A participação política e as TIC no município de Porto Alegre, Brasil

Manoela Cagliari Tosin é arquiteta e urbanista, pesquisadora do Programa de Pós-graduação em Planejamento Urbano e Regional da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, onde investiga a participação da sociedade na política, com ênfase no uso de tecnologias de informação e comunicação. Atua como consultora para o poder público na elaboração de planos municipais. manoela.cagliari@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/2269367852462475

Heleniza Ávila Campos é arquiteta e urbanista, mestre em Desenvolvimento Urbano e doutora em Geografia. É docente na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul no Departamento de Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo e no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento Urbano e Regional. Atua nas áreas de territorialidades urbanas e planos diretores e é membro do Observatório das Metrópoles - Núcleo Porto Alegre. heleniza.campos@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/5667876978791233

Como citar esse texto: TOSIN, M. C.; CAMPOS, H. A. A participação política e as TIC no município de Porto Alegre, Brasil. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 21, Semestre 2, dezembro, 2020. [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus21/?sec=4&item=10&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 14 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Em meio à crise da democracia representativa e às atuais pressões do afastamento social e do teletrabalho promovidos pela pandemia da Covid-19, as Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação (TIC) são hoje reconhecidas não apenas como ferramentas oportunas, mas também como essenciais para a reprodução da sociedade. No campo político, a inclusão das TIC para articulação entre Estado e sociedade acelera práticas já em uso. Entretanto, apesar de suas potencialidades democráticas, fica o questionamento: estas novas tecnologias são efetivamente usadas pelo Estado para este fim ou apenas reproduzem as mesmas práticas excludentes? O presente artigo aborda a questão do uso de TIC pelo Estado para participação política, analisando o caso da Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre (PMPA), no Brasil, e investigando o uso crescente de TIC pelo governo municipal para efetiva participação política no planejamento e gestão urbana. O período avaliado inicia-se em 1999 (ano de lançamento do sítio eletrônico oficial) e vai até os dias atuais, observando-se a ampliação e modernização das plataformas em razão do avanço da pandemia. Procura-se, assim, traçar um panorama geral da evolução de emprego das TIC pelo Estado em sua esfera municipal, com foco na participação política, ao longo da história recente.

Palavras-chave: TIC, Governo Municipal, Participação Política, Porto Alegre

1 Introdução

O avanço das Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação (TIC) alterou rápida e profundamente todas as dimensões da vivência humana, principalmente nas três últimas décadas. Atualmente, a sociedade não pode ser vista sem suas ferramentas tecnológicas, o que torna imprescindível a identificação dos reflexos da inserção das TIC no cotidiano. Esse desenvolvimento tecnológico abriu possibilidades para a transformação do sistema político praticado, que é alvo de inúmeras críticas, principalmente devido à baixa participação política do povo em um modelo que se diz democrático.

A atuação do Estado durante a pandemia da Covid-19 tem sido de vital importância na gestão do uso da cidade e de seus espaços públicos, na informação dos casos – divulgados diariamente pelos municípios e pela Secretaria da Saúde –, na regulamentação do teletrabalho e no distanciamento social. O Rio Grande do Sul foi um dos Estados que mais rapidamente definiu estratégias em resposta à crise gerada pela pandemia. O primeiro caso de Covid-19 no Estado foi confirmado em 10 de março de 2020 na Região Metropolitana de Porto Alegre (SOARES, et al., 2020). Apenas dois dias depois, o governo estadual publicou o primeiro decreto (Decreto Estadual n° 55.115, de 12 de março de 2020) com medidas de prevenção nos órgãos públicos, alterado, posteriormente, para todos os servidores do Estado (Decreto Estadual n° 55.118, de 16 de março de 2020).

A alternativa de home office, globalmente utilizada durante a pandemia, é um exemplo de como as TIC têm alterado de forma direta e profunda as relações de trabalho locais, a mobilidade nas cidades e o acesso a plataformas e aplicativos através do uso das redes informacionais. Considera-se, assim, que entender mecanismos de interação do Estado com a sociedade via meios remotos de comunicação é um fator de grande relevância para se pensar a perspectiva política e participativa no atual contexto de vida das populações.

O presente artigo aborda o uso de TIC pelo Estado para participação política. Mais especificamente, procura investigar se o uso crescente de TIC pela Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre (PMPA), que teve origem na década de 1990, aumentou efetivamente a participação política no planejamento e gestão urbana. Para isso, serão identificados marcos históricos relacionados às principais plataformas digitais da PMPA e também examinada a forma de participação política possibilitada por estes meios de comunicação.

A PMPA foi selecionada por possuir amplo histórico de uso das TIC e por se destacar pelas suas iniciativas participativas, possuindo, como principal referência, o Orçamento Participativo. Implementado no final da década de 1980, a experiência do Orçamento Participativo em Porto Alegre demonstrou que espaços reais de participação e deliberação da esfera civil podem, sim, se articular com a política representativa (SANTOS, 2002, p. 65). Já o início do período temporal se justifica por se tratar da época de popularização da Internet no Brasil e de lançamento dos primeiros portais governamentais, considerado como o primeiro marco de uso das TIC pelos governos municipais. As técnicas utilizadas foram pesquisa bibliográfica, pesquisa documental e navegação nas plataformas digitais.

Este artigo contém cinco partes: a primeira aborda a crise do modelo de democracia representativa e o surgimento dos modelos participativos. A segunda discorre sobre a revolução tecnológica e as expectativas em relação ao modelo de democracia digital. A terceira se refere à participação política no contexto brasileiro. A quarta parte trata do caso da PMPA, e a quinta demonstra uma síntese geral dos conteúdos abordados e discute os resultados obtidos com o estudo de caso, de forma a delinear conclusões sobre a investigação realizada.

2A crise da representação e a ascensão de modelos participativos

A democracia é um regime de governo no qual a soberania é exercida pelo povo. As variações na forma de participação política – entendida aqui como participação da sociedade civil na esfera política – indicam a existência de diferentes modelos democráticos, conforme será visto a seguir. O atual modelo hegemônico de democracia se estruturou no decorrer do século XX, onde a questão democrática se compunha fundamentalmente de dois elementos principais: o da desejabilidade como forma de governo e o das condições estruturais da democracia (SANTOS, 2002, p. 39-40). Em resposta a este debate, destacou-se como alternativa o modelo representativo, que basicamente tenderia a equilibrar a tensão entre o governo democrático e a sociedade capitalista. Segundo Santos (2002, p. 59, grifo do autor):

Essa estabilização ocorreu por duas vias: pela prioridade conferida à acumulação de capital em relação à redistribuição social e pela limitação da participação cidadã, tanto individual, quanto coletiva, com o objetivo de não “sobrecarregar” demais o regime democrático com demandas sociais que pudessem colocar em perigo a prioridade da acumulação sobre a redistribuição.

O modelo representativo foi estruturado com base na separação entre representantes e representados, em nome da preservação do sistema político. Nesse modelo, as eleições são cruciais, pois através delas a sociedade poderia exercer o controle sobre as lideranças políticas, sendo a participação limitada a escolha dos líderes, de forma a preservar o sistema e obter o máximo de rendimento na tomada de decisões (PATEMAN, 1992, p. 25-26). A minoria de dirigentes (esfera política) concentra o poder decisório e uma maioria de dirigidos (esfera civil) possui poder decisório limitado ao processo eleitoral de escolha dos dirigentes. Portanto, na democracia representativa, a sociedade civil – considerada como o centro dos regimes democráticos – cumpre apenas o papel de autorizar e não de governar. Souza (2018, p. 324-325) critica esse modelo afirmando que, na democracia representativa, há alienação da decisão e liberdade do representante para decidir em nome dos demais.

O crescente distanciamento entre sociedade civil e Estado, estimulado pela democracia representativa, culminou na contestação da ênfase dada à representação no sistema político. Essa insatisfação resultou na crise deste modelo hegemônico e no surgimento de iniciativas de renovação do modelo democrático, principalmente a partir de 1970. Os modelos contra-hegemônicos de participação resultantes, denominados de democracia participativa, caracterizam-se pelo reconhecimento da pluralidade humana e pela ruptura de tradições consolidadas (SANTOS, 2002, p. 51), contestando a representação política como única alternativa e suscitando maior abertura para a participação da sociedade nas decisões políticas. Para Pateman (1992, p. 60-62), este modelo possui as seguintes características: indivíduos e instituições não podem ser considerados isoladamente; a sustentação do sistema político só seria possível pela função educativa da participação política; ênfase nos impactos positivos da participação política, como o efeito integrativo e a maior aceitação pelas decisões tomadas; e princípio de igualdade política como igualdade de poder na determinação das decisões.

Em síntese, os modelos participativos – contrariamente à democracia representativa – defendem a aproximação da sociedade civil da esfera política, sendo a participação vista como essencial para a sustentação do sistema político. Entretanto, os modelos participativos também foram alvo de críticas como as apontadas por Silva (2009, p. 49), na qual indica que há uma visão demasiadamente positiva sobre a natureza das relações humanas e ausência de alternativas para solucionar a questão da ‘escala’. O autor também adverte para o perigo de gerar um tipo ideal e hegemônico de cidadão participante nestes modelos, o que pode distorcer a participação para uma tirania da maioria. Segundo o autor, tais modelos, portanto, podem acirrar conflitos existentes no embate discursivo das diferentes visões.

Conforme aponta Silva (2009, p. 53), os modelos participativos não são necessariamente excludentes ou incompatíveis com a democracia representativa, pois mantêm determinados princípios vinculados à ideia-base de democracia. Embora autores como Santos (2002, p. 75-76) defendam a articulação entre as democracias representativa e participativa como solução para a crise política, a democracia participativa enfrenta dificuldades de inserção no modelo hegemonicamente praticado. De acordo com Souza (2018, p. 325), “tentam-se corrigir distorções e problemas do sistema representativo mediante a injeção de uma dose de democracia direta”, que muitas vezes tem seus propósitos subvertidos. Dentre essas distorções, destacam-se os canais de comunicação e informação entre o Estado e a Sociedade.

3A revolução tecnológica e o modelo de democracia digital

Para Santos (2013, p. 24), o espaço geográfico, na atualidade, constitui um meio técnico-científico-informacional, no qual ciência, tecnologia e informação estão na base de todas as formas de utilização e funcionamento do espaço. Castells (2018, p. 109) afirma que a revolução da tecnologia de informação iniciou-se na década de 1970. No entanto, seus marcos fundamentais ocorreram duas décadas depois com a expansão da Internet e a explosão da comunicação sem fio (CASTELLS, 2018, p. 18). A Internet representa a base da comunicação na atualidade. Dentre as suas características, é possível destacar a “penetrabilidade, descentralização multifacetada e flexibilidade” (CASTELLS, 2018, p. 439) como fatores responsáveis pela sua difusão. Já a comunicação sem fio é a forma predominante de comunicação, o que pode ser explicado pela flexibilidade de uso e possibilidade de conectividade perpétua que a rede fornece (p. 23).

No Brasil, identificam-se três períodos temporais relacionados à disseminação das TIC: inserção (década de 1990), na qual o aprimoramento das tecnologias e das infraestruturas gradualmente reduziram o custo e melhoraram os serviços prestados; popularização (década de 2000), quando o número de computadores e celulares aumentou significativamente1, juntamente com o número de domicílios com acesso à Internet2; e mediação digital de tudo (a partir de 2010), quando houve um boom na disseminação dos dispositivos portáteis3, a popularização dos aplicativos de serviços e a generalização do acesso à Internet nos domicílios4.

A disseminação destas tecnologias fez emergir uma nova forma de comunicação mundial por redes, que se constituem na nova morfologia social, produtiva e política da sociedade (CASTELLS, 2018, p. 553). Emerge, assim, um modo informacional de desenvolvimento vinculado a práticas cotidianas que, ao mesmo tempo em que participam da vida de cada indivíduo, também sofrem rápidas e contínuas transformações.

Durante a década de 1990, instituições do mundo inteiro se empenharam para aderir às TIC de forma a se integrar no novo sistema e garantir sua posição de poder. Neste período, as TIC foram vistas como possibilidade a ser aproveitada para a desejável aproximação da sociedade civil com o Estado, e por viabilizar o exercício da democracia direta no mundo atual (SOUZA, 2018, p. 332). Surge, assim, o modelo de democracia digital, que pode ser caracterizado como:

[...] qualquer forma de emprego de dispositivos (computadores, celulares, smartphones, palmtops, ipads...), aplicativos (programas) e ferramentas (fóruns, sites, redes sociais, mídias sociais...) de tecnologias digitais de comunicação para suplementar, reforçar ou corrigir aspectos das práticas políticas e sociais do Estado e dos cidadãos, em benefício do teor democrático da comunidade política. (MAIA, GOMES, MARQUES, 2017, p. 25-26)

O teor democrático atribuído ao modelo digital estaria relacionado a aspectos que poderiam ser mediados por tecnologias digitais: a garantia e/ou aumento da liberdade de expressão, da transparência pública ou accountability, das experiências de democracia direta, dos instrumentos e oportunidades de participação do cidadão, do pluralismo e representação das minorias e de consolidação dos direitos de indivíduos. (MAIA, GOMES, MARQUES, 2017, p. 26).

No Brasil, as primeiras propostas de Governo Eletrônico surgiram no âmbito federal em 1995, durante o primeiro mandato de Fernando Henrique Cardoso. O foco inicial foi na melhoria da gestão do Estado e apenas a partir de 2003, mais explicitamente durante o Governo de Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, houve maior preocupação com o uso das TIC para participação política e ampliação da cidadania (PRADO, 2009, p. 74-81). Entretanto, as ações do Estado não têm, de fato, priorizado ou criado estratégias para aproximar o cidadão da política e dos seus mecanismos de funcionamento. Segundo pesquisa realizada pelo Centro Regional de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação (CETIC.BR., 2020), apenas 68% dos cidadãos brasileiros utilizaram o governo eletrônico em 2019. Predominou a busca por serviços e informações, sendo que apenas 5% dos entrevistados escreveu em fóruns ou consultas, enquanto 6% participou de votações e enquetes. Soma-se a isso que, em 2020, o Brasil atingiu a média de dois dispositivos digitais por habitante (MEIRELLES, 2020), o que demonstra a impressionante inserção das TIC na sociedade brasileira nas três últimas décadas, sendo a Internet e a comunicação sem fio a preferência entre os meios de comunicação.

Diante destes dados, é possível afirmar que as potencialidades democráticas das TIC não estão sendo devidamente aproveitadas. Pesquisas sugerem que a esfera política, apoiada em sistemas digitais, de alguma forma reflete a política tradicional, não garantindo instantaneamente uma esfera de discussão pública justa, representativa, relevante, efetiva e igualitária (GOMES, 2005a, p. 221). Apesar de não haver consenso quanto às possibilidades da democracia digital, visto que o uso das TIC se apresenta atualmente insuficiente para aproximar sociedade e Estado, parece haver concordância de que este modelo pode contribuir para a participação política. Segundo Wolton (2012, p. 184), a comunicação não é apenas técnica, mas depende da ordem cultural e social e a democracia digital tem limitações quanto à capacidade de resolver os problemas sociais e políticos. Atualmente, as oportunidades democráticas das TIC não estão sendo devidamente aproveitadas pelo Estado, conforme será demonstrado a seguir.

4Processos participativos, TIC e os graus de participação política

Considera-se que, em uma sociedade democrática, a participação política é um direito inalienável de todo cidadão. Conforme defendem Innes e Booher (2004), os modelos de democracia participativa, na efetiva participação política, geram reflexos positivos tanto para o Estado quanto para a sociedade civil, através da aproximação dos planejadores às comunidades e dos cidadãos à realidade político-econômica. Um processo democrático legítimo, em geral, promove o crescimento da capacidade cívica dos participantes; aprendizagem mútua e capital social, que pode ampliar a compreensão e aceitação das decisões tomadas; o comprometimento pelos resultados, assim como a responsabilidade dos atores participantes; e o aprimoramento das decisões.

Para garantir os ganhos sociais proporcionados pela inserção da sociedade civil na esfera política, o Estado tende a promover processos participativos que, em sua maior parte, têm sido presenciais, através de audiências públicas, plenárias, conferências, congressos, assembleias, seminários. Apesar das vantagens – como maior nivelamento e aprendizagem dos participantes – também possui sérias e históricas limitações (INNES, BOOHER, 2004; SOUZA, 2018), como, por exemplo, necessidade de deslocamento para locais e horários fixos; intimidação do ambiente de exposição dos dados e propostas, seja pela excessiva linguagem técnica dos planejadores sobre os conteúdos em discussão, seja pela representação dominante de grupos hegemônicos; definição prévia de temas que nem sempre revelam a diversidade de problemas e questões da diversidade dos atores envolvidos com o processo. Tais situações acabam por resultar em propostas geralmente não qualificadas e uma ausência de feedback dos participantes.

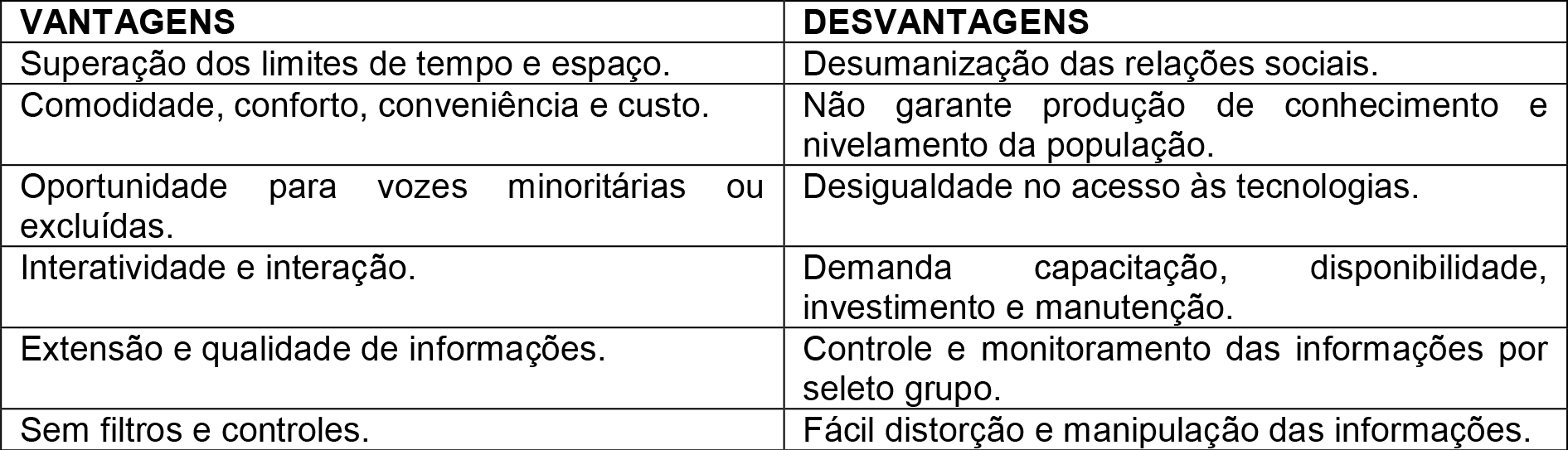

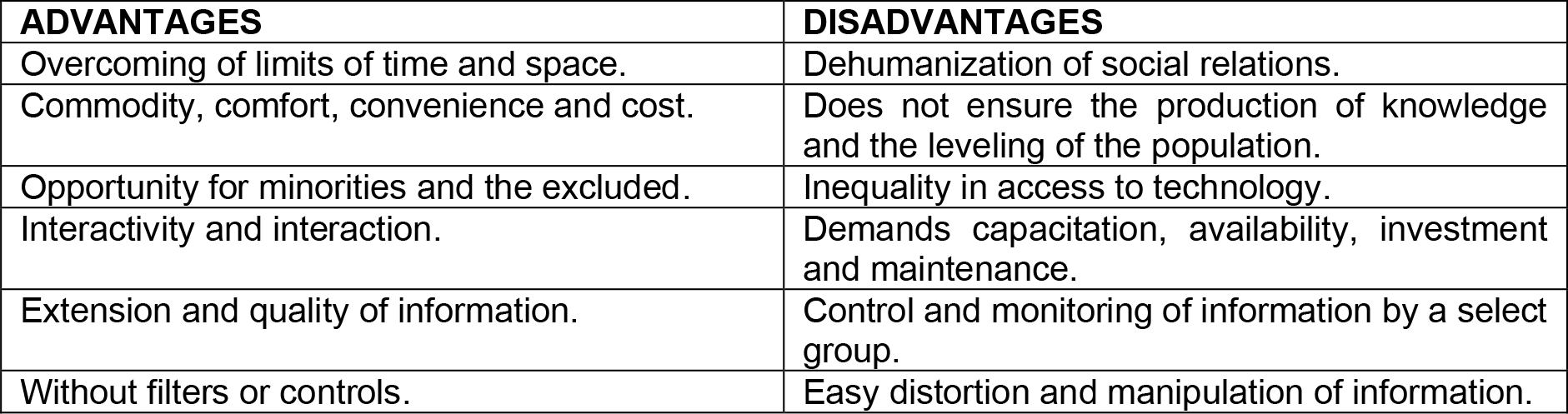

A interação remota entre Estado e cidadão geralmente ocorre através de sítios eletrônicos, que hoje já representam, no Brasil, o principal canal de comunicação entre Estado e sociedade civil (MAIA, GOMES, MARQUES, 2017, p. 121). Os processos participativos mediados pelas TIC5 apresentam características que ajudam a superar as limitações identificadas nos métodos presenciais. Contudo, é importante destacar que os métodos remotos também possuem desvantagens. No Quadro 1 estão especificadas as principais características dos processos participativos remotos (GOMES, 2005b, p. 66-74).

Quadro 1: Características dos processos participativos remotos. Fonte: Elaborado pelas autoras, 2020.

Ambos os métodos participativos (presencial e remoto) possuem qualidades e deficiências. Logo, não há um método mais eficiente do que o outro. A maior parte das publicações, que trata das dificuldades enfrentadas para participação política, parece assumir que os métodos participativos não são utilizados corretamente (INNES, BOOHER, 2004, p. 420). Os esporádicos processos participativos realizados pelo Estado – muitas vezes apenas como cumprimento legal – acabam não atraindo ou satisfazendo a população, resultando em processos com ínfima representatividade da sociedade ou com predominância de determinados grupos organizados.

A participação política varia em graus de acordo com os processos realizados pelo Estado e esta diferença acaba por refletir-se no modelo democrático praticado. Souza (2018, p. 338) aponta que a participação política geralmente existente nas democracias representativas seria a participação consultiva (restringida a apenas ouvir os envolvidos) enquanto nas democracias participativas a participação política seria deliberativa (na qual os envolvidos tomam, de fato, as decisões).

Arnstein (1969, p. 216) já apontava que existia uma grande diferença entre passar por um ritual vazio de participação e ter o real poder necessário para afetar o resultado do processo. Sua Escada de Participação6 (ARNSTEIN, 1969, p. 217) foi adaptada para a realidade brasileira por Souza (2018, p. 207), que propôs uma Escala de Avaliação – também com oito graus – que varia da não-participação à participação autêntica. Quanto aos processos participativos mediados pelas TIC, Gomes (2005a, p. 218-219) desenvolveu uma Escala de Democracia Digital que possui cinco graus.

+ 1. o Estado disponibiliza serviços públicos no ambiente virtual para acesso do cidadão, modelo também chamado de cidadania delivery;

+ 2. o Estado utiliza o ambiente virtual para consultar o cidadão sobre determinados assuntos políticos;

+ 3. o Estado adquire alto nível de transparência para com o cidadão;

+ 4. corresponde à combinação dos modelos de democracia representativa e participativa, com o Estado mais aberto a participação popular e a esfera civil com oportunidade para decidir em alguns temas;

+ 5. representa o modelo de democracia direta, na qual a esfera política desaparece, sendo a própria esfera civil responsável pelas decisões políticas.

Mesmo com a promessa de que o uso das TIC pelo Estado garantiria uma maior aproximação da sociedade civil com a esfera política, a escala de Gomes (2005a) demonstra que as democracias digitais também podem apresentar níveis baixíssimos de participação política. Silva (2005, p. 458) se baseou nesta Escala de Democracia Digital para analisar os portais das capitais brasileiras e identificou a existência dos três primeiros graus, sendo o primeiro grau o único em via de consolidação, apresentando características predominantemente informativas.

Na avaliação de Silva (2005, p. 465), o modelo de democracia digital é limitado à disponibilização de informação, ou, em segundo plano, na prestação de serviços públicos em formato delivery. Outro aspecto importante apontado pelo autor é a ausência de informações claras, ou mesmo indícios, que indiquem o efetivo emprego das TIC para participação política na decisão pública, muitas vezes utilizado de forma complementar às atividades presenciais. O autor, por fim, aponta a subutilização das TIC para desenvolvimento de uma política mais democrática, e a similaridade nos aspectos estruturais de seu emprego pelos governos das capitais brasileiras.

Desta forma, em relação ao panorama brasileiro, as potencialidades do uso das TIC em processos democráticos parecem não ser devidamente aproveitadas. A utilização destas novas ferramentas tecnológicas pelo Estado requer uma mudança estrutural das práticas governamentais para a efetiva inserção da sociedade civil na esfera política, conforme será demonstrado no caso da PMPA.

5A democracia digital e a PMPA

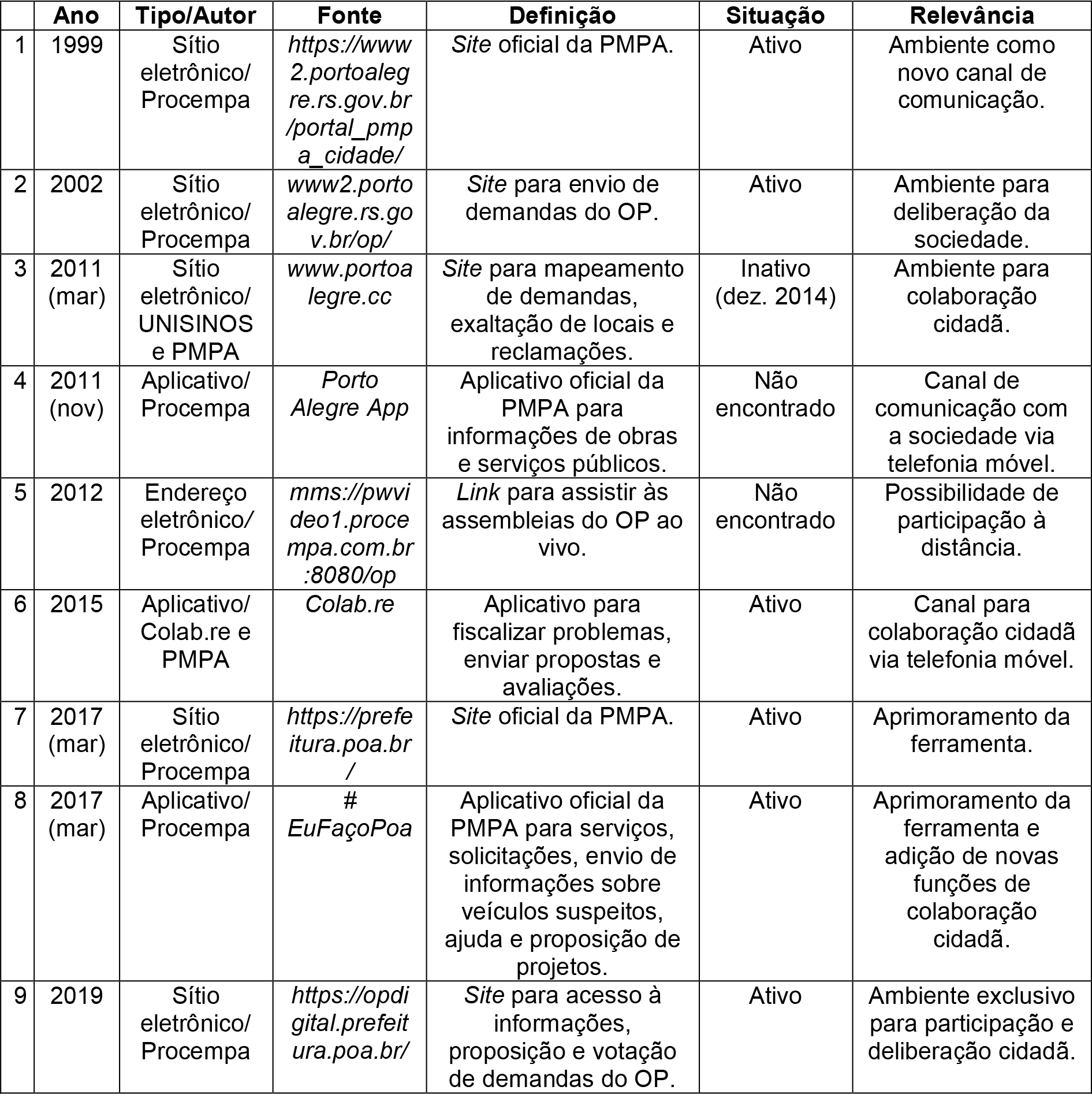

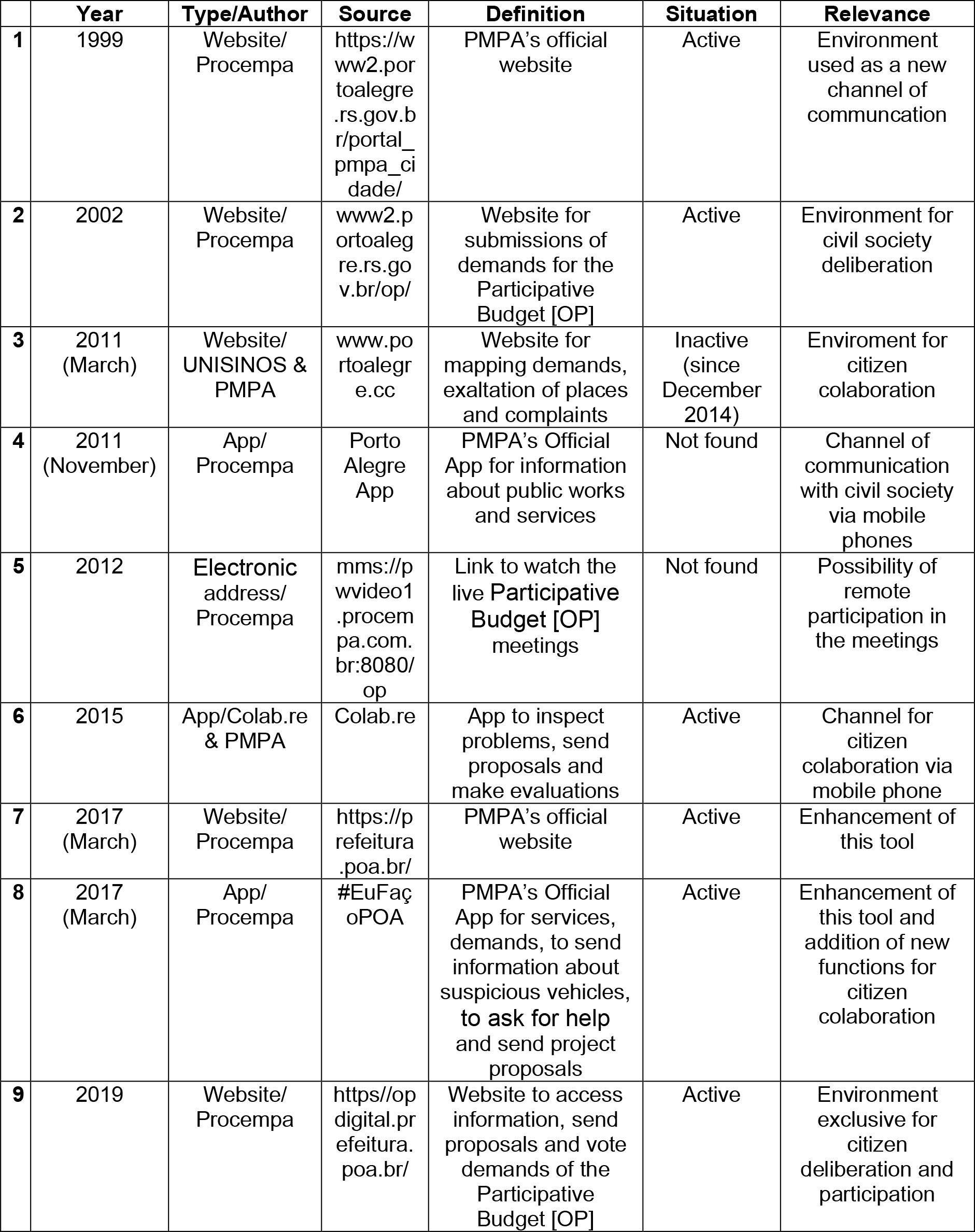

Porto Alegre é uma das capitais brasileiras que procura explorar essas novas ferramentas digitais de práticas democráticas, possuindo amplo histórico na utilização de TIC pelo governo municipal. Para atingir os objetivos deste artigo, foram selecionados alguns marcos históricos considerados relevantes em relação ao uso da TIC pela PMPA para abertura de canais de diálogo com a sociedade. Ao todo, foram selecionados nove marcos históricos que abrangem as duas últimas décadas, cujo marco inicial corresponde ao lançamento do website oficial da PMPA na rede.

Quadro 2: Marcos históricos do uso de TIC pela Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre. Fonte: Elaborado pelas autoras a partir de fontes diversas, 2020.

A partir das informações dispostas no Quadro 2, a análise será dividida em dois períodos temporais relacionados com o perfil político da PMPA. No primeiro período – de 1999 a 2004 – houve a introdução das TIC no governo municipal, que se resumiram à criação dos sítios eletrônicos. A Companhia de Processamento de Dados de Porto Alegre (PROCEMPA), fundada em 1977, foi o órgão responsável pelo desenvolvimento destas plataformas, visando proporcionar mais um canal de diálogo com a população. Já no segundo período – de 2005 até os dias de hoje – houve ampliação das plataformas e a inclusão de aplicativos7, em paralelo aos sítios eletrônicos. O período coincide com o boom da disseminação dos dispositivos portáteis no Brasil, conforme já mencionado. Ressalta-se a realização de parcerias da PMPA com outras instituições para o desenvolvimento dos canais digitais.

Como pode ser visto no Quadro 2, a maior parte das plataformas analisadas permanece disponível para acesso e, em resumo, estes marcos selecionados estão relacionados: à evolução das plataformas oficiais da PMPA (marcos 1, 4, 7 e 8); à inserção de ferramentas digitais para colaboração cidadã (marcos 3 e 6); e à inserção de ferramentas digitais para deliberação8 cidadã (marcos 2, 5 e 9). Para fins deste artigo, a análise se limitou à evolução dos sítios eletrônicos, por representarem os principais canais de comunicação da PMPA com a sociedade e por possibilitarem uma análise da evolução destas plataformas, visto que ambas permanecem disponíveis para acesso. Para isso, os conteúdos disponíveis na página inicial das plataformas foram classificados conforme os graus de democracia digital de Gomes (2005a), especificados anteriormente.

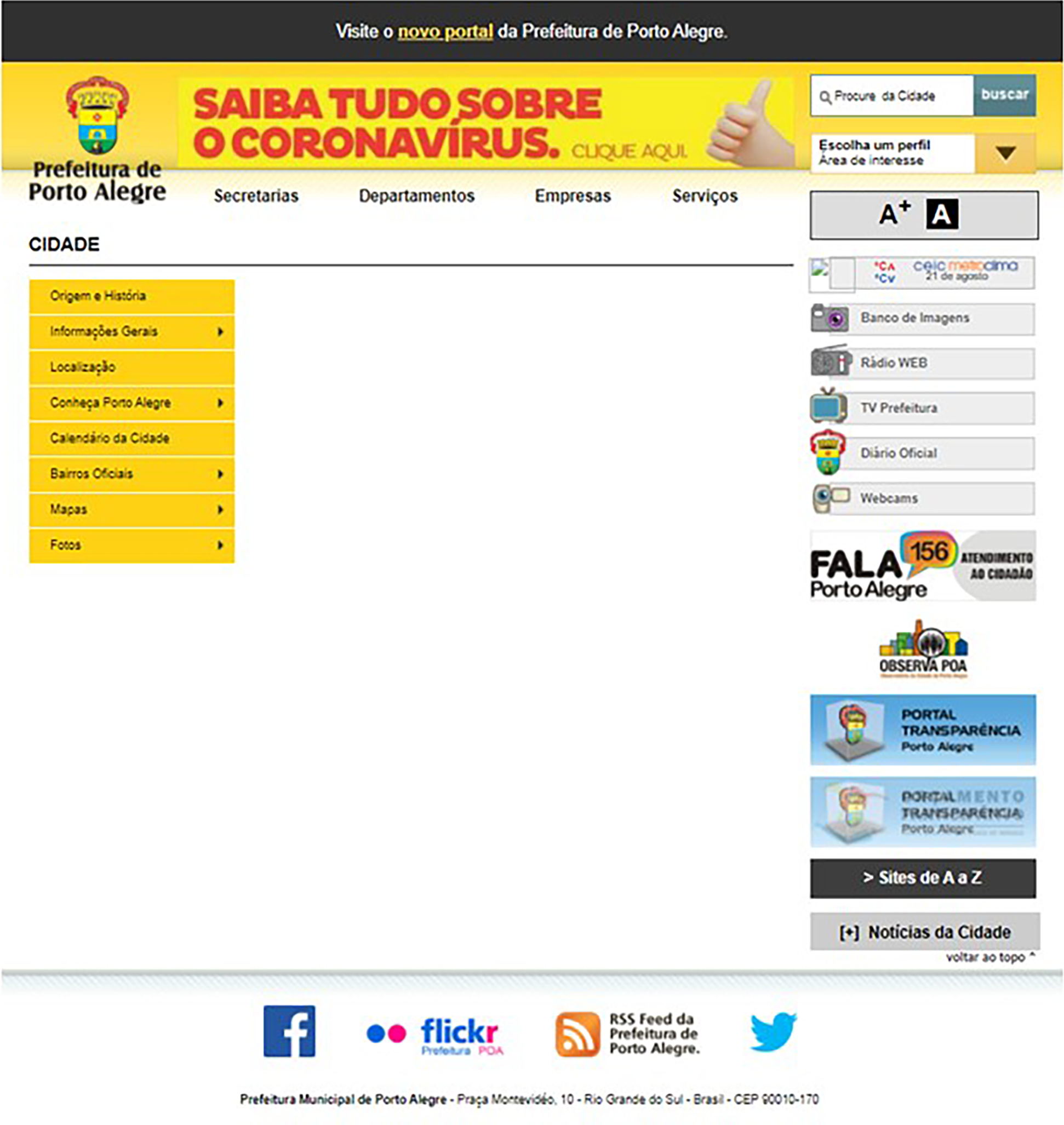

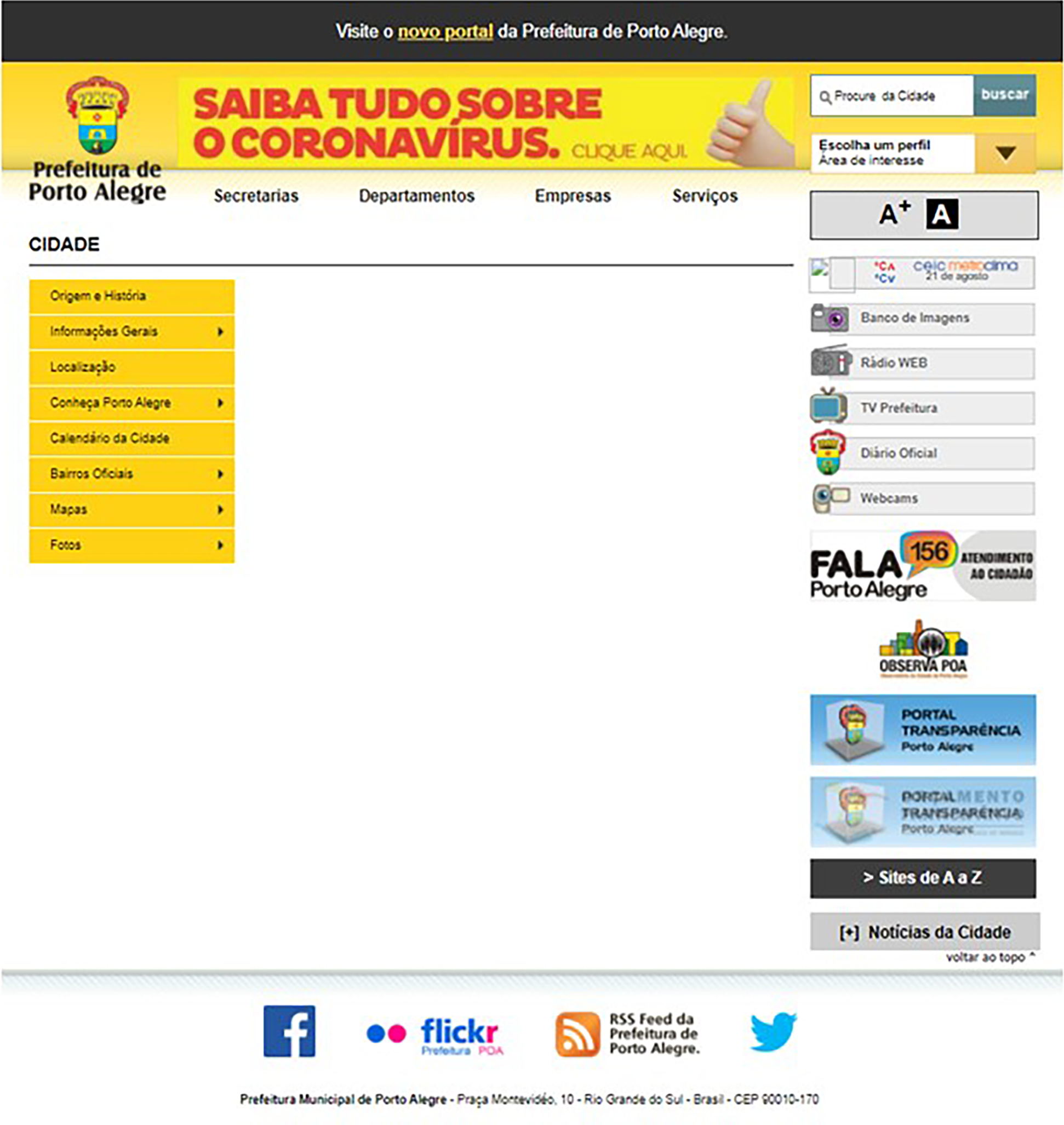

Segundo informações obtidas junto à PROCEMPA, o sítio eletrônico da PMPA foi lançado no ano de 1999 e modernizado entre os anos de 2003 e 2004. Esta versão permaneceu vigente até o ano de 2019 (Figura 1), sendo esta a versão analisada por Silva (2005), no estudo anteriormente mencionado.

Fig. 1: Página inicial do sítio eletrônico da Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre, versão vigente até o ano de 2019. Fonte: Imagem capturada pelas autoras, 2019

Após análise da página inicial, constata-se que esta versão do sítio eletrônico da PMPA permanece no formato informacional constatado por Silva (2005), de primeiro grau, de caráter informativo – representado pela disponibilização de informações sobre o município, instituições e outros canais de comunicação oficiais – e focado na prestação de serviços – pela variedade de opções disponibilizada. O segundo grau permanece fragilizado. A consulta ao cidadão disponível é secundarizada, indireta e bastante limitada. Há um espaço de atendimento ao cidadão – no qual são realizados apenas protocolos de serviços – e disponibilizado acesso direto às informações sobre o orçamento participativo. Não foi encontrado espaço para manifestação da sociedade e não havia destaque para consultas públicas. Já o terceiro grau, relacionado à transparência do Estado, parece estar mais estruturado, porém é restrito ao cumprimento de exigências legais de disponibilização de documentos da gestão fiscal – através do Diário Oficial e Portal de Transparência e Acesso à Informação –, não havendo instrumentos que facilitem a compreensão da prestação de contas pelo público.

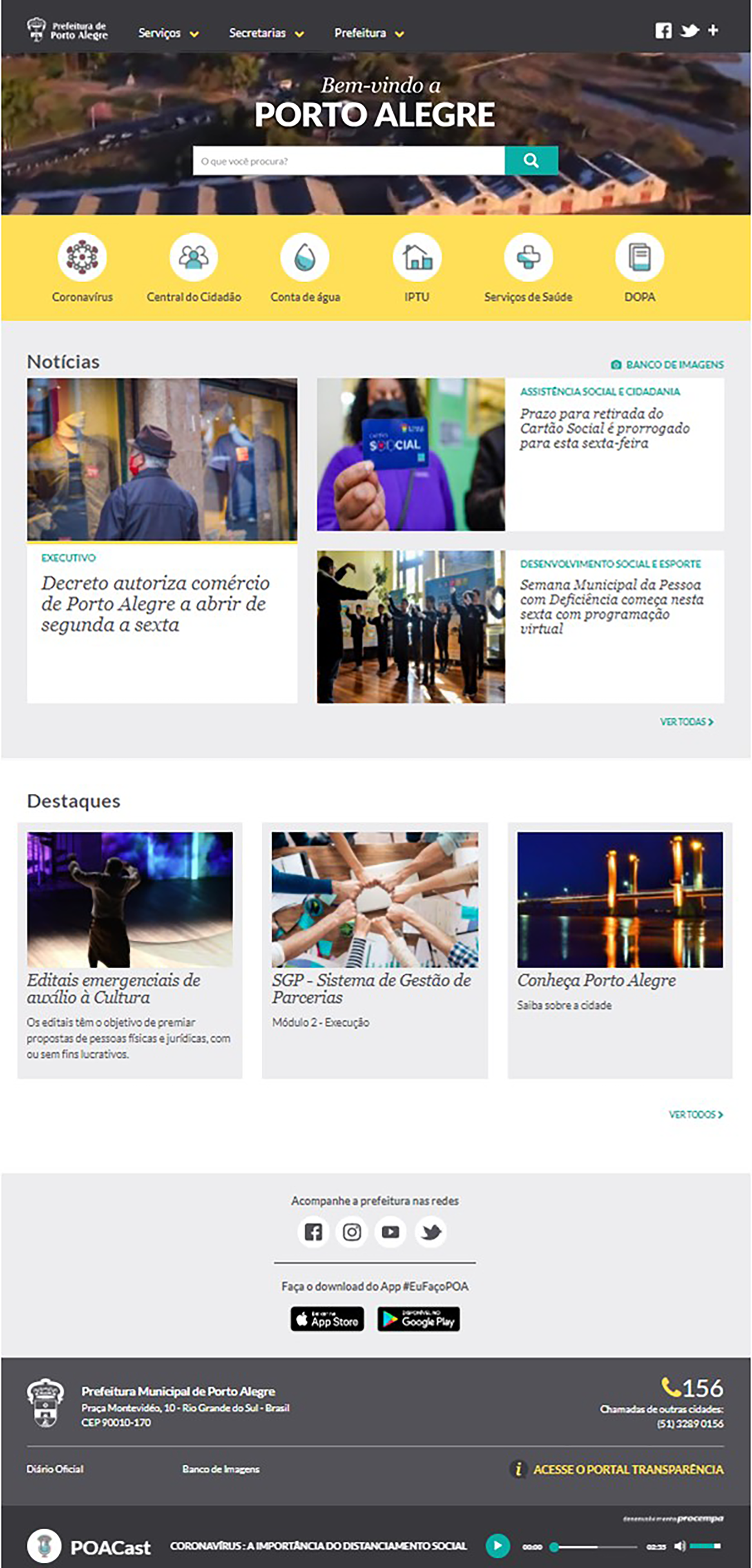

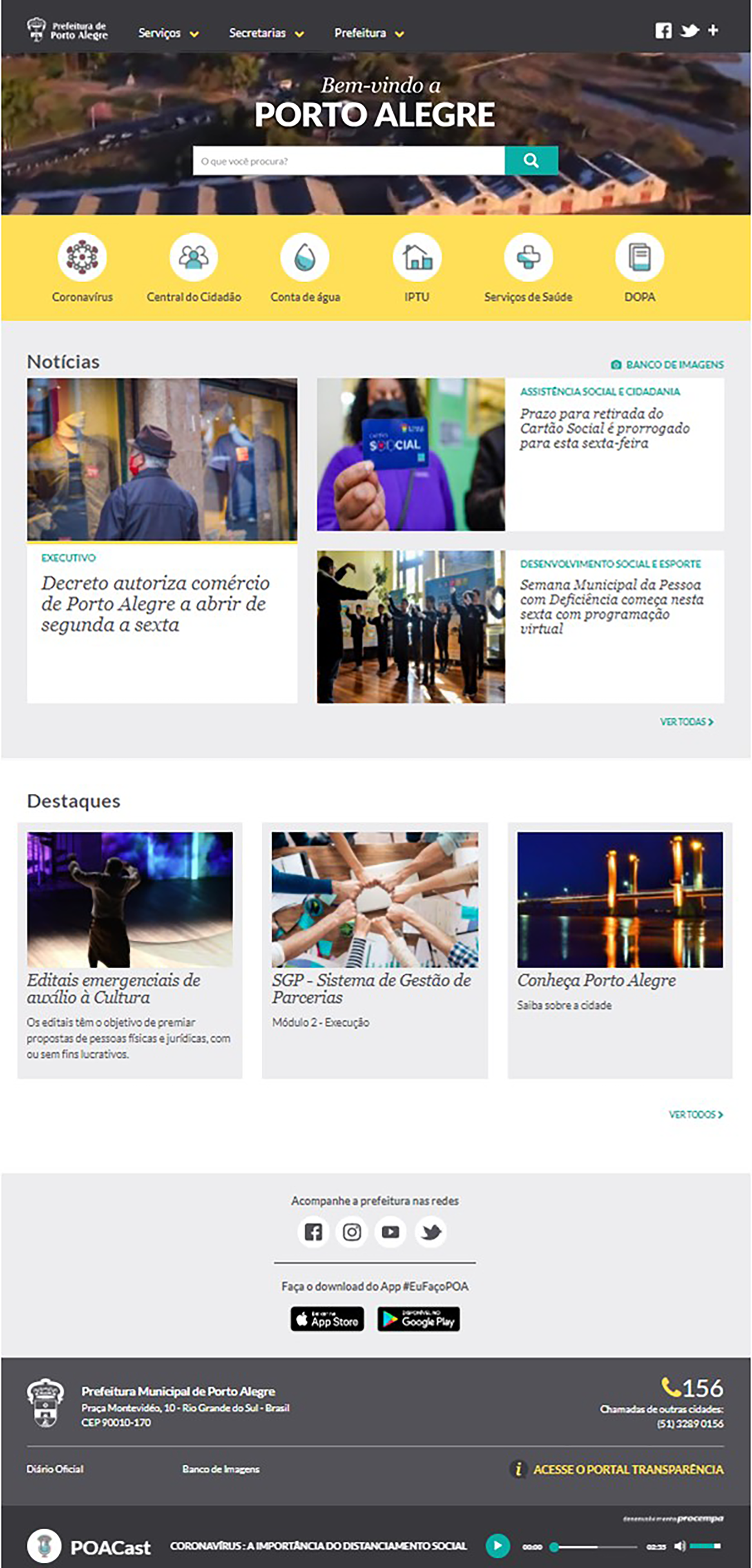

Conforme mencionado, uma nova versão do sítio eletrônico da PMPA foi lançada em 21 de março de 2017, juntamente com o aplicativo para dispositivos móveis #EuFaçoPoa. Após um período de teste que durou aproximadamente dois anos, a nova versão (Figura 2) está em funcionamento.

Fig. 2: Página inicial do sítio eletrônico da Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre, versão vigente a partir de 2020. Fonte: Imagem capturada pelas autoras, 2020. Disponível em: https://prefeitura.poa.br/. Acesso em: 23 out 2020.

Segundo a PMPA, a nova versão do sítio eletrônico visa ampliar a transparência e facilitar o acesso aos serviços municipais. O enfoque na prestação de serviços foi comprovado pela análise realizada na sua página inicial, juntamente com seu caráter informativo – pela posição de destaque e predominância dada. Entretanto, o nível de transparência não obteve destaque – foram mantidas as mesmas opções de acesso. A democracia digital de primeiro grau permanece predominante, bem como mantém a fragilidade do segundo grau e os aspectos relacionados ao terceiro grau. De forma geral, apenas os aspectos visuais foram modernizados, permanecendo a lógica estrutural do sítio eletrônico antigo.

Analisada a evolução dos sítios eletrônicos oficiais da PMPA, constata-se que pouco ou nada mudou das abordagens iniciais. Apesar de alguns avanços pontuais, a estrutura não se alterou. O teor predominantemente informativo, característico da democracia digital de primeiro grau, manteve-se no período analisado. Apesar dos recentes esforços de modernização e inserção de novas ferramentas, a postura relutante do governo municipal perante a inserção da participação política permanece, demonstrando que o simples fato da utilização das TIC para abertura de novos canais de comunicação com a sociedade não garante práticas mais democráticas.

Em relação ao contexto da pandemia do Covid-19 vivenciado no Rio Grande do Sul, as informações sobre novos casos, número de contaminados e de leitos disponíveis são muitas e rapidamente divulgadas. No entanto, há diferenças entre os dados disponibilizados nos sítios eletrônicos da Secretaria de Saúde do Estado e dos municípios, que muitas vezes não mantém um histórico dos dados registrados.

Outro fator importante no atual período de pandemia é que o isolamento social dificulta as manifestações sociais e políticas e as ações isoladas em comunidades vulneráveis, seja por parte do Estado ou de outros atores sociais. Em 2020, observou-se um aumento de pressões políticas, jurídicas ou mesmo policiais do Estado e de setores da sociedade com interesses particulares sobre o acesso à terra, afetando diretamente a vida de comunidades que possuem habitação em situação vulnerável. Essas situações de conflito, cada vez mais recorrentes, acabam por repercutir no campo político, implicando no questionamento sobre os limites da democracia participativa.

6Considerações finais

Neste artigo, foram discutidos os diferentes graus de participação política praticados em sistemas democráticos. Em meio à crise da democracia representativa – na qual a participação política é limitada – e com o surgimento de modelos contra-hegemônicos de democracia participativa – que defendem um maior envolvimento da sociedade nas decisões políticas – emerge o modelo de democracia digital, visto como uma oportunidade para a desejável transformação do cenário político, ainda hegemonicamente representativo.

Com a acelerada disseminação das TIC e o surgimento de uma nova ordem de comunicação estruturada em rede, ocorre uma profunda transformação social, política e econômica. Neste contexto, o Estado começa a utilizar as TIC como um novo canal de comunicação com a sociedade. Entretanto, apesar de haver consenso de que as TIC possuem potencial para a desejável aproximação da sociedade civil com a esfera política, na prática não houve mudança. Desde as primeiras propostas de Governo Eletrônico, no Brasil, pesquisas revelam que há pouca participação política através de recursos digitais (CETIC.BR., 2020; GOMES, 2005a), demonstrando que a democracia digital acaba por refletir as deficiências da política representativa.

De fato, o uso das TIC não garante uma prática mais democrática e ambos os processos participativos praticados – presenciais eremotos – possuem vantagens e desvantagens. A utilização de ambas as formas merece permanente atualização e ajuste aos avanços e transformações da própria sociedade. Dessa forma, é urgente um espaço específico dentro do sistema de gestão pública, tanto na esfera municipal como estadual, de monitoramento das ferramentas, dos modelos existentes e de novas práticas experimentadas no país e no exterior.

Autores como Gomes (2005a) e Silva (2005) consideram que o Estado, em seus processos de planejamento, não obtém uma participação política efetiva. Segundo análise realizada, a PMPA não é exceção. Apesar de ser pioneira em iniciativas participativas e de possuir amplo histórico de uso das TIC, a PMPA pouco avançou em relação à democracia digital. Em análise que abrangeu o período temporal de 1999 aos dias atuais, verifica-se que o uso de TIC limita-se aos sítios eletrônicos, criados ainda no final do século XX, ou seja, durante os mandatos do Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) no âmbito municipal. Além disso, há poucos aplicativos para dispositivos móveis, introduzidos pela PMPA a partir da década de 2010.

As plataformas utilizadas são majoritariamente desenvolvidas por órgão municipal (PROCEMPA), demonstrando que a PMPA possui infraestrutura própria, capacidade e facilidade para introdução das TIC nas suas atividades políticas. A repetição das mesmas funções em diferentes plataformas evidencia que nenhuma destas opções é vista como um canal efetivo de diálogo entre a PMPA e a sociedade. Suas funções predominantes são informar e prestar serviços à população, características da democracia digital de primeiro grau de Gomes (2005a), estando os graus mais elevados fragilizados ou ausentes. Essas plataformas poderiam ser melhor exploradas para inserção da participação política.

As reflexões aqui apresentadas em relação ao uso de TIC em processos participativos por parte do Estado ganham um significado mais abrangente em tempos de pandemia, apontando para possibilidades de serviços a serem realizados remota e digitalmente e disponíveis de forma permanente, como atendimentos online, consulta a informações de diferentes setores do Estado e acompanhamento de alguns processos via Internet. A fragilidade aqui refere-se ao acesso e às interfaces entre as plataformas e os usuários, sobretudo os que se encontram em faixas de renda e de idade com mais dificuldade de uso dessas ferramentas. A virtualidade resultante do meio técnico-científico-informacional também coloca em questão o sentido do que é real ou não, abrindo espaço para criação, por exemplo de falsas notícias (fake news).

Por fim, afirma-se que o uso de TIC pela PMPA parece ainda pouco contribuir, no momento, para a aproximação da sociedade na esfera política, refletindo o modelo democrático praticado, no qual há restritos espaços para participação política e deliberação social. Carece maior investigação dos motivos e vantagens para a duplicação de práticas políticas no ambiente digital.

Os investimentos do Estado em meios digitais são predominantemente voltados para ampliação e agilidade na prestação de serviços e para divulgação de propaganda própria, sendo pouco aproveitadas as possibilidades de seu uso para participação política da sociedade, mesmo com todas as vantagens que apresenta. Como tornar vantajoso para o Estado o aproveitamento das potencialidades democráticas das TIC parece ser uma questão que ainda merece ser aprofundada para que, conforme desejado, se amplie a participação da sociedade nas decisões políticas.

Referencias

ARNSTEIN, S. R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, v. 35, n. 4, p. 216-224, 1969. DOI 10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388>. Acesso em: 14 jul. 2020.

CASTELLS, M. A Sociedade em Rede. 19. ed. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2018.

CETIC.BR. Microdados Pesquisas TIC. São Paulo: Centro Regional de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação, 2020. Disponível em: <https://www.cetic.br/pt/microdados/>. Acesso em: 30 jul. 2020.

GOMES, W. A democracia digital e o problema da participação civil na decisão política. Revista Fronteiras - estudos midiáticos, São Leopoldo, v. 7, n. 3, p. 214-222, set./dez. 2005a.

GOMES, W. Internet e participação política em sociedades democráticas. Revista FAMECOS, Porto Alegre, v. 2, n. 27, p. 58–78, ago. 2005b. Disponível em: <http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/revistafamecos/article/view/3323/2581>. Acesso em: 8 jul. 2020.

INNES, J. E.; BOOHER, D. E. Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century. Planning Theory & Practice, v. 5, n. 4, p. 419-436, dez. 2004. Disponível em: <https://escholarship.org/content/qt4gr9b2v5/qt4gr9b2v5.pdf>. Acesso em: 13 jul. 2020.

MAIA, R. C. M.; GOMES, W.; MARQUES, F. P. J. A. Internet e participação política no Brasil. 1. ed. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2017.

MEIRELLES, F. S. Uso da TI Tecnologia de Informação nas Empresas: pesquisa anual do FGVcia - 31a edição. São Paulo: FGV/EASP, 2020.

PATEMAN, C. Participação e teoria democrática. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1992.

PRADO, O. Governo eletrônico, reforma do Estado e transparência: o programa de governo eletrônico do Brasil. 2009. Tese (Doutorado em Administração Pública e Governo) – Escola de Administração e Empresas, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, São Paulo, 2009.

SANTOS, B. S. Democratizar a democracia: os caminhos da democracia participativa. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2002.

SANTOS, M. Técnica, Espaço, Tempo: Globalização e meio técnico-científico-informacional. 5. ed. São Paulo: EDUSP, 2013.

SILVA, S. P. Estado, democracia e Internet: requisitos democráticos e dimensões analíticas para a interface digital do Estado. 2009. Tese (Doutorado em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporâneas) – Faculdade de Comunicação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, 2009.

SILVA, S. P. Graus de participação democrática no uso da Internet pelos governos das capitais brasileiras. Opinião Pública, Campinas, v. 11, n. 2, p. 450-468, out. 2005.

SOARES, P. R. R., AUGUSTIN, A. C., CAMPOS, H. A., BEM, J. S., SIQUEIRA, L. F., LAHORGUE, M. L., WAISMANN, M., UGALDE, P. A., MARX, V. A pandemia de Covid-19 no Rio Grande do Sul e na metrópole de Porto Alegre. As Metrópoles e a Covid-19: Dossiê nacional. Rio de Janeiro: Observatório das Metrópoles, 2020. Disponível em: <https://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Dossi%C3%AA-N%C3%BAcleo-Porto-Alegre_An%C3%A1lise-Local_Julho-2020.pdf>. Acesso em: 7 out. 2020.

SOUZA, M. L. Mudar a cidade: uma introdução crítica ao planejamento e à gestão urbanos. 12. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2018.

WOLTON, D. Internet, e depois? Uma teoria crítica das novas mídias. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2012.

1 Em 2008, o número de computadores atingiu a proporção de um a cada quatro habitantes e a proporção de celulares de três para cada quatro habitantes (MEIRELLES, 2020).

2 A porcentagem de domicílios com acesso à Internet mais que dobrou entre os anos de 2005 e 2010 – de 13% a 27%, respectivamente (CETIC.BR., 2020).

3 Em 2020, há uma média de 1,6 dispositivos portáteis por habitante (MEIRELLES, 2020).

4 Em 2019, 93% dos domicílios possuíam celular e mais da metade dos domicílios possuíam acesso à Internet (71%), sendo 99% dos acessos realizados através de celular (CETIC.BR., 2020).

5 Como chats, fóruns, debates, petições, questionários, enquetes, votações.

6 Composta por oito degraus, na qual quanto mais alto o degrau, maior o poder decisório do cidadão.

7 Software para dispositivos móveis.

8 A deliberação compreende a participação que envolve tomada de decisão, aspecto que diferencia da colaboração cidadã.

Political participation and the ICT in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil

Manoela Cagliari Tosin is an Architect and Urbanist, a researcher at the Graduate Program in Urban and Regional Planning at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where she investigates the participation of society in politics, with an emphasis on the use of Information and Communication Technologies. She works as a consultant to the public authorities in the formulation of municipal master plans. manoela.cagliari@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/2269367852462475

Heleniza Ávila Campos is an Architect and Urbanist, has a master's degree in Urban Development and a Ph.D. in Geography. She teaches at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in the Department of Urbanism at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, and in the Postgraduate Program in Urban and Regional Planning. She works in the area of urban territorialities and master plans and is a member of the Metropolises Observer - Porto Alegre section. heleniza.campos@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/5667876978791233

How to quote this text: Tosin, M. C., Campos, H. A., 2020. Political participation and the ICT in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil. Translated from Portuguese by Thirzá Amaral Berquó and Laura Cristina Gay Reginin. V!RUS, 21, December. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus21/?sec=4&item=10&lang=en>. [Accessed: 14 July 2025].

Abstract

Amidst a crisis of representative democracy, and under the pressure from both social distancing and remote work brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are recognized nowadays not only as opportune tools, but also as essential features for social reproduction. In the political field, the inclusion of ICT for the articulation between the state and society accelerates the practices already in use. Nevertheless, despite its democratic potential, the question remains: are such new technologies effectively used by the state for this purpose, or are they used only to reproduce the same excluding practices? The present paper examines the use of ICT by the state for political participation, by analyzing the case of the Porto Alegre City Government [Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre - PMPA], in Southern Brazil. It focuses on the increase of the use of ICT by the city government to ensure political participation in city planning and urban administration. The analysis comprises the period from 1999 (year of the launch of the official website) to the present day, looking into the enhancement and modernization of the platforms due to the advancement of the pandemic. Therefore, the paper aims to sketch a general panorama of the evolution of the usage of ICT by the state in the municipal sphere in recent history, focusing on political participation.

Palavras-chave: ICT, City Government, Political Participation, Porto Alegre, Brazil

1 Introduction

The advancement of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) changed fast and deeply all dimensions of human living experience, mainly in the last three decades. Nowadays, contemporary society cannot be considered without its technological tools, making it crucial to identify the repercussions of ICT insertion in daily life. Such technological development opened up possibilities for the transformation of the current political system, which is much criticized, especially due to low political participation of the people in a supposedly democratic model.

The performance of the government during the COVID-19 pandemic has been crucial in the administration of the city and its public spaces’ uses, by informing about the number of cases – released daily both by local governments and the Health Secretariat –, and by regulating remote work, and social distancing. The Rio Grande do Sul was one of the fastest states to define strategies to respond to the crisis generated by the pandemic. The first case of COVID-19 in this state was confirmed on March 10th, 2020 in the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre, the capital city of Rio Grande do Sul state (Soares, et al., 2020). Two days later, the state government published its first decree (State Decree # 55115, from March, 12th, 2020), prescribing preventive measures for public agencies, later altered to reach all civil workers (State Decree # 55118, from March, 16th, 2020).

The alternative of the home office, globally adopted during the pandemic, is an example of how the ICT have been changing in a direct and profound way the local work relationships, the mobility in the cities, and the access to platforms and applications through the use of informational networks. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of interaction between state and society by remote means of communication is of great relevance to thinking about the political and participatory perspective in the current context of populations’ lives.

This paper examines the use of ICT by the state to promote political participation. More specifically, it aims to investigate if the increase in the use of ICT by the Porto Alegre City Government [Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre – PMPA], which started in the 1990s, effectively improved the political participation in urban administration and planning. To this end, historical marks related to the main digital platforms of PMPA will be identified, as well as the form of political participation enabled by these means of communication.

PMPA was selected because of its large history of ICT use and for its outstanding participatory initiatives, its main reference being the participatory Budget [Orçamento Participativo]. Implemented at the end of the 1980s, the experience of the participatory Budget in Porto Alegre demonstrated that real spaces of participation and deliberation in the civil sphere can be articulated with representative politics (Santos, 2002, p. 65). The initial frame of this time period is justified, because it is the period when the Internet gained popularity in Brazil and when the first government websites in the country were launched, thus being considered the first mark of ICT usage in Brazilian city governments. For this research, the techniques utilized were bibliographical and documentary research and digital platform navigation.

This paper has five parts. The first one approaches the crisis of the representative democracy model and the emergence of participatory models. The second part examines the technological revolution and the expectations in relation to the model of digital democracy. The third refers to political participation in the Brazilian context. The fourth part analyses the case of PMPA. The fifth shows a synthesis of the subjects examined and discusses the results obtained with the case study, drawing conclusions from the investigation performed.

2The crisis of representation and the ascension of participatory models

Democracy is a government regime in which sovereignty is exerted by the people. The variations in the form of political participation (understood here as the participation of civil society in the political sphere) point to the existence of different democratic models, as will be seen below. The current hegemonic democracy model was structured during the 20th century when the democratic issue was composed essentially of two main elements: the desirability as a government form and the structural conditions of democracy (Santos, 2002, p. 39-40). In response to this debate, the representative model stood out as an alternative, which would basically tend to equilibrate the tension between the democratic government and the capitalist society. According to Santos:

This stabilization occurred in two ways: the priority conferred to the capital accumulation in relation to social redistribution and the restriction of citizen participation, be it individual or collective, with the objective of not ‘overloading’ too much the democratic regime with social demands which could put in danger the priority of accumulation over redistribution. (Santos, 2002, p. 59, highlighted by the author, our translation)

The representative model was structured with a basis on the separation between the representatives and the represented, on behalf of the preservation of the political system. In this model, the elections are crucial, because it is through them that society can exert control over the political leadership, the participation is limited to the choosing of the leaders, as a way to preserve the system and obtain the maximum efficiency in decision making processes (Pateman, 1992, p. 25-26). The minority of rulers (political sphere) concentrates the decision-making power and the majority of ruled (civil sphere) has a decision-making power limited to the election process to choose the rulers. Thus, in a representative democracy, civil society (considered as the center of democratic regimes) performs only the role of authorizing, and not of governing. Souza (2018, p. 324-325) criticizes this model, affirming that, in a representative democracy, there is an alienation of decision and freedom for the ruler to decide for others.

The increasing distancing between civil society and the state, stimulated by representative democracy, culminated in the contestation of the emphasis given to representation in the political system. This dissatisfaction resulted in the crisis of this hegemonic model and the emergence of initiatives for the renovation of the democratic model, mainly from the 1970s onwards. The resulting counter-hegemonic models of participation, known as participatory democracy, are characterized by the acknowledgment of human plurality and the rupture of consolidated traditions (Santos, 2002, p. 51), challenging political representation as to the only alternative, and evoking a greater openness for the participation of society in political decisions. For Pateman (1992, p. 60-62), this model has the following features: individuals and institutions cannot be considered separately; the maintenance of the political system could only be possible by the educative function of political participation; the emphasis on the positive aspects of political participation, as the integrative effect and the wider acceptance of the decisions taken; and the principle of political equality as equality of power in the determination of decisions.

In summary, the participatory models (contrary to representative democracy) defend the approximation of civil society to the political sphere, where participation is seen as essential to the maintenance of the political system. However, participatory models were also the target of criticism such as the ones pointed by Silva (2009, p. 49), who indicates that there is an overly positive view on the nature of human relations and the absence of alternatives to solve the question of ‘scale’. The author also cautions about the danger of generating an ideal and hegemonic type of citizen participation in these models, which can distort participation into a majority tyranny. According to the author, these models, thus, could stir up the existing conflicts in the discursive clash of the different views.

As shown by Silva (2009, p. 53), participatory models are not necessarily excluding or incompatible with representative democracy, because they maintain certain principles connected to the basic idea of democracy. Although authors such as Santos (2002, p. 75-76) defend the articulation between representative and participatory democracies as a solution to the political crisis, participatory democracy faces difficulty in its insertion in the hegemonically practiced model. According to Souza (2018, p. 325, our translation), “it is tried to correct distortions and problems of the representative system through the injection of a dose of direct democracy”, which many times has its purposes subverted. Among those distortions, the communication and information channels between state and society stand out.

3Technological revolution and digital democracy model

To Santos (2013, p. 24), the geographical space, at the present time, constitutes a technical-scientific-informational medium, in which science, technology, and information form the basis of all the forms of use and functioning of space. Castells (2018, p. 109) asserts that the information technology revolution began in the 1970s. However, its fundamental milestones occurred two decades later with the expansion of the Internet and the outburst of wireless communication (Castells, 2018, p. 18). The Internet represents the basis of current communication. Among its features, it is possible to highlight its “penetrability, multifaceted decentralization and flexibility” (Castells, 2018, p. 439, our translation) as the key factors responsible for its dissemination. On the other hand, wireless communication is the main form of communication, which can be explained by its flexibility of use and the perpetual connection it offers (Castells, 2018, p. 23).

In Brazil, three periods related to the dissemination of ICT can be identified: their insertion (the 1990s), in which the enhancement of the technologies and the infrastructure gradually reduced the costs and improved the services delivered; their popularization (2000s), when the number of personal computers and cellphones increased significantly1, as well as the number of households with Internet access2; and the all-encompassing digital mediation (from 2010s onwards), when there was a boom in mobile devices dissemination3, the popularization of service apps, and the generalization of Internet access in households4.

The dissemination of these technologies caused the emergence of a new way of world communication via networks, which constitutes the new social, productive and political morphology of society (Castells, 2018, p. 553). In this way, emerged a new informational mode of development bound to daily practices, which simultaneously participates in the life of each individual and also suffers fast and continuous transformations.

During the 1990s, institutions worldwide committed to adhere to the ICT as a way of integrating themselves into the new system and guarantee their position of power. In this period, the ICT were seen as a way to reach the desirable approximation between civil society and the state, and enable the exercise of direct democracy in the present world (Souza, 2018, p. 332). The model of digital democracy arises, which can be characterized as:

[...] any form of usage of devices (personal computers, cellphones, smartphones, palmtops, ipads…), apps (programs) and tools (forums, sites, social networks, social media…) of digital technologies of communication to supplement, reinforce or correct aspects of political and social practices of the state and of its citizens, in benefit of the democratic content of the political community. (Maia, Gomes, Marques, 2017, p. 25-26, our translation)

The democratic content attributed to the digital model could be related to aspects which could be mediated by digital technologies: the assurance and/or increase in freedom of speech, in public transparency or accountability, in the experiences of direct democracy, in the instruments and opportunities of citizen participation, in pluralism and the representation of minorities, and in the consolidation of rights of individuals (Maia, Gomes, Marques, 2017, p. 26).

In Brazil, the first proposals of Electronic Government arose in the federal sphere in 1995, during the first mandate of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The initial focus was the enhancement of state administration and it was just in 2003, more explicitly during the government of Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, that there was a greater concern in the use of ICT for political participation and the enlargement of citizenship (Prado, 2009, p. 74-81). However, the actions of the state have not, in fact, prioritized or created strategies to bring citizens closer to politics and its operating mechanisms. According to a research conducted by the Regional Center of Studies for the Development of Information Society [Centro Regional de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação] (Cetic.br 2020), only 68% of Brazilian citizens utilized the electronic government in 2019. The predominance was in the search for services and information, and only 5% of the interviewed had written on forums or consultations, while 6% had engaged in polls and surveys. To such data, it can be added that Brazil reached the average of two digital devices per inhabitant in 2020 (Meirelles, 2020), which shows the impressive insertion of ICT in Brazilian society in the last three decades, with the Internet and wireless communication being the preferred means of communication.

With these data, it is possible to assert that the democratic potential of ICT are not being properly utilized. Research suggests that the political sphere, supported by digital systems, somehow reflects traditional politics, not instantaneously ensuring a sphere of fair, representative, relevant, effective and equalitarian public discussion (Gomes, 2005a, p. 221). Despite the absence of consensus about the possibilities of digital democracy, given that the use of ICT is currently insufficient to draw near society and state, there seems to be some agreement that this model can contribute to political participation. According to Wolton (2012, p. 184), communication is not just technical, it depends on cultural and social order, and digital democracy has limitations regarding its capacity to solve social and political problems. Currently, the democratic opportunities brought by the ICT have not been duly used by the state, as it will be demonstrated below.

4Participatory processes, ICT and degrees of political participation

It is considered that, in a democratic society, political participation is an inalienable right of every citizen. In accordance with Innes and Booher (2004), participatory democracy models, in an effective political participation, generate positive reflexes for both the state and the civil society, through the approximation of planners to the communities and of citizens to the political-economic reality. In general, a legitimate democratic process promotes the growth of the civic capacity of its participants; mutual learning and social capital, which can broaden the comprehension and acceptance of the decisions taken; commitment for the results, as well as the responsibility of the participating actors; and the improvement of decisions.

To ensure the social gains brought by the insertion of civil society in the political sphere, the state tends to promote participatory processes which, in its majority, have been presential, through public hearings, plenary sessions, conferences, congresses, assemblies, and seminars. Despite its advantages (such as a greater leveling and learning of the participants), it also has serious and historical limitations (Innes, Booher, 2004; Souza, 2018), such as, for example, the need to go to places and in set times; the intimidation generated by the environment of exposure of data and proposals, both from the excessive use of technical language by the planners for the subjects of the discussion and from the dominant representation of hegemonic groups; the previous definition of themes that not always reflect the diversity of problems and the questions generated by the diversity of actors involved in the process. These situations result in proposals that are generally not qualified and an absence of feedback from the participants.

The remote interaction between state and the citizen usually occurs through electronic websites, which represent, in present-day Brazil, the main communication path between the state and the civil society (Maia, Gomes, Marques, 2017, p. 121). The participatory processes mediated by ICT5 present characteristics which help overcome the limitations identified in in-person methods. However, it is important to highlight that remote methods also have disadvantages. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of remote participatory processes (Gomes, 2005b, p. 66-74).

Table 1: Characteristics of remote participatory processes. Source: Elaborated by the authors, 2020.

Both participatory methods (presential and remote) have qualities and deficiencies. Thus, there is no method more efficient than the other. The majority of publications which examine the difficulties faced in political participation, seem to assume that the participatory methods are not used correctly (Innes, Booher, 2004, p. 420). The sporadic participatory processes performed by the state (many times just as legal requirement) end up not attracting or satisfying the population, resulting in processes with minimal society representativeness or with predominance of certain organized groups.

The political participation varies in degrees according to processes performed by the state and this difference ends up being reflected in the democratic model practiced. As noted by Souza (2018, p. 338), the political participation which generally exists in representative democracy would be the consultative participation (restricted just to hearing the participants), while in participatory democracy political participation would be deliberative (in which the participants, in fact take, the decisions).

Arnstein (1969, p. 216) already pointed to the existence of a great difference between going through an empty ritual of participation and having the real power needed to affect the result of the process. His Ladder of Citizen Participation6 (Arsntein, 1969, p. 217) was adapted to the Brazilian context by Souza (2018, p. 207), who proposed a Scale of Evaluation (also with eight degrees) that varies from nonparticipation to authentic participation. Concerning the participatory processes mediated by ICT, Gomes (2005a, p. 218-219) developed a Scale of Digital Democracy with five degrees:

+ 1. the state offers public services in the digital environment with access for the citizen, a model also called delivery citizenship;

+ 2. the state uses the virtual environment to consult citizens about certain political issues;

+ 3. the state acquires a high level of transparency with its citizens;

+ 4. corresponds to a combination of the representative democracy and participatory democracy models, with the state more open to popular participation and the civil sphere with the opportunity to decide on some topics;

+ 5. represents the model of direct democracy, in which the political sphere disappears and the civil sphere is responsible for political decisions.

Even with the promise that the use of ICT by the State would ensure a closer relationship between the civil society and the political sphere, the scale of Gomes (2005a) demonstrates that digital democracies can also present extremely low levels of political participation. Silva (2005, p. 458), based on the Scale of Digital Democracy, analyzed the websites of the Brazilian capitals, and identified the existence of the first three degrees, the first degree being the only one on its way to consolidation, presenting predominantly informative features.

In the evaluation carried on by Silva (2005, p. 465), the digital democracy model is limited to the availability of information or, secondarily, to the offer of public services in delivery format. Another important aspect highlighted by the author is the absence of clear information, or even traces of the effective use of ICT for political participation in public decisions, many times used in a complementary manner to in-person activities. The author points to the underutilization of ICT for the development of a more democratic politics, and to the similarity in the structural aspects of its use by the governments of the Brazilian capitals.

Therefore, regarding the Brazilian panorama, the potential for the use of ICT in democratic processes do not appear to be properly exploited. The utilization of these new technological tools by the state requires a structural change in government practices for the effective insertion of civil society in the political sphere, as will be examined in the case study of PMPA.

5Digital democracy and the PMPA

Porto Alegre is one of the Brazilian capitals which seeks to explore these new digital tools for democratic practices, having an extensive history of ICT utilization by the city government. To achieve the goals of this article, there was the selection of some historical marks considered relevant regarding the use of ICT by the PMPA to open channels of dialogue with civil society. In total, nine historical marks were selected, which cover the last two decades. The initial mark corresponds to the launch of the PMPA official website in the WWW.

Table 2: Historical marks of the use of ICT by the Porto Alegre City Government [Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre – PMPA]. Source: Elaborated by the authors, from several sources, 2020.

From the information available on Table 2, the analysis will be divided in two time periods related to the political profile of PMPA. In the first period (from 1999 to 2004), there was the introduction of ICT in the city government, which was limited to the creation of websites. The Data Processing Company of Porto Alegre [Companhia de Processamento de Dados de Porto Alegre - PROCEMPA], founded in 1977, was responsible for the development of these platforms, aiming to provide another channel for dialogue with the population. In the second period (from 2005 to present time), there was the expansion of the existing platforms and the inclusion of apps7, alongside the websites. This period coincides with the boom of mobile devices’ dissemination in Brazil, as it was already mentioned earlier. It is important to highlight the partnership of the PMPA with other institutions for the development of digital channels.

As it can be seen in Table 2, the majority of the analyzed platforms remains available for access. These selected marks are related to: the evolution of the official platforms of PMPA (marks 1, 4, 7 and 8); the insertion of digital tools for citizen collaboration (marks 3 and 6); and the insertion of digital tools for citizen deliberation8 (marks 2, 5 and 9). For this paper, the analysis was limited to the evolution of websites, because they represent the main communication channels between PMPA and the society, and because they enable an analysis of their evolution, as they are still available for access. Therefore, the contents available on the main page of each platform were classified according to Gomes’ degrees of digital democracy (2005a), specified above.

In accordance with information provided by PROCEMPA, the PMPA website was launched in 1999 and modernized between 2003 and 2004. This version remained available online until 2019 (Figure 1). This was the version Silva (2005) analyzed in his study mentioned earlier.

Fig. 1: Main page of the Porto Alegre City Government website [Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre – PMPA], online version available until 2019. Source: Image captured by the authors, 2019.

After the analysis of the main page, it can be concluded that this version of the PMPA website remains in the informational format mentioned by Silva (2005), of the first degree, with mainly informative character (represented by the availability of information about the city, its institutions, and other official communication channels) and focused in the delivery of services (for the variety of options provided). The second degree remains fragile. The available citizen consulting is secondary, indirect, and very limited. There is a space for citizen attendance – in which only service protocols are performed – and direct access to information about the Participatory Budget [Orçamento Participativo] is provided. A space for demands and manifestation of the society was not found and there was no highlight to public consultations. The third degree, related to state transparency, seems to be more structured, but it is restricted to the fulfillment of legal requirements of availability of financial administration documents (through the Official Journal [Diário Oficial], the Transparency Portal, and the Access to Information), not having any instruments to facilitate the comprehension of public accountability by the citizens.

As it was mentioned, a new version of the PMPA website was launched on March, 21st, 2017, along with the mobile device app #EuFaçoPoa. After a trial period which lasted more or less two years, the new version (Image 2) is currently available.

Fig. 2: Main page of the Porto Alegre City Government website [Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre – PMPA], the version available from 2020 onwards. Source: Image captured by the authors, 2020.

According to the PMPA, the new version of the website aims to broaden transparency and to facilitate access to city services. The focus on service delivery can be verified through the analysis of the main page, because of its informational character (by its prominent position and its predominance). However, the level of transparency had no update (the same access options were maintained). The first-degree digital democracy remained predominant, as well as the fragility of the second degree and the aspects related to the third degree. In general, only the visual aspects were modernized, but with the permanence of the structural logic of the old website.

Through the analysis of the evolution of the PMPA official websites, it is concluded that little or nothing changed from the first approaches. Despite some punctual advancements, the structure has not changed. The predominantly informational content, characteristic of first-degree digital democracy, remained in the period analyzed. Despite the recent modernization efforts and the inclusion of new tools, the reluctant posture of the city government pertaining to the insertion of political participation remains, showing that the simple fact of using ICT to open new channels of communication with society does not ensure more democratic practices.

Related to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic experienced in the Rio Grande do Sul, the information about the new cases, the number of contaminated people, and available hospital beds are many and rapidly shared. However, there are differences between the data provided by the websites of the State Health Secretariat [Secretaria de Saúde do Estado] and the data provided by the cities’ websites, which many times do not keep a historic record of registered data.

Another important factor in the present pandemic period is that social distancing complicates social and political protests and the isolated actions in vulnerable communities, from both the state or other social actors. In 2020, there has been an increase in political, legal, and even police pressure from the state and from sectors of society with particular interests regarding access to land, directly affecting the lives of communities that have households in vulnerable situations. These conflict situations, more and more recurrent, end up causing repercussions in the political field, implicating in the questioning of the limits of participatory democracy.

6Final considerations

In this paper, the different degrees of political participation practiced in democratic systems were discussed. In the midst of the crisis of representative democracy (in which political participation is limited) and with the emergence of counter-hegemonic models of participatory democracy (which defend a greater involvement of society in political decisions), emerges the digital democracy model, seen as an opportunity for a desirable transformation in the political scenario, still hegemonically representative.

With the accelerated dissemination of ICT and the emergence of a new communication order structured via networks, there was a deep social, political, and economic transformation. In this context, the state began to utilize ICT as a new communication channel with society. However, despite the existence of a consensus that ICT has the potential to a desirable closer relationship between civil society and the political sphere, in practice, there was no change. Since the first proposals of Electronic Government, in Brazil, studies prove that there is little political participation through digital resources (Cetic.br, 2020; Gomes, 2005a), demonstrating that digital democracy ends up reflecting the deficiencies of representative politics.

In fact, the use of ICT does not ensure a more democratic practice, and both participatory processes practiced (presential and remote) have advantages and disadvantages. The utilization of both formats deserves permanent actualization and adjustment to the advances and transformations of society. In this way, it is urgent the creation of a specific space inside the public administration system, in both the city and the state spheres, of tool monitoring, of the existing models, and of new practices experimented in the country and abroad.

Authors such as Gomes (2005a) and Silva (2005) consider that the state, in its planning processes, does not achieve effective political participation. According to the analysis performed in this paper, PMPA is not an exception. Despite being a pioneer in participatory initiatives and having a vast history of ICT use, PMPA advanced little towards digital democracy. With the analysis which looked from 1999 to the present days, it is concluded that the use of ICT by the PMPA is limited to websites, which were created at the end of the 20th century, during mandates of the Workers’ Party [Partido dos Trabalhadores – PT] in the municipal sphere. Also, there are few options of apps for mobile devices, introduced by the PMPA only in the 2010s.

The platforms utilized are mostly developed by the municipal agency (PROCEMPA), demonstrating that PMPA has its own infrastructure, capacity, and facility for the introduction of ICT in its political activities. The repetition of the same functions in different platforms demonstrates that none of these options is seen as an effective channel of dialogue between the PMPA and society. Their predominant functions are to inform and to deliver services to the population, characteristics of Gomes’ first degree of digital democracy (2005a), with the higher degrees either fragilized or entirely absent. These platforms could be better explored for the insertion of political participation.

The discussion presented here about the use of ICT by the state in participatory processes assumes a broader meaning in times of pandemic, pointing to services that could be performed remote and digitally and which could be available permanently, such as online services, the consult of information from different sectors of the state and the remote monitoring of processes. The fragility, in this case, resides in the access and in the interfaces between the platforms and the users, especially those in income brackets and ages with more difficulty in the use of this kind of tool. The virtuality resulting from the technical-scientific-informational medium also raises the question of the sense of what is real and what is not, opening room for the creation of fake news.

Lastly, it can be affirmed that ICT use by the PMPA seems to contribute little, at the moment, to the approximation of society in the political sphere, reflecting the democratic model practiced, in which there are restricted spaces for political participation and social deliberation. There is a need for a deeper investigation of the motives and advantages for the duplication of political practices in the digital space.

The investments of the state in digital mediums are predominantly aimed at the enhancement and the agility of the delivery of services and the promotion of its own propaganda, with the use of the possibilities of ICT in political participation for a society still being underutilized, even with all the advantages it presents. How to make it advantageous for the state the use of the democratic potential of ICT seems to be a question that still deserves deeper research, so that, as it is desired, the political participation of society in political decisions can be amplified.

Referencias

Arnstein, S., 1969. ‘A Ladder Of Citizen Participation’, Journal of the American Planning Association, v. 35, n. 4, pp. 216-224. DOI 10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388>. Access 14 July 2020,

Castells, M., 2018. A Sociedade em Rede. Paz e Terra, São Paulo.

CETIC.BR., 2020. Microdados Pesquisas TIC, Centro Regional de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação. São Paulo. Available at: <https://www.cetic.br/pt/microdados/>. Access 30 July 2020.

Gomes, W., 2005a. ‘A democracia digital e o problema da participação civil na decisão política’, Revista Fronteiras: estudos midiáticos. São Leopoldo, v. 7, n. 3, set./dec., p. 214-222.

Gomes, W., 2005b. ‘Internet e participação política em sociedades democráticas’, Revista FAMECOS, Porto Alegre, v. 2, n. 27, aug., p. 58–78. Available at: <http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/revistafamecos/article/view/3323/2581>. Access 8 July 2020.

Innes, J.; Booher, D., 2004. ‘Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century’, Planning Theory & Practice, v. 5, n. 4, dec. p. 419-436. Available at: <https://escholarship.org/content/qt4gr9b2v5/qt4gr9b2v5.pdf>. Access 13 July 2020.

Maia, R., Gomes, W., Marques, F., 2017. Internet e participação política no Brasil. Sulina, Porto Alegre.

Meirelles, F., 2020. Uso da TI Tecnologia de Informação nas Empresas: pesquisa anual do FGVcia - 31st edition. FGV/EASP, São Paulo.

Pateman, C., 1992. Participação e teoria democrática. Paz e Terra, Rio de Janeiro.

Prado, O., 2009. Governo eletrônico, reforma do Estado e transparência:o programa de governo eletrônico do Brasil. Ph. D. Getúlio Vargas Foundation, São Paulo.

Santos, B., 2002. Democratizar a democracia: os caminhos da democracia participativa. Civilização Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro.

Santos, M., 2013. Técnica, Espaço, Tempo: Globalização e meio técnico-científico-informacional. EDUSP, São Paulo.

Silva, S., 2009. Estado, democracia e Internet:requisitos democráticos e dimensões analíticas para a interface digital do Estado. Ph. D. Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil.

Silva, S., 2005. ‘Graus de participação democrática no uso da Internet pelos governos das capitais brasileiras’, Opinião Pública. Campinas, v. 11, n. 2, oct., p. 450-468.

Soares, P., Augustin, A., Campos, H., Bem, J., Siqueira, L., Lahorgue, M., Waismann, M., Ugalde, P., Marx, V., 2020. ‘A pandemia de Covid-19 no Rio Grande do Sul e na metrópole de Porto Alegre’, As Metrópoles e a Covid-19: Dossiê nacional. Rio de Janeiro, Observatório das Metrópoles. Available at: <https://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Dossi%C3%AA-N%C3%BAcleo-Porto-Alegre_An%C3%A1lise-Local_Julho-2020.pdf>. Access 07 October 2020.

Souza, M., 2018. Mudar a cidade: uma introdução crítica ao planejamento e à gestão urbanos. Bertrand Brasil, Rio de Janeiro.

Wolton, D., 2012. Internet, e depois? Uma teoria crítica das novas mídias. Sulina, Porto Alegre.

1 In 2008, the number of personal computers reached the proportion of one to every four inhabitants and the proportion of cellphones to three to every four inhabitants (Meirelles, 2020).