Galpões de triagem: uma abordagem espacial arquitetônica

Fernando Freitas Fuão é Arquiteto, Professor Associado da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul e Coordenador dos Grupos de Pesquisa 'Galpões de triagem: arquitetura, design e educação' e 'Arquitetura expressionista no Brasil'.

Bruno César Euphrasio de Mello é Arquiteto e Mestre em Planejamento Urbano e Regional.

Camila Bernadeli é Arquiteta e Pesquisadora em Geografia na Universidade Federal de Uberlândia.

Antonio Pedro Figueiredo é Educador Popular e Pesquisador na Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul.

Como citar esse texto: FUÃO, F. F. et al. Galpões de triagem: uma abordagem espacial arquitetônica. V!RUS, São Carlos, n.4, dez. 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus04/?sec=4&item=8&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 30 06 2025.

Resumo

O presente artigo traz à superfície a problemática do lixo, dos catadores e recicladores dentro da cidade, das péssimas condições arquitetônicas a que esses trabalhadores estão submetidos no seu cotidiano de trabalho nos galpões de triagem. Propõe a abordagem do lixo desde os temas da territorialidade, ordem-desordem, centro-periferia. Introduz no universo arquitetônico dos galpões de reciclagem através de um breve panorama da reciclagem em Porto Alegre. Explica o zoneamento espacial dos galpões, e exemplifica com breves análises arquitetônicas de três galpões: Associação Profetas da Ecologia, Associação de Recicladores da Vila dos Papeleiros e a Associação do Hospital São Pedro, desde a ótica tipológica e de seu funcionamento.

Palavras-chave: tipologias dos galpões de triagem, recicladores, resíduos sólidos.

Figura 1: Vista interna do Galpão de triagem Rubem Berta. Porto Alegre. 2008. Foto de Marcelo Heck.

“As moscas são os anjos da miséria,

estão em toda parte, escoltando o apodrecimento.”

Carpinejar

Catadores e recicladores

Hoje a profissão de reciclador já é reconhecida pelo Governo Federal, mas o conhecimento do ‘que é‘, e ‘onde’ se realiza esse trabalho, ainda é desconhecida por grande parte da população, e dos arquitetos. A problemática do lixo questiona e convida a participação dos arquitetos junto aos recicladores.1 Desenhar a coexistência junto aos catadores e recicladores implica no conhecimento de seus cotidianos de trabalho e vidas, e de que forma se pode melhorar as condições de trabalho e ganhos nos galpões de triagem. Coexistir num mundo kaleidoscópico é reconhecer as diversidades dos indivíduos, grupos e comunidades, e sobretudo criar as possibilidades de diminuir as diferenças indesejáveis promovendo as igualdades e direitos necessárias dentro dessas diferenças.

Desenhar a coexistência é deslocar o pensamento em direção ao outro e seu entendimento, repensar a ordem e o sentido dos espaços, redesenhar os saberes a partir da lógica desse ‘outro’ que trabalha com o descarte.

De uma maneira geral, as diferentes sociedades sempre tiveram uma relação de afastamento com os resíduos por elas produzidos. O lixo é freqüentemente associado com quem trabalha com ele, aos moradores de rua e aos catadores. O lixo está associado também à ordem e à desordem. Portanto, dizemos que isso está no campo da arquitetura e da cidade. Balandier, em seu livro A desordem, elogio ao movimento,2 explicou que a desordem e o caos não estão somente situados, num lugar, eles estão também exemplificados. Essa topologia imaginária associa-se a um conjunto de figuras, personagens que manifestam sua ação dentro do próprio espaço policiado, vigiado. Nessa perspectiva, não só o lixo, mas também as pessoas que trabalham com ele surgem como figuras de desordem. Figuras que são banalizadas e repletas de ambivalência por aquilo que delas é dito e do que elas designam, são objetos de desconfiança e medo em razão de sua diferença, de sua situação e margem, são geralmente os primeiros suspeitos e as vítimas de acusação, certamente, não são invisíveis como querem algumas teorias. Figuras que arrastam outras figuras como a violência, a doença, a fome.

O próprio fenômeno da catação e da reciclagem do lixo acaba por explicar a desordem da ordem moderna. O (i)mundo.

O lixo é muito mais que um subproduto da sociedade atual, ele retrata e amplifica a própria estrutura da sociedade produtivista em que vivemos. O lixo sempre existiu, mas em abundância como vemos hoje, é um fenômeno dos últimos anos. Ele é o retrato mais fiel da sociedade de consumo e da superficialidade de uma sociedade que prioriza as embalagens em detrimento do conteúdo. Embalagens foram inventadas para que os produtos pudessem durar mais e viajar longas distâncias. A vida embalada.3

O conhecido artista Armam nos anos 50-60, e outros neo-realistas, assim como Gordon Matta-Clark, já haviam percebido o potencial do lixo, do rejeito, da matéria enquanto coisa falante da ação do ser humano na sociedade atual. Armam fazia o que ele chamava de “retratos” de seus amigos: entregava para eles lixeiras circulares e transparentes, onde colocavam todos os rejeitos, todo o lixo produzido, dia a dia. Esses materiais, ao fim e ao cabo, deveriam retratar e/ou representar parte do indivíduo tal como uma fotografia. Com esse processo, Armam demonstrava que o homem na atualidade, é um grande produtor de lixo, e não mais precisa ser representado por sua fisionomia, mas sim pelos próprios objetos que produz, consome e descarta.

Quem vive do lixo explica não só sua condição de exclusão, sua desterritorialização, o avesso do ser humano, mas também a cadeia exploratória humana de cabo a rabo. A atividade de catação não é nova, é bastante antiga, Baudelaire falava dos trapeiros em Paris, no século XIX. Em todo caso, ela ao longo da história aponta o não direito ao uso da cidade por parte de quem limpa o mundo, e vive das sobras.4

Entretanto, o fenômeno da catação, exercida por milhares de pessoas puxando carrinhos pela cidade afora, ou separando lixo dentro dos galpões de reciclagem, é novo e até então nunca vista.

Essas pessoas que viviam segregadas e escondidas na periferia, na periferia da periferia cinza, de repente, invadiram os centros e as ruas das cidades com seus carrinhos. Esses ‘desconhecidos’ apareceram de uma forma nova, como um acontecimento, um evento que chega em carrinhos para mostrar, anunciar o não visto. É justamente esse ‘outro’ outrora oculto - que arrasta mitologicamente o temor e o medo - que de alguma forma nos livra, da culpabilidade do desperdício e da responsabilidade com os rejeitos que jogamos fora. Esses catadores e recicladores representam a fonte do inesperado, são o próprio acontecimento (event) que atenta contra o curso natural das coisas, contra a própria ordem das cidades. Na verdade, eles são os anunciadores do futuro incerto, apresentam-se pelas ruas carregando a intolerância do (i)mundo em seus carrinhos. São o futuro escondido dos homens que dele não se sentem mais donos, que se apresenta como um potencial perturbador, como observou Balandier.5

“Por meio de sua lentidão, eles se fazem notar. Levam as ruas e os carros a novos ritmos, com o intuito de questionar a lógica da aceleração.”6

Ao longo da história, ao se afastar o lixo e ao colocá-lo para fora das relações de uma sociedade asséptica e hierarquizada, ele foi necessariamente aproximando-se daqueles que viviam às margens das cidades, fora dos muros, nas vilas, na periferia da periferia, nos limites das cidades, no cinza. Sempre se expulsou para as periferias os rejeitos da cidade, como forma de separação, de eliminação. Essa periferia cinza, de certa forma apartada da cidade, é o lugar do despejo e do abrigo para milhares. É o lugar onde se deposita tudo que, para alguns, é feio e cheira mal, que é violento e perturbador. O lixo tem uma dimensão ética espacial e conseqüentemente estética, geralmente não considerado.

Associamos ordem ao centro e ao que está ao seu redor, desordem ao periférico. O lixo enquanto lixo em seu estado de despejo é pura desordem. Reorganizar o lixo é função dessas pessoas: que foram excluídas da potência da cidade e agora retornam.

O deslocamento da gigantesca quantidade de lixo e sua trajetória dentro da cidaderevelam a importância dele enquanto objeto de investigação da cidade e da arquitetura, como rastro da superficialidade da vida, e organização das cidades. O lixo, enfim, assume para os arquitetos um papel questionador dos binômios de centralidade-periferia, dentro-fora, e da tríade: ordem, beleza e limpeza.

Bauman, ao comentar sobre a instabilidade e fluidez das relações humanas na modernidade, em O amor líquido utilizou-se da produção do lixo para exemplificar essas relações:

Se lhes perguntassem, os habitantes de Leônia, uma das cidades invisíveis de Ítalo Calvino, diriam - que sua paixão é desfrutar coisas novas e diferentes. De fato. A cada manhã eles vestem roupas novas em folhas, tiram latas fechadas do mais recente modelo de geladeira, ouvindo jingles recém-lançados na estação de rádio mais quente do momento. Mas a cada manhã as sobras da Leônia de ontem aguardam pelo caminhão de lixo, e cabe indagar se a verdadeira paixão dos leonianos na verdade não seria o prazer de expelir, descartar, limpar-se de uma impureza recorrente. Caso contrário, por que os varredores de rua seriam recebidos como anjos, mesmo que sua missão fosse cercada de um silêncio respeitoso, o que é compreensível: ninguém quer voltar a pensar em coisas que já foram rejeitadas (BAUMAN, 2004, p.11).

Esses “anjos ultramodernos” que se deslocam das periferias ao centro, de um lado ao outro da cidade carregando centenas de quilos de papelão, de garrafas PET e latinhas de alumínio, por onde passam, não só higienizam, mas deixam o rastro da “existência nua“. São eles que, ao se exporem fazem a comunicação entre esses mundos imaginários: o visto e o não visto. Ao incorporarem-se dentro do núcleo urbano, desfazem, em certo sentido, a dicotomia de um dentro e de um fora, de um incluído e de um excluído, de um centro e uma periferia.

A periferia, hoje, se apresenta como o locus da possibilidade da mudança, da renovação que vem de fora para dentro, tal como uma invasão bárbara, bárbara! Paradoxalmente, o periférico, às vezes está dentro, embaixo, de nossos pés, nos baixios dosviadutos.7

Essa periferia é também o lugar da revelação e da reação, da inovação, o lugar onde se localizaram muitos dos Galpões de Triagem.

Breve Histórico dos Galpões de triagem em Porto Alegre

Se a complexidade e intensidade do processo de catação e triagem variam de local para local, as condições de trabalho nos galpões são em geral quase todas iguais e desumanas.

1As informações aqui apresentadas são extraídas da pesquisa Unidades de Triagem, um estudo sobre normativas e tipologias arquitetônicas. Fuão, Fernando (coordenador), CNPq, UFRGS, PROPESq, PROREXT, 2003-2010. A pesquisa estuda, analisa, avalia e propõe alternativas aos Galpões de Triagem existentes em Porto Alegre. Participaram e ou participam também da pesquisa os estudantes: Bruno César Euphrasio de Mello, Camila Bernadelli, Camila Rocha, Marcelo Heck, Thiago Wondracek, Fernanda Antonio, Ananda Kuhn, Ágata Carvalho, Lucas Weinmann, Agata Muller, Fernanda Schaan, Michele Raimann e Antonio Pedro Figueiredo . O presente artigo tem o objetivo de apresentar ao leitor uma visão básica e introdutória ao universo arquitetônico dos galpões de reciclagem.

2 BALANDIER, G. A Desordem, elogio ao Movimento. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 1977. p. 48

3 FUÃO, F. F. A vida embalada. Inscritos no Lixo, 2009. Disponível em: <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com>. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

4 A Historia de la mierda ilustra bem essa relação escatológica com a estrutura urbana, no qual o desperdício é fruto da tríade ordem-beleza-limpeza que fundamentaram as cidades e a língua a partir do século XVI. Veja-se: LAPORTE, D. Historia de la mierda. Valencia: Pre-textos,1988.

5BALANDIER, op. cit, p. 38

6MOEHLECKE, V. Corpos da cidade: territórios e experimentações. ARQTEXTO, n. 7, 2005. Disponível em: < http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Vilene%20Moehlecke.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

7Veja-se a excelente pesquisa de Carlos Teixeira, Flavio Agostini e Luciana Cajado, Projeto baixios de viadutos da via expressa leste-oeste, em Arqtexto n.7. A prancheta eletrônica. Ano VI, n.2 (2005). Propar. UFRGS. p.42-48. Sobre o tema da utilização dos espaços ociosos dos viadutos, veja-se também Fuão, Fernando. Sob Viadutos em <http://www.fernandofuao.arq.br> e <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com>.

Em Porto Alegre, segundo Pedro Figueiredo, antigo coordenador da Associação Profetas da Ecologia, existem “três momentos que foram importantes na trajetória do lixo. Ao final dos anos 90, começou nas grandes cidades um tipo de coleta seletiva, desarticulada e com uma ausência total de uma política pública disciplinada, ordenada. O lixo era coletado e levado diretamente para os “lixões”. Além daqueles trabalhadores que estavam em cima dos lixões, que eram muitos, muitíssimos, existiam aqueles que andavam de porta em porta, já muitas décadas atrás, ambos sobrevivendo da coleta. Até algumas décadas atrás, o lixo não era considerado uma matéria valiosa. Nos últimos anos, em várias cidades, mais precisamente em alguns Estados, criou-se, após uma intensa luta de articulação e cooperativismo o Movimento Nacional dos Catadores, e no Rio Grande do Sul a Federação. As famílias no centro e nos bairros residenciais acabaram criando vínculos de solidariedade com esse pessoal. Eles não levavam somente o lixo para casa em seus carrinhos, mas levavam comida, roupa, caderno para os filhos. A dona de casa ou empregada guardava, porque sabia que no outro dia teria o “seu fulano” que tinha um rosto, e chegaria a sua porta. Ela conhecia seus filhos, suas necessidades. Mas quando as prefeituras assumiram o controle da coleta seletiva, ordenando, essas relações interpessoais foram sendo cada vez mais suprimidas.8

Num segundo momento, as prefeituras das grandes cidades passaram então, a assumir o controle da gestão da seletividade do resíduo sólido de uma forma planejada. Os caminhões da Prefeitura começam a percorrer rotas de coleta que até então eram alternativas à compactação existente, e assim se foi construindo um sistema de gerenciamento no seu conjunto, não só do reciclável, mas de todos os resíduos. Começa, então, a construção dos galpões de triagem por parte da Prefeitura.

Um terceiro momento é a “explosão” do lixo dos últimos dez anos. O desemprego, aliado com a ampliação da capacidade de absorção por parte da indústria da reciclagem, lançou milhares à cata de tudo que é encontrado. Tem uma brincadeira que diz que “catador não rouba, ele cata tudo que encontra pela frente”. Hoje, temos em Porto Alegre dezesseis Galpões de reciclagem oficializados.9

Passado mais de 15 anos sobrevivendo, os galpões de triagem e suas associações não ‘quebraram’ estão em contínua crise. Isso não é só um problema de Porto Alegre, mas de todo Brasil e do Terceiro Mundo.

Poderíamos acrescentar que também apareceu um novo tipo de “empresário”, como se refere Márcio Magera,10 que recolhe o lixo e o disputa diretamente

com o sistema público. Ele constrói galpões clandestinos, compra o material do catador que precisa de dinheiro de forma imediata. A

indústria precisa de quantidade; os galpões, muitas vezes, não tem a quantidade suficiente, já não conseguem triar o material que chega,

sua produtividade é alta, mas sua rentabilidade é baixa. Aparece então à figura do atravessador que tem a logística da estocagem, compra

um pouco de cada um e faz o volume. Portanto, atende a escala que a indústria precisa, e assim consegue negociar melhor

e obter melhores preços de venda. A Federação das Associações de Recicladores do Rio Grande do Sul (FARRGS) ou o Movimento Nacional dos

Catadores (MNC) surgem nesse contexto de organização dos trabalhadores em Porto Alegre.

Sobre legislação ambiental existem muitas leis, decretos e normas reguladoras, portarias. Instruções normativas e resoluções que abordam e sinalizam uma política nacional de meio ambiente, mas a verdade é que a arquitetura dos galpões de triagem nunca foi suficientemente reconhecida na problemática da reciclagem do lixo, e muitas vezes até menosprezada a sua importância em face das necessidades mais emergentes dos catadores. Mesmo dentro de outras áreas da ciência como Administração, Educação, Sociologia, Psicologia que estudam esse tema, ela permanece inexpressiva nesse processo. Com freqüência, a importância da arquitetura e do espaço não comparecem diretamente como item referencial na “política do lixo”.11

Os recicladores trabalham dentro de um espaço físico, passam a maior parte do tempo de seus dias nesses lugares, e

infelizmente a maioria desses espaços não apresenta as condições mínimas de habitabilidade. Mesmo os modelos de galpões construídos pelas

prefeituras acabaram por demonstrar um grande desconhecimento da dimensão espacial-social dos catadores e de seus comportamentos. Tudo

isso resultou nos espaços mal projetados, e por sua vez acabaram refletindo-se nas relações sociais e produtivas dos catadores.

A política do lixo tem sido abordada enfaticamente desde o aumento da produtividade, e dos ganhos do ponto de vista

monetário, escamoteando as necessidades sociais desses trabalhadores, aniquilando os potenciais humanos que essas cooperativas

autogestionárias possam apresentar e desenvolver em suas experiências como programas de alfabetização, inclusão digital entre outros. Na

maioria dos galpões de triagem inexiste um estudo efetivo sobre o planejamento do espaço, uma administração do espaço, um espaço da

administração. Sabe-se que o espaço e sua organização são fundamentais na produção, mas os discursos coletivos dos cooperados, e de todas

as parcerias dos galpões, infelizmente, desconhecem a importância de uma vida pensada em torno do espaço.

Esses espaços deveriam incorporar, por exemplo, refeitórios corretamente instalados e alocados com referência às zonas de triagem, pias e lavatórios, vestiários para os catadores, salas para a produção de artesanato a partir do lixo, e toda uma quantidade de proposições para esses galpões, a serem criadas a partir das análises e vivências dos arquitetos. Infelizmente, diante de todas essas possibilidades de reconstrução das identidades, da cidadania de quem cata papel e não tem papel. A arquitetura não tem comparecido nos discursos centrais ou periféricos, pois permanece sem papel também.

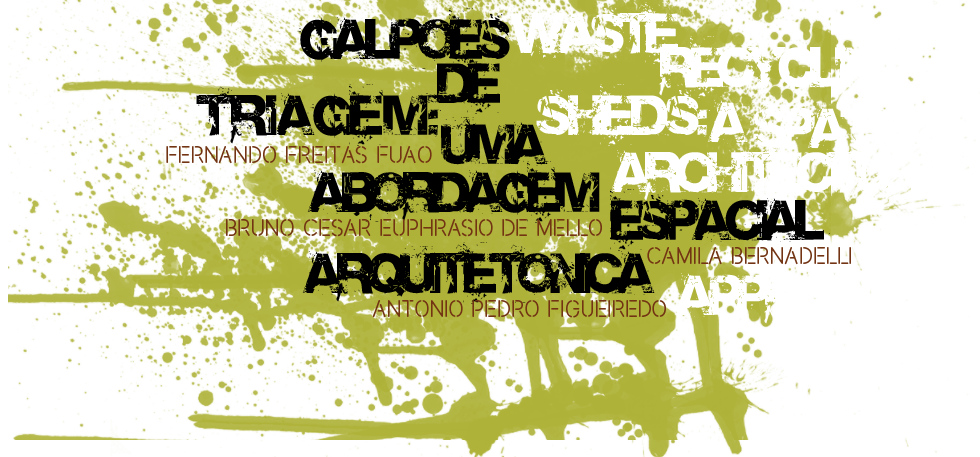

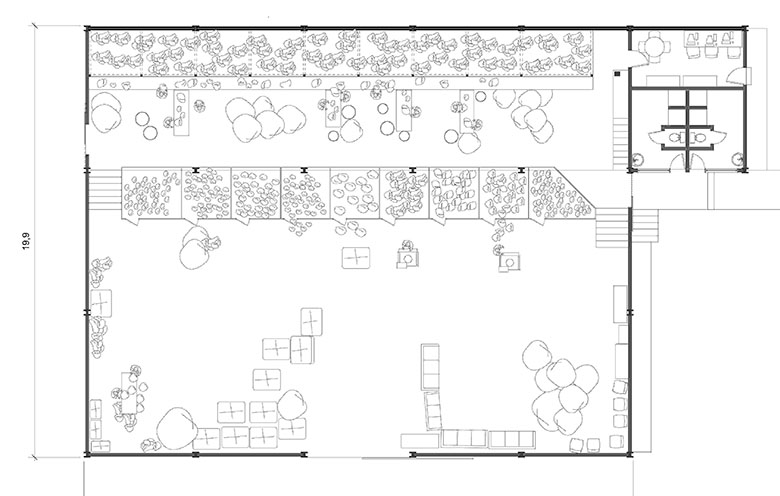

Figura 2: Planta baixa do galpão de triagem ARLAS, Canoas (RS). Desenhos por Thiago Wondracek e Marcelo Heck.

Os galpões

Durante o período 2003-2010 foram realizadas visitas sistemáticas a vários Galpões de reciclagem na grande Porto Alegre12, revelandouma realidade até então desconhecida para a maioria dos arquitetos.Quem já teve a oportunidade de conhecer algum galpão de triagem de lixo sabe bem das condições de insalubridade e habitabilidade desses espaços. Acreditamos que a vivência e a convivência são o caminho para começar a entender esse fenômeno. Para nós existe uma relação muito direta entre corpo e arquitetura, entre espaço de trabalho e produção. Tudo passa pela arquitetura, pois enfim a arquitetura é o envoltório da existência.

O fenômeno da triagem é ainda recente para o conhecimento acadêmico, e os galpões que se formaram em todo Brasil, na ultima década,

quer sejam eles construídos pelas municipalidades, ou pelas próprias associações de recicladores, nunca incorporaram um

planejamento mais aprimorado do espaço. Seus promotores não se preocuparam com as condições de trabalho, fecharam os olhos para a

insalubridade em meio à tamanha miséria.

Entendemos que a arquitetura se constitui numa das mais antigas e eficientes máquinas produtivas, nela revelam-se todas as virtudes e insuficiências.

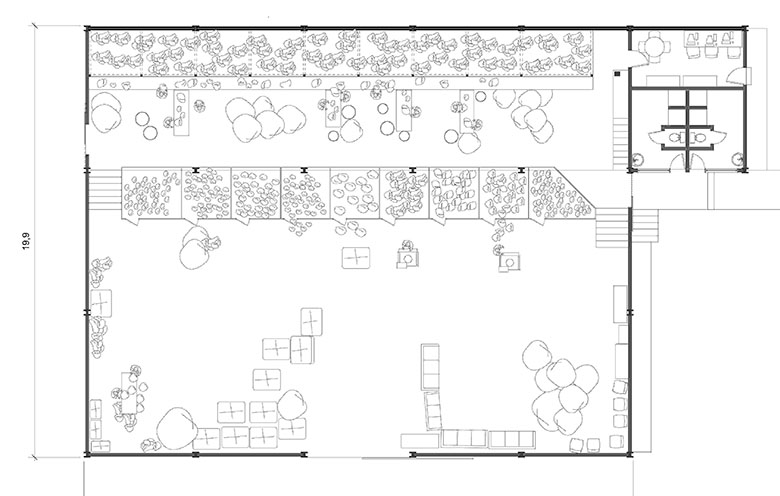

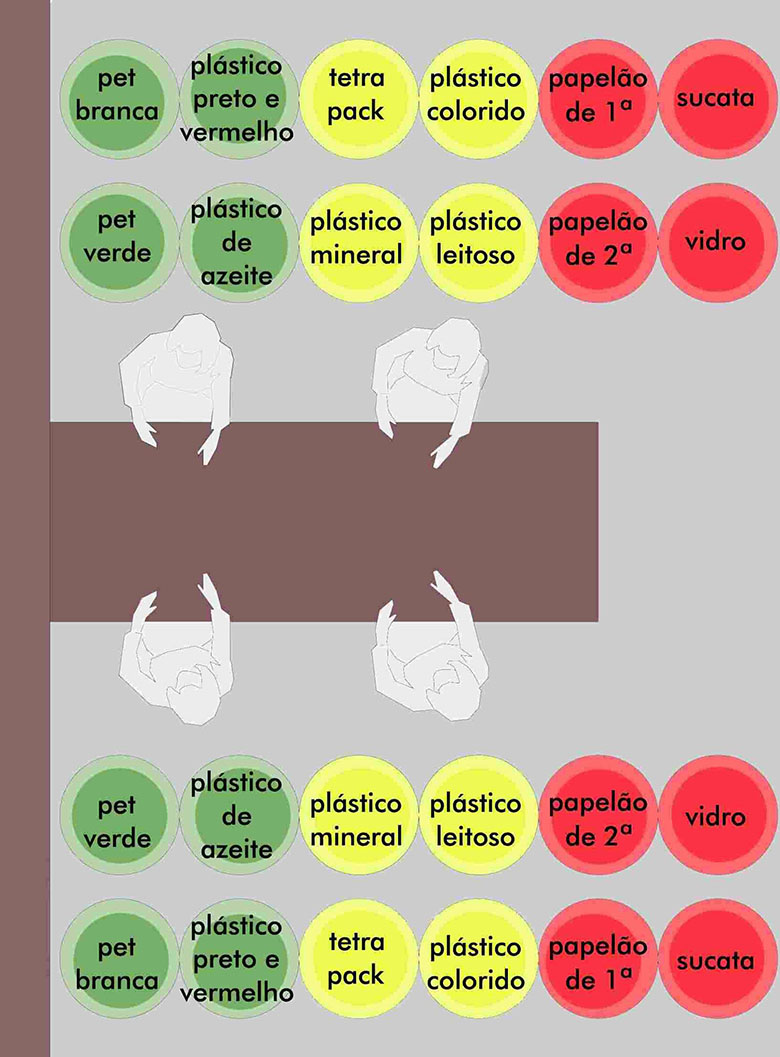

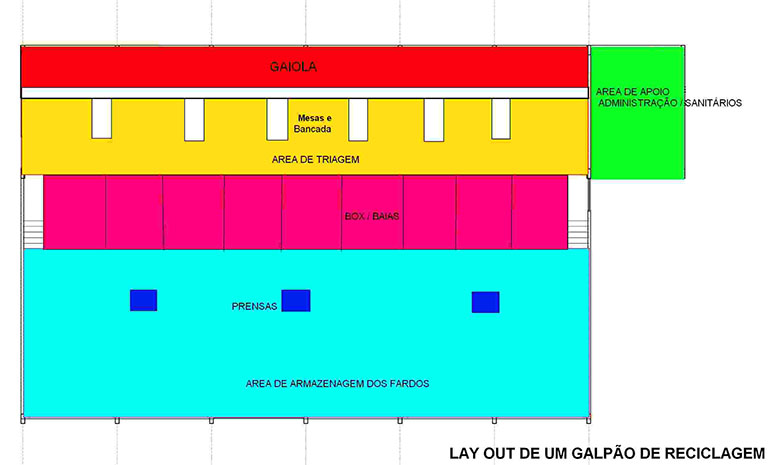

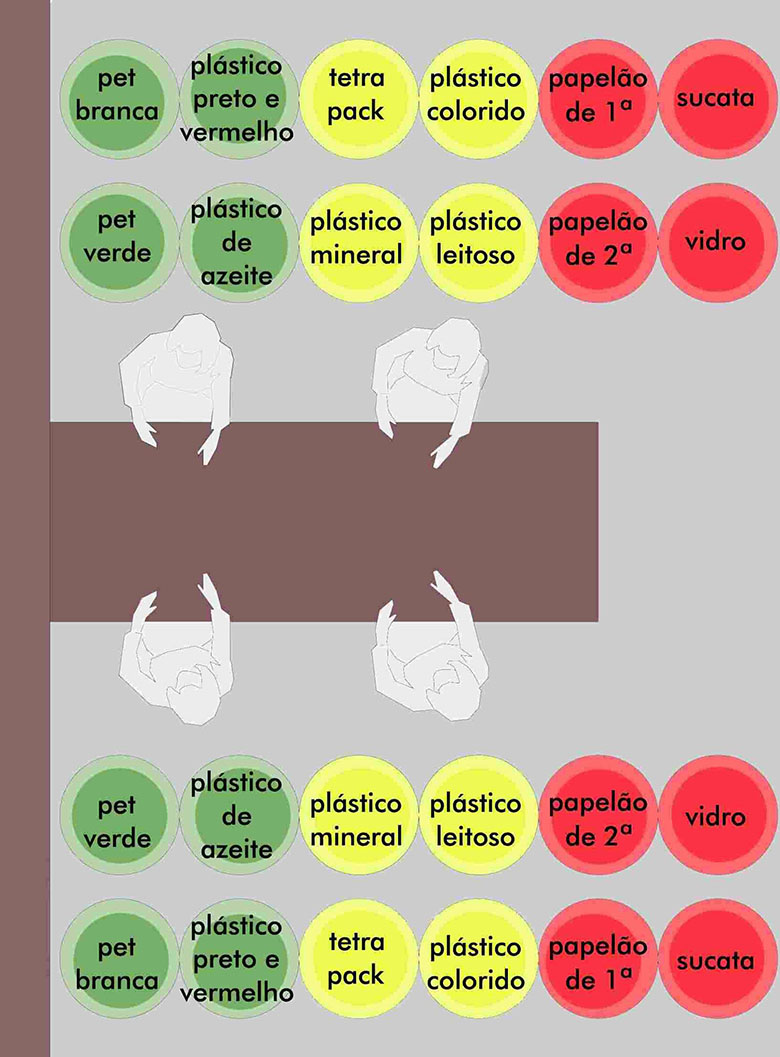

A grosso modo, o funcionamento e layout de um galpão de reciclagem compreende uma seqüênciade etapas e movimentos de produção: o caminhão da Prefeitura descarrega o material (lixo) nas gaiolas, depois de descarregado o material é retirado pouco a pouco, sacola a sacola, para ser aberto e separado sobre as mesas de triagem, cada material separado é jogado nas bombonas ou tonéis correspondente, a figura do bomboneiro trata de recolher as bombonas cheias e descarrega nos boxes (pequenas gaiolas onde se reúne o material selecionado: caixas de tetra pack ou garrafas pet verde), dali o material é retirado e levado para a prensa. Depois de prensados, os fardos são estocados a espera do comprador que chegará com o caminhão.

Figura 3: Diagrama de funcionamento de um Galpão de triagem. Desenho por Fernando Fuão.

Inicialmente nossas primeiras anotações se centraram sobre o ponto de vista das condições arquitetônicas e tipológicas. A maioria das

Unidades de Triagem nunca tiveram projeto inicial, exceto as construídas pela Prefeitura. Tipologicamente podemos definir esses espaços

em três tipos básicos de ocupação: galpões, utilização de baixios de viadutos, e ocupações de prédios abandonados.

Os galpões se organizam através desse zoneamento de triagem por faixas ou manchas, espaços setorizados que, em muitos casos, não obedecem a uma lógica de produtividade mais apurada. Em muitos galpões há erros de encaminhamento de material desde a entrada até a saída, ou seja: não há uma linearidade do processo produtivo, e a disposição dos equipamentos de triagem muitas vezes é equivocada.

O que inicialmente se tem observado é que esses galpões de triagem construídos pelas Prefeituras foram construídos de qualquer

maneira, sem um conhecimento mais apurado dos anseios e formas de trabalho dos catadores, desconsiderando questões básicas de

habiitabilidade. Esses galpões em poucos anos apresentaram péssimas condições estruturais e funcionais, alguns deles não

passavam mesmo de precários telheiros.

Em sua maioria, possuem uma implantação bastante questionável, em terrenos acidentados, com declividade acentuada, ou

partindo de um conceito inicial duvidoso que prioriza a carga e descarga do material trazido pelo caminhão, formando patamares, em

detrimento do deslocamento dos trabalhadores dentro do galpão.

Há problemas de toda espécie, por exemplo: a iluminação de trabalho em todos é equivocada, a zona de triagem (mesa e bancada) dos trabalhadores volta-se para as aberturas localizadas frontalmente, provocando ofuscamento e cansaço visual. Não há iluminação artificial complementar, porque, freqüentemente, não há dinheiro para repor as lâmpadas.

Na seqüência, a título descritivo e analítico, destacamos três galpões de reciclagem em Porto Alegre: Associação Profetas da Ecologia, Associação de Reciclagem Hospital São Pedro, e a Associação de Recicladores da Vila dos Papeleiros (AREVIPA).

Figura 4: Vista do Galpão principal do Profetas da Ecologia 1. Foto de Fernando Fuão.

Figura 5: Vista sob o viaduto com os pequenos volumes, galpão do Profetas da Ecologia. Foto Fernando Fuão.

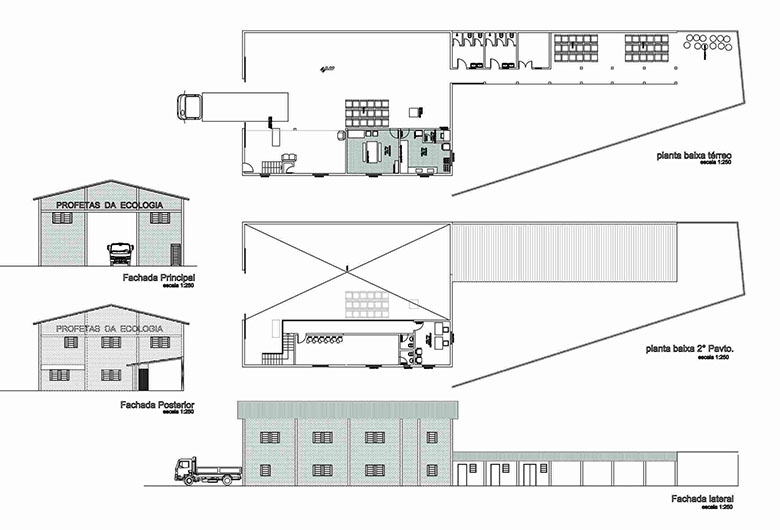

A Associação Profetas da Ecologia (1994) foi um dos galpões pioneiros em Porto Alegre e está localizado num pequeno espaço nos baixios dos viadutos na entrada da cidade, conhecido como o Viaduto da Sertório, uma área residual caótica gerada pela implantação dos emaranhados de viadutos e da rede férrea do trensurb.

Atualmente as condições de habitabilidade e higiene do Profetas são ainda bastante desfavoráveis. O Profetas da Ecologia, hoje com uma média de 30 associados, é constituído por diversas pequenas edificações construídas ao longo desse tempo. Há o grande galpão retangular que foi construído durante a fundação da Associação, onde localiza-se a cozinha e o refeitório que se abrem diretamente para a zona de triagem e estocagem do lixo, nesse mesmo prédio, no mezanino, situa-se uma sala de aula, uma sala administrativa e dois banheiros.

8Sobre o cotidiano dos Galpões de reciclagem indico os artigos de Antonio Pedro Figueiredo, Traições tolerantes, histórias de um tempo em que tentávamos reciclar gentes e coisas, em http://historiasdepedras.blogspot.com/

9FIGUEIREDO, P. Unidades de Triagem decíduos Sólidos, um estudo tipológico e normativo. Depoimento. Relatório de Pesquisa, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). CNPq. Porto Alegre, 2005. 87 p.

10MAGERA, M. Os empresários do Lixo, um paradoxo da modernidade. Campinas: Editora Átomo, 2003.

11Vide, por exemplo, o Edital do CNPq (2007) de auxílio aos catadores que nem sequer contemplou o item espaço-arquitetura, dando prioridade para esteiras, prensas e outros equipamentos.

12 Entre os galpões levantados arquitetonicamente destacamos: Centro de Estudos Ambientais da Vila Pinto (CEA), Associação de recicladores da Vila dos Papeleiros.- AREVIPA, Associação Profetas da Ecologia 1, Associação Profetas da Ecologia 2, Associação Novo Cidadão, Associação de recicladores Hospital São Pedro, Galpão de reciclagem Rubem Berta, Galpão da Cavalhada, Galpão da Restinga, Galpão da Lomba do Pinheiro, Galpão da ilha dos Marinheiros, Galpão Passo Dornelles, Galpão da Santíssima na Vila Dique, Galpão Padre Cacique, ARLAS (Canoas), Galpão de reciclagem Passo Dornelles (Viamão), ACATA (Ijuí), ARPES, ARCELE, ASCOVI (Santa Maria), Associação Jardim Glória e Associação Esperança (Bento Gonçalves), Interbairros (Caxias do Sul)

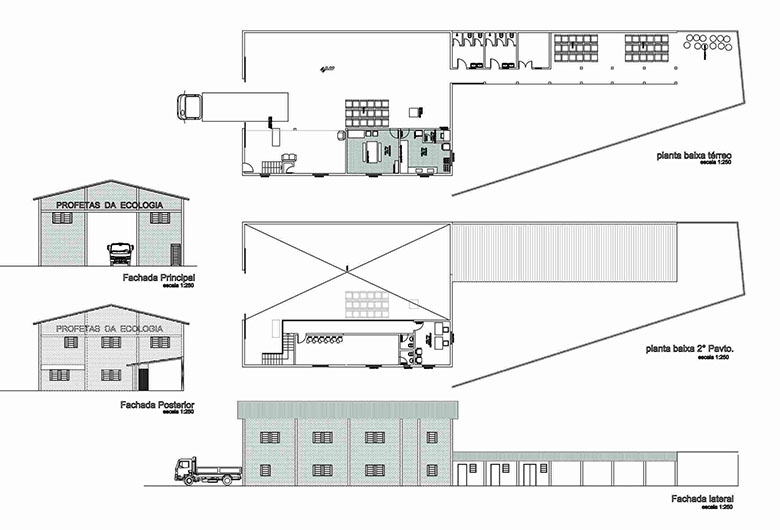

Figura 6: Profetas da Ecologia. planta baixa do galpão principal. Desenhos de Camila Bernardelli e Camila Rocha.

Na parte da frente do conjunto, embaixo dos dois viadutos que passam por cima do terreno, existem, além de um novo galpão que foi construído para retirar o lixo do antigo galpão, outras duas pequenas edificações que foram construídas através de um acordo entre o Profetas e a Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre. Um dos prédios que eles chamam de “box” é constituído por dez cubículos, “garagens” que serviriam inicialmente para os carrinheiros que quisessem separar o seu lixo independentementee não em cooperativa. O outro é um pequeno conjunto de sanitários e chuveiros.13

Figura 7: Vista externa do Galpão de triagem do Hospital São Pedro. Foto de Bruno Cesar E. de Mello

Figura 8: Interior do Galpão de Reciclagem do Hospital São Pedro. Foto de Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

O galpão de triagem da Associação de Reciclagem Hospital São Pedro faz parte do complexo de edifícios do Hospital Psiquiátrico São Pedro, localizado na Av. Bento Gonçalves, Porto Alegre. Esta associação se diferencia das demais porque nela trabalham alguns pacientes do Hospital que se utilizam desse trabalho de triagem como terapia e tratamento. A associação utiliza-se da metade de um antigo galpão preexistente e subutilizado, situado na parte mais baixa do grande terreno do Hospital São Pedro. Internamente, existe uma baia de armazenamento de papéis, delimitada por grades metálicas e subdividida em baias menores, está no centro da planta, como uma ilha, e todas as atividades ocorrem ao seu redor. Entre esta e as gaiolas de armazenamento do lixo que chega da rua estão dispostas quatro mesas de triagem de diferentes dimensões.

À direita de quem entra está instalada a cozinha e um pequeno escritório da Associação. A cozinha configurando-se como um local de

sociabilização e troca de idéias. Infelizmente, a porta abre-se, para a zona de triagem, como no Profetas da

Ecologia.

Figura 9: Vista interna do Galpão da AREVIPA, Porto Alegre. Foto de Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

Figura 10: Vista do Telheiro AREVIPA. Foto de Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

A Associação dos Recicladores da Vila dos Papeleiros (AREVIPA) agrupa os recicladores que trabalham de forma coletiva no Galpão recebendo material da coleta seletiva, assim como os carrinheiros (catadores), independentes, também moradores da Vila dos Papeleiros, mas não associados, que trabalham sob um telheiro. Assim, o conjunto da Arevipa compõe-se de duas grandes edificações: um galpão já existente e um novo telheiro.

O galpão existente é uma edificação retangular onde se dá a triagem. Fazem parte desse grande espaço interno, também uma cozinha, algumas saletas e um espaço adjacente onde ficam as prensas.

O acesso dos caminhões do que trazem o lixo da coleta seletiva é feito por um grande portão quase no meio do galpão. Fica à esquerda dessa entrada a gaiola de armazenagem do material a ser triado. Três mesas de madeira destinadas a triagem estão apoiadas nela, na volta delas uma dezena de bombonas destinadas a recolher os diferentes materiais.

O outro volume, o grande telheiro, é uma estrutura das vigas e pilares pré-fabricados em concreto armado sem nenhum tipo de fechamento ou divisórias internas que protejam os inúmeros carrinheiros das intempéries. A dinâmica no telheiro se dá da seguinte maneira: os carrinheiros individualmente recolhem o material reciclável do centro da cidade e dos bairros vizinhos, levam-no até o telheiro onde é triado em pequenas mesas improvisadas ou mesmo no chão, e depois vendido para o atravessador. O aspecto deste local de trabalho é de um caos generalizado. São muitas sacolas de lixo, carrinhos, fardos, pequenas mesas de triagem e inúmeros homens e mulheres trabalhando, indo e vindo num ritmo intenso. Entram e saem pessoas com seus carrinhos a todo o momento. Chegam com elas suas crianças pequenas que, pela impossibilidade de seus pais colocarem-nas em lugar mais adequado, ficam por ali, catando coisas para brincar nos montes de lixo e de sacolas plásticas. Tudo isso num espaço onde fica difícil, para quem vem de fora, definir onde começa ou termina o espaço de trabalho de um grupo, quais são os materiais para triagem deste ou daquele trabalhador. Fica difícil distinguir qual é a ordem por eles estabelecida para esse grande espaço de trabalho.

Sugestões para os Galpões de triagem

Enfim, entendemos que uma análise dos galpões e dos critérios para elaboração de um projeto para galpões de reciclagem deva passar por diversas indicações que devem ser levadas em conta como: número de trabalhadores envolvidos, horas de trabalho, forma de divisão dos lucros, volume de material trabalhado, condições arquitetônicas do edifício quando já existente, adequação ao terreno, topografia, acessibilidade de pedestres e de caminhões, sistema de carga e descarga, trajetória e deslocabilidade do lixo e de suas classificações dentro do Galpão, bem como avaliação dos equipamentos quanto a localização e características de uso (mesas, bancadas, esteiras, balanças, elevadores). Por exemplo, as mesas de trabalho com 4 ou 6 trabalhadores são mais produtivas, que a solução da grande bancada com os associados trabalhando individualmente. Além desses, pode-se incluir: avaliação quanto à insolação, iluminação natural e artificial, ventilação, umidade, odores, contato com material tóxico, normas de segurança com relação à maquinaria, etc. Assim como condições dos materiais utilizados na construção em pisos e paredes, normas de segurança de incêndio e, principalmente saúde. Deve-se, também, no mesmo grau de importância ou superior, considerar ainda os espaços comuns como: refeitórios, salas para outras fontes de geração de renda como oficina de papel, costura, espaços culturais, artesanato, escritórios administrativo, salas para alfabetização e computadores, pequenas salas de projeção/cinema, como é o caso do Centro de Estudos Ambientais da Vila Pinto, em Porto Alegre.14

Figura 11: Exemplo de mesa de triagem com 4 associados. Desenhos de Agata Muller e Lucas Weinmann

Conclusões

No universo dos galpões de triagem foi possível perceber que há uma série de razões e necessidades que vão além da arquitetura, antes mesmo de chegar à questão espacial e tipológica existem muitos obstáculos de gestão, questões importantes de gênero, psicologia de grupo, microfísicas do poder, todas essas coisas acabam repercutindo no espaço.

Percebe-se uma falta de preocupação por parte dos trabalhadores em relação às condições arquitetônicas básicas dos Galpões, uma despreocupação com a ordem, a organização do espaço e da produção. O mais paradoxalé que associamos a desordem a quem realmente trata de ordenar o material atirado fora, inclassificável. Na verdade, o que os catadores fazem é domesticar a desordem produzida pela devoração da sociedade consumista, pela sociedade do desperdício. Mas no imaginário da sociedade, ao se aproximarem do lixo, aoestabelecer uma relação simbiótica entre eles, é como se apropriassem do mal, do execrável, do escatológico, formando um par perfeito. Enfim, escamoteando a culpabilidade de quem a produziu.

A ordem, hoje, é o consumo, o encaixotamento da vida, as embalagens, o desperdício, o excesso, o embalado.

A ordem e a desordem, inclusão e exclusão, são como duas faces de uma moeda; são indissociáveis e com freqüência encontramos um dentro do outro, reenviando seus significados um ao outro. São dois aspectos ligados ao real, que arrastam o próprio conceito de sentido. A ordem é o sentido, a desordem o sem sentido. E não nos parece à toa que a nossa civilização pareça algo sem sentido, que todos reclamem a falta de sentido.

Nas mesas de triagem são separados, juntados, classificados e prensados os sentidos da sociedade de consumo que foram jogados fora. Depois eles são enfardados para posteriormente serem triturados, esfacelados, tornarem-se matéria mesmo sem significado, até que seja reintroduzidos novamente sobre uma nova forma, um novo sentido, uma nova embalagem. A isso, ironicamente, chamamos reciclagem. O único problema é que essas novas matérias são, em sua maioria, embalagens, coisas sem sentido, que ficam esvaziadas de qualquer conteúdo logo após serem consumidas. São objetos representativos da sociedade descartável e toda essa reordenação da reciclagem volta a se tornar desordem pelo próprio movimento da falta de sentido.

Referências

BALANDIER, G. A Desordem, elogio ao Movimento. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 1977.

BAUMAN, Z. O amor líquido, sobre a fragilidade dos laços humanos. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editores, 2004.

FIGUEIREDO, P. Unidades de Triagem de Resíduos Sólidos, um estudo tipológico e normativo. Depoimento. Relatório de Pesquisa, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). CNPq. Porto Alegre, 2005. 87 p.

FIGUEIREDO, A. P. Traições tolerantes, histórias de um tempo em que tentávamos reciclar gentes e coisas.historias de pedras, 2009. Disponível em: <http://historiasdepedras.blogspot.com/>. Acesso em 15 ago. 2010.

FUÃO, F. F.; ROCHA, E. (orgs.) Galpões de reciclagem e a Universidade. Pelotas: Editora da Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL), 2008.

13 Sobre a Associação Profetas da Ecologia veja-se: Mello, Bruno Cesar Euphrasio. Espaços de triagem de resíduos sólidos na cidade de Porto Alegre. O caso da Associação Profetas da Ecologia II e outras reflexões, em http://www.vitruvius.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp465.asp.

14 Sobre o tema dos Galpões de Reciclagem no Rio Grande do Sul, veja-se : FUÃO, F. F.; ROCHA , E. (orgs.) Galpões de reciclagem e a Universidade. Pelotas: Editora da Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL), 2008.

FUÃO, F. F. A vida embalada. Inscritos no Lixo, 2009. Disponível em: <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com>. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

FUÃO, F. F. Sob Viadutos. Fernando Fuão, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.fernandofuao.arq.br>. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

LAPORTE, D. Historia de la mierda. Valencia: Pre-textos, 1988.

MAGERA, M. Os empresários do Lixo, um paradoxo da modernidade. Campinas: Editora Átomo, 2003.

MELLO, B. C. E. Espaços de triagem de resíduos sólidos na cidade de Porto Alegre: O caso da Associação Profetas da Ecologia II e outras reflexões, Vitruvius, 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.vitruvius.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp465.asp>. Acessado em: 15 ago. 2010.

MOEHLECKE, V. Corpos da cidade: territórios e experimentações. ARQTEXTO, n. 7, 2005. Disponível em: < http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Vilene%20Moehlecke.pdf >. Acessado em: 15 ago. 2010.>. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

TEIXEIRA, C.; AGOSTINI, F.; CAJADO, L. Projeto baixios de viadutos da via expressa leste-oeste, ARQTEXTO, n. 7, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Carlos%20Teixeira.pdf>. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2010.

Waste recycling sheds: a spatial architectural approach

Fernando Freitas Fuão is an Architect, Associate Professor at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and Coordinator of research groups: "Waste Recycling Sheds: architecture, design and education" and "Expressionist architecture in Brazil".

Bruno César Euphrasio de Mello is an Architect and Master in Urban and Regional Planning.

Camila Bernadeli is an Architect and Researcher in Geography at Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brazil.

Antonio Pedro Figueiredo is a Popular Educator and Researcher at Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

How to quote this text: Fuão, F. F. et al, 2010. Waste recycling sheds: a spatial architectural approach. Translated from Portuguese by Anja Pratschke, V!RUS, 04, [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus04/?sec=4&item=8&lang=en>. [Accessed: 30 06 2025].

Abstract

This article brings to surface the issue of trash, of the garbage collectors and recyclers in the city, the bad architectural conditions that these workers are subjected in their daily work in the Waste Recycling Sheds. It proposes to approach the trash from the themes of territoriality, order-disorder, center-suburb. It introduces the architectural universe of the Waste Recycling Sheds with a brief overview of recycling in Porto Alegre. Explains the spatial zoning of the Waste Recycling Sheds, and illustrates brief analyzes of three facilities: Association Profetas da Ecologia, Association of the Vila dos Papeleiros and the Association of the Hospital São Pedro, from the typological perspective and its functioning.

Keywords: Typologies of Waste Recycling Sheds, recyclers, solid waste.

Figure 1: Internal view of a Waste Recycling Shed, Rubem Berta. Porto Alegre. Photo by Marcelo Heck.

"Flies are the angels of misery,

they are everywhere, escorting the rotting."

Carpinejar

Collectors and recyclers

Today the profession of recycler is already recognized by the Federal Government, but the knowledge of 'what is', and 'where' is performed this work, is still unknown to many of the population and architects. The problem of solid waste questions invites the participation by architects together with the recyclers.1 Designing a coexistence with the collectors and recyclers implies the knowledge of their daily work and lives, and how the working conditions and earnings can be improved at the Waste Recycling Shed. Coexisting in a kaleidoscopic world is to recognize the diversity of individuals, groups and communities, and above all create the potential for diminishing undesirable differences by promoting the necessary equalities and rights within these differences. Drawing the coexistence is to move toward each other and their understanding, to rethink the order and meaning of space, redesigning the knowledge from the logic of this 'other' who works with discard.

In general, different societies have always had a relationship of keeping distance with the removal of waste they produce. Garbage is often associated with those who work with it, the homeless and the collectors. Garbage is also associated with order and disorder. Therefore, we confirm that it is in the field of architecture and the city. Balandier, in his book The disorder, praise of the movement2, explained that the disorder and chaos are not only located in one place, they are also exemplified. This imaginary topology is associated with a set of figures, characters who express their action within an own controlled and monitored space. From this perspective, not only garbage but also the people who work with it emerge as figures of disorder. Figures, that are trivialized and full of ambivalence by what is said of them and what they designate, are objects of suspicion and fear because of their difference; their situation and margin; they are usually the first suspects and victims of prosecution; certainly, they are not invisible like some theories want it. Figures that drag other figures such as violence, disease, hunger. The very phenomenon of collecting and recycling of waste ends up by explaining the disorder of the modern order. The dirty.

Garbage is more than a byproduct of modern society; it depicts and amplifies the very structure of the productive society we live in. It has always existed, but the abundance as we see today is a phenomenon of recent years. It is the more faithful picture of the consumer society and the shallowness of a society that priories the packaging rather than its content. Packaging was invented so that the products could last longer and travel long distances. A packed life3.

The renowned artist Armam in the 50ties and 60ties, and other neo-realists, like Gordon Matta-Clark, had already noticed the potential of the waste, the waste as a talking thing of a human action in the society today. Armam did what he called "portraits" of his friends: he presented them with circular and transparent bins, where they put all the waste, all the garbage, produced day by day. These materials, after all, should portray and / or represent part of the individual such as a photograph. With this process, Armam showed that the human being at present, is a major producer of waste, and no longer needs to be represented by his physiognomy, but by the very objects that he produces, consumes and discards.

Who lives from garbage not only explains his condition of exclusion, his deterritorialization, the other side of the human being, but also the exploratory human chain from the beginning to the end. The collecting activity is not new, it is pretty old, Baudelaire spoke in the nineteenth century of ragpickers in Paris. In any case, throughout history it shows not the right to use the city by the person who cleans the world, and lives off the leftovers4.

However, the phenomenon of picking, practiced by thousands of people pulling carts throughout the city, separating trash or inside of Waste Recycling Sheds, is new and hitherto unseen.

These people who lived segregated and hidden in the suburb, the gray suburb of the suburb, suddenly invaded the centers and city streets with their carts. These 'unknown' appeared in a new way, as a happening, an event that arrives on carts for display, advertising the unseen. It is precisely this 'other' formerly hidden, mythologically trailing fear and dread - that somehow free us of guilt of the wastage and the responsibility with the garbage we throw away. These collectors and recyclers represent the source of the unexpected, are the actual happening (event) that goes against the natural course of things, against the very order of cities. In fact, they are the harbingers of the uncertain future; present in the streets carrying the intolerance of the dirty in their carts. They are the future hidden from the human beings of which no longer they feel owners, that presents itself as a potentially disturber, as noted Balandier.5

"Through their slowness, they are remarkable. They take new rhythms to the streets and cars, with the intention of questioning the logic of acceleration."6

Throughout history, moving away from the trash and putting it out of the relations of a hierarchical and aseptic society, it was necessarily approaching those who lived on the margins of cities, outside the walls, the neighborhoods, in the suburb of the suburb, within the limits of cities, in the gray. Always it drove to the outskirts the rejects of the city, as a form of separation, of elimination. This gray suburb, somewhat apart from the city is the place to dump and shelter for thousands. It is the place where all is deposited that, for some, is ugly and smells bad, it's violent and disturbing. The garbage has an ethical dimension and therefore aesthetic, usually not considered.

We associate order to the center and what is around you as suburban disorder. The garbage as garbage in its state of dump is pure disorder. Rearrange the garbage is function of these people: which were excluded from the power of the city and now return.

The displacement of the huge amount of garbage and its trajectory within the city reveals its importance as an object of investigation of the city and its architecture, as the trace of the superficiality of life and the organization of cities. The garbage, finally, assumes for architects a questioning role about the binomials of centrality - suburb, inside-out, and the triad: order, beauty and cleanliness.

Bauman, commenting on the instability and fluidity of human relations in modern times, in his book Liquid love used the production of garbage to illustrate these relationships:

The residents of Leonia, one of Italo Calvino´s Invisible Cities, would say, if asked, that their passion is ‘the enjoyment of new ad different things’. Indeed – each morning they ‘wear brand-new clothing, taken from the latest model refrigerator still unopened tins, listening to the last-minute jingles from the most up-to-date radio’. But each morning ‘the remains of yesterday´s Leonia await the garbage truck’ and one is right to wonder whether the Leonians’ true passion is not instead ‘the joy of expelling, discarding, cleansing themselves of a recurrent impurity’. Otherwise why would street cleaners be ‘welcomed like angels’, even if their mission is ‘surrounded by respectful silence’, and understandably so – ‘once things have been cast off nobody wants to have to think about them further (Baumann, 2003, p.11).

These "ultramodern angels " moving from the suburbs to the center, from one side to another of the city, carrying hundreds of pounds of cardboard, plastic bottles and aluminum cans, wherever they go, not only sanitize, but leave the trail of "naked existence." They are, by exposing themselves, that what makes the communication between these imagined worlds: the seen and unseen. By incorporating themselves within the urban core, they break, in a certain sense, the dichotomy of an inside and an outside, of an included and an excluded, of a center and a suburb.

The suburbs, presents itself today as the locus of the possibility of change, of renewal that comes from outside, as a barbarian invasion, barbaric! Paradoxically, the suburb, sometimes is inside, underneath our feet, in the shallows of the expressway overpasses7.

This suburb is also the place of revelation and response of innovation, where many of the Waste Recycling Sheds were located.

Brief history of waste recycling sheds in Porto Alegre

If the complexity and intensity of the process of collecting and sorting vary from place to place, working conditions in the sheds are generally almost all the same and inhuman. In Porto Alegre, according to Pedro Figueiredo, former coordinator of the Association Profetas da Ecologia, there are "three moments that were important in the history of the garbage. By late 1990 began in large cities a kind of selective collection, disjointed and with a total absence of a disciplined organized public policy. The garbage was collected and taken straight to the dumps. In addition to those workers, who were on top of the dumps, which were many, very many, there were those who walked door to door, since many decades ago, both surviving of the collecting. Until a few decades ago, garbage was not considered a valuable material. In recent years, in various cities, and more precisely in some states, the National Movement of Collectors was created after an intense struggle of articulation and cooperativism, and the Federation in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. Families in the center and in the residential neighborhoods ended up creating ties of solidarity with those people. They not only took home the trash in their carts, but also food, clothing, notebook for the children. A housewife or housekeeper kept them, because she knew the other day would appear "her guy" who had a face, and come to her door. She knew his children, their needs. But when local governments took control of the selective collection, ordaining, these interpersonal relations were increasingly being suppressed8.

In a second moment, the municipal governments of large cities were then to assume management control of the selectivity of solid waste in a planned way. The trucks of the local government start to travel collection routes that were previously alternatives to existing compaction, and thus was build a management system as a whole, not only recyclable, but of all waste. It begins then the construction of the Waste Recycling Sheds by the City.

1 The information presented here is drawn from the study "Units of Separation, a study of regulatory and architectural typologies." Fuão, Fernando (coordinator), CNPq, UFRGS, PROPESq, PROREXT ,2003-2010. The research aim is to study, analyze, evaluate and propose alternatives to existing Waste Recycling Sheds in Porto AlegreParticipated or are participating students in the survey: Euphrasie Bruno César de Mello, Bernadelli Camila, Camila Rocha, Marcelo Heck, Thiago Wondracek, Antonio Fernando, Ananda Kuhn, Agate Carvalho, Lucas Weinmann, Agata Muller, Fernanda Schaan, Michele Raimann and Antonio Pedro Figueiredo.This article aims to present the reader with a basic overview and introduction to the architectural universe of recycling sheds.

2 Balandier, G.,1997. A Desordem, elogio ao Movimento. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, pp. 48

3 Fuão F. F., 2009. A vida embalada. Inscritos no Lixo, [blog] 16 March, Available at: <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com/2009/03/vida-embalada-fernando-freitas-fuao-1-o.html> [Accessed 15 August 2010]

4 The Historia de la Mierda illustrates well this eschatological relationship with the urban structure, in which the waste is the result of order-beauty-cleaning triad that founded the city and the language from the sixteenth century on. See: Laporte, D., 1988. Historia de la Mierda. Valencia: Pre-textos.

5 Balandier, op. cit., pp. 38

6 Moehlecke, V., 2005. Corpos da cidade: territórios e experimentações. [online] ARQTEXTO N. 7. Available at: < http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Vilene%20Moehlecke.pdf > [Accessed 15 August 2010], pp. 65

7 See the excellent research of Carlos Teixeira, Flavio Agostini and Luciana Cajada, Projeto baixios de viadutos da via expressa leste-oeste, in Arqtexto n.7. A prancheta eletrônica. Ano VI, n.2 (2005). Propar. UFRGS. pp. 42-48. On the topic of the use of the shallows of the expressway overpasses, see also Fuão, Fernando. Sob Viadutos at <http://www.fernandofuao.arq.br>, and <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com>.

8 About the daily life at the recycling sheds, we indicate Antonio Pedro Figueiredo, Traições tolerantes, histórias de um tempo em que tentávamos reciclar gentes e coisas, In http://historiasdepedras.blogspot.com/

A third moment is the "explosion" of garbage in the last ten years. Unemployment, coupled with the expansion of absorptive capacity on the part of the recycling industry, has launched thousands in search of whatever is found. There is a joke that says " collector does not steal, he picks whatever is ahead." Today, we have in Porto Alegre sixteen official Waste Recycling Sheds9.

After surviving more than fifteen years, the recycling sheds and their associations did not 'break', but are in continual crisis. This is not just a problem of Porto Alegre, but all over Brazil and the Third World.

We might also add that it appeared a new type of "entrepreneur", as stated by Márcio Magera10, who collects the garbage and disputes it directly with the public system. He builds illegal sheds, buys the material from the collector, who needs money immediately. The industry needs quantity; often, sheds do not have enough quantity, since they are no longer able to separate the material that arrives. Their productivity is high, but their profitability is low. So, the figure of a middleman appears, who has the logistics of storage, buys a little of each one and makes the volume. Therefore, he responds to the scale that meets industry needs, and so can negotiate better prices and better sales. The Federation of Associations of the Recyclers of Rio Grande do Sul (FARRGS) or the National Movement of Collectors (MNC) arise in this context to organize workers in Porto Alegre.

On environmental legislation there are many laws, decrees and regulatory standards, ordinances. Regulatory instructions and resolutions that address and signal a national policy on environment, but the truth is that the architecture of the recycling sheds has never been sufficiently recognized in the problem of recycling waste, and have often even be underestimated by their importance in light of the more emerging needs of the collectors. Even within other scientific fields such as Administration, Education, Sociology, Psychology studying this topic, it remains insignificant in this process. Often the importance of architecture and space do not appear directly as a reference item in the "politic of garbage."11

The recyclers are working within a physical space, spend most of their time of their days in this places, and unfortunately most of these spaces do not have the minimum conditions of habitability. Even the models of sheds built by local governments ultimately demonstrate a considerable lack of the social-spatial dimension of the collectors and their behaviors. All this resulted in poorly designed spaces, and in turn ended up being reflected in the social and productive relations of the collectors.

The politic of garbage has been taken up strongly from increased productivity, and its profit from a monetary perspective, concealing the social needs of these workers, annihilating the human potential that such worker-owned cooperatives are able to produce and develop in their experiences as for example literacy programs, digital inclusion among others. In most recycling sheds, an effective study does not exist about the planning of space, a management of space, a space of management. It is known that space and its organization are essential in production, but the collective discourse of the members, and all partnerships of the sheds, unfortunately, are unaware of the importance of a life defined by the space.

These spaces should incorporate, for example, correctly and allocated installed canteens with reference to the areas of separation, sinks and washbasins, cloakrooms for the collectors, rooms for the production of crafts from waste, and a whole number of propositions for these sheds, to be proposed from the analysis and experience of the architects. Unfortunately, given all these possibilities for the reconstruction of identities, of the citizenship of who picks paper and does not have a role. The architecture has not appeared in central or peripheral speeches, for remaining paperless as well.

Figure 2: Floor plan of the waste recycling shed ARLAS, Canoas (RS). Drawing by Thiago Wondracek and Marcelo Heck

The sheds

During the period between 2003-2010, systematic visits were carried out to various recycling sheds in Porto Alegre12, revealing a reality hitherto unknown to most architects. Anyone who has had the opportunity to meet some sorting garbage waste recycling shed is well aware of unsanitary and habitability conditions of these spaces. We believe that the experience and coexistence are the way to begin to understand this phenomenon. For us, there is a very direct relationship between body and architecture, between work and production space. Everything passes through architecture, because architecture is the final wrap of existence.

The phenomenon of selection is relatively new to the academic knowledge, and the sheds that were formed throughout Brazil during the last decade, whether they are built by municipalities or associations of the recyclers themselves, never were using planning of a more refined space. Its promoters were not concerned with working conditions, closed their eyes to the unhealthiness in the midst of such misery. We believe that architecture represents one of the oldest and most efficient productive machines. In it, it shows up all the virtues and shortcomings.

Roughly, the operation and layout of a recycling shed comprises a sequence of steps and movements of production: the city truck unloads the material (garbage) in the cages; after downloading of the material is removed gradually, bag by bag, to be opened and separated on the sorting tables; each separate material is thrown into the corresponding tambour or barrels; the person responsible of the tambours is in charge to collect the full tambours and unload it into the boxes (small cages where the selected material is joined: tetra pack boxes or green PET bottles); from there the material is removed and taken to the press. Once pressed, the bales are stored waiting for the buyer who will arrive with the truck.

Figure 3: Operating diagram of a Waste Recycling Shed. Drawing by Fernando Fuão.

Initially our first notes focused on the point of view of typological and architectural conditions. Most of the sorting units never had an initial design, except those built by the Municipality. Typologically we can define these spaces in three basic types of occupancy: sheds, use of the shallows of the expressway overpasses, and occupations of abandoned buildings.

The sheds are organized through this zoning of selecting by slides or spots, divided spaces that in many cases do not follow a more accurately logic of productivity. In many sheds there are errors in forwarding material starting from its incoming to its outgoing, ie there is no linearity of the production process, and the location of the recycling equipment is often wrong.

What initially has been observed is that these Waste Recycling Sheds built by the Municipality have been badly built, lacking a better knowledge of the desires and ways of working of the collectors, and ignoring basic issues of habitability. Within a few years, these sheds had shown poor structural and functional conditions, some of them did not have further then insecure roofing.

For the most part, they have a very questionable deployment in rough terrain with steep slopes, or departing from a doubtful initial concept that prioritizes the loading and unloading of materials brought in by truck, forming platforms at the expense of workers moving around inside the shed.

There are problems of all kinds, for example the illumination of the work place at all is wrong; the workers area of selecting (table

and bench) is turned towards the openings located in the front, causing glare and eyestrain.No additional artificial lighting is

provided, because often there is no money to replace the bulbs.

Next, at analytical and descriptive title, three recycling sheds in Porto Alegre are highlighted: Association Profetas da

Ecologia, Recycling Association Hospital São Pedro and Recyclers Association of the Vila dos Papeleiros (AREVIPA).

Figure 4: View from the main shed Profetas da Ecologia 1. Photo by Fernando Fuão.

Figura 5: Vista sob o viaduto com os pequenos volumes, galpão do Profetas da Ecologia. Foto Fernando Fuão.

The Association Profetas da Ecologia (1994) was a pioneer in the sheds in Porto Alegre, and is located in the shallows of the expressway overpasses near the city, known as the Viaduct of the Sertório, a chaotic residual area generated by the implementation of the tangle of overpasses and the trensurb railway network.

Currently living conditions and hygiene of the Profetas are still very poor. The Profetas da Ecologia, now an average of 30 members, consists of several small buildings constructed during that time. There is the large rectangular shed that was built during the founding of the Association, where is located the kitchen and canteen that open directly to the area of sorting and storage of waste; in the same building, on the mezzanine is located a classroom, an administrative room and two bathrooms.

Figura 6: Profetas da Ecologia. planta baixa do galpão principal. Desenhos de Camila Bernardelli e Camila Rocha.

In front of the set, underneath the two bridges that pass over the ground, there exist in addition to a new shed, that was built to remove garbage from the old shed, two other small buildings that were built through an agreement between the Profetas and the Municipality of Porto Alegre. One of the buildings that they call the "box" consists of ten cubicles, "garages" that served initially for collectors who would separate their garbage independently and not in the cooperative. The other is a small set of toilets and showers13.

Figure 7: Outside view of the Waste recycling shed of the Hospital São Pedro. Photo by Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

Figure 8: Interior of the Waste recycling shed of the Hospital São Pedro. Photo by Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

The waste recycling shed of the São Pedro Hospital Association is part of the Psychiatric Hospital building complex, located at Avenida Bento Gonçalves, Porto Alegre. This association differs from others because some hospital patients work in it, who use that work of recycling as therapy and treatment. Internally, there is a bay for storing paper, enclosed by metal bars and subdivided into smaller bays, it is at the center of the facility, like an island, and all activities are occurring around it. Between this and the cages for storage of garbage, which comes from the street, are arranged four tables of different sizes for separating.

9 Figueiredo, P., 2005. (Interview). Unidades de Triagem de resíduos sólidos, um estudo tipológico e normativo. UFRGS. Research report. CNPq. Porto Alegre.(not published).

10 Magera, M., 2003. Os empresários do Lixo, um paradoxo da modernidade. Campinas: Editora Átomo.

11 See for example the Call from CNPq (2007) about assistance to collectors who do not even looked at the item space-architecture, giving priority to conveyors, presses and other equipment.

12 Among the architectural surveyed sheds we highlight: Centro de Estudos Ambientais da Vila Pinto (CEA), Associação de recicladores da Vila dos Papeleiros.- AREVIPA, Associação Profetas da Ecologia 1, Associação Profetas da Ecologia 2, Associação Novo Cidadão, Associação de recicladores Hospital São Pedro, Galpão de reciclagem Rubem Berta, Galpão da Cavalhada, Galpão da Restinga, Galpão da Lomba do Pinheiro, Galpão da ilha dos Marinheiros, Galpão Passo Dornelles, Galpão da Santíssima na Vila Dique, Galpão Padre Cacique, ARLAS (Canoas), Galpão de reciclagem Passo Dornelles (Viamão), ACATA (Ijuí), ARPES, ARCELE, ASCOVI (Santa Maria), Associação Jardim Glória e Associação Esperança (Bento Gonçalves), Interbairros (Caxias do Sul).

13 About the Association Profetas da Ecologia see: Mello, B. C. E., 2009. Espaços de triagem de resíduos sólidos na cidade de Porto Alegre. O caso da Associação Profetas da Ecologia II e outras reflexões, Vitruvius, [online] Available at: <http://www.vitruvius.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp465.asp> [Accessed 15 August 2010]

To the right as you enter the kitchen is installed and a small office of the Association. The kitchen is represented as a place for socializing and exchanging ideas. Unfortunately, the door opens to the recycling area, as in the Profetas da Ecologia.

Figure 9: Internal view of the AREVIPA Shed. Porto Alegre. Photo by Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

Figure 10: View of the AREVIPA Roofing. Photo by Bruno Cesar E. de Mello.

The Association of Recyclers of the Vila dos Papeleiros (AREVIPA) get together recyclers who work collectively in the shed, receiving material from selective collection, as well as the independent carters (collectors), who are also residents of the Vila dos Papeleiros, but not members, all working under the same roof. Thus the set of Arevipa consists of two main buildings: an existing and a new shed. The existing shed is a rectangular building where the separating takes place. It belongs to it also a kitchen, a few small rooms and an adjacent space where are the presses to this large internal space.

The access of trucks bringing garbage from the selected collection is done by a large gate near the centre of the shed. To the left of that entry is the cage for the storage of material to be sorted. Three wooden tables are supported for sorting it, in the back of them a dozen canisters to collect the different materials.

The other volume, a large shed is a structure of prefabricated concrete beams and pillars without any closure or internal walls that protect the many carters from the weather. The dynamics in the shed is given as follows: the individual carters collect recyclable material from the city center and surrounding neighborhoods, take it to the shed where it is sorted into small improvised tables or the floor, and then sold to middlemen. The aspect of this work is one of chaos. They are many bags of garbage carts, bales, small tables for sorting and countless men and women working, coming and going at an intense pace. People with their carts enter and leave at all times. Together, they arrive with their young children who, by the inability of their parents to put them in an appropriate place, stick around, picking stuff to play in piles of garbage and plastic bags. All this is in an area where it is difficult for anyone coming from outside, to define where the workspace of a group begins or ends, what are the materials for the sorting of a particular worker. It is difficult to distinguish what is the order established by them for this large work space.

Suggestions for the waste recycling sheds

Finally, we believe that an analysis of the sheds and the criteria for drawing up a project for recycling sheds must go through several statements that should be taken into account as: the number of workers involved, working hours, how to share profits, volume of worked material, architectural conditions of the building if existing, adaptation to the terrain, topography, accessibility of pedestrians and trucks, loading and unloading system, trajectory and offset waste and their classifications in the shed, as well as evaluation of the equipment in relation to its location and characteristics of use (tables, benches, treadmills, scales, lifts). For example, work tables with four or six employees are more productive, then the solution of a large bench with members working individually. Besides these, it can be included: evaluation as to the sunshine, natural and artificial lighting, ventilation, humidity, odors, contact with toxic material, safety standards with respect to machinery, and so on. As conditions of the construction materials used in floors and walls, fire safety and especially health. It should be also considered in the same degree of importance or larger, yet the common spaces such as cafeterias, rooms for other sources of income generation as a workshop paper, sewing, cultural spaces, crafts, administrative offices, classrooms for literacy and computers, small movie theaters / cinema, such as the Center for Environmental Studies of the Vila Pinto, Porto Alegre14.

Figure 11: Example of sorting table with four associates. Drawings by Agata Muller and Lucas Weinmann.

Final considerations

In the world of waste recycling sheds, it was possible to see that there are a number of reasons and needs that go beyond architecture; before even reaching the spatial and typological question, there are many organizational obstacles, important issues of gender, group psychology, microphysics of power, - all these things end up reflecting in space.

A lack of concern by its workers is perceived, about the basic architectural conditions of the Sheds, a lack of concern with an order, an organization of space and a production. The most paradoxical is that we associate the disorder with who actually comes to order the material thrown out, unclassifiable. Actually, what the collectors do is to tame the disorder produced by the devouring of a consumer society, the society of waste. But in the minds of society, reaching out to the trash, to establish a symbiotic relationship between them is like appropriating evil, execrable, the eschatological, forming a perfect match. Anyway, it is concealing the guilt of those who produced it.

Today, the order is the consumption, the life putting in boxes, the packaging, the waste, the excess, and the packed.

The order and disorder, inclusion and exclusion, are like two sides of one coin: they are inseparable and often we find one inside the other, resubmitting their meanings to each other. There are two aspects to the real, which drag the very concept of meaning. The order is the meaning, the disorder without meaning. And there seems no wonder that our civilization may seem meaningless, to which all complain about the lack of direction.

At the sorting tables are separated, joined, sorted and pressed the meaning of the consumer society that were thrown away. They are then baled to later be crushed, crumbled, to become even meaningless material, until it is again reintroduced under a new form, a new meaning, a new package. That, ironically, is called recycling. The only problem is that these new materials are mostly packaging, meaningless things, which are devoid of any content soon after being consumed. They are representative objects of the throwaway society and this reordering of the whole recycling again becomes disorder through its own movement of the lack of meaning.

References

Balandier G., 1977. A Desordem, elogio ao Movimento. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil.

Bauman Z., 2004. O amor líquido, sobre a fragilidade dos laços humanos. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editores.

Figueiredo P., 2005. Depoimento em: Unidades de Triagem decíduos Sólidos, um estudo tipológico e normativo. Research Report. UFRGS. CNPq. Porto Alegre. pp. 87.

Figueiredo A. P., 2009. Traições tolerantes, histórias de um tempo em que tentávamos reciclar gentes e coisas. historias de pedras, [blog] 10 May, Available at: <http://historiasdepedras.blogspot.com/> [Accessed 15 August 2010].

Fuão F. and Rocha E., orgs., 2008. Galpões de reciclagem e a Universidade. Pelotas: Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL).

Fuão F. F., 2009. A vida embalada, Inscritos no Lixo, [blog] 16 March, Available at: <http://inscritosnolixo.blogspot.com> [Accessed 15 August 2010]

Fuão F. F., 2005. Sob Viadutos. [online] Fernando Fuão, Available at: <http://www.fernandofuao.arq.br/textos/sobviadutos.pdf> [Accessed 15 August 2010]

Laporte, D., 1988. Historia de la mierda. Valencia: Pre-textos.

Magera, M., 2003. Os empresários do Lixo, um paradoxo da modernidade. Campinas: Editora Átomo.

14 About the theme of recycling sheds in Rio Grande do Sul, see : Fuão, F. F. and Rocha, E., orgs., 2008. Galpões de reciclagem e a Universidade. Pelotas: Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL).

Mello, B. C. E., 2009. Espaços de triagem de resíduos sólidos na cidade de Porto Alegre. O caso da Associação Profetas da Ecologia II e outras reflexões. [online] Vitruvius, Available at: <http://www.vitruvius.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp465.asp> [Accessed 15 August 2010]

Moehlecke, V., 2005. Corpos da cidade: territórios e experimentações. [online] ARQTEXTO, 07. Available at: < http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Vilene%20Moehlecke.pdf > [Accessed 15 August 2010]

Teixeira, C. Agostini, F. and Cajado, L., 2005. Projeto baixios de viadutos da via expressa leste-oeste. [online] ARQTEXTO, 07. Available at: < http://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/PDFs_revista_7/7_Carlos%20Teixeira.pdf > [Accessed 15 August 2010]