O Skateboardingcomo intervenção:

apropriação temporária e identidade no centro de Barcelona

Adriana Sansão Fontes é arquiteta, Pesquisadora em Urbanismo pela Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, e Professora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro.

Como citar esse texto: FONTES, A. S. O Skateboarding como intervenção: apropriação temporária e identidade no centro de Barcelona. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 4, dez. 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus04/?sec=4&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 18 07 2025.

Resumo

A Plaza de los Ángeles, ou coloquialmente Praça do MACBA, é hoje uma referência internacional do skateboarding de rua. Como espaço público de qualidades cívicas inserido em uma área de grande complexidade, sua apropriação temporal vem motivando reações contrárias por parte da comunidade local. Considerando que a praça já consolidou sua identidade baseada nesta intervenção, nos interessa analisar o papel da configuração do espaço da praça em sua apropriação temporária, e as transformações espaciais geradas pela persistência desta prática ao longo do tempo.

Palavras-chave: skateboarding, espaço público, apropriação temporária, identidade, Barcelona.

Introdução

São quatro da tarde de uma sexta-feira. O carioca Marcelo e o alemão Manfred, juntamente com numerosos skatistas de todo o mundo, deslizam seus skates sobre a extensa pavimentação da Plaza de los Ángeles. Junto a eles, mais de vinte jovens praticam manobras acrobáticas aproveitando os desníveis e todo tipo de obstáculos. Muito mais gente compartilha do mesmo espaço: meninas com patinetes; um senhor e uma criança brincando com uma bola; diversos ciclistas que o atravessam; turistas que tiram fotos diante da extensa fachada branca do museu; pessoas que passam rapidamente, e outras que se detém para descansar observando os movimentos dos skatistas.

Quarenta minutos depois aparece uma dupla de guardas municipais. Muitos dos jovens não percebem, não são “locais” nem conhecem as regras cívicas vigentes. Outros mais antenados dão alerta ao grupo, e ao se dispersarem evitam que lhes confisquem os skates. Alguns residentes acusam a Marcelo e Manfred, enquanto protestam pelo atraso da polícia. Um oportunista aproveita a confusão para roubar a bolsa de uma moça que namora distraída. Tão logo a polícia vai embora, os rapazes voltam às suas atividades, em maior número e muito mais animados. Entretanto diversos vizinhos voltam a queixar-se da invasão constante que sofre a praça.

Situações como esta ocorrem cotidianamente na Plaza de los Ángeles, internacionalmente conhecida como a Praça do MACBA, referência para skatistas de todo o mundo e hoje motivo de polêmica na mídia e de tensões entre usuários e moradores. Trata-se de um espaço público bem singular em uma área urbana complexa, cuja apropriação vem motivando tipos de reações como a descrita.

Trata-se, sobretudo, de uma situação exemplar de apropriação temporária do espaço público, que traz à tona temas como diversidade, multiculturalismo, vitalidade, conflito, disputa, reconquista, exclusão, entre outros tantos temas contemporâneos presentes no espaço da metrópole, locus de expressão da pluralidade, seja ela européia ou latino-americana, rica ou pobre.

Reflexões sobre a apropriação

Os mecanismos de apropriação do espaço público nas cidades contemporâneas, segundo Peran (2008, p. 178), respondem a duas diferentes dinâmicas que, embora não excludentes, não compartilham da mesma problemática. Por um lado, existem as práticas de sobrevivência, e por outro, as de disputa pelo espaço. No primeiro caso poderíamos localizar muitos exemplos brasileiros, nossos conhecidos cotidianos. Entretanto, é o segundo caso que será abordado neste artigo, por ser mais apropriado à realidade da cidade de Barcelona, contexto deste trabalho.

O caso de Barcelona é emblemático por se tratar de uma cidade atualmente submetida a uma progressiva política de controle urbano. Este fenômeno quem aponta é Delgado (2007), um dos críticos mais ferozes deste fenômeno. Ele se refere ao impulso excessivamente projetual, que, ao ‘desenhar’ toda a cidade, mascara a finalidade de filtrar a complexidade, codificar o espaço e reduzir a tensão urbana. Nesse sentido, a presente análise pretende reconhecer que a apologia às apropriações espontâneas tem relação estreita com as sociedades super organizadas e opulentas, e à necessidade de desenvolver práticas antagônicas, quando não literalmente livres (PERAN, 2008, p. 177).

Tratar de apropriações espontâneas do espaço público significa olhar para as expressões subversivas, contrárias à regulação, ao controle urbano e ao planejamento. Ramoneda (2008, p.176) ressalta que estas formas de apropriação são elementos de inconstância gerados pela própria cidade, normalmente à margem das lógicas de poder e de produção, e que expressam novas formas de conflito e resistência. No entanto, também devem ser entendidos como sinais indicativos de possíveis vias de transformação, por tratar-se de formas de expressão da vivacidade da cidade.

Mas o que significa apropriar-se?

Segundo Delgado (2008, p. 192), o espaço público, enquanto espaço de todos, não poderia ser objeto de posse, mas sim de apropriação. Apropriar quer dizer reconhecer como própria, no sentido de apropriada, apta ou adequada para algo. Borden (2001), por sua vez, acredita que a apropriação não é o simples reuso de um espaço, mas o retrabalho criativo deste espaço-tempo. O processo de apropriação cotidiana de um espaço construído implica, portanto, certa desrealização deste espaço, sua transformação criativa, e é aí que reside a essência da vida coletiva no meio urbano. Ela não se define somente pela oposição entre grupos, mas por uma constante tensão entre a espacialidade construída e aberta ao uso, e à desconstrução retórica deste espaço, feita em proveito da expressão de estilos de vida diferenciados (AUGOYARD, 1979, p.101), e por vezes conflitantes. Portanto, tudo indica que estamos diante de um fato transformador, de uma intervenção temporária cujo resultado é a injeção de vitalidade nas ruas, reagindo contra a cidade controlada, disciplinada e excludente.

No universo das apropriações espontâneas imagináveis, interessa-nos aqui trabalhar sobre o skateboarding de rua em Barcelona. Fundamentalmente, a escolha se deve ao traço de contemporaneidade desta intervenção, nômade, surgida recentemente como um extravasamento da prática do skate em espaços “institucionalizados”, e que imprime na cidade uma nova velocidade, produz espaço, tempo e postura social (BORDEN, 2001).

Algumas dimensões da apropriação

Em uma breve abordagem teórica antes da exposição do caso, gostaríamos de recuperar alguns autores que trabalham a problemática da apropriação espontânea, pontuando algumas dimensões desta prática que possam contribuir para uma visão multifacetada do fenômeno e propor avanços na pesquisa sobre o tema.

- o espontâneo, o pequeno e o particular

Crawford (2005) denomina como “everyday urbanism” [urbanismo cotidiano] as diversas atividades ou ‘atitudes’ perante a cidade que celebram a riqueza e vitalidade do cotidiano, aproveitando as potencialidades e encorajando o uso dos espaços de forma alternativa e empírica. O urbanismo cotidiano é o ‘modo de vida’ no domínio físico das atividades públicas corriqueiras, o “everyday space” [espaço cotidiano], espaço passível de apropriação e transformação pelos usuários de forma a melhor acomodar as necessidades da vida cotidiana, conduzindo-o a uma re-familiarização.

Sob sua ótica, a cidade é formada em maior medida pelo urbanismo cotidiano do que pelo desenho formal e pelos planos oficiais, sendo estas atividades não planejadas, espontâneas, um tipo de arquitetura no sentido em que dão forma aos espaços urbanos (KIRSHENBLATT-GIMBLETT apud CHASE, J.; CRAWFORD, M.; KALISKI, J., 1999). Acrescenta que não existe um ‘urbanismo cotidiano’ universal, mas uma multiplicidade de respostas para lugares e tempos específicos, onde as soluções são modestas e pequenas em escala, contidas em calçadas, praças ou pequenos espaços. Estes traços trazem à tona as dimensões do espontâneo, do pequeno e do particular contidas nas apropriações temporárias.

- o subversivo e o ativo

La Varra (2001) foi o primeiro autor a cunhar o termo “Post-it City” [cidade ocasional]. Ela equivale à rede temporária de estruturas funcionais que ocupa interstícios do tecido urbano e promove a escrita temporária dos espaços públicos fora dos canais convencionais. Estes modos temporários de ocupação do espaço revelam habilidades subjetivas na tarefa de reconquistá-lo frente à pressão institucional à qual está submetido, tornando-se a apropriação um sensor da qualidade urbana latente.

Devido à espontaneidade com que se disseminam no espaço, estas ‘cidades ocasionais’ são vistas como formas de resistência à normatização dos padrões de comportamento, ao espetáculo e ao consumismo da cidade opulenta, trazendo à tona a dimensão subversiva da apropriação temporária. Chamamos subversiva na medida em que desafia as regras vigentes, fazendo com que questionemos aonde estas nos pretendem conduzir.

Ademais a dimensão subversiva, enquanto tática de conquista do espaço a apropriação revela sua dimensão ativa, sua capacidade de descobrir potencialidades, de recuperar lugares ou mesmo de ‘poetizar’ no espaço urbano. A apropriação tem essa capacidade de colocar o espaço ‘em ação’, em movimento. Acrescentamos, portanto, a subversão e a ativação como duas dimensões mais da apropriação temporária.

Aqui abrimos um parêntesis. As duas formas de apropriação apresentadas, sejam no sentido de re-familiarização [urbanismo cotidiano] ou enquanto tática de conquista do espaço [cidade ocasional], trabalham com a idéia do informal, da improvisação e da marginalidade. Observa-se, no entanto, uma sutil contradição nas propostas Post-it. De acordo com La Varra (2008), os comportamentos ocasionais não deixam rastros [assim como não deixam os blocos post-it]. Porém, uma vez potenciais ativadores ou táticas de conquista do espaço, seria correto afirmar que não deixam rastros? É neste ponto que se baseia a argumentação central deste trabalho: o temporário deixa marcas, e, nesse ínterim, interessam tanto marcas materiais como imateriais. Kronenburg (2008, p.183) já diria que “a utilização não oficial de determinados espaços chama a atenção sobre o valor dos mesmos e os conduz a investimentos e melhorias mais formalizadas”. Apesar de temporárias, há indícios de que estas apropriações podem motivar transformações mais permanentes.

Olhando mais adiante, além das transformações que possam surgir através das posturas transgressoras, refletimos se haverá nas apropriações espontâneas alguma intenção transformadora. Interessa aqui a apropriação na qual se suspeite existir esta intenção, mesmo inconsciente, que pode surgir de alguma forma original de se ‘usar’ a cidade. Em uma atmosfera de indiferença e rotina, a ação crítica funcionaria como um elemento revitalizador (GAUSA, 2001), caracterizada pela vontade de interagir, ativar, produzir, expressar, mover e relacionar, agitando os espaços e as inércias através de “acontecimentos” ou “eventos”. Nada mais apropriado a este universo que o impulso lúdico do skateboarding.

- o participativo

A respeito da dimensão participativa, Temel (2006) argumenta que usos e ocupações temporárias são vistos atualmente como ferramentas de potencialização, revelando novas possibilidades para os espaços urbanos.1 Por estarem à margem do planejamento, atuam na forma de auto-observadores da sociedade, explorando nichos e apresentando-se muitas vezes como alternativas, potência e forma de movimento para a revitalização de áreas residuais e ociosas, inclusive com potencial elástico permitindo o contínuo fazer e desfazer. Ressalta, neste contexto, o caráter participativo das apropriações espontâneas, a possibilidade de se colocar em prática um planejamento de base, motivado pela atitude do “faça você mesmo”.

Assim, é possível relacionar o skateboarding às dimensões da apropriação da seguinte forma:

|

Espontâneo |

É feito por qualquer skatista sem organização prévia / expressão individual e coletiva |

|

Pequeno |

Ocupa fragmentos de cidade, interstícios, áreas marginais / contrário ao grande evento |

|

Particular |

É específico a determinado contexto atraente ao skatista |

|

Subversivo |

Rompe as regras preestabelecidas / usa a cidade de forma alternativa |

|

Ativo |

Reconquista lugares / movimenta criativamente o espaço público |

|

Participativo |

Descobre lugares potenciais ‘de baixo para cima’ |

- o relacional

Finalmente, para defender a dimensão relacional das apropriações espontâneas, recorremos a Sabaté, Frenchman e Schuster (2004). Os autores utilizam-se do termo “event places” [lugares de eventos] para analisar a relação entre eventos e lugares durante o tempo. Defendem a existência de uma relação simbiótica entre ambos, sustentando que eventos memoráveis deixam marcas nos lugares e dão forma aos espaços, pouco a pouco transformando as cidades. Centrando no caso das apropriações espontâneas e nas particularidades do skateboarding, desejamos comprovar a existência desta dimensão relacional entre “intervenção” e “local”, neste caso entre o skateboarding e a Praça do MACBA. Através do estudo de caso a seguir, propõe-se refletir sobre a importância da configuração da praça em sua apropriação temporal por esta “tribo urbana”, e ao mesmo tempo sobre as transformações derivadas da persistência desta atividade no tempo.

OSkateboardingna Praça do MACBA

Como forma de introduzir o estudo de caso, colocamos abaixo alguns aspectos gerais da apropriação.

[A] Impulso: Apropriação temporária através da prática do skating.

[B] Intenção: Apropriação totalmente espontânea, sem outro objetivo que a própria expressão individual e coletiva. Experimentar a cidade e interagir com seus espaços.

[C] Agentes: Grupo de skatistas sem organização prévia, residentes e transeuntes.

[D] Período: Apropriação sem horário nem duração regular; segundo a presença da polícia.

O bairro do Raval em Barcelona e sua aproximação – Fonte Google Earth.

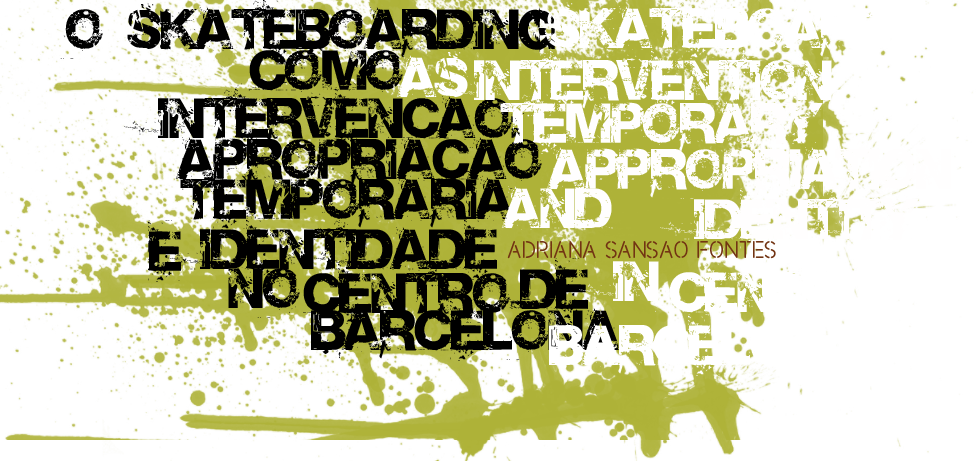

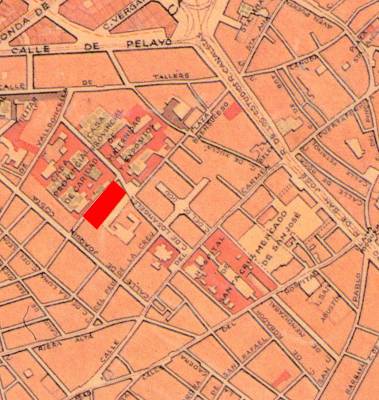

A construção da praça

A origem da Plaza de los Ángeles, localizada no Raval, remonta-se ao século XIX. Garriga e Roca a apresentam em seu levantamento de 1862 como uma simples dilatação do encontro de duas ruas, Ángeles e Elisabets, com tamanho modesto e forma trapezoidal, diante da capela do Convento de los Ángeles. O plano Cerdá afeta a área com a proposta de alargamento de algumas ruas como Ferlandina e Elisabets, e no plano de Pere García Faria (1891) desaparecem alguns edifícios da calle dels Ángels, perto da praça, mudando um pouco sua configuração anterior. Posteriormente, o levantamento de Martorell (1929) mostra seu consecutivo alargamento.

A área em 1862, 1891 e 1929. Fonte: GARCIA ESPUCHE; GUÀRDIA BASSOLS, 1994.

No século XX a praça manteve sua configuração original, até que na década de 80, na ocasião do Plano Especial de Reforma Interior do Raval, é ampliada ao se demolirem diversas edificações que ocultavam o Convento, passando a praça a conformar a frente do edifício da Casa de la Caritat.2 Em 1993 elabora-se finalmente um projeto que lhe conferirá sua forma atual: uma ampla plataforma para realçar o Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Barcelona, inaugurado em 1995. O projeto supõe a demolição parcial da Casa de Caritat, assim como de outros imóveis do entorno.

Edifícios demolidos na área e projeto do Museu

Fonte CABRERA i MASSANÉS, 2007.

Este estudo de caso se aterá a alguns aspectos relevantes deste espaço que nos permitam entender o porquê de seu atrativo para skatistas e visitantes. Referem-se a categorias como inserção na cidade, tamanho, tipologia, arquitetura e plano suporte. Com isso deseja-se dar conta das principais qualidades físicas do local.

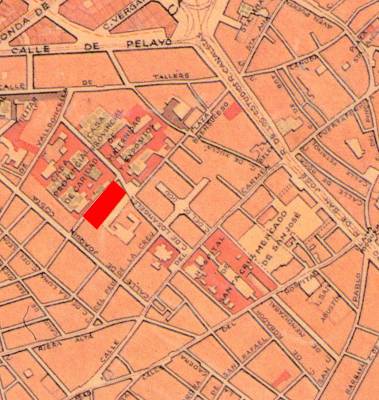

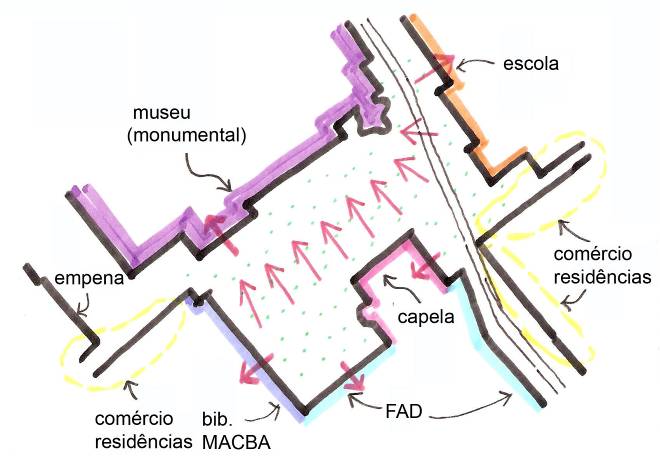

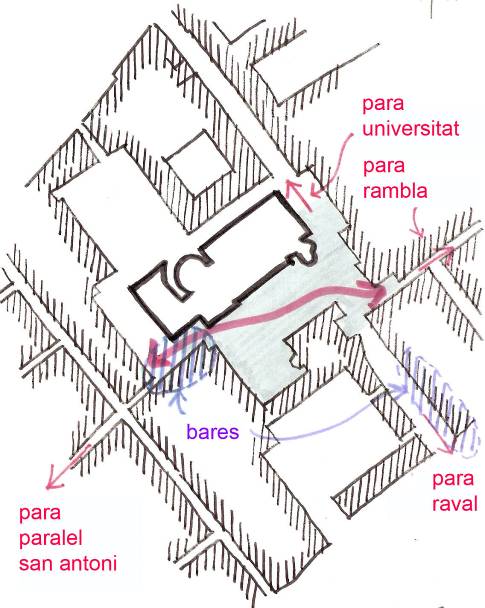

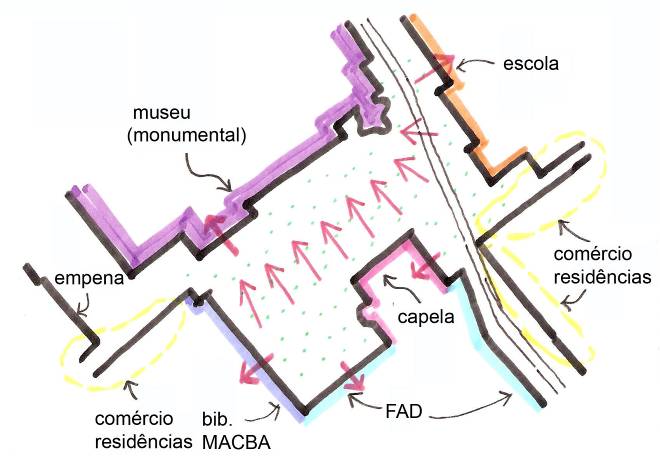

[A] Inserção na cidade 3

A praça localiza-se em um entorno de grande riqueza patrimonial, e acolhe bem diversas atividades. Em paralelo à sua remodelação, o Convento de los Ángeles adequou-se e a Casa de Caritat passou a alojar o Centro de Cultura Contemporânea de Barcelona, ao mesmo tempo em que os usos residenciais e comerciais concentraram-se nas ruas Ferlandina, Joaquin Costa e Elisabets. Com o passar dos anos se consolidam diversos usos culturais em edifícios restaurados, como o já mencionado CCCB e o Fomento de las Artes y del Diseño [FAD], que ocupa o antigo convento, e são construídas novas obras como a Facultad de Ciencias de la Información e os edifícios da Universidad de Barcelona [UB], completando a fachada da rua Montalegre.

Trata-se de uma área complexa, que concentra predominantemente usos culturais e institucionais, embora inserida em uma antiga zona residencial e comercial. Foi nos últimos anos que a área adquiriu um marcado caráter comercial com a chegada de imigrantes e a proliferação de um comércio multicultural, além do incremento da vida noturna devido à abertura de diversos bares e restaurantes.

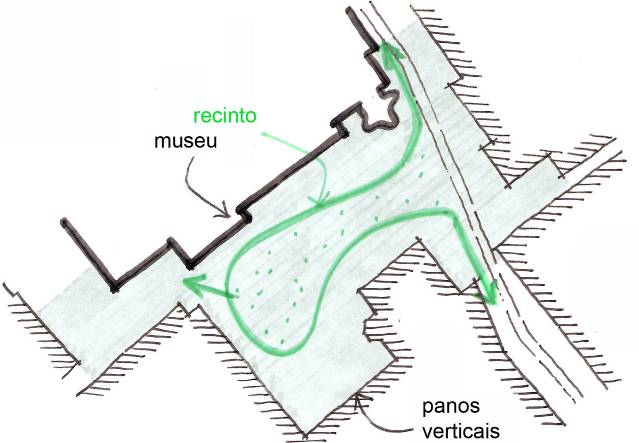

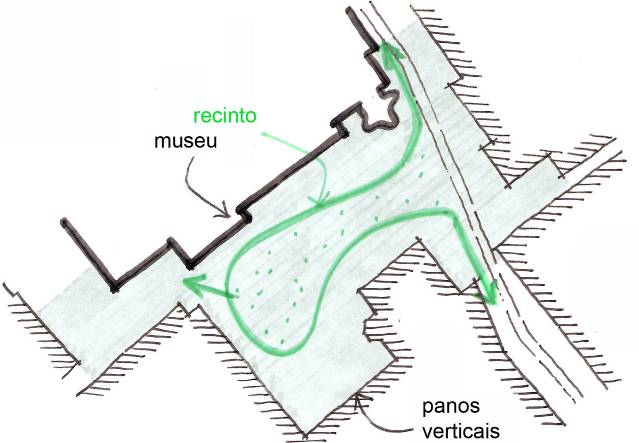

Croqui da inserção urbana da praça. Fonte: Autora.

[B] Tamanho

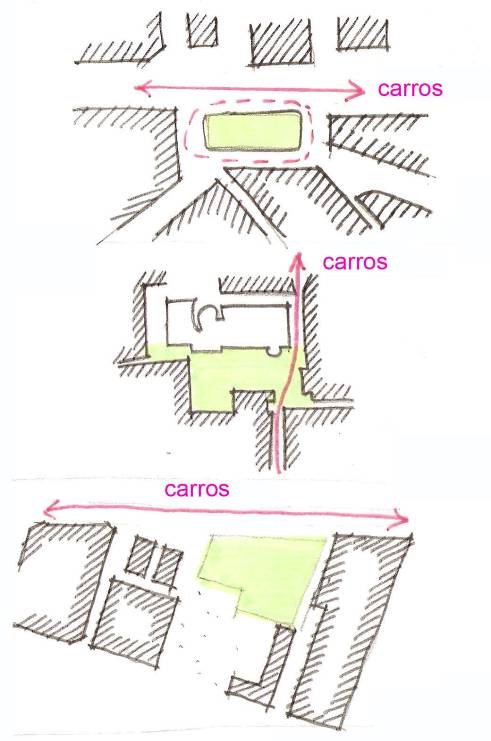

No Raval encontramos outras praças construídas nos últimos quinze anos que formam uma seqüência de espaços públicos com usos diversos. Porém, a do MACBA, um retângulo de aproximadamente 100 x 50 m, é a maior e melhor conectada de todas elas, o que a confere certa hierarquia sobre as demais.

1 Debate ocorrido em simpósio: Temporare Nutzungen im Stadtraum, In: tempor.rar [simpósio], mai 2003. Viena.

2 O estudo “Del Liceo al Seminario” propõe em 1986 a reordenação da área da Casa de Caritat e a Illa Misericordia, vinculando edifícios históricos, novos equipamentos e espaços públicos, entre eles a ampliação da Plaza de los Ángels.

3 Todas as fotos e croquis de análise são da autora.

Comparação da praça com as demais praças do Raval. Montagem: Autora.

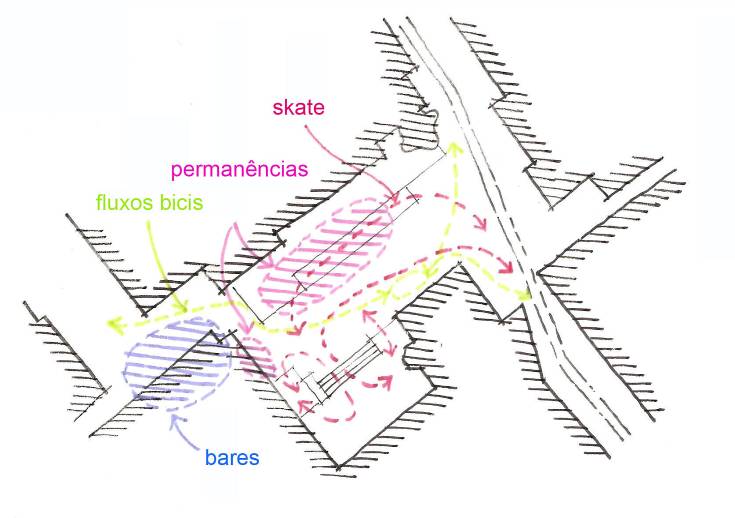

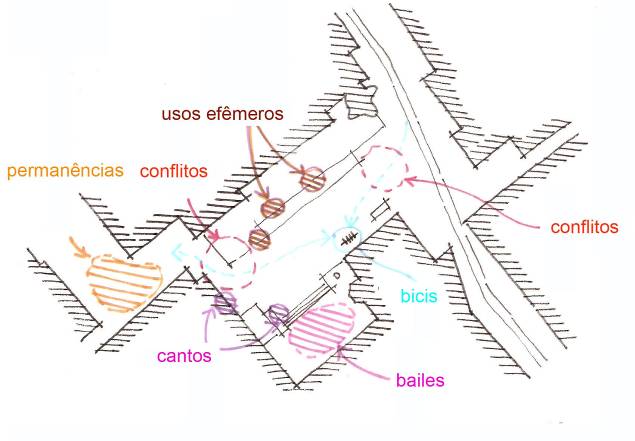

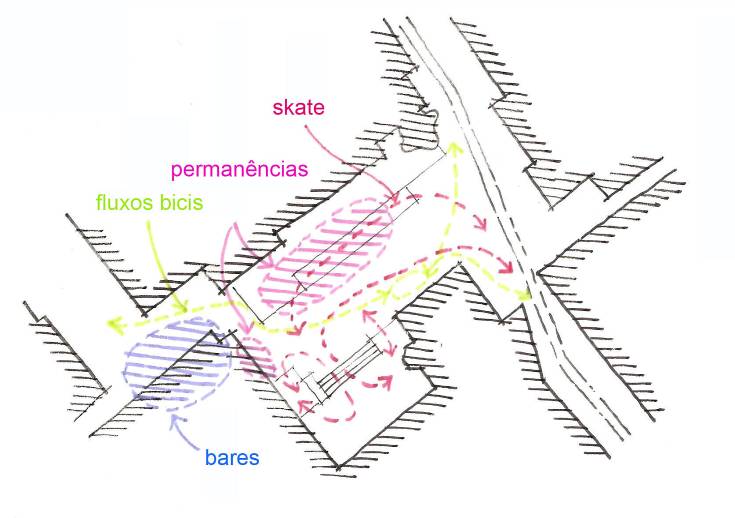

Leitura dos fluxos e permanências da praça. Fonte: Autora

[C] Tipologia

A primeira característica que chama atenção é a magnitude de seu plano praticamente horizontal, delimitado por amplos panos verticais. Este parece ter sido o principal objetivo do projeto: conformar um espaço unitário e uniforme que realce a monumentalidade do museu. A praça se conforma, assim, como um grande espaço público definido por edifícios de feição diversa, integrando permanências tanto de construções como de espaços abertos, com volumes de tamanho considerável e forte contraste em sua aparência, articulação que a confere complexidade, mas também marcada legibilidade espacial (MARTÍ i CASANOVAS, 2003. p. 11).

Contraste horizontalidade do plano com verticalidade da envolvente. Fonte: Autora.

Tipologia de praça ‘fechada’. Fonte: Autora

[D] Arquitetura

O entorno da praça resulta da combinação de poucas edificações de grande tamanho, o que facilita sua percepção. O museu se alça imponente sobre a praça ocupando todo o seu comprimento, o que parece justificar a intenção do projeto de criar a praça como seu complemento, assumindo sua singularidade arquitetônica, e dotando-o de simbolismo monumental. A lógica adotada no projeto da praça, como parte de uma estratégia de intervenções no casco antigo de Barcelona, supõe confiar no trabalho sobre o plano vertical [novas construções ou edifícios restaurados] para a qualificação do espaço central pouco ocupado (MARTÍ i CASANOVAS, 2003, p. 11).

Caráter monumental do museu. Fonte: Autora.

Tipologia de praça ‘fechada’. Fonte: Autora.

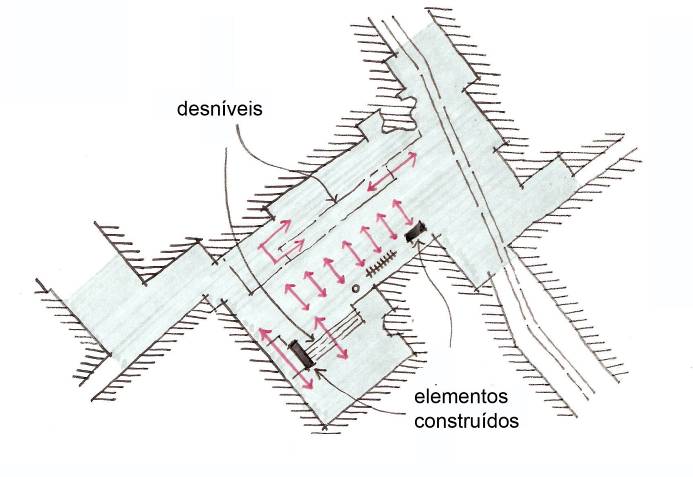

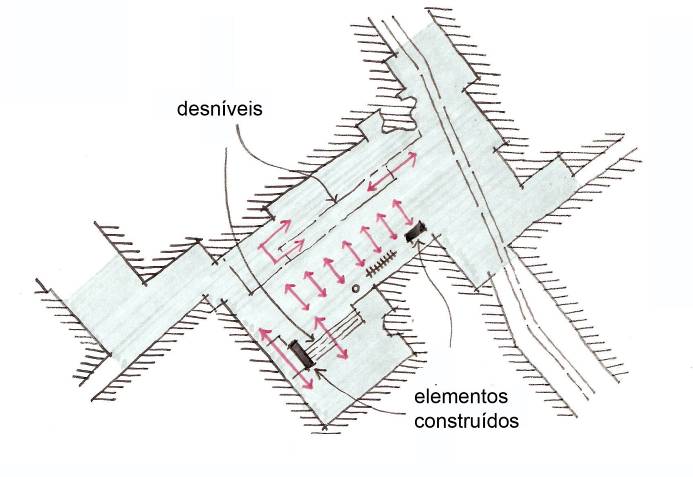

[E] Plano suporte

O plano horizontal que acomoda as atividades é um espaço contínuo, acentuado com poucos elementos construídos, o que o dota de uniformidade e fluidez. A ligeira pendente e os diferentes planos formam um todo conectado e limpo, qualidades que conferem um caráter aberto e facilitam sua capacidade de adaptação.

Plano horizontal contínuo. Fonte: Autora.

Fluidez do espaço. Fonte: Autora.

Skatistas e vizinhos: um conflito anunciado

Como ocorreu em outras cidades, em Barcelona a partir dos anos 80 o skating transbordou os espaços especializados, onde alguém imaginou que deveria confinar-se, e invadiu todo o espaço urbano (BORDEN, 2001, p. 176). Como atividade efêmera, se apropria de âmbitos diversos em cidades de todo o mundo, às vezes somente por curtos períodos. E embora se constitua numa prática bastante globalizada, alguns espaços parecem ser especialmente atraentes. A Praça do MACBA é um destes destinos prioritários, talvez um dos mais importantes e representativos de todo o mundo.4

Porém, enquanto a praça ganha adeptos, os vizinhos protestam pela ‘invasão’ daquele espaço. Já alertaram repetidamente a polícia, fizeram denúncias, e inclusive constituíram uma associação para defender-se da intromissão de uma atividade que consideram prejudicial, conseguindo a proibição da prática de skate no local.

Tudo isso suscita algumas questões relativas à atração do lugar.

O que faz dele tão singular?

Existem em Barcelona diversos espaços melhor equipados, com instalações específicas para skatistas.

Por que não são tão atraentes?

Por que a praça, pensada como plataforma pública destinada a realçar o museu, seguiu este destino?

Outras perguntas têm a ver com as relações sociais que o skating implica.

Por que dita prática incomoda os vizinhos?

Como reagem os outros coletivos?

4 Numerosas páginas web proclamam seus atrativos e incitam a que seja conhecido e utilizado. Umas poucas horas ali nos permitem distinguir a presença de skatistas vindos de todos os cantos do mundo para compartilhar a sua paixão.

Finalmente, outras questões estão relacionadas com o caráter e a vitalidade deste espaço.

De que outras maneiras é utilizado?

Como se organizam as atividades e sub-âmbitos?

Que conseqüências têm dita atividade para o espaço e para o conjunto do bairro?

Arriscaremos uma primeira hipótese interpretativa: as características físicas do espaço incidem em seu destino, porém, muito mais alguns elementos menos tangíveis, como sua atmosfera [mistura de tecidos, construções antigas e contemporâneas, pátina do tempo, complexidade, envolvente espacial], ou o fato de tratar-se de um espaço não apropriado em busca de identidade. Isso parece ter facilitado que o lugar se convertesse em um espaço vivo, diferente de praças de semelhantes plásticas e lógicas projetuais.

Após considerar a origem e conformação da praça, analisaremos as características do skateboarding a fim de avaliar os interesses e transformações que relacionam espaço e evento.

O skateboarding na Praça do MACBA

Barcelona já obteve amplo reconhecimento internacional entre os praticantes do skateboarding. Grande parte da cidade, fundamentalmente as ruas novas, é considerada “patinável” por dispor de superfícies amplas, horizontais e sem obstáculos [ou com pequenos e atrativos obstáculos]. Tudo isso favoreceu a aparição de patinadores em diferentes partes da cidade.

O skateboarding, como atividade espontânea, costuma explorar determinado espaço físico, descobrindo possibilidades diferentes daquelas para as quais o espaço foi criado (BORDEN, 2001, p. 29). Independentemente da idéia original, qual é a primeira coisa que nos vem à mente quando pensamos na Praça do MACBA? Para todos aqueles que a conhecem minimamente, com quase total segurança seria a presença dos skatistas. De fato a praça, que naturalmente não foi pensada para acomodar dita prática, foi descoberta e apropriada por este grupo especifico.

Segundo os principais estudiosos, a chegada dos skatistas a um novo espaço costuma vir acompanhada de sua apropriação e contribuição para conformar uma particular identidade (BORDEN, 2001, p. 53). Na ausência de identidade prévia, estes espaços costumam ser re-formalizados temporariamente através dos usos que acomodam, passando a expressar novos significados a partir dos indivíduos ou grupos que dele se apropriam (CRAWFORD, 1999, p. 28).

Entendemos por identidade um conjunto de características pelas quais um lugar é reconhecível, ou seja, sua especificidade ou diferenças com relação a outros lugares. No caso da Praça do MACBA, podemos admitir que sua identidade seja dada pela presença dos skatistas. Esta constatação vem da identificação generalizada que a atividade tem com este espaço, culminando nas reações públicas da vizinhança em favor de um território que lhes parece “seu”.5

A apropriação da área data do ano 1995. Nesta época a praça [recém construída] não tinha uso e era um espaço vazio e perigoso. No entanto, passou a ser intensamente utilizada por skatistas locais, quando o skateboarding em Barcelona ainda não era “moda”. Paralelamente, havia ao lado uma grande área vazia, depois ocupada pela Universidade de Barcelona, onde alguns skatistas locais costumavam praticar. A partir do ano 2000, com a chegada de gente de outras procedências, a praça se converteu no que é hoje.

Diversos skatistas entrevistados confessaram terem tomado conhecimento da Praça através de filmes que circulam pela web, e que sua relevância mundial os levou a viajar para conhecê-la. Um dos maiores atrativos parecia a possibilidade de conhecer skatistas de procedências diversas, e de trocar experiências e impressões com eles.

A praça constitui hoje um espaço “apropriado” por praticantesde todo o mundo. Caímos na tentação de atribuir em caráter exclusivo esta poderosa atração - suas qualidades “patináveis”- ao fato de dispor de extensas superfícies horizontais, além de obstáculos bem sugestivos. Porém, em Barcelona ditas qualidades não são exclusivas deste espaço. Tantos outros, recentes, também possuem tais atributos, próprios de uma etapa de desenho “minimalista”. Por outro lado, na Praça parecem existir outras características que podem ter tido um papel mais decisivo na apropriação.

As entrevistas com skatistas nos revelaram outros atributos que contribuíram para conformar uma clara identidade: sua tipologia de praça “fechada”, sem muito contato com as ruas, seu aspecto contemporâneo e limpo, sua superfície “dura” e vazia [aberta a usos imprevisíveis], ou inclusive sua origem percebida como marginal. De alguma maneira se crê ter “descoberto” este espaço e tê-lo convertido hoje em uma marca internacional. Vamos centrar nesta capacidade de atração.

Sobre a atração do lugar para os skatistas

Um primeiro aspecto que poderia incidir em sua atração seria a ampla superfície de granito liso e sem obstáculos. No entanto, em tantas outras praças de características parecidas, como, por exemplo, as praças de Gracia, não há skatistas. Pensemos que a atividade urbana do skating constitui uma forma de experimentar a cidade e sua arquitetura, e utiliza diferentes elementos como objetos “saltáveis” (BORDEN, 2001, p. 265). A Praça do MACBA conta com alguns dos elementos preferidos pelos praticantes, como rampas e escadas, assim como outros acidentes sedutores na pavimentação. Mas também estes elementos encontram-se nos outros espaços públicos da cidade.

Seguramente devem existir outras qualidades não tão evidentes que façam deste espaço singular entre skatistas. Para descobri-las, entrevistamos usuários da praça e reconhecemos um leque de razões para tal sucesso. Vamos tentar descobrir onde reside seu atrativo seguindo os mesmos padrões que utilizamos antes para analisá-la.

[A] Inserção na cidade

Das áreas apropriadas por skatistas, as mais populares são as praças centrais: MACBA, Universidad e Tres Chimeneas. Como os skatistas não gostam de isolamento, uma localização próxima a fluxos constitui um fator de atração. A disposição central e conectada da Praça do MACBA possibilita intenso contato com os transeuntes, especificidade ressaltada pelos skatistas como base de sua enorme popularidade.

[B] Tamanho

A dimensão do espaço constitui-se numa característica chave. Um espaço de grandes dimensões[aproximadamente cinco mil m2]possibilita uma maior variedade e convivência de atividades sem grandes interferências. Isto permite a realização de acrobacias que não afetem outras atividades desenvolvidas na praça.

[C] Tipologia

Outra característica atrativa da praça é a permeabilidade. Embora pareça fechada, está diretamente conectada a importantes percursos de pedestres, logo, os skatistas podem escapar com o skate em várias direções. Outra característica relevante é a ausência de automóveis, ou seja, a configuração da praça como um recinto de pedestres. Nas praças de Gracia este parece ser um dos motivos de sua não apropriação, já que são cercadas por ruas onde circulam automóveis.

[D] Arquitetura

5 A identificação uso-local neste caso é tão profunda que não é necessário, por exemplo, recorrer a entrevistas ou outros métodos de pesquisa, já que tanto a ‘fama’ do espaço quanto os conflitos com a vizinhança estão amplamente documentados na internet ou na mídia barcelonesa.

Uma observação menos comentada nos remete à presença do museu. Como a prática do skating pode também ter uma conotação artística [e subversiva], em algumas ocasiões se produz uma interação inconsciente com o museu de arte contemporânea. A não existência de habitação diretamente conectada com a praça, de perfil cultural e institucional, também contribui para a atividade, diferenciando-a novamente das mencionadas praças de Gracia.

[E] Plano suporte

Finalmente, o aspecto que nos parece de maior relevância é a repetida menção à simplicidade espacial. Uma superfície “limpa, com poucos elementos”, convida ao skating. No que concerne aos elementos “saltáveis”, a especificidade da praça é que bancos, degraus e peitoris desenham “figuras” no “espaço” dos skatistas e possibilitam percursos diversos. Rampas e escadas conectam diferentes níveis, e têm altura apropriada para as manobras básicas. Também foi mencionada sua polivalência, onde é possível fazer movimentos variados. A área oferece muitas possibilidades, inclusive, cansado de praticar, de sentar-se para descansar.

Alguns outros atributos, como ser uma área iluminada à noite, contribuem para a persistência da atividade. Uma última singularidade da apropriação, segundo muitos dos entrevistados, é a de possibilitar a mistura de patinadores principiantes e experientes. A praça possibilita uma partilha entre diferentes níveis de skatistas, mas também a convivência com tantas outras práticas urbanas, enfatizando a dimensão democrática do espaço e sua não colonização por uma única atividade, permitindo ademais o desenvolvimento de relações sociais entre usuários diferentes.

A perspectiva dos outros usuários

Como toda área suscetível à aparição de conflitos, a Praça possibilita o desenvolvimento de relações diversas entre diferentes grupos de pessoas. Normalmente quando as atividades conflitantes respeitam uma divisão espacial, tácita ou não, a convivência se equilibra e o intenso uso do espaço o enriquece. Ao contrário, quando a capacidade de grupos diversos de acomodar suas atividades e dividir um espaço não é suficiente para administrar os conflitos, o equilíbrio espacial se rompe.

A análise da relação entre evento e espaço na Praça se realiza aparentemente em um momento delicado, de instabilidade nos acordos sociais para compartilhá-la. Os vizinhos se queixam ostensivamente do uso atual da praça tendo como base dois argumentos: primeiro, consideram que o skating impede o bom uso do espaço pela comunidade local, principalmente crianças e idosos. Ademais, o considerável ruído que causam rompe o silêncio e tranqüilidade de um lugar tão singular.

Os skatistas aceitam que sua atividade desgasta e em alguns casos suja o espaço. Como toda atividade ampla, atrai todo tipo de usuários, desde os mais respeitosos até os mais “selvagens”. Ademais, admitem que o skateboarding, na medida em que se apropria de quase todos os elementos urbanos disponíveis, contribui para seu desgaste.

Os moradores mais velhos não gostam que a praça tenha se convertido no que é hoje. Por outro lado, para os mais jovens, mais inclinados à socialização, o ambiente do skating lhes parece atraente. Por outro lado, a convivência entre skatistas, turistas e usuários regulares parece bastante pacífica, sem grandes conflitos aparentes, ou inclusive com uma apreciável inter-relação, se observamos a grande quantidade de gente que se acomoda nos desníveis para observar diariamente a atividade. Para eles o skateboarding constitui um verdadeiro espetáculo, como é, em sentido parecido, o de ver passar todo tipo de personagens pela Rambla. Uma similar sedução ocorre sobre as crianças. O que se percebe, longe do rechaço, são os gestos amigáveis. Finalmente, os pedestres regulares que só utilizam a praça como um percurso não costumam deter-se a observar as atividades, ao contrário, parecem tentar fugir do percurso habitual dos skatistas como forma de evitar possíveis choques.

Outros conflitos observados afetam as bicicletas, talvez estes os que mais incomodem, neste caso, aos próprios skatistas. O conflito costuma aparecer quando os mesmos saltam os desníveis simultaneamente à passagem das bicicletas. Sobre este conflito ninguém entra em acordo, já que ambos crêem ter a preferência.

Os comerciantes entrevistados reconhecem o aumento da freqüência na área, e como conseqüência, a maior segurança. Para eles, a atividade não traz nenhum incômodo. Aos representantes do museu, o que lhes importa na realidade é manter livre a plataforma superior de acesso, não representando a atividade na parte inferior um grave problema. No entanto, outras vozes não diriam o mesmo. Para muitos, a atividade pode incomodar mais ao museu que aos próprios vizinhos.

Resumindo: a área não está livre de conflitos. De acordo com os próprios skatistas, estes ocorrem com freqüência, mas nunca com gravidade, e os acreditam perfeitamente administráveis. Por outro lado, os residentes se queixam à Prefeitura já que não desejam viver com conflitos. A polícia patrulha freqüentemente, mas como não permanece todo o dia, não é efetiva para fazer cumprir a normativa. Os vigilantes do museu, que pretendem a aplicação da lei, tentam reprimir a prática, mas sem muito êxito. Alheios, os turistas e usuários continuam desfrutando da vitalidade e da intensa experiência urbana que proporciona a praça.

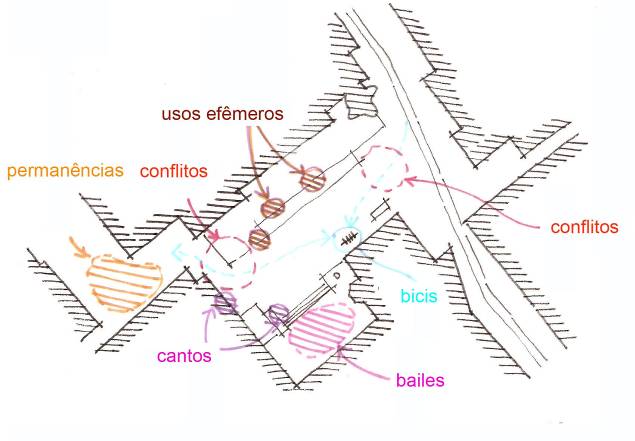

Boa parte da vitalidade do lugar vem da prática do skating. Outras pessoas o utilizam, o que implica não se tratar de um espaço colonizado, mas uma área apta para acolher atividades diversas. No entanto, a maior parte das pessoas que a utilizam se relacionam de uma ou outra maneira com dita prática.6 Os usos da praça e entorno têm a ver com os equipamentos culturais e com o caráter residencial original do Raval. Portanto, além do skating, que não obedece a datas nem horários predeterminados, pode-se observar o desenvolvimento de outras muitas atividades, tanto permanentes como efêmeras.

As primeiras estão relacionadas às varandas dos bares, sempre ocupadas, e desde onde é possível observar as atividades da praça. As efêmeras se distribuem de maneira diversa nos diferentes extremos da praça. O âmbito elevado diante do museu constitui uma espécie de anfiteatro, onde normalmente pequenos grupos observam os skatistas, conversando ou esperando algum encontro. Outras, normalmente relacionadas ao skating, se aglomeram perto da biblioteca, observando ou esperando para entrar em cena. Ocasionalmente também se celebram bailes na praça: grupos de pessoas costumam colocar música na sua parte inferior e mais reservada.

O fluxo de transeuntes é bastante intenso, já que a praça é muito permeável e canaliza muitos percursos. Ademais, é ponto de retirada e devolução do sistema público de bicicletas, que nesta área tem bastante rotatividade, sem falar dos muitos turistas atraídos pelos singulares equipamentos culturais.

Usos e conflitos da praça. Fonte: Autora.

Sobre outros espaços “skatáveis” de Barcelona

Alguém poderia pensar que Barcelona é inadequada para a prática do skateboarding devido à escassez de espaços públicos e à incompatibilidade das calçadas de ladrilho do Ensanche. Mas se observamos com atenção, veremos que muitas intervenções recentes criaram áreas utilizáveis para a prática em diversos pontos da cidade.

Além dos espaços onde se produz apropriação espontânea, a cidade oferece alguns lugares equipados para esta prática. No entanto, devemos saber distinguir duas modalidades de públicos e práticas diferenciadas. Os praticantes do skateboarding “de rua” gostam da sensação de liberdade, da dinâmica e imprevisibilidade das ruas, e se recusam a ficar dentro de um espaço delimitado e projetado para acolhê-los. Por outro lado, os lugares equipados costumam atrair crianças e skatistas mais velhos, que não se formaram na modalidade do skating “de rua” e preferem praticar sem conflitos. Por esta razão, não nos deteremos na análise dos parques com rampas incorporadas ou em espaços “fabricados” como skateparks.7

Depois da praça do MACBA, o skateboarding costuma explorar as praças dasTres Chimeneas e da Universidad, ou a área do Fórum. As três são também bastante populares. Mas, por que não tanto?

Utilizando os mesmos critérios de análise, podemos verificar que nenhuma das três praças tem características tipológicas semelhantes. A Praça da Universidad é um lugar rodeado de ruas com muito tráfego, e muito menos acolhedor. A Praça das Tres Chimeneas é muito mais isolada dos fluxos, enquanto que a área do Fórum é bastante heterogênea e vazia. A escala de uns e outros espaços é mais equiparável e, portanto, não é relevante para responder a nossa questão. A presença da arquitetura na Praça da Universidad não facilita em estabelecer uma relação tão direta, por estar o espaço público circundado por automóveis, distanciando os edifícios e impedindo o contato. Nas Tres Chimeneas parece que a arquitetura não tem tanta relação com o desenho da praça, ficando esta bastante desconectada dos edifícios. No Fórum, a arquitetura monumental e os espaços de desenho contemporâneo podem ser elementos de atração. Finalmente, com respeito ao plano suporte, tanto a Praça da Universidad como a das Tres Chimeneas têm características semelhantes à do MACBA, sendo plataformas limpas que permitem ampla facilidade de movimentos, mas no caso do Fórum, acreditamos que a dura inclinação da plataforma não parece tão atraente.

Chegamos à conclusão de que talvez o único espaço que reúna todas aquelas características de atração para o skateboarding seja a Praça do MACBA, tendo sido o espaço mais procurado e reconhecido pelos praticantes deste esporte, em Barcelona, e talvez em todo o mundo.

Comparações entre as áreas skatáveis. Fonte: Autora.

Considerações finais

O skating, enquanto obra criativa e ativa de seus praticantes, atitude emergente, imprevisível e espontânea, nos mostra diferentes tipos de relação entre usuários e espaço. Assim, a Praça do MACBA é hoje bem diferente de como foi concebida inicialmente. Logo após sua inauguração, muitos duvidavam que pudesse chegar a ser um lugar vivo e dinâmico. Elaboraram-se críticas ao projeto, e, em particular, à presença do museu. Porém, muitos dos que antes condenavam a operação, hoje admitem que a praça tem considerável vitalidade.

O projeto da Praça do MACBA forma parte de um conjunto de intervenções em espaços públicos em Barcelona a partir da década de 80, que criou um modelo internacionalmente reconhecido de desenho urbano. Anteriormente, o espaço se projetava com a intenção de dotar de identidade um lugar determinado com um notável esforço de formalização. Hoje se admite amplamente que a identidade surge com o próprio uso do espaço, constituindo este muitas vezes o suporte capaz de acolher diferentes possibilidades (MARTÍ i CASANOVAS, 2005, p. 122). Um suporte neutro e indefinido facilita ou inclusive incentiva o desencadeamento de usos temporais e atividades imprevisíveis que espaços mais desenhados ou “arquiteturizados”. Atendendo a esta mudança conceitual, podemos afirmar que o suporte da Praça do MACBA, que compartilha traços característicos com outras praças contemporâneas de Barcelona, resulta ideal para o desencadeamento desta prática.

Existe outro fator interessante em relação ao caráter neutro do suporte. Na medida em que não predetermina usos ou atividades, confere versatilidade ao espaço. Dita característica o permite modificar-se repetidamente, constituindo com ele uma ferramenta importantíssima na vitalidade urbana. Ademais, através da indeterminação do suporte surge a possibilidade de se desenhar coexistência no espaço. No exemplo analisado, o suporte demonstrou ser adaptável a solicitações bastante diversas.

De fato a “ordenança” cívica e a repressão policial constituem certo contra-senso, já que representam a tentativa de controlar sua dinâmica natural baseada nas próprias características do espaço. Porque é muito difícil reprimir todas as apropriações espontâneas e inesperadas às quais o espaço urbano está submetido pelos seus próprios usuários, as colonizações imprevisíveis que constantemente o afetam, e que dele fazem um espaço natural de liberdade (DELGADO, 2007).

Referências bibliográficas

AUGOYARD, J. Pas à pas. Essai sur le cheminement quotidien em milieu urbain. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1979.

BORDEN, I. Skateboarding, space and the city. In: Architecture and the body. Reino Unido: Berg, 2001.

CABRERA i MASSANÉS, P. Ciutat Vella de Barcelona: memoria de un proceso urbano. Badalona: Ara Llibres, 2007.

CHASE, J.; CRAWFORD, M.; KALISKI, J. Everyday Urbanism. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1999.

DELGADO, M. La ciudad mentirosa. Madrid: Catarata, 2007.

GARCIA ESPUCHE, A.; GUÀRDIA BASSOLS, M. (selección y textos). Barcelona 1714-1940, 10 plànols històrics. Barcelona, 1994.

GAUSA, M., et al. Diccionario metápolis de arquitectura avanzada. In: Ciudad y tecnología en la sociedad de la información. Barcelona: Actar, 2001.

HAYDN, F.; TEMEL, R. Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces. Basel: Birkhãuser – Publishers for Architecture, 2006.

KRONENBURG, R. “Arquitectura subversiva”. In: Post-it City. Ciudades Ocasionales. Barcelona: CCCB,2008, p. 181-183.

LA VARRA, G. “Post-it City. El último espacio público de la ciudad contemporánea”. In: Post-it City. Ciudades Ocasionales. Barcelona: CCCB,2008, p. 180-181.

MARTÍ i CASANOVAS, M. A la recerca de la civitas contemporània. In: La renovació de l’espai public a Barcelona (1979-2003). 2003. Tese (Doutorado em Urbanismo) - ETSAB/ Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2003.

MARTÍ i CASANOVAS, M. Hacia una cultura urbana para el espacio público: la experiencia de Barcelona (1979-2003). In: Identidades. Territorio, Cultura, Patrimonio. Barcelona: Laboratorio Internacional de Paisajes Culturales, 2005.

PERAN, M. Post It City. Ciudades Ocasionales. In: Post-it City. Ciudades Ocasionales. Barcelona: CCCB,2008, p. 177-179.

RAMONEDA, J. La ciudad del presente continuo. In: Post-it City. Ciudades Ocasionales. Barcelona: CCCB,2008, p. 176.

SABATÉ i BELL, J.; FRENCHMAN, D.; SCHUSTER, J. Llocs amb esdeveniments- Event Places. Barcelona: Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, 2004.

Skateboarding as an intervention: Temporary appropriation and identity in central Barcelona

Adriana Sansão Fontes is an Architect, Researcher in Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, and Professor at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

How to quote this text: Fontes, A. S., 2010. The Skateboarding as an intervention: temporary appropriation and identity in central Barcelona. Translated from Portuguese by Willes Shimo, V!RUS, 04, [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus04/?sec=4&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 18 07 2025].

Abstract

The Plaza de los Ángeles, colloquially called MACBA Square, is today an international reference for street skateboarding. As a public space of civic qualities inserted into a high complexity area, its temporal appropriation has motivated contrary reactions by the local community. Considering that the square already consolidated its identity based on that intervention, what concerns us is to analyze the role of the square space configuration in its temporary appropriation, and the spatial transformations generated by persistence of this practice over time.

Keywords: Skateboarding, public space, temporary appropriation, identity, Barcelona.

Introduction

It is Friday 4pm. The Brazilian, Marcelo and the German, Manfred, together with many skaters from the whole world, slide their skateboards over the extended pavements of the Plaza de los Ángeles. Together with them, more than twenty young practice acrobatic maneuvers taking advantage of the gaps and all kinds of obstacles. Much more people shares of this same space: girls with scooters; an old man and a child playing with a ball; several cyclists who cross it; tourist who take pictures in front of the extensive white façade of the museum; people who rapidly pass, and other people who stops to rest watching the skateboarders movements.

After forty minutes appear a couple of municipal guards. Many of the young do not realize, they are not ‘locals’ and do not know the current civic rules. The more attentive ones warn the group and by dispersing they avoid that the guards confiscate their skateboards. Some resident charges Marcelo and Manfred, while protesting the police delay. An opportunist takes advantage of the confusion to steal the purse of a young lady who is dating distracted. Soon the police go away; the boys go back to their activities, with more people and much more animated. However several neighbors return to complain the constant invasion of the square.

Situations like that occur every day at the Plaza de los Ángeles, internationally known as the MACBA Square, reference for skateboarders from the whole world and, today, reason of controversy in the media and stress between users and residents. It is a very singular public space in a complex urban area, whose appropriation has motivated types of reactions as described.

It is, especially, an exemplar situation of the public space temporary appropriation, which brings out issues such as diversity, multiculturalism, vitality, conflict, contest, reconquest, exclusion, among many other contemporary themes presents in the metropolis space, locus of the expression of plurality, either European or Latin-American, rich or poor.

Reflections about the appropriation

The public space appropriation mechanisms in the contemporary cities, according to Peran (2008, p. 178), reply to two different dynamics that, although not excluding, do not share the same problem. On the one hand, there are practices of survival, and in another, those of dispute for the space. In the first case, we could find many Brazilian examples, our well-known everyday. However, it is the second case that will be approached in this article, because it is more appropriated to the reality of city of Barcelona, context of this work.

The Barcelona case is emblematic because it is a city currently submitted to a progressive policy of urban control. This phenomenon is pointed out by Delgado (2007), one of its fiercest critics of this phenomenon. He refers to the excessively projectual impulse that, when designing the whole city, masks the purpose of filtering complexity, encoding the space and reducing the urban stress. Thus, the current analysis is intended to recognize that the apology to spontaneous appropriations have a close relationship with the super-organized and opulent societies, and with the necessity of developing antagonistic practice, when not literally free (Peran, 2008, p. 177).

Treating spontaneous appropriation of public space means to look at the subversive expressions, against the regulation, the urban control and the planning. Ramoneda (2008, p. 176) highlights that these appropriation forms are elements of inconstancy generated by the own city, normally to the margin of the logics of power and production, and that express new forms of conflict and resistance. However, they should also be understood as indicative signs of possible ways of transformation, since they are expressions of the vivacity of city.

But what means to appropriate?

According to Delgado (2008, p. 192), the public space, as a space for all, could not be an object of ownership, but of appropriation. To appropriate means to recognize as proper, in the sense of appropriated, able to, or suitable to something. Borden (2001), on the other hand, believes that the appropriation is not the simple reuse of a space, but the creative rework of this time-space. The everyday appropriation process of a built space therefore implies some derealization of this space, its creative transformation, and therein resides the essence of collective life in the urban environment. It is defined not only by the opposition between groups, but by a constant stress among spatiality built and opened to the use, and to the rhetorical deconstruction of this space, made for the benefit of the differenced lifestyles expression (Augoyard, 1979, p. 101), and sometimes conflicting. Thus, all indicates that we are facing a transformer fact, of a temporary intervention that results is the injection of vitality in the streets, reacting against the controlled, disciplined and exclusionary city.

In the universe of imaginable spontaneous appropriations, interest us here to work about the street skateboarding in Barcelona. Fundamentally, the choice is due to the trace of contemporaneity of this intervention, nomad, that emerged recently as an overflow of the skateboarding practice in ‘institutionalized’ spaces, and that features in the city a new speed, produces space, time and social posture (Borden, 2001).

Some appropriation dimensions

In a brief theoretical approach before the case exposition, we would like to recover some authors who work with the problem of spontaneous appropriation, emphasizing some dimensions of this practice that may contribute for a multi-faceted vision of the phenomenon and propose advances in the research about the theme.

-the spontaneous, the small and the particular

Crawford (2005) manes as ‘everyday urbanism’ the several activities or ‘attitudes’ before the city that celebrate the everyday richness and vitality, taking advantage of the potentiality and encouraging the use of spaces in an alternative and empirically way. The everyday urbanism is a ‘way of life’ in the physical domain of the routine public activities, the ‘everyday space’, space subjected to appropriation and transformation by the user in a way that better fits the everyday life needs, leading to a re-familiarization.

Under its viewpoint, the city is formed in most by the everyday urbanism than the formal design and official plans, being these not planned activities, spontaneous, a type of architecture in the way they give form to the urban spaces (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett1). Adds that does not exist a universal ‘everyday urbanism’, but a multiplicity of answers for specific times and places. This trace brings up the spontaneous, small and particular dimensions contained in the temporary appropriations.

-the subversive and the active

La Varra (2001) was the first author to coin the term ‘Post-it City’. It equals to the temporary net of functional structures that occupies the interstices of the urban fabric and promotes the temporary writing of the public spaces outside the conventional channels. These temporary ways of space occupation reveal subjective abilities in the task of regaining it against the institutional pressure to which it is submitted, making appropriation a sensor of the latent urban quality.

Due to the spontaneity with which spread in space, that ‘occasional cities’ are seen as resistance forms to normalization of the behavioral patterns, to the spectacle and consumerism of the opulent city, bringing up the subversive dimension of the temporary appropriation. We call subversive at the extent it challenges the current rules, making us to question where does it intended to guide us.

Moreover the subversive dimension, as a space conquest tactic, appropriation reveals its active dimension, its capacity of discovering potentialities, of recovering places or even of ‘poeticizing’ at the urban space. The appropriation has this capacity of putting the space ‘in action’, in movement. We added, so, the subversion and the activation as two more dimensions of the temporary appropriation.

1 In: Chase, J. Crawford, M. and Kaliski, J., 1999. Everyday Urbanism. New York: The Monacelli Press.

We open a parenthesis here. These two forms of appropriation presented, either in the direction of re-familiarization [everyday urbanism] or as space conquest tactic [occasional city], work with the idea of informal, of improvisation and marginality. However it is observed a subtle contradiction at the Post-It proposals. According to La Varra (2008), the occasional behaviors leave no trace [so as not leaves post-it blocks]. But, as potential activators or as space conquest tactics; would be correct affirming they do not leave traces? That is the point on which the central argumentation of this work is based: the temporary leaves marks, and, in this interim, interest either material or immaterial marks. Kronenburg (2008, p. 183) would say that ‘the non-official utilization of determined spaces draws attention to the their value and guide to investments and more formalized improvements’. Despite being temporary, there are evidences that these appropriations can motivate more permanent transformations.

Looking forward, apart from changes that may emerge from the transgressive postures, we reflect if would have in the spontaneous appropriation any transformation intention. What interests here is the appropriation in which is suspected the existence of this intention, even unconscious, that can emerge in some original way of ‘using’ the city. In an atmosphere of indifference and routine, the critical action would work as a revitalizing element (Gausa, 2001), characterized by the willingness to interact, activate, produce, express, move and relate, stirring the spaces and the inertias through ‘happenings’ or ‘events’. Nothing more proper to this universe that the playful impulse of the skateboarding.

-the participative

About the participative dimension, Temel (2006) argues that uses and temporary occupations are currently seen as potentializing tools, revealing new possibilities for the urban spaces.2 By being in the edge of the planning, they act as society self-observers, exploring niches and often presenting themselves as alternatives, power and form of movement for the revitalization of residual and idle areas, inclusive with elastic potential allowing a continuous doing and undoing. He highlights, in this context, the participative character of the spontaneous appropriations, the possibility to put into practice a base planning, motivated by the attitude of ‘do-it-yourself’.

In that way, it is possible to relate the skateboarding to the appropriation dimensions as follows:

|

Spontaneous |

Made by any skateboarder without prior organization / individual and collective expression |

|

Small |

Occupies city fragments, interstices, marginal areas / opposed to the big event |

|

Particular |

Specific to determined context attractive to the skateboarder |

|

Subversive |

Breaks the preestablished rules / uses the city in an alternative way |

|

Active |

Reconquests places / moves the public space creatively |

|

Participative |

Discovers potential places ‘from the bottom to the top’ |

-the relational

Finally, to defend the relational dimension of the spontaneous appropriation, we refer to Sabaté, Frenchman and Schuster (2004). The authors used the term ‘event places’ to analyze the relation between events and places along the time. They defend the existence of a symbiotic relationship between both of that, arguing that memorable events leave marks on the places and shapes the spaces, gradually transforming the city. Focusing in the spontaneous appropriation case and in the skateboarding particularities, we want to prove the existence of this relational dimension between ‘intervention’ and ‘local’, in this case between the skateboarding and the MACBA Square. Through the case study below, it is proposed to reflect about the matter of the square configuration at its temporal appropriation by that “urban folk”, and at the same time about the transformations derived of the persistence of this activity in the time.

Skateboarding at the MACBA Square

As a way to introduce the case study, we indicate below some general aspects of appropriation.

[A] Impulse: Temporary appropriation through the skating practice.

[B] Intention: Totally spontaneous appropriation, without other objective but the own individual and collective expression. Experience the city and interact with its spaces.

[C] Agents: Skateboarders group without prior organization, resident and passersby.

[D] Period: appropriation with no time or regular duration; according to police presence.

The Raval neighborhood in Barcelona and its approximation. Source: Google Earth

The construction of the square

The origin of the Plaza de los Ángeles, located at the Raval, dates from the 19th century. Garriga and Roca present it, in their survey of 1862, as a simple dilatation from the encounter of two streets, Ángeles and Elisabets, with modest size and trapezoidal shape, facing the Convento de los Ángeles chapel. The Cerdá plan affects the area with the proposal for enlargement of some streets like Fernadina and Elisabets, and in the Pere García Faria (1891) plan, some buildings of the calle dels Ángels, near square, disappears, changing slightly its former configuration. Later, the Martorell (1929) survey shows its consecutive enlargement.

The area in 1862, 1891 and 1929. Source: Garcia Espuche and Guàrdia Bassols, 1994

In the 20th century the square kept its original configuration, until in the 80’s, on occasion of the Special Plan of Raval’s Interior Renovation, when it is expanded by demolishing many buildings which occult the Convent, making the square to conform the front of the Casa de la Caritat3 building. In 1993 is finally elaborated a project that will give its actual shape: a wide platform to emphasize the Contemporary Art Museum of Barcelona opened in 1995. The project involves the partial demolition of the Casa de Caritat and other buildings around it as well.

Demolished buildings in the area and Museum Project. Source: Cabrera and Massanés, 2007

This case study will focus in some relevant aspects of this space that allow us to understand the reason of its attractive for the skateboarders and visitors. Refering to categories as insertion in the city, size, typology, architecture and support plan. The wish is to realize the main physical qualities of the place.

[A] Insertion in the city4’

The square is located in a surrounding with a rich heritage, and hosts well several activities. In parallel to its refurbishment, the Convento de los Ángeles was adapted and the Casa de Caritat housed the Contemporary Culture Center of Barcelona, at the same time that residential and commercial uses concentrate on Ferlandina, Joaquin Costa and Elisabets streets. Over the years many cultural uses consolidate in restored buildings, as the already mentioned CCCB and the Fomento de las Artes y del Diseño [FAD], which occupies the former convent, and are also built new buildings as the Facultad de Ciencias de la Información and the Universidad de Barcelona [UB] ones, completing the Montalegre street facade.

2 Debate occurred at the symposium tempo.rar: Temporare Nutzungen im Stadtraum, in Vienna – May 2003.

3 The “Del Liceo al Seminario” study proposes in 1986 the reordering of the Casa de Caritat area and the Illa Misericordia, linking historical buildings, new equipments and public spaces, including the Plaza de los Ángels extent.

4 All the photos and analysis sketches are of the author.

It is a complex area that concentrates predominantly cultural and institutional uses, though inserted in an ancient residential and commercial zone. It was in the last years that the area acquired a remarkable commercial character with the arrival of immigrants and the proliferation of a multicultural commerce, and the increment of the nightlife due to the opening of several bars and restaurants.

Sketch of the square urban insertion. Source: Author.

[B] Size

At Raval we find other squares built in the last fifteen years that form a public space sequence with various uses. But the MACBA’s, a rectangle about 100 x 50 m, is the most and better connected to all of these, which confers some hierarchy over the others.

Comparison of the MACBA square with others Raval squares. Assembling: Author.

Reading of the square flows and permanencies. Source: Author.

[C] Typology

The first feature that draws attention is the magnitude of its practically horizontal plan, delimited by broad vertical surfaces. This seen to be the main project objective: to conform a unitary and uniform space which enhance the monumentablity of the museum. The square conforms, thus, as a large public space set by buildings of miscellaneous features, integrating permanencies both of buildings or open spaces, with considerable size volumes and strong contrast in its appearances, articulation that gives complexity, but also a marked spatial readability (Martí, 2003, p. 11).

Contrast horizontality of the plan with verticality of the surrounding. Source: Author.

Typology of the ‘closed’ square. Source: Author.

[D] Architecture

The square surroundings results of the combination of few big size edifications, which facilitates its perception. The museum impressively rises over the square occupying its entire length, which seems to justify the project intent of creating the square as its complement, assuming the architectonic singularity of the museum and giving it a monumental symbolism. The logic adopted in the square’s project, as part of an intervention strategy on the old town of Barcelona, supposes to trust in the work on the vertical plans [new constructions or restored buildings] for the qualification of the less occupied central space (Martí, 2003, p. 11).

Monumental character of the museum. Source: Author.

Architectonic surrounding. Source: Author.

[E] Support plan

The horizontal plan that accommodates activities is a continuous space, marked with few built elements, which endows it with uniformity and fluidity. The different plans form a whole connected and clean, qualities that give an open character and facilitate its capacity for adaptation.

Continuous horizontal plan. Source: Author.

Space flow. Source: Author.

Skateboarders and neighbors: an announced conflict

As occurred in other cities, in Barcelona from the 80’s the skateboarding overflowed the specialized spaces, where someone imagine that it should be confined, and invaded all the urban space (Borden, 2001, p. 176). As ephemeral activity, it appropriates different fields in cities of the whole world, sometimes just in short periods. And although it constitutes on a much globalized practice, some spaces seem to be especially attractive. The MACBA Square is one of these priority destinations, maybe one of the most important and representative of the whole world.5

But, while the square gains supporters, the neighbors protest the ‘invasion’ of that space. They have already repeatedly alerted the police, made complaints and even constituted an association for defending from the intromission of an activity that they consider prejudicial, gaining the prohibition of the skateboarding practice at the place.

All of this raises some issues relative to the attraction of the place.

What makes it so unique?

Exist in Barcelona several spaces better equipped, with specific facilities for skateboarders.

Why are not so attractive?

5 Numerous web pages proclaim its attractive and incite it to be known and used. A few hours there allow us to distinguish the presence of the skateboarders coming from all sides of the world to share their love.

Why does the square, thought of as a public platform designed to enhance the museum, followed this fate?

Other questions have to do with the social relations that skateboarding implies.

Why this practice disturbs the neighbors?

How do the other collectives react?

Finally, other questions have being related with the character and the vitality of this space.

In what other ways it is used?

How do organize the activities and sub-fields?

What consequences has the activity for the space and for the whole neighborhood?

We will risk a first interpretative hypothesis: the physical characteristics of space focus in its destiny, but, a lot more of some less tangible elements, as its atmosphere [mix of tissues, ancient and contemporary buildings, patina of time, complexity, spatial surrounding], or the fact of being a non-appropriated space in search of identity. This seems to have facilitated the place to turn into a living space, unlike squares of similar shapes and projectual logics.

After considering the origin and conformation of the square, we will analyze the skateboarding characteristics in order to evaluate the interests and transformations that relate space and event.

Skateboarding at the MACBA Square

Barcelona has already obtained international widespread recognition among the skateboarding practitioners. Large part of the city, fundamentally the new streets, is considered ‘skatable’ by having broad surfaces, horizontal and with no obstacle [or with small and attractive obstacles]. All of it favored the apparition of skaters in different parts of the city.

The skateboarding, as spontaneous activity, usually explore determined physical space, discovering different possibilities from those for which the space was created (Borden, 2001, p. 29). Apart of the original idea, what is the first thing that comes to our mind when we think about the MACBA Square? For all of that who minimally knows it, almost certainly would be the presence of the skateboarders. In fact the square, that naturally was not designed to settle this practice, was discovered and appropriated by this specific group.

According to the leading scholars, the arrival of the skateboarders to a new space use to be followed by its appropriation and contribution to conform a particular identity (Borden, 2001, p. 53). In the absence of previous identity, this space use to be temporarily re-formalized through the uses that accommodate, starting to express new meanings from the individuals or groups that appropriates it (Crawford, 1999, p. 28).

We understand for identity a series of characteristics by which a place is recognizable, in other words, its specificity or differences in relation to other places. In the case of MACBA Square we can admit that its identity is given by the presence of skateboarders. This finding comes from the general identification that the activity has with this space, culminating in the public reactions of the neighborhood in favor of a territory that looks like ‘their’.6

The appropriation of the area dates from 1995. In that time the square – recently built – had no use and was an empty and dangerous space. However, it became to be intensely used by local skateboarders, when skateboarding in Barcelona was not yet a ‘fashion’. In parallel, there was, aside, a large empty area, later occupied by the University of Barcelona, where some local skateboarders used to practice. From the year 2000, with the arrival of people from elsewhere, the square turned into what it is today.

Many interviewed skateboarders confessed they became aware of the square from movies that circulate on the web, and that its world relevance led them to travel to meet it. One of the biggest attractive seems to be the possibility of knowing skateboarders from different origins and change experience and impressions with them.

The square is today a “appropriated” space by practitioners from the whole world. We fell into the temptation of attributing on an exclusive character this powerful attraction – its “skatable” qualities – to the fact of having extensive horizontal surfaces, including quite suggestive obstacles. But, in Barcelona this qualities are not exclusive of this space. Many others recent places also have such attributes, typical of a “minimalist” design stage. On the other hand, seems to exist in the Square other characteristics that may have had a more decisive role in the appropriation.

The interviews with skateboarders reveal other attributes that contribute to conform a clear identity: its typology of “closed” square, without much contact with the streets, its contemporary and clean aspect, its “hard” and empty surface [open to unpredictable uses], or even its origin perceived as marginal. Somehow it is believed that this place had been “discovered” and converted today in a international landmark. Let us focus on that attraction capacity.

About the attraction of the places to the skateboarders

A first aspect that could focus on its attraction would be the broad granite surface, flat and without obstacles. However, in many other squares with similar characteristics, as, for example, the squares of Gracia, there are no skateboarders. Lets think that the urban activity of skating is a way to experiment the city and its architecture, and that it uses different elements as “jumpable” objects (Borden, 2001, p. 265). The MACBA Square has some of practitioners preferred elements, like ramps and stairs, such as other seductive gaps in the pavement. But these elements are also found in other public spaces of the city.

Certainly there must be other qualities not so evident that make this place singular among the skateboarders. To discover it, we interviewed the square users and recognized a range of reasons for such success. Let us try discovering where lies its attractive following the same patterns used to analyze it before.

[A] Insertion in the city

From the areas appropriated by skateboarders, the most popular are the central squares: MACBA, Universidad and Tres Chimeneas. As skaters do not like isolation, a location next to flows is an attractive factor. The central and connected disposition of MACBA Square enables intense contact with the passersby, specificity emphasized by skateboarders as a base of its huge popularity.

6 The use-local identification in this case is so deep that is not necessary, for instance, using interviews or other methods of research, since either the ‘fame’ of the space or the conflicts with the neighborhood are widely documented on the internet or in Barcelonan media.

[B] Size

The space dimension is a key feature. A space of big dimensions [about five thousand squared meters] enables a bigger variety and coexistence of activities with no big interferences. It allows the realization of stunts without affecting other activities developed in the square.

[C] Typology

Other attractive characteristic of the square is the permeability. Although it looks closed, it is directly linked to important pedestrian pathways, so the skateboarders can escape with the skateboard in many directions. Other relevant characteristic is the absence of automobiles, the square configuration as a place for pedestrians. At the squares of Gracia this seems to be one of the reasons of non-appropriation, since they are surrounded by streets where cars circulate.

[D] Archtecture

A less commented observation reminds us the presence of the museum. As the practice of skating can also have an artistic [and subversive] connotation, in some occasions it is produced an unconscious interaction with the contemporary art museum. The non-existence of directed linked habitation with the square, of cultural and institutional profile, also contributes for the activity, again differentiating of the cited squares of Gracia.

[E] Support plan

Finally, the aspect that seems most relevance is the repeated mention to the spatial simplicity. A “clean, with a few elements” surface invites to the skating. Regarding to “jumpable” elements, the specificity of the square is that the seats, steps and sills delineate “pictures” in the “space” of the skateboarders enabling several tracks. Ramps and stairs link different levels, and have proper height to the basic stunts. Also were mentioned the area’s polyvalence, where is possible to make various moves. It offers a lot of possibilities including, when tired of practice, to sit down and rest.

Some other attributes, like having an illuminated area at night, contribute to the persistence of the activity. A last singularity of the appropriation, according to many of those interviewed, is the possibility of mixing experienced and novice skaters. The square enables a sharing among different levels of skateboarders, but also the coexistence with a lot of other urban practices, emphasizing the democratic dimension of space and its non-colonization by a single activity, allowing further the development of social relationships among different users.

The perspective of other users

As every area susceptible to the emergence of conflict, the Square enables the development of several relationships among different groups of people. Usually when the conflicting activities respect a space division, tacit or not, the coexistence gets equilibrated and the intense use of the space enriches it. On the contrary, when the capacity of several groups to accommodate their activities and share a space is not sufficient to manage the conflicts, the spatial equilibrium is broken.

The analysis of relations between event and space at the Square is realized, apparently, in a delicate moment of instability on the social agreements to share it. The neighbors complain openly on the current use of the square based on two arguments: first, they consider that skating prevents the good use of the space by local community, mainly children and the elderly. Moreover, the considerable noise made disrupts the silence and tranquility of a so particular place.

The skateboarders accept that their activity wears and, in some cases, dirties the space. As every broad activity, it attracts all kinds of users, from the more respectful to the “wildest” ones. Moreover, admit that skateboarding, while appropriating of almost all urban elements available, contribute to this wear.

The older residents do not like that the square had changed to what it is today. On the other hand, for the younger, more prone to socialization, the skating environment looks more attractive. And yet, the coexistence between skateboarders, tourists and regular users seem to be very pacific, with no big apparent conflicts or even with a appreciable inter-relationship, if we observe the plenty of people that accommodate daily in the gaps to observe the activity. To them skateboarding is a real spectacle, as it is in a similar sense, to see all sorts of character passing by the Rambla. A similar seduction happens to the kids. What is noticed, far from the rejection, are friendly gestures. Finally, the regular pedestrian which only use the square as a route no usually pay attention to the activities, on the contrary, seem to try to escape of the habitual route of the skateboarders as a way of avoiding possible impacts.

Other conflicts observed affect the bicycles, maybe they are who most disturb, on that case, the skateboarders themselves. The conflict usually appears when they jump the gaps as the bicycles pass. On this conflict nobody comes to an agreement, since both believe to have the preference.

The shopkeepers interviewed recognized the increase of frequency in the area and, as a consequence, the increase in security. For them, the activity does not bring any bother. To the representatives of the museum, what really matters to them is keeping free the upper platform access, representing no severe problem the activity at the lower part. However, other voices would not say the same thing. For many, the activity can disturb more the museum than the own neighbors.

Summarizing: the area is not free of conflicts. According to the skateboarders themselves, the conflicts frequency occur, but never seriously, and they believe that is perfect manageable. On the other hand, the residents complain to the City Hall since they don’t want to live with conflicts. The police frequently patrol, but because they do not stay the whole day, they are not effective on enforcing regulations. The museum vigilant, who intend to the law application, try to suppress the practice, but with no success. Unconcerned, tourists and users keep enjoying the vitality and intense urban experience the square provides.

Good part of the place’s vitality comes from the skateboarding practice. Other people use it, which means not to be a colonized place but an area able to receive several activities. However, most of the people that uses it relates in one way or another with the practice.7 The uses of the square and its surrounding have to do with the cultural equipments and with the original residential character of the Raval. Thus, besides the skateboarding, which does not follow predetermined times or dates, can be observed the development of many others activities, both permanent and ephemeral.

The first ones are related to the balconies of bars, always occupied and from where it is possible to observe the square activities. The ephemerals are distributed in many ways at different edges of the square. The higher field in front of the museum is a kind of amphitheater, where usually small groups observe the skateboarders, talking or waiting some date. Others, usually related to skateboarding, crowd near to the library, observing or waiting to step in. Occasionally dances are also celebrated in the square: groups of people usually put music in the lower and more reserved part.

The passersby flow is very intense, since the square is very permeable and channels a lot of routes. Moreover, it is the spot for removal and return of the bicycles public system, which has a lot of movement on this area, not to mention the tourist attracted by the unique cultural equipments.

Uses and conflicts of the square – Source: Author.

About other ‘skatable’ spaces of Barcelona