Difusão da informação em museus: tecnologia digital, interação e diálogo

Diego Ricca é Arquiteto, Designer de Interação e Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. É pesquisador do Programa de Pós-graduação em Design da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo, e membro do LabVisual da mesma universidade. Estuda projetos de museus, espaços educacionais, exposições e ambientes interativos, zoológicos, aquários, dentre outros, focados em interatividade, entretenimento e educação.

Clice Mazzilli é Arquiteta e Doutora em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, e Professora Associada do Departamento de Projeto da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo. É coordenadora do Programa de Pós-graduação em Design e do Laboratório de Programação Gráfica da mesma universidade. Estuda processos de criação, linguagem visual gráfica, linguagem visual ambiental, processos experimentais, espaços lúdicos e design editorial.

Como citar esse texto: RICCA, D. E. P.; MAZZILLI, C. T. S. Difusão da informação em museus: tecnologia digital, interação e diálogo. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 19, 2019. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus19/?sec=4&item=12&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 03 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 18 DE AGOSTO DE 2019

Resumo

Reflete-se a respeito da difusão da informação para o aprendizado em museus, com amparo no emprego de artefatos tecnológicos digitais interativos, por meio da proposição de categorias analíticas de tipologias de interação embasadas em pesquisa bibliográfica e de campo. Realiza-se, inicialmente, a triagem de referenciais teóricos pertinentes, a fim de entender diversas categorias do conceito de interação mostradas por alguns autores. Em seguida, efetiva-se uma proposta de categorização de tipologias de interações que consideram as modalidades de input e output inter-relacionadas: lineares, múltiplas e abertas. Totalizam-se nove categorias, às quais são associadas a uma série de estudos de caso selecionados e analisados conforme sua abertura, para elaborar e difundir a informação e o aprendizado por meio da interação usuário-máquina.

Palavras-chave: Interação Humano-Computador, Cibernética, Conversação, Aprendizado, Museus

1 Introdução

Com a proliferação do computador nas mais diversas escalas da vida humana, o design foi paulatinamente reconhecido como importante ferramenta, com vistas a humanizar e tornar amigáveis as interfaces com tais dispositivos ampliando as capacidades de atender às nossas necessidades. O design encarrega-se desta função e tem, na seara de conhecimento da Interação Humano-Computador (IHC), um meio de projetar tecnologia direcionada aos seus usuários. Especificamente, a disciplina IHC é dirigida ao projeto de programas e interfaces para maior interação e usabilidade da máquina. “Um bom sistema de computador, como um bom par de sapatos deve ser natural, confortável e servir sem que o usuário tenha consciência dele.” (FAULKNER, 1998, p. 7, tradução nossa). Nota-se que, crescentemente, as Ciências Humanas assumem papel bem relevante no sentido de entender aspectos subjetivos da consciência de pessoas quando em interação, clareando o entendimento no que tange a pontos perceptivos e cognitivos na relação com dispositivos tecnológicos. Na perspectiva de humanizar a tecnologia, este artigo tem um caráter transdisciplinar, com vistas a discutir distintas tipologias na interação usuário-máquina e possíveis consequências na construção da informação em espaços museológicos.

Considerar um artefato como interativo se refere à uma categorização de objetos conforme sua capacidade de se “comportar” ativados pela tecnologia interativa (MOGGRIDGE; ATKINSON, 2007). É dar a possibilidade deste de captar informações dos usuários, e de aspectos do espaço, de maneira a traduzi-los em informação digital, e, por conseguinte, em comunicação por meio da interação. Entende-se, neste experimento, que considerar interação como um diálogo pode fomentar caminhos para novas possibilidades do entendimento de como o design pode contribuir para constituir a informação por meio da interação com artefatos digitais. Com efeito, se encontra os espaços expositivos e museológicos como loci adequados para esta discussão, haja vista que o emprego de tecnologia nessas instituições é uma prática que cresce e se consolida, cada vez mais, no mundo, inclusivamente no Brasil.

O texto sob relatório é parte condensada de um dos capítulos da dissertação de mestrado que se defendeu, e tem por objetivo refletir a respeito da difusão da informação para o aprendizado em museus a partir do uso de artefatos tecnológicos digitais interativos por meio da proposição de categorias analíticas de tipologias de interação embasadas em pesquisa bibliográfica e de campo (RICCA, 2019). Para isso, realizou-se uma triagem de referenciais teóricos pertinentes, a fim de entender distintas categorias do conceito de interação expressas por alguns autores, para, na sequência, efetivar uma leitura interpretativa de estratégias projetuais em uma série de estudos de caso selecionados. Este experimento caracteriza-se, por conseguinte, como um estudo de reconhecimento, cujo método consistiu em visitas in situ a museus selecionados, tendo por complemento embasamentos bibliográficos e iconográficos – com o apoio de catálogos, fotos, livros, artigos e outros gêneros de publicações– pelos quais selecionou-se ao todo 13 artefatos concentrados em 11 instituições distintas1.

2 Mediação do conteúdo: interação em diálogo, referencial teórico

Na ação mediadora de conteúdos está o ato de comunicação, para transmitir uma mensagem, com base em um meio. Acredita-se que conhecer e aprofundar-se em aspectos teóricos da interação pode ser um caminho para aproximação de um maior entendimento de critérios projetuais de artefatos mediadores digitais em museus, a fim de fomentar o diálogo entre ser humano e máquina, e, por conseguinte, a construção da informação e o aprendizado. Vale destacar o fato de que, neste artigo, o termo “comunicação”não se resume à linguagem verbal, expandindo-se seu significado para compor também a própria interação como ação comunicativa.

Uma maneira efetiva de representar a interação humano-computador se baseia em uma estrutura denominada de feedback loop. Esta estrutura consiste em uma troca de informações em caminho cíclico que os dados fazem para ir do humano para o sistema – um computador, um aparelho celular ou um carro, por exemplo – e de volta para o humano. Com esta volta, a pessoa avalia se tal informação atingiu os objetivos que motivaram o estímulo inicial (ao interpretar o output do sistema), para, em seguida, direcionar a próxima ação com base nisso (DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009). Deste modo compreende-se que essa natureza cíclica da informação possibilita novas maneiras de construção e difusão da mesma. Este modelo da interação em loop para sistemas dinâmicos sugere à seguinte indagação: distintos graus de troca de interações levam a variados modos de trocas de informação? A fim de debater esse ponto, procede-se, no seguimento, a uma triagem de variadas categorias do conceito de interação em alguns autores selecionados2.

2.1 Tipologias da interação

A relação humano-máquina pode ocorrer de maneiras variadas, permitindo também sua classificação em múltiplas categorias que podem facilitar seu entendimento e leitura. Os autores Dubberly, Haque e Pangaro (2009) - em seu artigo What is interaction? Are there different types? - realizam, à luz da Cibernética de Segunda Ordem, de Gordon Pask (1976), uma sistematização da interação com suporte no que eles chamam de sistemas dinâmicos. Para esses especialistas, o fato de ser interativo não conforma a característica de um sistema em si, mas da natureza da troca de informações que é realizada entre elementos de um sistema. Estes classificam-se em três tipos essenciais: os 0) lineares; os 1) autorreguladores e os 2) de aprendizado. Os sistemas lineares (de 0 ordem) reagem de maneira padronizada aos estímulos a eles expressos.

Os sistemas autorreguladores (de 1a ordem) se caracterizam por dar retornos variados com amparo no tipo de input que lhes é concedido, ajustando seu comportamento e modificando suas respostas mediante o estímulo captado, de modo cíclico, sendo, entretanto, já previamente estabelecidas em sua programação. Já os sistemas dinâmicos de aprendizado (de 2a ordem) se caracterizam, não só, por ajustarem o comportamento desde os inputs, como também por aprenderem com as mudanças nos estímulos recebidos. O sistema, assim, aprende com o usuário, e vice-versa, à maneira de múltiplos ciclos, como uma espiral, na qual informações podem ser construídas de modo constante (DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009).

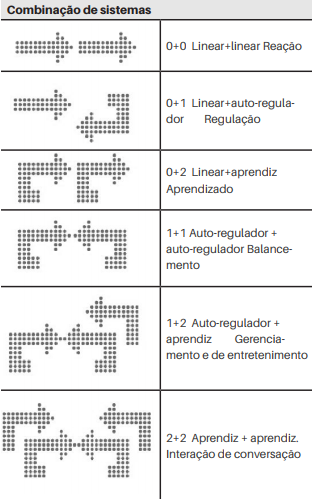

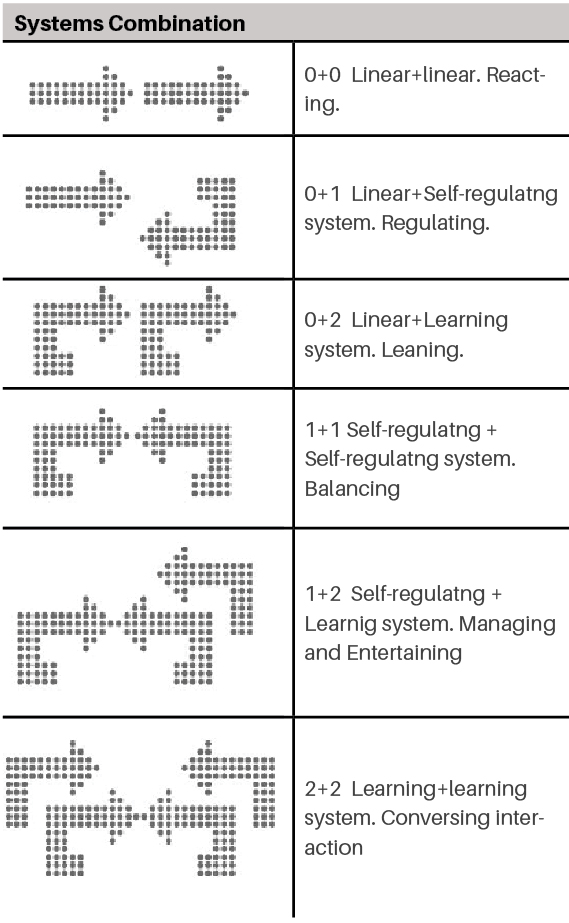

Quadro 1: Classificação de sistemas de interação. Fonte: Adaptação de Dubberly, Pangaro, Haque, 2009.

Na perspectiva dos autores, simplesmente apertar um botão (real ou virtual) não é interação, mas, sim, uma reação. Em um sistema reativo, o input e o output – estímulo e resposta – são fixos. De outra parte, quando este é caracterizado como interativo, os elementos de estímulo e resposta se retroalimentam, de modo a produzir um sistema dinâmico, e, portanto, progressivamente mais interessante para o usuário (DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009). Partindo, assim, da combinação de dois dos três tipos de sistemas anteriormente destacados, os autores elaboraram seis variados modelos de interação, apresentados no Quadro 1.

Na combinação de sistemas 0+0, de reação, o input, é causado por meio de um estímulo em um dispositivo – cutucar, rodar, sinalizar, empurrar. Segundo Gordon Pask (1976), tal ação enseja uma reação predeterminada e, muitas vezes, limitada. Com base nesta descrição, é possível perceber que muitos dos artefatos mediadores de conteúdo em museus se encaixam nesta categoria. A combinação de sistemas 0+2, de aprendizado denota uma tipologia de interação que engloba muitas das interações humano-computador. Nelas, um sistema aprendiz (o humano) interage com um processo de input linear. O sistema responde, e o humano se adapta àquele output. O ser humano aprende com o sistema; este, contudo, não aprende com o humano. Conforme lecionam Dubberly et al. (2009), estas não se caracterizam por permitir uma conversação propriamente dita, já que a máquina não aprende com os inputs trazidos pelo usuário.

Na combinação de sistemas 1+2, de entretenimento, os autores destacam o exemplo de jogos eletrônicos, nos quais o sistema é pensado dentro de um progressivo aumento da dificuldade, de acordo com o desenvolvimento do jogador. Tal estratégia projetual ocorre por meio da introdução de surpresas e desafios, o que renova e reforça a interação, contribuindo para o engajamento por via do entretenimento (DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009). De efeito, nesta categoria, são aplicadas regras, recompensas e desafios, objetivando um aumento da dificuldade, com o qual o usuário realiza uma competição ou colaboração. Na interação 2+2, de conversação, há um processo cíclico de input e output, em que dois sistemas aprendizes conversam entre si (DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009). Permitir a conversação em uma interação de conteúdo e visitante em museus exige que haja, de fato, uma troca entre sistemas.

Para melhor entender e desenvolver a prática de projetos interativos, Ruairi Glynn, arquiteto, artista e media-designer, classifica-os em três tipos, com esteio em suas reações a estímulos (GLYNN, 2008). O primeiro tipo parte de uma reação automática, possuindo apenas dois estados, ligado e desligado. Esta tipologia de reação se caracteriza por ser independente de inputs externos. A segunda maneira se classifica como reativa, agindo de acordo com critérios anteriormente definidos. Em muitos casos, esta natureza de output é erroneamente caracterizada como interativa. A reação interativa, para ele, portanto, só pode ser considerada quando há uma autonomia do próprio sistema, com a possibilidade deste de, por variados meios, atingir os objetivos estabelecidos inicialmente na programação. De maneira análoga, o artista Jim Campbell (2000) caracteriza as interfaces interativas em duas modalidades. A primeira como interface discreta, citando o exemplo de um carpete, no qual se aciona uma imagem quando o visitante fecha o circuito ao pisar um botão. A pessoa ali não interage com o programa ou com a imagem, apenas com o botão, de modo que “[...] não há diálogo, apenas os estados de ligado e desligado.” (ALMEIDA, 2014, p. 131). A segunda classificação de Campbell caracteriza-se por interface contínua, a qual ocorre, por exemplo, quando em um carpete se dispõem de cem botões, e, ao se pisar separadamente cada um deles, umas cem respostas são geradas e refletidas em um monitor, o qual é estimulado com base no mapeamento da posição do ser humano (CAMPBELL, 2000).

Ao se reportar a mídias interativas com esteio no viés da comunicação, Jens Frederik Jensen (2008, p. 129, our translation) define interação como “[...] uma medida da habilidade potencial de uma mídia de permitir que o usuário exerça uma influência no conteúdo e/ou a forma da comunicação mediada”. Com encosto nesta definição, ele descreve quatro subconceitos de interação: Interação de transmissão, consistente em uma mídia de “mão única”, como uma TV que não permite ao usuário fazer solicitações outras além de trocar o canal; interação de consulta, na qual há uma possibilidade de permitir que o usuário escolha uma informação pré-produzida, como um website na Internet; interação de registro, em que há uma automatização das respostas dadas aos usuários, por meio de suas necessidades e ações (ele dá como exemplo métodos de sistemas que sentem automaticamente estímulos do ambiente e se adaptam, como sistemas de segurança, home-shopping, luz automática da interface do smartphone etc.); interação de conversa, onde existe um compartilhamento de “mão dupla”, como o exemplo de uma troca de e-mail entre duas pessoas, em uma interação humano-humano por meio da Internet (JENSEN, 2008). Considerando as taxonomias já mostradas, foi elaborado um quadro em que são reproduzidas, resumidamente, categorias delineadas em cada autor.

Quadro 2: Definição de interação em distintos autores. Fonte: Elaborado pelos autores com base na literatura referenciada (2018).

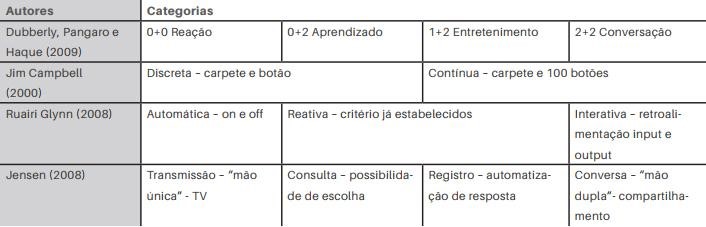

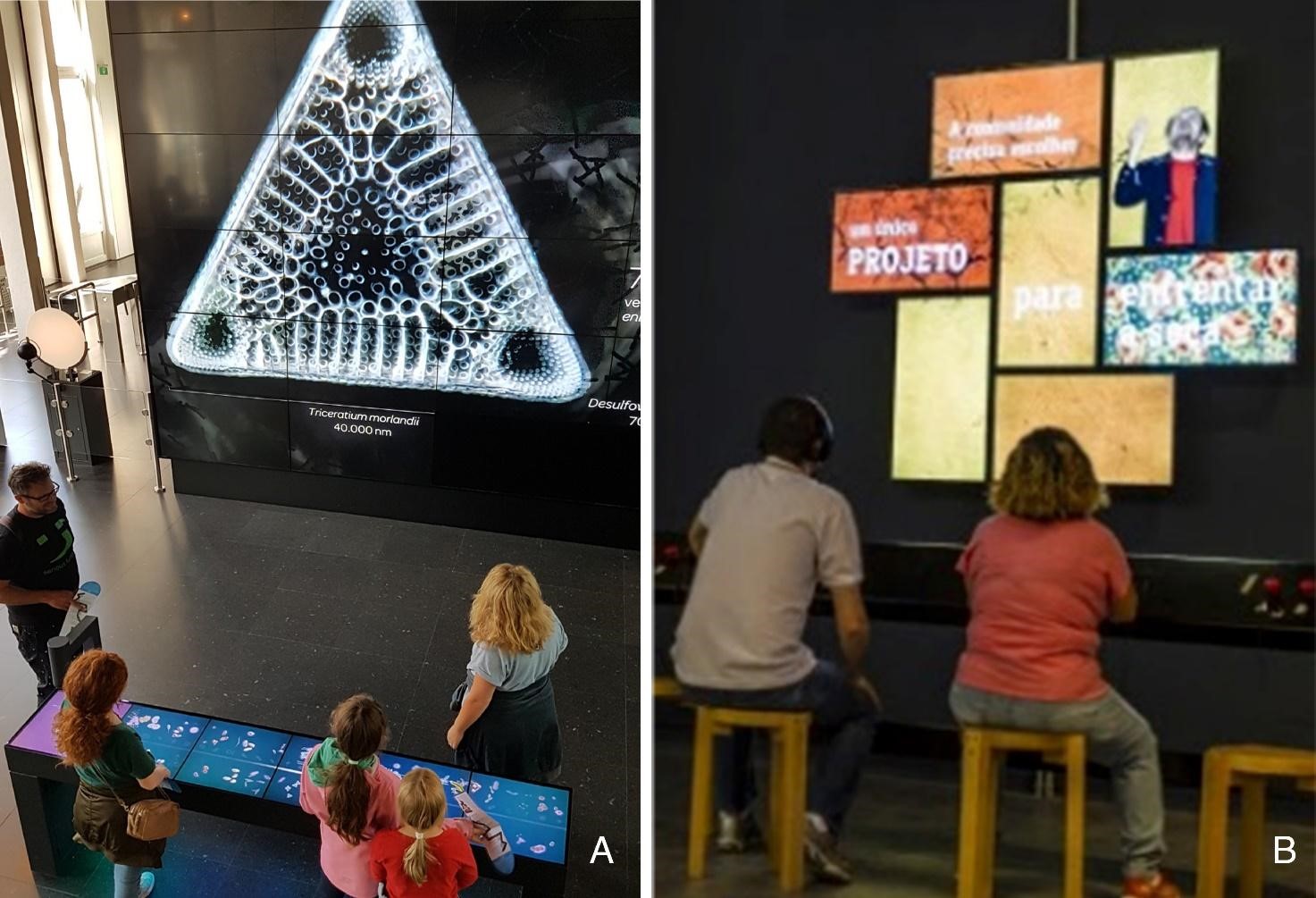

3 Estratégias projetuais: diagramas de estímulo e resposta

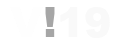

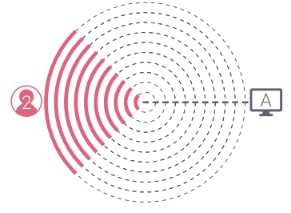

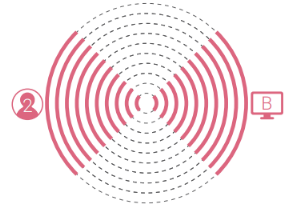

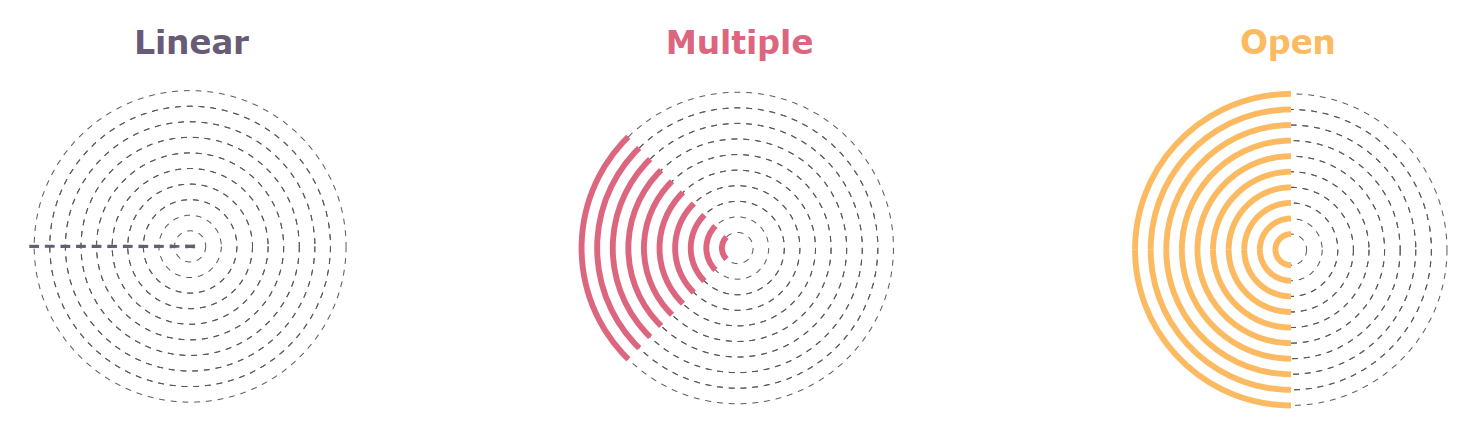

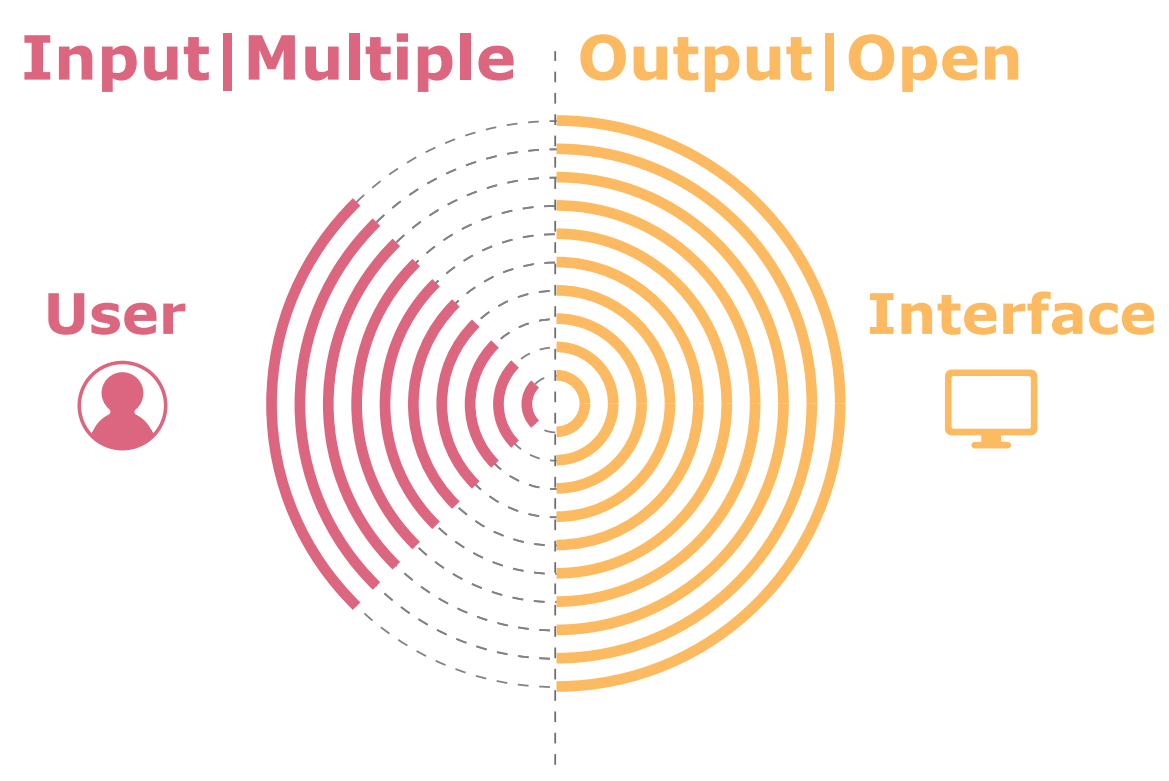

Ao analisar o quadro do item anterior, é possível perceber que há um padrão de categorizações de outputs na interação humano-computador, e, neste artigo, suscita-se a proposta de analisar estas múltiplas definições com base em três tipologias: 1) linear – quando há input ou output automatizado, com retorno padronizado, no qual o participante tem poucas, ou apenas uma, possibilidade de estímulo; 2) múltipla – em um output também padronizado, entretanto, com variáveis possíveis, a depender do estímulo provocado, o que possibilita uma multiplicidade de inputs por parte do usuário, permitindo maior desenvoltura de um sistema; ou 3) aberta – quando se possibilita uma retroalimentação entre inputs e outputs, como uma conversa, um diálogo entre humano e sistema, sendo este não padronizado, cíclico e cambiante, aproximando-se, em alguns casos, de uma aleatoriedade, abrindo-se para o indeterminado. As três representações adotadas são expostas graficamente na imagem abaixo.

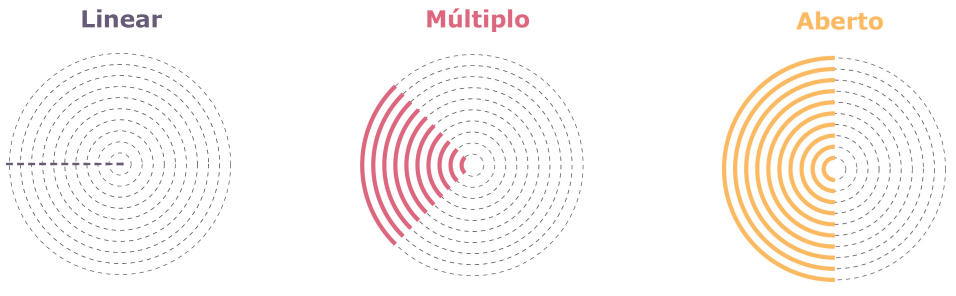

Na busca de tratar de maneira equivalente a leitura das ações, tanto sob a perspectiva da máquina, quanto em relação a do ser humano, foi proposta uma maneira de classificar os inputs e outputs dentro destas duas naturezas na interação com artefatos tecnológicos digitais. Deste modo, é realizada uma classificação que busca entender as tipologias das possibilidades das ações do usuário, bem como das modalidades de resposta da máquina dentro de uma mesma estrutura de interpretação, a fim de entender as distintas possibilidades de construção e difusão da informação em tais categorias.

Ao pensar nesta classificação aplicada a artefatos tecnológicos digitais mediadores de conteúdo, é proposta uma maneira de leitura, que busca, visual e conceitualmente, facilitar no entendimento de suas propostas de interação, tendo o visitante como elemento tão estruturante como o próprio sistema. Mostram-se na figura abaixo o diagrama-padrão e as descrições equivalentes para cada tipologia encontrada. Do lado esquerdo, em magenta, está a representação do input, vindo do usuário, que no caso é do tipo múltiplo. Do lado direito, a representação do output de tipo aberto, representado por um semicírculo. Tal modo de ver se aplica tanto para os inputs, vindos do visitante, como para os outputs, procedentes da máquina. Com suporte neste aspecto, procurou-se mapear essas possibilidades aplicadas a casos reais, os quais foram visitados considerando-se o recorte proposto na pesquisa, ou seja, a relação entre visitante e artefato digital mediador de conteúdo em museus. Há, portanto, três naturezas de categorias que, quando combinadas entre si, formam nove tipologias de características distintas de troca de informação pela interação, como pode ser visto na figura 3.

3.1 Estímulo linear – Resposta linear (1-A)

Esta tipologia 1-A de classificação considera um estímulo de característica linear – lado esquerdo do círculo - seguido de uma resposta também linear - lado direito do círculo. Tal relação com o artefato digital se caracteriza por ser de simples entendimento e dispor de possibilidades limitadas unilaterais de troca de informação. Um exemplo desta natureza de artefato pode ser largamente encontrado em muitos museus no formato de audioguias, nos quais o visitante pressiona um código predeterminado e recebe uma resposta também pré-cadastrada.

Exemplos dessa tipologia foram visitados no Centro de Ciências Ottobock, em Berlim. Estas tratam dos aspectos motores do corpo humano, e utilizam projeção associada a sensores simples. A interação 1) More than skin deep é ativada por partes do corpo humano, iniciando projeções animadas sobre algumas mesas, pelas quais o usuário poderá entender mais sobre os tendões e músculos. Já a 2) - Test your balance! - é uma interface na qual o visitante caminha em linha reta sobre um trecho onde são projetadas imagens de variadas alturas, em três níveis de dificuldade, mostrando como um estímulo virtual pode produzir um desequilíbrio no cérebro e, por conseguinte, nas demais partes do corpo. Esta, em específico, abre espaço para que possibilidades de interações sociais e lúdicas possam ocorrer, mesmo se tratando de uma tipologia linear-linear.

Fig. 5: Imagens A: Interação 1) More than skin deep. Fonte: O autor. Imagem B: Interação 2) Test your balance! Disponível em: <https://www.nationalmuseum.ch/e/>. Acesso em: ago. 2019.

3.2 Estímulo linear – Resposta múltipla (1-B)

Esta tipologia de interação 1-B, assim como a 1-A, permite apenas estímulos lineares, ou seja, de característica singular, aceitando, entretanto, uma certa variação nas possibilidades de resposta. Um exemplo didático é o ato de jogar um dado virtual, por exemplo, no qual o humano tem apenas uma atitude linear de jogá-lo, e pela qual se abrem, normalmente, seis possibilidades de resposta, caracterizando a modalidade de output como múltipla. Tal tipologia de artefato foi encontrada na interface 3) Waltz-Dice-Game, no museu Haus der Musik, em Viena, na qual é possível compor uma música em conjunto com outros visitantes com base no jogo simultâneo de quatro dados virtuais. A composição se dá com as múltiplas combinações possíveis e pode ser compartilhada virtualmente com os usuários.

Fig. 7: Waltz-Dice-Game. Disponível em: <http://bit.ly/2ZemXGk>. Acesso em: 01 ago. 2019.

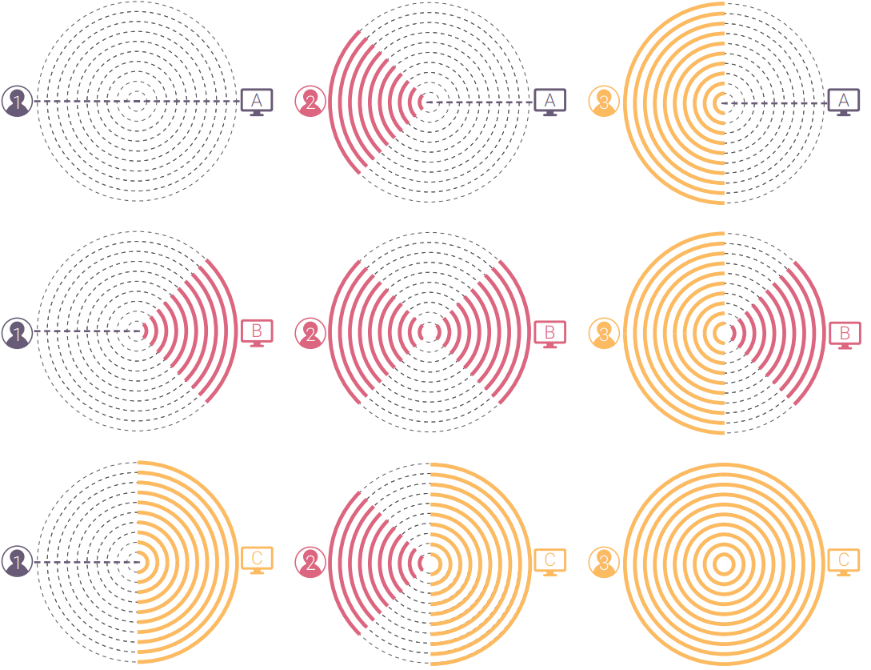

3.3 Estímulo linear – Resposta aberta (1-C)

No contexto 1-C de possibilidades lineares, os artefatos que permitem uma elaboração de respostas abertas são aqueles nos quais o estímulo do visitante, mesmo que limitado, pode produzir respostas e informações constantemente alteráveis. Exemplo fictício de interface desta natureza seria uma instalação em que, por um sensor de presença, fosse expressa alguma manifestação audiovisual de natureza aleatória. A presença seria categorizada como um input linear, pois que não pode ser alterável; já a mídia, por ser aleatória e sem padrões, poderia ser categorizada como aberta. Acontece que esta é uma tipologia que não foi encontrada nos casos pesquisados, quando se tratando de exemplos que se propõem a de conteúdo, principalmente em sendo do sentido de construção da informação, e não da interação em si mesma (mesmo levando em consideração o contexto, não foi possível ter uma compreensão da frase por parte deste corretor. A dificuldade no entendimento tornou inviável a proposição de alterações, sugere-se a revisão da sentença). Supõe-se que, em razão de sua natureza aberta de resposta vir de um estímulo linear, esta tem características mais raras de serem reproduzidas.

3.4 Estímulo múltiplo – Resposta linear (2-A)

Cuidando agora do contexto de múltiplas possibilidades de estímulo, esta categoria 2-A conta com um tipo linear de resposta. Tal modalidade de relação com o artefato se caracteriza por denotar diversas possibilidades de configuração de interação, sendo que estas ensejam retornos padronizados e constantes. Por permitir mais de um modo de ação, tais naturezas de artefatos tendem a possuir bastante potencial no sentido de engajamento, pois dão azo a múltiplas possibilidades, já que proporcionam ao visitante boa autonomia, de modo a decidir o que quer e o que não quer aprender daquela informação. Observou-se que, por tal multiplicidade do estímulo, e por uma padronização de respostas a dependerem do usuário, os designers tendem a gerar conteúdos demasiadamente extensos, exigindo tempo e paciência para acessar toda a informação disponibilizada, sendo, muitas vezes, não acessadas em sua totalidade. Isso ocorreu, como tal, nos exemplos 4) Body Scan e 5) Narrativas por pingentes. Notou-se que, nestes casos, o visitante se encanta com a possibilidade de interação, mas logo se cansa da linearidade da resposta, passando rapidamente para a próxima obra, ou instalação do museu, limitando a construção da informação por não permitir uma troca efetiva com o usuário.

O exemplo 4) se encontra no Museu Micropia, em Amsterdam, destinado a mostrar a vida dos micróbios. Tal interface consiste em uma grande tela com um sensor que detecta poses do corpo do visitante. O sistema utiliza tais posições como controle, podendo estas ser livremente movidas em direção a partes do corpo humano virtual detectado, como se fosse um scanner. Ao selecionar uma parte específica, é mostrado o largo conteúdo relativo às bactérias daquela parte escolhida. Já o exemplo 5) se encontra no setor dos Vikings do Moesgård Museum, destinado a etnografia e situado na cidade de Aarhus, na Dinamarca. Consiste em pingentes, dentro dos quais há um chip de radiofrequência (RFID). O visitante, ao adentrar a sala, escolhe um, ou mais, pingentes relativos ao personagem que mais interessar a ele (também aqui sugere-se o uso da construção direta para facilitar a leitura), sendo possível ouvir versões distintas de narrativas e explicações a respeito das esculturas ou objetos históricos, apenas colocando o pingente desejado sobre os receptores.

Fig. 10: Imagem A: Interação 4) Body Scan. Disponível em: <http://bit.ly/2P3Oo1U>. Acesso em: 01 ago. 2019. Imagem B: Interação 5) Narrativas por pingentes. Fonte: Autores, 2018.

3.5 Estímulo múltiplo – Resposta Múltipla (2-B)

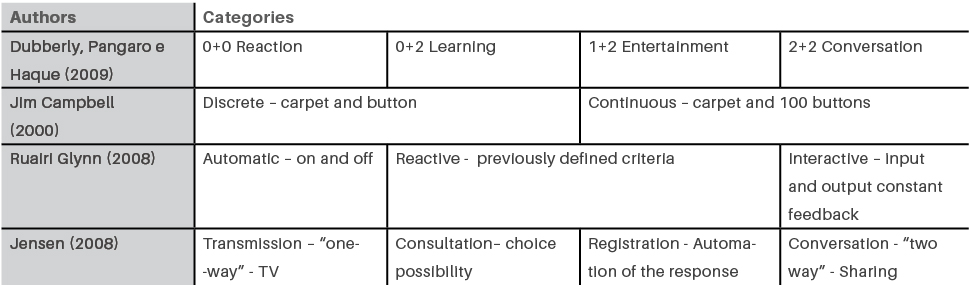

Esta é a tipologia mais vezes encontrada nos espaços visitados, a qual permite que o visitante tenha certa multiplicidade de possibilidades de ação, ensejando respostas também variadas, sem, entretanto, serem totalmente abertas. Notou-se que tal natureza de interação provoca, por vezes, estímulos considerados enriquecedores para os visitantes nos artefatos, pois permite uma difusão maior de informações a partir da troca. O caso 6) Microbe Wall consiste em um conjunto de 30 máquinas de carimbos situados em cada uma das estações expositivas do Museu Micropia. Quando em frente a uma explicação a respeito de um microrganismo específico, o participante pode carimbá-lo em seu mapa de visita, o qual, ao fim, pode ser lido em uma mesa digital que projeta animações com os organismos colecionados. O caso 7) Jogo das Secas, situado no Museu Cais do Sertão, no Recife, consiste em uma interação na qual o cantor Tom Zé narra um jogo interativo de desafios estratégicos para acabar com o problema da seca. O sistema do jogo se baseia na competição entre participantes. O ganhador é aquele que efetuar mais soluções que não apenas resolvam o problema das secas momentaneamente, mas a longo prazo.

Fig. 12: Imagem A: Interação 6) Microbe Wall. Disponível em: <https://artcom.de/en/project/micropia/>. Acesso em: 01 dez. 2018. Imagem B: Interação 5) Jogo das Secas. Disponível em: <https://janelasabertas.com/2014/07/18/museu-cais-sertao/>. Acesso em: 01 dez. 2018.

Nos exemplos escolhidos, foi possível notar que tal multiplicidade de input e output é também geradora de interações sociais, diálogos e momentos de ludicidade percebidos nestes e em outros casos visitados. Com isso, são produzidos aspectos relevantes no sentido de transcendência do limite da multiplicidade identificada, possibilitando distintas maneiras de construção e difusão da informação didática a partir de distintas estratégias projetuais desses artefatos.

3.6 Estímulo múltiplo - Resposta aberta (2-C)

Esta classificação 2-C se caracteriza por uma multiplicidade de estímulos (inputs), motivando possibilidades variáveis de resposta (outputs). Ao analisar a aplicação desta tipologia proposta, foi notado que, assim como as categorias 1-B e 2-C, as formas de inputs são mais limitadas do que as de output, sendo estas as que menos tiveram casos que se identificaram com tal modo de interação. A categoria 2-C se alinhou com apenas um dos casos do estudo de reconhecimento, sendo este o caso 8) The Portrait Machine, situado no Aros Museum de arte contemporânea, o qual possibilita que o visitante produza uma posição corporal específica dentro de uma numeração limitada, e, desde esta imagem captada, gerar um output de colagens com partes distintas de várias obras do acervo. Tal característica de retorno é aberta, pois nunca se repete, é sempre variável, a depender do visitante e da sua interação com o outro. Na imagem, é mostrado o produto gerado da interação do pesquisador com esta interface.

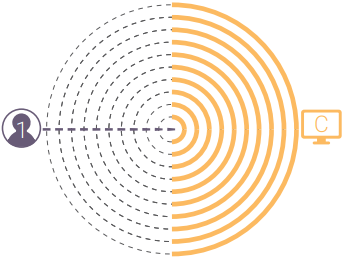

3.7 Estímulo aberto – resposta linear (3-A)

No contexto de modalidades de estímulo abertas, a categoria 3-A é definida como uma tipologia de artefato interativo, no qual o visitante tem uma grande liberdade dentro do sistema, a qual ele responde suas informações de modo padronizado. O caso que se encaixa nesta descrição é o 9) Exploded View, situado no Swiss National Museum. Nele, o visitante, por meio da movimentação de uma esfera de concreto, pode mover-se por diversos monumentos ao redor do mundo, sendo estes construídos por cloud points, criada por uma triangulação de inúmeras fotos turísticas de distintos ângulos destes locais. O visitante tem liberdade total para mover-se, entretanto, a interface em si não se altera em nada com o movimento deste, apenas mostra ângulos variados dos monumentos em nuvens de pontos.

3.8 Estímulo aberto – resposta múltipla (3-B)

Na categoria 3-B, o lado esquerdo demonstra que as possibilidades de entrada de informações são abertas, e estas produzem respostas múltiplas do sistema, conforme representado. Tal tipologia de interação permite que o visitante tenha liberdade na maneira de alimentar o sistema, e este responde com possibilidades múltiplas, porém limitadas. Um caso que exprime esta tipologia é o 10) Sketch your idea! do Cooper Hewitt design Museum, em Nova York. Nele o visitante pode fazer com a caneta o formato que quiser dentro do sistema de uma mesa digital. Esta interpreta dentro das limitações de acervo e de opções possíveis da modelagem, a qual se transforma em distintas tipologias de artefatos de design: mesa, abajur, cadeira etc.

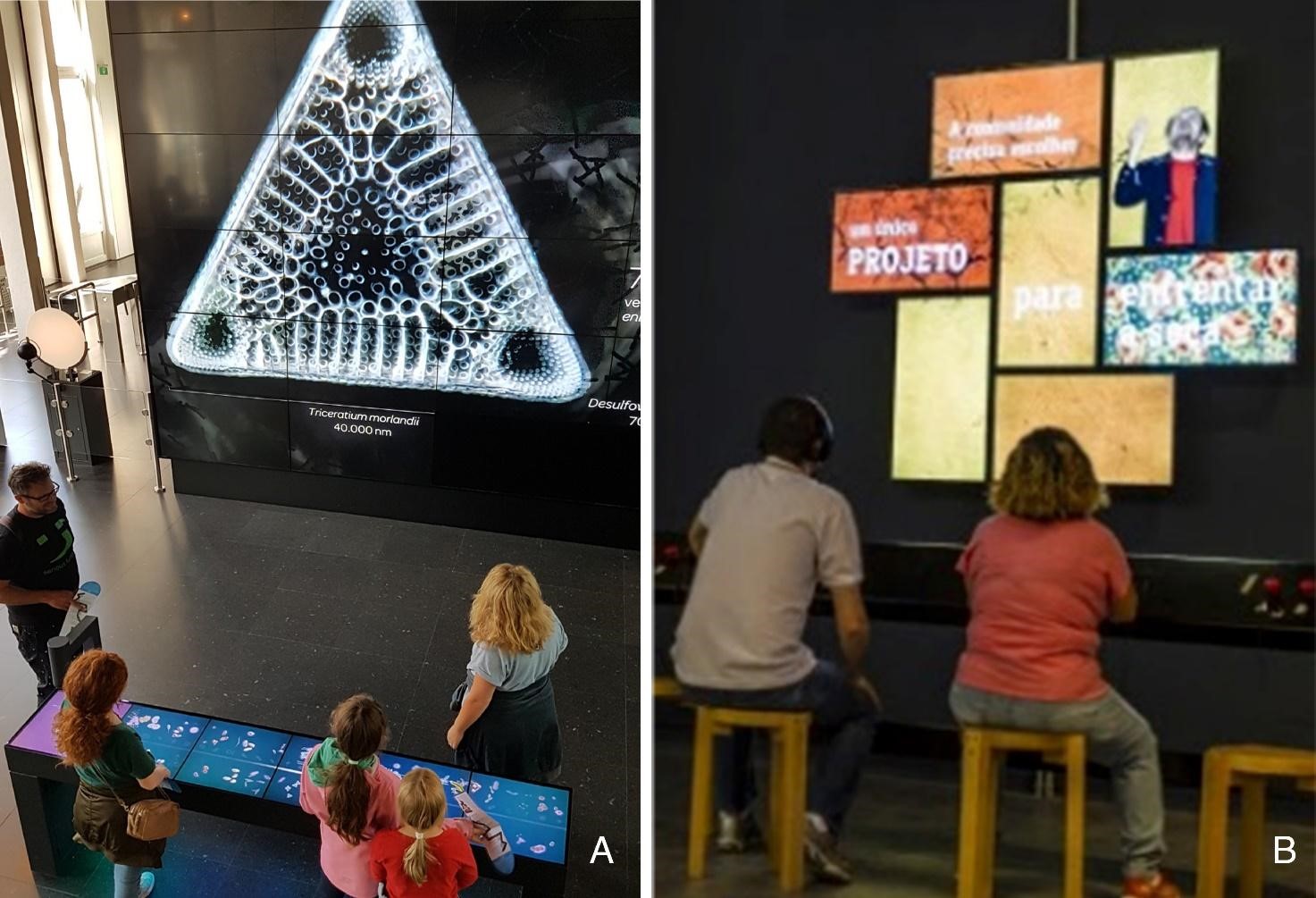

Outros casos que se encaixam nesta categoria são algumas interfaces que utilizam Inteligência Artificial (IA) para a interpretação dos estímulos do visitante, como as parcerias entre a IBM e o Museu do Amanhã, criando o sistema 11) IRIS+, e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo, instituindo o projeto 12) A Voz da Arte. Tais parcerias aplicaram a IA do Watson nestes espaços culturais, demonstrando um sistema de machine learning emissor de respostas que, por serem originadas de questionamentos abertos vindos do usuário, podem até ser interpretadas pelos visitantes como uma conversação fluida, um diálogo em tempo real com a máquina, sendo, na verdade, baseado em respostas predeterminadas cadastradas por seres humanos.

Fig. 18: Imagem A: Interação 10) Sketch your idea! FONTE: CHAN, COPE, 2015. Imagem B: Interação 11) IRIS+. Disponível em: <https://casacor.abril.com.br/noticias/iris-a-nova-inteligencia-artificial-do-museu-do-amanha/>. Acesso em: ago. 2019. Imagem C: Interação 12) A Voz da Arte. Fonte: Autores, 2018.

3.9 Estímulo aberto – resposta aberta (3-C)

Observou-se nos casos analisados, que permitir uma liberdade de estímulos e respostas dentro de possibilidades abertas dá maneiras diferenciadas de o visitante se relacionar, seja com a própria informação disposta, como também com a interface, com o espaço do museu e outros visitantes, dando espaço para que o inesperado ocorra, que a surpresa possa se manifestar, e que novas formas de construção da informação aconteçam. Sugere-se que tais modalidades de abertura, quando representadas de ambos os lados do círculo da figura, motivam mais possibilidades lúdicas de interações relacionais do visitante com aspectos exteriores à interface em si, tornando, muitas vezes, a interação mais rica e social, e a difusão da informação, na maioria dos casos, mais efetiva. Por estes motivos, considera-se que esta tipologia de categorização seja a que mais se aproxima das definições de interação dialógica citadas por alguns autores no referencial teórico (CAMPBELL, 2000; CARNEIRO, 2014; DUBBERLY; PANGARO; HAQUE, 2009; GLYNN, 2008).

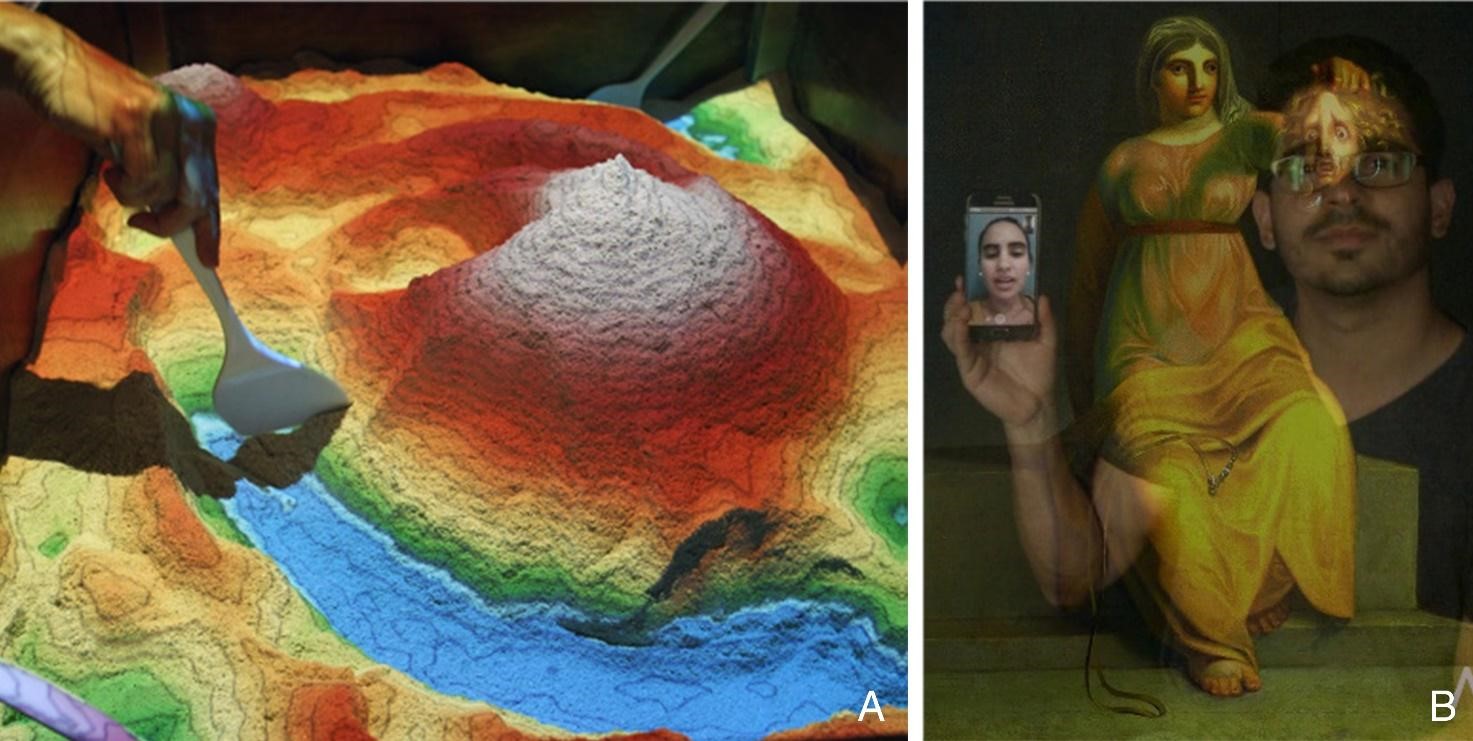

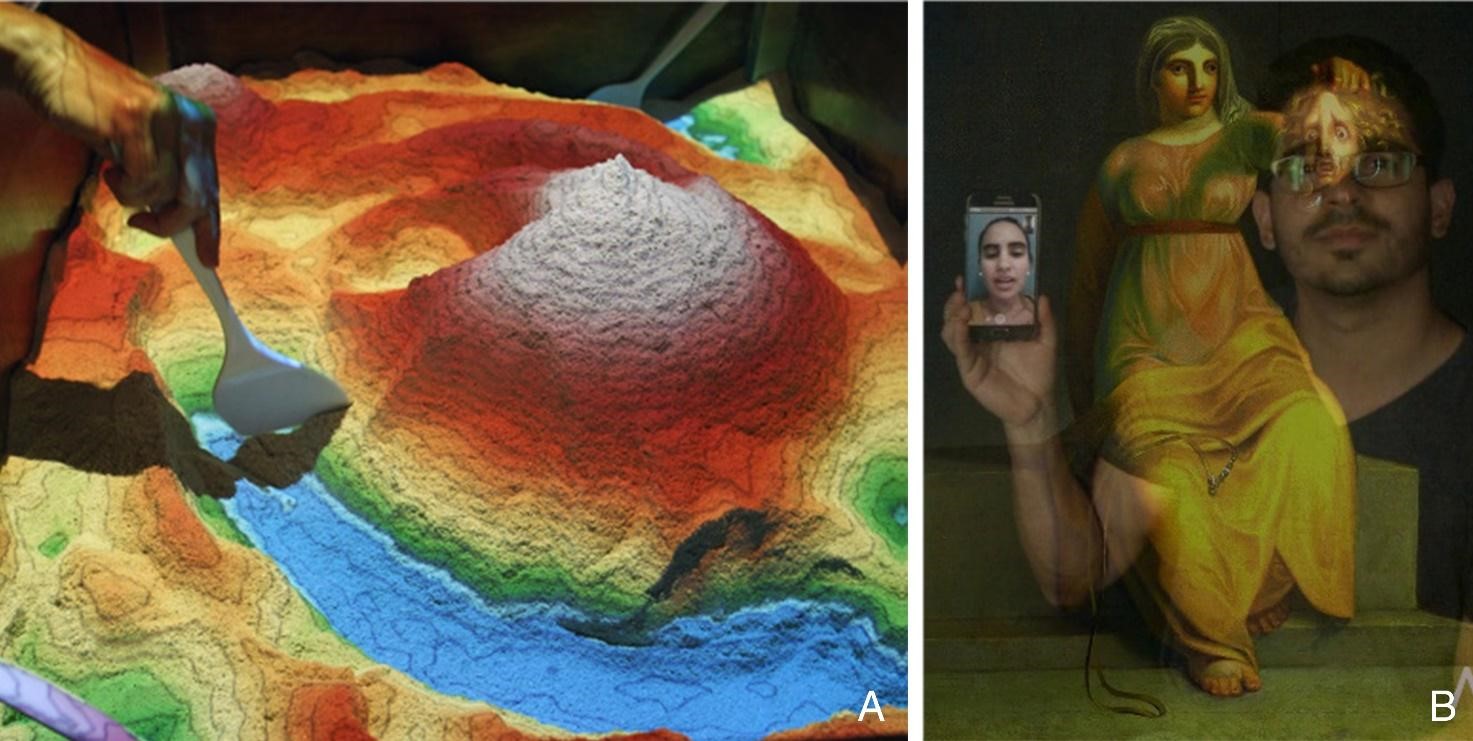

Os casos escolhidos para exemplificar tal categoria são: 13) Relevos da Terra em 3D, do Museu Catavento, em São Paulo; e a 14) The Recording Booth, no ARoS Museum. O caso 13) consiste em uma caixa de areia na qual é projetada – por via de realidade aumentada (RA) – uma imagem de relevos e curvas de nível desde a altura em que se encontram os montes e declives criados pelo próprio visitante, com a manipulação da areia. O projetor é conectado a um computador integrado a um kinect, o qual percebe as distâncias e modifica em tempo real a imagem projetada a fim de ensinar topografia. Já o 14) consiste em uma cabine de gravação na qual há uma tela que mostra as instruções. Ali, dois ou mais visitantes são convidados a responder a perguntas sobre uma obra do acervo por eles selecionada, as quais não são voltadas a testar conhecimento, mas questionamentos estimulantes que fomentam diálogos e interações sociais. O material gravado transforma-se em um vídeo e em um GIF enviado por e-mail para uso e compartilhamento, permanecendo em constante reprodução em telas do museu, tornando o visitante efetivamente parte do acervo. Estes possibilitam ao visitante interagir abertamente com a interface, a qual responde também de modo sempre novo.

Fig 20: Imagem A: Interação 13) Relevos da Terra em 3D. Disponível em: <http://bit.ly/31XnScb>. Acesso em: 01 ago. 2019. Imagem B: Interação com usuária a distância no 14) The Recording Booth. Fonte: Autores, 2018.

4 Conclusão

Foram indicadas neste texto algumas tipologias de interação e possíveis consequências do uso destas para a construção de conhecimento e para a experiência de visitação. A modalidade de classificação realizada arrimou-se na citação de exemplos práticos, a fim de refletir as variadas possibilidades de uso de tecnologia digital em mediadores de conteúdo em espaços expositivos. Com os casos elencados e as análises propostas, pôde-se inferir que diversificadas estratégias projetuais podem se relacionar diretamente com intenções subjetivas direcionadas aos visitantes, permitindo que novos usuários se achem incentivados a engajar-se nestas experiências, o que permite uma ampliação das camadas sociais de atuação das instituições museológicas, bem como as possibilidades inovadoras de transmissão de informação.

Notou-se que os autores e especialistas citados se reportam de maneira semelhante a respeito destas tipologias de interação. Ao utilizarem nomenclaturas diversificadas, muitos buscam definir uma mesma essência estrutural nos ambientes de fato interativos. Em suma, o que estes autores transportam é uma divisão com base na maneira como o tipo de rotina lógica de estímulo (input) e resposta (output) é implementado. Para trabalhos futuros, interessa notar como esta demanda por uma relação mais significativa com a máquina se repete em diversos autores, aprofundando nos pontos em que estas se distinguem. Percebe-se que a interatividade no nível dialógico (3-C - aberto-aberto) é um desafio a ser alcançado, e que poucos casos se exprimem como bem-sucedidos neste sentido.

Com os eventos analisados, é válida a suposição de que, para a instituição museológica, optar por permitir a interação é dar ao visitante a possibilidade de alterar os estímulos e as respostas do sistema, ensejando variadas formas de construção e difusão do conteúdo, de modo que o projetista não deve limitar as possibilidades, mas ampliá-las, explorando positivamente a existência de regras, limitações e relações lúdicas, sociais e inesperadas. Segundo Glanville (2001), a interação em si lida com o indeterminado, é um produto de uma relação circular, não causal e sem controle. Gordon Pask discute a importância da interação e a necessidade da novidade, para que o homem se engaje em situações com o seu ambiente: “o homem está inclinado a procurar novidade em seu ambiente, e, tendo achado uma situação nova, a aprender a controlá-la.” (1971, p. 76, our translation). Com base nestas e nas outras reflexões apontadas neste artigo é possível supor que uma ação simples, em sequência linear, pode limitar-se e não abrir espaço para a novidade, ou seja, para o elemento surpresa dentro da interação, restringindo a construção de informação ao limitá-la em possibilidades.

Referencias

CAMPBELL, J. Delusions of dialogue: control and choice in interactive art. Leonardo, v. 33, n. 2, p. 133-136, 2000.

CARNEIRO, G. P. Arquitetura interativa: contextos, fundamentos e design. Tese (Doutorado em Design e Arquitetura) - Faculdade de Arquitetura e urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014.

CHAN, S.; COPE, A. Strategies against Architecture: Interactive Media and Transformative Technology at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The Museum Journal, v. 58, n. 3, p. 352-368, 2015.

DE ALMEIDA, M. A. Ambientes interativos: a relação entre jogos e design para a interação. Tese (Doutorado) - Núcleo de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2014.

DE ALMEIDA, M. A. A teoria da ludificação e os ambientes responsivos. Blucher Design Proceedings, v. 3, n. 1, p. 838-843, 2016.

DUBBERLY, H.; PANGARO, P.; HAQUE, U. What is interaction?: are there different types? Interactions, v. 16, n. 1, p. 69-75, 2009.

FAULKNER, C. The essence of human-computer interaction. Londres: Prentice Hall, 1998. 0137519753.

GLANVILLE, R. And he was magic. Kybernetes, v. 30, n. 5/6, p. 652-673, 2001.

GLYNN, R. Conversational environments revisited. In: MEETING OF CYBERNETICS & SYSTEMS RESEARCH, 2008, GRaz-Áustria. Proceedings...

HAQUE, U. The architectural relevance of Gordon Pask. Architectural Design, v. 77, n. 4, p. 54-61, 2007.

JENSEN, J. F. The concept of interactivity--revisited: four new typologies for a new media landscape. ACM, p. 129-132, 2008.

MOGGRIDGE, B.; ATKINSON, B. Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

PASK, G. A comment, a case history and a plan. In: REICHARDT, J. (Ed.). Cybernetics, Art and Ideas. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphics Society, 1971. p. 76-99.

PASK, G. Conversation theory: Applications in education and epistemology. Amsterdã/Nova Iorque: Elsevier, 1976. 044441424X.

RICCA, D. E. P. Artefatos tecnológicos digitais interativos: estratégias projetuais para fomento da mediação de conteúdo em museus. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-graduação em Design, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo - FAU USP, 2019.

RICCA, D. E. P.; MAZZILLI, C. D. T. S. Content mediation and digital technology in museums: design strategies to enrich the visitor’s experience. In: SIGRADI, 2018, São Carlos-SP. Proceedings...

1 1) More than skin deep e 2) Test your balance! no Centro de Ciências Ottobock em Berlim; 3) Waltz-Dice-Game, no museu Haus der Musik, em Viena; 4) Body Scane 6) Microbe Wall no Museu Micropia, em Amsterdam; 5) Narrativas por pingentes no Moesgård Museum, em Aarhus, na Dinamarca; 7) Jogo das Secas, no Museu Cais do Sertão, em Recife; 8) The Portrait Machine e 14) The Recording Booth no Aros Museum, em Aarhus, na Dinamarca; 9) Exploded View no Swiss National Museum; 10) Sketch your idea! no Cooper Hewitt design Museum, em Nova York; 11) IRIS+, parceria entre a IBM e o Museu do Amanhã, no Rio de Janeiro; 12) A Voz da Arte, parceria entre a IBM e a Pinacoteca de São Paulo e 13) Relevos da Terra em 3D no Museu Catavento, em São Paulo.

2 Vale ressaltar que esta compilação de autores e de seus respectivos conceitos relativos às distintas formas de interação também foram abordados pelo autor no artigo "Content mediation and digital technology in museums: design strategies to enrich the visitor’s experience" publicado no SIGRADI 2018 (RICCA; MAZZILLI, 2018).

Information diffusion in museums: digital technology, interaction and dialogue

Diego Ricca is an Architect, Interaction Designer and Master in Architecture and Urbanism. He is a researcher at the Graduate Program in Design at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, and a member of LabVisual at the same university. He studies the design of museums, educational spaces, exhibitions and interactive environments, zoos, aquariums, among others, focused on interactivity, entertainment, and education.

Clice Mazzilli is an Architect and Doctor in Architecture and Urbanism, and an Associate Professor at the Design Department of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Sao Paulo. She coordinates the Graduate Program in Design and the Graphic Programming Laboratory, both of the same university. She studies creative processes, graphic visual language, environmental visual language, experimental processes, playful spaces, and editorial design.

How to quote this text: Ricca, D. E. P. and Mazzilli, C. T. S., 2019. Information diffusion in museums: digital technology, interaction and dialogue. Translated from Portuguese by Erik Soderberg. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 19. [e-journal] [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus19/?sec=4&item=12&lang=en>. [Accessed: 03 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 18, 2019

Abstract

This article approaches the diffusion of information for learning processes in museums, supported by interactive digital technology artifacts, Analytical categories of interaction typologies stem from bibliographic research and field survey. Relevant theoretical references were initially selected, in order to understand several categories of the concept of interaction as described by various authors. Then, we propose a categorization of interaction typologies that consider the interrelated input and output modalities, namely: linear, multiple and open. Nine resulting categories are associated with case studies selected and analyzed according to their opening, to elaborate and disseminate the information and the learning process through the user-machine interaction.

Keywords: Human-Computer Interaction, Cybernetics, Conversation, Learning, Museums

1 Introduction

Due to the spread of computers in the various scales of human life, the design has been gradually recognized as a major tool to humanize and make friendly interfaces with such devices, and thus expand the ability to meet our needs. Design is in charge of this function and has the means of designing technology directed to the users of such devices, from the area of knowledge of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The HCI discipline specifically targets the design of computer applications and interfaces for better machine interaction and usability. “A good computer system, like a good pair of shoes, should be natural, comfortable and serve without the user being aware of it.” (Faulkner, 1998, p.7). We note that the Humanities increasingly assume a quite relevant role in understanding the subjective aspects of people's consciousness when interacting. Its contribution clarifies the understanding of aspects of perception and cognition related to technological devices. From the perspective of the humanization of technology, this article has a transdisciplinary approach, aiming to discuss various types of user-machine interaction, and their possible influence on the construction of information in museum spaces.

To consider an artifact as interactive means to refer to a categorization of objects according to their ability to “behave”, activated by interactive technology (Moggridge and Atkinson, 2007). It means to give it the potential to capture user’s information and some space aspects in order to translate these into digital information, and consequently into communication through interaction. This experiment understands that to consider interaction as dialogue can build ways for new possibilities of understanding how design can contribute to constituting the information through interaction with digital artifacts. Consequently, we find exhibition and museum spaces to be the appropriate locus for this discussion, given that the use of technology in these institutions is a practice that is increasingly growing and being consolidated throughout the world, including Brazil.

This paper is a portion of one chapter of the author’s thesis written for his master’s degree, and its objective is to reflect on the dissemination of information for learning in museums through the use of interactive digital technology artifacts by proposing analytical categories of interaction typologies based on bibliographic and field research (Ricca, 2019). Parting from this, an interpretative reading of design strategies was developed in regard to a series of selected case studies. This experiment is therefore characterized as exploratory research, the method of which consists of site visits to selected museums. It is complemented by bibliographic and pictographic groundwork, including catalogs, photos, books, articles and other publication genres, of which 13 artifacts located in 11 different institutions were selected in total1.

2 Content mediation: interaction in dialogue, theoretical reference

The act of communication lies in mediating content, which, based in a medium, transmits a message. It is thought that knowing and delving into theoretical aspects of interaction can be a way to approach a greater understanding of design criteria for digital mediating artifacts in museums. Moreover, this can foster dialogue between human beings and machines, and, therefore, the elaboration of information and learning. It is worth highlighting the fact that in this article the term Communication cannot be reduced to verbal language; its meaning is expanded to also comprise interaction itself as a communicative activity.

One effective way to represent human-computer interaction is the feedback loop.This consists of a cyclical exchange of information in the form of data relayed from a human to a system – a computer, a mobile device, or a car, for example – and back to the human. Receiving this feedback, the person evaluates if this information has achieved the objectives that motivated the initial stimulus. This interpretation of the system output then directs the next action undertaken (Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009). In this way, it is understood that the cyclical nature of information enables new ways for it to elaborate and disseminate itself. This interactive loop model of systems dynamics suggests the following investigation: do different degrees of interaction exchange lead to different modes of information exchange? In order to discuss this point, we proceed next to the screening of various categories of the concept of interaction undertaken with selected authors. 2

2.1 Types of interaction

The human-machine relationship can occur in various ways, and it also allows its classification into multiple categories to facilitate its understanding and reading. Authors Dubberly, Haque, and Pangaro (2009) - in their article What is interaction? Are there different types? -conceive, in light of Gordon Pask's Second Order Cybernetics (1976), a systematization of interaction with support from what they call dynamic systems. For these specialists, a system is not considered interactive due to its characteristics per se, but to the nature of the information exchange that is realized between the elements of a system. These are classified into essential types: 0) linear, 1) self-regulating and 2) learning. Linear systems (0 order) react in a standardized manner to stimuli and their expressions.

Self-regulating systems (1st order) are characterized by giving different responses arising from the type of input they receive, adjusting their behavior, and modifying their responses through the stimuli collected in a cyclical way despite that this had been previously established in their programming. However, Dynamic learning systems (2nd order) are characterized not only by adjusting their behavior directly from the input, but also by learning from changes to the stimuli that are received. The system thus learns from the user, and vice versa, in a multicyclic or spiral manner in which information can be constructed constantly (Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009).

Table 1: Classification of interaction systems. Source: Adapted from Dubberly, Haque and Pangaro (2009).

From the authors' perspective, simply pushing a button (real or virtual) is not interaction, but rather a reaction. In a reactive system, the input and output – stimulus and response – are fixed. However, in interactive systems, the stimulus and response elements feedback in a way that produces a dynamic system, and, therefore, is progressively more interesting for the user (Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009). Starting with the systems discussed above, the authors elaborated six different interaction models as shown in Table 1.

In the 0+0system combination, Reaction, the inputis generated by a stimulus in a device – tapping, turning, signaling, pushing. According to Gordon Pask (1976), this action causes a predetermined and often limited reaction. Based on this description, it is noted that many of the content mediating artifacts in museums fall into this category. The 0+2 system combination, learning, denotes a typology of interaction that encompasses many human-computer interactions. In these, a learner system (a human) interacts in a process of linear input. The system responds, and the human adapts to the output. The human learns from the system; however, the system does not learn from the human. As Dubberly et al.say (2009), these are not characterized for allowing conversation itself since the machine does not learn from the inputsbrought by the user.

In system combination 1+2, Entertainment, the authors highlight the example of electronic games in which a system is created that progressively increases the level of difficulty according to a player's developing abilities. Design strategies like these begin introducing surprises and challenges that renew and reinforce interaction, contributing to the engagement through entertainment (Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009). In this category, rules, rewards, and challenges are deployed to increase the difficulty for users in competing or collaborating. In interaction 2+2, Conversation, there is a cyclic process of input and output in which two learning systems communicate with each other (Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009). In museums, allowing conversation in the interaction between content and visitor requires that there is, in fact, an exchange between systems.

In order to better understand and develop the implementation of interactive projects, architect, artist, and media designer Ruairi Glynn classifies interactions into three types based on their reactions to stimuli (Glynn, 2008). The first type starts with an automated reaction and has only two states, on and off and is characterized as being independent of external inputs. The second type is classified as reactive as it acts according to previously defined criteria. Many examples of these are erroneously characterized as interactive. For Glynn, a systemcan only be considered interactive when there is autonomy in the system itself that, by a variety of means, facilitates the achievement of the objectives initially established in its programming. Similarly, artist Jim Campbell (2000) characterizes interactive interfaces into two modalities. The first is a discrete interface, for which he cites the example of a carpet that triggers an image when a visitor closes a circuit by stepping on it. The person here does not interact with the program or the image, only the carpet with a button, so that, “... there is no dialogue, only the states of on and off.” (Almeida, 2014 p.131, our translation). Campbell's second classification is characterized by continuous interface, which occurs, for example, when a hundred buttons are arrayed on a carpet, and, by stepping separately on each one, a hundred responses are generated and displayed on a monitor which has been uniquely stimulated based on the mapping of the person’s position (Campbell, 2000).

In discussing interactive media with a propensity for communication, Jens Frederik Jensen defines interaction as, “... a measure of a medium's potential ability to allow the user to influence the content and/or form of mediated communication,” (2008, p.129). Based on this definition, he describes four subconcepts of interaction: transmission interaction consisting of a "one-way" medium such as a TV that does not allow the user to make requests other than to change the channel; consultation interaction in which there is the possibility of allowing the user to choose pre-produced information, as on an Internet website; registration interaction in which there are automated responses given to users from their needs and actions (Jensen gives as an example systems that automatically sense environmental stimuli and adapt, such as security systems, home-shopping, automatic lights in smartphone interfaces, etc.); and conversation interaction where there is “two-way” sharing, for example, in the exchange of emails between two people in a human-to-human interaction over the Internet (Jensen, 2008). Considering the taxonomies shown above, a table has been elaborated in which are reproduced, in summary, categories drawn by each author.

Table 2: Definitions of interaction among various authors. Source: Author’s elaboration based on the referenced literature (2018).

3 Design strategies - stimulus and response diagrams

Analyzing the table in the previous section, a pattern categorizing outputs in human-computer interaction can be perceived and, in this article, we propose to analyze these multiple definitions based on three typologies: 1) linear – when there is automated input or output with standardized responses in which the participant has few, or only one, possibility of stimulus; 2) multiple – when an output that is also standardized, though, with possible variables depending on the stimulus elicited, which allows a multiplicity of inputs from the user and thus greater resourcefulness in a system; and 3) open – when feedback between inputs and outputs is permitted, as in a conversation, indicating a dialogue between human and system which is non-standard, cyclical and variable, and in some cases approaching a randomness randomly opening itself to the undetermined. These three descriptions are illustrated graphically in Figure 1.

Attempting to treat, in an equivalent manner, the reading of actions as much from the perspective of the machine as in relation to the human being, we proposed to classify the inputs and outputswithin these two types in interaction with digital technological artifacts. This way, a classification is carried out that seeks to understand the typologies of the possibilities of user actions, as well as the machine response modalities within the same structure of interpretation in order to understand the different possibilities for the construction and dissemination of information in such categories.

Regarding this classification as applied to content-mediating digital technology artifacts, a way of reading is proposed which seeks, visually and conceptually, to facilitate the understanding of the artifacts’ proposals for interaction that have the visitor, as much the structuring element, act as the system. The figure here shows the standard diagram adapted to each typology. On the left side in magenta is the input from the user, which in this case is of the multiple type. On the right side, the open output type is represented by a semicircle. This way of illustrating the interaction applies to inputs coming from the visitor as much as to outputs from the machine. In addition to this, we tried to map these possibilities as they apply to the actual cases we visited while considering the proposed outline of the research, that is, the relationship between visitors and the digital artifacts that mediates content in museums. There are, we find, three sorts of categories which, when combined, form nine typologies of distinct characteristics of information exchange through interaction, as can be seen in the following figure.

3.1 3.1Linear Stimulus - Linear Response (1-A)

The classification typology 1-A regards a stimulus with a linear character on the left side of the circle followed by a linear response on the right side of the circle. Such a relationship with a digital artifact is characterized by its simple understanding and limited, unilateral possibilities for information exchange. Examples of this type are largely found in museums using audio guides in which the visitor presses a predetermined code and receives a pre-recorded response.

An example of this typology can be found at the Ottobock Science Center in Berlin. It deals with the motor functions of the human body, and utilizes projection linked to simple sensors. The interface 1) More than skin deep is activated by parts of the human body as they initiate animated projections on several tables, and through which the user can learn about tendons and muscles. 2)Test your balance! is an interface in which the visitor walks on a straight line drawn on a patch of floor where images from varying heights are projected. These offer three levels of difficulty and demonstrate how a virtual stimulus can produce an imbalance in the brain and, consequently, in other parts of the body. This example in particular opens a space for playful social interactions to occur, even while it only deals with a linear-linear typology.

Fig. 5: Image A: Interaction 1) More than skin deep.Source: Ricca, 2019. Image B: Interaction 2) Test your balance! Source: ART+COM Studios. Available in: <https://artcom.de/en/project/science-center-medical-technology/> [Accessed November 2019].

3.2 Linear Stimulus - Multiple Response (1-B)

Interaction type 1-B as well as 1-A only allow linear stimuli, that is, of a singular character, however, they also accept a certain amount of variation in the possibilities for response. A didactic example of this includes the act of throwing a virtual die wherein the human is only allowed to have a linear behavior by throwing it, and by which six possibilities of response usually emerge, thus characterizing the output modality as multiple. This artifact typology was found in interface3) Waltz-Dice-Game at the Haus der Musik Museum in Vienna, where it is possible to compose a song together with other visitors based on the simultaneous rolling of four virtual dice. The composition occurs with multiple possible combinations and can be shared virtually with users.

Fig. 7:Waltz-Dice-Game on Haus der Musik Museum. Source: Hanna Pribitzer. Available at: <http://bit.ly/2ZemXGk> [Accessed August 2019].

3.3 Linear Stimulus - Open Response (1-C)

In the context of linear possibilities in type 1-C, the artifacts that allow the elaboration of open responses are those in which the visitor's stimulus, even if limited, can produce constantly changing responses and information. A fictitious example of an interface of this type would be an installation in which, using a presence sensor, some random kind of audiovisual phenomenon is expressed. The presence of a visitor would be categorized as a linear input, as it cannot be changeable; whereas the media, being random and without standards, could be categorized as open. It turns out that this is a typology that was not found in the researched cases. When dealing with examples that propose to be content, these consist mainly in the sense of the construction of information and not in the interaction itself. It is assumed that because its open nature of response comes from a linear stimulus, this has limited characteristics available for reproduction.

3.4 Multiple Stimulus - Linear Response (2-A)

Regarding the context of multiple stimulus possibilities now, the category 2-A has a linear type of response. This mode of relation with the artifact is characterized by denoting several possibilities of interaction configuration which boost standardized and constant responses. By allowing more than one mode of action, these types of artifacts tend to have a lot of potential for engagement as they give rise to multiple possibilities, and as they give the visitor a good degree of autonomy for deciding what they want and what they don't want to learn from the information. Observing that, due to the multiplicity of the stimuli and standardization of responses depending on the user, the designers tend to generate too much content, requiring time and patience to access all the information made available, and, often, it is not accessed in its entirety. This occurred, consequently, in examples 4) Body Scanand 5) Narratives by Tokens. It was noted that, in these cases, the visitor is enchanted by the possibility of interaction, but soon gets tired of the linearity of the response, quickly moving on to the next work or installation of the museum and thus limiting the elaboration of information by not allowing an effective exchange with the user.

Example 4), found in the Micropia Museum in Amsterdam, is meant to show the life of microbes. The interface consists of a large screen with a sensor that detects poses of the visitor's body. The system uses these poses as controls as visitor´s bodyparts are freely moved and reflected by a virtual human body as if it was a scanner. By selecting a specific body part, the extensive content related to the bacteria of that chosen part is shown. Example 5), found in the Vikings section of the Moesgård Museum, is designed for ethnography and is located in the city of Aarhus, Denmark. It consists of hung pendants tokens, inside which there are radio frequency ID chips (RFIDs). Visitors, upon entering the room, choose one or more tokens relative to the character that most interests them. With these, they can hear different versions of narrative explanations about the sculptures or historical objects just by placing the desired pendant on the receivers.

Fig. 10: Image A: Interaction 4) Body Scan. Design by Kossman.dejong. Source: Thijs Wolzak. Available at: <http://bit.ly/2P3Oo1U> [Accessed August 2019]. Image B: Interaction 5) Narratives by Tokens. Source: Ricca, 2019.

3.5 Multiple Stimulus – Multiple Response (2-B)

This is the typology most often found in the spaces visited, and these allow the visitor to

have a certain multiplicity of possible actions, allowing also for varied responses, without, however, being fully open. It was noted that this type of interaction generates, at times, stimuli considered enriching for visitors, as it allows a greater dissemination of information in the exchange.Case 6)Microbe Wall consists of a set of 30 stamp machines located in each one of the exposition stations at the Micropia Museum. When in front of an explanation regarding a specific microorganism, participants can stamp it on their visitor´s map, which, at the end, can be read on a digital table that projects animations with the collected organisms. Case 7) Game of Droughts, located at the Cais do Sertão Museum in Recife, consists of an interaction in which singer Tom Zé narrates an interactive game of strategic challenges with the objective of ending the drought problem. The game system is based on competition between participants. The winner is the one who implements the most solutions that not only solve the drought problem temporarily, but also in the long run.

Fig. 12: Image A: Interaction 6) Microbe Wall. Source: ART+COM Studios. Available at: <https://artcom.de/en/project/micropia/> [Accessed November 2019]. Image B: Interaction 5) Game of Droughts. Source: Livre Opinião – Ideias em debate. Available at: <shorturl.at/gnAC3> [Accessed November 2019].

In the chosen examples, it was possible to notice that such multiplicity of input and output is also a generator of social interactions, dialogues, and moments of playfulness, as perceived in these and other visited cases. Thus, relevant aspects are produced in the sense of transcending the limit of the identified multiplicity, enabling different manners of construction and dissemination of didactic information from the different design strategies of these artifacts.

3.6 Multiple Stimulus - Open Response (2-C)

The classification 2-C is characterized by a multiplicity of stimuli (inputs) giving rise to variable response possibilities (outputs). When analyzing the application of this proposed typology, it was noted that, as with categories 1-B and 2-C, the forms of input are more limited here than those of the output. Category 2-C aligned with only one of the cases in this exploratory research, which is case 8) The Portrait Machine located in the Aros Museum of contemporary art. This interface enables the visitor to strike a specific body pose among a limited number of options and, from its captured image, generate an output of collages with different parts of various works from the collection. This response is characterized as open because it never repeats and is always variable, and it depends on visitors and their interaction with each other. The image shows the result generated from the researcher's interaction with this interface.

3.7 Open Stimulus – linear response (3-A)

In the context of open stimulus modalities, category 3-A is defined as an interactive artifact typology in which visitors have a great deal of freedom within the system and the system responds to their information in a standardized way. The case that fits this description is 9) Exploded View, which is located in the Swiss National Museum. In it, the visitor, by moving a concrete sphere, can go to several monuments around the world. Representations of the monuments are constructed of point clouds generated by the triangulation of innumerable tourist photos taken from different angles at these locations. The visitor’s point of view has complete freedom to move about while the interface monuments do not change at all and only show varying angles in point clouds.

3.8 Open stimulus – multiple responses (3-B)

In category 3-B, the left side indicates that the possibilities for information input are open, and they produce multiple system responses, as depicted. This interaction typology allows the visitor to have freedom in their way of stimulate the system, and the system responds with multiple, though limited, possibilities. A case that expresses this typology is 10) Sketch your idea!at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in New York. In it, visitors can create any shape they want with a system containing a pen and a digital table. The system interprets possible modeling options within the limitations of the collection which then transforms into different typologies of design artifacts: table, lamp, chair, etc.

Other cases that fit this category are several interfaces that use Artificial Intelligence (AI) to interpret visitor stimuli, such as partnerships between IBM and the Museum of Tomorrow, creating the system 11)IRIS +, and the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo that exhibits the project 12) The Voice of Art. These partnerships have applied Watson AI to these cultural spaces, demonstrating a machine learning system response emitterthat, starting with open questions coming from the user, can even be interpreted by visitors as a fluid conversation, a dialogue in real-time with the machine, that is, in fact, based on predetermined responses recorded by humans beings.

Fig. 18: Image A: Interaction 10) Sketch your idea! Source: Chan and Cope (2015). Image B: Interaction 11) IRIS+. Source: Guilherme Leporace/CASACOR. Available at: <https://casacor.abril.com.br/noticias/iris-a-nova-inteligencia-artificial-do-museu-do-amanha/> [Accessed November 2019]. Image C: Interaction 12) The Voice of Art. Source: Ricca, 2019.

3.9 3-C: Open stimulus – open response (3-C)

From the analyzed cases, it was decided that allowing freedom of stimuli and responses within open possibilities offers different ways for the visitor to relate, be it with the information itself, with the interface, or with the museum space and other visitors, thus permitting space for the unexpected to occur such that surprise can manifest itself and new forms of information construction can take place. Modalities of openness like these arise, as represented on both sides of the circle in the figure, and stimulate more playful possibilities for the visitor's relational interactions and contain aspects outside the interface itself that often make the interaction richer and more social and the dissemination of information, in most cases, more effective. For these reasons, this typology of categorization is considered closest to the definitions of dialogic interaction cited by several authors in the theoretical references (Campbell, 2000; Carneiro, 2014; Dubberly, Pangaro and Haque, 2009; Glynn, 2008).

The cases chosen to exemplify this category are: 13) Reliefs of the Earth in 3D at the Catavento Museum in São Paulo; and 14) The Recording Booth at the ARoS Museum. Case 13) consists of a sandbox on which is projected, via augmented reality (AR), an image of reliefs and contours from the heights found in hills and slopes created by visitors themselves by handling the sand. The projector is connected to a computer that is integrated with a Kinect device that perceives distances and modifies the projected image in real-time to teach topography. Case 14) consists of a recording booth in which there is a screen that displays instructions. There, two or more visitors are invited to answer questions about a work they select from the collection selected by them which are not aimed at testing knowledge, but instead stimulating questions that foster dialogues and social interactions. The recorded material becomes a video and a GIF sent by email for use and sharing and it remains in constant replay on museum screens, effectively making the visitor part of the collection. These enable the visitor to interact openly with the interface, which also responds in a unique way.

Fig. 20: Image A: Interaction 13) 3D Earth Reliefs. Source: University of California, Davis. Available at: <https://www.oceanit.com/products/augmented-reality-sandbox> [Accessed November 2019]. Image B: Interaction with Remote User 14) The Recording Booth. Source: Ricca, 2019.

4 Conclusion

Several types of interactions and possible consequences of their use for knowledge building and visitation experience enhancement were indicated in the text. The modality of classification realized here depended on the citation of practical examples in order to reflect the varied possibilities of using digital technology in content mediators located in exhibition spaces. With the cases listed here and the proposed analyses, it could be inferred that diverse design strategies can be directly related to subjective intentions directed at visitors, allowing new users to be encouraged to engage in these experiences, which in turn allow a broadening of social strata in these institutions as well as innovative possibilities for information transmission.

It was noted that the authors and experts cited here report in a similar manner on these typologies of interaction. By using diversified nomenclatures, many seek to define the same structural essence in de facto interactive environments. In sum, what these authors convey is a division based on how the type of logic routine for input and response output is implemented. For future works, it is interesting to note how this demand for more significant relationships with machines is repeated by several authors, deepening the points where these are differentiated. It is clear that interactivity at the dialogic level (3-C - open-open) is a challenge to be met, and that few cases show themselves as successful in this regard.

With the events analyzed here, the assumption is valid that, for the institution, choosing to allow interaction with such interfaces means giving visitors the possibility to change the stimuli and the responses of the system, thus giving rise to various forms of elaboration and dissemination of content. Further, this way the designer does not have to limit possibilities but instead can widen them, and, in a positive way, explore rules and limitations and also playful, spontaneous social relations. According to Glanville (2001), the interaction itself deals with the undetermined and is a product of a circular, non-causal and uncontrolled relation. Gordon Pask discusses the importance of interaction and the need for novelty so that people engage in situations with their environment: “Man is inclined to seek novelty in his environment and, having found a new situation, to learn to control it” (1971, p.76). Based on these and other reflections pointed out in this paper it is possible to assume that a simple series of actions in a linear sequence can be limited and fail to open a space to novelty, that is, to the element of surprise in an interaction, and thus restrict the elaboration of information by limiting it in its possibilities.

References

Almeida, M. A., 2014. Ambientes interativos: a relação entre jogos e design para a interação. Ph.D. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

Almeida, M. A., 2016. A teoria da ludificação e os ambientes responsivos. Blucher Design Proceedings, 3(1), pp.838-843.

Campbell, J., 2000. Delusions of dialogue: control and choice in interactive art. Leonardo, 33(2), pp.133-136.

Carneiro, G. P., 2014. Arquitetura interativa: contextos, fundamentos e design. Ph.D. Universidade de São Paulo.

Chan, S. and Cope, A., 2015. Strategies against Architecture: Interactive Media and Transformative Technology at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Curator: The Museum Journal, 58(3), pp.352-368.

Dubberly, H., Pangaro, P. and Haque, U., 2009. What is interaction?: are there different types? Interactions, 16(1), pp.69-75.

Faulkner, C., 1998. The essence of human-computer interaction. London: Prentice Hall.

Glanville, R., 2001. And he was magic. Kybernetes, 30(5/6), pp.652-673.

Glynn, R., 2008. Conversational environments revisited. In: Meeting Of Cybernetics & Systems Research. Graz, Austria.

Haque, U., 2007. The architectural relevance of Gordon Pask. Architectural Design, 77(4), pp.54-61.

Jensen, J. F., 2008. The concept of interactivity: revisited: four new typologies for a new media landscape. In: ACM, pp.129-132.

Moggridge, B. and Atkinson, B., 2007. Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pask, G., 1971. A comment, a case history and a plan. In: Reichardt, J. (Ed.)., 1971. Cybernetics, Art and Ideas. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphics Society. pp.76-99.

Pask, G., 1976. Conversation theory: Applications in education and epistemology. Amsterdam/New York: Elsevier.

Ricca, D. E. P., 2019. Artefatos tecnológicos digitais interativos: estratégias projetuais para fomento da mediação de conteúdo em museus. Master. Universidade de São Paulo.

Ricca, D. E. P. and Mazzilli, C. D. T. S., 2018. Content mediation and digital technology in museums: design strategies to enrich the visitor's experience. In: Congresso da Sociedade Iberoamericana de Gráfica Digital ( SIGraDi ).

1 1) More than skin deep and 2) Test your balance! at Ottobock Science Center in Berlin; 3) Waltz-Dice-Game at the museum Haus der Musik in Vienna; 4) Body Scan and 6) Microbe Wall at the Micropia Museum in Amsterdam; 5) Narratives by Tokens at the Moesgård Museum in Aarhus, Denmark; 7) Game of Droughts at the Museu Cais do Sertão in Recife, Brazil; 8) The Portrait Machine and 14) The Recording Booth at the Aros Museum in Aarhus, Denmark; 9) Exploded View at the Swiss National Museum; 10) Sketch your idea! at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in New York; 11) IRIS+, a partnership between IBM and the Museum of Tomorrow in Rio de Janeiro; 12) The Voice of Art, a partnership between IBM and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo; 13) Revelations of the Land in 3D at theMuseu Catavento in São Paulo.

2 It is noteworthy that this compilation of authors and their respective concepts regarding different forms of interaction was also addressed by the author in the article "Content mediation and digital technology in museums: design strategies to enrich the visitor's experience", published in SIGRADI in 2018 (Ricca and Mazzillo, 2018).