DOMESTICIDADE E VIGILÂNCIA: O EXEMPLO DA CASA DE MELNIKOV

Ana Sofia Pereira Silva é Doutora em Arquitetura, Professora Auxiliar convidada na Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP) e pesquisadora no Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo (CEAU), Portugal..

Como citar esse texto: SILVA, A.S.P. Domesticidade e vigilância: o exemplo da casa de Melnikov. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 12, 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=4&item=4&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 18 Jul. 2025.

Resumo:

Konstantin Melnikov projectou a sua casa em 1927. Embora fosse já um arquiteto internacionalmente reconhecido, foi gradualmente afastado da prática arquitetônica pelas mudanças politicas que se operavam à época. Após o seu afastamento, Konstantin Melnikov viveu praticamente o resto da sua vida em reclusão na sua casa. A inscrição no topo da casa – Konstantin Melnikov Arquitecto - é contraditória com o espírito socialista que vigorava então. A afirmação de individualidade do habitante revela desde logo um espírito dissonante do contexto e da época em que se insere. Com esta inscrição, sublinha o direito à individualidade como denotarão alguns dos espaços concebidos para o trabalho individual no âmbito da casa. Por outro lado, a análise desta obra permite a observação de diferentes mecanismos de vigilância: relativos à vigilância interior e mútuo controlo entre os membros da família e relativos à possibilidade dada aos habitantes da casa de observarem o exterior. No seu estúdio, Konstantin Melnikov podia observar o espaço exterior. No entanto, a vontade de instaurar uma vigilância no seio da casa deve também ser reconhecida na concepção de vários cômodos, tal como a sala de jantar, o quarto de vestir ou o quarto de dormir. Especialmente no último reconhece-se uma semelhança com os princípios do modelo panóptico desenvolvido por Jeremy Bentham. O engenho arquitetônico que se reconhece em algumas das soluções desenvolvidas nesta casa é motivo de crescente interesse quando estas são confrontadas com as contradições que envolvem o habitar da casa.

Palavras-chave:: Melnikov, domesticidade, individualidade, coletividade, vigilância.

A CASA QUE SE CONSTRUIU KONSTANTIN MELNIKOV

No topo do edifício situado no número 10 da Rua Krivoarbatsky, em Moscou, pode-se ler a inscrição Konstantin Melnikov arquitecto. Esta casa foi projetada pelo arquiteto em 1927. Nesse período ele estava no auge de sua carreira, somando vários encargos como, por exemplo, o clube Rusakov ou o clube de trabalhadores da fábrica Svoboda. Apesar de ser ainda relativamente jovem, ele já gozava de um certo reconhecimento internacional à época. Acompanhando a turbulência posterior à revolução russa de 1917, grande parte da produção arquitetônica de Konstantin Melnikov insere-se neste contexto interessante de criação. A solução excepcional que se reconhece nesta casa surge também neste contexto. O projeto desta casa revela a procura de um território doméstico alternativo ao caos social e econômico que se vivia no período pós-revolução. A própria solução construtiva, desenvolvida a partir de paredes estruturais periféricas em tijolo e lajes de madeira, permitindo a inexistência de apoios pontuais no interior, reflete o engenho do arquiteto. Estando próximo da abordagem modernista, Melnikov mantém-se ligado à condição mais perene: ele usa os recursos elementares escassos disponíveis, para desenvolver novas proposições por meio de soluções inovadoras. A sua prosperidade profissional conheceria um fim com a ascensão de Stalin ao poder. Sob o domínio do novo líder, a arquitetura moderna deixava de ser bem-vinda na Rússia, pelo que Melnikov foi progressivamente afastado da sua prática arquitetônica. A partir deste momento, Konstantin Melnikov viveu em reclusão na sua casa praticamente o resto da sua vida, dedicando-se à pintura como meio de sustento da sua família.

Onde quer que se situasse, a casa de Melnikov seria um objeto estranho. A casa contrasta em escala e linguagem com o contexto urbano no qual se insere. Esta pequena casa unifamiliar está rodeada por edifícios de habitação plurifamiliar com vários pisos. A estranheza da sua presença questiona a sua origem. Este questionamento sem resposta imediata revela a sua unicidade.

A casa localiza-se num lote que confronta a rua pública no seu lado de menor dimensão. O confronto da propriedade privada com a Rua Krivoarbatsky faz-se através de uma cerca de madeira, que mantém a transparência do lote de Melnikov. Apenas na zona da entrada, o espaçamento entre os elementos verticais da cerca de madeira é mais reduzido, diminuindo a visibilidade do interior. Associado à maior opacidade da vedação na zona da entrada encontra-se um elemento curvo que cria um filtro que inibe a vista frontal da casa quando se entra no lote a partir do espaço público. Há uma opacidade imposta para aqueles que esperam para entrar no perímetro da casa. O portão enfatiza o limite e essa transição espacial anuncia ao habitante a entrada em um espaço de natureza diferente.

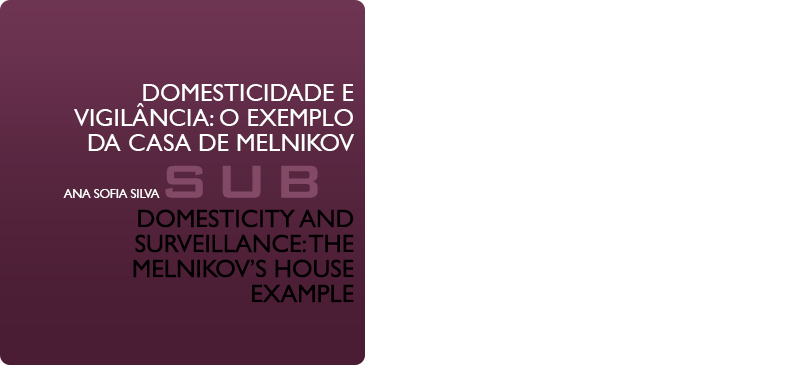

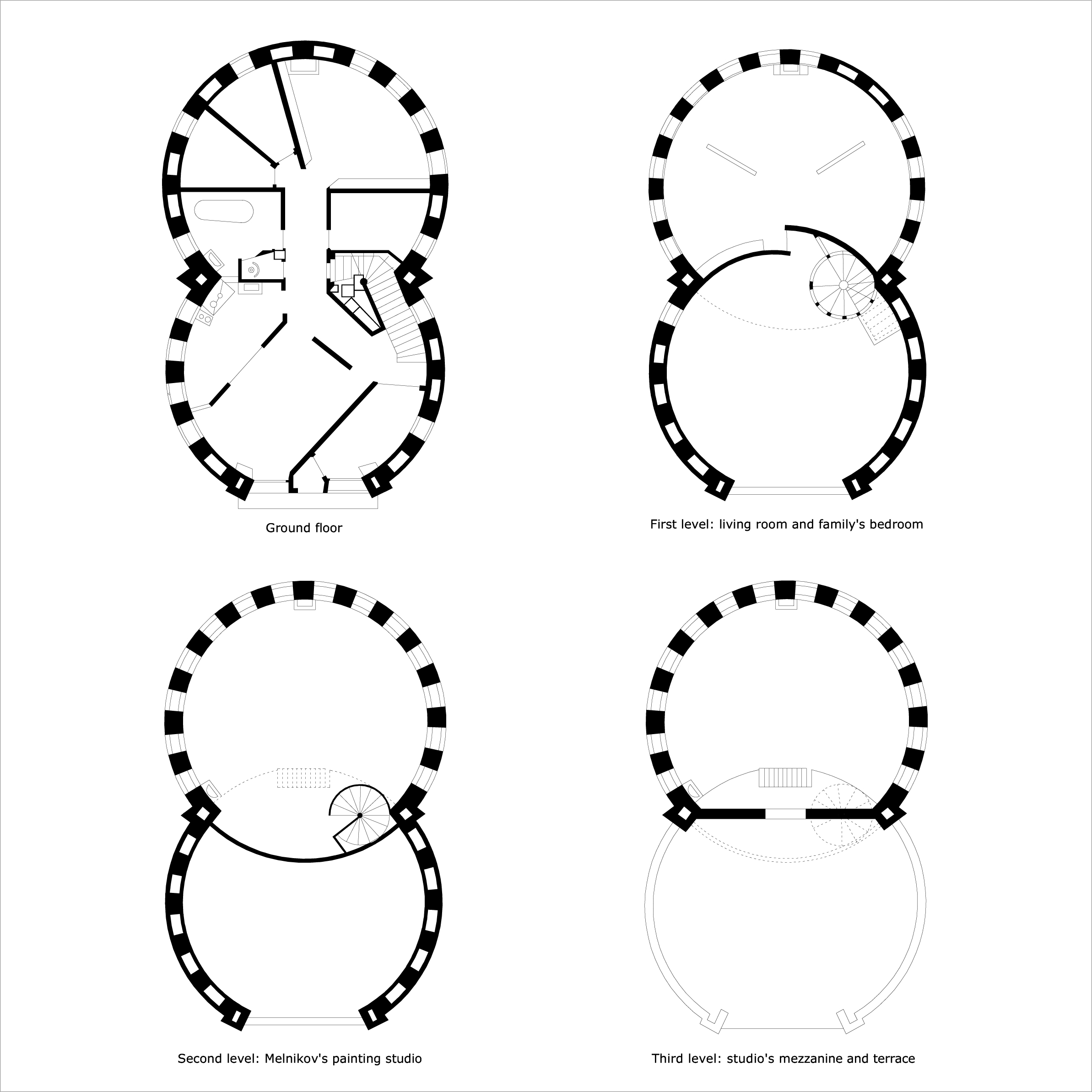

Fig. 1: Plantas da casa Melnikov.

Fonte: Desenho da autora.

A casa foi construída a partir de uma estratégia de composição atípica (Fig. 1). A planta da casa de Melnikov é o produto da união de dois círculos. No entanto, esta união não exclui a independência de cada círculo na forma volumétrica final. Independe da união dos dois volumes cilíndricos, há duas chaminés laterais que acentuam a intersecção entre eles. Funcionalmente, esta distinção entre os dois volumes também pode ser identificada, uma vez que cada cilindro tem um uso diferente. Os diferentes espaços estão distribuídos através de vários níveis da casa restringindo a possibilidade de um habitar simultâneo no interior dos diferentes cilindros. O cilindro mais próximo da rua alberga os espaços dedicados à vida social da casa. No piso térreo encontra-se o vestíbulo de entrada, a sala de jantar e cozinha. No primeiro piso situa-se a sala de estar, que se abre para a cidade através da existência de um grande pano de vidro. No interior do outro cilindro, ligado ao interior do bloco, encontram-se os espaços mais reservados. No piso térreo localiza-se o quarto de banho, o sanitário, um quarto de vestir para toda a família e quartos de uso diurno para a esposa, filho e filha de Melnikov. No primeiro piso, contíguo à sala de estar, situa-se o quarto de dormir coletivo de toda a família. No nível acima está o estúdio de pintura de Konstantin Melnikov. As áreas sociais concentram-se assim no cilindro que se relaciona diretamente com o espaço público (voltando-se para a Rua Krivoarbatsky), e o programa com um caráter mais privado, recolhe-se na parte posterior do edifício, afastando-se do olhar público. Os dois tipos de janelas reconhecíveis nesta construção confirmam a mesma distinção público-privado. Se no ‘cilindro social’ se encontra uma ampla abertura que abrange a entrada, a sala de jantar, a cozinha e a sala de estar, criando uma relação de abertura para com o espaço exterior; no ‘cilindro privado’ a estratégia de abertura para o exterior é bastante diferente: os vãos são mais reduzidos e estão posicionados de forma mais abstrata. Embora, num primeiro olhar, a casa possa parecer um objeto estranho, através da ampla abertura voltada para a rua, o arquiteto parecer querer afirmar a pertença da casa ao seu tempo e ao seu lugar. Através desta janela, a casa parece querer vincular-se ao lugar, já que é o único elemento que estabelece claramente uma relação geométrica com o espaço envolvente, tal como permite uma relação entre espaço interior da casa e espaço exterior da cidade. Este pano de vidro surge de um corte no volume cilíndrico paralelo ao alinhamento da Rua Krivoarbatsky, abrindo a casa à cidade. Esta grande janela é a única que permite a observação do espaço interior da casa; as outras janelas mantém a imagem hermética da construção. No entanto, com este pano de vidro, a casa também relaciona-se a seu tempo, a vista da janela abrange salas diferentes, presumindo sua forma, independente da distribuição do programas no interior. Em oposição à fachada pública emerge um volume mais íntimo, remetido para os bastidores do lote, caracterizado pelas suas janelas peculiares (Fig. 2). É uma parte misteriosa, um contentor que parece encerrar algo que deve ser preservado ou escondido. A espessura das paredes exteriores, que se dilui perante a generosa dimensão do pano de vidro da fachada sul, parece expandir-se quando se observam as aberturas hexagonais que caracterizam o cilindro mais reservado. Para além da sua forma incomum, estes vãos profundos e compostos por dupla caixilharia, inibem a observação do interior da casa a partir da envolvência exterior. A observação a partir do exterior dificilmente permitirá perceber o que se passa por trás das estranhas janelas hexagonais. Neste projeto, o íntimo se refugia atrás da parte social da casa, e defende-se dos olhares externos por uma estratégia abstrata das aberturas em função do posicionamento e da forma sem referência.

Fig. 2: Vista atual exterior da casa Melnikov.

Fonte: Cortesia da Professora Natalia Dushkina.

Nesta casa observam-se dois mecanismos diferentes de vigilância. Um é relativo à vigilância no âmbito dos espaços interiores da casa, o outro concerne a possibilidade de observação da sua envolvência exterior. No seu estúdio, Melnikov controla o espaço circundante, da possibilidade de o vigiar retira o seu poder. De forma distinta, a concepção espacial da área de dormir também remete para outra forma de vigilância doméstica. Embora de maneiras diferentes, reconhecem-se, em ambas as situações, semelhanças com o modelo panóptico de Jeremy Bentham.

Panóptico é um termo composto por pan (tudo, noção do total) e opticon (relacionado com a visão). Assim sendo, panóptico alude para a possibilidade de observação total, para uma visão abrangente. O panóptico é um modelo arquitetônico desenvolvido pelo filósofo utilitarista Jeremy Bentham, no fim do século XVIII. Este modelo foi inventado após a revolução industrial inglesa, emergindo num contexto caracterizado pelo crescimento demográfico e pela necessidade de controlo social.

O modelo panóptico consiste na optimização da vigilância dos reclusos pelo posicionamento das células ao longo de um perímetro circular do edifício e pela implantação de uma torre de vigia no centro da construção cilíndrica. As celas dos reclusos deveriam ser encerradas por uma grade metálica no confronto com o pátio interior circular, prevendo aberturas para o exterior. A abertura para o espaço exterior, bem como a exposição perante o pátio interior, permitiriam uma intensa iluminação do interior das células que contrariaria a escuridão que prevalecia no interior da torre de vigia. Esta inversão permitiria uma eficácia superior na observação dos reclusos nas suas celas por dois motivos: por um lado, a boa iluminação das celas permitiria ao vigilante uma maior capacidade de observar as atividades dos reclusos nas suas celas; por outro lado, os reclusos, perante a escuridão da torre, não conseguiriam identificar a presença ou ausência do vigilante. Assim a presença da torre seria suficiente para implantar nos encarcerados a sensação de estarem a ser observados.

O encarceramento, que anteriormente implicava construções opressivas (tal como masmorras), mantinha os reclusos em cativeiro pela impossibilidade física que teriam em evadir-se de estruturas de tal natureza. Com o modelo panóptico, a reclusão dos prisioneiros resultaria de um tipo distinto de sujeição, que operaria em grande parte a um nível psicológico. A detenção dos reclusos resultaria assim da sensação de ser observado, o que, em conseqüência, os paralisava. O modelo panóptico permitiria assim uma construção mais ligeira; as células poderiam ser mais ventiladas e iluminadas. Os reclusos ficariam privados de intimidade, não tendo o privilégio de usufruir de um canto para si.

Na casa de Konstantin Melnikov a sala de jantar é o principal espaço social da rotina quotidiana da família. É o espaço onde a família de reúne para tomar as suas refeições e onde os convidados são recebidos. Neste compartimento particular poder-se-á identificar uma hierarquia. As iniciais de Konstantin e de Anna, a sua esposa, aparecem bordadas nas telas que cobrem as cadeiras de espaldar alto localizadas em lados opostos da mesa. Estas indiciam, à partida, uma hierarquia relativa ao posicionamento no espaço. Na sala de jantar, o lugar de cada elemento da família está claramente identificado. A identificação da cadeira de Melnikov, por exemplo, mostra que o arquiteto se sentaria de costas voltadas para a rua. Sentando-se de costas para a janela aproveitaria a luz natural de sul que iluminaria a sua família, que assim ele poderia contemplar melhor. Pelo contrário, do ponto de vista da restante família, o arquiteto localizar-se-ia na sombra, situando-se contra a luz, ficando assim o contorno da sua figura envolto por luz. Este posicionamento poderia ser o suficiente para encenar ou reforçar a sua presença patriarcal.

ESPAÇOS INDIVIDUAIS OU O HABITAR DIURNO

Nesta casa existe uma separação entre habitar diurno e noturno. Enquanto cada habitante usufruía de um cômodo individual dedicado unicamente ao habitar diurno, no período noturno toda a família ocupava um único quarto. Na casa de Melnikov os quartos individuais estão assim associados ao habitar diurno. Este facto revela que, para este arquiteto, a reclusão individual poderá estar relacionada com a necessidade de concentração ou com a dedicação a determinada atividade. O descanso ou o sono, que ao longo da história dos últimos séculos relevaram ser razão para a procura de reclusão individual, acabam por ser motivo de reunião nesta casa. O habitante poderia isolar-se com o propósito do estudo ou da criação, mas enquanto em inatividade cada individuo deveria reunir-se com os outros membros da família no quarto coletivo. Assim, o sono era encarado nesta casa como uma atividade coletiva; cada individuo se observaria mutuamente. Nesta observação mútua está implícito um sentido de proteção, bem como uma vontade de controlo.

Relativamente ao habitar intimo e individual, como referido anteriormente, foi proposta nesta casa uma concepção programática pouco usual. Melnikov desenhou três quartos individuais no piso térreo destinados à sua esposa, filho e filha; para si próprio projetou um atelier no piso mais elevado do mesmo lado da casa (Fig. 1). Tanto a Viktor como a Ludmila (filho e filha) foram destinados dois quartos similares, situados perto da cozinha e do quarto individual da mãe. Os descendentes usufruíam do direito de terem um espaço próprio, embora a possibilidade de controlo parental estivesse assegurada. Ambos os quartos de Viktor e Ludmila estavam subordinados à geometria radial sugerida pelo perímetro circular. As portas dos quartos estavam localizadas nas zonas de menor dimensão e as janelas hexagonais situadas na parede oposta, intersectando a fachada curva. Em certa medida, também a configuração destes espaços relembra a concepção espacial do modelo panóptico.

O cômodo que Konstantin projetou para si próprio revela características muito diferentes. Ele localizou seu estúdio no lugar mais isolado da casa: distante da rua, do solo, das atividades diárias da casa e dos espaços diurnos dos outros membros da família. Além disso, sobre a distribuição do programa, existe uma associação das atividades mundanas com o piso inferior (delimitada para o chão) e às atividades relativas ao espírito com os níveis superiores (mais próximo para o céu).

O atelier é o único compartimento caracterizado pelo uso pleno da planta circular, nunca completo e apenas implícito nos restantes compartimentos da casa. O ângulo de aproximadamente 260 graus que a fachada cilíndrica completa, abarca o este, norte e oeste, permitindo ao habitante a percepção do percurso solar ao longo do dia e a constância da luz refletida de norte, apropriada para a pintura. Na fachada cilíndrica os vãos hexagonais vão-se repetindo em três níveis distintos. Este conjunto de janelas permite o controlo da vida que se passa em redor deste espaço. A silhueta peculiar e a repetição destes vãos, associadas à forma cilíndrica do espaço do atelier, parece evocar espacialmente uma espécie de torre de vigia. No atelier o seu habitante tem a possibilidade de observar o exterior em praticamente todo o seu perímetro.

Fig. 3: Vista atual interior do atelier de Melnikov.

Fonte: Cortesia da Professora Natalia Dushkina.

O atelier de Melnikov apresenta-se assim como a torre de vigia de um modelo panóptico, mas, ao contrário da torre de J. Bentham, o atelier não encontra celas em seu redor. Este espaço é a torre de controlo que observa, numa primeira camada envolvente, a vizinhança e, no limite, a cidade. O habitante vigilante vê o seu espaço iluminado com luz e animado com vistas exteriores que entram pelas janelas panópticas; ao contrário do observador exterior, que pouca informação do interior do espaço do atelier conseguirá retirar a partir da sua observação. A dupla estrutura da parede exterior, a dupla carpintaria dos vãos, bem como a sua repetição abstrata, inibem os olhares exteriores. Desde o interior, o habitante observa o exterior enquadrado pelas janelas hexagonais. Elas fixam as diferentes vistas exteriores na parede cilíndrica como se fossem écrans. Enquanto se visualiza a casa a partir do exterior, o volume do atelier expõe as janelas hexagonais como vão obscuros e impenetráveis. O habitante do atelier observa assim o mundo através da sua sombra iluminada.

Contudo o habitante do atelier não só teria a possibilidade de ver o mundo sem ser visto, como poderia também observar o seu próprio mundo interior como se o olhasse de fora. Melnikov poderia subir para o mezanino que lhe permitiria uma visão dominante sobre o espaço interior do atelier. Neste sentido o habitante criativo tinha a possibilidade de observar o seu trabalho de um ponto de vista superior e afastado.

Fig. 4: Vista atual interior do mezanino do atelier de Melnikov.

Fonte: Cortesia da Professora Natalia Dushkina.

O atelier destina-se ao habitante que procura reclusão para se concentrar na sua produção individual. A cumplicidade entre Konstantin Melnikov e o seu filho, Viktor, era de tal ordem que se sabe terem pintado juntos. Quando Viktor se decidiu dedicar à pintura, Melnikov cedeu o atelier ao seu filho, transformando a sala de estar, localizada no primeiro piso, no seu novo atelier. É curioso que a próxima colaboração entre pai e filho não tenha resultado na partilha do espaço de trabalho, mas sim na transformação do programa da casa e na criação de um novo atelier, de forma a obter-se um novo espaço individual de trabalho. Os caminhos da vida e as práticas do habitar ditaram que o espaço da sala de estar, projetado para ser aberto para a cidade, acabou sendo transformado no segundo atelier de Melnikov.

DORMIR: O HABITAR COMUM

O quarto de dormir da família Melnikov revela um interesse particular. Embora se consigam identificar três camas, apresenta-se como um único quarto. As três zonas de dormir estão delimitadas por dois tabiques soltos das paredes exterior e interior e colocados segundo uma composição radial. Não existem portas que permitam o encerramento efetivo das diferentes zonas. A composição do espaço sugere que, independentemente da existência das duas finas paredes, o espaço foi concebido como um. A partir da entrada do quarto o habitante tem uma visão total do espaço. De um outro ponto de vista, a composição do quarto relaciona-se, uma vez mais, com o modelo panóptico. A possibilidade de controlo simultâneo das três áreas de dormir, a partir de um único ponto central de observação, revela-se semelhante ao modelo inventado por Bentham.

Fig. 5: Vista atual interior do quarto da família.

Fonte: Cortesia da Professora Natalia Dushkina.

O reconhecimento da estratégica do modelo panóptico aplicada à concepção do quarto levanta algumas questões. Desde da corrente prática medieval de partilha do mesmo quarto para dormir por vários habitantes, que levou à necessidade de conceber estruturas mais íntimas como alcovas, até à reivindicação do quarto individual, várias condições, estratégias compositivas e dispositivos arquitetônicos foram desenvolvidos de forma a conquistar-se um habitar íntimo do espaço dedicado ao descanso e às relações íntimas. O quarto desenhado por Melnikov propõe a reunião do espaço de dormir. Os dois tabiques de madeira apresentam-se como elementos de partição inexpressivos, que apenas inibem o contato visual entre os habitantes quando deitados nas suas camas. No entanto, cada som ou movimento de um habitante será apreensível. Enquanto deitados os elementos da família não terão possibilidade de se verem, no entanto aquele que entra ou sai do cômodo terá a possibilidade de observar simultaneamente as três zonas de dormir. Para os habitantes deste quarto a possibilidade de ser observado é uma condição iminente.

Estabelecendo o paralelo com o modelo panóptico, o umbral que marca a entrada no quarto poderia corresponder à torre central de vigia. A divisão compositiva das três zonas de dormir poderá ser comparável à estratégia usada por Bentham na distribuição das celas dos reclusos. A divisão radial, a posição das camas, a forte iluminação das celas proporcionada pela janelas hexagonais e o consequente obscurecimento do ponto de entrada no quarto, são factos que consolidam a correspondência deste espaço ao modelo panóptico. A posição das camas, incluindo a orientação da cabeceiras, revela a opção que mais expõe o seus habitantes. A área de dormir destinada aos pais localizava-se no centro das três zonas. Este posicionamento promoveu o controle parental. Eles separaram as células do filho e da filha, observando e sentindo todos os movimentos dos descendentes.

Juhani Pallasmaa (1996) relata a obsessão de Melnikov com a limpeza. Este autor explica, sob este argumento, a decisão do arquiteto optar por, no quarto, anular arestas, criando superfícies curvas que proporcionam uma continuidade entre superfícies concorrentes, e a opção de colocar o quarto de vestir no piso térreo. Se o encontro curvo entre as superfícies de chão, paredes e teto permitem uma limpeza mais fácil, a inexistência de arestas também promove uma continuidade entre superfícies, fomentando nos seus habitantes a sensação de se acomodarem numa única superfície envolvente. Embora exista uma divisão em três zonas, o quarto quer assim representar uma única entidade, um único corpo.

Melnikov pinta todas as superfícies do quarto em stucco lustro pintado de um dourado pálido. Esta cor e acabamento, associados à forte iluminação que entrava no quarto a partir das janelas hexagonais localizadas na parede cilíndrica, encenariam certamente um acordar dourado para o novo dia. O amanhecer, visto como uma espécie de renascimento, poderia explicar a encenação mística que está implícita na concepção do espaço do quarto.

Na concepção original1, as camas estavam fixas ao chão, respeitando as suas localizações a composição radial do quarto. Estas peças de mobiliário, também concebidas pelo arquiteto, surgem no quarto como pedestais fixos ao pavimento, numa lógica de continuidade curva entre superfícies concorrentes igual à descrita anteriormente. A posição fixa das camas implicou uma programação estrutural da sua execução. Assim, nesta casa, as camas foram matéria construtiva tal como as paredes e o chão. A cama como um pedestal fixo enobrece o ato de dormir; contudo a sua posição fixa promove também a sensação de paralisia dos seus habitantes. Neste sentido, a concepção da cama pertence também uma lógica de encenação total, sublinhando a concepção panóptica do espaço. Neste quarto o habitar noturno converge entre a consagração do sono, a subtração da reclusão individual e a consequente inexistência de intimidade individual.

UM ESPAÇO UMBRAL

Outras atividades usualmente associadas ao âmbito do quarto foram deslocadas da sua envolvência. Para além dos compartimentos de uso diurno projetados por Melnikov para a sua esposa e para os seus filhos, projetou ainda outro espaço no piso térreo: o quarto de vestir. A existência e a localização deste cômodo revela a vontade de deslocar a atividade de vestir do quarto. Esta distinção programática pode relacionar-se com a importância da limpeza para Melnikov, anteriormente referida, como pode relacionar-se com outros motivos. Embora tenha aparentemente um papel secundário no programa desta casa, não há dúvida que a concepção deste cômodo revela práticas domésticas de habitar específicas.

No quarto de vestir existem dois conjuntos de armários ao longo das duas paredes radiais. Cada um destes conjuntos é distinguido pela sua cor: o branco corresponde ao armário da mãe e da filha e o amarelo guarda o vestuário do pai e do filho. A distinção cromática não se traduz numa indicação de individualidade mas emerge como uma distinção de gênero dos membros da família, embora as roupas se constituam numa das propriedades mais individuais. A troca de vestuário apropriado a cada situação implicaria uma visita ao quarto de vestir. A passagem do espaço doméstico para o espaço público, do interior para o exterior ou do habitar diurno para o habitar noturno, implicaria um habitar transitório deste espaço. Neste sentido, este quarto deveria ser ocupado entre diferentes tipos de habitar, pautando as rotinas diárias. Este quarto apresenta-se como uma espécie de espaço – umbral, um espaço habitado de forma transitória, intermediário de formas diferentes ou opostas de habitar. A identificação deste umbral reforça a convicção das formas de habitar de naturezas opostas coexistentes nesta casa.

ENTRE A AFIRMAÇÃO E A EXCLUSÃO DA INDIVIDUALIDADE

Melnikov concebe um hino doméstico à sua própria personalidade. A inscrição do seu nome no topo do edifício revela a afirmação pública da sua individualidade no período do culto do coletivismo, sob a ideologia soviética. Desafiando o sistema que incitou uma conduta comum de vida para cada individuo, e que levou Melnikov a uma vida confinada na sua própria casa, o arquiteto seguramente tencionou sublinhar a importância capital de cada indivíduo. No entanto, a casa de Melnikov não se revela o território mais favorável a uma completa experiência da individualidade. Independentemente da perversão que se poderá ler na vontade de vigilância implícita na concepção de vários espaços da casa será importante contextualizar o espírito patriarca de Melnikov em associação com a sua perceptível natureza mística. Tal como outras experiências realizadas por arquitetos, o projeto e a vivência desta casa revelam um caráter laboratorial. O dia-a-dia da vida da própria família surge, de certa forma, encarada como experiência. A vida privada revela-se assim como extensão da experiência de construir o espaço e a arquitetura surge como disciplina potencialmente impositiva na regulação de comportamentos, proporcionando ou inibindo liberdades através da conformação espacial.

A época que marcou a juventude de Melnikov caracterizava-se pela crença na possibilidade de se poder limar a natureza humana, através da arquitetura. A esperança, a revolução, ou o engano, fizeram crer que se poderia moldar a natureza complexa e contraditória do homem, tornando-o um ser melhor. Praticamente contemporâneo à construção da casa Melnikov (1929-1930), resultado de um concurso para a elaboração de um complexo que deveria ser construído na periferia de Moscou denominado de Cidade Verde, Melnikov propõe um edifício que apelida de Sonata do Sono (STARR, 1981). Neste projeto explora e propõe uma série de dispositivos e concepções arquitetônicas que permitiriam aos seus habitantes temporários usufruir de um sono reabilitador. Esta importância dada ao descanso individual, que surge como tema de indiscutível importância tanto na sua casa como no projeto não realizado citado, é apenas um dos sintomas da crença que, numa Europa entre guerras e numa Rússia em revolução, vai surgindo implícita no trabalho de alguns arquitetos modernistas: a arquitetura vista como disciplina que participaria ativamente na reabilitação do homem.

REFERÊNCIAS

Conversa informal com Dra. Natalia Dushkina (Professora do Moscow Architectural Institute) realizada em Madri, em Junho de 2011.

PALLASMAA, Juhani. The Melnikov House: Moscow (1927-1929): Konstantin Melnikov. Londres: Academy, 1996.

STARR, S. Frederick. Melnikov: solo architect in a mass society. Princeton, Nova Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981.

1 Os documentos de Melnikov não se encontram disponíveis no presente, dada uma disputa legal, pelo que não é possível a publicação de imagens do estado original da casa. As fotografias aqui apresentadas são da cortesia da Professora Natalia Dushkina, professora no Instituto de Arquitetura de Moscou.

DOMESTICITY AND SURVEILLANCE: THE MELNIKOV’S HOUSE EXAMPLE

Ana Sofia Pereira Silva is Doctor in Architecture, Guest Assistent Professor at the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Porto, Portugal, and researcher at the Center of Studies in Architecture and Urbanism..

How to quote this text: Silva, A.S.P., 2016. Domesticity and surveillance: the Melnikov’s house example. V!RUS, [e-journal] 12. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus12/?sec=4&item=4&lang=en>. [Accessed: 18 July 2025].

Abstract:

Konstantin Melnikov designed his house in 1927. At the time he was an internationally renowned architect, but the political changes gradually withdrew him from his architectural practice. After being banned Konstantin Melnikov lived nearly in seclusion in his house the rest of his life. The inscription on the top of his house – Konstantin Melnikov Architect – contradicts the socialist spirit that then ruled. The inhabitant’s individual affirmation reveals a dissonant spirit with its context and the epoch he belongs. With this inscription, he underlines his right to individuality, as shown by several rooms conceived to the individual labor in this house. On the other hand, the analysis of this house allows the identification of different kinds of surveillance. One refers to the interior vigilance and mutual control between family members and the other is related to the possibility the house’s inhabitant was given to surveil the exterior surroundings. In his studio Konstantin Melnikov could observe the exterior space. Nevertheless, we can also recognize the will of interior surveillance in the conception of several rooms, such as the dining room, the dressing room or the bedroom. Especially in the last one similarity to the Jeremy Bentham's panoptical model principles can be recognized. The architectonic inventiveness recognized in several solutions developed in this house is a motive of growing interest when confronted with the contradictions that involve the inhabiting practices of this house.

Keywords:: Melnikov, domesticity, individuality, collectivity, surveillance.

The house that Konstantin Melnikov built to himself

On the top of the building located at the number 10 of Krivoarbatsky Street, in Moscow, we can read the inscription Konstantin Melnikov architect. This house was designed by the architect in 1927. In this period he was at the peak of his career, having several assignments, such as, the Rusakov club or the Svoboda factory’s club. Despite being rather young, he enjoyed a certain international recognition at the time. Along with the posterior turbulence of the Russian Revolution of 1917, a considerable part of Melnikov’s architectonic production is developed in this interesting context of creation. The exceptional solution developed in this house also emerges in this context. The house’s project reveals the search for a domestic territory that should be alternative to the social and economic chaos that was lived in the post Revolution period. The constructive solution developed, that opted for peripheral brick structural walls and wooden slabs, allowing the inexistence of punctual structural support in the interior of the house, reflects the architect’s inventiveness. Being close to the modernist approach, Melnikov maintains himself attached to the most perennial condition: he uses the scarce elemental resources available, to develop new propositions through innovative solutions. His professional prosperity would meet an end with Stalin’s rise to power. Under the new leader, modern architecture was no longer welcome in Russia, so Melnikov was progressively inhibited from his practice. From this moment on Konstantin Melnikov lived in isolation practically the rest of his life, devoting himself to painting as a means to support his family.

This house would be a strange object wherever it would be located. The house contrasts in scale and language with the urban context. This little single family house is surrounded by multifamily buildings with several floors. The strangeness of its presence questions its origin and this query without an immediate answer reveals its uniqueness.

The house is located at a plot that confronts the public street with its smaller size. The confrontation of the private property with the Krivoarbatsky Street is made by a wooden fence, that maintains the transparency of Melnikov’s plot. Only in the entrance zone, the spacing between the vertical elements made of wood is reduced, diminishing the interior’s visibility. Associated to the fence’s opacity in the entrance surroundings, there is also a curved element creating a spatial filter, which prevents a frontal view of the house when entering from the public space to the private property. There’s an opacity imposed to those who wait to enter the house perimeter. The gate underlines the threshold and this spatial transition announces the inhabitant the entrance to a different nature of space.

Fig. 1: Melnikov’s house plans. Source: Re-drawn by the author

The house is based in an atypical compositional form (Fig. 1). Melnikov’s house plan is the result of the reunion of two circles. Nevertheless this reunion doesn’t mean that each circle doesn’t claim its independence in the final volumetric shape. Despite the reunion of the two cylindrical volumes, there are two lateral chimneys that underline the intersections between them. Functionally, this distinction can also be identified, since each cylinder has a different usage. The different spaces are distributed through the several levels of the house constraining the possibility of a simultaneous inhabiting of the different cylinder interiors.

The cylinder closer to the street holds the rooms devoted to social life. In the ground floor we can find the entrance hall, the dining room and the kitchen. The first floor comprises the living room, opened to the city through a view window. In the interior of the other cylinder, connected to the interior of the block, lie the most reserved spaces. In the ground floor is the bathing room, the water closet, Melkinov’s son, daughter and wife daily rooms and a dressing room for the family. In the first floor, contiguous to the living room, is the family’s bedroom. The level above holds Konstantin Melnikov’s painting studio. The social areas sit in the cylinder, which is connected to the public space (the Krivoarbatsky Street), and the private program stands in the posterior part of the building, kept away from the public view. The two types of windows recognizable in this construction also reveal the same public-private distinction. If in the ‘social cylinder‘ there is a wide opening, spanning entrance, dining room, kitchen and living room, which create an open relation with the exterior, in the ‘private cylinder‘ the strategy of the openness to the exterior is remarkably different, with smaller windows more abstractly positioned.

Although at a first glance the house may seem a foreign object, through the wide opening the architect seems to affirm the house’s belonging to his time and place. Through the window located at the south façade the house connects itself to the place, as it is the only element that clearly establishes a geometrical relation with the surroundings, as well as a direct relation between the interior space of the house and the exterior space of the city. The window emerges geometrically from a parallel cut to Krivoarbatsky Street in the cylindrical volume, opening the house to the city. This big window is the only one allowing the observation of the house’s interior space; the other voids maintain the hermetic image of the construction. Nevertheless, with this window the house also relates itself to its time, as the view window comprises different rooms, assuming its shape regardless of the interior’s program distribution.

Fig. 2: Present exterior view of Melnikov’s house exterior. Source: Image courtesy of Professor Natalia Dushkina.

In opposition to the public façade there is a more intimate volume emerging behind, with its peculiar windows and its backstage location (Fig. 2). It is a mysterious part, a container that seems to enclosure something that may be preserved or hidden. The thicknesses of the exterior walls, which dilute before the dimension of the view window, seem to expand when connecting to the smaller hexagonal openings. Besides being completed in an uncommon shape, these profound holes closed by double framework, inhibit the interior’s observation from the exterior surroundings. Watching from the outside it becomes extremely difficult to find out what happens behind those strange windows. In this project, the intimate takes refuge behind the social part of the house, and defends itself from the external view by an abstract strategy of positioning and unreferenced shape of the openings.

In this house we observe two different surveillance mechanisms. One is related to the vigilance of the interior space of the house, the other concerns the watching of the exterior surroundings. Melnikov in his studio controls the space around; from the possibility of vigilance he retains his power. In a different way, the spatial conception of the sleeping area also takes us to another kind of domestic surveillance. Although in different senses, we recognize similarities to the Jeremy Bentham’s panoptical model in both.

Panopticon is a term composed by pan (all, notion of total) and opticon (related to vision). Thereby panopticon alludes to the possibility of total observation, to all encompassing vision. The panoptical is an architectural model developed by the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century. This architectural model was invented after the English Industrial Revolution, emerging in a context defined by the urban demographical increment and the need to control social phenomena.

The panoptical model consists of an optimization of inmates’ watching, by positioning the cells along the circular perimeter of the building and implanting a surveillance tower at the center of the cylindrical construction. The inmates’ cells are closed by a grid in the confrontation to the circular patio and have windows turned to the exterior. The openness to the exterior space, as the exposition to the interior patio, provided an intense illumination of the cells’ interior, which was contrary to the darkness that prevailed in the interior of the surveillance tower. This inversion allowed a superior efficacy of the surveillance for two reasons: on one hand the vigilant would be able to watch closer the prisoners’ activities as their cells would be better illuminated, on the other hand the inmate, before the darkness of the tower, wouldn’t be able to identify the presence or the absence of the vigilant. The presence of the tower would be enough to establish the feeling of being watched.

Imprisonment, which was previously represented by oppressive constructions (such as forts), kept inmates captive for it was physically impossible to evade the structures. With the panoptical model the inmates’ detention succeeded by a different kind of subjection, which operated mostly at a psychological level. The inmate’s detention derived of the feeling of being watched which consequently paralyzed him. The panoptical model allowed a lighter construction; the cells were more illuminated and ventilated. The inmate was deprived of intimacy. He hadn’t the privilege of even a corner of his own.

At Konstantin Melnikov’s house the dining room is the main social space of the daily routine. It is the space where the family gathers to have meals and where the guests are entertained. In this particular room we can identify a hierarchy. Konstantin’s and Anna’s initials, embroidered in the cloths covering the long backs of the parent’s chairs standing in opposite sides of the table, are a clear example of this hierarchy. At the dining room the seat of each family member is clearly identified. Konstantin’s chair shows, for example, that the architect would turn his back to the street. Seating with his back to the window he would also enjoy the natural light from the south that would illuminate his family, which he could, therefore, better contemplate. In opposition, he would be darkened by his position against the light, showing, however, an involving light around his figure. Perhaps this would be enough to stage or reinforce his patriarchal presence.

Individual spaces or the daytime inhabiting

In this house there is a separation between daytime and nighttime inhabiting. While each inhabitant had an individual room dedicated exclusively to the daytime inhabiting, in the nighttime period the entire family occupied a unique bedroom. In Melnikov’s house the individual rooms are associated to daytime. This fact reveals that for this architect the individual reclusion may be related to the need of concentration or to the accomplishment of a specific activity. Resting or sleeping, that along the history of the late centuries revealed to be a reason for the search of individual seclusion turns out to be a motif of reunion in this house. The inhabitant could isolate himself with the purpose of creating or studying, but while in inactivity each individual would join the other family members in a collective bedroom. The sleep was in this house a common activity; each one would watch one another. In this mutual watching there is an implicit sense of protection as well as a sense of surveillance.

Concerning the intimate and individual inhabiting an unusual programmatic design is proposed. Melnikov designed three individual rooms at the ground floor to his wife, son and daughter, and to him he designed a studio at the upper level of the same side of the house. Both Viktor and Ludmila (son and daughter) were given two similar rooms, located near the kitchen and the mother’s room. Each of the descendants was allowed to have a space of their own, but the possibility of parents’ surveillance was assured. Both Viktor and Ludmila rooms’ are subordinate to the radial geometry suggested by the circular perimeter. The rooms’ doors are located in the narrowest side and the hexagonal windows intersect the curved facade in an opposite position. The configuration of these spaces recalls the cells’ spatial conception of the panoptical model.

The room that Konstantin designed to himself reveals very different features. He located his studio in the most secluded place of the house: distant from the street, from the ground, from the daily activity of the house and from the daytime spaces of the other family members. Moreover, on the program’s distribution, there is an association of the mundane activities with the lower floor (bounded to the ground) and the activities related to the spirit with the upper levels (closest to the sky).

Fig. 3: Present interior view of Melnikov’s studio. Source: Image courtesy of Professor Natalia Dushkina

The studio is the only room in the house that enjoys an entirely circular shape, never completed and only implicit in the other rooms. The angle of approximately 260 degrees, completed by the façade, embraces the east, north and west, allowing the inhabitant to feel the sun’s path all over the day enjoying the constancy of the reflected light from north, suitable to painting. In the 260 degrees of the façade there is a repetition of the hexagonal window on three different levels. This set of windows allows a control of the surrounding life. The peculiar silhouette and repetition of these windows, associated with the cylindrical shape of the studio seems to spatially evoke a kind of watchtower. In the studio the inhabitant is able to watch the exterior in almost all the perimeter of the room (Fig. 3).

Melnikov’s studio acts like the watchtower of the panoptical model, but unlike Bentham’s tower the studio has no cells around, this space is a tower of control that watches in a first layer the neighborhood and in the limit the city. The vigilant inhabitant sees his space illuminated with light and sights of the exterior through the panoptical windows, unlike the exterior watcher that cannot be aware of what is going on in the interior of that space. The double wall structure and the voids’ abstract repetition inhibit the view’s trespassing. From the interior, the inhabitant observes the exterior framed by the hexagonal windows. They attach the exterior views in the cylindrical wall as if they were screens. While seeing the house from the exterior, the studio’s volume shows the hexagonal windows as dark and impenetrable voids. The studio’s inhabitant watches the world from his illuminated shadow.

Nevertheless the studio inhabitant wouldn’t only have the possibility to watch the world without being watched, as he would also be able to watch his own interior world as if he was outside. Melnikov was able to climb to the mezzanine gallery, which allowed him to dominate the vision of the interior space. In this sense the creative inhabitant would be capable of seeing his work from a distant and superior point of view (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Present interior view from the mezzanine of Melnikov’s studio. Source: Image courtesy of Professor Natalia Dushkina.

The studio is devoted to the individual that searches for seclusion in order to develop his creative production. The complicity between Konstantin Melnikov and his son, Viktor, was such that it is known that they used to paint together. So, when Viktor decided to devote himself to painting, Konstantin Melnikov gave his studio to his son, transforming the living room, located at the first floor, in his new studio. It is curious that the close collaboration between Konstantin Melnikov and Viktor didn’t result in a mutual use of the working space, but in the transformation of the house’s program and the creation of a new studio, in order to create a new individual working space. Life’s paths and inhabiting practices dictated that the living room, designed to be opened to the city, ended transformed in the second Melnikov’s studio.

Sleeping: a common inhabiting

The Melnikov’s family bedroom is of particular interest. Although we can identify three beds, it stands a unique room. The three sleeping areas are delimited by two thin wooden partitions placed in a radial position without touching the exterior or the interior walls. There aren’t any doors creating effective closure between the three zones. The space’s composition suggests that, regardless of the existence of two thin walls, the space was conceived as one. From the bedroom’s entrance the inhabitant has a total vision of the space. In a different point of view, the bedroom’s composition relates, once again, to the panoptical model. The possibility of a simultaneous control of the three sleeping areas, from a unique point of observation is similar to the model invented by Bentham (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Present interior view of the family’s bedroom. Source: Image courtesy of Professor Natalia Dushkina.

The recognition of the panoptical strategy applied in the bedroom’s conception raises some questions. From the medieval habits of sharing a common room while sleeping, passing through to the need of conceiving of more intimate structures such as alcoves, to the claim of an individual room, several conditions, composition strategies and architectonical devices were developed so as to allow an intimate inhabiting of space devoted to rest and intimate relationships. In the bedroom designed by Melnikov he proposes the reunion of the sleeping space. The two wooden partition thin walls are shown as inexpressive elements that only provide the inhibition of visual contact between the inhabitants while lying in bed. Nevertheless, every sound or movement is apprehensible. Although while in bed the family members aren’t capable of seeing each other, the one who enters or leaves the room will be able to see simultaneously the three sleeping areas. To the inhabitants of this room being watched is an imminent condition.

Establishing the parallel to the panoptical model, the threshold that points the entrance into the room would correspond to the central watch tower. The compositional division of the three sleeping areas would be comparable to Bentham’s strategy of the cell’s distribution. The radial division, the positioning of the beds, the strong cell’s illumination through the hexagonal windows and the consequent darkness of the entrance point, are all facts that consolidate the correspondence of this bedroom composition to the panoptical model. The bed’s positioning, including the headboard’s orientation, reveals to the option that exposes the inhabitants the most. The sleeping area dedicated to the parents was situated in the middle of the three zones. This positioning promoted the parent’s control. They separated the son’s and daughter’s cells, watching and feeling all the descendants’ movements.

Juhani Pallasmaa (Pallasmaa, 1996) refers Melnikov’s obsession with cleaning. This author explains under this argument the architect’s option for the rounded edges between concurrent surfaces in the bedroom and the location of the dressing room in the ground floor. If the rounded edges and the corners’ banning really allowed an easier cleaning, its inexistence also promoted the continuity between surfaces, fomenting in the inhabitants a feeling of being hold by a single involving surface. Although there was a partition in three zones, the bedroom represented a single entity.

Melnikov paints every surface of the bedroom in stucco lustro painted pale golden yellow. This color and finishing, associated with a rich lightning that entered through the inhabitant’s backs by the several hexagonal windows, certainly staged a golden awakening to the new day. The morning rise, seen as a kind of rebirth, would explain the mystical staging that is implicit in the bedroom’s conception.

Besides respecting the radial composition, in the original conception1 the beds were fixed to the floor. These pieces of furniture, also drawn by the architect, appear in the room like pedestals merged to the floor through the continuity allowed by the rounded edges. The fixed position implies a structural programming of its execution. So, in this house beds are constructive matter like walls and floors. The bed as a fixed pedestal ennobles the act of sleeping; however its fixed position promotes the paralysis’ sensation of its inhabitants. In this sense the bed’s conception belongs to the whole staging and underlines the panoptical conception of the room. In this bedroom the nocturnal inhabiting converges between sleep’s consecration, subtraction of individual reclusion and consequent inexistence of individual intimacy.

Threshold space

Other activities usually associated to the bedroom’s scope where dislocated from its surroundings. Besides the daytime rooms Melnikov conceived to his wife and children, he created another room in the ground floor: the dressing room. The existence and location of this room reveals the willing of detaching the dressing activity from the bedroom. This programmatic distinction can be related to the cleaning issue previously referred, as it can also be connected to another kind of subjects. Although having an apparently secondary role in this house’s program, there is no doubt that this room’s conception reveals particular domestic inhabiting practices.

In the dressing room there are two sets of closets bordering the two radial walls. Each of these sets is distinguished by the color: the white one corresponds to the mother and daughter’s closet and the yellow one bears the father and son’s clothing. The color distinction doesn’t translate individuality but emerges as a sign of gender of the family’s members, although clothes are one of the most individual properties. The change of the proper garments to each particular situation required a visit to the dressing room. The passage from the domestic to the public, from interior to the exterior or from daytime to nighttime inhabiting, implied a transitory inhabiting of this space. In this sense, this room should be occupied amid different kinds of inhabiting, marking the daily routines. This room presents itself as a kind of threshold space, a space inhabited in a transitory manner, intercessor of different or opposing ways of inhabiting. The identification of this threshold reinforces the conviction of the opposing inhabiting natures coexisting in this house.

Between the affirmation and the exclusion of individuality

Melnikov conceives a domestic hymn to his own personality. His name’s inscription reveals the public affirmation of his individuality in a period of the collectivism’s cult under the era of the Soviet ideology. Challenging the system that had incited a common living conduct to each individual and that impelled Melnikov to the confinement of his house, the architect surely intended to underline the capital importance of each individual. However, Melnikov’s house isn’t the most favorable territory to completely experience individuality. Independently of the perversion that can be identified in the implicit will of surveillance observed in the conception of several rooms, it is important to put in context Melnikov’s patriarchal spirit, associated to his apprehensible mystical nature. As other experiments developed by other architects, the project and inhabiting of this house reveals a laboratorial character. The family’s daily life emerges, in a certain sense, as an experiment. The private life reveals to be an extension of the experience of the building of space and architecture appears as a potentially imposing discipline in the behavioral regulation, allowing or inhibiting behaviors through the spatial conformation.

Melnikov’s youth context was characterized by the belief in architecture’s possibility to enhance the human condition. Hope, revolution, or delusion, allowed the conviction in the possibility to shape, into a better being, the complex and contradictory human nature. Practically contemporaneous to the Melnikov’s house construction (1929-1930) the architect develops, as a result of a competition to a complex’s elaboration that should be built in the surroundings of Moscow called Green City, a building that he called Sonata of Sleep (Starr, 1981). In this project he explores devices and architectonic conceptions that should allow its future temporary inhabitants the possibility to enjoy a rehabilitating sleep. The importance given to the individual rest, as theme of unquestionable importance in Melnikov’s house as in the referred project, arises as a symptom of the belief that, in an Europe between wars and in a Russia in revolution, emerged implicit in the work of several modernist architects: architecture seen as a discipline that should actively participate in man’s rehabilitation.

References

Informal talk with Dr. Natalia Dushkina (Professor at the Moscow Architectural Institute) in Madrid, June 2011.

Pallasmaa, J.,1996. The Melnikov House: Moscow (1927-1929): Konstantin Melnikov. London: Academy.

Starr, S. F., 1981. Melnikov: solo architect in a mass society. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

1 Due to a legal dispute the Melnikov's archive is not available in the present moment and that is why it is not possible to publish images of the original state of the house. The photographs presented are a courtesy of Professor Natalia Dushkina, Professor at the Moscow Architectural Institute.