A fala oculta do espaço doméstico: padrões familiares incorporados no layout de apartamentos na Lisboa contemporânea

Sandra Marques Pereira é socióloga e Doutora em Sociologia, pesquisadora do Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconômica e o Território (DINÂMIA-CET), do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE), Portugal, pesquisa cenários domésticos e modos de habitar, trajetórias residenciais e a metropolização de Lisboa.

Como citar esse texto: PEREIRA, S.M. A fala oculta do espaço doméstico: padrões familiares incorporados no layout de apartamentos na Lisboa contemporânea. Traduzido do inglês por Felipe Anitelli. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 5, jun. 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus05/?sec=4&item=9&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

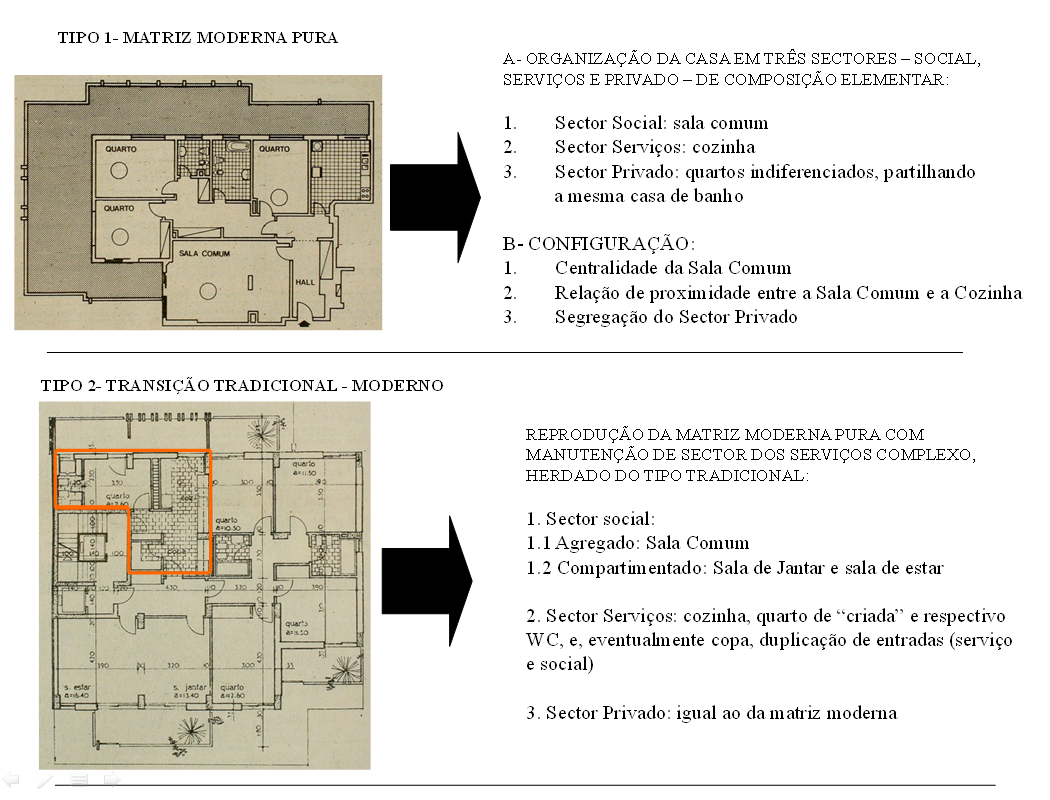

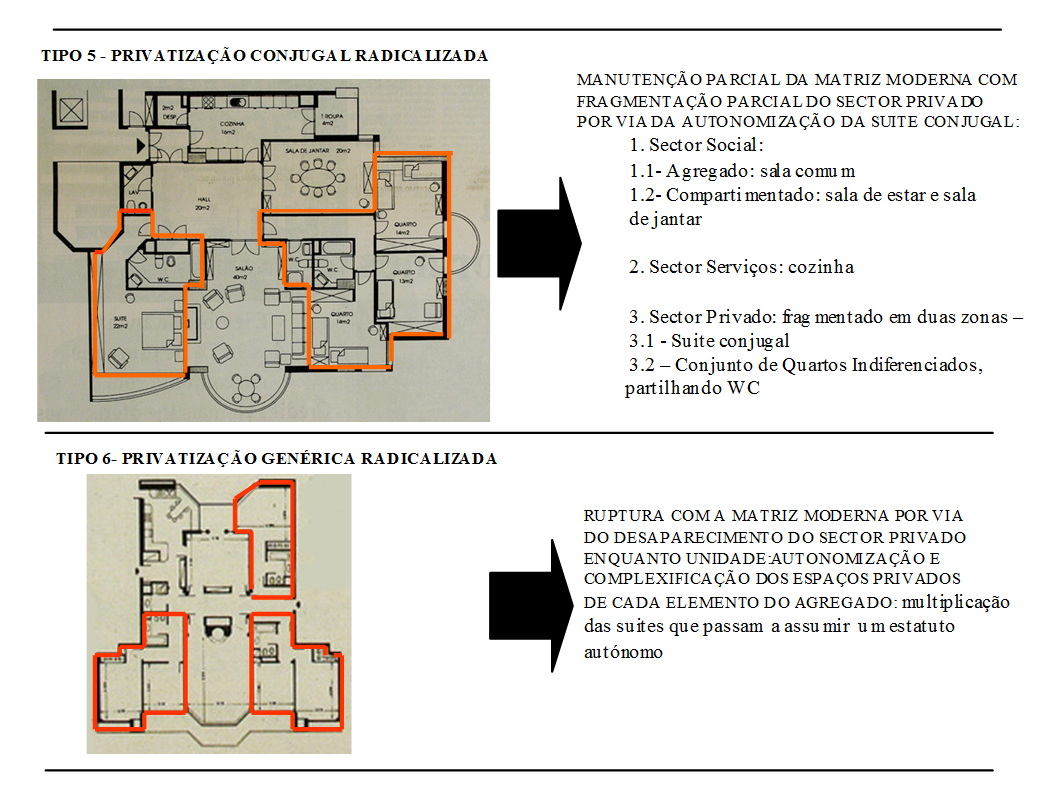

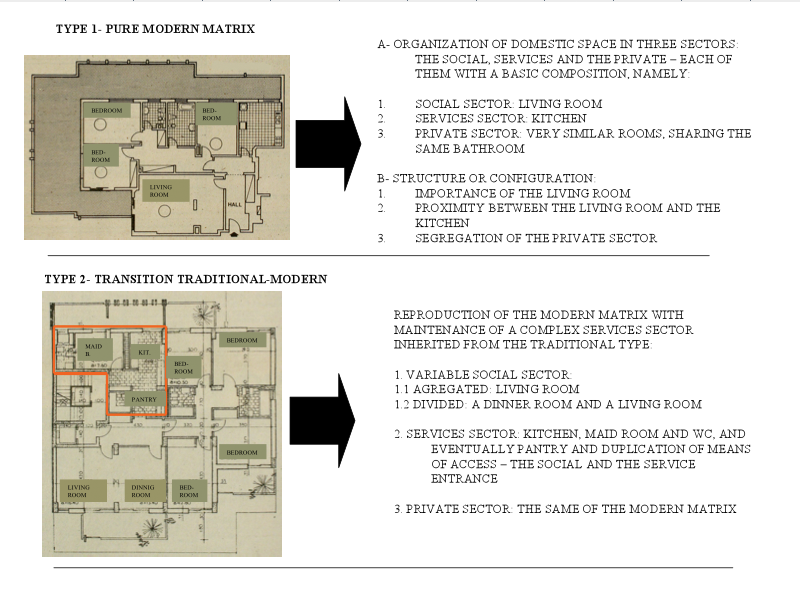

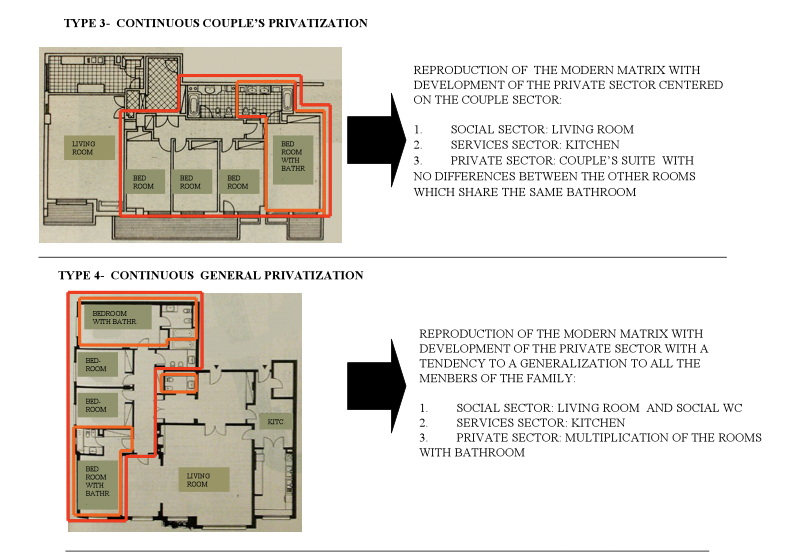

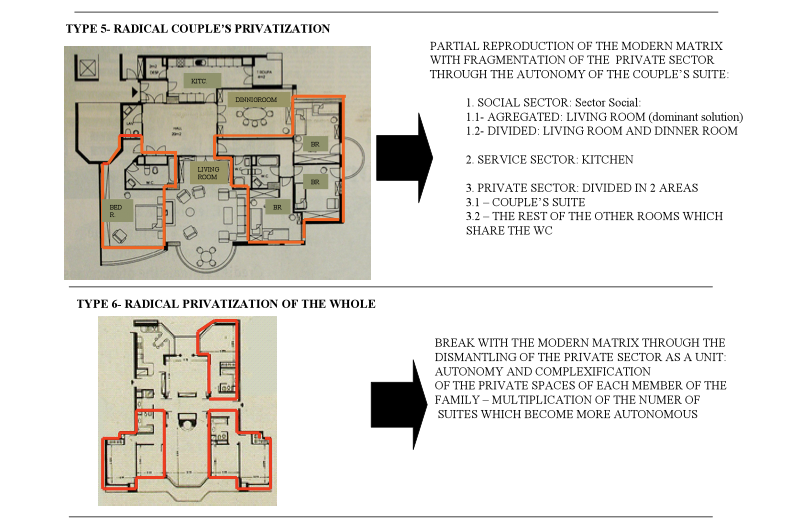

Este trabalho1 corresponde a um desenvolvimento inicial de uma pesquisa que deu origem a uma tese de doutorado, denominada “Casa e Mudança Social: interpretando as mudanças na sociedade Portuguesa através da casa”, concluída em 2010 no ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. Para identificar uma tipologia das estruturas domésticas, desenvolvemos uma análise de conteúdo das plantas internas da habitação, usando anúncios imobiliários que foram publicados em um jornal semanal popular Português (N = 70). A análise identifica uma tipologia composta por seis tipos de estrutura doméstica: 1) matriz moderna pura; 2) a transição tradicional–moderno; 3) a privatização conjugal contínua ou a matriz moderna com reforço moderado de privacidade conjugal; 4) a privatização genérica contígua; 5) a privatização conjugal radicalizada; 6) a privatização genérica radicalizada. Apesar da predominância da matriz doméstica moderna desenvolvida pelos arquitetos do Movimento Moderno, as poucas mudanças observadas foram essencialmente relacionadas com a esfera privada do lar: a área dos quartos. Isto deve ser interpretado como a personificação parcial de um dos principais aspectos da sociedade contemporânea: o processo de individualização e a necessidade de autonomia dentro da família.

Palavras-chave: Cultura material, Lisboa, evolução da habitação, padrões familiares

A habitação como cultura material

O objetivo geral desse trabalho é desconstruir os sistemas de significados incorporados em alguns dos principais tipos de habitação que têm caracterizado o desenvolvimento de Lisboa ao longo do século XX. O argumento central está relacionado com o grande potencial heurístico incorporado na produção material, como o ambiente construído. É resultado de uma abordagem cultural da habitação, que sublinha a sua dimensão comunicativa. Toda a produção material humana materializa algumas intenções que dão alguma força às culturas técnicas daqueles que estão envolvidos no processo. A probabilidade de conflito aumenta com o crescente número de atores envolvidos e isso é particularmente visível no setor imobiliário. Além da compreensão do processo produtivo de um determinado bem e do bem em si como um recurso para capitalização – seja por parte de um indivíduo, empresa ou até mesmo um grupo profissional -, há uma outra dimensão, muito menos reflexiva e que resulta do fato de todos os seres humanos serem socialmente enquadrados. O conceito de cultura material, assim, nos dá uma percepção das mercadorias como a expressão material do sistema de valores e normas de uma sociedade específica. Ele dá materialidade ao universo menos tangível dos conceitos.

Mas, apesar de se concentrar na análise dos tipos de habitação dominante, que se referem diretamente ao espaço de ancoragem da unidade social da família, privilegiamos suas representações sociais; o núcleo da nossa análise é o modelo familiar e as orientações normativas relativas que são incorporadas no espaço e que são lidas a partir dele. Essa abordagem é baseada na tipologia familiar criada na década de 1940 por Burguess e Locke e, posteriormente, revisado por Roussel (1992). Mesmo que sua explicação detalhada tenha intencionalmente ocorrido ao longo da explicação dos resultados, por enquanto vamos apenas fazer um breve, mas essencial, comentário: o propósito de que a tipologia serve para compreender a evolução da família na sociedade moderna, assumindo como critério central a especificidade das suas relações, isto é, no que se refere ao seu nível de democracia interna e paridade.

No entanto, não assumimos que haja uma estrita correspondência entre um tipo específico de habitação e um tipo específico de família, pois a realidade da vida social é muito mais complexa e heterogênea (ABOIM, 2005; BAWIN-LEGROS, 2001) que o universo de habitações, algo que, como comprovaremos, é muito mais homogêneo e unificado. Ao olhar para o espaço interior de uma habitação, é possível identificar um sistema espacial doméstico específico que é uma combinação de ambientes distintos ou compartimentos, que são designados para atender a prática de diferentes atividades domésticas - funções. Os compartimentos são então organizados, quer parcialmente como globalmente, por algumas regras e, como um todo, eles prefiguram uma unidade autônoma com uma lógica própria que lhes dá alguma inteligibilidade. Se concordarmos com isso, então fazemos a seguinte pergunta: o que pode um sistema doméstico nos dizer, não exatamente sobre seus ocupantes, mas sobre a perspectiva que seus produtores têm sobre os seus potenciais ocupantes, seus papéis, status e relações? Supondo que esse sistema doméstico pode ser percebido como um todo, no qual a inteligibilidade não resulta da soma de suas partes, mas da especificidade de cada uma dessas partes (composição funcional), bem como da posição relativa que cada uma delas assume no todo (estrutura), o que ele diz sobre os modelos de família que os construtores e arquitetos tinham em mente, mesmo que esses modelos não sejam completamente racionalizados por esses atores?

Essa pesquisa começou com um interesse inicial tanto no setor imobiliário como nos estudos sobre a morfologia da habitação, que foram essencialmente desenvolvidos para a cidade de Lisboa. No que diz respeito a esta última questão, é no campo da arquitetura onde encontramos uma tradição de pesquisa mais consolidada. No campo da Sociologia, a maioria dos textos assume a morfologia como uma dimensão menor ou satélite resultante de focar as análises sobre políticas públicas de habitação (BAPTISTA, 1996; GROS, 1994; JANARRA, 1994) ou sobre o seu impacto sobre o modo de vida e nível de satisfação do seu alvo (FREITAS, 1998). Há de fato uma tradição na sociologia que privilegia o setor público, em oposição ao setor privado. No entanto, existem algumas exceções na pesquisa portuguesa, as quais nos referimos brevemente: é o caso do trabalho desenvolvido sobre a habitação clandestina, bem como sobre a habitação de emigrantes (CASTRO, 1998; FERREIRA et al., 1985; PINTO, 1998; VILLANOVA et al., 1995). Ambos foram bastante representativos no conjunto da cena de habitação portuguesa e tem uma forte dimensão simbólica, consolidada através de uma estrutura peculiar de gosto. Mais recentemente tem havido algum interesse em torno do tema dos condomínios fechados, que tem muitas vezes uma forte orientação normativa decorrente da vontade, mais ou menos assumida, de criticar a destruição do conceito moderno de espaço público. (FERREIRA et al, 2001; RAPOSO, 2002).

Como já dissemos anteriormente, é na arquitetura que o trabalho sobre a morfologia da habitação é mais rico, algo compreensível devido à familiaridade desse campo específico com o objeto de estudo: o espaço. Mas, dado que a maioria dos estudos tipológicos desenvolvidos em arquitetura se centra em três critérios– morfológicos, estilísticos e funcionais (LAWRENCE, 1994, p.272) – deparamo-nos com uma certa falta de interpretação e com um excesso descritivo. Esse comentário não sugere, contudo, que esses estudos são fracos ou mesmo superficiais: esse forte componente descritivo pode ser desenvolvido como um recurso crucial para o diagnóstico, a fim de resolver alguns tipos de patologias, para orientar as estratégias de reabilitação ou para definir as diretrizes de classificação patrimonial. No entanto, após revisão bibliográfica sobre o assunto há um forte desejo de dar outro tipo de interpretação a essa enorme quantidade de informações. Neste sentido, o desafio era fazer uma tentativa exploratória de uma análise conotativa do espaço doméstico.

Abordagem metodológica

Há alguns aspectos que devem ser clarificados. Alguns deles, na medida em que contribuem para uma circunscrição do universo de estudo, podem restringir o conteúdo de análise para certa uniformidade. Em primeiro lugar, salientamos a adoção de três critérios intencionalmente restritivos: 1) a um território que nos leva a circunscrever a investigação à cidade de Lisboa, 2) o outro está relacionado ao tipo de construção, sendo a nossa opção de se concentrar apenas na habitação coletiva, tipo dominante de habitação em Lisboa, em contraste, por exemplo, com o Porto, onde há tradição relevante de habitação individual, 3) finalmente, a pesquisa analisa apenas o setor privado, apesar da importância do público, não tanto em termos quantitativos, mas mais em termos qualitativos; não podemos compreender a evolução dos modelos de habitação no setor privado, o qual é completamente dominante em Portugal, se não olharmos para o público, nomeadamente durante o regime autoritário - a matriz que caracteriza a maioria dos modelos de habitação em Lisboa, o Moderno, surgiu no setor público. Em segundo lugar, devemos chamar a atenção para o nosso compromisso com uma perspectiva diacrônica. Esta opção segue de certa forma o conceito de sociogênese desenvolvido por Norbert Elias, apesar de, neste caso, assumir um período muito mais curto (ver também LAWRENCE, 1987). Assumindo o tempo como uma variável central na modelagem de qualquer fenômeno social, reduz a probabilidade de desenvolver duas formas de pensamento sociológico, igualmente redutoras e simplistas: uma forma de pensamento essencialista e outra que subscreve uma espécie de big bang sociológico, que simplesmente ignora todo o patrimônio científico produzido até então. Na verdade, a densidade do fenômeno social só é alcançada se ele é pensado como um processo de longa duração, que pode não ter uma relação linear ou uma direção monista ou mesmo cumulativa: é através da incorporação do tempo na pesquisa sociológica que há mais abertura para compreender o nível de inovação do objeto estudado, bem como as especificidades e as formas que ele assume no presente. Em outras palavras, apenas pela incorporação do tempo, o pesquisador é capaz de compreender e sistematizar o real significado da lógica de mudança social que afeta a sociedade. Além disso, com a progressiva valorização da reabilitação urbana, o espaço das cidades é coabitado por edifícios que foram construídos em épocas diferentes e que encarnam diferentes universos simbólicos.

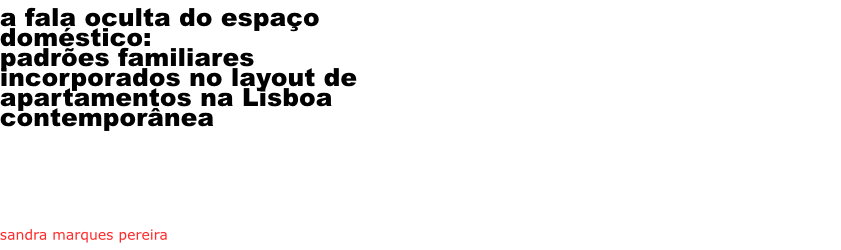

Nesse artigo vamos apenas incluir a análise dos tipos de apartamento ao longo das últimas três décadas do século 20, apesar do fato de que a pesquisa focou em todo o século. Para o período até a década de 60, que não será analisada aqui, a fonte central de informações foram as pesquisas tipológicas, que já foram desenvolvidas no domínio da arquitetura. Por este motivo, os tipos que foram analisados ao longo desse período são os que já estão institucionalizados nesse campo, como alguns dos tipos mais emblemáticos da história da habitação na cidade de Lisboa, a saber: o "gaioleiro" (até os anos 30), o "Estado Novo" (40) e o "moderno" (a partir do final dos anos 40 aos anos 50). Nos anos 60 há um tipo híbrido que mistura elementos da matriz moderna, que surgiu no setor público, com elementos do tipo "Estado Novo". Embora esse período não seja desenvolvido nesse artigo, bem como a habitação social, são apresentados na Figura 1 e resumidos em um texto breve.

Figura 1. Principais tipos de habitação, privadas e públicas, ao longo do século XX. Fonte: Casas Desmontáveis– Arquivo Fotográfico Municipal de Lisboa; Habitação Econômica: Arquivo Fotográfico Municipal de Lisboa; Habitação Econômica de Aluguel: foto da autora; Grandes Conjuntos: foto da autora; Categoria Residencial Única: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 1997:59; "gaioleiro": foto da autora; Tipo "Estado Novo": foto da autora; Transição para o moderno: foto da autora; Habitação Atual; anúncio publicado no Expresso: fotografias do autor; anúncio publicado no Expresso.

Setor Público

i. HABITAÇÃO ECONÔMICA: a reificação da ideologia do regime ou a dádiva aos institucionalizados;

ii. CASAS DESMONTÁVEIS: ambiente residencial como um instrumento de doutrinação da classe trabalhadora;

iii. HABITAÇÃO ECONÔMICA DE ALUGUEL: a resignação às soluções de habitação coletiva e a emergência do modus operandi técnico;

iv. GRANDE CONJUNTO MODERNO: "a máquina de habitar" ou a criação de condições internas para a democratização da família;

v. CATEGORIA RESIDENCIAL ÚNICA: a casa como um direito para os excluídos.

Setor Privado

i. GAIOLEIRO: a emergência da família moderna;

ii. TIPO ESTADO NOVO OU O TIPO PRIVADO DO REGIME: a reificação do imperialismo português;

iii. TRANSIÇÃO PARA O MODERNO OU O TIPO MIX: no sentido da democratização da família, ainda não social;

iv. PRODUÇÃO ATUAL: rápida diferenciação do invólucro versus lenta transformação do interior.

Para últimas décadas - 70 80 e 90 - a principal fonte de informação foi a publicidade imobiliária: reunimos a totalidade dos anúncios que foram publicados num dos jornais semanais mais conhecidos em Portugal - Expresso - desde sua primeira edição em 1973 e 1999 (539). Nesse período, a análise conotativa é precedida por uma sistematização prévia das plantas do espaço interior das habitações: a finalidade desse processo foi encontrar regularidades em termos morfológicos e de composição que dariam alguma inteligibilidade, a partir de uma abordagem sociológica, ao desenvolvimento dos espaços domésticos ao longo do século 20. Uma inteligibilidade alcançada através do reconhecimento dos diferentes tipos de sistemas de espaço doméstico.

Apesar das múltiplas dimensões que integram o nosso objeto, cada uma delas com uma relevância peculiar, por ora será privilegiada apenas uma: o espaço interior da habitação, através da análise de sua composição e modo de configuração, para compreender a existência de diferentes sistemas espaciais domésticos. Deve-se dizer que nem todos os anúncios têm a planta da habitação que está sendo comercializada, sendo o número total de plantas analisadas de 70 (N)2. Para concluir essa nota metodológica, algo mais deveria ser dito para justificar o caráter exploratório da pesquisa. Embora não seja essencial para esse trabalho, no período até a década de 1960 surgiu a questão científica da representatividade dos tipos estudados em relação ao universo habitacional do período relacionado; de fato, essa representatividade é variável de caso para caso. Quanto ao segundo período - as três últimas décadas do século - acreditamos que toda a publicidade imobiliária, mesmo que circunscrita a um único jornal, tem um inquestionável valor científico, devido ao atual macro contexto de uma economia de mercado. Apesar disso, admitimos duas possíveis fragilidades em termos de representatividade: um primeiro aspecto que está relacionado com a exclusão das promoções imobiliárias que não foram anunciadas ou com aquelas propagandas que não foram incluídas neste jornal. Parece, no entanto, que esse aspecto perde um pouco de sua importância, quando o setor se torna plenamente integrado no mercado, pois nesse contexto a publicidade ganha uma enorme importância - o resultado é uma explosão do número de anúncios, essencialmente, no final dos anos 80. O outro aspecto está relacionado ao fato de que a maioria dos anúncios não inclui as plantas da habitação, algo que reduz as potencialidades, especialmente em termos de pesquisa dos sistemas espaciais domésticos. Essas duas fragilidades só poderiam ser resolvidas se fôssemos capazes de recolher no município o conjunto dos projetos que foram aprovados. Mas isso seria uma tarefa bastante irrealista, por diversas razões, sendo a dimensão burocrática uma das mais dissuadoras.

A relação entre o regime ditatorial e a habitação

A história contemporânea de Portugal deve ser entendida no contexto do desenvolvimento da Europa durante esse período. No início do século XX, o país viveu o fim da monarquia e a implantação da República. No entanto, este regime republicano seria interrompido por um golpe militar em 1926, do qual resultou um governo liderado pelo ditador Salazar. Esse regime autocrático foi chamado de "Estado Novo" e era essencialmente conservador e nacionalista, um regime no qual a sociedade foi organizada e controlada por meio do corporativismo e governada pela trilogia ideológica: DEUS3 - PÁTRIA - FAMÍLIA. O regime iria durar mais de 40 anos, até 1974, quando uma revolução liderada por militares pôs fim a ele e começou um processo de democratização. A estabilização do regime democrático foi alcançada em meados dos anos 80 e coincidiu com a adesão nacional à Comunidade Européia (CRUZ, 2000, p. 123). Esse período deu um impulso considerável para a modernização Portuguesa, que teve vários efeitos da economia à sociedade: temos assistido a uma mudança rápida, que promoveu uma espécie de passagem direta de uma sociedade pré-moderna a uma sociedade associada à modernidade tardia, mas com várias contradições relacionadas à quase inexistência de uma fase intermediária.

No entanto, no longo período da ditadura (1926-1974), há diferentes momentos em termos políticos e econômicos, que têm forte impacto sobre a habitação. Há um primeiro período que corresponde à consolidação da ditadura política, que é reificado pela correspondente Constituição, promulgada em 1933. Até então havia pouca intervenção pública no setor da habitação. Há então um segundo momento que foi marcado por uma forte intervenção que foi, porém, quase centrada na cidade de Lisboa. De fato, Lisboa teve um enorme valor, uma vez que foi considerada a capital do Império Português, que era constituída por diferentes colônias, sendo as mais importantes as Africanas como Angola e Moçambique. Essa primeira onda de intervenção pública sobre a habitação tinha basicamente três efeitos, como que admitindo a existência de três diferentes "Portugais", pensados de um modo hierárquico: a) um Portugal menor, constituído pela população excluída e que deveria ser domesticada e doutrinada através do Programa de Casas Desmontáveis, b) um Portugal contido, formado por aqueles pertencentes às corporações protegidas pelo Estado e que merecem uma espécie de prêmio de fidelidade através do Programa de Habitação Econômica, c) um Portugal Imperial correspondente às elites, para quem era urgente construir um tipo específico de habitação (promovida pela iniciativa privada, mas completamente regulada pelo setor público), diferente do bem promíscuo "gaioleiro", e que poderia materializar, tanto em termos morfológicos quanto estéticos, o lado superior do programa ideológico "Estado Novo".

Apenas os dois primeiros programas foram promovidos diretamente pelo Estado, e ambos foram inspirados nas soluções conservadoras de habitação para a classe operária desenvolvidas no século XIX. No final da década de 1940, houve uma nova mudança dentro dessa intervenção pública, como resultado da Segunda Guerra Mundial, que aumentou os preços dos materiais utilizados na construção. Esta foi essencialmente realizada através de soluções dirigidas ao segundo Portugal, o das classes médias. De fato, se o Programa de Habitação Econômica pressupunha uma intervenção centrada na habitação individual - a única solução permitida na época aos proprietários particulares de suas casas -, a nova realidade provou a irracionalidade da solução: uma solução economicamente insustentável. Portanto, a repudiada ideia anterior de habitação coletiva se tornou a opção mais realista, algo que seria materializado através do Programa de Habitação Econômica de Aluguel.

Esse é precisamente o momento em que a matriz doméstica moderna entra no setor público, algo que começa num processo de generalização progressiva da sua influência, não só sobre a habitação pública, mas também no mercado privado. Se esse primeiro momento da entrada do Movimento Moderno sobre a habitação pública é essencialmente centrado sobre a estrutura doméstica e sobre a adoção de métodos científicos de programação do espaço, a fim de otimizar os recursos ou a racionalização (do espaço em si até os materiais), a década de 60 revela o pressuposto de que houve uma grande adesão ao espírito da Carta de Atenas. Mas essa mudança nos princípios de programação da habitação pública não é desprovida de sentido. Na verdade, ela revela as diferentes fases da autocracia. Portanto, seu maior impacto foi alcançado na primeira fase, 1933-1945, quando o quadro jurídico e institucional do regime social corporativo foi criado (CRUZ, 1988, p.41). Durante esse período, o espaço residencial era, de fato, concebido como uma fonte material, por excelência, para a reificação do quadro ideológico procurado pelo regime. O desenvolvimento do Programa de Habitação Econômica de Aluguel, que começou no final de 1940 revela os primeiros sinais de enfraquecimento da componente ideológico do regime, uma vez que começou a ser substituído lentamente por outro tecnicamente emergente (BAPTISTA, 1996). Nos anos 60, essa abordagem já é dominante. A década de 1960 tem em si as raízes da destruição inevitável do regime, algo que teve diferentes expressões, com diferentes níveis de visibilidade: das mais óbvias crises estudantis até os princípios programáticos da habitação menos compreensíveis. Na verdade, como vamos explicar adiante, a matriz moderna traz, sob a sua especialidade, um propósito revolucionário ou um Estado democrático. Portanto, o espaço residencial era politicamente precursor, através da implementação de uma matriz de habitação com princípios de democratização, incorporada antes da implementação efetiva da democracia, que só aconteceria em 1974.

Sob a forma da individualização

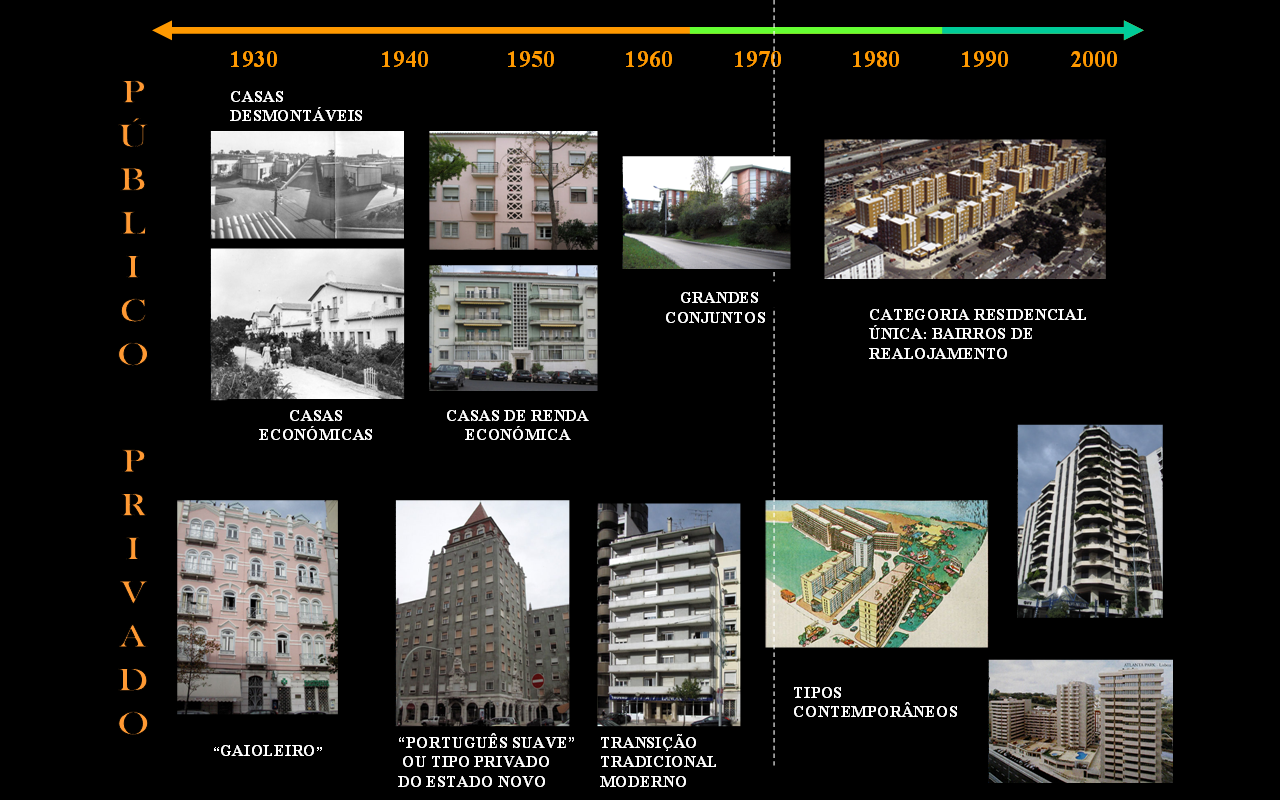

Os resultados aqui apresentados estão relacionados apenas às três últimas décadas do século XX e para o setor privado de bens imóveis. No entanto, é indispensável se referir a esses dois tipos particulares que têm caracterizado o setor privado ao longo da primeira metade do século: "gaioleiro" e do "Estado Novo" ou o tipo particular de regime (ver Figura 2). O "gaioleiro" é um dos tipos de habitação mais emblemáticos até 1930, essencialmente destinado à burguesia e podendo ser retomado nos seguintes termos:

1 Esse artigo é uma adaptação de um trabalho apresentado na Rede Européia de Investigação em Habitação (ENHR) de 2006, em Ljubljana na Eslovênia.

2 Em alguns casos, há até mais de uma planta. Embora não muito representativos, estes casos referem-se a dois tipos de situações: uma primeira, mais comum, relacionada àqueles anúncios que incluem várias plantas, cada uma delas correspondendo a apartamentos com diferentes dimensões em um mesmo edifício (1 dormitório/2 dormitórios/3 dormitórios etc.); a outra situação, menos usual, quando o construtor ou a agência de publicidade apresenta várias plantas referindo-se a diferentes edifícios.

3 Católico.

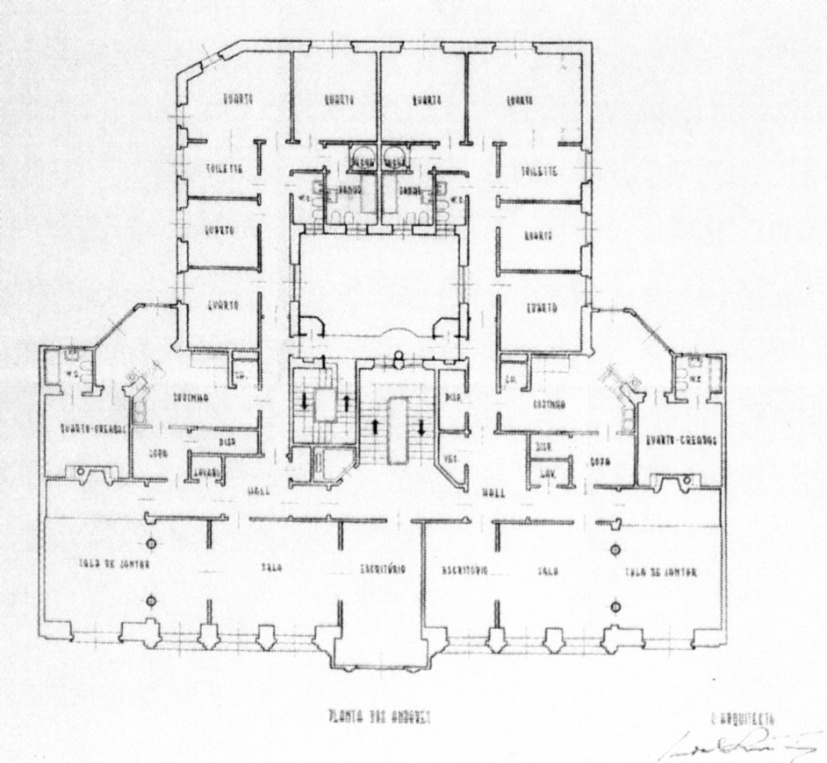

Figura 2. Layout apartamento Gaioleiro. Fonte: APPLETON, 2001, p.29.

i. Distinção entre a fachada frontal e a parte de trás: a) formal - materiais nobres utilizados na fachada / materiais inúteis utilizados na parte traseira; b) funcional - a fachada está relacionada com momentos extraordinários e as costas é o lugar onde ocorre o cotidiano familiar, c) simbólico - a fachada reifica as aspirações sociais da família (a aparência) e as costas representam a sua essência;

ii. Estrutura do edifício e da habitação condicionadas pelas condições urbanísticas e técnicas: estreitos e muito profundos;

iii. Divisão do espaço doméstico interior através do gênero e de critérios de autoridade: a) fachada: 1º espaço masculino = escritório ou saleta, o compartimento que fica nas proximidades da entrada da casa e tem uma porta que confere ao "chefe de família" a autonomia necessária; 2º O espaço familiar representacional = sala de estar, sala proibida para as crianças e reservada para visitas, que funcionava para sublinhar o estatuto social atingido ou projetado pela família; 3º espaço feminino = toillete (ipsis verbis), um espaço merecido para a mulher da alta burguesia, cujo modo de vida era definido por referência à sociedade francesa, onde o culto à aparência feminina era um valor fundamental; b) fundos: cozinha - espaço feminino, sala de jantar - espaço familiar informal.

iv. Sub-valorização do setor privado (quartos) com a sua localização entre as duas zonas, o que evidencia a importância relativamente pequena do indivíduo dentro da família burguesa do início do século 20.

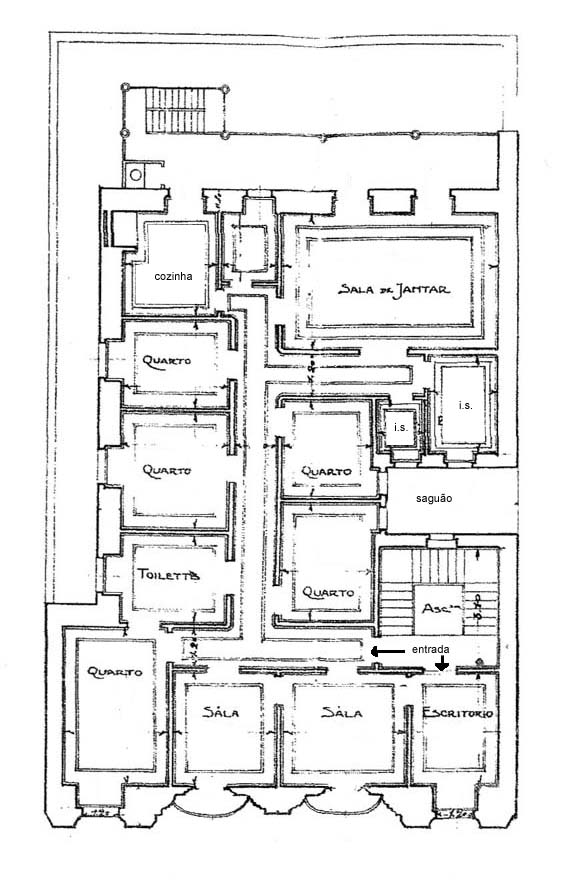

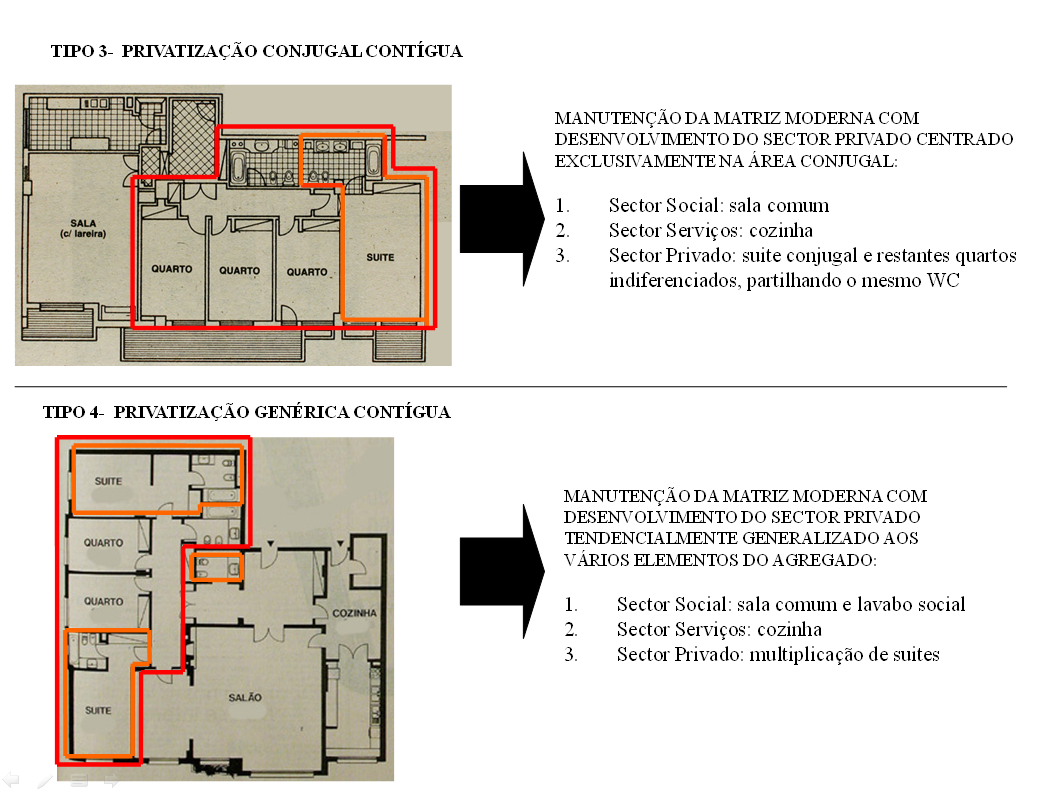

O tipo "Estado Novo" (ver Figura 3) ou o tipo particular do regime define um estilo Português distinto, inspirado na arquitetura dos períodos magníficos da história portuguesa. Além disso, ele executa a reestruturação do espaço interior através de uma importação parcial dos princípios da arquitetura moderna, com um triplo objetivo:

Figura 3. Layout de apartamento do Estado Novo. Fonte: PEREIRA, 2011, p.28.

i. Criar as condições para a institucionalização da família nuclear, algo que pressupõe o seu próprio fechamento. Pela institucionalização nos referimos a um modelo de família conceituada por Burguess e Locke em 1945 e definida por "relações hierarquizadas entre parceiros, a submissão do indivíduo aos interesses do grupo, a diferenciação dos papéis entre os sexos, uma afetividade morna.” 4 (ROUSSEL, 1992, p.90).

ii. Criar as condições para a domesticação das mulheres. Com isso, referimo-nos à intenção do regime de ancorar as mulheres ao espaço doméstico, de modo a criar as condições materiais exigidas pelo seu ideal feminino, caracterizado por uma tripla função: esposa, mãe e dona de casa.

iii. Formalizar e clarificar as hierarquias sociais internas, algo que não existia no modelo anterior, onde era visível uma espécie de promiscuidade entre a família e os seus empregados.

Assim, para o cumprimento desse triplo objetivo, o tipo "Estado Novo" incorporará da Matrix Moderna dois aspectos fundamentais: a) a introdução de elementos nodais que fazem a transição entre o público e o privado (o hall de entrada e vestíbulos); b) a lógica racionalista do espaço doméstico, que se organiza em três setores principais, o social, os serviços (cozinha e espaços relacionados) e o íntimo, que congrega os quartos e os banheiros, que se tornam mais segregados em relação à entrada (AMORIM, 1997). Mas a lógica de simplificação que define a matriz moderna é, nesse momento, voluntariamente ignorada, uma vez que negam completamente tal propósito triplo. Assim, se a clara separação destes três setores viabiliza a privatização da vida familiar, o desenvolvimento de um setor bastante complexo dos serviços - com a introdução, por exemplo, do quarto de empregada e banheiro que não existiam antes, além de ter uma passagem exclusiva da cozinha, localizada no espaço mais segregado do setor íntimo –materializa de uma só vez o reforço das hierarquias sociais internas e as condições do espaço que permitem que as mulheres sejam profissionais do espaço doméstico. Por outro lado, ele reproduz a mesma complexidade que caracterizava o setor social dos modelos anteriores, com a sua partição em três espaços: uma sala mais masculina (o escritório localizado nas proximidades da entrada), uma outra mais formal e representativa (a sala de estar entre esses dois) e um espaço mais acolhedor e privado visando a vida familiar atual (a sala de jantar, localizado no ponto mais extremo em relação à entrada).

Depois desses parênteses, podemos apresentar nossos resultados de forma mais consistente. Na sequência de nossos procedimentos metodológicos que apontavam para uma sistematização prévia das 70 plantas incluídas no "Expresso", coletadas em propagandas de 1973-1999, chegamos a um sistema de tipologias do espaço doméstico composto por seis tipos. Então, categorizamos cada uma das plantas da amostra de acordo com essas tipologias e, após isso, desenvolvemos o tratamento estatístico. Os critérios tipológicos adotados para a construção de cada sistema de espaços domésticos são a definição de diferentes lógicas utilizadas na estruturação dos setores, tanto isolados como todo o sistema: social, serviços e íntimo. Nosso ponto de partida é a matriz do tipo moderno puro, tipo 1. Esse tipo surgiu em Portugal no final dos anos 40 no setor público. O Movimento Moderno internacional na arquitetura teve um duplo objetivo: por um lado, um projeto social que seria capaz de concretizar os ideais da modernidade através do espaço, ideais como a emancipação, a democratização, racionalização e, por outro lado, um projeto destinado a reforçar a posição da arquitetura, em uma sociedade progressivamente especializada em meios científicos e técnicos (PEREIRA, 2004). Na verdade, o conteúdo desse projeto social revela um sistema espacial doméstico específico que aponta para uma passagem da "família instituição" para a "família companheirismo", ambas conceituadas por Burguess e Locke. Roussel, na tentativa de "resolver o caráter excessivamente dicotomizado desses dois modelos, alargou seu espectro normativo, através da introdução de quatro modelos: sobre o lado mais tradicionalista, podemos encontrar a "família instituição" e a "família aliança"; sobre o lado mais moderno, podemos encontrar a "família fusão" e a "família associação" ou "família clube" (ABOIM, 2006, p.172).

Devemos concentrar-nos sobre esse segundo lado, o modernista, uma vez que a matriz moderna pura é uma estrutura espacial que mostra uma forte proximidade com o modelo de família fusão. Ambos os modelos da família moderna são distintas das tradicionais, porque introduzem na vida familiar novos princípios de democracia e informalidade. Mas, se o modelo fusão é essencialmente "coletivista", no qual prevalece uma atmosfera congregacional, o modelo associação comprova o pressuposto do indivíduo e o fortalecimento de ideias, como a autonomia ou realização pessoal. Se, no seio da família fusão a felicidade de cada um dos seus membros é uma consequência da felicidade do conjunto, no seio da família associação a felicidade do conjunto é consequência da felicidade de cada um de seus membros. Assim, as especificidades da matriz moderna pura (tipo 1) que justificam a sua associação com o modelo de família fusão são as seguintes:

i. concentra a área habitável, algo que torna a vida familiar cada vez mais confluente, reduzindo as possibilidades de distância espacial entre os indivíduos (ver Figura 4);

ii. elege a sala como o espaço fundamental, pondo fim à separação de funções no setor social; essa sala de estar reúne as atividades "coletivas" de todos os membros da família, reificando a supremacia do todo (da família), que supostamente foi unificado, sobre os seus elementos (indivíduos);

iii. simplifica o setor de serviços - com a introdução da "cozinha laboratório", ou com a remoção de outras funções que faziam parte dele, como o quarto de empregada ou a despensa - que se torna próximo do setor social, algo que contribui para "libertar" a mulher e, de certa forma, reduz a divisão sexual dos espaços e, consequentemente, a divisão de papéis entre o casal;

iv. dá uma configuração igualitária para o setor íntimo, que mostra certa concepção de indivíduos mais indiferenciada em termos de poder.

Figura 4. Tipologia dos sistemas espaciais domésticos (Fonte: todos os layouts dos anúncios publicados no Expresso).

Apesar de ter selecionado a matriz moderna pura como uma espécie de "marco zero" da nossa tipologia, devido à sua centralidade como referência da maioria das habitações construídas pelo menos a partir dos anos 40, ele só aparece como o tipo dominante dentro do setor privado na década de 80. Consciente da pequena dimensão da nossa amostra, que não permite uma generalização dos resultados, é possível, contudo, apresentar algumas hipóteses. O período pós-revolução (25 de abril de 1974) não lança uma mudança imediata para a democratização dos tipos de habitação oferecidos no mercado. Assim, e apesar de não serem representativos devido ao pequeno número de plantas coletadas nesse período (5 plantas, sendo duas deles anteriores ao dia da Revolução), os dados mostram que o tipo 2, a transição tradicional-moderno, iria sobreviver à revolução.

Na verdade, esse tipo surgiu no setor privado na década de 1950, e tornou-se dominante na década de 60. É um tipo híbrido que otimiza alguns aspectos da matriz moderna pura, que cresceu dentro do setor público, com alguns outros mais tradicionais, que foram inspiradas no tipo "Estado Novo". Assim, a adoção parcial da matriz moderna pura é relativa à racionalização dos espaços realizada através da adoção de ambos: uma planta (prédio e do apartamento) com um formato quadrado ou retangular, e da lógica de organização dos setores do espaço doméstico. No entanto, ele mantém o mesmo setor de serviços complexos, que foi introduzido pelo tipo particular do regime. Se para a área do quarto há uma reprodução geral da mesma simplicidade da matriz moderna, para o seu setor social isso não é verdade: apesar da progressiva generalização da sala, ainda há uma manutenção frequente de uma divisória entre a sala de jantar e a sala de recepção, apesar de posicionados um ao lado do outro. Mas mesmo quando há uma fusão desses dois ambientes, existe a necessidade de distinguir essas duas funções domésticas através da introdução de alguns elementos mais ou menos flexíveis, tais como uma porta ou uma meia parede. Esse tipo tem ainda outro aspecto que merece alguns comentários e que se refere ao setor de serviços, que pode assumir duas configurações diferentes: rígida ou flexível. A primeira refere-se à situação em que o acesso ao quarto de empregada é feito exclusivamente através da cozinha; a segunda, mais flexível, compreende aquelas situações nas quais se dá autonomia ao quarto de empregada, o que significa que o seu acesso torna-se integrado num vestíbulo comum, mesmo que localizado nas proximidades da cozinha. Isto não implica necessariamente o reconhecimento dos direitos da empregada doméstica. No entanto, o pressuposto da flexibilidade agregada a esta área é um forte sinal da duplicidade no uso do espaço doméstico, que revela um momento de mudança social: não abolir de uma vez, a possibilidade de ter uma empregada doméstica mas, ao mesmo tempo, permitir transformá-lo em mais um quarto para algum elemento da família nuclear. Portanto, a adesão incompleta à matriz moderna pelos promotores privados ao longo da década de 60 revela o seguinte pressuposto: houve uma percepção, mais ou menos consciente, da inadequação de um modelo que simplificava extremamente a vida doméstica, provavelmente não racionalmente percebido em seus pressupostos democráticos. Enfim, esse modelo não se encaixa em uma sociedade que, apesar de ser mais aberta do que era antes, não compartilha um desejo hegemônico de democracia. Na verdade, a maioria da população não tinha nenhuma visão política precisa, porque não havia níveis altos de alfabetização. Além disso, a crítica mais geral à autocracia seria uma consequência direta da guerra colonial, que começou em 1961, e que teria um impacto direto na vida privada das famílias. Quanto ao período pós-revolucionário e, como já dissemos antes, o tipo de transição tradicional-moderno é o dominante, sendo apenas suplantado pela matriz pura moderna na década de 80. Esse fato é compreensível a partir de dois argumentos: por um lado, a longa duração do processo de produção da habitação, que aumenta a probabilidade de obsolescência de um produto que é projetado em três anos (período médio) antes de serem concluídos; por outro lado, a incorporação imobiliária sofreu uma espécie de torpor ao longo desse período, como resultado de um ambiente político e econômico hostil à iniciativa privada. No entanto, a década de 1980 representa a recuperação do mercado imobiliário, que teve início, durante os anos 1960, com o começo da indústria do turismo no Algarve e a expansão da periferia de Lisboa. Mas as mudanças que irão determinar a habitação a partir de agora serão muito mais radicais no que diz respeito à construção e ao ambiente residencial do que dentro do apartamento. Aqui, nós identificamos um caminho de continuidade da matriz moderna pura: não há nenhum novo tipo de função que justifica o desenvolvimento de ambientes inovadores e a lógica dos setores é mantida. Assim, o tipo 6 - a privatização genérica radicalizada, que pressupõe um rompimento com o desmantelamento do setor privado e sua atomização, tem apenas 1 caso.

|

ANOS 1970 |

1980 - 1985 |

1986 - 1989 |

1990 - 1992 |

1993 - 1995 |

1996 - 1999 |

TOTAL |

|

|

tipo

1:

|

1 |

4 |

- |

5 |

3 |

2 |

15 |

|

tipo

2:

|

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

|

tipo

3:

|

- |

3 |

2 |

14 |

19 |

- |

38 |

|

tipo

4:

|

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

5 |

10 |

|

tipo

5:

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

|

tipo

6:

|

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

5 |

7 |

3 |

23 |

25 |

7 |

70 |

Tabela 1. Frequência de tipos de sistemas de espaços domésticos.

Mesmo assim, esse caminho de continuidade contém um novo aspecto que torna uma posição dominante: o estabelecimento de condições espaciais que permitam o reforço da privatização na vida doméstica. Isso significa que há um investimento no setor privado da habitação, tanto através da introdução do quarto, com banheiro exclusivo, e a generalização do WC social, que impede as visitas de entrarem no espaço íntimo da família. Em um primeiro momento, o fortalecimento da intimidade é exclusivamente dirigido ao casal, cujo quarto fica localizado na parte mais segregada do setor privado - tipo 3 ou a privatização conjugal contígua. Esse tipo aparece na década de 1980, em uma espécie de competição com a matriz moderna pura, que suplanta totalmente o tipo 2 - a transição tradicional-moderno - por esse período. Na verdade, o tipo 3 se torna dominante na década de 90, representando mais da metade das plantas analisadas: 38. A escolha do casal como o alvo privilegiado desse processo de privatização pressupõe, mas não necessariamente de forma racionalizada, a transformação da intimidade e da centralidade do amor confluente (GIDDENS, 1995, p.41) nas sociedades contemporâneas. Mas a hipótese extrema desse princípio é alcançada com o tipo 5 – privatização conjugal radicalizada, que apresenta uma fragmentação parcial do setor privado. Assim, esse tipo libera o quarto do casal (e seu banheiro) do conjunto dos quartos e dá a ele autonomia, como se fosse um novo setor doméstico. No entanto, esse é um tipo que não tem nenhuma expressão na nossa amostra.

Numa segunda fase, assistimos a uma generalização do princípio de privatização contínua presente no tipo 3. Isso se torna perceptível na multiplicação do número de quartos que incluem um banheiro e se refere ao tipo 4 – privatização genérica contígua. Na verdade, acreditamos que esse tipo será o dominante em um futuro próximo, principalmente no que diz respeito a apartamentos maiores. Esta crença resulta, em parte, da seguinte ideia: as razões que explicam esta tendência de homogeneidade do tipo 3 devem ser procuradas no modus operandi da maioria dos construtores de habitação. Há três aspectos, interdependentes, que são centrais e que retiram qualquer presunção sobre o fato de que as mudanças no tipo de habitação acabariam por resultar de um conhecimento completo das transformações sociais por parte dos seus construtores: a) os investimentos para o diagnóstico da demanda e do planejamento do produto são feitos com os vendedores, que transmitem sua sensibilidade no mercado ou, em alguns casos, há um rápido levantamento do entorno, a fim de ter algum tipo de informação sobre os produtos com mais probabilidade de serem mais facilmente vendidos; b) a competitividade é realizada através da imitação da produção das empresas rivais, as que são consideradas bem sucedidas no mercado; c) finalmente, os construtores sustentam uma lógica quantitativa de análise social, com dois resultados: a diversificação dos apartamentos com diferentes tamanhos, especialmente pelo aumento dos menores (um ou dois quartos), que responderiam à diminuição da dimensão média das famílias e para o crescimento do número de famílias unipessoais; a multiplicação das soluções que tiveram boa aceitação, como o quarto com banheiro ou o WC social. Se a concepção do amor nas sociedades contemporâneas tem sido tratada por diversos autores, de Luhman à Bauman, seu desenvolvimento depende de um processo compreendendo: a individualização, que já estava presente no conceito clássico de Gesellshaft. Para citar Lash (1993, p.18), no contexto de individualização "a estrutura força a agência a ser livre". Na verdade, se as relações emocionais são hoje mais livres e impugnáveis, isso acontece porque eles são um componente das biografias performáticas resultantes de um contexto de porosidade das instituições (WUTHNOW, 1999), que obriga os indivíduos a escolher. A individualização é, portanto, visível no tipo 4 – privatização genérica contígua, pois reforça as condições para a autonomia individual. De fato, esse tipo pressupõe as condições espaciais para o desenvolvimento do modelo “família associação” conceituado por Roussel, no qual a autonomia individual suplanta o modus vivendi fusional. Além disso, o investimento em banheiros pode ser um sintoma de valorização do corpo nas sociedades da Modernidade Tardia (TURNER, 1992; SYNNOT, 1993). No entanto, esse investimento não parece seguir a sofisticação geral das condições de satisfação com o corpo, algo completamente assumido pela indústria do lazer.

Considerações finais

A homogeneidade que define a grande maioria dos tipos de habitação fornecida não pressupõe uma homogeneidade equivalente na vida social. A principal razão para essa afirmação é o pressuposto de que o espaço não é uma variável independente, mas uma expressão e um recurso de uma formação social específica para o qual concorrem vários fatores, tais como culturais, econômicos e políticos. Além disso, o "consumo" do espaço ou, para ser mais preciso, o uso do espaço doméstico não reflete as intenções mais ou menos reflexivas, em sua concepção presumida, já que há uma inevitável renegociação dos seus significados que resulta das idiossincrasias sociais e culturais dos indivíduos (FEATHERSTONE, 1997, p.94).

Na verdade, a supremacia de tipos de habitação com sistemas domésticos espaciais que personificam orientações normativas mais democráticas está longe de produzir ambientes familiares semelhantes ou representações sociais hegemônicas. No que diz respeito a essa questão, vários estudos têm demonstrado uma enorme diversidade de situações em que coexistem orientações normativas que deveriam ser sequenciais: junto às famílias com um perfil mais congregacional, existem outras mais centradas na autonomia individual, e mesmo aquelas que assumem uma condição "híbrida"; ao lado de situações que revelam um nível superior de democracia, no seio das relações familiares e do casal, há outras muito mais ligadas ao figurino institucional (ABOIM; WALL, 2002; ABOIM, 2005). Mas esse é, afinal, um sintoma da natureza paradoxal da Modernidade Tardia em Portugal. Enfim, a pesquisa revela uma oferta homogênea que não contempla toda a mudança cultural ocorrida na sociedade portuguesa.

Referências bibliográficas

ABOIM, S.; WALL, K. Tipos de família: interacções, valores e contextos. Análise Social, nº 163, p.475-506.

ABOIM, S. As orientações normativas da conjugalidade. In: WALL, K. Famílias no Portugal contemporâneo. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais/ICS, 2005.

ABOIM, S. Conjugalidades em mudança. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2006.

AMORIM, L. The sectors’ paradigm: understanding modern functionalism and its

effects in configuring domestic space. In: MAJOR, M.; AMORIM, L; DUFAUX, F. (ed). Proceedings of the Space Syntax First International Symposium. UCL, London, v. 2, 1997, p.18.1-18.13.

APPLETON, J. G. A reabilitação de edifícios “gaioleiros”: estudo de um quarteirão nas Avenidas Novas. Dissertação (Mestrado). Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisboa, 2001.

4 Traduzido do francês: “des relations hiérarchisées entre partenaires, la soumission de l’individu aux intérêts du groupe, la différentiation des rôles entre les sexes, une affectivité tiède” (ROUSSEL, 1992, p.90).

BAPTISTA, L. V. A Cidade em reinvenção: crescimento urbano e emergência das políticas de habitação social: Lisboa Século XX. Ph.D. Sociologia / FCSH-UNL, 1996.

BAWIN-LEGROS, B. Families in Europe: a private and political stake – intimacy and solidarity. Current Sociology, n.49, 2001, p.49-65.

CASTRO, A. As construções dos emigrantes e a legitimidade de uma estética singular. Sociedade e Território, nº 25/26, 1998, p.80.

CRUZ, M. B. O Partido e o Estado no Salazarismo. Lisboa: Presença, 1988.

CRUZ, M. B. A evolução da Democracia Portuguesa. In: PINTO, A. C. (coord.). Portugal contemporâneo. Madrid: Sequitur, 2000.

FEATHERSTONE, M. Culturas globais e culturas locais. In: FORTUNA, C. (org.) Cidade, cultura e globalização. Celta: Oeiras, 1997.

FERREIRA, A. F.; GUERRA, I; MATIAS, N.; STUSSI, R. Perfil social e estratégias do clandestino: estudo sociológico da habitação clandestina na região de Lisboa. Lisboa: CIES, Instituto Superior de Ciências do Trabalho e da Empresa, 1985.

FERREIRA, A. F.; GUERRA, I.; PINTO, T. C. L’usage et l’appropriation du Logement a Telheiras. Sociedade e Território, nº Especial, 1990, p.43-51.

FERREIRA, M. J. et. al. Condomínios habitacionais fechados: utopias e realidades. Série Estudos, nº4, Portugal: Centro de Estudos de Geografia e Planeamento Regional- UNL, 2001.

FREITAS, M. J. Pensar os espaços domésticos de realojamento. Sociedade e Território, nº 25/26, 1998, p.150-161.

GIDDENS, A. Transformações da intimidade: sexualidade, amor e erotismo nas sociedades modernas. Oeiras: Celta, 1995.

GROS, M. Pequena história do alojamento social em Portugal. Sociedade e Território, nº 20, 1994, p.80-100.

JANARRA, P. A política urbanística e de habitação social no Estado Novo. Dissertação (Mestrado), Sociologia, ISCTE, Lisboa, 1994.

LASH, S.. Reflexive modernization: the aesthetic dimension. Theory, Culture and Society, v. 10, 1993, p.9-65.

LAWRENCE, R. J. Housing, dwellings and homes: design theory, research and practice. Nova Iorque: Jonh Wiley & Sons, 1987.

LAWRENCE, R. J. Type as analytical tool: reinterpretation and application. In: K.A. FRANCK; L.H. SCNEEKLOTH (ed.). Ordering space: types in architecture and design. Nova Iorque: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1994, p.271-287.

PEREIRA, S. M. Pressupostos ideológicos da casa actual: o espaço como veículo do ideário moderno. Cidades, nº 8, 2004, p.77-93.

PEREIRA, S. M. Cenários do espaço doméstico: modos de habitar. In: MATTOSO, J. (dir.); ALMEIDA, A. N. de A. (coord.). História da Vida Privada em Portugal. Os Nossos Dias. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, 2011, p.16-47.

PINTO, T. C. Modelos de habitat, modos de habitar: o caso da construção clandestina do habitat. Sociedade e Território, nº 25/26, 1998, p.32-44.

RAPOSO, R. Novas paisagens: a produção social de condomínios fechados na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Tese (Doutorado), Sociologia Económica e das Organizações, ISEG/UTL, Lisboa, 2002.

ROUSSEL, L. Les types de famille. In: F. SINGLY. (org.). La famille: l’état des savoirs. Paris: La Découverte, 1992.

SYNNOT, A. The body social: symbolism, self and society. London: Routledge, 1993.

TURNER, B. S. Regulating Bodies. London: Routledge, 1992.

VILLANOVA, R.; LEITE, C.; RAPOSO, I. Casas de sonhos: emigrantes construtores no norte de Portugal. Lisboa: Salamandra, 1995.

WUTHNOW, R. The culture of discontent: Democratic Liberalism and the challenge of diversity in Late-Twentieth-Century. In: NEIL, S. J.; ALEXANDER, J. C. (ed.). Diversity and its discontents: cultural conflict and common ground in contemporary American Society. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

The hidden talk of domestic space: family patterns embodied in the apartment layouts of contemporary Lisbon

Sandra Marques Pereira é Sociologist and Doctor in Sociology, researcher at the Center of Socioeconomic Change and Territory Studies (DINÂMIA-CET) at the Lisbon Universitary Institute (ISCTE), Portugal, she studies domestic scene and ways of living, residential trajectories and Lisbon metropolization.

How to quote this text: Pereira, S. M., 2011. The hidden talk of domestic space: family patterns embodied in the apartment layout of contemporary Lisbon, V!RUS, [online] June, 5. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus05/?sec=4&item=9&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

Abstract

This paper1 corresponds to an initial development of a research that gave rise to a PhD thesis, called Home and Social Change: reading Portuguese society change through home, concluded in 2010 in ISCTE- Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. In order to identify a typology of domestic structures, we developed a content analysis of the interior plans of housing, using real estate advertisements that were published in a popular Portuguese weekly newspaper (N= 70). The analysis identifies a typology composed by 6 types of domestic structure: 1) the pure modern matrix; 2) the transition traditional – modern; 3) continuous couple’s privatization or the modern matrix with moderate reinforcement of conjugal privacy; 4) continuous privatization of the whole family; 5) radical couple’s privatization; 6) radical privatization of the whole. Despite the predominance of the domestic modern matrix developed by the architects of the Modern Movement, the few changes observed were essentially related to the private sphere of home: the bedroom area. This should be interpreted as the partial embodiment of one of the main aspects of contemporary society: the process of individualization and the need for autonomy within the family.

Keywords: material culture, Lisboa, housing evolution, family patterns.

On housing as material culture

The general purpose of this paper is to deconstruct the meaning systems that are embodied in some of the main housing types that have characterized the development of Lisbon along the 20th century. The central argument is related with the great heuristic potential incorporated in material production such as the built environment. It results from a cultural approach of housing which underlines its communicative dimension. All human material productions materialize some intentions which give some sort of strength to the technical cultures of those who are involved in the process. The probability of conflict rises with the growing number of actors involved and this is particularly visible in the real estate sector. Beyond the comprehension of the productive process of a specific good and of the good itself as a resource to capitalization - being it from an individual, an enterprise or even a professional group -, there is another dimension, much less reflexive and which results from the fact that all human beings are socially framed. The concept of material culture thus gives us a perception of goods as the material expression of the system of values and norms of a specific society. It gives materiality to the less tangible universe of concepts.

But, while focusing in the analysis of the dominant housing types, which refer directly to the anchorage space of the social unit of family, we privilege its social representations; the core of our analysis is the familiar models and the relative normative orientations that are embodied in space and that are readable from it. This approach is based on the family typology created in the decade of 1940 by Burguess and Locke and afterwards reviewed by Roussel (1992). Even though its detailed explanation will intentionally take place along the explanation of the results, for now we will just make a brief, but essential, comment: the purpose of that typology is to understand the evolution of family in Modern society assuming as the central criteria the specificity of its relations, namely in what regards to their inner level of democracy and parity. Nevertheless, we do not assume that there is a strict correspondence between a specific housing type and a specific type of family, since the reality of social life is much more complex and heterogenic (Aboim, 2005; Bawin-Legros, 2001) than the universe of housing, something that, as we are going to prove, is much more homogeneous and unified. When looking at the interior space of a house it is possible to identify a specific domestic spatial system which is a combination of distinct rooms or compartments that are designated to fulfil the practice of different domestic activities – functions. Those compartments are then organized, either partially and globally, by some rules and, as a whole, they prefigure an autonomous unity with a proper logic that gives it some intelligibility. If we agree with this, then we make the following question: what can a domestic system tell us, not exactly about its occupants, but about the perspective that its producers have on its potential occupants, their roles, status and relations? Assuming that this domestic system can be perceived as a whole which intelligibility does not result from the sum of its parts, but from the specificity of each of those parts (functional composition) as well as from the relative position that each of them assumes within the whole (structure), what does it tell about the family models that the builders and architects had in mind even if these models may not be completely rationalized by those actors?

This research began with an initial interest on both the real estate sector and on the studies about housing’s morphology that were essentially developed to the city of Lisbon. In what respects to this last issue, it is in the field of architecture that we find a more consolidated research tradition. In the field of Sociology, the majority of the texts assume morphology as a minor or satellite dimension resulting from focusing the analyses on housing public policies (Baptista, 1996; Gros, 1994; Janarra, 1994) or on its impact on the way of life and level of satisfaction of its target (Freitas, 1998). There is in fact a tradition in Sociology that privileges the public sector in spite of the private one. Nevertheless there are some exceptions in the Portuguese research that we briefly refer: that is the case of the work developed on illegal housing (Ferreira et al., 1985; Pinto, 1998) as well as on the emigrant housing (Castro, 1998; Villanova, Leite and Raposo, 1995). Both of them were quite representative in the whole of the Portuguese housing scene and have a strong symbolic dimension consolidated through a peculiar structure of taste. More recently there has been some interest around the theme of gated communities that has quite often a strong normative orientation resulting from the wish, more or less assumed, to criticize the destruction of the modern concept of public space (Ferreira et al., 2001; Raposo, 2002).

As we have said before it is in architecture that the work on housing morphology is richer, something that is comprehensible because of the familiarity of this specific field with the object of study: space. But since the majority of the typological studies developed in architecture are essentially centred in three criteria – stylistic, morphologic and functional - (Lawrence, 1994, p.272), they are often lacking in interpretation and are too descriptive. This comment does not suggest however that those studies are weak or even superficial: this strong descriptive component may b e developed as a crucial resource for diagnosis in order to solve some type of pathologies, to orient rehabilitation strategies or to define the guidelines of patrimonial classification. However, after reviewing the bibliography on the issue there is a strong desire of giving another type of interpretation to that huge amount of information. In this sense the challenge was to make an exploratory attempt of a connotative analysis of domestic space.

Methodological approach

There are some aspects that must be clarified. Some of them, while circumscribing the study’s universe, may constrain the analytical contents to some uniformity. First, we underline the adoption of three criteria intentionally restrictive: 1) a territorial one that leads us to circumscribe the research to the city of Lisbon; 2) the other is related to the type of building, being our option to focus only on collective housing, the dominant housing type in Lisbon, in contrast, for instance, with Porto where there is relevant tradition of individual housing; 3) finally, the research explores only the private sector, despites the importance of the public, not so much in quantitative terms, but more in qualitative terms; we can not understand the evolution of housing models in private sector, which is completely dominant in Portugal, if we do not look at the public, namely during the authoritarian regime – the actual matrix that stills characterizes the majority of housing models in Lisbon, the Modern one, appeared in the public sector. Secondly, we must call attention to our commitment to a diachronic perspective. This option, follows in a certain way the concept of sociogenesis developed by Norbert Elias, despite in this case we assume a much shorter period (see also Lawrence, 1987). Assuming time as a central variable in the modelling of any social phenomenon reduces the probability of developing two types of sociological ways of thought equally reductive and simplistic: essentialist ways of thought and another one that subscribes a sort of sociological big bang that simply ignores all the scientific patrimony produced until then. In fact, the thickness of social phenomena is only attained if it is thought as a process of long duration, which may do not have a linear or a monistic direction or even a cumulative one: by incorporating time in sociological research, there is more opening to understand the level of innovation of the studied object as well as the specificities and forms that it assumes on the present. In other words, only by incorporating time, the researcher is able to comprehend and systematize the real meanings of the logic of social change that affects society. Besides, with the progressive valuing of urban rehabilitation, the space of cities is cohabitated by buildings that were constructed in different epochs and that embody different symbolic universes.

In this paper we will just include the analysis of the housing types along the last three decades of the 20th century, despite the fact that the research focused on the entire century. For the period until the 60’s, which will not be analysed here, the central source of information was the typological works that were already developed in the field of Architecture. For this reason, the types that were analysed along that period are the ones that are already institutionalized in that field as some of the most emblematic types of the history of housing in the city of Lisbon, namely: the “gaioleiro” (until the 30’s), the “Estado Novo” (40’s) and the “Modern” (from the end of the 40’s to the 50’s). In the 60’s there is a hybrid type that mixes elements of the modern matrix, which appeared in the public sector, with elements of the “Estado Novo” type. Although this period is not developed in this paper, as well as public housing, they are presented in Figure 1 and resumed in the immediate brief telegraphic text.

Figure 1: Main housing types, private and public, along the 20th century. Source: Dismountable Houses: Arquivo Fotográfico Municipal de Lisboa; Economic Housing: Arquivo Fotográfico Municipal de Lisboa; Economic Rented Housing: author’s photo; Modern Grand Ensemble: author’s photo; The unique Residential Category: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 1997: 59; “Gaioleiro”: author’s photo; The “Estado Novo” Type: author’s photo; Transition to Modern: author’s photo; Actual Housing Types; advertisement published in Expresso; author’s Photo; advertisement published in Expresso.

PUBLIC SECTOR

i. ECONOMIC HOUSING: the reification of the regime ideology or the gift to the institutionalized

ii. DISMOUNTABLE HOUSES: residential environment as an instrument of indoctrination of the working class

iii. ECONOMIC RENTED HOUSING: the resignation to the collective housing solutions and the emergency of the technician modus operandi

iv. MODERN GRAND ENSEMBLE: “la machine à habiter” or the creation of the domestic conditions to the family democratization

v. THE UNIQUE RESIDENTIAL CATEGORY: housing as a right to the excluded

PRIVATE SECTOR

i. “GAIOLEIRO”: the emergency of the modern family

ii. THE “ESTADO NOVO” TYPE OR THE PRIVATE TYPE OF THE REGIME: the reification of the Portuguese heroic exploits

iii. TRANSITION TO MODERN or THE MIXED TYPE: towards family democratization, not yet social

iv. ACTUAL PRODUCTION: FAST DIFFERENTIATION OF THE WRAPPING versus SLOWLY TRANSFORMATION OF THE PITH

For the last decades – the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s – the principal source of information is real estate advertising: we have collected the totality of the advertisements that were published in the most important weekly newspaper of Portugal – Expresso – since its first edition in 1973 to 1999 (N= 539). In this period the connotative analysis is preceded by a previous systematization of the plans of the interior space of homes: the purpose of this process was to find regularities in morphological and compositional terms that would give some intelligibility, from a sociological approach, to the development of domestic spaces along the 20th century. An intelligibility that would expectedly reached through the recognition of different types of systems of domestic space.

Despite the multiple dimensions that incorporate our object, each of them with a peculiar relevance, for the present it will be privileged only one: the interior space of home through the analysis of its composition and configuration in order to understand the existence of different domestic spatial systems. It should be said that not all the advertisements have the plan of the home that is being commercialized, being the total number of plans analysed of 70 (N)2. To conclude this methodological note something more should be said in order to justify the exploratory character of the research. Though it is not crucial for this paper, the period until the decade of 1960 rose the scientific question of the representation of the studied types in relation to the housing universe of the related period; in fact, that representation is variable from case to case. As to the second period – the last three decades of the century – we believe that the exhaustive collection of the whole of the real estate advertisements, even if circumscribed to one single paper, has an unquestionable scientific value due to the present macro context of a market economy. In spite of this, we admit two possible fragilities in terms of representation: a first aspect that is related with the exclusion of the real estate promotions that were not advertised or with those advertisements that were not included in this newspaper. It seems, however, that this aspect looses some of its weight as long as the sector becomes fully integrated in the market since in this context advertising gains an enormous importance – the result is an explosion of the number of advertisements essentially by the end of the 80’s; the other aspect is related to the fact that the majority of those advertisements do not include the plans of the house something that reduces the representative potentialities particularly in terms of the research of the domestic spatial systems. Those two fragilities could only be solved if we were able to collect within the municipality the whole of the projects that were approved. But this would be a quite unrealistic task for several reasons, with the bureaucratic dimension being one of the most dissuading ones.

The relation between a dictatorial regime and housing

The contemporary history of Portugal should be understood in the context of Europe’s development during this period. In the beginning of the XX century the country experienced the end of the monarchy and the implementation of a Republic. Nevertheless, this first republican regime would be interrupted by a military coup d'etat in 1926 from which resulted an autocrat government led by Salazar. This autocratic regime was called “Estado Novo” or “New State” and it was essentially a conservative and nationalistic one, a regime in which the society was organized and controlled by the means of corporatism and ruled by the ideological trilogy: GOD3 - NATION - FAMILY. The regime would last for more then 40 years, until 1974 when a revolution led by the military put an end to it and began a democratization process. The stabilization of the democratic regime was reached by the middle of the 80’s and coincided with the national adhesion to the European Community (Cruz, 2000, p.123). This period gave a considerable impulse to the Portuguese modernization that had multiple effects from economy to society: we have assisted to a rapid change that promoted a sort of a direct passage from a pre-modern society to a Late Modern one, but with several contradictions related from the almost inexistent intermediate phase.

Nevertheless, within the long period of the dictatorial period (1926-1974) there are different moments in political and economical terms that have strong impacts on housing. There is a first period that corresponds to the consolidation of the political dictatorship that is reified by the correspondent Constitution promulgated in 1933. Until then there was no public intervention in housing. There is then a second moment that was marked by a strong intervention that was however almost centred in the city of Lisbon. In fact, Lisbon was hugely valued since it was considered the capital of the Portuguese Empire which was constituted by different colonies, being the most important the African ones such as Angola and Mozambique. This first wave of public intervention on housing had basically three purposes as if it was assumed the existence of three different “Portugals” thought in a hierarchical way: a) a minor Portugal, constituted by the excluded population and that was supposed to be domesticated and indoctrinated through the Dismountable Houses Program; b) a Contained Portugal, formed by those belonging to the corporations protected by the State and that deserve a sort of a prize of fidelity through the Economic Housing Program; c) an Imperial Portugal corresponding to the elites to whom was urgent to build a specific housing type (promoted by the private state but completely regulated by the public one) different from the quite promiscuous “gaioleiro” and that could materialize, both in morphological terms and in aesthetic ones, the superior side of the “Estado Novo” ideological program.

Only the two first programs were directly promoted by the state and both of them were inspired in the conservative housing solutions for the working class developed in the 19th century. By the end of the decade of 1940, there was a new shift within this public intervention as a result of the Second World War that increased the prices of the materials used in construction. This was essentially performed through the solutions aimed at that second Portugal, the one of the middle classes. In fact, if the Economic Housing Program presupposed an intervention centred in individual housing – the only solution at that time that enabled individuals to be owners of their houses –, the new reality proved the irrationality of that solution: an economically unsustainable solution. Therefore, the previous repudiated idea of collective housing becomes the most realistic option, something that would be materialized through the economic rented housing program.

That is precisely the moment when the domestic modern matrix comes into the public sector, something that begins a process of progressive generalization of its influence not only on public housing, but also on the private market. If in this first moment the entrance of the Modern Movement on public housing is essentially centred on the domestic structure and on the adoption of scientific methods of space programming in order to optimize or rationalize resources (from space in itself to materials), the decade of 60 reveals the assumption of it wholeness through a quite assumed adhesion to the Athens Charter spirit. But this shift within the principles of public housing programming is not meaningless. Indeed, it reveals the different phases of the autocracy. Therefore its major impact was reached in the first phase, 1933-1945, when the legal and institutional background of the social corporative regime was established (Cruz, 1988, p.41). During this period, residential space was in fact conceptualized as a material source, per excellence, to the reification of the ideological framework sought by the regime. The development of the economic rented housing program that began in the end of 1940th reveals the first signs of weakening of the ideological component of the regime as it begun to be slowly replaced by an emergent technical one (Baptista, 1996). By the 60´s, this approach is already dominant. The decade of 1960 has in itself the roots of the inevitable destruction of the regime, something that had very different expressions with distinct levels of visibility: from the more obvious student crises to the less understandable programming housing principles. In fact, as we are going to explain ahead, the modern matrix carries, under its expertness, a revolutionary purpose or a democratic one. Therefore, residential space was politically precursor through the implementation of a housing matrix that embodied democratization principles before the effective implementation of democracy that would only happen in 1974.

Under way to individualization

The results here presented are only related to the last three decades of the 20th century and to the private sector of real estate. Nevertheless, it is indispensable to refer to those two private types that have characterized the private sector along the first half of the century: the “gaioleiro” and the “Estado Novo” or the private type of the regime (see Figure 2). The “gaioleiro” is one of the most emblematic housing types until 1930 essentially aimed at the Bourgeoisie and can be resumed in the following terms:

Figure 2. Gaioleiro´s apartment layout. Source: Appleton, 2001, p.29.

1 This paper is an adaptation of a paper presented in the European Network for Housing Research International Conference/ ENHR of 2006, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

2 In some cases, there is even more than one plan. Although not very representative, those cases refer to two types of situations: a first one that is more common related to those advertisements that include several plans each of them corresponding to houses with different dimensions within the same building (1 room/ 2 rooms/ 3 rooms, etc.); the other situation, more unusual, when the builder or the marketing enterprise presents several plans referring to different buildings.

3 Catholic.

i. Distinction between the facade and the back: a) formal – noble materials used in facade/ worthless materials used in the back; b) functional – the facade is related to the extraordinary moments and the back is where occurs the daily family life; c) symbolic – the facade reifies the social aspirations of the family (the appearance) and the back represents its essence;

ii. Building/Housing structure conditioned by urbanistic and technical conditions: narrow and very profound;

iii. Division of the domestic interior space through gender and authority criterions: a) facade: 1º male space = bureau or boudoir, the compartment which is located nearby the house entrance and has a door that confers the “head of the family” the required autonomy; 2º family representational space = sitting-room, a room forbidden to children and reserved to visits; it functioned to reify the social statute attained or projected by the family; 3º female space = toillete (ipsis verbis), a space deserved for the woman of the high bourgeoisie whose way of life was defined by reference to the French society, where female appearance cult was a major value; b) back: kitchen – female space; dinning room – family informal space

iv. Undervaluation of the private sector (bedrooms) with its location between those two zones, something that shows the relative small importance of the individual within the Bourgeoisie family of the beginning of the 20th century.

The “Estado Novo” type (see Figure 3) or the private type of the regime defines a Portuguese Distinct Style inspired in the architecture of the magnificent periods of the Portuguese history. Besides, it performs the restructuring of the interior space through a partial importation of the principles of modern architecture with a triple purpose:

Figure 3. Estado Novo’s apartment layout. Source: Pereira, 2011, p.28.

i. Create the conditions for the institutionalization of nuclear family, something that presupposes its self enclosure. By institutionalization we refer to that family model conceptualized by Burguess and Locke in 1945 and defined by “the hierarchical relations between partners, the submission of individual to group's interests, differentiation of roles between genders, a tepid affectivity4” (Roussel, 1992, p.90).

ii. Create the conditions for women’s domestication. By this we refer to the regime intention to attach women to domestic space in order to create the material conditions to its feminine ideal characterized by this triple function: spouse, mother and housewife.

iii. Formalize and clarify the inner social hierarchies, something that did not exist within the previous model where it was visible some sort of promiscuity between the family and its servants.

Thus, for the fulfilment of this triple purpose the “Estado Novo” type will import from the Modern Matrix two fundamental aspects: a) the introduction of nodal elements which make the transition between the public and the private (the entrance hall and other vestibules); b) the rationalistic logic of domestic space that organizes it in three main sectors, the social, the services (kitchen and relative spaces) and the private which congregates the bedrooms and the bathrooms that become more segregated in relation to the entry (Amorim, 1997). But the simplifying rationale that defines the modern matrix is at this juncture voluntarily ignored since it would completely deny that same triple purpose. Accordingly, if the clear separation of those three sectors endorses the privatization of the familiar life, the development of a quite complex sector of the services – with the introduction for instance of the maid bedroom and bathroom that did not exist before that, besides having an exclusive passage from the kitchen, was located in the most segregated space of this particular sector – materializes all at once the reinforcement of the inner social hierarchies and the space conditions that enables women to be professionals of the home. On the other hand, it reproduces the same complexity that characterized the social sector of the previous models with its partition in three spaces: a more masculine room (the office located nearby the entry), a more formal and representational one (the living-room in between these two) and a more cosy and private space aimed at the current life family (the dinning-room located at the most extreme point of it in relation to the entry).

After this parenthesis, we are able to present our results in a more consistent way. Following our methodological procedures that pointed to a previous systematization of the 70 domestic plans included in the “Expresso” advertisements collected from 1973 to 1999, we reached a typology of systems of domestic spaces composed by 6 types. Then, we categorized each plan of our sample according to that typology and after this we developed its statistical treatment. The typological criteria adopted for the construction of each system of domestic space is the definition of different logics used in the structuring of the sectors, both isolated and on the whole of the system: social, services and private. Our point of depart is the pure modern matrix type, type 1. This type appeared in Portugal by the end of the 40’s in the public sector. The international Modern Movement within architecture had a double purpose: on the one hand, a social project that would be able to materialize the ideals of Modernity through space, ideals such as emancipation, democratization and rationalization; on the other hand, a field project aimed to the reinforcement of the position of Architecture in a society progressively specialized in scientific and technical ways (Pereira, 2004). Indeed, the content of that social project reveals a specific spatial domestic system that points to a passage from the “institution family” to the “companion family”, both conceptualized by Burguess e Locke. Roussel in an attempt to “solve the excessively dichotomised character of those two models, extended the spectrum of these normative models, by introducing four models: on the most traditionalistic side, we could find the “institution family” and the “alliance family”; on the most modernist side, we could find the “fusion family” and the “association family” or “club family”” (Aboim, 2006, p.172).