Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema: Uma revisão necessária

Sandra Schmitt Soster é Publicitária, Arquiteta e Urbanista, Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Pesquisadora Nomads.usp, do LabAm (UFG) e do LavMuseus (UFMG). Membro dos Comitês ICOMOS-Brasil Documentação, Preparação para o risco, e Interpretações, Educação e Narrativas Patrimoniais. Membro do iPatrimônio e da REPEP. Estuda meios digitais para a gestão do patrimônio cultural, educação patrimonial e inventários participativos. soster.heritage@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/9177354683297726

Anja Pratschke é Arquiteta, Doutora em Ciência da Computação e Livre-docente em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. É Professora Associada do Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo, e do Programa de Pós-graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da mesma instituição. É co-coordenadora do Nomads.usp, onde desenvolve e orienta pesquisas sobre processos de projeto em arquitetura, cibernética e organização da informação. pratschke@sc.usp.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/9669955733350604

Como citar esse texto: SOSTER, S. S.; PRTASCHKE, A. Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema: Uma revisão necessária. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 22, Semestre 1, julho, 2021. [online]. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus22/?sec=6&item=1&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 10 Jul. 2025.

ARTIGO CONVIDADO

Resumo

Parte desse artigo foi apresentada originalmente no I Seminário Internacional sobre Preservação do Patrimônio Cultural no Território Trinacional, em 2018. O tema da V!RUS 22, “Latinoamérica: você está aqui!”, é uma oportunidade de reapresentar resultados da pesquisa de mestrado “Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema”, desenvolvida no Nomads.usp e financiada pela FAPESP. A dissertação foi defendida em 2014, no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. Para entender a importância histórica do conjunto das Trinta Missões Jesuíticas da antiga Província Jesuítica do Paraguai, a pesquisa realizou três recortes temporais: 1. o início das missões, quando constituíram um conjunto de auxílio mútuo; 2. o presente, quando os remanescentes materiais e imateriais preservam a memória e história regional, mas a separação por fronteiras nacionais ocasiona a falta de comunicação entre os órgãos responsáveis e a pouca divulgação online de informações relevantes e oficiais; e 3. o futuro, identificando que a divulgação e preservação integradas regionalmente podem potencializar o entendimento e a valorização das Missões Jesuíticas, inclusive com maior apropriação das comunidades locais. Entende-se que a valorização do patrimônio missioneiro passa pela abertura dos órgãos de preservação ao trabalho conjunto e, principalmente, com as comunidades locais.

Palavras-chave: Missões jesuíticas, Sistema, TIC, América Latina

1 Introdução

Parte deste artigo foi apresentada originalmente no I Seminário Internacional sobre Preservação do Patrimônio Cultural no Território Trinacional, em 20181. Os resultados aqui apresentados derivam da pesquisa de mestrado “Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema”, desenvolvida no Nomads.usp e financiada pela FAPESP. A dissertação foi defendida em 2014 (SOSTER, 2014), no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo. Uma breve pesquisa na Internet, em junho de 2021, mostra um crescente interesse acadêmico internacional pelas Missões Jesuíticas, incluindo diversas revisões de aspectos interculturais e do papel das Missões Jesuíticas na América do Sul, em especial do antigo conjunto que formava a Província do Paraguai, que distribui os trinta assentamentos originais entre três países: Argentina, Brasil e Paraguai, ao longo do rio Iguaçu.

A experiência histórica das Missões Jesuíticas da antiga Província do Paraguai foi analisada durante a pesquisa de mestrado, com base em levantamento de referências bibliográficas. O recorte compreende o período entre a implantação das Reduções Jesuíticas pela Companhia de Jesus (1549) e sua expulsão violenta devido ao deslocamento da linha divisória dos territórios português e espanhol (Tratado de Madri, 1750). Como constituíam uma rede de povoados com profundas relações políticas, econômicas e religiosas, foram analisadas de modo a frisar sua complementaridade como conjunto de auxílio mútuo. Contudo, diferentes fatores impediram a produção de excedentes individuais; assim, o auxílio econômico entre as missões não ocorreu na prática. E é fundamental frisar que o modelo jesuítico era uma forma de imposição ou dominação cultural sobre os povos originários e não ocorreu de maneira totalmente pacífica. Em solo português (e em território espanhol alcançado pelas bandeiras portuguesas), representava nessa época a opção de menor violência física em comparação com a captura para a escravidão.

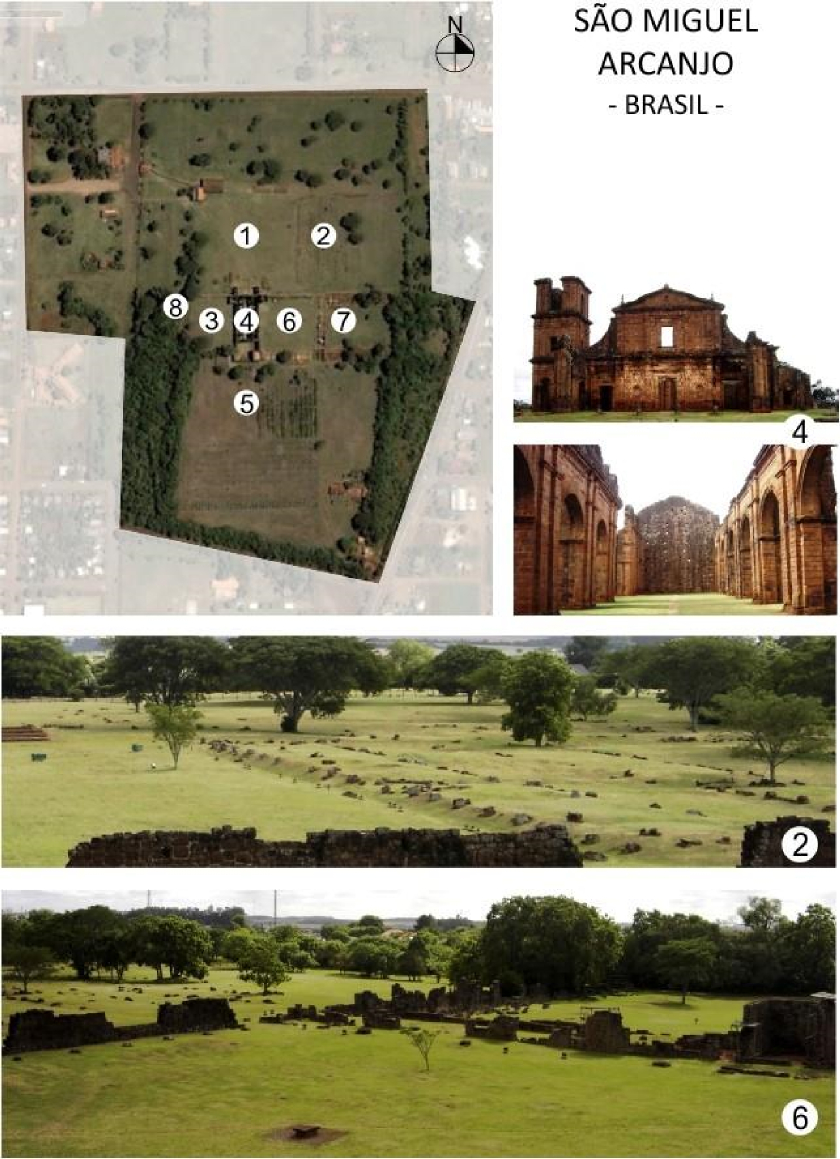

Em janeiro de 2013, foram realizadas visitas técnicas aos três sítios históricos mais bem conservados (São Miguel, no Brasil, Trinidad, no Paraguai, e San Ignácio Miní, na Argentina), a fim de reunir informações sobre as ações governamentais realizadas após a redescoberta das ruínas, dois séculos depois da expulsão dos jesuítas do atual território brasileiro. Com base nesse material, buscou-se compreender as três políticas preservacionistas nacionais em relação aos remanescentes físicos, imateriais e humanos, com especial atenção às atividades de pesquisa, preservação e divulgação.

Em seguida, discutiram-se a representação e a divulgação do patrimônio missioneiro em meio virtual, suas consequências e potencialidades. Em especial, o uso de tecnologias de informação e comunicação (TIC) para organizar a preservação das Missões Jesuíticas e evidenciar seu caráter de sistema vivo. Foram analisados os sites online, suas principais características e seus pontos positivos e negativos.

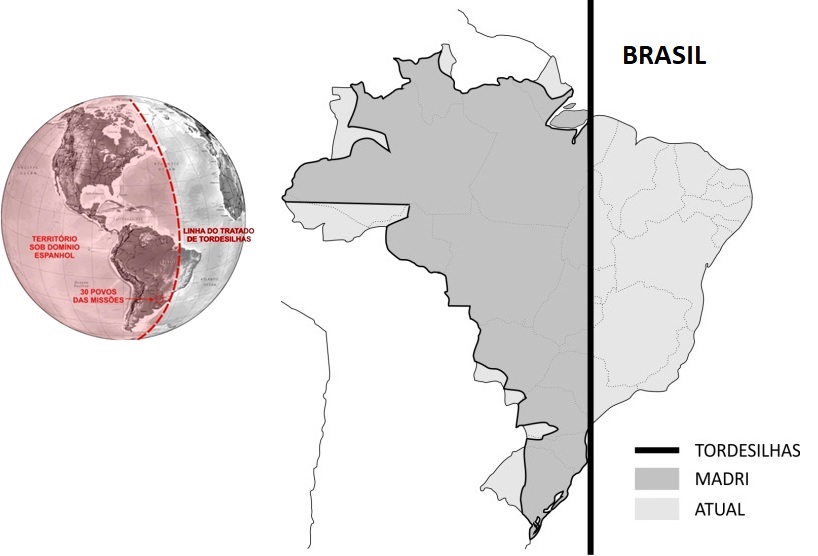

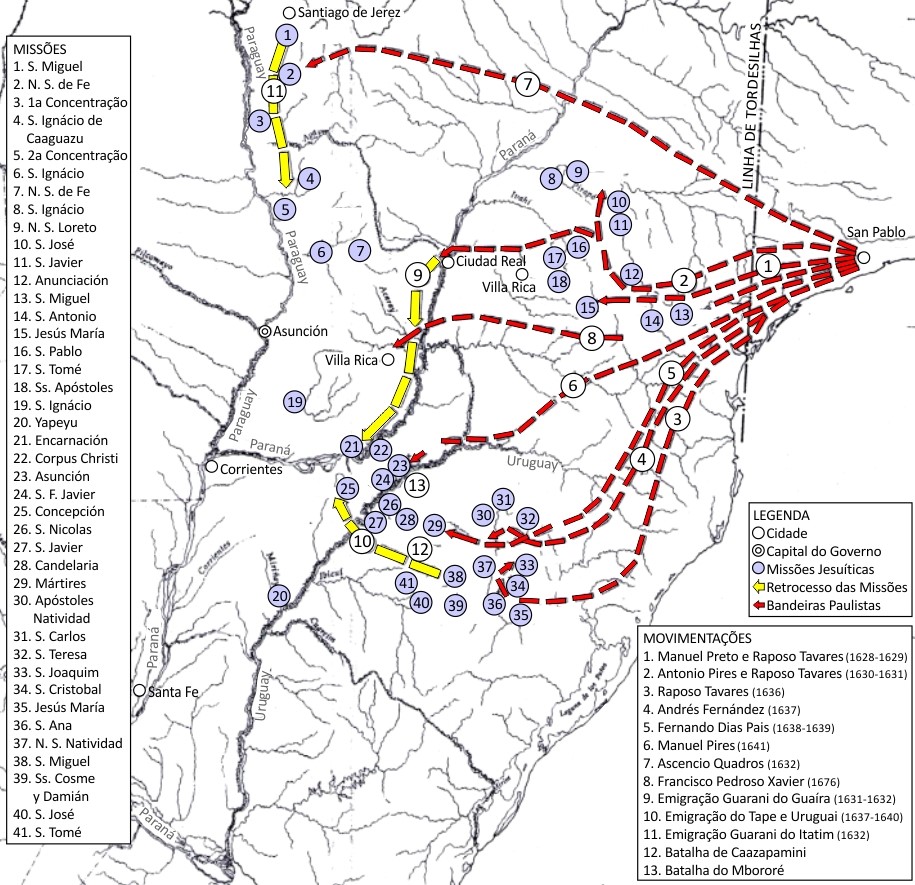

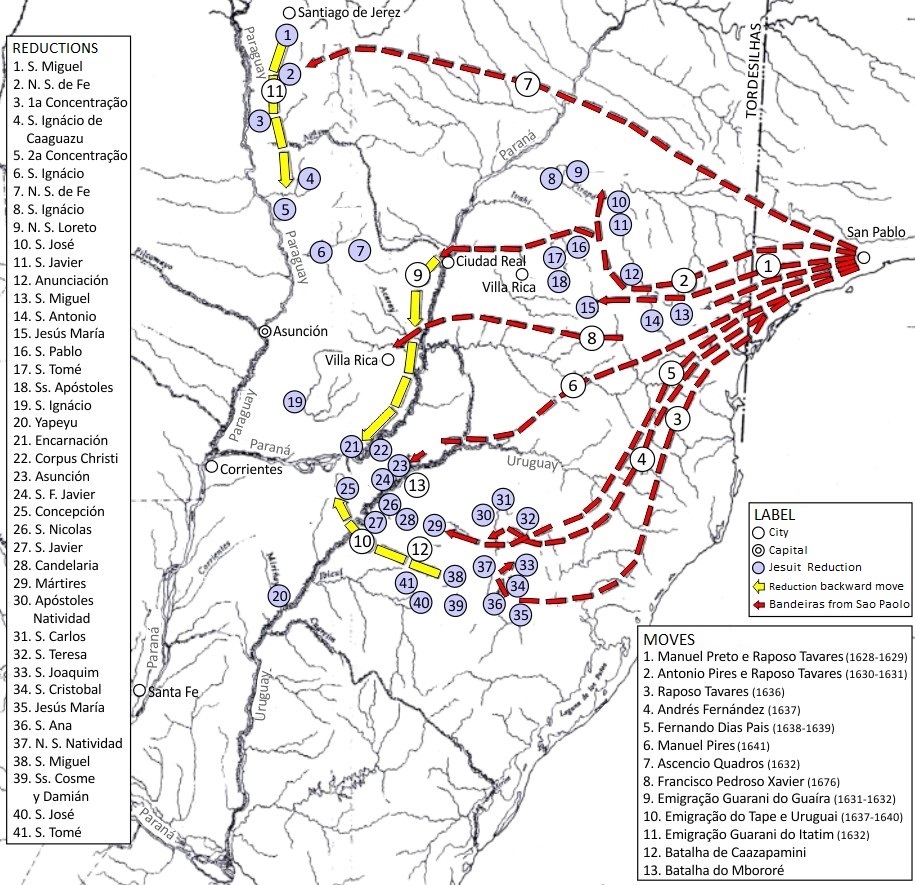

2 Missões Jesuíticas no passado

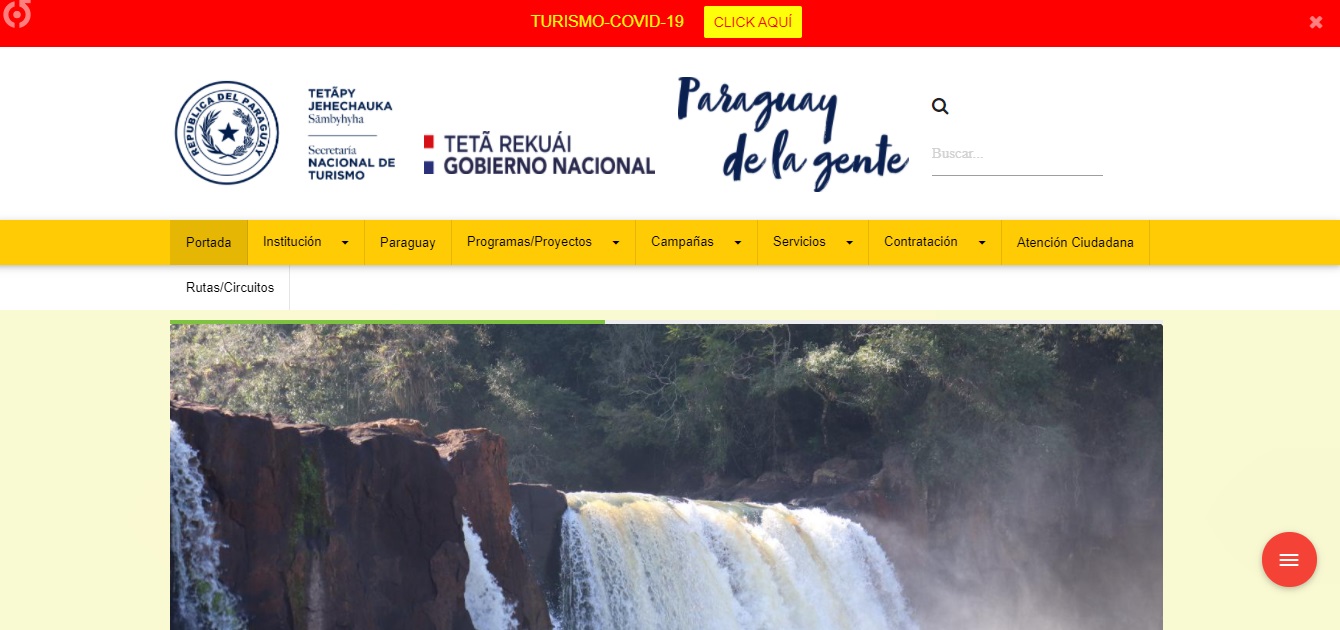

O Brasil foi o único território das Américas a ficar dividido entre as Coroas Portuguesa e Espanhola (Figura 1), resultando em uma colonização marcada por dois fenômenos antagônicos: 1. os padres da Companhia de Jesus, que buscavam a evangelização dos povos indígenas na formação de aldeamentos chamados Missões Jesuíticas; e 2. os bandeirantes paulistas que invadiam o território espanhol para capturar indígenas para escravizá-los (Figuras 2 e 3).

Fig. 1: À esquerda, meridiano do Tratado de Tordesilhas, mostrando o território sob domínio espanhol e a localização dos também chamados Trinta Povos das Missões. À direita: Distribuição do território brasileiro com o Tratado de Madri. Fonte: Compilação com base em Soster (2014).

Fig. 2: As Trinta Reduções Jesuíticas com as fronteiras internacionais atuais. Fonte: Soster (2014).

Fig. 3: Avanços dos bandeirantes e retrocessos dos jesuítas e indígenas. Fonte: Maeder e Gutiérrez (2010, p. 22, tradução, cores e numerações nossas) publicado em Soster (2014, p. 30).

A chegada dos portugueses à costa brasileira ocorreu num período em que os habitantes do continente “Somavam, talvez, 1 milhão de índios, divididos em dezenas de grupos tribais, cada um deles compreendendo um conglomerado de várias aldeias de trezentos a 2 mil habitantes (FERNANDES, 1949). Não era pouca gente, porque Portugal àquela época teria a mesma população ou pouco mais” (RIBEIRO, 1995, p. 31). Por outro lado, as Missões Jesuíticas foram criadas nas Américas para atuar como assentamentos “[...] de limites imperiais ampliados da Coroa da Espanha, que se estenderam – no Novo Mundo – desde a Califórnia e o Novo México até o Rio da Prata.” (GAZANEO, 1997, p. 75, tradução nossa).

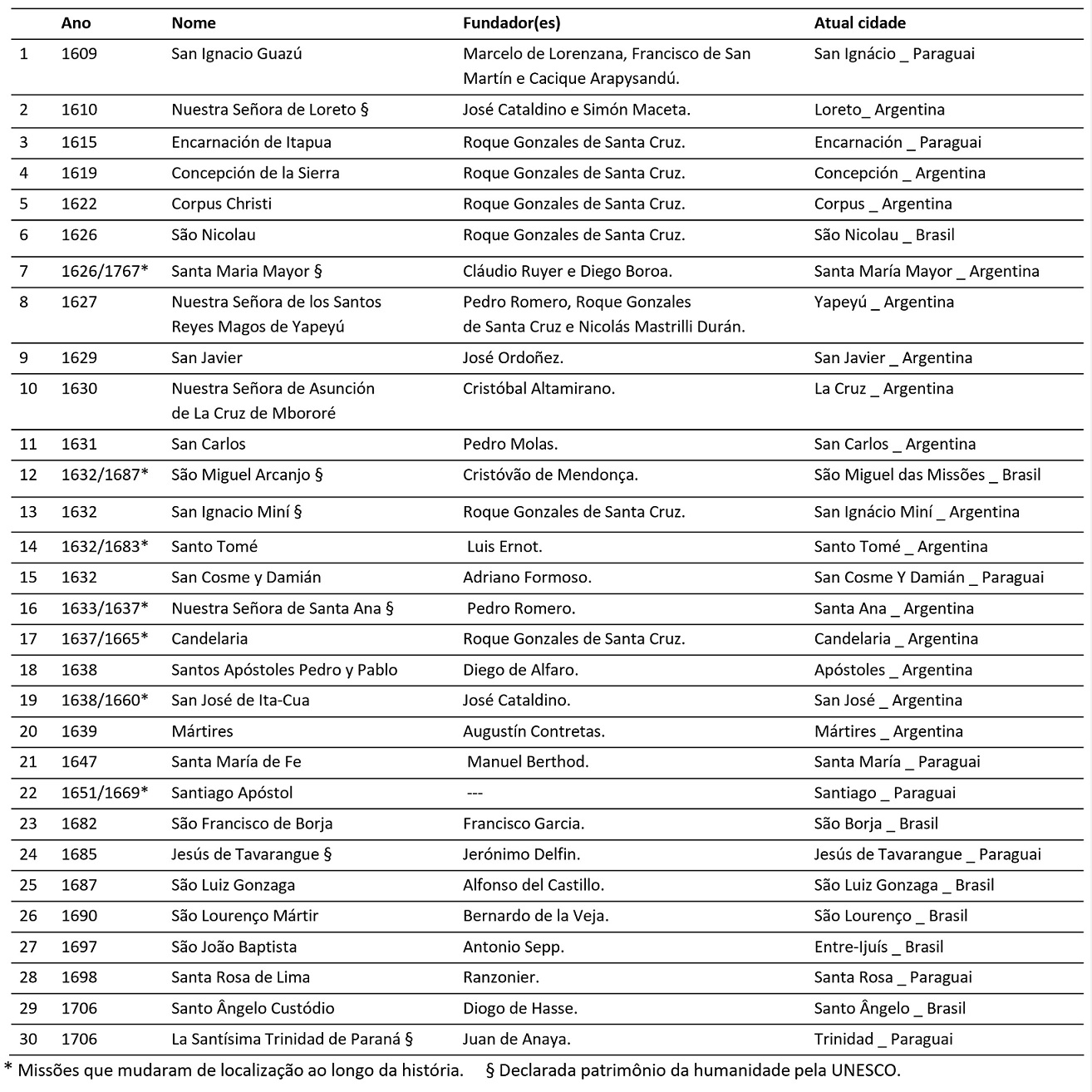

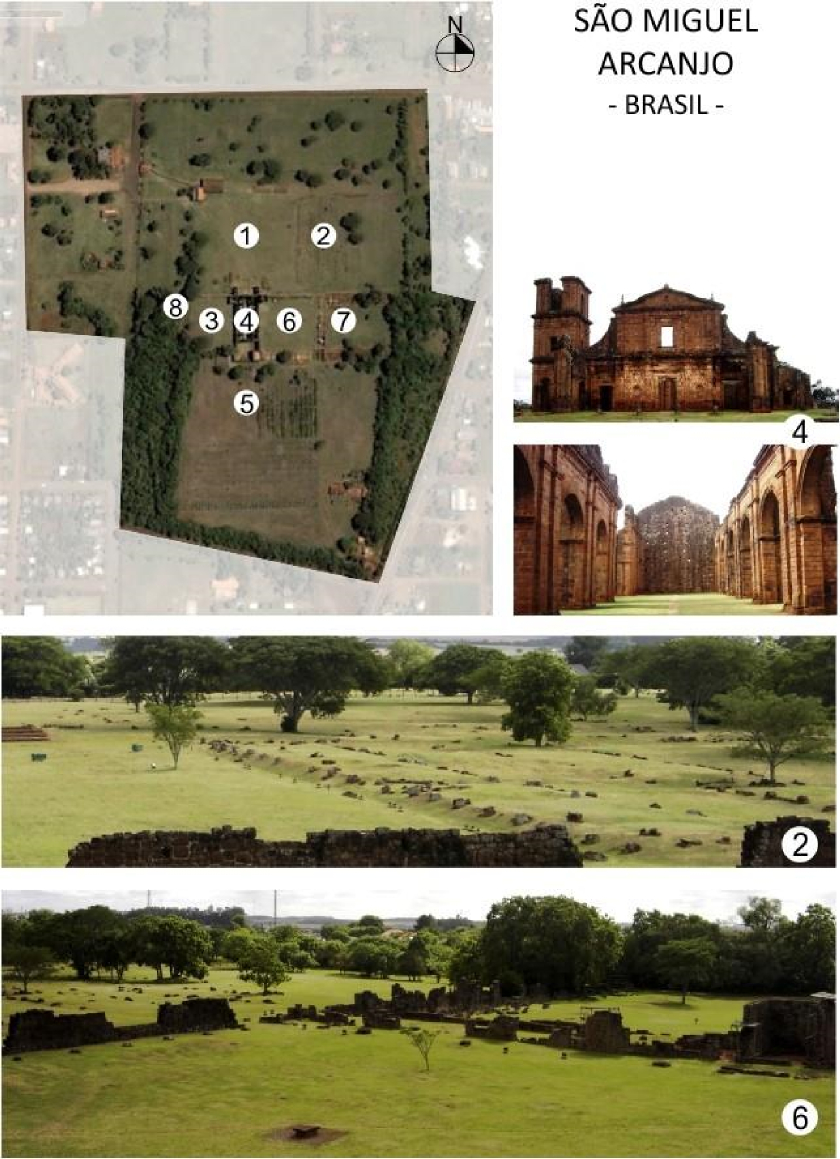

No âmbito político, as Trinta Missões (Quadro 1) buscaram desenvolver a economia local e aumentar a defesa das fronteiras. Segundo os relatos do padre jesuíta Antonio Sepp (1980 [1697], p. 12), “Durante mais de cem anos, os índios dos Trinta Povos combateram, pela Coroa espanhola, em mais de cinquenta batalhas”. Em termos religiosos, os indígenas eram “[...] trazidos para a Igreja Cristã e educados em uma forma sedentária de vida” (UNESCO, 2013, p. 3, tradução nossa).

Quadro 1: Missões Jesuíticas com suas datas de fundação, seus fundadores e atual cidade onde se localizam. Fonte: Soster, 2014, p. 36.

No campo social, o projeto jesuítico poderia ser entendido como uma alternativa para a escravidão (SNIHUR, 2007, p. 236). Segundo o arquiteto Ramón Gutiérrez (2004, p. 17), as Missões Jesuíticas

[...] constituíram uma experiência cultural e social de notável magnitude. Em um período breve, compreendido entre 1610 e 1767, milhares de indígenas formaram dezenas de povoados, organizaram uma economia comunitária e complementar, alcançando elevados níveis de vida, desenvolvimento artístico e cultural. Esta experiência, que transcende os testemunhos materiais que ainda subsistem, configura-se em uma das iniciativas mais claras de desenvolvimento de uma sociedade solidária em uma visão teocêntrica, como a que implantaram os religiosos.

Como afirma o antropólogo argentino Guillermo Wilde (2010), cada uma das Missões Jesuíticas era um espaço religioso, cultural e político, onde ocorreram interações adaptativas individuais e coletivas entre as culturas nativa e espanhola. Este processo recíproco de interação foi marcado profundamente pelo confronto das diferenças culturais e modos de vida. Negociação, concessão e criatividade culminaram em uma terceira cultura: híbrida, miscigenada. O primeiro sistema cultural complexo e transcontinental da modernidade, como afirma Juan Luis Suárez (2007), em um território onde a organização social era muito antagônica à criada. Os Trinta Povos das Missões possuíam uma independência geográfica do governo colonial do território onde se encontravam e, ao mesmo tempo, uma interdependência entre si, caracterizada pelo auxílio mútuo e possibilitada pelo que o embaixador argentino Mario Ibañez (2000, p. 19) chamava de “prodigiosa e eficaz utilização de comunicações e de informação”.

3 Missões Jesuíticas no presente

Uma vez redefinidas as fronteiras, as quinze Missões argentinas foram demolidas, as sete brasileiras ficaram desertas e as oito paraguaias receberam a população exilada das Missões brasileiras (SUSTERIC, 1999, p. 157).

[…] A unidade monolítica territorial, cultural e étnica, que foi característica das Missões, entrou em crise com o advento da expulsão da Companhia de Jesus e depois com os movimentos revolucionários nacionais, nos primeiros anos do século XIX [...].

Desintegração territorial, despovoamento, desorganização política, institucional e administrativa, foram os fatores decisivos que arrastaram os povos ao estado de ruína arquitetônica e urbana. [...] (POZZOBON, 2004, p. 5, tradução nossa2).

Os remanescentes das Missões Jesuíticas foram reduzidos pela ação do tempo e dos homens. A diminuição de moradores provocou a deterioração dos edifícios, por descuido e falta de conhecimento sobre as técnicas de manutenção (SNIHUR, 2007). Alguns sítios deixaram de existir pela pilhagem de materiais de construção, em outros foram construídos e cidades ou estradas sobre suas ruínas. O arquiteto brasileiro Luis Antônio Bolcato Custódio (2014) conta que o governo municipal vendeu o material de São Miguel para que os colonos construíssem suas casas. A missão virou uma verdadeira pedreira, tendo seu material vendido ou roubado. O preço das pedras variava com o nível de detalhamento, sendo mais caras as de melhor acabamento ou com ornamentos. Dois exemplos de edificações construídas com material das missões jesuíticas brasileiras são a Casa em Pedra, em São Nicolau-RS (Figura 4) e a Casa Construída com Material Missioneiro, em Entre-Ijuís-RS (Figura 5), que foi demolida após seu tombamento.

Fig. 4: Casa em Pedra, São Nicolau. Fonte: IPHAE. Disponível em: www.ipatrimonio.org/sao-nicolau-casa-em-pedra/. Acesso em 04 Jun. 2021.

Fig. 5: Casa em Entre-Ijuís construída com material missioneiro [Demolida]. Fonte: Arquivo Digital Iphan Disponível em: www.ipatrimonio.org/entre-ijuis-casa-construida-com-material-missioneiro/. Acesso em 04 Jun. 2021.

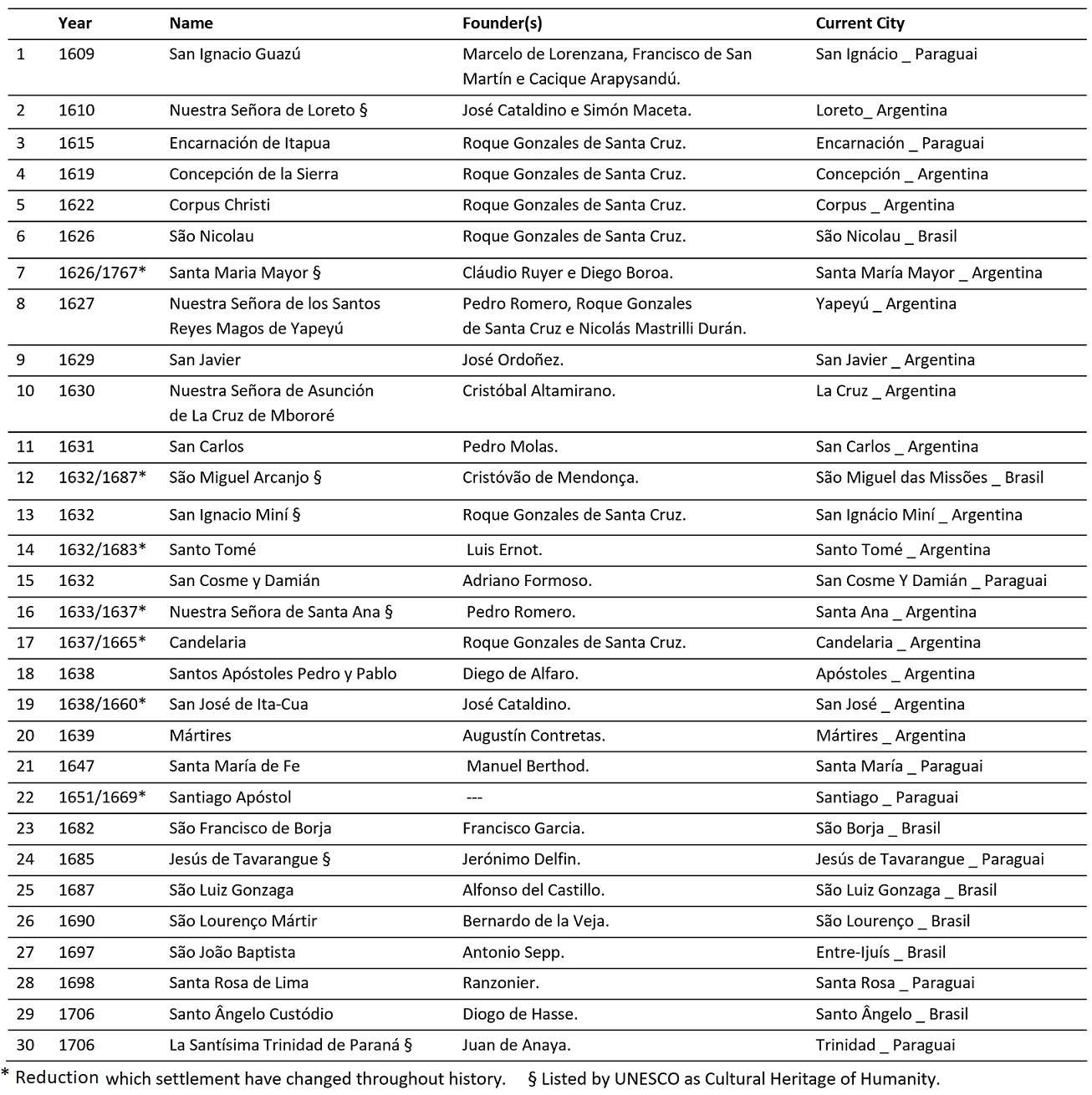

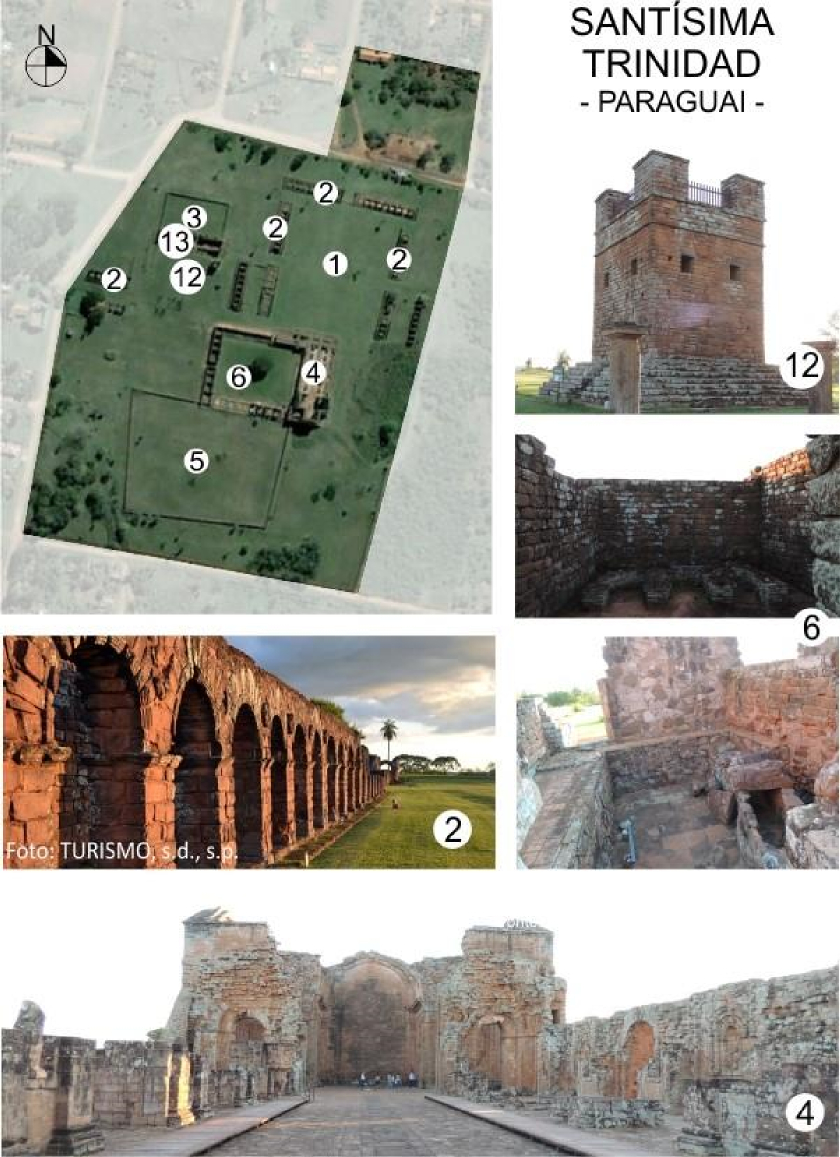

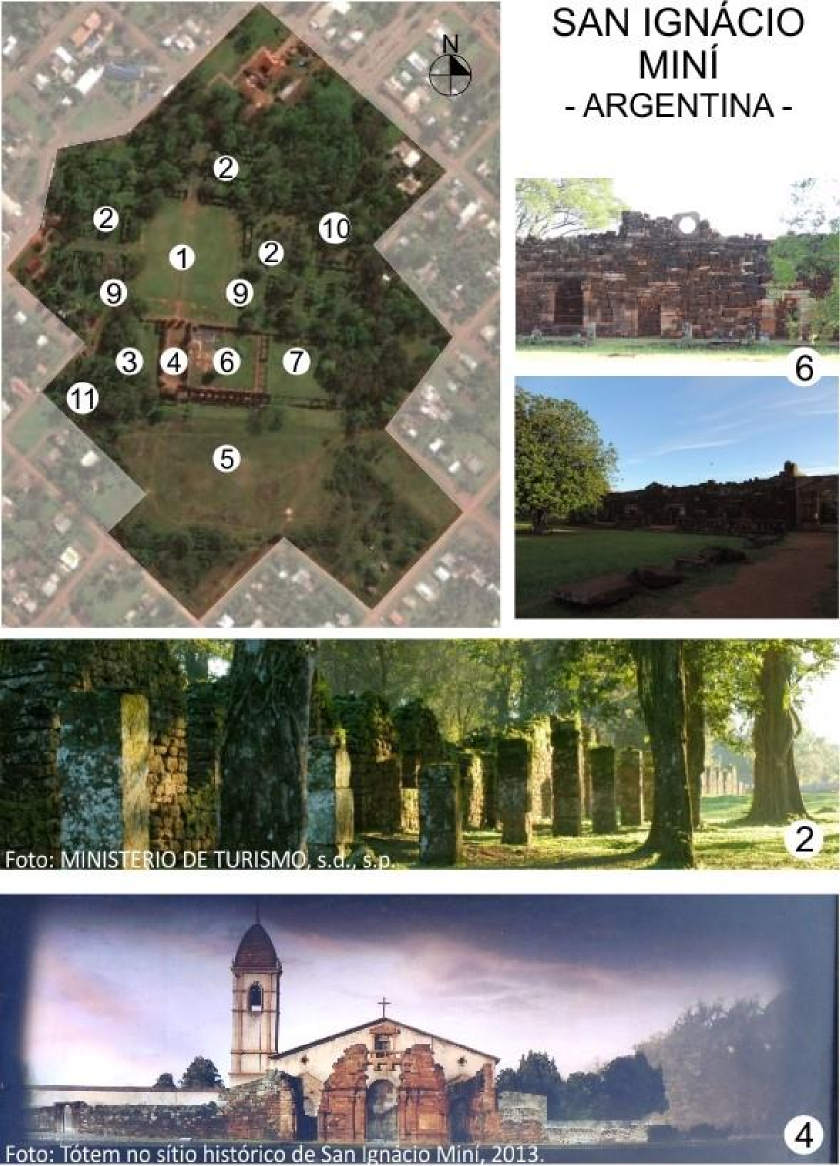

As Missões mais bem conservadas são atualmente São Miguel – Brasil, Trinidad - Paraguai e San Ignácio Miní - Argentina (Figuras 6, 7 e 8). A preservação e percepção estão atreladas a elementos de duas categorias: 1. Patrimônio e 2. Agentes e suas interações. O patrimônio material é todo o acervo físico: ruínas e outros elementos dos sítios (patrimônio imóvel) e obras de arte em museus, principalmente estatuária e instrumentos musicais (patrimônio móvel). Já o patrimônio imaterial é toda cultura e história que permeiam tais objetos. Enquanto isso, os agentes e suas interações envolvem órgãos governamentais responsáveis, pesquisadores, comunidade local e os demais setores da sociedade.

Fig. 6: Ruínas em São Miguel Arcanjo, Brasil: 1. Praça, 2. Marcação das moradias, 3. Cemitério, 4. Igreja, 5. Quinta dos padres, 6. Pátio dos Padres, 7. Pátio das Oficinas, 8. Cotiguaçu. Fonte: Soster, 2014, p. 91.

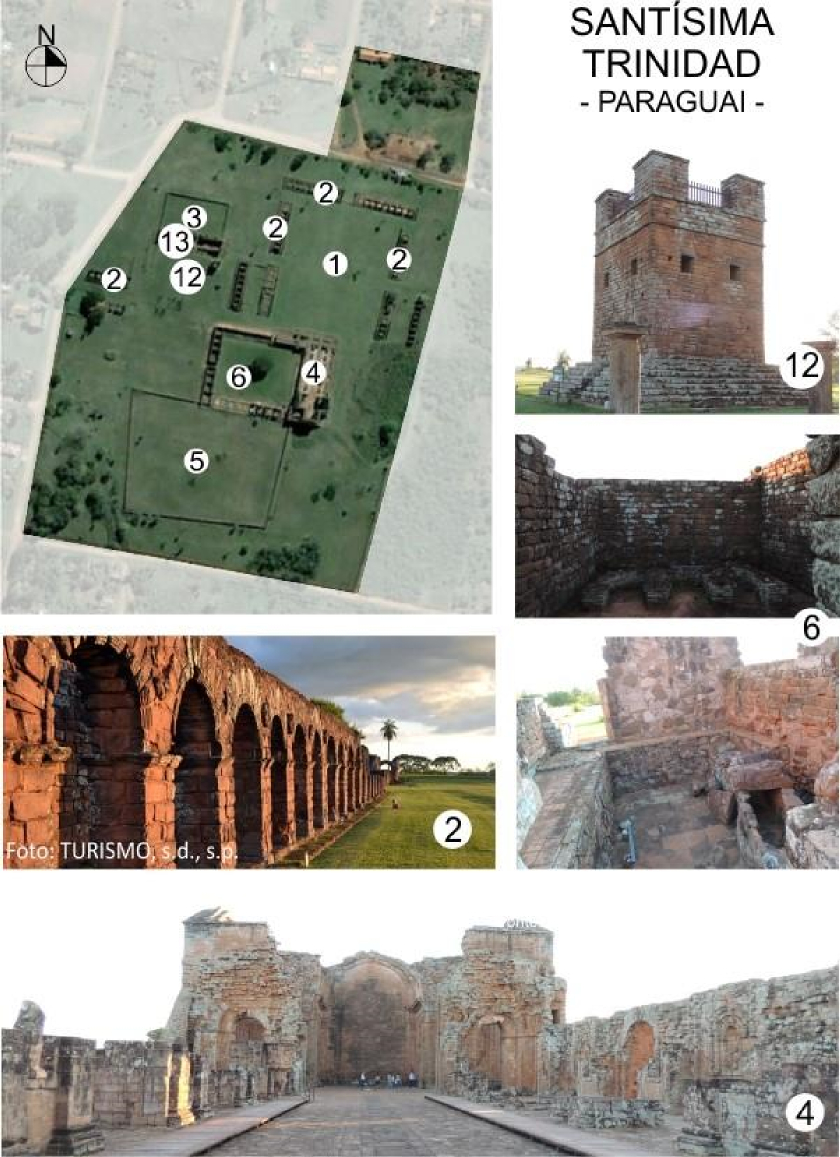

Fig. 7: Ruínas em Santísima Trinidad, Paraguai: 1. Praça, 2. Moradias, 3. Cemitério, 4. Igreja, 5. Quinta dos padres, 6. Pátio dos Padres e das Oficinas, 12. Campanário, 13. Segunda igreja. Fonte: Soster, 2014, p. 92.

Fig. 8: Ruínas San Ignácio Miní – Argentina: 1. Praça, 2. Moradias, 3. Cemitério, 4. Igreja, 5. Quinta dos padres, 6. Pátio dos Padres, 7. Pátio das Oficinas, 9. Cabildo, 10. Cadeia, 11. Hospital. Fonte: Soster, 2014, p. 93.

Os remanescentes arquitetônicos e artísticos e os relatos históricos das Missões nos três países se complementam. Cada sítio histórico é capaz de representar apenas uma parcela da história dos Trinta Povos e da Companhia de Jesus. Portanto, para compor uma visão histórica, social, econômica e cultural da experiência das Missões Jesuíticas, é necessário observá-los em conjunto. O que, por sua vez, demanda ações integradas para a preservação e divulgação dos bens patrimoniais que envolvam todos os agentes; de modo a justificar a permanência deste patrimônio pela apropriação da comunidade local e internacional.

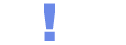

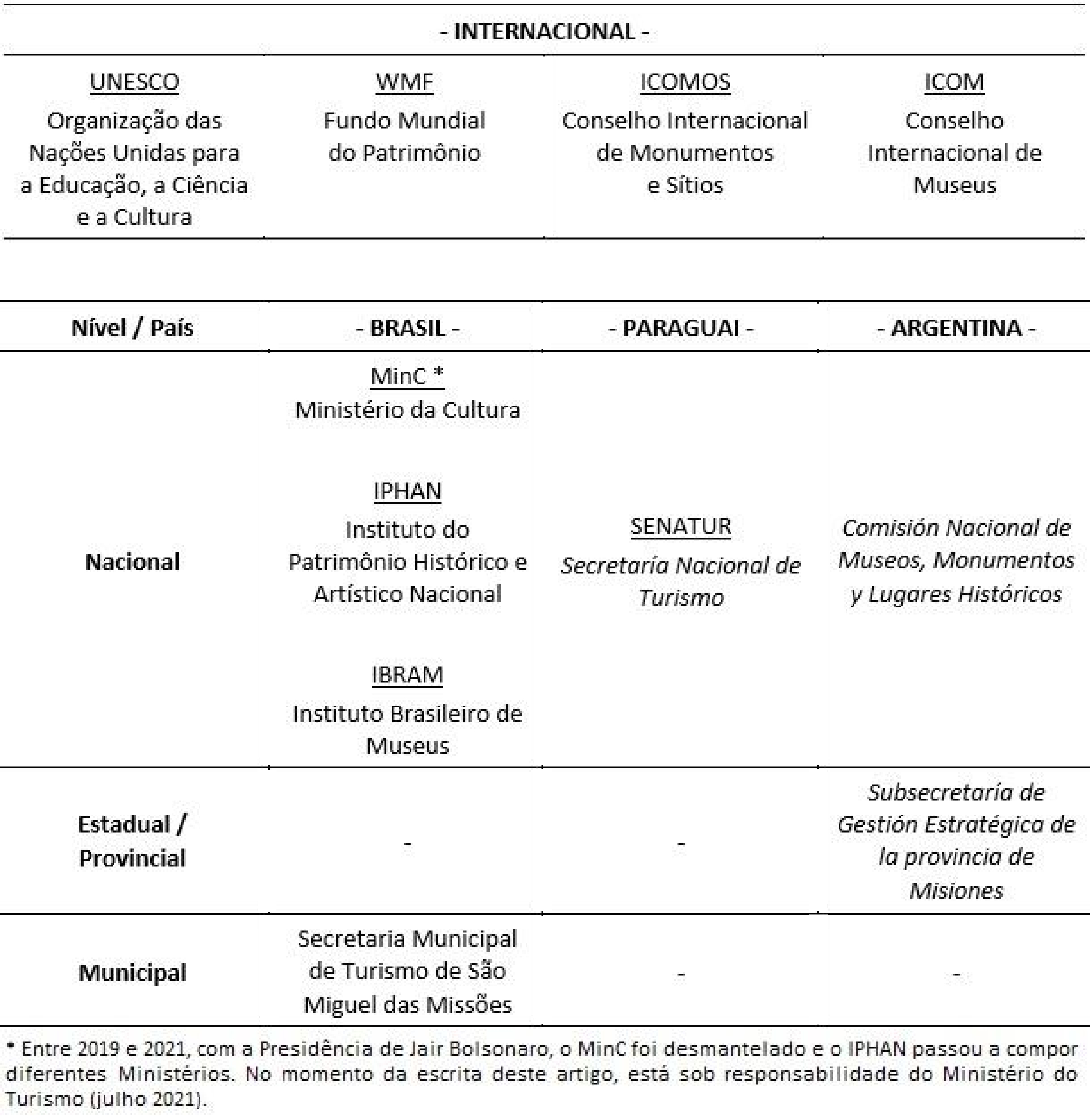

Contudo, em 2014, todas as ações relacionadas às missões jesuíticas eram realizadas por cada nação de modo individual, sob responsabilidade de níveis governamentais distintos, conforme Quadro 2. Inclusive a produção de conhecimento dentro das universidades não é compartilhada com os órgãos de preservação. O que demonstra a pouca interação entre órgãos governamentais entre si e com os pesquisadores.

4 Missões Jesuíticas Online

No contexto da divulgação do patrimônio remanescente das Missões Jesuíticas, entende-se que as tecnologias de informação e comunicação (TIC) seriam de baixo custo, e de grande rapidez e eficiência. Contudo, são pouco utilizadas. Tanto o levantamento em 2014 quanto pesquisa atual demonstraram que a maioria do conteúdo disponível online sobre as Missões Jesuíticas se encontra em blogs que retratam viagens pessoais a esses sítios. Portanto, não são informações de fontes oficiais, que não têm aproveitado o enorme potencial das mídias online. Os websites oficiais disponibilizados à época possuíam dois níveis de abrangência: global e local.

A UNESCO disponibiliza duas páginas sobre as Missões incluídas na Lista do Patrimônio da Humanidade. Uma sobre as tombadas por leis de preservação em 1983 (Argentina - San Ignácio Miní, Santa Ana, Nuestra Señora de Loreto, Santa Maria Mayor - e Brasil - São Miguel) e outra sobre as tombadas por leis de preservação em 1993 (Paraguai - La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná e Jesús de Tavarangue). Ambas reúnem informações sobre história e implantação, e fotografias, além de disponibilizarem links para os relatórios de conservação e preservação.

No Brasil, o IPHAN hospeda em seu portal uma página sobre São Miguel, contendo histórico, estado de conservação e atuação do IPHAN. Também existe o portal da Rota das Missões (www.rotamissoes.com.br - Figura 9), que talvez tenha sido a página melhor estruturada. Tais portais são mais voltados para a divulgação turística da região, com poucas informações sobre a história e a cultura missioneiras.

Fig. 9: Divulgação online brasileira no portal Rota das Missões. Fonte: Rota das Missões. Disponível em: www.rotamissoes.com.br Acesso em: 04 jun. 2021.

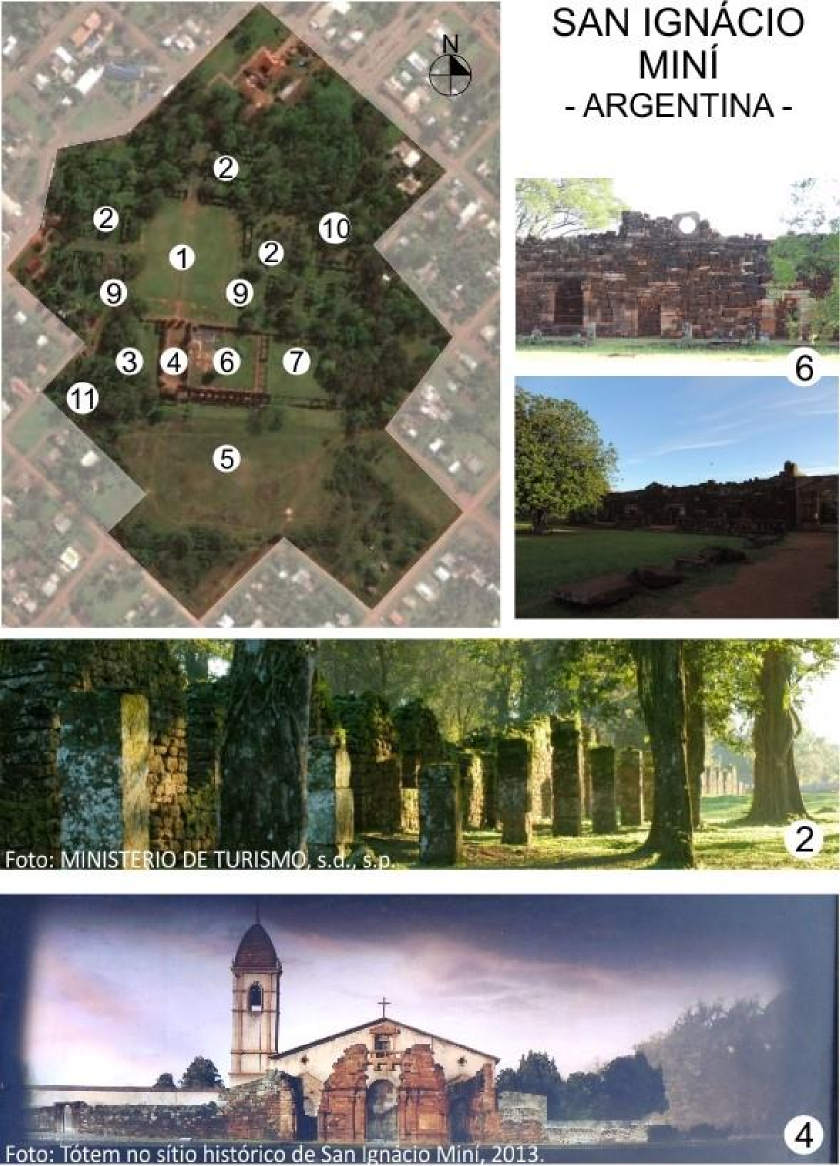

No Paraguai, o portal da SENATUR (www.senatur.gov.py - Figura 10) apresentava, em 2014, material sobre as Missões Jesuíticas em três páginas relacionadas ao turismo: uma sobre turismo aos sítios históricos e festividades; outra sobre a região de Misiones, Itapúa y Ñeembucú, com localização e principais atrativos turísticos locais; e outra sobre os Museos y Monumentos nacionais. As páginas possuíam um viés de divulgação turística. Em pesquisa atual, tais páginas não foram encontradas.

Fig. 10: Divulgação online paraguaia no portal da SENATUR. Fonte: SENATUR. Disponível em: www.senatur.gov.py Acesso em: 04 jun. 2021.

Sobre as Missões Jesuíticas paraguaias, também o portal “Ruta Jesuítica: Descubrí los Patrimonios Universales de Paraguay” (rutajesuitica.com.py - Figura 11) continua sendo o mais completo e único com apresentação visual inspirada nas Missões Jesuíticas. Também possui caráter turístico e foi criado através de parceria entre a SENATUR e os governos dos Departamentos de Misiones, Itapúa e Alto Paraná, com apoio da UNESCO e do BID. O conteúdo é organizado por departamento e, dentre os atrativos turísticos, estão os povoados jesuíticos, cada um com página própria com informações sobre remanescentes móveis e imóveis. Disponibiliza o conteúdo mais bem organizado, facilitando a aquisição de um conhecimento mínimo sobre o patrimônio missioneiro deste país.

Fig. 11: Divulgação online paraguaia no portal Ruta Jesuítica. Fonte: Ruta Jesuítica. Disponível em: rutajesuitica.com.py Acesso em: 04 jun. 2021.

Na Argentina, em 2014, havia um portal do governo específico para as Missões Jesuíticas Guaranis (www.misiones-jesuiticas.com.ar – Figura 12), que era o mais completo dentre todos, pois apresentava informações sobre: 1. localização, visitação pública, aeroportos disponíveis; 2. Fotografias; 3. história missioneira com introdução, localização e organização espacial das Trinta Reduções; 4. Espetáculos de luz e som; e 5. Programa Misiones Jesuíticas de restauração, conservação e divulgação das Missões argentinas. Também existia um site da Província de Misiones (www.turismo.misiones.gov.ar/sanignacio.php - Figura 13) com informações sobre a preservação de San Ignácio Miní. Em pesquisa atual, ambos já não estão online.

Fig. 12: Divulgação online argentina no portal Misiones Jesuíticas Guarani. Fonte: Misiones Jesuíticas Guarani. Disponível em: www.misiones-jesuiticas.com.ar Acesso em: 04 jun. 2014.

Fig. 13: Divulgação online argentina no portal do Ministério do Turismo da Província de Misiones. Fonte: Ministério do Turismo da Província de Misiones. Disponível em: www.turismo.misiones.gov.ar/sanignacio.php Acesso em: 04 jun. 2014.

Conclui-se que os poucos sites existentes tratam de questões turísticas de Missões Jesuíticas isoladas ou dos grupos nacionais, havendo carência de plataformas online com informações sobre o conjunto. As páginas que se mantiveram online desde 2014 aprimoraram seu conteúdo e sua estética ao longo do tempo. Se em 2018 a maioria delas não possuía identidade visual própria por estarem hospedadas em sites dos órgãos nacionais; atualmente (2021), a afirmação não é mais verdadeira. Por seu caráter turístico em vez de histórico-acadêmico, cada site apresenta informações básicas sobre a história e a cultura missioneiras. No geral, a educação patrimonial fica prejudicada pela dispersão e incompletude das informações; o que afeta a valorização e a apropriação do conjunto.

O uso das TIC para organizar e evidenciar questões, necessidades e ações relacionadas às Missões Jesuíticas poderia fazer com que fossem tratadas como um sistema vivo, onde as interações entre os agentes e deles com o patrimônio ocorresse de modo efetivo e justificasse sua preservação em âmbito glocal. Acredita-se que é necessário retomar o sentido de rede do conjunto chamado de Trinta Povos das Missões, por meio de ações integradas de preservação e divulgação de todo o patrimônio missioneiro como o conjunto que compõem. Este é um dos caminhos possíveis para seu fortalecimento como patrimônio único da Humanidade, assim como foi a experiência nelas desenvolvida pelos jesuítas.

5 Revisão de estratégias e proposta para o futuro

Em 2014, ao final da pesquisa, propôs-se a criação de um espaço virtual para o tratamento inter-regional desse patrimônio, onde os agentes governamentais, acadêmicos e de outros setores da sociedade (envolvidos em pesquisa, conservação e divulgação desse patrimônio) pudessem trabalhar de maneira colaborativa. Uma abordagem que atuasse como

[...] uma base de dados integradora de vários centros, patrimônios arquitetônicos e museus. Buscando manter vivas as dinâmicas culturais da comunidade, a preservação e o acesso físico e virtual a tais patrimônios, contribuem para a valorização das culturas tradicionais, e reforçam o sentimento de pertencimento e de identidade, garantindo consequentemente a permanência desse patrimônio para as futuras gerações (PRATSCHKE; SANTIAGO, 2006, p. 1).

Dentre as opções atuais de plataformas digitais, como apontado pela arquiteta brasileira Ana Cecília Rocha Veiga (2018), o WordPress se mostra um ambiente web para desenvolvimento de uma museologia virtual. O que pode ser direcionado ao caso das Missões Jesuíticas por se tratar de conteúdo de caráter similar. Algumas das principais vantagens apontadas pela autora são: 1. gratuito e de código aberto; 2. atualização do código pela comunidade mundial; 3. interface intuitiva e editor de conteúdo amigável; 4. web semântica e taxonomia; e 5. ferramenta de gestão e testes de usabilidade. Segundo ela, 31% dos sites da Internet em 2018 foram desenvolvidos em WordPress.

Um caso que demonstra a potencialidade do WordPress na área do patrimônio cultural é a plataforma iPatrimônio (www.ipatrimonio.org), criada para georreferenciar informação sobre todos os bens tombados no Brasil, nas quatro instâncias: mundial, nacional, estaduais e municipais. O trabalho de alimentação realizado pela primeira autora deste artigo possibilitou o entendimento de que as bases de dados dos órgãos oficiais são incompletas e as buscas em seus sites são ineficientes. Além disso, a população carece de canal de comunicação especializado, ágil e que entregue a informação solicitada em linguagem acessível ao grande público.

Dessa forma, entende-se que existem possibilidades para ampliar a divulgação das Missões Jesuíticas como o conjunto que compuseram. Mas, para isso, é necessária a abertura dos órgãos de preservação das três nações para o trabalho conjunto entre si e com universidades e comunidades locais.

6 Considerações finais

No passado, as Missões Jesuíticas formaram um todo complexo: uma sociedade solidária de auxílio mútuo no interior dos aldeamentos e entre eles. No presente, seu entendimento está prejudicado porque seus vestígios foram afetados e reduzidos por guerras, pela ação do tempo e da mão do ser humano. Portanto, é preciso olhar para o conjunto para compreender a experiência histórica. Ou seja, considerar a preservação como um sistema é necessário inclusive pelo caráter fragmentado de seu patrimônio. Contudo, a divisão atual em três nações distintas levou à preservação e divulgação de modo separado ou em grupos nacionais, desfigurando a rede que marcou durante mais de um século as Missões Jesuíticas. A informação online é pontual e nacional, direcionada para o aspecto turístico. Mesmo apesar da redução do número de sites entre 2014 e 2018, a qualidade visual dos sites e da informação disponibilizada entre 2018 e 2021 aumentou.

Acredita-se que um fluxo melhorado de informações, a divulgação sem limites geográficos e a disponibilização de canais de comunicação entre os agentes promoveriam um melhor entendimento das Missões Jesuíticas e fariam com que sua função social de suporte da memória e base de reflexão histórica e social seja maximizada. Em outubro de 2018, uma rota integrada das Missões Jesuíticas entre Brasil, Argentina, Uruguai, Paraguai e Bolívia foi aprovada pelo Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento (BID), perpassando 19 ícones reconhecidos pela Unesco como patrimônios da Humanidade (BERGAMO, 2018). O que demonstra a atenção internacional, via Unesco, para a importância do conjunto das Missões Jesuíticas. Com isso, espera-se que o trabalho integrado ocorra entre os vários países que são guardiões desse importante patrimônio.

Agradecimentos

Nosso agradecimento ao apoio financeiro da Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), essencial para a realização dessa pesquisa.

Referências

BERGAMO, M. BID aprova rota entre Brasil, Argentina, Uruguai, Paraguai e Bolívia: O caminho conecta 19 ícones da história da colonização jesuítica na região. Folha de São Paulo, 20 Out. 2018 [Online] Disponível em: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/monicabergamo/2018/10/bid-aprova-rota-entre-brasil-argentina-uruguai-paraguai-e-bolivia.shtml?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=compfb. Acesso em: 04 Jun. 2021.

CUSTÓDIO, L. A. B. Participação em banca de Sandra Schmitt Soster. Missões jesuíticas como sistema. 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado em Teoria e História da Arquitetura e do Urbanismo) – Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo – Universidade de São Paulo, São Carlos-SP.

GAZANEO, J. O. The geopolitics of the missions. In: UNESCO; ICOMOS (Orgs.). The Jesuit missions of the Guarani. Verona: Commercial Bureau, 1997, p. 74-89.

GUTIÉRREZ, R. As Missões Jesuíticas dos Guaranis: um espaço para a utopia. In: World Monuments Fund (Org.). Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani: programa de capacitação para conservação, gestão e desenvolvimento sustentável das Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani. World Monuments Fund: Brasília, 2004, p. 17-18.

IBAÑEZ, M. C. Misiones Jesuíticas brasileñas. In: MUSEO DE ARTE HISPANOAMERICANO ISAAC FERNÁNDEZ BLANCO (Org.). Misiones Jesuíticas brasileñas. Buenos Aires: Museo de arte hispanoamericano Isaac Fernández Blanco, 2000, p. 19-21.

MAEDER, E. J. A.; GUTIÉRREZ, R. Atlas territorial e urbano das missões jesuíticas dos guaranis: Argentina, Paraguai e Brasil. Sevilha: Junta Andalucia; Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico; Consejería de Cultura, 2010.

POZZOBON, J. L. Misiones: las reducciones jesuiticas. In: World Monuments Fund (Org.). Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani: programa de capacitação para conservação, gestão e desenvolvimento sustentável das Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani. World Monuments Fund: Brasília, 2004, CD.

PRATSCHKE, A.; SANTIAGO, R. P. Olhares múltiplos, ou como conceber um espaço de conhecimento para a cidade de São Carlos. In: SIGRADI, 10., 2006, Santiago de Chile. Post Digital, v. 1. Santiago de Chile: Universidad de Chile, 2006, p. 377-380. [online]

RIBEIRO, D. O povo brasileiro: a formação e o sentido do Brasil. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1995.

SEPP, A. Introdução. In: SEPP, A. Viagem às Missões Jesuíticas e trabalhos apostólicos. Coleção De Angelis. São Paulo: Itatiaia / Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1980, p. 5-15. Escrito em 1697.

SNIHUR, E. A. O universo missioneiro guarani. um território e um patrimônio. Buenos Aires: Golden Company, 2007.

SOSTER, S. S. Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema. 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo, São Carlos, 2014.

SUÁREZ, J. L. Hispanic Baroque: a model for the study of cultural complexity in the Atlantic world. South Atlantic Review, n. 72, v. 1, p. 31-47, 2007. [online]

SUSTERSIC, B. D. The religious imagery and cultural heritage. In: UNESCO; ICOMOS (Orgs.). The Jesuit missions of the Guarani. Verona: Commercial Bureau, 1997, p. 155-185.

UNESCO. Jesuit Missions of La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue. 2013. [online] Disponível em: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/648. Acesso em: 04 Jun. 2021.

VEIGA, A. C. R. Museus Virtuais em WordPress. In: WORDCAMP, 2018, São Paulo.

WILDE, G. Interpretações históricas e atuais da experiência jesuítica. Entrevistadora: Patricia Fachin. Trad. Moisés Sbardelotto. IHU on-line – Revista do Instituto Humanitas Unisinos, n. 348, ano 10, 25 Out. 2010. [online]

1 SOSTER, S. S.; PRATSCHKE, A. Missões jesuíticas como sistema: revisão de estratégias e propostas para o futuro. In: Seminário Internacional sobre Preservação Cultural no Território Trinacional, 1., 2018, Foz do Iguaçu. Anais... Foz do Iguaçu: UNIOESTE, 2018. v. 1.

2 Do original em espanhol: “[…] La monolítica unidad territorial, cultural y étnica, que fue característica de Misiones, hizo crisis con el advenimiento de la expulsión de la Compañía de Jesús y luego con los movimientos revolucionarios nacionales, en los primeros años del siglo XIX. […] // Desintegración territorial, despoblación, desorganización política, institucional y administrativa, fueron los factores decisivos que arrastraron a los pueblos al estado de ruina arquitectónica y urbana. […]”.

Jesuit Reductions as a System: A necessary review

Sandra Schmitt Soster is an Advertiser, Architect and Urban Planner, and has a Master's Degree in Architecture and Urbanism. She is a researcher at Nomads.usp, at LabAm-UFG, and at LavMuseus-UFMG. She is a member of the ICOMOS-Brasil Documentation, Risk Preparation, and Interpretations, Education and Heritage Narratives Committees, as well as of iPatrimônio and REPEP. She studies digital media for cultural heritage management, heritage education, and participatory inventories. soster.heritage@gmail.com http://lattes.cnpq.br/9177354683297726

Anja Pratschke is an Architect, Doctor in Computer Science and Livre-docente in Architecture and Urbanism. She is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, and the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism of the same institution. She co-directs Nomads.usp, and she develops and guides research on design processes in architecture, cybernetics, and information organization. pratschke@sc.usp.br http://lattes.cnpq.br/9669955733350604

How to quote this text: Soster, S. S.; Pratschke, A., 2021. Jesuit Reductions as a System: A necessary review. Translated from Portuguese by Anja Pratschke and Marcelo Tramontano. V!RUS, 22, July. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus22/?sec=6&item=1&lang=en>. [Accessed: 10 July 2025].

INVITED AUTHORS

Abstract

Part of this article was originally presented at the 1st International Seminar on Preservation of Cultural Heritage in the Trinational Territory, in 2018. The theme of V!RUS 22, “Latin America: You Are Here!”, is an opportunity to re-introduce results of the master's research “Jesuit Reductions as a System”, developed at the Nomads.usp and funded by the Sao Paulo State Agency for Research Funding, FAPESp.The thesis was defended in 2014 in the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism, Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, University of São Paulo. To understand the historical importance of the series of Thirty Jesuit Reductions of the former Jesuit Province of Paraguay, the research carried out three chronological sections. 1. the beginning of the reductions, when they were a set of mutual assistance; 2. the present, when the material and immaterial remnants preserve regional memory and history, but the separation by international borders is at the origin of the lack of communication between the responsible national bodies and the little online dissemination of relevant and official information; and 3. the future, identifying that regionally integrated dissemination and preservation can enhance the understanding and appreciation of the jesuit reductions, including greater ownership of local communities. We understand that valuing the reductions heritage supposes to stimulate preservation agencies to work together and most of all, with local communities.

Keywords: Jesuit reductions, System, ICT, Latin America

1 Introduction

This article has been originally presented at the 1st International Seminar on Preservation of Cultural Heritage in the Trinational Territory, in 20181. The results presented here stem from a master's research “Jesuit Reductions as a System”, developed at the Nomads.usp and funded by the Sao Paulo State Agency for Research Funding, FAPESp.The thesis was defended in 2014 in the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism, Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, University of São Paulo, Brazil. (Soster, 2014). A brief Internet search in June 2021 shows a growing international academic interest in the Jesuit Missions. This interest includes the review of intercultural aspects and the role of the Jesuit Missions in South America, in particular the former thirty original settlements that formed the Province of Paraguay, today distributed in the territories of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, along the Iguaçu River.

The historical experience of the Jesuit reductions of the former Province of Paraguay was analyzed in the master's research, based on bibliographical references. The time frame comprises the period between the implementation of the Jesuit reductions by the Society of Jesus (1549) and its violent expulsion due to the displacement of the dividing line between the Portuguese and Spanish territories (Treaty of Madrid, 1750). As a network of settlements connected by deep political, economic, and religious relationships, they were analyzed seeking to emphasize their complementarity as a set for mutual assistance. However, different reasons prevented the production of individual surpluses, and economic assistance between them never occurred. The Jesuit model was a mode of cultural imposition or domination over originary peoples and was not completely peaceful. On Portuguese territory (as on Spanish territory reached by the Portuguese flags), this model meant at the time the option of less physical violence compared to capturing for slavery.

In January 2013, technical visits were carried out to the three best-preserved historic sites – São Miguel, in Brazil, Trinidad, in Paraguay, and San Ignácio Miní, in Argentina. The goal was to gather information on administrative actions following the rediscovery of the ruins, two centuries after the expulsion of the Jesuits from the current Brazilian territory. Based on this material, we sought to understand the three national preservation policies concerning physical, immaterial, and human remains, with special attention to research, preservation, and dissemination activities. The representation and dissemination of the reductions heritage in a virtual environment, its consequences, and potential were then discussed. In particular, the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to organize the preservation of the Jesuit Reductions and demonstrate their character as a living system. Websites were analyzed, following their main features and their positive and negative points.

2 Jesuit Reductions in the past

The territory of Brazil was the only one in the Americas that was divided between the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns (Figure 1), whose colonization was marked by two antagonistic phenomena: 1. the priests of the Society of Jesus, who sought the evangelization of indigenous peoples to create the villages called Jesuit Reductions; and 2. the so-called bandeirantes, from Sao Paulo, literally the "flag-carriers", that used to invade the Spanish territory to capture indigenous people for enslaving them (Figures 2 and 3).

Fig. 1: Left: The Treaty of Tordesillas meridian, showing the territory under Spanish rule and the location of the also so-called Trinta Povos das Missões. Right: Brazilian territory after the Treaty of Madrid. Source: Compilation based on Soster, 2014.

Fig. 2: The Thirty Jesuit Reductions situation with present day countries boundaries. Source: Soster (2014).

Fig. 3: Bandeirantes advances and Jesuits and indigenous peoples setbacks. Source: Maeder and Gutiérrez (2010, p.22, our translation, colors, and numbers) quoted by Soster (2014, p.30).

The arrival of Portuguese people to the Brazilian coast took place at a time when the inhabitants of the continent “[…] were perhaps 1 million Indians, divided into dozens of tribal groups, each comprising a conglomerate of several villages with between three hundred and two thousand inhabitants (Fernandes, 1949). It was not a few people, since Portugal at that time would have the same population or a little more” (Ribeiro, 1995, p.31, our translation). On the other hand, Jesuit Reductions were created in the Americas to be settlements “[...] the extended imperial borders of the Crown of Spain, which stretched – in the New World – from California and New Mexico to the River Plate.” (Gazaneo, 1997, p.75).

In the political sphere, the Thirty Reductions (Table 1) sought to develop local economy and increase border defense. According to the reports of the Jesuit Father Antonio Sepp (1980 [1697], p.12), “For over a hundred years, the Indians of the Thirty Reductions fought, for the Spanish Crown, in more than fifty battles”. In religious terms, indigenous people were “[...] they would be brought into the Christian Church and educated into a sedentary form of life” (UNESCO, 2013, p.3).

Table 1: Jesuit Reductions with their foundation dates, their founders and current city where they are located. Source: Soster, 2014, p.36.

In the social field, the Jesuit project could be understood as an alternative to slavery (Snihur, 2007, p.236). According to the architect Ramón Gutiérrez (2004, p.17, our translation), the Jesuit Reductions

[...] were a cultural and social experience of remarkable magnitude. In a brief period, comprised between 1610 and 1767, numbers of indigenous people formed dozens of villages, organized a community and complementary economy, reaching standards of living, artistic and cultural development. This one, which transcends the material testimonies that still exist, is one of the clearest initiatives for the development of a solidary society in a theocentric vision, such as the one implemented by the religious experience.

As Argentine anthropologist Guillermo Wilde (2010) states, each of the Jesuit Reductions was a religious, cultural, and political space, where individual and collective adaptive interactions between native and Spanish cultures took place. This reciprocal interaction process was defined by the confrontation of cultural differences and ways of life. Negotiation, concession, and creativity culminated in a third culture: hybrid, mixed. The first complex and transcontinental cultural system of modernity, as stated by Juan Luís Suárez (2007), in a territory where a social organization was very antagonistic to the servant. The Thirty Reductions Peoples were independent from local colonial governments and at the same time, interdependent from each others, in a mutual assistance manner made possible by what the Argentine ambassador Mario Ibañez (2000, p.19) called “prodigious and efficient use of communication and information”.

3 Jesuit Reductions in the present

As soon as borders were redefined, the fifteen Argentine reductions were demolished, the seven Brazilian ones were abandoned, and the eight Paraguayan ones received an exiled population from the Brazilian settlements (Susteric, 1999, p.157).

[…] The monolithic territorial, cultural and ethnic unity, which was characteristic of the Reductions, came into crisis with the advent of the expulsion of the Society of Jesus and then with the national revolutionary movements, in the early years of the 19th century [...].

Territorial disintegration, depopulation, political, institutional, and administrative disorganization were the decisive factors that dragged people into a state of architectural and urban ruin. [...] (Pozzobon, 2004, p.5, our translation).

The remnants of the Jesuit reductions were reduced by the action of time and men. The decrease in residents caused the deterioration of buildings, due to carelessness and lack of knowledge about maintenance techniques (Snihur, 2007). Some settlements ceased to exist due to plundering building materials, on others, cities or roads were built over their ruins. According to Brazilian architect Luis Antônio Bolcato Custódio (2014), the municipal government from São Miguel sold the material so that the settlers of the nineteenth century could build their houses. The Reduction became a real quarry, having its construction material sold or stolen. The price of stones varied according to the level of detail, being more expensive, with better finishes, or with ornaments. Two examples, built with material from the Brazilian Jesuit reductions are the Casa em Pedra, in the city of São Nicolau, RS (Figure 4) and a house in Entre-Ijuís, RS (Figure 5), which was demolished after having been legally protected.

Fig. 4: Stone House at São Nicolau. Source: IPHAE. Available at: www.ipatrimonio.org/sao-nicolau-casa-em-pedra. Accessed 04 June 2021.

Fig: 5. House at Entre-Ijuís built with building material extracted from a Jesuit Reduction. [Demolished]. Source: IPHAN. Available at: www.ipatrimonio.org/entre-ijuis-casa-construida-com-material-missioneiro. Accessed 04 June 2021.

The best-preserved Jesuit reductions are currently São Migue, in Brazil, Trinidad, in Paraguay, and San Ignacio Miní, in Argentina (Figures 6, 7, and 8). Preservation and perception are connected to elements of two categories: 1. Heritage and 2. Agents and their interactions. Material heritage is the entire physical collection: ruins and other elements of sites (real estate) and works of art in museums, mainly statuary and musical instruments (movable heritage). Intangible heritage, on the other hand, is all the culture and history that permeate such objects. Meanwhile, the agents and their interactions involve government agencies, researchers, the local community, and other sectors of society.

Fig. 6: Ruins in the Brazilian city of São Miguel Arcanjo: 1. Square, 2. Indication of houses, 3. Cemetery, 4. Church, 5. Priests’ Farm, 6. Priests’ courtyard, 7. Courtyard with manufactories, 8. Cotiguaçu. Source: Soster, 2014, p.91.

Fig. 7: Ruins in the Paraguayan city of Santísima Trinidad: 1. Square, 2. Houses, 3. Cemetery, 4. Church, 5. Priests’ Farm, 6. Priests’ courtyard and Courtyard with manufactures, 12. Belfry, 13. Second church. Source: Soster, 2014, p.92.

Fig. 8: Ruins in the Argentinian city of San Ignácio Miní: 1. Square, 2. Houses, 3. Cemetery, 4. Church, 5. Priests’ Farm, 6. Priests' Courtyard, 7. Courtyard with manufactures, 9. Cabildo, 10. Jail, 11. Hospital. Source: Soster, 2014, p.93.

The architectural and artistic remains and the historical accounts of the Jesuit Reductions in the three countries complement each other. Each historic site is capable of representing only a portion of the history of the Thirty Peoples and the Society of Jesus. Therefore, to compose a historical, social, economic, and cultural vision of the experience of the Jesuit reductions, it is necessary to observe them together. This, in turn, requires integrated actions for the preservation and dissemination of heritage assets that involve all agents; in order to justify the permanence of this heritage through the appropriation of the local and international community.

However, in 2014 all actions related to Jesuit Reductions were carried out by each nation individually, under the responsibility of different government levels, as shown in Table 2. Even the production of knowledge within universities is not shared with preservation agencies. This demonstrates the little interaction between government agencies and researchers.

4 Jesuit reductions, online

In the context of disseminating the remaining heritage of the Jesuit reductions, we understand that Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) would be low-cost, speed and efficient. However, they are little used. Both the 2014 survey and the current survey showed that most of the content available online about the Jesuit reductions is found in blogs that portray personal journeys to these sites. Therefore, they are not information from official sources, which have not taken advantage of the enormous potential of online media yet. The official websites made available at the time of the research had two levels of coverage: global and local.

UNESCO provides two pages on the Reductions included in the World Heritage List. One about the protected under preservation laws in 1983 (Argentina: San Ignacio Miní, Santa Ana, Nuestra Señora de Loreto, Santa Maria Mayo, and Brazil: San Miguel) and another about protected settlements under preservation laws in 1993 (Paraguay: La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue). Both inform about history and implantation, with photographs, in addition to providing links to conservation and preservation reports.

In Brazil, the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (Iphan) hosts on its website a page about São Miguel, containing IPHAN's history, conservation status, and performance. There is also the Rota das Missões website (Figure 9), which is perhaps the best-structured page. Such websites are more aimed at promoting tourism in the region, with little information about the history and Jesuit missionary culture.

Fig. 9: Brazilian online dissemination through Rota das Missões website. Source: Rota das Missões. Available at www.rotamissoes.com.br. Accessed 04 June 2021.

In Paraguay, the SENATUR website (Figure 10) presented, in 2014, the material on the Jesuit Reductions in three pages related to tourism: one on tourism to historical sites and festivities; another on the region of Misiones, Itapúa, and Ñeembucú, with location and main local tourist attractions; and another on the National Museums and Monuments. The pages had a tourist dissemination bias. In the current research, such pages were not found.

Fig. 10: Paraguayan online dissemination through SENATUR website. Source: SENATUR. Available at www.senatur.gov.py. Accessed 04 June 2021.

About the Paraguayan Jesuit reductions, the website “Ruta Jesuitica: Discover the Patrimonios Universales de Paraguay” (Figure 11) continues to be the most complete and unique with a visual presentation inspired by the Jesuit reductions. It also has a touristic character and was created through a partnership between SENATUR and the governments of the Departments of Misiones, Itapúa, and Alto Paraná, with support from UNESCO and the IDB. The content is organized by department and, among the tourist attractions, are the Jesuit reductions, each with its own page with information about mobile and immovable remains. It provides the best-organized content, facilitating the acquisition of minimum knowledge of the missionary heritage of this country.

Fig. 11: Paraguayan online dissemination through Ruta Jesuítica website. Source: Ruta Jesuitica. Available at rutajesuitica.com.py. Accessed 04 June 2021.

In Argentina, in 2014, there was a specific government website for the Guarani Jesuit reductions (Figure 12), which was the most complete among all, as it presented information on 1. location, public visitation, available airports; 2. Photographs; 3. history of Jesuit Reductions with an introduction, location, and spatial organization of the Thirty Reductions; 4. Light and sound shows; and 5. Misiones Jesuíticas program for the restoration, conservation, and dissemination of the Argentine Reductions. There was also a website for the Province of Misiones (Figure 13) with information on the preservation of San Ignacio Miní. In the current research, both are no longer online.

Fig. 12: Argentine online dissemination through Misiones Jesuíticas Guarani website. Source: Misiones Jesuíticas Guarani. Available at www.misiones-jesuiticas.com.ar. Accessed 04 June 2021.

Fig. 13: Argentine online dissemination through the website of the Ministry of Tourism of the Province of Misiones. Source: Ministry of Tourism of the Province of Misiones. Available at www.turismo.misiones.gov.ar/sanignacio.php. Accessed 04 June 2021.

It is concluded that the few existing websites deal with tourist issues of isolated Jesuit Reductions or of national specific interests, with a lack of online platforms with information about the whole set. Pages that have been online since 2014 have improved their content and aesthetics over time. If in 2018 most of them did not have their own visual identity because they were hosted on websites of national bodies; currently (2021), the statement is no longer true. Due to its touristic rather than historical-academic nature, each website presents basic information about the history and culture of the Reductions. In general, heritage education is hampered by the dispersion and incompleteness of information; what affects the appreciation and appropriation of the whole.

The use of ICTs to organize and highlight issues, needs and actions related to the Jesuit Reductions could cause them to be treated as a living system, where interactions between different agents and interaction with the cultural heritage could occur more effectively and justify its preservation in a glocal context. It is believed that it is necessary to retake the sense of a network of the set called Trinta Povos das Missões, through integrated inter-national actions for the preservation and dissemination of the entire missionary heritage as the set they comprise. This is one of the possible ways to strengthen them as a unique heritage of humanity, as was the experience developed by the Jesuits.

5 Review of strategies and proposal for the future

In 2014, at the end of the survey, it was proposed to create a virtual space for the inter-regional treatment of this heritage, where government agents, academics, and other sectors of society (involved in research, conservation, and dissemination of this heritage) could work in a collaborative way. An approach that acted as

[…] an integrative database of various centers, architectural heritage, and museums. Seeking to keep alive the cultural dynamics of the community, the preservation and physical and virtual access to such heritage, contribute to the appreciation of traditional cultures and reinforce the feeling of belonging and identity, consequently ensuring the permanence of this heritage for future generations (Pratschke; Santiago, 2006, p.1).

Among the current options for digital platforms, as pointed out by the Brazilian architect Ana Cecília Rocha Veiga (2018), WordPress is a web environment for the development of virtual museology. What can be directed to the case of the Jesuit reductions because it deals with the content of a similar character. Some of the main advantages pointed out by the author are 1. free and open source; 2. code update by the world community; 3. intuitive interface and user-friendly content editor; 4. semantic web and taxonomy; and 5. usability management and testing tool. According to her, 31% of Internet sites in 2018 were developed in WordPress.

A case that demonstrates the potential of WordPress in the field of cultural heritage is the iPatrimonio platform (www.ipatrimonio.org), created to geo-reference information on all listed properties in Brazil, in the four instances: global, national, state, and municipal. The uploads of this platform carried out by the first author of this article made it possible to understand that the databases of official bodies are incomplete and that searches on their websites are inefficient. In addition, the population lacks a specialized, agile communication channel that delivers the requested information in a language accessible to the general public.

In this way, it is understood that there are possibilities to expand the dissemination of the Jesuit reductions as the set they composed. But, for this, it is necessary to open the preservation agencies of the three nations to work together among themselves and with universities and local communities.

6 Final considerations

In the past, the Jesuit reductions formed a complex whole: a solidary society of mutual assistance within and between villages. At present, its understanding is impaired because its traces were reduced by wars and plundering, by the action of time and the hand of human beings. Therefore, it is necessary to look at the whole to understand the historical experience. In other words, considering preservation as a system is also necessary due to the fragmented nature of its heritage. However, the current division into three distinct nations has led to the preservation and dissemination in separate ways or in national groups, disfiguring the network that has marked the Jesuit reductions for more than a century. Online information is punctual and national, directed to the tourist aspect. But despite the reduction in the number of sites between 2014 and 2018, the visual quality of the sites and the information made available between 2018 and 2021 increased.

We believe that an improved flow of information, dissemination without geographic limits, and the availability of communication channels between agents would promote a better understanding of the Jesuit reductions and make their social function of supporting memory and a basis for historical and social reflection be maximized. In October 2018, an integrated route of the Jesuit Reductions between Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia was approved by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), passing through 19 icons recognized by UNESCO as World Heritage (Bergamo, 2018). This demonstrates international attention, via Unesco, for the importance of the Jesuit Reductions as a whole. With this, it is expected that the integrated work will take place between the various countries that are guardians of this important heritage.

cknowledgments

We would like to thank the financial support of the Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP), essential for carrying out this research.

References

Bergamo, M., 2018. BID aprova rota entre Brasil, Argentina, Uruguai, Paraguai e Bolívia: O caminho conecta 19 ícones da história da colonização jesuítica na região. Folha de São Paulo [Online] Available at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/monicabergamo/2018/10/bid-aprova-rota-entre-brasil-argentina-uruguai-paraguai-e-bolivia.shtml?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=compfb [Accessed 04 June 2021].

Custódio, L. A. B., 2014. Participation in the dissertation defense panel. Missões jesuíticas como sistema. Master. Universidade de São Paulo.

Gazaneo, J. O., 1997. The geopolitics of the missions. In: UNESCO and ICOMOS (Org.). The Jesuit missions of the Guarani. Verona: Commercial Bureau, pp.74-89.

Gutiérrez, R., 2004. As Missões Jesuíticas dos Guaranis: um espaço para a utopia. In: World Monuments Fund (Org.). Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani: programa de capacitação para conservação, gestão e desenvolvimento sustentável das Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani. World Monuments Fund: Brasília, pp.17-18.

Ibañez, M. C., 2000. Misiones Jesuíticas brasileñas. In: MUSEO DE ARTE HISPANOAMERICANO ISAAC Fernández Blanco (Org.). Misiones Jesuíticas brasileñas. Buenos Aires: Museo de arte hispanoamericano Isaac Fernández Blanco, pp.19-21.

Maeder, E. J. A. and Gutiérrez, R., 2010. Atlas territorial e urbano das missões jesuíticas dos guaranis: Argentina, Paraguai e Brasil. Sevilha: Junta Andalucia; Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico; Consejería de Cultura.

Pozzobon, J. L., 2004. Misiones: las reducciones jesuiticas. In: World Monuments Fund (Org.). Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani: programa de capacitação para conservação, gestão e desenvolvimento sustentável das Missões Jesuíticas dos Guarani. World Monuments Fund: Brasília, CD.

Pratschke, A. and Santiago, R. P., 2006. Olhares múltiplos, ou como conceber um espaço de conhecimento para a cidade de São Carlos. 10 SIGRADI, v. 1. Santiago de Chile: Universidad de Chile, pp.377-380.

Ribeiro, D., 1995. O povo brasileiro: a formação e o sentido do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Sepp, A., 1980. Introdução. In: A. SEPP, ed. 1697. Viagem às Missões Jesuíticas e trabalhos apostólicos. Coleção De Angelis. São Paulo: Itatiaia / Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, pp.5-15.

Snihur, E. A., 2007. O universo missioneiro guarani: um território e um patrimônio. Buenos Aires: Golden Company.

Soster, S. S., 2014. Missões Jesuíticas como Sistema. Master. Universidade de São Paulo.

Suárez, J. L., 2007. Hispanic Baroque: a model for the study of cultural complexity in the Atlantic world. South Atlantic Review, 72 (1), pp.31-47.

Sustersic, B. D., 1997. The religious imagery and cultural heritage. In: UNESCO and ICOMOS (Orgs). The Jesuit missions of the Guarani. Verona: Commercial Bureau, pp.155-185.

UNESCO, 2013. Jesuit Missions of La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue. [online] Available at:http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/648. [Accessed 04 June 2021].

Veiga, A. C. R., 2018. Museus Virtuais em WordPress. In: WORDCAMP, São Paulo.

Wilde, G., 2010. Interpretações históricas e atuais da experiência jesuítica. Interviewed by Patricia Fachin. Translated by Moisés Sbardelotto. IHU on-line: Revista do Instituto Humanitas Unisinos, 348 (10).

1Soster, S. S., Pratschke, A., 2018. Missões jesuíticas como sistema: revisão de estratégias e propostas para o futuro. I Seminário Internacional sobre Preservação Cultural no Território Trinacional. Foz do Iguaçu, 2018. Foz do Iguaçu: UNIOESTE, v. 1.