Representações espaciais pelo uso na moradia tradicional amazônica

Izabel Cristina Melo de Oliveira Nascimento é arquiteta e urbanista, mestre em Design e doutoranda em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Desenvolve sua pesquisa na Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), onde estuda processo projetual, projeto participativo e habitação. izabel.nas13@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/2785790175730151

Ana Kláudia de Almeida Viana Perdigão é arquiteta e urbanista e doutora em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. É Professora Associada IV da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA). Coordena o Laboratório Espaço e Desenvolvimento Humano (LEDH) e estuda processo projetual e habitat amazônico. klaudiaufpa@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/9009878908080486

Como citar esse texto: NASCIMENTO, I. C. M.O.; PERDIGAO, A. K. A. V. Representações espaciais pelo uso na moradia tradicional amazônica. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 22, Semestre 1, julho, 2021. [online] Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus22/?sec=4&item=13&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 13 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO SUBMETIDO EM 7 DE MARÇO DE 2021

Resumo

O artigo apresenta a análise das relações espaciais em moradias tradicionais palafíticas amazônicas, nos estados do Pará e do Maranhão, apoiando-se nos padrões sistematizados por Christopher Alexander em moradias latino-americanas no Peru. Foi realizada uma pesquisa qualitativa com a técnica de observação sistemática. As semelhanças de representação espacial pelo uso do ambiente construído são identificadas nas moradias analisadas, permitindo evidências do homogêneo e do único de cada lugar na configuração dos espaços e de suas representações. Os aspectos identificados têm potencial para instrumentalização de práticas projetuais, considerando que as soluções identificadas se mostraram como aspectos de habitações latino-americanas, de modo geral. Elas ilustram também o modo particular com que o amazônida produz, usa e se relaciona espacialmente com a sua moradia, um conhecimento de grande pertinência para o campo da arquitetura, considerando que a pluralidade de representações espaciais latino-americanas demanda atenção às informações referentes às práticas locais. Considerar a territorialização dos estudos sobre as moradias na América Latina evidencia o reconhecimento da existência de traços nativos que carregam conteúdos projetuais que contrariam o pensamento arquitetônico hegemônico.

Palavras-chave: Comunidades tradicionais, Palafita, Representações espaciais, Amazônia

1 Introdução

Os processos e operações projetuais compreendem um campo de conhecimento ainda pouco explorado na formação em arquitetura, se comparados com os métodos predominantes no ensino de projeto em escolas brasileiras. Interpretá-los na complexidade e na dinâmica do quotidiano é uma prática pouco recorrente. Assim sendo, a compreensão teórica de práticas projetuais envolvendo materialidade e imaterialidade da arquitetura torna o projeto um objeto de investigação epistemológica. Segundo Malard (2006), o projeto é determinado pela cultura, pelo modo de vida das pessoas e pelo seu entorno, ou seja, é específico para cada cultura e congruente com a organização social daquele grupo. Ele depende do conhecimento e da reflexão sobre as necessidades espaciais do morador e o contexto de inserção da cultura na paisagem natural e construída.

Essas necessidades espaciais relacionam-se com características físicas da edificação, com o modo como os moradores compreendem os espaços da casa e com o contexto social e cultural de uso dessa arquitetura, representado nos ambientes. Essa representação espacial, na perspectiva de Perdigão e Bruna (2009), é um princípio norteador do processo de projeto de interpretação do ambiente arquitetônico pela vivência. O habitat palafítico amazônico, no contexto das comunidades tradicionais, mostra-se como uma realidade empírica valiosa para decifrar os mecanismos utilizados para a produção do ambiente construído sem arquitetos. A observação e o levantamento de ações in loco, especialmente sobre as transformações e adaptações realizadas pelo morador, contribuem com estratégias, sem subestimar a complexidade envolvida, para a produção de conhecimento formal no campo da arquitetura direcionado à formação do arquiteto e de sua atuação.

Essa atuação profissional se faz com conhecimentos técnicos e teóricos sistematizados que compreendem a relevância de se incorporar ao processo variáveis de natureza espacial, bem como sociocultural (DEL RIO, 1998), o que leva a uma postura autorreflexiva do profissional em torno de suas decisões (OLIVEIRA, 2010). A necessidade de comprometimento do projetista com a adequabilidade da arquitetura ao espaço vivencial estabelecido pelo usuário se aplica também na Amazônia. O modo como o morador da Amazônia se relaciona com a natureza influencia no modo como ele se relaciona com a sua própria moradia. Cabe ao profissional compreender as representações espaciais estabelecidas por ele no processo de vivência e identificar os elementos peculiares do uso espacial nesse quotidiano como sendo orientações ao processo de projeto da moradia tradicional de um lugar.

A descrição sobre o modo como o habitante tradicional da Amazônia entende e produz os espaços da moradia, motivada pelo uso, é o componente norteador desta investigação. Considerou-se, para isso, a produção da moradia tradicional palafítica no bioma Amazônia, na área delimitada como Amazônia Legal brasileira, em comunidades tradicionais dos estados do Pará e do Maranhão, em uma região historicamente e culturalmente reconhecida pela existência de moradias em palafitas. Este estudo caracteriza-se como uma pesquisa qualitativa, com técnica de observação sistemática, em que os aspectos identificados se orientaram a partir de padrões de uso sistematizados por Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969). Buscou-se identificar como esses padrões se manifestam e se aplicam ao modo tradicional de morar na Amazônia, considerando o que seria homogêneo e o que seria único como resultado da investigação, ampliando o entendimento sobre o viver e morar latino-americanos. Isso evidencia as variáveis projetuais homogêneas em relação às casas na América Latina, mas também destaca o modo peculiar como elas se manifestam, a depender do contexto cultural, social e natural de inserção.

2 A tradição do morar palafítico amazônico

A Amazônia é um território com manifestações variadas de um “sistema socioecológico complexo” (DE LAS CASAS, 2019, p. 156, tradução nossa). Com extensão em nove países da América Latina, ações nesse território afetam todos os países que a constituem, bem como demais vizinhos latino-americanos (ARAGÓN, 2018), justificando a importância de conhecimentos sobre ela. Contudo, essa região só pode ser compreendida a partir da integração entre os conhecimentos sobre o ser humano que a habita, a natureza que o circunda e o esclarecimento da relação harmônica já estabelecida entre os dois elementos (PAES LOUREIRO, 2015). Essa articulação da vida humana em harmonia com a natureza do entorno reflete-se no uso dos recursos naturais, respeitando a sazonalidade da natureza (STOLL et al., 2019), práticas apreendidas no quotidiano e características de atividades econômicas familiares fundamentadas em um saber social (LOUREIRO, 1992).

Para De Las Casas (2019, p. 156), “[...] o Bioma Amazônia é um dos principais componentes do sistema socioecológico que é a Amazônia, entendida como unidade de análise e gestão”. Em seu trabalho, ele destaca a importância da Amazônia no cenário mundial e a necessária integração entre ações políticas voltadas a esse território. O bioma Amazônia possui um sistema socioecológico complexo, exigindo abordagens que considerem as paisagens culturais e o papel transformador da cultura dos homens e mulheres da floresta. Em escala global, esse bioma está presente na Guiana Francesa, no Suriname, na Guiana, na Venezuela, na Colômbia, no Equador, no Peru, na Bolívia e no Brasil (DE LAS CASAS, 2019). Nesse último, compreende a maior extensão do que se denominou de Amazônia Legal brasileira (Figura 1), abrangendo todo o território dos estados do Acre, Amazonas, Roraima, Amapá e Pará, uma grande parte do estado de Rondônia e presente, em menores extensões, nos estados do Maranhão, Tocantins e Mato Grosso (Figura 1).

Fig. 1: Bioma Amazônia e Amazônia Legal brasileira. Fonte: VELOSO, 2020. Elaboração: Francisco George Lopes/Secom UnB, modificado pelas autoras, 2021.

Em virtude das mudanças ocorridas desde a Revolução Industrial, faz-se relevante uma abordagem amazônica com enfoque humano, devido à necessária elucidação, registro e inserção no campo científico de fatores intrínsecos às atividades humanas que estruturaram a cultura tradicional da moradia amazônida. Como tradicionais, caracterizam-se as comunidades formadas por pessoas que compartilham crenças ancestrais e um modo de viver comum, mantidas pelo conhecimento herdado e pelo modo como habitam o território (LIFSCHITZ, 2011). No bioma Amazônia, dentre outras comunidades tradicionais, estão presentes aquelas estabelecidas por palafitas, possuindo uma tradição que se manteve isolada de influência de outros lugares do Brasil e da América Latina, estabelecendo um modo de habitar peculiar e diferenciado (PAES LOUREIRO, 2015). As casas são produzidas com conhecimentos herdados acerca dos fluxos das águas, estabelecendo sua tradição na relação quotidiana com a casa e o entorno natural, configurando o que Menezes (2015, p. 108) identificou como “tipo palafita amazônico”.

Esse modo de morar sobre as águas existe desde o período pré-colonial, chamado, nesse período, de estearias, por serem casas suspensas por troncos de árvores, ou seja, por esteios (NAVARRO, 2017). Segundo o autor, a escolha pela moradia sobre as águas se deu, naquele tempo, tanto por motivos culturais como de proteção, frente à possibilidade de ataques inimigos. Estudos arqueológicos sobre assentamentos palafíticos na Amazônia oriental identificaram um maior número de estearias no litoral paraense, próximas à Ilha de Marajó (PA), e no litoral maranhense, na região do rio Turiaçu (NAVARRO, 2018). Por essa razão, considerou-se relevante que o estudo sobre a moradia tradicional palafítica amazônica fosse realizado nessas localidades, especificamente na faixa costeira em que estão a Ilha de Marajó e a foz do rio Turiaçu.

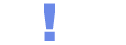

No Pará, a moradia amazônica tradicional se estabeleceu na estreita relação do “homem natural da Amazônia” (LOUREIRO, 1992, p. 16) com os rios, de modo a apresentar uma ocupação do território que acompanha o curso das águas (TRINDADE JR., 2012), caracterizando o modo de morar ribeirinho da Amazônia. Cruz (2008) considera esse modo de morar como sendo o mais típico das populações amazônicas e da cultura regional, que tem o rio como importante denominador das escolhas que as pessoas fazem sobre sua própria moradia e seu modo de viver. Suas edificações são feitas com madeiras da região e, em respeito à variação do nível das águas dos rios, são construídas sobre palafitas (Figura 2).

No Maranhão, a relação entre a moradia e o entorno natural amazônico é distinta daquela observada no Pará, pois não se dá à margem dos rios, mas afastando-se dela. O quotidiano da casa se relaciona com um entorno que é alagado em apenas alguns períodos do ano, em uma parte do bioma Amazônia com ecossistema de terra firme. Mesmo assim, os moradores produzem as casas em palafitas, respeitando o avanço das águas, mas sem acesso por estivas (Figura 3). Essa realidade evidencia um contexto plural e diverso, com particularidades espaciais e territoriais demarcadas pelas vivências quotidianas (TRINDADE JR., 2012). Segundo Castro (2019), a Amazônia apresenta ecossistemas de várzea, manguezais ou de terra firme, o que demanda a compreensão do quotidiano dos rios, lagos, igarapés, igapós e marés que os compõem.

A valorização dos aspectos de um lugar é uma prática importante no processo de projeto. Menezes (2015) expõe o processo de adaptação habitacional de moradores remanejados para o Projeto Vila da Barca, em Belém, Pará. Originários de uma comunidade ribeirinha, eles realizaram modificações na casa recebida em um “resgate ao tipo palafita amazônico” (MENEZES, 2015, p. 108). Outro exemplo é o projeto Taboquinha (PAIXÃO, 2019), distrito de Icoaraci, em Belém, já que a adaptação habitacional levou ao resgate físico e de relações espaciais da “casa de origem”. Evidenciando a relação entre teoria e prática na atuação profissional, o que valoriza aspectos socioculturais, Perdigão (2003) apresenta uma “proposta arquitetônica flexível” aplicada a um processo de remanejamento que valorizou a “despadronização tipológica”, proporcionando identificação das pessoas com a nova moradia. Perdigão (2019) destaca o potencial de informações do morar amazônico na formulação de teorias da produção arquitetônica, pois as características do modo de habitar local e da vivência espacial são informações pertinentes ao processo de projeto com respeito ao lugar.

3 Categorias de análise das representações espaciais pelo uso da moradia

A área compreendida pelo bioma Amazônia se estende por nove países da América Latina. Contudo, o presente estudo sobre o morar tem seu recorte na região da Amazônia Legal brasileira, mais especificamente, em comunidades insulares costeiras dos estados do Pará e do Maranhão. Pretendeu-se evidenciar soluções que refletem o modo como as pessoas se relacionam com a sua moradia, interpretando as representações espaciais estabelecidas pelos usuários de cada lugar no uso quotidiano da moradia tradicional palafítica amazônica. Para sua realização, assumiu-se a utilização de pesquisa qualitativa coletando, conforme Groat e Wang (2013), dados do contexto natural observado, já que, na sequência, o pesquisador interpreta esses dados. A técnica utilizada em campo foi a observação sistemática (GIL, 2008), pois os aspectos observados foram previamente estabelecidos e fundamentados com base no objetivo da pesquisa.

Para fundamentação dos aspectos observados e das categorias de análise aplicadas, foram considerados os estudos e sistematizações realizadas por Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969), Alexander, Ishikawa e Silverstein (1977) e Alexander (2002). Esses autores relataram representações em edifícios e sistematizaram elementos que são a essência de “vida” desses lugares. Para eles, essa “vida” é o atributo de identificação da qualidade em uma edificação. Contudo, ela só é gerada nas ações das pessoas no espaço. Alexander, Ishikawa, Silverstein (1977) demonstraram atenção especial à arquitetura tradicional por compreenderem a aptidão das pessoas em suprir suas próprias necessidades espaciais. Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin, Angel (1969) destacam a importância de se valorizar os aspectos identitários de um lugar, a exemplo das suas proposições considerando o modo de morar em Lima, no Peru. Na proposta e execução do seu Proyecto Experimental de Vivienda, foram preservadas o que eles chamaram de “idiossincráticas necessidades individuais das famílias que compraram as casas” (ALEXANDER et al., 1969, p. 6, tradução nossa).

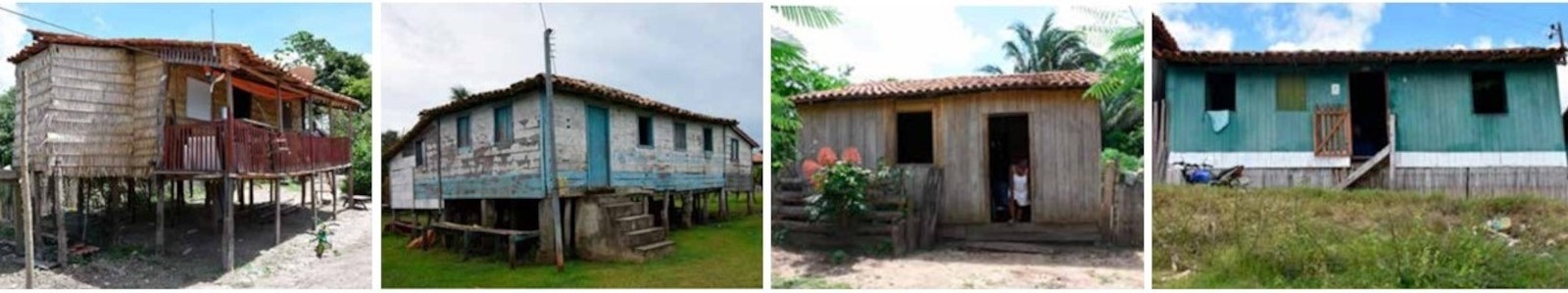

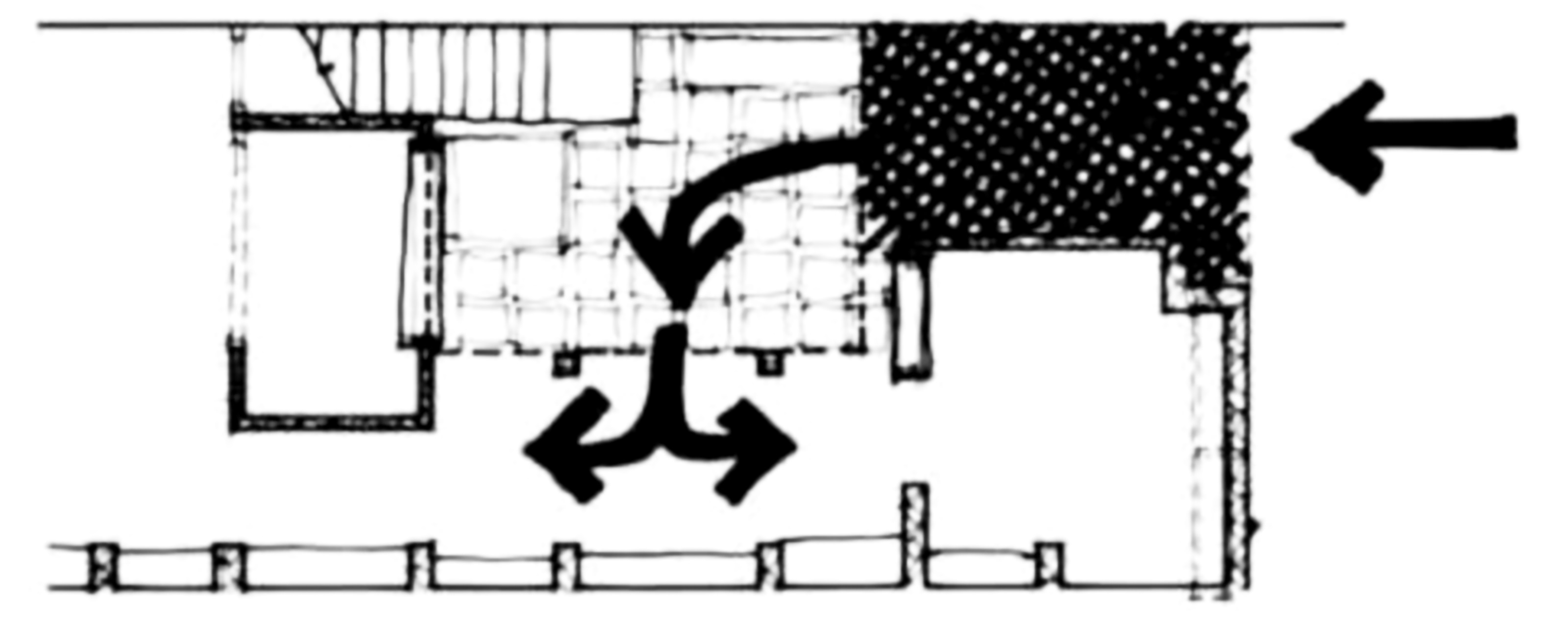

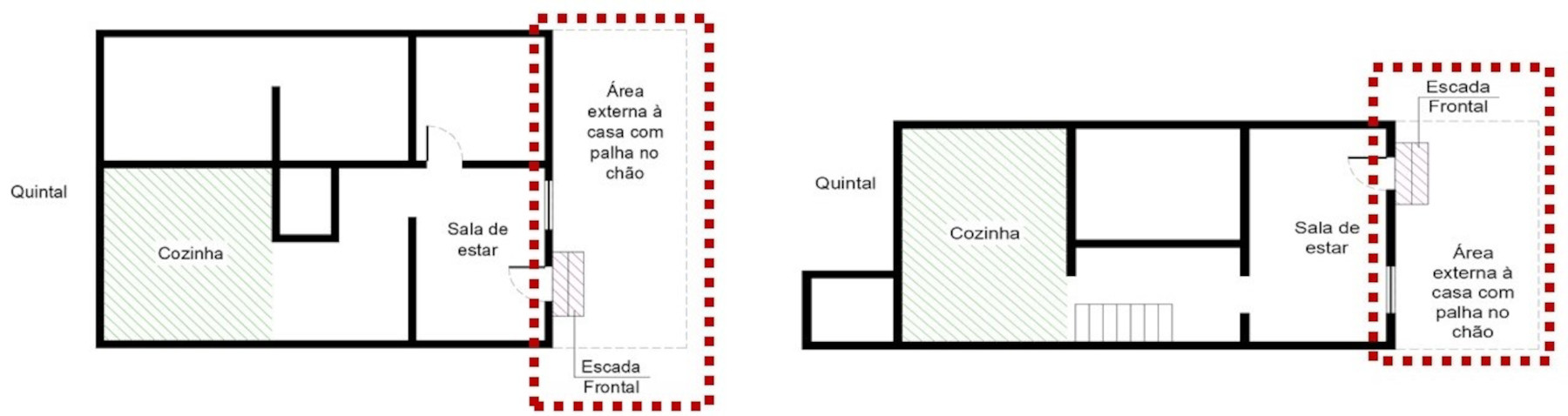

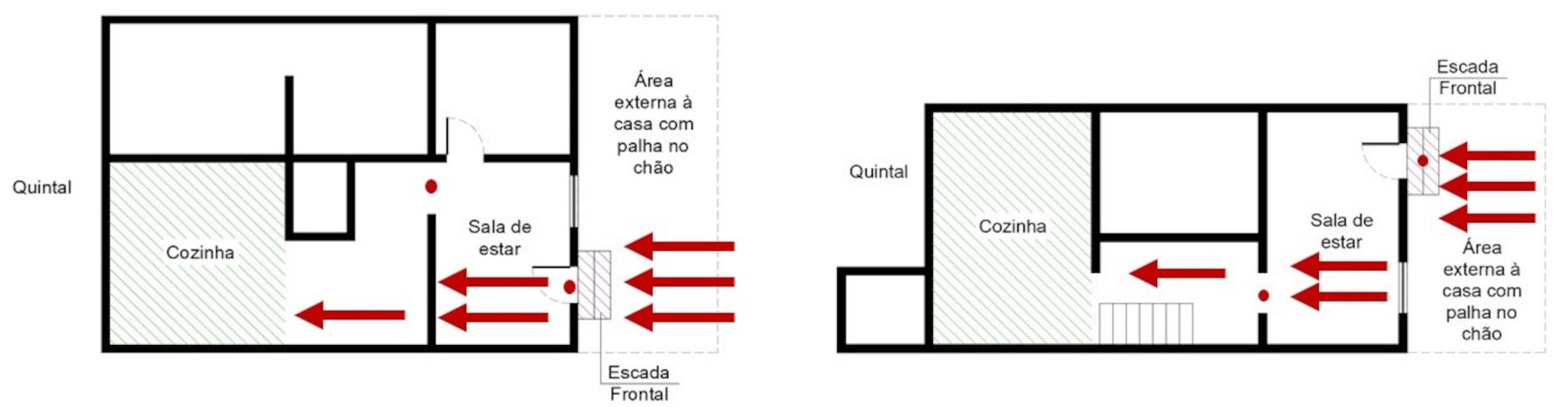

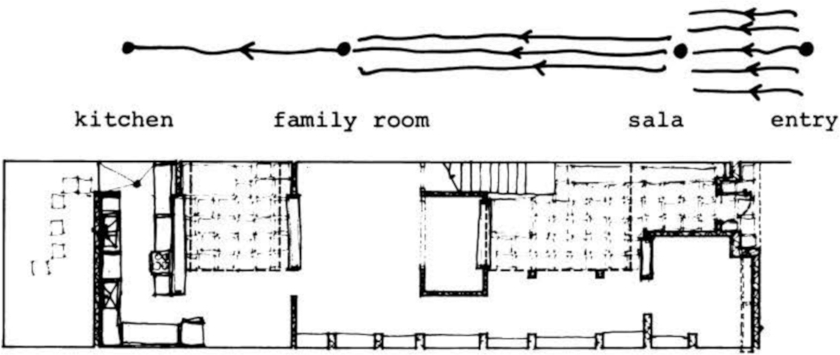

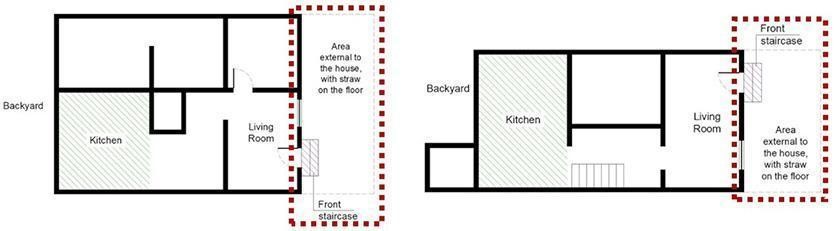

Os autores identificaram que a dinâmica de uso dos espaços possuía um padrão de linguagem proveniente de ações repetidas ocorridas no quotidiano daquele lugar (ALEXANDER et al., 1969 e ALEXANDER et al., 1977). Eles as sistematizaram como instruções prévias àquelas espacialidades, considerando seu aperfeiçoamento quando aplicadas a outros contextos. Anos depois, Alexander (2002) publicou quinze propriedades fundamentais a serem consideradas para se alcançar a “vida” em estruturas projetadas. Nessa ocasião, relacionou a elas os padrões de linguagem, como “notas funcionais” aplicáveis ao processo de projeto. Dentre aquelas identificadas pelo autor, utilizou-se, neste artigo, a propriedade Gradiente. Para ele, ela evidencia uma resposta natural às situações de mudança em um espaço, adaptando-se a elas. Os padrões selecionados como categorias de análise, e que estão relacionados a essa propriedade, foram o “espaço de transição” (Figura 4) e a “gradiente de intimidade” (Figura 5).

Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969) descreveram como recorrente, em moradias de países da América Latina, um gradiente de intimidade iniciado nos cômodos menos privativos, à frente da casa, até os mais íntimos, ao fundo (Figura 5). Para os autores, é essencial para essas casas a existência de um ambiente logo após a entrada, já que as pessoas estabelecem variados níveis de proximidade entre elas, desde conhecidos casuais que sequer entram na casa, até os mais próximos, recebidos na cozinha. O aspecto relacionado ao espaço de transição entre a rua e o ambiente interno da moradia foi descrito por Alexander e seus colegas (1969) como um padrão aplicável a qualquer casa, podendo se apresentar de várias formas: mudanças em elementos como a vista, luz, nível, superfície, som, escala, ou qualquer ação que interrompa uma continuidade. Estabelecem-se, assim, aspectos a serem observados em campo quanto ao fato de o gradiente de intimidade indicar ambientes menos privativos na frente da casa e de maior privacidade ao fundo, e quanto ao espaço de transição, observando a forma como ele ocorre nas comunidades estudadas. Esses elementos auxiliam na compreensão das características de diferentes lugares, registrando relações espaciais produzidas na vivência.

4 O uso da moradia tradicional palafítica amazônica

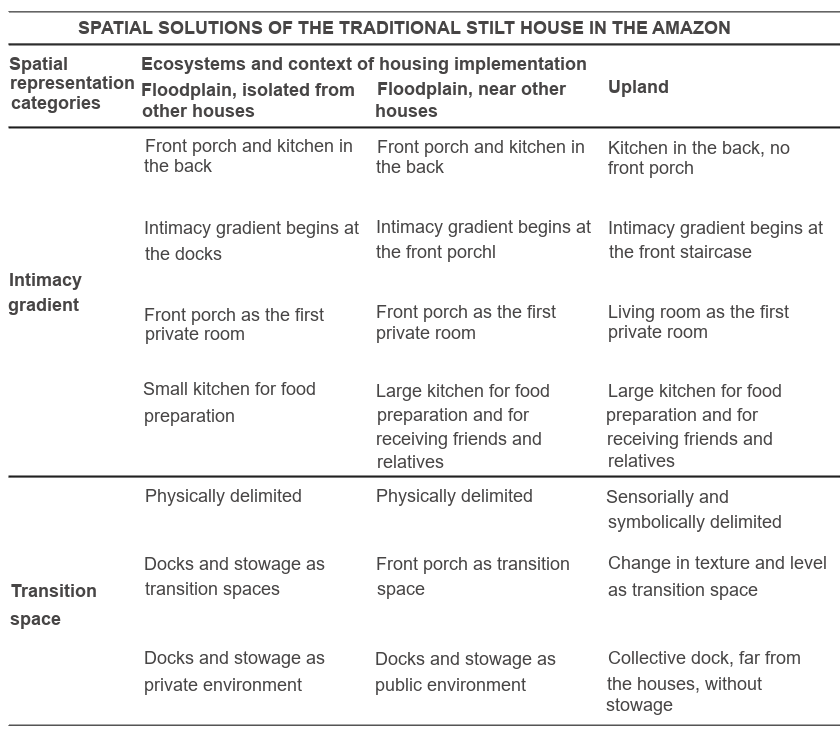

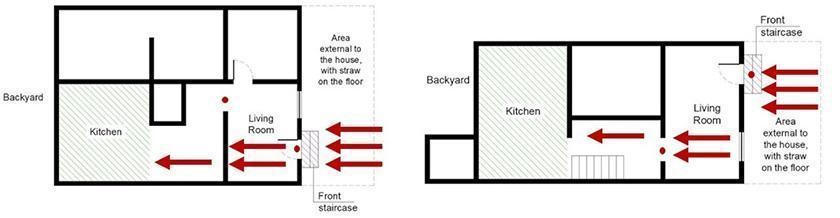

Neste item, aborda-se o contexto de uso da moradia tradicional palafítica no bioma Amazônia, com a atenção voltada à identificação de soluções espaciais em dois ecossistemas distintos: várzea e terra firme. Compreender as representações espaciais estabelecidas pelos moradores contribui para destacar soluções aplicáveis ao processo de projeto voltado ao lugar, evidenciando o modo como eles compreendem e se relacionam com a casa. Estabeleceram-se como categorias de análise da representação espacial os padrões “espaço de transição” e “gradiente de intimidade” (ALEXANDER et al., 1969 e ALEXANDER et al., 1977). O estudo contribui para o registro de elementos homogêneos e peculiares à cultura de uso da moradia de cada lugar, conforme sintetizado no Quadro 1, e detalhado nos subitens seguintes.

Quadro 1: Soluções espaciais da moradia tradicional palafítica na Amazônia. Fonte: As autoras, 2021.

4.1 Representação espacial pelo uso em moradias tradicionais no Pará

A moradia palafítica tradicional na Amazônia paraense está representada, neste estudo, por casas localizadas na Ilha das Onças, Pará, nas proximidades da Ilha de Marajó, em um habitat relacionado com o que Cruz (2008, p. 56) chamou de “cultura ribeirinha”. Suas construções se dão às margens dos rios, os moradores constroem as edificações e caminhos (estivas) em madeira e o quotidiano obedece à sazonalidade das águas do entorno. Com as cheias e vazantes dos rios, esse modo de morar se viabiliza em edificações em palafitas, em ecossistema de várzea, em áreas alagáveis em boa parte do ano. A casa 1 (Figura 6), segundo Virgílio e Perdigão (2020), foi construída por pessoas oriundas da cidade de Belém, habituadas, na infância, à vida ribeirinha, o que influenciou sua decisão de sair da cidade e auxiliou a escolha do local da moradia. Por outro lado, os moradores da casa 2 (Figura 6) ocupam uma casa que pertencia anteriormente à sua mãe. Em seu entorno, há moradias próximas, interligadas por estivas, prática comum em áreas onde os vizinhos são da mesma família.

Fig. 6: Moradias em palafitas (Casa 1 à esquerda e Casa 2 à direita), Ilha das Onças, Pará. Fonte: Acervo do Laboratório Espaço e Desenvolvimento Humano (LEDH), 2019.

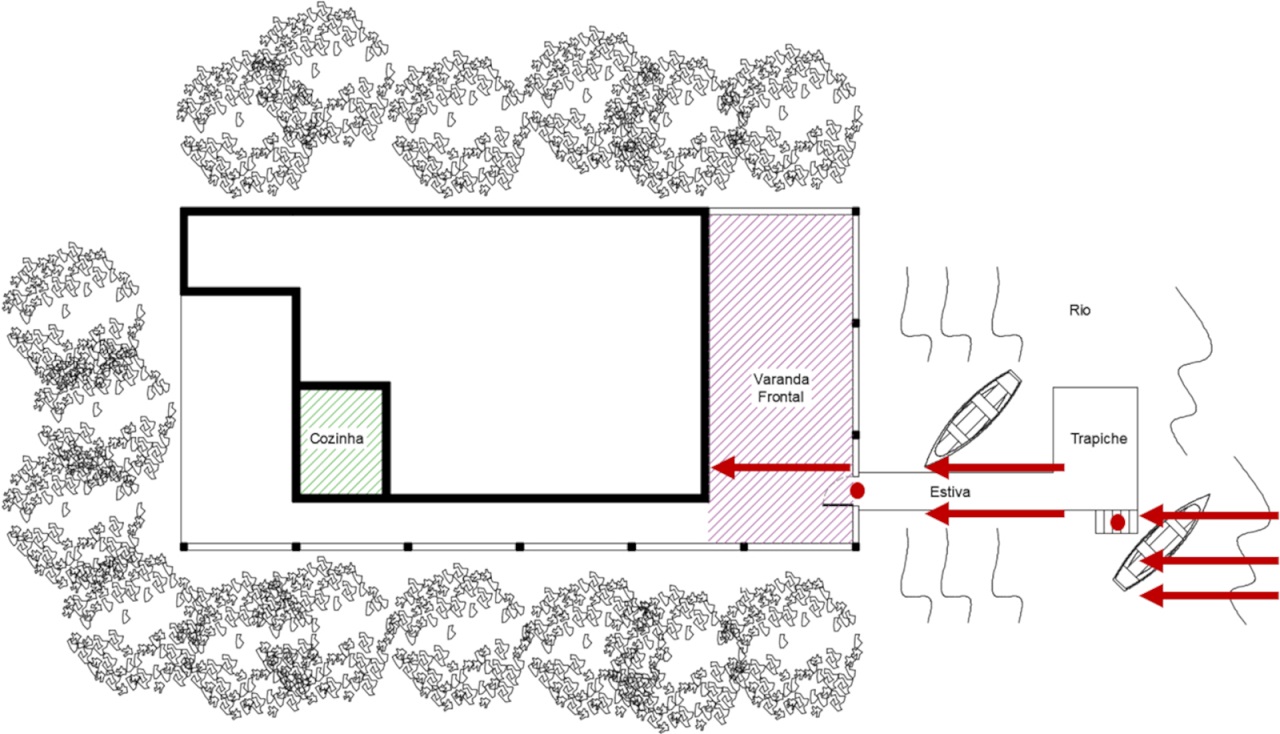

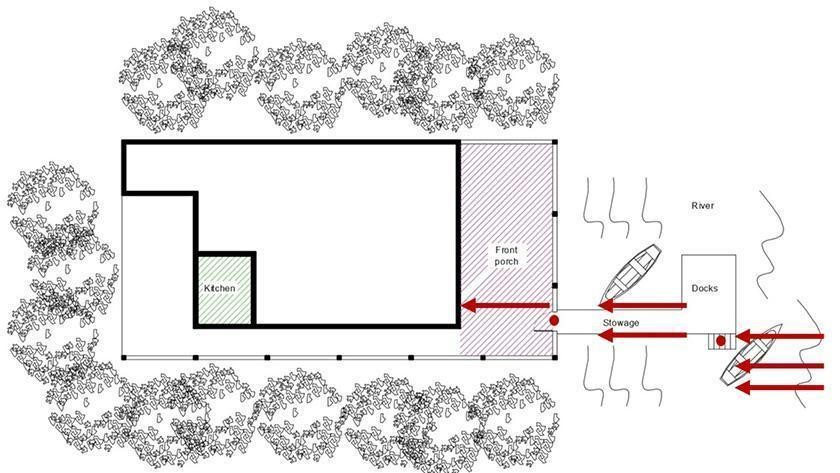

Quanto ao uso da casa 1, Virgílio e Perdigão (2020) relataram que a varanda e a cozinha são os ambientes mais usados pelos moradores. Analisando a figura 7, observou-se a opção pela construção de uma varanda frontal e de uma cozinha ao fundo. Apesar de Alexander, Ishikawa e Silverstein (1977, p. 610, tradução nossa) considerarem a “varanda frontal ou a sala de entrada” como os ambientes “mais públicos de todos”, nesse caso, por se tratar de uma moradia isolada, a estiva dá acesso à casa apenas para quem chega de barco pela parte da frente, e o gradiente de intimidade inicia-se no trapiche e estiva, para somente depois adentrar a varanda frontal, onde se recebem as visitas. Por esse motivo, a cozinha se apresenta como um ambiente pequeno, voltado às atividades de preparo da comida, e o gradiente de intimidade permite a utilização da varanda frontal de forma privativa.

Quanto ao espaço de transição, segundo Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969) e Alexander, Ishikawa e Silverstein (1977), seu estabelecimento é o que garante a chegada menos abrupta ao interior da casa. Essa demarcação, física ou simbólica, está relacionada ao percurso entre o que se considera público e o que é considerado privado. No caso da vida ribeirinha, de modo geral, as pessoas têm com o rio relação semelhante àquela que os moradores em terra firme têm com a rua. Nele, os moradores se deslocam para a realização de suas atividades e para chegar à casa dos vizinhos. Desse modo, na casa 1, o trapiche e a estiva frontais são os seus espaços de transição (Figura 8), uma vez que todo visitante precisa chegar até ela de barco, por encontrar-se isolada em relação às demais casas da comunidade.

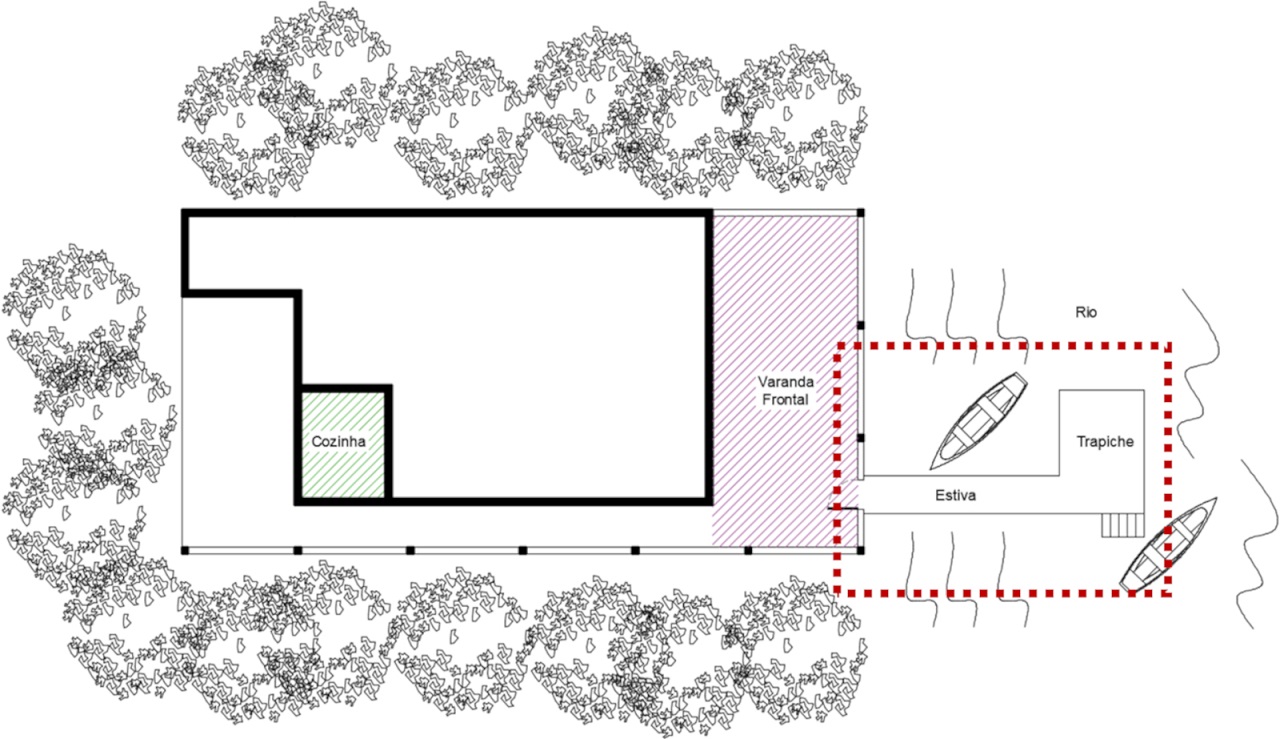

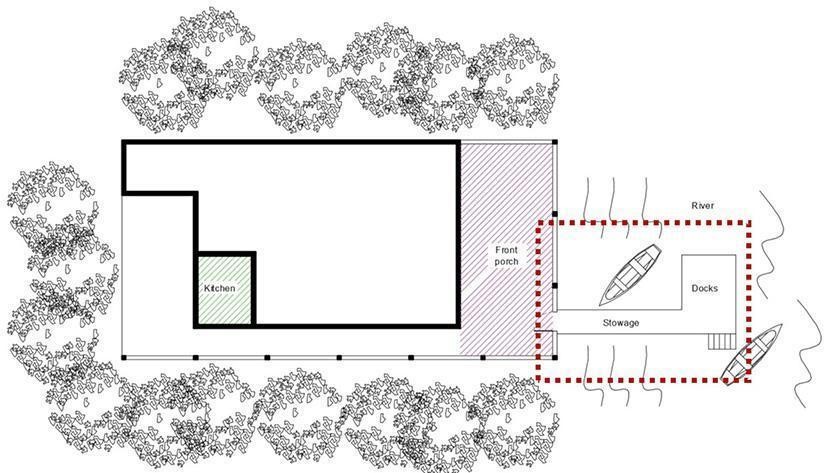

Quanto à casa 2, por estar em um contexto de proximidade com outras casas, já que os vizinhos eram da mesma família, ela possui acessos por estivas que interligavam as habitações. Nesse contexto, a decisão do morador sobre o controle da privacidade, ao invés de se dar na estiva, inicia-se nas portas de acesso à casa, a exemplo da porta da varanda frontal. Desse modo, a varanda se configura como o ambiente mais público da edificação e as pessoas mais íntimas à família são recebidas na cozinha, que fica ao fundo (Figura 9). Essa configuração assemelha-se àquela apresentada por Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969) em relação às casas no Peru, pois é delimitado um ambiente frontal para receber visitantes mais formais e, gradativamente, esse controle de privacidade diminui até a área mais íntima da casa. Por ser um ambiente que se destina ao preparo de comida e ao recebimento de familiares e amigos, o ambiente da cozinha é maior do que na casa 1.

Por se tratar de uma casa acessada pela estiva frontal e por outras estivas interligando edificações vizinhas, a casa 2 tem como espaço de transição a varanda frontal. Diferentemente da casa 1, isolada, essa proximidade entre casas estabelece caminhos públicos por meio das estivas, e o espaço de transição acontece em um ambiente interno da casa. Essa configuração também se assemelha ao modelo de casa peruana apresentada por Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin e Angel (1969), em que há uma delimitação de ambiente frontal para essa transição. No caso da moradia ribeirinha, esse ambiente é a varanda frontal (Figura 10). Ela cumpre o papel de transição gradativa de saída do ambiente externo e uso do interior da casa.

Em relação às necessidades espaciais humanas da moradia palafítica tradicional no Pará, perceberam-se dois contextos distintos de implantação da edificação. O primeiro, casa 1, isolada em relação às outras casas e um segundo, casa 2, em uma rede de habitações de pessoas da mesma família. Nos dois casos, observou-se o mesmo posicionamento de ambientes, varanda frontal e cozinha ao fundo, em relação ao conjunto da edificação. Contudo, a moradia isolada estabelece um gradiente de intimidade que se inicia externamente à edificação, na estiva e trapiche, enquanto a moradia próxima a vizinhos tem seu gradiente iniciado na varanda frontal. Essa caracterização influencia a configuração da cozinha que, no primeiro caso, é pequena e se destina apenas ao preparo de alimentos, e, no segundo caso, com a varanda frontal utilizada no controle de privacidade, configura-se de modo a receber visitantes e familiares.

4.2 Representação espacial pelo uso em moradias tradicionais no Maranhão

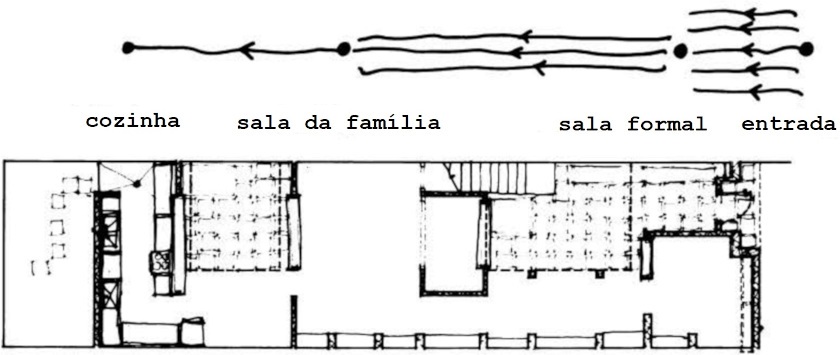

Na moradia palafítica tradicional na Amazônia maranhense, transparece uma relação mais estreita com a terra. Elas estão afastadas das margens fluviais, adentrando o terreno em busca de terra firme, mantendo a relação com o rio na construção de um único trapiche (Figura 11), de uso coletivo, afastado das casas. Percebe-se um conhecimento sobre a sazonalidade da natureza do entorno, pois os habitantes constroem suas casas suspensas do solo, a uma altura que atende aos períodos de alagamentos sem que as águas as invadam. Contudo, por possuírem períodos longos de estiagem e terra seca, eles não constroem caminhos em estivas e utilizam a própria terra para acesso às edificações. Essas comunidades são constituídas por moradias em palafitas tradicionalmente implantadas em terra firme, e que convivem com períodos mais curtos de áreas alagadas.

Fig. 11: Moradias em palafitas e trapiche de acesso ao rio, Ilha de Sababa, Maranhão. Fonte: Acervo do Laboratório Espaço e Desenvolvimento Humano (LEDH), 2020.

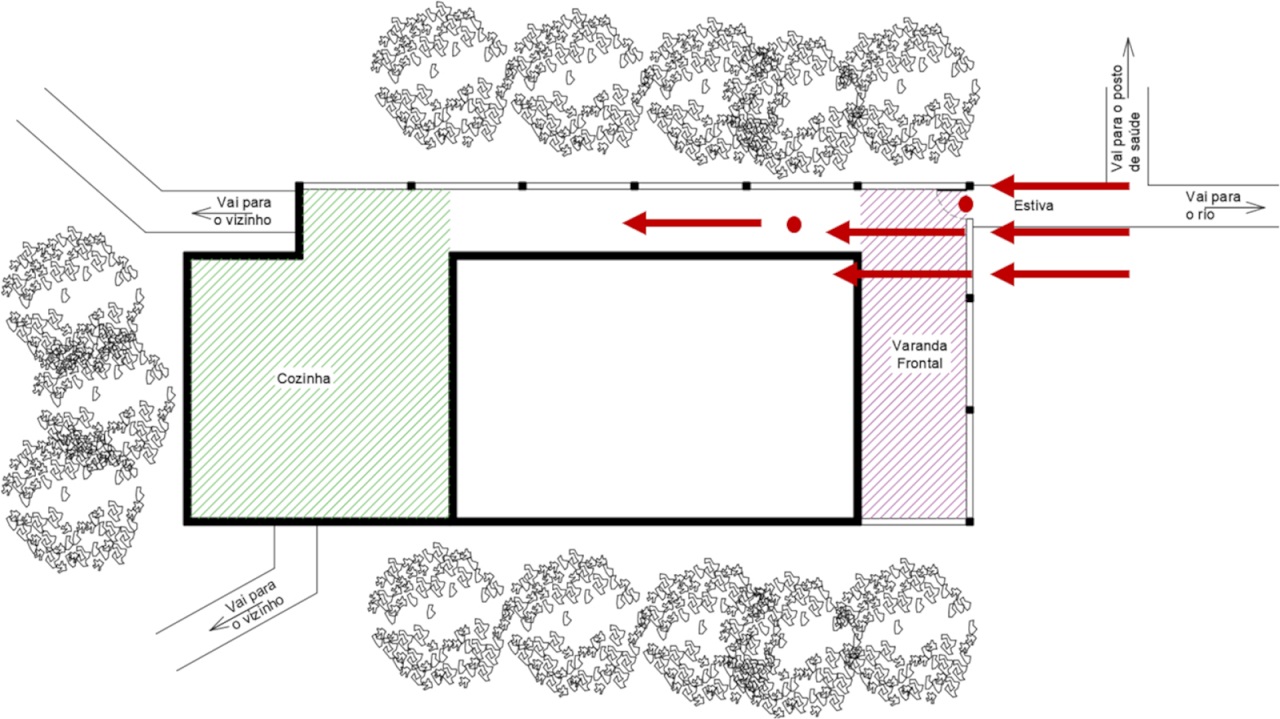

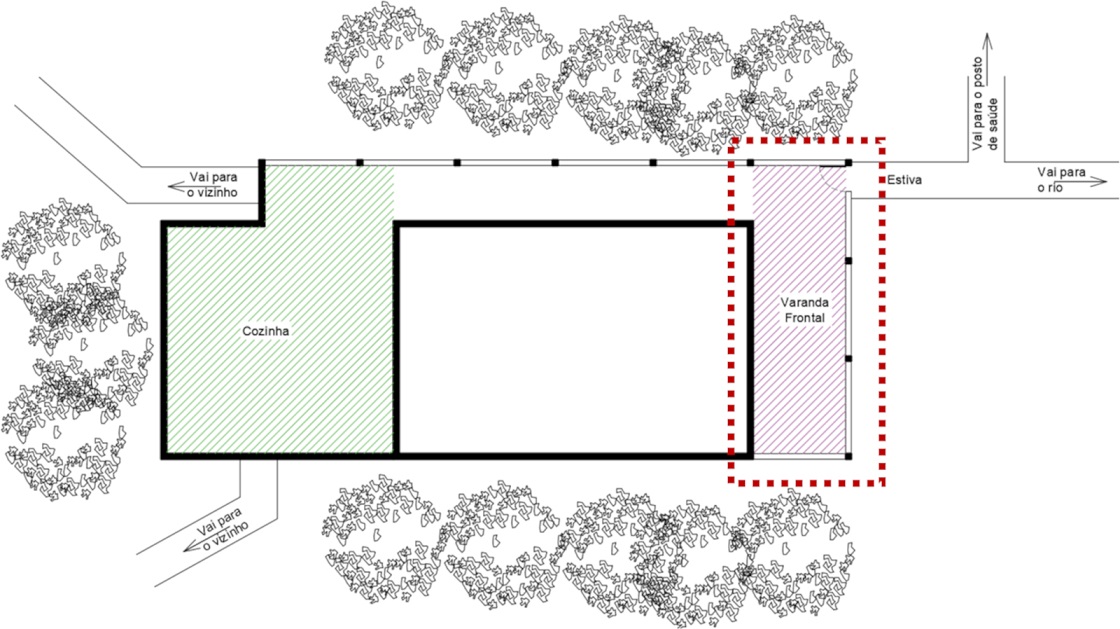

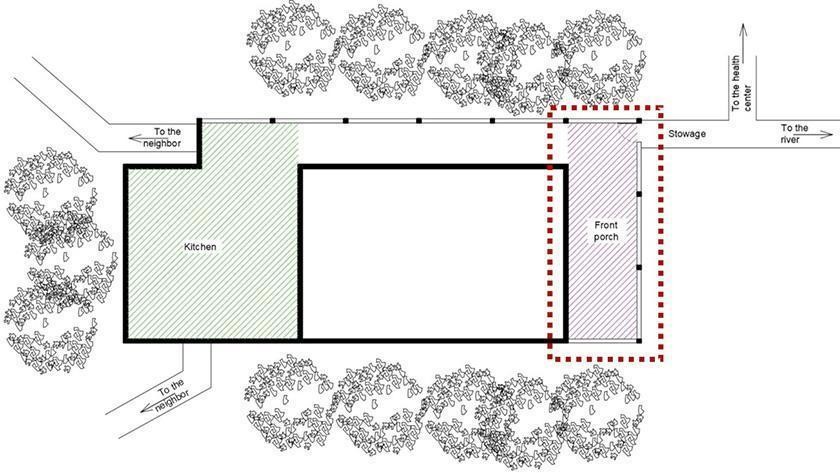

Apesar de ser uma comunidade em situação geográfica semelhante à da Ilha das Onças, no Pará, ou seja, na parte costeira do bioma Amazônia, as decisões sobre a moradia em relação ao “espaço de transição” diferem, pois na Ilha de Sababa, Maranhão, as casas não possuem varandas frontais (Figura 12). A porta de entrada da casa é ligada à terra firme por uma escada, e percebe-se a colocação de folhas de palmeiras no piso, em frente às edificações. Nesse caso, o espaço de transição se apresenta na mudança de textura do passeio, que sai do caminho por terra para o trecho com palhas, e pela subida de alguns degraus para acessar a casa. As palhas à frente da casa funcionam como um espaço simbólico e sensorial de transição, corroborando colocações de Alexander, Ishikawa e Silverstein (1977), que consideram, para esse padrão, qualquer situação de quebra de uma continuidade. Os autores ilustram também a transição causada por mudança de nível no caminho, representada, nesse estudo, pelas escadas construídas na frente das casas.

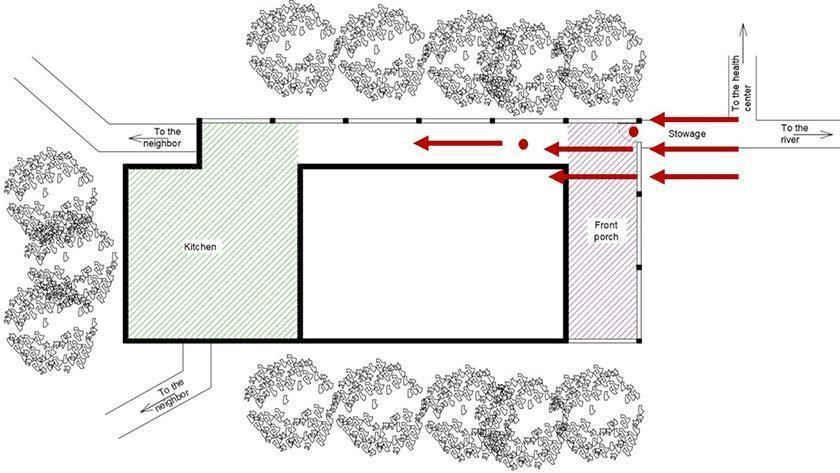

Quanto ao gradiente de intimidade, as moradias analisadas utilizam a cozinha ao fundo como lugar de encontro privado. Ela é executada com dimensões maiores, de modo a recepcionar visitas menos formais (Figura 13). Por se tratar de uma representação espacial em que o ambiente interno da casa está mais exposto ao exterior, devido à inexistência de varanda frontal, o gradiente de intimidade inicia-se na escada frontal, e avança, estabelecendo-se pela presença de parede entre a sala de estar e os demais ambientes (Figura 13). Essa solução possibilita o controle de privacidade em relação a visitantes menos íntimos, pois dificulta o alcance visual da cozinha, tanto da sala de estar como da escada frontal. Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa e Coffin, Angel (1969) relatam situação semelhante nas casas do Peru, em que os visitantes formais são recebidos na sala de estar social, separada do restante da casa.

Em relação às necessidades espaciais dos ocupantes da moradia palafítica tradicional, no Maranhão, percebeu-se que ela também obedece à configuração frente e fundo, com a sala de estar como ambiente frontal e a cozinha ao fundo. Apesar das moradias serem em palafitas, o ecossistema de terra firme permite caminhos sobre o solo, e o acesso à casa se faz pelas escadas, à porta da frente. Elas são o elemento mais público em relação aos demais ambientes da casa, seguidos da sala de estar que, para avanço gradativo da privacidade, é separada dos demais ambientes por uma parede com abertura deslocada em relação à porta frontal. A cozinha é o ambiente mais privado, sendo destinado à recepção de familiares e amigos. O espaço de transição é demarcado sensorialmente e simbolicamente pela colocação de palhas no piso, em frente às casas, e pelo desnível em relação à porta de acesso ao domicílio.

5 Considerações finais

A vivência espacial da casa estabelece representações estruturadas nas relações ocorridas entre as pessoas, a arquitetura e o contexto sociocultural. A análise das representações espaciais pelo uso da moradia tradicional amazônica, fundamentada em padrões de linguagem e propriedade fundamental, foi sistematizada por Alexander, Ishikawa, Silverstein (1977) e Alexander (2002). Esse método apresentou potencial para instrumentalizar o processo a partir de categorias relacionadas às necessidades espaciais humanas no contexto amazônico, pois possibilitou construir um entendimento projetual acerca do modo como os padrões representam os usos cotidianamente praticados pelos moradores.

As comunidades tradicionais estudadas no bioma Amazônia estão em ecossistemas diferentes – várzea e terra firme –, mas apresentam a mesma decisão quanto à construção das casas em palafitas, solução orientada pelo quotidiano alagável. Identificaram-se elementos de homogeneidade na representação do espaço de transição entre o contexto externo e o espaço privativo da casa. Evidenciando suas particularidades, o modo como esses espaços são definidos pelo usuário é concordante com a relação que eles estabelecem com o entorno, seja o ecossistema ou a vizinhança. Quanto ao gradiente, reforça-se a afirmação de Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin, Angel (1969) e Alexander, Ishikawa, Silverstein (1977) sobre as casas da América Latina demandarem um controle de privacidade pela configuração da sua frente como ambiente mais formal e seu fundo como ambiente mais privativo. Todavia, o contexto de cada lugar demonstrou modos diferentes de estabelecê-lo, o que suscita uma representação espacial que orienta a concepção projetual inserindo conteúdo da experiência do usuário ao conhecimento do projetista (PERDIGÃO, BRUNA, 2009).

Nessa perspectiva, é importante compreender o espaço doméstico tradicional amazônico a partir do uso. Seus elementos enriquecem o processo de projeto ampliando a capacidade de configuração de propostas projetuais relacionadas à vivência espacial do usuário latino-americano. Com base nos estudos realizados no Peru (ALEXANDER et al., 1969) e na análise realizada em comunidades tradicionais palafíticas na Amazônia Legal brasileira, destaca-se que, em alguns lugares na América Latina, as pessoas estabelecem diferentes níveis de proximidade entre si, o que demanda transições entre o comportamento público e o privado, e gradientes nos acessos aos ambientes da casa. O modo como essas soluções são manifestadas diferem conforme o contexto, expondo particularidades locais relevantes ao campo teórico e prático da arquitetura. Destaca-se o contexto internacional da Amazônia, em nível regional, como uma complexidade que evidencia a importância de se conhecer a população que habita a região (ARAGÓN, 2018), pois as moradias latino-americanas possuem traços da cultura nativa, conteúdo que não pode ser negligenciado pelos processos hegemônicos de produção da arquitetura mundial. Essa postura favorece a formação profissional que aceita o desafio de entender as peculiaridades humanas no uso do espaço construído, e inaugura um modo de pensar a arquitetura que tem a tradição de um lugar como elemento orientador do processo de projeto comprometido com o quotidiano, no ambiente construído.

Referências

ALEXANDER, C.; ISHIKAWA, S.; SILVERSTEIN, M. A pattern language: towns, buildings, constructions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

ALEXANDER, C.; HIRSHEN, S.; ISHIKAWA, S.; COFFIN, C.; ANGEL, S. Houses generated by patterns. Berkeley: The Center for Environmental Structure, 1969.

ALEXANDER, C. The nature of order: an essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe – Book one: The phenomenon of life. Berkeley: The Center for Environmental Structure, 2002.

ARAGÓN, L. E. A dimensão internacional da Amazônia: um aporte para sua interpretação. Nera, ano 21, n. 42, p. 14-33, 2018.

BURNETT, F. (org.). Arquitetura como resistência: autoprodução da moradia popular no Maranhão. São Luís: Eduema/Fapema, 2020.

CASTRO, E. Belém do Grão-Pará: de águas e de mudanças nas paisagens. In: STOLL, E.; ALENCAR, E.; FOLHES, R.; MEDAETS, C. (orgs.). Paisagens evanescentes: estudos sobre a percepção das transformações nas paisagens pelos moradores dos rios Amazônicos. Belém: Naea, 2019. p. 163-192.

CRUZ, V. do C. O rio como espaço de referência identitária: reflexões sobre a identidade ribeirinha na Amazônia. In: TRINDADE JR., S-C. C.; TAVARES, M. G. C. (orgs.). Cidades ribeirinhas na Amazônia: mudanças e permanências. Belém: Edufpa, 2008.

DE LAS CASAS, C. A. El bioma amazónico y el Acuerdo de París: cooperación y gobernanza. Revista de Estudios Brasileños, v. 6, n. 11, p. 155-167, 2019.

DEL RIO, V. Projeto de arquitetura: entre a criatividade e o método. In: DEL RIO, V. (org.). Arquitetura: pesquisa & projeto. São Paulo: ProEditores; Rio de Janeiro: FAU/UFRJ, 1998.

GIL, A. C. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. 6. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2008.

GROAT, L; WANG, D. Architectural Research Methods. 2. ed. New Jersey: Wiley, 2013.

LIFSCHITZ, J. A. Comunidades tradicionais e neocomunidades. Rio de Janeiro: Contracapa, 2011.

LOUREIRO, V. R. Amazônia: Estado, homem, natureza. Belém: Cejup, 1992.

MALARD, M. L. As aparências em arquitetura. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2006.

MENEZES, T. M. S. Referências ao projeto de arquitetura pelo tipo palafita amazônico na Vila da Barca (Belém-PA). 2015. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) – Universidade Federal do Pará, Instituto de Tecnologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Belém, 2015.

NAVARRO, A. G. As cidades lacustres do Maranhão: as estearias sob um olhar histórico e arqueológico. Diálogos, v.21, n.3, 2017, p. 126-142

NAVARRO, A. G. New evidence for late first-millennium: AD stilt-house settlements in Eastern Amazonia. Antiquity, v. 92, n. 366, p. 1586-1603, 2018.

OLIVEIRA, R. C. Construção, composição, proposição: o projeto como campo de investigação epistemológica. In: CANEZ, A. P.; SILVA, C. A. (orgs.). Composição, partido e programa: uma revisão crítica de conceitos em mutação. Porto Alegre: UniRitter, 2010.

PAES LOUREIRO, J. J. Cultura amazônica: uma poética do imaginário. 5. ed. Manaus: Editora Valer, 2015.

PAIXÃO, R. T. da. Estudo longitudinal de famílias remanejadas e reassentadas no Projeto Taboquinha (Icoaraci, Belém, Pará) como subsídio ao projeto de arquitetura em habitação social. 2019. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) – Universidade Federal do Pará, Instituto de Tecnologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Belém, 2019.

PERDIGÃO, A. K. de A. V. A produção do espaço habitacional expressando a identidade local em Belém (PA): a experiência de reassentamento CDP. In: X ENCONTRO NACIONAL DA ANPUR., 2003, Belo Horizonte. Anais [...]. Belo Horizonte: ANPUR, 2003.

PERDIGÃO, A. K. de A. V. Teoria da produção arquitetônica na Amazônia. In: CARDOSO, A. C. D. (org.). Trajetórias de pesquisa do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Belém: UFPA/PPGA, 2019.

PERDIGÃO, A. K. A. V.; BRUNA, G. C. Representações espaciais na concepção arquitetônica. In: IV PROJETAR 2009. Projeto como investigação: antologia. São Paulo: Alter Market, 2009.

STOLL, E.; ALENCAR, E.; MEDAETS, C.; FOLHES, R. Etnografar as “paisagens evanescentes” da Amazônia. In: STOLL, E.; ALENCAR, E.; FOLHES, R.; MEDAETS, C. (orgs.). Paisagens evanescentes: estudos sobre a percepção das transformações nas paisagens pelos moradores dos rios Amazônicos. Belém: Naea, 2019.

TRINDADE JR, S-C C. A cidade e o rio na Amazônia: mudanças e permanências face às transformações sub-regionais. Terceira Margem: Amazônia, v. 1, n. 1, p. 171-183, 2012.

VELOSO, S. Reportagem Viagem a uma Amazônia desconhecida. LOPES, F. G. Infográfico Amazônia Legal Brasileira. Darcy. Secretaria de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília, edição especial on-line, 2020. Disponível em: http://www.revistadarcy.unb.br/viagem-a-uma-amazonia-desconhecida. Acesso em 02 jun. 2021.

VIRGÍLIO, M. F.; PERDIGÃO, A. K. de A. V. Sustentabilidade e a cultura do lugar: o habitat ribeirinho na Amazônia. Revista Nacional de Gerenciamento de Cidades, v. 8, n. 67, p. 148-159, 2020.

Spatial representations by the usage in the traditional Amazonian dwelling

Izabel Cristina Melo de Oliveira Nascimento is an Architect and Urban Planner, with a Master's in Design and a Ph.D. candidate in Architecture and Urbanism. She develops her research at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil, where she studies design processes, participatory design, and housing. izabel.nas13@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/2785790175730151

Ana Kláudia de Almeida Viana Perdigão is an Architect and Urban Planner and a Ph.D. in Architecture and Urbanism. She is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism and the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil. She coordinates the Human Space and Development Laboratory (LEDH) and studies design processes and Amazonian habitats. klaudiaufpa@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/9009878908080486

How to quote this text: Nascimento, I. C. M.O.; Perdigão, A. K. A. V. , 2021. Spatial representations by the usage in the traditional Amazonian dwelling. Translated from Portuguese by Editage. V!RUS, 22, July. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus22/?sec=4&item=13&lang=en>. [Accessed: 13 July 2025].

ARTICLE SUBMITTED ON MARCH, 7, 2021

Abstract

This article presents an analysis of spatial relations in traditional Amazonian stilt houses, situated in the Brazilian states of Pará and Maranhão, relying on the patterns systematized by Christopher Alexander in Latin American dwellings in Peru. We conducted qualitative research using a systematic observation technique. The similarities in spatial representation based on the use of the built environment were identified in the analyzed houses, providing evidence of the uniqueness of each place in the configuration of spaces and their representations. The identified aspects have potential for the instrumentalization of design practices, considering that such solutions appeared as typical aspects of Latin American houses, in general. They also illustrated the particular way in which the Amazonian people produce, use, and spatially relate to their housing. This knowledge is of great relevance to the field of architecture, considering that the plurality of Latin American spatial representations requires attention to information regarding local practices. The focus of territorialization in studies on Latin American housing highlights the recognition of the existence of native elements carrying significant content that may not be contemplated by hegemonic architectural thinking.

Keywords: Traditional communities, Stilt house, Spatial representations, Amazonia

1 Introduction

Design processes and operations comprise a field of knowledge that is still little explored in architectural education, compared to the predominant methods used in architectural design teaching in Brazilian schools. Their interpretation of the complexity and dynamics of everyday life is rare. Therefore, the theoretical understanding of design practices involving the materiality and immateriality of architecture makes the project an object of epistemological investigation. According to Malard (2006), design is determined by the culture, people’s way of life, and their surroundings. That is, it is specific to each culture and congruent with the social organization of that group. It depends on the knowledge and reflection about the spatial needs of the inhabitant and the context of culture insertion in the natural and built landscape.

These spatial needs are related to the physical characteristics of the building, the way the residents understand the spaces of the house, and to the social and cultural context of use of this architecture, represented in the rooms. This spatial representation, according to Perdigão and Bruna (2009), is a guiding principle of the design process interpretation of the architectural environment by experience. The Amazon stilted habitat, in the context of traditional communities, becomes a valuable empirical reality for decoding the mechanisms used to produce the built environment without architects. The observation and survey of actions in loco, especially regarding the transformations and adaptations made by the residents, contribute to strategies, without underestimating the involved complexity, to produce formal knowledge in the field of architecture directed at the training of the architect and their performance.

This professional activity is done with systematized technical and theoretical knowledge that understands the relevance of incorporating variables of a spatial and sociocultural nature into the process (Del Rio, 1998), leading the professional to a self-reflective posture concerning their decisions (Oliveira, 2010). The need for the designer to commit to the suitability of the architecture to the living space, established by the user, also applies to Amazon. The manner in which Amazonian inhabitants relate to nature influences the way they relate to their own house. The professional must understand the spatial representations established by the inhabitant during the living process and identify the peculiar elements of spatial use in that daily life as guidelines for the design process of a place’s traditional housing.

The description of how the traditional Amazonian inhabitants understand and produce housing spaces, motivated by use, is the guiding component of this research. For this purpose, we considered the production of traditional stilt houses in the Amazon Biome, in the area delimited as Brazilian Legal Amazon, in traditional communities in the states of Pará and Maranhão, in a region historically and culturally recognized for the existence of stilt houses. This study used qualitative research and systematic observation techniques in which the identified aspects were guided by patterns of use systematized by Alexander et al. (1969). We sought to identify how these patterns manifested in and applied to the traditional Amazon way of life, considering what would be homogeneous and what would be unique as a result of the investigation, to broaden the understanding of Latin American living and housing. The result highlights the homogeneous design variables concerning Latin American houses but also the peculiar way in which they manifest themselves, depending on the cultural, social, and natural context of insertion.

2 The tradition of living on stilts in the Amazon

The Amazon is a territory with diverse manifestations of a “complex social-ecological system” (De Las Casas, 2019, p. 156, our translation). Because the Amazon extends over nine Latin American countries, actions there affect those countries and their Latin American neighbors (Aragón, 2018), justifying the importance of understanding the region. However, this region can only be understood by integrating knowledge about the human beings who inhabit it and the nature that encompasses it and clarifying the already established harmonic relationship between the two elements (Paes Loureiro, 2015). This linking of human life in harmony with the surrounding nature is reflected in the use of natural resources with respect to nature’s seasonality (Stoll et al., 2019), practices learned in daily life, and characteristics of family economic activities based on social knowledge (Loureiro, 1992).

De Las Casas (2019, p. 156) considered the Amazon Biome “one of the main components of the social-ecological system, the Amazon, understood as an analysis and management unit.” In his work, he highlighted the importance of the Amazon in the world stage and the necessary integration of political actions dedicated to this territory. The Amazon Biome has a complex social-ecological system, requiring approaches that consider the cultural landscape and the transformative role of the culture of the men and women who live in the forest. On a global scale, the biome is present in French Guiana, Suriname, Guiana, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil (De Las Casas, 2019). The latter comprises the largest extension of what is called the Brazilian Legal Amazon (Figure 1), consisting of the entire territory of the states of Acre, Amazonas, Roraima, Amapá, and Pará, a large part of the state of Rondônia, and in smaller extensions in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, and Mato Grosso (Veloso, 2020).

Fig. 1: The Amazon Biome and Brazilian Legal Amazon. Source: Veloso, 2020. Elaborated by: Francisco George Lopes/Secom UnB, modified by the authors, 2021.

Because of the changes that have occurred since the Industrial Revolution, an Amazonian approach with a focus on humane has become relevant, given the necessary elucidation, recording, and insertion in the scientific field of intrinsic factors to human activities that structured the traditional culture of Amazonian housing. Communities formed by people who share ancestral beliefs and a common way of life, maintained by inherited knowledge and the way they inhabit the territory, are characterized as traditional (Lifschitz, 2011). In the Amazon Biome, traditional communities are established by stilt houses. They possess a tradition that has remained apart from the influence of other places in Brazil and Latin America and have established a peculiar and different way of life (Paes Loureiro, 2015). The houses are built using inherited knowledge about water flows, which establishes their tradition in the daily relationship between the house and the natural surroundings and configures what Menezes (2015, p. 108, our translation) identified as the “Amazonian stilt house type.”

This way of living on the water has existed since the pre-colonial period, when they were called stilt-house settlements, because they were houses suspended by tree trunks, that is, by struts (Navarro, 2017). According to the author, the choice of dwelling over the water was made at that time, both for cultural reasons and for protection against the possibility of enemy attacks. Archaeological studies on stilt-house settlements in eastern Amazonia have identified a greater number of stilt houses on the coast of Pará, near Marajó Island (PA), and on the coast of Maranhão, in the Turiaçu River region (Navarro, 2018). For this reason, we considered it relevant to carry out the study of traditional Amazonian stilt houses in these locations, specifically on the coastal strip where the Marajó Island and the mouth of the Turiaçu River.

In Pará, traditional Amazonian housing was established based on the close relationship of the “natural man of the Amazon” (Loureiro, 1992, p. 16) with the rivers, thus presenting a territorial occupation that followed the course of the waters (Trindade Jr., 2012) and featured the Amazon riverside way of living. Cruz (2008) considered this way of life as the most typical of Amazonian populations and regional culture, which has the river as an important denominator of the choices that people make about their housing and way of living. Their buildings are made of wood from the region and, respecting the variation in the river water level, are built on stilts (Figure 2).

The relationship between housing and the Amazon natural environment in Maranhão is different from that observed in Pará, as it occurs on the riverside but away from it. The daily life of the house relates to a surrounding area that is flooded only at certain times of the year, in a part of the Amazon Biome with an upland ecosystem. Nevertheless, the residents built their houses on stilts, respecting the advance of the waters, with no access by stowage (Figure 3). This reality evidences a plural and diverse context, with spatial and territorial particularities defined by daily experiences (Trindade Jr., 2012). According to Castro (2019), the Amazon presents floodplain, mangrove, or upland ecosystems, which demands an understanding of the daily life of the rivers, lakes, streams, igapós, and tides of which they are composed.

Valuing aspects of a given place is an important practice in the design process. Menezes (2015) reported the process of housing adaptation of residents relocated to the Vila da Barca Project in Belém, Pará. Coming from a riverside community, they made modifications to the house they received in a “rescue of the Amazonian stilt house type” (Menezes, 2015, p. 108). Another example is the Taboquinha project (Paixão, 2019), district of Icoaraci, in Belém, as housing adaptation led to the rescue of the “house of origin” in terms of its physical and spatial relations. Evidencing the relationship between theory and practice in professional performance, which values sociocultural aspects, Perdigão (2003) presented a “flexible architectural proposal” applied to a relocation process that valued “typological de-standardization,” providing people’s identification with the new dwelling. Perdigão (2019) highlighted the potential of information from Amazonians living in the formulation of theories of architectural production because the characteristics of the local way of inhabiting and the spatial experience are pertinent information in the design process concerning the location.

3 Analysis categories of spatial representations by housing use

The area encompassed by the Amazon Biome extends over nine Latin American countries; however, this study on living was focused on the Brazilian Legal Amazon region, more specifically, on insular coastal communities in the states of Pará and Maranhão. We aimed to highlight solutions that reflect the way people relate to their dwellings by interpreting the spatial representations established by the users of each place in the daily use of the Amazon traditional stilt house. To carry out the study, we assumed the use of qualitative research, collecting data from the observed natural context, according to Groat and Wang (2013). The technique used in the field was systematic observation (Gil, 2008), as the aspects observed were previously established and based on the research objective.

To substantiate the aspects observed and the categories of analysis applied, we considered the studies and systematizations by Alexander et al. (1969), Alexander et al. (1977), and Alexander (2002). These authors reported representations in buildings and systematized elements that were the essence of the “life” of these places. For them, this “life” is the identifying attribute of quality in a building. However, it only emerges from people’s actions in space. Alexander et al. (1977) paid special attention to traditional architecture by understanding people’s ability to supply their own spatial needs. Alexander et al. (1969) emphasized the importance of valuing the identity aspects of a place, as exemplified by their propositions, considering the way of life in Lima, Peru. In the proposal and execution of their Proyecto Experimental de Vivienda, they preserved what they called the “idiosyncratic needs of the individual families who buy the houses” (Alexander et al., 1969, p. 6).

The authors identified that the dynamics of the use of spaces had a pattern of language derived from repeated actions that occurred in the daily life of the places (Alexander et al., 1977; Alexander et al., 1969). They systematized them as prior instructions for such spatialities, considering their refinement when applied to other contexts. Later, Alexander (2002) published 15 fundamental properties to be considered to achieve “life” in designed structures. On this occasion, he related to them the language patterns, as “functional notes” applicable to the design process. Among those identified by the author, gradient property was used in this study. For him, it evidenced a natural response to situations of change in space, adapting to them. The patterns selected as analysis categories and which are related to this property were the “transition space” (Figure 4) and the “intimacy gradient” (Figure 5).

Alexander, Hirshen, Ishikawa, Coffin and Angel (1969) described it as recurrent in Latin American dwellings, a gradient of intimacy that begins in the less private rooms at the front of the house and proceeds to the most intimate at the back (Figure 5). The authors considered it essential for these houses to have a room immediately after the entrance, as people establish different levels of proximity among themselves, from casual acquaintances who do not even enter the house, to the closest ones, received in the kitchen. The aspect related to the transition space between the street and the house’s internal environment was described by Alexander and colleagues (1969) as a pattern applicable to any house that may appear in several ways, through changes in elements such as the view, light, level, surface, sound, scale, or any action that interrupts continuity. Therefore, aspects to be observed in the field were established regarding the fact that the intimacy gradient indicated fewer private rooms in the front of the house and more private rooms in the back and how the transitional space occurred in the studied communities. These elements help in understanding the characteristics of different places by recording the spatial relationships produced in the experience.

4 The use of the traditional Amazonian stilt house

This section discusses the context of traditional stilt house use in the Amazon Biome, focusing on the identification of spatial solutions in two distinct ecosystems: floodplains and uplands. Understanding the spatial representations established by the residents contributes to highlighting solutions applicable to the place-oriented design process, evidencing the way they understand and relate to the house. We established as spatial representation analysis categories the patterns of “transition space” and “intimacy gradient” (Alexander et al., 1977; Alexander et al., 1969). The study contributes to the recording of homogeneous and peculiar elements of the culture of housing use in each place, as summarized in Table 1 and detailed in the following sub-items.

4.1 Spatial representation by use in traditional housing in the state of Pará

In this study, the traditional stilted housing in the Pará Amazon was represented by houses located on Ilha das Onças, Pará, near Marajó Island, in a habitat-related to what Cruz (2008, p. 56) called “riverside culture.” Their construction takes place on the riverbanks, the residents build houses and paths (stowage) in wood, and their daily lives obey the seasonality of the surrounding waters. With the floods and ebb tides of the rivers, this way of life is feasible in buildings on stilts, in a floodplain ecosystem, in areas that are floodable during most of the year. House 1 (Figure 6), according to Virgílio and Perdigão (2020), was built by people from the city of Belém, who had known riverside life since their childhood, which influenced their decision to leave the city and helped them choose a place to live. Conversely, the residents of House 2 (Figure 6) occupied a house that used to belong to their mother. In the surroundings, nearby houses were connected by wooden bridges, a common practice in areas where neighbors belong to the same family.

Fig. 6: Houses on stilts (House 1 on the left and House 2 on the right), Ilha das Onças, Pará state. Source: Collection of the Space and Human Development Laboratory (Laboratório Espaço e Desenvolvimento Humano), 2019.

Regarding the use of House 1, Virgílio and Perdigão (2020) reported that the porch and kitchen were the spaces most used by the residents. In analyzing Figure 7, we noticed the option of constructing a front porch and kitchen at the back. Although Alexander et al. (1977, p. 610) considered “a front porch or entrance room most public of all” spaces, in this case, because it is an isolated house, the stowage gives access to the house only to those who arrive by boat through the front part. The intimacy gradient begins at the dock and stowage, and only then enters the front porch, where visitors are received. For this reason, the kitchen is a small space dedicated to food preparation activities, and the intimacy gradient allows the front porch to be used privately.

As for the transition space, according to Alexander et al. (1969) and Alexander et al. (1977), its creation is what guarantees a less abrupt arrival to the interior of the house. This demarcation, physical or symbolic, is related to the path between what is considered public and what is considered private. In the case of riverside life, in general, people have a relationship with the river that is much like the one land dwellers have with the street. They use it to move around to carry out their activities and to get to their neighbors’ houses. Therefore, in House 1, the dock and front stowage are the transition spaces (Figure 8), as all visitors need to reach the house by boat because it is isolated from the other houses in the community.

In the case of House 2, because it is in a context of proximity with other houses, as neighbors belong to the same family, it has access through stowage that connects the houses. In this context, the decision of the dweller about privacy control, instead of taking place in the stowage, starts at the access doors to the house, such as the front porch door. In this way, the porch is characterized as the most public room of the building, and the closest people to the family are received in the kitchen, which is in the background (Figure 9). This configuration resembles the one presented by Alexander et al. (1969) regarding houses in Peru, as the front space is delimited to receive more formal visitors, and this privacy control gradually decreases until the most intimate area of the house. Because it is an area for preparing food and receiving family and friends, the kitchen is larger than in House 1.

Because it is a house accessed by the front stowage and other stowages connecting neighboring buildings, House 2 has the front porch as the transition space. Unlike House 1, which is isolated, this proximity between houses establishes public paths through the stowage, and the transition space is internal to the house. This configuration also resembles the Peruvian house model presented by Alexander et al. (1969), in which there is a frontal space delimitation for this transition. In the case of the riverside dwelling, this space is the front porch (Figure 10). It serves as a gradual transition from an external environment to a house interior.

Concerning the human spatial needs of the traditional stilt house in Pará, we perceived two different contexts of building implementation: the first was represented by House 1, which was isolated from the other houses, and the second by House 2, in a network of houses belonging to the same family. In both cases, we observed the same positioning of environments—a porch in the front and a kitchen in the back—in relation to the building as a whole. However, the isolated housing established a gradient of intimacy that started externally to the building, in the stowage and pier, while the gradient of the house close to neighbors started on the front porch. This characterization influenced the configuration of the kitchen that, in the first case, was small and intended only for food preparation, and, in the second case, was configured, with the front porch used to control privacy and to receive visitors and family members.

4.2 Spatial representation by use in traditional dwellings in the Maranhão state

In traditional stilt houses in the Maranhão Amazon, a closer relationship with land is evident. They are far from riverbanks, entering land in search of solid ground, maintaining the relationship with the river in the construction of a single pier (Figure 11), for collective use, and far from other houses. There is an awareness of knowledge about the seasonality of the surrounding nature because the inhabitants build their houses suspended above the ground, at a height that matches the flooding periods to prevent the water from invading them. However, because they face long periods of drought and dry land, they do not build paths on wooden platforms, but use the land itself to access the buildings. These communities are constituted by stilt houses traditionally built on solid ground that coexist with shorter periods of flooded areas.

Fig. 11: Housing on stilts and a river access pier, Ilha de Sababa, Maranhão state. Source: Collection of the Space and Human Development Laboratory (Laboratório Espaço e Desenvolvimento Humano -LEDH), 2020.

Despite being a community that exhibits a similar geographic situation to the Ilha das Onças, in Pará—that is, in the coastal part of the Amazon Biome—decisions about housing in relation to the “transition space” differ, because in Sababa Island, Maranhão, the houses do not have front porches (Figure 12). The entrance door of the house is linked to the solid ground by a ladder, and the placement of palm leaves on the floor in front of the buildings is noteworthy. In this case, the transition space appears in the change in texture of the sidewalk, which leaves the dirt path toward a stretch with straws, and by the climbing of some steps to access the house. The straws in front of the house behave as a symbolic and sensorial space of transition, corroborating the statements of Alexander et al. (1977), who considered, for this pattern, any situation of continuity breaking. The authors also illustrated the transition caused by a level change in the path represented in this study by the stairs built in front of the houses.

As for the intimacy gradient, the analyzed houses used the kitchen in the background as a private meeting place. It is built with larger dimensions to receive fewer formal guests (Figure 13). Because it is a spatial representation in which the house’s internal environment is more exposed to the outside, owing to the absence of a front porch, the intimacy gradient begins at the front stairway, advances, and is established by the presence of a wall between the living room and the other rooms (Figure 13). This solution enables privacy control in relation to less intimate visitors, as it hinders the visual reach of the kitchen from both the living room and the front staircase. Alexander et al. (1969) reported a similar situation in Peruvian houses, where formal visitors were received in the social living room, separated from the rest of the house.

Regarding the spatial needs of the occupants of the traditional stilt house in Maranhão, we noticed that the house also followed the front and back configuration, with the living room as the front environment and the kitchen in the back. Although the houses were on stilts, the upland ecosystem allowed for paths on the ground, and access to the house was through the stairs at the front door. They were the most public element in relation to the other rooms of the house, followed by the living room, which, for the gradual advancement of privacy, was separated from the other rooms by a wall with an opening displaced in relation to the front door. The kitchen was the most private space intended for the reception of family and friends. The transition space was sensorially and symbolically demarcated by the placement of straws on the floor in front of the houses and by the unevenness in relation to the access door to the home.

5 Final considerations

The spatial experience of the house establishes representations structured in the relationships between people, architecture, and the sociocultural context. The analysis of spatial representations based on traditional Amazonian housing, language patterns, and fundamental property, was systematized by Alexander et al. (1977) and Alexander (2002). This method showed potential for instrumentalizing the process from categories related to human spatial needs in the Amazonian context because it allowed for the development of a design understanding of how the patterns represent the everyday uses practiced by the residents.

The traditional communities studied in the Amazon Biome were in different ecosystems, including wetlands and uplands, but presented the same decision regarding the construction of houses on stilts, a solution guided by their floodable daily life. We identified elements of homogeneity in the representation of the transition space between the external context and the house’s private space. Evidencing their particularities, the way these spaces are defined by the user is concordant with the relationship they establish with the surroundings— either the ecosystem or the neighborhood. Regarding the gradient, we reinforced the affirmations of Alexander et al. (1969) and Alexander et al. (1977) about Latin American houses demanding privacy control through the configuration of their front as a more formal environment and their back as a more private space. However, the context of each place demonstrated different ways of establishing this, giving rise to a spatial representation that guided the design concept by inserting content from the users’ experience into the designers’ knowledge (Perdigão and Bruna, 2009).

From this perspective, it is important to understand the traditional Amazonian domestic space based on its use. Its elements enrich the design process, expanding the capacity to configure design proposals related to the spatial experience of Latin American users. Based on studies carried out in Peru (Alexander et al., 1969) and on the analysis carried out in traditional stilt-house communities in the Brazilian Legal Amazon, it is highlighted that in some places in Latin America, people establish different levels of proximity among themselves, which demands transitions between public and private behavior and gradients in the access to the spaces of the house. The way these solutions are expressed differs depending on the context, exposing local particularities relevant to the theoretical and practical fields of architecture. We highlight the international context of the Amazon, at a regional level, as a complexity that evidences the importance of knowing the population that inhabits the region (Aragón, 2018), because Latin American dwellings have traces of native culture and content that cannot be neglected by the hegemonic processes of world architecture production. This attitude favors professional training that accepts the challenge of understanding human peculiarities in the use of the built space and inaugurates a way of thinking about architecture that has the tradition of place as the guiding element of the project process committed to everyday life in the built environment.

References

Alexander, C., 2002. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Book One: The Phenomenon of Life. Berkeley: The Center for Environmental Structure.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., and Silverstein, M., 1977. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Constructions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, C., Hirshen, S., Ishikawa, S., Koffin, C., and Angel, S., 1969. Houses Generated by Patterns. Berkeley: The Center for Environmental Structure.

Aragón, L. E., 2018. The international dimension of the Amazon: A contribution to its interpretation. Nera, 21(42), pp. 14–33. https://doi.org/10.47946/rnera.v0i42.5676

Burnett, F. (ed.), 2020. Architecture as Resistance: Self-production of Popular Housing in Maranhão. São Luís: Eduema/Fapema.

Castro, E., 2019. Belém do Grão-Pará: water and landscape changes. In: E. Stoll, E. F. Alencar, C. Medaets, and R. Theophilo folhes (eds.), Evanescent Landscapes: Studies on the Perception of Landscape Transformations by Amazonian River Dwellers. Belém: Naea, pp. 163–194.

Cruz, V. C., 2008. The river as a space of identity reference: reflections on riverine identity in the Amazon. In: M. G. C. Tavares and S-C. C. Trindade Jr., (eds.). Riverside Towns in the Amazon: Changes and Permanence. Belém: Edufpa, pp. 611–616.

De Las Casas, C. A., 2019. El bioma amazónico y el Acuerdo de París: Cooperación y gobernanza. Revista de Estudios Brasileños, 6(11), pp. 155–167. https://doi.org/10.14201/reb2019611155167

Del Rio, V., 1998. Architecture design: Between creativity and method. In: V. del Rio (ed.). Architecture: Research & Design. São Paulo: Pro Editores.

Gil, A. C., 2008. Methods and Techniques of Social Research. 6th ed. São Paulo: Atlas.

Groat, L., and Wang, D., 2013. Architectural Research Methods. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Wiley.

Lifschitz, J. A., 2011. Traditional Communities and Neo-communities. Rio de Janeiro: Contracapa.

Loureiro, V. R., 1992. Amazon: State, Man, Nature. Belém: Edicoes Cejup.

Malard, M. L., 2006. Appearances in Architecture. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

Menezes, T. M. S., 2015. References to the Architectural Design for the Amazonian Stilt House Type in Vila da Barca (Belém, PA). Master’s thesis, Federal University of Pará, Institute of Technology, Belém.

Navarro, A. G., 2017. The lake cities in Maranhão: The pile dwellings under a historical and archaeological view. Dialogues, 21(3), pp. 126–142

Navarro, A. G., 2018. New evidence for late first-millennium: AD stilt-house settlements in Eastern Amazonia. Antiquity, 92(366), pp. 1586–1603. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.162

Oliveira, R. C., 2010. Construction, composition, proposition: the project as a field of epistemological investigation. In: A. P. Canez and C. A. Silva (eds.). Composition, Party and Program: A Critical Review of Changing Concepts. Porto Alegre: UniRitter.

Paes Loureiro, J. D. J., 2015. Amazonian Culture: A Poetry of the Imagination. 5th ed. Manaus: Editora Valer.

Paixão, R. T. da., 2019. Longitudinal Study of Resettled and Relocated Families in the Taboquinha Project (Icoaraci, Belém, Pará) as a Subsidy to the Architectural Design in Social Housing. Master’s thesis, Federal University of Pará, Institute of Technology, Belém.

Perdigão, A. K., 2003. The production of housing space expressing local identity in Belém (PA): the CDP resettlement experience. In: Encontro Nacional da ANPUR 10, 2003, Belo Horizonte. Belo Horizonte: ANPUR.

Perdigão, A. K., 2019. Theory of architectural production in the Amazon. In: A. C. D. Cardoso (ed.), Research Paths of the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism. Belém: UFPA/PPGA.

Perdigão, A. K., and Bruna, G. C., 2009. Spatial representations in architectural conception. In: R. V. Zein (ed.), Seminário IV Projetar 2009. Design as Investigation: Anthology. São Paulo: Alter Market.

Stoll, E., Alencar, E. F., Medaets, C, and Theophilo, R., folhes (eds.), 2019. Ethnographing the “evanescent landscapes” of the Amazon. E. Stoll, E. F. Alencar, C. Medaets, and R. Theophilo folhes (eds.), Evanescent Landscapes: Studies on the Perception of Landscape Transformations by Amazonian River Dwellers. Belém: Naea.

Trindade Jr., S-C. C., 2012. The city and the river in the Amazon: Changes and permanence in the face of subregional transformations. A Revista Terceira Margem Amazônia, 1(1), pp. 171–183.

Veloso, S., 2021. Report: Journey to an unknown Amazon. Infographic by Infográfico: Francisco George Lopes/Secom UnB for Amazônia Legal. DARCY, special online edition. Available at: http://www.revistadarcy.unb.br/viagem-a-uma-amazonia-desconhecida. [Accessed 2 Jun , 2021]

Virgílio, M. F., and Perdigão, A. K., 2020, Sustainability and the local culture: The riverine habitat in the Amazon. National Journal of City Management, 8(67), pp. 148–159.