Diálogos (geométricos) com a cidade

Luciana Sandrini Rocha é arquiteta e urbanista, Mestre em Geografia. Professora do Curso Técnico de Edificações, do Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Sul-Rio-Grandense. Estuda representação gráfica, projetos de edificações, materiais de construção e gestão ambiental integrada.

Adriane Borda Almeida da Silva é arquiteta e urbanista, Doutora em Filosofia e Ciências da Educação. Professora Associada da Universidade Federal de Pelotas. Estuda representação gráfica digital, modelagem geométrica e visual, transposição didática e educação a distância.

Como citar esse texto: ROCHA, L. S.; SILVA, A. B. A. Os diálogos (geométricos) que Gehry estabelece com a cidade de Bilbao. V!RUS, São Carlos, n. 14, 2017. Disponível em: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus14/?sec=4&item=14&lang=pt>. Acesso em: 15 Jul. 2025.

Resumo

A forma do Museu Guggenheim de Bilbao é aqui problematizada pelo interesse didático em investigar as estratégias projetuais utilizadas por Frank Gehry para reconfigurar o tecido e a paisagem urbana ali envolvidos. São escassos os discursos sobre o projeto, acompanhados de razões objetivas e apoiados em sua decomposição formal. Entende-se a conveniência desta complementação, frente ao seu potencial como referência junto aos processos formativos de arquitetura. Constituiu-se a hipótese de que a forma do edifício advém de um repertório reduzido de fragmentos formais deste tecido e paisagem configurados tanto por regras compositivas clássicas como próprias da geometria fractal. Esta leitura, construída por meio de traçados sobrepostos às imagens fotográficas e técnicas da obra e de seu entorno imediato e pelo conceito de dimensão fractal, facilitou identificar um rigoroso controle formal, que parte da regulação de suas representações tanto em projeção ortográfica, mantendo proporções, paralelismos e convergências; como em perspectiva, explorando concordâncias logradas por efeitos anamórficos. Demonstra-se assim a aplicação de um método, de abordagem geométrica, que facilita a construção de hipóteses sobre estratégias projetuais. Neste caso, as de Gehry para dialogar com um tecido urbano específico: por meio de ações recursivas, valendo-se de transformações topológicas, em seu sentido matemático, sobre o vocabulário formal do próprio lugar, ações hoje facilitadas pelos meios digitais de representação.

Palavras-chave: Museu Guggenheim; Frank Gehry; Forma arquitetônica; Geometria Fractal; Ensino de projeto.

Introdução

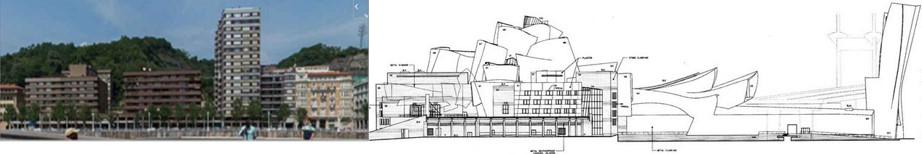

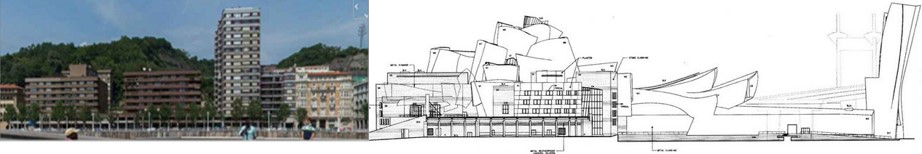

Neste trabalho estuda-se o projeto do edifício do Museu Guggenheim de Bilbao, realizado pelo escritório de Frank O. Gehry. Ele venceu um concurso, em 1990, entre três propostas apresentadas à Fundação Solomon R. Guggenheim. Conforme as informações disponíveis junto ao endereço eletrônico do próprio Museu (GUGGENHEIM, 2017), a participação de Gehry neste concurso foi por convite e a obra se desenvolveu entre 1993 e 1997, impondo-se na paisagem de Bilbao (Fig. 1).

Fig 1. Vista do Museu. Fonte: Imagem disponibilizada por Àlex Ferrer Gimeno no aplicativo Google Street View em dezembro de 2016.

Naomi Stungo, ilustrando seu discurso com fotografias do edifício, considera que Frank Gehry produziu “uma explosão à beira do rio, um tumulto de contornos e formas” (STUNGO, 2000, p. 20). O impacto desta construção, também observado por Isenberg (2009), integra-se ao movimento de revitalização de Bilbao, cidade que passava por uma grande estagnação econômica na época. É verdade que o fenômeno que ficou conhecido como “Efeito Bilbao” não deve ser atribuído exclusivamente à construção do Museu, uma vez que o mesmo fez parte de um projeto de requalificação urbana que abrangeu diversas áreas da cidade e que continua em fase de implementação ainda hoje1, mas reconhece-se que o projeto de Gehry se tornou o ícone desse fenômeno. Stungo comenta também que

[...] a arquitetura de Gehry não é considerada “difícil”, como ocorre com boa parte da arte moderna [...]. Exatamente como os cubistas, no início do século XX [...] a arquitetura de Gehry, no fim do século, apresenta os prédios com uma assombrosa desarmonia, uma experiência de todos os ângulos ao mesmo tempo (STUNGO, 2000, p. 10-11, grifo nosso).

Grifa-se a opinião de Naomi Stungo, para retomá-la, questionando a consideração de “desarmonia”. Em termos formais o edifício estabelece um diálogo com a cidade?

Charles Jencks, com seu discurso ilustrado também apenas por imagens fotográficas da obra, observou que o edifício:

[...] reflete a inconstância do humor da natureza, as menores mudanças na luz do sol ou chuva. O mais importante é que suas formas são sugestivas e enigmáticas de modo que se relacionam tanto com o contexto natural quanto com o papel central do museu na cultura global […]. Esta estratégia emergente […] se tornou uma convenção dominante do novo paradigma. (JENCKS, 2002, p. 157-158, tradução e grifo nossos)2.

Este discurso provoca questionamentos sobre quais elementos formais da obra o autor estaria se referindo para visualizar, por exemplo, as relações com o contexto natural. Parece que não se restringiu à sensibilidade dos “humores” das variações climáticas.

Denna Jones reforça a percepção de Charles Jencks, de que se estaria frente a um novo paradigma de processos de produção de arquitetura, afirmando que:

Originalmente um exercício escultural, o formato inicial do museu não veio dos métodos digitais, mas da apreciação de Gehry da paisagem e do contexto. À medida que o projeto prosseguia, Gehry ficava cada vez mais impressionado com a capacidade do software digital para gerar formas (JONES, 2015, p. 523-524, grifo nosso).

Aqui Jones observa o interesse de Gehry com a potencialidade das ferramentas digitais para o aperfeiçoamento de seu processo projetual, percebendo o quanto poderia controlar com precisão a forma por ele pensada em suas conexões com o lugar.

Outros discursos reafirmam a condição de sua forma derivar de um processo escultórico no e para o lugar: “...o desenho de Gehry cria uma estrutura escultórica e espetacular perfeitamente integrada na trama urbana de Bilbao e seu entorno” (GUGGENHEIM, 2017, tradução nossa)3. Gehry reforça estas afirmações em entrevista concedida, em 1995, a Zaera-Polo:

Bilbao é um projeto muito contextual, mas não no sentido convencional [...]. Espero que, quando as pessoas virem o edifício pronto, percebam que estou lidando com o contexto. Bilbao é uma cidade industrial muito dura, com um rio e uma paisagem verde fantástica. O terreno do museu fica numa curva maravilhosa sobre o rio. A cidade se situa acima do nível do terreno... O problema desse edifício era articular a cidade com o rio, trazer a cidade para o outro lado da estrada, e então devolvê-la até o rio [...]. Na realidade, minha primeira decisão foi propor o terreno. (ZAERA-POLO, 2015, p. 228).

A coletânea de documentação deste edifício, digital ou impressa, veiculada em contextos científicos ou não, refere-se especialmente a imagens fotográficas. Há necessidade de percorrer a obra sob diferentes trajetórias visuais para poder apreendê-la. Plantas, fachadas e seções, neste caso, são elementos densos e pouco elucidativos, até mesmo para um leitor especializado.

Sob um interesse essencialmente didático, questiona-se sobre quais elementos objetivos, da geometria, Gehry se apoia para estabelecer esta relação “tumultuada”, “enigmática” e “integrada” com a cidade. Dentre tantos elementos formais do entorno, quais deles foram mais ou menos determinantes para a configuração da obra?

Para Jencks (2002, p. 157), diversas obras de Gehry, incluindo a do Museu, incorporam elementos da geometria fractal. Esta geometria, sistematizada por Benoit Mandelbrot, utiliza um saber constituído na história da matemática associado à computação gráfica, envolvendo procedimentos recursivos para descrever as formas da natureza que não haviam sido contempladas pela geometria Euclidiana.

Ela descreve muitos dos padrões irregulares e fragmentados em torno de nós [...], através da identificação de uma família de formas que chamo de fractais. Os fractais mais úteis envolvem probabilidade e tanto suas regularidades quanto suas irregularidades são estatísticas. Além disso, as formas aqui descritas tendem a ser de escala, o que implica que o seu grau de irregularidade e/ou fragmentação é idêntico em todas as escalas. (MANDELBROT, 1983, p. 1, tradução e grifos nossos)4.

Os fractais podem ser definidos através de um iniciador e um gerador que passam por um processo de recursão e alteração em sua escala, mantendo, porém, autossimilaridade ou ainda autoafinidade. Desta maneira, as partes são escalas reduzidas da versão total do objeto, sendo que a diferença entre um fractal autossimilar e um autoafim está em que, no segundo caso, as versões se formam em diferentes escalas e direções no espaço. Além disto, ambos os tipos podem ser exatos ou estatísticos, categorizados pela probabilidade, tendo o último as versões em escala reduzida estatisticamente iguais a do objeto completo.

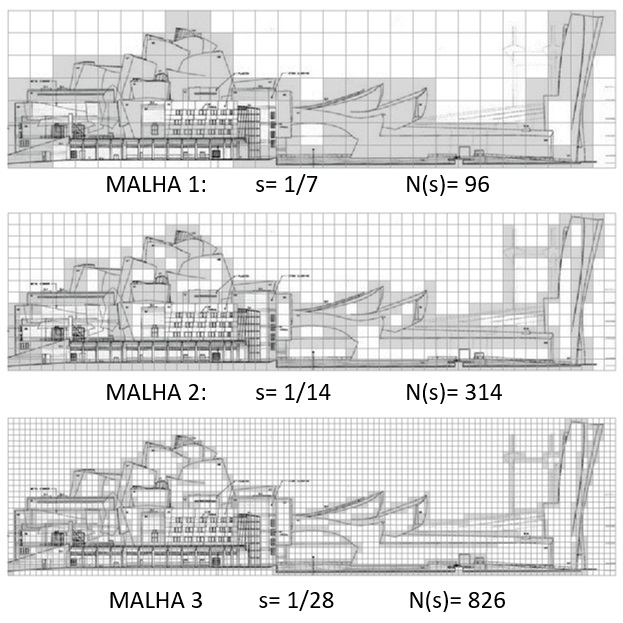

Matematicamente, a geometria fractal quebra o paradigma da dimensão inteira como condição para caracterizar um elemento, constituindo o conceito de Dimensão Fractal (D). Este é utilizado para determinar o grau de ocupação do espaço, de modo que quanto maior for a irregularidade de uma forma, maior será seu D. De acordo com Backes e Bruno (2005, p. 51), a Literatura fornece diversas abordagens para se estimar a Dimensão Fractal, existindo uma lógica que generaliza o cálculo da dimensão topológica no âmbito da geometria euclidiana (dimensões inteiras) para abarcar também o cálculo da dimensão fractal (fracionada). O método “Box Counting” é uma abordagem que facilita a compreensão por profissionais acostumados mais com a linguagem visual do que com a algébrica, por se valer de um procedimento de contar as células que a forma do elemento investigado ocupa em um determinado espaço. Estas células são subdivididas, recursivamente, até o momento em que todas elas adquiram a condição de estarem totalmente cheias ou vazias, dependendo assim de uma escala de resolução. De acordo com Ostwald e Vaughan (2013, p. 242, tradução nossa),

Desde os anos 90, a análise fractal tem sido utilizada para medir as propriedades formais de projetos urbanos, planos de cidades e skylines [...]. Pesquisadores de Arquitetura também utilizaram uma variação manual da análise fractal para medir as propriedades visuais de edifícios contemporâneos e históricos5.

Sedrez (2009) e Ganhão (2009), ao se referirem à forma do Museu como fractal, reproduzem JENCKS (2002) e também Sala M. Martins e Henrique Librantz (2006, p.92), no sentido de os discursos não virem acompanhados de demonstrações gráficas ou numéricas.

Em entrevista concedida a Giron (2015, p. 16), Gehry problematiza o emprego dos meios computacionais em um processo projetual:

[...] O desenho a mão dá um sentido de continuidade [...] adoro a ideia da continuidade total e ambígua. Só depois transponho para a tela do computador. A imagem no computador é sem vida, fria, horrível. O computador não pode ser o inventor das formas. Nós é que temos que dominá-lo (Grifo nosso).

Mesmo apoiando-se nas potencialidades dos softwares para o desenvolvimento de suas ideias, o processo projetual de Gehry se estabelece inicialmente mediado por representações em croquis e maquetes físicas. Questionado sobre a possibilidade de comparar o seu método projetual por meio de maquetes em grande escala ao método dos arquitetos renascentistas, Gehry responde ao arquiteto e crítico Alejandro Zaera-Polo da seguinte maneira:

Sim, é verdade. [...] Se eu tivesse que dizer qual é minha maior contribuição para a prática da arquitetura, diria que é conseguir uma coordenação entre as mãos e os olhos. Isso significa que fui me tornando muito bom em levar a cabo a construção de uma imagem ou de uma forma que estou procurando. Acho que é minha melhor habilidade como arquiteto. Sou capaz de transferir um croqui para uma maquete e daí para um edifício... (ZAERA-POLO, 2015, p. 221)

No processo projetual do Museu, após a elaboração de desenhos a mão executaram-se maquetes, que foram decodificadas para a linguagem CAD-CAM utilizando-se de uma caneta digitalizadora, através do software CATIA. A partir deste modelo controlado no espaço digital, foi desenvolvida toda a documentação do projeto arquitetônico, bem como o cálculo estrutural e o detalhamento de estruturas metálicas e de revestimentos (LINDSEY, 2001, p. 43-44). Gehry já havia feito experimentações em projetos anteriores, como a escultura em forma de peixe para a Vila Olímpica de Barcelona em 1992 e o projeto do Walt Disney Concert Hall, que acabou sendo inaugurado somente em 2003. Entretanto, foi a partir do museu de Bilbao que ele e sua equipe consolidaram este método de trabalho e Gehry encontrou um meio de controlar efetivamente a forma com a precisão que desejava.

O arquiteto recebeu o prêmio Pritzker de 1989, havendo assim um reconhecimento do conjunto de sua obra pela crítica especializada de arquitetura. E a expressividade de sua produção é tanta que o tema foi tratado em um episódio da animação “Os Simpsons” (FOX, 2005). No referido episódio, o processo criativo de Gehry é ironizado, associado à ideia de ser “aleatório”, desprovido de método e sem conexões programadas com o desenho da cidade, pois seu personagem tira de uma folha de papel amassada a inspiração para o projeto de uma sala de concertos. Ironizando também o processo de execução do projeto, uma estrutura metálica convencional é totalmente deformada por processo mecânico, parecendo um ato de destruição. Isto demonstra que sua obra é apreciada e discutida também por um público leigo.

Neste trabalho parte-se da hipótese de que, longe de ser um procedimento aleatório, o Guggenheim de Bilbao foi um projeto que justificou o emprego de técnicas de controle paramétrico das formas, para harmonizar práticas clássicas de organização formal de arquitetura com a lógica da geometria fractal 6. A conexão com este tipo de geometria se fez para garantir um diálogo da obra com a cidade em seus elementos naturais e construídos. Partindo-se desta breve revisão, investiu-se, portanto, em investigar formalmente a obra, em seus elementos objetivos caracterizados por sua geometria. Desta maneira, tratou-se de identificar as lógicas de organização formal envolvidas, desde as clássicas às recursivas.

1 Metodologia

Este trabalho amplia o estudo já registrado em (ROCHA; BORDA, 2016). Incrementa-se o método, apoiando-se em Fonatti (1988) e utilizando-se do conceito de dimensão fractal. Parte-se da análise da documentação digital, a qual inclui fotografias do entorno da edificação e fotografias e representações técnicas da obra, como plantas, cortes e vistas ortográficas, disponibilizadas em livros, revistas, vídeos e na rede mundial de computadores.

Para compreender o uso de lógicas relativas à Geometria Fractal, seguiu-se com as análises gráficas, observando-se a incidência de autossimilaridades ou autoafinidades por processos comparativos, acrescentando-se a estimativa da Dimensão Fractal, por meio do método Box Counting. Este consiste na aplicação recursiva de malhas sobre as elevações das edificações do entorno e do edifício, e análise da proporção do número de quadros ocupados em relação ao número total de quadros. Costa (2014, p. 80), Sala (2004, p. 41) e Backes e Bruno (2005, p. 3) explicam mais detalhadamente esse método.

Para os estudos topológicos, o método pode ser descrito nos mesmos termos de Fonatti (1988).

1) [...] as reflexões tem sua origem na experiência didática do ensino de geometria; 2) a base consta de comunicações visuais (gráficas, representadas em forma de desenhos, plantas, elementos formais, matrizes estruturais de criação, análise de formas, estudos de proporções e diagramas construtivos; 3. O meio é o método comparativo, investigando formas e estruturas através de uma análise comparativa. E no que se refere ao conteúdo o método compreende quatro aspectos: a) a lógica interna da forma... A forma em sua lógica compositiva... b) a atualização e o efeito da forma. Os aspectos técnico-criativos da forma em sua origem e sua renovação didática.... A forma em sua origem e apropriação. C) a forma no entorno. A relação entre forma e seus condicionamentos externos e exógenos;... A forma como jogo criativo no processo de comunicação, como resultado concreto em seu entorno... D) transformação do entorno a través da forma. (FONATTI, 1988, p. 11-12).

Os resultados do estudo constituem-se das hipóteses elaboradas, sendo apresentadas de maneira a destacar o quanto o tecido da cidade determinou e foi determinado pelas lógicas formais associadas a este edifício.

2 A Construção das Hipóteses

2.1 A origem da forma e sua relação com o lugar

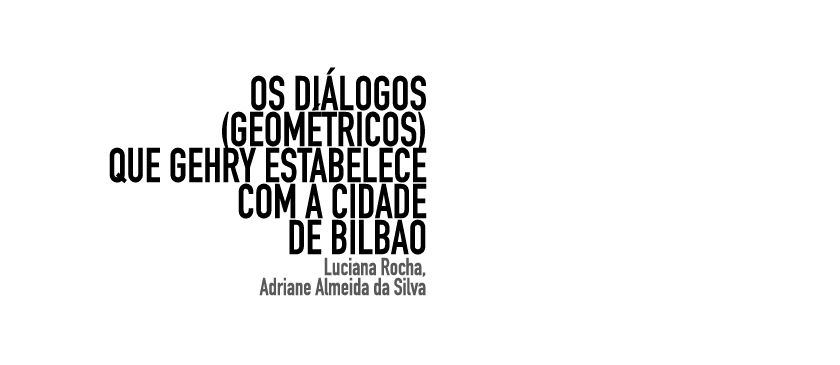

O lugar escolhido por Gehry para a implantação do museu fica às margens do rio Nervión, próximo da Universidade, do Museu de Belas Artes e do Teatro Arriaga, importantes centros culturais da cidade de Bilbao. Conta com acesso facilitado através da rua Iparraguirre e da Ponte Salbeko Zubia, destacados na imagem da esquerda da Figura 2. Chama-se a atenção para a forma do terreno, que já estava delimitada pelas curvas do rio e da ponte, podendo-se observar ao comparar as duas imagens da direita da Figura 2, antes e depois da construção do edifício. Tem-se como hipótese esta forma como origem do vocabulário empregado por Gehry.

Fig. 2. a) O museu e seus arredores, b) sítio antes da obra (ano de 1991) e c) após a obra. Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagens do aplicativo Google Earth, acesso em maio de 2016.

O Museu se estende sob a ponte, construída na década de 1970, através de uma de suas salas de exposição (Sala 104), a qual conecta uma torre no lado oposto da mesma ponte (Fig. 3). Essa torre é o elemento mais alto de toda a construção e dá acesso ao museu para quem chega através da ponte, fazendo contraponto com o volume do átrio, que só se sobressai em relação a ela em função de suas proporções. Em vídeo de Donada (2004), Gehry relata sua intenção ao projetar a torre:

[...] quando eu projetei a torre, pensei em uma vela. Há um momento em que você está velejando e [...] apenas por uma fração de segundo a vela treme. Eu capturei esse momento. Isso é o que eu tento fazer com meus edifícios. Dar-lhes uma impressão de movimento me agrada porque isso os torna parte da grande mudança da cidade. Os edifícios são parte da vida e eles mudam. Há algo transitório sobre eles. (DONADA, 2004, tradução nossa7).

O entorno do terreno e sua conformação topográfica foram determinantes no projeto de Gehry. Ao Sul, numa cota mais elevada (situada no nível das ruas de acesso), o edifício se apresenta através de formas ortogonais e materiais tradicionais. Com isto estabelece relação com os espaços históricos da cidade, tanto formalmente quanto pelos revestimentos e cores adotadas.

Os elementos voltados para o Norte, à beira do rio, apresentam formas orgânicas e são revestidos com materiais reflexivos, como vidro e placas de titânio, que valorizam a relação da edificação com a água e a natureza, que é reforçada pela existência de um espelho d´água. O titânio confere a cor acobreada do edifício e muda de tonalidade conforme o horário do dia ou as condições climáticas, conforme observa Charles Jencks. O fato dessa parte do terreno estar situada numa cota inferior ao restante de seu entorno possibilita que o edifício, mesmo adotando uma escala monumental, respeite a altura das edificações do entorno, integrando-se a elas e ainda assim representando um elemento inédito na paisagem.

O átrio, além de ser o elemento organizador interno, dando acesso às galerias através de passarelas, o é também em termos volumétricos, contrastando com o que lhe circunda. Constitui um espaço híbrido, entre o exterior e o interior, comunicando o edifício com a cidade e o rio graças aos panos de vidro com a altura de três pavimentos. Este espaço está coberto por “un gran lucernario en forma de flor metálica” (GUGGENHEIM, 2017), parecendo também estar relacionada com a própria conformação do lote original (Figura 2b), que se assemelha a uma espécie de folha ou pétala (autoafinidade).

A forma e seus condicionamentos externos

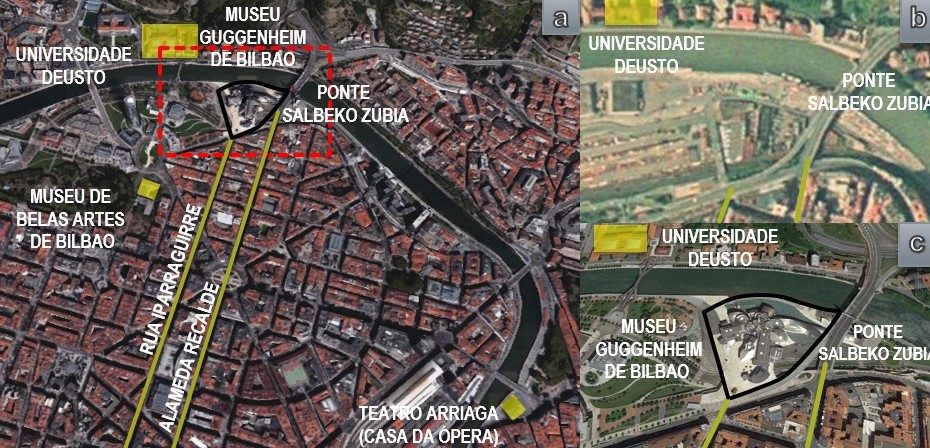

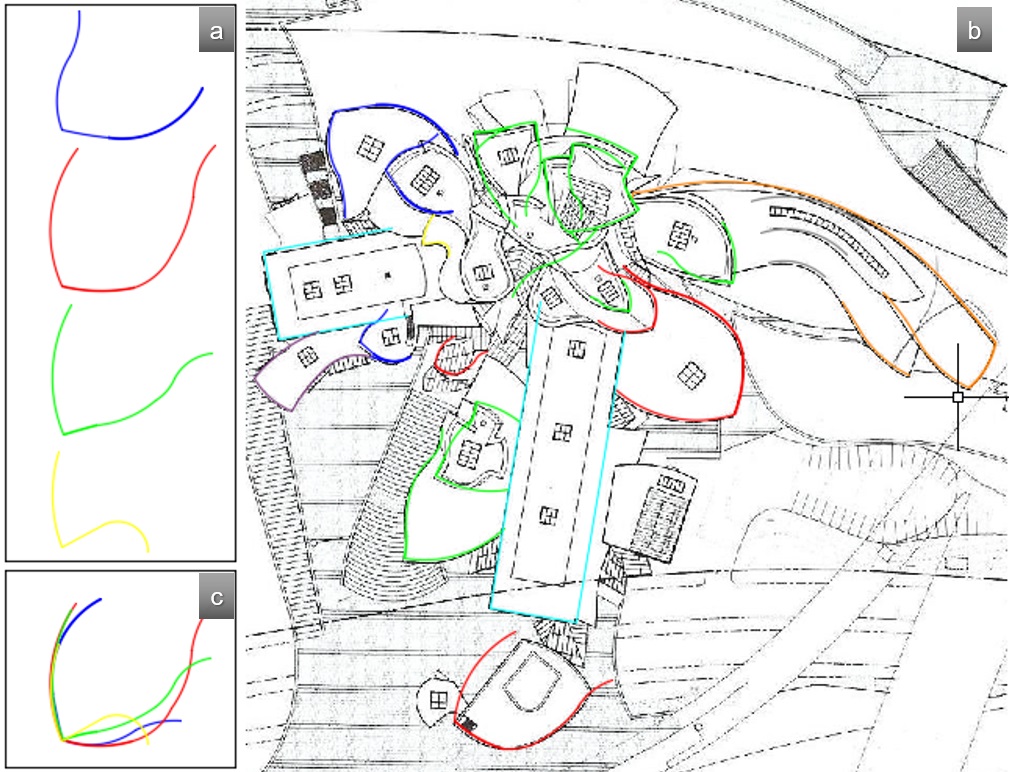

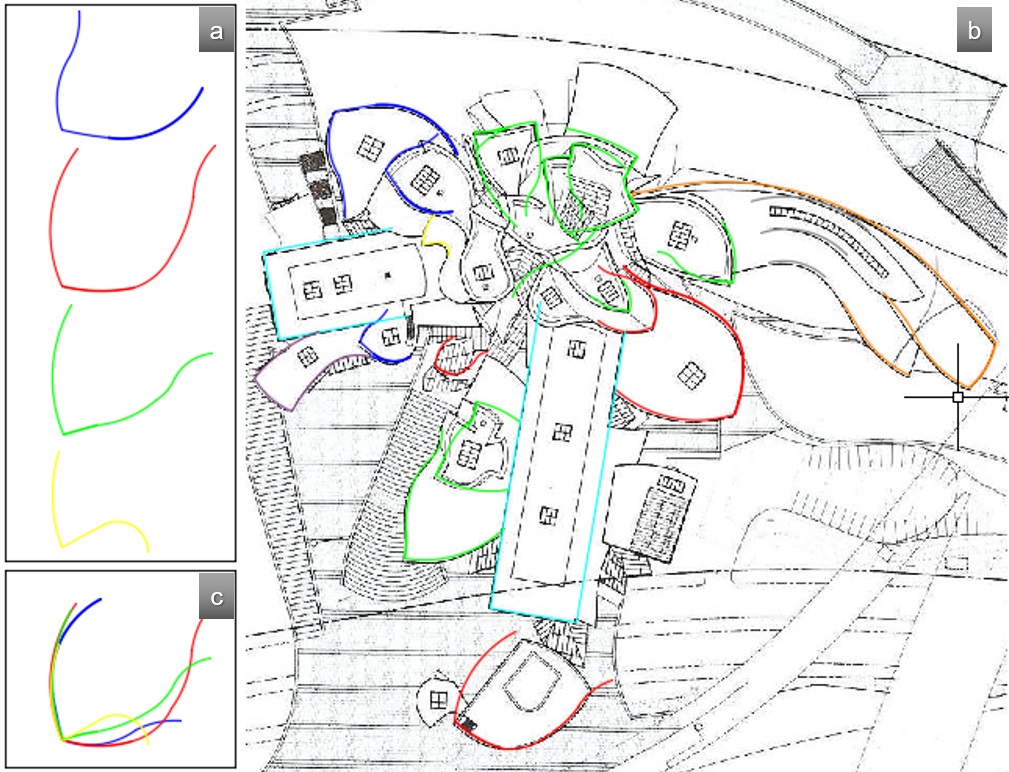

Conforme se observa na Figura 3, pode-se identificar traçados e eixos reguladores que acusam como ponto de partida o trajeto da ponte Salbeko Zubia. Observa-se também uma convergência de traçados para o local do átrio, o que reflete sua importância na organização interna dos espaços, conectando os eixos dos volumes prismáticos: de maior extensão (que também converge com o eixo da ponte), de menor extensão (à esquerda) e o da sala de exposições 104, já citada anteriormente por se estender sob a ponte e se conectar com a torre.

Fig. 3. Traçados reguladores. Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagem disponibilizada na internet em www.jaumeprat.com/el-lugar-de-la-ensenanza, acesso em 2 de março de 2016.

O repertório formal

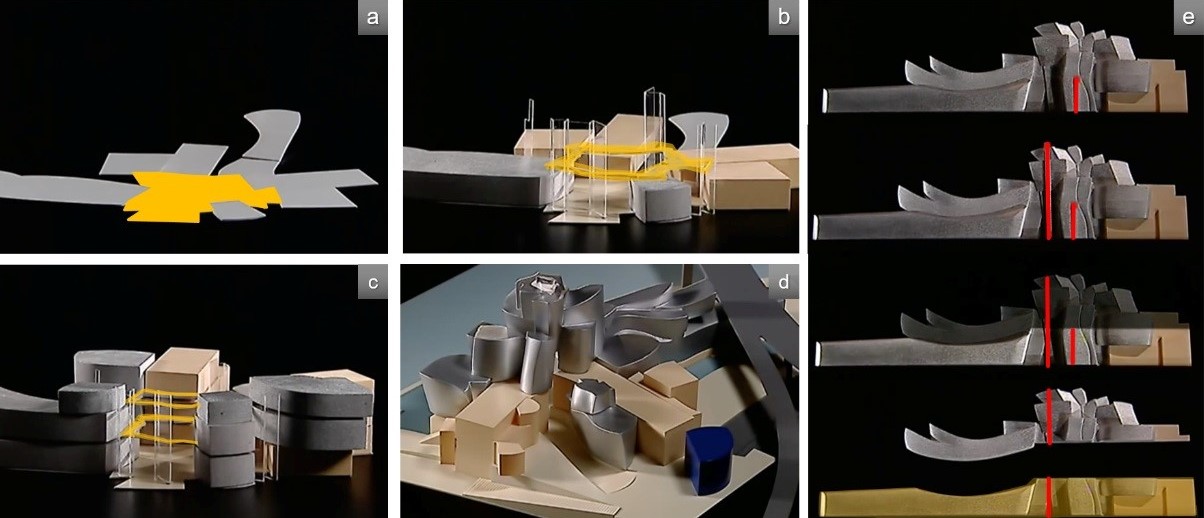

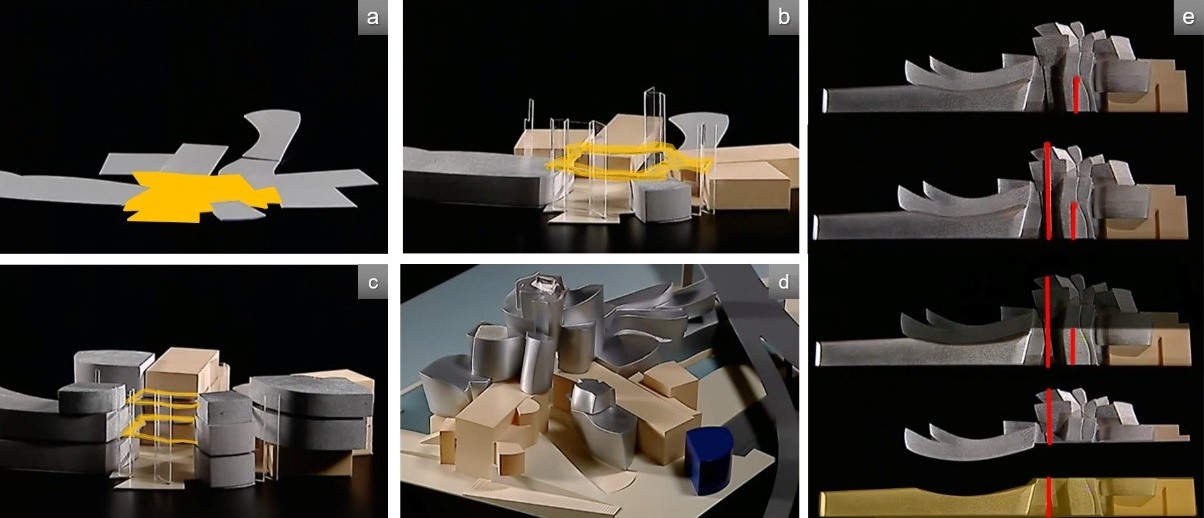

A obra transita entre superfícies poliédricas e curvas, entre superfícies regradas desenvolvíveis, reversas e com maior grau de liberdade. Compreender o esquema organizacional do museu dá pistas para entender alguns propósitos de associações formais, conforme se observa na Figura 4: a) o átrio (na cor amarela) constitui espaço central de distribuição, em conformação híbrida, integrando os tipos formais que caracterizam a obra; b) volumes dos espaços administrativos, comerciais e de exposições do térreo se organizam ao redor do átrio, e passarelas promovem a circulação acima dele (em amarelo); c) “áreas utilizáveis” estão distribuídas em três pavimentos, e panos de vidro fazem o fechamento vertical entre os volumes; d) volumetria do conjunto, onde se observam prismas, cilindros, estes de diretriz curva e de geratriz ortogonal, (em bege e azul) e cilindroides ou ainda formas mais livres (em cinza); e) demonstração da “altura útil” do edifício, que compreende menos da metade de sua altura total.

Fig. 4: Estrutura organizacional do museu. Fonte: Elaborado pelas autoras a partir de imagens do vídeo de Donada (2004).

Como pode ser observado no conjunto de imagens da Figura 5, os tipos de galerias estão associados à geometria dos espaços. Os volumes prismáticos formam principalmente as galerias “tradicionais”, com plantas em formato quadrado ou retangular, que recebem exposições “clássicas”. As galerias, destinadas às exposições de arte contemporânea, têm plantas em formato curvo e pés-direitos muito mais altos.

Fig. 5: Salas de exposições. Fonte: elaborado pelas autoras a partir de imagens do vídeo de Donada (2004).

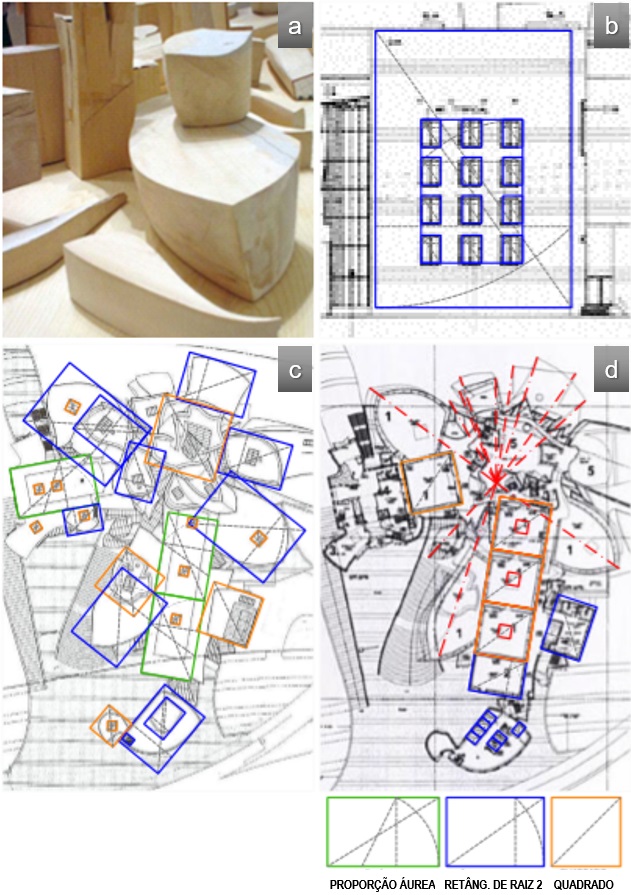

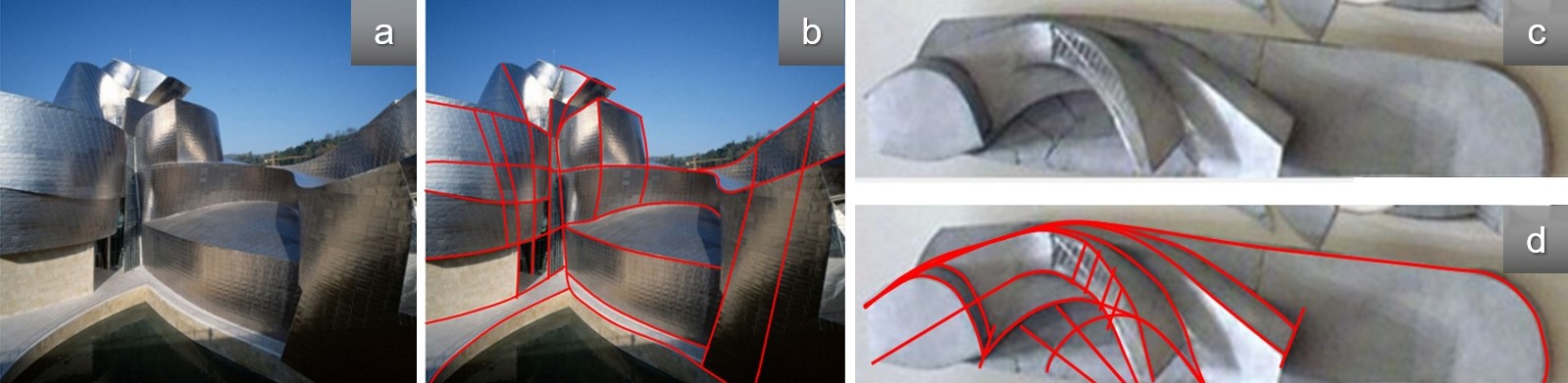

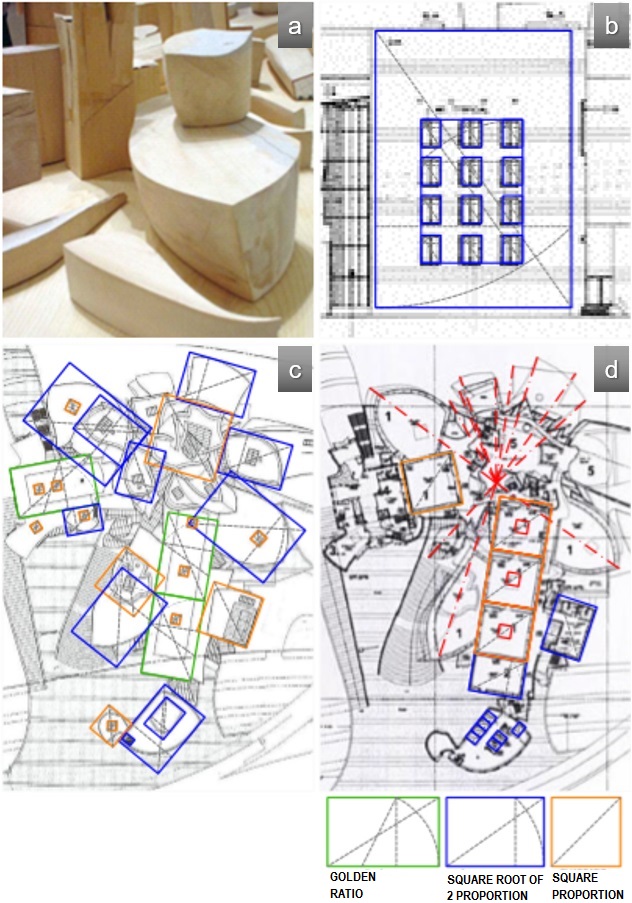

A forma em sua lógica compositiva: entre proporções e simetrias

Conforme os esquemas gráficos sobre as imagens da Figura 6, foram identificadas correspondências com proporções determinadas: em (b) de retângulo raiz de 2 nos polígonos envolventes da fachada do volume prismático, de cada esquadria e do conjunto delas; sobre as imagens (c) e (d), a proporção áurea nos volumes prismáticos que conformam as salas de exposições “tradicionais”, quadrados na conformação de volumes secundários e nas salas de exposições “tradicionais”, e retângulo de raiz 2 nos sólidos envolventes das formas curvas. Em (a) o detalhe de modelagem dos volumes em madeira, sobre os quais, por decorrência das análises em planta, se lança a hipótese de terem sido constituídos a partir de sólidos envolventes controlados pela proporção raiz de 2, a qual aparece mais frequentemente no projeto. O fato dessas formas terem sido individualmente produzidas em madeira indica ter havido muito cuidado com a modelagem de suas superfícies. Lindsey (2001, p. 45) relata que após o desenvolvimento do projeto no Catia foi produzido um modelo de verificação para garantir a precisão das formas.

Fig. 6: Proporções e simetrias. Fonte: elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagens veiculadas na internet em Guggeheim (2017), Pagnotta (2016) e Slessor (2010)

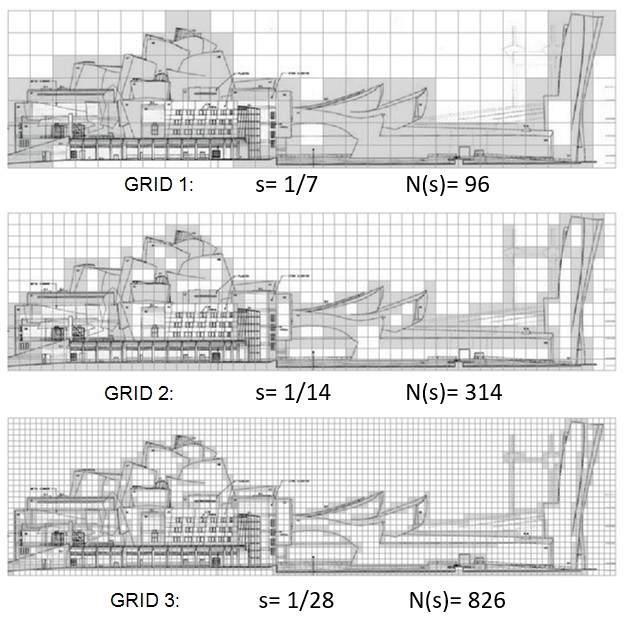

Aspectos técnico-criativos e a renovação didática: a estimativa da dimensão fractal do edifício

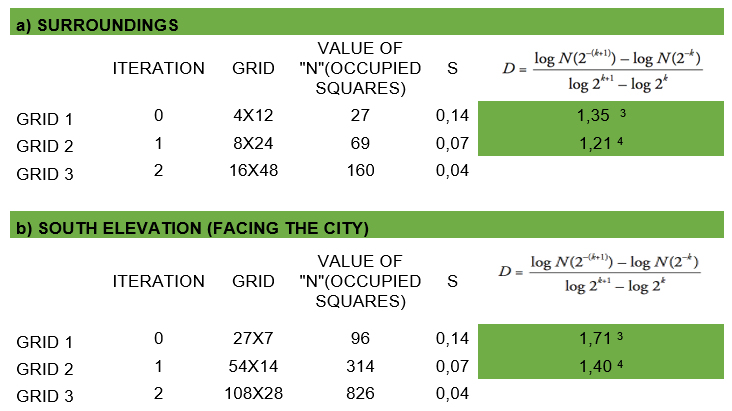

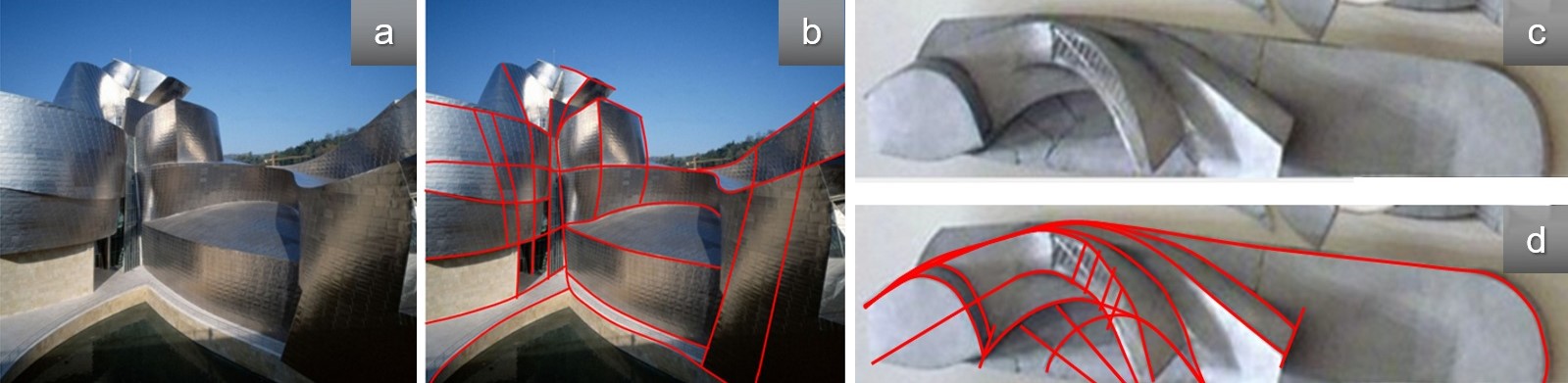

O cálculo da Dimensão Fractal foi aplicado sobre duas imagens que se confrontam, com o propósito de compará-las: a fachada sul do Museu e o conjunto de edificações emoldurado pela vegetação ao fundo. Se fez pela observância de similaridades entre as duas imagens (Fig. 7), possível estratégia de refletir a cidade não somente pelo efeito da luz sobre o titânio, mas como resultado de uma transformação geométrica, repetindo a própria forma.

Fig. 7. À esquerda a imagem do entorno que confronta a obra e à direita a fachada sul (voltada para a cidade). Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagens disponibilizadas no aplicativo Google Earth e na internet, em Pagnotta (2016).

Aplicou-se o método “Box Counting” considerando-se três iterações junto ao procedimento recursivo de subdivisão da malha de referência, tal como exemplificado sobre a fachada sul na sequência de imagens da Figura 8.

Fig. 8: Método Box Counting aplicado a Fachada Sul (voltada para a cidade). Fonte: elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagens disponibilizadas na internet em Pagnotta (2016).

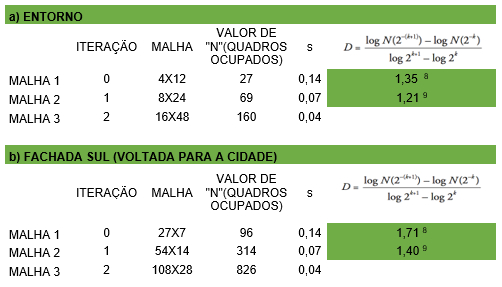

O cálculo referente à aplicação do método é mostrado na Tabela 1. Observa-se que os valores são bastante próximos, demonstrando-se que por mais que pareça um “tumulto de formas” o grau de ocupação do espaço, em termos visuais, parece corresponder com o da paisagem preexistente. Constatam-se, assim, permanências sob esta abordagem. Elementos ortogonais, ritmados em um primeiro plano e logo curvas de contorno com rugosidades similares ao fundo.

Tab. 1: Cálculo de D para a) entorno e b) Fachada Sul. Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras.

Nota [8] Valor calculado com base nas iterações de número 0 e 1.

Nota [9] Valor calculado com base nas iterações de número 1 e 2.

A autoafinidade: do urbano à escala do edifício

Dependendo do nível em que são feitas as secções para a obtenção das plantas, logicamente, as formas do Museu assumem diferentes curvaturas. No entanto, na análise da implantação do edifício é possível identificar um procedimento recursivo, em sentido anti-horário, de variação de escala sobre as diferentes formas, tendo como eixo central a posição do átrio. As Figuras 9 (a) e 9 (c) mostram os padrões de formatos de folhas (relativos à forma do próprio terreno) e a sobreposição entre estes padrões, que mostra uma correspondência topológica entre eles. A Figura 9 (b) mostra os mesmos padrões identificados na planta de implantação.

Fig. 9: Padrões em folha falciforme. a) padrões identificados; b) planta de implantação com padrões de folhas falciformes; c) sobreposição de padrões. Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagem disponibilizada na internet em www.jaumeprat.com/el-lugar-de-la-ensenanza, acesso em 2 Mar. 2016.

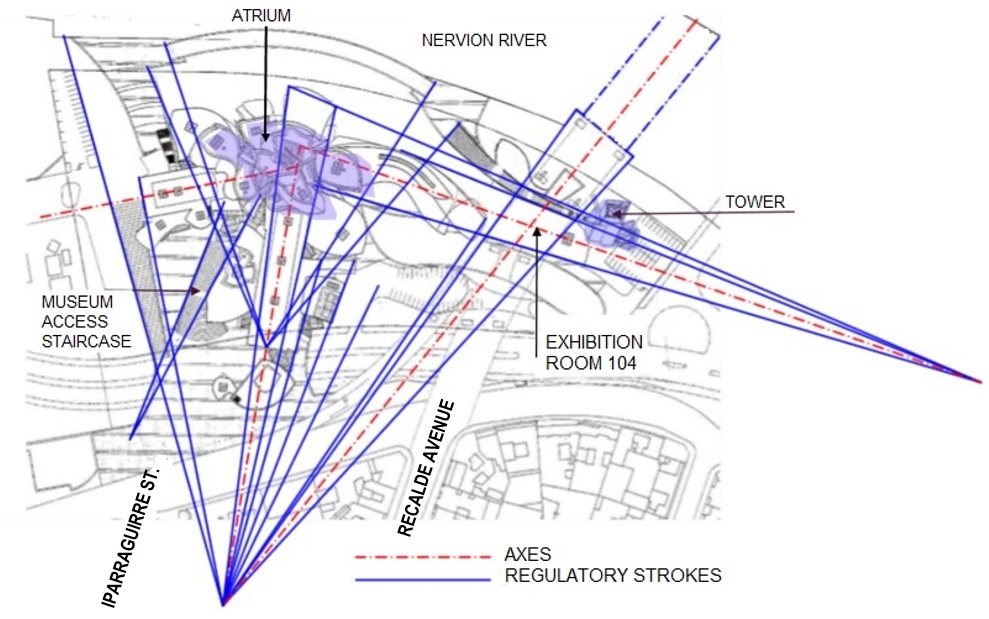

2.7 Transformação do entorno a partir da forma: relações de concordâncias,paralelismos e convergências nas visuais

Gehry, por meio de modelos físicos, ou com precisão, a partir dos digitais, controla a forma ao nível dos olhos. Parece valer-se de efeitos anamórficos (ilusões de ótica sobre determinados pontos de vista) para lograr concordâncias e paralelismos. Conforme pode-se observar pelas imagens da Figura 10, as fotos eleitas para serem veiculadas no site oficial do Museu explicitam o propósito de continuidade e convergências.

Fig. 10: Concordâncias. Fonte: Elaborada pelas autoras sobre imagens veiculadas no site do Museu (GUGGENHEIM, 2017).

Nelas observa-se também o reforço da ideia de recursividade, das características fractais da obra, em que as visuais sempre remetem à leitura da forma de folha falciforme, cuja referência vem inicialmente do próprio lote (Figuras 2 e 10).

Resultados e discussão

Observou-se que existe uma distância considerável entre a caricaturização do processo projetual de Gehry, da suposta aleatoriedade, apresentada pelo episódio de “Os Simpsons” e a efetiva complexidade e controle de tal processo. O arquiteto extraiu do próprio local o vocabulário formal a ser empregado, como estratégia para estabelecer uma relação harmônica com o tecido da cidade. Transitou entre o emprego de procedimentos clássicos, como simetrias e proporções que espelham a paisagem do entorno e o uso de lógicas recursivas da geometria fractal, desde a escala do urbano ao detalhe, do concreto ao perceptivo, por meio de efeitos anamórficos. Para decifrar este processo utilizou-se de instrumentos gráficos de análise, incluindo a aplicação do conceito de dimensão fractal.

Gehry se valeu dos avanços tecnológicos para garantir o controle preciso da forma, utilizando-se das técnicas de parametrização, associando os parâmetros geométricos que controlam cada tipo formal utilizado, reaproximando a matemática da ação projetual de arquitetura. Os parâmetros empregados determinam convergências, paralelismos, perpendicularidades, proporções derivadas destas relações, concordâncias entre cada um dos elementos da obra com os fragmentos do entorno urbano. Tais relações buscaram estabelecer uma harmonia com o lugar. A parametrização não determinou permanências à forma da cidade, mas ao contrário, gerou contrapontos que dinamizaram a sua paisagem. Em planta, há o claro movimento circular de transição entre superfícies poliédricas e curvas, associados ao propósito de integrar o repertório formal do próprio do lugar. Os tumultos referidos por Naomi Stungo não foram aleatórios, mas totalmente controlados, em seus efeitos visuais, sob os diferentes pontos de vista. As fotografias veiculadas da obra, obtidas por pontos estratégicos desde seu entorno imediato, declaram este propósito. O ritmo é dado pela sutil repetição daquele elemento formal que foi extraído ainda do contorno do terreno, percebida por um espectador mais atento à transformação das paisagens da cidade.

Considerações finais

Considera-se que as hipóteses construídas e evidenciadas graficamente explicitam as estratégias utilizadas por Gehry para estabelecer o diálogo entre a obra e o tecido urbano da cidade.

O uso da lógica fractal para estabelecer as relações com o lugar foi a estratégia para garantir que a obra mantivesse sua unidade formal, pelo menos em termos geométricos. O arquiteto usa a recursão para estabelecer uma relação harmônica e rítmica com o lugar. Proporções e repetições dialogam com a arquitetura existente no entorno imediato.

Conclui-se pela conveniência didática da construção de críticas arquitetônicas associadas a elementos objetivos. Entende-se que esta postura investigativa ativa conceitos e procedimentos, exigindo explicitar as estruturas de saber envolvidas na ação projetual.

Referências

BACKES, A.; BRUNO, O. M. Técnicas de Estimativa da Dimensão Fractal: um Estudo Comparativo. INFOCOMP (UFLA), v. 4, n. 3, p. 50-58, 2005.

BILBAO Ría 2000, S.A. BILBAO RÍA 2000. Bilbao: [s.n.], 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.bilbaoria2000.org/ria2000/cas/bilbaoRia/bilbaoRia.aspx?primeraVez=0>. Acesso em: 21 Mai. 2017.

COSTA, P. C. Metodologia aplicada ao cálculo da dimensão fractal de formações urbanas utilizando o índice de desenvolvimento humano municipal (IDHM) como critério de seleção. Revista Mackenzie de Engenharia e Computação, v. 14, p. 71-90, 2014.

DONADA, J. (Diretor). Le Musee Guggenheim de Bilbao [Filme Cinematográfico], 2004. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhJ62_IJKWw&t=307s

FONATTI, F. Principios elementales de la forma en arquitectura. [s.I.]: Gustavo Gilli, 1988.

GANHÃO, Susana M. G. R. Fractais na arquitectura. Artitextos; Lisboa: CEFA/ CIAUD, n. 8, p. 261-271, 2009. [online] ISBN 978-972-9346-12-5.

GIRON, L. A. O arquiteto espetacular. Revista Florense, n. 45, p. 12-19, outono de 2015.

GUGGENHEIM. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. 2017. [online] Disponível em: <https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/el-edificio/>.Acesso em: 18 Mai. 2017.

ISENBERG, B. Conversations with Frank Gehry. Nova Iorque: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

JENCKS, Charles. The New Paradigm in Architecture. In: JENCKS, C. The New Paradigm in Architecture: The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. Londres: Yale University Press, 2002. p. 155-163.

JONES, Denna. Tudo sobre Arquitetura. Rio de Janeiro: Sextante, 2015.

LINDSEY, B. Digital Gehry: material resistance / digital construction. Basel; Boston/ Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2001.

MANDELBROT, B. B. The fractal geometry of nature. Nova Iorque: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1983.

FOX TELEVISION. Os Simpsons. Episódio n. 349: The Seven-Beer Snitch. Abr. 2005.

OSTWALD, M. J.; VAUGHAN, J. Representing architecture for fractal analysis: a framework for identifying significant lines. Architecture Science Review, v. 56, p. 242-251, 2013.

OXMAN, Rivka. Theory and design in the first digital age. DESIGN STUDIES, Londres: Elsevier, n. 27, p. 229-265, 2006. Disponível em:

<http://www.technion.ac.il/>. Acesso em: Set. 2015.

PAGNOTTA, Brian. Clássicos da Arquitetura: Museu Guggenheim de Bilbao / Gehry Partners. [online] Disponível em: http://www.archdaily.com.br/br/786175/classicos-da-arquitetura-museu-guggenheim-de-bilbao-gehry-partners>. Acesso em: 02 Jun. 2017.

ROCHA, L. S.; BORDA A. S., A. Entre o discurso e os elementos objetivos que descrevem a forma do museu Guggenheim de Gehry. In: ENANPARQ, 4., Porto Alegre: PROPAR / UFRGS, 2016. Anais...

SALA M. MARTINS, A. M., HENRIQUE LIBRANTZ, A. F. A geometria fractal e suas aplicações em arquitetura e urbanismo. Exacta, s..n, 2006, p. 91-93. [on line]Disponível em: <http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81009916>. Acesso em: 18 Mai. 2017.

SALA, N. Complexity in architecture: a small scale analysis. In: COLLINS, M. W.; BREBBIA, C. A. (Eds.). Design and Nature. v. 2. Sowthampton/ Boston: WIT Press, 2004. p. 35-44.

SEDREZ, M. Forma fractal no ensino de projeto arquitetônico assistido por computador. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2009.

SLESSOR, C. 1997 December: Guggenheim Museum By Frank O. Gehry & Associates (Bilbao, Spain). Abril de 2010. Disponível em: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/1997-december-guggenheim-museum-by-frank-o-gehry-and-associates-bilbao-spain/8603272.article. Acesso em 04 de junho de 2017.

STUNGO, Naomi. Frank Gehry. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2000.

ZAERA-POLO, A. Arquitetura em Diálogo. São Paulo: Cosac-Naify, 2015, p. 203-237.

1O conjunto de intervenções urbanas que caracterizam o “Efeito Bilbao” integram urbanismo, transporte e meio ambiente, com o intuito de requalificar áreas da cidade anteriormente degradadas. A Sociedade BILBAO Ría 2000 (entidade sem fins lucrativos criada em 1992) atua conjuntamente com a administração pública de Bilbao, coordenando e executando diversas ações nesse sentido (BILBAO, 2015).

2Do original em inglês: “[…] it reflects the shifting moods of nature, the slightest change in sunlight or rain. Most importantly its forms are suggestive and enigmatic in ways that relate both to the natural context and the central role of the museum in a global culture. [...] This emergent strategy […] has now become a dominant convention of the new paradigm”.

3Do original em espanhol: “[...] el diseño de Gehry crea una estructura escultórica y espectacular perfectamente integrada en la trama urbana de Bilbao y su entorno”.

4Do original em inglês: “[…] many of the irregular and fragmented patterns around us, and leads to full-fledged theories, by identifying a family of shapes I call fractals. The most useful fractals involve chance and both their regularities and their irregularities are statistical. Also, the shapes described here tend to be scaling, implying that the degree of their irregularity and/or fragmentation is identical at all scales”.

5Do original em inglês: “Since the 1990s, fractal analysis has been used to measure the formal properties of urban designs, town plans and skylines (...). Architectural researchers have also used a manual variation of fractal analysis to measure the visual properties of contemporary and historic buildings”.

6No contexto deste artigo os conceitos relacionados à parametrização são referenciados nos termos de Oxman (2006, p. 252), considerando que a relação entre os elementos de uma forma geométrica é explícita e pode ser controlada através de parâmetros, o que possibilita gerar e manipular formas complexas.

7Do original em inglês: “When I designed the tower, I thought of a sail. There´s a moment when you´re sailing and the boat goes about a new face into the wind. Just for a fraction of a second the sail quivers. I cought that moment. That is what I try to do with my buildings: giving them an impression of movement pleases me because that makes them part of the great move into the city.. The buildings are part of life and their change. There is something transitory about them”.

The (geometrical) dialogs Gehry establishes with the city of Bilbao

Luciana Sandrini Rocha is architect and urban planner, Master in Geography. She is Professor of Building Technical Course, at Sul-Rio-Grandense Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology. She studies graphic representation, building project, construction materials and integrated environmental management.

Adriane Borda Almeida da Silva is architect and urban planner, Doctor in Philosophy and Sciences of Education. She is Associate Professor at Federal University of Pelotas. She studies digital graphic representation, geometrical and visual modeling, didactic transposition and distance education.

How to quote this text: Rocha, L. S.; Silva, A. B. A The (geometrical) dialogs Gehry establishes with the city of Bilbao. Translated from Portuguese by Sávio de Oliveira Nogueira. V!RUS, 14. [online] Available at: <http://www.nomads.usp.br/virus/virus14/?sec=4&item=14&lang=en>. [Accessed: 15 July 2025].

Abstract

The shape of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao is problematized here with the didactic interest of investigating the design strategies used by Frank Gehry to reconfigure the urban fabric and landscape involved. There are few discourses about the design, accompanied by objective reasoning and supported by its formal decomposition. The convenience of this complementation is considered, given its potential as a reference in the architectural training process. We hypothesize that the shape of the building comes from a reduced repertoire of formal fragments within this fabric and landscape, configured both by classical composition rules and by fractal geometry. This interpretation, constructed by means of overlapping drawings to the photographic and technical images of the building and its immediate surroundings and by the concept of fractal dimension, facilitated the identification of strict formal control, which starts with the regulation of its representations in orthographic projection, maintaining proportions, parallelism and convergences; such as in perspective, exploring continuity achieved through anamorphic effects. Thus, we demonstrate the use of a method, of geometric approach, which facilitates the construction of hypotheses regarding design strategies. In this case, Gehry’s strategies to dialog with a particular urban fabric: through recursive actions, using topologic transformations, in its mathematical meaning, in the formal vocabulary of the place itself, actions today made easy through the digital means of representation.

Keywords: Guggenheim Museum; Frank Gehry; Architectural form; Fractal Geometry; Teaching design.

1 Introduction

This paper shows a study of the design of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, designed by Frank O. Gehry. He won the competition, in 1990, among three proposals presented to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. According to information available on the Museum’s website (Guggenheim, 2017), Gehry’s participation in this competition was invited, and the construction took place between 1993 and 1997, imposing itself on Bilbao’s landscape (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: View of the Museum. Source: Image by Alex Ferrer Gimeno made available through Google Street View in December 2016.

Naomi Stungo, illustrating her speech with photographs of the building, considers that Frank Gehry produced “an explosion by the riverside, a riot of contours and shapes” (Stungo, 2000, p.20). The impact of this construction, also observed by Isenberg (2009), is part of the revitalization movement of Bilbao, a city that was experiencing great economic stagnation at the time. It is true that the phenomenon, known as "Bilbao Effect", should not be attributed exclusively to the construction of the Museum. It was a part of an urban requalification project that covered several areas of the city and is still being implemented, but it is recognized that Gehry's project had become the icon of this phenomenon. Stungo also comments that:

‘[...] Gehry’s architecture is not considered “difficult”, as is the case with much of modern art […]. Exactly like the cubists, in the beginning of the twentieth century […] Gehry’s architecture, at the end of the century, presents the buildings with astonishing disharmony, an experience from all angles at the same time’ (Stungo, 2000, pp.10-11, emphasis added).

Naomi Stungo’s opinion is highlighted to question the consideration of “disharmony”. In formal terms, does the building establish a dialogue with the city?

Charles Jencks, with his speech, also illustrated only by photographic images of the building, observed that:

‘[…] it reflects the shifting moods of nature, the slightest change in sunlight or rain. Most importantly its forms are suggestive and enigmatic in ways that relate both to the natural context and the central role of the museum in a global culture. [...] This emergent strategy […] has now become a dominant convention of the new paradigm’ (Jencks, 2002, pp.157-158, emphasis added).

This discourse raises questions about what formal elements of the building the author is referring to for visualizing, for example, the relationships with the natural context. It seems it was not restricted to the sensibility of “mood” of climate variations.

Denna Jones reinforces Charles Jencks’s perception, that we are facing a new paradigm in architecture’s production process, stating:

‘Originally a sculptural exercise, the museum’s initial shape was not a result of digital methods, but of Gehry’s appreciation of the landscape and the context. As the design evolved, Gehry was increasingly impressed with the ability of digital software to generate a form’ (Jones, 2015, pp.523-524, emphasis added).

Here, Jones observes Gehry’s interest in the potential of digital tools for perfecting his design process, realizing how much he could precisely control the form and its connection to the place.

Other discourses reaffirm that this form derives from a sculptural process from and for the place: “… Gehry’s design creates a sculptural and spectacular structure, perfectly integrated into Bilbao's urban fabric and its surroundings” (Guggenheim, 2017, our translation) 2. Gehry reinforces these statements in an interview given, in 1995, to Zaera-Polo:

‘Bilbao is a very contextual design, but not in the conventional sense [...]. I hope that, when people see the completed building, they realize that I’m dealing with the context. Bilbao is a very hard industrial city, with a river and amazing green landscape. The grounds of the museum are set on a wonderful bend over the river. The city lies above ground level... The problem with this building was to link the city with the river, to bring the city to the other side of the road, involve it up to the river. In fact, my first decision was to propose the site” (Zaera-Polo, 2015, p.228).

The collection of documentation for this building, digital or printed, conveyed in scientific or non-scientific contexts, refers mainly to photographic images. It is necessary to go through the building from different visual trajectories to apprehend it. Plans, elevations, and sections are, in this case, dense and not very clear elements, even for a specialized reader.

With an essentially didactic interest, we question which elements of geometry Gehry uses as support to establish this "riotous", "enigmatic" and "integrated" relationship with the city. Among so many formal elements of the surroundings, which ones were more or less determining for the building’s configuration?

For Jencks (2002, p.157), several of Gehry’s buildings, including this museum, incorporate elements from the fractal geometry. This geometry, systemized by Benoit Mandelbrot, uses knowledge built in the history of Mathematics associated with computer graphics, involving recursive procedures to describe the forms of nature that had not been contemplated by Euclidean Geometry.

‘[…] It describes many of the irregular and fragmented patterns around us, and leads to full-fledged theories, by identifying a family of shapes I call fractals. The most useful fractals involve chance and both their regularities and their irregularities are statistical. Also, the shapes described here tend to be scaling, implying that the degree of their irregularity and/or fragmentation is identical at all scales’ (Mandelbrot, 1983, p.1, emphasis added).

Fractals can be defined by an initiator and a generator which go through a process of recursion and scale change, keeping, however, self-similarity or even self-affinity. Thus, the parts are reduced versions of the whole object, the difference between self-similar and self-affine being that, in the second case, the versions are formed in different scales and directions in space. Furthermore, both kinds can be exact or statistical, characterized by probability, the last one having its version in reduced scale statistically equal to the whole object.

Mathematically, fractal geometry brakes the paradigm of a whole dimension as a condition to characterize an element, constituting the concept of Fractal Dimension (D). This is used to determine the degree of space occupation, so that the bigger the irregularity of a given form, the greater its D. According to Backes and Bruno (2005, p. 51), literature provides several approaches to estimating the Fractal Dimension, with a logic that generalizes the calculation of the topological dimension in the context of Euclidian geometry (whole dimensions) to encompass also the calculation of Fractal Dimension (fractioned). The “Box-Counting” method is an approach which makes the comprehension easier by professionals used to a more visual language instead of algebraic because it adopts a procedure of counting the cells that the form of the investigated element occupies in a particular space. These cells are subdivided, recursively, until all of them acquire the condition of being completely full or empty, depending, thus, on a resolution scale. According to Ostwald and Vaughan (2013, p.242),

‘Since the 1990s, fractal analysis has been used to measure the formal properties of urban designs, town plans and skylines [...]. Architectural researchers have also used a manual variation of fractal analysis to measure the visual properties of contemporary and historic buildings’.

Sedrez (2009) and Ganhão (2009), in referring to the museum’s form as a fractal, reproduce Jencks (2002) and also Sala M. Martins and Henrique Librantz (2006, p. 92), in the sense that the discourses are not accompanied by graphic or numerical demonstrations.

In an interview given to Giron (2015, p.16), Gehry problematizes the use of computational means in a design process:

‘[...] Hand drawings give it a sense of continuity (...) I love the idea of complete and ambiguous continuity. Only later do I transpose it to the computer screen. The image on the computer is lifeless, cold, horrible. The computer cannot be the inventor of forms. We are the ones that must master it’ (Emphasis added).

Even when relying on the potential of software for the development of his ideas, Gehry’s design process is established initially by sketches and physical models. When questioned about the possibility of comparing his design method through the use of many models to that of Renaissance architects, Gehry replies to the architect and critic Alejandro Zaera-Polo in the following manner:

‘Yes, it’s true. [...]. If I had to say what is my greatest contribuition to the architectural practice, I would say it’s managing the coordination between the hands and the eyes. This means that I have become very good at carrying out the construction of an image or a form that I am looking for. I think it’s my best skill as an architect. I am able to transfer a sketch into a model and then into a building […]’ (Zaera-Polo, 2015, p.221).

For the design process of the museum, models were made after the hand sketches, which were then decoded into the CAD-CAM language using a digitalizing pen, through the software CATIA. From this model controlled in the digital space, the design team developed the documentation of the architectural design as well as the structural calculations and the details of the metal structure and coatings (Lindsey, 2001, pp. 43-44). Gehry had already experimented in previous projects, such as the fish-shaped sculpture of Barcelona’s 1992 Olympic Village and the design of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which was only finished in 2003. However, it was through the museum in Bilbao that he and his team consolidated this method and Gehry found a way of actually controlling form with the precision he desired.

The architect received the Pritzker Prize in 1989 having, thus, recognition for his work by the specialized architectural critique. His production is so expressive that it was the theme of an episode of “The Simpsons” (Fox, 2015). In the referred episode, Gehry’s creative process is shown in irony, associated with the idea of being “random”, devoid of a method and with no programmed connection to the city’s fabric. His character draws from a crumpled sheet of paper the inspiration for the design of a concert hall. It also shows in irony the building process, showing a conventional metallic structure which is deformed by mechanic processes, appearing to be an act of destruction. This shows that his work is also appreciated and discussed by the lay public.

This paper starts with the hypothesis that, far from being a random procedure, the Guggenheim in Bilbao was a project that justified the use of parametric control of form, to harmonize classical practices of form organization with the logic of fractal geometry. The connection with this kind of geometry was made to guarantee a dialogue between the building and the city in its natural and built elements. Starting from this brief literature review, we invested in formally investigating the building, in its objective elements characterized by its geometry. Thus, identifying the formal organizational logics involved, from classic to recursive.

2 Methodology

This paper expands on the study registered in Rocha and Borda (2016), incrementing the method, drawing on Fonatti (1988) and using the concept of Fractal Dimension. We start with the analysis of digital documentation, which includes photographs of the surroundings of the building and photographs and technical representations of the building, such as plans, sections, and elevations, made available in books, magazines, videos and on the web.

To understand the use of logics relative to the Fractal Geometry, we continued with graphic analysis, observing the incidence of self-similarity or self-affinity through a comparison process, adding the estimate of the Fractal Dimension, through the Box Counting Method. This consists in applying the grid recursively over the elevations of the building and surrounding buildings, and the analysis of proportion and number of squares occupied in relation to the total number of squares. Costa (2014, p. 80), Sala (2004, p. 41) and Backes & Bruno (2005, p.3) explain this method in more detail.

For the topologic studies, the method can be described in the same terms as Fonatti (1988):

‘1) [...] the reflections have its origins in the didactic experience in teaching geometry; 2) the base is made up of visual communications (graphic, represented in the form of drawings, plans, formal elements, structural creation matrixes, form analysis, proportion studies and building diagrams); 3. The means is the comparative method, investigating forms and structures through a comparative analysis. And referring to the content the method has four aspects: a) the internal logic of the form… The form in its composition logic… b) The update and the effect of the form. The technical-creative aspects of the form in its origin and its didactic renewal… The form in its origin and appropriation. C) the form in its surrounding. The relation between the form and its external and exogenous constraints; … the form as a creative game in the process of communication, as a concrete result in its surroundings… D) transformation of the surroundings through the form’ (Fonatti, 1988, pp.11-12).

The results of the study show the hypotheses being presented to highlight how much the city’s fabric determined and was determined by the formal logics associated with this building.

3 Building hypotheses

3.1 The origin of the form and its relation to the place

The site chosen by Gehry for the museum is on the banks of the Nervión River, close to the University, the Museum of Fine Arts and the Arriaga Theater, important cultural centers of the city of Bilbao. It has easy access through Iparraguirre Street and Salbeko Zubia Bridge, highlighted in the image on the left in Figure 2. We draw attention to the shape of the terrain, which was already outlined by the curves of the river and the bridge, and can be observed when comparing the two images on the right of Figure 2, before and after the construction of the building. This form is hypothesized as the origin of the vocabulary employed by Gehry.

Fig. 2: a) The museum and its surroundings, b) site before construction (1991) and c) after construction. Source: Elaborated by the authors based on images taken from Google Earth. Accessed May 2016.

The museum stretches under the bridge, built in the 1970s, through one of its exhibition halls (Room 104), which connects to a tower on the opposite side of the bridge (Figure 3). This tower is the tallest element of all the construction and is the access to the museum for those who arrive from the bridge, being a counterpoint to the volume of the atrium, which only stands out in relation to it regarding its proportions. Gehry reports his intention in designing the tower in a video by Donada (2004):

‘When I designed the tower, I thought of a sail. There´s a moment when you´re sailing and the boat goes about a new face into the wind. Just for a fraction of a second the sail quivers. I caught that moment. That is what I try to do with my buildings: giving them an impression of movement pleases me because that makes them part of the great move into the city. The buildings are part of life and their change. There is something transitory about them’ (Donada, 2004).

The site surroundings and its topographic conformation were decisive in Gehry’s design. To the south, at a higher elevation (located at the level of the access streets), the building presents itself through orthogonal forms and traditional materials. With this, it establishes a relationship with the historical spaces of the city, both formally and by the coatings and colors adopted.

The elements facing North, by the river, show organic forms and reflective materials, such as glass and titanium, which value the relationship between the building and the water and nature, which is reinforced by the presence of a water surface mirror. The titanium gives the building its copper-like color and changes shade according to the time of the day and climate conditions, as observed by Charles Jencks. The fact that this part of the terrain is on lower ground than its surroundings allows the building, even on a monumental scale, to respect the heights of the surrounding buildings, integrating itself to them and still representing an unprecedented element in the landscape.

The atrium, as well as being an internal organizing element, giving access to the galleries through walkways, is also an organizing element in terms of volume, contrasting with what surrounds it. It constitutes a hybrid space, between the exterior and interior, communicating the building to the city and the river thanks to the three storey high glass panes. This space is covered by “a large skylight in the shape of a metal flower” (Guggenheim, 2017), it also seems to be related to the form of the original lot (Figure 2b), which is similar to a leaf or petal (self-affinity).

3.2 The form and its external constraints

Figure 3 shows the regulatory strokes and axes with the starting point on the Salbeko Zubia bridge’s path. We observe that there is a convergence of such strokes where the atrium is, reflecting its importance in organizing the internal spaces, connecting the axes of the prismatic volumes: the one with greatest extension (which also converges with the axis from the bridge), the one with the smallest extension (to the left) and the one from exhibition room 104, already mentioned before for extending beneath the bridge and connecting to the tower.

Fig. 3: Regulatory strokes. Source: elaborated by the authors based on images available on the internet. Available at: www.jaumeprat.com/el-lugar-de-la-ensenanza/ [Accessed 2 March 2016].

3.3 The formal repertoire

The building transits between polyhedral and curved surfaces, between developable ruled surfaces, reverse surfaces and surfaces with a greater degree of freedom. Understanding the organizational scheme of the museum gives us clues to understand some purposes of formal associations, as shown in Figure 4: a) the atrium (in yellow) is a space of central distribution, in hybrid conformation, integrating the formal types of spaces which characterize the building; b) the volumes of the administrative, commercial and exhibition spaces on the ground floor are organized around the atrium, and walkways promote the circulation above it (in yellow); c) “usable areas” are distributed in three floors, and glass panes make the vertical closure between the volumes; d) overall volume, observing prisms, cylinders, these with curved guidelines and orthogonal generatrix (in beige and blue), and cylindroids or free forms (in gray); e) the demonstration of the “working height” of the building, which is less than half of its total height.

Fig. 4: Organizational structure of the museum. Source: Elaborated by the authors based on images from the video by Donada (2004).

As can be seen on the set of images in Figure 5, the types of galleries are associated with the geometry of the spaces. The prismatic volumes comprise mainly the “traditional” galleries, its plans being of rectangular or square shapes, which receive the “classic” exhibitions. The galleries for contemporary art exhibitions have curved floor plans and much higher ceilings.

Fig. 5: Exhibition rooms. Source: Elaborated by the authors based on images from the video by Donada (2004).

3.4 Form and its composition logic: between proportion and symmetry

As shown in the images in Figure 6, we found correspondence with certain proportions: (b) shows the square root of 2 rectangles on the bounding rectangles of the prismatic volume of the elevation, the grouped windows and each individual window; (c) and (d) show the golden ratio on the prismatic volumes of the “traditional” exhibition rooms, square proportion on secondary volumes and in the “traditional” exhibition rooms, and square root of 2 proportion on the bounding boxes of the curved surfaces. (a) shows the wooden models which, resulting from the plan analysis, we hypothesize as being made from bounding boxes controlled by the square root of 2 proportion which is most frequent in the design. The fact that these forms were produced individually in wood indicates that great care was taken in modeling these surfaces. Lyndsey (2001, p.45) reports that after the design’s development in CATIA, a verification model was produced to guarantee the precision of the forms.

Fig. 6: Proportions and symmetries. Source: elaborated by the authors from images available on the internet in Guggenheim, 2017; Pagnotta, 2016 and Slessor, 2010.

3.5 Technical-creative aspects and the didactic renewal: the estimation of the Fractal dimension of the building

The calculation of the Fractal Dimension was done based on two confronting images, with the purpose of comparing them: the south elevation of the museum and the group of buildings outlined by vegetation in the background. This was done due to the similarity between the two images (Figure 7), a possible strategy for reflecting the city not only by the light effect on the titanium but also as a result of a geometric transformation, repeating the form itself.

Fig. 7: On the left, the image of the surroundings that confront the building, and on the right, the south elevation (facing the city). Source: Elaborated by the authors from images available on Google Earth Application and in Pagnotta, 2016.

We applied the “Box Counting” Method considering three iterations of the recursive procedure of subdividing the reference grid, as shown in the examples of the south elevation in the sequence of images in Figure 8.

Fig. 8: Box Counting method applied to the south elevation (facing the city). Source: Elaborated by the authors from images available in Pagnotta, 2016.

Table 1 shows the calculations in applying the method. The values are very close, demonstrating that although it seems like a group of “riotous forms”, the degree of space occupation, in visual terms, seems to correspond to that of the pre-existing landscape. Thus, permanence is observed through this approach. Rhythmic orthogonal elements in the foreground and later curved contours with similar roughness to the background.

Table 1: Calculation of D for a) the surroundings and b) the south elevation. Source: elaborated by the authors.

Note [3] Value calculated based on interactions 0 and 1.

Nota [4] Value calculated based on interactions 1 and 2.

3.6 Self-affinity: from urban to the building scale

Depending on the level on which sections are made to obtain the floor plans, the forms of the Museum assume different curvatures. However, in the analysis of the building's site plan, it is possible to identify a counter-clockwise recursive procedure of variation in scale of the different forms, the position of the atrium being the central axis. Figures 9 (a) and 9 (c) show the leaf shaped (same shape as the terrain) patterns and the overlap between these patterns, showing a topological correspondence among them. Figure 9 (b) shows the same patterns on the site plan.

Fig. 9: Sickle leaf patterns. a) the patterns identified; b) site plan with the sickle leaf patterns; c) overlap of the patterns. Source: elaborated by the authors from images available on the internet. Available at:www.http://jaumeprat.com/el-lugar-de-la-ensenanza/ [Accessed 2 Mar. 2016].

3.8 Transformation of the surroundings from the form: tangency continuity, parallelism and convergence relations in the views

Using physical models, or with precision, through digital means, Gehry controls the form at eye level. He seems to take advantage of anamorphic effects (optical illusions from certain points of view) to achieve continuity and parallelisms. As observed on the images in Figure 10, the photographs chosen to be shown on the Museum’s official web site make the intention of continuity and convergence explicit.

Fig. 10: Continuity. Source: elaborated by the authors based on images available on Museum’s web site (Guggenheim, 2017).

These images also show the reinforcement of the idea of recursion, of the fractal characteristics of the building, in which the views always refer to the form of a leaf, from which the reference comes from the terrain itself (Figures 2 and 10).

4 Results and discussion

We observed that there is considerable distance between the caricature of Gehry’s design process, the supposed randomness, shown by the episode of “The Simpsons”, and the effective complexity and control of such process. The architect extracted from the site itself the formal vocabulary to be used, as a strategy for establishing a harmonic relationship with the city’s fabric. He transited between classic procedures, such as symmetry and proportion reflecting the surrounding landscape, and the use of recursive logics from the fractal geometry, from the urban scale to the detail, the concrete to the perceptive, through anamorphic effects. To decipher this process, we used graphical analysis tools, including the concept of fractal dimension.

Gehry relied on technological advances to ensure the precise control of form, using parametrization techniques, associating the geometric parameters that control each formal type used, re-approximating Mathematics to the action of architectural design. The parameters applied determine convergence, parallelism, perpendicularity, proportions derived from these relations, continuity between each one of the building’s elements and the fragments of the urban surroundings. Such relations seek to establish harmony with the place it is in. The parameterization did not determine permanence on the shape of the city, but on the contrary, it generated counterpoints that made its landscape dynamic. On the floor plan, there is the precise circular movement transition between polyhedral and curved surfaces, associated with the purpose of integrating the formal repertoire of the place itself. The riots mentioned by Naomi Stungo were not random but fully controlled, in its visual effects from different points of view. The published photographs of the building, taken from strategic points of its immediate surrounding, declare this purpose. The rhythm is given by the subtle repetition of the formal element extracted from the terrain’s contour, perceived by a spectator more attentive to the transformation of the city's landscapes.

5 Concluding remarks

We consider that the hypotheses constructed and graphically evidenced explicit the strategies used by Gehry to establish the dialogue between the building and the city’s urban fabric.

The use of fractal logic to set the relationship with the place was the strategy to guarantee that the building would maintain its formal unity, at least in geometric terms. The architect uses recursion to establish a harmonic and rhythmic relationship with the place. Proportions and repetitions build a dialog with the existing architecture of the immediate surroundings.

We conclude with the didactic convenience of building architectural criticism associated with objective elements. We understand that this investigative posture activates concepts and procedures, requiring the knowledge structures involved in the designing action to be made explicit.

References

Backes, A. and Bruno, O. M., 2005. Técnicas de Estimativa da Dimensão Fractal: um Estudo Comparativo. INFOCOMP (UFLA), v. 4, n. 3, pp. 50-58.

Bilbao Ría 2000, S.A., 2015. Bilbao Ría 2000. Bilbao. Available at: <http://www.bilbaoria2000.org/ria2000/cas/bilbaoRia/bilbaoRia.aspx?primeraVez=0>. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

Costa, P. C., 2014. Metodologia aplicada ao cálculo da dimensão fractal de formações urbanas utilizando o índice de desenvolvimento humano municipal (IDHM) como critério de seleção. Revista Mackenzie de Engenharia e Computação, v. 14, pp. 71-90.

Donada, J. (Director), 2004. Le Musee Guggenheim de Bilbao [Movie Film]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhJ62_IJKWw&t=307s.

Fonatti, F., 1988. Principios elementales de la forma en arquitectura. [s.I.]: Gustavo Gilli.

Ganhão, S. M. G. R., 2009. Fractais na arquitectura. Artitextos, 8, pp. 261-271.

Giron, L. A., 2015. O Arquiteto Espetacular. Revista Florense, 45, pp. 12-19.

Guggenheim, 2017. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Available at: <https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/el-edificio/> [Accessed 18 May 2017].

Isenberg, B., 2009. Conversations with Frank Gehry. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. E-book.

Jencks, C., 2002. The New Paradigm in Architecture. In: C. Jencks, ed. 2002. The New Paradigm in Architecture: The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. London: Yale University Press. pp.155-163.

Jones, D., 2015. Tudo sobre Arquitetura. Rio de Janeiro: Sextante.

Lindsey, B., 2001. Digital Gehry: material resistance / digital construction. Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhäuser.

Mandelbrot, B. B., 1983. The fractal geometry of nature. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Fox television, 2005. The Simpsons. Episode 349: The Seven-Beer Snitch. Available at: <www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4S0Qk813fg&list=PLkRnEV5E-n9xSysZ4HmfEokbEuol09yfi&index=6> [Accessed 21 May 2017].

Ostwald, M. J.; Vaughan, J., 2013. Representing architecture for fractal analysis: a framework for identifying significant lines. Architecture Science Review, 56, pp. 242-251.

Oxman, R., 2006. Theory and design in the first digital age. DESIGN STUDIES, 27. London: Elsevier, p. 229-265. Available at: <http://www.technion.ac.il/> [Accessed September 2015].

Pagnotta, B., 2016. Clássicos da Arquitetura: Museu Guggenheim de Bilbao / Gehry Partners. Tradução: Eduardo Souza. 2016. Available at: <www.archdaily.com.br/br/786175/classicos-da-arquitetura-museu-guggenheim-de-bilbao-gehry-partners> [Accessed 02 June 2017].

Rocha, L. S. and Borda A. S. A., 2016. Entre o discurso e os elementos objetivos que descrevem a forma do museu Guggenheim de Gehry. In: 4th Enanparq: Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Porto Alegre: PROPAR / UFRGS.

Sala M. and Librantz, H., 2006. A geometria fractal e suas aplicações em arquitetura e urbanismo. Exacta, pp. 91-93. [on line] Available at: <http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81009916> [Accessed 18 May 2017].

Sala, N., 2004. Complexity in architecture: a small scale analysis. In: M. W. Collins and C. A. Brebbia ed. 2004. Design and Nature. v. 2. Sowthampton, Boston: WIT Press.

Sedrez, M., 2009. Forma fractal no ensino de projeto arquitetônico assistido por computador. Master. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

Slessor, C., 2010. 1997 December: Guggenheim Museum By Frank O. Gehry & Associates (Bilbao, Spain). Available at: <www.architectural-review.com/buildings/1997-december-guggenheim-museum-by-frank-o-gehry-and-associates-bilbao-spain/8603272.article> [Accessed 04 June 2017].

Stungo, N., 2000. Frank Gehry. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify.

Zaera-Polo, A., 2015. Arquitetura em Diálogo. São Paulo: Cosac-Naify, pp.203-237.

This document was edited with the online HTML5 composer. Please subscribe for a htmlg.com membership to remove similar messages from the edited documents.