o qual se deve obediência por isso, são a concretização material da memória de João Alves e de sua ação. Para outros entrevistados ele não significa mais nada, pois não há nada sacro naquele espaço, pois tudo se transferiu dali. Passa a ser um lugar sem referência, sem sentido, um lugar de passagem e sem fixação. Assim avalia o entrevistado E4: “Ali não tem mais nada. Tudo foi levado para [suprimido o nome]. Por que acham que ali tem alguma coisa? Não tem nada, é um terreno vazio”. O entrevistado conclui que: “A Gomeia vive em outro lugar e dentro de mim, mas não ali”.

A partir deste conceito, podemos refletir que se o Tempo e Espaço representam e atualizam um período passado na Gomeia, o valor dado ao local define-se como um sentido para o presente e o futuro. Pensar a relação entre os dois dentro das memórias da Gomeia consiste, de certa maneira, em pensar uma realidade que se estabelece entre o que foi e é o terreiro e aquilo em que se define como identidade presente – o fator que identifica vozes em suas posições na atualidade.

Podemos analisar a dessacralização da Gomeia da seguinte forma: se nada mais naquele espaço é sagrado, seu solo não o é, as estruturas não são e, por fim, até mesmo a memória não é mais sacra, pois este se apagou com o que denominamos de processo de arruinamento do local. Dos entrevistados pela pesquisa, os entrevistados E1, E4, E8 e E10 não acreditam mais que o terreno seja sacro, pois não há mais o que permita ao terreno fazer a intermediação entre o plano espiritual e o material. Se não existem mais objetos sagrados, da mesma forma, nada mais ali se remete ao plano dos deuses. Apagou-se ou extinguiu-se o caráter santo também com a morte do dirigente.

Conforme a cosmologia do Candomblé – Santos (1984) ou Rocha (2000) – se todos os ritos de retirada e transferência do sagrado foram realizados e a nova casa que recebeu este material deu continuidade à Gomeia, ela está viva em outro local. Assim, conforme esta vertente da memória, a descendência de João Alves foi mantida. O que ficou no terreno lembra um determinado passado, mas este encontra-se, na verdade, vivo em outro terreiro. Nada em Duque de Caxias remete ao plano dos deuses. Se eles não moram mais ali, o terreno perdeu seu teor sacro. Esta vertente baseia-se no que denominamos de uma “Crença Oficial”, ou seja, pelos ritos de transferência e pela cosmologia do Candomblé nada mais há ali que permita acessar o sagrado. Esta crença é tão vívida quanto às demais, mas tende a se basear em aspectos religiosos formais.

Em nossa leitura, é interessante destacar que a dessacralização da Gomeia seja, na verdade, um ato intencional, já que eles podem apoiar a continuidade da obra de Joãozinho em outro terreiro que recebeu seus objetos e isto se relacione ainda hoje a uma oposição à sucessora escolhida em 1971. Esta disposição nos indica que, para manter o teor santo, o terreno deveria conter certos elementos que hoje estão ausentes. A dessacralização se deu pela perda de elementos que compunham a ligação entre o mundo físico e o mundo espiritual, cortado o laço está desfeito o sentido sacro dos remanescentes do terreiro.

Para outro grupo, os entrevistados E2, E3, E5, E6, E7, E9, E11 e E12, o terreno da Gomeia nunca deixou de ser sacro, ou seja, ele nunca deixou de acessar o Orum (plano espiritual), permite, hoje ainda, aos adeptos, uma conexão com suas divindades e com as memórias das festas e ritos ocorridos ali. Mesmo com o fim do terreiro, o local não deixou de ser sacro. Uma vez tocado pelos deuses, aquele espaço mantém-se assim eternamente. Para este grupo não importam justificativas “oficiais” da cosmologia do Candomblé, sua “Crença Vivida” se opõe a estes argumentos e mantém a sacralidade da Gomeia. Esta posição baseia-se nas experiências religiosas vividas, mantidas e atualizadas pela memória. O que importa é o que se sente e o que se expressa e não as querelas sucessórias, arruinamento ou transferência dos materiais. Se houve uma intencionalidade de um grupo em comprar o terreno e impedir a continuidade do terreiro, isso não importa, a Gomeia mantém-se viva nas memórias das iniciações, no respeito ao terreno e nas rememorações da figura do dirigente. Como relatou o entrevistado E12:

Isso aqui [o terreiro] ainda tem axé, meu filho. Tem gente que vê o Caboclo [Pedra Preta] aqui de noite. Venha aqui na Quaresma, você mesmo vai vê-lo andando a noite. Não é porque Joãozinho morreu que isso não tem mais valor. Aqui ele plantou o seu caboclo que ele trouxe da Bahia. Mesmo que ele [o Caboclo] não more mais aqui, aqui ainda é o Terreiro da Gomeia. É aqui que fui feita, é aqui que bato minha cabeça. Tudo aqui tem axé e não é o que houve que muda isso.Isso aqui [o terreiro] ainda tem axé, meu filho. Tem gente que vê o Caboclo [Pedra Preta] aqui de noite. Venha aqui na Quaresma, você mesmo vai vê-lo andando a noite. Não é porque Joãozinho morreu que isso não tem mais valor. Aqui ele plantou o seu caboclo que ele trouxe da Bahia. Mesmo que ele [o Caboclo] não more mais aqui, aqui ainda é o Terreiro da Gomeia. É aqui que fui feita, é aqui que bato minha cabeça. Tudo aqui tem axé e não é o que houve que muda isso.

Sobre este ponto, é interessante analisarmos outro aspecto de manutenção da sacralidade narrado pelas fontes e observado in loco pela pesquisa: o terreno nunca foi invadido por pessoas para moraram no local, fato comum na Baixada Fluminense quando se tem um terreno vacante2. Concomitante a isso, a creche prevista de ser construída pela Prefeitura Municipal de Duque de Caxias nunca foi erigida, nada desenvolveu-se no local após a destruição das áreas edificadas. A não ocupação humana nos é indicativa de que a população do entorno do terreiro ainda hoje reconhece o terreno como sacro e por isso é um tabu ou impeditivo a sua ocupação. Morar ou construir ali poderia levar a cólera de Joãozinho sobre quem realizasse essa ação.

Por estes exemplos a pesquisa pode averiguar que o sagrado está presente no terreno. Ele nunca foi extinto e, pelo observado, não o será. Como expressou o entrevistado E2: “enquanto a memória de Joãozinho estiver viva, a Gomeia também estará. Ali, meu filho, o axé nunca morre. Mesmo não tendo nada, tem axé e devemos respeitar isso. Aquilo ali é solo sagrado”. É esta rememoração que mantém a sacralidade do espaço. Visitá-lo aciona o “lembrar” sobre a iniciação, as vivências de festas ou as confraternizações. Isso atualiza e reelabora o sentido de pertencimento ao local, independentemente de estar conservado ou não.

Durante escavações arqueológicas empreendidas em 2016 recebemos alguns ex-membros da Gomeia que foram visitar as atividades. Em especial uma senhora, com oitenta anos e mais de cinquenta de iniciada por João Alves, nos forneceu argumentos que validam a leitura deste artigo de que o caráter santo do local não se perdeu. Esta senhora, com imensas dificuldades de locomoção, ao chegar na área que estava sendo escavada, tirou suas sandálias e prestou reverência às estruturas em evidenciação. Ela nos informou que a deferência era necessária pois a Gomeia nunca havia sido extinta, ela estava ali naquelas estruturas. Emanavam energias daqueles restos erigidos. Segundo sua fala: “Eu fui feita aqui, ali dentro daquele quarto que vocês tão [sic] vendo. Aqui é meu sagrado e ele nunca se perdeu. Eu fico feliz em poder ver ele de novo. Nossa, eu passei tanta coisa boa aqui. Eu fui tão feliz aqui. Olha quanta energia emana dali”.

Assim, nos é claro que nunca houve uma dessacralização daquele local, sendo esta nossa posição neste artigo. Houve um processo físico de apagamento e destruição das estruturas precedido pela transferência de cultura material para outro terreiro. Contudo, o caráter religioso nunca fora extinto com estes eventos. A “Crença Vivida” atualiza e mantém operante a categoria sacra do local. As memórias sobre o terreiro “lembram” e mantém vivas as recordações e o tom sacro daquele local.

O que o exemplo desta senhora nos permite averiguar é que a memória e crenças vividas se mantém sagrada, pois geram um sentido de pertencimento, de vida e de identidade, mesmo não havendo mais a Gomeia. Portanto, as vivencias religiosas tidas na Gomeia não apenas dão sentido à memória, mas a anima (no sentido de dar vida e sentido sobre esta). São elas que mantém a sacralidade do local.

Cria-se uma memória coletiva que não apenas mantém viva a memória do dirigente, mas “luta contra a inércia do cotidiano, captura os fragmentos que sente significantes ou úteis e trabalha por dinamizá-los” (ZUMTHOR, 1997, p. 27). A memória sacra não anula as querelas passadas na sucessão, mas as reelaboram, excluindo dela elementos que destoam de um passado que se deseja lembrar e manter. Nesse sentido, a Gomeia nunca deixou de ser sacra. Todos estes pontos nos indicam que permanece no local o signo do sagrado.

4 Leitura arqueológica do processo de arruinamento no Terreiro da Gomeia: algumas conclusões

Do ponto de vista material o que significou a morte de João Alves em 1971? Como vimos, houve uma disputa em torno da sucessão. O que isto impactou na manutenção da Gomeia até meados dos anos de 1985 ou 1988, quando o terreiro fechou? Invariavelmente, os dados arqueológicos e orais indicam um processo de arruinamento da casa. Obtivemos três vertentes orais sobre o fim da Gomeia e este processo: a depauperação das estruturas, o abandono e depredação dos espaços erigidos (seguido de uma subtração de elementos) e a transferência dos objetos de Duque de Caxias para outro terreiro.

Podemos pensar que, se uma leitura é verdadeira, as outras não seriam. Se houve um abandono, não é possível que tenha havido uma transferência de cultura material, por exemplo. Contudo, atrelando os dados arqueológicos às fontes orais, a pesquisa arqueológica concluiu que cada um dos grupos de interesse narrou um dos elementos que levou ao fim da Gomeia. Eles não se opõem, mas são, na verdade, complementares.

Este fato nos permite compreender como diferentes versões sobre o fim da Gomeia foram elaboradas a partir do que Parés (2007) indica ser uma “simplificação seletiva” das memórias: no caso em questão, para reforçar ou mesmo destacar uma posição no litígio sucessório ou quanto ao término do terreiro, as lembranças são simplificadas, redirecionadas ou mesmo dilapidadas para a construção de uma narrativa que privilegie um fato ou uma posição religiosa e política.

Assim, para o caso da destruição, é plausível concluirmos que houve um abandono parcial do terreiro após alguns anos de continuidade da Gomeia. Um dos grupos que assumiu o poder não deve ter conseguido manter a ordem e o funcionamento da casa, já que a sucessão era questionada. Concomitante a este fato, com a ausência de um dirigente aceito por todos os grupos de interesse e o parcial abandono das dependências que só eram utilizadas durante as festas, eventos de subtração de elementos estruturais (portas, janelas e etc.) devem ter ocorrido por membros de grupos rivais que desejassem macular a imagem de dos que regiam o terreiro.

Nesse interregno ocorreu o evento de compra do terreno da genitora de Joãozinho da Gomeia por um grupo de interesse entre os membros da Gomeia. Esta compra tinha por função manter o terreiro em funcionamento, mas percebemos que o resultado não foi esse, pois acirrou os embates. Este grupo que adquiriu o terreno optou por transferir os materiais religiosos mais importantes do local para outro terreiro, permitindo que os demais membros retirassem os seus assentamentos. Assim, transferiam-se elementos do dirigente. Mantinha-se assim uma continuidade do terreiro não mais na Gomeia de Duque de Caxias, mas em um terreiro que se assumiu como continuação da tradição do dirigente. Com a transferência dos materiais, a casa tendeu a encerrar suas atividades definitivamente, o que esvaziou o terreiro e transferiu para outras casas os membros litigantes a esta ação. Neste momento os grupos de interesse arrefeceram suas atuações, pois não havia mais nada pelo que brigar, tudo estava encerrado e transferido.

E como deu-se a destruição do local? Cruzando os dados os arqueológicos e os orais, podemos concluir que, com a morte de João Alves, os recursos para a manutenção da casa diminuíram drasticamente, pois não havia mais, por exemplo, o dinheiro vindo da mesa de jogo de búzios (uma das principais fontes de recursos de qualquer terreiro), assim a renda para financiar a compra de insumos tendeu a diminuir. Ao mesmo tempo, após a morte do dirigente, as querelas políticas se avolumaram e tornaram assuntos como a manutenção das estruturas secundários. Elementos que viessem a se deteriorar após o ano de 1971 podem não ter sido repostos, já que não foram identificados nas escavações empreendidas ou foram subtraídos em momento não definível.

A partir dos dados da escavação, é possível interpretarmos que a direção da casa pudesse se utilizar de cotas ou mensalidades para a manutenção dos espaços, mas é interessante destacar que mesmo esse afluxo financeiro podia não ser o necessário para a manutenção das dependências do terreiro. Assim, a pauperização do local teve início. É possível concluir que se consertava o essencial e necessário, deixando-se de lado outros elementos menos importantes ou que pudessem ser feitos em outros momentos.

Como o terreiro passou por um processo em que o/a dirigente não mais residisse nele, a Gomeia passou por períodos de quase ausência populacional12, pois os adeptos só se dirigiram ao local em dias de ritos e festas. A possibilidade de furto de elementos construtivos deve ser considerada neste contexto e não foi impossível de ocorrer. Como já exposto, aventamos que membros litigantes ou ainda outras pessoas podem ter feito esta ação, fato expresso nas entrevistas recolhidas.

Para a pesquisa em curso e, através dos dados orais coletados, neste processo em que o local ia se arruinando uma das soluções encontradas foi, então, transferir os elementos religiosos para outro terreiro, pois a devastação e/ou destruição da Gomeia encontrava-se em curso e era necessário salvaguardar a memória de João Alves. De fato, isto ocorre e não podemos emitir um juízo de valor sobre a ação. Se ela teve interesses meramente religiosos de manter o legado de Joãozinho ou se foi uma ação que visava dar notoriedade e uma ideia de continuidade do terreiro em outro local13, não podemos inferir sobre isso.

Contudo, as análises arqueológicas realizadas junto aos dos remanescentes edificados do local e junto a cultura material, nos indicaram que os espaços erigidos passaram por um outro processo: houve uma destruição das estruturas com o uso de maquinário (possivelmente um trator). Ao observarmos alguns contextos arqueológicos isso ficou claro à pesquisa. Nossa leitura faz-se entendendo que, uma vez transferida a cultura material, houve a intenção de inutilizar o espaço. Como ocorriam ainda “vozes” e posições que tensionavam mantê-lo aberto, fazia-se necessário barrar isso. A proibição da entrada no local foi seguida de uma destruição do mesmo, pois nada mais havia de religioso ali. A destruição deu-se com a utilização de um maquinário que adentrou o terreiro e no sentido norte-sul (do portão para dentro do terreno) e destruiu as paredes do barracão, as pilastras que o sustentavam, além das casas de santo e demais estruturas. Nossa leitura baseia-se na verificação de que as estruturas de ferragem que compunham as vigas de sustentação das edificações encontraram-se todas retorcidas e destruídas neste sentido (norte-sul), o que indica um evento único e violento de destruição.

Esta situação também foi analisada corrobora com nossa teoria durante a escavação do Ariaxé do Terreiro14. Na camada superior da estrutura havia uma enorme quantidade de telhas quebradas que encobriram a estrutura associadas a um sedimento arenoso, o que defendemos ser a camada com a presença de material arqueológico. A disposição de telhas de amianto que compunham o teto de forma tão quebradiça deve ter se dado pelo uso do maquinário para a destruição do telhado do barracão.

O arruinamento da Gomeia, então, deu-se por uma sucessão de eventos de desmonte/furto seguido por uma destruição mecânica? Nos ficou claro que, para barrar a possibilidade da manutenção do local, após a transferência de sua cultura material religiosa para outro terreiro, tenha sido efetuado uma destruição de suas estruturas, o que impediria uma reocupação deste (se ela já não estivesse impedida pela posse do terreno por um dos membros litigantes que realizaram a referida transferência). Assim, destruir significava inutilizar os espaços do local. Ou seja, para determinado grupo, o espaço não era mais sagrado, ou seja, passivo de intervenção para gerar a destruição.

Assim, o processo de arruinamento não foi responsável apenas pela destruição da Gomeia, mas também por um determinado apagamento de sua presença da paisagem de Duque de Caxias. Afinal, se o que não é visto não é lembrado, destruir a presença física do terreiro é apagar a sua presença e, de certa maneira, as suas memórias. Esta afirmação faz-se com a constatação de que, após a destruição, implementou-se uma camada de aterro com solo argiloso que visava, em nossa leitura, apagar a presença do terreiro. Conforme averiguado pelas escavações, esta camada encontra-se sobre os remanescentes da destruição com a clara intenção de aterrá-los. Esta camada com função de selamento indica uma intencionalidade em apagar e soterrar a presença física da Gomeia. Sua aplicação pode ser lida como uma ação intencional que visava descaracterizar o terreno para uma possível venda ou mesmo para anular a presença ou reminiscência do sacro no local. Uma vez soterrada a Gomeia, também o seu sacro não seria mais visível e só poderia ser acessado na outra casa em que os objetos transferidos se encontram. Esta ação também pode ser entendida como a vitória de um dos grupos litigantes sobre os demais, pois soterrar aciona o signo do esquecimento.

Do exposto até aqui, portanto, definimos que o processo de arruinamento da Gomeia caracterizou-se por uma sequência de eventos que se iniciaram ainda com o terreiro em funcionamento nos eventos pós falecimento do dirigente, mas foi rapidamente finalizado com a ação de um maquinário que destruiu as estruturas edificadas do local como forma de impedir sua continuidade. Uma ação política cara ao grupo que a empreendeu, pois apagou da paisagem de Duque de Caxias um dos terreiros referenciais para a formação do Candomblé carioca e paulista (SILVA, 1995).

Os dados arqueológicos obtidos com as campanhas de escavação nos mostraram que não havia no registro arqueológico portas, janelas ou outros elementos similares, o que pode ser indicativo de que estes já não compunham a Gomeia no evento final de destruição. A quantidade de telhas quebradas, também presente no solo e impossível de contabilização, nos fornecem a leitura de que estas não foram totalmente subtraída, mas também foram destruídas pelo maquinário. Da mesma forma, a ausência de louças sanitárias no mesmo registro reforça ainda mais nossa leitura: foram retiradas antes da destruição.

Conclusivamente, as memórias da destruição, quando unidas, apresentam um contexto de dilapidação tanto da memória física do terreiro, mas também a tentativa de uma dessacralização do local. Contudo, mesmo a ação física não apaga as experiências e vivências do sagrado pelo qual parcelas de nossas fontes viveram. Portanto, a sacralidade do terreiro nunca se desfez, talvez pela suspensão repentina das querelas com a destruição, mas sobretudo pela ação da memória que ressignifica constantemente o que foi vivido. Isto gera um sentido de continuidade e de pertencimento, tal como expresso por parte das fontes ouvidas.

Vivência, experiências religiosas, amizades e construções de novos arranjos familiares e religiosos foram interrompidos quando o tecido religioso não conseguiu solucionar seus conflitos ocorridos na época da sucessão de liderança. O impasse gerado pela memória, atualizada a partir das escavações realizadas, manteve-se (e mantém-se), dando origem a uma polifonia de valores junto ao grupo – o que ficou de legado da casa? A liderança era capaz? Por que houve o arruinamento? Defendemos que a figura de João da Pedra Preta era o agente político que aglutinava todos os grupos políticos que já deveriam estar presentes enquanto este dirigia o local. Mas, com a sua morte, criou-se um estado em que estes, não se entendendo quanto às demandas de quem o sucederia, tenderam a dissociar-se e criar memórias e narrativas próprias que correlacionam seus anseios e visões sobre a continuidade da Gomeia. Assim, se por um lado o terreiro foi esvaziado de significados até ser abandonado no final da década de 1980, ao mesmo tempo vemos a construção histórica de narrativas que justificam tanto a permanência dos grupos políticos de interesse quanto a sucessão. Estes últimos tenderam a associar-se e criar narrativas que os fazem presentes até a atualidade como os que “deveriam ter governado”, mas também dão sentido a um conflito gerado por si mesmos.

Assim, do ponto de vista material, o processo de arruinamento da Gomeia pode ser entendido como uma questão micropolítica não solucionada e que culminou em uma sequência de ações – abandono, transferência de cultura material ou subtração desta – regimentadas por grupos de interesse diversos quanto a continuidade do local e sua liderança. Assim, a desagregação da Gomeia não se deu apenas no plano material, mas ocorreu também junto aos indivíduos que compunham o terreiro. As memórias coletadas pela pesquisa apresentam como estas memórias da destruição atualizam o debate sobre a sucessão e ainda remetem ao tema de quem deveria ter dado sequência ao terreiro.

Ao inserirmos o dado arqueológico nesta pesquisa, percebemos como o rememorar é uma “ilha de edição” que seleciona fatos e atores para dar sentido a determinados pertencimentos ou mesmo posições políticas, nunca isentas de sentido que dá pela posição do ator no contexto de conflito ocorrido. A materialidade dos estudos arqueológicos vem congregar mais uma forma de analisar como esta “edição” tende a ser seletiva e se atualizar no presente dos discursos recolhidos.

Referências

CAPONE, S. Le pur et le dégénéré: le candomblé de Rio de Janeiro ou les oppositions revisitées. In Journal de la Société des Américanistes, p. 259 - 292, 1996.

CHEVITARESE, A. L.; PEREIRA, R. O desvelar do candomblé: A trajetória de Joãozinho da Gomeia como meio de afirmação dos cultos afro-brasileiros no Rio de Janeiro. In Revista brasileira de história das religiões. Maringá, n. 9, p. 43 - 65, 2016.

GAMA, E. C. Mulato, homossexual e macumbeiro: que rei é este? Trajetória de Joãozinho da Gomeia (1941-1971). Duque de Caxias: APPH-CLIO, v.2, 2014.

HALBWACHS, M. A memória coletiva. São Paulo: Centauro, 2006.

JORNAL CORREIO DA MANHÃ. Rio de Janeiro. 9. dez.1951.

JORNAL CORREIO DA MANHÃ. Rio de Janeiro. 3. abr. 1971.

JORNAL CORREIO DA MANHÃ. Rio de Janeiro. 5. abr. 1971.

LENCIONI, S. Região e geografia. São Paulo: EDUSP, 2009.

MENESES, U. T. B. A história, cativa da memória? Para um mapeamento da memória no campo das Ciências Sociais. In Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros. São Paulo, n. 34, p. 9 - 24,1992

MOTA, M. S. C. Nas terras de Guaratiba: uma aproximação histórico-jurídica às definições de posse e propriedade da terra no brasil entre os séculos XVI – XIX. 334 f. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências Sociais em Desenvolvimento, Agricultura e Sociedade). Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, 2009.

PARÉS, L. N. A formação do candomblé: história e ritual da nação jeje na Bahia. São Paulo: Editora da UNICAMP, 2007.

PEREIRA, R.; MOURÃO, T.; CONDURU, R.; GASPAR, A.; RIBEIRO, M. Inventário nacional de registro cultural do candomblé no Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Musas Projetos Culturais/IPHAN, 2012.

PEREIRA, R. Sucessão e liminaridade: o caso do terreiro da Gomeia. In Tessituras. Pelotas: Revista de Antropologia e Arqueologia. p. 372 - 402, 2015.

POLLAK, M. Memória, esquecimento e silêncio. In Estudos históricos. v. 2, n. 3, p. 3 -15, 1989.

ROCHA, A. M. As nações Kêtu: ritos e crenças: os Candomblés antigos do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad, 2000.

SANTOS, J. E. Os nagô e a morte: Padê, Asèsè e o culto Égun na Bahia. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1984.

SCHWARZSTEIN. D. História oral, memória e histórias traumáticas. In Revista História oral, n.4, p. 73 - 83, 2001.

SELIGMANN-SILVA, M. O local da diferença: Ensaios sobre memória, arte, literatura e tradução. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2005.

SILVA, V. G. Orixás na metrópole. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995.

THOMPSON, E. P. The poverty of theory and other essays. London: Merlin, 1978.

ZUMTHOR, P. Tradição e esquecimento. São Paulo: HUCITEC, 1997.

1 Para esclarecimento dos termos do candomblé utilizados no artigo, indicamos o acesso ao dicionário. Disponível em: <http://vidademacumbeiro.blogspot.com.br/2008/11/dicionrio-yoruba-portugues-5a-ed.html> Acesso em 01 fev. 2017.

2 As fontes orais divergem quanto a idade da menina: horas ela tem oito anos e horas possui dez. Os jornais sempre a indicam com oito anos, mas a descrevem com dez anos em apenas um ano após o falecimento de Joãozinho. Assim, a idade real é incerta e aproximada.

3 A datação advém do material arqueológico que permitiu a inferência desta data por meio do uso de moedas presentes no registro arqueológico para tal fim.

4 As fontes orais divergem quanto a idade da menina: horas ela tem oito anos e horas possui dez. Os jornais sempre a indicam com oito anos, mas a descrevem com dez anos em apenas um ano após o falecimento de Joãozinho. Assim, a idade real é incerta e aproximada.

5 Conforme o Correio da Manhã de três de abril de 1971, Sandra ou Seci Caxi foi a escolhida pelos búzios para subir ao comando da Gomeia. Contudo, a menor foi proibida pelo Juiz de Menores da Comarca de Duque de Caxias – Eduardo Canotta – de assumir o cargo devido à idade. Esperava-se pronunciamento da Curadora do caso, Maria de Andrade Esqui, sobre o assunto. Para o Juiz de Menores de Niterói (comarca que abarcava Duque de Caxias), Jessir Gonçalves da Fonte, as festas, os horários e a presença de bêbados poderiam influir negativamente da formação moral da criança, o que poderia impedi-la de assumir o cargo. O mesmo jornal, publicado no dia cinco daquele mês indica que o Juiz de Menores era filho de santo da Gomeia, o que poderia passar ao público alguma lisura quanto ao processo ou mesmo que este era direcionado para que Sandra não assumisse o cargo.

6 Cadeira de onde os dirigentes do candomblé comandam as festas e ritos. Representa materialmente seu poder de comando.

7 Alguns objetos pessoais de João Alves estão sob a posse do Instituto Histórico de Duque de Caxias. O local localiza-se no subsolo da Câmara dos Vereadores do município, situada na Rua Paulo Lins, 41 - Jardim Vinte e Cinco de Agosto, Duque de Caxias - RJ.

8 Para o presente artigo, a partir do conceito de Experiências Religiosas de Thompson (1978), defendemos que ela deva ser conceituada e entendida como o conjunto de informações, de contatos e mesmo de circulações que os entrevistados tiveram durante sua vida dentro do Terreiro da Gomeia.

9 Dialeto africano utilizado em terreiros da tradição Angola de Candomblé no Brasil.

10 Apesar da referida tradução, Nicolau Parés (2007) nos fornece outra origem para o termo Gomeia: estaria relacionado a um terreiro, da tradição Jeje, denominado de “Agomé” que se situava na região onde João Alves abriu sua roça em Salvador: “o ‘terreiro de Agomé’ (variante Agomea) localizado em Campinas, nas imediações de Pirajá, na freguesia da Penha [em Salvador] [...] O nome do terreiro deriva seguramente de Agbomé, atual Abomey, capital do antigo reino de Daomé [...] É provável que esse terreiro de Agomé tenha dado nome ao bairro da Gomeia, localizado perto de São Caetano, ao Sul de Campinas. Arthur Ramos já sugeriu ser o topônimo ‘uma corruptela da forma portuguesa do Dahomey (Agomé, Dagomé nos documentos antigos), o país dos geges’ e, em apoio dessa interpretação, Edison Carneiro acrescentava que ‘dois dos três candomblés geges da Bahia – os de Manuel Menezes e Falefá – estão localizados na vizinhança da Gomeia. Também funcionou ali o terreiro de Joãozinho da Gomeia que, embora de nação angola, apresentava, como nota Ramos, importantes ‘intromissões jejes’. Testemunhas oculares das festas daquela casa lembram que ‘tinha muitas pessoas jejes, era angola, mas tocava candomblé jeje, fazia muito Omolu, Oxumarê, Nanã’” (PARÉS, 2007, p. 154).

11 Para este ponto, ver o texto de Mota (2009).

12 Uma das fontes nos narra esse ponto da seguinte forma: “Ah, meu filho, depois que Pai João morreu o terreiro ficou vazio. Antes ele mantinha a gente lá com comida e roupa, mas depois que ele morreu a gente teve que se virar. Todo mundo morava junto e vivia lá [no terreiro] junto. Depois [da morte do dirigente] não tinha mais dinheiro pra [sic] nada. O que entrava era para manter a casa, fazer uma pintura nova pra [sic] uma festa. Mal dava pra [sic] gente comer. Aí tivemos que dar um jeito. Eu fui morar em outro lugar, a [suprimido o nome] também. A [suprimido o nome] abriu seu terreiro em [suprimido o nome]. Depois que tudo ficou vazio aí é que a coisa pegou, começaram a roubar tudo. Teve gente que levou coisas do terreiro pra [sic] casa. Até garfos eles levaram de lá. Aquilo ficou ao Deus dará. Não tinha Pai João para comandar as coisas”.

13 Uma das fontes descreve: “Dizem que levaram as coisas apenas para fechar a Gomeia, que não era mais possível mantê-la aberta. Mas acho que, na verdade, [suprimido o nome] só levou as coisas para se dizer herdeiro de Pai João. Não precisava disso, não tinha por que nos tirar dali e levar as coisas. Era só ter união e continuar a casa. Foi uma pena levaram de lá as coisas, Pra [sic] que? Só pra [sic] levar o nome da Gomeia junto? Acho que foi isso, eles queriam levar a Gomeia com eles e não Pai João”.

14 O ariaxé pode ser um sulco construído no solo, uma pilastra que se aproxima do teto ou mesmo um poste ligado ao telhado do terreiro e que tem por função ligar os planos material e religioso para as trocas de energia e presentificação das entidades em festas no terreiro. É, ainda, um dos centros de energia que tem por função manter o terreiro em funcionamento. Ele possui, via de regra, um assentamento de orixá/nkisi implantado pelo dirigente do local.

Memories of Terreiro da Gomeia: between sacredness and desacralization

Rodrigo Pereira is a Social Scientist and holds both a Master in Social Sciences and Archeology as well. He is a member of the Laboratory of History of Religious Experiences and a Lecturer at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, where he studies and guides research on religions and religiosities, especially Afro-Brazilian religions. In Anthropology, he explores Candomblé, debating micropolitics in terreiros, succession events and liminarity-related themes.

How to quote this text: PEREIRA, R. Memories of the Terreiro da Goméia: between sacredness and desacralization. V!RUS, Sao Carlos, n. 16, 2018. [e-journal] [online] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus16/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 05 July 2025].

Abstract:

Memory can be conceptualized as that human capacity to preserve specific information, feelings, and experiences that allow individuals to update past impressions or information, or to reinterpret them as the past. However, such action frequently takes place in the present and is not imbued with positions on the recollected facts. From archaeological excavations undertaken in the remnants of terreiro da Gomeia (at the city of Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro State) and the recollections gathered about its operation and succession crisis, this article aims to discuss the function of memory in the construction of narratives about that place, its functioning, the succession, and later destruction crisis. Gomeia was one of the major candomblé spots at Rio de Janeiro, having worked from 1951 to 1971 when its leader passed away and an inheritance crisis began. The formation of three strands on these facts demonstrates how political memory is, and how it aims at supporting some positions and points of view. The collected memories in research will be used as one of the supports for the construction of the archaeological interpretation of this candomblé terreiro at Rio de Janeiro.

Keywords: Memory, Archeology, Candomblé,Terreiro da Gomeia

1 Introduction1

In the 1940s a Bahian babalorixá migrated to Rio de Janeiro. João Alves Torres Filho, with the nickname of Joãozinho da Gomeia, left Salvador and went to the then Federal Capital. Tata Londirá, his religious name, is identified as belonging to religious tradition of Angola Candomblé and Caboclo of Bahia (Chevitarese; Pereira, 2016). We consider this situation one of the reasons for the transfer of the leader to Rio de Janeiro. As Capone (1996) argues, he was included in a "religious march" of pais/mães de santo 2who left Bahia and settled in Fluminense soil in search of a religious market not dominated by the yalorixás of Salvador. Another reason for the march was the prejudice that the babalorixá suffered for being homosexual, dancer and musician, which may have been decisive for Rio de Janeiro to be seen as a place that allowed a new trajectorY (Chevitarese; Pereira, 2016).

In 1951, Joãozinho da Gomeia inaugurated his terreiro in the midst of a wide coverage of the newspapers, because the leader was not only a father of a saint, but already he was active in the carnival of Rio de Janeiro (jornal Correio da Manhã, December 9, 1951). In the carnivals of the 1950s and 1970s he performed at parties in clubs in the Southern Zone, paraded in the samba schools and also acted as one of the choreographers of the Casino Urca and João Caetano Theater, all in the then Brazilian capital (Chevitarese; Pereira, 2016). The Manso Bantuqueno Ngomenssa Kat'espero Gomeia or terreiro da Gomeia began its activities by installing itself in the city of Duque de Caxias - metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro. The house became a referential point for artists and politicians who sought more than religious advice, the friendship with Joãozinho da Gomeia rendered recommendations to these and works to facilitate political and economic situations (Chevitarese; Pereira, 2016).

filhos de santo 3Seci was the daughter of Kitala, one of the daughters of a saint who moved from Salvador to Rio with Father João. Kitala was his elder's daughter and we respected her for it. She had axé and command strength .... Seci ?? Seci did not have this, never had. She [Kitala] was the mother of Seci's blood, but that made the girl was Joãozinho. You know, carnal mother can not start her own daughter. Seci was born within Gomeia. Who gave birth was not a doctor, but the caboclo of Father João. After she was born Iansan came down in Father João and indicated that the girl would be his successor, but we never gave ball to that, we did not expect him to die how he died The Seci was made pro [sic] holy baby because it was a very sick, weak child ... Seci was raised outside the terreiro, there in Copacabana. She was raised by a godmother who studied, put her in French, in dance. But everything was paid for by Father João. She [Seci] had the good and the best, but she was not raised with us in Gomeia. She showed up there just for [sic] parties. When she was chosen for Gomeia we knew she was weak for the thing, she would not have the pulse to command Gomeia. She was a child. How could a child stand in front of things? I could not and we could not let it all die (E 12, our translation).

The succession was fierce when the biological mother of the deceased leader chose to sell the land where Gomeia was located and move to Salvador (BA). As it was verified among the oral sources, this act led to a certain group of filhos de santo to obtain the legal possession of the terreiro, which influenced the continuity of the place. The successive quarrels were exponentiated due to an accusation of "theft" by opposition groups to what it acquired from the terreiro and its dependencies.

terreiro da Gomeia entered into disuse or total abandonment only in the late 1980s, the approximate date for this was the period from 1985 to 19884, because the oral sources are not sure and unanimous about the fact. However, oral data indicate that the site continued to initiate filhos de santo through Mametu Kitala and others who remained in the area during the 1980s. However, the severe crisis and closure of the site prevented this continuity.

Until the decade of 2000 the land was used by the surrounding population as a space for children to play and for the celebration of June festivals. In the following decade a small wall was erected for the accommodation of the "Gomeia Sport Club" - a football team of the residents of the street - which did not last for a long time, since the place was used as a truck parking lot (Pereira et al, 2012). The destination of the area of Gomeia was defined in 2003, when the city of Duque de Caxias expropriated the place for the construction of a day care center (Gama, 2014). However, the project was not implemented by the municipality, leaving the land unused until the present time.

It is noteworthy that the events of succession were decisive for the establishment of a process that led to the disaggregation of the erected spaces of the terreiro. Conflict, or even disregard, may have been one of the factors that triggered the process of site destruction, either by the subtraction of elements or even by the lack of maintenance. In this article we will find out in this how a series of actions were carried out in the place that disarmed in the disaggregation and / or destruction of the spaces erected by Joãozinho da Gomeia.

After the conflict was established, in non-consensual chronological time between the oral sources, since the Justice had prevented the child chosen by the búzios from assuming total command of the terreiro5, a filho de santo in the house, through consultation with the group, took charge of the purchase of the land where Gomeia was located, since Joãozinho's mother had chosen to return to Bahia after the death of her son. The orality is unanimous in stating that the filhos de santo, each in his own way, contributed to the acquisition of the place, always expressing the idea that it remained open. Apparently, this has happened, but at this point the consequences vary according to the interviewee. Three memories of the destruction and closure of the place were formed. For one group (interviewees E2, E3, E5 and E11) the purchase was followed by an expulsion from the litigant group which saw succession in Sandra. This action would have occurred with the help of police forces that closed the access to the street where the Gomeia is located so that the personal and religious objects of this group were removed from the terreiro and placed in the street. When the litigants were able to arrive in front of this one, only they were able to collect their settlements, clothes and other ritual objects and were no longer allowed to enter the space. With the closure, part of Gomeia's material culture was transferred to another terreiro outside Rio de Janeiro. For this place they would have been transferred, according to orality, the settlements of the house6, the throne of the leader7 and object of this8.

For another group (interviewees E1, E4, E8 and E10), the instability of the succession was responsible for the fact that, after the purchase, the filhos de santo did not reach an agreement as to who should govern. Thus, the trio indicated by the justice for such purpose - Ogã Valentim, Mametu Kitala and Mametu Ileci - had no political and religious command to keep the terreiro open. This functioned for a few more years, including initiations after the death of the leader, being closed due to lack of resources and members between the years of 1985 and 1988.

Finally, a third reading shows that the house remained open, but had undergone a process of subtraction of tiles, doors and bathroom fixtures, which was dilapidating the house until it was impossible to operate (entrevistados E6, E7, E9 e E12). We suspect that there may have been an incentive to steal material culture from the group owning the land as a way to accelerate the destruction of the site. Or, concomitantly, that the surrounding population, from the need to build their residences, has acted in this subtraction. In both cases the result was the same: removal of material from the site and its dilapidation. It is worth noting that the archaeological excavations undertaken did not identify, for example, doors or windows in the archaeological record, which is indicative that they no longer composed the house at the time of its closure and destruction. Not counting funds for the reforms, the house would have been abandoned to its new owner, which in this version did not stop its operation.

It is on these three strands that this article will focus on elucidating the process of ruining the site, ie how the terreiro was destroyed, abandoned or transferred. We will cross the data of the excavations to the collected memories and in this interlocution we will observe how a memory of the process of destruction was developed that indicates the permanence and the loss of the sacred content of the place.

2 Gomeia data collect

The research chose to listen as much as possible to "voices" of what Gomeia was like (physically) and how their religious experiences9 were at the site. Thus, we selected twelve people to be interviewed for this purpose prior to the start of site excavations. Initially, some former Gomeia members were still alive (five people in total, three women and two men), aged 65-85 on average. The choice was made by the fact that the chronological age had references to the operation of the terreiro, as well as to inquire with other leaders about the participation of the interviewees in the trajectory of the terreiro. These first interviewees are, at present, leaders and ogãs of candomblé terreiros. It is noteworthy that of these only two women and one man remains in locations that are identified as belonging to Angola tradition of Candomblé of Joãozinho da Gomeia.

Still in the sample, two other male leaders were interviewed and, although they identify themselves as Angola and Gomeia's descendants, their terreiros are characterized by the use of terms and rites of the Nagô tradition for the deities and by the fact that parties were still used for Pomba-gira and Exus Catiços da Umbanda. Their age ranges from 65 to 80 years.

We also interviewed the descendants of houses that identify themselves as belonging to the Gomeia tradition, two men being interviewed. The average ages are between 25 and 35 years old. These do not live in Rio de Janeiro, being a resident of Recife (PE) and another of the state of São Paulo. Due to the distance, these interviews were given through videoconference with the previous sending of a script of subjects. The footage was transcribed at a later time and, like the others, followed by release of use by means of an image and audio assignment term.

The survey also heard residents from around the land where Gomeia is located (in all, three people), two women and one man, all over 60 years of age and who have been living in the area since the 1960s. possessed contact with Joãozinho da Gomeia and with the terreiro in operation.

The interviews did not follow previous planning. They were asked to talk about their correlation with Gomeia and what they thought was important about the topic. When a subject, such as the building of the terrain, needed further study, the research intervened in the speech requesting a deepening of the subject. Each interview lasted, on average, 60 minutes and were transcribed afterwards. Previously, terms of consent for the interview were produced, these being signed authorizing their publication, but conditioning the non-delivery of the participant's name and the obligation to suppress identification of people and places that could indicate who the interviewee would be.

The interviewees specification follows in Table 1.

Archaeological research at Gomeia took place between the years 2015 and 2016 for a total of 30 days of excavation. These took place in two camps of fifteen days, with the participation of archaeologists, archeology students from UFRJ, students and post-graduate students of the same university, volunteers and afro-religious who volunteered to contribute to the action. The excavation had the logistical support of the Municipality of Duque de Caxias and the Secretary of Culture and Tourism of the same municipality. With this support we were able not only to clear the land for the excavations, but also to use machinery for the implementation of soil verification activities.

After excavation activities, the archaeological research in Gomeia obtained a material culture that can be classified into three main axes: objects of religious use (referring to Candomblé), secular uses (applied to non-religious daily practices) and mixed classified as such by the dubiety of being in religious contexts or day-to-day practices). This cleavage allowed the research to observe that a terreiro is also a living space, food and other elements that, although known at the present time, it was not known if they would leave vestiges in the archaeological record.

This material culture was classified into the following categories of constituent materials: metal objects, vitreous, organic, ceramic (earthenware ceramics and pottery), fabrics, plastics and rock. This allowed us to infer forms of use, rites, everyday practices, as well as to ascertain the historical depth of the use of some elements, such as plastic, for example, in candomblés.

From the obtained, it is clear that the religious practices of Candomblé left vestiges in the archaeological record. Our sample obtained 278 pieces of material identified as secular (42.7% of the sample), 177 for religious (27.2%), 166 considered as mixed (26%) and 30 pieces without identification (4.1%). If we add the mixed values to the religious we will get a value of 455 pieces that indicate religious practices (53.2% of the excavated). That is, by the sum accomplished, more than 50% of our excavated material culture represents practices, rites and religious objects in the archaeological record of the Historical Archaeological Site of terreiro da Gomeia.

3 Memories on Gomeia

Before we talk about the memories of the destruction, it is interesting to look at the nominations that terreiro da Gomeia possessed in Kimbundo dialect10 collected from oral sources: Bantuqueno Ngomenssa Kat'espero Gomeia or Atim Mossó Candengó Ingomessa Catispero. The first form can be translated - Manso: Aldeia; Bantuqueno: Old and correlated to the Bantos in Africa; Ngomenssa: drums; Kataspero: Joãozinho's home in Bahia and Gomeia refers to the location of the terreiro in Salvador. In other words, we could translate it as "Ancient Village of Bantu [of] Drums of Kataspero da Gomeia". The second name was not found translation, because this did not make sense in the attempts of translation by the ex-members of the place11.

The presence of two names, before being a problem related to the sources, is considered in this article as a data to be worked on by the concept of collective memory (Pollak, 1989; Halbwachs, 2006). For Halbwachs (2006) all memory has in its existence a psychological character: for something to be narrated and remembered, it becomes necessary that there be an individual and the occurrence of a fact to be described. Thus, what the author defends is individual memory (Halbwachs, 2006). However, for the author, even if apparently private, the memory refers to a group; the individual carries the memory in himself, but is always interacting in society, since "our memories remain collective and are remembered to us by others, even if they are events in which only we have been involved and objects that only we have seen" (Halbwachs, 2006, p. 30, our translation). In this way, we have the concept and correlation between collective memory and individual memory - one not existing without the other.

In the case of Gomeia it is interesting to reflect how the memories emerge from the contacts of the members and between the slopes of memory already described. Another factor to be considered was the finding that the memories of the destruction were "truncated" and tended to an appropriation and significance of the facts occurred. Thus, the episode of remembering or forgetting an event relates to the places that individuals occupy or no longer occupy as members of a particular group. Halbwachs (2006) relates memory to participation in a social group or an affective community. In this sense, the simple realization that there are two nominations to the site tells us how each person tended to develop a subjective process, but that is also social: remember or forget the name of the place or just name it terreiro da Gomeia.

In this sense, the memory of Gomeia's name can be understood as selective: it depends on the values of the individual, the historical moment and the interests of the social group, which always refer to conflicts of definition of identities (Pollak, 1989). An absence of oneness as to the naming of the place can be related to the establishment of several slopes of a collective memory where each group, or even individual, tended to develop in the context of filho de santo or at the moment of the crisis of succession and later ruin of the house. Remembering or omitting the name of Gomeia relates to processes that aim to "remember", in the sense of valuing the past of the place or of "forgetting" a leader and space seen as spurious. In another reading about memory, as Schwarzstein (2001) argues, "forgetting" can also relate to the suffering / pain that the accessed memories cause. Not "remembering" is a way of not accessing the trauma.

Thus, two distinct processes regarding the memories of the Gomeia can be observed: the forgetting of the place (and a consequent desacralization) and the maintenance of a positive memory, which is linked to the permanence of the sacred in that space. In this article this axiom interests us: in the present day the ground where the built rest of the Gomeia and the material culture present in its soil, coming from the human activities occurred there, are seen as sacred to the descendants of the terreiro or he has nothing but elements secular These poles allow us to debate the question of the presence or absence of sacredness in the remnants of the terreiro. Analyzing these memories do not throw us into the past, but to the present, for "the elaboration of memory occurs in the present and to respond to the demands of the present" (Meneses, 1992, p. 11 our translation). That is, to the actors who transited there, as children of a saint, does the place still have sacredness or does it no longer exist due to destruction?

For Gomeia, then, the memories will relate, first, to the category Time: the time the terreiro worked and the time in which it no longer works. However, separation is more an instrumental that aims to account for two moments of the trajectory of the place than, in fact, a separation of periods - be it the present or the past of religious quarrels. From our interviews, we observe that "remembering" or "forgetting" has developed a mechanism for building a time: in the present one means or resigns the past - for some the terreiro has no sacredness, but for others, yes. Thus, a question such as "who inherited the Gomeia" and "who acted in an erroneous manner that generated its end" provoked a deepening in this correlation between memory and archeology. Who, therefore, is currently responsible for what happened? For the oral sources consulted, being, observing or transiting in the remnants of the terreiro, at present, may mean "reviving" the trauma or memory of the trauma (Seligmann-Silva, 2005), but it also means updating the debate about the actions undertaken.

In the meantime, the Space category has become meaningful in the elaborations of memories about Gomeia:

The place transcends its objective reality and is interpreted as a set of meanings. In this sense, monuments, works of art, as well as cities are places because they are a set of meanings. On the other hand, when the place no longer stands as a set of meanings, most of the time because of the technology that transforms all places into homogeneous spaces into true 'landscape clones', places become non-places (Lencioni, 2009. p. 154, our translation).

For some voices, Gomeia remains a terreiro, a sacred one and one that owes obedience for this, are the material concretization of the memory of João Alves and his action. For other interviewees it does not mean anything else, because there is nothing sacred in that space, because everything has moved from there. It becomes a place without reference, without meaning, a place of passage and without fixation. This is how one interviewee E4 says: "There is nothing left. Everything was taken to [delete the name]. Why do you think there's something there? There's nothing, it's empty ground. " The interviewee concludes that: "Gomeia lives in another place and within me, but not there."

From this concept, we can reflect that if Time and Space represent and actualize a past period in Gomeia, the value given to the place is defined as a sense for the present and the future. To think of the relation between the two within the memories of Gomeia consists in some way of thinking about a reality that is established between what was and is the terreiro and what is defined as present identity - the factor that identifies voices in their positions nowadays.

We can analyze Gomeia's desacralization as follows: if nothing else in that space is sacred, its soil is not, structures are not, and, finally, even the memory is no longer sacred, because it has been erased with what we call of site blasting process. Out from the interviewed by the research, the interviewees E1, E4, E8 and E10 don’t believe the ground is sacred anymore, for there isn’t anything else that allows it to build the intermediation between material and spiritual level. If there are no more sacred objects, in the same way, nothing else is referred to the plan of the gods. The holy character was also extinguished or extinguished with the death of the leader.

According to the cosmology of Candomblé - Santos (1984) or Rocha (2000) - if all the rites of withdrawal and transfer of the sacred were realized and the new house that received this material gave continuity to Gomeia, she is alive in another place. Thus, according to this slope of memory, the progeny of João Alves was maintained. What remained on the ground reminds one of a certain past, but this one is actually living in another terreiro. Nothing in Duque de Caxias refers to the plan of the gods. If they no longer live there, the terrain has lost its sacred content. This strand is based on what we call an "Official Belief", that is, by the transfer rites and by the cosmology of Candomblé there is nothing else there that allows access to the sacred. This belief is as vivid as the rest, but tends to be based on formal religious aspects.