Interfaces maliciosas: coleta de dados pessoais em aplicativos

André Lemos é Engenheiro Mecânico e Doutor em Sociologia. É Professor Titular do Departamento de Comunicação e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporâneas da Universidade Federal da Bahia, onde coordena o Lab404 - Laboratório de Pesquisa em Mídia Digital, Redes e Espaço. Atua nas áreas de comunicação e sociologia, com ênfase em cultura digital ou cibercultura. É membro do Comitê Gestor do Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Democracia Digital.

Daniel Marques é Bacharel em Design e Mestre em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporâneas. É Professor Assistente da Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia, e pesquisador no Lab404- Laboratório de Pesquisa em Mídia Digital, Redes e Espaço, da Universidade Federal da Bahia, onde estuda Design, inovação e cultura, Visualização de dados e mapping art, Cultura, comunicação e sistemas de linguagem.

Como citar esse texto: LEMOS, A.; MARQUES, D. Interfaces Maliciosas: estratégias de coleta de dados pessoais em aplicativos. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 19, 2019. [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus19/?sec=4&item=2&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 18 DE AGOSTO DE 2019

Resumo

O artigo analisa as interfaces maliciosas (IM) presentes em 10 aplicativos usados pela municipalidade de Salvador para a coleta de dados pessoais. Tais aplicativos atuam na construção e experiência da cidade contemporânea, mediando diferentes aspectos da vida social urbana. Essa nova dimensão informacional da cidade, por sua vez, impõe desafios à manutenção da privacidade do cidadão ao fomentar a maximização da produção e coleta de dados pessoais sensíveis. A partir de uma escala de gravidade (EG), as interfaces foram avaliadas com o intuito de identificar os tipos de IM presentes e os graus de ameaça à privacidade dos usuários. Constata-se que todos os aplicativos analisados têm IM, sendo majoritário o nível 1 (leve), demonstrando tendência a sua naturalização. Essas IM fazem parte da expansão da plataformização da sociedade, do processo de dataficação e do agenciamento performativo dos algoritmos (PDPA).

Palavras-chave: Dark patterns, Aplicativos, Privacidade, Salvador

1 Introdução

A produção da vida social na cidade contemporânea se encontra cada vez mais imbricada com as tecnologias digitais de informação e comunicação. Smartphones, assistentes virtuais, aplicativos, algoritmos e redes sociais, por exemplo, passam a ocupar um espaço significativo na tessitura do social, mediando relações de sociabilidade, afeto, trabalho, educação e lazer. O espraiamento dessas mediações, por sua vez, leva ao extremo a ideia de uma “sociedade informacional”, tendo em vista a centralidade da produção da informação – e do acesso a uma quantidade cada vez maior de dados – na geração de valor para o chamado capitalismo de plataforma/vigilância (ZUBOFF, 2015).

O dado, portanto, torna-se a nova commodity do capitalismo contemporâneo, enquanto o cidadão e a cidade se configuram enquanto fontes desse material. Nesse sentido, à medida em que o valor dos dados se torna maior e mais evidente, passamos a verificar um maior esforço por parte de múltiplas instituições – públicas e privadas – em coletar e extrair valor dessas informações, colocando em risco a manutenção da vida privada. Tendo em vista que a produção e a coleta de dados são o objetivo maior do capitalismo de vigilância, faz-se necessário politizar as estratégias e as mediações através das quais busca-se domesticar o cidadão a produzir cada vez mais dados. O capitalismo de dados é uma forma de “construção da informação”, colocando em risco a privacidade dos cidadãos no espaço urbano.

O objetivo desse artigo, portanto, é discutir o que se vem chamando de Dark Patterns (DP), interfaces que levam os usuários a desempenhar determinadas ações com intenções diversas. Um dos objetivos é coletar dados pessoais, não necessariamente imprescindíveis para o objetivo do serviço. Essa coleta caracteriza a “dataficação” para fins comerciais ou técnicos. Ao induzir ações de captação desnecessária de dados pessoais, os DP ameaçam a privacidade. O interesse nessa temática vem justamente da crítica à essas ameaças presentes em aplicativos e websites (ASH, et al., 2018a, 2018b). Analisamos 10 aplicativos em uso pela Prefeitura Municipal de Salvador, BA. O artigo parte de uma perspectiva neomaterialista e pragmática (FOX; ALLDRED, 2017; LEMOS, 2019a), analisando a ação dessas interfaces. Indicamos uma escala de gravidade (EG) de três níveis para análise, descrição e comparação das interfaces. Propomos chamar esses padrões de “interfaces maliciosas” (IM).

2 Interfaces Maliciosas (IM)

O termo dark pattern (DP) foi proposto por Harry Brignull, doutor em psicologia cognitiva pela Universidade de Sussex, profissional da área de design de interação (UI) e experiência do usuário (UX), em uma palestra proferida no evento UX Brighton, em 20101. São estratégias de design utilizadas em interfaces digitais (websites, aplicativos, wearables etc.) e derivam da tradição de padrões de design (design patterns)2. A expressão ganhou popularidade e tem sido apropriada por profissionais e acadêmicos do design e da computação. Recentemente o tema apareceu no Financial Times3, Gizmodo4, The New York Times5 e The Verge6.

Para Brignull, os DP não são meramente bad designs. Eles são antipatterns, criados para fazer com que o usuário realize ações de interesse do aplicativo/empresa sem que ele se dê conta ou tenha como evitar. Diferentemente dos bad designs, os DP se caracterizam pela intencionalidade obscura, desenvolvidos para obtenção de resultados específicos sem explicações ao usuário. Nas suas palavras, “esse é o lado sombrio do design e, como esse tipo de padrão não tem nome, proponho que passemos a chamá-lo de dark pattern” (tradução nossa) (BRIGNULL, 2010, s.p.). Essas estratégias se baseiam na exploração de atributos cognitivos e psicológicos dos usuários, fazendo com que estes não percebam que há um agenciamento do seu comportamento. Brignull propôs uma taxonomia inicial dos DP, catalogando 11 espécies diferentes7, as quais foram posteriormente expandidas pela literatura.

Propomos traduzir o termo "dark patterns” por “interfaces maliciosas” (IM). Nesse artigo vamos discutir as interfaces maliciosas (IM) com relação ao problema do uso de dados pessoais e as ameaças à privacidade. O desenvolvimento das IM para a maximização da produção, coleta e processamento de dados pessoais situa-se em um contexto mais amplo: a cultura da PDPA (LEMOS, 2019a, 2019b) – plataformização da sociedade (VAN DIJCK; POELL; DE WAAL, 2018), dataficação (MAYER-SCHONBERGER; CUKIER, 2013) e performatividade algorítmica (BUCHER, 2017; DANAHER, 2016).

Trata-se de fenômenos que caracterizam o atual estado da cultura digital, apontando para a expansão das plataformas digitais na mediação do cotidiano. A plataformização da sociedade, nesse sentido, diz respeito à crescente presença de plataformas digitais – geralmente produtos e serviços associados ao GAFAM8 – na mediação e realização da vida social. Essas mediações ocorrem, majoritariamente, através da ação de sistemas algorítmicos performativos que atuam na organização da vida social a partir do projeto das plataformas. Como a PDPA desenvolve-se em meio à expansão do capitalismo de dados (ou de vigilância) (SRNICEK, 2017; ZUBOFF, 2015), considera-se o dado pessoal como a principal commodity (SADOWSKI, 2019), dada a necessidade de projetar sistemas computacionais capazes de maximizar sua produção, coleta e processamento, ou seja, “dataficar” a vida social. O termo PDPA, portanto, refere-se à integração desses fenômenos: as plataformas digitais agem e se materializam a partir da implementação de algoritmos performativos, e de processos diversos de coleta de dados pessoais (dataficação).

Desde 2010, a literatura sobre IM se diversificou em áreas e temas tais como o design de games (ZAGAL; BJÖRK; LEWIS, 2013), as interações por tecnologias de proximidade (GREENBERG, et al., 2014), a violação da privacidade e maximização de processos de dataficação (BÖSCH, et al., 2016; DOTY; GUPTA, 2013; FRITSCH, 2017), as implicações éticas (GRAY et al., 2018), o ativismo em plataformas digitais (TRICE; POTTS, 2018), as interfaces físicas e de voz (LACEY; CAUDWELL, 2019), entre outros. Autores destacam, inclusive, a instrumentalização de desenvolvedores para a utilização de IM enquanto estratégia competitiva (LEWIS, 2014; NODDER, 2013).

Das questões recorrentes na literatura, destacamos quatro pontos centrais: a) o problema da intencionalidade; b) o foco na observação das microinterações; c) os aspectos éticos e; d) os fatores psicológicos. O problema da intencionalidade é a questão mais comum e boa parte da literatura tende a reconhecê-la como o objetivo maior das empresas. Na nossa postura pragmática, parece ser muito subjetivo afirmar intencionalidade e mais produtivo analisar os efeitos concretos das IM. Na maioria dos casos, elas se enquadram nos limites da legislação vigente (DOTY; GUPTA, 2013).

Muitos experimentam o “paradoxo da privacidade” (WILLIAMS; NURSE; CREESE, 2016). Ao avaliarem o custo-benefício da concessão de dados pessoais em troca de bens e serviços, usuários preocupados com a privacidade acabam cedendo. Esse paradoxo torna-se mais complexo pois dificilmente o usuário é capaz de aferir o valor e as consequências do fornecimento dos seus dados. A assimetria entre o poder das plataformas e a capacidade reduzida de negociação dos usuários gera um processo de naturalização das IM como paradigma hegemônico do design de interação. A existência de literatura dedicada a encorajar e oferecer suporte à implementação de IM aponta para esse cenário (LEWIS, 2014; NODDER, 2013).

Tomemos dois exemplos de IM antes de nos debruçarmos sobre o nosso corpus empírico: os aplicativos Mi Fit e Bike Itaú.

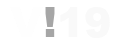

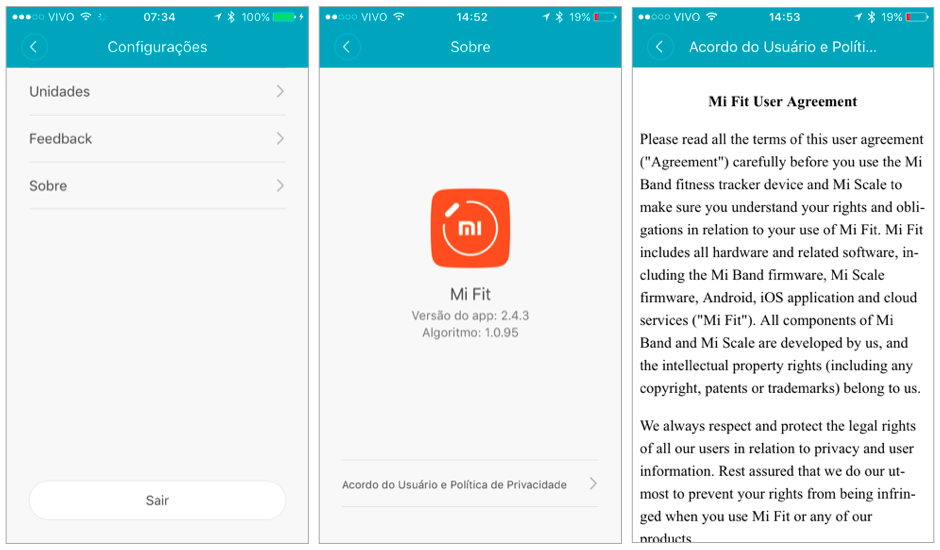

O Mi Fit acompanha as smart bands da marca chinesa Xiaomi. Há dificuldades para visualizar documentos importantes tais como o “Acordo do Usuário” e as “Políticas de Privacidade”, conforme podemos visualizar na Figura 1. Na tela “Configurações” não há nenhum indicativo de que eles estão na seção “Sobre” e, mesmo que o usuário consiga chegar aos documentos, não há uma preocupação em adequar o texto jurídico, longo e complexo, à situação de leitura em telas de smartphones. No entanto, a presença desses documentos é obrigatória e vista como uma boa prática na manutenção da privacidade (COLESKY; HOEPMAN; HILLEN, 2016; HOEPMAN, 2014; PATRICK; KENNY, 2003). Para usar o aplicativo, o usuário deve dar o seu consentimento, mesmo com dificuldade em acessar esses documentos. A materialidade da alienação no aplicativo indica a IM. Como todas, elas se produzem em um espaço assimétrico de negociação (ASH, 2018b). O efeito imediato é o aumento da leniência dos usuários em relação a coleta de dados realizada pela Xiaomi.

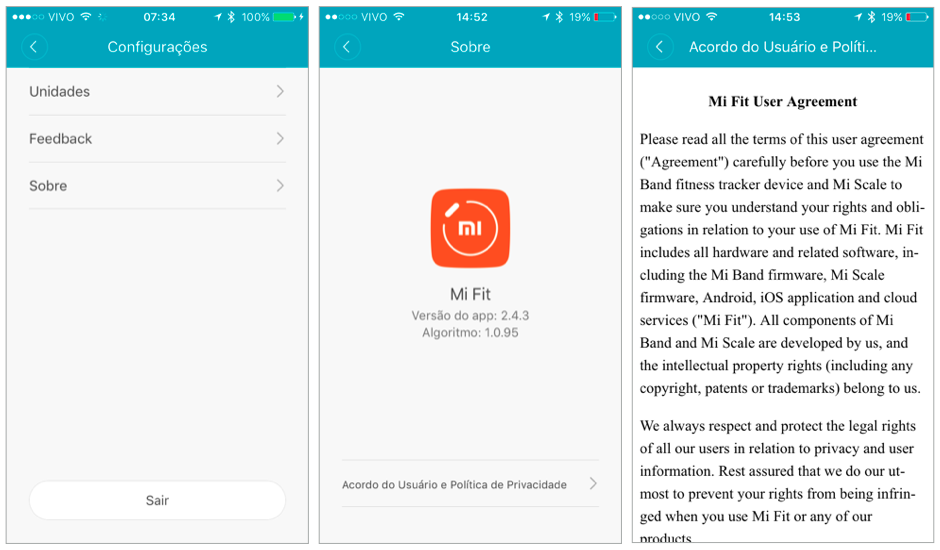

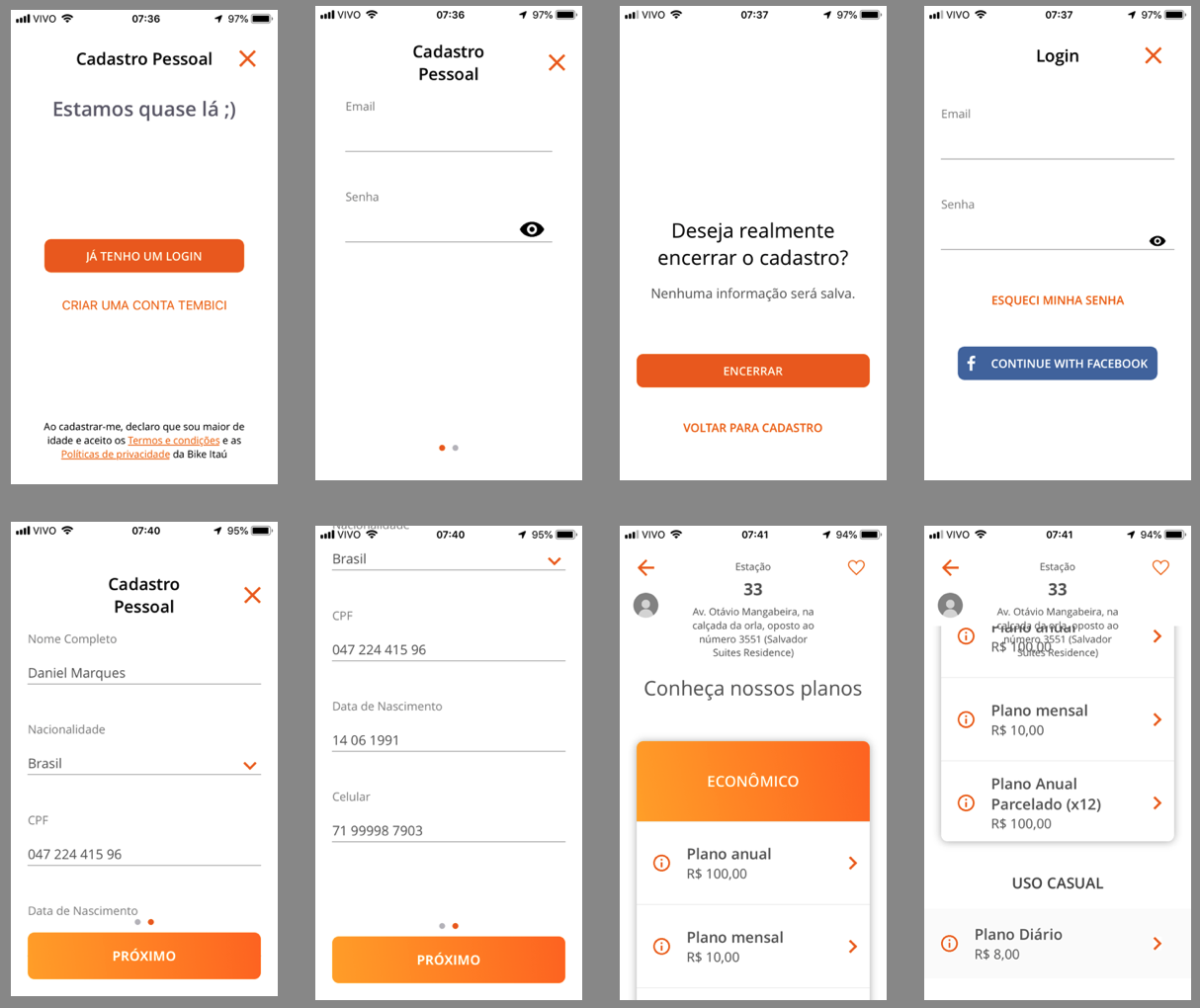

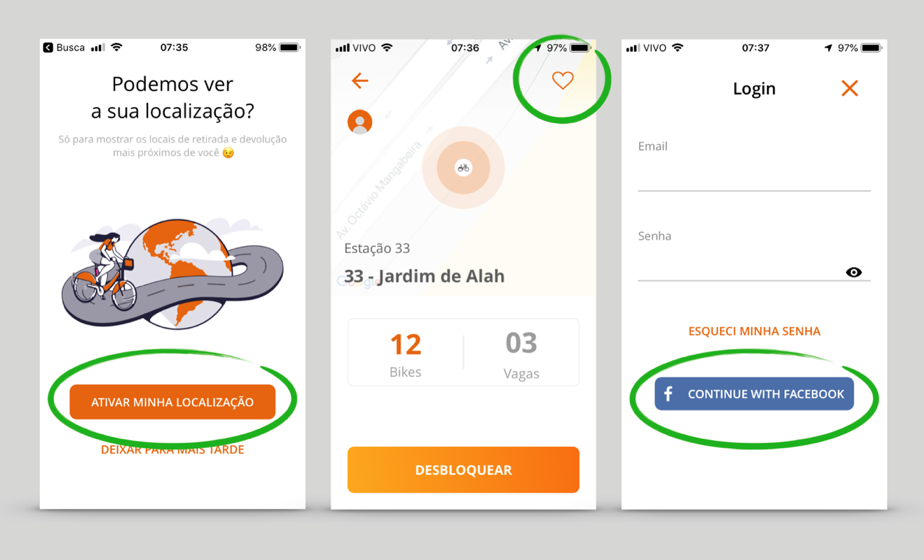

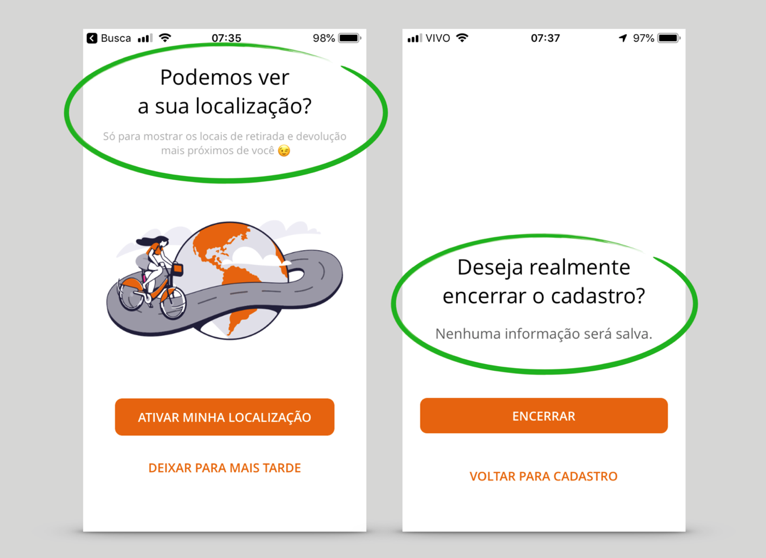

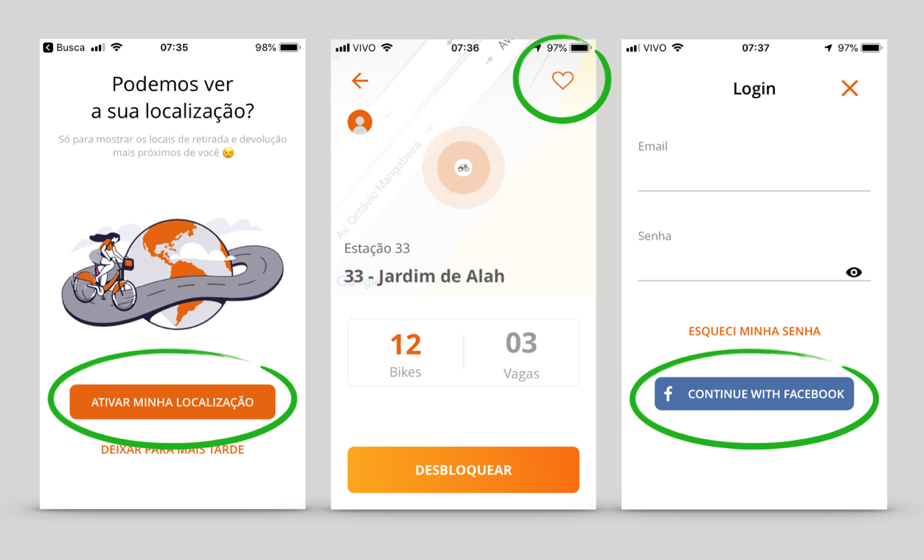

Outra IM comumente encontrada em aplicativos é o Confirmshaming, estratégia discursiva visando constranger o usuário a ceder o dado. No exemplo do Bike Itaú, apresentado na Figura 2, a primeira tela solicita o acesso à localização em tempo real do usuário, enquanto a segunda estimula o usuário a concluir o cadastro, afirmando que o dado será coletado “só para mostrar os locais de retirada e devolução mais próximos de você”. Ironicamente, na Política de Privacidade9 consta explicitamente que os dados coletados podem ser compartilhados com parceiros. Na segunda tela, a entonação do texto é punitiva, informando que o abandono do cadastro acarretará mais trabalho no futuro, já que as informações não serão salvas.

3 Metodologia

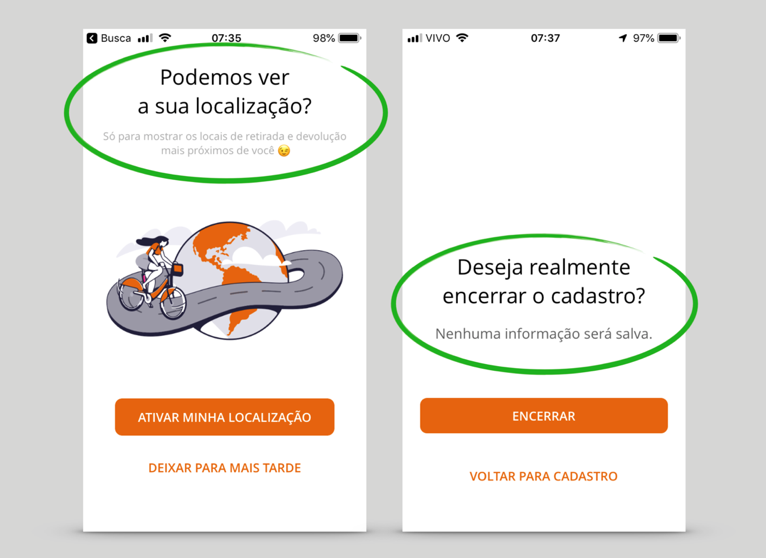

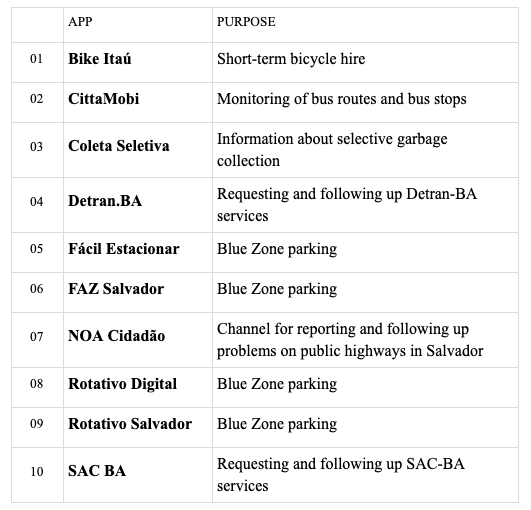

Tendo em vista o cenário delineado acima, buscamos verificar a presença de IM e a ameaça à privacidade em 10 aplicativos, conforme Quadro 1, escolhidos por oferecerem serviços de interesse público na capital baiana, desenvolvidos por empresas privadas ou pelo Estado. Foram excluídos aqueles destinados a usos específicos (por nicho, como funcionários públicos, por exemplo). A análise das telas principais de cada aplicativo (aquelas que negociam algum tipo de dado pessoal, tanto a partir de requisição formal – formulários, cadastros, pedido de consentimento etc. – quanto a partir da interação com as funcionalidades) foi realizada utilizando o software ATLAS.ti10. A média de telas analisadas foi 8,1/app. O aplicativo com maior número de telas analisadas foi o Bike Itaú (15); no outro extremo, encontra-se o SAC BA (4).

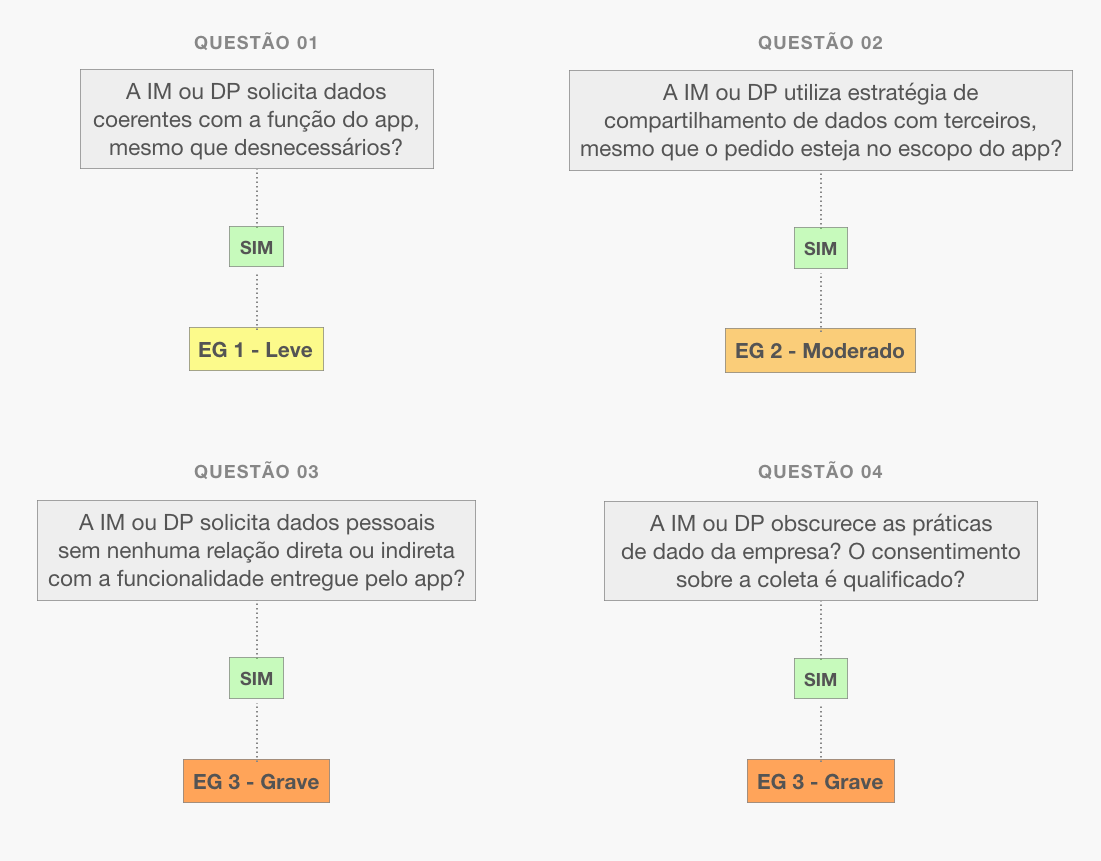

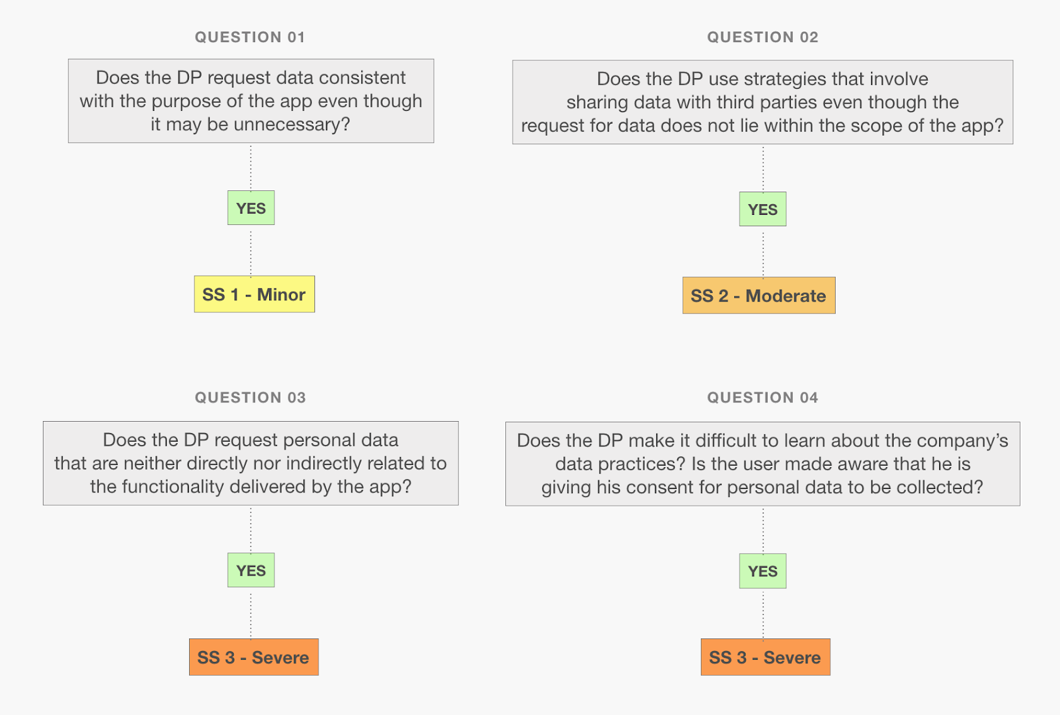

Após a primeira codificação das IM, criamos diferenças de graus em uma “escala de gravidade” (EG) em termos de ameaças à privacidade. Essa diferenciação foi necessária para desenvolver análises comparativas. Propomos a seguinte EG: 1 - nível leve; 2 - nível moderado e 3 - nível grave. No nível leve (1) estão enquadrados as IM que prescrevem a coleta de dados pessoais desnecessários para a realização da tarefa, mas que possuem alguma relação com a funcionalidade do aplicativo. No nível moderado (2) estão as IM que facilitam o compartilhamento dos dados pessoais com instituições externas, sendo que os dados solicitados estão de alguma forma envolvidos diretamente com o objetivo do serviço. O nível grave (3) é o das IM que coletam dados irrelevantes à tarefa e os compartilha com terceiros e/ou alienando o usuário do processo de coleta. Um aplicativo pode ter grau 3, sem ter graus 1 ou 2, e assim sucessivamente. É possível verificar o esquema de classificação na Figura 3.

4 Distribuição das IM por aplicativo

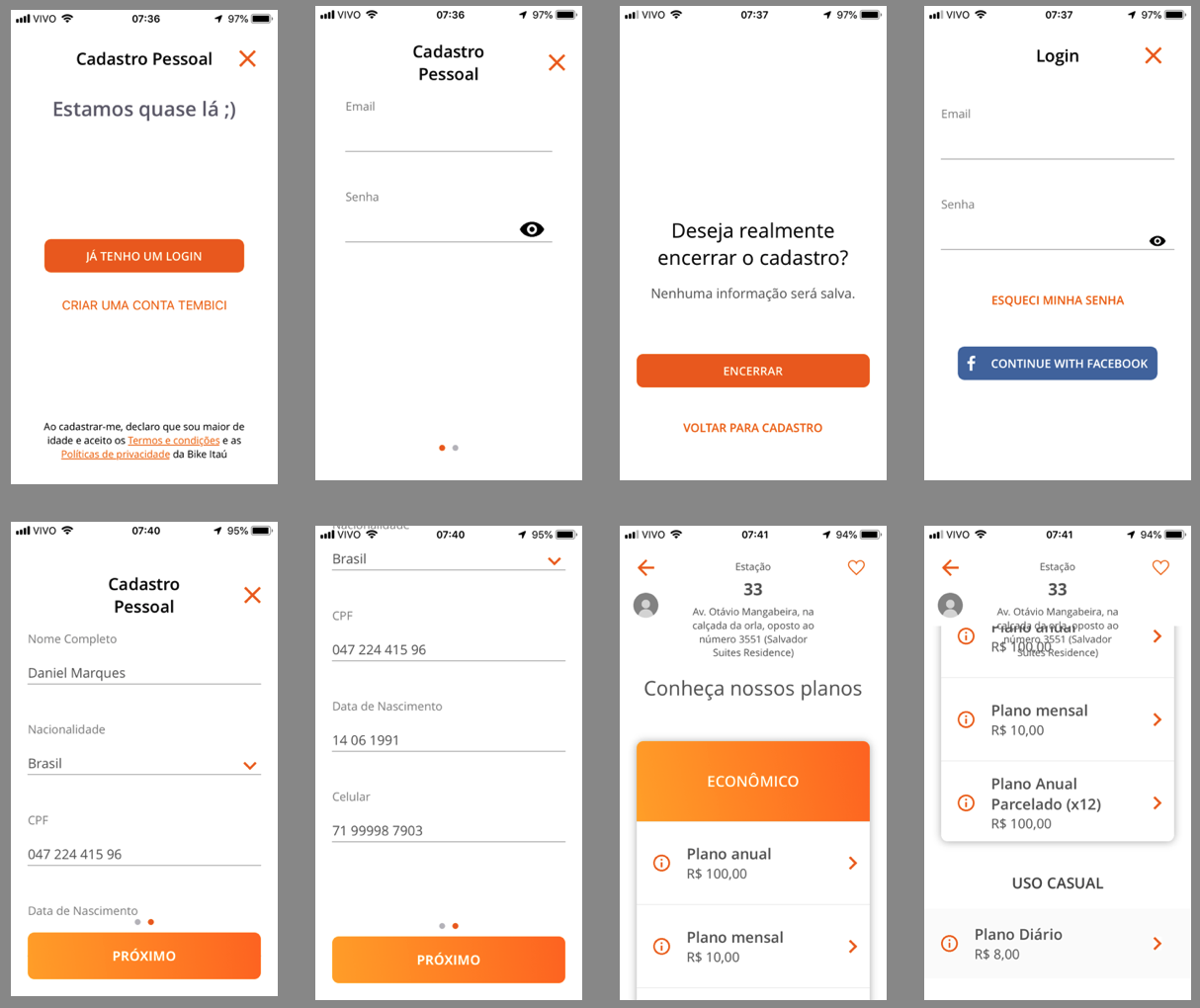

O exemplo a seguir mostra como a análise foi feita para todos os aplicativos. Como é possível visualizar na Figura 4, no Bike Itaú11 o usuário é forçado a se registrar para ter acesso ao serviço (IM - Forced Registration, EG1). É importante destacar que o call to action para realizar o cadastro/login não aparece de imediato. No primeiro acesso, o usuário se depara somente com o mapa contendo as estações disponíveis e as bicicletas. Essa é uma estratégia para estimular a interação livre, sem o desconforto inicial de preencher um formulário. Somente no momento de solicitar a liberação da bicicleta é que o usuário deve realizar um cadastro.

Na quarta tela, o usuário é estimulado a realizar o login a partir da API de cadastro do Facebook (IM - Forced Registration e API Fest). Como há indícios de compartilhamento de dados com terceiros (Facebook), o EG é moderado (2). Na primeira tela temos um exemplo da EG3 (IM - Hidden Legalese Stipulations), pois o consentimento do usuário é solicitado antes da realização do cadastro, alienando o usuário das práticas de dado do Bike Itaú. Esse aplicativo tem os três níveis de ameaça à privacidade do usuário.

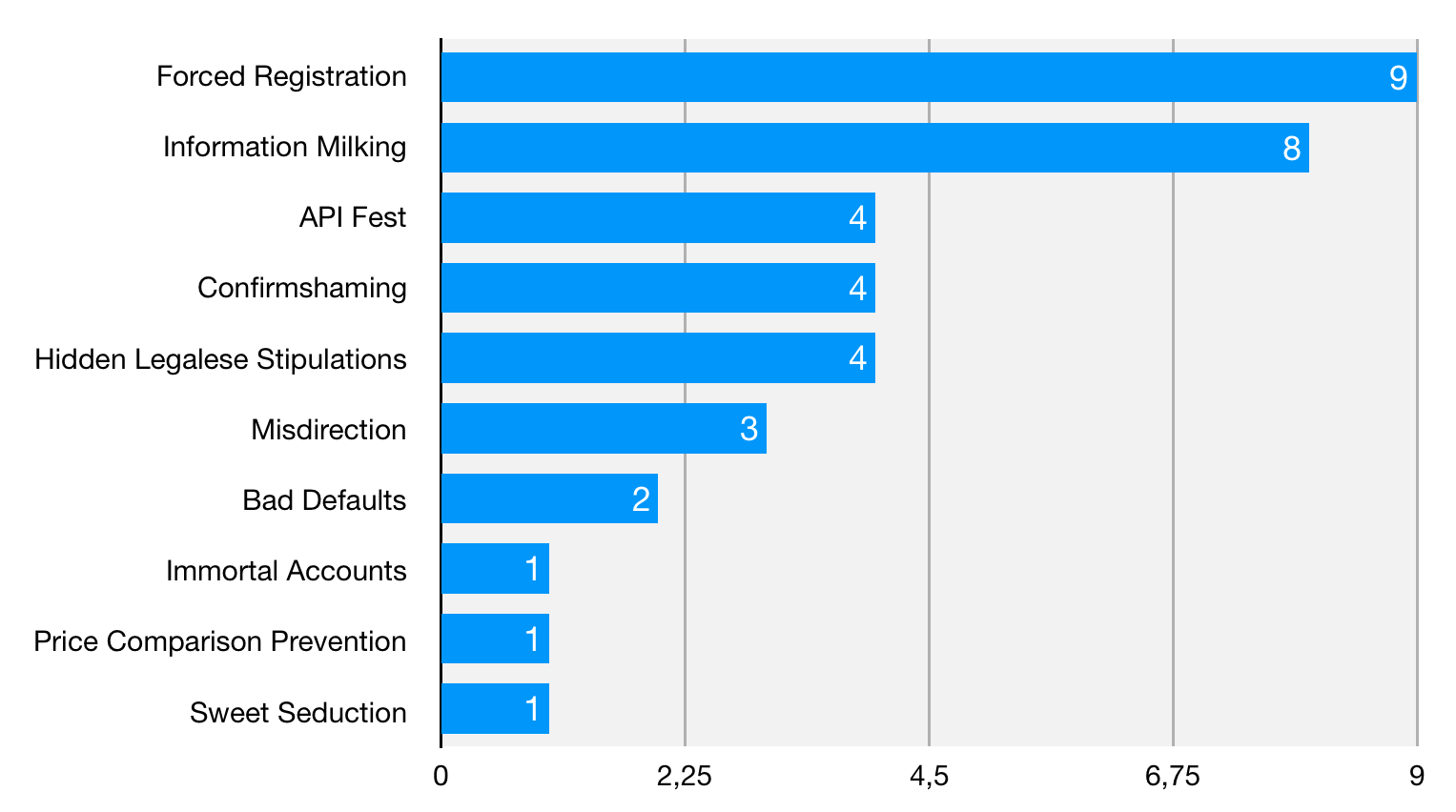

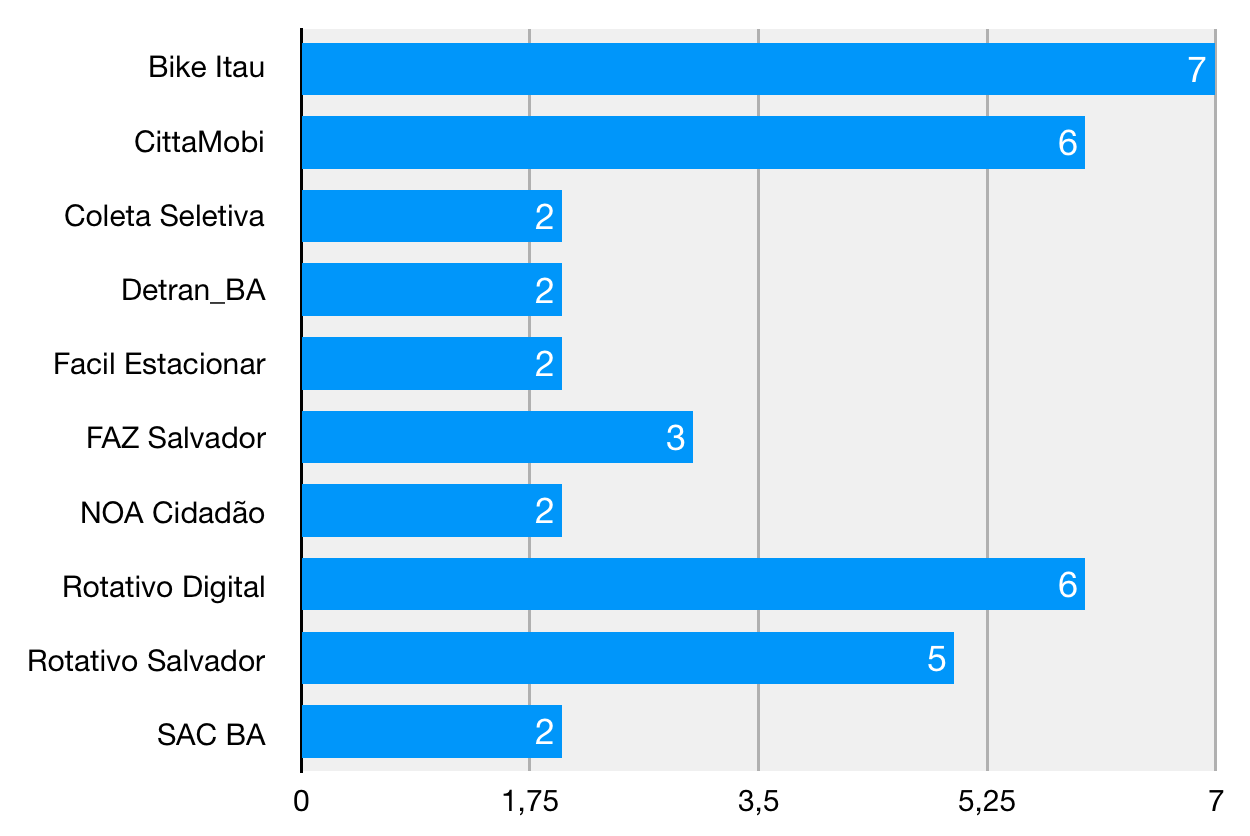

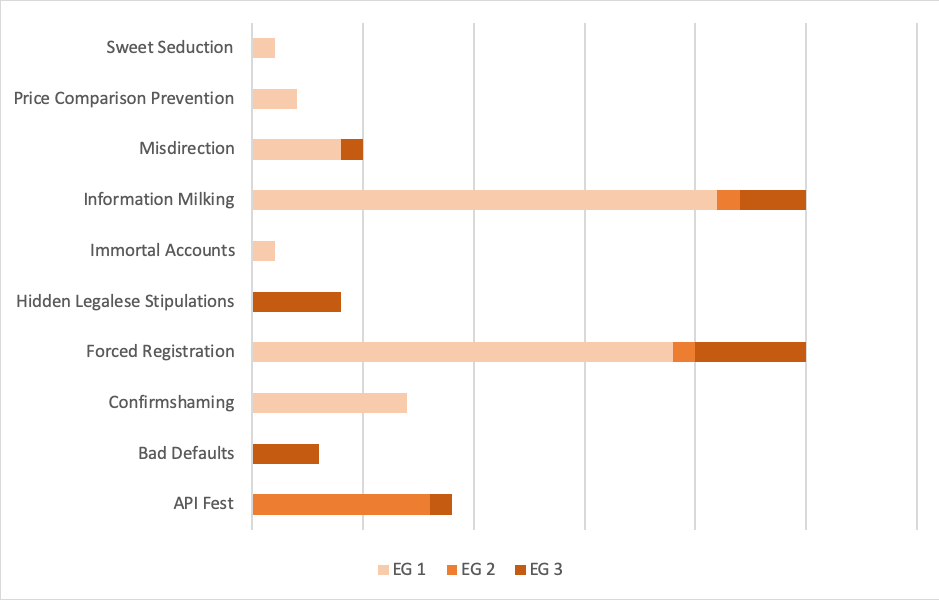

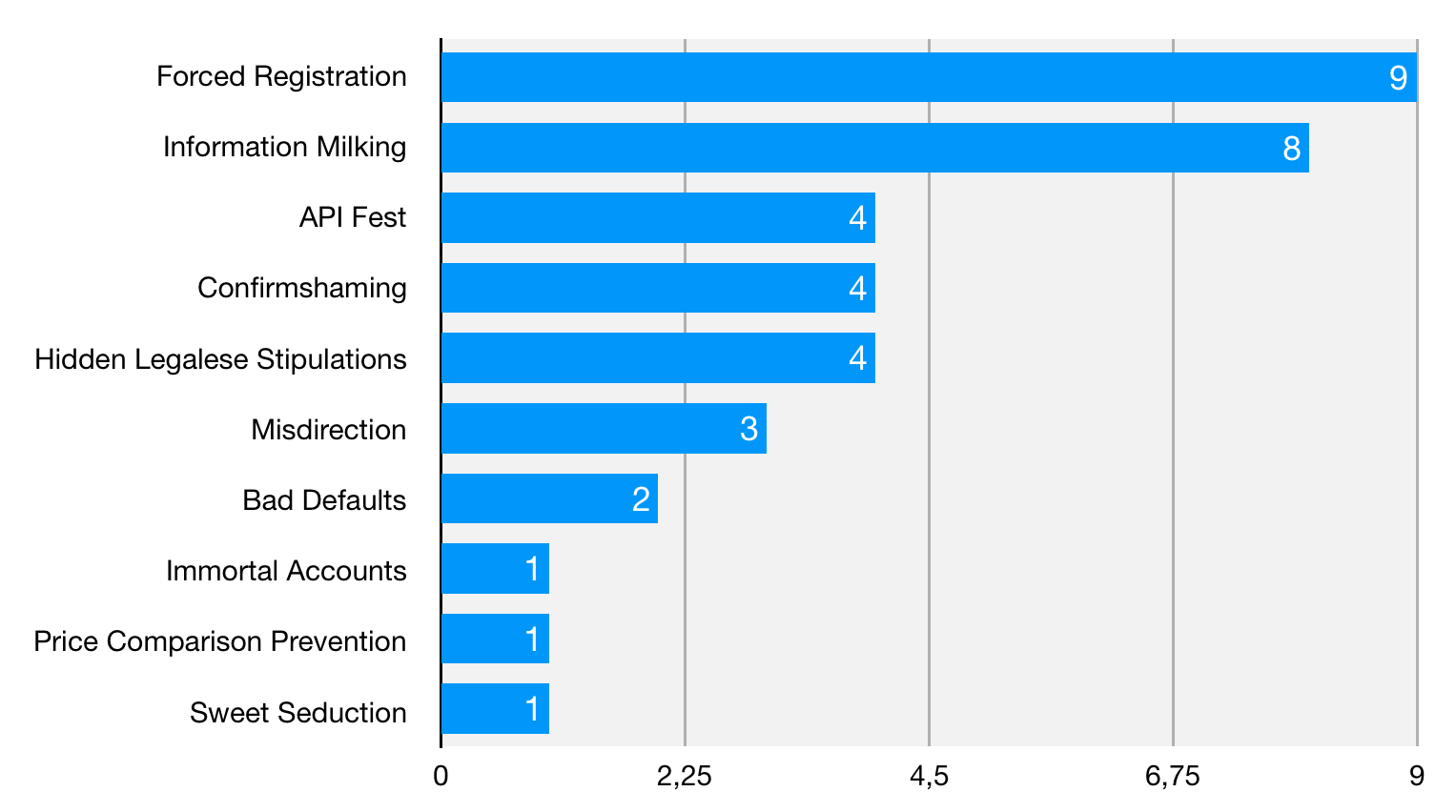

Após análise de todos os aplicativos, dos 21 tipos de IM já catalogados em websites e na literatura especializada12, verificamos a ocorrência de nove e acrescentamos mais um, ausente nessa catalogação, o “API Fest”, totalizando 10 IM. O Gráfico 1 apresenta a ocorrência das IM. Entre todas as IM, as mais comuns são “Forced Registration” (9 ocorrências) e “Information Milking” (8 ocorrências). Forced Registration é a obrigação de cadastramento. Information Milking é a solicitação de informações que não são estritamente necessárias a realização da tarefa. Ambas estão diretamente relacionadas a um processo de maximização da coleta de dados pela constante inserção de dados no sistema e podem, a depender do aplicativo, caracterizar os três níveis de ameaça (como veremos à frente, no Gráfico 1).

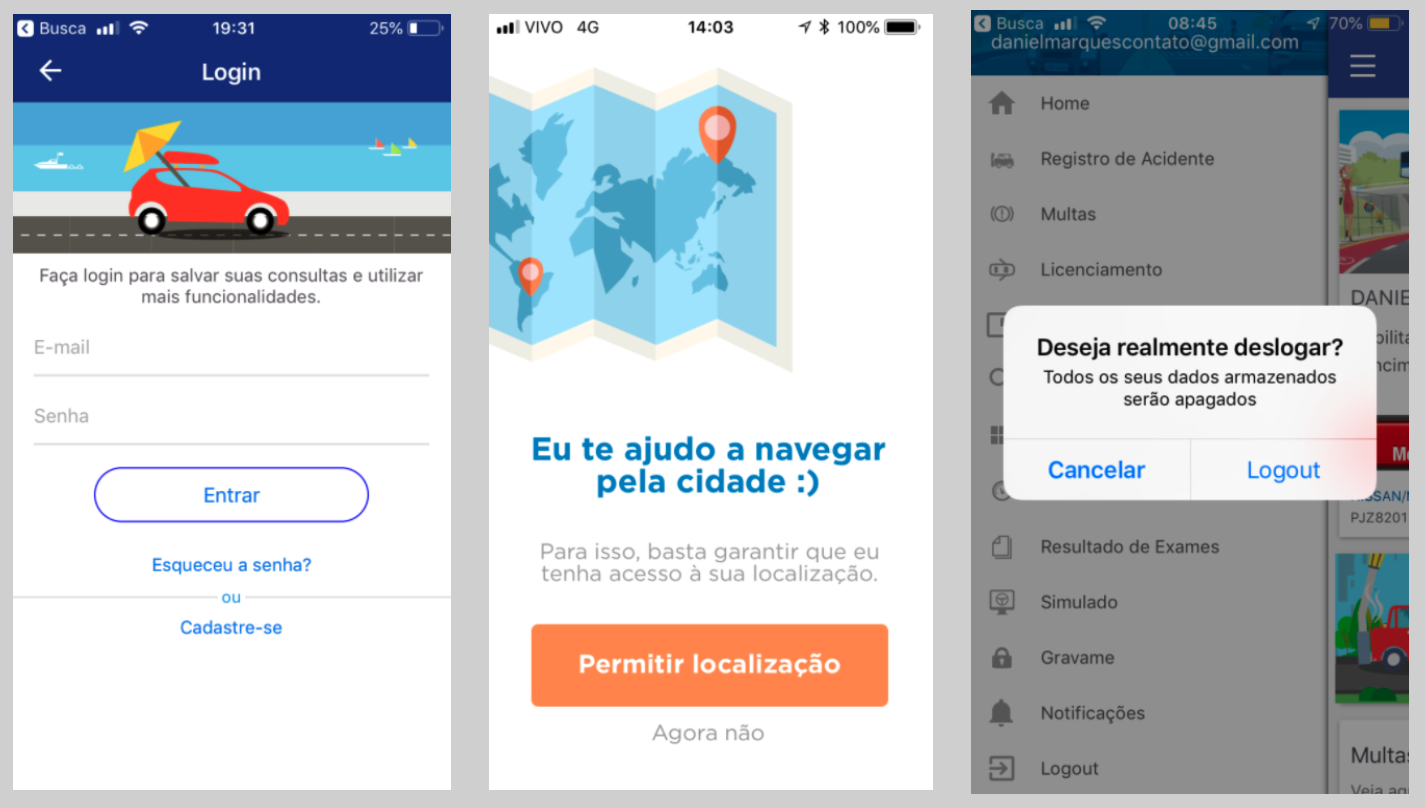

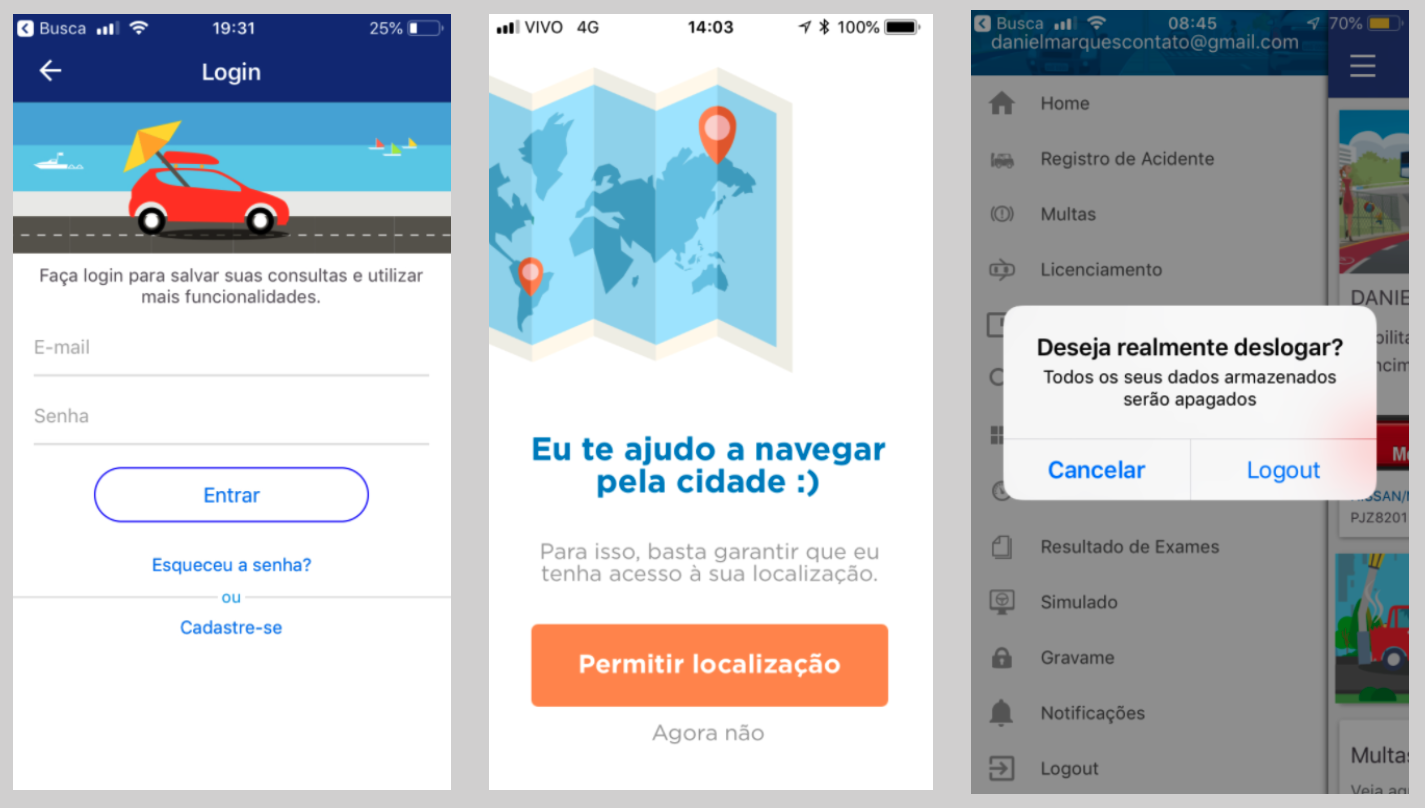

Destaca-se também a presença das IM API Fest, Confirmshaming e Hidden Legalese Stipulations, todas com quatro ocorrências cada uma. Essas IM estão relacionadas de forma direta ou indireta com a ampliação da coleta de dados pessoais e modulação de comportamentos. No primeiro caso (API Fest), é possível verificar que a interface utiliza sistemas de outras plataformas parceiras (Google e Facebook, por exemplo) para realizar a tarefa. A adoção dessas API, entretanto, inclui também a implementação de trackers que enriquecem as bases de dados das plataformas com novas fontes de dados. Confirmshaming é a estratégia discursiva de constrangimento do usuário para ceder o dado ou realizar a tarefa. Trata-se de uma manipulação cujo intuito é fazer com que o usuário se sinta culpado por não cumprir o programa de ação do aplicativo. Essa IM subverte a lógica do consentimento informado, tendo em vista que utiliza de linguagem persuasiva para convencer usuários a optar pela coleta e processamento de informações pessoais (ver gravidade no Gráfico 5). Alguns exemplos de Confirmshaming podem ser visualizados na Figura 5.

A IM Hidden Legalese Stipulations indica formas de ocultação de acesso a informações legais importantes sobre a tarefa realizada. Nesse caso, trata-se de documentos como “Política de Privacidade” e “Termos de Uso”. Como visto no exemplo da Mi Fit, essa IM pode, potencialmente, alienar os usuários acerca das práticas de dado das plataformas, tornando-o domesticado em relação ao programa de ação prescrito.

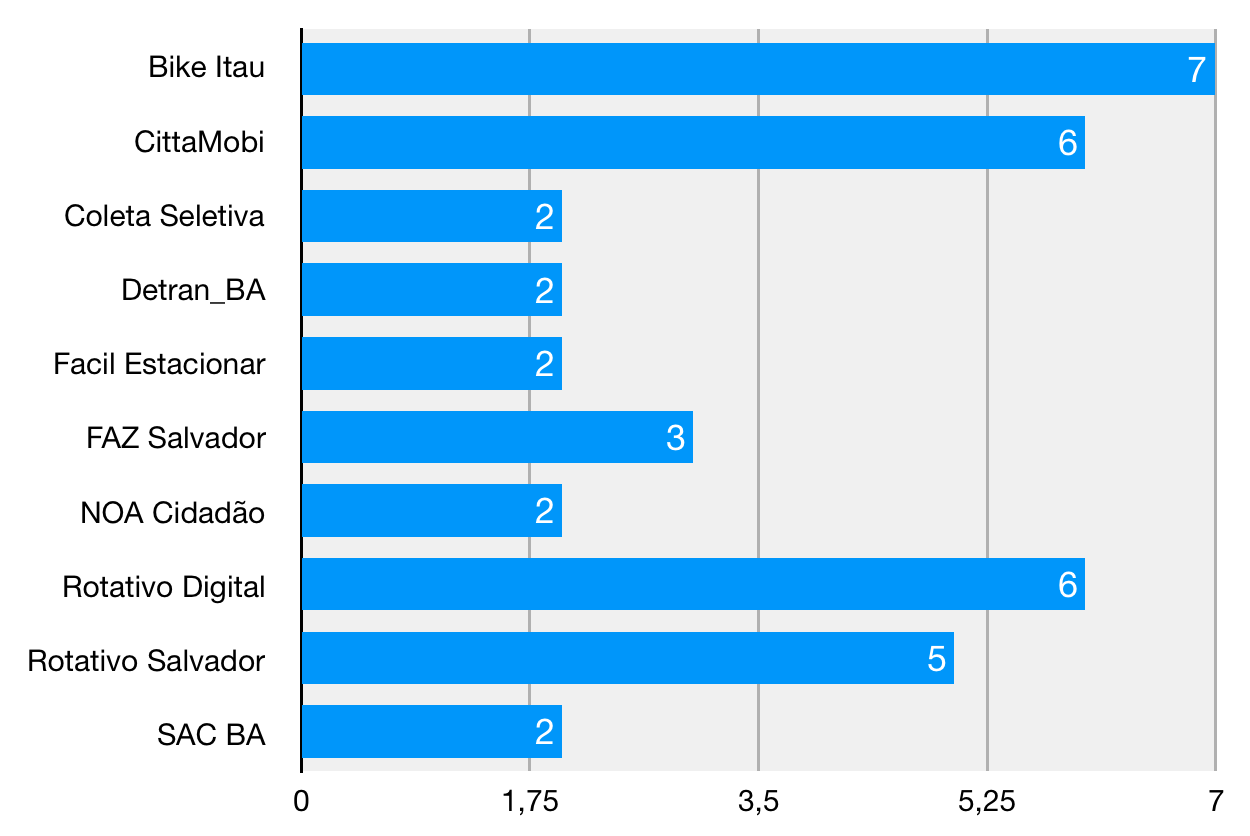

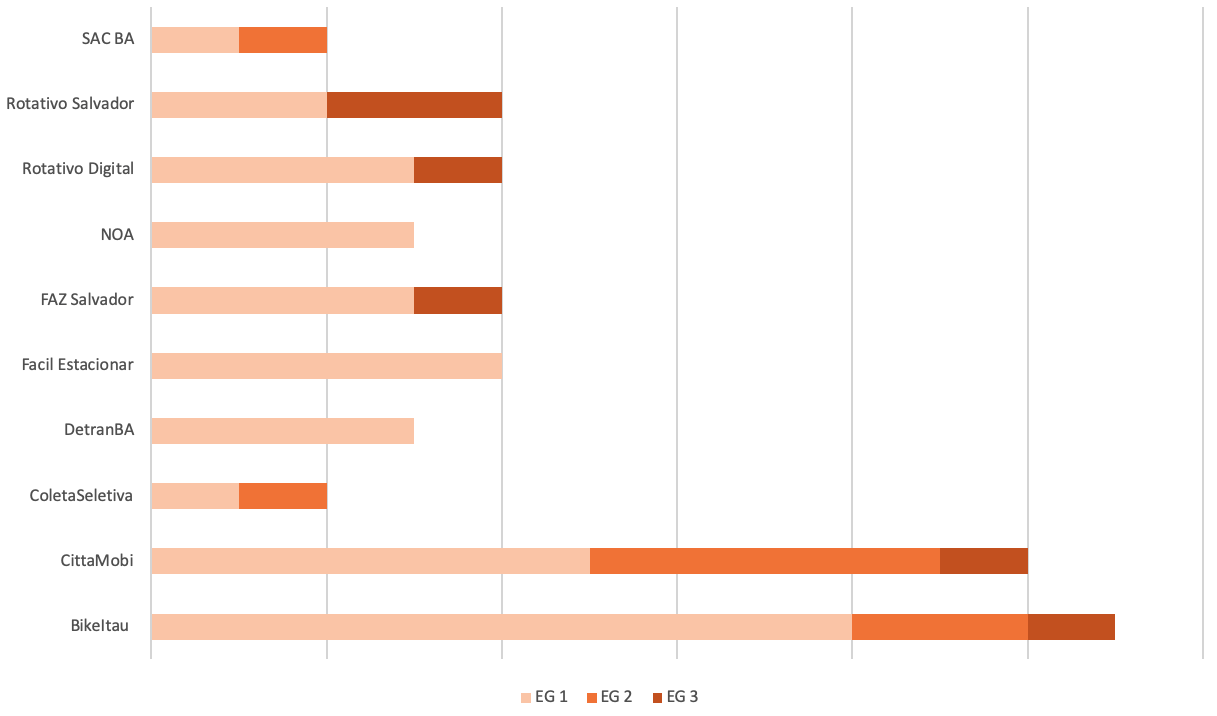

Observando a ocorrência das IM por app, verificamos a maior presença de IM no Bike Itaú (07), CittaMobi (06), Rotativo Digital (06) e Rotativo Salvador (05). Todos esses aplicativos foram desenvolvidos e são operados por empresas privadas. Embora cumpram funções diferentes, estão relacionados a aspectos da mobilidade urbana e lidam majoritariamente com dados de geolocalização. Os resultados podem ser visualizados no Gráfico 2.

Parece esperado que haja um maior empenho por partes de empresas privadas em explorar a retirada de dados pessoais. Os aplicativos mais próximos da administração pública (Coletiva Seletiva, Detran BA, NOA Cidadão e SAC BA) apresentam um número menor de IM. Embora esse dado seja uma pista interessante, faz-se necessário aprofundar essa discussão a partir de um melhor entendimento sobre o contexto de sua produção, bem como sobre os processos atuais de gerenciamento pela máquina pública e/ou iniciativa privada.

Aplicativos de uma mesma categoria podem apresentar IM diferentes, como o caso do Fácil Estacionar, FAZ Salvador, Rotativo Digital e Rotativo Salvador. Todos são credenciados pela Transalvador com o intuito de oferecer venda de créditos para Zona Azul Digital. Não é possível, portanto, atrelar a adoção de determinada estratégia de interação à entrega de uma funcionalidade específica.

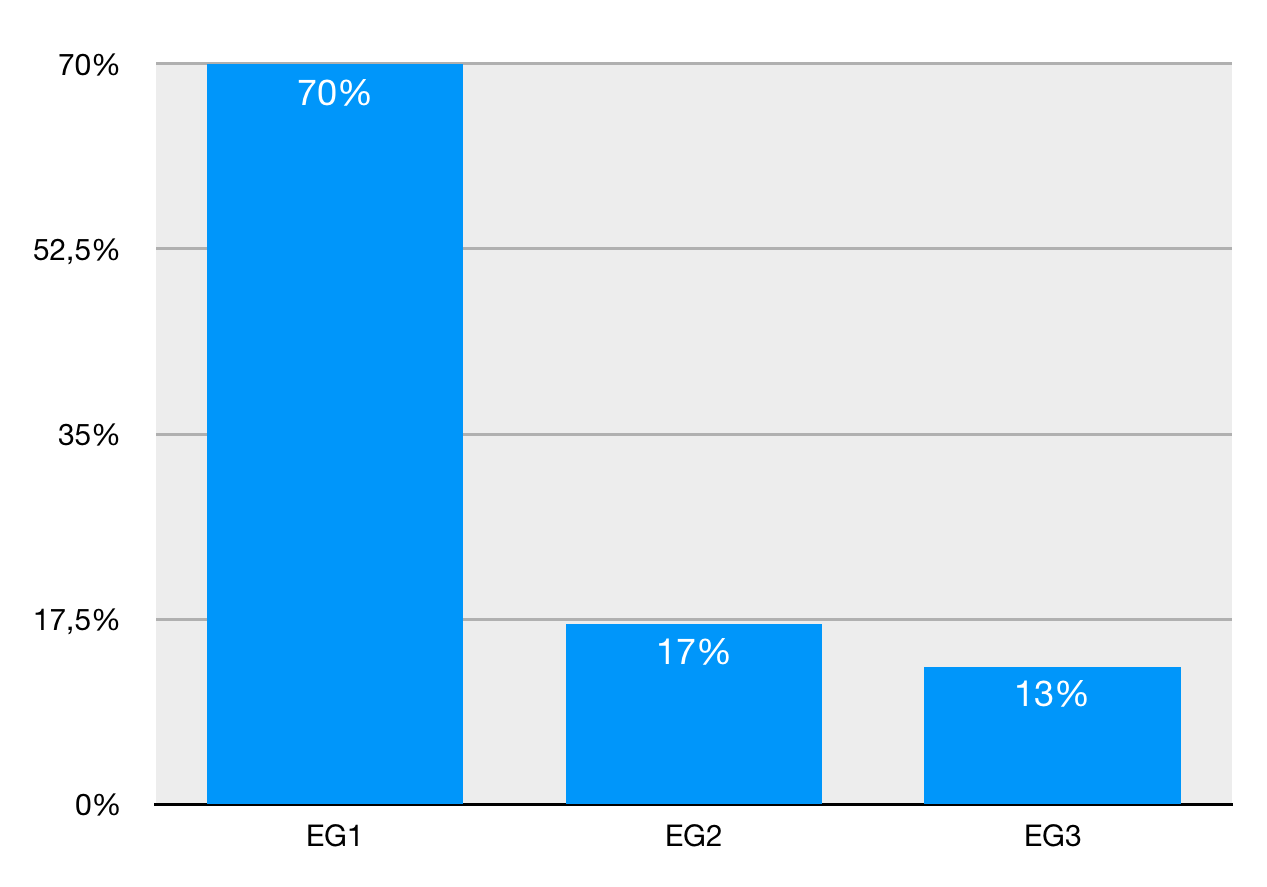

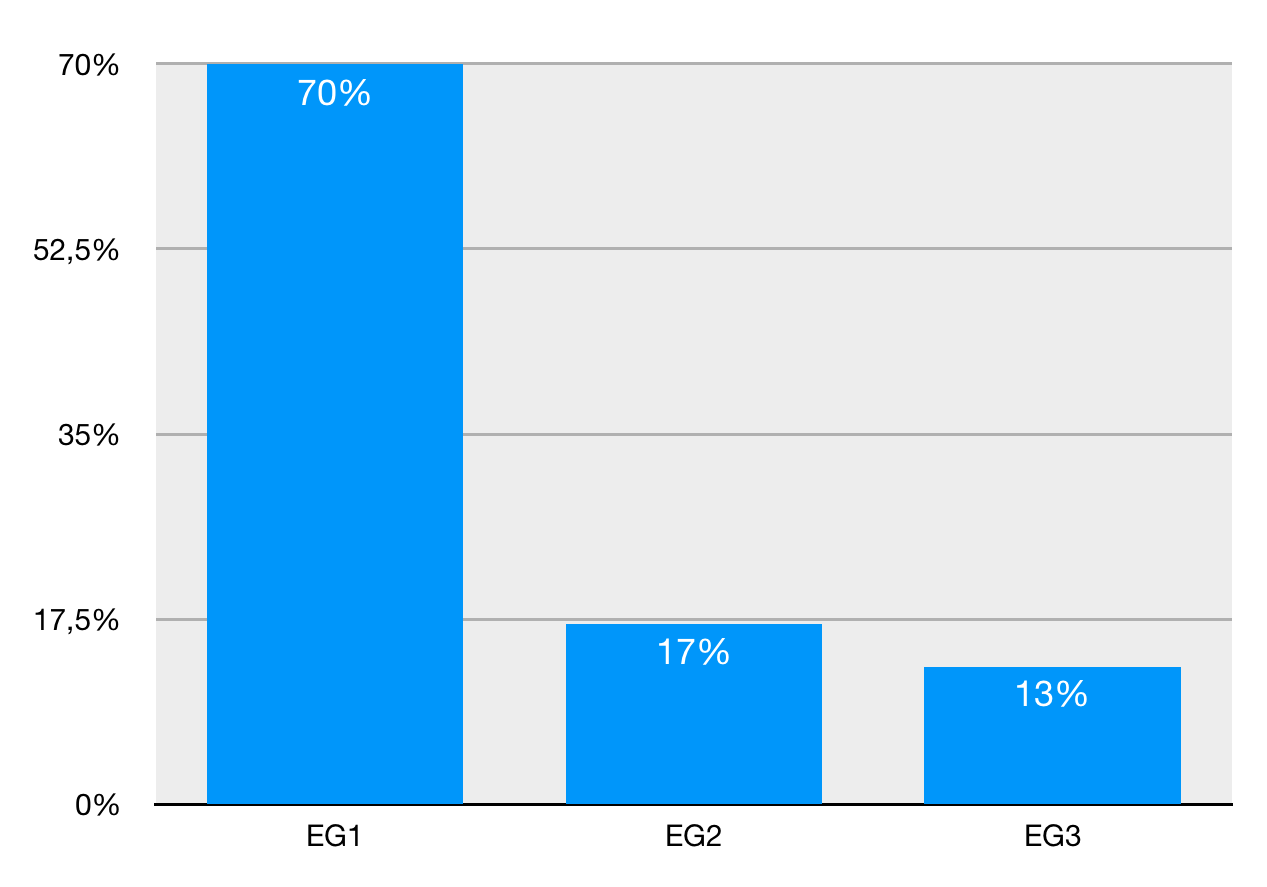

5 Escala de gravidade

Todos os aplicativos analisados contém IM, conforme apresentado no Gráfico 3. Isso corrobora a hipótese de que a IM é uma característica da PDPA. 70% dos aplicativos foram classificados como nível 1 (leve). Os níveis 2 e 3 aparecem em 17% e 13%, respetivamente. Esses dados apontam para uma crescente naturalização e pervasividade da IM13. Essa naturalização pode gerar impactos na forma como entendemos a negociação de dados pessoais com as plataformas, pois à medida que práticas abusivas de interface se tornam lugar comum, os consumidores tendem a abrir mão da sua privacidade mais facilmente.

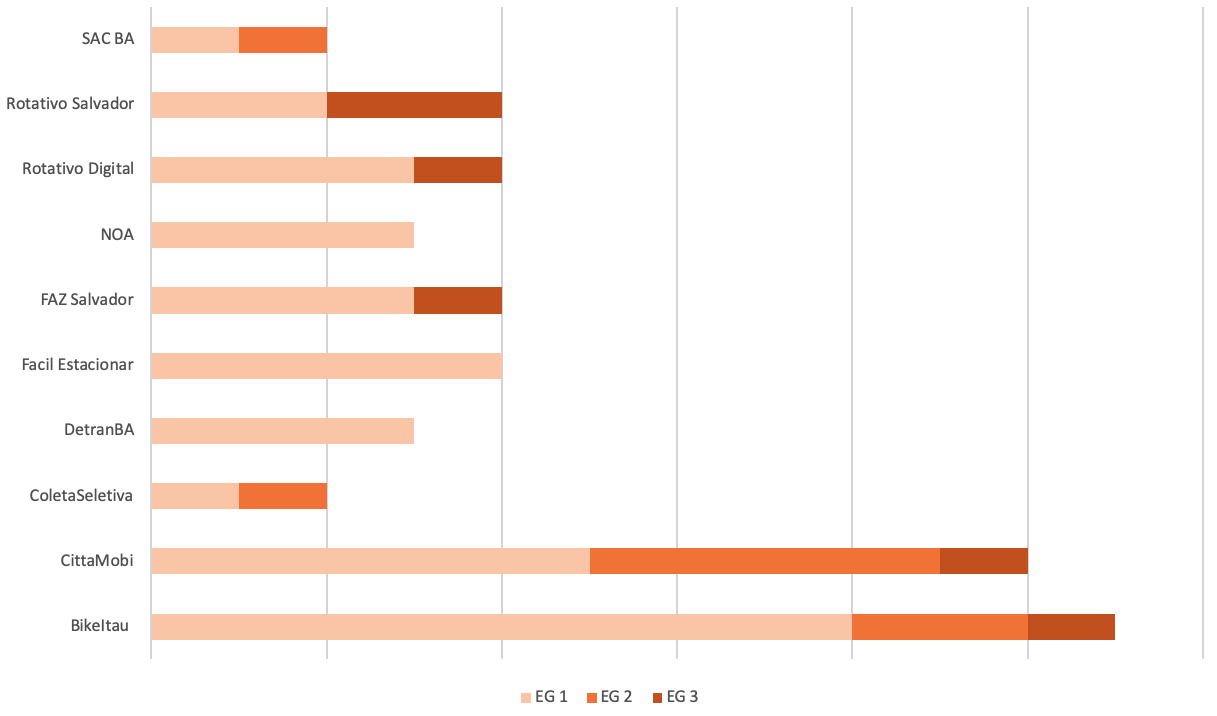

Sobre a distribuição da EG, percebe-se a presença mais significativa de IM classificados como EG2 e EG3 em aplicativos produzidos e administrados pela iniciativa privada. Os casos mais graves são do CittaMobi e do Bike Itaú, nos quais encontramos todos os níveis de EG. Nos dois casos ocorre uma parceria público-privada, na qual as empresas facilitam e gerenciam a oferta de determinado serviço de interesse público. Os outros mais graves são Rotativo Salvador, Rotativo Digital e Faz Salvador, que apresentam os níveis EG1 e EG3. Os resultados detalhados aparecem no Gráfico 4.

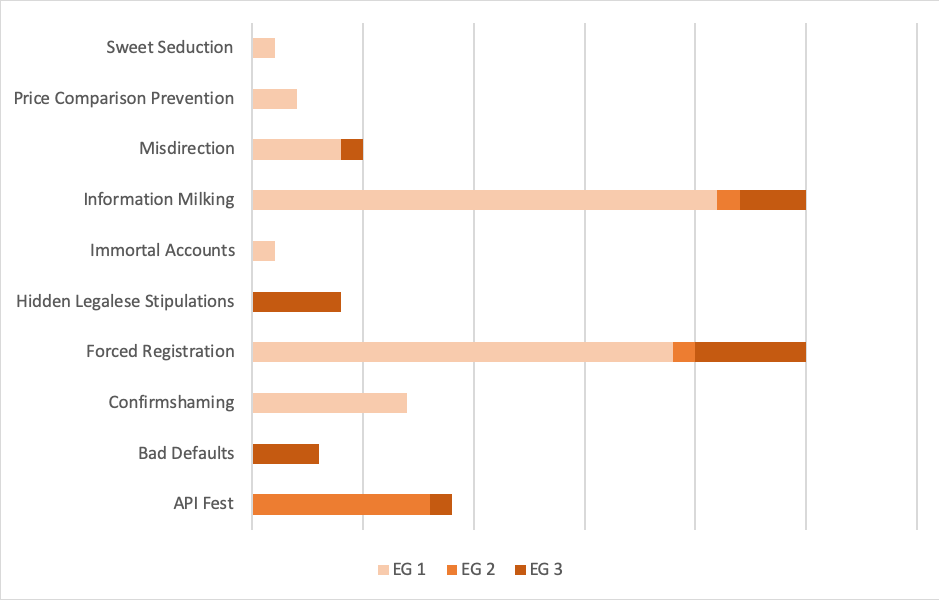

É possível verificar, também, a relação entre as IM e a EG, conforme o Gráfico 5. Das dez categorias de IM encontradas no corpus, quatro se enquadram somente no nível leve (EG1) (Sweet Seduction, Price Comparison Prevention14, Immortal Accounts15 e Confirmshaming), três no nível moderado (EG2) (Information Milking, Forced Registration e API Fest) e seis no nível grave (EG3) (Misdirection16, Information Milking, Hidden Legalese Stipulations, Forced Registration, Bad Defaults e API Fest). Embora apareça em uma variedade maior de IM, verificamos uma ocorrência maior de casos classificados como EG2 (Gráfico 3).

Muitas das IM categorizadas na EG1 reforçam o argumento de sua naturalização, como a base do capitalismo de dados, dando início à cadeia de desenvolvimento de produtos e serviços dataficados. É cada vez mais comum encontrar websites e aplicativos que exigem cadastro de forma obrigatória (Forced Registration) e desenvolvam estratégias diversas para incentivar o usuário a fornecer seus dados (Information Milking e Confirmshaming). No nível EG2, há indícios de compartilhamento de dados com terceiros e os riscos à privacidade tendem a aumentar, gerando processos de perfilização (PONCIANO et al., 2017; SILVEIRA, 2018). Destaca-se, no EG2, a presença da IM API Fest com a utilização de APIs de terceiros, sem que se saiba com muita clareza as práticas de dado da empresa. Sua implementação mais “conservadora” está nos formulários de requisição de dados pessoais no momento do cadastro, conforme vimos anteriormente na Figura 4. É possível verificar outras instâncias de sua ocorrência na Figura 6.

A primeira tela solicita o acesso à geolocalização do usuário, com a promessa de otimizar o serviço e permitir a visualização das estações mais próximas. Na segunda, de forma mais sutil, temos a opção de favoritar uma determinada estação (ver detalhe em verde). Essa ação e a integração com a API do Facebook produzem maior granularidade na coleta de dados, enriquecendo o perfil do usuário e potencializando o valor do dado. Em todos os casos, há requisição de coleta de dados pessoais que não são estritamente essenciais para a realização do serviço e indícios de compartilhamento com terceiros.

6 Conclusão

Esse artigo analisou dez aplicativos em uso de interesse público na cidade de Salvador. Destacamos a discussão sobre a privacidade em meio à expansão da PDPA e o uso das dark patterns (DP), que propomos chamar de interfaces maliciosas (IM). Como mostramos na análise do corpus, todos os aplicativos têm IM, mesmo que em diferentes níveis de gravidade, demonstrando uma tendência a sua naturalização, como um processo de expansão da plataformização da sociedade, do processo de dataficação e do agenciamento performativo dos algoritmos. O crescimento e avanço desses processos – como verificado através da análise das interfaces – aponta para a necessidade de politizar as novas formas de mediação da vida social urbana. Boa parte dos aplicativos analisados buscam atuar no relacionamento entre cidadão e cidade de alguma maneira, mediando e afetando a experiência na urbe. Essa nova sociabilidade urbana, portanto, torna-se alvo das estratégias de coleta e de produção de dados pessoais, tendo em vista seu valor no que tange a cultura digital marcada pela PDPA. Busca-se não só construir a informação como uma nova experiência urbana, mas também domesticar os usuários na prática cotidiana de produção dessas informações, alimentando o capitalismo de vigilância.

A pesquisa partiu de uma perspectiva pragmática e neomaterialista, analisando as ações geradas pela materialidade das interfaces e correlacionando-as à captação de dados sem a devida atenção dos usuários. A fim de criar um mecanismo de comparação e de ajuste dos graus de ameaça à privacidade, propomos a criação de uma Escala de Gravidade (EG) em três níveis (1 - leve, 2 - moderado, 3- grave). Resultante das análises da codificação das IM no ATLAS.ti, chegamos à conclusão de que 70% dos aplicativos estão no grau EG1. Os mais graves são os aplicativos Cittamobi e Bike Itaú, com os três níveis e os Rotativo Salvador, Rotativo Digital e Faz Salvador com os níveis E1 e E3.

A pesquisa aponta para a necessidade de novas etapas que permitirão traçar um quadro mais completo do uso das IM. Análises suplementares de documentos (de licitação do serviço, manual técnico dos aplicativos), conversa com desenvolvedores, survey com usuários, ampliação do corpus empírico, entre outras ações, devem ser realizadas em pesquisas futuras para uma melhor cartografia do problema.

É importante perceber como os diversos atores se posicionam em relação à questão da privacidade estabelecendo assim formas concretas de sua construção e discussão na sociedade digital contemporânea. Algumas questões emergem da pesquisa e apontam para uma discussão política e jurídica. Como a prefeitura, no caso em questão, fez a licitação desses aplicativos? Qual a sua visão da privacidade? Como os usuários foram chamados a participar (se foram)? Como essas plataformas vão se adaptar à LGPDP (Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais)? Que tipo de pressão será exercida pelos usuários, já que são, compulsoriamente, obrigados a usar as plataformas para ações de cidadania?

Referencias

ALEXANDER, C.; ISHIKAWA, S.; SILVERSTEIN, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Nova Iorque: Oxford University Press, 1977.

ASH, J.; ANDERSON, B.; GORDON, R.; LANGLEY, P. Digital interface design and power: Friction, threshold, transition. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, v. 36, n. 6, p. 1136-1153, 2018b. Disponível em: <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0263775818767426>;. Acesso em: 28 jan. 2019.

ASH, J.; ANDERSON, B.; GORDON, R.; LANGLEY, P. Unit, vibration, tone: a post-phenomenological method for researching digital interfaces. Cultural geographies, v. 25, n. 1, p. 165-181, 2018a. Disponível em: <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1474474017726556>;. Acesso em: 28 jan. 2019.

BRIGNULL, H. Dark Patterns: dirty tricks designers use to make people do stuff. 90 Percent of Everything. 2010. [Blog] Disponível em: <https://www.90percentofeverything.com/2010/07/08/dark-patterns-dirty-tricks-designers-use-to-make-people-do-stuff/>;. Acesso em: 28 jan. 2019.

BÖSCH, C.; ERB, B.; KARGL; KOPP, H.; PFATTHEICHER, S.Tales from the Dark Side: Privacy Dark Strategies and Privacy Dark Patterns. Privacy Enhancing Technologies, n. 4, p. 237-254, 2016. Disponível em: <https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/popets.2016.2016.issue-4/popets-2016-0038/popets-2016-0038.xml>;. Acesso em: 28 jan. 2019.

BUCHER, T. The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information Communication and Society, v. 20, n. 1, p. 30-44, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154086>;. Acesso em: 28 jan. 2019.

CHUNG, E. S.; HONG, J. I.; LIN, J.; PRABAKER, M. K.; LANDAY, J. A.; LIU, A. L. Development and evaluation of emerging design patterns for ubiquitous computing. In: CONFERENCE ON DESIGNING INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS PROCESSES, PRACTICES, METHODS, AND TECHNIQUES, 5., 2004, Cambridge. Proceedings ... Nova Iorque: ACM, 2004. p. 233-242. Disponível em: <http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1013115.1013148>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

COLESKY, M.; HOEPMAN, J. H.; HILLEN, C. A Critical Analysis of Privacy Design Strategies. In: IEEE SYMPOSIUM ON SECURITY AND PRIVACY WORKSHOPS, 2016, San Jose. Proceedings... Disponível em: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7527750>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

DANAHER, J. The Threat of Algocracy: Reality, Resistance and Accommodation. Philosophy and Technology, v. 29, n. 3, p. 245-268, 2016.

DIAMANTOPOULOU, V.; KALLONIATIS, C.; GRITZALI, S.; MOURATIDIS, H. Supporting privacy by design using privacy process patterns. In: IFIP INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ICT SYSTEMS SECURITY AND PRIVACY PROTECTION, 2017, Rome. Proceedings... Disponível em: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-58469-0_33>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

DOTY, N.; GUPTA, M. Privacy Design Patterns and Anti-Patterns: Patterns Misapplied and Unintended Consequences. In: SYMPOSIUM ON USABLE PRIVACY AND SECURITY, 9., 2013, Newcastle. Proceedings... Disponível em: <https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2501604>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

FOX, N. J.; ALLDRED, P. Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action. Londres: SAGE Publications, 2017.

FRITSCH, L. Privacy dark patterns in identity management. In: FRITSCH, L.; ROßNAGEL, H.; HüHNLEIN, D. (Eds.). Open Identity Summit 2017. Bonn: Gesellschaft fÜr Informatik, 2013. p. 93-104. Disponível em: <https://dl.gi.de/handle/20.500.12116/3583>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

GRAF, C.; WOLKERSTORFER, P.; GEVEN, A.; TSCHELIGI, M. A Pattern Collection for Privacy Enhancing Technology. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCES OF PERVASIVE PATTERNS AND APPLICATIONS, 2., 2010, Lisboa. Proceedings... Disponível em: <http://www.thinkmind.org/index.php?view=instance&instance=PATTERNS+2010>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

GRAY, C. M.; KOU, Y.; BATTLES, B.; HOGGATT, J.; TOOMBS, A. L. The Dark (Patterns) Side of UX Design. In: CONFERENCE ON HUMAN FACTORS IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS - CHI '18, 2018, Montreal. Proceedings... Montreal: ACM Press, 2018. Disponível em: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=3173574.3174108>;. Acesso em: 30 abr. 2019.

GREENBERG, S.; BORING, S.; VERMEULEN, J.; DOSTAL, J. Dark patterns in proxemic interactions. In: CONFERENCE ON DESIGNING INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS - DIS '14, 2014, Vancouver. Proceedings... Disponível em: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2598510.2598541>;. Acesso em: 30 abr. 2019.

HOEPMAN, J.H. Privacy Design Strategies. In: CUPPENS-BOULAHIA, N.; CUPPENS, F.; JAJODIA, S.; ABOU EL KALAM, A.; SANS, T. (Eds.). ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection: SEC 2014. Berlim: Springer, 2014. p. 446-459. Disponível em: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-55415-5_38>;. Acesso em: 30 abr. 2019.

LACEY, C.; CAUDWELL, C. Cuteness as a 'Dark Pattern' in Home Robots. In: ACM/IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON HUMAN-ROBOT INTERACTION 2019, Daegu-South Korea. Proceedings... Daegu-South Korea: IEEE, 2019. p. 374-381. Disponível em: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8673274/>;. Acesso em: 30 abr. 2019.

LEMOS, A. Epistemologia da Comunicação, Neomaterialismo e Cultura Digital. [no prelo, 2019a]

LEMOS, A. Plataformas, dataficação e performatividade algorítmica (PDPA): Desafios atuais da cibercultura. [no prelo, 2019b.]

LEWIS, C. Irresistible Apps. Berkeley: Apress, 2014.

MATHUR, A.; ACAR, G.; FRIEDMAN, M. J.; LUCHERINI, E.; MAYER, J.; CHETTY, M.; NARAYANAN, A. Dark Patterns at Scale: Findings from a Crawl of 11K Shopping Websites. Proceedings ACM Human-Computer Interaction, v. 1, 2019. Disponível em: <https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.07032>;. Acesso em: 18 Ago. 2019.

MAYER-SCHONBERGER, V.; CUKIER, K. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, And Think. Boston: Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

NODDER, C. Evil by Design: Interaction Design to Lead Us into Temptation. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

PATRICK, A. S.; KENNY, S. From Privacy Legislation to Interface Design: Implementing Information Privacy in Human-Computer Interactions. In: DINGLEDINE R. (Ed.). Privacy Enhancing Technologies - 2003: Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Heidelberg: Springer, 2003. p. 107-124. Disponível em: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-40956-4_8>;. Acesso em: 30 abr. 2019.

PEARSON, S.; SHEN, Y. Context-aware privacy design pattern selection. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON TRUST, PRIVACY AND SECURITY IN DIGITAL BUSINESS, 7., 2010, Bilbao-Spain. Proceedings... Berlim/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2010. p. 69-80. Disponível em: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1894888.1894898>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

PONCIANO, L.; BARBOSA, P.; BRASILEIRO, F.; BRITO, A.; ANDRADE, N. Designing for Pragmatists and Fundamentalists: Privacy Concerns and Attitudes on the Internet of Things. In: BRAZILIAN SYMPOSIUM ON HUMAN FACTORS IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS (IHC'17), 16., 2017, Joinville. Proceedings... Disponível em: <http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05905>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

SADOWSKI, J. When data is capital: Datafication, accumulation, and extraction. Big Data & Society, v. 6, n. 1, p. 1-12, 2019.

SILVEIRA, S. A. Tudo sobre Tod@s: Redes digitais, privacidade e venda de dados pessoais. São Paulo: Edições Sesc SP, 2018.

SRNICEK, N. Platform capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

TRICE, M.; POTTS, L. Building Dark Patterns into Platforms: How GamerGate Perturbed Twitter's User Experience - Present Tense. Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, v. 6, n. 3, p. 1, 2018. Disponível em: <https://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/building-dark-patterns-into-platforms-how-gamergate-perturbed-twitters-user-experience/>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

VAN DIJCK, J.; POELL, T.; DE WAAL, M. The Platform Society. Nova iorque: Oxford University Press, 2018.

WILLIAMS, M.; NURSE, J. R. C.; CREESE, S. The perfect storm: The privacy paradox and the Internet-of-things. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AVAILABILITY, RELIABILITY AND SECURITY, 11., 2016, Salzburg-Áustria. Proceedings... Disponível em: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7784629>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

ZAGAL, J. P.; BJÖRK, S.; LEWIS, C. Dark Patterns in the Design of Games. In: FDG 2013 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE FOUNDATIONS OF DIGITAL GAMES, 8., 2013, Chania-Grácia. Proceedings... Disponível em: <http://www.fdg2013.org/program/papers.html>;. Acesso em: 12 jul. 2018.

ZUBOFF, S. Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, v. 30, n. 1, p. 75-89, 2015.

1 Disponível em: youtube.com/watch?v=zaubGV2OG5U

2 A instrumentalização dos padrões de design foi postulada pelo arquiteto Christopher Alexander (1977) para criar uma linguagem universal para a arquitetura. A popularização do seu trabalho motivou outros campos, como a engenharia de software e o design de interação.

3 Disponível em: ft.com/content/e24dea0a-6b57-11e9-80c7-60ee53e6681d.

5 Disponível em: nytimes.com/2016/05/15/technology/personaltech/when-websites-wont-take-no-for-an-answer.html.

6 Disponível em: theverge.com/2013/8/29/4640308/dark-patterns-inside-the-interfaces-designed-to-trick-you.

7 Disponível em: https://www.darkpatterns.org/types-of-dark-pattern.

8 Acrônimo para os Big Five: Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple e Microsoft.

9 Disponível em: https://bikeitau.com.br/bikesalvador/politica-de-privacidade/.

10 As telas foram capturas e importadas para o software. Não há isonomia na quantidade de capturas. A codificação focada identificou as IM. Nem todas as IM descritas pela literatura dizem respeito a problemas de privacidade, consequentemente, nem todas aparecem no corpus.

11 Parceria entre a Prefeitura Municipal de Salvador e o banco Itaú. Os usuários podem utilizar 400 bicicletas espalhadas por 50 estações. Ele é um mediador para realizar pagamento do serviço (planos diários, mensais e anuais), localizar a estação mais próxima e efetivar o empréstimo da bicicleta.

12 Podemos encontrar exemplos em diversas fontes, como o site oficial de Brignull (darkpatterns.org/hall-of-shame), perfil do projeto no Twitter (twitter.com/darkpatterns), comunidade desenvolvida por pesquisadores (dark.privacypatterns.eu), comunidades no Reddit dedicadas ao tema (reddit.com/r/darkpatterns/) (reddit.com/r/assholedesign/). Alguns outros artigos contribuíram para a expansão do catálogo de IM, como Bosch, et al. (2016) e Gray, et al. (2018).

13 Estudos recentes corroboram essa afirmação. Arunesh Mathur, et al. (2019) demonstraram a presença de IM em 11,1% de aproximadamente 11.000 websites de compra online analisados. A análise revelou a ação de serviços online que oferecem a implementação de IM em sites de compra, no formato de plugins e add-ons. Esses serviços são divulgados abertamente como formas de impulsionar as vendas.

14 Estratégias de interação que dificultem a realização de comparações de preço por parte dos consumidores. Embora seja mais comum em cenários de e-commerce, verificamos a presença de Price Comparison Prevention em apps presentes no corpus desta pesquisa que lidam com a venda de pacotes de serviços.

15 O usuário é impedido de encerrar o serviço contratado ou cancelar sua conta em determinado app ou website. Empresas tendem a impor obstáculos para que os usuários mantenham seus dados atrelados à plataforma.

16 O objetivo desta IM é desviar a atenção do usuário de aspectos da interface que não são do interesse da empresa, ou direcionar o olhar ou ação para a realização da tarefa prescrita no programa de ação.

Malicious interfaces: collection of personal data in apps

André Lemos is a Mechanical Engineer and Ph.D. of Sociology. He is a Full Professor at the Department of Communication, and the Graduate Program in Contemporary Communication and Culture at the Federal University of Bahia, where he coordinates Lab404 - Research Laboratory in Digital Media, Networks and Space. He works in the areas of communication and sociology, in particular on digital culture or cyberculture. He is a member of the Steering Committee of the Brazilian National Institute of Science and Technology in Digital Democracy.

Daniel Marques holds a Bachelor's degree of Design and a Master's degree in Contemporary Communication and Culture. He is an Assistant Professor at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia, Brazil, and a researcher at Lab404- Research Laboratory in Digital Media, Networks and Space, at the Federal University of Bahia. He studies Design, Innovation and Culture, Data Visualization and Mapping Art, Culture, Communication, and Language Systems.

How to quote this text: Lemos, A. and Marques, D., 2019. Malicious Interfaces: strategies for personal data collection in apps.Translated from Portuguese by Colin Richard Bowles. V!rus, Sao Carlos, 19. [e-journal]. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus19/?sec=4&item=2&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON AUGUST 18, 2019

Abstract

This paper analyzes malicious interfaces (MIs) (dark patterns) in ten apps used by the municipality of Salvador to collect personal data. By mediating different aspects of urban social life, these apps contribute to the construction of the contemporary city and the way it is experienced. This new informational dimension of the city, in turn, poses challenges for citizens’ privacy as it fosters the production and collection of as much sensitive personal data as possible. We evaluated the app interfaces with a severity scale (SS) in order to identify the different types of MIs and the level of threat they pose to users’ privacy. All the analyzed apps have MIs, most of which are level 1 (minor), and there is a tendency for these to become increasingly commonplace. The MIs in the apps are part of the increasing platformization and datafication of society and the performative agency of algorithms (PDPA).

Keywords: Dark patterns, Apps, Privacy, Salvador

1 Introduction

The production of social life in the contemporary digital city increasingly overlaps with digital information and communication technologies. Smartphones, virtual assistants, apps, algorithms and social networks, for example, now occupy a significant space in the social fabric and mediate relations of sociability, affect, work, education and leisure. The spread of these mediations takes the idea of an “informational society” to an extreme level, given the central role of the production of information—and its access to increasing amounts of data—in generating value for so-called platform/surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2015).

Data has become the new commodity in contemporary capitalism, and citizens and the city have become sources of this commodity. As the value of data increases and becomes more apparent, we begin to see a more significant effort by multiple institutions, whether private or public, to collect and extract value from this information, jeopardizing people’s privacy in the process. Given that the production and collection of data is the main objective of surveillance capitalism, there is a raised awareness of strategies and mediations used to domesticate citizens to produce more and more data. Data capitalism involves the “construction of information”, putting the privacy of citizens in urban space at risk.

Therefore, this article seeks to discuss what has become known as dark patterns (DPs), namely interfaces that lead users to perform certain actions intended to achieve a variety of purposes. One of such purposes is to collect personal data, which may not be essential to the service initially provided by the app. This collection of data constitutes datafication for commercial or technical purposes. DPs pose a threat to privacy because they persuade users to perform actions that result in personal data capture. Our interest in this subject arose from criticism of these threats found in apps and websites (Ash et al., 2018a, 2018b). We analyze ten apps used by Salvador City Hall. The approach adopted for analyzing these DPs is from a neomaterialist, pragmatic perspective (Fox, Alldred, 2017; Lemos, 2019a). We use a three-level severity scale (SS) to analyze, describe and compare the interfaces. Building upon the original dark patterns framework, we argue in favour of naming these strategies “malicious interfaces” (MIs).

2 Malicious interfaces

The term dark pattern (DP) was proposed by Harry Brignull, a cognitive psychologist who works with user interaction (UI) and user experience (UX) design, in a lecture at UX Brighton in 20101. DPs are design strategies used in digital interfaces (sites, apps, wearables, etc.) and have their origins in the tradition of design patterns2. The term, which has gained popularity, has been adopted by academics and professionals in the fields of design and computing, and the issue of DPs has been the subject of recent articles in the Financial Times3, Gizmodo4, The New York Times5 and The Verge6.

For Brignull (2010), DPs are not merely bad designs. They are anti-patterns, created to trick the user into performing actions of interest to the app/company either unwittingly or because there is no way to avoid them. Unlike bad designs, DPs are characterized by an obscure intention and are developed to achieve specific results without the need to provide any explanations to the user. As he puts it, “this is the dark side of design, and since this kind of design patterns don’t have a name, I’m proposing we start calling them Dark Patterns” (Brignull, 2010). These strategies are based on the exploitation of users’ cognitive and psychological attributes, so the users do not notice that their behavior is subjected to the agency of the platform. Brignull proposed an initial taxonomy of DPs and catalogued 11 different species7, a number that subsequently increased as new papers were published.

We propose to change the term "dark patterns" by "malicious interfaces" (MIs). In this article, we discuss MIs in the use of personal data issues and threats to privacy. The development of MIs to maximize the production, collection and processing of personal data is part of a broader context: the PDAP culture (Lemos, 2019a, 2019b), that is, the platformization of society (Van Dijck; Poell; De Waal, 2018), datafication (Mayer-Schonberger; Cukier, 2013) and algorithmic performativity (Bucher, 2017; Danaher, 2016).

PDAP is the phenomena that characterize the current state of digital culture and illustrate how digital platforms are playing an expanding role in the mediation of everyday life. The platformization of society in this sense refers to the growing presence of digital platforms—generally products and services associated with GAFAM8 —in the mediation and realization of social life. This mediation occurs mainly through the action of performative algorithmic systems, which, as key elements in the design of platforms, have an impact on the organization of social life. As PDAP is developing at the same time as data (or surveillance) capitalism is expanding (Srnicek, 2017; Zuboff, 2015), personal data are considered the principal commodity (Sadowski, 2019) given the need to “datafy” social life, i.e., maximize production, collection and processing of this commodity. The term PDAP refers to the integration of these phenomena: digital platforms which act and materialize through the implementation of performative algorithms and different processes that collect personal data (datafication).

Since 2010, the literature on MIs has become more diverse and now covers areas and subjects such as game design (Zagal, Björk, Lewis, 2013), proxemic interaction technologies (Greenberg et al., 2014), the violation of privacy and maximization of datafication processes (Bösch et al., 2016; Doty, Gupta, 2013; Fritsch, 2017), ethical implications (Gray et al., 2018), activism in digital platforms (Trice, Potts, 2018) and physical and voice interfaces (Lacey, Caudwell, 2019). And, as some authors have noted, developers are using MIs as a competitive strategy (Lewis, 2014; Nodder, 2013).

We highlight four central issues found in the current literature on the subject: (a) the problem of intentionality; (b) the focus on the observation of micro-interactions; (c) ethical aspects; (d) psychological factors. The problem of intentionality is the most widely discussed issue, and much of the literature acknowledges that MIs are implemented by companies as deliberate strategies. The focus of the present study was, therefore, to consider what the intentions that lie behind the MIs used in the apps analyzed here might be. From a pragmatic perspective, as we have adopted here, it seems somewhat subjective to declare that intentionality is present; instead, it would be more productive to analyze the concrete effects of MIs. MIs comply with the letter but not the spirit of the prevailing legislation (Doty, Gupta, 2013), and usually, the user is not aware of the agency to which she or he is being subjected.

Psychological and subjective factors vary from user to user, and they also come into play (Bösch et al., 2016, Zagal et al., 2013). The user’s understanding undoubtedly has a role in this process, but it is not the only factor in the same way as noticing a malicious strategy is not sufficient to avoid interaction. In many cases negotiation is not possible, and the only alternative is to opt-out. For Bosch et al. (2016), MIs affect users regardless of their level of literacy because of our increasing dependence on apps. It is almost impossible to live nowadays in Western capitalist societies without the services offered by GAFAM.

Many people now experience the “privacy paradox” (Williams, Nurse, Creese, 2016). When assessing whether it is worthwhile releasing personal data in exchange for goods and services, users concerned with privacy end up giving in. This paradox becomes more complex as users are rarely able to determine what their data are worth and the consequences of supplying them to someone else. The asymmetry between the power wielded by platforms and users’ limited ability to negotiate leads to a process in which MIs are becoming increasingly common as the hegemonic paradigm of interaction design. The existence of literature that encourages and offers support for the implementation of MIs corroborate this fact (Lewis, 2014, Nodder, 2013).

We shall consider two examples of MIs before we take a more detailed look at our empirical corpus: the Mi Fit and Bike Itaú apps.

Mi Fit use smart bands made by the Chinese company Xiaomi. In this app, it is challenging to verify relevant documents such as the User Agreement and Privacy Policies, as shown in Figure 1. In the Settings screen there is no indication that User Agreement and Privacy Policies are in the About section. In addition to this, even if the user manages to find the documents, no efforts have been made to adapt the long, complicated legal text to make it readable on a smartphone screen. These documents are compulsory, and including them is considered good privacy practice (Colesky, Hoepman, Hillen, 2016; Hoepman, 2012; Patrick, Kenny, 2003). The user must give his consent even though it is difficult to locate these documents to use this app. The alienation in the app is materialized in the MI. As with all MIs, this MI is produced in an asymmetric negotiating space (Ash, 2018b). The immediate effect is that users become more lenient about data collection by Xiaomi.

Furthermore, a MI frequently found in apps is Confirmshaming, a discursive strategy intended to shame the user into giving up data. In the Bike Itaú example in Figure 2, the first screen asks for real-time access to the user’s location while the second encourages the user to complete registration, telling him that the data will be collected “only to show the locations nearest to you where bikes can be collected and returned.” Ironically, the privacy policy9 states that the data collected can be shared with third parties explicitly. In the second screen, the tone of the text is punitive as it informs the user that leaving the registration process will result in more work in the future as the information will not be saved.

3 Methodology

In light of the scenario described above, we sought to identify whether the ten apps shown in Table 1 contain MIs and represent a threat to privacy. The apps, which were developed by private and state companies, were chosen because they offered services of interest to the general public in the capital of the state of Bahia. Apps intended for niche users, such as government employees, were excluded. The main screens of each app (the screens that ask the user to provide some type of personal data, both in a formal request—e.g., forms, registration, consent requests—and through interaction with the functionality of the app) were analyzed using ATLAS.ti10. An average of 8.1 screens was analyzed for each app. The apps with the most and fewest screens analyzed were Bike Itaú (15) and SAC BA (4), respectively.

After the MIs had been coded for the first time, we created different levels of privacy threats on a severity scale (SS), as required by the comparative analysis. We used the following SS: 1 - minor; 2 – moderate; and 3 - severe. Level 1 corresponds to MIs that require the collection of personal data that are not needed for the task in question but have some connection with the functionality of the app. Level 2 corresponds to MIs that allow personal data to be shared with third parties; the data requested are in one way or another directly connected with the purpose of the service. Level 3 corresponds to MIs that collect data that are irrelevant to the task in hand and share them with third parties while keeping the user unaware of, or alienated from, the data collection process. An app can be level 3 without being levels 1 or 2; level 2 without being levels 1 or 3; and level 1 without being levels 2 or 3. The classification scheme is shown in Figure 3.

4 Distribution of MIs by app

The following example illustrates how we performed the analysis for all the apps. As shown in Figure 4, in Bike Itaú,11 the user is forced to register to gain access to the service (MI – Forced Registration, SS1). We highlight that the call to action to register/login does not appear immediately. At the first time accessing the app, the user only sees the map with stations and bicycles available. This strategy encourages the user to interact freely with the app without the initial inconvenience of filling out a form. The users have to register only when they ask to release and use the bike.

On the fourth screen, the user is encouraged to log in using a Facebook registration API (MI – Forced Registration and API Fest). We evaluate this as moderate (2) SS since there are signs that the app shares data with third parties (Facebook). On the first screen, as shown above, we have an example of SS3 (MI – Hidden Legalese Stipulations), since the user’s consent is requested before registration and information about the Itaú’s data practices, alienating the user from its content. Thus, this app exhibits three levels of threat to users’ privacy.

After analysis, we found 9 of the 21 types of MI already catalogued in websites and the specialized literature12 as well as a different kind of MI not previously listed, API Fest, giving a total of 10 MIs. Graph 1 shows the number of occurrences of each MI in the apps analyzed as a whole. The most common MIs are “Forced Registration” (nine occurrences) and “Information Milking” (eight occurrences). Forced Registration means that the user is obliged to register. Information Milking regards asking for information that is not strictly necessary for the task in question. Both MIs are directly associated with a process of maximizing data collection by constantly inputting data into the system and can, depending on the application, characterize the three levels of threat (as we shall see later on, in Graph 5).

Graph 1: The number of occurrences of the MIs in the apps analyzed as a whole (n = 10 apps analyzed). Source: Lemos, Marques, 2019.

We observed API Fest, Confirmshaming and Hidden Legalese Stipulations for four times, so these MIs are also worthy of notification. These MIs directly or indirectly involve expanding the collection of personal data and modulation of behavior. In the first case (API Fest), the interface uses systems from other partners’ platforms (Google and Facebook, for example) to perform the task. When these APIs are adopted, however, trackers adding new data sources to the platforms’ databases are also implemented. Confirmshaming is a discursive strategy used to embarrass the user into giving information or performing a task. It involves manipulating the user to make him feel guilty if he does not do what the app asks him to. This MI subverts the logic of informed consent as it uses persuasive language to convince users to allow their personal information to be collected and processed (see severity in Graph 5). The Figure 5 shows some examples of Confirmshaming.

The Hidden Legalese Stipulations MI involves hiding access to essential legal information about the performed task. In the present case, we consider documents such as Privacy Policy and Terms of Use as legal information. As seen in the Mi Fit example, this MI potentially may result in alienating the user from these documents. The alienation means the user is unaware of the data practices used in the platform, turning him into a tame user willing to follow the steps suggested by the app.

Looking at the number of MIs per app, we can see that Bike Itaú (7), CittaMobi (6), Rotativo Digital (6) and Rotativo Salvador (5) have the most MIs. Private companies developed and operate all these apps. Although they perform different functions, they all involve urban mobility and deal mainly with geolocation data. Graph 2 shows the results.

It seems to be expected that there will be a more significant commitment by private companies to explore the capture of personal data. Accordingly, the apps more closely related to public administration (Coletiva Seletiva, Detran BA, NOA Cidadão and SAC BA) have fewer MIs. Although this is an interesting finding, further discussion of this result would require a better understanding of the context in which the apps were produced and how they are currently managed in the public and private sector.

Apps in the same category can have different MIs, as Fácil Estacionar, FAZ Salvador, Rotativo Digital and Rotativo Salvador. All are registered with Transalvador to sell credits for the Zona Azul Digital. The use of a particular interaction strategy cannot, therefore, be linked to the provision of specific functionality.

5 Severity scale

All analyzed apps contain MIs, as shown in Graph 3, and this fact corroborates the hypothesis that MIs are a characteristic of PDAP. Just over two-thirds of the apps (70%) were classified as level 1 (minor), while 17% and 13%, respectively, were classified as levels 2 and 3. These results suggest that MIs are becoming increasingly common and pervasive13, potentially impacting our attitude to negotiating access to personal data with platforms as the more common abusive interface practices become, the more willing consumers are to relinquish their privacy.

Turning to the distribution of SSs, MIs classified as SS2 and SS3 were more common in apps produced and administered by companies in the private sector. The most severe cases were CittaMobi and Bike Itaú, in which we found all three SS levels. In both cases there is a public-private partnership, in which the companies involved provide and manage a particular service of interest to the public. The other more serious cases were Rotativo, Salvador Digital and Faz Salvador, which had MIs corresponding to levels SS1 and SS3. Graph 4 shows detailed results.

Graph 5 shows the relationship between MIs and SS. In ten categories of MI found in the corpus, four correspond only to SS1 (minor) (Sweet Seduction, Price Comparison Prevention14, Immortal Accounts15 and Confirmshaming), three to SS2 (moderate) (Information Milking, Forced Registration and API Fest) and six to SS3 (severe) (Misdirection16, Information Milking, Hidden Legalese Stipulations, Forced Registration, Bad Defaults and API Fest). Although the MIs corresponding to SS2 tend to vary less, they were present in higher numbers (Graph 3).

Many of the MIs classified as SS1 lend credence to the argument that this type of interface is increasingly forming the basis of data capitalism, leading to the development of a series of datafied products and services. Sites and apps that require the user to register (Forced Registration) and that make use of a variety of strategies to encourage users to give up their personal data (Information Milking and Confirmshaming) are becoming more and more common. At level SS2, there are signs that data are being shared with third parties, leading to profiling, and the threat to privacy tends to increase (Ponciano et al., 2017, Silveira, 2018). Particularly in relation to SS2, we highlight the presence of the API Fest MI and the use of third-party APIs without the user having a clear understanding of the company’s data practices. A more “conservative” implementation of this MI can be seen in the forms requesting personal data when the user registers, as seen previously in Figure 4. Figure 6 shows other instances of API Fest.

The first screen requests access to the user’s geolocation so that the service can be optimized and the nearest stations displayed. On the second screen, in a subtler approach, we can choose to make a particular station a favorite (see detail in green). This step, in addition to the integration with the Facebook API, allows more detailed data to be collected, enriching the user’s profile and enhancing the value of the data. In each case, a request is made to collect data that are not strictly necessary for the provided service, and there are signs of shared data with third parties.

6 Conclusion

In this article we have analyzed ten apps intended for the general public in use in the city of Salvador. We highlight the ongoing discussion on privacy at a time when PDAP and the use of dark patterns are expanding. As we showed in the analysis of the corpus, all the apps contain MIs, albeit with different levels of severity, suggesting a tendency for these patterns to become more and more common as part of the increasing platformization and datafication of society and the performative agency of algorithms. The growth and spread of these processes, as confirmed in the analysis of the MIs, indicates that there is a need to raise awareness of these new forms of mediation of urban social life. Many of the apps analyzed seek in some way to act in the relationship between citizen and city, mediating and affecting our experience in the city. This new urban sociability has, therefore, become a target of new strategies for collecting and producing personal data given its value in a digital culture marked by PDAP. These strategies attempt to construct information as a new urban experience while at the same time domesticating users so that they become accustomed to producing this information daily, thereby feeding surveillance capitalism.

The study adopted a pragmatic, neomaterialist approach in which the actions generated through the materiality of the interfaces were analyzed and correlated with the capture of data without the user being aware of this. To create a mechanism for classifying and comparing the severity of the threat to privacy, we proposed a three-level severity scale (SS) (1-minor, 2-moderate, 3-severe). After analyzing the coding of the MIs in ATLAS.ti, we concluded that 70% of the apps correspond to SS1. The most severe cases are the Cittamobi and Bike Itaú apps, which contain MIs corresponding to all three severity levels, and the Rotativo Salvador, Rotativo Digital and Faz Salvador, which correspond to SS1 and SS3.

The results of the study indicate that further research is required to develop a more comprehensive picture of the use of MIs. Additional analysis of documents (the invitations to tender for the services and the technical manuals for the apps), interviews with developers, user surveys and analysis of a larger empirical corpus, among other things, are essential elements of any future studies to investigate the problem in greater detail.

It is essential to understand the position of the various actors concerning the issue of privacy, and so establish concrete ways of constructing and discussing privacy in contemporary digital society. Several questions that emerged from the study suggest that there is a need to discuss political and legal aspects of the problem. In the particular cases studied here, how did City Hall put these apps out to tender? What is City Hall’s view of privacy? How were users asked to participate (if indeed they were)? Will these platforms comply with the LGPDP (General Personal Data Protection Law)? What type of pressure will be exerted by users as they are obliged to use the platforms in their daily activities as citizens?

References

Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M., 1977. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Nova Iorque: Oxford University Press.

Ash, J.; Anderson, B.; Gordon, R.; Langley, P., 2018b. Digital interface design and power: Friction, threshold, transition. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, v. 36, n. 6, pp. 1136-1153. Available at: <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0263775818767426>. Acessed in: 28 jan. 2019.

Ash, J.; Anderson, B.; Gordon, R.; Langley, P. 2018a. Unit, vibration, tone: a post-phenomenological method for researching digital interfaces. Cultural geographies, v. 25, n. 1, pp. 165–181, Available at: <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1474474017726556>. Acessed in: 28 jan. 2019.

Brignull, H. 2010. Dark Patterns: dirty tricks designers use to make people do stuff. 90 Percent of Everything. [Blog] Available at: <https://www.90percentofeverything.com/2010/07/08/dark-patterns-dirty-tricks-designers-use-to-make-people-do-stuff/>. Accessed in: 28 jan. 2019.

Bösch, C.; Erb, B.; Kargl; Kopp, H.; Pfattheicher, S., 2016. Tales from the Dark Side: Privacy Dark Strategies and Privacy Dark Patterns. Privacy Enhancing Technologies, n. 4, pp. 237-254, Available at: <https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/popets.2016.2016.issue-4/popets-2016-0038/popets-2016-0038.xml>. Accessed in: 28 jan. 2019.

Bucher, T., 2017. The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information Communication and Society, v. 20, n. 1, pp. 30–44. Available at: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154086>. Access in: 28 jan. 2019.

Chung, E. S.; Hong, J. I.; Lin, J.; Prabaker, M. K.; Landay, J. A.; Liu, A. L. 2004. Development and evaluation of emerging design patterns for ubiquitous computing. In: Conference On Designing Interactive Systems Processes, Practices, Methods, And Techniques, 5., Cambridge. Proceedings ... Nova Iorque: ACM, 2004. pp. 233-242. Available at: <http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1013115.1013148>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Colesky, M.; Hoepman, J. H.; Hillen, C., 2016. A Critical Analysis of Privacy Design Strategies. In: Ieee Symposium On Security And Privacy Workshops, San Jose. Proceedings... Available at: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7527750>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Danaher, J., 2016. The Threat of Algocracy: Reality, Resistance and Accommodation. Philosophy and Technology, v. 29, n. 3, pp. 245-268.

Diamantopoulou, V.; Kalloniatis, C.; Gritzali, S.; Mouratidis, H. 2017. Supporting privacy by design using privacy process patterns. In: Ifip International Conference On Ict Systems Security And Privacy Protection, Rome. Proceedings… Available at: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-58469-0_33>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Doty, N.; Gupta, M. 2013. Privacy Design Patterns and Anti-Patterns: Patterns Misapplied and Unintended Consequences. In: Symposium On Usable Privacy And Security, 9., Newcastle. Proceedings... Available at: <https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2501604>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Fox, N. J.; Alldred, P., 2017. Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action. Londres: SAGE Publications.

Fritsch, L., 2013. Privacy dark patterns in identity management. In: Fritsch, L.; Roßnagel, H.; Hühnlein, D. (Eds.). Open Identity Summit 2017. Bonn: Gesellschaft für Informatik.. pp. 93-104. Available at: <https://dl.gi.de/handle/20.500.12116/3583>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Graf, C.; Wolkerstorfer, P.; Geven, A.; Tscheligi, M., 2010. A Pattern Collection for Privacy Enhancing Technology. In: International Conferences Of Pervasive Patterns And Applications, 2., Lisboa. Proceedings… Available at: <http://www.thinkmind.org/index.php?view=instance&instance=PATTERNS+2010>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Gray, C. M.; Kou, Y.; Battles, B.; Hoggatt, J.; Toombs, A. L., 2018. The Dark (Patterns) Side of UX Design. In: Conference On Human Factors In Computing Systems - Chi ’18, Montreal. Proceedings... Montreal: ACM Press, 2018. Available at:: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=3173574.3174108>. Accessed in: 30 abr. 2019.

Greenberg, S.; Boring, S.; Vermeulen, J.; Dostal, J. 2014. Dark patterns in proxemic interactions. In: Conference On Designing Interactive Systems - DIS ’14, Vancouver. Proceedings… Available at: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2598510.2598541>. Accessed in: 30 abr. 2019.

Hoepman, J.H., 2014. Privacy Design Strategies. In: Cuppens-boulahia, N.; Cuppens, F.; Jajodia, S.; Abou El Kalam, A.; Sans, T. (Eds.). ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection: SEC. Berlim: Springer,. pp. 446-459. Available at: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-55415-5_38>. Accessed in: 30 abr. 2019.

Lacey, C.; Caudwell, C., 2019. Cuteness as a “Dark Pattern” in Home Robots. In: Acm/Ieee International Conference On Human-robot Interaction, Daegu-South Korea. Proceedings... Daegu-South Korea: IEEE. pp. 374-381. Available at: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8673274/>. Accessed in: 30 abr. 2019.

Lemos, A. 2019a (in press). Epistemologia da Comunicação, Neomaterialismo e Cultura Digital.

Lemos, A., 2019b (in press). Plataformas, dataficação e performatividade algorítmica (PDPA): Desafios atuais da cibercultura.

Lewis, C., 2014. Irresistible Apps. Berkeley: Apress.

Mathur, A.; Acar, G.; Friedman, M. J.; Lucherini, E.; Mayer, J.; Chetty, M.; Narayanan, A., 2019. Dark Patterns at Scale: Findings from a Crawl of 11K Shopping Websites. Proceedings ACM Human-Computer Interaction, v. 1. Available at: <https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.07032>. Accessed in: 18 Ago. 2019.

Mayer-Schonberger, V.; Cukier, K. 2013. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, And Think. Boston: Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Nodder, C. 2013. Evil by Design: Interaction Design to Lead Us into Temptation. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons.

Patrick, A. S.; Kenny, S., 2003. From Privacy Legislation to Interface Design: Implementing Information Privacy in Human-Computer Interactions. In: Dingledine R. (Ed.). 2003. Privacy Enhancing Technologies – Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 107–124. Available at: <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-40956-4_8>. Accessed in: 30 abr. 2019.

Pearson, S.; Shen, Y., 2010. Context-aware Privacy Design Pattern Selection. In: International Conference On Trust, Privacy And Security In Digital Business, 7., 2010, Bilbao-Spain. Proceedings... Berlim/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 69-80. Available at: <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1894888.1894898>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Ponciano, L.; Barbosa, P.; Brasileiro, F.; Brito, A.; Andrade, N., 2017. Designing For Pragmatists And Fundamentalists: Privacy Concerns And Attitudes On The Internet Of Things. In: Brazilian Symposium On Human Factors In Computing Systems (IHC'17), 16, Joinville. Proceedings... Available at: <http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05905>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Sadowski, J., 2019When data is capital: Datafication, accumulation, and extraction. Big Data & Society, v. 6, n. 1, p. 1-12, 2019.

Silveira, S. A., 2018. Tudo sobre Tod@s: Redes digitais, privacidade e venda de dados pessoais. São Paulo: Edições Sesc SP..

Srnicek, N., 2017. Platform capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Trice, M.; Potts, L., 2018. Building Dark Patterns into Platforms: How GamerGate Perturbed Twitter’s User Experience In: Present Tense. Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, v. 6, n. 3, p. 1. Available at: <https://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/building-dark-patterns-into-platforms-how-gamergate-perturbed-twitters-user-experience/>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Van Dijck, J.; Poell, T.; De Waal, M., 2018. The Platform Society. Nova iorque: Oxford University Press.

Williams, M.; Nurse, J. R. C.; Creese, S., 2016. The perfect storm: The privacy paradox and the Internet-of-things. In: International Conference On Availability, Reliability And Security, 11, 2016, Salzburg-Áustria. Proceedings... Available at: <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7784629>. Accessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

Zagal, J. P.; Björk, S.; Lewis, C., 2013. Dark Patterns in the Design of Games. In: FDG 2013 - International Conference On The Foundations Of Digital Games, 8, Chania-Grécia. Proceedings… Available at: <http://www.fdg2013.org/program/papers.html>. Acessed in: 12 jul. 2018.

ZUuboff, S., 2015. Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, v. 30, n. 1, pp. 75-89.

1 Available at youtube.com/watch?v=zaubGV2OG5U

2 The use of design patterns to create a universal language for architecture was postulated by the architect Christopher Alexander (1977). As his work became more widely known, it inspired similar efforts in other fields, such as software engineering and interaction design.

3 Disponível em: ft.com/content/e24dea0a-6b57-11e9-80c7-60ee53e6681d.

5 Available at nytimes.com/2016/05/15/technology/personaltech/when-websites-wont-take-no-for-an-answer.html.

6 Available at theverge.com/2013/8/29/4640308/dark-patterns-inside-the-interfaces-designed-to-trick-you.

7 Available at https://www.darkpatterns.org/types-of-dark-pattern.

8 Acronym for the Big Five: Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft.

10 The screenshots were manually captured and imported into the software. There is no isonomy in the number of screenshots of each app. Subsequently, focused coding was conducted to identify the MIs. Not all MIs described in literature concern privacy issues; therefore, not all of them appear in the corpus.

11 A partnership between Salvador City Hall and Itaú bank. Users can take advantage of 400 bicycles at 50 stations. The Bike Itaú app is a mediator that allows people to pay for the service (with daily, monthly or annual plans), locate the nearest station and borrow a bicycle.

12 Examples can be found in various sources, such as Brignull’s official site (darkpatterns.org/hall-of-shame), the Dark Pattern project Twitter feed (twitter.com/darkpatterns), a community set up by researchers (dark.privacypatterns.eu), and Reddit communities dedicated to the subject (reddit.com/r/darkpatterns/) (reddit.com/r/assholedesign/). Several other articles have helped to expand the catalog of MIs, such as Bosch et al. (2016) and Gray et al. (2018).

13 This is confirmed by recent studies. Arunesh Mathur et al. (2019) showed that MIs were present in 11.1% of approximately 11,000 online shopping sites they analyzed. Their analysis revealed the existence of online services for implementing MIs in shopping sites in the form of plugins and add-ons. These services are advertised openly as a way of boosting sales.

14 Interaction strategies that make it difficult for consumers to compare prices. Although they are more common in e-commerce, we found Price Comparison Prevention patterns in the apps in the corpus in this study which sell service packages.

15The user is prevented from cancelling the service he has signed up for or cancelling his account in a particular app or website. Companies tend to put obstacles in the user’s way so that he keeps his data linked to the platform.

16 The aim of this MI is to divert the user’s attention from aspects of the interface that the company does not want him to see or to direct his gaze or efforts toward a particular task in the sequence of actions he is required to perform.