Espaço público: risco, participação e o "novo público móvel"

Daniel Lobo é Arquiteto-Urbanista e Mestre em Estudos Urbanos, presentemente a pesquisar no Departamento de Geografia do University College London, Reino Unido, onde estuda a noção de risco no espaço público urbano.

Como citar esse texto: LOBO, D. A. Espaço público: risco, a participação e o “novo público móvel”. Traduzido do inglês por Vitor Loscilento Sanches. V!RUS, n. 5, 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus05/?sec=4&item=7&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 18 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

Esse artigo pretende analisar dois projetos de arte: a instalação "Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc., e o "Museu da Não Participação" de Karen Mirza e Brad Butler. São projetos particularmente interessantes, pois ambos são sujeitos narrativos e artefatos físicos ligados à vida quotidiana das pessoas no contexto urbano, que desafiam e ampliam a nossa relação com a cidade. Esses projetos são analisados segundo a sua contribuição para discussões atuais sobre o conceito de público, para o qual as noções de risco e participação envolvidas em cada um dos projetos de arte são fundamentais tendo em conta algumas das proposições teóricas mais pertinentes sobre vida pública e espaço público.

Considerando a influência que as novas tecnologias de transporte e comunicação têm tido na transformação do conceito de "novo público móvel” e as suas implicações sobre a forma como entendemos as dinâmicas das relações sociais, são justapostas duas metáforas utilizadas atualmente para significar essas dinâmicas dando sentido a abordagens contemporâneas de publicidade, e reconhecendo a importância das questões do risco e da participação retratadas pelos referidos projetos de arte como uma forma eficiente de levar avante a discussão.

Palavras-chave: espaço público, vida pública, público móvel, risco, participação.

Risco: "Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor"

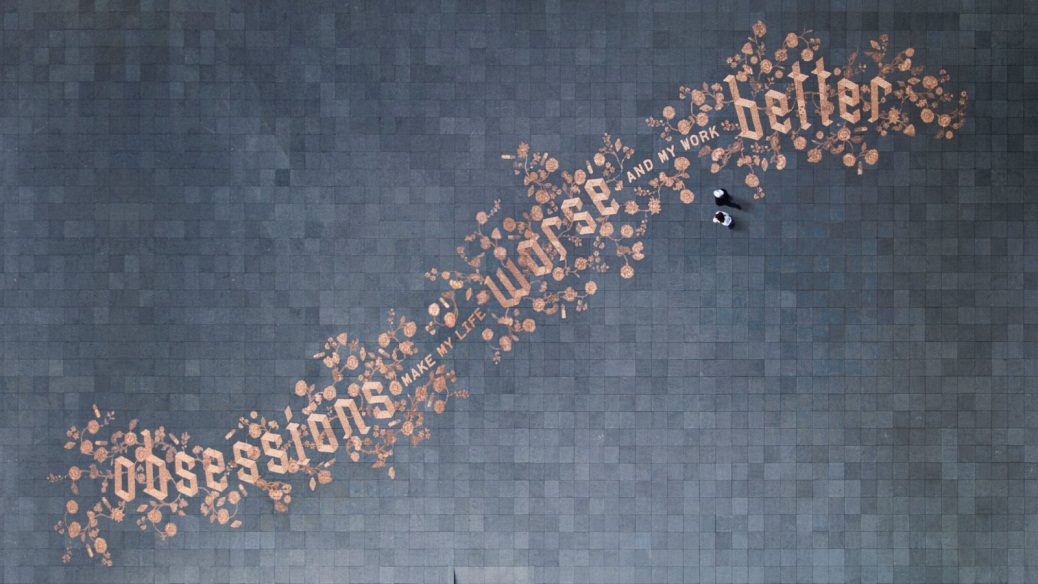

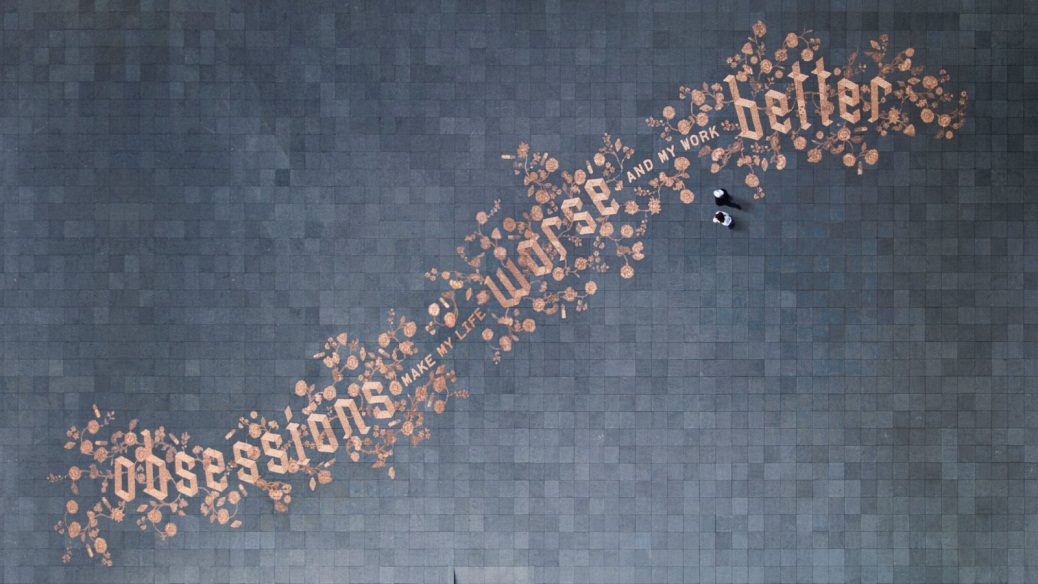

Figura 1. Instalação de arte “Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdã 2008. Imagem por Jens Rehr. Fonte: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Apresentada como parte do evento ExperimentaDesign Amsterdam 2008, a instalação de arte de Sagmeister criada num espaço público para o projeto Urban Play1, desempenhou um papel interessante e particularmente especial no que se refere à questão do risco na vida e espaço públicos.

A instalação, feita com 350.000 moedas de um centavo de Euro, cumpre bem o objetivo do projeto Urban Play. Moradores, visitantes e autoridades se tornaram parte fundamental da força por trás do objeto que afetou a regulação e ocupação do espaço público naquele contexto em particular onde a noção de risco se tornou o gatilho para a raison d'être da instalação.

Figura 2. Instalação de arte “Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdã 2008. Imagem por Jens Rehr. Fonte: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Eis como a história aconteceu. Na manhã do segundo dia do evento, a polícia de Amsterdã recebeu uma ligação de um morador de um prédio das redondezas para informar que a obra estava sendo roubada. Na verdade, as pessoas estavam embolsando algumas das moedas, o que já era esperado, mas, após serem vistas pelo referido morador, o destino da instalação estava prestes a mudar. A polícia de Amsterdã respondeu imediatamente, e em questão de minutos, para proteger a obra, os agentes da polícia varreram toda a instalação (BURNHAM, 2008).

Figura 3. Instalação de arte “Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdã 2008. Imagem por Anjens via Flickr. Fonte: http://www.flickr.com/photos/anjens.

Se esse era um resultado esperado pelo artista, não se sabe, mas uma coisa é certa: o cálculo do risco percebido esteve no cerne de sua obra. Parece claro que, ao colocar moedas de um centavo num espaço público sem qualquer policiamento ou outra fiscalização preventiva, Sagmeister permitiu que o risco de alguém embolsar as moedas de um centavo estivesse presente como parte da própria instalação (“A regra de coisas típicas” (GARDNER, 2008, p. 48)). O fato de as moedas de um centavo terem sido reunidas e apresentadas como uma peça de arte pública (notoriamente figurativa), sem que ninguém soubesse que embolsar as moedas fazia parte da instalação, fez o ato de embolsar uma moeda bastante mais arriscado do que embolsar uma moeda perdida em qualquer outro lugar, mesmo considerando o pequeno valor monetário envolvido. De fato, isso permitiu que aquele ato fosse tomado como é habitualmente, como um ato de destruição, vandalismo e roubo de um objeto público de arte, ou mesmo um ato responsável por causar desordem pública. No entanto, as pessoas embolsaram algumas moedas apesar das consequências que terão considerado (“A regra do exemplo” (GARDNER, 2008, p. 54)), onde fazê-lo ou não dependeu apenas do ponto de vista de cada um na sua interação com a obra e da sua percepção dos riscos envolvidos na ação.

O fato da instalação ter sido colocada nesse lugar em específico, ou seja, num lugar que permitia a existência do risco de vigilância de moradores que informariam a polícia se vissem alguém embolsando a obra, tornou possível o envolvimento de muitas pessoas com diferentes níveis de percepção de risco num espaço público. Mas, mais especificamente, permitiu que a cidade fosse usada como um lugar para arriscadas intervenções urbanas públicas, em que mesmo as autoridades da cidade puderam desempenhar um papel importante na contestação da sua noção de risco percebido e real, mesmo tendo acabado eventualmente por varrer uma instalação inteira com uma eficiência deveras curiosa (veja o vídeo em http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=av4mLRiCAxo&feature=player_embedded).

Figura 4. Instalação de arte “Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdã 2008. Imagem por Jens Rehr. Fonte: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Aqui o risco foi utilizado como uma forma de tornar mais claras as limitações que, preconceitos de medo, arte pública e crime têm. Nem os indivíduos que embolsaram consideraram bem as consequências de seus atos em relação aos outros que queriam manter a obra como era originalmente, nem os residentes agiram em prólogo da liberdade coletiva que se poderia ter na transformação física daquela obra, nem a polícia considerou a possibilidade das autoridades da cidade terem permitido o embolso da instalação. No entanto, a verdade é que a instalação não poderia ter sido mais bem sucedida em suas realizações.

Essa instalação pública de arte faz refletir sobre a epistemologia do risco utilizada na vida e nos espaços públicos atuais. Como é que o isolamento do envolvimento com esse tipo específico de risco num espaço público está ajudando a criar espaços públicos melhores, e usuários do espaço público e cidadãos em geral mais conscientes, quando ele nos impede de experimentar interações sociais mais ricas, que interessantes e inofensivas transformações físicas do espaço público podem conceber? Esse tipo de interação e transformação física representa um risco longe de se tornar benéfico para a sociedade como um todo? Esse é claramente um caso em que se pode notar o quão autolimitados nos temos tornado quando a preocupação em evitar o pior significa limitar a vontade de alcançar algo melhor da vida pública e dos espaços públicos (BECK, 1992, p. 49).

Figura 5. Instalação de arte “Obsessões Fazem a Minha Vida Pior e o Meu Trabalho Melhor” de Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdã 2008. Imagem por Anjens via Flickr. Fonte: http://www.flickr.com/photos/anjens.

Participação: "O Museu da não participação"

Figura 6. Projeto transcultural de investigação artística “Museu da Não Participação” dos artistas Karen Mirza e Brad Butler. ‘Intervenção Banner do Museu’, Karachi, 2008. Imagem por Karen Mirza and Brad Butler. Source: www.mirza-butler.net

Tudo começou durante os protestos do Movimento dos Advogados Paquistaneses, em Islamabad. Dois artistas - Karen Mirza e Brad Butler - estavam visitando a Galeria Nacional de Arte, quando de uma das salas de exposição, eles experienciaram uma sensação estranha ao testemunhar através da janela os protestos que, naquele momento, haviam se tornado violentos. Isso os impressionou fortemente, porque estando num contestado espaço da imagem - a galeria de arte - eles estavam olhando para um outro espaço contestado onde a imagem observada se apresentava altamente carregada de violência real.

Esse evento deu origem ao projeto transcultural de investigação artística "O Museu da Não Participação” (ver ARTANGEL, 2009). A ideia foi criar um museu como uma instituição pop-up que iria se apropriar da cidade como seu espaço e seu artefato, e teria seus cidadãos simultaneamente como usuários e criadores do museu. O projeto desenrola-se em muitas manifestações diferentes, tais como conversas, atividades e narrativas seguindo várias linhas de diálogo entre diferentes pessoas, lugares e contextos. A imagem da Figura 6 é uma pequena, mas não menos importante parte daquelas manifestações, onde vemos parte de um espaço público decrépito em Karachi, com um dos banners de texto que demarcava o museu na cidade, anunciando uma nova forma de a percorrer e observar, e na qual o grupo de crianças se torna parte integrante do museu, tanto como sujeitos narrativos quanto como usuários. A imagem mostra a importância do uso de texto na cidade como veículo que promove discussão, e que, por sua vez, informa o trabalho dos artistas e estimula a criação de novos paradigmas e preocupações.

Em suma, a mensagem, suportada pela imagem e pelo texto, abre o espaço para conversas que descobrem os padrões e as realidades da vida quotidiana com outras linguagens e vozes que não somente aquelas retratadas pela mídia ocidental. Isso gera redes de conhecimento e de pessoas que, por sua vez, formam elas mesmas seus espaços de resistência. A imagem aqui também é transformada num veículo que, no mundo globalizado de restrições de conflitos e divisões sociais e econômicas, intervém sobre a questão da espacialidade da participação e não participação pública a um nível global, quer seja em Karachi, Londres ou em outro lugar.

O conceito de museu que o projeto de arte concebeu está oscilando entre objeto e processo, e volta à noção grega de museu: uma extensão sem fronteiras entre a arte e a vida, um lugar para uma aprendizagem dinâmica e contínua. Ele questiona a desgastada palavra participação e, a partir dela, outros conceitos são questionados, tais como espaço de resistência, cidade, arquitetura e democracia, imagem e linguagem. A não participação aqui é utilizada como um conceito de provocação, um paradoxo que de forma divertida engaja com a discussão acerca do problema da participação e não participação pública, e nos faz pensar sobre nossas escolhas, necessidades e motivações quando participamos, seja em locais como Karachi ou em outro lugar. No entanto, ao expor a realidade crua de Karachi, em que as dinâmicas geopolíticas aumentam a necessidade de participar em movimentos de resistência violenta, o projeto desafia os significados de nossa própria condição nos contextos em que participamos.

Esse projeto questiona noções de publicidade, participação e democracia ao contrastar a noção ocidental de espaços museológicos e padrões de vida, com a realidade cruel do modo de vida vivido pela maioria da população de Karachi, que em contraste com os proprietários de automóveis com ar-condicionado, dependem de estratégias básicas de sobrevivência, tal é a brutalidade dessa cidade, vítima da confluência massiva de capital global.

O espaço público e o conceito de "novo público móvel"

O conceito de espaço público tem sido debatido desde a "queda do antigo regime e a formação de uma nova cultura urbana capitalista e secular" (SENNETT, 1977, p. 16). Esse conceito tem sido o centro de importantes debates dentro de várias disciplinas, tais como filosofia, geografia, artes visuais, estudos culturais e sociais, arquitetura e projeto urbano. Perguntas como “o que faz um espaço ser público?”, “quem é o público?” e “como a pesquisa deveria servir o interesse público, uma vez que esse interesse é quase impossível de encontrar?” (STAEHEIL; MITCHELL, 2007, p. 793) têm-se tornado o centro de perspectivas controversas de acadêmicos, ativistas e órgãos políticos.

A definição de espaço público, como é normalmente estabelecida pelas leis públicas do governo, pode ser abstratamente traduzida como: um espaço legal e temporalmente definido pela legislação de um determinado território, que se aplica a um grupo específico de indivíduos, em termos de sua utilização, propriedade e razão de ser, e que, apesar de poder ter ou não uma forma material identificável, é uma arena fundamental na definição e manutenção do individualismo e o coletivismo humano. Como qualquer outro termo definido por lei, ele contraria a anarquia e existe como uma ferramenta de mediação com a qual uma determinada sociedade pode funcionar, a fim de acordar individualmente sobre a definição de certos espaços para um melhor funcionamento do coletivo como um todo. Portanto, num esforço para proteger o equilíbrio e a ordem de um determinado grupo numa determinada sociedade, torna-se um conceito "bolha", que se faz eficaz na medida em que o equilíbrio dinâmico entre o que ele inclui e exclui impede a "bolha" de rebentar.

1 Urban Play é um projeto que visa estimular a intervenção de desenho urbano fora dos canais formais das instituições, comissões e planejamento urbano, e faz parte de um movimento de desenho urbano, muitas vezes conhecido como guerrilla design ou “Graffiti 3D". Essa onda de criatividade urbana tem, entre outras coisas, explorado e desafiado as regras de engajamento entre os cidadãos e autorizado expressões urbanas criativas. Enquanto alguns dogmas sociais têm rejeitado a maioria das intervenções urbanas informais como forma de vandalismo, ao centro deste movimento de desenho urbano DIY [“do it yourself” - faça você mesmo] existem inovadores e sofisticadas intervenções urbanas que desafiam e ampliam profundamente nossa relação com a cidade.

Sejam quais forem as definições jurídicas do termo, sendo mais ou menos inclusivas ou flexíveis, e independentemente de adotar uma abordagem pró-individualista ou do pró-coletivista, o espaço público está diretamente relacionado com a expressão da nossa condição humana mais inerente: a relação entre o eu e o outro. A definição por lei desta relação é assim altamente política, por isso o termo espaço público e os próprios espaços públicos tornam-se mais ricos e responsavelmente humanizados na medida em que esta relação tende a existir em nome das relações humanas, expressões e influências políticas livres, igualitárias e cuidadosas, quer se pratiquem dentro ou fora da "bolha".

Atualmente,

a literatura sobre o tema sugere que o espaço público no mundo

ocidental não representa mais o espaço do público, mas apenas de

uma parte estritamente prescrita dele (MITCHELL, 1995, p. 120). Para

muitos críticos isso é devido a princípios modernos de uma

natureza de espetáculo altamente mercantilizada, concebidos para o

lucro, a segurança e para manter a estabilidade social e política,

o que tem implicações determinantes no valor de troca das relações

humanas.

Isso tem criado espaços que não permitem a direta interação

social em público, livre de mediação, o

que diminui a interação das pessoas com o público real (ou seja, o

público que abrange todos, incluindo os sem-abrigo e os ativistas

políticos), cuja legitimidade como membros do público está-se

tornando injustamente duvidosa (MITCHELL, 1995, p. 120).

De acordo com Mimi Sheller, os públicos móveis têm agora novas formas de mobilização e espacialização que sustentam a participação do público e, portanto, afetam a vida pública em geral (SHELLER, 2003). Embora ainda haja pouca pesquisa sobre os verdadeiros efeitos das novas formas de públicos, o estudo das suas próprias dinâmicas, confusas e "gelificantes", permitirá uma melhor compreensão da natureza das novas interações sociais móveis.

A introdução das novas tecnologias de comunicação no quotidiano das sociedades contemporâneas em todo o mundo tem permitido um aumento da participação social, política e cultural dos povos e regiões mais marginalizados. No entanto, elas também podem ser uma ameaça à dimensão pública e à interação social, levando ao declínio da participação democrática, da coesão cívica e, em suma, do capital social.

No final de 2009, de acordo com a União Internacional de Telecomunicações, havia aproximadamente 4,6 biliões de assinaturas de celulares no mundo, com a tendência de crescimento em número e em desenvolvimento tecnológico, uma vez que “a barreira entre celulares e computadores está cada vez menor" (NAGATA, 2009). De fato, os telefones celulares têm tido amplas implicações culturais e sociais, na medida em que mudam a natureza da comunicação e afetam identidades e relacionamentos. Segundo a Dra. Sadie Plant (2006, p. 23), "ele afeta o desenvolvimento das estruturas sociais e das atividades econômicas, e tem influência considerável sobre as percepções que seus usuários têm de si mesmos e do seu mundo". Alguns fatos interessantes tornaram-se conhecidos a partir de um estudo sobre celulares dirigido pela Dra. Plant:

Para algumas pessoas, os contatos sem esforços e as mensagens breves descomprometidas tornadas possíveis graças ao celular são formas de evitar os tipos de interações mais imediatos e próximos. Um serviço japonês permite que os usuários cortejem “namoradas virtuais” pelo celular e muitos adolescentes têm dezenas, às vezes centenas, de meru tomo, “amigos de e-mail”, que podem nunca encontrar pessoalmente e se conhecem somente através do keitai. Muitas dessas amizades envolvem personalidades construídas e por vezes redes complexas de múltiplas personas e relações ambíguas. Para alguns adolescentes, tais amigos virtuais podem atuar como substitutos dos amigos reais, assim como os videogames podem substituir suas vidas reais. Um estudante japonês manifestou preocupações sobre os usuários mais jovens dos keitai estarem se tornando cada vez menos capazes de comunicações sociais diretas. Eles dependem da tecnologia para conversar. Eles frequentemente são capazes de coletar informação, mas não de utilizá-la, e eu sou frequentemente surpreendido por suas respostas emocionais estranhas. (PLANT, 2006, p. 59).

Vários colaboradores alegaram que o celular deixa as pessoas incapazes de apreciar os desafios e as oportunidades que o "tempo morto" pode proporcionar. Em Chicago, um grupo de jovens intelectuais expressou a preocupação de que tal conectividade pode prejudicar até mesmo a autoconfiança das pessoas, tornando-as incapazes de agirem sozinhas, e deixando-as dependentes do celular como fonte de assistência e aconselhamento. Raramente isolada por falta de comunicação, a pessoa com um celular está menos exposta aos caprichos do acaso, e é pouco provável que seja lançada aos seus próprios recursos, ou encontre aventura, surpresa ou o mais feliz dos acidentes. (PLANT, 2006, p. 61).

Com a nova dinâmica trazida pelas novas tecnologias de comunicação e transporte, uma nova ordem social e espacial, reconhecida por Castells como "espaço de fluxos" ou por alguns geógrafos urbanos como “a ‘liquefação’ da estrutura urbana”, a vida pública tem sido afetada, e para a qual as noções de risco e participação desempenham um papel importante.

Sheller coloca duas perguntas fundamentais sobre esta questão: "Que mecanismos animam a sociabilidade líquida? Que agências estão trabalhando para gelificar ou evaporar as ligações sociais?" (SHELLER, 2003, p.47). Muitos pessimistas veem esta "sociabilidade líquida" como uma ameaça ao próprio capital social, o que poderá ser exemplificado por analogia aos casos de risco e participação explorados acima. Em ambos os casos, o isolamento do engajamento com a vida e os espaços públicos produziu atitudes de descuido em relação à vida pública e aos espaços em si, uma vez que impediu em grande medida de saber o efeito de tal engajamento sobre os espaços e sobre os outros.

No entanto, a resposta à primeira questão pode-nos mostrar algo mais. Os mecanismos que animaram a "sociabilidade líquida" eram de fato muito tangíveis e físicos, e seu impacto teve efeitos maiores, discutivelmente porque eles atuaram na dimensão física do espaço público. A entrada deste acontecimento bastante tangível e público na chamada "sociabilidade líquida" só aconteceu depois, ampliado pelas novas tecnologias de comunicação: as câmeras que registraram as cenas, a internet utilizada para exibir /promover e discutir os efeitos em cadeia da instalação de Sagmeister e do projeto de Mirza e Butler etc..

Em resposta à segunda questão, o fato de ter havido um crescente desprendimento com experiências comunicacionais públicas físicas/presenciais, pode talvez ser a explicação para, no caso da instalação de Sagmeister, a pessoa que relatou o roubo, o ter feito antes sequer de iniciar uma conversa com a pessoa que estava embolsando as moedas, ou mesmo antes de considerar que embolsar as moedas não era de fato um roubo.

Podemos especular sobre as muitas razões por tal ter acontecido, e especular também sobre as muitas razões pelas quais o protesto dos advogados acabou dando origem ao projeto de arte “Museu da Não Participação”, mas o fato é que a instalação e o museu "evaporaram" fisicamente, mas não completamente. Bem que o oposto. O desaparecimento do artefato físico gerou um contra efeito amplificado desproporcionalmente através das novas tecnologias de comunicação, o que permitiu a “gelificação" de muito mais interações sociais do que seria possível se, por outro lado, o artefato existisse unicamente em sua forma física.

Parece não haver uma resposta direta quanto ao fato de as "sociabilidades líquidas” e os "espaços de fluxos" criados pelo novo público móvel serem de fato mais benéficos ou mais prejudiciais para a vida pública e espaços públicos. No entanto, é evidente que uma nova espécie de rede para além da perspectiva da teoria da rede é agora uma realidade dada. Aspectos intrínsecos e instrumentais da dimensão social trazidos pelo novo público móvel devem ser agora entendidos à luz de suas próprias complexidades. Embora a complexidade da questão possa muitas vezes tornar menos óbvio o caminho a seguir, a complexidade não é a razão para os atuais espaços parasitários de ação pública (ver BARNETT, 2008). Como argumenta Barnett, "na teoria democrática, a dimensão humana está instrumentalmente relacionada com a manutenção da legitimidade de vincular a tomada de decisões coletivas". No entanto, poderosas forças de privatização, de exclusão social e as desigualdades que delas advêm estão comprometendo o caminho para uma vida mais democrática e participativa, onde é instrumental identificar as possibilidades do novo público móvel para uma participação consenso-conflitual agonística2, para a qual a compreensão e o uso da compreensão de conceitos como o risco e a participação desempenham um papel fundamental.

Referências

ARTANGEL. Karen Mirza and Brad Butler: the museum of non participation. Disponível em: < http://www.artangel.org.uk/projects/2008/the_museum_of_non_participation>. Acesso em: 2 fev. 2011.

BARNETT, C. Convening publics: the parasitical spaces of public action. In: COX, K.; R.; LOW, M.; ROBINSON, J. (Eds.). The sage handbook of political geography. UK: Sage Publications, 2008. p. 403-417.

BECK, U. Risk society. Londres: Sage, 1992.

BURNHAM, S. Stefen Sagmeister installation removed by Amsterdam Police. Amsterdã: Scott Burnham, 2008. Disponível em: < http://scottburnham.com/2008/09/stefan-sagmeister-installation-removed-by-amsterdam-police/>. Acesso em: 24 jan. 2011.

GARDNER, G. Risk: the science and politics of fear. Londres: Virgin, 2008.

MITCHELL, D. The end of public space?: people's park, definitions of the public, and democracy. In: _______. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. [s.l.]. Routledge, março 1995. v.85, n.1. p. 108-133.

MOUFFE, C. On the political. Abingdon – Nova York: Routledge, 2005.

NAGATA,K. Cell phone culture here unlike any other. The Japan Times [s.l.], 2 set. 2009. Disponível em: < http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20090902i1.html>. Acesso em: 9 jan. 2010.

PLANT, S. On the mobile: the effects of mobile telephones on social and individual life. Londres: University of East London, 2006.

SENNETT, R. The fall of public man. Londres: Faber and Faber, 1977.

SHELLER, M. Mobile publics: beyond the network perspective. Environment and planning D: society and space. [s.l.], 2003. v. 22, n.1. p. 39-52.

STAEHEIL, L. A.; MITCHELL, D. Locating the public in research and practice. Progress in human geography. [s.l.], 2007. v. 31, n. 6. p. 792-811.

2 O conceito de "participação agonística" é baseado nos estudos desenvolvidos pelo cientista político Chantal Mouffe acerca do modelo de "democracia agonística" (MOUFFE, 2005), que em termos gerais, defende a importância da criação de um espaço simbólico dos esforços construtivos entre as diferentes interpretações de princípios compartilhados.

Public space: risk, participation and the “new mobile public”

Daniel Lobo is an architect-urbanist and a Master in Urban Studies, currently researching at the Geography Department at the University College of London, United Kingdom, where he studies the notion of risk within the public urban space.

How to quote this text: Lobo, D. A. Public space: risk, participation and the “new mobile public”, V!RUS, [online] June, 5. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus05/?sec=4&item=7&lang=en>. [Accessed: 18 July 2025].

Abstract

The following text intends to review two art projects, the installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc., and “The Museum of Non Participation” by Karen Mirza and Brad Butler.

These projects are particularly interesting as both are narrative subjects and physical artefacts connected with people’s everyday life in the urban context that challenge and expand our relationship with the city. They are analysed regarding their contribution to the current discussions on the concept of public, for which the issues of risk and participation at play on each of the art projects are quintessential concerning some of the most acute propositions of theorists on public life and public space.

Considering the influence that the new technologies of transportation and communication have had on the transformation of the concept of “new mobile public” and its implications on the way we understand social relations dynamics, two metaphors currently used to signify those dynamics are juxtaposed to make sense of contemporary approaches to publicness, and to acknowledge the importance of the issues of risk and participation, portrayed by the referred art projects, as a proficient way to take forward the discussion.

Keywords: Public space, public life, mobile public, risk, participation.

Risk: “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better”

Figure 1. Art installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdam 2008. Photo by Jens Rehr. Source: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Presented as part of the event ExperimentaDesign Amsterdam 2008, Sagmeister’s art installation created in a public space for the project Urban Play1, played an interesting and peculiar role regarding the issue of risk affecting public life and space.

The installation design done with 350,000 euro cent coins fulfils well the purpose of the project Urban Play. Inhabitants, visitors and the authorities became a fundamental part of the force behind the object that affected the regulation and inhabitation of public space on that particular context where the notion of risk became the trigger for the raison d’être of the installation.

Figure 2. Art installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdam 2008. Photo by Jens Rehr. Source: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Here is how the story went. In the morning of the second day of the event, a resident of an overlooking building reported to Amsterdam police that the artwork was being stolen. As a matter of fact, people were pocketing a few of the coins, which was also expected, but after being seen by the referred resident the destiny of the installation was about to change. Amsterdam police responded immediately, and in a matter of minutes as to secure the artwork, police officers swept up the entire installation (Burnham, 2008).

Figure 3. Art installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdam 2008. Photo by Anjens via Flickr. Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/anjens.

Whether this was an expected result for the artist it really isn’t known, but one thing is certain, the calculation of perceived risk was at the centre of his work. It seems clear that by placing one euro cent coins in a public space without any police or other preventive surveillance, Sagmeister allowed the risk of someone pocketing the cent coins to be present as a part of the installation itself (‘Rule of typical things’ (Gardner, 2008, p.48)). The fact that the cent coins were assembled and presented as a public piece of art (notably figurative), and not letting anyone know that to pocket the coins was part of the installation, made the act of pocketing a cent coin to be quite a more risky act comparing with pocketing a lost cent coin somewhere else, even considering such little monetary value. In fact it allowed that act to be taken as it usually is, as an act of destruction, vandalism and robbery of a public object of art, or even an act liable of causing public disorder. However, people still did pocketed some coins despite the consequences they might have considered (‘The example rule’ (Gardner, 2008, p.54)), where to do it or not depended on one’s point of view when in interaction with it and the perceived notion of the actual risks involved in the action.

The fact that the installation was placed in that particular place, i.e. a place that allowed the existence of the risk of surveillance by inhabitants that would report to the police if they saw someone pocketing from it, made possible the engagement of many people that played out in many different levels the perception of risk in a public space. But more specifically it allowed the city to be used as a place for risky public urban interventions where even city authorities could play an important role in challenging its notion of perceived and actual risk, even if they ended up eventually sweeping up an entire installation with a rather odd efficiency (see video in http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=av4mLRiCAxo&feature=player_embedded).

Figure 4. Art installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdam 2008. Photo by Jens Rehr. Source: http://www.sagmeister.com.

Risk here was used as a way to make clearer the limitations that, preconceptions of fear, public art and of crime have. Nor the individuals that pocketed considered well the consequences of their acts in relation to others that wanted to maintain the piece as it was originally, neither the resident acted in regard of the collective freedom that one could have in the physical transformation of that piece, nor the police considered the fact that the city authorities might have allowed the pocketing of the installation. However, the truth is that the installation couldn’t have been more successful in its achievements.

This public art installation does make one wonder about the epistemology of risk played out in current public life and spaces. How is that the isolation from the engagement with this particular type of risk in a public space is helping to create better public spaces, conscientious public space users and citizens in general, when it prevents us from experiencing richer social interactions that interesting and harmless public space physical transformations can conceive? Does this kind of interaction and physical transformation represent a risk too far from becoming beneficial for society as a whole? This is clearly a case where one can note how self-limited one have become when, to be concerned with preventing the worst, means limiting the will to attain something better out of public life and public spaces (Beck, 1992, p.49).

Figure 5. Art installation “Obsessions Make My Life Worse and My Work Better” by Sagmeister Inc. (Richard The, Joe Shouldice, Stefan Sagmeister) during ExperimentaDesign, Amsterdam 2008. Photo by Anjens via Flickr. Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/anjens.

Participation: “The Museum of Non Participation”

Figure 6. Cross-cultural artistic investigation project “Museum of Non Participation” by artists Karen Mirza and Brad Butler. ‘Museum Banner Intervention’, Karachi, 2008. Photo by Karen Mirza and Brad Butler. Source: www.mirza-butler.net

It all began during the protests of the Pakistani Lawyers Movement in Islamabad. Two artists - Karen Mirza and Brad Butler - were visiting the National Art Gallery, and from one of the exhibition rooms they experienced an odd sensation by witnessing through the window the protests, which at that moment had turned violent. It strongly impressed them, because standing within a contested image space - the art gallery - they were looking out to another much localized contested space with a highly charged sight image of real violence.

This event gave origin to Mirza and Butler’s cross-cultural artistic investigation project “The Museum of Non Participation” (see Artangel, 2009). The idea was to create a museum as a pop-up institution that would appropriate the city as its space and artefact, and have its citizens as both museum users and makers. The project plays out in many different manifestations such as conversations, activities and narratives following strands of dialogue to different people, places and contexts. The image on Figure 6 is a small, but nevertheless important part of that manifestations, where we see a part of a decrepit public space in Karachi with one of the text banners that demarcated the museum in the city, announcing a new way of moving through and looking at the city, in which the group of children became part as both museum subjects and museum users. The image shows the importance of the use of text in the city to provoke discussion, which in turn informs the artists work and lead to further queries and concerns.

In sum, both image and text opens up the space for conversations that discover the patterns and realities of everyday life with other languages and voices than just the ones portrayed by western media. This generates networks of knowledge and people that in turn form themselves their spaces of resistance. Image here is also turned into a vehicle that within the globalized world of conflict restrictions and social and economic divisions engages with the question of the spatiality of public participation and non-participation in a global level, whether in Karachi, London or elsewhere.

The concept of museum that the art project conceived is oscillating between object and process, and goes back to the Greek notion of museum as a borderless extension between art and life, a place for a dynamic and continuous learning. It questions the overused word participation, and from it other concepts are questioned such as, space of resistance, city, architecture and democracy, image and language. Non participation here is used as a concept of provocation, a paradox that playfully engages the discussion about the problem of public participation and non participation, and makes us think about our choices, needs and motivations when we participate, whether in places such as Karachi or elsewhere. However, by exposing the raw reality of Karachi, where geopolitical dynamics increase the need to participate in movements of violent resistance, it challenges the meanings of our own condition in the contexts where we participate.

This project questions notions of publicness, participation and democracy by contrasting the western notion of museum spaces and living standards, and the cruel reality of the way of life lived by most of Karachi’s population, that in contrast with the air conditioned car owners, have to depend on basic survival strategies in order to survive, such is the brutality of this city, victim of massive confluence of global capital.

Public space and the concept of “new mobile public”

Public space is a term that has been in critical scrutiny since the “fall of the ancient regime and the formation of a new capitalist, secular, urban culture” (Sennett, 1977, p.16). It has been the centre of important debates within various disciplines such as philosophy, geography, visual art, cultural and social studies, architecture and urban design. Questions such as, “what makes a space public?”, “who is the public?” and “how research should serve the public interest since that interest is nearly impossible to find?” (Staeheil and Mitchell, 2007, p.793), have become the centres of controversial perspectives by scholars, activists and formal political bodies.

Its definition as it is usually settled by government’s public laws, might be abstractly translated as: a space legally defined within a defined time by the public law of a certain territory, that applies to a specific group of individuals, in terms of its use, ownership and reason of being, and besides having or not an identifiable material form, it is a fundamental arena for defining and sustaining human individualism and collectivism. As any other term defined by law, it counteracts anarchy and exists as a mediation tool with which a certain society can operate with, in order to compromise individually on the definition of certain spaces for a better functioning of the collective as a whole. Therefore as in an effort to protect the balance and order of a certain group in a certain society it becomes a “bubble” concept that becomes effective as far as the dynamic balance between what it includes and excludes doesn’t cause the “bubble” to burst.

1 Urban Play is a project that aims to stimulate urban design interventions outside the formal channels of institutions, commissions and urban planning, and is part of an urban design movement often referred as guerrilla design or “3D Graffiti”. This surge of urban creativity has among other things explored and challenged the rules of engagement between citizens and authorized urban creative expressions. While some social dogmas have dismissed most of the informal urban interventions as forms of vandalism, at the centre of this DIY urban design movement there are innovative and sophisticated urban interventions that deeply challenge and expand our relationship with the city.

Whatever the legal definitions of the term, being them more or less inclusive or more or less flexible, and independently from taking a pro-individualism or pro-collectivism approach, the term public space is directly concerned with the expression of our most inherent human condition: the relation between the self and the other. The definition by law of this relation is highly political, therefore the term and public spaces themselves become more richly and responsibly humanized as far as this relation tends to be played in behalf of the free, equal and caring human relations, expressions and political influences, whether played inside or outside the “bubble”.

Currently, literature on the subject suggests that public space in the western world doesn’t represent anymore the space of the public but just of a narrowly prescribed part of it (Mitchell, 1995, p.120). For many critics this is, due to modern principles, of a highly commodified spectacle nature, devised for profit, safety and to maintain social and political stability, which have determinant implications on the exchange value of human relations. This has created spaces that don’t allow for direct, mediation-free, social interaction in public, which decreases people interaction with the real public (i.e. the public that encompasses everyone including homeless and political activists) whose legitimacy as members of the public is becoming unfairly doubtful (Mitchell, 1995, p.120).

According to Mimi Sheller, mobile publics have now new ways of mobilization and spatialization that underpin public participation and thus affect public life in general (Sheller, 2003). Although there is still little research on the actual effects of the new forms of publics, the study of their particular messier and “gelling” dynamics will enable a better understanding of the nature of the new mobile social interactions.

The introduction of new communication technologies in the everyday life of contemporary societies all over the world, have allowed for an increasing social, political and cultural participation of the most marginalized people and regions. Nevertheless they also might be a threat to publicness and social interaction, leading to the decline of democratic participation, civic cohesion and in sum of social capital.

At the end of 2009, according to the International Telecommunication Union there were approximately 4.6 billion mobile cellular subscriptions worldwide, with the tendency to keep rising in number and in technological development, as “the barrier between cell phones and computers is getting lower” (Nagata, 2009). In fact mobile phones have had extensive cultural and social implications as it changes the nature of communication and affects identities and relationships. According to Dr. Sadie Plant (2006, p.23), “it affects the development of social structures and economic activities, and has considerable bearing on its users perceptions of themselves and their world”. Some interesting facts came out from a study on mobiles directed by Dr. Plant:

For some people, the effortless contacts and fleeting noncommittal messages made possible by the mobile are ways of avoiding more immediate and forthcoming kinds of interaction. One Japanese service allows users to court ‘virtual girlfriends’ by mobile phone and many teenagers have dozens, sometimes hundreds of meru tomo, ‘email friends’, who may never meet and only ever know each other through the keitai. Many of these friendships involve constructed personalities and sometimes complex webs of multiple personas and duplicitous affairs. For some teenagers, such virtual friends can act as substitutes for actual friends, just as video games can replace their real lives. One Japanese student expressed concerns that younger keitai users are becoming less capable of direct, social communications. They rely on technology to converse. They are often intelligent with collecting information but not with utilising it, and I am often surprised by their awkward emotional responses. (Plant, 2006, p.59).

Several contributors argued that the mobile leaves people unable to appreciate the challenges and opportunities ‘dead time’ can present. In Chicago, a group of young intellectuals expressed the concern that such connectivity might even undermine people’s self-reliance, making them unable to operate alone, and leaving them dependent on the mobile as a source of assistance and advice. Rarely stranded incommunicado, the person with a mobile is less exposed to the vagaries of chance, unlikely to be thrown onto resources of their own, or to encounter adventure, surprise, or the happiest of accidents. (Plant, 2006, p.61).

With the new dynamics brought by new technologies of transportation and communication a new social and spatial order, acknowledged by Castells as the “space of flows”, or by some urban geographers as “the ‘liquefaction’ of the urban structure”, public life have become inherently affected for which the notion of risk and participation play a major role.

Sheller asks two fundamental questions on this regard: “What mechanisms animate liquid sociality? What agencies are at work to make social connections gel or evaporate?” (Sheller, 2003, p.47). Many pessimists see this “liquid sociality” as a threat to social capital itself, which can be exemplified why this might be true, by analogy to the cases of risk and participation explored above. In both cases, the isolation from the engagement with public life and spaces did produce attitudes of carelessness towards public life and spaces, as it prevented from knowing the effect of such engagement on the space and on others. Nevertheless, the answer to the first question can show us something else. The mechanisms that animated the “liquid sociality” were in fact very tangible and physical, and their impact had bigger effects, arguably because they operated within the physical dimension of public space. The entry of this very tangible and public happening into the called “liquid sociality” happened just afterwards, amplified by the new technologies of communication: the cameras that registered the scenes, the internet used to exhibit/promote and discuss the trickle down effects of Sagmeister’s installation and Mirza and Butler’s art project, etc.

In answer to the second question, the fact that there has been an increasing disengagement with public physical/live communicational experiences can perhaps be said to be the cause why, in the case of Sagmeister’s installation, the person who reported the robbery did report the robbery even before engaging into conversation with the person who was pocketing the coins, or even considering that pocketing the coins wasn’t in fact a robbery.

We can speculate about the many reasons why she did it, and we also can speculate about the many reasons why the lawyers protest trickled down into the Museum of Non-participation art project, but the fact is that the installation and the museum “evaporated” physically, but not entirely. Quite the opposite. The disappearance of the physical artefact, generated a disproportional amplified counter effect through the new technologies of communication, which allowed the “gelification” of many more social interactions than it would have otherwise allowed if the artefact existed solely in its physical form.

There seems to be no straight answers to whether the “liquid socialities” and “spaces of flows” created by the new mobile public are indeed more beneficial or more detrimental to public life and public spaces. However, it is clear that a new sort of network beyond the network theory perspective is now a given reality. Intrinsic and instrumental aspects of publicness brought by the new mobile public must be now understood in the light of its own complexities. Although the complexity of the issue can often blur the way forward, complexity isn’t the reason to current parasitical spaces of public action (see Barnett, 2008). As Barnett argues, “in democratic theory, publicness is instrumentally related to maintaining the legitimacy of binding collective decision-making”, however, powerful forces of privatization, social exclusion, and inequalities are jeopardizing the way to a more democratic participative living, where it becomes important to identify the possibilities of the new mobile public as instrumental for an agonistic conflictual-consensus participation2 for which the understanding and the use of the understanding of the concepts of risk and participation play a fundamental role.

References

Artangel, 2009. Karen Mirza and Brad Butler: the museum of non participation. Available at: <http://www.artangel.org.uk/projects/2008/the_museum_of_non_participation> [Accessed 2 February 2011].

Barnett, C., 2008. Convening publics: the parasitical spaces of public action. In: K. R. Cox, M. Low and J. Robinson eds., ed. 2008. The sage handbook of political geography. UK: Sage Publications Ltd. pp.403-417.

Beck, U., 1992. Risk society. London: Sage.

Burnham, S., 2008. Stefen Sagmeister installation removed by Amsterdam Police. Amsterdam: Scott Burnham. Available at: < http://scottburnham.com/2008/09/stefan-sagmeister-installation-removed-by-amsterdam-police/> [Accessed 24 January 2011].

Gardner, G., 2008. Risk: the science and politics of fear. London: Virgin.

Mitchell, D., 1995. The end of public space?: people's park, definitions of the public, and democracy. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 85 (1), pp.108-133.

Mouffe, C., 2005. On the political. Abingdon – New York: Routledge.

Nagata, K., 2009. Cell phone culture here unlike any other, The Japan Times. Available at: <http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20090902i1.html> [Accessed 9 January 2010].

Plant, S., 2006. On the mobile: the effects of mobile telephones on social and individual life. London: University of East London.

Sennett, R., 1977. The fall of public man. London: Faber and Faber.

Sheller, M., 2003. Mobile publics: beyond the network perspective. Environment and planning D: society and space. 22 (1), pp.39-52.

Staeheli, L. A. and Mitchell, D., 2007. Locating the public in research and practice, Progress in human geography, 2007. 31 (6), pp.792-811.

2 The concept of “agonistic participation” is based on the studies developed by the political scientist Chantal Mouffe about the model of “agonistic democracy” (see Mouffe, 2005), which in general terms advocates the importance of the creation of a symbolic space of constructive struggle between different interpretations of shared principles.