Museus nunca foram (tão) digitais

Renato Silva de Almeida Prado é arquiteto e mestre em Comunicação e Semiótica, e doutorando no Programa de Pós-graduação em Arquitetura, na Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo. Pesquisa interação e engajamento dos públicos visitantes de espaços expositivos digitais e híbridos — físico e digital. Atualmente, integra o grupo Estéticas e Memórias do Século 21, na FAU-USP. Projetou a interface digital de diversos acervos, como também aplicativos, instalações, websites e sistemas para instituições e espaços expositivos. realmeidaprado@usp.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/2900888162794907

Como citar esse texto: PRADO, R. A. Museus nunca foram (tão) digitais. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 21, Semestre 2, dezembro, 2020. [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus21/?sec=4&item=15&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 23 DE AGOSTO DE 2020

Resumo

O interesse por atividades remotas durante o isolamento social, ocasionado pela disseminação do coronavírus, colocou à prova as experiências digitais proporcionadas por museus e outras instituições culturais para a difusão de seu patrimônio histórico e cultural. Em uma mudança repentina, essas experiências passaram a ser a principal forma que estas instituições dispunham para tal tarefa. Diferentes modelos de exposição de seus conteúdos culturais foram difundidos como catálogos digitais, passeios virtuais, vídeos 360º, galerias de vídeos e imagens, entre outros. Entretanto, a oferta da produção artística no formato digital por parte dos museus não atendeu ao anseio de um público essencialmente digital. O interesse demonstrado no início da pandemia se sustentou por apenas duas semanas e retornou a patamares pré-pandêmicos. Este artigo busca identificar fatores que possam ter contribuído para esse desinteresse por estas experiências digitais ofertadas, tecendo relações entre elas, as práticas análogas adotadas por instituições culturais para seus espaços expositivos físicos e características específicas do espaço digital. Busca-se, assim, estimular reflexões acerca destas experiências, de forma a nortear o seu desenvolvimento perante este novo contexto.

Palavras-chave: Museu, Exposição, Projeto expográfico, Digital, Internet

1 Introdução

O isolamento social implantado às pressas no mundo todo em consequência da rápida expansão da Covid-19, no primeiro semestre de 2020, resultou, em um primeiro momento, no esvaziamento do espaço público e na transformação dos lares em centros de consumo e produção. Diversos ambientes onde se desenvolvem atividades sociais e culturais foram afetados por esta transformação, como cinemas, auditórios, teatros, restaurantes, shoppings centers e museus, entre outros. Como consequência, ampliou-se a demanda por alternativas remotas a estas atividades. Os serviços de streaming cresceram, assim como serviços de videochamadas, compras online e serviços de entrega.

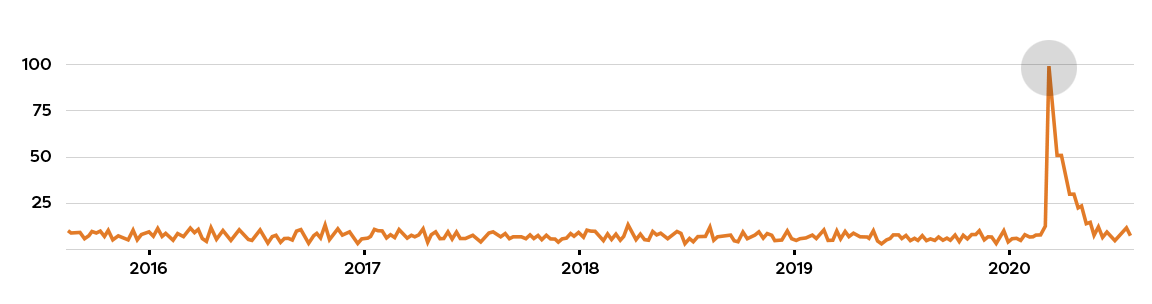

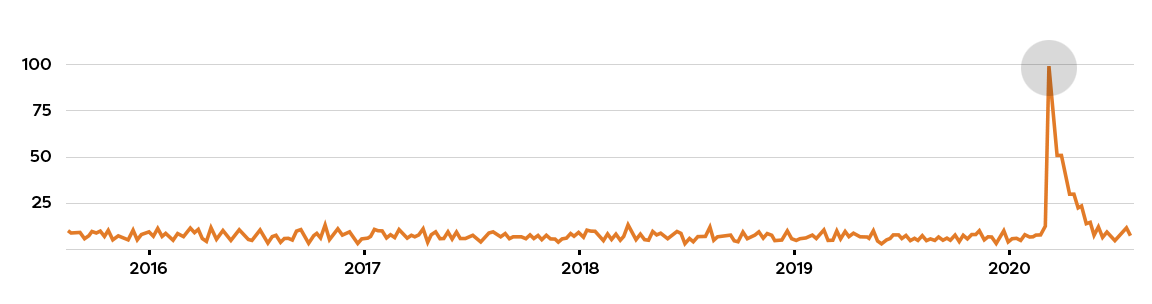

No universo museal, o panorama não foi diferente. Entre os dias 15 e 28 de março de 2020, o número de pesquisas pelo termo online museums, na plataforma do Google, atingiu um pico mais de dez vezes maior que os números registrados em média nos cinco anos anteriores1. Outros termos similares, como online museum, virtual tour , virtual museum e museums online, seguiram curva similar. Repentinamente os termos citados acima tornaram-se populares, assim como passaram a circular nas redes sociais e aplicativos de mensagens inúmeras listas de museus que podiam ser visitados virtualmente.

Entre as experiências oferecidas pelos museus, uma das mais comuns foi o acesso aos catálogos digitais de suas coleções. Mesmo antes da pandemia, museus ao redor do mundo já disponibilizavam seus catálogos em seus sites para a visitação pública – alguns com mais recursos que outros. Entre eles, destacam-se a coleção do Museu do Prado2, na Espanha, o Instituto de Arte de Chicago3, nos EUA e o Rijksmuseum4, na Holanda, entre outros. Outra experiência bastante difundida foi o passeio virtual pelo interior dos espaços físicos dos museus. Instituições como o Dalí Theater-Museum5, nos EUA, o Museu Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza6, na Espanha, e o Louvre7, na França, são algumas das instituições que disponibilizam esses passeios em seus sites. Diversas destas experiências são desenvolvidas em parceria com a Google, através do seu projeto Google Arts and Culture,8 que abriga em sua plataforma boa parte dos passeios virtuais disponíveis, além de outras formas de apresentações digitais desenvolvidas por sua equipe. Em menor número, foram difundidas, também, outras experiências, como o uso de vídeos – Museu Picasso9, na Espanha –, aplicações 360° – Metropolitan10, nos EUA, e Museu do Vaticano11, no Vaticano –, e visualizações 3D de objetos – British Museum12, na Inglaterra –, entre outros.

Em um contexto de pandemia altamente digitalizado, com uma grande oferta de experiências museais para visitar de casa, seria de se esperar uma aderência e engajamento congruentes ao interesse demonstrado globalmente nas pesquisas pelo termo online museums. Mas, ao contrário de outros serviços que tiveram também muita procura, como serviços de streaming, esta efervescência no universo museal durou poucos dias. E, conforme apresentado na figura 1, a queda no interesse pelos termos online museums e similares foi tão rápida quanto o crescimento. Ainda que os dados obtidos junto à Google sejam superficiais, com valores referenciados13, eles servem como um alerta para refletirmos sobre estas formas de exibição que, durante a pandemia, ganharam maior importância do que comumente demonstravam.

Fig. 1: Gráfico de interesse ao longo dos últimos 5 anos pelo termo online museums, na plataforma de busca do Google. O pico destacado representa as semanas de 15 a 28 de março. Fonte: Autor, 2020.

Esse artigo busca levantar pontos que podem ter contribuído para esta queda abrupta de interesse, através de uma análise exploratória destas experiências. Acredita-se que esse apontamento pode potencializar a reflexão sobre as formas com que museus atualmente trabalham a exposição e difusão de seus conteúdos expositivos em um contexto digitalizado. Para tanto, esta análise estrutura-se em quatro grandes tópicos: 1) a natureza do objeto expositivo, que analisa o conteúdo destas exposições, 2) o desenvolvimento da narrativa e 3) o fluxo no espaço expositivo, ambas análises sobre a forma que estes conteúdos são apresentados, e 4) o relacionamento com o público que acessa estas exposições, que aborda a proximidade e a troca que esses museus estabelecem com os visitantes.

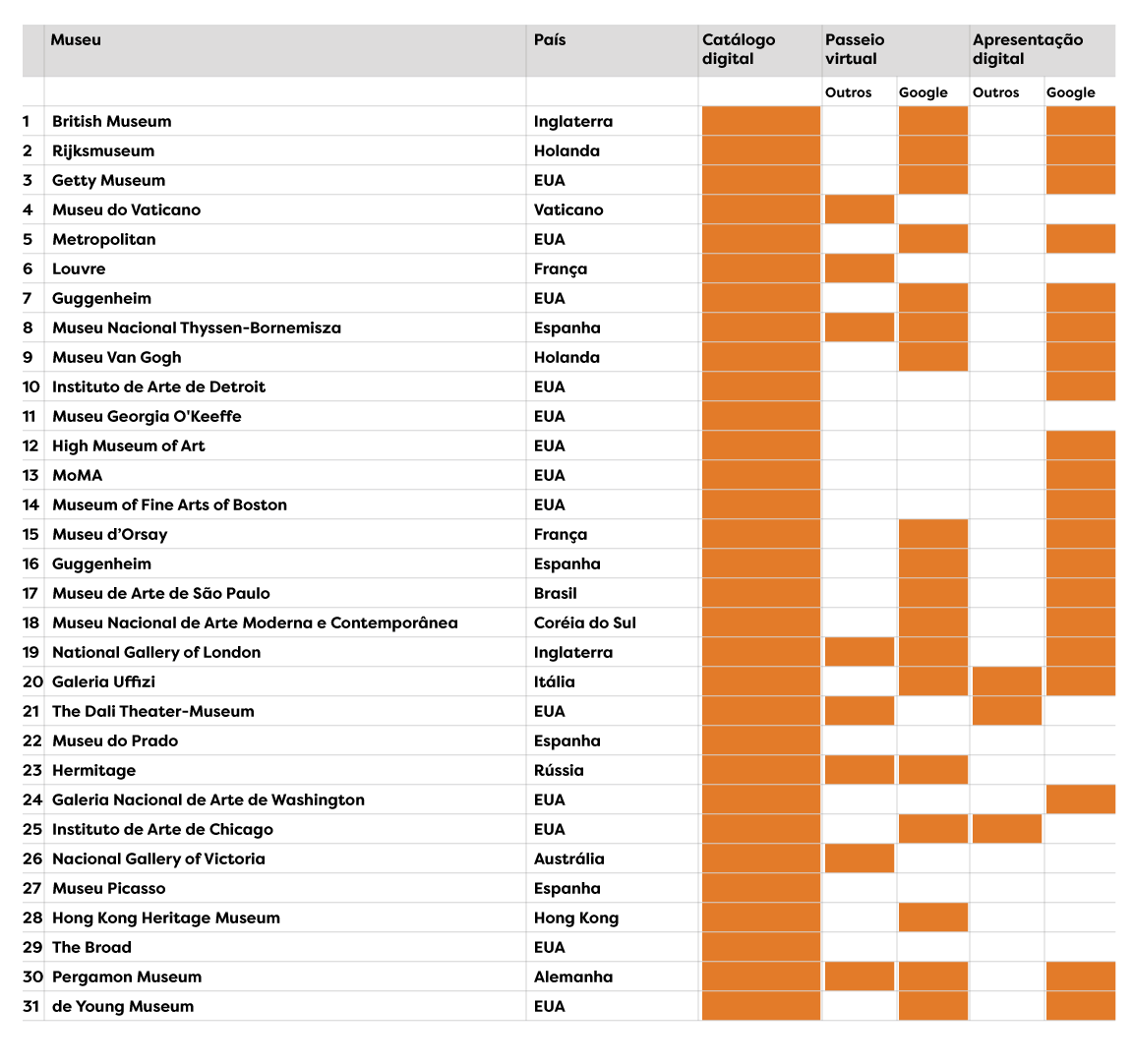

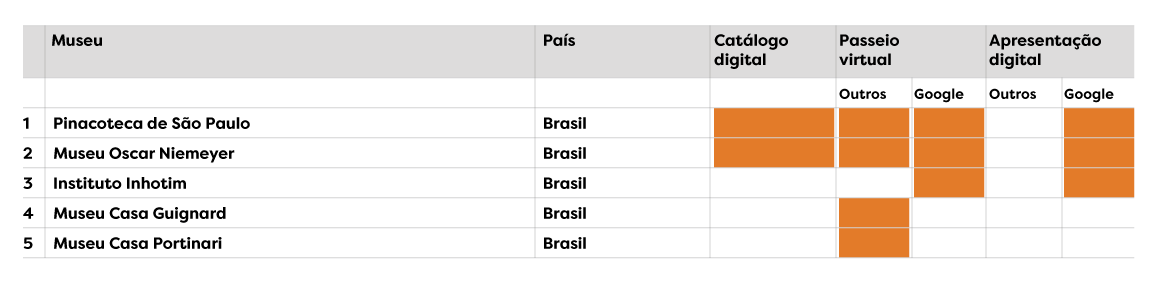

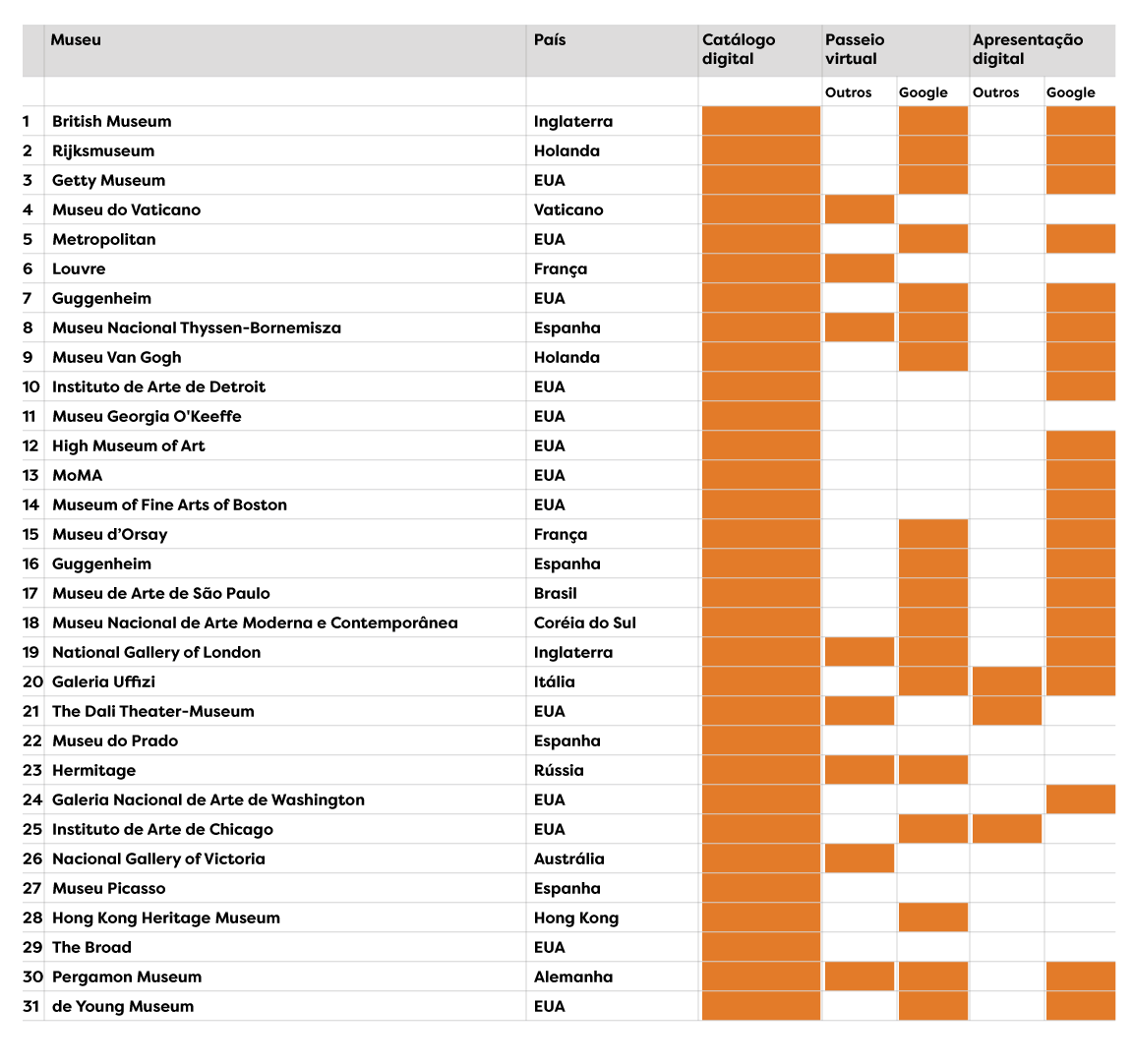

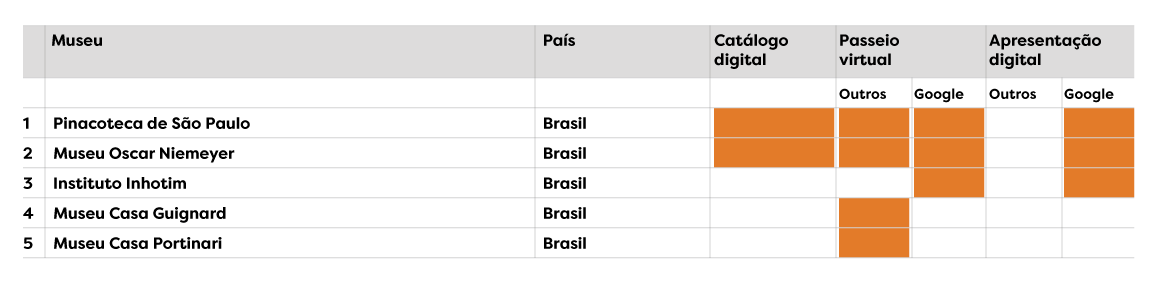

Foram realizadas, na plataforma de busca do Google, duas pesquisas por conteúdos publicados entre março e abril de 2020, de forma a simular as pesquisas realizadas no período de pico dos termos online museums e similares. Na primeira, foi utilizado o termo online museums, realizando a busca em todo o mundo. Conforme ilustrado na tabela 1, foram selecionadas as 31 primeiras recomendações de museus de arte com exposições online, citadas nos sete primeiros resultados apresentados14. Na segunda, foi utilizado o termo museus online, restringindo a busca ao território nacional, e, conforme ilustrado na tabela 2, foram selecionadas as cinco primeiras novas recomendações de museus de arte brasileiros com exposições online, citadas nos três primeiros resultados apresentados15.

Uma vez que o único museu brasileiro que figurou nas listas internacionais foi o MASP, esta segunda pesquisa visou agregar a esta análise as iniciativas nacionais mais difundidas. No total, a pesquisa selecionou trinta instituições estrangeiras e seis nacionais em dez diferentes listas de recomendação.

Tabela 1: Lista dos 31 museus selecionados dos sete primeiros resultados publicados entre março e abril de 2020 e apresentados na plataforma do Google para o termo online museums. A tabela aponta as soluções de exposição digital que cada museu oferece, identificando o uso ou não da plataforma Google Arts and Culture. Fonte: Autor, 2020.

Tabela 2: Lista dos 5 museus do território nacional selecionados dos três primeiros resultados publicados entre março e abril de 2020 e apresentados na plataforma do Google para o termo museus online. A tabela aponta as soluções de exposição digital que cada museu oferece, identificando o uso ou não da plataforma Google Arts and Culture. Fonte: Autor, 2020.

Deste universo pesquisado, as três principais formas de exposição identificadas, que sustentaram o desenvolvimento deste texto, foram os catálogos digitais, os passeios virtuais e as apresentações digitais16. Trinta e três dos trinta e seis museus selecionados apresentam suas coleções em catálogos digitais. Os três únicos museus que não possuem tal recurso são o Instituto Inhotim, o Museu Casa Guignard e o Museu Casa Portinari, todos nacionais. Vinte e sete dos museus selecionados disponibilizam passeios virtuais nos seus espaços físicos – vinte e um utilizam a plataforma do Google Arts and Culture para este propósito, sendo que em quinze esta é a única forma. E vinte e cinco dos museus selecionados procuram expor seus conteúdos em apresentações digitais – destes, apenas três museus possuem recursos próprios, enquanto os outros vinte e dois utilizam a plataforma do Google Arts and Culture.

2 A natureza do objeto expositivo

[U]ma exposição sem uma porção mínima de realidade é inevitavelmente reduzida a um livro a ser lido em pé.[...] Uma exposição é considerada fraca quando substituída, [...] sem precisar sair de casa, por um bom livro, um bom filme, um bom disco ou uma boa conexão de Internet. Um visitante certamente poderia sair e visitar uma exposição deste tipo, mas ele prefere não ir. (WAGENSBERG, 2005, p. 314, tradução nossa)

Em nenhuma das exposições online dos museus pesquisados, os trabalhos expostos são essencialmente digitais: remetem majoritariamente a objetos culturais materiais, representados no espaço digital. Esta característica condiciona toda a análise que se segue, pois a ausência da materialidade em uma exposição online – não apenas relativa às obras apresentadas, mas também ao próprio espaço físico das galerias de um museu – é, provavelmente, o principal fator para o desinteresse por parte do público. É compreensível que, hoje, um serviço de streaming consiga suprir de forma mais adequada a experiência de ir ao cinema do que a visita a um museu online o faz frente a uma visita presencial. Não há, ainda, tecnologia disponível que torne próxima a experiência de apreciar uma obra em um museu virtual da apreciação ao vivo dessa mesma obra. É inevitável aceitar o fato de que, hoje em dia, o encontro ao vivo com um objeto cultural material não será suprido por uma representação digital. Um projeto expográfico digital não precisa assumir tal responsabilidade.

Entretanto, há outras formas de buscar um maior envolvimento do público com estas experiências, seja ao transpor de forma adequada determinados atributos consolidados em uma exposição física, seja na adoção de novos recursos exclusivos deste contexto digitalizado. Quanto a este último ponto, um museu online, por estar acessível de qualquer lugar, pode ser visitado e relacionar-se com um maior número de pessoas de qualquer região do mundo. Apenas cinco dos museus pesquisados não ofereciam suas coleções em inglês. Ademais, alguns catálogos digitais como o do Rijksmuseum, Museu do Prado, Getty Museum e Galeria Nacional de Arte de Washington, por exemplo, disponibilizam imagens em alta resolução cuja ampliação permite a visualização de determinadas características das obras que não seriam possíveis de serem observadas ao vivo em um museu.

3 Desenvolvimento da narrativa

Uma importante característica no estabelecimento de um maior envolvimento entre o visitante e um conteúdo expositivo é a forma com que a expografia estrutura as possíveis narrativas de uma exposição. Ao refletir sobre a linguagem museal enquanto processo de comunicação, Mário Chagas (2011) estabelece que a instituição, a preservação e a seleção de bens culturais – a reserva técnica – seriam análogas ao dicionário. Já a combinação, o arranjo e a arrumação destes bens culturais – o projeto expográfico – seriam análogos a estrutura sintática. Nem o dicionário nem a estrutura sintática por si só constituem linguagem, mas o são quando em conjunto. Desta forma a linguagem museal não existe se não for constituída tanto dos bens culturais quanto de uma configuração específica para eles. Em outras palavras, a linguagem museal depende tanto do acervo, dos objetos expositivos, quanto de uma narrativa, um discurso que dará um novo significado para estes objetos.

David Carrier (2006, p. 94, tradução nossa) sustenta reflexão similar ao dizer que “assim como as palavras formam sentenças cujo sentido e referência dependem de seus componentes, também as obras de arte visuais juntas têm um significado que elas não possuem isoladamente”. E complementa: "Não há dúvidas que uma sequência de obras de arte, sua distribuição, seu posicionamento, mesmo sua iluminação, a cor da parede [...] são pré-condições essenciais para que possam exprimir algo" (BEYER, 2002, p. 29 apud CARRIER, 2006, p. 103, tradução nossa).

Na maior parte dos casos, um projeto expositivo digital vai sempre ser constituído de uma base de dados e uma interface que apresenta esteticamente este conteúdo. A base de dados é o que, em sua reflexão, Chagas relaciona ao dicionário, à reserva técnica. É nela que estão arquivadas as informações catalogadas destes conteúdos. Já a interface materializa a estrutura sintática, a narrativa. Como considera Lev Manovich em seu livro The language of the new media:

Em geral, criar um trabalho baseado em novas mídias pode ser compreendido como uma construção de uma interface para uma base de dados. No caso mais simples, a interface apenas provê acesso a [informações desta] base [...] Mas a interface pode também traduzir [essa] base de dados em experiências muito diferentes para os usuários. (2001, p. 226, tradução nossa)

Os três tipos de exposição online identificados nos museus pesquisados, catálogos digitais, passeios virtuais e apresentações digitais, possuem estrutura correspondente à exposta por Manovich e lidam de formas diferentes na construção de suas narrativas. Apresentam majoritariamente seus conteúdos em dois níveis de visualização. O primeiro nível, uma visão mais geral, que apresenta um conjunto de obras relacionadas; e o segundo nível, uma visão mais específica, que apresenta uma obra isoladamente: sua ficha catalográfica ou parte dela.

Os catálogos digitais, em sua origem, são ferramentas de pesquisa cuja estrutura e interface possuem uma lógica arquivística, presentes nos sistemas de catalogação que são comumente operados por equipes especializadas. São ferramentas originalmente destinadas a um uso educacional – com foco em pesquisadores – que passaram a ser utilizadas também como uma forma de difusão para um público não especializado. Nestes casos, a construção da narrativa é determinada pela pró-atividade do visitante em sua pesquisa. Não há um ou mais caminhos pré-determinados por um projeto expográfico. A narrativa é construída na medida em que o público altera parâmetros desta ferramenta e visualiza novos conjuntos de obras. Essa característica é um ponto sensível, pois há uma parcela do público que tem preferência por ser conduzido por um discurso curatorial a desenvolver sua própria investigação17.

Catálogos são compostos basicamente de listas, muitas vezes no formato de grid, e fichas catalográficas. Nas listas, são apresentados recortes de obras selecionadas por um visitante; nas fichas são apresentadas informações detalhadas de uma única obra selecionada. Nestas listas, as obras aparecem de forma padronizada, com pouca ou nenhuma diferenciação entre elas: a forma com a qual as obras são apresentadas está mais ligadas à estrutura de lista do que a alguma característica da própria obra. Nenhum dos trinta e três catálogos pesquisados apresenta suas coleções em formato diferente de lista ou grid.

Já na apresentação das fichas individuais de uma obra, existe uma maior diversidade de visualidades e recursos disponíveis entre os diferentes museus. Enquanto há interfaces mais simples como as apresentadas pelos museus brasileiros, o Museu do Vaticano e o Louvre, há também interfaces mais complexas, como as do Instituto de Arte de Chicago, Museu do Prado, MET, British Museum e Rijksuseum. Nestas últimas, há uma maior quantidade e melhor organização das informações catalográficas e relacionais de uma obra, o que abre novas rotas e possibilidades de narrativas para os visitantes. Entretanto, ainda que haja variação de museu para museu, as soluções adotadas se repetem, de forma homogênea, para as outras obras da mesma instituição, criando um mesmo padrão visual durante todo o fluxo da exposição. O único caso que apresenta característica divergente é o catálogo do Museu Van Gogh que, em sua ficha catalográfica, posiciona cada obra sobre uma cor específica.

Já os passeios virtuais buscam no projeto expográfico presencial a narrativa para a apresentação online dos trabalhos. São processos de simulação do espaço físico dos museus que colocam o visitante dentro de um ambiente tridimensional, permitindo-o circular por entre as galerias como se estivesse presente nas instalações físicas destas instituições. Ao contrário dos catálogos, os caminhos já estão definidos no projeto expográfico e a pró-atividade do visitante não tem a mesma importância. As obras estão posicionadas da forma como foram no projeto expográfico original, transpondo para a experiência virtual a mesma narrativa do espaço físico. Este ambiente tridimensional possui a mesma função que a lista nos catálogos digitais: apresentar um conjunto de trabalhos com uma temática e um discurso que os une. E assim como nas listas, cada obra neste ambiente pode ser ligada à sua ficha catalográfica. Dos vinte e sete passeios virtuais da pesquisa, apenas o da National Gallery, na Inglaterra, possui fichas catalográficas para todas as obras expostas. Outros mostram informações de obras selecionadas, como o Museu Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, a Pinacoteca de São Paulo e o Louvre. Outros, ainda, não possuem informação alguma sobre as obras, como o Museu do Vaticano e o Museu Casa de Portinari.

Através deste ambiente tridimensional, o visitante pode compreender a disposição e o tamanho das salas, apreciar características do projeto arquitetônico do museu, seu pé direito, as texturas de seus materiais. Pode observar detalhes do projeto expográfico, a circulação, a iluminação, as cores, a composição das obras, entre outras características. Alguns museus, como o National Gallery of Victoria, na Austrália, Thyssen-Bornemisza, na Espanha, Dali Theater-Museum, nos EUA, e Pinacoteca de São Paulo, oferecem a possibilidade da experiência ser realizada em realidade virtual, o que exige que o visitante possua um dispositivo adequado para esta função. Hoje, com a visita ocorrendo nas telas de computadores e dispositivos, o desenvolvimento da narrativa nos passeios virtuais fica comprometida. A experiência online não exerce o mesmo impacto da experiência presencial. Suas narrativas são extensas, apropriadas para visitas físicas de longa duração e incompatíveis com uma visita através de um computador ou dispositivo.

Jay David Bolter e Richard Grusin (2000) refletem sobre o processo de remediação, no qual diferentes mídias em diálogo ressignificam-se e geram novas tipologias visuais. Por ser uma novidade, o desenvolvimento de uma nova mídia será pautado no uso e características de outras tradições culturais já estabelecidas, que facilitarão e orientarão sua introdução no cotidiano das pessoas. Pauta-se em algo já conhecido pela sociedade que, paulatinamente, irá melhor compreender suas características, ressignificando-as. No caso das mídias digitais, os primórdios do desenvolvimento de suas interfaces remetem ao texto. Foi ele o primeiro objeto cultural a ser digitalizado (MANOVICH, 2001, p. 74), e interferiu estruturalmente nestas novas linguagens. Incorporamos ao digital o conceito de página: um elemento de tamanho finito que podia ser sequencializado, como em um livro. Nos anos 1990, mesmo com a adição de outros objetos como imagens, vídeos, gráficos, desenhos e tabelas, as interfaces continuavam a ser essencialmente uma página tradicional, similar a um jornal (MANOVICH, 2001, p. 74-75).

Ao longo deste processo de evolução, alguns recursos foram, aos poucos, sendo incorporados, criando experiências mais interativas e dinâmicas – como o caso do hiperlink, do formato html e de linguagens como o javascript. Um processo fundamental que permitiu que as novas tecnologias pudessem ser utilizadas livres das limitações que os suportes tradicionais lhes conferiam e, ao mesmo tempo, explorassem seus potenciais exclusivos, não presentes nas mídias tradicionais. Essa evolução ganhou ainda mais força no início do século XXI, com o surgimento dos blogs e das redes sociais, quando a Internet se tornou um ambiente social, com maior grau de interatividade e maior capacidade de colaboração na construção de conteúdo. Frente à aparição de novos serviços online, a ideia de página perdeu força, as referências do formato impresso revelaram contornos limitadores e passaram a ser preteridos na concepção das novas interfaces.

As experiências de passeio virtual atuais remetem diretamente a este processo. São tentativas forçadas de se manter uma tradição cultural em um contexto onde ela mais opera como um limitador do que um potencializador da experiência museal. É compreensível, uma vez que não há muitas referências que ressaltem tais amarras, mas inadequado, pois não produz no visitante a sensação projetada para a experiência física.

De forma similar aos passeios virtuais, as apresentações digitais possuem uma narrativa pré-determinada. São histórias que podem abordar diferentes museus, coleções, temas, artistas e obras contadas através de conjunto de textos, imagens, áudios e vídeos. A narrativa se desenvolve de forma linear, requerendo, dos visitantes, ações simples, como o clique em setas ou a rolagem de uma página, o que por vezes pode tornar a visita monótona. Ao longo destas histórias, as obras apresentadas podem ser clicadas e, da mesma forma que nos catálogos digitais e nos passeios virtuais, é possível acessar dados mais detalhados sobre um trabalho. É o formato que melhor aproveita das características do espaço digital e é o que mais se distancia da estética tradicional utilizada pelos museus. Entretanto, a dinâmica de uma exposição neste formato é muito semelhante a qualquer outra de outro museu. Os recursos disponíveis para apresentar uma narrativa ainda são poucos e geram narrativas semelhantes.

4 O fluxo no espaço expositivo

“Imagine museus de arte organizados de formas [...] excêntricas, exibindo pinturas de acordo com o tamanho, do menor ao maior; de acordo com a cor, agrupando imagens vermelhas, chinesas, indianas e italianas (juntas); ou de acordo com a data de nascimento do curador responsável pela aquisição. [...] Obras expostas com base em tais classificações são improváveis de serem aplicadas.” (CARRIER, 2006, p. 93, tradução nossa)

De forma simplificada, o deslocamento espacial nas galerias físicas de um museu pode ocorrer de forma linear, onde o visitante percorre um trajeto pré-definido, ou de forma não linear, onde o visitante precisa tomar decisões e definir seu próprio trajeto. Um exemplo de espaço com percurso linear é do Guggenheim de Nova Iorque, onde o fluxo circular é definido pelo projeto arquitetônico de Frank Lloyd Wright. Ainda que cada visitante possa iniciar em diferentes andares ou caminhar em direções opostas, o número de caminhos possíveis é reduzido e controlado. Outro exemplo é a exposição de longa duração que ocupa o andar superior da Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. O deslocamento do público segue o mesmo conceito, com salas numeradas de 1 a 11, criando um fluxo que circunda os átrios centrais do edifício. Já a exposição de longa duração do MASP, Acervo em transformação, possui lógica diversa. Tanto pelo amplo espaço da galeria sem divisórias, quanto pelo suporte das obras – ambos projetados por Lina Bo Bardi –, a organização permite um fluxo não linear dos visitantes por entre as obras, conforme ilustrado na figura 218.

Fig. 2: No projeto expográfico do MASP, a circulação é livre, permitindo ao público um maior leque de caminhos possíveis. Fonte: Cleber Vallin, 2016. Disponível em: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acervo_Exposi%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Recente-8.jpg . Acesso em: 20 ago. 2020.

Os cavaletes de cristal ficam dispostos em fileiras na sala ampla, livre de divisórias, do segundo andar do museu. Retirar as obras da parede e colocá-las nos cavaletes possibilita um encontro mais próximo do público com os trabalhos, e o visitante pode caminhar entre as obras, como em uma floresta de obras, que parecem flutuar no espaço. O espaço aberto, fluido e permeável oferece múltiplas possibilidades de acesso e de leitura, eliminando hierarquias e roteiros predeterminados. (MUSEU DE ARTE DE SÃO PAULO, 2018)

Nos casos acima, e como regra para qualquer espaço físico, uma pessoa terá sempre a possibilidade de personalizar sua narrativa durante sua visita: a velocidade em que transita entre as galerias e os pontos de parada, descanso e reflexão.

Nada impede [um visitante] de ir direto a suas obras favoritas, pouco reparando em um fluxo determinado. Sequer precisa ler os textos de parede. E mesmo que uma exposição esteja organizada em ordem cronológica, normalmente é possível andar até o fim e depois ver a cronologia reversa. (CARRIER, 2006, p. 108, tradução nossa)

Entretanto, esse nível de personalização estará limitado pelos elementos fixos no espaço. Não é possível reordenar as obras segundo critérios pessoais. A priori, há apenas uma possibilidade de organização das obras em uma exposição física. Elas não mudam de posição, e essa rigidez determina limites de narrativas possíveis nestes espaços. Em um ambiente digital esse limite, essencialmente, não existe. Um dos atributos das mídias digitais destacado por Manovich (2001, p. 30-31) é a modularidade. É o potencial de cada objeto digital ter uma estrutura modular e fazer parte de uma estrutura maior – também modular. Cada elemento dentro de um agrupamento é independente do outro; a combinação entre os objetos não é permanente, mas circunstancial; e um objeto pode fazer parte, simultaneamente, de inúmeras combinações. É possível oferecer a um visitante todas as formas excêntricas de organização dos objetos expositivos, conforme coloca Carrier, e ainda ofertar diferentes narrativas curatoriais, educacionais ou customizadas para públicos específicos, e até propor um relacionamento mais horizontal, dando ao público visitante o poder de criar e expor suas próprias narrativas em uma mesma exibição.

Essa modularidade é muito evidente nos catálogos digitais, por razão dos recursos de pesquisa que oferecem. No catálogo do Instituto de Arte de Chicago e do Rijksmuseum, é possível visualizar um recorte de suas coleções de acordo com uma determinada cor. No catálogo do Metropolitan, o visitante é convidado a acessar apenas obras que retratem pássaros e, no do Guggenheim Bilbao, é possível selecionar apenas as aquisições mais recentes. É possível reconfigurar estes espaços expositivos a qualquer instante. Nos passeios virtuais, a experiência é parcialmente limitada pela falta de modularidade que o espaço físico transposto para o ambiente tridimensional proporciona. Embora exista a possibilidade de um deslocamento direto entre diferentes ambientes, a formatação do espaço não é modular. Um trabalho sempre estará ao lado dos mesmos trabalhos, dentro da mesma sala, no mesmo andar. Já as apresentações digitais, assim como os passeios virtuais, apresentam percursos únicos de leitura linear e não modulares.

Se por um lado o isolamento social nos privou de nos movimentarmos para além de nossas casas no espaço físico, por outro, forçou-nos a experimentar diferentes formas de fluxo no espaço informacional. Desde interfaces que continuam a ser exaustivamente utilizadas, como as de videochamadas, filmes e programas em streaming, e as interfaces de pesquisa nas lojas virtuais, até as experiências aqui analisadas, que apresentaram posterior queda de interesse.

5 Relacionamento com o público

Em um ecossistema diverso e dinâmico como a Internet, a atenção de diferentes públicos é intensamente disputada por inúmeras corporações, organizações e instituições, que almejam um relacionamento mais próximo com eles. Para tanto, é necessário conhecer estes diferentes públicos e compreender seus desejos para constantemente ajustar suas estratégias de relacionamento e ofertas de conteúdo. No universo museal, há uma longa tradição na aplicação de pesquisas de público para conhecer os perfis dos visitantes – e suas preferências –, além de avaliar o seus próprios programas e exposições (SCHMILCHUK, 2012, p. 23). Os registros de pesquisas de público nos seus espaços expositivos remetem ao início do século XX (KOPTCKE, 2005, p. 188).

O conceito de museu está em constante evolução, impulsionado por uma combinação de visão curatorial, inovação artística e demandas do público. O primeiro desafio para o museu do século XXI é [...] desenvolver programas para que esses espaços reflitam o desejo do público por um envolvimento mais ativo com a arte. [...] A era digital obriga-nos a responder às necessidades e expectativas de nossos públicos de novas maneiras.” (SEROTA, 2016, n.p., tradução nossa)

Uma forma para responder às necessidades e expectativas dos diferentes públicos é a análise do seu comportamento no espaço expositivo. Uma das técnicas tradicionais mais eficientes para compreender esse engajamento das pessoas durante seu trajeto pelo espaço expositivo é o método de observação dos visitantes ou timing and tracking. Segundo Yalowitz e Bronnenkant (2009, p. 49-50), dados registrados com a utilização deste método descrevem por onde um visitante andou, quanto tempo ficou em determinada área e em determinado conteúdo e o número de paradas. Descrevem o deslocamento do visitante pela galeria, interação social com outros grupos, visitantes, professores e voluntários, assim como o uso de objetos interativos ou vídeos. Ainda, é possível coletar informações demográficas como a faixa etária, número de adultos e crianças em um grupo, gênero, entre outros.

Em um ambiente digital, tanto o espaço quanto os objetos culturais presentes nele são compostos por códigos. Por trás de qualquer um deles, seja um texto, uma imagem, um som ou um vídeo, há um código que o descreve e o representa. O mesmo vale para qualquer atividade que ocorra nestes espaços: qualquer interação com o ambiente ou com os objetos também possui um código que a descreve. Uma importante implicação desta característica é que tudo o que acontece nestes espaços é registrado, e esse registro é passível de armazenamento e análise. É comum que sites e outras aplicações online contenham ferramentas que registrem o fluxo de visitas e de visitantes, organizando estas informações em bases de dados. É também comum que esses dados sejam utilizados para sugerir conteúdos de interesse do público em função das pesquisas realizadas e conteúdos acessados anteriormente. Dos 33 catálogos digitais analisados, 26 possuem códigos que permitem esses registros. Porém, não há nenhum caso onde essas informações retornam explicitamente ao visitante em forma de recomendação de conteúdo personalizado.

Outra forma de aproximar os diferentes públicos dos espaços e conteúdos dos museus é criar condições para que eles estabeleçam vínculos pessoais, encontrem temas de seus interesses, participem da produção de conteúdo e sintam-se parte integrante daquele ambiente. Atrelado ao seu catálogo digital, o Rijksmuseum oferece aos seus visitantes ferramentas para que eles criem suas próprias narrativas, agrupando obras segundo seus próprios critérios19. subvertendo sistematizações já estabelecida pela instituição. Cada narrativa fica disponibilizada, junto a outras narrativas criadas pelo próprio museu, para qualquer outro visitante acessá-la através do site ou do aplicativo que o museu oferece, esteja ele em casa ou no próprio museu. É o único museu online que dá aos visitantes um papel de co-curador de sua coleção. Outros dois museus, como o Pergamonmuseum, na Alemanha e o Museu do Prado, permitem que os visitantes criem uma seleção pessoal de obras, porém sem compartilhá-las com outros visitantes.

6 Considerações finais: um olhar adiante

De forma geral, nenhum ramo de atividade estava devidamente preparado para lidar com as consequências do isolamento social. Museus não esperavam que seus braços digitais fossem ter tamanho interesse e divulgação – ainda menos que fizessem a vez de suas dependências físicas. O que talvez adquirisse maior evidência em alguns anos, consequência da exponencial digitalização da sociedade, foi antecipado de forma abrupta com o esvaziamento do espaço público. Mas o que se viu foi um público que, privado de seu deslocamento físico e mesmo já imerso em um contexto digitalizado, não encontrou no universo museal online um espaço adequado para suprir seu interesse por conteúdo cultural de qualidade. Ainda assim, todas as experiências remotas que as instituições estão promovendo para se manter conectadas com seus públicos certamente trarão transformações que não serão dissipadas com o retorno da convivência presencial. Serão incorporadas, ressignificadas e farão parte de uma nova realidade. Muito já foi desenvolvido, e é a partir desta produção que surgirão novas reflexões e perspectivas. O processo de evolução das atividades online continuará em um movimento crescente.

Por um lado, esse desenvolvimento não deve ser interpretado como uma forma de substituição da experiência ao vivo. Devemos refletir em como eles podem complementar a experiência proposta nas galerias, sejam elas feitas de forma remota ou acessadas de dentro dos próprios espaços expositivos. É necessário pensar, por exemplo, em como potencializar o relacionamento entre museus e seus públicos, pautando-se em um contexto que pressuponha a personalização da narrativa, dos pontos de contato, da forma de apresentação das informações, entre tantas outras variáveis.

Por outro lado, fortalecer e desenvolver um ambiente digital não deve ser encarado como uma ação extraordinária, mas um instrumento a mais – necessário – no processo de democratização do acesso ao patrimônio cultural. Dispor conteúdo para acesso remoto não é concorrer com seu espaço físico pelo interesse de um possível visitante, mas se comunicar com todas as inúmeras pessoas que, por diferentes razões, não se configuram como público potencial para uma visita física. Para tanto, é preciso refletir sobre a forma com a qual os museus irão se relacionar com estes públicos e como aproveitarão das características do universo digital para atingir este objetivo.

Referências

BEYER, A. Between academic and exhibition practice: the case of renaissance studies. In: HAXTHAUSEN, C. W. (Ed.) The two art histories: the museum and the university. Williamstown, Mass.: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2002. p. 25-31.

BOLTER, J. D.; GRUSIN, R. Remediation: understanding new media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000.

CARRIER, D. Art Museum Narratives. In: Museum skepticism: a history of the display of art in public galleries. Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006. p. 91-109.

CHAGAS, M. Linguagens, tecnologias e processos museológicos. Texto apresentado no Curso de Especialização em Museologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, Universidade de São Paulo, 2001. (mimeo).

KOPTCKE, L. S. Bárbaros, escravos e civilizados: o público dos museus no Brasil. Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional, Brasília, DF, n. 31, p. 185-205, 2005.

MANOVICH, L. The language of new media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001.

MUSEU DE ARTE DE SÃO PAULO. 2018. Acervo em transformação. (online) Disponível em: https://masp.org.br/exposicoes/acervo-em-transformacao-2020 . Acesso em: 25 jul. 2020.

SCHMILCHUK, G. Públicos de museos, agentes de consumo y sujetos de experiencia. Alteridades, v. 22, n. 44, p. 23-40, jul./dic. 2012.

SEROTA, N. The 21st-century Tate is a commonwealth of ideas. The Art Newspaper, n. 5 jan. 2016. Disponível em: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/the-21st-century-tate-is-a-commonwealth-of-ideas . Acesso em: 25 jul. 2020.

WAGENSBERG, J. The “total” museum, a tool for social change . História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, v. 12 , p. 309-321, Rio de Janeiro, 2005. Suplemento.

YALOWITZ, S. S.; BRONNENKANT, K. Timing and tracking: unlocking visitor behavior. Visitor Studies, v. 12, n. 1, p. 47-64, 2009.

1 Dados obtidos na aplicação Google Trends. Disponível em: https://trends.google.com.br/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=online%20museums. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

2 Link para o The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, de Artemisa Gentileschi. Disponível em: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-birth-of-saint-john-the-baptist/65572d18-d9a1-42b8-bddd-f931c4b88da6. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

3 Link para o Green Mountains, Canada, de Georgia O’Keeffe. Disponível em: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/2895/green-mountains-canada. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

4 Link para o The Serenade, de Judith Leyster. Disponível em: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-2326. Acesso em 20 de ago. de 2020.

5 Disponivel em: https://www.salvador-dali.org/en/museums/dali-theatre-museum-in-figueres/visita-virtual/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

6 Link to the exhibition Rembrandt and Amsterdam portraiture, 1590-1670. Disponível em: https://www.museothyssen.org/en/thyssenmultimedia/virtual-tours/immersive/rembrandt-and-amsterdam-portraiture-1590-1670. Acesso em 20 de ago. de 2020.

7 Link to the exhibition The Body in Movement. Disponivel em: https://petitegalerie.louvre.fr/visite-virtuelle/saison2/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

8 Disponivel em: https://artsandculture.google.com/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

9 Link para lista de salas disponibilizadas através de vídeo. Disponível em: http://www.museupicasso.bcn.cat/ca/colleccio/ sales-de-la-colleccio/index_en.html. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

10 Link para o The Met 360° Project. Disponível em: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/met-360-project. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

11 Lista de aplicações 360°. Disponível em: http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/ collezioni / musei / tour-virtuali-cast.html. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

12 Visualizações tridimensionais de objetos exibidos no British Museum no site Sketchfab. Disponível em: https://sketchfab.com/britishmuseum. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

13 Um valor de 100 representa o pico de popularidade de um termo. Um valor de 50 significa que o termo teve metade da popularidade. Uma pontuação de 0 significa que não havia dados suficientes sobre o termo.

14 Todos os resultados da pesquisa na plataforma do Google trouxeram listas de recomendação de museu. As listas apresentadas são:

1) Good House Keeping. Disponível em: https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/life/travel/a31784720/best-virtual-tours/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

2) The Guardian. Disponível em: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2020/mar/23/10-of-the-worlds-best-virtual-museum-and-art-gallery-tours. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

3) Ecobnb. Disponivel em: https://ecobnb.com/blog/2020/03/online-museums-free/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

4) Timeout. Disponivel em: https://www.timeout.com/travel/virtual-museum-tours. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

5) Travel + Leisure. Disponivel em: https://www.travelandleisure.com/attractions/museums-galleries/museums-with-virtual-tours. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

6) MentalFloss. Disponivel em: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/75809/12-world-class-museums-you-can-visit-online. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

7) World of Wanderlust. Disponivel em: https://worldofwanderlust.com/virtual-museums-10-museums-you-can-visit-online/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

15 Todos os resultados da pesquisa na plataforma do Google trouxeram listas de recomendação de museu. As listas apresentadas são:

1) Melhores destino. Disponível em: https://www.melhoresdestinos.com.br/museus-virtuais.html. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

2) Tecnoblog. Disponivel em: https://tecnoblog.net/331627/10-museus-online-para-visitar-durante-a-quarentena-do-covid-19/. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

3) Archdaily. Disponivel em: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/936525/6-museus-brasileiros-com-visitas-online-para-conhecer-sem-sair-de-casa. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

16 These digital presentations are based on editorial language with text, images, videos, and audio files, sometimes in slideshow mode.

17 Alguns museus adotam a prática de receber público em suas reservas técnicas, entretanto sua principal ação é apresentar um conjunto de obras com uma temática em comum definida curatorialmente.

18 Sob a licença CC BY-SA 4.0. Disponível em: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.pt_BR. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

19 Disponivel em: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/create-your-own-route. Acesso em: 20 de ago. de 2020.

Museums have never been (so) digital

Renato Silva de Almeida Prado is an architect, has a master's degree in Communication and Semiotics, and is a doctoral student in the Graduate Program in Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. He researches the interaction and engagement of visitors to digital and hybrid – physical and digital – exhibition spaces. Currently, he is part of the group Aesthetics and Memories of the 21st Century, at the same institution. He designed the digital interface of several collections, as well as applications, installations, websites, and systems for institutions and exhibition spaces. realmeidaprado@usp.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/2900888162794907

How to quote this text: Prado, R. A., 2020. Museums have never been (so) digital. Translated from Portuguese by Paula Prates. V!RUS, 21 [online], December. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus21/?sec=4&item=15&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON MARCH 10, 2020

Resumo

The social distancing required by the coronavirus pandemic has increased the interest in remote activities, and the digital experiences provided by museums and other cultural institutions to promote their historical and cultural heritage have been put to the test. In a sudden change, digital experiences have become the main alternative for these institutions to perform this task. Digital catalogs, 360º videos, virtual tours, video and image collections, among others, have become more popular than ever. However, the amount of artistic production in digital formats available at museums did not meet the demand of an essentially digital audience. The interest shown at the beginning of the pandemic was sustained for only two weeks and then fell back to pre-pandemic levels. Then present essay aims at identifying factors that may have contributed to the lack of interest in digital experiences available to visitors. Additionally, it establishes relationships between these and analogous practices used in the physical spaces of cultural institutions, and specific features of the digital space. With that, we seek to encourage reflections on these experiences and support their improvement in this new context.

Keywords: Museum, Exhibition, Executive design project, Digital, Internet

1 Introduction

Social distancing measures were hurriedly implemented worldwide to respond to the rapid expansion of COVID-19 in the first half of 2020. As a result, public spaces were emptied and homes became the centers of consumption and production. Many places where social and cultural activities are carried out were affected by this change — movie theaters, auditoriums, theaters, restaurants, shopping malls, museums, among others. As a consequence, there was an increase in demand for remote activities. Streaming services boomed, as well as online shopping, video calls, and delivery services.

In the world of museums, the landscape was the same. Between March 15 and 28, 2020, the number of searches for the term online museums on the Google platform achieved ten times more hits than the average of the previous five years1. Other similar expressions, like online museum, virtual tour, virtual museum and museums online, followed a similar pattern. All of a sudden, the terms mentioned above became popular, and lists of museums that could be visited virtually started featuring on social media and messaging apps.

One of the most common experiences offered by museums was access to the digital catalogs of their collections. Even before the pandemic, catalogs of museums around the world were available for public viewing on their websites, although some had more features than others. In that sense, some collections stand out, like the Prado Museum2, in Spain, the Art Institute of Chicago 3, in the USA, and the Rijksmuseum4, in the Netherlands, among others. Another widespread experience was the virtual tour within the physical space of museums. Institutions like the Dalí Theater-Museum5, in the USA, the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum6, in Spain, and the Louvre7, in France, are some of the institutions with these tours available on their websites. Several of these experiences were created in partnership with Google, through the Google Arts and Culture8 project, which is a platform that hosts most of the virtual tours available, as well as other forms of digital exhibitions developed by Google’s team. To a lesser extent, other experiences emerged, like the use of videos in the Picasso Museum9, Spain, 360° applications in the Metropolitan10, USA, and in Vatican Museums11, Vatican, and 3D visualizations of artifacts, in the British Museum12, England, among others.

In the context of a highly digitized pandemic, with a wide range of museum experiences available at home, one could expect a level of engagement equivalent to the interest shown globally by the searches for online museums. But unlike other services that were also in high demand, like streaming services, the enthusiasm with museums only lasted a few days. As shown in Figure 1, the interest in online museums and similar terms faded as quickly as it had increased. Although the data obtained from Google are superficial and show referenced results13, they prompt us to rethink these forms of exhibition that gained momentum during the pandemic.

Fig. 1: Interest chart over the past five years for the term online museums, on the Google search platform. The highlighted peak represents the weeks from March 15 to 28. Source: Author, 2020.

This article intends to address some of the reasons that may have contributed to this sudden drop in interest through an exploratory analysis of these experiences. We believe that this analysis can inform the approaches museums are adopting to exhibit and promote their contents in an increasingly digital world. For this purpose, the analysis was divided into four main topics: 1) nature of the exhibition objects, which analyzes the content of the exhibitions, 2) narrative development and 3) flow in the exhibition space, both on how these contents are presented, and 4) relationship with the audience that accesses these exhibitions online, on the rapport and exchange that these museums establish with their visitors.

Two searches were done on the Google search platform for content published between March and April 2020 to simulate the searches done during the peak of popularity of online museums and similar terms. In the first search, the term online museums was searched worldwide. As shown in Table 1, the first 31 recommendations of art museums with online exhibitions were selected. They were cited in the first seven results14. In the second search, the term museu online was used, restricting the search to Brazil. Table 2 shows the first five new recommendations of Brazilian art museums with online exhibitions, cited in the three first results15. Since the only Brazilian museum that appeared on the international lists was the MASP — the São Paulo Museum of Art — our second search aimed at including other relevant Brazilian initiatives in the analysis. In total, the search retrieved 30 foreign and six Brazilian institutions from ten different recommendation lists.

Tabela 1: List of the 31 museums selected from the first seven results published between March and April 2020 on the Google search platform for the term online museums. The Table shows the digital exhibition solutions that each museum offers, identifying whether or not they used the Google Arts and Culture platform. Source: Author, 2020.

Tabela 2: List of the five Brazilian museums selected from the first seven results published between March and April 2020 on the Google search platform for the term museus online. The chart shows the digital exhibition solutions that each museum offered, identifying whether or not they used the Google Arts and Culture platform. Source: Author, 2020.

Three main types of exhibitions were identified and established the ground for this article: digital catalogs, virtual tours, and digital presentations16. Of the 36 selected museums, 33 display their collections in digital catalogs. The only three museums that do not feature that are the Instituto Inhotim, Museu Casa Guignard, and Museu Casa Portinari, all of which are located in Brazil. Of the selected museums, 27 offer virtual tours within their physical space — and 21 use the Google Arts and Culture platform. In 15 of them, this platform is the only alternative. Twenty-five of the selected museums display their content in digital presentations — and only three use their own tools for that, whereas the other 22 use the Google Arts and Culture platform.

2 Nature of the exhibition objects

An exhibition without its minimum ration of reality is reduced irremediably to a book to be read standing up ... An exhibition is known to be poor when it is replaced ... without leaving the house, by a good book, a good video, a good recording or a good internet connection. A visitor certainly could go out and see an exhibition like this, but would prefer not to (Wagensberg, 2005, p. 314).

In none of the online exhibitions of the researched museums the works on display are essentially digital: they mostly refer to material cultural objects represented in the digital space. This characteristic determines the analysis that follows. The absence of materiality — of the works and of the museum halls themselves — is probably the main reason for the lack of interest in online exhibitions. One can fully understand that today a streaming service replaces the experience of going to the movies much better than a visit to an online museum does when compared to a visit in person. There is still no technology available to make the experience of enjoying a work of art in a virtual museum similar to the live experience. We must accept the fact that today the digital representation of a material cultural object does not replace the face-to-face experience. Therefore, a digital exhibition design project does not have to take on such a responsibility.

However, there are other ways to seek greater engagement with these experiences. This could be done by properly transposing certain consolidated attributes of a physical exhibition or by adopting new features created with this digitized context in mind. An online museum can be accessed from anywhere and visited by a great number of people from all around the world, and only five of the surveyed museums did not have their collections in English. Furthermore, some digital catalogs, like those of the Rijksmuseum, the Prado Museum, the Getty Museum and the Washington National Art Gallery, have high resolution images that enable viewers to see details that would be invisible to the naked eye on the museum premises.

3 Narrative development

An important aspect that could lead to greater engagement between visitors and content is how the narrative of an exhibition is prepared. When studying museum language as a communication process, Mário Chagas (2011) says that the definition, conservation, and selection of cultural assets — i.e. a museum’s collection — are similar to dictionaries. On the other hand, the combination, display, and organization of these assets — the exhibition design project — is analogous to syntactic structures. Neither dictionaries nor syntactic structures per se constitute a language, but they do so when combined. Therefore, museum language does not exist if it fails to include cultural assets combined with a set-up designed specifically for them. In other words, museum language depends both on the collection — the exhibited objects — and on a narrative, a story that will give meaning to the objects.

David Carrier (2006, p. 94) has a similar point of view. He states that “just as words form sentences whose sense and reference depend on their components, so too visual works of art set together have meaning that they do not possess in isolation”. He continues: “There is no doubt that the sequence of works of art, their distribution, their hanging or positioning, even their illumination and wall color ... are the essential preconditions to enable them to express something” (Beyer, 2002, p. 29, cited in Carrier, 2006, p. 103).

In most cases, a digital exhibition project will always consist of a database and an interface that presents content aesthetically. The database is what Chagas associates with dictionaries, the collection itself. It is where the cataloged information of these contents is stored. The interface, on the other hand, materializes the syntactic structure, the narrative. As Lev Manovich says in his book The language of the new media:

In general, creating a work in new media can be understood as the construction of an interface to a database. In the simplest case, the interface simply provides access to [information from this] database ... But the interface can also translate [this] database into a very different user experience (2001, p. 226).

The structure of the three types of online exhibitions found in the researched museums — digital catalogs, virtual tours, and digital presentations — are related to what Manovich explained and deal with different ways of creating a narrative. Most of their contents are displayed in two visual levels. The first level shows a more general view and a set of related works. The second, a more specific view, displays the work of art in isolation and its full or partial catalog record.

In their origin, digital catalogs were research tools. Their structure and interface have an archive-oriented logic that is typical of cataloging systems commonly operated by specialized teams. They are tools originally intended for educational purposes — targeted at researchers — but that also started to be used to share information with a non-specialized public. In these cases, the construction of the narrative is determined by the proactivity of visitors in their research. There is no longer a predetermined route established by an exhibition design project. The narrative is created as the public changes the tool’s parameters and views new sets of works. However, this can be tricky, since some visitors prefer to be guided by a curatorial narrative than to do their own research17.

Catalogs basically consist of lists, often in a grid format, and catalog records. The lists feature clippings of works selected by a visitor, and the records have detailed information about a single selected work. In these lists, the works appear in a standardized fashion, with little or no differentiation between them: the works are presented as a list that is not always based on their characteristics or similarities. The 33 catalogs we researched display their collections in a list or grid format.

The individual records of the works, on the other hand, have a greater variety of viewing modes and features across different museums. Although there are simpler interfaces, like those found in Brazilian museums, the Vatican Museum, and the Louvre, there are also more complex ones, like those of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Prado Museum, the MET, the British Museum, and the Rijksmuseum. These complex interfaces have more and better organized information about the works and enable new routes and narratives for the visitors. However, even though there is variation from one museum to another, the solutions adopted are repeated homogeneously for the other works of that institution, creating the same visual pattern throughout the exhibition flow. The only exception is the catalog of the Van Gogh Museum, whose records present each work against a different-colored background.

Virtual tours, on the other hand, get inspiration from physical exhibitions to create online narratives. They simulate the museum premises, placing visitors in a 3D environment and allowing them to explore the halls as if they were in the actual venues of these institutions. Unlike in catalogs, the routes are predetermined in the exhibition design project, and the proactivity of the visitors is not as important. The works are displayed according to the specifications of the original project, transposing the narrative of the physical space to the virtual experience. This 3D environment plays the same role as that of the list in digital catalogs: showing a set of works under a common theme and narrative. Similarly to the lists, each work can be linked to its catalog record. Of the 27 virtual tours featured in our research, the only institution that has catalog records for all displayed works is the National Gallery, in England. Other institutions, like the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, and the Louvre, only show information about some selected works. Some institutions like the Vatican Museum and the Museu Casa de Portinari, on the other hand, do not display any information about their works.

The 3D environment enables visitors to understand the set-up and size of the rooms, as well as appreciate the architecture of the museum, with characteristics like its high ceiling, textures, and materials. Visitors can pay attention to the details of the exhibition design project, circulation routes, lighting, work display, and more. Some museums, like the National Gallery of Victoria, in Australia, the Thyssen-Bornemisza, in Spain, the Dali Theater-Museum, in the USA, and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, in Brazil, offer an alternative experience with virtual reality, but visitors must have a specific device. Today, since visits take place on the screens of computers and other devices, creating a narrative for virtual tours can be challenging. Online experiences do not have the same impact as face-to-face experiences. Their narratives tend to be too long, as if created for physical visits that last longer, and this is incompatible with visits made through a computer or device.

Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin (2000) reflect upon a possible remediation process, in which different media would interact to acquire new meanings and generate new visual typologies. Despite its intrinsically innovative nature, any new media will initially follow the patterns and uses of other cultural traditions to enable its inclusion in people’s daily lives. Something based on what society is already familiar with would enable individuals to gradually understand new features and create new meanings. For example, early digital media interfaces make reference to written text. The first cultural object to be digitized was the text (Manovich, 2001, p. 74), and this affected the structure of the new emerging languages. The concept of page, an element of finite size that can be sequenced, as in a book, was also incorporated into the digital world. In the 1990s, in spite of the addition of other objects like images, videos, charts, drawings, and tables, the interfaces remained essentially traditional pages, similar to those found in any newspaper (Manovich, 2001, p. 74-75).

Some resources were gradually incorporated throughout this evolution process, creating more interactive and dynamic experiences — such as hyperlinks, the html format and languages like JavaScript. This was a fundamental process to enable new technologies to be used without traditional constraints. At the same time, it unleashed their unique potential, which could not be fully explored in traditional media. This evolution gained momentum at the beginning of the 21st century, with the appearance of blogs and social networks. The Internet became a social environment with a great degree of interactivity and greater capacity for collaboration in the production of content. In view of the emergence of new online services, the idea of a page lost strength. References to printed formats revealed limitations and started to be replaced by new interfaces.

Today’s virtual tour experiences refer directly to this process. They are forced attempts to maintain cultural tradition in a context where it operates more as a restrainer than as an enhancer. It is understandable, since there is a lack of references that show these constraints. However, it is misplaced and fails to reproduce the sensations of a truly physical experience.

Similarly to virtual tours, digital presentations have a predetermined narrative. They are stories told through a set of texts, images, audios, and videos about museums, collections, themes, artists, and works. The narrative unfolds in a linear manner and requires simple actions from visitors, like clicking on arrows or scrolling up and down a page, and this can make visits monotonous. Throughout these stories, visitors can click on the works that are displayed and find more details about them, just like in digital catalogs and virtual tours. This is the format that makes the best use of digital features and the most different alternative from the traditional aesthetics used by museums. However, the dynamics of any exhibition in this format are very similar in all museums. The resources available are scarce and, therefore, these narratives eventually become rather similar.

4 Flow in the exhibition space

Imagine art museums organized in … eccentric ways displaying paintings according to size, from smallest to largest; according to color, grouping Chinese, Indian, and Italian pictures with red together; or according to birthdate of the curator responsible for acquisition … Museum hangings based upon such classification are unlikely to be employed (Carrier, 2006, p. 93).

Overall, visitors can move about an exhibition in linear or non-linear manners. In linear flows, visitors follow a predetermined path. In non-linear flows, visitors have to decide what flow or path they will take. The Guggenheim Museum, in New York, is a clear example of linearity, with a circular flow enabled by Frank Lloyd Wright’s project. Although each and every visitor may start on a random floor or walk toward opposite directions, the number of possible paths is limited and controlled. A typical example of a long-term exhibition can be found on the second floor of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. Visitors have a similar experience because the rooms follow a numerical sequence from 1 to 11, promoting a circular route throughout the building. On the other hand, the permanent collection called Picture Gallery in Transformation at the MASP follows a “multiple logic” visitor’s route. Designed by the architect Lina Bo Bardi, the open floor plan and the way the paintings are displayed allow visitors to take non-linear routes, as illustrated in Figure 218.

Fig. 2: NMASP’s exhibition design project creates a free flow which allows the public to choose from a wide range of paths. Source: Cleber Vallin, 2016. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acervo_Exposi%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Recente-8.jpg. Accessed 20 August 2020.

The easels are arranged in rows in the large gallery space, with no divisions, located on the second floor of the museum. Removing the artworks from the walls and displaying them on these easels allow a closer encounter between the public and the artworks. The visitor is invited to walk through the gallery in the midst of the artworks like a forest of pictures that seems to float in space. The open, fluid, and permeable gallery space offers multiple possibilities of access and readings of the works, eliminating predetermined hierarchies and scripts. (Picture gallery in transformation, 2018)

As mentioned above, when it comes to physical spaces, one will always be able to customize his/her narrative while visiting a museum, including: walking pace, points of interest, resting time, and reflection upon the art.

Nothing prevents [a visitor] from walking directly to some favorite paintings, taking little note of the museum flow plan. Nor need you read the wall labels. And even when an exhibition is arranged chronologically, it is usually possible to walk to the end and then view the art in reverse chronological order (Carrier, 2006, p. 108).

However, the level of customization of a visit is limited by some fixed elements. It is impossible to rearrange the sequence of the works according to individual criteria, for example. A priori, there is only one possible arrangement of works in a physical exhibition. The works do not change positions and this rigidity determines the limits of any narrative. In a digital environment, these limitations do not exist. One of the attributes highlighted by Manovich (2001, p. 30-31) is modularity. It is the potential of each digital object to have a modular structure that is actually part of a larger structure, which is also modular. Each group element is totally independent; the combination of objects is not permanent, but circumstantial. The same object can be part of several combinations simultaneously. According to Carrier, art works can be displayed in eccentric ways to tell different curatorial, educational, and customized stories to specific target audiences, including more horizontal relationships with the exhibitions that enable visitors to create and tell their own stories.

This modularity is clear in digital catalogs due to the variety of search features they have. In the catalogs of the Art Institute of Chicago and of the Rijksmuseum, one can have access to art collections by using color as a search criterion. The Metropolitan Museum catalog allows visitors to search for works that portray birds, for example, and in the Guggenheim Bilbao visitors can choose to see the museum’s latest acquisitions. Exhibition spaces can be reorganized at any given moment. During virtual tours, the experience is partially limited by the lack of modularity imposed by 3D environments. Although it is possible to move toward one direction and into different rooms, the format is not modular. A work of art will always be displayed next to the same works, in the same room, and on the same floor. On the other hand, digital presentations, as well as digital tours, have unique linear reading routes that are not modular.

If on the one hand, social distancing forced us to stay home and kept us from going to other physical spaces, on the other hand it made us look for further possibilities in spaces of information. There are interfaces like video calls, streaming of shows and movies, as well as search interfaces in virtual shops that are being exhaustively used. But some experiences, like those we addressed above, attracted greater interest for a short time and then lost popularity.

5 Relationship with the audience

The Internet is a very diverse and dynamic ecosystem where several corporations and institutions compete for attention and try to build a closer relationship with the users. To achieve that, companies must become familiar with different audiences and understand their preferences, so as to constantly adapt their relationship strategies and content.

Museums are known for having a long-lasting tradition of carrying out surveys to find out their visitors’ profiles and preferences. In addition to that, surveys enable the museums to measure the success of their programs and exhibitions (Schmilchuk, 2012, p. 23, our translation). The first records of museum surveys date back to the beginning of the 20th century (Koptcke, 2005, p. 188, our translation).

The concept of museum is in constant evolution, driven forward by a combination of curatorial vision, artistic innovation, and the demands of audiences. The first challenge for museums of the 21st century is to … design programs that can meet the audience’s demand for active engagement with art. The digital age forces us to respond to the needs and expectations of our audiences in new ways (Serota, 2016, para. 4).

Analyzing and understanding visitors’ behaviors during art exhibitions help improve their experience and fulfill their needs and expectations. One of the most traditional and efficient techniques to understand people’s engagement during visits to museums is called Timing and Tracking. According to Yalowitz and Bronnenkant (2009, p. 49-50), the Time and Tracking technique collects data that shows the visitors’ routes, how much time they spent in each room, and how many stops they made inside the museum. These data describe the visitors’ trajectories in the halls, their interaction with other groups, teachers, and volunteers, as well as their use of interactive objectives or videos. Furthermore, it is possible to collect demographic information like age range, number of adults and children in a given group, gender, among others.

In a digital environment, the space and the cultural objects within it are made of codes. All of them, be it an image, sound or video, stem from a code that describes and represents them. The same happens with all the activities that can take place in these spaces: any interaction with the environment or objects also has codes to describe it. An important aspect worth highlighting is that everything that takes place in these spaces is recorded and these records can be stored and analyzed. Websites and other online applications usually have tools that record the flow of visits and accesses, organizing the information in databases. These data are often used to suggest contents that may appeal to the public based on surveys and previously accessed data. Of the 33 catalogs we analyzed, 26 have codes that enable this recording. However, in none of them the information returns to visitors in the form of customized recommendations.

Other ways of attracting different audiences to museum spaces and contents include establishing personal connections, offering access to topics of their interest, enabling them to contribute to content production, and, ultimately, making them feel as if they belong there. In the Rijksmuseum, visitors have access to tools that are connected with its digital catalog and allow them to create their own narratives, grouping works of art according to criteria they establish19, subverting the predetermined systems developed by the institution. The narratives created by visitors and those created by the museum itself are available to everyone. Any visitor can access them on the museum’s website or app from home or in person, inside the museum. It is the only online museum in which visitors can play the role of co-curators of the collection. The Pergamonmuseum museum, in Germany, and the Prado, in Spain, allow visitors to create a personal selection of works of art, but that cannot be shared with other visitors.

6 Final remarks: looking into the future

Overall, no industry was prepared to deal with the consequences of social distancing. Museums were not expecting all this publicity and interest in their digital branches — let alone that the digital world would take the place of their facilities. As a result of society’s exponential digitization, this phenomenon, which could have taken a few more years to be completed, suddenly came about when public spaces became empty. However, it became clear that even though visitors were already familiar with digital contexts, online museums failed to meet their needs of quality cultural content online. Nevertheless, the remote experiences that have been promoted by institutions to ensure they remained connected with their audiences will most certainly result in changes that will not disappear when face-to-face interactions are resumed. They will be incorporated, re-signified, and become part of a new reality. Much has already been done to this end, and new reflections and perspectives will arise from this process. The evolution of online activities will continue in an upward trend.

On the one hand, this development should not be understood as a way of replacing live experiences. We must think about how digital strategies can complement the experience of art galleries, whether remotely or within exhibition spaces, and how the relationship between museums and their audiences can be improved, considering customization of the narrative, contact points, the best way to present information, among many other variables.

On the other hand, improving and developing a digital environment should not be perceived as an extraordinary effort, but rather as an additional tool — a necessary one — in the democratization of the access to cultural heritage. Content meant for remote access is not supposed to compete with physical spaces for the interest of potential visitors, but it can enable communication with countless people who would not visit the museum otherwise, for whatever reason. Therefore, thinking about how museums can speak to these audiences, as well as how they will benefit from the features of the digital universe, is key to achieving this goal.

References

Beyer, A., 2002. Between academic and exhibition practice: the case of renaissance studies. In: Haxthausen, C. W. (ed.) The two art histories: the museum and the university. Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. p. 25-31.

Bolter, J. D., Grusin, R., 2000. Remediation: understanding new media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Carrier, D., 2006. Art Museum Narratives. In: Museum skepticism: a history of the display of art in public galleries. Durham: Duke University Press Books. p. 91-109.

Chagas, M., 2001. Linguagens, tecnologias e processos museológicos. Text presented in the Specialization Course of Archaeology and Ethnology, at the University of São Paulo (mimeo).

Koptcke, L. S., 2005. Bárbaros, escravos e civilizados: o público dos museus no Brasil. Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Brasília, DF, 31. p. 185-205.

Manovich, L., 2001. The language of new media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Picture Gallery in Transformation. 2018, Museu de Arte de São Paulo [online]. Available at: https://masp.org.br/en/exhibitions/picture-gallery-in-transformation-2020. Accessed 25 Jul. 2020.

Schmilchuk, G., 2012. Públicos de museos, agentes de consumo y sujetos de experiencia. Alteridades, v. 22, n. 44, p. 23-40.

Serota, N., 2016. The 21st-century Tate is a commonwealth of ideas. The Art Newspaper, n. 5 jan. Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/the-21st-century-tate-is-a-commonwealth-of-ideas. Accessed 25 Jul. 2020.

Wagensberg, J., 2005. The “total” museum, a tool for social change. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, v. 12 , p. 309-321, Rio de Janeiro. Suplemento.

Yalowitz, S. S., Bronnenkant, K., 2009. Timing and tracking: unlocking visitor behavior. Visitor Studies, v. 12, n. 1, p. 47-64.

1 Data retrieved from Google Trends application. Available at: https://trends.google.com.br/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=online%20museums. Accessed 20 August 2020.

2 Link to the work The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, de Artemisa Gentileschi. Available at: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-birth-of-saint-john-the-baptist/65572d18-d9a1-42b8-bddd-f931c4b88da6. Accessed 20 August 2020.

3 Link to the work Green Mountains, Canada, de Georgia O’Keeffe. Available at: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/2895/green-mountains-canada. Accessed 20 August 2020.

4 Link to the work The Serenade, de Judith Leyster. Available at: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-2326. Accessed 20 August 2020.

5 Available at: https://www.salvador-dali.org/en/museums/dali-theatre-museum-in-figueres/visita-virtual/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

6 Link to the exhibition Rembrandt and Amsterdam portraiture, 1590-1670. Available at: https://www.museothyssen.org/en/thyssenmultimedia/virtual-tours/immersive/rembrandt-and-amsterdam-portraiture-1590-1670. Accessed 20 August 2020.

7 Link to the exhibition The Body in Movement. Available at: https://petitegalerie.louvre.fr/visite-virtuelle/saison2/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

8 Available at: https://artsandculture.google.com/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

9 Link to list of rooms made available ON video. Available at : http://www.museupicasso.bcn.cat/ca/colleccio/ sales-de-la-colleccio / index_en.html. Accessed 20 August 2020.

10 Link to The Met 360 ° Project. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/met-360-project. Accessed 20 August 2020.

11 List of 360 ° applications. Available at: http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/ collezioni / musei / tour-virtuali-cast.html. Accessed 20 August 2020.

12 Three-dimensional views of objects displayed in the British Museum on the Sketchfab website. Available at: https://sketchfab.com/britishmuseum. Accessed 20 August 2020.

13 A value of 100 represents the most commonly searched query, the peak of popularity of a term. A value of 50 means that the term was half as popular. A score of 0 means that there were not enough data about the term.

14 All search results on the Google platform featured museum recommendation lists. The lists presented are:

1) Good House Keeping. Available at: https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/life/travel/a31784720/best-virtual-tours/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

2) The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2020/mar/23/10-of-the-worlds-best-virtual-museum-and-art-gallery-tours. Accessed 20 August 2020.

3) Ecobnb. Available at: https://ecobnb.com/blog/2020/03/online-museums-free/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

4) Timeout. Available at: https://www.timeout.com/travel/virtual-museum-tours. Accessed 20 August 2020.

5) Travel + Leisure. Available at: https://www.travelandleisure.com/attractions/museums-galleries/museums-with-virtual-tours. Accessed 20 August 2020.